ABSTRACT

Homelessness is a pervasive social issue worldwide. In the UK, it is currently estimated that one in two hundred people are homeless, approximating 0.5% of the population. Pet ownership among this group is thought to be commonplace and has been linked with a range of human health and social benefits. These include amelioration of loneliness, isolation and depression and reduction in suicidal thoughts, substance misuse and criminal activity. However, pet ownership has also been suggested to perpetuate homelessness by restricting access to support services, especially housing. This study aimed to explore the nature of the Human–Companion Animal Bond (H-CAB) between UK homeless owners and their dogs, and to document the implications of this bond for the health and welfare of both parties. Twenty homeless or vulnerably housed dog owners were recruited to participate in semi-structured interviews consisting of open and closed questions. These were recorded, transcribed and subjected to thematic analysis. Major emergent themes included participants’ descriptions of their pets as kin; the responsibility they felt towards their pet; and anticipatory grief when contemplating a future without their companion animal. Importantly, the analysis also suggests the importance of a mutual rescue narrative, whereby pet owners felt that they had rescued their dogs from a negative situation, and vice-versa. However, participants also described being refused access to services, frequently on account of their desire not to relinquish their pet. Indeed, given their description of their pets as family members, participants expressed frustration that this relationship was not considered as being of worthy of preservation by homelessness services. This study has highlighted some important features of the H-CAB between homeless owners and their dogs, not previously characterized in the UK. It also highlights the importance of empowering support services to accept pets where feasible, and thus preserve and enhance the benefits of pet ownership in this vulnerable population.

Since 2010, the UK homeless population has been increasing. In 2018 it was estimated to comprise 320,000 people, including 130,000 children, representing 0.5% (1 in 200) of the population (Shelter, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Of these, over 4,600 people sleep rough every night (Shelter, Citation2018a). This latter is likely an underestimate, as many rough sleepers will actively avoid such counts. In addition to rough sleepers, homelessness includes those living in hostels, sofa surfing, or in other forms of temporary accommodation (the “Hidden Homeless”).

Homelessness is linked with poverty and social isolation and is considered a risk factor for both poor physical and psychological health (London, Citation1992; Scott, Citation1993). Mental ill-health, suicide, and substance misuse pose particularly prevalent challenges (Bhugra, Citation2007; Hemming, Citation2015; Thomas, Citation2012). Physical ailments associated with adverse living conditions and substance misuse are more common amongst the homeless than the housed population (Homeless_Link, Citation2014). Not surprisingly therefore, the average life expectancy of homeless individuals is 47, some 30 years lower than that of the general population, with suicide and substance misuse being key causes of death (Thomas, Citation2012).

Pet ownership among homeless people is common. The UK prevalence is unknown, but studies elsewhere have reported between 5% and 24% of homeless people owning pets, with the majority being dogs (Cronley et al., Citation2009; Rhoades et al., Citation2015). These dogs are perceived as primary and often exclusive sources of physical, psychological, and social support (Cleary et al., Citation2019; Cronley et al., Citation2009). Companion animals have been reported to alleviate feelings of loneliness, isolation, and depression, increase resilience, and buffer the negative effects of stressful life events by mitigating feelings of stress and anxiety (Hart, Citation2010; Siegel, Citation1990). Loneliness is a risk factor for depressive symptoms (Cacioppo et al., Citation2006) and homeless people with pets have been shown to have lower levels of depression and loneliness compared with those without (Lem et al., Citation2016; Rhoades et al., Citation2015).

For socially isolated individuals, animals can provide comfort and a sense of friendship (Howe & Easterbrook, Citation2018; Irvine, Citation2013). Dogs may also act as social facilitators, increasing encounters with other people and help to mediate these interactions (McNicholas & Collis, Citation2000; Wells, Citation2004). This may be dependent on both owner and dog characteristics, with younger dogs or those perceived to have more likeable characteristics receiving more positive attention than others (Wells, Citation2004).

Benefits to owners may have positive repercussions for wider society through reducing anti-social and criminal behavior. Caring for animals can facilitate behavior change by providing a sense of responsibility and identity. For example, studies show that involvement in the care and training of rescue dogs improves prisoner psychological wellbeing (Fournier et al., Citation2007; Harkrader et al., Citation2004) and increases prosocial behaviors such as self-control and respect (Furst, Citation2007). Other studies have included self-reported reductions in criminal behavior by homeless people as a result of pet ownership; however a consistent link has not been established (Bender et al., Citation2007; Thompson et al., Citation2006).

The importance of these dogs to their owners is shown by their welfare. Notwithstanding the rigors of poverty and rough sleeping, the limited data available suggest that most aspects of welfare are generally at least as good in homeless-owned dogs as in conventionally owned dogs (Scanlon, Citation2017, February; Williams & Hogg, Citation2015).

Despite the benefits, owning a pet as a homeless person is not a panacea. Accessing support services in general, and accommodation in particular, is hindered. Many providers are reluctant to accommodate pets. Given this, many owners choose to remain in vulnerable housing situations rather than part with their animal (Kerman et al., Citation2019; Singer et al., Citation1995). In such circumstances pet ownership may be considered to maintain some individuals’ homeless status. Therefore, for reasons of welfare and policy, it is important to understand more about the perspectives of homeless pet owners.

This study focused on two complementary research questions. Firstly, what is the nature of the Human–Companion Animal Bond (H-CAB) between homeless owners and their dogs? Second, what are the implications of this bond for the health and welfare of both homeless owners and their dogs?

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee at the School of Veterinary Medicine and Science, The University of Nottingham (proposal # 2168 171205).

The study comprised 20 face-to-face semi-structured interviews with homeless dog owners conducted by the first author. Inclusion criteria stipulated that participants should be dog owners who were homeless or vulnerably housed at the time of the interview, or had previously experienced homelessness with their dog.

The semi-structured interview schedule was designed in light of a preliminary study (Scanlon, Citation2017, February). It was initially piloted for face validity with academic colleagues and with members of the Dogs Trust’s Outreach Development team. Finally, the interview schedule was piloted with five homeless dog owners living in a supported housing service.

Participant recruitment was assisted by a number of organizations. A database of dog-friendly accommodation services was provided by Dogs Trust, a UK-based animal welfare charity which includes facilitating access to veterinary care for homeless dog owners via its Hope Project. This was augmented by internet searches and word of mouth to include services providing food, supplies or advice to homeless individuals, as well as The Big Issue (a street paper providing homeless people with the opportunity to earn a living, www.bigissue.com). Services directly providing veterinary care for homeless people’s pets, including Streetvet and Vets in the Community also assisted. Eligible participants were invited to an interview with the researcher either directly or via their keyworkers. Participants could choose to have a keyworker present during the interview. The participants’ dogs were present during all interviews.

Before commencing the interview, all participants were forewarned about the sensitive and personal nature of some of the questions and made aware of their right to refrain from answering any questions, pause the interview, or withdraw altogether up until the point of anonymization. Following this, participants were asked to read and sign a consent form. In addition to the interview, all participants’ dogs were examined using the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals’ appraisal tool (PDSA Petwise MOT) to assess their health and welfare; these results are reported elsewhere.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews began with demographic questions; participants could decline to answer these questions, although none did. Further questions asked about the living circumstances of the participant, how they had become homeless, and their experiences of accessing services. The remaining questions were focused on exploring their relationship with their dog(s), as well as the challenges and benefits they had experienced as homeless dog owners. The final questions were deliberately open: “What does your dog mean to you?” and “Is there anything else you would like to say.”

Interview transcripts were read several times to create familiarization. Transcripts were coded, re-coded, and analyzed thematically using the 6-step method (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) in NVivo (NVivo Citation2012). To ensure consistency, 5% of the data were coded by the primary researcher (LS) as well as by JS, KC, and PHW, and later discussed with AMcB. The rest of the data were then coded by LS alone. To further ensure coding consistency, coding was performed on each transcript multiple times. Once all the data had been coded, initial themes were generated and reviewed by the whole team before being grouped into overarching themes and subthemes. Overall, the analytical approach was inspired by a critical realist approach, meaning that the interview data were treated as evidence of the varied, lived experience of those participating.

Results

Of the 20 participants, 18 identified as homeless at the time of the interview, and two identified as vulnerably housed or at risk of homelessness. They were recruited from seven locations in England: London, Nottingham, Lincoln, Spalding, Preston, Gillingham (Kent), and Plymouth. Eighteen males and two females participated. Participant age ranged from 23 to 65 years, with both the oldest and youngest being male. Demographic information is summarized in .

Table 1. Background details of the participants.

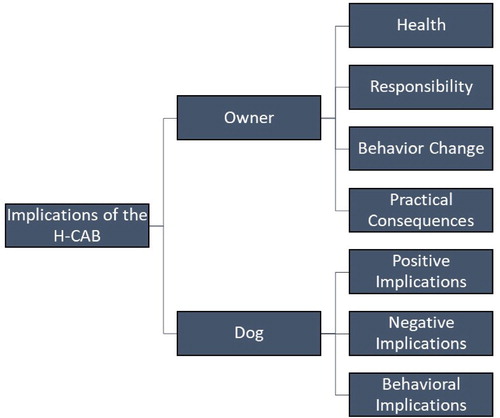

In light of the study’s aims, the data were analyzed to explore “The nature of the Human–Companion Animal Bond (H-CAB)” and “Implications of the H-CA.” The first heading was further split into “Animal as Kin,” “Responsibility,” “Anticipatory Grief,” and “Mutual Rescue.” The second heading was split into implications for the owner or dog, then further split into more detailed categories (see ). The rest of this section discusses the data and provides illustrative extracts from the interviews with homeless dog owners.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of subthemes relating to the overarching theme of “Implications of the H-CAB”.

The Nature of the H-CAB

The analysis confirms that the nature of the bond between homeless dog owners and their animal is dynamic and complex. The following subthemes will explore how this relates to both the nature of this bond from the owner’s perspective and how it impacts the health and welfare of both parties.

Animal as Kin: Many of the participants attributed human characteristics to their dogs. The personification of the dogs was a common theme, with participants describing their pets as friends or family, sharing closeness and unconditional love:

One of my kids, he’s part of my family. He’s a family member. He’s … I don’t know, as much as anyone else in my family means to me, definitely. (Participant 14)

He is my best mate. I love him, as much as I love myself. We are both the same. What he don’t like, I don’t like. What I don’t like, he don’t like. He is just me best mate (Participant 16)

Yes, I know there’s no ulterior motive around it. He’s not out for himself to get what he can, you know. He is loyal, and that is pure love, you know what I mean? (Participant 12)

Don’t keep hold of an animal if you think it’s going to gain you. Like, keep him there because you love him and he loves you. And that’s … that’s all he wants. And that’s all any dog wants, isn’t it? To know that you love him, isn’t it? (Participant 14)

Responsibility: The notion of animals as kin appeared to create an acute sense of responsibility. For example, one participant focused on the idea of responsibility for a being other than themselves:

You get a companion like a dog come along; it really changes everything. Because again you got company, you know, it’s a living, breathing thing you’ve got there and you’re not just thinking about just yourself now, you’re thinking about them. (Participant 2)

They generally seem to care for their dogs. Like, anyone I know … they’d look after their dogs more … Our dogs would eat before anyone else. And that’s the people that I’ve met out on the street. (Participant 14)

He comes first. Like I said, if I felt like he was being neglected, or in any sort of way I would do what was best for him, no matter how much it would kill us. (Participant 12)

But if he starts to become unwell, I wouldn’t hesitate to do the right thing by him, you know. I know it’d hurt me, but I don’t want to see him suffering. (Participant 3)

I hate to leave her outside, especially now that there’s such a thing about dogs being stolen and stuff. It’s even worse. (Participant 2)

I would never leave her anywhere, so I’d have to stay under the stars with her. So yeah, that’s the only thing, housing. It’s been the only negative impact. (Participant 2)

It’s like you can’t go into places to get food because dogs aren’t allowed in there. Trying to get a house to house me and the dog is mission impossible … I’ve already been down the road a bit of people told me to get rid of her, and I gave up my home. I made myself homeless for my dog. (Participant 5)

Just, I don’t want to be sleeping on the street with you, mate. So that’s the only thing. I need to find somewhere for us so that we can still be comfortable together, can’t we, baby? Yeah? Simply comfortable together. Grow old and grey and fat together, yeah? (Participant 3)

I didn’t want him to be on the street either so it was in the back of my mind I was thinking if I can’t get him in here or get him in to a mate I might have to consider putting him up for adoption, which I really didn’t want to do. (Participant 18)

A commitment. A commitment I made from the start and I’ll make to the end. I’ll never let him down and he’s the same with me. (Participant 13)

I’d made sure he’d had a meal at least once a day. I got him his injections. I got him chipped. I’d done all the right things. (Participant 6)

If we needed any treatment for (dog’s name) we’d have to pay for it … they say “oh you’ve got to pay it in full” or you know, and you can’t always. I waited two weeks and then I’ll come and treat her even though she needs treatment now, you know. (Participant 19)

I'm losing him. He is dying … But in that weakness, you see my strength. I would do anything, to make sure that little [dog’s name] is alright. (Participant 16)

Yeah, I don’t know what I would do, it would be a massive gap in my life. I’d probably stop eating. I’d probably go down to about seven stone and end up in hospital or something like that. And then I’d probably stop looking after myself. (Participant 2)

I already know her age, and it just made me upset now, just in case she goes. You know what I mean? If I lost my dog, then I’d probably follow her. (Participant 5)

I got him when he was 10 months old. I had a phone call asking me if I would take this dog before they drowned him. I didn’t know what type of dog he was, or anything like that, but obviously I’ve said, “Of course I’ll take him.” (Participant 12)

Just had this little pup in his jacket, and he was just trying to sell it to get some drugs. He was going to sell it to some other smackhead, and I was having none of it. Just wanted to get her away from them people, yeah. (Participant 5)

He was keeping him in unsuitable situations and beating him regularly. And then that was it. I wasn’t having it. I paid the man some money and I took the dog off of him. I never would have owned a dog before that moment. Yeah, I wasn’t prepared to let that happen. (Participant 15)

He would be fucked without me, he would. As I would without him. (Participant 12)

Well, he’s saved my life in so many ways. He bettered my life in so many ways. It’s just unbelievable. (Participant 6)

Implications of the H-CAB for Homeless Owners

Results suggest that dog ownership and the H-CAB have implications for the owners’ physical, psychological, and social health. There are practical consequences such as reduced access to services including accommodation, advice, and healthcare.

Owner Health – Physical: Several owners reported an increase in physical activity and motivation to go outside associated with owning a dog. In some cases, motivation for self-care was linked to pet ownership:

Yeah, because you got a dog, and you got to be healthy. You’ve got to look after yourself, and it’s like looking after anything else. You’ve got to be strong. For a dog, you’ve got to be strong. (Participant 1)

I’m better off than some of the other guys, because I’ve got a portable radiator. (Participant 6)

If it weren’t for him … you know, within a few seconds I had been pushed in the tent, and the man would have right, had me where he needed me. But he obviously didn’t see that the dog was in right there with him … until obviously I heard him barking and growling, turned around, and he’s scaring the man off. (Participant 12)

I don’t drink or do drugs any more. The buzz I enjoy more is him. (Participant 6)

And I’d have ended up doing a lot more drugs if I didn’t have to get him food and look after him, see? So he probably kept me alive, he did, the boy. (Participant 14)

I don’t know I can’t really explain it but it’s a good thing, it just builds your spirit … And it’s nice when you come home that you know the dog is always really pleased to see you, that kind of thing. (Participant 18)

She knows when I’m getting anxious. She will literally crawl up to my chest and put her head on my heart. She knows before it comes on sometimes, she’ll usually come up really slowly and she’ll go, “bumph.” (Participant 2)

Thoughts of self-harm. Thoughts, voices. That’s where [dog’s name] comes in as well. Since I’ve had [dog’s name], obviously, when I was about to come here, I had to give up [dog’s name] to my mate to look after, I was bad on the voices, the self-harming. (Participant 17)

I mean, when I was really down, I used to talk to him. I know he didn’t talk back but just to have someone there. (Participant 3)

Look at the state of me, I’m … I look like shit. I feel like shit. But this thing wants something to do with me. (Participant 6)

Definitely. Definitely. Because a lot of conversations, or a lot of the associations, are through meeting other dog walkers when I’m walking him. There are people without a dog probably wouldn’t even speak to me, would never have spoken to me in the first place, you know. And sometimes really, they’re the only people that I do have a conversation with in a day. (Participant 3)

He’s turned my life around so much for the better … so many genuine friendships that, once those friendships were made, life for us turned around for the better. (Participant 6)

People wanting to take him from me, people calling me a neglectful dog owner, disrespecting me for having a dog as well [as being homeless]. (Participant 13)

Having (dog’s name) has pretty much stopped up my ability to access any services really. I’m lucky enough that I went to school with my doctor and he will make some leeway. But I still can’t take her into the surgery. I have to get someone to look after her, so I can’t really access anything. (Participant 2)

Responsibility and Behavior Change

As already implied above, the data analysis revealed a perceived close association between dog ownership and the desire for improved self-care and behavior change. This is neatly summarized in the following interview extract:

If you’ve got an animal who’s reliant on you, whether you’re homeless or not, you have to get up in the morning, you have to make sure that they’re fed, you have to make sure they’re walked, they’re watered, their health has to come first before your own. Because of those reasons, you have to think in the future, if that sounds right. (Participant 6)

We find ways of dealing with issues and situations we have, but we wouldn’t fight or argue or anything in front of the dog, because he don’t like it. (Participant 15)

I probably would have done something stupid by now, or I’d be … probably just a nasty hateful person. Before I met him, I had so much hatred in me. He brought it out, it was nice. (Participant 12)

He calmed me down. It’s just I think of him, and love him, I ain’t gonna do anything and leave him to the mercy of someone else because I won’t be around. (Participant 11)

Impact on Access to Services

All participants spoke about the high level of companionship they provided their dog. Most were reluctant to leave their dog for any length of time and none described leaving their dog alone for more than a few hours. Participant 6 argued that his dog’s quality of life exceeded the perceptions of many members of the public:

When we first got together, a lot of people said “You shouldn’t have a dog if you’re homeless.” … [I responded] “So who’s he better off with? With its owner, 24 hours a day, or locked in a house for however many hours a day?” And they couldn’t see where I was coming from. But now people don’t make silly little comments like that because they know he always comes first. (Participant 6)

Well I can’t leave her alone for very long because she barks and barks, so I’ve got to take her wherever. (Participant 7)

There isn’t any night shelter that I know of that would accept me with a dog. One used to, but the dog was in the cellar, and you was upstairs. I wouldn’t leave him on his own downstairs, even when we’d only been together a couple of years, because it’s not fair on him. So I wouldn’t use that facility. But now they won’t allow people with dogs to stay in there anyway. (Participant 6)

We’ve rung nearly 50 odd landlords, and not one of them is interested because of the dog … Everything else is bang on perfect. Soon as you mention the dog it’s, “Nope.” (Participant 5)

They don’t seem to understand how much some people’s animals mean to them. Like if I had a kid, they’d quick to give me a flat, because I had a child, but they’re not quick to work around animals, and they don’t seem to understand that a lot of the people on the streets have dogs. And that’s their … That’s their best mate. That’s their companion. That’s their … But they’re not quick to ask you if you’ve got one, just because you’ve got dogs not a child. For a lot of people, they are their kids. (Participant 4)

Discussion

This study represents the first such investigation of the H-CAB among homeless pet owners in the UK. The results show participants describing an intense bond with their dogs. For many, this was reported as being akin to a close friend or parent–child relationship. This idea of pets as kin mirrors sociological literature on pet ownership more generally (Charles & Davies, Citation2008). More specifically, participants reported numerous psychological benefits to pet ownership. Their dogs were felt to provide protection, security, and even warmth in an otherwise hostile environment, which confirms findings from other studies in similar populations (Cleary et al., Citation2019). More than this, though, the perceived friendship and psychological support identified as related to dog ownership in this study is comparable to that reported by other socially or physically isolated populations, which has been linked with a reduction in depression, anxiety, and loneliness (McNicholas et al., Citation2005).

Significantly, participants in the present study reported that their sense of responsibility for their companion animal encouraged less criminal activity, and alcohol and drug use. This finding has been sporadically reported elsewhere, although no clear overall population level effect has yet been documented (Irvine, Citation2013). The direct and indirect impacts of substance misuse are key causes of death amongst the UK’s homeless population (Thomas, Citation2012). If pet ownership provides a potential route out of addiction for at least some people, this underlines the potentially therapeutic nature of this relationship for owner and society.

Currently, these potential benefits are not fully realized, in part due to the significant difficulties described by participants in accessing services and accommodation with their dogs. Service provider concerns about hygiene and nuisance issues may underly this. However, such issues may be resolved with appropriate education and support (McBride & Montgomery, Citation2018).

The themes of “animal as kin” and “responsibility” help confirm the results of the small number of existing studies on homeless pet owners (Cleary et al., Citation2019). The great majority of this research has been done in the USA, as per Irvine (Citation2013). The current study confirms many aspects of Irvine’s work. This is important to note as the UK is very different to the USA in terms of social norms and the delivery and provision of social services both through governmental and non-governmental charitable channels. This suggests a more universal nature to some of these findings and a need for more international exploration.

Characterizing this relationship raises a further question of identification and labeling of the person–animal relationship. There is debate over the term “pet owner,” and some have suggested that “pet guardian” may be more appropriate (Carlisle-Frank & Frank, Citation2006). “Owner” is the commonly used, accepted term in the UK, particularly as “guardian” is used as a legal term to describe a child’s carer. Whichever term is used, this should not diminish the recognition of the H-CAB, which may be particularly important to vulnerable populations such as these. Although asking participants to label or define their relationship in this way was not explored in this study, it may be a useful and interesting area of future enquiry.

The present study also identified two other important themes which have not been previously recognized: “anticipatory grief” and “mutual rescue.” For some owners, particularly as their dogs age, anticipatory grief may be an important consideration, especially for those who are psychologically vulnerable. This suggests the need for intervention and further support for these owners, such as access to pet bereavement counseling (Hewson, Citation2014; Morley & Fook, Citation2005). The narrative of mutual rescue was an interesting finding, which somewhat expands previous observations that pet ownership provides an opportunity for homeless people to construct a positive personal discourse (Thompson et al., Citation2014).

Limitations

This study is based on a relatively small sample size; although in the context of accessing a vulnerable and hard to reach group, this study still provides a useful data set. Due to the practicalities surrounding recruitment, many of the participants were in some form of temporary housing at the time of the interview, meaning they were by definition successful in finding dog-friendly accommodation, albeit not secure. Furthermore, this sample is self-selecting in that participation was voluntary; participants may therefore have been the more motivated dog owners, which means that these findings cannot be uncritically generalized to the homeless population in the UK or beyond.

Whilst the current paper did not look at how participants used discourse to make their arguments, further studies could adopt this more constructivist perspective in order to understand this aspect of the H-CAB more fully. More broadly, we hope that this work encourages social scientists and others to explore the role of animals in human health and social care (see Hobson-West & Jutel, Citation2020).

Conclusion

Overall, the analysis has shown that for this sample of homeless dog owners the relationship with their dog is crucially important to them. The analysis also points to the positive impact on health and behavior for dog owners. Homeless pet owners in the UK have been little studied to date, and this work has identified an important gap in services and a need for a One Health approach by policymakers. This will be brought into especially sharp relief given the likely social and economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. The stigma surrounding homelessness and dog ownership could be addressed by recognizing the importance of the H-CAB, both to animal and human health. In terms of policy, reducing barriers to essential services would help to ensure that homeless pet owners are not forced to choose between a roof over their head and their animal – which for many can potentially perpetuate their homeless situation.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by Dogs Trust.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bender, K., Thompson, S. J., McManus, H., Lantry, J., & Flynn, P. M. (2007). Capacity for survival: Exploring strengths of homeless street youth. Child and Youth Care Forum, 36(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-006-9029-4

- Bhugra, D. (2007). Homelessness and mental health. Cambridge University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140

- Carlisle-Frank, P., & Frank, J. M. (2006). Owners, guardians, and owner-guardians: Differing relationships with pets. Anthrozoös, 19(3), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279306785415574

- Charles, N., & Davies, C. A. (2008). My family and other animals: Pets as kin. Sociological Research Online, 13(5), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1798

- Cleary, M., Visentin, D., Thapa, D. K., West, S., Raeburn, T., & Kornhaber, R. (2019). The homeless and their animal companions: An integrative review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00967-6

- Cronley, C., Strand, E. B., Patterson, D. A., & Gwaltney, S. (2009). Homeless people who are animal caretakers: A comparative study. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.105.2.481-499

- Fournier, A. K., Geller, E. S., & Fortney, E. V. (2007). Human–animal interaction in a prison setting: Impact on criminal behavior, treatment progress, and social skills. Behavior and Social Issues, 16(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.5210/bsi.v16i1.385

- Furst, G. (2007). Without words to get in the way: Symbolic interaction in prison-based animal programs. Qualitative Sociology Review, 3(1), 96–109.

- Harkrader, T., Burke, T. W., & Owen, S. S. (2004). Pound puppies: The rehabilitative uses of dogs in correctional facilities. Corrections Today, 66(2), 74–79.

- Hart, L. A. (2010). Positive effects of animals for psychosocially vulnerable people: A turning point for delivery. In A. H. Fine (Ed.), Handbook on animal-assisted therapy (pp. 59–84). Elsevier.

- Hemming, N. (2015). Homelessness and mental health. Retrieved from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/blog/homelessness-and-mental-health

- Hewson, C. (2014). Grief for animal companions and an approach to supporting their bereaved owners. Bereavement Care, 33(3), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682621.2014.9840985

- Hobson-West, P., & Jutel, A. (2020). Animals, veterinarians and the sociology of diagnosis. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(2), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13017

- Homeless_Link. (2014). The unhealthy state of homelessness: Health audit results 2014. Retrieved from https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/The%20unhealthy%20state%20of%20homelessness%20FINAL.pdf

- Howe, L., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2018). The perceived costs and benefits of pet ownership for homeless people in the UK: Practical costs, psychological benefits and vulnerability. Journal of Poverty, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2018.1460741

- Irvine, L. (2013). My dog always eats first: Homeless people and their animals. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Kerman, N., Gran-Ruaz, S., & Lem, M. (2019). Pet ownership and homelessness: A scoping review. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 28(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2019.1650325

- Lem, M., Coe, J., Haley, D., Stone, E., & O’Grady, W. (2016). The protective association between pet ownership and depression among street-involved youth: A cross-sectional study. Anthrozoös, 29(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2015.1082772

- London, J. (1992). Homeless mentally ill or mentally ill homeless? American Journal of Psychiatry, 149(6), 816–823. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.149.6.816

- McBride, E. A., & Montgomery, D. J. (2018). Animal welfare: A contemporary understanding demands a contemporary approach to behaviour and training. People and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 1(1), https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/paij/vol1/iss1/4

- McCrave, E. A. (1991). Diagnostic criteria for separation anxiety in the dog. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 21(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-5616(91)50030-9

- McNicholas, J., & Collis, G. (2000). Dogs as catalysts for social interactions: Robustness of the effect. British Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712600161673

- McNicholas, J., Gilbey, A., Rennie, A., Ahmedzai, S., Dono, J.-A., & Ormerod, E. (2005). Pet ownership and human health: A brief review of evidence and issues. BMJ, 331(7527), 1252–1254. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1252.

- Morley, C., & Fook, J. (2005). The importance of pet loss and some implications for services. Mortality, 10(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270412331329849

- NVivo 10 [software program]. Version 10. QSR International; 2012.

- Rhoades, H., Winetrobe, H., & Rice, E. (2015). Pet ownership among homeless youth: Associations with mental health, service utilization and housing status. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46(2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0463-5

- Scanlon, L. (2017, February). Homeless people, their pets and animal welfare. Association of Charity Vets, Wood Green Animal Shelter.

- Scott, J. (1993). Homelessness and mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 162(3), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.162.3.314

- Shelter. (2018a). Homelessness in Great Britain – The numbers behind the story. Retrieved from https://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/1620236/Homelessness_in_Great_Britain_-_the_numbers_behind_the_story_V2.pdf

- Shelter. (2018b). The housing crisis generation: How many children are homeless in Britain. Retrieved from https://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1626466/The_housing_crisis_generation_-_Homeless_children_in_Britain.pdf

- Siegel, J. M. (1990). Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: The moderating role of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1081–1086. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.58.6.1081

- Singer, R. S., Hart, L. A., & Zasloff, R. L. (1995). Dilemmas associated with rehousing homeless people who have companion animals. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 851–857. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.851

- Thomas, B. (2012). Homelessness kills: An analysis of the mortality of homeless people in early twenty-first century England. Crisis. https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/236799/crisis_homelessness_kills_es2012.pdf

- Thompson, K., Every, D., Rainbird, S., Cornell, V., Smith, B., & Trigg, J. (2014). No pet or their person left behind: Increasing the disaster resilience of vulnerable groups through animal attachment, activities and networks. Animals, 4(2), 214–240. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/4/2/214

- Thompson, S. J., McManus, H., Lantry, J., Windsor, L., & Flynn, P. (2006). Insights from the street: Perceptions of services and providers by homeless young adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.09.001

- Wells, D. L. (2004). The facilitation of social interactions by domestic dogs. Anthrozoös, 17(4), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279304785643203

- Williams, D., & Hogg, S. (2015). The health and welfare of dogs belonging to homeless people. Pet Behaviour Science, 1, 1. http://doi.org/10.21071/pbs.v0i1.3998