ABSTRACT

Pets are often regarded as family members in US households, but are rarely examined as a source of support for individuals who are suicidal. As suicide rates increase, all potential protective factors must be explored. The attachment bond between pets and their owners is akin to that of bonds with other humans, as pets provide unconditional love and emotional support when owners experience distress. This qualitative study sought to discover and describe how adults perceive their pets when suicidal. Participants (n = 71; ages 18–49 years old) with recent experiences of suicidal thoughts or behaviors were recruited from mental health forums on a social media website, Reddit. Participants responded to an anonymous, open-ended survey about the role of their pets during a recent experience of suicidal thoughts or behaviors. A thematic analysis was conducted following the coding of responses. Three organizing themes, describing the roles of pets during the suicidal period, were identified: Protective Influence, No Role, and Risk Factor. Pets that provided a protective influence against the suicidality did so by providing comfort, a distraction, or a reason to live to their owners. Pets that were not present or did not influence their owners while suicidal were classified as no role. Finally, pets were regarded as a risk factor when they caused stress to their owners; health and behavioral problems were both cited as exacerbating the suicidality. These findings indicate the importance of assessing the role of pets in suicidal individuals’ lives. These results provide implications for the consideration of pets in suicide prevention and intervention efforts.

Over 63% of households in the United States include at least one pet, typically dogs and cats (American Pet Products Association, Citation2018). Pets are commonly considered close companions and important components of individuals’ lives (Ikram, Citation2005). However, pets’ roles are largely absent in research investigating individuals with suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Suicide is an increasing concern in the USA in all age groups: over 10 million individuals are estimated to experience suicidal thoughts each year, while 1.4 Americans made suicide plans or attempts in the past year (SAMHSA, Citation2019). Pets (also known as companion animals) of many varieties have the potential to provide comfort, company, and security to humans, particularly those with mental health conditions (Brooks et al., Citation2018). Despite their apparent benefits, pets are rarely included in studies examining families and even less in studies surrounding suicidality; thus their potential impact on suicidality is currently unknown. This qualitative study aimed to bridge this gap by analyzing the role of pets in adults’ recent experiences of suicidal thoughts or behaviors via an online survey distributed on a popular social media site, Reddit.

Pets as Companions

Pets are often regarded as family members who play a vital role in humans’ lives and mental wellbeing (Walsh, Citation2009). The value of pets as companion animals (particularly cats and dogs) dates back to ancient Egypt and beyond (Ikram, Citation2005). Many pets are able to detect and respond to human emotional cues, leading some individuals to prefer animal companionship over human companionship due to the perceived acceptance and lack of judgement experienced from their pet (Plakcy & Sakson, Citation2006). Many people report that their pets provide comfort during challenging periods of their lives, such as when facing interpersonal difficulties, the death of a loved one, or the loss of a job (Risley-Curtiss et al., Citation2006; Walsh, Citation2009). Furthermore, individuals who keep pets are likely to have improved physiological and mental health compared to those without pets (Friedmann & Tsai, Citation2006; Headey & Grabka, Citation2007; Virues-Ortega & Buela-Casals, Citation2006). Dogs, in particular, have been found to reduce loneliness (Powell et al., Citation2019).

Pets can offer unconditional love and acceptance that differs from the relationships formed with other humans (Levinson, Citation1969), similar to a parent–child relationship as opposed to that of a friendship or romantic relationship. Pets have the potential to provide emotional support, which can buffer the effects of rejection from others (McConnell et al., Citation2011). Based on previous research, people with strong bonds with their pets are more likely to turn to pets for support instead of other individuals in their lives (Kurdek, Citation2009). Pets’ provision of social support may be particularly valuable to suicidal individuals, who may refrain from consistently reaching out to human supports for the fear of burdening others (Joiner, Citation2007).

To provide context for the importance of human–pet bonds, Zilcha-Mano et al. (Citation2011a) applied attachment theory to this relationship. Pets can be viewed as attachment figures the same way humans can due to their ability to provide a safe haven and secure base for their owner. In addition to their constancy, pets provide affection and are responsive to human cues, furthering their commonalities with other attachment figures (Kurdek, Citation2008). In a study measuring attachment security to pets, individuals’ attachment patterns (i.e., secure and insecure) to their animals were similar to their attachment patterns to other people in their lives (Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2011b). Secure attachment with pets is theorized to set an attachment foundation, which can then be transferred to other interpersonal relationships (Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2011a). In other words, as individuals feel comforted and accepted by their pet, they may engage in vulnerability with others. This provides a potential new avenue through which pets can be utilized in therapeutic settings or to better understand individuals’ relationships.

Pets and Mental Health

Although the role of pets has not been extensively explored in studies examining suicidality, pets have been included in studies aimed at reducing depressive symptoms or improving mental health. For instance, Pereira and Fonte (Citation2018) discovered that patients who adopted an animal in addition to their participation in pharmacotherapy resulted in reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to the patients who engaged in pharmacotherapy only. The therapeutic benefit of animals has been shown through the increasing use of emotional support animals and animal-assisted therapy. Animal-assisted therapy (AAT), in particular, has been associated with improved emotional wellbeing (Nimer & Lundahl, Citation2007) and decreases in depressive symptoms (Souter & Miller, Citation2007), highlighting the impact of animals and indicating a promising option for decreasing suicidality.

In non-clinical populations, pets also serve a vital role. Several studies describe the significant emotional role of pets in the lives of individuals in grim circumstances, particularly those who are isolated. In one study (Fitzgerald, Citation2007), women in abusive relationships described their pets as a lifeline and their sole source of support. So important were pets to these women that nearly half the sample delayed leaving the abusive relationship, typically due to partner’s control of the pet or because the pet could not accompany the women to a shelter. Several of the women in the study indicated that they would have attempted suicide to escape the relationship had it not been for their pets; one participant did attempt suicide following the death of her kitten (Fitzgerald, Citation2007). Studies examining homeless individuals identified similar findings: many individuals, regardless of age and gender, would prefer to stay homeless if it keeps them with their pets (Lem et al., Citation2013; Singer et al., Citation1995). While not specifically assessing for pets’ roles in suicidality, these studies illuminate the importance of pets in the lives of those who are struggling and isolated.

Thus far, the association of pets as a protective factor against suicide is identified in studies with older individuals (Deuter et al., Citation2019; Figueiredo et al., Citation2015; Young et al., Citation2020), but not in any younger populations. To date, no study exploring the role of pets in suicidality has been conducted on adults throughout the lifespan. As each of the aforementioned studies revealed pets can decrease isolation and provide some form of purpose for suicidal older adults, determining if pets serve a similar role in younger populations is a natural progression of research.

Despite its lack of exploration, the assumption of consistency and reliability that pets provide their owners is commonly regarded as a protective factor against suicide. The assumption is that people will be less likely to die by suicide if they have a purpose or reason to live, including responsibility for a pet. As a result, pet ownership is now included as a screening question in select suicide assessments (e.g., the Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage [SAFE-T]). However, pets can also be a risk factor for suicide – the relationship for some individuals is so significant that when the animal dies, they may experience despair akin to the loss of a family member (Carmack, Citation1985). This despair is associated with substantial disruptions in individual and family functioning (Carmack, Citation1985) and may even become a catalyst for suicide attempts (Fitzgerald, Citation2007). Furthermore, there are several cases in which individuals killed their pets in preparation for or during their suicide, not dissimilar to homicide-suicide or filicide-suicide (Cooke, Citation2013). Thus the presence of a pet alone does not provide enough information about the relevance of pets in suicidality and warrants further investigation. This qualitative study sought to explore the role of pets in adults’ lives during a recent suicidal period to determine how the pet was perceived during this time.

Methods

This study was included as part of a larger project. The parent project received institutional review board approval from the primary investigator’s institution at the time of data collection. Participants were recruited through an online social media site, Reddit, the fifth most popular website in the United States. According to Pew Research Center (Citation2019), at least 11% of Americans regularly access Reddit. Reddit is an anonymous discussion-oriented website that allows users to join forums and create posts or respond to one another in comment threads. Reddit was selected as a recruitment site due to the anonymity of users and ample mental health-related pages (also known as “subreddits”). The stigmatization of mental health, particularly with topics such as suicidality, may lead individuals to be wary of discussing mental health on sites in which their identity is known to others (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, etc.). Thus Reddit is an appealing space for those looking to learn more about mental health or disclose their mental health concerns to others without fear of identification or judgement (De Choudhury & De, Citation2014).

Recruitment messages were approved by subreddit moderators before being posted on eight Reddit pages related to mental health. Recruitment messages posted once on each page and included a brief message describing the eligibility criteria and goal of the parent study. Eligibility criteria for participation included those who were over the age of 18, lived in the United States, had experienced at least one period of suicidal thoughts or behaviors since the age of 18, and were not currently suicidal. Participants who elected to participate responded to a brief, open-ended Qualtrics survey. The survey asked participants about their most recent experience of suicidality: participants responded to questions about whether or not they disclosed their suicidality to anyone in their lives and described the role of influencing factors during their suicidal period, including pets.

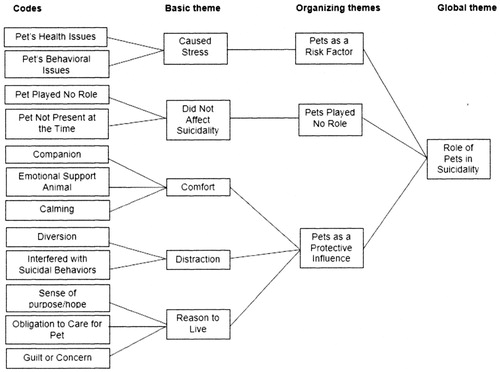

In the present study, only participants, who responded with whether or not they had pets at the time of their most recent suicidal experience, were included. These participants were provided this single open-ended prompt about their pets which is the basis of the present study: “What role did your pets have in your life at the time you were experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors?” The average length of participant response to this question was 19.09 words. The primary researcher and an undergraduate research assistant followed the six steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). They independently conducted a preliminary descriptive coding of the responses, then together compiled a codebook based on the independent observations. Data were then reviewed and recoded until consensus was reached. An inductive thematic analysis was conducted following the coding. Three organizing themes were determined from the data, each with their own supporting basic themes.

Participants

The parent study for this article included 121 individuals; however, only those who had pets at the time of their most recent suicidality were included in the present study, resulting in a sample of 71 participants. This study consisted of 46 (64.8%) women, 20 (28.2%) men, and 5 (7.0%) described themselves as either genderfluid or nonbinary. The average age of participants was 26.9 (SD = 7.6, range = 18–49). Participants selected all racial categories to which they belonged, resulting in 64 (90.1%) White (8 [11.3%] identified as White and another race), 9 (12.7%) Asian, 3 (4.2%) Black, 3 (4.2%) Hispanic or Latino, 1 (1.4%) Native American/Indigenous/Alaskan Native, and 1 (1.4%) Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander participant. Interestingly, only slightly over half of the sample identified as heterosexual (n = 39; 54.9%). A significant number of participants identified as bisexual or pansexual (22; 31.0%), followed by lesbian (n = 4, 5.6%), gay (n = 2; 2.8%), or other (n = 4, 5.6%). The majority of participants’ most recent experiences of suicidality took place within the past year, followed by the past 2 years. In their most recent experience of suicidality, 26 (36.6%) had suicidal thoughts only, 34 (47.9%) had suicidal thoughts with a plan or intent, and 11 (15.5%) attempted suicide.

Results

The majority of participants reported only owning one type of pet during their recent experience of suicidality. Most commonly reported was cats (n = 31; 43.8%), followed by dogs (n = 25; 35.2%). Few participants owned other types of animals, including rodents (n = 5, 7.0%), rabbits (n = 3; 4.2%), fish (n = 2; 2.8%), birds (n = 1; 1.4%), and horses (n = 1; 1.4%). One-fifth (n = 14) of participants had more than one species of pet. The number of total pets in each participant’s household was not requested in this study. A portion (n = 7; 9.9%) of the participants’ responses could not be coded due to providing too little information or a lack of clarity in their pets’ roles. Three organizing themes were developed following coding: Pets as a Protective Influence, Pets Played No Role, and Pets as a Risk Factor (see ).

Pets as a Protective Influence

The organizing theme Pets as a Protective Influence included the largest portion of the participants’ responses (n = 50; 70.4%). This organizing theme was made up of three basic themes, each of which indicated protective influence while the participants were experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors. The basic themes identified were pets provided comfort, a distraction, or a reason to live.

Comfort: The first basic theme, pets provided comfort, included three codes: companionship, emotional support, and calming. Companionship was often described by as the pet was a friend and provided support. Several participants felt their pet was their only companion (“They felt like my only friends at times and were a huge part of my life. Sometimes they would be the only reason I wouldn’t attempt suicide”), while others described how their pet helped them when they were upset (“Support and companionship, someone I always had around to talk to or just hug until I stopped crying”). Participants who described their pet as emotional support either stated their pet was an emotional support animal (e.g., an animal that provides comfort or emotional assistance to their owner), while others stated “emotional support” without additional information. The final code for comfort was pets that were calming to their owners, such as “Petting one of the cats was (and still is) an excellent way for me to calm my mind.”

Distraction: The second basic theme identified was pets provided a distraction. Distraction came in two forms for participants, coded as diversion and interference. Diversion referred to pets’ needs or behaviors eliciting a response from the participants, such as this quote:

My cat was very playful and would want to play with me so he would literally pull me out of an intense suicidal state for a few minutes to play with him. He helped me focus on something that wasn’t myself and my agony.

The interference codes displayed the influential role of pets as protective features against suicidal behaviors. This quote, “When I attempted to jump out of my window (after a few weeks of carefully taking it apart) my dog was just so upset. She was crying in the far corner of my apartment. I couldn’t follow through” described the emotional impact of the pet’s presence, while the participant was suicidal. Other pets interfered more directly, such as this participant’s cat:

When I moved back in with my parents she often kept me from going over the edge. She’s often taken baths with me when I’ve felt overwhelmed, has knocked blades out of my hand (by demanding attention instead).

Another participant described the continued importance of having pets during suicidal behaviors:

In an earlier attempt at suicide, my first cat walked in and snapped me out of the dissociation I was experiencing at the time. I remember ‘waking up’ with a knife to my wrists sobbing heavily. This is the exact reason I still have cats today. They are good distractions and a source of reality for when you drift too far away.

As seen from these participants’ responses, pets that provided a distraction played a significant role in reducing suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

Reason to Live: The final basic theme in Pets as a Protective Influence was pets provided a reason to live. Participants who indicated their pets provided a sense of purpose or hope, who felt obligation to care for the pet, or felt concern or guilt about what would happen to the pet if the participant died were included in this theme. Participants who described their pets as providing a sense of purpose in their lives were likely to indicate that their pet was the only thing keeping them alive: “My dogs are and were my lifeline. I am here because of them, I love them more than anything” and “She was my best friend. Really the only thing that kept me going day to day and made me get out of bed.” Participants who felt obligation to the pet did so because they were the primary caretaker and did not want to abandon the animal, or because they desired to continue caring for the pet: “I need to stay around so I can feed her. She also wouldn’t know where I went.” Other participants indicated they were concerned or would feel guilty about the confusion they anticipated the pet would experience if they died by suicide: “I loved my cat and felt bad that I would die and leave her. Having a cat now is a huge comfort when I'm depressed.” Finally, some participants’ responses were vague but nevertheless indicated the significant role of their pet in their fight to stay alive: “I looked at my dog and told her ‘I'm trying so hard for you.’”

Pets Played No Role

Participants who made statements to the effect of “they’re just pets,” “none,” or “I guess I’ve never considered their role” were coded as no role. Other participants indicated that their pet was not with them at the time of the suicidality, thus coded as pet was not present. Both codes, no role and pet was not present, were included in the organizing theme Pets Played No Role (n = 10; 14.1%).

Pets as a Risk Factor

The final organizing theme, Pets as a Risk Factor, was developed due to the few participants who felt their pets caused stress or were triggering while they were suicidal (n = 4; 5.6%). These responses were organized in one basic theme, pets cause stress. This theme summarized how stress caused by the pets often exacerbated participants’ difficulties while they were suicidal. This basic theme included two codes, pet health issues (“They are old and sickly so they made me sad also”) and behavioral issues (“I’m stressed because my cat’s behavior has changed in the last 12 months. She is always making messes”). Health or behavioral issues either caused frustration to the participant or elicited sadness, both of which compounded the difficulties already experienced by the participant. One participant described how her sick dog triggered her suicidality; she surrendered him after voluntarily hospitalizing herself, but went on to explain how her cat kept her company and kept her alive after the dog was gone. This participant’s response was the only one coded in both the Risk Factor and Protective Influence organizing themes due to the complexity of her experiences with her pets.

Discussion

In this sample, pets were overwhelmingly reported to be a positive presence in participants’ lives at the time they were experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors. This study revealed specific means through which pets can provide protection to suicidal individuals, whether that be comfort, providing a reason to live, or creating a distraction. It is important to note, however, that pets are not always a protective feature: a moderate portion of this sample did not subscribe any role to their pets, and a small portion even described their pets as increasing their stress at the time of their suicidality. Thus not all pet owners perceive their pets to be a protective influence when in crisis; research and interventions should be wary of approaching them as such.

From an attachment framework, pets may be experienced as a safe haven or secure base. Individuals who feel positively toward their pets are likely to feel their pet is a constant in their life that offers unconditional love and support (Levinson, Citation1969). This is of particular importance for individuals with suicidal thoughts or behaviors who feel stigmatized or judged. This was exemplified in this study, in that many participants referred to their pet as their only friend or best friend. These responses indicate that perceived outside social support is likely low and that the relationship with their pet is of vital importance. However, individuals who are able to form a strong bond with pets may have the potential to create more secure bonds in other relationships (Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2011a). As the attachment style developed with a pet is similar to that developed with other people, the foundation for forming positive relationships is indicated in these individuals. Due to this, individuals who have strong bonds with their pets may have the potential for acquiring additional social support in future relationships if the opportunities are presented. This could take place in therapy settings or in less formal supportive relationships, such as with friends or family members.

For individuals with suicidal thoughts or behaviors presenting in mental health treatment or in research studies, assessments are recommended to discern how the individual perceives the role of their pet before concluding that the presence of pets protects the individual. Pets may be perceived as a stressor or burden to the individual, heightening their risk for suicide. Individuals who perceive their pets this way may feel relief if the pet is no longer in their household. On the other hand, the individual may be at increased risk for suicide following the removal of the pet; although the pet may have been a stressor, it may also have provided structure and responsibility to the individual. Additionally, individuals for whom pets are protective influences may be at heightened risk for increased suicidality if the pet dies or is removed unexpectedly, as indicated as an option by one participant in this study.

Consistent with previous findings in older populations (Young et al., Citation2020), pets provided comfort and structure for many adults’ lives in this study. This study expanded on previous research by incorporating younger adults. Pets were frequently regarded as companions and friends, to the extent that participants would communicate with their pets or rely on their pets for emotional support. Participants commonly expressed love and commitment to their pets, which provided a significant protective influence in the individuals’ lives at the time of suicidality. The participants often indicated that their pets were aware of when they were in distress and would provide comfort accordingly. For several individuals in the study, this even became a deterrent from suicidality, either via the calming effect of the animal or because the animal interfered (directly or indirectly) with suicidal thoughts or actions. Individuals who were experiencing other depressive symptoms described how having a pet gave them a reason or necessity to function appropriately, such as getting out of bed, taking care of the animal and themselves, or going outside. Thus even when suicidality is not pressing, the presence of pets can also aid individuals in combatting depressive symptoms.

Limitations and Future Research

While Reddit provided anonymity and an outlet for participants to disclose mental health concerns, this study’s participants were overwhelmingly White (including bi-racial) and majority female. However, this sample also included a higher than average proportion of gender and sexual minorities. Participants were recruited on the basis of recent experiences with suicidal thoughts or behaviors, so the higher than average response rate of gender and sexual minorities is likely a reflection of those groups’ increased risk for suicide (Haas et al., Citation2011). This study was also limited by the retrospective accounts of the pets’ roles in the most recent period of suicidality (majority of which had occurred within the past 1–2 years), which may influence how the participants recall this information.

Based on the results of this study, future research is recommended to further explore the role of pets in other samples, including clinical samples and samples with increased diversity. The role of pets is likely to differ based on cultural values, financial security, and availability of social supports, so addressing whether pets provide protective influence in additional groups is necessary. Future research is also recommended to assess interventions with pets in pursuit of decreasing suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Animal-assisted therapy programs, while valuable, do not involve pets who are in the home and owned by the individual. Therefore, these programs are not assumed to provide the same potential benefits as those identified in this study. At least one study thus far found improvements in a clinical population being treated for depression when pets were introduced (Pereira & Fonte, Citation2018); it is possible similar results may occur when applied to individuals with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The acquisition of pets or other care of animals (e.g., fostering an animal or volunteering at an animal shelter) may provide suicidal individuals a sense of purpose or comfort and could be considered in future interventions. However, as revealed in this study and in previous research (Cooke, Citation2013; Fitzgerald, Citation2007), the possibility of risk to the individual or the animal must be addressed in the planning, assessment, and implementation of such interventions.

Conclusion

The perceived role of pets for individuals experiencing suicidality has not yet been explored in the depth encompassed in this study. Participants overwhelmingly indicated pets were a positive influence in their lives at the time of their suicidality, to the point that several described their pet as their only reason for living. However, pets with health or behavioral problems were perceived as stressors to participants during their suicidal experience, sometimes to the point of increasing their suicidality. Another portion of individuals in this study indicated that their suicidality was unaffected by the presence of the pet. Results of this explorative qualitative study reveal the need for additional assessment of pets in the lives of those with suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Additionally, this study describes the potential for pets to be incorporated (with careful assessment and monitoring) in innovative approaches for reducing suicidality or depression in clinical and non-clinical settings alike.

Acknowledgement

I thank Grace Benevicz for her valuable contributions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- American Pet Products Association. (2018). The 2017–2018 APPA National Pet Owners Survey Debut. Available at https://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brooks, H. L., Rushton, K., Lovell, K., Bee, P., Walker, L., Grant, L., & Rogers, A. (2018). The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 18(31), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2

- Carmack, B. (1985). The effects of family members and functioning after the death of a pet. Marriage and Family Review, 8(3–4), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v08n03_11

- Cooke, B. K. (2013). Extended suicide with a pet. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 41(3), 437–443.

- De Choudhury, M., & De, S. (2014, May). Mental health discourse on Reddit: Self-disclosure, social support, and anonymity. Paper presentation at the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and social media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA June 1-4, 2014.

- Deuter, K., Procter, N., & Evans, D. (2019). Protective factors for older suicide attempters: Findings reasons and experiences to live. Death Studies, 44(7), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1578303

- Figueiredo, A. E. B., da Silva, R. M., Vieira, L. J. E. S., do Nascimento Mangas, R. M., de Sousa, G. S., Freitas, J. A., Conte, M., & Sougey, E. B. (2015). Is it possible to overcome suicidal ideation and suicide attempts? A study of the elderly. Ciencia and Saude Coletiva, 20(6), 1711–1719. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015206.02102015

- Fitzgerald, A. J. (2007). “They gave me a reason to live”: The protective effects of companion animals on the suicidality of abused women. Humanity and Society, 31(4), 355–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/016059760703100405

- Friedmann, E., & Tsai, C.-C. (2006). The animal–human bond: Health and wellness. In A. Fine (Ed.), Animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and practice guidelines (2nd ed (pp. 95–117). Academic Press.

- Haas, A. P., Eliason, M., Mays, V. M., Mathy, R. M., Cochran, S. D., D’Augelli, A. R., Silverman, M. M., Fisher, P. W., Hughes, T., Rosario, M., Russell, S. T., Malley, E., Reed, J., Litts, D. A., Haller, E., Sell, R. L., Remafedi, G., Bradford, J., Beautrais, A. L., … Clayton, P. J. (2011). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1), 10–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.534038

- Headey, B., & Grabka, M. M. (2007). Pets and human health in Germany and Australia: National longitudinal results. Social Indicators Research, 80(2), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5072-z

- Ikram, S. (ed.). (2005). Divine creatures: Animal mummies in ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press.

- Joiner, T. (2007). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

- Kurdek, L. A. (2008). Pet dogs as attachment figures. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(2), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507087958

- Kurdek, L. A. (2009). Pet dogs as attachment figures for adult owners. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014979

- Lem, M., Coe, J. B., Haley, D. B., & Stone, E. (2013). Effects of companion animal ownership among Canadian street involved youth: Qualitative analysis. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 40(4), 285–304. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol40/iss4/15.

- Levinson, B. M. (1969). Pet-oriented psychotherapy. Charles C. Thomas Publisher.

- McConnell, A. R., Brown, C. M., Shoda, T. M., Stayton, L. E., & Martin, C. E. (2011). Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownerships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1239–1252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024506

- Nimer, J., & Lundahl, B. (2007). Animal-assisted therapy: A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös, 20(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279307X224773

- Pereira, J. M., & Fonte, D. (2018). Pets enhance antidepressant pharmacotherapy effects in patients with treatment resistant major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.07.004

- Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. (2019). Who uses YouTube, WhatsApp and Reddit. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/chart/who-uses-youtube-whatsapp-and-reddit/.

- Plakcy, N. S., & Sakson, S. (2006). Paws and reflect: Exploring the bond between gay men and their dogs. Alyson Books.

- Powell, L., Edwards, K. M., McGreevy, P., Bauman, A., Podberscek, A., Neilly, B., Sherrington, C., & Stamatakis, E. (2019). Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: A community-based three-arm controlled study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1428. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7770-5

- Risley-Curtiss, C., Holley, L. C., Cruickshank, T., Porcelli, J., Rhoads, C., Bacchus, D., Nyakoe, S., & Murphy, S. B. (2006). “She was family”: women of color and animal–human connections. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 21(4), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109906292314

- Singer, R. S., Hart, L. A., & Zasloff, R. L. (1995). Dilemmas associated with rehousing homeless people who have companion animals. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 851–857. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.851

- Souter, M. A., & Miller, M. D. (2007). Do animal-assisted activities effectively treat depression? A Meta-Analysis. Anthrozoös, 20(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303707X207954

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/key-substance-use-and-mental-health-indicators-in-the-united-states-results-from-the-2018-national-survey-on-Drug-Use-and-Health/PEP19-5068.

- Virues-Ortega, J., & Buela-Casals, G. (2006). Psychophysiological effects of human–animal interaction: Theoretical issues and long-term interaction effects. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000195354.03653.63

- Walsh, F. (2009). Human–animal bonds I: The relational significance of companion animals. Family Process, 48(4), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01296.x

- Young, J., Bowen-Salter, H., O’Dwyer, L., Stevens, K., Nottle, C., & Baker, A. (2020). A qualitative analysis of pets as suicide protection for older people. Anthrozoös, 33(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2020.1719759

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2011a). Pet in the therapy room: An attachment perspective on animal-assisted therapy. Attachment and Human Development, 13(6), 541–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2011.608987

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2011b). An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(4), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.04.001