Abstract

West African informal collective institutions have much to offer the study of international development. Susu is the local name for a cooperative system involving rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) practiced by millions of people. This essay argues that the Ghana susu are community economies, drawing on J. K. Gibson-Graham’s theory of community economies and its ethical principles for amplifying well-being, conducting ethical business, encountering others, and the joyful commoning of goods. The essay’s primary research was carried out in a community with forty-six susu members, through focus-group discussions and individual interviews in Accra, Tema, Cape Coast, and Kumasi. By acknowledging the susu system, the essay advances ideas of equity and highlights the African contribution to a sustainable economic model. The Ghana susu have a long-standing history of solidarity economics rooted in mutual aid, self-sufficiency, and the collective, and this history should be noted as a powerful antidote to neoliberal development.

Noncapitalist economies have long existed in Africa and many other parts of the world. However, they have been overshadowed because a dominant ideology seeks to “dissolve alterity” to the point of supporting a unitary and dominant notion of economy that renders all competing logics invisible (Bauman Citation1993). The result of a domineering free market is the undermining of community-based institutions (Firat and Venkatesh Citation1995; Shiva Citation2020; Gibson-Graham and Dombroski Citation2020). Calls for recognizing economic systems that vary from the dominant capitalist market have been getting louder, particularly those of feminist scholars (e.g., Gibson-Graham Citation1996; Kinyanjui Citation2019; Lloveras, Warnaby, and Quinn Citation2019; Mullings Citation2021). In this essay we situate the longstanding practice of solidarity economies, specifically rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs), among Ghanaians, but we also recognize them among African-descended people elsewhere. We wish to ensure these contributions are noted in the community-economies literature.

Susu—a centuries-old financial system in Ghana that prioritizes community over pecuniary benefits—promises an imagined alternative financial system that could be the reality for many people around the world. Development-studies expert Kalpana Wilson (Citation2015) has exposed the racial bias taking place within the field and reveals that Black, indigenous, and racialized women are doing community development whether we see it or not. Vandava Shiva (Citation2020) likewise finds that this understanding that cooperation is rooted in local knowledge is not new. We argue that rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) are a cooperative model that contributes to a socially and environmentally just world and that community-economies theories can be useful in locating African origins in our understanding of economic alternatives. Further, through interviews with susu members across cities in Ghana, we show the susu system’s ethical orientation in the financial sector.

The work of J. K. Gibson-Graham (Citation1996, Citation2008) and others has extended this morality beyond immediate dependents to include entire communities, based upon the acknowledgement of social interdependency beyond the household. Their work insists on ethical axioms to orient the economy. Inherent in these concerns are issues of “community” and ethics that conjure an understanding of people coming together through cooperation and mutual social relations rooted in trust and geared toward enhancing the commons (Glynn Citation2019). But also important for us is the work of C. Y. Thomas on the tradition and ethics of African diasporic peoples and their own self-development.

We draw on purposefully traditional business approaches that are not fixated on market returns but on the collective. In 2017 and 2018, we interviewed susu members who stated that their economic practices contribute to bottom-up development. This finding is particularly useful as part of a larger conversation about degrowth as a people-led and locally situated development (Ostrom Citation1990; Escobar Citation2020). African people’s economics is not only about meeting survival but is also about choice, well-being, and local development (Kinyanjui Citation2019; Koto Citation2015).

Mary Njeri Kinyanjui (Citation2019) has made it pointedly clear that Kenyan women have always created markets, through money groups called chamas, and that these women are not trying to comply with individualistic types of businesses. In following suit, we extend the boundaries of the community-economies literature to embrace moral economic dimensions such as “trust,” “reciprocity,” “solidarity,” and “joy.” Those of us in the Community Economies Research Network (known as CERN) have envisioned African people’s ideas as critical for considering the ethical components of forming community economies. In this essay, we investigate the extent to which the principles of a moral community economy are represented in the practice of susu, to see whether democratic and equitable participation emerges.

Our essay begins with a conceptual clarification of terms. We first define the meaning of ROSCAs from within an African context, and in the second section we explain the position of the susu system in Ghana. The third section anchors the susu system in the diverse- and community-economies theory of J. K. Gibson-Graham. For understanding susu and their location in the literature, we use the work of Guyanese Marxist economist C. Y. Thomas (Citation1974) to show why local economic development should be emphasized to counter extractive market systems. The fourth section reports on our in-person individual interviews and focus groups in Accra, Tema, Kumasi, and Cape Coast in Ghana to hear directly from the users of the formal and informal susu systems. In the final section, we work through the implications of our empirical findings.

Defining Rotating Savings and Credit Associations

ROSCAs bring together a group of people to voluntarily pool resources that allow them to function as financial institutions. In their foundational book Money-Go-Rounds, Shirley Ardener and Sandra Burman (Citation1996) noted that ROSCA functions vary from place to place, but they all follow a process of community-based organizing and meeting to support members. While many contemporary ROSCAs focus on mobilizing financial resources, some are also involved in projects aimed at achieving social goals (Bouman Citation1977, Citation1995). Members would normally agree to meet for a defined period to decide how to save and borrow together, a form of combined peer-to-peer banking and peer-to-peer lending (Ardener Citation1964). Exchange of goods and services is based on principles of reciprocity and morality, and those engaged in ROSCA systems rely on each other for both business and moral support.

While the origins of ROSCAs are still being debated, there is no doubt about their global presence. In Africa, Ethiopia has traditions of equub, idir, and wenfel that are informal cooperative systems in which people share economic goods to uplift a community (Kedir and Ibrahim Citation2011). In the Caribbean and Canada, Black women are leading ROSCA systems to do business, share ideas, and build a strong civic society rooted in reciprocity and mutual aid.

What Are Susus?

Susu literally means “little by little” in Ghana’s Twi language. In the same language, it also means “to plan,” as in susu biribi. These two meanings together suggest that susu practices implore people to plan for the future: “Little by little,” as Ghanaians say. For many in Ghana, joining a susu is a way to make a living, but it is also how ordinary people live, especially women (Tufuor et al. Citation2015; Bonsu Citation2019; Sato and Tufour Citation2020). Susu groups offer a mutual-aid scheme whereby members make regular contributions that are aggregated and given to each member in turn over a defined period (Geertz Citation1962; Ardener and Burman Citation1996; Ansaful Citation2019). There is no standard method of deciding the order in which members receive funds. Sometimes it is based on need. The bulk sum allows members to accumulate capital, giving them relatively easier access to capital for business ventures and other needs. Members themselves decide on the rules for their group (Basu Citation2011).

Grounded in the African effort to maintain community life (Moyo Citation2011; Kinyanjui Citation2014; Hossein Citation2018), the Ghana susu prioritize community over pecuniary benefits, encouraging a moral economy that focuses on community well-being without necessarily compromising individual welfare. According to Ghanaian researcher Kwaku Asante-Darko (Citation2013), attempts at communal support among the Asante people date back to precolonial days, highlighting that building economies around the community has long been a way of life for the Ghanaian people.

Its existence outside of the formal and dominant market system makes the ancient practice of susu virtually invisible, so it may seem less relevant in the lives of its members. However, it is this informality that makes susu systems particularly useful to their members. For instance, such a system can mobilize quickly in support of members and their community without recourse to formal structures. Susu groups are socially desirable because through them social ties are recognized and social relationships are maintained.

Seeing below the Surface: The Susu as Community Economies

Referring to the head persons who lead these ROSCAs, susu mamas refuse to play into ideological debates; rather, they push aside the binary of capitalist versus socialist by shifting the understanding of local economic development, doing so from within the local group, to show that people in a community can bond together and think about local production that is not for profit (Thomas Citation1974). This practice of doing community economies predates the theories that have emerged out of the West.

Susu participants (mostly women) are putting to work concepts and practices coming from ubuntu and ujamaa as a guide to how they conduct business in society. In Tanzania, Julius Nyerere (Citation1968) championed the idea of villagization, which was rooted in the ancient principle of ujamaa. Mary Njeri Kinyanjui (Citation2019) holds that ujamaa, rooted in collectivity and economic cooperation, comes out of deeply embedded African cultural and communal practices such as ubuntu, the idea of a shared humanity. Ubuntu privileges principles such as altruism, collaboration, and obligation to help others get beyond their individualistic pursuits of material success (Kinyanjui Citation2019). Gambian scholar Njie (Citation2022) expounds on this idea of ubuntu as a theory to explain the osusu business model for women to be able to meet their livelihood needs when formal banks do not. This way of being—in a shared humanity—adds to Western theories about new economies. Susu and many other money-pooling systems try to establish inventorying and other shared ways in which people interact and engage in business in society.

In the Handbook on Diverse Economies, J. K. Gibson-Graham and Kelly Dombroski (Citation2020) affirm that, globally, people are remaking economies to suit their own local needs. Tying this “new” knowledge to earlier works by Thomas can only strengthen what the concept of community economies means to African and Black diasporic people. As Thomas (Citation1974) acknowledged when he was writing about development in the Global South, the known formal actors are a very small part of the global economy. For decades, feminists Gibson-Graham (Citation1996) have spoken to the astounding silence about the reality that the majority of market activities going on in our world are hidden from plain view.

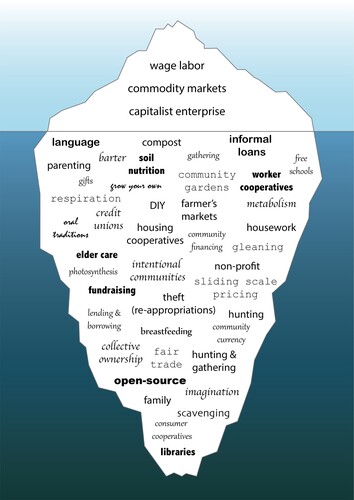

They liken this reality to an iceberg on which only formal markets are visible as the tip of the iceberg (see ).Footnote1 Submerged below the water is the living economy where most people interact with one another in crucial ways that support life. Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy’s (Citation2013) metaphor compels us to let go of the myth that only one form of economy exists when in reality all kinds of diverse economies exist beyond capitalist formal systems.

Figure 1. Diverse Economies Iceberg by Community Economies Collective. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. https://www.communityeconomies.org/index.php/resources/diverse-economies-iceberg

According to the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, about 88 percent of Ghana’s economy is informal (Anuwa-Amarh Citation2015; Koto Citation2015). This is an important part of the economy, whereas a world economy fixated on “formal” financial institutions distorts the reality. J. K. Gibson-Graham and the CERN iceberg analogy are meaningful here because all that is visible is a small part of the iceberg with the greatest chunk submerged below the ocean’s surface. In Ghana, however, this informal aspect of the submerged iceberg is what is mostly known to everyday people. It is not viewed as inferior but rather as a cooperative way of organizing resources.

Making Room for Black Political-Economic Theory

In the Global South, the dependency theories of the 1970s had much to say to counter Western yardstick ideas on development for “poor” countries. One such notable thinker was Guyanese Marxist economist C. Y. Thomas (Citation1988), who wrote, among many other major works, the foundational book The Poor and the Powerless, which examined colonization and world systems and their impact on the racially tiered class system in the Caribbean.

Thomas’s (Citation1974) earlier work, Dependency and Transformation: The Economics of the Transition to Socialism, pushed for local economic development for the Guyanese people as a way to refuse an extractive world system. Trinidadian sociologist Oliver Cox (Citation1948, Citation1964) wrote on the capitalist world system and how it left Caribbean and African countries out of the global economic system due to systemic exclusion from the very start. Adding this work to community economies, because bias and exclusion were crucial to development in a postcolonial context, is important for changing the nature of what is being performed in community-economies practices. We start to see the importance of performing both an antiracist and anti-imperialist politics inside postcapitalist politics.

Thomas (Citation1974) reasoned that when countries were focused on exports and buying imports, this was a “divergence”—a negative outcome. Conversely, “converging” meant the prioritization of local needs and producing what people needed in the community. Convergence theory is when ordinary people come together in carefully mediated ways to pool resources and to produce what they need. Thomas was calling for the convergence of domestic demand, domestic production, indigenous technology, and domestic resource use because capitalist economies will not reach the needs of all people. Likewise, the state and society should be ready for production that is focused on usage and not playing into a world system of profits.

Tying convergence theory to community-economies theory highlights both their differences and their shared localizing of people’s needs. Such theory, rooted in Black dependency thinking, is aligned with how susu women of Ghana and other susu members who have countered exclusionary markets have developed collective money systems to care about people’s local needs first. The susu system thrives on informality, and rather than ignoring what it has to offer, we need to recognize its nonconformist stand when it comes to development. Susu practices choose to help those excluded in business and society, offering both material and social gains. Susu, ROSCAs, and mutual aid groups are a part of the submerged iceberg—the part of the economy that is hidden.

Methods and Approaches

According to the Ghana Cooperative and Susu Collectors Association (GCSCA), created in 1994, at least 1,500 ROSCAs exist in Ghana, with just about 500 registered with the state’s regulatory bodies and central bank (Asamany, personal communication, 20 June 2017).Footnote2 These susu operators are local, and those that register their enterprises do so as a way of establishing credibility, which tends to serve the grassroots quite well (Koto Citation2015). To understand how ROSCAs operate efficiently on the margins, we focus on those outside the direct control of state authority. Though marginalized themselves, the members in these organizations help each other mobilize resources for petty trading, farming, fishing, or other economic activities. One group informed us that they may buy a used fridge for storing the fish or buying inventory in bulk so that they make more money. Through susu practices they ensure that ordinary people are able to participate in markets and that they have a place to share ideas with other likeminded citizens.

Who we are as authors mattered while conducting this research because talking about money is personal to many people. Sammy Bonsu is Ghanaian and grew up watching the women in his life use susu, which has deeply impacted his worldview in critical economy. Likewise, Caroline Shenaz Hossein, is part of the African Caribbean diaspora, and though born and bred in the United States and Canada, she has similarly watched those she knows use other versions of the susu system.

We collected data through long individual interviews and focus-group sessions with participants from 2017–18. This work received ethical approval in Canada and Ghana, and the interview tools were also submitted. At times, these interview tools were a hindrance to the actual trust-building and research process, and we had to engage in conversation with susu members on their terms, especially during the one-on-one interviews. The total set of informants comprised forty-six susu members (twenty-eight, or 61 percent, were women) from major cities in Ghana: Accra, Kumasi, Tema, and Cape Coast. The study is limited by its geographical focus, as it does not include susu from the northern regions of the country. However, lessons from this study will support further work focused on the north. The sources of data for the study are summarized in . The voices in this study are those of susu members who participate in the system; some have been susu members for decades.

Table 1. Authors’ Interviews with Ghanaians in Accra, Tema, and Cape Coast (June and July 2017) and Kumasi (May 2018 and October 2019)

We initially sought to explore the informality of the susu and why people see value in an informal banking system when there are so many commercialized banks within the different city centers. We had a question on the “political resistance” of using susu groups, which was relevant and needed in the Canada-based ROSCA project; however, the question made no sense in the Ghanaian context. Many susu members said they did not find the question useful because susu are widely accepted there, though the practice is still considered an informal institution.

The flexibility of asking questions and changing elements of the study allowed for the interview process to be relevant, and susu women helped shape the research in this regard. The overarching research questions for this study were as follows: “Why do Ghanaians still use the Susu system when modern banks are accessible in the city? How does Susu work for you and the people you know? How does Susu meet the business needs of its members?” We draw on the ethical coordinates of J. K. Gibson-Graham’s work to analyze the findings.

We held a focus group of twenty-three informants on 13 July 2017 in the community room of a local restaurant near the Makola market, the largest outdoor market in Accra, Ghana, so that participants could easily walk to the session, as the vendors had little time to spare. The nine men and fourteen women were between the ages of twenty-three and sixty-two and worked full time in the market, mostly buying and selling and providing services such as doing hair and nails. A female graduate student serving as a research assistant recruited informants through canvassing at the market, which she knew quite well. The participants answered open questions in turn, and at times the members in the group would debate a topic. The bulk of the interviews and focus-group discussions were in Twi, although some informants spoke pidgin English. The informants were leaders of susu groups that ranged in size from ten to sixty-five members, indicating that the twenty-three focus-group informants offer insights into the practices of many more people than were in attendance. Informants had intense discussions with the facilitators about the guiding questions. The session ran two hours, longer than expected because of the engagement of the participants and the need for translation. Informants joined the researchers for a meal after the session.

From 2017–19 we periodically carried out individual interviews with formalized susu enterprise owners and agents at four sites—Accra, Tema, Kumasi, and Cape Coast—while visiting either the members’ offices or homes. The aim of these in-depth interviews was to learn about the process of formalization in susu collectives and how formal collectives differed from informal ones. During two trips we carried out eight unstructured interviews, averaging about forty minutes each, with susu participants who were also market vendors in Kumasi. Informants were recruited through snowballing.

Findings: Susu Practices Align with the Ethical Principles of Community Economies

In this section, we group our findings into thematic sections to show how susu practices are very much at the core of building community economies. The members we met with were able to assist us in developing the key ideas for understanding how these financial systems function in society with regard to democracy building, governance, and self-help that all take place on people’s own terms.

The Mechanics of ROSCAs: How Do Susu Groups Operate?

There is no single method of operation when it comes to susu; they vary in structure, and rules may be customized by the individuals who constitute the group. However, common elements exist among them. Our informants epitomize the sharing economy (Belk Citation2010, Citation2014): they are not seeking profit but rather pool and share resources for the benefit of all members. The susu structure is democratic; members typically elect an executive board (e.g., president, vice president, treasurer, secretary) that is empowered to make routine decisions on behalf of the group. Major issues are brought to the membership for a decision by consensus or by vote, reflecting the values of the group. Consulting each other and debating issues are important ways for members to build and maintain trust and also to give each person a voice in the group’s affairs.

In a typical susu scheme, each member makes a fixed contribution to a “revolving” fund for a specific period (e.g., a weekly or monthly cycle). The fund is reallocated to members in turn, based on the group’s own predetermined criteria. For example, a susu works on a group model of, say, ten women who each make a monthly contribution of ten Ghana cedi (GH₵10) for a ten-month cycle, for the monthly total of GH₵100. One member of the group receives the GH₵100 each month, in turn, until over the ten-month cycle each person has received the “pot” or “hand” of GH₵100.

Importantly, each person has access to a bulk of funds that would otherwise not be available. Members use the money for sideline businesses, such as selling food, fish, clothing, or for personal reasons, such as paying for school fees, weddings, or funerals. Those who receive the funds early in the cycle may be considered to have borrowed money from the group while those who receive funds later are deemed savers; borrowers pay no interest and savers receive no interest income.

We observed that a susu allows for capital formation where members sacrifice potential financial interest and other earnings on their money, knowing fully that the accrued benefits may not be distributed equally among members. People care about each other and want to be part of an organization that has purpose beyond self-interest. The local banks pressure customers to buy things they don’t need, whereas a susu avoids people becoming overly indebted. The success of susu has led to immense commercial pressures to formalize them. However, the susu members we met said they “refuse to be co-opted” into commercial banks and that the susu system is an important part of meeting everyday banking needs.

Susu is a participatory system, so these rules can be adjusted as needed by a collective decision of the members of the group. For small susu groups, meetings are held in comfortable spaces, such as a member’s home, and are accompanied by a meal or snacks at the host’s expense. Hosting is rotated among members to minimize, if not eliminate, the burden on one or a few members. Large susu groups may hold meetings at a neutral site, and the group shares the cost. Such groups may have agreed that a proportion of contributions will be kept for such “outings.” For instance, in the example noted above, the group may disburse the bulk of the money each month and save around 10 percent for “expenses.”

Some formal susu collectors have created a tangible location for clients to meet with them, made from metal shipping containers (see ). Routinely coming together in a familiar space to transact nonfinancial business facilitates the community-economies notion of surviving well together and supporting each other’s social life and well-being.

Sustainable Cooperation: Encountering Others and Surviving Well Together

Working together in a close-knit group involves encountering one another, and these encounters can be moments of joy and camaraderie but can also mean that tensions and disputes take hold. We emphasize the positive encountering of the women because this is what they pointed out to us in the interviews, but we also probed them about complicated issues when misunderstandings occur and how they use informal systems to resolve issues.

A few years ago, a documentary told the story of Andy Kranz (Citation2014), who visited susu groups in southern Ghana to show how the susu help ordinary people access funds through self-organizing. From our own investigations, we note that terms like “cooperation” and “helping” came up a lot. These concepts held among members create sustainable relationships that help members survive under conditions of austerity. All the members explained to us that being part of a susu creates “communal support,” helps in “bringing people together,” and allows for “self-help.” Members stated (40, n = 46) that self-help should not be viewed as something negative but as giving choices and voice to their own ideas on how to do business. Susu activity has become these women’s lives as they engage in conscious “social cooperation” to support each other. Social cooperation relates to conspicuous investments in activities that allow for “developing, refining, and intensifying cooperation itself” beyond work and family (Virno Citation2004, 62). In this regard, informants agreed with the following sentiments expressed by one of their number, who said that members of their susu group

come from different backgrounds—north, south, east, and west. We are good friends with each other; they come to my house and I visit their houses, too. If I need anything, I will call one of them first. I have no other family here in Kumasi, and they are my family. If it was not for them, where would I be? I have life challenges, yes. But they have made it a lot easier for me. We are family. My child and I know that we can go to them when we need help in anything. (“Akosua Tia” Kumasi, Trader, pers. comm., 24 March 2018)

Members we met with in Accra told us about the risk of defaulting members, though they were not concerned about those who default due to a funeral or personal reason, as other members will cover for those members. The issue of concern is when a member “cheats” or “absconds” with the group’s funds. We were told that this seldom happens, but, when it does, members will use their informal contacts to locate the person or their family members to reimburse the group. If this is not possible, then the group may ask the person who vouched for the member to pay for these losses. Members told us that, no matter the reason for a member’s defaulting, the group will come together to discuss ways to engage the person. All their decisions are based on consensus and consulting each other on how to get the best possible result.

While tensions do arise from time to time, encountering others is full of joy. For “Akosua,” Susu is a site of conviviality, facilitating her ability to interact with others outside of her normal social spheres. Susu provides an alternate family and the associated support for a decent livelihood. Members told us in the focus group that they keep track of each other’s life events and share milestones. All the Susu members (n = 46) we met with told us how they organize social events for each other—something they may not be able to afford on their own. They have developed strong bonds with each other, becoming each other’s keepers. Some of the members (34, n = 46) said they needed a female space because of the exclusions women feel when they do business. They share information freely with the intention of enhancing each other’s well-being. If a member encounters an opportunity she cannot exploit, she will call the most appropriate member and encourage her to pursue it instead. Perhaps this is the source of the strong basis for solidarity that underlies members’ focus on helping each other instead of seeking economic rents.

We learned that being in a susu is about commitment to oneself and community and that new members are recommended by a member in good standing. As one member, “Ama,” explained, “We also don’t just allow anyone to join our group. We make sure you’re someone who can live up to your word and fulfill all payments. But people still want to join our group because they see that it is working for us. I have told Lydia and her son about my group and they are thinking of joining us” (“Ama,” Makola Market, pers. comm., 6 July 2017). This suggests that a prospect is assessed based on presumed integrity and potential ability to meet membership obligations. Brought together by a common goal, members form a symbolic kinship that extends beyond familial relationships. The resulting ties may lead a group to come together in support of a member’s social obligations. This was the case with “Sahaada.” Her group comprised twelve members who paid GH₵5.00 (about US$1.10) daily, for a total of GH₵30.00 a week that goes to one person. “Sahaada” works as a kayaye, or head porter, helping people carry purchases in the market. Most of the people in her group and social circles migrated from northern Ghana and are self-employed laborers in the informal economy. They tend to be poor and have no direct family or friends in the south. For “Sahaada” and others in her line of work, joining a susu provides an alternate family, social support, and the collaboration they need to survive in an alien environment. Stronger ties are formed as members support each other in good and bad times.

“Maame Ataa,” another interviewee but from a wealthier group in Kumasi, observed, “I am like a big sister to all my susu group members. There are fifteen of us and I attend all their funerals and weddings. We support each other socially and in business. If I hear of an opportunity that is not in my line of business, I will tell one of my group members, and if we need money for her, we will make the necessary contribution” (“Maame Ataa,” Kumasi Central Market, pers. comm., 23 March 2018). This comment refers to collaboration and support beyond a susu and its members as individuals. Here, “Maame” passes relevant business information to other susu members who can take advantage of the opportunity. This type of collaboration can sometimes lead to business partnerships—for example, when members pool resources to pursue an idea that one person alone could not. The community purpose of susu allow them to serve the financial needs of the vulnerable in society. Participants rely on susu to cope with financial risks and to improve access to free credit. Susu members are often willing to help their symbolic kin for the well-being of the community. They prefer the susu system because of its informality and the strong ties it builds among members.

Even so, like the magajia (women leaders) described by Tufuor et al. (Citation2015), some members may be expected to take on certain risks that could become too burdensome, to the point of exhausting community cohesion. This is exacerbated by the blurred boundaries between obligations and voluntary support for each other in the culture. According to our informants, whatever susu are, they facilitate interaction among members of different backgrounds toward mutually beneficial ends. While susu have not eliminated social-economic class biases, they have built a formidable system for mobilizing financial and social capital for enacting decent livelihoods (Anuwa-Amarh Citation2015).

Apart from religious institutions, susu are one of the few contexts in which those who are better-off and the working class can be part of the same group, and members may come together based on community or work affinities. In some cases, members may pool funds because they are connected through working in a shop or at a market or attending a certain school. From this we learn that, while members value their susu group for its ability to help them mobilize financial resources, the most important driver seems to be the extra benefit of building community.

Members are driven more by their common solidarity than by profit. All our informants expressed a need to maintain and build friendships within their groups, noting that they call each other in times of trouble. As they conform to the dictates of contemporary life, they recognize the importance of a vibrant social intercourse for their well-being. By reproducing cultural dynamics that encourage concern for others, susu members demonstrate what Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy (Citation2013) describe as “commoning.” They struggle to negotiate access, use, benefit, and responsibility around a resource (funds and trust) in a manner that supports interactions and decent living for all in the community. The essence of this finding is in line with those of Basoah (Citation2010): the Susu system has established a good reputation for reliability by ensuring members’ well-being through cultural mechanisms that elicit good ethical and social behavior. Interacting and working together for their common good encourages effective survival outside of the predominant financial system.

In these observations we also find susu members creating a community economy based on ethical decisions to live well with themselves and others around them. Extending their support to people outside of their immediate kinship group and into the broader community, informants recognize the value of equal access to resources for personal and community well-being. Their desire to support the vulnerable socially and financially creates an equitable network of friends and relatives who survive beyond sustenance, also providing camaraderie. In this sense, susu practices enact community economy by mobilizing the disaggregated resources of individuals for the common good. Put together, the small amounts that individuals contribute to the pool become a sum large enough to support a community member’s livelihood project. With additional support—material and immaterial—each person can earn a decent living, thereby ensuring that the vulnerable can secure a decent livelihood. In essence, susu is about community and consistent support for the values of equity and inclusion. That is the spirit of a community economy.

Joys of Life: Managing Surpluses, Managing Commons

Community economy, as per Gibson-Graham and colleagues, requires both a wide distribution of surpluses beyond the household and also a concern for the commons. In the context of Ghana’s susu, these features are enacted through a community approach whereby familial relationships are not the basis for distributing the benefits of the group’s activities. “Maame Ataa’s” reference to attending weddings and funerals to commiserate with her susu members is a case in point. Despite the diverse socioeconomic status of members within susu groups, it is unusual to hear stories of theft and embezzlement in these schemes.

Group leaders in our focus group reported that they would expel a person for bad behavior and make sure they could not join any other susu group in the area. Likewise, our observations suggest that self-regulation, due in part to peer pressures, drives member action in the susu environment. A focus-group member mentioned that “peer pressure helps to ensure that members are timely with their deposits and other obligations to the group” (focus group, Makola market, Accra, pers. comm., 13 July 2017). In addition to the social pressure to conform to group rules, the concomitant reputational risks to one’s local identity discourage misconduct within these groups, encouraging all to be done in favor of the susu family.

This is explained by one informant who was interviewed in the Kumasi market:

How was it cooked that it seems poorly done?Footnote3 That you would hear that I have stolen money from my sisters. God forbid. Then what is the point of coming together to help each other? What am I going to tell my children? Can I ever go back to my village? They will all shun me. I could never live with myself. (“Araba,” Kumasi Market, pers. comm., 23 March 2018)

We asked about governance and managing a susu, and members (41, n = 46) explained that to ensure the sanctity of the susu structure, which is aimed at surviving well, cultural imperatives on “trust” and other moralities are blended with “corporate” due diligence to preempt corrupt characters from joining. The concept of trust is extremely important to members. It was detailed to us that susu members carry out a careful selection process to make sure the right members are included who understand membership policies and duties. Susu groups tend to identify likeminded people for membership and then encourage each other to support and drive the group’s—not the individuals’—objectives. These efforts preserve the values of the commons.

One consensus from our focus-group discussion was that, while a susu is “money business,” it also has strong social and charitable aspects that extend beyond individuals. Women in the focus groups spent a lot of time discussing the many ways their susu helps them, such as “paying school fees,” “buying inventory,” “getting advice on family matters,” and “expanding their networks.” We found that cordial relationships among susu members allowed poorer members to seek financial and other support from fellow members. This included credit purchases, wedding planning, and other nonfinancial activities, such as socializing on the weekend. Members explained to us that once they are “chosen” or “identified and recruited” as a susu member, they feel “pure joy.” They develop and maintain a sense of duty to become like a “family” in which they bring things to the group and the group cares about their well-being.

The dark side of the susu system lies in its core feature of being informal and self-regulating, without any formal structures to guard against corrupt practices. Granovetter (Citation1973) found that group systems have the problem of unequal solidarity among participants, which can undermine the trust needed for success. Members shared that some rogue susu collectors have been known to run away with deposits but that this happens rarely, due to social sanctions.

While commercial banks for the past three decades or more have sought to build links with this informal economy, they are not deeply connected to those who do not meet their formal policies. One former bank client turned (full-time) susu collector explained: “Banks are playing catch up because susus are about trust and the banks had failed to create opportunities to be seen as trustworthy” (anonymous female business owner, Osu Accra, pers. comm., 14 July 2017).

For this former banker, establishing a susu means “joining up people,” especially women, who are excluded from formal finance. It is about helping each other live decent lives. Perhaps unconsciously, susu participants support their commons through a rejection of the formal banking system and a concern for their colleagues. In this regard, we observed members' willingness to support each other’s personal development in diverse ways. All the informants we interviewed in Kumasi (n = 15) expressed disdain for formal commercial banks. They held the view that they “trusted” and “liked” the susu system more than formal banking.

While we have avoided romanticizing ROSCAs, we found a firmly held belief that because group members base their bank on consensus, they can trust it. While the members admitted that informal banks have the added pressure of not being private—as the women said, “Everybody knows your business”—one informant, “Akua,” nevertheless perceived formal banking as a mere money-making enterprise that was only interested in “her little money” and what it could sell her. “Akua” recalled: “When I was in need, they [the banks] will only look at my ability to pay without [thinking of] my survival or whether I was getting more into debt.” In her comment, “Akua” noted that the machine economy, which only seeks economic rents without caring for her personal well-being, is what turned her off of commercial banks.

Contrarily, susu groups offer caring and comradely relationships that tend to focus on savings and building one’s own wealth as opposed to spending money on products one does not need. We were also told that susu membership minimizes the social-class biases that pervade the formal banking system because most members share a similar class origin and feel comfortable with one another. The overwhelming majority of people interviewed (40, n = 46) said that values of giving and sharing are missing from the commercial banking sector.

Joining a susu is the starting point for many vulnerable women in Ghana to save money with families and friends (Aryeetey and Steel Citation1994). This is perhaps why the system is so prevalent among women. The impacts of susu practices extend into the broader community, with collectors receiving deposits from “strangers.” Members may invite these strangers to join their groups, and those invited often decide to join because of the perceived trustworthiness of the inviting party. Susu members are typically made up of women who choose to come together in a cooperative model of self-help to assist themselves and others.

Susu are not beholden to outside investors. The members consult each other and hold meetings to decide many of their needs. Common-family networks in Ghana extend well beyond the nuclear structure often found in European societies. The extended family includes kin and relatives derived from blood and marriage but also people close to the family. It is not uncommon for a family to “adopt” someone in need. Susu women have imprinted this idea of “family” on their susu, opening their doors to anyone with integrity—regardless of ethnicity, creed, or social status—to ensure that benefits that accrue from their activities extend to the broader community. For “Sahaada,” her susu family—a contrived family—was more real than her biological family. This is because the members bond through their collective pain and exclusion and their shared goal for human security.

“Regina,” a small business owner and a single mother, stated emphatically to the group that “susu is about paying [one]self. It’s the backup to life, and [I will] never forget that.” People revere and respect this tradition of saving and collecting money from each other. They see how it has helped them in business and socially. One member, “Kwaku,” reported that “susu is a cultural bank” that is second nature to Ghanaians: “Susu is genetic. [Points to his head.] The brain. [Susu is] culture and we know what it is, from the inside out. [People laugh and agree with him.] Though some susus are gone … and even when it ends … susu is still in me … you … us. Deep inside of all of us susu. This [feeling] never goes [away]” (“Kwaku,” focus group, pers. comm., 6 July 2017).

“Kwaku” is emphasizing that susu members emotionally bond with the system. The people interviewed, men and women alike, expressed that being part of a susu is a “way of life” that brings joy and that connects to the everyday things people do. People thus became protective and defensive in the face of complaints about a system that helps them. Members pushed back if we focused on the financial aspect, and they wanted us to record the personal connections and social interactions they experienced in their susu. They wanted us to know that while “formal banks are strangers” to customers, susu are social collectives invested in humans.

Women in susu groups acknowledged that members usually have the same or similar socioeconomic class origins; this is where their trust and loyalty reside. The women share a lived experience: they know each other’s struggles without any need for explanation. This is the very essence of community economies. Many people participating in a susu prefer the sense of community and the relationships—or as they put it, the “unity”—that they can create. “John,” one of a few male susu members who works in a market as a clothes seller, noted that “susu brings unity for me … for my sisters and for my brothers. I joined a susu long time for future goals and for emergencies that I have. We all do this” (“John,” Makola vendor, focus group, pers. comm., 6 July 2017).

Thus, susu participation creates avenues for social engagements and encourages attendance at social events outside of work where broader community issues are discussed informally. The susu system contributes significantly to people’s well-being, serving as a major activity that bridges the formal and informal sectors (Aryeetey and Steel Citation1994). While susu practices have a financial aspect, the people we interviewed wanted it to be known that susu is specifically a way to pool and share financial resources. Our informants viewed this concept of sharing and reciprocity as a “very African invention,” and one worth preserving for posterity. In this sense, susu practices are an embodiment of African culture that is at risk of extinction if they become commercialized. Members’ participation in their susu is thus more than a financial act; it is a battle of preserving and resisting against the potential erosion of a valued culture that people want to protect from the dominant market logics aiming to commercialize everything.

Interviewees such as “Sahaada” and “Maame Ataa” explained that the expectations of collaboration and support one finds among Ghanaian families have been transferred to susu groups (pers. comm., July 2017). They work together as women who know the struggles other women feel in the marketplace, at home, and in society and who can support each other. This work goes beyond any financial arrangement. As mentioned above, women imprint this idea of “family” onto their susu group, and it emerges through a sense of purpose and obligations to ensure the well-being of the group members.

Acknowledging African Origins in Community Economies

For centuries, the Ghana susu have been integrated into communal activities, so they are not obvious to the outside observer (Mati Citation2017; Kinyanjui Citation2019). Because these collectives are informal in nature, they are not given due recognition. Their existence outside of the formal economy makes the ancient practice of susu invisible so that it may seem less relevant in the lives of its members. Development scholar Mary Kinyanjui (Citation2014) found that market women in Kenya support each other through chamas, a kind of ROSCA, especially during times of hardship and struggle and various forms of abuse and alienation. Like susu participants in Ghana, Kenyan women make voluntary contributions to a collective for economic and social development, and they do all of this without formal accounting. It is this very informality that makes susu systems particularly useful to their members.

The susu system is a cooperative institution relegated to the sidelines because it is traditional. However, such co-op systems should be considered a part of the public- and cooperative-economics sector. Despite their long history of pooling money and goods for community benefit, susu have received little attention in terms of their origins in economic alternatives or as a development solution. This study corrects that mistake and cites susu practices as instrumental to knowledge making about community economies in West Africa, and specifically in Ghana’s cities.

Conclusions

Ghana’s susu are grounded in self-help and locally generated ideas of how to develop equitably. Generally, the understanding from our interviews and from surveying the literature is that susu are a postcapitalist, noncapitalist invention created by local people for whom coming together around group consensus is the most effective way to reach and include more people. Knowing this makes clear that the ancient susu system is very much part of the community economy, belonging to that subset of organizations that are invested in their members, ethical well-being, and cooperation. This focus on collectives in business and society is the essence of what makes a community economy.

The Ghana Susu: Community Economies Rooted in Ethical Well-Being

Susu are about how people choose to live sustainably, regardless of the direction of formal capitalism. The forty-six susu members we talked to in several cities in Ghana were clear that these collective, informal money systems are valued by the people who use them. Susu members told us repeatedly, in various ways, that the “susu can be a solution” to addressing development issues. Canadian feminist scholar Beverley Mullings (Citation2021) crisscrossed the Black world to show the different economies that African people have been making, how these economies respect human life, and how they have their own ways of embedding community into the economy. Reflecting on community-economy theory, we find that members support their livelihoods and build community solidarity through local innovations. For community-economy theory to be accountable, it should include locally based scholars, especially those coming out of the Global South. Thomas’s (Citation1974) theory of convergence explains that people should prioritize their own self sufficiency, that an economy focused on local needs does not become trapped in a dependency cycle, and that this kind of Black political-economic theorizing should inform the community-economies literature concerned about economic alternatives.

Locating Susu within the Theory of Community Economies

Commercialized neoliberalism imagines an economy in which entrepreneurs focus on individual pursuit of wealth and materialism (Harvey Citation2007). Whether by intention, accident, or ignorance (Goldsmith Citation1997; Dossa Citation2007), this extreme economic model propagates a unitary essence of development that can only be achieved by adopting a White historical process of socioeconomic cultural change grounded in individuality and related ideals. This economy is constituted as a self-regulating system, energized by the motivation to better one’s own condition at the expense of others’ well-being. The mindset of this economy leads to converting self-sustaining economies into environmentally devastating systems predicated on the assumption that the world has infinite resources. Clearly, such an economy is not sustainable and should be pared down to one that is accountable to people.

This study shows that there is no natural inclination for humans to trade for only the profit motive, and to organize societies around the practice of economic exchange is about human interactions. Elinor Ostrom (Citation1990) likewise showed in her set of design principles that were uncovered from empirical work that there is in fact a logic to cooperating—and communing—for people’s very survival. Feminist economic geographers J. K. Gibson-Graham (Citation1996) have argued that the study of economics has been so obsessed with forms of capitalism that it has overlooked the diversity of economic forms occurring in the world. They also responded to European male Marxists who were so caught up in commercial capitalism and formal production that they missed local community happenings that feminists, and especially postcolonial feminists, had seen occurring in the world.

The idea of community economies goes beyond European Marxist critiques: it is feminist and postcapitalist. Postcapitalist, a term used in much of J. K. Gibson-Graham’s work, refers to the local economic alternatives that are taking place despite the widespread emphasis on the commercial firm. Postcapitalist defines organizations like the susu as systems that are neither socialist nor capitalist. The commoning and sharing of goods by citizens would also fall into the realm of postcapitalism. “Susu mamas,” the women who run their ROSCA groups, facilitate sharing and commoning and manage unregulated financial systems that provide people with quick access to savings and credit.

Even though many susu members we interviewed said they were excluded from formal banks, susu allow for a people-focused banking method where members get support and can manage their own business through self-regulation, because it is based almost entirely on personal relationships and trust. While susu present a way for people to meet their economic-livelihood needs, we learned that they also provide a sense of belonging and bonding (Bouman Citation1995; Ardener and Burman Citation1996; Kranz Citation2014; Mondesir Citation2021). In this way, they encourage community building, societal well-being, and a sense of reciprocity in which people care for themselves and their community.

Susu practice is the epitome of a community economy. Susu fit with Gibson-Graham’s (Citation1996, Citation2006), Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy’s (Citation2013), and Gibson-Graham and Dombroski’s (Citation2020) diverse-economies theory, as they quietly challenge the dominant viewpoint of a unitary capitalist global system. That the foundational basis for capitalism is not uniform around the world suggests that differentiated and even wholly alternative systems exist and have existed for a very long time. Capitalism strengthens its dominance through the weakening of its competition and by appearing as the only possible model for society. Yet most of the Susu Mamas we interviewed in this study (39, n = 46) admitted that they refuse to conform to commercial businesses; rather, they are making space for new economies—for plural economies—to take shape.

Citing the Susu System

Acknowledging susu origins in cooperativism and community economies is a starting point. Susu co-op systems continue to fly in the face of the corporatization of the economy at a time when people are saying (as they have been for a long time) that they should lead their own development (Cheru Citation2016). Susu, rooted in community economies, are antithetical to the aggressive pursuit of economic rents and the growth thesis. Their need to collectively organize outside of the formal global system of finance gives susu their alternative status. As “mindful consumers” (Sheth, Sethia, and Srinivas Citation2011), susu and their simple ways of mobilizing capital are permeated with thoughtful concern for solidarity within their communities.

Gibson-Graham’s (Citation1996, Citation2008) community-economies theory has opened up what we can know about varied economic systems, beyond the polarizing debates between the Left and the Right. The ethical principles for assessing susu systems as part of the community economy are clear. It also becomes clear that, while community-economies theory opens an understanding of people-led economies, it does fall short in terms of representation. Bledsoe, McCreary, and Wright (Citation2019) argue that the community-economies framework misses the point of how race underlies why people create economic alternatives. Hossein and Christabell’s (Citation2022) edited volume, Community Economies in the Global South, fills in the gap in community-economies literature by tying it to local scholarship. It is meant to acknowledge not only race-based discrimination but the myriad interlocking oppressions of gender and class and the caste-based exclusions of people in the Global South. Focused on susu, the study underlines African peoples’ long history of solidarity economies that the wider literature has failed to include.

Geographer Mary Njeri Kinyanjui’s (Citation2014, Citation2019) work explores the representation of Kenyan people and what it means for them to build what is missing in associational life through the informal banks called chamas (see also Moyo Citation2011; Hossein Citation2018). Ghanaian scholar Kwaku Asante-Darko (Citation2013), in his study on self-help and giving circles, dates this historical effort to precolonial days among the Asante people. Susu members make voluntary contributions because they want to be part of the local economic- and social-development systems. They do this added work without any compensation while reducing formal accounting and still ensuring accountability.

That susu practices have survived through the centuries indicates an indigenous acuity that serves participants well. The system has low transaction costs and answers the fundamental needs of the community in a way that is absent in the neocapitalist leanings of the formal financial sector. Susu have existed outside the market system since their origins in Africa, and to this day they remain informal and cooperative. Susu have thereby facilitated economic mobility for many who would otherwise be destitute. Aryeetey (Citation1998) notes the rudimentary nature of capital markets and weaknesses in financial intermediation in general. The overall low level of domestic savings is a primary source of frustration for private-sector players seeking local funding. Market vendors, mostly women, use susu to get around financial challenges (Aryeetey and Gockel Citation1991). These women use their susu groups—people with similar class backgrounds—to “unite” and solidify their aspirations.

Susu practices have continued over long periods because the susu system focuses on social welfare, insurance, governance, voice, and activism. The chief susu leaders, also known as susu mamas, have directed susu practices down a path to where people’s economic practices are rooted in joy, belonging, and solidarity. The community-economies literature would be enhanced by including this fact about how some people engage with market economies.

As people have moved around the world, they have taken these African-rooted ideals with them, thereby facilitating the global spread of community-driven economies. Ghanaian development scholar Franklin Obeng-Odoom (Citation2013) has put forth a body of work that eschews neoliberal top-down thinking for locally grounded ways in which people can contribute to development. Susu systems are a major contribution to world economies, led by ordinary people.

The recent documentary The Banker Ladies features Black immigrant women from Somalia, Trinidad, and Sierra Leone now living in Toronto, Canada. The film shows how collective financial systems have addressed business exclusion in the West, yet the use of susu systems goes unnoticed (Mondesir Citation2021; Hossein Citationforthcoming). These women from various parts of Africa, known as the Banker Ladies, rely on social support and pooling of funds through collectivity to meet their livelihood goals. Susu members in Ghana and elsewhere have figured out that collective banking and knowing how to help people in need do not require external expertise.

For centuries, susu practices have perfected their local forms in the face of globalization, underlining a preference for cooperatives and collective well-being. The susu tradition has been handed down to preserve gifting to each other and to push against the dominant market logic of making a profit on everything. As a local Ghanaian saying goes, Yewo adze oye (We have a lot of good things). Susu practices are good things for those who use them. The fact that susu exist despite the capitalist machine is testament to the strength of indigenous roots in mutual aid and community giving. Future research may investigate the transnational influence that susu banking has had on Black diasporas.

The people of Ghana choose susu for their social aspects and to remake economies, and there is still much to learn about these cooperative economies. This study has touched on a small part of what can be explored about susu systems in Africa and among the Black diaspora. Notably, the vast majority of susu participants are women, while the managers and the collectors are men, indicating a certain gender bias in susu operations. This gender imbalance and its implications for African business need further inquiry. Perhaps we should start considering the aspects of business development that draw on nonpecuniary resources and benefits to participants. Harnessing susu processes more effectively within their unique indigenous milieu could enhance business growth for many and create employment in Ghana and other parts of Africa.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the susu members who made time to speak to us. The staff people at the Ghana Cooperative and the Susu Association helped arrange interviews in Cape Coast. Our greatest thanks go to our research assistant Kumiwaa Asante, who assisted with focus groups and interviews in Accra and Tema. This project was funded in part by the Insight Development Grant of the Social Science and Humanities Research Council and the Canada Research Chair program. We dedicate this essay to the late Adwoa Pokuah, a susu mama who for fifty years made it her life’s work to promote susu as a valued form of social economics. We are grateful for the support given to us by Maliha Safri and Boone Shear and their team.

Notes

1 The Diverse Economies Iceberg by Community Economies Collective is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. See https://www.communityeconomies.org/resources/diverse-economies-iceberg9.

2 The authors note here that the informal ROSCA system is much bigger but this number is not known.

3 This is a literal translation of a rhetorical proverbial question that references why a person should allow oneself to be caught in an abomination.

References

- Ansaful, I. 2019. “Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Ghana.” M.A. thesis, KNUST School of Business.

- Anuwa-Amarh, E. T. 2015. Understanding the Urban Informal Economy in Ghana: A Survey Report. Accra, Ghana: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Ardener, S. 1964. “The Comparative Study of Rotating Credit Associations.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 94 (2): 201–29.

- Ardener, S., and S. Burman, eds. 1996. Money-Go-Rounds: The Importance of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations for Women. Oxford, UK: BERG.

- Aryeetey, E. 1998. Financial Integration and Development. London: Routledge.

- Aryeetey, E., and F. Gockel. 1991. “Mobilizing Domestic Resources for Capital Formation in Ghana: The Role of Informal Financial Markets.” AERC Research Paper no. 3, Nairobi, Kenya, August 1991.

- Aryeetey, E., and W. Steel. 1994. “Informal Savings Collectors in Ghana: Can They Intermediate?” Finance and Development 31 (1): 36–7.

- Asante-Darko, K. 2013. “Traditional Philanthropy in Pre-colonial Asante.” In Giving to Help, Helping to Give: The Context and Politics of African Philanthropy, ed. T. A. Aina and B. Moyo, 83–104. Dakar, Senegal: Amalion and TrustAfrica.

- Mondesir, E., dir. 2021. The Banker Ladies. Prod. Diverse Solidarities Economies Collective. Films for Action. 22 min. https://www.filmsforaction.org/watch/the-banker-ladies.

- Basoah, A. K. 2010. “An Assessment of the Effects of ‘Susu’ Scheme on the Economic Empowerment of Market Women in Kumasi, Ghana.” Master’s Thesis, KNUST Department of Planning.

- Basu, K. 2011. “Hyperbolic Discounting and the Sustainability of Rotational Savings Arrangements.” American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 3 (4): 143–71.

- Bauman, Z. 1993. “Postmodernity; or, Living with Ambivalence.” In A Postmodern Reader, ed. J. Natoli and L. Hutcheon, 9–24. Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press.

- Belk, R. W. 2010. “Sharing.” Journal of Consumer Research 36 (5): 715–34.

- Belk, R. W. 2014. “Sharing Versus Pseudo-Sharing in Web 2.0.” Anthropologist 18 (1): 7–23.

- Bledsoe, A., T. McCreary, and W. Wright. 2019. “Theorizing Diverse Economies in the Context of Racial Capitalism.” Geoforum 132 (July): 281–90.

- Bonsu, S. K. 2019. “Development by Markets: An Essay on the Continuities of Colonial Development and Racism in Africa.” In Race in the Marketplace: Crossing Critical Boundaries, ed. G. D. Johnson, K. D. Thomas, A. K. Harrison, and S. G. Grier, 259–72. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bouman, F. J. A. 1977. “Indigenous Savings and Credit Societies in the Third World: A Message.” Savings and Development 1 (4): 181–219.

- Bouman, F. J. A. 1995. “Rotating and Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations: A Development Perspective.” World Development 23 (3): 371–84.

- Cheru, F. 2016. “Developing Countries and the Right to Development: A Retrospective and Prospective African View.” Third World Quarterly 37 (7): 1268–83.

- Cox, O. C. 1948. Race, Caste and Class. New York: Monthly Review.

- Cox, O. C. 1964. Capitalism as A System. New York: Monthly Review.

- Dossa, S. 2007. “Slicing Up ‘Development’: Colonialism, Political Theory, Ethics.” Third World Quarterly 28 (5): 887–99.

- Escobar, A. 2020. Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

- Firat, A. F., and A. Venkatesh. 1995. “Liberatory Postmodernism and the Reenchantment of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 22 (3): 239–67.

- Geertz, C. 1962. “The Rotating Credit Association: A Middle Rung in Development.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 10 (3): 241–63.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 1996. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2008. “Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for Other Worlds.” Progress in Human Geography 32 (5): 613–32.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., J. Cameron, and S. Healy. 2013. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., and K. Dombroski. 2020. The Handbook of Diverse Economies. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Glynn, M. A. 2019. “The Mission of Community and the Promise of Collective Action.” Academy of Management Review 44 (2): 244–53.

- Goldsmith, E. 1997. “Development as Colonialism.” Ecologist 27 (2): 69–76.

- Granovetter, M. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–80.

- Harvey, D. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hossein, C. S. 2018. The Black Social Economy: Exploring Diverse Community-Based Markets. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hossein, C. S. Forthcoming. The Banker Ladies. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Hossein, C. S., and P. J. Christabell. 2022. Community Economies in the Global South. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kedir, A. M., and G. Ibrahim. 2011. “ROSCAs in Urban Ethiopia: Are the Characteristics of the Institutions More Important than Those of Members?” Journal of Development Studies 47 (7): 998–1016.

- Kinyanjui, M. N. 2014. Women and the Informal Economy in Urban Africa: From the Margins to the Centre. London: Zed.

- Kinyanjui, M. N. 2019. African Markets and the Utu-ubuntu Business Model: A Perspective on Economic Informality in Nairobi. Cape Town, South Africa: African Minds Publishers.

- Koto, P. S. 2015. “An Empirical Analysis of the Informal Sector in Ghana.” Journal of Developing Areas 49 (2): 93–108.

- Kranz, A. 2014. “Susu Is Good for You!” YouTube video, 1 July, 41:06. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7I3Myk69JMY.

- Lloveras, J., G. Warnaby, and L. Quinn. 2019. “Mutualism as Market Practice: An Examination of Market Performativity in the Context of Anarchism and Its Implications for Post-capitalist Politics.” Marketing Theory 20 (3): 1–21.

- Mati, J. M. 2017. “Philanthropy in Contemporary Africa: A Review.” Voluntaristics Review 1 (6): 1–99.

- Moyo, B. 2011. “Transformative Innovations in African Philanthropy.” Bellagio Initiative commissioned paper, November 2011. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/3718/Bellagio-Moyo.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Mullings, B. 2021. “Caliban, Social Reproduction and Our Future Yet to Come.” Geoforum 118 (January): 150–8.

- Njie, H. 2022. “Community Building and Ubuntu: Using Osusu in the Kangbeng-Kafoo Women’s Group in The Gambia.” In Community Economies in the Global South, ed. C. S. Hossein and P. J. Christabell, 125–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nyerere, J. K. 1968. Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2013. Governance for Pro-poor Urban Development: Lessons from Ghana. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sato, C., and T. Tufour. 2020. “Migrant Women’s Labour: Sustaining Livelihoods through Diverse Economic Practices in Accra, Ghana.” In The Handbook of Diverse Economies, ed. J. K. Gibson-Graham and K. Dombroski, 186–93. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Sheth, J. N, N. K. Sethia, and S. Srinivas. 2011. “Mindful Consumption: A Customer-Centric Approach to Sustainability.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, no. 39: 21–39.

- Shiva, V. 2020. Reclaiming the Commons: Biodiversity, Indigenous Knowledge, and the Rights of Mother Earth. London: Synergetic.

- Thomas, C. Y. 1974. Dependency and Transformation: The Economics of the Transition to Socialism. New York: Monthly Review.

- Thomas, C. Y. 1988. The Poor and the Powerless: Economic Policy and Change in the Caribbean. New York: Monthly Review.

- Tufuor, T., A. Niehof, C. Sato, and H. van der Horst. 2015. “Extending the Moral Economy Beyond Households: Gendered Livelihood Strategies of Single Migrant Women in Accra, Ghana.” Women’s Studies International Forum, no. 50: 20–9.

- Virno, P. 2004. A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life. Trans. I. Bertoletti, J. Cascaito, and A. Casso. New York: Semiotext(e).

- Wilson, K. 2015. “Towards a Radical Re-Appropriation: Gender, Development and Neoliberal Feminism.” Development and Change 46 (4): 803–32.