Abstract

The essay presents an exploratory study of the equub, a form of community-based finance that is well-established in the Ethiopian diaspora in Germany. Equubs render visible the financial expertise developed in the majority world and its circulation in diasporic space. As such, equubs exemplify the power of People of African Descent in Germany to organize against financial exclusion. The essay draws on the theory of diverse economies and its method of reading for difference to analyze the characteristics of the equub as a nonmarket financial institution, showing its praxis of building community economies and its linkages to the diverse economy at large. Processes of decommodification, collective governance, and ethical decision making around financial needs politicize finance, making the equub an interesting case of a postcapitalist-finance imaginary.

The Afrozensus, which is the first comprehensive survey of People of African Descent in Germany, has revealed the ubiquity of anti-Black racism in all areas of everyday life (Aikins et al. Citation2021). Embedded in the tradition of Black scholarship and community organizing in Germany, the Afrozensus provides detailed evidence of discrimination in many fields, including finance and insurance, where almost half of the survey respondents (47 percent) reported having experienced discrimination (Aikins et al. Citation2021, 101–3, fig. 27). This raises the question as to what “quiet forms of resistance” and strategies of mutual aid People of African Descent in Germany may have developed in the face of widespread financial exclusion (Hossein Citation2016).

This essay thus presents findings from an exploratory case study on the equub,Footnote1 a form of community-based finance that is well-established in the Ethiopian diaspora in Germany. Equubs form part of a long tradition of knowledge on alternative finance, produced and circulated by scholars and communities in Ethiopia, the diaspora, and across the majority world more broadly (Aredo Citation2004; Hossein and Christabell Citation2022; Ardener Citation1995). The academic literature typically discusses equubs under the umbrella term of ROSCAs (rotating savings and credit associations),Footnote2 defined as an “association formed upon a core of participants who agree to make regular contributions to a fund which is given, in whole or in part, to each contributor in rotation” (Ardener Citation1964, 201).

Reading the Equub for Difference

A review of the vast literature on ROSCAs shows, however, that “any generalization about rotating savings and credit associations should be interpreted with caution. ROSCAs vary immensely from country to country and from group to group or from place to place even within a country” (Aredo Citation2004, 182). In what follows, we expand on this premise of ROSCA diversity to discuss the location of equubs within an economic landscape that is recognized as inherently diverse. Our analysis is theoretically informed by the praxis of reading for difference, which serves diverse economies scholars as “a thinking practice, a research method and an intervention in making worlds” (Gibson-Graham Citation2020, 483). Reading for difference formulates a critique of capitalocentric discourses, which limit their field of vision to the sphere of the capitalist market economy. It allows for a theoretically rich conceptualization that (1) redefines the boundaries of the economic realm; (2) recognizes the existence of a multiplicity of economic logics, practices, institutions, and identities; (3) articulates a language of economic diversity; and (4) explores relations of economic interdependence and possibilities for enacting transformative change. Such a theoretical praxis politicizes the economic discourse and opens a space for exploring community economies (Gibson-Graham Citation1996).

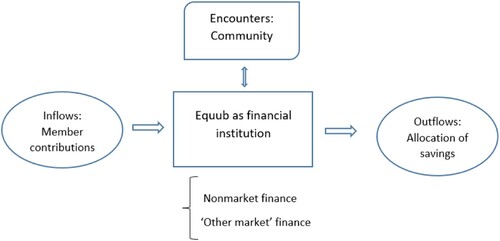

The essay first provides a nuanced reading for difference that maps the theoretical location of equubs within the diverse-economy framework and that assesses their potency in terms of postcapitalist imaginaries of community economies. We begin by analyzing the characteristics of equubs as alternative financial institutions in which a collective governance structure decommodifies and socially embeds financial relations among participants. We distinguish this prefigurative form of finance from other variants of ROSCA in which the mechanism of peer-based financial intermediation is delimited by internal money markets.

Next, we explore how equub participants build community economies, cultivating relations based on values such as trust, reciprocity, solidarity, and belonging. We look at the social and ethical coordinates that inform processes of collective decision making in the face of potentially divergent financial needs and expectations. In this regard, we believe that equubs can provide important insights into thinking about postcapitalist politics of finance in terms of the “ethical and political space of decision in which negotiations over interdependence take place,” thus critically reflecting on how the values underpinning such deliberations shape imaginaries of collective becoming (Gibson-Graham Citation2006, 192).

Finally, we turn our attention to the interrelations between equubs and the diverse economy at large, which oftentimes remain underexplored in the literature. We argue that ethical concerns around finance cannot be limited to the mode of financial intermediation in the narrow sense but must extend to critical questions concerning the interdependencies between both the financial and nonfinancial realms. As sketched out in , we are interested in developing a critical understanding of both the income streams that sustain equubs (inflows) and the ends to which savings generated within equubs (outflows) are used. The savings generated within an equub can sustain a “contingent assemblage of economic processes, practices, and actors” (Community Economies Collective Citation2019, 57). At the same time, equubs are sustained through myriad income streams connected to participants’ livelihood strategies. In this context, reading for difference implies carefully scrutinizing the potential of equubs to foster postcapitalist practices in a broader context.

Methodology

The study is based on seven semistructured interviews conducted by Michael Emru Tadesse in Berlin in the period of October–December 2019.Footnote3 The selection of equubs and interview partners was based on convenience sampling. The interview structure was informed by Ardener’s (Citation1964, 223–6) field guide for the study of ROSCAs. The interviews were conducted in Amharic, were tape-recorded, and then were manually transcribed and translated into English. Principles of research ethics such as informed consent, voluntary participation, anonymity, and privacy have been observed.

The Ethiopian Diaspora in Germany

The Ethiopian diaspora in Germany constitutes a small but vibrant community of approximately 30,000 persons, roughly corresponding to 3 percent of People of African Descent in Germany.Footnote4 Compared to top-destination countries such as the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Israel, the Ethiopian community in Germany is relatively small.Footnote5 Periods of political and economic instability have meant that “migration from Ethiopia has primarily, though not exclusively, been conflict-induced,” although there is also a long tradition of academic mobility to (West and East) Germany (Warnecke Citation2015, 11).

Studies show a proliferation of Ethiopian civil-society initiatives across Germany, including social, cultural, and political organizations, faith-based institutions, sports clubs, youth organizations, academic and professional networks, development-cooperation projects, and digital platforms (Warnecke Citation2015; Mekonnen and Lohnert Citation2018; Schlenzka Citation2009).

Given this civic dynamism, it is not surprising that the Ethiopian diaspora has developed its own community-based institutions of finance as well. Our interview data shows that while the formal banking system is used for financial transactions with institutional actors such as the state and employers, the Ethiopian community in Germany turns to equubs for saving and borrowing money. Equubs are valued as socially embedded financial instruments that support members in achieving their personal savings goals and that nurture values such as mutual aid and community belonging. Banks, in contrast, are perceived as impersonal, inflexible, and bureaucratic. Central points of critique include their profit orientation, the high cost of borrowing, and the difficulty of accessing loans in the face of anti-Black racism (Aikins et al. Citation2021, 101–5).

In building more equitable relations of finance in the here and now, the Ethiopian diaspora in Germany draws on the extensive knowledge of equubs developed in Ethiopia over the centuries. The interview data shows that the diasporic community is highly aware of the significance of equubs in Ethiopia and is proud of continuing this tradition in Germany. This shows that, in the process of migration, collective and experiential economic knowledge originating in the majority world travels across borders, creating novel economic spaces where this knowledge is practiced, shared, and adapted according to the needs of the diasporic community.

Locating Equubs within the Diversity of Finance

We start our exercise in reading for difference by examining the characteristics of equubs as financial institutions. As Safri and Madra (Citation2020, 338) point out, “A diverse economies approach to finance is: to not presume one type, but to actually investigate the diversity of financial forms and intermediations that currently exist.” Building on the work of diverse-economies scholars, we broadly distinguish between three categories of financial intermediation: (1) for-profit market-based finance; (2) “other-market” finance, with social, political, or cultural parameters significantly impacting financial-market institutions; and (3) nonmarket forms of finance (Gibson-Graham and Dombroski Citation2020, 15–17).Footnote6

Based on this categorization, we argue that ROSCAs fall into two categories: nonmarket or “other market.” While our focus lies on the specific characteristics of equubs as nonmarket financial institutions, we end this section with a brief discussion of why ROSCAs that feature internal money markets should be categorized as other-market finance.

Equubs as Nonmarket Financial Institutions

As a peer-based savings mechanism, the equub constitutes a decommodified space that replaces market transactions, including interest payments. For example, Equub B in Berlin consists of six members, each of whom makes a monthly contribution of €250. Members take turns to receive the collective fund of €1,500 (6 × €250) each month. The equub cycle ends after six months, when each member has received the fund once. Members then decide whether or not to start a new cycle. As this example illustrates, an equub simultaneously functions as a savings club while facilitating access to credit. Those members who receive funds early on in effect take out a loan from the equub, which they then pay back through their monthly contributions. In practice, the number of funds and members in different equubs is rarely identical. All the studied equubs in Germany allow contributions both to a single fund by two or more people (which increases the number of members) and also to more than one fund by a single person (which increases the number of funds).

The Structure of Self-Governance. ROSCAs are “mutual aid financing groups in which members pool and share money according to an agreed upon protocol” (Hossein Citation2020, 354). While such protocols do not always take the form of a written document, they incorporate a complex set of well-defined rules that are collectively recognized and followed by all members. Such rules typically concern the size and composition of the membership, the collective savings goals, the roles and responsibilities of members, the coordination process, and conflict resolution (Aredo Citation2004, 184). As Begashaw (Citation1978, 254–5) observes, “There are many variants of the Ikub in Ethiopia, each with its own rules and regulations governing the operation of the association.” This autonomy in collective self-governance provides equubs with a high degree of flexibility to define their own praxis, thus making it an accessible savings scheme across different income groups.

The membership may be established as a closed group for the duration of the equub cycle. Alternatively, members may choose to allow newcomers to join on an ongoing basis. In Berlin, we encountered both fixed and flexible membership models, but the fixed group tended to be preferred. Our interviewees pointed out that equubs in Germany tend to be smaller than those in Ethiopia and primarily use verbal agreements.Footnote7 In our sample, we found that only the equub with the highest level of contributions (€1,000 per month) had agreed on a set of written by-laws:

We have written rules, but they are few and uncomplicated. The first rule is that contributions should be made within two weeks of the new month. The deadline is, therefore, the fifteenth day of each month. We calculate the time according to the Ethiopian calendar. The second rule is that if a person does not pay in time, she will be punished €5. The third one is that contributions should be made on Sunday. The fourth rule is about giving priority to a member in need. (Equub G)

Allocation of the Equub Fund. As Begashaw (Citation1978, 254) notes, the “essential principle involved … is rotating access to a continually reconstituted fund.” Hence, members must decide on the order in which the fund will be allocated. In the literature, we find systems of allocation based on lottery, need or seniority. Fairness may also dictate that “the last recipient in the past cycle become the first recipient in the next one” (Bouman Citation1995, 379). If a member wishes to drop out before the end of the cycle, they will be required to wait until the end of the cycle to receive their savings.

In the “random ROSCA,” which is quite common both in Ethiopia and in Germany, the group “allocates its pool of funds based on random drawing of lots, with the winning member receiving the pool” (Kedir and Ibrahim Citation2011, 1001; Besley, Coate, and Loury Citation1993). A one-off drawing of lots means the order of receiving the fund is set for the duration of the cycle. This allows for stable financial planning among members and has the additional advantage of reducing the coordination and documentation effort. A monthly drawing of lots, on the other hand, gives those members who have not yet received the fund a recurrent chance of being the next lucky recipient. In Equub C in Berlin, “The drawing is held every month, on Saturday … At least three people attend the drawing, and anybody can pick the receiver from the pot. One of them is the sebsabi [coordinator] of the equub and the other two are the oldest members of the equub. Since these people are the oldest, they are reliable; you respect them.”

Sebsabi: The Coordinator. The structure of self-governance is aided by a sebsabi—that is, a volunteer coordinator who is elected (or endorsed) from within the equub membership. The sebsabi needs to be a well-respected, trustworthy member of the community. Their responsibilities include the collection and distribution of the funds, facilitating communication within the equub, keeping track of records and the order of rotation, and acting as a liaison for members’ queries and concerns:

There is a big demand for equub, and equub needs a responsible person as a sebsabi. But it is difficult to find a responsible and willing person for this position. In some cases, people cannot establish an equub even if they have a strong desire to do so and have enough [potential] members. This is because they cannot find a person among themselves who can be a sebsabi. Even if they have one, the person may not be willing to do it because it is a lot of work without compensation. Therefore, it may be easier to join an existing equub. (Equub A)

In the Berlin equubs studied, the majority of sebsabis were women, which shows that equubs help empower women to exercise economic leadership positions, albeit without adequate reimbursement.Footnote8

Risk Management. As informal institutions, ROSCAs have developed their own mechanisms to safeguard their financial stability. As Ardener (Citation1995, 4) remarks, “It is in the interest of most or all of the members to ensure that there are no defaulters. A defaulter threatens the system, and a failed ROSCA can damage the reputation of an entire group.” In Ethiopia, members may be required to provide guarantors, present collateral, or sign a check when receiving the fund. Members who delay the payment of contributions after having received the fund may face especially high fines: “This harsher punishment is intended to convey the message that, since they are enjoying other people’s money free of interest, they are under a higher moral responsibility to make payments on time” (Yimer et al. Citation2018, 102). Although our respondents were well aware of these practices, none of the Berlin equubs requested such securities, relying on internal mechanisms of social sanctioning instead.

Finally, it should be noted that equubs in Ethiopia have a much stronger legal standing compared to their counterparts in the diaspora. In Ethiopia, courts “consider internal rules of Eqqubs as binding and enforceable in court of law and they rely on Eqqub records and membership cards to make their decisions” (Yimer et al. Citation2018, 108).Footnote9 In Berlin, in contrast, equubs rely on internal mediation mechanisms, as they do not think it would be feasible to resort to formal courts in the case of conflicts.

Excursus: ROSCAs as Other-Market Finance

The equubs we studied in Berlin were strictly nonmarket financial institutions. Our interviewees were cognizant of the existence of other equub constellations in Ethiopia but expressed ethical objections to introducing elements of market exchange in a socially embedded, nonmarket setting. Indeed, a cursory survey of the literature on ROSCAs reveals that, from a diverse-economies perspective, it would be more accurate to categorize those varieties of ROSCA that do not fully decommodify financial transactions as other-market (rather than nonmarket) finance. Next, we will highlight three constellations prominently discussed in the international literature: the regulated sale of the fund, auction ROSCAs, and accumulating money pools (ASCRAs).

First are those ROSCAs that allow for the sale of the fund, with the coordinator acting as a mediator. In southern Ethiopia, the allocation of the fund is decided by lottery, followed by the winner’s opportunity to sell their right to the fund to another member (Aredo Citation2004, 185). In big ROSCAs in the Tigray region, “Most members are eager to get paid first and do not want to wait until they draw the winning lot. For this reason, they want to buy the lot from someone who won the lot” (Yimer et al. Citation2018, 104). Since this arrangement only came about recently, however, “There are not established customary laws that regulate how to prioritize among members who are willing to buy a ROSCA lot, and the internal rules do not regulate it. This leaves a regulatory gap” (105). The fund thus becomes a commodity that is internally traded under semiregulated conditions. This also affects the collective structure of governance. The lack of transparency and participatory decision making concerning the sale of the fund has led to “mistrust and complaints” as well as concerns around the membership composition, as this may “attract more members who are lured by the potential return they may get by selling their Eqqub lot” (105).

Second is the “bidding ROSCA” (Besley, Coate, and Loury Citation1993), which has a long tradition in Asian countries and requires members to “bid competitively for the pool which is allocated to the highest bidder” (Kedir and Ibrahim Citation2011, 1001), thus creating a fully-fledged internal market mechanism for allocating the fund in each round. As Bouman (Citation1995, 379) underlines, “The auction is a method of gaining influence over the order of rotation. Members with a special interest in immediate access to the fund, and willing to pay for the privilege, compete with each other through bidding.” The group may share the extra revenue generated through the bidding process or they may use it as finance capital to start an additional pool “from which to make loans against interest” (380).

A third form is the accumulating savings and credit association (ASCRA), defined as large organizations that “also pool savings, but … the savings are not instantly redistributed but allowed to accumulate, to make loans” during the cycle (Bouman Citation1995, 375). People tend to join ASCRAs with the aim to save for large expenses related to education, social and religious ceremonies, or life-cycle events. Loan requests by members are decided by a committee according to agreed-upon principles, with financial emergencies being given priority. ASCRAs charge high interest rates, which allows the group to “build up funds, increasing lending capacity but also boosting the value of a share in the fund” (375). The accumulating pool in effect serves as finance capital for the internal credit market, which increases liquidity and generates interest revenue for members.Footnote10

Encounters: Community Building in Equubs

Besides the institutional analysis, a second aspect of reading for difference is to explore how different forms of finance may be “guided by very different norms, constituted by different communities, and assuming different forms of functioning” (Safri and Madra Citation2020, 338). In this section, we analyze the myriad ways in which equub participants encounter each other as economic subjects, and we explore the social and ethical underpinnings guiding members’ interactions. We argue that equubs provide a resilient framework in which people may cultivate peer-based long-term financial relationships grounded in the principles of trust, reciprocity, solidarity, and conviviality (Hossein and Christabell Citation2022). Equubs politicize finance by building community economies in which economic subjects can address their needs and pursue their goals together in ongoing processes of collective becoming. As such, they deliver important insights into thinking about postcapitalist imaginaries of finance.

Diverse Constellations of Community

As Hossein (Citation2020, 359) observes, ROSCAs’ “staying power has to do with people who have conscientiously chosen to interact in cooperative ways.” As self-organized financial groups, equubs develop their own unique strategies of community building, with the composition of the membership being shaped by social, cultural, economic, and ethical considerations. While immigrant community networks are key to participation in diasporic equubs, membership criteria may also include “sex, age, kinship, ethnic affiliation, locality, occupation, status, religion, and education” (Ardener Citation1964, 210). In Berlin, equubs tend toward diversity in terms of gender, religion, and ethnicity, bringing together individuals from various ethnic groups within Ethiopia and occasionally including immigrants from countries such as Eritrea, Sudan, Somalia, Egypt, and Bangladesh. One respondent recalled how, on the occasion of a childbirth, members of the Ethiopian Christian Orthodox Church decided to found a women-only equub: it “was established when we went to visit a new mother. Those of us who were there decided to establish an association to stay together, and we said, let this association be equub” (Equub G).

Access to an equub community is further regulated through a rigorous process of screening potential new members. This mechanism is critical to safeguarding the financial resilience of an equub and serves “to verify if their future members have good social reputation, good behavior and established social, economic, and religious ties that make it less probable for those people to default on their commitments, and if they still do so for whatever reason, that there will be a possibility to create social and economic pressure on them to fulfill their obligations” (Yimer et al. Citation2018, 106). This screening process can result in a tendency toward socioeconomically homogeneous membership profiles within any given equub.

But equubs do in fact have the potential to sustain economically diverse communities by drawing on well-established mechanisms developed to accommodate differences in individual members’ financial means and savings goals (Begashaw Citation1978). Deviating from the principle of one member, one fund, “One person can be registered two or more times by making multiple payments to the pool. On the other hand, [an] individual with limited capacity can team up with [a] similar person and register as one member” (Aredo Citation2004, 187).

In Berlin, we found a significant degree of economic differentiation both across and within equubs. Monthly contributions for a full membership ranged between €200 (Equub A and C) and €1000 (Equub G). However, all equubs allowed full shares to be split between two or more individuals, which contributed to income diversity within the group. In Equub G, for example, when members decided to raise the level of contributions, they were careful to ensure that participants with lower income would be able to afford staying in the equub:

We don’t want to lose any member. When the equub increases its contribution, those who cannot afford the full contribution should not leave. That is because this equub is beyond equub; it is like a family now. For example, if one member is able to afford only a fourth of the contribution [i.e., €250], to help her stay in the Equub, two other members, who have enough money, will add the remaining amount for her. One of them could add €500 while the other covers the €250. Then, when the fund is ready, they will share it based on the amount of their contribution.

Reciprocity and Solidarity

As one interviewee in Berlin succinctly put it, equubs represent “a voluntary obligation to save your own money.” In other words, equubs are not redistributive by design. They function according to the “principle of balanced reciprocity,” with each member “drawing from the fund as much as he/she put into it” (Bouman Citation1995, 374). At the same time, equubs nurture a strong ethos of care and solidarity, providing a space for “people to access money from trusted sources and to restore their personal dignity” (Hossein Citation2016, 126). In some equubs that allocate the fund by lottery, the winner may choose to postpone taking the fund on ethical grounds, thus allowing the needs of another member to be prioritized:

We do not sell funds to another person in this equub since the equub is based on knowing one another. I can ask another member to freely give me her fund. The decision is made between the two of us; the sebsabi does not decide. For example, I had won the fund earlier, but I did not take it because one of our members was about to give birth and she needed the money. Therefore, she asked me for the fund, and I agreed to transfer it to her. (Equub D)

Other Berlin equubs have replaced the lottery system with a mechanism of internal deliberation, a simple version of which works as follows:

I am the sebsabi of the equub. Every month, when we gather for our monthly meeting, someone says, “I will take the next round.” I write down their name and I will give them the money when we meet next month. I just give the fund to a person who needs it. If two people want to take the fund at the same time, these two people will be made to talk to each other, and they will decide to give the money to the one who needs it the most. Otherwise, the person who informed me first would be given priority. (Equub E)

In a third variation, one Berlin equub succeeded in resolving a problem of outstanding debts by inviting the debtor and creditor to join their group. For example, in Equub A, a new cycle was started to help out an elderly community member, Mr. X, who was having trouble paying back the money he had borrowed to be able to travel to Ethiopia after a long time. Both Mr. X and his creditor, Ms. Y, were invited to join the equub. The agreement was that Mr. X would commit to contributing one full share (€200) each month. Once it was his turn to receive the equub fund, the money would be directly transferred to Ms. Y in lieu of Mr. X’s debt.

During the cycle, Ms. Y also contributed two full shares (one for herself, one for her children) each month as an equub member. In addition, she took on the responsibility of sebsabi, which gave her some control over the monetary flows. At the end of the cycle, Ms. Y had received three funds: two of them based on her own savings plus the fund from Mr. X, while the latter had succeeded in paying off his debt.

Earned Trust

Trust is vitally important for the functioning of an equub as an informal financial institution. As one respondent in Equub A emphasized: “We don’t sign anything, and we don’t bring guarantors, because we are a small group and we know each other. In most cases, those who join equub are within the inner circle; they know, understand, and trust each other.” While such personal ties can serve as the basis for caring and trustful relationships, it is crucial for trust to be evidenced in the everyday functioning of the equub. The collective enactment of ethical economic subjectivities through concrete practices such as paying the equub contributions in a timely fashion, allocating the fund in a fair and transparent manner, and not defaulting after receiving the fund contributes to the (re)production of trust in the equub as a community.

The resilience of an equub is also dependent on its capacity to address conflicts that may arise and the ability to impose sanctions, if necessary. In Berlin, equub members explained that, in case of any serious transgressions, the group would deliberate internally first and turn to community elders for mediation if necessary. The threat of social and economic exclusion serves as a powerful deterrent within the Ethiopian diaspora:

Failing to properly contribute is considered a big shame … You don’t want to lose your social life. (Equub D)

In the first place, there is a serious background check before one joins the equub. If someone escapes this screening and joins the equub and behaves badly, others will somehow manage to make them finish the cycle and then they will be removed from the equub. Other equubs will also hear the news and they will not want them in their equubs. For example, there are some people whom we refused to accept as members because of previous bad experiences with equub. (Equub A)

The interviewed Ethiopians are political refugees [in the Netherlands], an experience that seems to have damaged the maintenance of trust relations among community members, who live scattered throughout the Netherlands. As political refugees with low social trust within their diaspora community, Ethiopians benefit from reciprocal relations in iqqubs that help members build earned trust. Consequently, one of the reasons for taking part in an iqqub is the need for strengthening social relations by increasing their reputation of trustworthiness. (13)

Conviviality

Equubs are convivial spaces where members meet to share experiences of everyday life. They nurture intergenerational and transnational sites of community belonging, helping new immigrants access vital information, build social networks, and develop new livelihood strategies: “Equub has the capacity to create connection, respect; it helps to lay [a financial] foundation … It would be great if our children and grandchildren use it in the future” (Equub G). Likewise, “People here [in Berlin] lead individualistic lifestyle … Equub helps us to maintain our sociality and culture. We support each other and cope with life’s challenges together” (Equub A).

These sentiments voiced by Ethiopians in Berlin are in line with findings from Canada, where diasporic mutual-aid organizations reportedly help “Ethiopians construct a meaning out of their past and present experiences and develop a new vision of life in the host society” (Mequanent Citation1996, 37). Similarly, Salamon, Kaplan, and Goldberg (Citation2009, 411) describe equubs of Ethiopian migrants in Israel as a “complex matrix of creativity in which elements of ‘tradition’ are mobilised in a new setting, not to preserve the past, but to confront the challenges of a new future.”

The convivial spaces constituted by equubs often overlap with practices embedded in other sociocultural and economic spaces. One respondent explained that their workplace equub “was established mainly for the sake of meeting and talking, at least once a month. This is because we did not have enough time at work to meet as a result of too much work” (Equub E). Other interviewees recalled how their personal ties to Christian or Muslim faith-based communities provided an impetus to join an equub. Gatherings such as Sunday church service are opportunities for equub members to socialize, discuss equub-related business, and collect monthly contributions. At the same time, equub membership may help strengthen the sense of belonging to a religious community.

Another point to emphasize is the interconnection between the convivial spaces constituted by distinct Ethiopian institutions of mutual aid,Footnote11 such as equub, mahiber,Footnote12 and idir.Footnote13 For Mequanent (Citation1996, 37), these serve “as catalysts to re-organize the dispersed Ethiopian population, and to create the social and economic resources necessary for the formation of an ‘Ethiopian’ community in the Canadian multicultural environment.” Indeed, when members in Equub G started a mahiber alongside their equub, this helped strengthen social ties within the group:

In our mahiber, we meet twice a year, during summertime and in winter. In addition, we meet when someone dies from the members’ family, when someone gives birth, when something [out of the ordinary] happens. For example, when I opened this restaurant, they came and helped me … Actually, it is like family. Therefore, it is difficult to separate the mahiber and the equub.

… You can pay [the mahiber contribution] from your pocket at the end of the year, or you can pay it immediately after receiving the [equub] fund … When you get the fund, you just take €100 from it and contribute [to the mahiber]. It is for you and your children, to eat and drink. On top of that, we give something to the church.

Although the equub and its associated mahiber serve different purposes and have separate budgets, due to the overlap in membership in the above example, they function in an organically intertwined way.

Equubs and the Diverse Economy at Large

As scholars from the Community Economies Collective remind us, “The inventory of economic difference is a profoundly political act” (Community Economies Collective Citation2019, 59). In this section, we consider the monetary flows into and out of equubs, arguing that a critical reflection of these interdependencies will open the debate to better assess the transformative potential of equubs and heighten the critical awareness on exploitative practices. Once again applying the method of reading for difference, we distinguish between the diverse sources of income that enable members to make regular contributions to an equub and the diverse uses to which equub savings are put by members.

Equub Inflows

The livelihood strategies of equub members may vary widely, comprising an array of different income-generating activities. Part of this income finds its way into the equub as member contributions. The Berlin sample included workers, self-employed persons, and the owner of a family-run business, thus indicating some degree of variety across equubs in terms of how members are positioned vis-à-vis the production, appropriation, and distribution of surplus (Resnick and Wolff Citation1987). But why should it matter whether members’ contributions to equub derive from wages, profits, rent, or other sources? While a detailed analysis of interviewees’ class positions remains beyond the scope of this essay, we would like to point out some potential implications of class difference for building community economies around equubs.

First, we argue that capitalist exploitation overdetermines the monetary inflows that sustain equubs. Let’s consider the case of an equub member who works in a capitalist enterprise, producing necessary and surplus labor. Barring any other source of income, this member’s contributions to the equub will need to come out of the wages earned (necessary labor). Thus, capitalist exploitation acts as a constraint on the worker’s savings capacity insofar as it precludes them from appropriating the surplus produced through their own work. When exploitation is exacerbated through racist discrimination in the labor market (Aikins et al. Citation2021; UN General Assembly Citation2017), it further reduces Black workers’ earnings and hence their ability to save via an equub. In short, there is an inverse relation between the size of equub inflows and the rate of capitalist exploitation and discrimination.

The reverse holds if an equub member is the owner of a capital business. In this case, the ability to contribute to the equub will depend on the size of the surplus appropriated from the workers of the enterprise. We suggest that further research is needed to critically reflect on the ethical implications of capitalist exploitation for equubs as a form of nonmarket finance. While it is somewhat plausible that exploited workers feel empowered by equubs, which accords them the opportunity to disengage from capitalist finance (even if they cannot afford to abandon their capitalist jobs), it remains unclear why capitalists would opt for the nonmarket, noncapitalist form of finance embodied by equubs in the first place. Also, how might it affect the internal cohesion of equubs when members occupy antagonistic class positions outside of the equub? Will their perceptions of solidarity be compatible enough to develop (and maintain) a set of common values?

Finally, let us look at how noncapitalist enterprises run by self-employed persons overdetermine equub inflows. The income available to a self-employed equub member is contingent on the revenue they generate through their business, which in turn depends on the surplus they produce and self-appropriate as worker-owners (among other factors). All decisions concerning the size of surplus production and the share to be allotted to the equub for savings are taken by the self-employed person alone. Here, we see an interesting interrelation between a noncapitalist enterprise with an individualistic bend and a noncapitalist form of finance with a strong collective orientation, with its own potential tensions and dilemmas.

Equub Savings

Next, we explore what futures are envisioned through equub savings: that is, how members utilize the equub fund once it is their turn to receive it. In the literature on ROSCAs, the matter has been primarily discussed in terms of incentive structures for investment (productive) versus consumption (unproductive) spending. We propose a shift in perspective, allowing for a more nuanced analysis that foregrounds the potential of equub savings to contribute toward more just economies. At the same time, we caution against romanticizing equubs. It is important to recognize that equub savings can provide a condition for exploitation: for example, when the money is used to support capitalist enterprise (Yimer et al. Citation2018). On the other hand, there is some evidence that equub savings provide opportunities for class transformation. In Canada, for example, Ethiopian immigrants purchase taxi driver license plates to pursue self-employment (Mequanent Citation1996), thus linking noncapitalist enterprise with noncapitalist finance.

We are particularly interested in the embeddedness of diasporic equubs in “global households,” defined as “an institution formed by family networks dispersed across national boundaries” (Safri and Graham Citation2015, 244). The use of equub funds to purchase household goods or to celebrate life-cycle events such as births and weddings has been well documented in the literature (Aredo Citation2004; Kedir and Ibrahim Citation2011; Besley and Coate Citation1993; Bouman Citation1995). It would be misleading to assume that such practices simply channel equub funds back into the sphere of commodity exchange. The gift economies accompanying visits from the diaspora to Ethiopia and other family gatherings can have significant redistributive effects (Mauss [Citation1925] Citation1996). Similarly, remittances can play a key role in social reproduction and can strengthen social ties within global households.Footnote14

One interviewee illustrated the connection between these two instances of nonmarket finance within the global household of the equub and remittances as follows:

I use the fund to send a large sum of money, at once, to my family in Ethiopia and to be free from constantly worrying about transferring money to Ethiopia. Transferring money to Ethiopia every month is not a good idea since it wastes time and money. For example, I sent a large sum of money recently to my family. Therefore, I will not be sending them any money for many months to come. What I will do is just keep contributing to my equub. (Equub A)

Conclusion

This essay makes a threefold contribution to the scholarship on diverse economies: First, by analyzing equubs, a model of community-based finance practiced across Ethiopian communities in Germany, it presents a unique case study on the diversity of finance. Second, the essay underlines the contributions of majority-world scholars and communities to ethical finance and thereby pinpoints how the experiential and academic knowledge on equubs produced in Ethiopia circulates transnationally, nurturing community economies in the diaspora. Third, it applies J. K. Gibson-Graham’s method of reading for difference to explore how the peer-based, solidaristic praxis of generating savings inspires an alternative to capitalist finance in the here and now. The essay emphasizes that the equub does not provide a blueprint; rather its strength lies in the praxis of collective becoming, fostered in the process of negotiating around members’ respective financial needs and goals. Nonetheless, it is crucial to also consider the broader impact of equubs and to scrutinize the realization of their potential to contribute to more just economies.

Acknowledgments

The data collection was supported through the Civil Society Leadership Award (CSLA), which is a scholarship of the Open Society Foundation (OSF) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) in Germany (grant No. IN2017-36894). The open-access publication was made possible through the ASTRA project, which is funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 955518. We thank our research participants and all the people who helped us during and after the data collection. We also thank the referees for their insightful comments and Mahssa Sotoudeh for her research assistance on this project. Disclaimer: The article reflects only the views of the authors.

Notes

1 Various other forms of spelling can be found in the literature, including equb, iqub, iqqub, and iquib. For consistency, we use the form equub throughout the text, except in direct quotations.

2 For an overview of financial institutions across the world that fall under the category of ROSCAs, see Bouman (Citation1977) and Low (Citation1995, 24).

3 The data was originally collected for Tadesse’s (Citation2020) M.A. thesis research. All quotes from equub participants are anonymized versions of these personal communications.

4 These are our own estimates based on Aikins et al. (Citation2021) and Statistisches Bundesamt, population data series 1.12, https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online.

5 See “Bilateral Migration Matrix,” KNOMAD website, updated 19 December 2022, https://www.knomad.org/data/migration/emigration.

6 See also chap. 6 in Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy (Citation2013).

7 Salamon, Kaplan, and Goldberg (Citation2009, 407) report that equubs established by Ethiopian immigrants in Israel use a combination of written by-laws, verbal rules, and “rules of conventional behavior” to guide members’ everyday interactions. In Ethiopia, as well, “When ROSCAs become bigger, both in the number of membership as well as in the amount of money, they rely more on formal and written evidence than on trust and relationships” (Yimer et al. Citation2018, 101).

8 Several interviewees noted that large equubs in Ethiopia employ sebsabis in paid positions. Large equubs have a more complex governance structure including a treasurer, president, and secretary (Aredo Citation1993; Mequanent Citation1996). The equub in Mizan-Teferi, on the other hand, in which Tadesse also participated, did not have any administrative position.

9 According to Yimer et al. (Citation2018), the tradition of legal pluralism in Ethiopia results in a complex “interaction between the formal and the informal legal cultures.” On one hand, “ROSCAs depend on the formal justice system to effectively enforce their internal laws whenever there is a deviant behavior that violates social norms and expectations of the members of the group. The fact that ROSCA leaders and members bring cases to official courts implies that they believe that the transactions in the ROSCA fall within the domain of the formal justice system and that their internal rules and values can be protected by the official laws of the land” (107). On the other hand, “ROSCAs try to minimize the risk of losing cases in court of law by adjusting their internal rules and practices to the decisions rendered by the formal courts” (109).

10 For an overview of the differences between ROSCAs and ASCRAs, see Bouman (Citation1995, 377, table 1). The acronym ASCA is also used in the literature.

11 These share some similarities with African American mutual-aid societies (Nembhard Citation2014).

12 Mahiber is an Ethiopian informal institution with social and religious purposes.

13 Idir is a multifunctional burial society and “indigenous insurance arrangement characterized by regular and ex ante payment of [a] fixed amount of money to a common pool set up by a group consisting of members who have symmetric information about each other” (Aredo Citation2010, 58).

14 According to KNOMAD and the World Bank, remittances to Ethiopia amounted to $436 million in 2021. See “Remittances Inflows,” KNOMAD website, updated 2 December 2022, https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances.

References

- Aikins, M. A., T. Bremberger, J. K. Aikins, D. Gyamerah, and D. Yıldırım-Caliman. 2021. Afrozensus 2020: Perspektiven, Anti-Schwarze Rassismuserfahrungen und Engagement Schwarzer, afrikanischer und afrodiasporischer Menschen in Deutschland. Berlin: EOTO and Citizens for Europe. https://afrozensus.de/reports/2020/Afrozensus-2020-Einzelseiten.pdf.

- Ardener, S. 1964. “The Comparative Study of Rotating Credit Associations.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 94 (2): 201–29.

- Ardener, S. 1995. “Women Making Money Go Round: ROSCAs Revisited.” In Money-Go-Rounds: The Importance of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations for Women, ed. S. Ardener and S. Burman, 1–20. Oxford: Berg.

- Aredo, D. 1993. “The Informal and Semi-Formal Financial Sectors in Ethiopia: A Study of the Iqqub, Iddir, and Savings and Credit Co-Operatives.” African Research Consortium Research Paper 21. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/13646/100306.pdf?sequence=1.

- Aredo, D. 2004. “Rotating Savings and Credit Associations: Characterization with Particular Reference to the Ethiopian Iqqub.” Savings and Development 28 (2): 179–200.

- Aredo, D. 2010. “The Iddir: An Informal Insurance Arrangement in Ethiopia.” Savings and Development 34 (1): 53–72.

- Begashaw, G. 1978. “The Economic Role of Traditional Savings and Credit Institutions in Ethiopia.” Savings and Development 2 (4): 249–64.

- Besley, T., S. Coate, and G. Loury. 1993. “The Economics of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations.” American Economic Review 83 (4): 792–810.

- Bouman, F. J. 1977. “Indigenous Savings and Credit Societies in the Third World. A Message.” Savings and Development 1 (4): 181–219.

- Bouman, F. J. 1995. “Rotating and Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations: A Development Perspective.” World Development 23 (3): 371–84.

- Community Economies Collective. 2019. “Community Economy.” In Keywords in Radical Geography: Antipode at 50, ed. Antipode Editorial Collective, 56–63. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. E-book available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.10029781119558071

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 1996. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2020. “Reading for Economic Difference.” In The Handbook of Diverse Economies, ed. J. K. Gibson-Graham and K. Dombroski, 476–85. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., J. Cameron, and S. Healy. 2013. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., and K. Dombroski. 2020. Introduction to The Handbook of Diverse Economies, ed. J. K. Gibson-Graham and K. Dombroski, 1–24. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Hossein, C. S. 2016. Politicized Microfinance: Money, Power, and Violence in the Black Americas. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Hossein, C. S. 2020. “Rotating Savings and Credit Associations: Mutual Aid Financing” In The Handbook of Diverse Economies, ed. J. K. Gibson-Graham and K. Dombroski, 354–61. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Hossein, C. S., and P. J. Christabell, eds. 2022. Community Economies in the Global South: Case Studies of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations and Economic Cooperation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kedir, A. M., and G. Ibrahim. 2011. “ROSCAs in Urban Ethiopia: Are the Characteristics of the Institutions More Important than Those of Members?” Journal of Development Studies 47 (7): 998–1016.

- Lehmann, J. M., and P. Smets. 2019. “An Innovative Resilience Approach: Financial Self-Help Groups in Contemporary Financial Landscapes in the Netherlands.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (5): 898–915.

- Low, A. 1995. A Bibliographical Survey of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations. Oxford, UK: Oxfam and CCCRW.

- Mauss, M. (1925) 1996. The Gift. Chicago: HAU.

- Mekonnen, M. B., and B. Lohnert. 2018. “Diaspora Engagement in Development.” African Diaspora 10 (1–2): 92–116.

- Mequanent, G. 1996. “The Role of Informal Organizations in Resettlement Adjustment Process: A Case Study of Iqubs, Idirs, and Mahabers in the Ethiopian Community in Toronto.” Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 15 (3): 30–40.

- Nembhard, J. G. 2014. Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Resnick, S. A., and R. D. Wolff. 1987. Knowledge and Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Safri, M., and J. Graham. 2015. “International Migration and the Global Household: Performing Diverse Economies on the World Stage.” In Making Other Worlds Possible: Performing Diverse Economies, ed. G. Roelvink, K. St. Martin, and J. K. Gibson-Graham, 244–68. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Safri, M., and Y. M. Madra. 2020. “Framing Essay: The Diversity of Finance” In The Handbook of Diverse Economies, ed. J. K. Gibson-Graham and K. Dombroski, 332–45. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Salamon, H., S. Kaplan, and H. Goldberg. 2009. “What Goes Around, Comes Around: Rotating Credit Associations among Ethiopian Women in Israel.” African Identities 7 (3): 399–415.

- Schlenzka, N. 2009. The Ethiopian Diaspora in Germany: Its Contribution to Development in Ethiopia. Eschborn, Germ.: GTZ.

- Tadesse, M. E. 2020. “The Black Social Economy in Germany: A Study of ROSCAs by Ethiopian Immigrants.” M.A. thesis, Alice Salomon Hochschule, Berlin.

- UN General Assembly. 2017. “Report of the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent on Its Mission to Germany.” Human Rights Council. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1304263.

- Warnecke, A. 2015. “Ethiopian Diaspora in Germany—Commitment to Social and Economic Development in Ethiopia.” Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. https://diaspora2030.de/fileadmin/files/Service/Publikationen/Studien_zu_Diaspora-Aktivitaeten_in_Deutschland/giz-2015-en-diasporastudy-ethiopia.pdf.

- Yimer, G. A., W. Decock, M. G. Ghebregergs, G. H. Abera, and G. S. Halibo. 2018. “The Interplay between Official and Unofficial Laws in Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (Eqqub) in Tigray, Ethiopia.” Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 50 (1): 94–113.