Abstract

Agricultural damage by geese is a growing problem in Europe and farmers play a key role in the emerging multilevel adaptive management system. This study explored how characteristics associated with the farmer and the farm, along with experience of damage, cognitive appraisals, emotions, and management beliefs were associated with the perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system among farmers in the south of Sweden (n = 1,067). Survey results revealed that owning a larger farm, a farm closer to water or formally protected areas, along with cultivating cereal and root crops, were associated with geese evoking stronger negative emotions. Further, more previous experience of damage was related to stronger negative emotions and lower levels of perceived adaptive capacity. However, even more important determinants of perceived adaptive capacity were cognitive appraisals, emotions, and management beliefs. Bridging the ties between individual farmers and the system is important for improved multilevel management.

Introduction

Since the 1930s some species of wild geese, for example, the graylag goose (Anser anser) and barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis) have increased dramatically in Europe. Underlying these changes are hunting regulations, conservation efforts, and changed agricultural practices (Fox and Madsen Citation2017). Geese contribute to the ecosystem via nutrient deposits and facilitation of plant productivity, and directly to humans in terms of a meat source, but also by enabling esthetic experiences, hunting, and ecotourism (Green and Elmberg Citation2014). Yet, the superabundance of some goose species is also associated with negative impacts on natural vegetation, air safety, and potentially increased risk of disease transmission (Buij et al. Citation2017; Fox et al. Citation2017; Bakker et al. Citation2018). One of the most highlighted disservices caused by geese is agricultural harvest loss (Conover, Butikofer, and Decker Citation2018; Montrás-Janer et al. Citation2019). Whereas modern agricultural practices have fueled the superabundance of geese, individual farmers are paying the price in terms of economic losses and time invested in managing geese.

Research on resource governance systems has revealed benefits of decision making at different levels, involvement of actor-networks through participatory processes, and continuous interactions between institutions and actors (horizontally and vertically) (Ostrom Citation1990; Carlisle and Gruby Citation2019). For most geese being migratory species, Multi-Level Governance (MLG) arrangements, spanning from international to the local level are needed to manage them (Cope, Vickery, and Rowcliffe Citation2005). A European Goose Management Platform (EGMP) was launched in 2015 under the Agreement on the Conservation of African–Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA), with the purpose to provide an adaptive, coordinated, and inclusive governance process for the management of goose populations in Europe. Because of the debates surrounding bird conservation, hunting practices, and crop damage (e.g., damage tolerance levels) (Fox and Madsen Citation2017; Harrison et al. Citation2018; Tuvendal and Elmberg Citation2015; Stroud, Madsen, and Fox Citation2017), governance and management responses require an understanding of stakeholder groups and the interactions between them and the system. Farmers engage in participatory goose management at different levels in the MLG system, and individual farmers, often the holders of hunting rights on their land, are directly involved in and impacted by the management. Previous studies have considered farmers in the context of goose management (Eythórsson, Tombre, and Madsen Citation2017; Simonsen, Tombre, and Madsen Citation2017; Tombre, Eythórsson, and Madsen Citation2013; Tuvendal and Elmberg Citation2015) and psychological factors have been found to be relevant for support of management tools (St John, Mason, and Bunnefeld Citation2021). However, the underlying reasons for the individual farmer’s reactions to geese and their perceptions of the goose management system have not been explored. Whereas emotions have been found to be associated with the acceptability of wildlife management measures (e.g., Jacobs et al. Citation2014), perceptions of wildlife management systems and how emotions influence these perceptions are understudied. The present study examined the role of cognitive appraisals and emotions as well as management beliefs for the formation of perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system among farmers in Sweden.

Conceptual Framework

Challenges associated with changes in the social-ecological system require adaptive capacity in institutions and management systems to develop a proneness and ability to change, including recovery, adjusting, and taking advantage of opportunities (Koontz et al. Citation2015). Adaptive capacity is facilitated by sufficient financial resources and knowledge, as well as flexibility, learning, agency, and trust (Cinner et al. Citation2018). Stakeholders’ perceived adaptive capacity of a management system has been examined to uncover their perceptions of the system’s capabilities (Seara, Clay, and Colburn Citation2016; Dressel et al. Citation2020). Given that farm-level management through, for example, scaring and hunting is crucial for managing geese on agricultural land, low levels of perceived adaptive capacity among farmers may result in opposition and low involvement in management, with implications for achieving goals set by the MLG system. In contrast, confidence in the capacities of the system to manage geese is likely to facilitate good relations between farmers and the system. In this paper, we consider the conditions and experiences of farmers and draw on psychological theory to outline determinants of the perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system among farmers (Eagly and Chaiken Citation1993; Dietz, Stern, and Guagnano Citation1998; Scherer Citation2001; Eriksson et al. Citation2020).

Conditions, Experiences, and Psychological Factors

Physical and social conditions, experiences, and the quality of experiences are important for peoples’ reactions, such as emotions, attitudes, and behaviors (Dietz, Stern, and Guagnano Citation1998; Eriksson et al. Citation2020). In line with this reasoning, structural and physical factors such as the gender of the farmer, the location of the farm and its size, but also farming practices including crop choice, have been found to be associated with farmers’ perceptions of wildlife and wildlife management (van Velden, Smith, and Ryan Citation2016; Kross et al. Citation2018; Krasznai and Belcher Citation2019). In addition, more experience of wildlife damage has been found to be associated with problem perceptions, lower acceptance, and tolerance (Jonker et al. Citation2006; Kansky, Kidd, and Knight Citation2014; Dressel, Sandström, and Ericsson Citation2015; van Velden, Smith, and Ryan Citation2016). Even though geese have been framed as damaging species among farmers (Goodale, Parsons, and Sherren Citation2015), the sensitivity to wildlife damage varies, indicating that the level of damage is not the only factor contributing to how damage is perceived (Kansky, Kidd, and Knight Citation2014; Hill Citation2018). Anger and worry are also embedded in human—wildlife interactions (Kansky, Kidd, and Knight Citation2016; Redpath et al. Citation2013). Hence, structural and physical factors, personal experiences of geese as well as psychological factors, such as cognitive appraisals, emotions, and beliefs are likely relevant for perceptions of the goose management system.

Cognitive Appraisals and Emotions

Emotions have been depicted in terms of interrelated changes in several of the subsystems labeled cognitive, neurophysiological, motivational, motor expression, and subjective feeling (Leventhal and Scherer Citation1987; Scherer Citation2001). The cognitive appraisal theory posits that the emotions people experience in response to a stimulus event (e.g., a wildlife encounter) are determined by their subjective cognitive appraisals of the event (Scherer Citation2001). Thus, the same type of event may evoke different emotions depending on differences in appraisal processes. When experiencing an event, four main checks are believed to occur and influence the type and strength of emotions evoked. First, the relevance of the event to one’s own goals is determined, considering both the individual and important others (e.g., family and neighbors). Second, an assessment of the implications of the event, that is, whether it facilitates or hinders important personal goals is conducted. Third, a control check (e.g., whether the event can be controlled) and a power check (e.g., whether the individual has the power to cope) determine the coping potential, and fourth, the response is evaluated in relation to internal and external norms, that is, how appropriate the response is perceived to be (labeled normative significance). The importance of cognitive appraisals for evoking negative emotions has been confirmed in relation to, for example, large carnivores (Johansson et al. Citation2012, Citation2016) and tick-borne diseases among livestock (Johansson, Mysterud, and Flykt Citation2020).

Management Beliefs

Attitude theory defines beliefs in terms of cognitions or thoughts about an object (e.g., wildlife management), and beliefs are considered essential for how objects are evaluated by individuals (Eagly and Chaiken Citation1993). Basic beliefs about wildlife or nature, also labeled “value orientations,” may reflect utilitarian (or anthropocentric) ideas where humans are allowed to dominate, or egalitarian notions reflecting the inherent value of nature and wildlife (Gagnon Thompson and Barton Citation1994; Teel et al. Citation2010). Since basic beliefs are elements in a cognitive hierarchy (Fulton, Manfredo, and Lipscomb Citation1996), notions about humans and nature are also reflected in more specific beliefs, for example, preservation, social, or economic management orientations (Eriksson et al. Citation2012; Eriksson, Nordlund, and Westin Citation2013). In addition, stakeholder groups endorse utilitarian and egalitarian standpoints to different degrees (e.g., Ehrhart, Stühlinger, and Schraml Citation2021). As stipulated by attitude theory, beliefs about management orientations, but also beliefs about actors taking part in the management, have been found to be associated with acceptability judgments and the perceived adaptive capacity of management (Diedrich et al. Citation2017; Eriksson, Björkman, and Klapwijk Citation2018; Dressel et al. Citation2020). In MLG systems with local participation, beliefs about constructive (rather than adverse) contributions of stakeholder groups taking part in management may increase the perceived adaptive capacity of the management system.

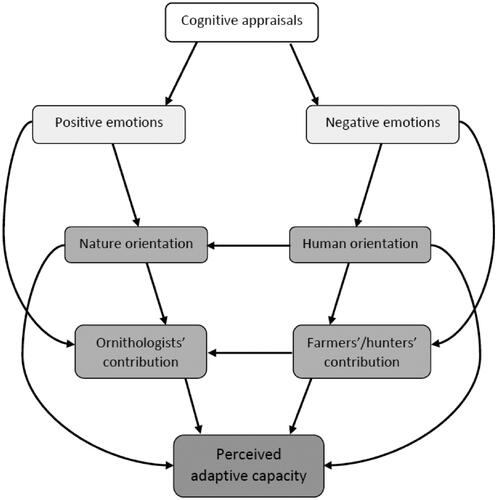

Conceptual Model

Based on the research of cognitive appraisal processes, emotions, and management beliefs, we outlined the psychological determinants of the perceived adaptive capacity of the management system (see ). The cognitive appraisal process of geese was expected to determine the emotions they evoke, with a more positive appraisal process being associated with stronger positive emotions and weaker negative emotions (Scherer Citation2001). Since emotions are important for how individuals respond to events (Reser and Swim Citation2011), the emotions geese evoke were supposedly important for beliefs about goose management. Finally, management beliefs were assumed to be important for the perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system (cf. Eriksson, Björkman, and Klapwijk Citation2018). Hence, cognitive appraisals of geese and emotions were outlined as a basis for beliefs about goose management and perceptions of the management system. Management beliefs reflecting management orientations (i.e., nature and human) and beliefs about stakeholders taking part in management (e.g., farmers, hunters, and ornithologists) were considered in the model. Because a distinction can be made between a utilitarian versus an egalitarian view on nature and wildlife (see above), appraisals, emotions, and beliefs were expected to influence perceived adaptive capacity via two main pathways. Stronger negative emotions evoked by geese were expected to be associated with beliefs in human-oriented management and in beliefs that stakeholder organizations endorsing utilitarian matters (e.g., farmers and hunters) contribute constructively to management, that is, a utilitarian focus (right side of ). In contrast, positive emotions were expected to be linked to beliefs in nature-oriented management and beliefs that wildlife and nature-focused organizations (e.g., ornithologists) contribute constructively to management, that is, an egalitarian focus (left side of ). Since management beliefs tend to be correlated, as part of the intra-attitudinal structure (Eagly and Chaiken Citation1993; Eriksson, Björkman, and Klapwijk Citation2018), links between the pathways were anticipated via beliefs about management orientation (human and nature) and beliefs about the contribution of stakeholder organizations (farmers, hunters, and ornithologists), respectively.

The Present Study

The aim of this study was to explore predictors of emotions and perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system in a representative sample of farmers in the south of Sweden, a region with long-standing and increasing levels of crop damage by geese (Montrás-Janer et al. Citation2020). This was done in two steps following the conceptual framework. First, the importance of conditions associated with the farmer and the farm as well as experience of goose damage for emotions and perceived adaptive capacity, respectively, were examined. Second, as outlined in , the importance of psychological factors to the perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system was examined in a path model.

Materials and Methods

Study Context

Agricultural land is prevalent in the south of Sweden, where also the bulk of important goose areas close to lakes and wetlands are located, with associated damage to adjacent farms (Nilsson Citation2013; Montrás-Janer et al. Citation2020). Crop damage through foraging and trampling is caused by several goose species, for example, barnacle goose and graylag goose (Montrás-Janer et al. Citation2019). The MLG system of geese involves regulatory bodies; the government and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) at the national level and the County Administrative Boards at the regional level. In addition, AEWA is an intergovernmental treaty developing, for example, international management plans. A management collaboration platform, EGMP, is operating in Europe under the AEWA framework. In Sweden, the national council for large grazing birds, and in some locations, local management groups, are participatory bodies within the goose management.

Sample

A postal questionnaire was sent to a sample of farmers 20–67 years of age with an active farming business, in 13 counties in the south of Sweden (Skåne, Halland, Västra Götaland, Östergötland, Gotland, Jönköping, Kronoberg, Kalmar, Örebro, Västmanland, Uppsala, Södermanland, and Blekinge). Statistics Sweden provided the sample based on a simple random sampling method and a commercial survey company, Kvalitetsindikator AB, distributed the survey in the spring of 2019. To allow for multivariate analyses, the net sample consisted of 2,973 farmers. After two reminders the response rate was 36% (n = 1,067). An analysis of the attrition revealed that the sample was representative when it comes to postal code area and classification of activity according to the Swedish Standard Industrial Classification (SNI) (including relevant farming categories). However, compared to the attrition group, the respondents were slightly older (55 compared to 53 years, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.01), women were slightly overrepresented (19% versus 16%, p = 0.047, rpb = 0.04), and owned somewhat larger farms (78.8 ha versus 67.8 ha, p = 0.016, partial η2 = 0.00). Even though the deviations were minor, they may be important to consider when interpreting the results.

Measures

Questions relevant to this study are summarized below and described in detail in the Supplemental online material. The interdisciplinary team of authors prepared the questionnaire. Measures were developed to assess theoretical concepts, and operationalizations of measures in previous research guided the construction of questions. The measures for cognitive appraisals, emotions, and management orientation beliefs had previously been evaluated in a sample of the general public (also including farmers) (Eriksson et al. Citation2020).

The farmer and the farm

Data about farmers’ gender and age, as well as farm size, were drawn from the land register. In addition, the questionnaire contained detailed questions about the farm, including; (a) distance to the closest lake, wetland, or watercourse, (b) distance to the closest formally protected area (e.g., national park, nature reserve, or Natura 2000) using five response options from “bordering” to “farther away than 3000 meters” as well as a “don’t know” option. Moreover, the questionnaire included questions about crop types, that is, whether cereal, rapeseed, sugar beets, and potatoes were cultivated on the farm. The physical indicators were partly selected based on knowledge of the habitat and food selection of geese (Olsson, Gunnarsson, and Elmberg Citation2017; Montrás-Janer et al. Citation2020).

Experience of Goose Damage

The extent of damage (consumption of plants as well as by trampling and grubbing) by six goose species and mixed flocks (seven items) was assessed using a five-point scale (from “not at all” to “to a great extent”). In addition, farmers with experience of damage answered a question about the number of weeks each year this had occurred (i.e., 1–4 weeks, 5–8 weeks, 9–12 weeks, more than 12 weeks).

Cognitive Appraisals and Emotions

Based on Scherer (Citation2001) appraisals of the relevance (e.g., to what extent the current occurrence of geese influences possibilities to reach personal goals), implications (e.g., whether the current occurrence of geese hinders or facilitates personal goals), coping potential (e.g., whether there are operational measures to manage geese), and normative significance (e.g., to what extent there is correspondence between current management and how the farmer perceives geese should be managed) were assessed by means of 15 items using five-point response scales (1–5). In addition, a “don’t know” response option was available for the coping potential and normative significance questions since not all farmers may be familiar with goose management. The “don’t know” answers were removed and four relevant items, as well as one coping potential item, were reversed. Subsequently, the means of the items were calculated, with a higher value representing a more positive appraisal process of geese (α = 0.84, n = 1,010). Also, the extent to which geese evoke seven negative emotions, including sadness, despair, worry, disgust, anger, fear, and irritation, and five positive emotions including relief, enthusiasm, pleasure, interest, and joy, was assessed using a seven-point response scale (0–6) (Eriksson et al. Citation2020). A factor analysis with varimax rotation based on the 12 items confirmed two factors with negative and positive emotions (eigenvalues = 4.89 and 3.43) explaining 69% of the variance (α = 0.91, n = 1,003 and α = 0.91, n = 991, respectively).

Management Beliefs and Perceived Adaptive Capacity

Beliefs about human-oriented goose management versus nature-oriented management were assessed by means of six items covering the importance given to, for example, the rights of geese and livelihood of humans using a five-point response scale (1–5) (cf. Buij et al. Citation2017). An exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted on the belief statements. The eigenvalues were 2.63 and 1.52, explaining 69% of the variance. The two factors were labeled “human orientation” (α = 0.79, n = 988) and “nature orientation” (α = 0.72, n = 980), respectively. In addition, beliefs about the constructive contribution to goose management by farmers’ federations, hunters’ organizations, and ornithological societies at regional and national levels were measured using six items (cf. Buij et al. Citation2017). A five-point response scale (1–5) and a “don’t know” option were utilized. After removing “don’t know” answers, exploratory factor analysis was conducted. The eigenvalues were 3.43 and 1.35, explaining 80% of the variance. The two factors were labeled “farmers’/hunters’ contribution” (α = 0.87, n = 602) and “ornithologists” contribution’ (α = 0.94, n = 484), respectively. The perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system was assessed using seven statements, reflecting regulations, resources, knowledge, fairness, adaptability, cooperation, and openness, as well as four items measuring trust in actors at the local to international level, using five-point scales (1–5) as well as a “don’t know” response option (cf. Cinner et al. Citation2018; Lockwood et al. Citation2010). After removing “don’t know” answers, the means of the trust items were calculated to create a measure of trust. Subsequently, an exploratory factor analysis including the seven statements and the trust measure revealed a single component (eigenvalue 4.41) explaining 55% of the variance (α = 0.88, n = 761).

Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 24 (IBM Corp Citation2016), except the path analyses for which AMOS 24 (Arbuckle Citation2016) was used. The farmers were divided into three groups based on damage experience; no damage, moderate damage (farmers answering 2 or 3 to the question about the experience of goose damage by different species and with less than 9 weeks of damage/year), and extensive damage (farmers answering 4 or 5 on the question about damage experience and farmers answering 2 or 3 to that question but with damage ongoing for 9 weeks or more per year) (missing = 118). For descriptive purposes, we calculated means and standard deviations for the psychological variables in three groups of farmers with different levels of damage experience. Univariate ANOVAs with the group as the independent variable and the psychological variables as dependent variables were conducted to analyze differences among groups (including pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction and partial η2 to assess effect size). To address the first aim, three hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted with characteristics associated with the farmer and the farm, as well as damage experience as independent variables, and emotions (negative and positive) and perceived adaptive capacity as dependent variables, respectively. Dummy variables were created for gender, age, farm size, water nearby farm, a protected land nearby farm, and the cultivation of three different crops (i.e., cereal, rapeseed, and root crop (potatoes or sugar beet)). In addition, two dummy variables for the experience of goose damage were created, reflecting the importance of damage versus no damage and extensive damage versus no or moderate damage. In the first step, the characteristics of the farmer and the farm were included. In the second step, the variables reflecting goose damage experience were added. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to test for multicollinearity among the independent variables.

To address the second aim, the psychological predictors of perceived adaptive capacity were examined using a confirmatory approach by means of a path analysis. The maximum likelihood estimation method was used, and since there were missing values in the data set, means and intercepts were estimated. First, the basic model outlined in was tested. However, since cognitive appraisals of geese may be directly associated with management cognitions, as part of the inter-attitudinal structure (in particular management orientation beliefs and perceived adaptive capacity), an extended model with three additional paths was subsequently tested. Two absolute fit indices (chi-square and the root mean squared error of approximation, RMSEA) and one relative fit index (Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index, CFI) were used to assess model fit. As suggested by Browne and Cudeck (Citation1993), an RMSEA value of 0.05 or lower was considered indicative of a good fit (the p-value of close fit (PCLOSE) reveals whether the RMSEA value significantly differs from 0.05). In line with Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), a CFI value of 0.95 or higher was considered a fairly good fit. In addition to path coefficients, standardized multiple correlations were reported for the endogenous variables to determine the level of explained variance, and the standardized indirect, direct, and total effects on perceived adaptive capacity were stated for each of the variables in the model.

Results

The farmers owned on average 73 hectares (SD = 21) of land. Although 40% of them worked more than half the time on their farm, the majority, 76%, had other work on the side. The largest share, 41% of the farmers, cultivated cereal, 14% grew rapeseed, and 9% root crops. Only a lesser share, 17%, stated that they went bird hunting (e.g., geese) at least once a year. Half of the farmers owned land close to a wetland or other water and 15% had property close to formally protected land (≤200 m).

Descriptives

The “no damage” group was the largest (n = 465), followed by the “moderate damage” group (n = 309), and finally the “extensive damage” group (n = 175). Means and standard deviations for cognitive appraisals, emotions, and management beliefs in the three groups of farmers are shown in . Results revealed that geese did not evoke intense emotions among farmers, but the strongest negative emotions were evident in the group having experienced extensive goose damage. The farmers favored human-oriented more than nature-oriented management, and they believed that farmers/hunters contribute constructively to management to a greater extent than ornithologists do. Perceived adaptive capacity was below the midpoint of the scale. Whereas differences among the groups were substantial for cognitive appraisals and negative emotions, they were less pronounced for positive emotions, management beliefs, and perceived adaptive capacity. No significant group difference was found for beliefs about farmers’/hunters’ contribution.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for psychological variables in the three groups of farmers with different levels of goose damage experience.

The Role of the Farmer, the Farm, and Experience of Damage

Results from the hierarchical regression analyses are found in . There was not any evidence of collinearity among the predictors (VIF < 1.45 in all models). In the first step, farm characteristics explained a significant amount of variance only with respect to negative emotions (11%). Owning a larger farm, a farm closer to water or to formally protected land, as well as cultivating cereal and root crops, were all associated with geese evoking stronger negative emotions. Neither gender nor age was associated with emotions, although in the first step, women perceived the adaptive capacity of the goose management system to be slightly higher than did men. By including the experience of damage in the second step, the share of explained variance in negative emotions and perceived adaptive capacity increased significantly. More damage experience was associated with stronger negative emotions toward geese and lower perceived adaptive capacity, explaining 30% and 6% of the variance, respectively. Having extensive experience of damage (as compared to no or moderate) was furthermore associated with weaker positive emotions, but predictors only explained a very small share of the variance (1%).

Table 2. Three hierarchical linear regression models examining the importance of (a) farmer and farm characteristics, and (b) experience of damage for negative emotions, positive emotions, and perceived adaptive capacity, respectively.

Path Analysis of Psychological Predictors

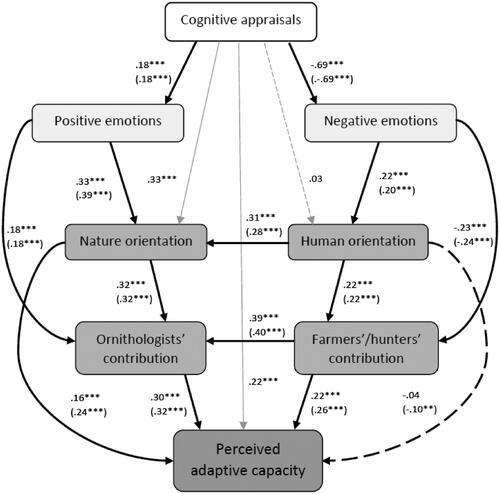

Results from the path analysis are presented in and (standard errors for path coefficients are available in the Supplementary material). Analysis of the basic model (bold paths) revealed that all paths were significant, but the model fit was poor. The extended model (bold and gray paths) showed a good model fit, but the path between cognitive appraisals and beliefs about human-oriented management, as well as between human-oriented management and perceived adaptive capacity were not significant. The path coefficients and the explained variance in the endogenous variables were comparable in the tested models. Positive cognitive appraisals were associated with stronger positive emotions and weaker negative emotions toward geese. In addition, positive emotions were related to nature-oriented management beliefs, the constructive contributions of ornithologists, and the higher perceived adaptive capacity of the goose management system. In contrast, negative emotions were associated with human-oriented management, which in turn was associated with beliefs in the constructive contribution to management by farmers/hunters and a higher perceived adaptive capacity of the system. However, stronger negative emotions were also associated with beliefs reflecting that farmers/hunters contribute less constructively to management. Beliefs about nature and human management orientations and beliefs about the contribution of ornithologists and farmers/hunters were positively correlated. While cognitive appraisals explained a significant share of the variance in negative emotions (47%), only 3% of the variance in positive emotions was explained by appraisals. Explained variance in perceived adaptive capacity was 38% in the extended model. While emotions had stronger indirect effects on perceived adaptive capacity (via management beliefs), the influence of cognitive appraisals was both direct and indirect. Overall, results revealed that farm characteristics (i.e., farm size, water and protected land nearby farm, and cultivation of cereal and root crops) were associated with negative emotions, and experience of goose damage was related to both negative emotions and perceived adaptive capacity of the system. However, psychological variables explained a larger share of the variance in outcome variables.

Figure 2. Psychological predictors of perceived adaptive capacity in a path model (bold paths = basic model, gray paths = additional paths in extended model, dotted lines = non-significant paths, path coefficients in extended model (in brackets, path coefficients in basic model)).

Table 3. Model summary for the basic and extended path models.

Discussion and Conclusion

The superabundance of geese in Europe calls for improved and comprehensive governance and management actions as well as stakeholder participation at all levels in the governance system. Adding to the research of stakeholders within MLG systems (Dressel et al. Citation2020), this study elaborates on the links between the MLG of geese and individual farmers. Understanding farmers’ reactions to geese and their perceptions of the goose management system is important for the development of a legitimate and inclusive system.

Emotional reactions to wildlife have mainly been examined with respect to potentially dangerous animals, such as bears and wolves (Johansson et al. Citation2012, Citation2016; Jacobs et al. Citation2014), and only recently have emotions evoked by other wildlife, such as seals and geese, been considered (Eriksson et al. Citation2020; Johansson and Waldo Citation2021; St John et al. Citation2021). More experience of damage by large carnivores has been found to be associated with a more negative attitude toward those species (Dressel, Sandström, and Ericsson Citation2015). In line with such results, the present study revealed that more experience of damage by geese was associated with geese evoking stronger negative emotions and less experience of damage was related to geese evoking slightly stronger positive emotions. A higher level of perceived adaptive capacity was associated with less experience of damage, but not with farmer and farm characteristics, indicating that this assessment relies more heavily on individual-level experiences and appraisals.

Our results confirm the need to consider appraisal processes to understand why geese evoke negative emotions among farmers and verify that cognitive appraisals and emotions feed into farmers’ perceptions of the goose management system. Thus, cognitive appraisal theory (Scherer Citation2001) may not only clarify individual reactions to wildlife but also how people react to management. In line with previous research (Eriksson, Björkman, and Klapwijk Citation2018), the need to consider management beliefs were confirmed. The suggested egalitarian pathway, including positive emotions, belief in nature-oriented management, and constructive contribution of ornithologists, was somewhat more important for considering the goose management system in Sweden to hold adaptive capacities than the corresponding utilitarian pathway. By demonstrating an association between beliefs in nature-oriented management and a favorable view on the goose management system, our study suggests that the farmers perceive the system to favor preservation rather than utilization. Since the strategy for Swedish wildlife management highlights the balance between use and preservation (SEPA Citation2015), our result may reflect a mismatch between farmers’ perceptions and actual management, or inconsistency between the strategy and implemented management. However, beliefs reflecting human and nature management orientations were positively correlated, indicating that they are not considered contradictory. Our study further supports the need to shift from mainly concentrating on human–wildlife interactions to also taking into consideration relations between humans (Redpath et al. Citation2013), and how human-human interactions may be handled on different governance levels. We also found that for a positive outlook on the goose management system, it was important that farmers believe in the constructive contribution of different stakeholder organizations. This may be particularly important in a MLG system with stakeholder participation.

The structural characteristics of the sample did not deviate greatly from the population of farmers in the south of Sweden. However, since farmers with larger farms were overrepresented, the farming business may have been more important to the respondents than to non-respondents. Moreover, previous research suggests that wildlife damage may be overestimated by farmers (Haney and Conover Citation2013) and perceived damage does not always correspond to physical factors, for example, crop profiles (van Velden, Smith, and Ryan Citation2016). Whereas an overestimation of damage may also be present in our study, uncovering farmers’ perceptions of damage are important since these experiences are related to their reactions to geese and perceptions of the system. Given that statistics about compensation paid to farmers may underestimate damage levels, as such data depend on the farmers’ willingness to report them, and on assessment methods (USDA Citation2005), overall damage estimates should rely on several types of data.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. Since this was a cross-sectional study, conclusions regarding causality between predictors and dependent variables are not possible. However, the model was theoretically derived, measures showed good reliability, and the explained variance in perceived adaptive capacity was reasonably high. Whereas cognitive appraisals explained a fair share of the variance in negative emotions, the explained variance in positive emotions was low, highlighting a need to review the items used to assess appraisals and consider alternative predictors. The inclusion of a “don’t know” option for some questions was important to ensure that all farmers were able to respond, but as a consequence, the regression model of perceived adaptive capacity had to be tested on reduced sample size and missing values had to be estimated in the path model. Nevertheless, the sample size was considered sufficient. Whereas the sample showed slight deviations from the overall population of farmers, demographics had a minor impact on study variables.

This study integrates human dimensions of wildlife theory and research with psychological theory to provide insights important for engaging farmers in goose management at the local level, but also for efforts at regional, national, and international levels where management recommendations are outlined. Whereas our study confirmed the importance of damage experience for negative emotional reactions to geese, an understanding of appraisal processes, positive and negative emotions, as well as management beliefs proved to be even more important for how the system is perceived among farmers. Because bridging ties between institutions and stakeholders is imperative in MLG systems (Ragland, Bernacchi, and Peterson Citation2015; Diedrich et al. Citation2017), insights from this study may be used to facilitate effective and legitimate MLG of geese. For example, the study suggests that direct management measures, such as population management, scaring, and habitat management (Fox et al. Citation2017) are likely necessary to reduce damage and thereby dampen negative emotions among farmers as well as reduce strains on relations between humans. However, the level of acceptance for different measures among different stakeholder groups, as well as the behaviors of geese should be considered when determining appropriate measures. In addition, it may be necessary to adapt laws to allow for effective adaptive management (Craig et al. Citation2017) or implement new policy instruments such as monetary instruments (e.g., conservation incentive payments), or information-based instruments (e.g., co-management). To avoid polarization between stakeholder groups, but also to facilitate positive appraisal processes of geese, and make the goals of goose management more transparent, pro-active communication and collaboration are needed. Inclusive participatory efforts require interactions with organized stakeholder organizations, but also accounting for individuals with different perspectives and experiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating farmers and reviewers for their helpful comments to improve the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arbuckle, J. L. 2016. Amos. Version 24.0. [Computer Program]. Armonk, NY: IBM SPSS.

- Bakker, E. S., C. G. F. Veen, G. J. N. Ter Heerdt, N. Huig, and J. M. Sarneel. 2018. High grazing pressure of geese threatens conservation and restoration of reed belts. Frontiers in Plant Science 9:1649. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01649.

- Browne, M. W., and R. Cudeck. 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing structural equation models, ed. K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long, 136–62. New Park, CA: SAGE.

- Buij, R., T. C. P. Melman, M. J. J. E. Loonen, and A. D. Fox. 2017. Balancing ecosystem function, services and disservices resulting from expanding goose populations. Ambio 46 (2):301–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0902-1.

- Carlisle, K., and R. L. Gruby. 2019. Polycentric systems of governance: A theoretical model for the commons. Policy Studies Journal 47 (4):927–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12212.

- Cinner, J. E., W. N. Adger, E. H. Allison, M. L. Barnes, K. Brown, P. J. Cohen, S. Gelcich, C. C. Hicks, T. P. Hughes, J. Lau, et al. 2018. Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nature Climate Change 8 (2):117–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-017-0065-x.

- Conover, M. R., E. Butikofer, and D. J. Decker. 2018. Wildlife damage to crops: Perceptions of agricultural and wildlife leaders in 1957, 1987, and 2017. Wildlife Society Bulletin 42 (4):551–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.930.

- Cope, D., J. Vickery, and M. Rowcliffe. 2005. People and wildlife. Conflict or coexistence? In Conservation biology, ed. R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, and A. Rabinowitz, 176–91. London, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Craig, R. K., J. B. Ruhl, E. D. Brown, and B. K. Williams. 2017. A proposal for amending administrative law to facilitate adaptive management. Environmental Research Letters 12 (7):074018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7037.

- Diedrich, A., N. Stoeckl, G. G. Gurney, M. Esparon, and R. Pollnac. 2017. Social capital as a key determinant of perceived benefits of community-based marine protected areas. Conservation Biology 31 (2):311–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12808.

- Dietz, T., P. C. Stern, and G. A. Guagnano. 1998. Social structural and social psychological bases of environmental concern. Environment and Behavior 30 (4):450–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659803000402.

- Dressel, S., C. Sandström, and G. Ericsson. 2015. A meta-analysis of studies on attitudes toward bears and wolves across Europe 1976-2012. Conservation Biology 29 (2):565–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12420.

- Dressel, S., M. Johansson, G. Ericsson, and C. Sandström. 2020. Perceived adaptive capacity within a multi-level governance setting: The role of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital. Environmental Science & Policy 104:88–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.11.011.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. Chaiken. 1993. The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

- Ehrhart, S., M. Stühlinger, and U. Schraml. 2021. The relationship of stakeholders’ social identities and wildlife value orientations with attitudes toward red deer management. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2021.1885767.

- Eriksson, L., A. Nordlund, and K. Westin. 2013. The general public’s support for forest policy in Sweden: A value belief approach. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 56 (6):850–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.708324.

- Eriksson, L., A. Nordlund, O. Olsson, and K. Westin. 2012. Beliefs about urban fringe forests among urban residents in Sweden. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11 (3):321–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.02.004.

- Eriksson, L., C. Björkman, and M. J. Klapwijk. 2018. General public acceptance of forest risk management strategies in Sweden: Comparing three approaches to acceptability. Environment and Behavior 50 (2):159–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517691325.

- Eriksson, L., M. Johansson, J. Månsson, S. Redpath, C. Sandström, and J. Elmberg. 2020. The public and geese: A conflict on the rise? Human Dimensions of Wildlife 25 (5):421–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2020.1752420.

- Eythórsson, E., I. M. Tombre, and J. Madsen. 2017. Goose management schemes to resolve conflicts with agriculture: Theory, practice and effects. Ambio 46 (2):231–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0884-4.

- Fox, A. D., and J. Madsen. 2017. Threatened species to super-abundance: The unexpected international implications of successful goose conservation. Ambio 46 (2):179–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0878-2.

- Fox, A. D., J. Elmberg, I. M. Tombre, and R. Hessel. 2017. Agriculture and herbivorous waterfowl: A review of the scientific basis for improved management. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 92 (2):854–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12258.

- Fulton, D. C., M. J. Manfredo, and J. Lipscomb. 1996. Wildlife value orientations: A conceptual and measurement approach. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 1 (2):24–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209609359060.

- Gagnon Thompson, S. C., and M. A. Barton. 1994. Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 14 (2):149–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80168-9.

- Goodale, K., G. J. Parsons, and K. Sherren. 2015. The nature of the nuisance – Damage or threat – Determines how perceived monetary costs and cultural benefits influence farmer tolerance of wildlife. Diversity 7 (3):318–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/d7030318.

- Green, A. J., and J. Elmberg. 2014. Ecosystem services provided by waterbirds. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 89 (1):105–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12045.

- Haney, M. J., and M. R. Conover. 2013. Ungulate damage to safflower in Utah. The Journal of Wildlife Management 77 (2):282–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.448.

- Harrison, A. L., N. Petkov, D. Mitev, G. Popgeorgiev, B. Gove, and G. M. Hilton. 2018. Scale-dependent habitat selection by wintering geese: Implications for landscape management. Biodiversity and Conservation 27 (1):167–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1427-4.

- Hill, C. M. 2018. Crop foraging, crop losses, and crop raiding. Annual Review of Anthropology 47 (1):377–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102317-050022.

- Hu, L.-T., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1):1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

- IBM Corp. 2016. IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Jacobs, M. H., J. J. Vaske, S. Dubois, and P. Fehres. 2014. More than fear: Role of emotions in acceptability of lethal control of wolves. European Journal of Wildlife Research 60 (4):589–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-014-0823-2.

- Johansson, M., A. Mysterud, and A. Flykt. 2020. Livestock owners’ worry and fear of tick-borne diseases. Parasites & Vectors 13 (1):331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04162-7.

- Johansson, M., and Å. Waldo. 2021. Local people’s appraisal of the fishery-seal situation in traditional fishing villages on the Baltic Sea Coast in Southeast Sweden. Society & Natural Resources 34 (3):271–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2020.1809756.

- Johansson, M., C. Sandström, E. Pedersen, and G. Ericsson. 2016. Factors governing human fear of wolves: Moderating effects of geographical location and standpoint on protected nature. European Journal of Wildlife Research 62 (6):749–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-016-1054-5.

- Johansson, M., J. Karlsson, E. Pedersen, and A. Flykt. 2012. Factors governing human fear of brown bear and wolf. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 17 (1):58–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2012.619001.

- Jonker, S. A., R. M. Muth, J. F. Organ, R. R. Zwick, and W. F. Siemer. 2006. Experiences with beaver damage and attitudes of Massachusetts residents toward beaver. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34 (4):1009–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.2193/0091-7648(2006)34[1009:EWBDAA.2.0.CO;2]

- Kansky, R., M. Kidd, and A. T. Knight. 2014. Meta-analysis of attitudes toward damage-causing mammalian wildlife. Conservation Biology 28 (4):924–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12275.

- Kansky, R., M. Kidd, and A. T. Knight. 2016. A wildlife tolerance model and case study for understanding human wildlife conflicts. Biological Conservation 201:137–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.002.

- Koontz, T. M., D. Gupta, P. Mudliar, and P. Ranjan. 2015. Adaptive institutions in social-ecological systems governance: A synthesis framework. Environmental Science & Policy 53:139–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.01.003.

- Krasznai, A., and K. Belcher. 2019. Farmer attitudes and preferences regarding a hypothetical lease hunting policy in Saskatchewan. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 24 (2):116–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2018.1551585.

- Kross, S. M., K. P. Ingram, R. F. Long, and M. T. Niles. 2018. Farmer perceptions and behaviors related to wildlife and on-farm conservation actions. Conservation Letters 11 (1):e12364–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12364.

- Leventhal, H., and K. R. Scherer. 1987. The relationship of emotion to cognition: A functional approach to a semantic controversy. Cognition & Emotion 1 (1):3–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699938708408361.

- Lockwood, M., J. Davidson, A. Curtis, E. Stratford, and R. Griffith. 2010. Governance principles for natural resource management. Society & Natural Resources 23 (10):986–1001. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802178214.

- Montrás-Janer, T., J. Knape, M. Stoessel, L. Nilsson, I. Tombre, T. Pärt, and J. Månsson. 2020. Spatio-temporal patterns of crop damage caused by geese, swans and cranes – Implications for crop damage prevention. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 300:107001. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107001.

- Montrás-Janer, T., J. Knape, L. Nilsson, I. Tombre, T. Pärt, and J. Månsson. 2019. Relating national levels of crop damage to the abundance of large grazing birds: Implications for management. Journal of Applied Ecology 56 (10):2286–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13457.

- Nilsson, L. 2013. Censuses of autumn staging and wintering goose populations in Sweden 1977/1978–2011/2012. Ornis Svecica 23 (1):3–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.34080/os.v23.22581.

- Olsson, C., G. Gunnarsson, and J. Elmberg. 2017. Field preference of Greylag geese Anser anser during the breeding season. European Journal of Wildlife Research 63 (1):28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-017-1086-5.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ragland, C. J., L. A. Bernacchi, and T. R. Peterson. 2015. The role of social capital in endangered species management: A valuable resource. Wildlife Society Bulletin 39 (4):689–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.602.

- Redpath, S. M., J. Young, A. Evely, W. M. Adams, W. J. Sutherland, A. Whitehouse, A. Amar, R. A. Lambert, J. D. C. Linnell, A. Watt, et al. 2013. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28 (2):100–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.08.021.

- Reser, J. P., and J. K. Swim. 2011. Adapting to and coping with the threat and impacts of climate change. The American Psychologist 66 (4):277–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023412.

- Scherer, K. R. 2001. Appraisal considered as a process of multi-level sequential checking. In Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research, ed. K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr and T. Johnstone, 92–120. New York, NY; Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Seara, T., P. M. Clay, and L. L. Colburn. 2016. Perceived adaptive capacity and natural disasters: A fisheries case study. Global Environmental Change 38:49–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.01.006.

- SEPA. 2015. Strategi för svensk viltförvaltning – med mål och åtgärder för naturvårdsverket. Stockholm, Sweden: SEPA.

- Simonsen, C. E., I. M. Tombre, and J. Madsen. 2017. Scaring as a tool to alleviate crop damage by geese: Revealing differences between farmers’ perceptions and the scale of the problem. Ambio 46 (2):319–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0891-5.

- St John, F. A. V., T. H. E. Mason, and N. Bunnefeld. 2021. The role of risk perception and affect in predicting support for conservation policy under rapid ecosystem change. Conservation Science and Practice 3 (2):e316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.316.

- Stroud, D. A., J. Madsen, and A. D. Fox. 2017. Key actions towards the sustainable management of European geese. Ambio 46 (2):328–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0903-0.

- Teel, T. L., M. J. Manfredo, F. S. Jensen, A. E. Buijs, A. Fischer, C. Riepe, R. Arlinghaus, and M. H. Jacobs. 2010. Understanding the cognitive basis for human—wildlife relationships as a key to successful protected-area management. International Journal of Sociology 40 (3):104–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/IJS0020-7659400306.

- Tombre, I. M., E. Eythórsson, and J. Madsen. 2013. Stakeholder involvement in adaptive goose management; case studies and experiences from Norway. Ornis Norvegica 36:17–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.15845/on.v36i0.430.

- Tuvendal, M., and J. Elmberg. 2015. A handshake between markets and hierarchies: Geese as an example of successful collaborative management of ecosystem services. Sustainability 7 (12):15937–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su71215794.

- USDA. 2005. Final environmental impact statement: Resident Canada Goose management. Washington, DC: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

- van Velden, J. L., T. Smith, and P. G. Ryan. 2016. Cranes and crops: Investigating farmer tolerances toward crop damage by threatened blue cranes (Anthropoides paradiseus) in the Western Cape, South Africa. Environmental Management 58 (6):972–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0768-1.