Abstract

Peru has shifted away from centralized mining management to governance among government, companies, and communities. Various mechanisms facilitate community participation, including the mining canon, dialogues, and corporate social responsibility programs. Even with these laws and mechanisms, mining pollution and conflicts continue. In this study, we ask: how do communities perceive and participate in mining governance? And what are some alternative ways, driven by community priorities, to address governance in mining contexts? We collected 53 semi-structured with agricultural actors in two Peruvian districts with mining activity and analyzed those perspectives through the lens of community-centered governance. Our analyses revealed how centering community priorities in data collection and analysis illuminates context-specific factors that shape community attitudes toward mining and highlights community-driven approaches to addressing mining governance. Such community-driven approaches could include integrating understandings of local livelihoods and historical contexts, implementing transparent participatory processes, and improving laws to give communities decision-making power over mining development.

Introduction

During the 1980s, mining development in Peru was mainly conducted by state-owned enterprises (The World Bank Citation2005). However, over the last three decades, Peru, along with many other countries, has shifted its management of mines from centralized, government-controlled policymaking to more decentralized governance arrangements involving public, private, civil society, and community actors (Adam et al. Citation2021; Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011; Verbrugge Citation2015). This shift stimulated the implementation of various arrangements and mechanisms to support effective mining and resources governance, processes, and approaches that aimed to improve the effectiveness of government decision-making. First, mining companies have increasingly implemented corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011). Second, the government created decentralized mining laws to support subnational governments and collaborations across governments, mining companies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and communities (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011). Most notably, the Peruvian government created the mining canon, which diverts a significant portion of corporate income tax collected from mining companies and mining royalties to subnational governments (i.e., departments, provinces, districts) in mining areas (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011, Citation2019; Aresti Citation2016) (Supplement A). Third, the Peruvian legal framework requires community participation, particularly public participation as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and General Environmental Law, and prior consultation and informed consent for Indigenous Peoples (Supplement A).

Together, these governance arrangements and mechanisms aim to enhance sustainable development by increasing the participation of those most impacted by mining and other resource development projects; however, the results of these efforts are mixed. For instance, the Peruvian government has enacted several laws to increase the involvement of affected communities in the approval process of new infrastructure projects, but the forms and extent of such involvement are not clearly delineated. This includes Law No. 29785, which states that Indigenous Peoples. While this law gives the right to prior consultation for Indigenous Peoples before mining development, it also designates an authority, often a government official, to decide if and how concerns raised through such community consultation will be addressed (Jaskoski Citation2014; Rey-Coquais Citation2021). In the end, communities do not have the legal power to veto proposed mining projects. In light of such a lack of decision authority, communities have pursued several avenues to voice their concerns and exercise power in mining governance. Some encourage mining companies to seek a Social License to Operate (SLO), an informal, often ongoing agreement between communities and mining companies that indicates community approval or rejection of a proposed mining project (Prno and Slocombe Citation2012). Some partner with transnational networks to increase awareness of mining activity and its negative social and environmental impacts (Paredes Citation2016). In other cases, communities lead protests against mining companies and governments, sometimes ending in violence or even death (Conde Citation2017; Flemmer and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2016; Muradian, Martinez-Alier, and Correa Citation2003; Triscritti Citation2013).

Indeed, these actions have increased community agency in decision-making. At the time of this study, proceeding with a mining project without engaging local communities is not advisable and can lead to conflict, loss of resources, and worse (Hodge Citation2014; Triscritti Citation2013). Even with these realities, many new and ongoing mining projects still neglect community concerns and at times even forgo gaining an SLO (Owen and Kemp Citation2013). Moreover, there remains a disconnect between the literature that critically questions efforts designed to cultivate equitable resource governance and many applied policy studies that analyze existing governance processes in mining development. Specifically, research that uses political-ecological or other critical approaches uses community perspectives, both empirically and conceptually, to guide analyses of conflict and governance in mining contexts. This literature has shown that power imbalances and negligence of community priorities, along with other factors like ineffective pollution control and remediation, continue to degrade the environment, jeopardize local livelihoods, increase inequalities within and across communities, and exacerbate local political and social conflicts (e.g., Anguelovski Citation2011; Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011; Muradian, Martinez-Alier, and Correa Citation2003; Triscritti Citation2013). Yet, while applied policy studies on natural resource governance in mining contexts argue for increased community participation, many have elected to largely focus on the analysis of corporate and government stakeholders, reviews of policy documents, or secondary analysis of community concerns (e.g., Franco and Ali Citation2017; Fraser and Kunz Citation2018; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2018, Citation2019). In fact, few applied policy studies focus on community perspectives or use community priorities to shape mechanisms for improving mining governance (e.g., Andrews and Essah Citation2020; Essah and Andrews Citation2016).

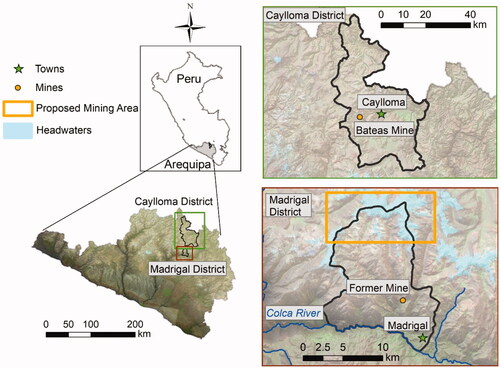

In this article, we begin to address gaps in the applied policy studies by documenting and analyzing community concerns through the lens of a “community-centered governance” framework that prioritizes community perspectives and works toward balancing power among stakeholders in decision-making (Andrews and Essah Citation2020; Armitage et al. Citation2020; Lockwood et al. Citation2010). Using this framework as a guide, this study asks: how do communities perceive and participate in governance in mining contexts? And what are some alternative ways, driven by community priorities, to address governance in mining contexts? We answer these questions by drawing on semi-structured interviews in two distinct agricultural districts, Caylloma and Madrigal, in the Department of Arequipa in Peru, and analyzing mining-specific governance mechanisms (i.e., mining canon, CSR policies, participation procedures) from community perspectives. Our contribution to the applied, natural resource policy literature on mining governance is to draw lessons from community members themselves, rather than analyzing data from corporate and government stakeholders or secondary sources. Our results show how prioritizing community perspectives in data collection can illuminate context-specific factors that shape a community’s perception and participation in governance and pinpoint approaches, driven by context, to address governance in mining development.

Challenges to Governance in Mining Development

Globally, it has been widely documented that decades of mining activity have contaminated water and soil and exhausted significant water resources, which also resulted in biodiversity loss and the changes in local water management systems (Sosa, Boelens, and Zwarteveen Citation2017; Vela-Almeida et al. Citation2016). In response to these impacts, communities around where mining activity has taken place have demanded, through protest and collaboration with transnational and local NGOs, that mining companies and governments take more responsibility to prevent and/or mitigate them (Conde Citation2017; Muradian, Martinez-Alier, and Correa Citation2003). In the early 1990s, countries like Peru and the Philippines also began to shift away from centralized, national policymaking to decentralized, multi-stakeholder governance with mining and other extractive industries (Adam et al. Citation2021; Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011; Verbrugge Citation2015). In a few cases, the shift improved policymaking and movements toward sustainable mining (Fraser Citation2021; Fraser and Kunz Citation2018). While in other cases, issues, such as power imbalances among stakeholders created inequitable outcomes, at times instigating conflict within communities and among stakeholders (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011; Jaskoski Citation2014).

Mining development also often takes place in the context of governmental institutions that lack effective processes for managing multi-stakeholder governance (Franco and Ali Citation2017; Cheshire Citation2010; Popovici et al. Citation2021). This creates obstacles to implementing effective arrangements for decentralized mining governance. For instance, Peru, Bolivia, Indonesia, Nigeria, and South Africa all created mining funds that redistribute mining revenues to subnational governments (in Peru, referred to as the mining canon). These countries use the funds to support infrastructure projects in town centers located close to mines through building schools, soccer stadiums, or hospitals. Despite these efforts, studies show that mining funds have fallen short of supporting local development. In Peru, corruption, clientelism, short-term political incentives for local authorities, and a lack of technical expertise and institutional knowledge among administrators have resulted in mismanagement of allocated funds, uneven distribution of benefits across communities, and in some cases, underspending of the allocated funds (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2019; Gamu and Dauvergne Citation2018). As a result, communities often experience the impacts of mining and the associated mining funds unevenly, become increasingly frustrated and distrustful, and lose confidence in existing mining governance arrangements (Bury Citation2004, Citation2005; Conde and Le Billon Citation2017).

In addition, in remote areas of Peru and Australia, CSR efforts act as surrogates to social programs implemented by regional, democratically elected institutions (Cheshire Citation2010; Triscritti Citation2013). In some cases, such CSR efforts, especially those that incorporate participatory mechanisms and tailor programs to address local needs, have generated some benefits by fostering community-driven socio-economic development (Franco and Ali Citation2017). However, this provisioning of social services can complicate governance by fostering paternalism between communities and companies and deepening power differences between them (Cheshire Citation2010). Other scholars argue that while CSR could have short-term positive impacts in communities, it is still embedded in extractive activities that ultimately legitimize capitalist projects that pollute the environment, disrupt local livelihoods, and are unable to “peacefully transform local resource politics” (Gamu and Dauvergne Citation2018 p. 960). Overreliance on CSR can also weaken the legitimacy of democratic institutions and create negative views on government performance (Konte and Vincent Citation2021). Because of these concerns, scholars posit that CSR can only support development if domestic policies are in place to effectively regulate CSR and mining activities (Andrews Citation2016; Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011; Triscritti Citation2013).

Moreover, most mining projects in countries like Peru, Australia, and the U.S. have now instituted multi-stakeholder dialogues where actors deliberate over various stages of mining development (Holley and Mitcham Citation2016; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2019; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2018; Rey-Coquais Citation2021). In some cases, dialogues, especially those that center local communities’ voices by prioritizing local concerns and needs, can create mutually beneficial outcomes for all parties involved (Franco and Ali Citation2017; Fraser Citation2021; Fraser and Kunz Citation2018). For instance, in the case of the Cerro Verde Mine in Arequipa, Peru, stakeholders held dialogues for three years until all parties agreed to a mutually beneficial outcome—the mining company built the city a much-needed wastewater plant and used the wastewater in its mining operations (Fraser Citation2021; Fraser and Kunz Citation2018). However, even though these dialogues support participation in mining development, many countries do not have laws to support equitable participation.

As evident in documented cases worldwide, communities generally do not have the legal authority to veto mining projects (Jaskoski Citation2014; Rey-Coquais Citation2021). Despite not having equal legal and procedural power when compared to companies and governments, communities often exercise their power by granting or vetoing the SLO. Some scholars describe the SLO as an industry standard, while others define it as a tool that communities use to practice their agency in mining governance (Prno and Slocombe Citation2012). No matter how it is described, mining companies are generally motivated to obtain an SLO. However, gaining an SLO often does not denote sustainable outcomes (Owen and Kemp Citation2013). In some cases, obtaining mutually beneficial, sustainable outcomes requires communities initially denying an SLO, which prompts companies to further address community priorities (Fraser and Kunz Citation2018). In other cases, companies gain the SLO through short-term dialogues with community elites, eliminating opportunities to gain input from diverse community actors or to create long-term, reciprocal relationships among stakeholders (Owen and Kemp Citation2013). Overall, scholars argue that an overemphasis on gaining the SLO in dialogues and mining development both causes more conflicts in the long term and prevents relationship building that could support more effective decision-making in mining contexts (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2019; Owen and Kemp Citation2013).

The literature suggests that community priorities should be at the forefront (Armitage et al. Citation2020), and “actors ought to be able to negotiate the management of mining projects and revenues as equal partners” (Triscritti Citation2013, 448). However, even though scholars are starting to recognize the value of community-centered governance in conservation programs and policy (see Armitage et al. Citation2020), few have applied this perspective in mining contexts. Moreover, many studies on mining policy and governance do not focus on the perspectives of the communities that are often most impacted by mining development, and many projects move forward without addressing community concerns or the inherent power imbalances among actors. In this paper, we center community voices by comparing mining governance in two cases in Peru and analyzing how the ways that mining-specific mechanisms, like CSR, dialogues, and procedural laws, prioritize or neglect community concerns. In what follows, we describe our research sites and design and discuss the results of community perceptions of mining governance across our two cases.

Research Design

Case Sites: Caylloma and Madrigal

The commercial center of the district of Caylloma () sits at 4,332 meters/14,212 ft above sea level and is home to ∼4,000 residents. Caylloma’s elevation is too high for crop farming, so pastoralism is the dominant agricultural livelihood strategy. Many residents have homes in the town center, but also spend time in annexes, which are large pieces of land of 150 acres or more where they herd between 100 and 500 alpacas, lambs, goats, and/or llamas. In lower elevations, some people also raise cattle. Caylloma is home to some of the oldest mines in Latin America, with an active mining history of ∼400 years (Pinto del Carpio Citation2020). National and international mining companies operate throughout the district, and multiple informal mines operate in or close to the district. However, the most prominent formal mine is the Caylloma Mine, owned and operated by Fortuna, a subsidiary of Minera Bateas, a Canadian mining company. The Caylloma Mine covers 36,312 hectares and extracts silver, gold, zinc, and lead, with future aspirations to mine for diamonds. This mining activity funds the mining canon as well as other community projects (Pinto del Carpio Citation2020). Many residents also work in informal mines, either as their primary livelihood strategy or to diversify their income sources.

Figure 1. Case study sites (Daneshvar et al. Citation2021).

With a population of around 600 and an elevation of 3,262 m/10,702 ft., the district of Madrigal primarily consists of small farms that grow a variety of crops, including corn, alfalfa, and potatoes, and raise cows and other livestock. While many indigenous people live in Madrigal, the district is not designated an indigenous community by the Peruvian government. Madrigal has a unique history of mining. The Madrigal Mine was located next to the town center from the 1970s until it abruptly closed in 1991. When the mine was operating, people in Madrigal engaged in both smallholder farming and economic activities that revolved around mining. Some worked in the mine, and those who did not work directly for the mine benefited economically through commercial activities, such as restaurants or selling services to miners. The closing of the mine impacted the town economically and environmentally. At the time of data collection in 2018, the Peruvian mining company Buenaventura had plans to construct the Mayra mine, a gold mine in K’ana K’ana (northern part of the district, elevation ∼4500 m/15,000 ft). It was planned to be located at the headwaters of the Palco River, which provides domestic and irrigation water for the nearby districts of Madrigal, Lari, Ichupampa, and Corporaque. Buenaventura applied for a permit from the Peruvian Ministry of Energy and Mines to conduct exploratory extractive studies to see if there were mining reserves. However, exploratory extraction started without Buenaventura consulting with the local community. At the time of our study, the construction of the Mayra mine was halted.

Research Methods

We used a multi-case embedded approach (Yin Citation2013) to study how two distinct communities attempted to use governance mechanisms to address their concerns with mining companies. To choose study sites, we used “replication logic,” defined by Yin (Citation2013) as “the selection of two or more cases… because the cases are predicted to produce similar findings” (p. 239). We chose our sites because both are situated in the same Province, had access to the same governance mechanisms, were subject to the same laws, and were experiencing mining conflicts at the time of this study. The two districts also differed in that they were in various stages of mining development, with Madrigal experiencing conflict in the face of a new mining project and Caylloma engaging in long-term mining development. Despite these differences, the two cases were predicted to produce similar findings because mining policies and governance mechanisms were consistent across cases. The comparative method allowed us to compare and contrast these two cases, offer insights into both contexts, and demonstrate what issues inhibited effective governance.

We used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling to collect data from a diversity of actors (Neuman Citation2009). Specifically, in 2018, we conducted 24 semi-structured interviews with 29 people, including farmers, community leaders, and authorities in Madrigal, and 29 semi-structured interviews with 56 alpaca and llama herders, ranchers, community leaders, authorities, and a community relations expert from a mining company in Caylloma. The majority of the interviews were conducted in Spanish; however, several research participants spoke Quechua, and in those situations a translator supported fieldwork. During interviews, we aimed to document how community members perceived the mining development process and their capacity to address their concerns. In particular, we asked community members to identify their community’s most prominent problems and describe their opinions of mining activity, the mining cannon, and dialogues.

For intercoder reliability, the lead author and two coauthors collectively edited the coding framework in four separate meetings and coded 10% of the transcripts before deciding on a codebook (Campbell et al. Citation2013; Church, Dunn, and Prokopy Citation2019). Coauthors stopped the reliability processes when they met a kappa coefficient higher than 0.7. The lead author then used Nvivo to code and organize the data into themes and used direct content and thematic analysis to interpret how people perceived governance in each district (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). The analysis concluded by connecting results that emerged during thematic analysis, interpreting the results in relation to the scholarly literature, and identifying quotations that were examples of those linkages.

Results: Community Perspectives of Mining Development and Governance

In this section, we document how people perceived mining development within each district. We then describe how people perceived governance mechanisms, such as the mining canon, dialogues, and CSR programs. We also describe how both communities resorted to protest because their district's governance arrangements did not adequately address the issues they were facing.

Caylloma

Dust, Lack of Employment in Mining, and Water Pollution

In Caylloma, interviewees were concerned about dust from mining trucks, a lack of employment opportunities in the mine, and water pollution from mining activity. Many interviewees told us that mining trucks created dust that polluted their pastures. One pastoralist in Caylloma explained this as follows: “There’s a lot of pollution, which impacts our animals, especially when there are a lot of cars and the dust from the cars pollutes the grass.” Many interviewees believed that the dust made their animals sick, as one person explained: “We get a lot of dust pollution. The rain will clean the dust but if there’s no rain, the animals cough a lot.”

In addition to dust issues, interviewees informed us that the mining companies would often promise to employ local people, but they hired workers from elsewhere. One local school leader described this as:

“There’s an agreement between the municipality and the mining company that states that professionals from Caylloma get preferential treatment. When there are no more professionals from here, they can bring in people from other places, but that’s only in writing. In reality, they only bring in people from other towns. They say [local] people don’t know how to work, they haven’t studied, and they’re not trained.”

One authority from Caylloma further confirmed this perception by stating: “The big companies bring in their own workers from other parts of the country like Cusco, Chumbivilcas, and Puno, so we continue to dedicate our livelihoods to raising alpacas.”

Interviewees also told us that mines impact water quality and quantity, which negatively affected the grass that their alpacas ate: “The grass has really decreased because there isn’t much water. The mine diverts the water, the springs have dried up, and there’s no longer green grass. It’s just dry grass.” Another pastoralist explained this in more detail as follows: “Before there wasn’t much mining and the rivers had fish, there were frogs and toads, but now, there’s nothing. They all disappeared when they started the work in the mines.”

The Community Wanted a New Road and a Mining Institute

In relation to these concerns, interviewees wanted the mine to pave the road and create an institute to train youth to work in the formal mines. In particular, interviewees informed us that they wanted a new asphalt road, as one person explained: “We want an asphalt road and the authorities to help us draw out water to irrigate our pastures to improve our natural pastures and economy.” Other interviewees told us that they wanted opportunities for young people to work in the formal mines. One authority explained this as follows: “It would be great if the majority of the workers in formal mines were from Caylloma, but this isn’t happening… They should have a chance to work in the formal mines, but the companies only bring people from outside.” Another pastoralist expressed a similar desire: “We don’t have an institute in Caylloma. Because of this, young people who finish high school work in informal mines as day laborers. We need an institute so that they can study, work as professionals, and have a better income.”

Many Community Members Felt Neglected by the Mining Company

Interviewees identified several mechanisms used by the mining company to address community concerns, including dialogues, the mining canon, and CSR programs. Many interviewees also told us that they expressed their concerns to the mine directly, but the mine did not listen. One pastoralist described this as follows: “They don’t listen to us, they only spray down the dust in some areas. Afterwards, it goes back to normal.” Another explained this as: “There’s not much help from the mining companies. They’ve had meetings, but they don’t listen.” Interviewees also expressed that they were confused about how to request help, as one pastoralist explained:

“We need tubes [for irrigation], but we don’t know which institutions to turn to. We’ve asked the mining companies, but they don’t want to support us. The regional government also won’t support us. The information they give us is an insult. We no longer trust anyone.”

The mining canon was also a point of tension. In Caylloma, the mining canon was distributed to the district municipality and then dispersed at the mayor's discretion. One leader described this relationship as follows: “The district gets funds from the mining canon, but our annex doesn’t. The mining companies support the annexes but indirectly. Decisions made on the distribution of funds rest in the hand of the district municipality, the mayor.” Because the mining canon funds were distributed this way, some interviewees did not see the impact of these funds and wanted more direct support. As one pastoralist explained: “The people always ask the mine for help, but the mining companies say that they already help by paying into the mining canon.”

The mining company had recently implemented CSR programs where they supported pastoralists through capacity building. A mining representative explained that they implemented the CSR programs because the mining canon neglects rural populations. He explained this as follows:

“We do this as part of our social responsibility, but it’s also due to the people’s demand. The mine makes their contribution to the mining canon, but in many cases, the funds are channeled to other areas, not to livestock. Infrastructure is built in town, but 95% of the population is dedicated to pastoralism, so they’re neglected.”

He also informed us that he and his colleagues from the mining company had elicited input from community members through a workshop. He explained the process as: “a workshop and afterwards we learned about their needs, like dosages of parasitic medicines.. The pastoralists learned how to administer the medicines.” Some interviewees perceived the CSR programs as helpful. A pastoralist explained the project as follows: “Now, the mine is helping us… In general, you could say that the support is good, but in the end, they’re taking our wealth and should support us.” There was also a shared sentiment that the mining company could and should do more for the local community.

Community Members Used Protests to Address Their Concerns and Priorities

Because community members felt that the mining company and the government had largely neglected their concerns and needs, many resorted to protests. A teacher described this as follows:

“This year, there have been two intense protests, one due to non-compliance of agreements and another due to not asphalting the road… The mining company takes the town’s resources and leaves nothing in return. It’s chaos. That’s why they went out to protest. Because of the protests, many things have been achieved, such as improving the road, which is being carried out… If there were no protests, nothing would happen, and the companies would just operate as usual. The protests are good.”

Even though most community members supported the protests, some were hesitant in their support. One pastoralist explained this as follows: “This year, there was a protest and now the mine’s paying 5 million soles. It is a form of support, but it was implemented by force.” Similarly, another pastoralist explained to us that the protests were contentious: “When we protest, they also bring police, and they don’t allow us to claim our rights.”

Madrigal

Pollution from a Former Mine and Potential Threats to Headwaters

In Madrigal, interviewees were still dealing with runoff from a former mine while being concerned about the potential ramifications of a proposed mine on their water supply. One authority explained this as: “Two mining companies are attacking us. The current company and the former one.” In particular, interviewees were troubled by the runoff from the former mine and the proposed mine’s threat to their water supply, and a lack of engagement with Madrigal's community.

For example, many interviewees told us that farm plots next to the former mine were polluted. One widow of a miner and farmer in Madrigal shared: “They left us with runoff, so it no longer produces, no corn, no potatoes, no barley, nothing… That damn company… They told us, ‘we are going to fix it, we are going to fix it’, but they never did.” Another farmer described her experience similarly. She said: “We had a lot of farms that were close to the old mine, and it impacted us so much that people had to move away and abandon those farms.”

Interviewees also told us that they were scared that the new mine would pollute their headwaters. When we asked an authority his opinion about the biggest challenge facing the district, he said: “The problem with the mine… If it comes here, it will pollute our water. It’s in our headwaters.” A farmer interviewee confirmed this concern by stating:

“The mine wants to come, and we don't want it. They’ll pollute our water. The water comes from a spring, and from that spring, we irrigate. Many of our farms were destroyed from the old mine. We had a large farm next to the older mine, and it’s ruined. We've been screwed. The mine didn't buy the farms back from us, either.”

Others were concerned that the new mine was a short-term economic solution that would leave the district with nothing after it closes. One farmer explained this as: “In ten years, this place will be a desert. You will no longer see plants… It’s not right.” One farmer and temporary government worker explained her concern about the short-term nature of mines as well:

“The mine will move the mountains, and that’s where the water is. So, each time they move the mountains, another drop of water is lost… Afterward, what water are we going to have? Of course, the mine will be welcomed now. There may be jobs all over the place, but what will happen in the long term? We cannot just think about ourselves. We have to think about our children and grandchildren… After a while, there’ll be just a little bit of green, and as time goes by, it’ll all be desert. Of course, there’ll be progress, but what will happen later? Once the mine closes, they’ll leave happy, but what about those of us who live here? We’re the ones who are going to suffer. We won’t have anything.”

Several interviewees also discussed alternative development opportunities to mining. One farmer and local business owner preferred that the community focus on tourism instead of mining. He explained this as follows:

“The mine is a passer-byer. There was a mining company here, 30 years ago. As you have probably seen, they’ve left… I think that tourism could be permanent… I think we should bet on tourism.”

Some Community Members Supported While Others Objected to the Proposed Mine

Even though some community members expressed conditional support for the proposed mine, others were entirely opposed no matter the opportunities the proposed mine could bring. In terms of the former, several interviewees discussed how they wanted the proposed mine to halt all exploratory extraction and planning activities until it made an agreement with the community and supported local development. As one organizational leader explained: “The mine could come here with no problem, but there has to be an agreement between the farmers and the mine.” Another farmer and local business owner told us: “I would even say yes to the mine, but they have to follow the law. They could help us improve education and our animals, including cattle, sheep, and maybe even alpacas. The mining company could also help us find a market.” An additional farmer echoed this conditional support as follows: “We want a responsible mine that does what the state asks. This would be great, but if the mine is not responsible, it will destroy us, just like other mines.” However, based on their previous experience with mining companies, many interviewees were not confident that an agreement between the mining company and the agricultural community would be possible. As one farmer explained: “The mining company has to support ranchers, education, health, but they’re not interested. For them, it doesn’t matter.”

While some community members were conditionally supportive of the proposed mine, many other interviewees did not want the mine to operate at all. An exact percentage was unknown due to the qualitative nature of our study; however, one local authority estimated that “80% of the population doesn’t want the mine.” Interviewees’ objection was mostly because they doubted that the mine could operate without polluting their headwaters. Even community members who benefited from the former mine rejected the proposed mine. One leader and former mine worker in the Madrigal mine said: “No, because it will ruin our headwaters. Right now, the water is already polluted. It is turning blue… People don’t want it, period.” Another farmer spoke about the pollution that the former mine had left and said: “Everything you see here has already been ruined. Now a mine wants to come back!? We will never let them in again.”

Former Laws Neglected Community Concerns and the Proposed Mine Did Not Seek Community Participation

In Madrigal, people told us that laws neglected people and did not prevent pollution when the former mine was in operation. One authority described this as: “In the 80 s and 90 s, there were almost no mining laws that favored agriculture. There was no environmental impact assessment. The Madrigal Mine did their best, but they left runoff that’s still here to this day.” Because laws were not in place, the land was damaged, and only some people were compensated for their losses from the runoff. Many shared the same frustration as one farmer interviewee explained: “They completely ruined my land… They didn’t compensate us for any of the damages.”

Regarding the proposed mine, interviewees told us that the mine already started exploratory extraction without soliciting input from the local community. An authority described this as follows: “Of course, we knew they had the intention, but they began working without communicating with local authorities or local people.” One farmer described this as: “Right now, the mine’s here, but without asking the town for permission. It has already started extracting.” In addition to being upset by this, interviewees told us that this violated Peruvian laws. In particular, they informed us that the Ministry of Energy and Mines and the National Water Authority, both national agencies that approve mining projects, had signed an agreement with the proposed mine, but they neglected to solicit input from the local community before starting exploratory extractions, which is required by law in Peru (Supplement A). One authority expressed that because of this, community members renounced the mine. He said: “The majority of the people here don’t want the mine because the mine hasn’t had a dialogue. In whatever way, there has to be a dialogue to discuss environmental problems, pollution, and people’s land.”

Some interviewees also told us that the mining company and government agencies did hold a dialogue, but only after the mining company had started exploratory extraction. Several interviewees told us specifically that they learned of mining activity when people from Madrigal and neighboring towns also affected by the proposed mine met with mining representatives and government agencies to discuss the project. They thought they were meeting to discuss the proposal; however, they realized that the mining company had already started exploratory extraction when they met. Many interviewees perceived this as deception, as one farmer explained: “They came to give us a dialogue. They wanted to surprise us, but then we realized what they were doing.” Another farmer explained that the mining company held the dialogue only to elicit information about possible CSR projects, not an SLO. He said: “They told us: ‘we’re going to start on Tuesday. What do you want from us?’ We told them that we want nothing. ‘You have deceived us way too much. Go away!’”

Community Members Addressed Their Concerns through Protests and Legal Measures

In the end, many community members perceived the lack of consultation and respectful dialogues with the mining company as an encroachment on their rights, as one authority told us: “The townspeople say: ‘Even the humblest of towns has rights, and those rights have been violated.’” Many interviewees shared with us that they declared their rights at a dialogue held by the mining company and united with authorities and other towns to protest against the mine. In fact, during the dialogue process, the mining company attempted to convince some local people to support the mine, but it did not work. A farmer described this event as follows:

“At some point some people wanted the mine; however, then people who actually understood mining came to the dialogue. They asked: ‘How are you going to give authorization to them? They’re going to pollute the water, and we make our living from agriculture.’ After that, the mine was out.”

It is also worth noting that several protests took place in Arequipa, the departmental capital. As one interviewee told us: “We were upset and had a meeting. It was there we learned they’d started without our permission. Because of this, we protested.” When asked why people went to Arequipa to protest, this interviewee said: “so they’ll listen to us faster.” Another farmer interviewee told us that the people from Madrigal united with other districts. He said: “We’re fighting against the company, together with the government authorities.” An authority from Madrigal further elaborated on this collective effort and told us: “Practically all the right side of the river [Rio Colca] is united against the mine, [districts of Lari, Madrigal, Ichupampa].”

Because of these efforts, the mining company halted its exploratory extraction. Specifically, an authority from Madrigal described that the company had been “paralyzed.” In addition to being paralyzed, the company had to pay a hefty fine for violating the community’s rights and not following laws requiring community participation in mining development. An authority described this as follows: “The mine was sanctioned. It owes the state a fine. It’s a lot of money. I really don’t know if it will be able to pay it and reopen.” Another authority explained this as follows: “This is why the town has risen up together. Now, the company has suffered a bit… Why? Because of their bad behavior! The mine will be fine. They have money.” Even though the actions taken by local communities had succeeded, some had concerns that the mine could return, as one younger farmer interviewee described: “They stopped, but if they start again, we’re ready to fight.”

Discussion: Community-Driven Approaches to Mining Governance

Results show how centering community voices can reveal context-specific mechanisms for addressing governance concerns in diverse mining communities, like the districts of Madrigal and Caylloma. In particular, insight from community members in two distinct districts shows that local livelihoods and historical contexts can shape how communities perceive mining. Like in other studies ( Armah et al. Citation2011 ; Vela-Almeida et al. Citation2016), community members from both sites continued to experience pollution from mining, including dust and water pollution. However, most interviewees in Caylloma did not want the mine to close. As in other Peruvian communities with mining (Malone, Smith, and Zeballos Citation2021), many interviewees partially relied on the mine for their livelihoods and some self-identified as both miners and pastoralists. On the contrary, Madrigal’s interviewees’ concerns about pollution directly contributed to their disapproval of the new mining project. Overall, a community’s historical relationship with a mine, the extent to which community members depend on the mine for their livelihoods, and their physical proximity to the mine can shape their perceptions of mining (Conde and Le Billon Citation2017; Dagvadorj, Byamba, and Ishikawa Citation2018; Triscritti Citation2013).

In particular, prior knowledge of Madrigal’s adverse mining history could have cautioned the mining company before pursuing the development of a new mine. In fact, in Peru, proposed mining projects in headwaters, like the one in Madrigal, are usually denied an SLO (Jaskoski Citation2014; Triscritti Citation2013). In Caylloma, however, the historical presence of mining and the complex livelihoods and corresponding intersectional identities of many pastoralists (Erwin et al. Citation2021) created more common ground. For this reason, working together to identify community-driven, mining-supported development outcomes is likely more plausible in Caylloma than in Madrigal. Together, our results highlight a need for community-centered governance, that is, placing local livelihoods, historical contexts, and community dynamics at the forefront to effectively engage community participation and facilitate effective governance.

Similarly, data suggest that distributing funds from the mining canon to rural areas could more adequately address the priorities of people living in rural, agricultural communities in mining contexts. For instance, the Peruvian government implemented the mining canon so subnational governments could have more resources to address community priorities (Supplement A). However, subnational governments may have priorities that do not align with local needs. Even at the local level, decision-makers may prioritize some desires from their communities over others. This was evident in the case of Caylloma where rural pastoralists wanted an asphalt road, but municipal leaders used the mining canon to stimulate development in the town center. In this case, rural pastoralists were displeased because their concerns and priorities were neglected, and the mining company was dissatisfied because they felt they already paid their dues. Other studies have similarly shown how funds from the mining canon often fail to adequately address rural priorities (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011, Citation2019). These findings point to nuances with increasing public participation in decision-making. Particularly, democratically elected officials often have more incentive to adhere to the majority’s desires. Peruvian town centers generally have higher populations, thus, are more likely to benefit from the mining canon. However, town centers rarely experience the same magnitude of mining impacts as populated rural communities (Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011, Citation2019). Our results indicate that reallocating funding to rural areas that are affected by the mine to specifically address local problems and needs could improve perceived fairness and development opportunities in those areas. In places like Caylloma, one option could be to distribute a portion of the funds to elected presidents of annexes where pastoralists reside instead of distributing all the funds to the municipality in town.

Furthermore, community perspectives provide further evidence that supports what has been shown in some studies about CSR and its related initiatives. First, CSR programs are increasingly used by mining companies to address opposition toward negative impacts of mining, engage with communities, and gain their support (Conde Citation2017). Second, communities may have a broader perspective of CSR than mining companies (Mzembe and Downs Citation2014). Indeed, in Caylloma, many community members wanted opportunities to work in the mine and desired a mining institute to train youth to work in formal mines. Yet, the CSR programs focused on small, dispersed projects that trained pastoralists, for example, programs that teach pastoralists about antibiotics for their herds. Even though the mine discussed CSR ideas with communities, the projects they implemented did not address the longer-term priorities of most pastoralists we interviewed. As Devenin and Bianchi (Citation2018) pointed out, CSR programs often fail when they do not contribute to long-term community priorities. Our findings suggest that educational and employment opportunities could be essential for community development along with shorter-term projects. In this study, we did not have sufficient data to further analyze how power shapes the development and implementation of CSR programs. However, it is crucial to keep in mind that extractive industries use CSR programs as a risk management tool (Frederiksen Citation2019; McLennan and Banks Citation2019). They often aim to address the priorities of “those with the greatest capacity to disrupt operations rather than those with the greatest need” (Frederiksen Citation2019, 168). This should be an important topic for future research.

Perceptions of community members align with other studies showing that participatory processes, such as dialogues and processes for informed consent between community members and mining companies, need to be community-driven, transparent, fair, and sincere (Flemmer and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2016; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2018, Citation2019). In both Caylloma and Madrigal, community members participated in dialogues with the mining companies, but they did not feel respected in these spaces. In Madrigal, when the mining company held a dialogue, community members felt that it was not for addressing their needs and concerns; rather, interviewees felt that the mining company had predetermined goals, including informing the community of their operations as if the mine were already moving forward, and they felt that the dialogue was solely for the purpose of gaining their approval to proceed (i.e., SLO). In particular, community members perceived that the dialogue was manipulative and disrespectful, and they protested because, from their perspectives, the mining company did not genuinely consult them.

On paper, Peruvian laws require community participation before a new mining project begins and throughout the life of the mine (Supplement A). However, the laws do not grant communities the power to create dialogue agendas or legally veto a proposed project (Flemmer and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2016; Rey-Coquais, S. 2020). Because there are no set details on what community participation entails, the decision about if and how community concerns will be addressed rests in the goodwill of the Ministry of Energy and Mines. Like what was shown in our study, a lack of accountability can spark resistance on the part of communities, reduce the likelihood of recourse, and decrease community trust in dialogues (Anguelovski Citation2011; Armah et al. 2011; Vela-Almeida et al. Citation2016). Indeed, many mining projects across Peru, including those from Conga, Tambomayo, Tintaya, and Rio Blanco, also experienced widespread resistance from communities because of a lack of transparency, mutual respect, and perceived fairness in decision-making processes (Anguelovski Citation2011; Arellano-Yanguas Citation2011, Citation2019; Bebbington et al. Citation2008; Gamu and Dauvergne Citation2018; Jaskoski Citation2014; Muradian, Martinez-Alier, and Correa Citation2003; Toledo Orozco and Veiga Citation2018). In addition, theories of participatory justice suggest that dialogues alone will not sufficiently support those who participate unless participant priorities are tied to actions (Fraser Citation2009). As such, our results, along with previous studies, suggest that dialogues developed to discuss and support local needs and priorities, instead of dialogues organized to inform communities of mining companies’ plans or for the sole purpose of gaining SLOs from communities, could facilitate long-term relationship building among stakeholders, something that may support more effective decision-making over time ( Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2018; Owen and Kemp Citation2013). At the same time, our results highlight the need for legal arrangements that give communities power and enforce accountability for addressing local needs and priorities discussed during dialogues. Furthermore, most Peruvian laws focus on participation at the beginning stages of mining development, particularly during the EIA process (Supplement A). Our findings from Caylloma highlight the need for more robust, clear laws that support community participation throughout the life of a mine.

Finally, results align with other studies in Peru and indicate that dismissing community agency before proceeding with mining operations could cost communities, mining companies, and governments significant resources (Triscritti Citation2013). For instance, in Madrigal, interviewees used the law in their favor to demonstrate how the mining company did not allow for community participation before starting exploratory extraction. They also used protests to raise awareness of their case. In the end, the community and local government spent significant time and energy working through the conflict, and the mining company was fined and stopped its exploratory extraction in response to these efforts. In Caylloma, community members used protests to address their desires for an asphalt road, a need that was previously raised through dialogues but neglected. While the road had not been built at the time of our interviews, interviewees reported that a road had been promised to them and would be built soon. Our results provide further evidence that supports trends observed across several studies. Particularly, while mining development and pollution are increasing globally, communities continue to exercise agency in mining deliberations (Hodge Citation2014; Paredes Citation2016).

Conclusions

This study provides insight into how to address mining governance from community perspectives, a view that contributes to the natural resource policy literature. Our analyses of community members’ perceptions of mining companies, governments, and community relations yielded three key insights. First, open dialogues at different stages of mining development where communities control the agenda could create more productive relationships among stakeholders than dialogues staged by mining companies with the primary goal of gaining an SLO (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2018). Second, funds from the mining canon and CSR programs need to adapt to adequately support rural communities in mining contexts. Lastly, our results call for additional attention to the laws that uphold power imbalances in mining decision-making. For instance, across the world, the shift from government to governance encouraged opportunities for public participation and informed consent in natural resource management (Flemmer and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2016; Larson and Soto Citation2008; Lockwood et al. Citation2010). However, existing laws continue to give more power to decision-makers like government officials than communities, thereby reinforcing existing power imbalances and further excluding those with less power (Frederiksen Citation2019; Larson and Soto Citation2008). Future research on how diverse communities perceive governance in mining contexts could highlight more ways in which these dynamics play out on the ground and provide additional insight into how to address governance in mining contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank our research participants in the districts of Caylloma and Madrigal and the Purdue University Center for the Environment.

Disclosure statement

All coauthors of this manuscript have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, J. N., T. Adams, J.-D. Gerber, and T. Haller. 2021. Decentralization for increased sustainability in natural resource management? Two cautionary cases from Ghana. Sustainability 13 (12):6885. doi:10.3390/su13126885.

- Andrews, N. 2016. Challenges of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in domestic settings: An exploration of mining regulation vis-à-vis CSR in Ghana. Resources Policy 47:9–17. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2015.11.001.

- Andrews, N., and M. Essah. 2020. The sustainable development conundrum in gold mining: Exploring ‘Open, Prior and Independent Deliberate Discussion’ as a community-centered framework. Resources Policy 68:101798. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101798.

- Anguelovski, I. 2011. Understanding the dynamics of community engagement of corporations in communities: The Iterative relationship between dialogue processes and local protest at the Tintaya Copper Mine in Peru. Society & Natural Resources 24 (4):384–99. doi:10.1080/08941920903339699.

- Arellano-Yanguas, J. 2011. Aggravating the resource curse: Decentralisation, mining and conflict in Peru. Journal of Development Studies 47 (4):617–38. doi:10.1080/00220381003706478.

- Arellano-Yanguas, J. 2019. Extractive industries and regional development: Lessons from Peru on the limitations of revenue devolution to producing regions. Regional & Federal Studies 29 (2):249–73. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1493461.

- Aresti, M. L. 2016. Mineral revenue sharing in Peru. Revenue Sharing Case Study. Natural Resource Governance Institute. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/mineral-revenue-sharing-in-peru_0.pdf.

- Armah, F. A., S. Obiri, D. O. Yawson, E. K. Afrifa, G. T. Yengoh, J. A. Olsson, and J. O. Odoi. 2011. Assessment of legal framework for corporate environmental behaviour and perceptions of residents in mining communities in Ghana. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 54 (2):193–209. doi:10.1080/09640568.2010.505818.

- Armitage, D., P. Mbatha, E. K. Muhl, W. Rice, and M. Sowman. 2020. Governance principles for community‐centered conservation in the post‐2020 global biodiversity framework. Conservation Science and Practice 2 (2):e160. doi:10.1111/csp2.160.

- Bebbington, A., L. Hinojosa, D. H. Bebbington, M. L. Burneo, and X. Warnaars. 2008. Contention and ambiguity: Mining and the possibilities of development. Development and Change 39 (6):887–914. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00517.x.

- Bury, J. 2004. Livelihoods in transition: Transnational gold mining operations and local change in Cajamarca, Peru. The Geographical Journal 170 (1):78–91. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2004.05042.x.

- Bury, J. 2005. Mining mountains: Neoliberalism, land tenure, livelihoods, and the new Peruvian mining industry in Cajamarca. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 37 (2):221–39. doi:10.1068/a371.

- Campbell, J. L., C. Quincy, J. Osserman, and O. K. Pedersen. 2013. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research 42 (3):294–320. doi:10.1177/0049124113500475.

- Cheshire, L. 2010. A corporate responsibility? The constitution of fly-in, fly-out mining companies as governance partners in remote, mine-affected localities. Journal of Rural Studies 26 (1):12–20. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.06.005.

- Church, S., M. Dunn, and L. Prokopy. 2019. Benefits to qualitative data quality with multiple coders: Two case studies in multi-coder data analysis. Journal of Rural Social Sciences 1:2. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol34/iss1/2/.

- Conde, M. 2017. Resistance to mining. A review. Ecological Economics 132:80–90. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.025.

- Conde, M., and P. Le Billon. 2017. Why do some communities resist mining projects while others do not? The Extractive Industries and Society 4 (3):681–97. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2017.04.009.

- Dagvadorj, L., B. Byamba, and M. Ishikawa. 2018. Effect of local community’s environmental perception on trust in a mining company: A case study in Mongolia. Sustainability 10 (3):614–2. doi:10.3390/su10030614.

- Daneshvar, F., J. Frankenberger, K. Cherkauer, H. Novoa, and L. Bowling. 2021. Hydrological assessment of interconnected river basins in semi-arid region of Peruvian Andes. Earth and Space Science Open Archive. doi:10.1002/essoar.10506222.1.

- Devenin, V., and C. Bianchi. 2018. Soccer fields? What for? Effectiveness of corporate social responsibility initiatives in the mining industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25 (5):866–79. doi:10.1002/csr.1503.

- Erwin, A., Z. Ma, R. Popovici, E. P. Salas O'Brien, L. Zanotti, E. Zeballos Zeballos, J. Bauchet, N. Ramirez Calderón, and G. R. Arce Larrea. 2021. Intersectionality shapes adaptation to social-ecological change. World Development 138:105282. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105282.

- Essah, M., and N. Andrews. 2016. Linking or de-linking sustainable mining practices and corporate social responsibility? Insights from Ghana. Resources Policy 50:75–85. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2016.08.008.

- Flemmer, R., and A. Schilling-Vacaflor. 2016. Unfulfilled promises of the consultation approach: the limits to effective indigenous participation in Bolivia’s and Peru’s extractive industries. Third World Quarterly 37 (1):172–88. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1092867.

- Franco, I. B., and S. Ali. 2017. Decentralization, corporate community development and resource governance: A comparative analysis of two mining regions in Colombia. The Extractive Industries and Society 4 (1):111–9. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2016.12.001.

- Fraser, J. 2021. Mining companies and communities: Collaborative approaches to reduce social risk and advance sustainable development. Resources Policy 74:101144. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.02.003.

- Fraser, N. 2009. Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Fraser, J., and N. C. Kunz. 2018. Water stewardship: Attributes of collaborative partnerships between mining companies and communities. Water 10 (8):1081. doi:10.3390/w10081081.

- Frederiksen, T. 2019. Political settlements, the mining industry and corporate social responsibility in developing countries. The Extractive Industries and Society 6 (1):162–70. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2018.07.007.

- Gamu, J. K., and P. Dauvergne. 2018. The slow violence of corporate social responsibility: The case of mining in Peru. Third World Quarterly 39 (5):959–75. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1432349.

- Hodge, R. A. 2014. Mining company performance and community conflict: Moving beyond a seeming paradox. Journal of Cleaner Production 84 (1):27–33. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.007.

- Holley, E., and C. Mitcham. 2016. The Pebble Mine Dialogue: A case study in public engagement and the social license to operate. Resources Policy 47:18–27. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2015.11.002.

- Hsieh, H. F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15 (9):1277–88. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jaskoski, M. 2014. Environmental licensing and conflict in Peru’s mining sector: A path-dependent analysis. World Development 64:873–83. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.07.010.

- Konte, M., and R. C. Vincent. 2021. Mining and quality of public services: The role of local governance and decentralization. World Development 140:105350. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105350.

- Larson, A. M., and F. Soto. 2008. Decentralization of natural resource governance regimes. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 33 (1):213–39. doi:10.1146/annurev.environ.33.020607.095522.

- Lockwood, M., J. Davidson, A. Curtis, E. Stratford, and R. Griffith. 2010. Governance principles for natural resource management. Society & Natural Resources 23 (10):986–1001. doi:10.1080/08941920802178214.

- Malone, A., N. M. Smith, and E. Z. Zeballos. 2021. Coexistence and conflict between artisanal mining, fishing, and farming in a Peruvian boomtown. Geoforum 120:142–54. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.012.

- McLennan, S., and G. Banks. 2019. Reversing the lens: Why corporate social responsibility is not community development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26 (1):117–26. doi:10.1002/csr.1664.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., W. Rifkin, W. Louis, and K. Moffat. 2019. Power, participation, and exclusion through dialogue in the extractive industries: Who gets a seat at the table? Resources Policy 61:190–9. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.11.023.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L. D., W. Rifkin, K. Moffat, and W. Louis. 2018. What makes stakeholder engagement in social licence “meaningful”? Practitioners’ conceptualisations of dialogue. Rural Society 27 (1):1–17. doi:10.1080/10371656.2018.1446301.

- Muradian, R., J. Martinez-Alier, and H. Correa. 2003. International capital versus local population: The environmental conflict of the Tambogrande Mining Project, Peru. Society & Natural Resources 16 (9):775–92. doi:10.1080/08941920309166.

- Mzembe, A. N., and Y. Downs. 2014. Managerial and stakeholder perceptions of an Africa-based multinational mining company’s corporate social responsibility (CSR). The Extractive Industries and Society 1 (2):225–36. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2014.06.002.

- Neuman, L. 2009. Social science research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 7th ed. Pearson.

- Owen, J. R., and D. Kemp. 2013. Social licence and mining: A critical perspective. Resources Policy 38 (1):29–35. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.06.016.

- Paredes, M. 2016. The glocalization of mining conflict: Cases from Peru. The Extractive Industries and Society 3 (4):1046–57. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2016.08.007.

- Pinto del Carpio, P. M. 2020. Gobernanza de recursos naturales y conflicto social: El caso de minera bateas, caylloma-perú 2005–2018. Thesis. Universidad Nacional de San Agustín deArequipa.

- Popovici, R., A. Erwin, Z. Ma, L. Prokopy, L. Zanotti, E. F. Bocardo Delgado, J. P. Pinto Cáceres, E. Zeballos Zeballos, E. P. Salas O’brien, L. Bowling, et al. 2021. Outsourcing governance in Peru’s integrated water resources management. Land Use Policy 101:105105. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105105.

- Prno, J., and D. S. Slocombe. 2012. Exploring the origins of 'social license to operate in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resources Policy 37 (3):346–57. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002.

- Rey-Coquais, S. 2021. Territorial experience and the making of global norms: How the Quellaveco dialogue roundtable changed the game of mining regulation in Peru. The Extractive Industries and Society 8 (1):55–63. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2020.05.002.

- Sosa, M., R. Boelens, and M. Zwarteveen. 2017. The influence of large mining: Restructuring water rights among rural communities in Apurimac, Peru. Human Organization 76 (3):215–26. doi:10.17730/0018-7259.76.3.215.

- The World Bank. 2005. Wealth and sustainability: The environmental and social dimensions of the mining sector in Peru. Peru Country Management Unit, Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development, Latin America and the Caribbean Region, The World Bank, 194. http://icsidfiles.worldbank.org/icsid/icsidblobs/onlineawards/C3004/C-032_Eng.pdf

- Toledo Orozco, Z., and M. Veiga. 2018. Locals’ attitudes toward artisanal and large-scale mining—A case study of Tambogrande. The Extractive Industries and Society 5 (2):327–34. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2018.01.002.

- Triscritti, F. 2013. Mining, development and corporate-community conflicts in Peru. Community Development Journal 48 (3):437–50. doi:10.1093/cdj/bst024.

- Vela-Almeida, D., F. Kuijk, G. Wyseure, and N. Kosoy. 2016. Lessons from Yanacocha: Assessing mining impacts on hydrological systems and water distribution in the Cajamarca region, Peru. Water International 41 (3):426–46. doi:10.1080/02508060.2016.1159077.

- Verbrugge, B. 2015. Decentralization, institutional ambiguity, and mineral resource conflict in Mindanao, Philippines. World Development 67:449–60. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.007.

- Yin, R. K. 2013. Case study research: Design and methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.