Abstract

Conservation for and with local communities and stakeholders is essential. Despite the importance of community-oriented approaches and calls for capacity building in conservation, the impacts and inputs of training in relational fields like collaborative conservation remain unclear. We used mixed methods to conduct one of the first evaluations of a collaborative conservation capacity building program, and present an empirically-based causal model of the programmatic inputs supporting long-term changes. We found moderate to transformational impacts on participants’ practice and professional trajectories, and on multiple dimensions of capacity, including comfort, conviction, and identity. Flexible funding, immersion into a safe community of practice, and the obligation and opportunity to experiment with collaborative approaches fostered these changes. We also found evidence of a developing landscape of practice, and perceived benefits to communities where fellows worked. We suggest programs incorporate intentional design, including networked communities of practice and heuristics, to enhance individual and systems impact.

Building collaborative conservation capacity involves more than training: applied experiences, immersion into communities of practice, and flexible funding can support long-term adoption of new approaches.

Fostering a sense of conviction for collaboration early may incite participants to engage with (sometimes uncomfortable) new experiences and groups.

Adopting “networked” communities of practice may allow collaborative conservation fellowships to reduce potential tradeoffs between individual and social systems level goals.

Management implications

Introduction

Addressing the complexity and uncertainty that typify sustainability questions while achieving social and ecological benefits requires integration across sectors and disciplines, as well as with stakeholders and local actors (Rai et al. Citation2021; Marvier and Kareiva Citation2014; Steger et al. Citation2020). Multi-party and community-engaged approaches to social-ecological systems governance, management, and research provide avenues for meaningful integration of diverse user values and perspectives, enriching decision-making inputs and enhancing local influence over the direction and pace of change (Fernández-Giménez et al. Citation2019; Stringer et al. Citation2006; Sterling et al. Citation2017). Greater community ownership of processes and outputs increases the likelihood that decisions will produce enduring, culturally and ecologically appropriate impacts (Mulrennan et al. Citation2012; Berkes Citation2010). We define such community-oriented “collaborative conservation” as formal or informal coordination of processes, including exploration, prioritization, implementation, and evaluation of actions, which bring together stakeholders who may hold diverse or adversarial knowledge and views, to address sustainability challenges in a manner that seeks to equalize power dynamics and benefit affected local actors (adapted from Ansell and Gash Citation2007; Cockburn et al. Citation2020; Feist, Plummer, and Baird Citation2020; Thomas and Mendezona Allegretti Citation2020).

As collaborative approaches to conservation have increased in recent decades (Conley and Moote Citation2001) collaborative capacity has become a priority for conservation professionals (Englefield et al. Citation2019; Elliott, Ryan, and Wyborn Citation2018), although training on collaboration with communities remains less common than between agencies (Bruyere et al. Citation2020). Capacity building can boost conservationists' adoption of new skills and desired approaches (Bruyere, Copsey, and Walker Citation2022; Sawrey, Copsey, and Milner-Gulland Citation2019), including greater openness to involving local people in management (Scholte, de Groot, and Mayna Citation2005). Capacity building captures the process by which individuals and communities transform their mindset and attitudes, and enhance the knowledge, skills, resources and systems needed to perform functions, solve problems, and achieve objectives (OECD Citation2006; United Nations Citationn.d.). Despite calls to better understand program effectiveness and utility (Newcomer, Hatry, and Wholey Citation2015), evaluation of capacity building programs remains uncommon, especially in conservation (but see: Ries Citation2019; Sawrey, Copsey, and Milner-Gulland Citation2019). Evaluation of capacity building in strongly interpersonal fields, such as collaborative conservation is therefore needed.

The wider conservation capacity development community would also benefit from illuminating the “black box” of pathways supporting adoption of new approaches (Sterling et al. Citation2021). To address these needs, we conducted one of the first evaluations of inputs and long-term impacts of collaborative conservation capacity building for academics and practitioners. We explore the Center for Collaborative Conservation’s ongoing fellowship, which aims to create collaborative conservationists while simultaneously contributing to social and ecological benefits for stakeholders. Reflecting the program’s desire to improve, our research had two main objectives:

To determine the fellowship’s impacts (i) on participants, particularly their long-term individual willingness and ability to adopt a collaborative orientation and practice, and (ii) through fellows individual funded projects;

To understand the influence of the different fellowship inputs on the perceived impacts to the fellows and their projects, and whether these varied between fellows of different disciplines and professional roles.

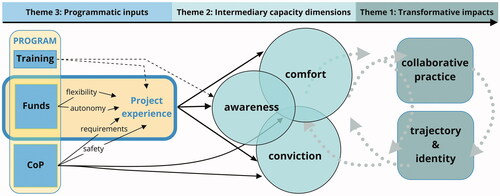

We briefly introduce the study program, then present a unified, empirically-based causal model of long-term individual-level changes in collaborative practice, highlighting intermediary dimensions of capacity which were key to adopting collaborative approaches, and the programmatic inputs which supported these changes (). We then explore fellows' evaluation of social and ecological outcomes in their individual projects, and end by suggesting ways to enhance balanced individual- and systems-level impact.

Figure 1. Empirically-based causal model of individual-level collaborative conservation capacity and practice. Important programmatic inputs (left side, Theme 3) are the project experience, flexible funding, and a safe community of practice (CoP) which expects new approaches. Multiple dimensions of capacity (Theme 2) support long-term collaborative practice, and new professional identity and trajectory (Theme 1). Dotted “spiral” represents reinforcing relationship between practice and comfort, conviction, and awareness.

Center for Collaborative Conservation Fellows Program

Established in 2008, the Center for Collaborative Conservation (CCC) in the United States is one of few programs dedicated specifically to building collaborative conservation capacity. In 2009 the CCC initiated its ongoing flagship program, the Fellows Program, to “create the ‘new conservationist’ who is passionate about using a collaborative approach to bring together different knowledge systems to create solutions to today’s complex conservation issues” (www.collaborativeconservation.org). Although no explicit Theory of Change existed at the time of this research, print and online programmatic materials from the first 10 years listed various goals, anticipated impacts, and associated pathways (Introduction S1). We summarize these as: The Fellows Program aims to enhance benefits to both conservation and communities by expanding the use of people-centred approaches across diverse boundaries to spur innovation, local relevance, and local capacity.

The fellowship includes four main structured components: (1) a training retreat, (2) an applied 18-month collaborative conservation project with (3) financial support; and (4) periodic cohort-wide meetings. Projects receive from $5000 to 15,000 and can address any issue or system, provided they (i) be collaborative (i.e., engage at least one local partner in project scoping, design, and/or implementation) or study the process of collaboration; and (ii) address both conservation and livelihoodFootnote1 components. All fellows (except Cohort 1) were required to attend a 3-day training retreat at the start of the fellowship (see Introduction S1 and Table S1 for program details).

In its first 10 years, fellows engaged with diverse collaborators (e.g., community members, private landowners and businesses, universities, non-profits, and Tribal, federal, and state representatives) in 96 mostly unrelated projects in 12 U.S. states, 17 Native American Nations, and 26 (primarily developing) countries. Although the fellowship did not collect systematic data on fellows’ age, disciplinary training, country of origin, ethnicity, or other identifiers, program documents indicate that fellows from diverse disciplinary backgrounds and interests (e.g., conservation biology, human dimensions of natural resources, political science, rangeland management, sociology) sought to better understand and/or address myriad challenges (e.g., climate change impacts, food security, forest restoration, human-wildlife conflicts, protected area management, species conservation, threats to Indigenous sovereignty, water issues) in coastal, desert, forest, mountain, rangeland, agricultural and urban environments. For a complete list of project titles and locations, see Skyelander, Hauptfeld, and Jones (Citation2019).

Methods

Study Population

By 2019, the fellowship had graduated 104 fellows (64% women; 36% men) in eight cohorts (9–18 per cohort) representing three fellow types: Colorado State University faculty (including extension staff and post-doctoral researchers; n = 20) and graduate students (master’s and doctoral; n = 55), and community practitioners (who manage natural resources privately, or in agencies, Tribal nations, NGOs, etc.; n = 29). We limited participation to alumni who had completed the program between 2010 and 2017 (i.e., Cohorts 1–8) to understand longer-term impacts (2–10 years). Due to the small alumni population, all eligible alumni with valid emails (92, excluding the lead author) were invited to participate and forty-seven responded to >50% of the survey questions and were retained (51% response rate) (see Table S2 for respondent characteristics). Thirty of the forty fellows indicating interest in an interview (34% of eligible alumni) were purposively selected to represent all eligible cohorts and fellow types. Interviews suggested that most or all interview respondents had also participated in the survey. Informed consent was solicited prior to participation.

Survey and Interview Design and Administration

We used mixed methods combining a survey and interviews (Creswell and Clark Citation2018) to explore participants’ perceptions of the program. A survey using multiple choice and 5-point Likert items evaluated alumni perspectives of program impacts (identified a priori from programmatic documents), relative influence of programmatic components, and respondent characteristics (fellow type, etc.). The survey was piloted with the active year cohort and administered online through Qualtrics from May to August 2019. Recruitment emails included an incentive to win a randomly assigned $20 gift card.

Semi-structured interviews yielded a more comprehensive understanding of causal processes (i.e., what worked and why) and unanticipated impacts (Kelle Citation2006). In person and virtual interviews were conducted by the first and second authors from June to August 2019. Interview questions addressed fellowship impacts on participants, including changes in fellows’ ability and willingness to collaborate and the nature of collaboration; the fellowship components to which fellows ascribed change; the perceived impacts of fellows’ funded projects; and recommendations for program improvements. Questions were provided prior to interviews, which were recorded and lasted 30–60 min (see Methods S1 for interview guide).

Analysis

Quantitative analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS software (Version 27.0). Descriptive statistics were run on all data to identify impacts and fellowship inputs driving these impacts. Shapiro-Wilk’s test indicated non-normal distribution of responses, so we assessed the influence of different programmatic inputs among fellows for whom the program was valuable using non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed Rank Median tests on paired Likert questions, and parametric T-tests on calculated means of grouped Likert items. To assess whether a unified empirically-based causal model was justified we tested for differences in perceptions between fellow types and disciplines [i.e., the survey asked whether respondents identified with the “natural sciences (e.g., wildlife biology, ecology, biodiversity conservation),” “social sciences (anthropology, human dimensions, livelihoods),” or “both equally” (which we term “cross-disciplinary” in this paper)] using ANOVA and corresponding non-parametric Independent Samples Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by Mann-Whitney post-hoc tests.

The first and second authors conducted thematic analysis of interview transcripts and notes (Clarke and Braun Citation2006). Code development began during the interview process. The first author conducted the initial coding of all interviews to develop a set of open codes in RQDA (R package version 0.3-1). The two authors then iteratively refined codes, listing and diagraming codes to triangulate meaningful descriptive themes (Clarke and Braun Citation2006), through the writing process and after a focus group with alumni during the program’s 10-year reunion. Quotes could support multiple themes. We present the predominant narratives related to the fellowship’s impacts and the pathways supporting those changes. Quotes have been redacted of identifiable information.

Results

Ninety-six percent of survey respondents found the fellowship professionally useful, and greater than three quarters agreed that eight of the 10 career impacts we inquired about resulted from participation (Table 1 and Figure S1). We organize results into four themes, which build on one another (). Interviews revealed substantial, and sometimes transformative, changes in fellows’ individual practice and professional trajectory (Theme 1), supported by development of intermediary dimensions of capacity, characterized by increased awareness of, comfort with, and conviction toward community-engaged collaborative approaches (Theme 2). Project experience, flexible funding and the fellowship community were the most meaningful fellowship inputs (Theme 3). Theme 4 highlights that fellows’ funded projects often evolved and were continued, and that fellows perceived social, but not ecological benefits resulted from their projects. Quotes are in and Table S6, and quantitative analyses in and Tables S3–S5.

Table 1. Comparative influence of (i) fellowship projects and Fellows Program (broadly) on individual career changes (columns 1–2); and (ii) Fellows Program on long-term (career) versus short-term (fellowship project) changes (columns 2–3).

Theme 1: Changes in Fellows’ Professional Practice and Trajectory

“I definitely think it changed the way I do things.” (Fellow 18, practitioner)

Survey respondents attributed gaining insights they used frequently (91%), and increasing integration of both collaboration (83%) and livelihood considerations (75%) in their work post-fellowship to the fellowship (). Although not all fellows shared changes in behavior during interviews, all fellow types (i.e., graduate students, faculty, and practitioners) described collaborating more frequently, deeply, intentionally and across more sectoral, disciplinary and cultural boundaries; and facilitating greater stakeholder involvement in and influence over their work.

Fellows across types reported profound, even “transformative” (Fellow 15, graduate student) influence on their professional identities, laying a “foundation” (Fellows 5 and 26, graduate students) for their subsequent trajectories. These fellows credited the fellowship experience with their increased interdisciplinarity and subsequent positions and areas of expertise, including an explicit focus on collaborative methods, seeking out partnership-based work, and integrating social and natural sciences (). New trajectories were accompanied by reorientations of interests and the development of an identity in a new field, as an expert, or as a more ethical researcher and collaborator. Conversely, fellows reported some barriers to pursuing and practicing collaboration in their post-fellowship careers, which included limited control over decisions, cultural differences in subsequent organizations and countries of employ, as well as shifts in fellows’ focus (e.g., to publishing, rather than conducting, research).

Theme 2: Intermediary Capacity Dimensions

Survey respondents perceived the fellowship improved their ability to work with a diversity of people (80%) and meet the needs of communities where they work (85%). Kruskal-Wallis test indicated no differences between graduate student, faculty or practitioner fellows; however, social science and cross-disciplinary fellows found the Fellows Program (not including fellowship projects) improved their ability to meet communities’ needs more than natural science fellows did [H(2) = 9.27, p = .010].

Interviews indicated that participation inspired and “reinforced a willingness and an ability [to collaborate] that was already there” (Fellow 24, faculty), characterized by increased (i) awareness of, (ii) comfort with, and (iii) conviction for the use of collaborative approaches (). These distinct dimensions of capacity were both outcomes of the fellowship, and pathways to enhanced collaborative practice ().

Table 2. Illustrative quotes supporting Themes 1, 2, and 3.

Increased Awareness of Collaborative Conservation

“I think part of it was honestly simply just having a definition of what collaboration and collaborative conservation is.” (Fellow 6, graduate student)

Interviewees expressed learning about the principles, norms, and tools of collaborative conservation. For some, the program “coined a phrase for work that [fellows] had already been doing” (Fellow 30, graduate student), providing an “overlay” (Fellow 16, practitioner) within which to conceptually (re)frame their work. Novice collaborators (both faculty and graduate fellows) expressed “revelation[s]” (Fellow 9, graduate student) that collaboration is more than simply working with people about conservation. Fellows emphasized learning the importance of engaging local, diverse stakeholders early and throughout the process to “make sure different perspectives and parties are at the table” (Fellow 17, graduate student), and investing time and effort to build relationships and trust through listening and patience. The fellowship also introduced a “more formal set of approaches… [and] set of tools to draw on” to accomplish these (Fellow 13, graduate student). Fellows emphasized the importance of seeing how others were approaching collaboration in diverse situations for shedding light on how “conservation is done in the real world” (Fellow 4, graduate student). One practitioner also found it “important to hear early on: ‘this is really hard’” (Fellow 16) to stay committed during a difficult collaboration.

Expanded Comfort with People and Practices

“As you develop those skills it’s less of a panic each time, getting better at knowing that it’s messy, and it’s complicated.” (Fellow 8, graduate student)

Surveys indicated that participation improved respondents’ perceived ability to work with a diversity of people in both their short-term fellowship projects (74%) and long-term careers (81%) and to meet the needs of communities where they worked short-term (70%) and long-term (85%). Long-term, most survey respondents reported the fellowship had made them more innovative (83%), and increased their leadership (83%), for instance by enhancing comfort advocating for and directing collaborative approaches.

In interviews, fellows described gaining familiarity, comfort, and confidence with the complex and interpersonal aspects of collaboration, their own collaborative orientation, and with a “wider tool set” of skills (Fellow 29, faculty) and people (). Fellows reported that the fellowship normalized collaboration as an approach, validating their research ideas and desire to work collaboratively, and challenged them to do things differently, including using different methodologies, communication styles and media. The fellowship “made it easier… to work across disciplines” (Fellow 5, graduate student) and communicate across academic rank, sectors, and cultures. It helped fellows become “more confident and comfortable in contentious situations” (Fellow 6, graduate student) and reaching out to new stakeholder groups.

Stronger Conviction of Collaboration’s Advantages

“It helped me develop kind of a philosophy for myself or a research orientation that felt like it fits who I am and that at the end of the day felt ethical.” (Fellow 22, faculty)

All survey respondents indicated collaboration was “extremely” or “very” important for conservation, and 74% believed collaboration had made their fellowship projects more relevant locally. The fellowship developed or reinforced many fellows’ conviction that community-centred collaborative approaches are preferable to conventional approaches, despite the additional time and energy requirements, reflecting a perception that collaboration’s “sum is greater than the parts” (Fellow 17, graduate student). Fellows described different reasons that collaborative conservation is “essential” (Fellows 1 and 20, graduate students), including that it improves the local salience of interventions, and is more equitable. Interviewees emphasized a newfound commitment to replacing extractive researcher-subject relationships with a more egalitarian framing. Some fellows shared paradigmatic reorientations, like learning to “value practice-based knowledge alongside academic knowledge” (Fellow 5, graduate student) or relinquishing control by “letting communities help you define how your research is gonna take place… and what the main concerns are” (Fellow 10, faculty).

Theme 3: Important Inputs to Collaborative Conservation Capacity and Practice

Interviewees expressed difficulty teasing out specific elements of the fellowship to which they attributed their perceived changes. However, both surveys and interviews highlighted that willingness and ability to pursue collaborative practices were primarily supported by the interplay of (i) the funding, particularly its unique flexibility, (ii) the project experience, and (iii) a niche and supportive community of practice (). Together these provided an opportunity and an obligation to practice and internalize collaborative conservation approaches.

Unique Nature of Funding

“New ideas were able to emerge because of it” (Fellow 5, graduate student)

Fellows ranked funding as the most influential fellowship component tested (M = 4.62) for their short-term fellowship projects, altering project outcomes for 89% of survey respondents. Kruskal-Wallis [H(2) = 9.03, p = .011] with Mann-Whitney post-hoc tests indicated graduate (Mdn = 5) and practitioner fellows (Mdn = 5) found funding significantly more important for their projects than faculty fellows (Mdn = 4); (U = 46.50, z = −2.68, p = .007; U = 15.00, z = −2.30, p = .021, respectively) (Table S5).

Funding was the most cited reason for applying to the fellowship, as it sometimes supported entire graduate research, or pilot projects, particularly among fellows working internationally. For practitioners and graduate fellows interviewed, the discrete pot of money provided some autonomy from advisors and partners to prioritize collaborative processes and community interests. Flexible parameters allowed fellows to try different approaches unsupported by other funding mechanisms, including experimenting with new tools, such as photovoice, in which they subsequently developed expertise, or regranting their funds to local initiatives. Flexible timelines for expenditures and reporting also allowed fellows the time to better understand and align their projects with local interests. Flexibility was especially important to fellows exercising collaborative norms of reciprocity (e.g., paying for partner food and travel, leaving camera equipment with communities).

Fellowship Project Experience

Fellows’ ranked projects as the most valuable fellowship input tested for their careers (mean = 4.38). Fellowship projects (Mdn = 5) produced significantly more “insights” than did the Fellows Program more broadly (Mdn = 4) (T = 30, z = −3.27, p = .001) () and in aggregate, T-tests indicated greater mean long-term impacts from fellowship projects than from the Fellows Program [t(45) = 2.12, p = 0.040] (Table S4).

Interviews reaffirmed the importance of projects, revealing two general pathways by which these built fellows’ ability and willingness to collaborate. First, projects provided a platform to gain exposure to and practice collaborative conservation approaches. For some, projects provided an entrée to unfamiliar or previously intimidating partners and stakeholder groups, such as government officials. For others, it provided “full license to go deeper” (Fellow 29, faculty) and prioritize building familiarity with new systems, geographies, and methodologies. Working though real collaborative processes and challenges, including failures, and unanticipated and unintended scenarios, increased interviewees’ comfort with the complex, context-specific, and sometimes contentious nature of collaborative conservation.

Second, fellows reported that project experiences provided first-hand evidence of the realized or potential benefits of collaboration to communities or projects, reinforcing their conviction to collaborate (). Fellows sometimes reassessed research assumptions and adjusted projects to address local stakeholder needs and interests, or applied such changes in their later work. As a graduate fellow put it, the project “helped me see ‘oh my gosh, there's all these other things they care about environmentally that I'm not looking at’. Had I talked to people in the first place, I could've done a whole different project that's way more useful to them” (Fellow 15).

Community of Practice

“That feeling of belonging to something bigger was emotionally really helpful. And again, professionally too.” (Fellow 27, practitioner)

Surveys indicated that the fellowship increased collaboration in fellows’ projects (80%) (), with 89% of respondents classifying their projects as extremely, very, or moderately collaborative. Interviewees identified cohort make-up, interpersonal interactions, a supportive organizational culture, and a sense of belonging as particularly valuable for learning, feeling supported, and challenging themselves. Fellows were drawn to the fellowship “…not just to learn best practices” (Fellow 26, graduate student), but due to an affinity with the program mission and community. Acceptance into the fellowship provided recognition, validation, and a “home” (Fellows 2 and 6, graduate students; Fellow 29, faculty) to those who previously felt isolated in their desire to work collaboratively. One graduate fellow in the natural sciences reflected that “finding your people with commonalities… makes you feel like less crazy, less of an imposter, and then helps you formulate better research questions” (Fellow 2).

Interactions with staff and other fellows precipitated short- and long-term learning and inspiration. Fellows identified learning from people “doing similar things in different ways” (Fellow 26, graduate student), emphasizing that the diversity of disciplines, academic ranks, geographies, scenarios, ideas, and tools represented within their cohorts was key for gaining a broader perspective about collaboration and their own work. As a faculty fellow summed up, you “learn a lot from contrast” (Fellow 10). For another fellow, however, being the sole practitioner in the cohort was isolating.

Learning of others’ accomplishments and proposed work led fellows to set aspirational benchmarks, and even lament they “didn’t go bold enough” (Fellow 28, faculty) in their projects. An organizational culture supportive of experimentation and even failure was noted as critical to enabling such forays into new tools and methods. To many fellows, the personalized attention and authentic guidance of organizational leadership provided inspiration. But for some interviewees, the mere existence of a community dedicated to collaboration both “lowered hurdles” (Fellow 30, graduate student) to collaboration, and afforded it “gravitas” (Fellow 11, practitioner).

In contrast to interviews, survey respondents ranked periodic fellowship meetings as the least meaningful fellowship component for both their short-term projects and careers (Table S5). Kruskal-Wallis with Mann-Whitney post-hoc tests indicated natural science fellows (Mdn = 2) found periodic meetings less useful than social science fellows (Mdn = 4) for their fellowship projects [H(2) = 7.72, p = .021] (U = 41.00, z = −2.69, p = .007), but not for their careers (, Results S1). Natural science fellows also perceived the network provided by the fellowship as less useful (Mdn = 2.5) than those in the social sciences (Mdn = 4) for their careers [H(2) = 12.39, p = .002] (U = 40.00, z = −3.59, p < .001) and their project outcomes (U = 38.50, z = −3.64, p < .001; Mdn = 2; Mdn = 5, respectively).

Other Inputs

Training sessions had comparatively low utility for both project and career outcomes (M = 3.5; 3.31, respectively) (Table S5). Fellows interviewed mentioned training less often and more briefly than other fellowship inputs described above, and several reported feeling topics were too superficial or poorly instructed. However, tools taught in training sessions had significantly greater impact on fellows’ long-term career than on their short-term projects, based on Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test (p < 0.050). Similarly, the Fellows Program had significantly higher mean impact on (long-term) career (M = 4.04, SD = 0.70) than on the (short-term) fellowship projects (M = 3.89, SD = 0.66) [t(43) = 2.74, p = .009] (Table S4).

Theme 4: Systems-Level Impacts of Collaborative Projects

“A fellowship that forces you to be involved locally and to bring in local collaborators, which then gives you insight into what’s going on at a local level and what people are struggling with, that all led to…establishing an NGO.” (Fellow 22, faculty)

Most survey respondents felt that collaboration had made their projects more relevant to the local community (74%) and helped build community capacity to deal with conservation issues (72%). About half reported their projects continued beyond their fellowship (56%).

However, no interviewee reported having conducted a project evaluation during or since their fellowship, including senior researchers and practitioners. Reasons included not knowing how; lack of funding, previous plans, or obligation to do so; changes in career focus away from the study area; discomfort evaluating voluntary partners; inability to tease out their component from a larger initiative; transferring project ownership to local partners; and difficulty connecting project outputs (e.g., species distribution maps, interviews with elders, study of a failed process) to social or ecological impacts.

Instead, when asked about project impacts, some interviewees shared that their projects had been formalized, replicated, or expanded to serve additional communities or systems, informed legal proceedings, or culminated in initiatives requested by local communities (e.g., elementary education, training in evaluation). Fellows reported financial benefits to partner communities, empowering communities to mobilize, and building relationships with communities and partners, the latter considered an “important and underrated outcome” (Fellow 24, faculty). In one project, community members used cameras to start businesses and to assert local perspectives on drought impacts to decision-makers. Another project workshop spurred participants to propose ways to transfer traditional knowledge to the younger generation and apply for funding to cultivate traditional crops for income.

Discussion

Situating Individual Impacts

Our retrospective evaluation suggests that an 18-month fellowship can result in long-term changes in participants’ capacity for and adoption of community-oriented collaborative approaches to conservation. Previous evaluations have demonstrated that training can build professional capacity and enhance participants’ community-oriented attitudes (Sawrey, Copsey, and Milner-Gulland Citation2019; Ries Citation2019) but ours is the first, to our knowledge, to demonstrate long-term changes in collaborative conservation mindset, mastery, and practice (). Our findings highlight that despite minor differences, a fellowship-style opportunity to build capacity in collaboration was salient across disciplinary backgrounds and at different career stages, including to senior faculty.

We find that adoption of new practices are preceded by the development of an array of social-psychological antecedents beyond knowledge acquisition, as demonstrated elsewhere (Reddy et al. Citation2017), including changes in attitudes, comfort, and norms (). Notably, although gaining skills in community engagement has been proposed as a precursor to being willing to engage with communities in protected area management (Scholte, de Groot, and Mayna Citation2005), we find that conviction sometimes precedes competence. Fellows in our case intentionally pursued new and sometimes uncomfortable approaches and forays across boundaries, suggesting that building conviction, and doing so early, may motivate commitment to self-directed capacity building in new professional norms. Fellows’ convictions reflected values, such as efficacy and equity, aligning with Estrada et al. (Citation2011)’s findings that connecting with individuals’ values is a strong motivator to persist within a scientific community of practice.

Other collaborative capacity interventions could build out these capacity dimensions alongside content knowledge and skills, drawing on behavior change approaches summarized elsewhere (e.g., Stern 2018). For example, our results evoke the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), which suggests that motivated audiences engage with information differently, and show more persistent changes in attitude and behavior.

Situating Capacity Building Inputs

Our research supports the finding that exposing people to knowledge and tools is not sufficient to build capacity (Englefield et al. Citation2019). Instead, it highlights the importance of experiential and relational components, supported by flexible funding and a safe community of practice for building willingness and ability to pursue complex, relational, and context-specific approaches.

Practice with authentic experiences increases the likelihood that skills will transfer to similar situations (Wlodkowsi Citation2008; Caffarella and Daffron Citation2013), and the cultural and social aspects of learning by doing (Morris Citation2020) are particularly relevant to collaborative conservation. Experiences with novel, uncertain, or challenging situations may also spark reflexivity, challenging learners’ previously assimilated concepts (Kolb Citation1984; Morris Citation2020). This aligns with the paradigm shifts we noted with some Center for Collaborative Conservation fellows. Experiential learning engages learners both intellectually and emotionally, underscoring the importance of actively and explicitly cultivating psychological safety among participants to support experimentation on the path to mastery (Catalano et al. Citation2018).

Funding plays a role in driving shifts toward collaborative governance (Abrams et al. Citation2020) and collaborative research framing (Wuelser and Pohl Citation2016). We also found that funding served to catalyze collaborative capacity building, attracting individuals who may not have otherwise been exposed to the norms of the community of practice. Funding flexibility was particularly instrumental for enacting collaborative norms, such as reciprocity and adapting to partner interests. In this case, the impact of funding was tightly coupled with an organizational culture that inspired and expected new practices and developed conviction, which may be key for small grants to have transformative impact.

Our results underscore that association with the community of practice (CoP) was critical to fellows’ pathways of change. CoPs, increasingly called for to address complex environmental problems, are groups of people who build individual performance and identity, relationships, and collective results through shared and sometimes curated engagement activities around common interests (Watkins et al. Citation2018; Reed et al. Citation2014). Although the fellows worked in (largely) non-related projects, we found that many adopted the collective norms and social identity of the collaborative conservation CoP, which provided framing for what is possible, expected, and desirable (Wenger Citation1998) in their projects and longer term. For many, a sense of belonging to a dispositional home was foundational for committing to and persisting in the field (Mourad et al. Citation2018), and learning benefited from a safe space and a balance of similarity with diversity in ranks, fields of study, and geographies.

Fellowship projects concurrently served as curated activities of the fellowship CoP, and distinct CoPs where fellows worked with collaborators in disparate geographies, systems, and sectors. As such, the CCC fellowship may be shaping a growing landscape of practice made up of core individuals across organizations, bound loosely by their similar practices and sense of commitment to collaboration (Pyrko, Dörfler, and Eden Citation2019), an unanticipated systems-level impact.

Despite fellows’ strong emphasis on learning from and building connections with cohort and staff, the interactive components we tested (periodic meetings and networking with fellows) ranked low, especially among natural science fellows. The reasons for this are hard to trace because periodic meeting content evolved over the years, and program staff reported that attendance at meetings fluctuated, particularly among faculty. Survey questions may have also failed to make salient the social elements within training retreats or other group activities that supported relationship building and discussions.

Balancing Individual Capacity Development with Systems-Level Impact

The Fellows Program pursues livelihoods and conservation impacts through the fellowship projects it supports. However, we found little evidence that fellows had formally measured social or ecological outcomes from their projects. This was unsurprising, given that assessment of systems-level impacts in collaborative conservation is uncommon (Wilkins et al. Citation2021), particularly for ecological outcomes, which are often delayed, distal to, or difficult to link to the collaborative intervention (Conley and Moote Citation2003; Koontz, Jager, and Newig Citation2020).

We note that that the fellowship’s simultaneous individual and systems level goals may represent a tradeoff. Seeking to achieve on the ground impact through trainees may unintentionally undermine the program characteristics that support the types of transformative changes we found in the fellows. For instance, project failures, which were valuable learning opportunities for fellows, may have no measurable impact to communities or ecosystems. A preference for accepting experienced participants or established collaborations, and an emphasis on achieving conservation goals rather than learning complex relational capacities, could lead to greater social-ecological systems impact during the funded project, while inadvertently stifling individual experimentation, and raising epistemic barriers to entry for novice collaborators (Wenger Citation1998). This could reduce a program’s ability to attract more inexperienced fellows or those hoping to learn new approaches—the very participants who might grow the most from the fellowship. Additionally, challenging participants to try new skills and approaches, such as using alternative media, may reduce short-term proficiency and impact, but prove valuable in the long run, as we saw with fellows attributing greater long-term impact from the fellowship than short-term.

One approach to navigating these tradeoffs could be the use heuristic models (Cockburn et al. Citation2020) or Theories of Change in trainings to improve fellows’ evaluation know-how, identified as a gap by fellows, and potentially improve projects. Fellows would gain practice identifying what would be measured, why, and by which methodologies. Explicitly working through the mechanisms and the influence of context could improve the likelihood of achieving desired impacts (Emerson and Nabatchi Citation2015; Clement, Guerrero Gonzalez, and Wyborn Citation2020). Doing so within diverse disciplinary cohorts could build interdisciplinary competence (as called for by Bennett et al. Citation2017) and support integrated assessment of social and ecological outcomes (Koontz, Jager, and Newig Citation2020).

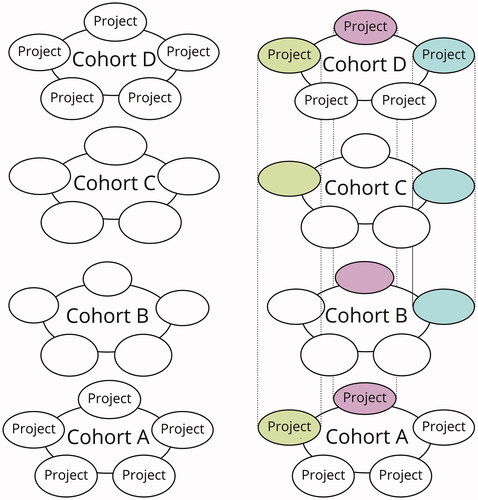

Second, a networked community of practice model (), characterized by sustained partnerships in specific locations across multiple fellowship projects, could help programs like this achieve individual and systems-level objectives concurrently. We were not able to evaluate fellowship impacts from the perspective of communities and collaborators, due to the diversity of fellows’ projects and paucity of contact information for past project partners. However, sequential projects in one locality could enhance the program’s ability to impart, assess, and detect social and ecological changes. Moreover, since collaborative approaches seek not only to work with local people, but to divest power to stakeholders (Larson and Ribot Citation2004), longer investments in locally-led, place-based groups can reduce “parachute” involvement (Asase et al. Citation2022). Financially supporting the types of community-generated projects fellows reported could augment collaborator self-efficacy (Bruyere, Copsey, and Walker Citation2022) and involving collaborators in developing and assessing heuristic models (Onyango Citation2018) could increase local capacity, key in achieving social and ecological benefits (Brooks Citation2017).

Figure 2. Networked community of practice model (right) characterized by sustained attention to localities over multiple fellowships would link current (left) siloed cohort communities of practice (CoPs) and project CoPs and provide opportunities for mentoring.

Both the funding and the fellowship community filled a perceptible gap for fellows. However, we found that fellows rarely remained involved in the fellowship community after their tenure, and that the program fell short of providing a useful network, particularly for fellows in the natural sciences. As collaboration becomes more commonplace within conservation, maintaining high impact for participants may require adaptations to meet fellows’ changing expectations. A networked community of practice model could increase learning across previously siloed cohorts, while engaging fellows and alumni in differentiated roles, for instance through mentoring (Dietz et al. Citation2004; Robins Citation2008).

While this research showcases the strengths of a retrospective study using qualitative analysis to identify important inputs, our study had limitations. Although we achieved a good response rate (51%) from representative proportions of fellow types, and received responses from alumni who did not rate the fellowship highly, all survey respondents felt collaboration was extremely or very important for conservation. This may reflect self-selection bias. Concurrent delivery of survey and interview methods, precipitated by short program reporting deadlines, means we were unable to explore findings from the survey in our interviews, such as differences among disciplines. Nor did we have baseline data on fellows’ experience or competency levels prior to participation. However, the program has begun to add quantitative measures to gauge short-term changes in perceived competence, a practice used in the evaluation of similar conservation capacity development programs (Sandbrook et al. Citation2021). We also recommend gathering data on gender and other identity attributes, to understand how these relate to program impact on the individual.

Conclusion

This research confirms the importance of belonging to a dispositional home or community of practice and applied experiences, including experimentation and the possibility of failure, in supporting deep learning and the development of competence and willingness to adopt new norms in this complex and context-specific field of collaborative conservation. Achieving target behaviors requiring paradigmatic shifts may benefit from building participants’ conviction early, to support commitment to practice. Maintaining low epistemic barriers may allow programs to attract participants new to collaborative conservation, but requires recognition of potential tradeoffs between individual and systems-level impacts without the integration of supportive practices like networked communities of practice and use of heuristics. In these ways, collaborative conservation researchers and practitioners can continue to move the needle on how to work effectively and collectively to address today’s most complex and urgent ecological challenges.

USNR-2021-0348-File015.docx

Download MS Word (16.4 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File014.docx

Download MS Word (13.5 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File013.docx

Download MS Word (16.2 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File012.docx

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File011.docx

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File010.png

Download PNG Image (326.3 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File009.docx

Download MS Word (15.9 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File008.docx

Download MS Word (14.8 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File007.docx

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)USNR-2021-0348-File006.docx

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Acknowledgments

This study was conducted under Institutional Review Board #19-8978H. Special thanks to Drs. K. Hoelting and D.-L. Hunter for their invaluable input on previous drafts and figures. We would also like to thank Drs. J. Zarestky, B. Bruyere, L. Pejchar, and J. Sanderson for their support and feedback on previous drafts, as well as five anonymous reviewers, whose suggestions greatly improved the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The program used “livelihoods” to encompass social outcomes including well-being, entrepreneurial development, education, gender equity, and cultural knowledge transmission.

References

- Abrams, J., H. Huber-Stearns, H. Gosnell, A. Santo, S. Duffey, and C. Moseley. 2020. Tracking a governance transition: Identifying and measuring indicators of social forestry on the Willamette National Forest. Society & Natural Resources 33 (4):504–23. doi:10.1080/08941920.2019.1605434.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4):543–71. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Asase, A., T. I. Mzumara‐Gawa, J. O. Owino, A. T. Peterson, and E. Saupe. 2022. Replacing ‘parachute science’ with ‘global science’. Conservation Science and Practice 4 (5): 1–7. doi:10.1111/csp2.517.

- Bennett, N. J., R. Roth, S. C. Klain, K. M. A. Chan, D. A. Clark, G. Cullman, G. Epstein, M. P. Nelson, R. Stedman, T. L. Teel, et al. 2017. Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conservation Biology 31 (1):56–66. doi:10.1111/cobi.12788.

- Berkes, F. 2010. Devolution of environment and resources governance: Trends and future. Environmental Conservation 37 (4):489–500. doi:10.1017/S037689291000072X.

- Brooks, J. S. 2017. Design features and project age contribute to joint success in social, ecological, and economic outcomes of community-based conservation projects. Conservation Letters 10 (1):23–32. doi:10.1111/conl.12231.

- Bruyere, B., J. Copsey, and S. Walker. 2022. Beyond skills and knowledge. The role of self-efficacy and peer networks to build capacity for species conservation planning. Oryx 1–9. doi:10.1017/S0030605322000023.

- Bruyere, B., N. Bynum, J. Copsey, A. Porzecanski, and E. Sterling. 2020. Conservation leadership capacity building: A landscape study. Summary of key findings.

- Caffarella, R. S. and S. R. Daffron. 2013. Devising transfer of learning plans. In Planning programs for adult learners, 209–36. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Catalano, A. S., K. Redford, R. Margoluis, and A. T. Knight. 2018. Black swans, cognition, and the power of learning from failure. Conservation Biology 32 (3):584–96. doi:10.1111/cobi.13045.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Clement, S., A. Guerrero Gonzalez, and C. Wyborn. 2020. Understanding effectiveness in its broader context: Assessing case study methodologies for evaluating collaborative conservation governance. Society & Natural Resources 33 (4):462–83. doi:10.1080/08941920.2018.1556761.

- Cockburn, J., M. Schoon, G. Cundill, C. Robinson, J. A. Aburto, S. M. Alexander, J. A. Baggio, C. Barnaud, M. Chapman, M. Garcia Llorente, et al. 2020. Understanding the context of multifaceted collaborations for social-ecological sustainability: A methodology for cross-case analysis. Ecology and Society 25 (3):1–15. doi:10.5751/ES-11527-250307.

- Conley, A., and A. Moote. 2001. Collaborative conservation in theory and practice: A literature review.

- Conley, A., and M. A. Moote. 2003. Evaluating collaborative natural resource management. Society & Natural Resources 16 (5):371–86. doi:10.1080/08941920390190032.

- Creswell, J. M., and V. L. P. Clark. 2018. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Dietz, J. M., R. I. N. A. Aviram, S. Bickford, K. Douthwaite, A. M. Y. Goodstine, J.-L. Izursa, S. Kavanaugh, K. MacCarthy, M. O'Herron, and K. E. R. I. Parker. 2004. Defining leadership in conservation: A view from the top. Conservation Biology 18 (1):274–8. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00554.x.

- Elliott, L., M. Ryan, and C. Wyborn. 2018. Global patterns in conservation capacity development. Biological Conservation 221:261–9. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2018.03.018.

- Emerson, K., and T. Nabatchi. 2015. Evaluating the productivity of collaborative governance regimes: A performance matrix. Public Performance & Management Review 38 (4):717–47. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2015.1031016.

- Englefield, E., S. A. Black, J. A. Copsey, and A. T. Knight. 2019. Interpersonal competencies define effective conservation leadership. Biological Conservation 235:18–26. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.043.

- Estrada, M., A. Woodcock, P. R. Hernandez, and P. W. Schultz. 2011. Toward a model of social influence that explains minority student integration into the scientific community. Journal of Educational Psychology 103 (1):206–22. doi:10.1037/a0020743.

- Feist, A., R. Plummer, and J. Baird. 2020. The inner-workings of collaboration in environmental management and governance: A systematic mapping review. Environmental Management 66 (5):801–15. doi:10.1007/s00267-020-01337-x.

- Fernández-Giménez, M. E., D. J. Augustine, L. M. Porensky, H. Wilmer, J. D. Derner, D. D. Briske, and M. O. Stewart. 2019. Complexity fosters learning in collaborative adaptive management. Ecology and Society 24 (2):29–50. doi:10.5751/ES-10963-240229.

- Kelle, U. 2006. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in research practice: Purposes and advantages. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (4):293–311. doi:10.1177/1478088706070839.

- Kolb, D. A. 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, 20–38. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7506-7223-8.50017-4.

- Koontz, T. M., N. W. Jager, and J. Newig. 2020. Assessing collaborative conservation: A case survey of output, outcome, and impact measures used in the empirical literature. Society and Natural Resources 33 (4):1–20. doi:10.1080/08941920.2019.1583397.

- Larson, A. M., and J. C. Ribot. 2004. Democratic decentralisation through a natural resource lens: An introduction. The European Journal of Development Research 16 (1):1–25. doi:10.1080/09578810410001688707.

- Marvier, M., and P. Kareiva. 2014. The evidence and values underlying ‘new conservation’. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29 (3):131–2. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.005.

- Morris, T. H. 2020. Experiential learning–A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments 28 (8):1064–77. doi:10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279.

- Mourad, T. M., A. F. McNulty, D. Liwosz, K. Tice, F. Abbott, G. C. Williams, and J. A. Reynolds. 2018. The role of a professional society in broadening participation in science: A national model for increasing persistence. BioScience 68 (9):715–21. doi:10.1093/biosci/biy066.

- Mulrennan, M. E., R. Mark, C. H. Scott, M. E. Mulrennan, R. Mark, and C. H. Scott. 2012. Revamping community-based conservation through participatory research. The Canadian Geographer 56 (2):243–59. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00415.x.

- Newcomer, K. E., H. P. Hatry, and J. S. Wholey. 2015. Handbook of practical program evaluation. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- OECD. 2006. Applying strategic environmental assessment: Good practice guidance for development co-operation. Paris: OECD.

- Onyango, R. O. 2018. Participatory monitoring and evaluation: An overview of guiding pedagogical principles and implications on development. International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences 5 (4):428–33.

- Pyrko, I., V. Dörfler, and C. Eden. 2019. Communities of practice in landscapes of practice. Management Learning 50 (4):482–99. doi:10.1177/1350507619860854.

- Rai, N. D., M. S. Devy, T. Ganesh, R. Ganesan, S. R. Setty, A. J. Hiremath, S. Khaling, and P. D. Rajan. 2021. Beyond fortress conservation: The long-term integration of natural and social science research for an inclusive conservation practice in India. Biological Conservation 254:108888. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108888.

- Reddy, S. M. W., J. Montambault, Y. J. Masuda, E. Keenan, W. Butler, J. R. B. Fisher, S. T. Asah, and A. Gneezy. 2017. Advancing conservation by understanding and influencing human behavior. Conservation Letters 10 (2):248–56. doi:10.1111/conl.12252.

- Reed, M. G., H. Godmaire, P. Abernethy, and M. André Guertin. 2014. Building a community of practice for sustainability: Strengthening learning and collective action of Canadian biosphere reserves through a national partnership. Journal of Environmental Management 145:230–9. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.06.030.

- Ries, P. D. 2019. Evaluating impacts of the Municipal Forestry Institute leadership training on participants’ personal and professional lives. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 39:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.02.002.

- Robins, L. 2008. Making capacity building meaningful: A framework for strategic action. Environmental Management 42 (5):833–46. doi:10.1007/s00267-008-9158-7.

- Sandbrook, C., Howard, P. Nelson, S. Bolderson, and N. Leader-Williams. 2021. Evaluating the impact of the first 10 years of the Cambridge masters in conservation leadership. Oryx 1–10. doi:10.1017/S0030605321000818.

- Sawrey, B., J. Copsey, and E. J. Milner-Gulland. 2019. Evaluating impacts of training in conservation: A case study in Mauritius. Oryx 53 (1):117–25. doi:10.1017/S0030605316001691.

- Scholte, P. A. U. L., W. T. de Groot, and Z. Mayna. 2005. Protected area managers’ perceptions of community conservation training in West and Central Africa. Environmental Conservation 32 (4):349–55. doi:10.1017/S0376892905002523.

- Skyelander, K., R. Hauptfeld, and M. S. Jones. 2019. 10-Year review of the Center for Collaborative Conservation Fellows Program: An assessment of impacts. Fort Collins, CO, Center for Collaborative Conservation, Colorado State University.

- Steger, C., G. Nigussie, M. Alonzo, B. Warkineh, J. Van Den Hoek, M. Fekadu, P. H. Evangelista, and J. A. Klein. 2020. Knowledge coproduction improves understanding of environmental change in the Ethiopian highlands. Ecology and Society 25 (2):1–11. doi:10.5751/ES-11325-250202.

- Sterling, E. J., A. Sigouin, E. Betley, J. Zavaleta Cheek, J. N. Solomon, K. Landrigan, A. L. Porzecanski, N. Bynum, B. Cadena, S. H. Cheng, et al. 2021. The state of capacity development evaluation in conservation and natural resource management. Oryx 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0030605321000570.

- Sterling, E. J., E. Betley, A. Sigouin, A. Gomez, A. Toomey, G. Cullman, C. Malone, A. Pekor, F. Arengo, M. Blair, et al. 2017. Assessing the evidence for stakeholder engagement in biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation 209:159–71. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.02.008.

- Stringer, L. C., A. J. Dougill, E. Fraser, K. Hubacek, C. Prell, and M. S. Reed. 2006. Unpacking ‘Participation’ in the adaptive management of social–ecological systems: A critical review. Ecology and Society 11 (2):39. doi:10.5751/ES-01896-110239.

- Thomas, R. E. W., and A. Mendezona Allegretti. 2020. Evaluating the process and outcomes of collaborative conservation: Tools, techniques, and strategies. Society & Natural Resources 33 (4):433–41. doi:10.1080/08941920.2019.1692116.

- United Nations. n.d. Capacity building. https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/capacity-building (accessed March 3, 2022).

- Watkins, C., J. Zavaleta, S. Wilson, and S. Francisco. 2018. Developing an interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral community of practice in the domain of forests and livelihoods. Conservation Biology 32 (1):60–71. doi:10.1111/cobi.12982.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkins, K., L. Pejchar, S. L. Carroll, M. S. Jones, S. E. Walker, X. A. Shinbrot, C. Huayhuaca, M. E. Fernández-Giménez, and R. S. Reid. 2021. Collaborative conservation in the United States: A review of motivations, goals, and outcomes. Biological Conservation 259:109165. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109165.

- Wlodkowsi, R. J. 2008. Enhancing adult motivation to learn: A comprehensive guide for teaching all adults. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: A Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series.

- Wuelser, G., and C. Pohl. 2016. How researchers frame scientific contributions to sustainable development: A typology based on grounded theory. Sustainability Science 11 (5):789–800. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0363-7.