Abstract

Communities can play an important role in the transition toward sustainable living; however, a meso perspective bridging individual behavior and social context has rarely been applied. To address this issue, our study introduces the broad landscape of nonprofit community-based organizations as meso-level entities whose activities relate in one way or another to sustainability. Through an exploratory study relying on in-depth interviews, we examine the meaning of community and the role of sustainability in the operation of these communities. The emergence of a new authoritarianism in Hungary gives a special context for the study and enables identification of the characteristics of urban communities from “illiberal democracy.” The findings indicate the presence of five different types of community-based organizations with sustainability-related activities. We argue for the analytical usefulness of a meso-level perspective and for the importance of researching how community-based organizations help individuals in transition to a more sustainable lifestyle.

Introduction

Transitioning material and energy-intensive economies and lifestyles toward ecologically and socially sustainable systems is among the most urgent tasks, requiring wide-scale and various forms of collective action (Spash and Dobernig Citation2017). Thus, organizations where individuals can socialize (adapt and pass on) sustainability-oriented practices and attitudes, while also (possibly) organizing collective action, could be spaces and effective vehicles of change.

Thirty years after the collapse of “actually existing socialism” (Murphy Citation2018, 283), environmental organizations are struggling in Hungary. State centralization of power has had a huge impact on the operation of civil society (Krasznai Kovács Citation2021), which is under attack by state-funded propaganda and law (Krasznai Kovács and Pataki Citation2021). This situation clearly reduces the space for environmental activism in the country (Buzogány, Kerényi, and Olt Citation2022). Considering the brief historical development of environmentalism in Hungary, it is interesting to note that the first civic movement in the early years of political transition in the 1990s was an environmental one (Buzogány Citation2015). Following the regime change in 1990, new regulations enabled the appearance of international green organizations like Greenpeace, WWF, and other environmental NGOs (Krasznai Kovács and Pataki Citation2021). Later, in 2004, EU accession provided a supportive political space and financing for environmental organizations. The new “illiberal democracy” creates unfavorable circumstances for green groups while meaningful environmental consultation has been eliminated (Krasznai Kovács and Pataki Citation2021). Nevertheless, new environmental movements arrived in 2018 with climate demonstrations organized by Fridays for Future and Extension Rebellion (see, e.g., Fridays For Future Citation2019) as part of global trends.

Bozóky (Citation2018, 69) argues the Hungarian authoritarian regime deals with civic organizations aggressively and “an official of the governing party declared, independent NGOs ‘must be swept out of Hungarian public life’ because they interlope in politics.” As Krasznai Kovács and Pataki (Citation2021, 45) stated in their essay, “government seeks to diminish the voice, reach and strength of the environmental community.” Despite top-down hostility, Hungarian society still displays interest in ecological sustainability (Naz et al. Citation2020). But how can people learn about the topic and find support for a more sustainable lifestyle during a period of decline in the environmental sector in Hungary?

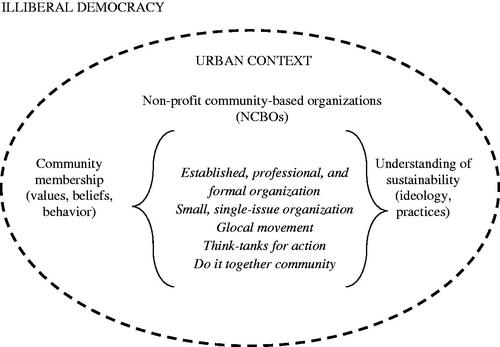

The answer may relate to the significance of communities in ecological sustainability, as acknowledged in the literature (Hofmeister-Tóth, Kelemen, and Piskóti Citation2012; Király et al. Citation2013; Kiss et al. Citation2018). Accordingly, our main research question relates to communities with the help of the concept of nonprofit community-based organizations (NCBO). In the context of illiberal democracy in Budapest, this study aims to (1) explore the types of NCBOs that operate and respond to the deepening ecological crises, (2) interpret community membership within NCBOs, and (3) evaluate the understanding of sustainability for the operation of NCBOs.

Our approach defines sustainability-related activities broadly and goes beyond the study of old, traditional “green” and explicitly green labeled organizations. This approach is justified by the societal background of the study, namely the above-mentioned obstacles under which civil organizations operate. Community represents a central term for this study, which allows the introduction of the heterogeneous membership of Budapest’s sustainability networks. Further, we adapted the concept of community-based organizations from Middlemiss (Citation2010, Citation2011); therefore, our analysis is not limited to communities defined by territorial boundaries. As a result, this study contributes to the discourse on the relevance of communities in the transition toward sustainable behavior and demonstrates the analytical usefulness of a meso perspective. It is important to note that individual transition toward sustainability may emerge because of community membership, but this study does not deal with this change in detail, but focuses instead on the meso-level understanding of the studied phenomenon.

Theoretical Background

The Concept of Community and Community-Based Organization

The concept of community incorporates two different meanings according to Gusfield (Citation1978)—territorial and relational. The former connotation relates to the geographical concept of community and includes neighborhoods and settlements. The latter meaning reflects the “quality of character of human relationships, without reference to location” (Gusfield Citation1978, xiv) and considers, among other elements, common interests, professions, and values. As Heller (Citation1989, 6) emphasizes, these communities “provide a diversity of opportunities for participation and are likely to engender greater loyalty and sense of community than locality-based units.” In line with this approach, Crowther and Cooper (Citation2002) point out the significance of a shared interest for the identification of a community, just as the idea of sustainability is able to organize committed people into communities (Kennedy Citation2011).

As previous research results show, community-based organizations can successfully mobilize people toward sustainable practices (Middlemiss Citation2010, Citation2011). Middlemiss (Citation2010) defines community-based organizations as any community groups that are vital to individuals such as workplaces, schools, social groups, or clubs. Accordingly, our study considers organizations that are based on relationally tied communities related to sustainability together with the territorial definition.

Meso-Level Perspective in the Field of Sustainability

Meso-level analysis focuses on organizations (Austin and Seitanidi Citation2012), considers the influence of social norms (Jamšek and Culiberg Citation2020), and “enriches both structural and interactional approaches, stressing shared and ongoing meaning” (Fine Citation2012, 4.1). Meso-level concepts aim to observe and understand the hidden interaction between macro- and micro-levels (Haanpaa Citation2007). Reid, Sutton, and Hunter (Citation2010) emphasize that the meso-level includes active entities that can influence social life. According to their approach, the meso sphere is more than a recipient of macro-level changes and aggregators of micro-level actions. Accordingly, the consideration of the meso perspective is “crucial” (Lusch, Vargo, and Gustafsson Citation2016) and yet the understanding of meso context is often overlooked.

In relation to sustainability, meso-level research presents an opportunity to go beyond the conventional differentiation of the individual (micro) and social (macro) levels (Reid, Sutton, and Hunter Citation2010). Reid, Sutton, and Hunter (Citation2010) have suggested a conceptual framework for the study of pro-environmental behavior that emphasizes the significance of the meso-level understanding (e.g., households, social movements, and voluntary organizations) as generators of attitudes toward sustainable behavior, mediators of social norms, and supporters of people’s perceptions of their ability to perform sustainable behavior. Following this call, our study aims to understand the relevance of NCBOs in the transition toward sustainable behavior in Budapest. In our approach, community-based organizations represent the meso-level between individuals as members of organizations (micro) and society as a whole (macro).

Applying the meso-level approach in the US context, the Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project (STEW-MAP) mapped urban green communities in several cities and collected detailed information about the organizational characteristics of local environmental groups together with their collaborative ties amongst members of the network (Svendsen et al. Citation2016). Our study, using a broad definition for communities dealing with sustainability-related topics, adds a new angle to the STEW-MAP project by involving a Central Eastern European country and offers an opportunity to explore environmental communities with civil society working under challenging political and societal circumstances.

Methods

Design and Sampling

To understand NCBOs working in Budapest (Hungary), qualitative research was conducted between May and October 2020. Due to the exploratory nature of our study, semi-structured interviews were carried out with representatives of NCBOs. In total, 23 interviews with key informants were performed, and 21 interviews were later analyzed covering a broad variety of individual characteristics as well as organizational backgrounds. Two interviews were eliminated from analysis as they were originally included for the purpose of variation in the study; however, they represented for-profit environmental organizations that mainly focused on business and not on community building.

The sampling procedure followed maximum variation (heterogeneity) sampling to support a holistic understanding of the studied phenomenon (Suri Citation2011). Unfortunately, there is no available information about the size of the population of community-based organizations dealing with sustainability-related topics in Budapest. Further, this size is difficult to estimate considering the broad definition of community (including informal organizations) we used in this study. For this reason, organizations and interviewees were selected based on their potential to contribute to the study. The chosen organizations operate in Budapest, Hungary, which provides a local, urban context to the study. Based on the sampling procedure, conclusions from this study are not generalizable but allow the understanding of different types of communities through the eyes of their leaders and in a particular political space, namely in the context of authoritarianism. Therefore, our research may present only part of the total picture, but it is a relevant one in Central Eastern Europe (see the introduction of the validation workshop below) and can be compared to similar results administered in liberal democracies.

This study sought to capture a wide range of perspectives relating to NCBOs and ecological sustainability; three conditions were therefore applied for the identification of potential organizations (see the details in ):

Table 1. Sample information about organizations in the study.

The organizational type (formal: professional or employee based, informal: mainly volunteer-based, social movements);

The field of operation (e.g., energy, mobility and transportation, food, waste, chemicals, social inequalities, ecosystem services, fashion, animal protection, and broad multifield operations); and

The level of experience based on the number of years of operation.

The interviews were organized in two waves. First, three organizations with a minimum of ten years operation in nonprofit sustainability-related activities were selected, and high-level experts from these organizations were interviewed in May 2020 (Wave 1). The aim of this phase was to gather knowledge on the landscape of NCBOs dealing with ecological sustainability issues in Budapest. The second phase of the study involved 18 interviewees from diverse areas of NCBOs with ecological sustainability–related activities (Wave 2). Interviewees were identified through the suggestions of the expert interviewees from Wave 1 and by a snowball technique via interviewees.

Data collection and analysis occurred in parallel, and organizations/key stakeholders were recruited until data saturation was reached. This approach helped the identification of common themes and resulted in a detailed understanding of ecological sustainability–related community management. Respondents from Wave 2 were leaders or senior members of their respective organizations, and interviews were conducted between June and October 2020 (see ).

To validate the findings of the interview phase (Wave 1 and Wave 2), a validation workshop was organized. Participants were experts in nonprofit sustainability–related activities with the following inclusion criteria: academic researchers with more than three years of experience in studying organizations dealing with ecological sustainability activities or representatives of nonprofit community-based organizations with more than three years of experience. In total, 21 professionals (both academic and nonprofit professionals) participated in the workshop, and they were divided into two working groups covering two main topics that focused on the two main themes of the research results: the understanding of sustainability in NCBOs (Topic 1) and the characteristics of NCBOs (Topic 2). Each topic was moderated by one of the researchers from the research team and each participant was able to contribute to both topics. Members of Group 1 started with Topic 1 and changed to Topic 2 after the half-time break. Members of Group 2 started with Topic 2, and later changed to Topic 1. The types of NCBOs were presented to the representatives of the organizations, who could respond about whether they thought that the suggested labels/categorizations were relevant for them and whether they could categorize/place themselves within this system. In the end, members of the workshop validated the results of the qualitative analysis.

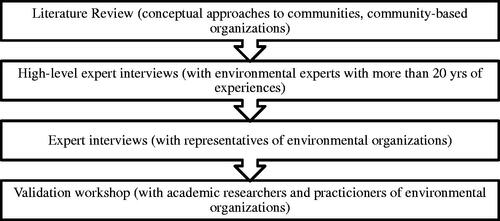

illustrates the stages of the study, which was carried out following four stages: literature review, high-level expert interviews, expert interviews, and validation workshop.

Interview Schedule

Interviews lasted between 40 and 90 minutes and were undertaken in person or via online platforms due to COVID-19 restrictions. An interview guide was developed to ensure consistency of data across interviewees, but questions remained open to allow flexibility during the interviews. Interview questions related to the characteristics of the organization, the role of interviewees in the organization, the operation of the community, members of the community, the role of sustainability in the community, and connections to other communities. All interviews were recorded with the consent of the respondents, and transcripts were prepared based on the recorded interviews. See interview questions in the Appendix ().

Qualitative Analysis

Based on the qualitative data, thematic analysis was carried out. Themes emerging from the interviews were strongly linked to community-related theoretical concepts. Our analysis introduces the experiences, meanings, and the reality of representatives of NCBOs, and also analyzes “the ways in which events, realities, meanings, experiences and so on are the effects of a range of discourses operating within society”—in our case within the studied communities (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 81).

The analysis followed the stages of thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). First, data from interviews were merged into a single data set. The analytical procedure was managed with the help of NVivo software using predefined and in vivo codes (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). Based on the research questions, meaning units were identified and systematically coded by two coders (authors of the article) for intercoder reliability. Differences in coding were discussed and the coding protocol adjusted accordingly. Through the coding and sorting process, the metalevel codes emerged. The final themes were identified by clarification and mutually agreed upon within the research team.

The final code list was produced in three steps: (1) an a priori code list was prepared primarily derived from the research questions and the literature; (2) a test coding was conducted (both researchers coding the same text, followed by a discussion); and (3) after a test coding, the original code list was revised, all codes were redefined, and new codes emerging from the text were agreed upon and added. Using the final code list, all transcriptions were coded by one researcher. The analysis includes verbatim quotations spoken by research participants; these have been translated from Hungarian into English by the authors.

Results

To position the results, the article first embeds NCBOs into the context of illiberal democracy. Then, sustainability-related NCBOs are introduced, followed by the meaning of community for NCBOs. Finally, the meaning of sustainability in the studied organizations is discussed ().

The Context of Illiberal Democracy

The idea of illiberal democracy has implications for the operation of nonprofit and community-based organizations in Hungary. The political and societal circumstances of their operation appeared in the interviews in response to different questions and topics. First, environmental organizations are affected by state-level issues, as Interviewee 2 mentioned, “it was interesting that in a workshop related to sustainable consumption we got to the point of corruption in every thread, and we said, well, it’s a [huge issue].” Interviewee 3 also mentioned that, “for development, measures from above are also needed… now things from above do not make this possible.”

Further, the political climate defines the room for environmental actions and communication and creates risks for these actions. Interviewee 5 recognized that, “in London, civil disobedience and unannounced actions are already being carried out, but here in Hungary the risk of this is higher, which is why we could not go beyond to organize such actions.” Another interviewee highlighted that, “in Hungary today, one needs extra motivation to be part of civil society” (Interviewee 12). Related to communication and the state of the media and press freedom in the country, Interviewee 8 mentioned that, “one of the biggest things is if you manage to get into the independent media, of course it would be even better to get into pro-government ones as well, but that happens less often.”

In a polarized society avoiding political conflicts amongst members of the organization and focusing on practical issues rather than theoretical ideas are also concerns. Politicians and opinion leaders in the ruling party often link climate catastrophe with Anti-Westernism and suggest that climate movements are driven by political interests (Mikecz, Böcskei, and Vasali Citation2022). As a result, the socio-demographic and ideological differences among members can be overcome and the attention kept on the cause. In the case of a cycling advocacy organization, this means that

[the cause of] cycling is kept as a single-issue movement, and maybe this is why a great number of different people can work together for this cause, because they unite in this one. So, there are members, activists, etc. from the far right to the far left—this is why we do not take a stand on other social issues [which could divide us]. (Interviewee 17)

Types of Sustainability-Related and Non-Profit Community-Based Organizations

The scope of our qualitative analysis related to meso-level communities in sustainability covered NCBOs in Budapest. As a result, we identified five different types of NCBOs. In addition to old, traditional, and established organizations, four further, new categories were recognized (see ). It is important to note that this is not a strict classification from a large-scale quantitative study, which means that there is not a single characteristic that determines group membership for a community. The analysis was led by the aim to put communities with similar attributes together and at the same time to create groups that were as distinct as possible.

Table 2. Characteristics of various types of nonprofit community-based organizations dealing with sustainability issues.

The created groups are based on the following considerations: (1) the community is operating with the help of full-time employees and/or volunteers, (2) the level of their geographical impact, (3) the focus of their activity, (4) the territorial or relational communities, and (5) the characteristics of organizational processes (centralized, managed by structure and hierarchy, or flexible with processes are adaptive and easy to change).

Established, professional, and formal organizations for sustainability have been operating for a significant period of time in Hungary. Organizations in this group represent the traditional green associations and operate under professional processes, usually with one or more employees. The oldest organization in the sample was established 27 years ago, while the youngest one has a 10-year history. All organizations from the first wave of the study belong to this group. These organizations are well-known amongst Hungarian sustainability experts and often play an important role in the whole sphere with their information-sharing activities, workshops, and conferences. In regard to their fields of operation, certain communities focus on single fields (such as energy, food, waste) while others have multiple interests. There is a common feature in their operations: every community in this group can be considered as a relational community with headquarters in Budapest and often with cross-border connections through international networks. However, not all of these organizations dedicate their operations directly and explicitly to sustainability aims, although all of them are aware of the environmental relevance and impacts of their work. Representative of this, a well-known cycling advocacy organization made the following statement: “Our aim is to make cycling more popular in Hungary. Riding a bicycle is more than the activity itself, it is also about all the social benefits we can gain with it. Cities became more livable, more secure, and healthier” (Interviewee 17).

Small, single-issue organizations are represented by young organizations in our sample that are not members of regular international collaborations but may have occasional connections to international groups. These communities are based on shared values and identity and, according to our findings, can be characterized as having a visionary leader or leaders whose expertise defines the field of operation. Representative of this, a sustainable-fashion focused organization said the following: “We both graduated as art and design managers… and wanted to have our own self-initiated project that has a positive impact on Budapest’s life and economy, on the well-being of people and on us” (Interviewee 16). The significance of the leader in these organizations is well-illustrated by the following statement from a community leader: “I am one of the engines [of the organization]. This is my life and my work at the same time” (Interviewee 4). We found only relational-based communities in this group that considers community building important. As an initiator of a community workshop stated: “My goal was to have a place [in the district] where people can sit down without being obliged to consume [to purchase] something and the possibility to have a conversation … I had a lots of bicycle parts that had become dusty and unused, and I wanted people to use them” (Interviewee 10).

Glocal movements have a clear relation to global-perspective ideologies and activism, but their operations are tailored to the local environment. As a result, they combine the characteristics of global and local organizations. Climate activists are emblematic representatives of this category. These communities typically started as local bottom-up organizations and have created the local version of a global organization in recent years. The connection to the global sphere is not necessarily strong, but some connection between local and global counterparts exists, for example, “it may happen that big climate strike events are organized for different days in Canada or other parts of the world” (Interviewee 8). Glocal movements also want system change in order to tackle social problems. As one member of a glocal movement pointed out: “We don’t like to push people individually to change their lifestyle, but we certainly desire system change” (Interviewee 5). The nature of connections among members in glocal movements tends to be relational and voluntary.

Think-tanks for action organizations in the sample have their day-to-day practices significantly influenced by ideological concerns approached through critical social lenses. They want system change just like glocal movements while experimenting with alternative business mechanisms such as the solidarity economy models and the degrowth approach. Their operations include both theoretical and practical actions, creating a link between the two, while translating theoretical knowledge into action. In relation to the system change perspective, their field of operation relates to multiple fields and complex social-economic questions. As one interviewee mentioned, “I wouldn’t name one single activity but the integration of different activities. We have projects on food sovereignty, housing, and energy production but we integrate all these into a bigger system. This is what matters the most, that we can both ideologically and organizationally create a framework to connect the dots” (Interviewee 6). These communities are also based on relational ties and fully work on a voluntary basis.

Do it together communities in our study represent NCBOs linked to geographical locations. The territorial characteristic of these communities comes from their field of operation, as was the case for the studied urban community gardens, which target people from a certain neighborhood. They operate on a voluntary basis or are supported by the local municipality. These communities focus on a single issue (e.g., food production), and it seems that the sense of belonging to the community is as important to them as the activity itself. One organizer of the studied community gardens put it simply, “our aim is community building” (Interviewee 21). Sustainable living is usually not the main aim for these organizations, but they acknowledge the importance of sustainability.

Interpretation of Community Membership

The belief in the importance assigned to communities is universal for all studied NCBOs. Interviewees emphasized the need for communities and that people want to belong to and connect to groups. Interviewees also mentioned that the significance of community is even more important in the case of sustainability-related activities. The ideas that “we are stronger in communities, … and there is no environmental action without people” (Interviewee 1), and “from the very start we wanted to build a community” (Interviewee 16) were frequently mentioned in the interviews.

In terms of community values and beliefs, it seems that awareness raising is more strongly emphasized by established, professional, and formal organizations, while others are more practical or action oriented. Nevertheless, there are organizations belonging to the prior group that recognize the importance of behavioral actions, stressing that “awareness raising is not behavioral change” (Interviewee 2). Further, there are established, professional organizations—typically with strong international backgrounds—that put effort into building connections with action-oriented communities.

Regarding key community values, established, professional, and formal organizations typically value environmental knowledge and knowledge-sharing, while desiring to influence policymakers and the business sphere. Single-issue small organizations believe in the importance of connecting people and empowerment. These organizations therefore create opportunities (places, events) for people with similar interests to meet while aiming to enable them to solve problems related to specific fields, as exemplified by the comment, “we bring people together and they may learn how to organize a garbage collecting event on their own” (Interviewee 4). It seems that these organizations are highly conscious of their work and share the identity of doing something meaningful together as the most important factor for their operations. Glocal movements think in global systems and believe in the need for system change and the reorientation of current social values regarding how we consume, do business, and care for nature. They trust in a positive change and promote social and environmental justice. They believe in civic engagement; as one interviewee said, “we usually tell people [at our events] that if they want to join another organization that is also fine, what matters most is to support the cause” (Interviewee 5). This system-level thinking also characterizes think-tanks for action communities in our sample. They believe that the concepts of sovereignty and justice are of fundamental importance. Their group identity internalizes the importance of both theoretical thinking and actions. These communities consider shared values as important, noting that, “we need common values and a certain amount of belief that all these things that we do make sense” (Interviewee 6). It is also part of their identity to “question implicit believes and rethink concepts” (Interviewee 22). Do it together communities appeared as community gardens in our study. Accordingly, they value nature and being in harmony with nature. Locality is also important to them, as these communities are strongly embedded in their neighborhood and own a solid place-based identity. As the leader of one garden put it, “we can actively do something for our community, we have the opportunity to join local meetings and influence decisions, for example, about community composting” (Interviewee 23).

Understanding of Sustainability

The NCBOs in our study all have sustainability-related activities. Nevertheless, members and leaders of the studied organizations have different understandings about sustainability that influences what their members learn and experience about this concept. Members of established, professional, and formal organizations are diverse in their understanding about sustainability. In all cases, core members of these organizations can be considered as individuals highly committed to the cause of sustainability. The behavioral change of members toward sustainable living is more evident among their volunteers and less committed members who can learn a great deal about sustainability during their activities. These communities convey the significance of green behavior with different approaches:

Raising environmental awareness is the priority for the organization, and leaders put a strong emphasis on sustainability-related consciousness through events and educational campaigns, as in “awareness-raising was always at the center of our work” (Interviewee 13) and “it is very important to talk about these issues” (Interviewee 3);

Sustainability is at the center of the organization’s activities, but they have moved from the role of awareness raising to the role of supporting behavioral change among individuals, as in “we have had programs to promote behavioral change for 10 years” (Interviewee 2);

They reject the clear so-called green focus and apply alternative concepts such as “we are not a green organization but an eco-theological organization” (Interviewee 19) or moving toward a broader context, such as “we have pretty much moved away from pure environmental issues” (Interviewee 1); and

Environmental awareness can be hidden in the activity of the organization, and as a result, they influence members’ sustainable living through the promotion of the activity itself, such as “cycling is an instrument” (Interviewee 17).

The glocal movements and think-tanks for action organizations in our study are clearly focused on environmental and social justice issues, and they think in systems. Members of these communities wish to take action with the concept of justice at the core. If new members are less conscious at the beginning, they can change their lifestyle due to the influence of others. As one interviewee mentioned, “when I joined the organization, I was not at all [ecologically] conscious, but after a year I have completely changed my mind and have fully altered my lifestyle” (Interviewee 5). If members were aware of environmental problems when they joined these organizations, some transformation may still occur, as in “usually people with high eco-awareness join us, but I think their consciousness about greenwashing has grown” (Interviewee 6).

In the case of the small, single-issue organizations in the sample, their leaders usually have a high level of awareness related to sustainability issues, but members are not necessarily knowledgeable. Nevertheless, as the founder of one organization said, “people inevitably learn about sustainability during our activities, as we always talk about these problems, and they get infected by these ideas” (Interviewee 16). Another influence may derive from community norms; therefore, “everyone experiences some inner transformation” (Interviewee 18).

The studied do-it-together communities primarily focus on their activity, but core members are often ecologically conscious in their behavior. These communities’ commitment toward sustainability is also based on their leaders’ beliefs and activities. They also recognize that their activity itself is a sustainable practice. As one garden member noted, “it is not a main aim here, when I joined eight years ago, I was not motivated by the climate crisis at all, but considering what we are doing here, I truly believe that it helps in the climate fight” (Interviewee 23).

Discussion

In this study we explored the types of NCBOs with sustainability-oriented practices and characterized them into different groups to better understand them. Consequently, we conducted a qualitative analysis for sustainability-related NCBOs and evaluated the power of community and meaning of sustainability for the operation of these communities in an urban context in Budapest. Kennedy (Citation2011) has argued that neighborhood communities organized around sustainability issues can foster the transition toward a sustainable lifestyle both within and outside of the community through knowledge sharing and engagement affirmation. Kennedy (Citation2011) has also suggested that similar groups can exist in many different spheres of life, and this is what our study explored in relation to NCBOs incorporating both territorial and relational communities. Therefore, our approach enables an understanding of NCBOs that is in line with the concept of Middlemiss (Citation2010, Citation2011). Further, the understanding of community-based approaches contributes to the comprehension of local knowledge (Carr and Halvorsen Citation2001) and to the recognition of local needs that can be critical for urban sustainability (Xie and Zhang Citation2021).

The literature differentiates between traditional and new environmental organizations (Hisschemöller and Sioziou Citation2013). Traditional environmental or “green” organizations are described as well-known and more conservative groups (Farnhill Citation2016), and their activities focus on lobbying, creating petitions, and trying to influence the political agenda (Hisschemöller and Sioziou Citation2013). Conversely, new environmental organizations can be characterized by a bottom-up approach, initiating actions themselves, and usually remaining independent of government politics (Hisschemöller and Sioziou Citation2013). Amongst new environmental organizations, social movements are typically mentioned (Hisschemöller and Sioziou Citation2013). Our study had a broader scope and included a wide range of NCBOs whose operations may have potential positive impacts on ecological sustainability. This view of sustainability-oriented practices in the case of NCBOs contributes to the current knowledge about civil society engagement toward sustainability issues. Five different types of organizations—established, professional, and formal organizations; small, single-issue organizations; glocal movements; think-tanks for action; do-it-together communities—were identified based on their organizational characteristics, values, and activities, as well as their local and international embeddedness. We observed that—due to hardships in the civil sector—NCBOs in Budapest may reveal their political orientation but in case of large and heterogeneous communities, they tend to avoid topics related to politics to protect their community.

Compared to quantitative mapping exercises, our results cannot provide a detailed description and typology of community-based organizations. Nevertheless, we used a broad definition and were able to include diverse communities in our study. Instead of a detailed and visualized map, our exercise provided a deep understanding of the topic and also explored how members can join and operate within these communities, as reported by their leaders. Further, the five identified organization types illustrate the diversity of options individuals can find if they have any interest in engaging in sustainability-related activities in Budapest.

The importance of communities for the promotion of sustainability was recognized by representatives of all types of NCBOs in our study. The current research results are thus in line with previous conclusions about the significant role of communities for the transition toward sustainable living (Király et al. Citation2013; Kiss et al. Citation2018). Reid, Sutton, and Hunter (Citation2010) suggested three types of influence (generator, mediator, and propagator) that communities may have on their members. In agreement with these categories, we can confirm that NCBOs shape members’ attitudes toward sustainable behavior, channel norms, and through personal examples and practices, thus helping to believe that they can behave sustainably despite the negative image conveyed by Hungarian governmental communications about civil organizations.

The theoretical implications of the study relate to our qualitative analysis for sustainability-related NCBOs, which enables the understanding of communities sharing fundamental organizational characteristics in Budapest. At the conceptual level, this analysis needs further validation for the theoretical generalization of the results.

The practical implications call for a broad consideration of NCBOs for programs that target members of civil society operating in the field of sustainability. Our results show that civil society—often in the form of community-based organizations—cares and acts in a variety of ways to push the spread of sustainability practices and agendas. Our qualitative data suggest that people join environmental actions and strive for sustainable living in various ways in Budapest. Support for all different kinds of NCBOs can thus serve the transition toward sustainable living. At the same time, our results suggest that if the Hungarian government makes operations of the civil sphere impossible, it can also prevent the spread of the idea of sustainability.

Conclusion

Our study had a clear aim to demonstrate the importance of communities as potential vehicles of social change. Accordingly, our analysis focused on an understanding of communities that goes beyond the differentiation of individual (micro) and social (macro) levels (Reid, Sutton, and Hunter Citation2010). The findings of the empirical study show a blurring of boundaries in the green agenda. The role of new environmental organizations seems to be as important as the role of old, traditional organizations in Budapest. Further, there has been an observable shift in the case of traditional organizations to broaden their horizons and work with complex issues related to social and environmental justice. They are also moving beyond the strict positioning of green organizations and positioning themselves under alternative terms. This may be a consequence of the negative liberal image communicated by the state-funded propaganda about environmental organizations.

Based on our study, we can conclude that the labels “green” and “sustainable” are no longer the exclusive markers for communities with awareness of environmental issues in Budapest. As a result, the boundaries of the green agenda are becoming blurred. Further, communities and sustainability organizations can learn from our results that, through sustainability-oriented practices, they can find many allies and potential cooperators to learn from and to organize politically. The need for joint and coordinated effort is expected to become increasingly vital due to the shrinking space for environmental activism in illiberal Hungary (see Buzogány, Kerényi, and Olt Citation2022). Our study suggests that mainly local, community-based organizations are left to support individuals in their transition toward sustainable living without significant resources provided by the state.

Limitations and Future Line of Research

This study focused only on NCBOs in Budapest. Therefore, a limitation of our study derives from the characteristics of the sample, which was relatively small, nonrandom, and conveniently accessible. This clearly restricts the generalizability of our results. Nevertheless, the qualitative-based study was informative and can support a deeper understanding of the studied phenomenon. In future studies, it would be beneficial to add further organizations to the analysis of non-NCBOs to discover whether additional types of communities exist in relation to the field of sustainability. It would also be interesting to understand the different types of NCBOs in other illiberal countries of the Central and Eastern European region and beyond (e.g., Turkey and Russia).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the interviewees and members of the research team for their commitment to the project and their continuous intellectual support. We would like to thank the reviewers for all of their valuable comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Austin, J. E., and M. M. Seitanidi. 2012. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41 (6):929–68. doi:10.1177/0899764012454685.

- Bozóky, A. 2018. The shadows of ‘illiberal democracy. In Proceedings of 5th ACADEMOS Conference 2018, ed. A. Taranu, 63–72. Bologna: Filodiritto.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Buzogány, Á. 2015. Representation and participation in movements. Strategies of environmental civil society organizations in Hungary. Comparative Southeast European Studies 63 (3):491–514. doi:10.1515/soeu-2015-630308.

- Buzogány, A., S. Kerényi, and G. Olt. 2022. Back to the grassroots? The shrinking space of environmental activism in illiberal Hungary. Environmental Politics 31 (7):1267–88. doi:10.1080/09644016.2022.2113607.

- Carr, D. S., and K. Halvorsen. 2001. An evaluation of three democratic, community-based approaches to citizen participation: Surveys, conversations with community groups, and community dinners. Society & Natural Resources 14 (2):107–26.

- Crowther, D., and S. Cooper. 2002. Rekindling community spirit and identity: The role of ecoprotestors. Management Decision 40 (4):343–53. doi:10.1108/00251740210426330.

- Farnhill, T. 2016. The characteristics of UK unions’ environmental activism and the agenda’s utility as a vehicle for union renewal. Global Labour Journal 7 (3):3. doi:10.15173/glj.v7i3.2536.

- Fine, G. A. 2012. Group culture and the interaction order: Local sociology on the meso-level. Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1):159–79. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145518.

- Fridays For Future. 2019. ’Klímatüntetés – 2. hét’. [Climate Protest – 2. week] (accessed August 23, 2022). https://www.facebook.com/events/1219390811564326/?acontext=%7B%22event_action_hist ory%22%3A[%7B%22surface%22%3A%22page%22%7D]%7D

- Gusfield, J. R. 1978. Community: A critical response. Oxford: HarperCollins.

- Haanpaa, L. 2007. Structures and mechanisms in sustainable consumption research. International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development 6 (1):53–66. doi:10.1504/IJESD.2007.012736.

- Heller, K. 1989. The return to community. American journal of Community Psychology 17 (1):1–15. doi:10.1007/BF00931199.

- Hisschemöller, M., and I. Sioziou. 2013. Boundary organisations for resource mobilisation: Enhancing citizens’ involvement in the Dutch energy transition. Environmental Politics 22 (5):792–810. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.775724.

- Hofmeister-Tóth, Á., K. Kelemen, and M. Piskóti. 2012. Life paths in Hungary in the light of commitment to sustainability. Interdisciplinary Environmental Review 13 (4):323–39. doi:10.1504/IER.2012.051449.

- Jamšek, S., and B. Culiberg. 2020. Introducing a three-tier sustainability framework to examine bike-sharing system use: An extension of the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Consumer Studies 44 (2):140–50. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12553.

- Kennedy, E. H. 2011. Rethinking ecological citizenship: The role of neighbourhood networks in cultural change. Environmental Politics 20 (6):843–60. doi:10.1080/09644016.2011.617169.

- Király, G., G. Kiss, A. Köves, and G. Pataki. 2013. Nem növekedés-központú gazdaságpolitikai alternatívák: a fenntartható életmód felé való átmenet szakpolitikai lehetőségei [Degrowth economic policy alternatives: Policy options for the transition to a sustainable lifestyle]. Budapest: Nemzeti Fenntartható Fejlődési Tanács Titkársága.

- Kiss, G., G. Pataki, A. Köves, and G. Király. 2018. Framing sustainable consumption in different ways: Policy lessons from two participatory systems mapping exercises in Hungary. Journal of Consumer Policy 41 (1):1–19. doi:10.1007/s10603-017-9363-y.

- Krasznai Kovács, E. K., and G. Pataki. 2021. The dismantling of environmentalism in Hungary. In Politics and the environment in Eastern Europe, ed. E. Krasznai Kovács, 25–52. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers.

- Krasznai Kovács, E. 2021. Introduction: Political ecology in Eastern Europe. In Politics and the environment in Eastern Europe, ed. E. Krasznai Kovács, 1–24. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers.

- Lusch, R. F., S. L. Vargo, and A. Gustafsson. 2016. Fostering a trans-disciplinary perspectives of service ecosystems. Journal of Business Research 69 (8):2957–63. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.028.

- Middlemiss, L. 2010. Community action for individual sustainability: Linking sustainable consumption, citizenship and justice. Managing Environmental Justice 62:71–91.

- Middlemiss, L. 2011. The power of community: How community-based organizations stimulate sustainable lifestyles among participants. Society & Natural Resources 24 (11):1157–73. doi:10.1080/08941920.2010.518582.

- Mikecz, D., B. Böcskei, and Z. Vasali. 2022. A Magyar jobboldal (ellen)keretei a klímaválságra és-mozgalomra [Hungarian right-wing (counter)frames for the climate crisis and the climate movement]. In Éghajlatváltozás és klímapolitika ed. D. Mikecz and D. Oross, 158–82. Budapest, HU: Napvilag Publisher.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. London: SAGE.

- Murphy, R. H. 2018. The best cases of “actually existing socialism”. The Independent Review 23 (2):283–95.

- Naz, F., J. Oláh, D. Vasile, and R. Magda. 2020. Green purchase behavior of university students in Hungary: An empirical study. Sustainability 12 (23):10077. doi:10.3390/su122310077.

- Reid, L., P. Sutton, and C. Hunter. 2010. Theorizing the meso level: The household as a crucible of pro-environmental behaviour. Progress in Human Geography 34 (3):309–27. doi:10.1177/0309132509346994.

- Spash, C. L., and K. Dobernig. 2017. Theories of (un)sustainable consumption. SRE – Discussion Papers 04. Vienna: WU Vienna University of Economics and Business. (accessed September 20, 2021). http://www-sre.wu.ac.at/sre-disc/sre-disc-2017_04.pdf.

- Suri, H. 2011. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal 11 (2):63–75. doi:10.3316/QRJ1102063.

- Svendsen, E. S., L. K. Campbell, D. R. Fisher, J. J. Connolly, M. L. Johnson, N. F. Sonti, D. H. Locke, L. M. Westphal, C. L. Fisher, J. M. Grove, et al. 2016. Stewardship mapping and assessment project: A framework for understanding community-based environmental stewardship. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. (accessed August 23, 2022). https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cures_pub/7/.

- Xie, L., and J. Y. Zhang. 2021. Just sustainability’ or just sustainability? Shanghai’s failed drive for global excellence. Society & Natural Resources 34 (4):449–66. doi:10.1080/08941920.2020.1843745.

Appendix

Table A1. Key interview questions.