Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study is to demonstrate whether the implementation of standardized Peer Assisted Learning (PAL) suturing workshops can aid the attainment of a technically competent interrupted suturing technique by medical students.

Materials and Methods:

The European University Cyprus (EUC) Division of Surgery and the students of the EUC Surgery Club compiled a standardized 1 hour and 15 minutes suturing workshop. During a one-week period 14 peer-teacher school of medicine students trained 147 fellow students. At the end of each workshop the students were assessed for the learning outcome of simple interrupted suturing with instruments by two peer-teachers, with the use of a standardized scoring rubric. The workshop primary outcomes were the rubric score and the time to complete a suture. These were correlated to student characteristics such as sex, year of studies, prior experience in suturing, previous participation in a similar workshop, previous training at home or in a hospital, and an interest in pursuing a surgical career. Univariate and multivariate statistical analysis was performed.

Results:

Statistical analysis showed that gender and previous suturing experience did not impact the rubric score of students, nor the time required. The student year of studies, having recently passed the course of General Surgery and having interest to pursue a surgical specialization positively affected the students’ score.

Conclusions:

Surgical peer teaching provided an effective method of teaching of the simple interrupted suturing technique. Interest in surgery, previous workshop experience and having recently completed the general surgery module helped students score higher in the assessment.

Introduction

There has been evidence, that medical students are graduating from medical schools without obtaining the expected surgical skills and that there is a risk of incompetency in performing basic surgical skills from newly qualified physicians [Citation1, Citation2]. This comes in contrast with the fact that Medical school curricula have implemented targeted training in practical procedures and surgical skills [Citation3]. A professional and competent junior doctor should be familiar providing basic interventional skills [Citation4–6]. Specifically, basic surgical skills, surgical scrub-in, correct use of personal protective equipment, use of local anesthetics and skin suturing are some of the necessary skills every junior physician is expected to have irrespective of their future specialty [Citation3].

Peer-assisted learning (PAL) in medical education involves senior students teaching junior students. Evidence suggests that PAL may be beneficial in the teaching of surgical skills, such as suturing [Citation7, Citation8]. PAL has been proven mutually beneficial both for the students and the peer-teachers in other tutoring settings as well. On one hand, junior medical students feel more comfortable in a less formal setting without a rigid hierarchical structure. This makes the learning process less stressing and may motivate students to spend more effort in practicing the instructed skills. On the other hand, students that act as peer teachers benefit from both the preparation process and the execution of a peer-taught session with the better acquisition of knowledge, through verbalization of the material to their peers and repetition [Citation9, Citation10].

The limitations of PAL lie in the concern that peer teachers may lack the educational and technical skills required for teaching other students. Additionally, doubts are expressed concerning the successful delivery and assessment of learning outcomes by peer teachers. However, these problems may be addressed by setting specific goals, educating the peer teachers, and following a structured approach. This study tests the hypothesis that PAL may be used successfully to instruct the technique of simple interrupted sutures to medical students.

Materials and methods

Study objectives

The primary objective of the study was to assess if peer teaching can be effectively used to teach the skill of simple interrupted sutures with instrument knot tying. Secondary objectives were to identify student related factors that influence the success of learning the simple interrupted suturing technique in a standardized workshop.

Study design and setting

The study was designed using the PICO framework. The study population were medical students from the first until the fifth year of their medical studies at the EUC School of Medicine. All students who were members of the Surgery Club were invited to the workshop. Furthermore, an invitation was sent out to students that were not involved in the Surgery Club. There were no prior essential criteria for the workshop, hence making it widely available. Students of years one to three are in the preclinical phase of the curriculum and have a lab and simulation-based training with minimal exposure to hospital training. Students of years four and five are in the clinical phase of the curriculum with a hospital rotation program.

The peer-teachers were 14 students from the fourth, fifth and sixth year of medical studies. The students who acted as peer teachers had prior experience in peer-teaching for a minimum of one semester in anatomy and clinical skills labs. All the peer teachers had previous experience in the simple interrupted suturing technique by receiving training in similarly structured workshops delivered by faculty members. In preparation of the workshop, peer teachers underwent training from an academic surgeon of EUC faculty (DN) in a Train the Trainers session. This session included the participation of the peer-teachers as students in the workshop and their evaluation with the workshop assessment tools.

The intervention was a multimedia modular task training workshop created by EUC faculty members and EUC Surgery Club’s student peer-teachers with the aim of teaching suturing skills to medical students. The workshop included an electronic booklet, video demonstrations, a PowerPoint presentation and one hour and fifteen minutes of hands-on practice session. The teaching methodology followed Peyton’s 4-Steps-Approach with steps 1 (demonstration) and 2 (deconstruction) delivered by an electronic booklet and video recordings made available online prior to the workshop. The skill of suturing was broken down to basic elements: instrument handling, needle arming and handling without touching the needle, passing of the needle through the skin at a right angle with wrist rotation, and knot tying with needle holder. Steps 3 (comprehension) and 4 (execution) were delivered through hands-on practice performed on a synthetic skin model with the use of a standardized suturing kit. After consecutive training of these elements during the workshop, the students were asked to perform simple interrupted sutures on simulated lacerations.

The performance of students participating in the workshop was compared to that of the peer teachers. In addition, students were stratified according to their year of study and compared to students of different years. Last, students with previous experience in suturing were compared with those students who declared that they had never received any training in surgical suturing.

Outcomes measured

An electronic questionnaire was completed by the participants before the workshop to establish the student’s prior suturing experience and potential interest in a surgical specialization. Previous experience in suturing was recorded as any of the following: participation in a suturing workshop, training at a hospital, self-training at home. Students were assessed by two peer teachers with a standardized rubric assigning a grade on a scale from 1 to 10 depending on the number of steps that were completed without any mistake (Addendum 1). The rubric score and the time required to perform a simple interrupted suture were recorded for each student during the assessment phase of the workshop and were used as performance indicators.

Ethics

The Institutional Review Board of the EUC provided study approval. The study was carried out according to the Helsinki Declaration and Cyprus Law and all personal data protection policies were consistent with GDPR/Personal Data Protection Commissioner.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported with their mean values and standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables are expressed with counts and percentages. The Chi-Square test or Fisher exact test were used to compare the frequencies of categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using two-sample t-test and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s correction for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Spearman’s rho was used to examine correlations between variables. A multivariate logistic regression model with the enter method, was used to investigate the probability of a student obtaining a rubric score equal or greater than 9 out of 10. This cutoff value was calculated from the peer-teachers’ average score of 9.9 after deducting 2.5 * SD and then rounding and was set as a benchmark of excellence. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed with JASP for Windows (Version 0.14.1, JASP Team, University of Amsterdam, NL).

Results

Participant demographics

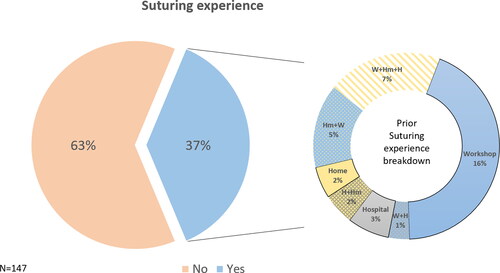

A total of 147 medical students from Year 1 to Year 5 participated in the current study. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in . The majority of students who participated in the training were of the preclinical years representing 80.3% of the population, while clinical-year medical students of fourth and fifth years represented 19.7% of the total participants. There were 56 students with previous suturing experience representing 37.8% of the study population. The highest percentage of previous experience in suturing per year, was observed in the 3rd (73.5%) and 5th year (72.7%) students, followed by the 4th (61.1%), 2nd (15.8%) and 1st (10.9%) year students. The student year of studies had a positive correlation with prior experience in suturing (rho= 0.519, p < 0.001). The type of prior suturing experience is depicted in . One hundred and thirty of the 147 students (87.8%) expressed an interest in pursuing a surgical career in the future. There was no variation of the interest in a surgical specialization across the years of study.

Figure 1. Workshop participants’ prior suturing experience (left pie chart), and type of suturing experience breakdown (right doughnut chart). W: workshop, H: hospital, Hm: home training.

Table 1. demographic data.

Workshop results

All participants succeeded in performing simple interrupted sutures with instrument knot tying at the end of the workshop. On average, students completed without any mistake 8.4 out of 10 steps (SD = 1.6) of the scoring rubric. The average time to perform a simple interrupted suture was 122.9 seconds (SD = 41). In comparison, the peer-teacher students had obtained on average a higher rubric score with 9.9 out of 10 steps (SD= 0.3), (p = 0.001) and performed simple interrupted suture in a comparable average time of 106.5 seconds (SD= 37), (p = 0.18).

Analysis of factors affecting student performance

The student performance was assessed for the following factors: student sex, interest in pursuing a surgical specialization, year of studies, and prior suturing experience. Student sex, and prior suturing experience did not affect the student’s rubric score, nor the time needed to perform sutures. However, students interested in a surgical specialization had an average score of 8.5 (SD= 1.5) which was higher than the score of 7.4 (SD= 2.0) obtained by students not interested in surgery (p = 0.006). In addition, students who had participated in the past in similar workshops completed a suture on average in 108.6 sec (SD = 31.1) while those without similar experience needed 129.3 sec (SD= 43.3), (p = 0.004). The student’s year of study affected both the rubric score and the time needed to complete a suture, with first year students having on average lower performance scores and longer times needed to perform sutures when compared with students of other years. These results are summarized in .

Table 2. Workshop performance in relation to student characteristics.

Multivariate analysis

According to the results of the univariate analysis, the student year of studies, the interest in a surgical specialization and the time required to perform a suture were used as independent factors for a logistic regression analysis to investigate their effect on student performance. The multivariable analysis showed that interest in a surgical specialization (OR 3.946, 95%CI = 1.137 to 13.688, p = 0.031), being a third-year student (OR 2.997, 95%CI = 1.028 to 8.741, p = 0.044) and being a fourth-year student (OR 6.278, 95%CI = 1.440 to 27.371, p = 0.014) had independent associations with getting a rubric score ≥ 9. For each second increase of the time taken to perform a suture there was a 0.8% decrease in the odds of getting a rubric score ≥ 9 (OR 0.982, 95%CI = 0.971 to 0.993, p = 0.001) ().

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of student factors predicting a Rubric score ≥ 9.

Discussion

There have been acknowledged concerns that newly qualified physicians are graduating with substandard basic surgical skills knowledge [Citation1, Citation2]. Taking these in consideration and on the basis that doctors across all fields of medicine should be capable of performing basic surgical skills, a need for improvement arises. Peer-assisted learning (PAL) has been proposed as a potential medium through which students can improve their technique [Citation7, Citation8]. This study assessed the effectiveness of teaching simple interrupted sutures with instrument knot tying from senior medical students to their younger peers under consultant supervision. The results revealed that all participants completed the workshop successfully with achievement of a high average score by the participants (8.4/10, SD = 1.6). Nevertheless, the participants’ average score was significantly lower than the average score of the peer teachers indicating that there was room for improvement. High performance of participants was also demonstrated in the time needed to complete successfully a simple interrupted suture which was on average comparable to the time of their peer teachers. These two outcomes show that the workshop was successful in teaching participants how to perform simple interrupted sutures in an appropriate and time efficient manner.

Student-related factors that influence the success of learning were also identified. Factors such as the year of studies, and interest to follow a surgical specialization significantly affected the student performance where others such as the student sex, and prior suturing experience did not have a similar effect. Interestingly, the participants who had expressed interest in a surgical career in the pre-workshop questionnaire (87.8%), were much more likely to have a rubric score of 9 or higher (OR = 3.946, p = 0.031). In this regard, it can be implied that student motivation is a major factor in their performance. Previous studies support this finding, showing that student interest in surgery did influence early laparoscopic performance in FLS peg transfer task and led to simple interrupted suture skill improvement [Citation11, Citation12]. Moreover, it should be noted, that prior suturing experience was not affected by motivational status and there wasn’t any difference based on motivation between students of different year of studies and different sex. There was a positive correlation between the year of study and the existence of prior suturing experience. However, the prior suturing experience does not increase linearly with the year of studies, with the students of the 1st and 2nd year having the lowest percentage of prior suturing experience, while students of the 4th, 5th and 6th year had comparable prior suturing experience To avoid collinearity, previous suture experience was excluded from the multivariate analysis, and only the student year of studies was included as a factor in the model. Males had a tendency to complete a simple suture in a shorter time but both sexes had similar rubric scores. Our study demonstrated that gender did not affect the outcome of the evaluation contradicting previous studies that demonstrated male medical students outperforming their female colleagues [Citation13]. Substantial evidence has been provided by recent studies, proving an increasing trend of female doctors to pursue a career in the field of surgery [Citation14–18]. Encouragingly, in line with this evidence, female students had a higher participation rate than male students in these surgical workshops (57.1%), and 85.7% of them did express interest in pursuing a surgical career.

When examining the performance of the students in association with the year of studies, the third and fourth-year students achieved the highest rubric scores. Comparing the times of the third and fourth-year students to that of the first-year students, the former group recorded significantly faster times, which can be attributed to lack of practice of the latter ones, who stated that only 10.9% of them had relevant previous experience. It should be noted that the first-year students had not yet participated in clinical skill training labs or simulation labs during their medical studies and this lack of familiarity with the methodology of an intensive workshop may have been an obstacle to their performance. This may also explain why the 2nd year students whose rate of prior suturing experience was comparable to that of the 1st year students had a higher average a Rubric score which was comparable to that of the 5th year students.

Fifth-year students had a small decline in the performance of the rubric. The unexpected decline in the dynamics of performing the task by the fifth-year students can be attributed partly by the fact that the third- and fourth-year students had a more recent exposure and training in the curricular course of General Surgery, in which suturing workshops are included. Interestingly, the time required to perform a suture by the fifth-year students, was shorter, yet on the expense of a lower rubric score.

Another interesting point is that neither the rubric score, nor the time needed to make a suture were affected by student prior experience in suturing which varied from training at home and hospital to training at suturing workshops. This outcome can be related to the fact that such previous experience was not homogenous among participants and might have followed a slightly different format or methodology from the workshop conducted by the authors.

The multivariate analysis also indicates that students who perform sutures faster in this workshop, achieve this through improved efficiency of their technique as for each second that they were faster, their chances of getting a Rubric score equal or higher than nine increased. Both the univariate and multivariate analysis suggest that the workshop has its highest efficiency for students that had a formal suturing workshop no more than a year ago and who are interested in following a surgical specialization. As such this workshop may be at its highest efficiency as a refresher course.

Limitations

This study is limited by its non-randomized design. Sample size was small and consisted only of students from a single university in Cyprus, which can lead to selection bias, however to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the largest peer-assisted surgical skills workshop for undergraduates that has been undertaken in Cyprus. The scoring rubric designed and used needs to be further assessed for its reliability and validity as a surgical skills assessment tool. Furthermore, the relative lack of experience of the peer teachers may be a source of assessment bias by the peer-teachers. The focused and structured format of the workshop reduced the risk of heterogeneity in the teaching methodology used by the peer teachers and compensated for the lack of direct supervision and relative inexperience of the course instructors. Students who applied were all members of the EUC student Surgery Club and may have an above average interest in surgery, a fact that may introduce selection bias to the study. Nonetheless, authors aimed at making the workshop widely available to all students with a simple application process, without any prior essential criteria been set. Further studies are required for both the assessment of long-term knowledge retention attained during PAL surgical skills courses and the objective measurement of transference of the gained skills into clinical practice. GDPR related obstacles didn’t not allow us to video record and store the student assessment for post workshop evaluation.

Conclusion

Peer-assisted learning can be effective as a means of teaching simple interrupted sutures, provided that a standardized-structured and focused workshop is implemented. First year students without any previous experience benefit the less when compared to students who have had already gained some kind of suturing experience either in previous workshops, or during clinical practice. Motivation to follow a surgical specialization significantly improved students’ outcomes during this workshop. Lastly, it seems that the retention of a specific skill by a student can deteriorate if repetitive targeted training of the skill is not performed.

Core competencies

Patient Care (PC), Medical Knowledge (MK), Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). All primary data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- Bennett SR, Morris SR, Mirza S. Medical students teaching medical students surgical skills: the benefits of peer-assisted learning. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1471–1474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.03.011.

- Davis CR, Toll EC, Bates AS, Cole MD, Smith FCT . Surgical and procedural skills training at medical school: a national review. Int J Surg. 2014;12(8):877–882. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.05.069.

- General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors Education Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education. 2022. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/standards-and-outcomes/outcomes-for-graduates.

- Chipman JG, Acton RD, Schmitz CC. Developing surgical skills curricula: lessons learned from needs assessment to program evaluation. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(3):133–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.03.032.

- Croft SJ, Kuhrt A, Mason S. Are today’s junior doctors confident in managing patients with minor injury? Emerg Med J. 2006;23(11):867–868. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.035246.

- Kneebone RL. Twelve tips on teaching basic surgical skills using simulation and multimedia. Med Teach. 1999;21(6):571–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599978988.

- Saleh M, Sinha Y, Weinberg D . Using peer-assisted learning to teach basic surgical skills: medical students’ experiences. Med Educ Online. 2013;18(1):21065. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.21065.

- Dubrowski A, MacRae H. Randomised, controlled study investigating the optimal instructor: student ratios for teaching suturing skills. Med Educ. 2006;40(1):59–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02347.x.

- Elloy M, Sama A. Does an ENT introductory course improve junior doctors’ confidence in managing ENT emergencies? Bulletin. 2010;92(9):1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1308/147363510X528401.

- Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546–552. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701583816.

- Kolozsvari NO, Andalib A, Kaneva P, et al. Sex is not everything: the role of gender in early performance of a fundamental laparoscopic skill. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(4):1037–1042. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1311-8.

- Vanyolos E, Furka I, Miko I, Viszlai A, Nemeth N, Peto K. How does practice improve the skills of medical students during consecutive training courses? Acta Cir Bras. 2017;32(6):491–502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-865020170060000010.

- Ali A, Subhi Y, Ringsted C, Konge L. Gender differences in the acquisition of surgical skills: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(11):3065–3073. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4092-2.

- Lou Z, Yan F, Zhao Z, et al. The sex difference in basic surgical skills learning: a comparative study. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(5):902–905. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.04.002.

- Linscheid LJ, Holliday EB, Ahmed A, et al. Women in academic surgery over the last four decades. Koniaris LG (ed). PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243308.

- Pories SE, Turner PL, Greenberg CC, Babu MA, Parangi S. Leadership in American surgery: women are rising to the top. Ann Surg. 2019;269(2):199–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002978.

- Shin SH, Tang GL, Shalhub S. Integrated residency is associated with an increase in women among vascular surgery trainees. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71(2):609–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.03.043.

- Ryan JF, Istl AC, Luhoway JA, et al. Gender disparities in medical student surgical skills education. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(3):850–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.09.013.