ABSTRACT

This article explores older peoples’ perceptions of menopause and sexuality in old age. The research was exploratory, consisting of 12 vignette-based focus group discussions and 18 face-to-face semistructured interviews among older Yoruba men and women (60+). Findings revealed menopause as a biopsychosocial marker of aging that provides gendered spaces for women to abstain from or suppress their sexual desires and avoid a folk pregnancy- oyun iju(folk fibroid). Older men construe menopause and sexual refusals from their wives as opportunities for extramarital relations. Thus, both older men and women have differentiated perceptions and dispositions toward menopause, which have implications for their sexual health and well-being.

Ile obinrin kii pee suu [The night comes early for a woman] (A common Yoruba saying).

Introduction

Menopause, a product of bodily changes, is one of the critical biopsychosocial markers that come with enormous implications for women’s aging experiences and their relationships, including those relating to their sexuality. Each woman enters the stage of menopause at different periods of their life spans, but an average woman can experience menopause between 45 and 60+ years (Rabiee, Nasirie, & Zafarqandie, Citation2014).

Experiences around menopause vary among women, and factors such as differences in cultural values, relationships, and support network are critical. Women and men form their experiences and impressions about events through social interactions within a network of structures (Greifeneder, Bless, & Fiedler, Citation2018). Within this network of relations, the socialization process stands out in shaping how individuals and social categories acquire different experiences across the life span (Hunt, Citation2017). As a process, socialization provides various frameworks for social actors to inculcate and interrogate personal concerns, including those related to their health and their relationships with others. As such, the process allows social actors to figure what reactions and interpretations are appropriate to them and others (Hunt, Citation2017).

As women grow older and enter menopause, their reactions and approaches to managing the consequences on their sexuality and relationships also change. In this sense, older men and women are socialized into different ways to construe and respond to bodily changes that come with age, which includes menopause for women. Ayers, Forshaw, and Hunter (Citation2010), through a systematic review of evidence, argued that women react differently to the process and adopt different measures in coping with the challenges. Their findings showed that psychosocial factors are important in how women cope with the challenges of menopause. Their analysis revealed that the menopausal stage at which a woman was, their attitudes, and that of their partners, as well as the quality of support from medical systems, are important determinants. In reality, women differ in all these dimensions and as such have demonstrated varied experiences and reports around the influence of psychosocial factors on their menopausal experiences (Ayers et al., Citation2010).

Women across different cultural settings have attached different meanings and interpretations to menopause (Greifeneder et al., Citation2018; Thorpe, Fileborn, Hawkes, Pitts, & Minichiello, Citation2015). Similar evidence also exists on how the phenomenon of menopause impacts women’s sexual lives and that of their partners. Drawing from the experiences of 12 British women who were in their menopausal stage, Hinchliff, Gott, and Ingleton (Citation2010) argued that pain was present during sexual engagements and that menopause causes some psychological challenges for the women. However, some of the women interpreted the pain and associated stress of going through the experience as manageable and temporal. The place of long-term preparation and support from partners emerged as critical in the narratives of the women. Menopause comes with challenges that require prior planning, including the possible implications on the relationships of the women going through the process. As opined by Higgs and Jones (Citation2009, p. 82), women who have been found to cope well with menopausal challenges are those who have developed healthy attitudes and enjoyed the support of their partners or spouses.

Dispositions and reactions toward menopause and the possible implications for sexual relationships are inseparable from sociocultural beliefs and values (Davina, William, & Suzanne, Citation2007; Ward, Mandville-Anstey, & Coombs, Citation2019). Studies have shown that menopause has different meanings among men and women, and such interpretations have implications for their sexuality and the available support to cope with menopause (Cid Quirino, Komura Hoga, & Lima Ferreira Santa Rosa, Citation2016; Tshitangano, Maluleke, & Tugli, Citation2015). In Indonesia, for instance, Kartini and Hikmah (Citation2017), through a qualitative study among menopausal women, revealed that women must be submissive to their husbands, including their demands for sex. Conformity to this social obligation is considered as rewarding and a mark of womanhood. With age, the women argued that sexual intercourse becomes painful. However, such pain is rationalized as normative and inevitable in the postreproductive age. As such, most of the women expressed their willingness to sustain the social expectations of providing the needed emotional support and comfort for their partners. In this regard, the women described menopause as their destiny and that the pain and stress that sometimes occur during sex as fulfilling their womanhood obligations. It is noteworthy that a few women in the Kartini and Hikmah (Citation2017) study differed from the submissive position of other women. A few of those who differed contested the social expectation that menopause should not be an event to deny sexual demands from their husbands. Women in this latter category felt menopause was a legitimate reason to avoid sexual intercourse as an act of obligation to their partners. The findings from Hinchliff et al.’s (Citation2010) study in the UK and that of Kartini and Hikmah (Citation2017) in Indonesia echo cultural divergence, the values placed on the woman’s body, sexual rights, and possible implications of menopause on sexual behaviors in later life.

Conforming or deviating from the normative views and expectations around the woman’s body and sexual activities has some implications that transcend themselves and shape their relationships with others. Thus, Higgs and Jones (Citation2009, p. 82) called for a contextual understanding of these variations, as they have relevance in addressing sexual rights and well-being challenges in later life. Evidence from the gerontological literature in Africa shows the critical need for such understanding. For instance, some of the findings from a qualitative study among rural women in Limpopo, South Africa (Ramakuela, Akinsola, Khoza, Lebese, & Tugli, Citation2014) revealed how misconceptions are denying older women the legitimacy to seek professional care when they are faced with a postreproductive health challenge. Denunciation often trail engaging in sexual intercourse or contraction of a sexually transmitted infection among older women. In the South African context, older women who continued to engage in sex in menopause would develop some abdominal problems and illnesses that could not be medically explained (Ramakuela et al., Citation2014). Similar misconceptions have also been reported by Ibraheem, Oyewole, and Olaseha (Citation2015) in a mixed method study in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. The study consisted of eight focus group discussions and 245 survey respondents among women aged 46 to 69 years. Results from the quantitative component of the study showed the existence of positive attitudes toward menopause among about 50% of the respondents. Nonetheless, more than two-thirds held the view that menopausal women were prone to sickness when they have sex (Ibraheem et al., Citation2015). The misconceptions around menopause and sexual activities were further confirmed in the qualitative findings, as most of the participants felt sexual intercourse when possible sometimes could lead to some strange sicknesses.

Despite the possible implications of this misrepresentation on sexual behavior of older men and women, the gerontological literature has been occupied with studies looking at men’s conception and disposition toward menopause (Jaber, Khalifeh, Bunni, & Diriye, Citation2017; Reale Caçapava Rodolpho, Quirino, Akiko Komura Hoga, & Lima Ferreira Santa Rosa, Citation2016). Men form a critical source of support in helping their women to cope with some of the challenges associated with menopause (Reale Caçapava Rodolpho et al., Citation2016). They are also crucial in reducing the influence of menopause on the sexual health of older women (Wong, Huang, Cheung, & Wong, Citation2018). Nonetheless, the gerontological literature is lacking in studies focusing on older men’s perceptions of menopause and the possible influence on the values on sexuality in old age.

An understanding of older men and women’s perceptions and dispositions is necessary, judging by the evidence on the sexualization of the woman’s body and the premium on sexual pleasures and heterosexuality in intergenerational sexual relationships. In most African countries, the dominance and normativity of heterosexual relations with younger women are well enshrined in the practice of polygyny (Jacoby, Citation1995; Mabaso, Malope, & Simbayi, Citation2018; Ramakuela et al., Citation2014). Sexual relations within such marriages are driven by rivalry and competition among wives, with younger women commanding higher value due to the high premium on procreation (Isiugo-Abanihe, Citation1994; Rossi, Citation2016). Older wives, especially those in their menopausal age, attract lesser attention from their husbands except in other spheres where seniority takes dominance over perceived sexual value. Within these settings, older men who have the social capital would attract younger women for sexual relations, while older women might prefer to suppress their sexual desires or refrain from sexual activities even when they have the potential to engage in sex (Jacoby, Citation1995; Mabaso et al., Citation2018; Ramakuela et al., Citation2014; Rossi, Citation2016). What then are the possible implications of such dispositions on older men’s conception of menopause, sexual activities, and rights to the woman’s body within patriarchal settings? An online study among 44 women aged 38 to 68 years revealed that older women could sometimes be engaged in risky sexual behavior. The decision to engage in risky sexual behaviors was associated with relational issues such as commitment and the lack of understanding with their partners (Emmers-Sommer & Walker, Citation2017). Similar findings have also emerged from a qualitative study among menopausal women in China (Davina et al., Citation2007). The participants argued that sexual disharmony with their spouses affected their sexual relationships and partner’s commitment. The study also showed that cultural expectations around sexuality and aging positioned both older men and women differently within the study settings, and this has implications on their sexual behaviors (Davina et al., Citation2007).

The gerontological literature in Africa lacks evidence on how older men and women consider menopause as an embodied reality in defining or denying their sexual needs and rights in later life. Studies are needed in this direction given the possible implications of cultural beliefs and values in widening the unmet sexual and postreproductive health needs of older people. Hence, this article explores the perceptions and experiences of older men and women on menopause and their conceptions of the woman’s body within an urban space in Ibadan, Nigeria. The article is guided by a constructivist interpretative approach that focuses on reality as interpreted by the social actors involved.

Contextual and interpretative understanding of the intersections between sexuality and aging has excellent potential in advancing evidence and theories. Earlier, González (Citation2007) pointed out that norms and cultural expectations around bodily changes in women could create ripple effects on dispositions and orientations toward heterosexual relations. By extension, we presume that misconceptions around menopause, sexual refusals, and denial of sexual rights in old age could provide motivations for engagement or nonengagement in pleasurable, nonrisky, and risky sexual behaviors among older men within our study context. Our presumption aligns with the existence of diverse cultural values and meanings around bodily changes, sexual behaviors, pleasures, and performance (Davina et al., Citation2007; Emmers-Sommer & Walker, Citation2017; Tshitangano et al., Citation2015; Ward et al., Citation2019). Against this backdrop, the article draws attention to the dominant and marginal normativity and contestations controversies around menopause, sexual obligations, and rights to sexual activities in old age. The article focuses on how cultural beliefs around the woman’s body, menopause, and sexual obligations in marital relationships influence sexual behaviors and sexual rights in old age within the Yoruba context in Southwest Nigeria.

Method

Design

This article draws from a more extensive study on sociocultural constructions of sexuality and help-seeking behavior among older Yoruba people in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria (Agunbiade, Citation2016). The study was informed by a sequential exploratory mixed-method design that entails collecting and analyzing qualitative and quantitative data in a single study (Hesse-Biber, Citation2010, p. 3). Part of the strength in this approach includes the possibility of understanding sexuality from diverse but relevant methodological positions, which opens a window into the complex nature of sexuality in old age (Gott & Hinchliff, Citation2003). The qualitative phase of the design consisted of vignette-based focus group discussions and face-to-face semistructured interviews. The qualitative component of the study was more significant than the quantitative. Focused group discussion provides an opportunity to understand the cultural worldviews of older people, their peers’ interpretation of the realities of aging and sexuality, and the dynamics that exist within their communities. The group discussion was stimulated through constructed qualitative vignettes based on evidence from the literature and everyday realities among older people within the study settings. The evidence from the group discussion was deployed in developing the semistructured interviews. The interviews provided insights into individual views and experiences around aging and sexuality. It also gave insights into how older persons navigate the social apathy around sexual activities in old age and exercise their agencies in resolving any associated challenge. It also provided additional opportunities to understand the navigations, contestations that trail sexual activities in old age and how individual agencies are deployed in the process. The findings presented here are qualitative evidence that resonates with older men’s and women’s perceptions of the woman’s body at menopause and possible implications for sexual desires and practices in old age.

Study setting

The study was carried out in six communities (Bodega, Sango, Oniyere Aperin, Inalende Oke-Bola, Kobiowu, and Odo-Oba) in Ibadan North and Ibadan South East Local Government Areas (LGAs). Both LGAs are located within part of the 11 LGAs in the metropolis of Ibadan. The city of Ibadan is categorized into three subsets: inner core, transitory, and peripheral (Coker, Awokola, Olomolaiye, & Booth, Citation2007; Fabiyi, Citation2004). The inner core includes high-density residential districts with 300 persons per hectare. Indigenes are prominent residents in the inner core areas. Houses within the inner core of Ibadan city are mainly traditional, owned and occupied by family members, with a few rooms or flats available for rent. The spatial arrangement is poor, crowded, and difficult to access. Nonetheless, the netted spatial arrangements foster interactions and provide links for diverse forms of relationships, including the unsolicited role of older people serving as models to others in such settings.

Despite the similarities in the characteristics of the houses, differences also exist among these buildings. There are houses built with concrete materials and those constructed with mud and traditional architectural designs. These physical differences also mirror variations in the socioeconomic status of the house owners and tenants in the inner core areas. Some of the house owners are older males with several family members and tenants. It is typical to see many households in a bungalow with less than 10 rooms. The rent on accommodation in these locations is relatively affordable; as such it is densely populated compared to other parts of the city. A high proportion of older men and women who are tenants also find such locations affordable as their incomes dwindle alongside any financial support they may receive from their adult working children or relatives.

The spatial arrangements of the inner core of the city also make it noisy and filled with many social activities. There are different spaces for social interactions in diverse ways. Opportunities also exist for different activities and sexual networking as the frequency of interactions increase in diverse ways, including intergenerational dating and extramarital relations (Lawoyin, Osinowo, & Walker, Citation2004). The neighborhoods also boast of a high presence of traditional healers, patient medicine vendors, and petty traders.

The peripheral areas are less congested and are mainly occupied by the working class, especially the elites. The socioeconomic configuration of the dwellers in such neighborhoods differs slightly from those in the inner core and transitional areas. The transitional areas are more of the emerging neighborhoods where new sets of elites and those seeking better spatial neighborhoods are primarily concentrated. Their socioeconomic characteristics mirror those in the peripheral areas as they are elites; they have better income and a greater mix of ethnicity. There is a high chance of coming across residents from the different ethnic groups in Nigeria in these locations. Despite the lack of evidence to show variations in sexual beliefs and practices, theoretically, there are chances that older Yoruba people would share different worldviews around sexuality and aging from other ethnic groups in Nigeria. Hence, the choice of concentrating on the inner core of the city, where there is a high presence of older Yoruba people. It is noteworthy that this decision does not imply that the Yoruba people in Southwestern Nigeria are homogenous in their worldviews and their sexual behavior. As such, the recruitment of participants was anchored on the need to achieve a relatively diversified population of older Yoruba people from the different dialects and not only the indigenes of Ibadan.

Sampling and recruitment procedure

The sampling frame consisted of older Yoruba people residing in the communities or neighborhoods within the inner core of Ibadan Metropolis. The recruitment of participants was purposive and directed toward older people (60+) who are of Yoruba extraction, whether they are indigenes of Ibadan or not but are residents in the inner core of the city.

The recruitment of eligible participants started with initial interactions with the community mobilization officers of Ibadan North and South East LGAs. Such officers have constant interactions with community leaders for various purposes. As such, they provided the links in reaching out to the community leaders within the two LGAs. Within the LGAs, the inner cores of the communities were identified for the recruitment of participants. Such areas have high proportions of older persons as residents with relatively homogenous socioeconomic environments. Furthermore, scholars like Guest, Bunce, and Johnson (Citation2006) have argued that sociocultural values and economic status influence how social actors construct and rely on their sexuality in diverse ways, including conversations. Thus, the recruitment of older people within such neighborhoods was for theoretical and realistic reasons, as conceived in this research.

The involvement of LGA officers and community leaders in the recruitment process aided the response rate: Most of the participants agreed voluntarily to participate. The research assistants also played crucial roles in the recruitment process; they assisted in the final recruitment of older males and females for the FGDs and interviews. Some of the participants in the FGDs also participated in the face-to-face interviews.

Data collection

Data collection was done through focus group discussion (FGD) and face-to-face semistructured interviews. The FGD guide was structured along thematic issues about the specific objectives of the broader research. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic of interest, two qualitative vignettesFootnote1 were developed to stimulate participants’ interests in the FGD.

The two vignettes were based on established sociocultural beliefs around sexual behaviors and expectations in old age. Specific information about sexual practices and intimate heterosexual relations was built into the vignettes. From a life course stance, a high proportion of the older participants in the study (60+) setting would have had an intimate relationship or have been currently involved in one. With the absence of self-reported health challenges among the participants, it was also feasible to expose the participants to a focused discussion on sexuality and help-seeking. Against this backdrop, the vignette was designed to motivate the FGD participants to consider both expected and actual sexual beliefs and practices in old age. The FGD commenced with an icebreaker question on what it means to be an older person within the Yoruba culture; the participants were subsequently presented with the vignettes that depict the sexual behaviors of two older persons. Two pseudonym Yoruba names (Baba Alamu and Iya Asake) were adopted to draw the story closer to the participants. Both characters had ongoing intimate sexual relationships, and the vignettes outlined the challenges that might emerge from such relationships. The development of the vignette stories was iterative. The content and characters were constructed and pretested based on existing literature, established studies, media reports, and informal interactions with older people. More details on the methodology are contained in the larger research (Agunbiade, Citation2016).

With the vignettes and thematic structuring of the FGD guide, questions were asked about the existence of sexual relationships in old age; the gendered variations, views, and experiences around sexual behavior in old age; challenges of expressing sexual desires; and societal reactions and prevailing stereotypes around sexuality and aging. All the vignettes stimulated participants’ interest and discussions on the intersections between sexuality and aging, constraints to active help-seeking, the availability and quality of kin resources in the event of a sexual health problem, and responsiveness of the traditional and biomedical systems to sexual health needs in old age.

The perspectives of older males and females were explored in 12 vignette-based focus group discussions (FGD) and 18 face-to-face structured interviews among urban-dwelling older Yoruba men and women aged 60 years and above. The FGDs and face-to-face interviews were facilitated by trained and experienced social researchers using thematically structured guides. The interviews with older males were carried out by the first author and two male field assistants.

Two experienced field assistants also conducted the FGDs and interviews with older females. In the FGDs with females, the first author acted as an observer but sometimes interjected by writing on a piece of paper areas that needed further probing. This was done to reduce the effect of gender and age bias due to the sensitive nature of the topic (Russel, Citation2007). The characteristics of the interviewees were similar in several areas to those of the FGD participants, as the interviewees were recruited from the FGD participants.

All the FGDs were organized by gender and three age cohorts (60–69 years, 70–79 years, and 80 years and above). The intention was to gain insights into what Simon (Citation1996) tagged as age-graded constructions of sexuality. Simon (Citation1996) maintains that each culture creates an age-graded framework that defines what social actors can do or not do with their bodies in time and space. Theoretically, the FGDs were conducted in this direction with the hope of capturing possible variations between gender and across the three age categories in this research.

Each FGD comprised of eight to 10 participants. As shown in , a total of 107 older Yoruba men and women aged 60 years and above participated in the 12 focused group discussions. All the FGDs took place in locations agreed upon (community town halls and compounds of community leaders) by the gatekeepers and participants; the FGDs took place in secured spaces for community meetings and the interviews at the homes of the participants. The findings from the FGDs informed the recruitment and further issues that were covered in face-to-face interviews with older men and women. The longest FGD lasted two hours plus five minutes, and on the average, it took one hour and 32 minutes to complete an FGD session. The interviews lasted for 40.6 minutes on the average. Light refreshments and gift items, which include plastic buckets and face towels were given to thank the participants.

Table 1. Focus group locations by gender and age categories

Data analysis

The 12 vignette-based FGDs and semistructured interviews were transcribed in the Yoruba language and then translated into English. Two experts in the Yoruba and English languages conducted a back-to-back translation of the transcripts to ensure convergence of views before the transcripts were coded. These steps helped to ensure that the participants’ views were gathered and appropriated to retain their meanings and positions. The analysis was based on themes and subthemes. The process was carried out at two levels: First was a focus on the themes that guided data collection. At this point, salient themes and subthemes were identified for the next level of analysis. The next stage of the analysis involved editing of the transcripts, which were exported into Nvivo 10 for further analysis. The use of Nvivo provided a unique opportunity to conduct content and thematic analyses of the data from both inductive and deductive positions.

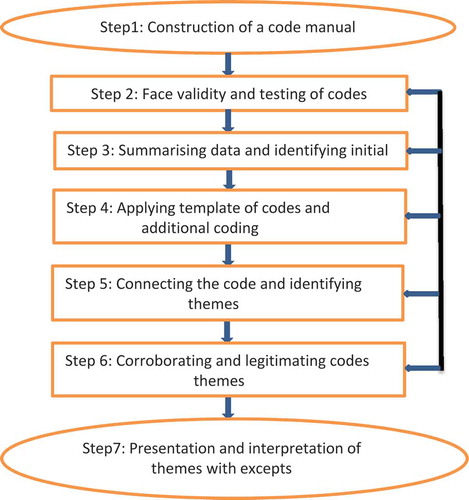

The transcripts were repeatedly read for insights into the data. The process provided additional insights and codes into emerging issues. As depicted in , the analysis progressed from this level to a seven-step approach based on suggestions from the literature (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2008; Onwuegbuzie, Dickinson, Leech, & Zoran, Citation2009). The procedure was also followed in analyzing the FGDs and individual interviews.

Figure 1. Procedures and steps in analyzing the focus group data

Ethical consideration

As sexuality studies is a sensitive issue, it is widely believed that voluntary participation requires ethical approval and considerations. As such, we obtained local permission from the community leaders along with prior institutional ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committees at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, with the protocol number H13/11/16 and the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, with the registration number: IPHOAU12/211.

Results

shows the six locations in which the 12 FGDs where conducted and the number of participants in each FGD session based on gender and age categories. Across the three age categories of participants in the FGDs, two-thirds of the males were married. On the other hand, close to two-thirds of the women across the three age groups were widows, and only one-tenth of their male counterparts were widowers.

Polygynous marriage was predominant among the participants. More than two-thirds of all the participants were Muslims (71%). Only 24 participants were Christians, and three were from the traditional Yoruba religion. The findings revolved around three connected themes and a subtheme. The first theme provides insights into the interpretative constructions of bodily changes as a reality that cuts across the life span of individuals and social categories. The emphasis here was on how menopause, one of the changes that come through aging, imposes psychosocial consequences on women, including their sexual rights within and outside marital relations. The second and third themes capture the participant’s construction of menopause as a biopsychosocial phenomenon that can be negotiated in several ways regarding the implications of sexual relationships and social expectations around the woman’s body. Both themes describe the controversy that surrounds sexual behavior in old within the study settings. Drawing the stories, the participants positioned the sexual behaviors of the vignette characters, that of their peers, and along with their own experiences within social framings around normative and unacceptable sexual behaviors. The possible implications of continuous engagements in sexual activities were captured in the subtheme as a folk illness that affects older women, as described with some excerpts.

Bodily changes, duties, and rights in intimate relations

From a life course framework, the participants discussed bodily changes in two stages: reproductive and postreproductive stages of life. Both stages were classified as sociobiomarkers that define the duties, rights, and moral correctness that is expected from women: duties and obligations in marital relations and what qualifies as appropriate or abnormal. During the reproductive stage, women are duty bound to respond to the sexual demands and needs of their husbands. The participants depicted these expectations as normative and functional to harmonious marital relationships. Commitment and motivations to fulfill these obligations could be sometimes contested when there are limited or inadequate reciprocal efforts from the men in such relations. In one of the FGDs with women, the participants contended that sexual satisfaction and commitment to a husband’s sexual demands depend on his performance of other duties. Such efforts are often appreciated and reciprocated by women where possible. This view was also corroborated in the narratives of four interviewees who believed that commitment to a partner’s sexual needs also depends on the performance of other responsibilities. Once a woman has such assurance, commitment and willingness to satisfy a husband’s sexual needs can be assured:

A woman that is loved by her husband will find it easy to respond to sexual demands even in old age. It is usually difficult when your husband flirts around and hardly provide for his children and wife at home. (An older woman aged 79 years, FGD with women, Kobiowu Community)

The pains of unfaithfulness, lack of love, and emotional havoc can deter the commitment of women to societal expectations. For most of the female participants, the cultural expectations of submissiveness can lapse, especially with sexual duties and responsibilities. Resistance to such obligations might not be feasible enough in reproductive age when most women, especially those in polygynous marriages, must endure the pains of sharing their husband and resources with other women. For women with this view, the cultural expectations that a woman must submit her body to her husband has caused much havoc for some women. The argument of these participants centered on the egocentric attitudes of some men who are fond of claiming ownership over their wives’ bodies while failing in their responsibilities in acting as breadwinners and providing support for their wives.

However, such obligations are contested in the post-reproductive stage when the willingness to fulfill these obligations wanes with disinterestedness in sexual activities. As argued by some of the participants, the apathy towards fulling marital obligations, including the sexually related ones could change as long as older couples were willing to soothe their partner’s expectations.Regarding the sexual behaviors of the vignette characters, the FGD participants argued that balancing satisfaction and performance in marital responsibilities could be difficult. For the participants, the male vignette character Baba Alamu would find it challenging to please or love all his wives and concubine equally. In their view, each woman has her peculiarities, including their desires for sexual intercourse and assessments of support and faithfulness of their husbands to them. In buttressing this position, two participants in the FGDs with women aged 60 to 69 years (Bodija) argued that most men found it difficult to meet up with their wives’ expectations, which compounds how women would react to their husband’s sexual demands and needs during menopause, whether such women are in monogamous or polygamous marriages.

Comparatively, the participants felt that women in polygynous marriages could be worse off in terms of the attention and support they enjoy from their husbands. In the menopausal period, women in polygynous marriages experience an unequal and sometimes unhealthy rivalry as they compete with other younger wives for their husband’s attention. The difficulty in surviving polygynous marriage was described by one of the participants by referencing a famous Yoruba proverb. As found in the literature, the proverb is stated commonly as Obínrin tí ko lórogún ko tii màrùn tí ńṣèun. [A woman who does not yet have a co-wife does not yet know what disease she has] (Owomoyela, Citation2005, p. 308).

Participants from one of the FGDs with men reiterated the possible emotional and psychological constraints that older men with multiple wives would be faced with:

His sexual behavior will fetch him disrespect from his wives and children unless he takes good care of his home without any favoritism. If he can readjust and start performing the responsibilities of a father, then they will regard him as a responsible husband. (FGD men aged 60–69 years, Bodija Community)

The excerpt shows that the male vignette character (Baba Alamu) would be unjust and unfair even unintentionally to all his wives, including the concubine. In practice, the participants considered equality and fairness as scarce because some husbands had been found to treat their concubines better than their wives and prefer one woman to another. The FGD participants commented that inherent tensions and rivalry characterized polygynous marriages.

For this group of participants, Baba Alamu would prefer the younger wives to the older ones for several reasons. For instance, the younger wife might be more beautiful and sexually expressive and active than the older wives. Thus, Baba Alamu would devote more time to his younger wife at the expense of the other wives. In this context, frequent sexual intercourse would likely occur. Some of the female participants noted how the use of a rotational timetable could guide and reduce tensions and rivalry:

He will be entering their rooms (having sex with them) regularly. He must not say that any of them offends him; therefore, he will not enter her room. No matter their number, he must be doing that. He must give them the same amount of time, and even their children must receive equal treatment; he must not have preferences. (FGD with women in Kobiowu, 70–79 years)

Thus, to reduce the emotional breakdown and unnecessary rivalry among the wives and concubines, Baba Alamu must be firm in his decisions and avoid favoritism. The male participants argued further that women could be very emotionally challenging to satisfy and would prefer to engage in frequent quarrels and inevitable rivalry among other wives. Under such circumstances, some of the participants claimed that Baba Alamu must satisfy the wives and concubines with sex, money, gifts, nonfinancial support, and attention. The participants, however, argued that owing to bodily changes, the older postmenopausal wives would have retired somehow from sex, while Baba Alamu’s ability to satisfy the younger wife was also doubted.

In extending the conversation, it became necessary to probe further the views of the participants around menopause, sexual retirements, and the possible complications that might arise from continuous sexual engagements for both older men and women.

Menopause and the need for sexual retirement

The age at which a woman reaches menopause differs and thus depends on individual experiences and circumstances within individual marriages. Some of the participants argued that once a woman becomes a grandmother, then it becomes a moral responsibility for such a mother to disengage from sexual intercourse. A possible explanation for this can be found in the exemplary roles of mothers and their duties to their children. A participant cited a recent scenario that involved one of his friends and described how the child of his concubine disapproved of his mother’s sexual relationships with his friend:

Recently, one of my friends was humiliated when his relationship with a concubine came to the attention of the woman’s son. What happened was that many people already knew my friend as Alhaja’s concubine, and he visits her regularly. During one of his visits, my friend, unfortunately, he met one of Alhaja’s sons who just returned from overseas and got the information that his mother has a concubine. Immediately, the boy saw my friend, he became furious and nearly threw my friend down the staircase. (FGD with men aged 60–69 years, Bodija Community)

Parental responsibilities include acting as a role model to one’s children in all spheres of life. The consciousness of living as an exemplary mother and the mutual support from children could serve as a barrier to sexual liberation during menopause. The participants expressed the view that mothers in polygynous relationships would need to support their children rather than struggle for sex. More pronounced competition and marginalization of resources dominate interactions among wives and children in polygynous homes. As such, the participants with such background were quick to predict that older women from such backgrounds would prefer to commit themselves to their children’s survival and avoid losing their support based on moral issues. Children’s approval or disapproval of their parent’s sexual or intimate relationships has more consequences for women than for men. The participants acknowledge that sometimes, adult children monitor their mother’s relationships, their friends, and places of visit to be sure they are not involved in extramarital relations. Such monitoring applies less to men, especially when such men are the social type.

The male participants found it difficult to place an age limit on men’s involvement in sexual activities. The following extract offers a picture of the various suggestions given by females and males:

The age of 60 years is enough for a woman. I cannot say precisely, but older persons that are around 80 years may still be performing. If the husband is still alive (not someone that has lost her hubby too early) and the man did not marry another woman. If they still get to sixty (60 years), it is still good. However, after 60 years, if the man still wants sex, she may tell him that she allows him to get it elsewhere to live long and provide food for the children. (FGD with women aged 60–69 years, Bodija Community).

In comparison to females, the male participants opined that men’s biological makeup places them at an advantage over women. However, some men are also at an advantage over other men.

A critical rallying point for both the male and female participants was the intention behind sexual activities in old age. From a normative stance, a man who desires to have children whether he is older and has good health can continue to engage in penetrative intercourse. Citing several examples and personal experiences, most of the male participants and a few female participants rationalized this social justification:

We had a father who was very old, but even at 80 years, he still married a young woman, and she was carrying a baby by the time baba died. For men, a father may be up to 100 years old, but for women, a mother must not be more than 50 years old. Also, if a woman has stopped menstruating, it is somehow dangerous to be having sex. (FGD with women aged 70–79 years, Odo Oba Community)

The excerpt again points to the advantaged position of men and the social value of fertility. Men are determined to keep indulging in sexual intercourse because there are opportunities to enter new sexual relationships for procreation and pleasures. In comparison, women with conception or fertility challenges are encouraged to relinquish their sexual desires and rights as they enter menopause.

Social desirability and sexual worth of the woman’s body

Sexual activities, pregnancy, and childbearing are core social and biological activities that have an impact on the social desirability of a woman’s body. In this sense, the participants described pregnancy and childbearing as activities that make women age faster than men do. These responsibilities are normative and time-bound because women are wired biologically for optimal reproduction before menopause. The participants thus argued that young women would benefit more by marrying in their 20s as against marrying late to guarantee fertility before entry into menopause.

The emphasis on timing and the degeneration of the woman’s body due to procreation and childrearing responsibilities were acknowledged across all the FGDs and in almost all the interviews. The participants affirmed that both young and old in their communities were mindful of the limited time that is available for an average woman to actualize her reproductive duties. A typical Yoruba is saying that supports this expectation and exploitation of the woman’s body is Ile obinrin kii pee suu [The night comes early for a woman]. With stereotypical descriptors, the participants handpicked menopause as a biosocial maker of retirement from sexual activities and the value of the woman’s body. The position of the male participants was that sexual intercourse profits the woman’s body in their reproductive stage in life. During this period, women would attract more attention and resources, including pampering from their husbands—even those in polygynous relationships:

Men find young women attractive. Those features that differentiate them from men are easily seen. The depreciation in their bodies comes with time and women are also different, but in old age, a woman loses all the sexual attraction they had enjoyed in their youthful age starts. (FGD with men aged 60–69 years, Bodija Community)

The consciousness and the perceived linkages between bodily changes and sexual activities impact both men and women; nevertheless, women were perceived to be more at a disadvantage:

Once a woman reaches menopause, it is all right for her to stop sexual relations. An older woman with male and female children would have seen and enjoyed some good things in life. Moreover, women age too soon than their male counterparts. (Interview with an older woman aged 83)

The FGD participants acknowledged that depreciation in the sexual worth of the woman’s body comes with age. Their attraction, therefore, depends on their physical appearance and social worth. Women who are financially independent and occupy better social positions could attract men of their age category or even younger. This was the argument of some of the women who debunked the stereotypical position that sexual desires and occasional intercourse are absent among older women. From the position of these participants, relationship qualities such as intimacy, perceived faithfulness, and health could also influence women’s sexual desires and interests. Relationships and the quality of interaction were given new limelight as the participants postulated that women who were happy in their marriages would likely endure the pain that comes with sexual intercourse. In their view, each marriage has its peculiarities. Within each type of marriage, satisfaction, challenges, and tensions are inherent, as also are the reactions to these events among the couples in such marriages. The postulation from this later submission was that women in unhappy marriages or those with health challenges would easily consider menopause as a route to escape from their sexual duties.

Across the group and individual interviews, the participants adopted an age-grade perspective in presenting their opinions on what constitutes acceptable or normative sexual behavior of older men and men. The age grade became more overt as the participants reacted to the sexual behavior of the female vignette character (Iya Asake) vis-à-vis her involvement in extramarital relations. The possibility of engaging in sexual activities did not emerge as a shock; some of the female participants felt that husbands who are supportive and not perceived to be involved in extramarital relationships could sometimes be allowed sexual intercourse. However, most of the participants, older male and females, frowned at older women who engaged in extramarital affairs as not just wayward but most likely to lose their social worth as grandmothers and their position as a respectable older woman in their communities. As a counterreaction to sexual retirement, some of the male participants capitalized on the situation and rationalized the need for extramarital relations or a new wife.

The privileged position of men and the emphasis on sexual usefulness portrays the woman’s body as the man’s sexual and reproductive field. In the menopausal period, the terrain for sexual activities changes as the vagina becomes dry due to aging. The participants argued further that the dryness makes penetrative sex painful for women and less enjoyable for men. Thus, with the onset of menopause, some of the females felt that older women who continue in sexual activities would suffer in two main ways: First, such women would be labeled as sexually loose and undisciplined and are also likely to suffer stigma and lose some of their essential networks. Secondly, such women were likely to suffer from illnesses that are believed to be associated with sexual activities. However, the health implications of sexual activities were not substantiated, but the view cut across the various FGDs and appeared as common ways of denying older women’s right to their bodies.

Oyun iju in old age: A folk illness among sexually active older women

Continuous engagement in sexual activities, especially with multiple partners, will increase sexual pain, infections, and the occurrence of oyun iju—a form of folk fibroid. Unlike idakole, oyun iju (fibroids) can occur in reproductive or postreproductive ages. In the FGDs, the participants described oyun iju as the consequence of indiscriminate or frequent sexual activities among older women. They claimed that the sperm deposited during intercourse resides in the womb because of the lack of menstruation. With frequent sexual intercourse and deposits of sperm, fibroids can occur. The participants reiterated their call for retirement from sexual activities to avoid oyun iju:

A woman that has stopped her menstrual period needs to abstain from sex to avoid a type of pregnancy called oyun iju. There are neither traditional nor modern medicine drugs or vaccines for such conditions. [FGD with female aged 80 years and above, Inalende Community].

In menopause, the male sperm becomes useless. It is only for reproduction that the woman’s body requires sperm to function correctly, especially for her menstrual flow. (FGD with male aged 80 years and above, Inalende Community)

From divergent positions, it could be concluded that both the male and female participants employed menopause in framing as well as interpreting women’s sexuality and their experiences. Some of the male participants described menopause as a sign of the depreciation of the woman’s body for pleasurable heterosexual relations. The women considered menopause to be a route to refuse sexual demands from their husbands and avoid fibroids. Similarly, some of the sexually active men felt the refusal was enough to engage in extramarital affairs. In this case, younger women are sought, or perhaps middle-aged women who are willing and available for such relationships. It is noteworthy that older men who engage in continuous sexual activities were not perceived to suffer from any illness—except for a folk sexual infection like magun—or gonorrhea or syphilis.

Discussion and conclusion

There is growing research attention on women’s experiences and perceptions of menopause (Rubinstein & Foster, Citation2013; Ward et al., Citation2019) and the possible implications for their sexual and marital relationships (Davina et al., Citation2007; Tshitangano et al., Citation2015). Similar attention has also focused on how men can assist their partners in navigating through menopausal challenges (Cid Quirino et al., Citation2016). However, very few studies exist on how older men and women construe menopause and its possible influence on their sexual behaviors.

This article provides insights into how cultural beliefs around the physiological changes that come with menopause are sustained and deployed in framing sexuality and health outcomes in old age. Among the Yoruba people in Southwest Nigeria, this study is the first to explore and contextualize how both older men and women’s perceptions of menopause could shape sexual behaviors, choices, practices, and sexual rights in later life. The study adopted an interpretative constructivist perspective approach, which positioned the participants at the center of generating relevant evidence.

The findings highlighted how physiological changes in the woman’s body act as critical indicators of when to engage in, abstain from, or disengage from sexual activities. Conformity to these expectations is rewarded and valued as women transit from reproductive to their postreproductive stage in their life span. The woman’s body has the highest sexual value during the reproductive period. Beyond the presumed usefulness, the value and significance dwindle as the sexuality of older women is played down irrespective of the evidence that they are sexual beings across their life spans (Koepsel & Johnson, Citation2017; Ward et al., Citation2019; Wong & Ho, Citation2007).

The unattractiveness of the woman’s body in old age was vividly described by how older men felt about the worth of sex with such women. The findings showed that some of the males described sex with menopausal women as being less pleasurable and an unwarranted loss of sperm. In a way, this view might perhaps relate to the premium on penetrative vaginal sex and the preference for children, even in old age. Another possibility is the belief that sex with menopausal women could negatively affect the health of women and reduces the derivable pleasures from penetrative sex. Such cultural conceptions define the ideal body, sexual orientations, and the appropriate timing for sexual activities in old age (DeLamater & Koepsel, Citation2015; Fileborn et al., Citation2015; Koepsel & Johnson, Citation2017).

Within the study settings, the participants were adamant in their descriptions and prescriptions of acceptable and unacceptable sexual behaviors in old age. Such gendered framing of sexual behavior captured how older men and women deploy a differentiated gendered lens in looking at their sexual needs and the implications of satisfying or making efforts actualizing such needs. Older men appeared liberal in assessing their sexual needs and the opportunities available to them but were more restrictive in their positions around older women’s sexual behaviors. Interestingly, the sermon around sexual disengagement in old age favors older men. This position is expected given the patriarchal nature of the study settings and the social preference men enjoy in relation to their sexuality. The situation is like what obtains in many social settings where older women’s sexuality is monitored and appraised based on morals (Koepsel & Johnson, Citation2017; Ward et al., Citation2019; Wong & Ho, Citation2007).

Despite the social restrictions, some of the women questioned this social expectation as they considered some relational issues. From the findings, the quality of support from their husband and their happiness with their marriages could qualify as conditions to satisfy their husband’s sexual requests. The position of these women supports the findings from the qualitative study by Kartini and Hikmah (Citation2017) among Indonesia women where some of them challenged the social expectations and the functionality of submissiveness and willingness to satisfy their husband’s sexual demands as part of their womanhood. For some of the women, some husbands would develop this withdrawal attitude when they have younger women in their lives, including those who engage in extramarital relations. For most of the participants, such attitudes from men after many years of marriage aggravates their consciousness around the pain and stress in sexual intercourse in old age. In contrast, such pains can be tolerated when a husband lives up to expectations regarding care and affection. This latter assertion from this category of participants supports existing evidence on how quality support and healthy attitudes from men toward their menopausal wives could improve marital quality and sexual relationships (Cid Quirino et al., Citation2016; Davina et al., Citation2007).

The findings further revealed that most of the women in polygynous marriages questioned the functionality of submissiveness to their husbands’ sexual demands. Women with such an impression might relate to the tensions in polygynous marriages (Jacoby, Citation1995; Mabaso et al., Citation2018; Ramakuela et al., Citation2014). Existing evidence shows that women in polygynous marriages are more likely to suffer in their emotional and mental well-being compared to those in monogamous relationships (Al-Krenawi & Graham, Citation2006). Across the life course, sexual desires and expressions are fluid and dynamic for individuals (Koepsel & Johnson, Citation2017). Within the study contexts, the boldness to exercise such agencies might be aided by the view that their older women’s bodies lack sexual value. The female participants contested the notion of the asexual older woman as they passively affirmed their sexual desires. The social stigma around expressing one’s sexual desires and deep feelings of not being sexually attractive in old age could have accounted for this passive disposition.

There are social settings where permissiveness of sexual expression is allowed at some point in a woman’s life. For instance, ethnographic research among the !Kung women in Botswana shows that postmenopausal women have a relative level of freedom in fulfilling their sexual needs. With age, !Kung women are allowed to enter into new sexual relations, including extramarital relations, once they enter menopause and before they turn 65 years of age (Lee, Citation1992). However, the findings from this research contrast with that. The likelihood of engaging in overt extramarital affairs was discounted among older women within the study settings. The consensus from the findings was to refuse sexual demands from their husbands by appealing to the dominant stereotypes around menopause. The reference to menopause as a basis to refuse sex is consistent with the findings from Yan, Wu, Ho, and Pearson’s (Citation2011) study on sexual behavior of older Chinese men and women and even in Indonesia where submissiveness to husband’s sexual demands qualifies as a mark of womanhood, a blessing, and as a calling (Merghati-Khoei, Ghorashi, Yousefi, & Smith, Citation2014).

As captured in the narratives and positions of the participants, repeated sexual refusals have some intended and unintended consequences. Whether intended or not, the interpretations and impact differ for both older men and women. For the older men, sexual refusal could qualify as a question about their ego and their self-worth, which makes it easier for them to seek pleasures elsewhere. The quick switch might be connected to the perceived depreciated sexual value of older woman’s body and the social capital to attract sexual partners. Interestingly, the literature has been dominant with young people’s voices on the implications of sexual refusal on marital relationships. For older men, sexual refusal was a motivation for their peers or themselves to solidify existing extramarital relations or enter new ones. The boldness to speak about this motivation in group discussion perhaps highlights the privileged position that patriarchy offers older men within the Yoruba culture while disadvantaging women. It is noteworthy that the tendency to leverage on sexual refusals and engage in extramarital relations is not peculiar to older people. Such evidence was reported among middle-aged men in Uganda where sexual refusal was used as a justification for extramarital relationships (Cash, Citation2011). These findings again resonate how patriarchal social arrangements position men to react from an advantaged position. However, there are consequences for indulging in risky sexual practices, and the implications can be worse off, judging by the existing gaps in unmet needs for sexual and reproductive health-care services among older people in the study settings.

There is evidence that across the life course psychosocial and contextual factors affect sexual desires, expressions, and experiences of older women (Ussher, Perz, & Parton, Citation2015). Thus, it was not a surprise that for some of the older women, menopause offers the vehicle to challenge social demands on their sexuality and their reactions to their husband’s sexual requests. Thus, the findings from this study support existing literature that shows variations in the interpretations and ways older men and women perceive and attend to their sexual needs (DeLamater & Koepsel, Citation2015).

The findings in this study might be limited with the use of FGDs and face-to-face interviews with the older men and women on their embodied experiences within the contexts of aging, sexuality, and help-seeking. Nonetheless, the adoption of a social positioning lens availed the participants the opportunity to position old age, aging experiences, and their construction of the influence of menopause on sexuality in later age. At some point, menopause was conceived as a period that calls for sexual abstinence for women and more responsible sexual behavior among older men. As such, it was possible to gain gendered differentiated accounts of bodily changes and aging experiences, including those related to sexuality and sexual practices. Notwithstanding, the body is not the only site for the performance of sexuality, but it represents a significant site for an aspect of experiencing and demonstrating sexuality across the life course. It is, therefore, possible to understand the reality of sexuality through a focus on subjectivities and particularized insights from the actors’ position within given sociocultural contexts.

In the gerontological literature, DeLamater and Koepsel (Citation2015) have argued that accounting for individual particularities provides a unique opportunity to understand the differences in the significance of sexuality in old age. The findings from this study provide some contextual evidence in response to the critical need to understand cultural and social contexts in mediating existing gaps in knowledge on sexual expression and embodied experiences in old age (Fahs, Citation2011). The findings from this study thus offer contextualized insights into how age-graded expectations influence how older men and women frame and react to bodily changes and sexual needs among older Yoruba people in Ibadan, Nigeria. To an extent, these reactions might be connected to the Yoruba worldviews on social expectations of moral correctness and the “good old age.” As such, these expectations around bodily changes create differentiated experiences for older men and women, with implications for their sexual health and well-being.

Policy implications

There are some policy implications from the findings in this study, which indicate that in the menopausal period, denial and refusal to yield to husbands’ sexual demands could lead to tensions among older couples. This likelihood is high, judging by the absence of professional support for older couples within and outside the medical systems in the study settings. Within the study settings, women who refuse sexual advances from their husbands stand the chance of social condemnation and counterreactions from their partners. Such dispositions could negatively impact the psychological well-being of menopausal women and their relationships with others. Urgent attention is needed to introduce and integrate postreproductive sexual health-care services for older people at all the levels of care in Nigeria. However, although an evidence-based approach would be suitable, it is currently unavailable.

The motivation and opportunities for extramarital relations have some consequences for marital relationships among older couples and the sexual health of these older men and their sexual partners. An earlier publication from this research shows that most sexually active older men prefer not to use condoms. The basis was the perceived negative influence of condom use on sexual pleasures (Agunbiade & Togunde, Citation2018). With this attitude and the possible consequences of ineffective use, urgent attention is needed to promote the sexual health of older people in Nigeria. There is also the need for measures that can help older couples cope and resolve sexual tensions that are associated with menopause. Therapeutic sessions and interventions to reduce vaginal dryness and misconceptions around menopause would make some difference. Such support could also be introduced at the three tiers of health care in Nigeria. Social campaigns around healthy sexual practices and relations are urgently needed. Such campaigns can reduce the stereotypes around old age and the image of older people in Nigeria.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the older persons who participated in this research for sharing their views and experiences with us. The research would have been impossible without their voluntary participation. The findings were from the first author’s PhD research in Health Sociology under the supervision of Professor Leah Gilbert(second author) at the Department of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Vignette A

Baba Alamu is between 60 and 70 years old. He has three wives, a concubine (mistress), and 12 children. Recently, Baba Alamu married a fourth wife, who is much younger than the other wives are. Six months after marrying the fourth wife, Baba Alamu contracted a sexually transmitted infection.

Vignette B

Iya Asake is between 60 and 70 years old. She has a concubine and six children and lives with her husband. Iya Asake engages in sexual relations with her husband and the concubine. Six months after Iya Asake got a new concubine, she contracted a sexually transmitted infection.

References

- Agunbiade, O. M. (2016). Socio-cultural constructions of sexuality and help-seeking behaviour among elderly Yoruba People in urban Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. South Africa: PhD. University of the Witwatersrand.

- Agunbiade, O. M., & Togunde, D. (2018). ‘No Sweet in Sex’: Perceptions of condom usefulness among elderly Yoruba People in Ibadan Nigeria. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 33(3), 319–336. doi:10.1007/s10823-018-9354-8

- Al-Krenawi, A., & Graham, J. R. (2006). A comparison of family functioning, life and marital satisfaction, and mental health of women in polygamous and monogamous marriages. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 52(1), 5–17. doi:10.1177/00207640060061245

- Ayers, B., Forshaw, M., & Hunter, M. S. (2010). The impact of attitudes towards the menopause on women’s symptom experience: A systematic review. Maturitas, 65(1), 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.016

- Cash, K. (2011). What’s shame got to do with it? Forced sex among married or steady partners in Uganda. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 15(3), 25–41.

- Cid Quirino, B., Komura Hoga, L. A., & Lima Ferreira Santa Rosa, P. (2016). Men’s perceptions and attitudes toward their wives experiencing menopause AU - Caçapava Rodolpho, Juliana Reale. Journal of Women & Aging, 28(4), 322–333. doi:10.1080/08952841.2015.1017430

- Coker, A., Awokola, M. O., Olomolaiye, P., & Booth, C. (2007). Challenges of urban housing quality and its associations with neighbourhood environments: Insights and experiences of Ibadan City, Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Health Research, 7(1), 21.

- Davina, C. Y. L., William, C. W. W., & Suzanne, C. H. (2007). Are post-menopausal women “Half-a-Man”?: sexual beliefs, attitudes and concerns among midlife Chinese women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 34(1), 15–29. doi:10.1080/00926230701620522

- DeLamater, J., & Koepsel, E. (2015). Relationships and sexual expression in later life: A biopsychosocial perspective. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(1), 37–59. doi:10.1080/14681994.2014.939506

- Emmers-Sommer, T. M., & Walker, N. (2017). High-risk sexual behavior in postmenopausal women AU - Hertlein, Katherine M. Marriage & Family Review, 53(5), 417–428. doi:10.1080/01494929.2016.1247765

- Fabiyi, O. (2004). Gated neig [h] bourhoods and privatisation of urban security in Ibadan metropolis. Retrieved from http://books.openedition.org/ifra/481

- Fahs, B. (2011). Sex during menstruation: Race, sexual identity, and women’s accounts of pleasure and disgust. Feminism & Psychology, 21(2), 155–178. Retrieved from http://fap.sagepub.com/content/21/2/155.abstract

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2008). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. doi:10.1177/160940690600500107

- Fileborn, B., Thorpe, R., Hawkes, G., Minichiello, V., Pitts, M., & Dune, T. (2015). Sex, desire and pleasure: Considering the experiences of older Australian women. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(1), 117–130. doi:10.1080/14681994.2014.936722

- González, C. (2007). Age-graded sexualities: The struggles of our ageing body. Sexuality & Culture, 11(4), 31–47. doi:10.1007/s12119-007-9011-9

- Gott, M., & Hinchliff, S. (2003). How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Social Science and Medicine, 56(8), 1617–1628.

- Greifeneder, R, Bless, H, & Fiedler, K. (2018). Social cognition: how individuals construct social reality. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice. New York: US. The Guilford Press. New York, NY: US The Guilford Press.

- Higgs, P., & Jones, R. (2009). Medical sociology and old age: Towards a sociology of health in later life. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hinchliff, S., Gott, M., & Ingleton, C. (2010). Sex, menopause and social context: A qualitative study with heterosexual women. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(5), 724–733. doi:10.1177/1359105310368187

- Hunt, S. J. (2017). The life course: a sociological introduction. Basingstoke, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ibraheem, O., Oyewole, O., & Olaseha, I. (2015). Experiences and perceptions of menopause among women in Ibadan South East local government area, Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research, 18(2), 81–94.

- Isiugo-Abanihe, U. C. (1994). The socio-cultural context of high fertility among Igbo women. International Sociology, 9(2), 237–258.

- Jaber, R. M, Khalifeh, S. F, Bunni, F, & Diriye, M. A. (2017). Patterns and severity of menopausal symptoms among jordanian women. Journal Of Women & Aging, 29(5), 428-436. doi:10.1080/08952841.2016.1213110

- Jacoby, H. G. (1995). The economics of polygyny in sub-saharan Africa: Female productivity and the demand for wives in Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 938–971. doi:10.1086/262009

- Kartini, F., & Hikmah, H. (2017). Its A natural process and we should accept it as our destiny: Indonesian women perception to menopause. [Menopause; perception; knowledge]. Belitung Nursing Journal, 3(2), 6. Retrieved from http://belitungraya.org/BRP/index.php/bnj/article/view/40

- Koepsel, E. R., & Johnson, T. (2017). Changes, changes? Women’s experience of sexuality in later life AU - DeLamater, John. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–17. doi:10.1080/14681994.2017.1412419

- Lawoyin, T., Osinowo, H., & Walker, M. (2004). Sexual networking among married men with wives of child bearing age in Ibadan City, Nigeria: Report of a pilot study. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, 33(3), 207–212.

- Lee., R., B. (1992). Work, Sexuality, and Aging among IKung Women. In V. Kerns & J. K. Brown (Eds.), In Her Prime: New Views of Middle-aged Women (pp. 35-48). Urbana, United States: University of Illinois Press.

- Mabaso, M. L., Malope, N. F., & Simbayi, L. C. (2018). Socio-demographic and behavioural profile of women in polygamous relationships in South Africa: A retrospective analysis of the 2002 population-based household survey data. BMC Women’s Health, 18(1), 133. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0626-9

- Merghati-Khoei, E., Ghorashi, Z., Yousefi, A., & Smith, T. G. (2014). How do Iranian women from Rafsanjan conceptualize their sexual behaviors? Sexuality & Culture, 18(3), 592–607. doi:10.1007/s12119-013-9212-3

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., & Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 1–21. doi:10.1177/160940690900800301

- Owomoyela, O. (2005). Yoruba proverbs. London, UK: University of Nebraska Press.

- Rabiee, M., Nasirie, M., & Zafarqandie, N. (2014). Evaluation of factors affecting sexual desire during menopausal transition and post menopause. Women’s Health Bulletin, 2(1), e25147. doi:10.17795/whb-25147

- Ramakuela, N. J., Akinsola, H. A., Khoza, L. B., Lebese, R. T., & Tugli, A. (2014). Perceptions of menopause and aging in rural villages of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 19(1). doi:10.4102/hsag.v19i1.771

- Caçapava Rodolpho, J. R., Cid Quirino, B., Komura Hoga, L. A., & Lima Ferreira Santa Rosa, P. (2016). Men’s perceptions and attitudes toward their wives experiencing menopause. Journal of women & aging, 28(4), 322-333.

- Pauline Rossi. (2016). Strategic Choices in Polygamous Households: Theory and Evidence from Senegal. PSE Working Papers n°2016-14. Retrieved January 20, 2019 from https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01340567/document.

- Rubinstein, H. R., & Foster, J. L. (2013). ‘I don’t know whether it is to do with age or to do with hormones and whether it is do with a stage in your life’: Making sense of menopause and the body. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(2), 292–307. doi:10.1177/1359105312454040

- Russell, C. (2007). What do older women and men want? gender differences in the ‘lived experience’of ageing. Current Sociology, 55(2), 173–192. doi:10.1177/0011392107073300

- Simon, W. (1996). Postmodern sexualities. London, UK: Routledge.

- Thorpe, R., Fileborn, B., Hawkes, G., Pitts, M., & Minichiello, V. (2015). Old and desirable: older women's accounts of ageing bodies in intimate relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(1), 156-166.

- Tshitangano, T., Maluleke, M., & Tugli, A. K. (2015). Menopause, culture and sex among rural women AU - Ramakuela, N.J. Journal of Human Ecology, 51(1–2), 220–225. doi:10.1080/09709274.2015.11906916

- Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., & Parton, C. (2015). Sex and the menopausal woman: A critical review and analysis. Feminism & Psychology, 25(4), 449–468. Retrieved from http://fap.sagepub.com/content/25/4/449.abstract

- Ward, P., Mandville-Anstey, S. A., & Coombs, A. (2019). The female aging body: A systematic review of female perspectives on aging, health, and body image AU - Cameron, Erin. Journal of Women & Aging, 31(1), 3–17. doi:10.1080/08952841.2018.1449586

- Wong, E. L. Y., Huang, F., Cheung, A. W. L., & Wong, C. K. M. (2018). The impact of menopause on the sexual health of Chinese Cantonese women: A mixed methods study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(7), 1672–1684. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jan.13568

- Wong, W. C. W., & Ho, S. C. (2007). Are post-menopausal women “Half-a-Man”?: Sexual beliefs, attitudes and concerns among midlife Chinese women AU - Ling, Davina C. Y. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 34(1), 15–29. doi:10.1080/00926230701620522

- Yan, E., Wu, A. M., Ho, P., & Pearson, V. (2011). Older Chinese men and women’s experiences and understanding of sexuality. Cult Health Sex, 13(9), 983–999. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21824033