ABSTRACT

This study examined the effectiveness and influence on validity of a computer-based pop-up English glossary accommodation for English learners (ELs) in grades 3 and 7. In a randomized controlled trial, we administered pop-up English glossaries with audio to students taking a statewide accountability English language arts (ELA) and mathematics assessments. As is typically found, EL students exhibited lower achievement scores than non-EL students in all portions of the test. The pop-up glossaries provided inconsistent benefit for EL students. There was some evidence that the pop-up English glossaries had a minimal inhibitory effect for 3rd-grade students on both the ELA and mathematics assessment. Furthermore, 7th-grade ELs also showed slightly inhibited performance when using the pop-up glossary on the mathematics assessment. However, 7th-grade EL students had a performance benefit when using the pop-up glossary on the ELA assessment. We discuss how increased cognitive load placed on younger students may play a role in diminishing performance when using pop-up glossaries. We explore potential explanations for the difference outcomes between mathematics and ELA in grade 7.

In the United States, 4.4 million students are non-native English speakers (termed English learners or ELs). The recently-passed Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (ESSA) defines an EL as “an individual who, among other things, has difficulties in speaking, reading, writing, and understanding the English language that may be sufficient to deny the individual the ability to meet challenging state academic standards” (“Major Provisions,” Citation2016; italics in original). The act further requires the inclusion of ELs in state-wide standardized tests. This is a continuation of the testing mandate included in the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001 that required the inclusion of these students (Shafer, Willner, Rivera, & Acosta, 2009). Thus, when taking a state-wide standardized test, ELs are faced with the added difficulty of reading in a second language (Abedi, Courtney, & Leon, Citation2003a; Abedi, Lord, & Plummer, Citation1997; Coltrane, Citation2002; Menken, Citation2000).

ELs typically perform worse on state assessments than their native English speaking counterparts, and it is hypothesized that this is, at least in part, a result of difficulties with the language used on the standardized assessments (Abedi, Lord, & Plummer, Citation1997). Certain test items may be more difficult for ELs because of the items’ linguistic structure rather than the skills putatively measured by the test. Test items with a culturally specific focus (e.g., items centered around American holidays) are one example. Other examples are false cognates, polysemous words, and abstract words. A cognate is a word with the same linguistic derivation as another, such as the word chocolate, which has the same spelling and meaning in English and Spanish. A false cognate would be the Spanish term éxito, meaning success, versus the English term exit, whose Spanish equivalent is salida. Polysemous words are terms with multiple meanings (e.g., man can refer to both the human race as a whole and to an adult male).

Research has begun to examine the use of accommodations by ELs to test their effectiveness at helping students overcome their linguistic difficulties in testing. Here, we assess the effectiveness of pop-up English glossaries and their influence on the construct-related validity of the items using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in a real-world setting.

The Role of Accommodations in Testing

The ESSA mandates that state testing in language arts, math, and science include the scores of students determined to be ELs (see definition above). The act additionally mandates that appropriate accommodations be provided during the assessments until such time that the students attain a high level of English proficiency “as measured through the English proficiency assessments administered in the state” (Council of Chief State School Officers, Citation2016, p. 5). This mandate increases the need for educational research to determine exactly which accommodations are the most effective and valid to ensure that ELs’ test scores are accurate reflections of their knowledge.

States currently classify accommodations into four categories: Setting, scheduling/time, presentation, and response. These categories were derived for the accommodations designed for students with disabilities based on their Individualized Education Plan (IEP). It has been suggested that this classification system may not be appropriate for ELs, and instead accommodations should be classified as either direct or indirect linguistic support (Rivera & Collum, Citation2004; Young & King, Citation2008). Direct linguistic support accommodations target specific linguistic features of the test and thus affect the student’s ability to access and respond to them (i.e., administering the accommodations either in English or the student’s native language). Indirect linguistic support accommodations target such aspects as the time or environment of the test, and are typically administered as a means of reducing the cognitive load placed on students in testing conditions (Solano-Flores, Citation2012).

Effectiveness and Validity of Accommodations to Support English Language Learners

There exists a growing body of research on the use of accommodations to help ELs with the language structure of an assessment. Of the four accommodation categories, states have often elected to use either setting or timing changes, neither of which address the language barrier faced by ELs (Menken, Citation2000). Research in this area is largely focused on a number of specific linguistic accommodations, including linguistic modification, English dictionaries, bilingual dictionaries, English glossaries, and bilingual glossaries.

The primary focus of the research on test accommodations is centered on two aspects: The influence on claims of the construct-related validity of test items and the effectiveness of the accommodation. Introducing an accommodation may threaten to invalidate the claim that the item measures the intended construct. If the accommodation changes the construct measured, claims about that construct based on the accommodated measure are no longer considered valid. An accommodation that does not alter the construct while removing construct-irrelevant barriers protects and enhances the construct-related validity claims. Analysts usually infer that the evidence of construct-related validity of test items is unchanged when non-ELs using the accommodation see no significant change in their test results (Abedi & Ewers, Citation2013). A differential boost between ELs and non-ELs might also provide some evidence that the accommodation is effective, and may not be changing the construct, especially when applied to mathematics. A boost for non-ELs would suggest that the item would benefit from language simplification for everyone. In ELA, any boost for non-ELs would call into question the impact of the accommodation on the construct. For simplicity, we refer to this as the influence on validity in the current article. The effectiveness of an accommodation measures how well it helps ELs overcome linguistic barriers. An accommodation is effective when there is a significant increase in scores for ELs in that testing condition. Below, we briefly review the literature addressing the influence on validity and the effectiveness of EL accommodations addressing direct linguistic support.

Linguistic Modification

A linguistically modified test (also known as a simplified English version or plain English) is an assessment that has had its linguistic structure simplified to aid students in comprehension. Numerous linguistic features have been found to increase the complexity of a test. These include word length, sentence length, word frequency, prepositional phrases, conditional phrases, and passive voice (Abedi, Hofstetter, Baker, & Lord, Citation2001).

Linguistic modification has shown inconsistent effectiveness. Specifically, researchers have often failed to find supporting evidence for linguistic modification as an effective accommodation for ELs. Brown (Citation1999) took a small number of ELs and randomized them to receive either a linguistically modified (termed “plain English” in the study) assessment or the original form of the test and compared these results to non-ELs taking the same tests. Results were null as the linguistically modified version had no significant effect on ELs scores. Johnson and Monroe (Citation2004) found a similar result when they administered two versions of a test form to a sample population of students, which included a group designated as ELs. One version of the test contained linguistic modification on all even-numbered test items, the other version had all odd-numbered items with linguistic modification. Again, the accommodated items failed to show effectiveness at reducing the performance gap between ELs and non-ELs.

Despite the inconsistent evidence supporting linguistic modification, some evidence suggests that linguistically modified tests may be a viable accommodation for older ELs (e.g., Abedi, Courtney, Mirocha, Leon, & Goldberg, Citation2005) and for those with a higher level of English proficiency (e.g., Kiplinger, Haug, & Abedi, Citation2000). This effect may be due to the level of complexity involved in tests administered to grade 8 students (e.g., more advanced level of discourse, higher level of content domain) versus those administered to grade 4 students. Abedi, Courtney, and Leon (Citation2003a) found that while grade 4 ELs saw no significant score changes for the linguistic modification accommodation, grade 8 ELs had a significant increase in their test scores. Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Pennock-Roman and Rivera (Citation2011) found that when studies took English language proficiency (ELP) into account, linguistic modification had a larger mean effect size for ELs classified as high and high intermediate, which includes students who are either fluent or near fluent in the English language, respectively. Further research could delve into exactly which aspects of a test’s linguistic structure need to be modified on a test to improve the accommodation’s effectiveness and while not influencing the test’s construct-related validity.

Dictionaries

The use of a dictionary has been another popular accommodation studied, as it provides easy access to definitions of words that students taking an assessment may find complex. Dictionaries are typically administered in one of three formats, either as a customized simple English version, a bilingual version, or an unedited (i.e., print version) dictionary. The words included in the customized dictionary typically are not content-related (i.e., non-mathematical terms are used when taking a mathematics test), reducing the risk of adversely influencing construct-related validity. Several studies have found positive results with the use of customized and bilingual dictionaries, with effectiveness and little influence on validity being seen at various grade levels (e.g., Abedi et al., Citation2005; Abedi, Lord, Kim, & Miyoshi, Citation2001; Albus, Thurlow, Liu, & Bielinski, Citation2005). Abedi and Ewers (Citation2013) expressly stated that unedited dictionaries should be avoided, as they have a high potential to affect the construct being measured and they are an inherently difficult accommodation to use (especially for younger students).

Abedi et al. (Citation2005) assessed students on their comprehension of scientific concepts and their reading comprehension in an experimental study. Students were randomly assigned to either an original version of the test or an accommodation condition that included an English or bilingual dictionary or a linguistically modified version of the assessments. The English dictionary was a copy of Merriam Webster’s Intermediate Dictionary; the bilingual dictionaries were Chinese, Spanish, Korean, or Ilocano and contained the closest translations for complex English words in their respective languages. The dictionaries contained both science and non-science content words found in the test. Researchers found that grade 4 ELs performed better using the dictionary accommodations (both the English and bilingual dictionaries), while grade 8 students performed better with the linguistic modification accommodation.

There have been some cautions issued for the use of customized dictionaries. Pennock-Roman and Rivera (Citation2011) revealed that dictionaries had a higher mean effect size for ELs when they were used with less restrictive time limits, and that effect sizes were more varied with more restrictive time limits. Furthermore, multiple studies have failed to find a significant effect for customized dictionaries. For example, Abedi (Citation2009; presented in more detail in Abedi, Courtney, & Leon, Citation2003b) found that customized dictionaries had only a slightly positive effect for ELs. The authors found that dictionaries had almost no effect on grade 4 ELs’ scores and a nonsignificant effect on grade 8 ELs’ scores.

Concerns over the feasibility of implementing customized dictionaries have also been raised. Abedi et al. (Citation2005) stated that the development of a customized dictionary is a complex and time-consuming task for school and test administrators. Careful attention must be paid when preparing the dictionary to avoid the inclusion of content-specific terms. Still, further evidence is needed to determine whether or not customized dictionaries are a consistently effective and valid accommodation for ELs.

Glossaries

Glossaries contain simplifications of non–content related terms and phrases deemed complex for students. These simplifications include clarifications of complex sentences and synonyms or specific, context-related definitions of words. What distinguishes a glossary from a dictionary is that the definitions provided in a glossary are specific to the context. For example, in a test question about an invoice, the word “bill” would include only that definition, and not the legislative definition.

Paper-Based Glossaries

Like dictionaries, paper-based glossaries have found traction among researchers as a potentially effective accommodation. Paper-based glossaries have been found to be effective for students with mid- to low-level English reading proficiency (Kiplinger et al., Citation2000). A caveat here is that a paper-based glossary is primarily effective only in instances where there is either ample or extended time included for the test, and it has been found that paper-based glossary use without this extra time can hinder ELs’ performances (Abedi et al., Citation2001; Abedi, Lord, Hofstetter, & Baker, Citation2000). Abedi et al. (Citation2001) posited that because students using the paper-based glossary need to take extra time to look up a given word, this accommodation is ineffective unless test administrators provide ample time for students to use the accommodation.

Pennock-Roman and Rivera (Citation2011) found a larger (significant) effect size for ELs using paper-based English and bilingual glossaries only when the studies they were used in provided extra time. Furthermore, the meta-analysis showed that studies using paper-based bilingual glossaries without extra time had a significant negative mean effect for ELs, in that the non-accommodated students had a higher score than those using the bilingual glossary.

Computer-Based Glossaries

Recent research has shown that computer-based pop-up glossaries are effective at narrowing the gap between ELs and non-ELs. A few studies have found positive results for computer-based pop-up glossaries. There has been little evidence of adverse influence on validity, and ELs have generally seen score increases when using this accommodation (Abedi, Citation2009; Kopriva, Emick, Hipolito-Delgado, & Cameron, Citation2007). In some experimental settings, this accommodation allows the researcher to track both the frequency and the duration of student access to the glosses. This can open further avenues of research into the use of accommodations, along with their effectiveness and influence on validity. Abedi (Citation2009) noted that the computer test administered to students recorded the frequency and duration student spent accessing glossed terms. ELs spent nearly three times longer reading glossed terms than non-ELs, and accessed glossaries on nearly twice as many words. In that experiment, it was also noted that students who were given the customized dictionary rarely noted when and for how long they used that accommodation.

Pennock-Roman and Rivera (Citation2011) found that pop-up glossaries had the largest mean effect size for ELs’ scores when compared to other direct linguistic support accommodations. Pop-up glossaries were the only accommodation found to have this effect without the need for extra time. For example, Abedi (Citation2009) used computer-based testing in an experimental study that randomized grade 4 ELs and non-ELs to receive either an original test, extra time, a computer-based test with a pop-up glossary, a customized dictionary, or small group testing. Grade 8 students received either an unaccommodated test, a computer-based test with a pop-up glossary, or a customized dictionary. Results showed that for ELs in both grades, those using computerized testing including the pop-up glossary saw a significantly higher score increase than those taking a non-accommodated test. Importantly, non-ELs did not see a similar increase in scores. It is important to note, however, that the computerized testing accommodation included, “an interactive set of accommodation features such as presentation of a single item at a time; a pop-up glossary; extra time; and a small and novel setting” (Abedi et al., Citation2003b, p. xi). Thus, the benefit seen in this study cannot be causally attributed to the pop-up glossary per se. It may have resulted from any one or some combination of the accommodations in the set.

Meta-analyses have found large effect sizes for pop-up glossaries, indicating their promise as an easy-to-use, effective, and valid accommodation for ELs to demonstrate their content knowledge without the constraint of linguistic difficulty (e.g., Abedi, Hofstetter, & Lord, Citation2004; Pennock-Roman & Rivera, Citation2011). However, it remains difficult to generalize these results. There has been limited work that has addressed the effectiveness and influence on validity of accommodations using field-based assessment, and there has been no study that has tested the influence of pop-up glossaries in isolation. Here, we assess the effectiveness and influence on validity of pop-up English language glossaries in a randomized, controlled design embedded within an operational statewide assessment. Previous work has identified a dearth of RCT-designed experiments in accommodation research (e.g., Abedi & Ewers, Citation2013). As such, our design serves as an answer to that call.

The Need for Randomized Controlled Trials in Assessing Accommodations

Overall there are only a limited number of studies providing supporting evidence for the effectiveness and influence on validity of direct linguistic support accommodations. Several studies have found a significant change in scores for EL/LEP students over their non-EL/LEP counterparts when using a given accommodation, only to have a subsequent study find no or insignificant results that recast doubt on that accommodation’s effectiveness.

Pennock-Roman and Rivera (Citation2011) stated that a possible reason a given accommodation’s effect size is small is because of the design of the assessment. Often, these tests are assembled from older released forms of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Because these tests are often assembled for the study itself, there may exist incongruences between the material included in the experiment’s test and what the students were learning in class. Kiplinger et al. (Citation2000) found a floor effect for the math test they assembled for their study, indicating that the items were much too difficult for the students. Abedi et al. (Citation2004) noted that even if the test items are derived using a given state’s standards, there is no sure way to evaluate that what is included in a test is what is being taught to ELs and non-ELs in the classroom. Finally, most of the research studies cited were relatively small scale designs in artificial testing environments (rather than a randomized field trial). As a result, it is difficult to generalize these results to large-scale assessments in real world settings.

Abedi and Ewers (Citation2013) reviewed the literature on accommodations for ELs and concluded that this lack of conclusive data results from limits on the experimental designs of the experiments that have been run. The authors stated that a randomized controlled trial is the “most convincing approach for examining the effectiveness, validity, and differential impact of accommodations” and that “research on the effectiveness and validity of accommodations using an RCT approach is scarce” (Abedi & Ewers, Citation2013, pp. 5–6).

The Current Study

Here, we conduct a large-scale, randomized controlled trial experiment to determine whether a variety of pop-up glossary accommodations for ELs are valid and effective. The study randomly embedded accommodations associated with field test items (items that do not count toward the students’ scores). By embedding the accommodations in (unscored) field test items, we are able to randomly assign students and items, thus controlling for internal and external threats to validity.

The present study was designed to advance the body of knowledge being amassed on the efficacy of computer-based pop-up glossaries. In addition to providing evidence about the effectiveness of this accommodation, we also sought to determine whether the impact of the accommodation varies across grades or subjects. This experiment addresses the main questions states ask when considering implementation accommodations (e.g., Abedi, Citation2009; Abedi et al., Citation2001, Citation2003a, Citation2005). Those questions include three main items:

Effectiveness: Does the accommodation provide assistance to an EL taking an assessment by reducing linguistic barriers, thus giving a more accurate measure of that student’s ability?

Influence on validity: Does the accommodation help ELs show their actual content knowledge without providing easier answers or changing the focal construct of an assessment?

Feasibility: How easy is the accommodation to implement?

Answering these questions is crucial to an accommodation’s adoption in education programs throughout the nation, as educators need to be sure that a given test accommodation effectively helps the students it’s designed to help without outright giving them the answers.

In this study, we have included ELA assessments—assessments where the focal construct is related to language. It has often been taken as a matter of faith that direct language supports would necessarily interact with the construct. We believe the impact of glossaries in ELA warrants study for two reasons. First, ELA test items are not immune from unnecessary language load that cause concern in other subjects (e.g., Johnstone, Liu, Altman, & Thurlow, Citation2007). Second, ELs can be challenged by culturally ubiquitous understandings that they have not yet absorbed (e.g., idioms). We see these cases as analogous to expecting non-EL examinees to bring specific technical knowledge that they may not have to the test. Glossaries can help provide access in the same way that glossing scientific terms not elucidated in the reading may increase access for non-EL students.

Methods

Participants

Participants comprised a representative sample of all grade 3 and 7 students taking a statewide accountability assessment online, which includes about half of students in each grade. ELs comprised approximately 12% of the grade 3 student population in the state, and about 5% of the grade 7 population. The vast majority, in excess of 75%, of ELs speak Spanish as their home language.

Students were sampled in two stages: Students were assigned field-test items randomly (using a pseudo-random number generator in the test delivery system), and a subset of those items were included in the study. During each operational administration, some new items are field tested for potential operational use in subsequent years, and a subset of these were included in the study.

All students who received items included in the study were themselves included in the study. Students in the study were assigned to the treatment (glossary) or control group based on a draw on a pseudo-random number, and assigned to the treatment group with a 50% probability. The participants comprise a representative sample of those students who tested online in the state.

The probability of inclusion in our sample depended on the number of field test items in the pool for each grade and subject, and some constraints on how they are selected for administration. Specifically, in math, individual items are sampled for administration, but many of the English language arts (ELA) items are associated with reading passages and are selected as a group. Study participation was randomly determined by the items (randomly) selected for administration, and this probability varied across tests. Our sample included approximately 25–50% of the students in the state. presents the number of students selected for the study.

Table 1. Number of students selected for the study by grade, subject, EL status, and experimental condition.

Stimuli

Items

Items were selected from the pool of items to be field-tested. In ELA, two reading passages were selected from each grade along with their associated items. In mathematics, individual items were selected, six of which were on the grade 3 test, and 13 of which appear on the grade 7 assessment. Items were selected based on the judgment of content-area experts who selected items for which glossaries were believed to be most likely to be helpful based on the use of unusual language and idioms.

Glossary

Pop-up English glossaries with audio were developed for the experimental items. The audio was limited to the glossary entries, and not information from the items. The development of the glossaries was standardized, with the guidelines precisely outlined in a training document. The glossary guidelines for mathematics were taken from the publicly available glossary guidelines developed by the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (Solano-Flores, Citation2012). These guidelines were developed by a committee of experts in the field, and widely vetted. Study staff adapted the same principles to create glossing guidelines for the ELA assessments.

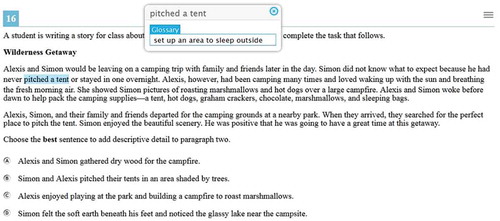

In brief, the primary goal of the glossary was to increase the effectiveness of the item to accurately assess the knowledge of ELs without affecting the construct of the item. This was accomplished by identifying non-construct related terms that may introduce confusion (e.g., polysemous words, low-frequency words, abstract words), and providing alternate forms of information (e.g., a word, phrase, clause) to provide understanding or meaning. All glossaries were written at or below the grade level of the student who would be reading them. presents an image of an example pop-up glossary.

The glossaries also contained an audio file that would be played (through headphones) when the student clicked a speaker icon. This allowed the student who had trouble reading the glossary to extract meaning from it. The audio file contained only the information included in the glossary and did not contain information that was on the test item itself.

Only a subset of items on the field test contained the glossary (and only for those in the glossary condition). As such, the computer presented instructions on how to use the glossary just prior to the glossed item being presented. The instructions were short and contained graphics. The instructions stated that that some help would be available on the next item. It stated that some words would contain a dashed line above and below the word. When the cursor was over that word, it would be highlighted in blue. If one clicked on the word, a dialogue box would pop up containing the word and some information about what the word means. The instructions showed a picture of the glossary and identified the speaker icon that can be clicked to hear the words on the glossary read aloud.

Procedure

The assessment of the effectiveness of the glossary was designed to be integrated into the standard statewide accountability testing procedures. As such, every student who took the assessment was randomly assigned to either the glossary condition or the no-glossary condition. Furthermore, the experimental items were randomly mixed in the field test item database. The students participated in the field test with the standard statewide accountability assessment rules, guidelines, and procedures. Importantly, the standard statewide accountability assessment is untimed. Finally, students with individual testing accommodations were provided their regular accommodations. The only difference was as follows:

If the computerized assessment randomly chose an experimental item and the student was in the pop-up English glossary condition, the instructions page described above was presented prior to the item being presented. When the student clicked the “next” button, the experimental item was presented. In the item, a subset of words were identified with a faint, dashed line above and below each glossed word. If the student moved their mouse over the word, it would be highlighted. If the student clicked on the word, a glossary dialogue box would pop up (as described above). After the student responded, the next question would be presented.

Data Analysis

The goal of the analysis was to determine whether the pop-up English glossaries were both valid (did not influence the scores of the non-ELs) and effective (improved the scores of the ELs).

To assess the influence on validity and the effectiveness of the pop-up English glossaries, we ran a mixed model probit analysis on the students’ responses to (a) the approximately 50 operational items on the test and (b) the experimental items included in the field test positions. The student’s binary score (correct or incorrect) was the criterion variable. Specifically,

where represents a vector of dummy variables indicating which item is the criterion;

is student i’s EL status (coded as 1 if the student is an English language learner), and t (treatment) takes on a value of one when the criterion item has a glossary available and zero otherwise. The final term in the index function is an interaction between EL status and treatment. The term

is the random effect representing the differences in student overall proficiency in the subject area.

With this setup, each observation reflects a single student’s score on a single item (one or zero), with a fixed effect controlling for differences in difficulty across items, and a random effect capturing the difference in achievement across students (the common influence on all the items taken by a given student).

The coefficient associated with the treatment term provides some information about the accommodation’s influence on validity—if it is non-zero, it suggests that the treatment (the glossaries) may affect the construct being measured. The interaction term indicates whether the glossaries have a different effect for ELs. The ideal language accommodation has no general effect, but a positive effect for ELs.

Results

Separate analyses were run on each assessment (math, ELA) by grade (3rd and 7th). and present the results. As expected, the mean performance of ELs was below that of non-ELs. In grade 3, pop-up English glossaries were associated with slightly lower performance for both math and ELA. Surprisingly, in both grades 3 and 7, glossaries on math tests seemed to depress the scores of ELs, although a similar trend was not apparent for ELA. In grade 7, glossaries on ELA tests increased the scores of ELs, while not influencing those of non-ELs. The magnitude of these effects are somewhat obscured by the nonlinear nature of the probit model. offers readers some comparisons among hypothetical students to illustrate these effects. Specifically, using hypothetical easy, medium, and difficult items we estimate the predicted probability of a correct response for

an average EL student presented with glossaries;

an average EL student not presented with glossaries;

an average non-EL student presented with glossaries; and

an average non-EL student not presented with glossaries.

Table 2. The coefficient estimates for the mixed model probit analysis by grade level on scores for the mathematics assessment.

Table 3. The coefficient estimates for the mixed model probit analysis by grade level on scores for the ELA assessment.

Table 4. Estimated probability of a correct response glossaries on hypothetical average students (EL and non-EL) with and without glossaries.

illustrates the estimated effects of the glossaries on these two groups of students.

These results make clear that the negative impact in grade 3 is relatively limited. Results for grade 7 show a substantial negative impact for math, but a neutral overall impact in ELA, with the glossaries associated with significant improvement for ELs.

Discussion

This randomized field trial revealed mixed results. In grade 3, the presence of glossaries appears to depress performance. In grade 7, we find different results for math and ELA. In math, the presence of glossaries seems to depress the performance of ELs, while in ELA it appears to enhance performance. Here, we assessed the effectiveness and influence on validity of pop-up English glossaries in a large-scale, randomized controlled trial conducted during the statewide accountability field test. The randomized controlled design in vivo is the gold standard to assess the effectiveness of such accommodations. We randomly assigned half the EL and non-ELs in the 3rd and 7th grades who were taking the statewide accountability assessment online to receive the accommodation.

As expected, ELs had lower scores than non-ELs. This is a relatively robust finding across published studies. We also found that the presence of the pop-up English glossary inhibited performance for all 3rd-grade students. The data also revealed that the pop-up English glossaries inhibited performance for ELs relative to non-ELs in Math assessment. Finally, for the 7th-grade ELA assessment, the pop-up glossary substantially improved performance for ELs without affecting the performance of other students who received the accommodation.

Our results conflict with some existing research, which have sometimes found positive results across grades and subjects (Abedi, Citation2009; Kopriva et al., Citation2007). However, these studies that have found positive results for accommodations that include pop-up glossaries have had few students in the glossary accommodation condition and were not designed to study pop-up glossaries per se. For example, Abedi’s (Citation2009; also presented as Abedi et al., Citation2003b) pop-up glossary accommodation was embedded in a larger “computerized accommodation” condition that had several co-occurring accommodations, including single item presentation, pop-up glossary, extra time, and a small, novel setting. Because there were several, co-occurring accommodations in the “computerized accommodation” condition, it is unclear whether the pop-up glossary produced the benefit that ELs experienced. Furthermore, Kopriva et al. (Citation2007) were primarily focused not on specific accommodations, but rather how ELs’ individual differences in educational needs affected their accommodation preferences. When researchers compared test results with recommendation results, they found a significant effect for the pop-up glossaries only when the students were recommended for that accommodation. Students who received inappropriate or no accommodations saw no significant score increases.

One key difference between the current study and those described above is that our study tested the unique effect of the pop-up English glossary. That is, in the previous studies, the pop-up English glossary was only one of several accommodations presented simultaneously to each student. As a result, any overall benefit from the accommodation condition could not be ascribed solely to the glossary accommodation. In contrast, the only difference between the glossary accommodation and the control condition in our study was the presence of the pop-up English glossary. As such, our design allows us to make a causal conclusion. Our study shows no clear benefit of the pop-up English glossary for ELs.

Another key difference in the design of the current study and those above was the use of a large-scale, randomized controlled design. Glossed test items were embedded as field test items into an assessment that was already set to be administered to students. Because the test used was already extant, this removed the need to assemble a test and thus reduced the risk of administering an assessment that contained material students either hadn’t been exposed to or was too difficult for them, as observed by Kiplinger et al. (Citation2000). Pennock-Roman and Rivera (Citation2011) noted that small effect sizes for given accommodations may not only reflect that accommodation’s effectiveness, but its effectiveness relative to the difficulty of the test. We note that our study included a variety of item difficulties, including some that most ELs got correct.

Tests with greater levels of difficulty may reduce how effective an accommodation is for ELs. This can result from the use of test material that students have no exposure to regardless of its presence on state content standards. This is not such an anomalous feat, as Abedi et al. (Citation2004) have stated that while an assessment can be derived using a state’s educational standards as a guideline, there is no reliable way to determine that what is on the test is what is being taught in a given classroom.

Building on this, our study was designed to test pop-up glossaries in a “real world” scenario. This real-world scenario was present in the 2015 operational administration of the statewide accountability assessments, which also offered us a chance to test a large state-level population. This removed the need to split students into even groups to receive an even and random distribution of glossaries, and allowed our results to be more generalizable given the large population using the accommodation. Because students were randomized to receive either the pop-up glossary or no accommodation, we controlled for external threats to validity. Furthermore, because the items were embedded into tests taken by all students, we were able to garner a more holistic perspective of student performance with accommodations, student performance as related to a student’s EL status, and grade-level performance as a measure of EL status and use of an accommodation. Since all students were exposed to both accommodated and non-accommodated test items, there was no risk of threats to the validity of the results based on how the student sample was collected or divided.

The current results suggest that pop-up English glossaries are potentially inhibitory for younger students. We see the inhibitory effect in the scores of the 3rd-graders and those taking the Math assessment. We are not the first to show the negative influence of glossaries on performance. For example, Pennock-Roman and Rivera’s (Citation2011) meta-analysis revealed that studies using paper-based bilingual glossaries without the use of extra time had a negative mean effect size, illustrating that the students performed worse in that accommodation category than those in the non-accommodated condition. Additionally, the meta-analysis found a nearly trivial mean effect size for studies using paper-based English glossaries alone, which only approached significance after extra time was included for ELs. These results indicate that the effectiveness of paper-based glossary is highly dependent on there being enough time available for students to use them.

The lack of a positive influence of the pop-up English glossaries for young students in the current experiment may result from the extra cognitive resources required when using a glossary in a real-world testing environment. By definition, when a pop-up glossary is present, there is more information and visual distraction present in the test item. This extra stimulus information requires attentional as well as memory resources to adequately process. As a result, the glossary may steal resources from those necessary to answer the question, thus reducing the student’s effectiveness at responding correctly.

This “cognitive load” hypothesis is consistent with our data that the glossaries inhibited the performance of the youngest students. These are the students with the least experience taking large-scale assessments, with the least cognitive maturity, and therefore the most vulnerable to the influence of extra cognitive load. Furthermore, these results are consistent with the hypothesized negative influence of paper and bilingual glossaries.

The balance struck between protecting the construct and providing access may contribute to the null results, especially in mathematics. By design, only words that were not relevant to the construct being measured were glossed. This may have diverted student attention towards the construct-irrelevant words, effectively misdirecting them. The alternative, glossing construct-relevant words, poses a high risk of modifying the construct being measured.

The one area in which we found the accommodation to be both effective and valid was in grade 7 ELA. Our study was designed to identify differences across grades and subjects—a necessary step before explaining them. However, post hoc analysis of our data provides some clues as to why we found different results in the middle school ELA test. These students may not be inhibited by the extra distraction imposed by the glossaries—their experience or cognitive maturity may protect them from this negative impact. Close examination of the words glossed across subjects indicates a stark difference between the math items and the ELA items. In math, test developers avoid metaphors, colloquialisms and other figurative language (i.e., expressions that deviate from their literal meaning). This, of course, is not so on a reading test. Correspondingly, glossed words and phrases were more than three times more likely to be metaphorical usages or colloquialisms in the ELA tests. In both grades, fewer than 10% of glossed words in math were figurative, while over 30% in ELA were. It seems reasonable that providing a literal interpretation of these phrases would support students the least familiar with their non-literal usages.

This explanation leaves us wondering about the inhibitory effect of glossaries in grade 7 math for ELs. Review of the glossed words revealed that the actual meaning of the glossed words was irrelevant to getting the item correct. As an example, consider a simple item that asks students how many strawberries two friends have, and lets them know that one friend has two and the other has four. The word strawberries could be replaced with gourds, walruses, or pancakes, and the answer would be the same. It may be that the glossary caused the student to focus too much on the meaning of the word, which in the math assessment is often irrelevant.

The current research provides several clues to the optimization of pop-up glossary accommodations. Future research should build on the current experiment by examining the impact of some of these factors. First, these accommodations should be designed to reduce cognitive load as much as possible. This may be accomplished through designing a visually simple user interface that obstructs as little of the item as possible. Second, exploring the impact of targeting low frequency and figurative language for pop-up glossaries. The current research suggests that glossaries may add to the cognitive load. Therefore, glossing fewer, more relevant, words may reduce the cognitive load the pop-up glossary itself, while retaining the benefit to the EL population. Our data suggests that glossing figurative words may produce benefits. Third, the meaning of the glossed words should be important to the understanding of the item. This criterion, together with the citerion that only construct irrelevant words should be glossed, may make it difficult to gloss math items. This is because well-written math items do not use metaphorical or colloquial language. As such, many of the words in math items are either construct relevant or the words meaning may not be very relevant to the item. As such, one may examine the influence of glossing construct relevant, but non-vocabulary words on construct validity. Finally, it may be that practice with the pop-up glossaries will automate its use, thus lowering the extra cognitive load it places on the student. Given the logistics of our large scale, randomized controlled design, we were unable to implement a practice test. Practice may be especially important for younger students. Future research should examine the impact of practice.

In sum, we conducted a large-scale, randomized controlled study to assess the influence on validity and effectiveness of pop-up English glossaries as accommodations for ELs. Our results revealed mixed results. In particular, we found some indication of a slight inhibitory influence for younger students and a benefit for older students in ELA. We hypothesize that any potential benefits of this accommodation for younger students may be mitigated by the increased cognitive load placed on students using the pop-up glossary. That is, the presence of a glossary may draw extra resources that could rather be used to focus on and correctly answer a given test item. We speculate that glossing metaphorical usages and colloquialisms may benefit ELs without risking construct-related validity of the test items, at least for older students.

Declaration of Interest

The third author is an executive for the American Institutes for Research, which publishes and delivers assessments.

Funding

This study received financial support from the American Institutes for Research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abedi, J. (2009). Computer testing as a form of accommodation for English language learners. Educational Assessment, 14, 195–211. doi:10.1080/10627190903448851

- Abedi, J., Courtney, M., & Leon, S. (2003a). Effectiveness and validity of accommodations for English language learners in large-scale assessments (CSE Technical Report 608). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

- Abedi, J., Courtney, M., & Leon, S. (2003b). Research-supported accommodation for English language learners in NAEP (CSE Technical Report 586). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

- Abedi, J., Courtney, M., Mirocha, J., Leon, S., & Goldberg, J. (2005). Language accommodations for English language learners in large-scale assessments: Bilingual dictionaries and linguistic modification (CSE Report 666). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

- Abedi, J., & Ewers, N. (2013). Accommodations for English language learners and students with disabilities: A research based decision algorithm. Retrieved from https://portal.smarterbalanced.org/library/en/accommodations-for-english-language-learners-and-students-with-disabilities-a-research-based-decision-algorithm.pdf

- Abedi, J., Hofstetter, C., Baker, E., & Lord, C. (2001). NAEP math performance and test accommodations: Interactions with student language background (CSE Technical Report 536). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

- Abedi, J., Hofstetter, C. H., & Lord, C. (2004). Assessment accommodations for English language learners: Implications for policy-based empirical research. Review of Educational Research, 74, 1–28. doi:10.3102/00346543074001001

- Abedi, J., Lord, C., Hofstetter, C., & Baker, E. (2000). Impact of accommodation strategies on English language learners’ test performance. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 19, 16–26. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3992.2000.tb00034.x

- Abedi, J., Lord, C., Kim, C., & Miyoshi, J. (2001). The effects of accommodations on the assessment of limited English proficient (LEP) students in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) (CSE Technical Report 537). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

- Abedi, J., Lord, C., & Plummer, J. (1997). Final report of language background as a variable in NAEP mathematics performance (CSE Technical Report 429). Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

- Albus, D., Thurlow, M., Liu, K., & Bielinski, J. (2005). Reading test performance of English-language learners using an English dictionary. The Journal of Educational Research, 98, 245–256. doi:10.3200/JOER.98.4.245-256

- Brown, P. (1999). Findings of the 1999 plain language field test: Inclusive comprehensive assessment system (Publication No. T99-013.1). Newark, DE: Delaware Education Research & Development Center.

- Coltrane, B. (2002). English language learners and high-stakes tests: An overview of the issues. Marion, IN: Indiana Wesleyan Center for Educational Excellence. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED470981)

- Council of Chief State School Officers. (2016). Major provisions of Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) related to the education of English learners. Retrieved from http://www.ccsso.org/Documents/2016/ESSA/CCSSOResourceonESSAELLs02.23.2016.pdf

- Johnson, E., & Monroe, B. (2004). Simplified language as an accommodation on math tests. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 29, 35–45. doi:10.1177/073724770402900303

- Johnstone, C., Liu, K., Altman, J., & Thurlow, M. (2007). Student think aloud reflections on comprehensible and readable assessment items: Perspectives on what does and does not make an item readable (Technical Report 48). Minneapolis, MN: National Center on Educational Outcomes, University of Minnesota.

- Kiplinger, V. L., Haug, C. A., & Abedi, J. (2000). Measuring math—not reading—on a math assessment: A language accommodation study of English language learners and other special populations. Marion, IN: Indiana Wesleyan Center for Educational Excellence. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED441813)

- Kopriva, R., Emick, J., Hipolito-Delgado, C., & Cameron, C. (2007). Do proper accommodation assignments make a difference? Examining the impact of improved decision making on scores for English language learners. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26, 11–20. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00097.x

- Menken, K. (2000). What are the critical issues in wide-scale assessment of English language learners? Marion, IN: Indiana Wesleyan Center for Educational Excellence. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED450595)

- Pennock-Roman, M., & Rivera, C. (2011). Mean effects of test accommodations for ELLs and non-ELLs: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30, 10–28. doi:10.1111/emip.2011.30.issue-3

- Rivera, C., & Collum, E. (2004). An analysis of state assessment policies addressing the accommodation of English language learners. Retrieved from https://www.nagb.org/content/nagb/assets/documents/publications/conferencesrivera.pdf

- Shafer Willner, L., Rivera, C., & Acosta, B. D. (2009). Ensuring accommodations used in content assessments are responsive to English‐language learners. The Reading Teacher, 62, 696–698. doi:10.1598/RT.62.8.8

- Solano-Flores, G. (2012). Translation accommodations framework for testing English language learners in mathematics. Retrieved from https://portal.smarterbalanced.org/library/en/translation-accommodations-framework-for-testing-english-language-learners-in-mathematics.pdf

- Young, J. W., & King, T. C. (2008). Testing accommodations for English language learners: A review of state and district policies. ETS Research Report Series, 2008, i–13. doi:10.1002/j.2333-8504.2008.tb02134.x