Abstract

To understand green consumption in cross-cultural context, this study examines the influence of horizontal individualism (HI-Finnish) and vertical collectivism (VC-Pakistani) cultural values on consumers’ attitude toward green products and purchase intentions. Besides, the mediating role of environmental responsibility is examined for the relationship between these cultural values and consumers’ attitude toward green products. Partial Least Square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis are performed to measure the significance of the hypothesized model and to assess differences between these two countries. This study empirically validates that these cultural variations can determine green consumption by consumers in each country. The results show an insignificant influence of horizontal individualism and vertical collectivism cultural values on consumers’ attitude toward green products, but a positive influence on environmental responsibility. The impact of environmental responsibility on consumers’ attitude toward green products and of their attitude toward green products on purchase intention was also positive. Environmental responsibility plays the role of a full mediator between cultural values and consumers’ attitude toward green products. The findings of this study may help practitioners in the development of culturally appropriate green marketing and advertising strategies.

Introduction

The world community is committed to limiting global temperature rise to less than 2 °C above preindustrial levels by the year 2100. However, reaching this goal will require major changes to current socioeconomic systems and consumption patterns. Sustainable Development Goal 12 outlines a shift in traditional methods of production and consumption of resources toward responsible and sustainable options subject to increasing our responsibility to protect the environment on behalf of both current and future generations (United Nations Citation2018). Accordingly, to alleviate environmental problems, businesses and consumers are both now showing their commitment. Businesses are increasingly integrating environmental policies and strategies into their activities, such as in the shape of designing, manufacturing, and distributing environmentally friendly/green products (Kolk and Pinkse 2004; Nidumolu, Prahalad, and Rangaswami Citation2009). Similarly, consumers are becoming more ecologically conscious and therefore buying environmentally friendly/green products and services, embracing a greener economy (Albino, Balice, and Dangelico Citation2009; Gouvea, Kassicieh, and Montoya Citation2013). Researchers find that in industrialized nations, more than 50% of individuals buy sustainable brands and 24% are ready to pay more for eco-products (Chen, Chen, and Tung Citation2018). At the same time, it has been found that the market share of green products around the world is declining by 1%–6%. (Nielsen Citation2013; Jahanshahi and Jia Citation2018). This means that some consumers are committed to buying green products whereas others resist sustainable consumption (Liobikienė and Juknys Citation2016).

Recent research suggests that the promotion of sustainable consumption requires study of the role of social and cultural aspects of consumption in the environmental concerns of consumers (da Costa et al. Citation2016). However, understanding culturally relevant pro-environmental behavior seems to be far more complex than was previously thought (Gifford and Nilsson Citation2014). In this context, for many years researchers believed that consumers in individualistic cultures buy and consume green products for self-interest and in collectivistic cultures for others-interest (McCarty and Shrum Citation2001; Laroche, Bergeron, and Barbaro-Forleo Citation2001; Milfont, Duckitt, and Cameron Citation2006). Accordingly, in differentiating individual vs. collective pro-environmental behavior across cultures, past research has relied on individualist vs. collectivist cultural values (Park, Russell, and Lee Citation2007; Soyez Citation2012). However, despite the research trend for many years classifying sustainable consumption for individual or collective reasons, it has been considered to be inconsistent and serve as a barrier in understanding consumers’ green motives (Morren and Grinstein Citation2016).

Because the concept of individual vs. collective-oriented behavior is situational, and it varies from one situation to another and from one time to another (Markus and Kitayama Citation1991), therefore when consumers consider sustainable choices, their absolute values may conflict or lack salience (van Zomeren Citation2014). Another possible reason could be that green products have attributes and features that serve consumers’ individual vs. collective reasons for consumption including benefit to health, status/image improvement, social concerns, and environmental concerns (Birch, Memery, and Kanakaratne Citation2018; Oliver and Lee Citation2010; Griskevicius, Tybur, and Van den Bergh Citation2010; Stern et al. Citation1995; Moisander Citation2007; Gupta and Ogden Citation2009). For that reason, a consumer, irrespective of their individual or collective cultural orientation, might prefer to buy and consume green products for individual and collective benefits, and for social, health, status improvement, and environmental motives.

Research further notes that negotiating the pro-environmental change can be difficult, especially when our consumption culture is fueling environmentally detrimental activities. That said, consumers have the power to change their own consumption to make it more eco-friendly, which would force companies to implement the responsible paradigm (Dursun Citation2019). The viability of the formation of environmentally responsible behavior is based on the conviction that it is possible to convince individuals accept their responsibility for causing environmental problems and therefore change their everyday actions to lessen the negative consequences (Barr Citation2003). Therefore, having a culture of environmental responsibility is a source of environmental protection (Lee, Kim, and Kim Citation2018).

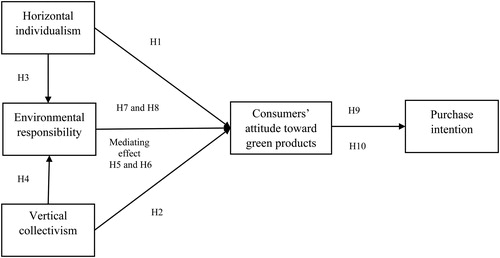

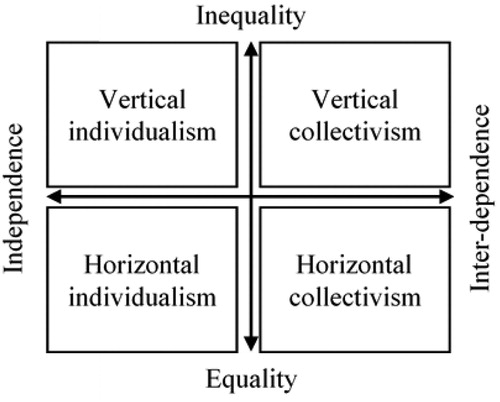

Against this background, the more general research aim of this study is to capitalize on the new refined conception of the classical individualism-collectivism dimension, namely its horizontal and vertical versions in an attempt to advance theorizing concerning cross-cultural differences in green consumption. More specifically, this study both applies more established conceptualizations (theories of planned behavior and value-belief-norm) and introduces an emerging mediation mechanism (environmental responsibility) for the effects of culturally shaped values. This exercise leads to the development of an integrative theoretical framework and a set of testable hypotheses (See ). Achievement of these objectives contributes to green customer behavior literature in four ways. First, it qualifies as an informed response to the continual calls by environmental psychologists to examine the role culture plays in human-environment interactions (Tam and Milfont Citation2020). Second, as revealed by the reviews of Shavitt and Cho (Citation2016), Shavitt and Barnes (Citation2019), the cultural differences dimensions of vertical individualism and horizontal collectivism - and not horizontal individualism and vertical collectivism - have received the greatest attention so far. In other words, our study helps to close that knowledge gap. Third, it provides the first empirical evidence regarding the ways in which environmental responsibility mediates the effects of horizontally individualistic and vertically collectivistic cultural values on various green consumption constructs (Minbashrazgah, Maleki, and Torabi Citation2017). The fourth contribution of this study is managerial. For example, effective marketing strategies require empirically robust and validated evidence of actual consumer behavior as well as an understanding of theoretical frameworks that best anticipate such behavior (Reisch et al. 2016). Accordingly, this study carries forward and examines key issues currently faced by marketers, such as how to design culturally congruent strategies and policy measures for marketing and selling green products in both industrialized and less-industrialized countries (Gifford and Nilsson Citation2014; Grebitus and Dumortier Citation2016; Nair and Little Citation2016).

In order to examine the proposed model, this study focuses on consumers’ of horizontal individualistic (low power distance and a higher degree of individualism; e.g., Finland) and vertical collectivistic (high power distance and a lower level of individualism; e.g., Pakistan) countries as an empirical research context (Hofstede-insights Citation2020; Rahman & Luomala 2020). According to Hofstede and Minkov (Citation2010), the individualism score (range 0–100) is 14 for Pakistan and 63 in Finland showing that the former is a collectivist and the latter is an individualistic country. In addition, the power distance dimension of cultural difference, which is the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power, is distributed unequally, pertains to how vertical or horizontal society is (Triandis and Gelfand Citation1998). This score (range 0–100) is 55 for Pakistan and 33 in Finland (Hofstede and Minkov Citation2010). Accordingly, the net difference of 22 suggests that Pakistani culture can be described as a vertical and Finnish culture is horizontal. Besides, previous studies offered evidence that Finland represents HI-culture and Pakistan is a VC-culture (Rantanen and Toikko Citation2017; Aycan et al. Citation2013). As mentioned above, prior research implies that both individualistic and collectivistic cultural values can be associated with self- and other-centered green consumption motivations. Specifically choosing Pakistan (a VC culture) and Finland (an HI culture) as the empirical research contexts for this study enables new insights concerning the ways and degrees in which culture and green consumption interact in different geographic locations and market environments. In the remainder of this study, we address the literature review, theoretical framework, hypotheses development, research methods, findings and results, and the discussion and conclusion of the study. Finally, theoretical and managerial implications, study limitations, and future research recommendations are discussed.

Literature review

Theoretical framework

This research is guided by the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the VBN theory (Ajzen Citation1991; De Groot and Steg Citation2008). The application of these two theories together has proved useful in predicting consumers’ pro-environmental and socially responsible behavior (Cho et al. Citation2013; Han Citation2015; Gkargkavouzi, Halkos, and Matsiori Citation2019). In the TPB framework, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude variables work together to shape an individual’s behavioral intentions and behaviors. VBN theory is an extended version of the norms activation model (NAM) (Schwartz Citation1977; Stern et al. Citation1999) and the new environmental paradigm (NEP) (Dunlap et al. Citation2000). In order to develop a VBN framework, Stern (Citation2000), merged three factors: awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms for NAM and ecological world factor of NEP in the pro-environmental context. The most important aspect of VBN is that beliefs play a mediating role between values and actions (De Groot and Steg Citation2008). In the context of environmental behavior, the role of mediating determinants between values, attitudes, and action must be considered (Thogersen, Zhou, & Huang 2016). In the current study, the merging of VBN and TPB gives us a conceptual framework in which HI and VC cultural orientations represent individual values; the environmental responsibility variable is a belief (Cho et al. Citation2013); and other constructs such as attitude and purchase intentions toward green products are actions (See ).

Horizontal/vertical individualism vs. collectivism cultural values

In consumer psychology, regarding the role of culture in predicting individual and collective consumer behavior, research at the cultural level involves the broad concept of IND vs. COL classification (Hofstede Citation1980; Shavitt, Johnson, and Zhang Citation2011; De Mooij and Hofstede Citation2011). However, researchers have disagreed and argued that it is not necessarily true that a culture can be congruent with IND/COL cultural values. The IND/COL continuum explains a slight variation but cannot capture enough cultural difference to make any credible recommendations (Oyserman, Coon, and Kemmelmeier Citation2002). Singelis et al. (Citation1995), and Triandis and Gelfand (Citation1998) treated and operationalized IND/COL cultures as vertical vs. horizontal. H/V IND/COL nested in IND/COL orientations predict different personal values, goals, normative expectations, and power concepts (Triandis Citation1995) (See ). The authors divided IND/COL orientations into four distinct cultural patterns. For example, (a) vertical individualistic (VI) (France, Great Britain and the United States, where people emphasize hierarchy, power, individual competition, and being different and notable, (b) horizontal individualistic (HI) (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Australia), where people emphasize equality, independence, self-reliance, and uniqueness. Also, (c) vertical collectivistic (VC) (India, Japan, Korea) where people are submissive, comply with authority, preserve unity, prioritize group benefits, goals and interests, and accept inequality, and (d) horizontal collectivistic (HC) where people emphasize equity, group commonality, sociability, and interdependence. H/V IND-COL patterns resemble the combination of the scores for Hofstede’s dimensions, (e.g., individualism/collectivism and power distance) (Shavitt and Cho Citation2016). Moreover, H/V IND-COL cultural individuals may achieve different, culturally relevant goals (Triandis Citation1995; Shavitt and Cho Citation2016). For example, self-respect (e.g., being proud and confident of oneself) is congruent with HI being distinct and separate from others. Being well respected/admired (e.g., being admired and recognized by others) is the hallmark of VC cultural values such as maintaining and protecting in-group status (Shavitt et al. Citation2006, p. 327). In the field of consumer behavior, H/V IND-COL societies are structured around specific dominant attitudes. How consumers react to advertisements, brands, and service providers in the marketplace, and their responses to others and to the needs of others, are based on H/V IND-COL orientations (Shavitt, Johnson, and Zhang Citation2011). For example, VI-oriented consumers are brand and status-conscious and hate lying (Lu, Chang, and Yu Citation2013; Zhang and Nelson Citation2016), whereas consumers of HC cultures are interested in cause-related marketing, and show leisure attitudes (Wang Citation2014; Wong, Newton, and Newton Citation2014).

Figure 2. H/V IND vs COL (Triandis and Gelfand Citation1998).

Hypotheses development

Horizontal IND vs. Vertical COL and consumers’ attitude toward green products

Up to the present time, not much attention has been paid by researchers to the role of HI and VC cultural values in consumer behavior research. According to Shavitt and Barnes (Citation2019), most of the research addressed the influence of VI and HC values as compared to HI and VC in various consumption phenomena. In addition, few studies addressed HI and VC cultural orientations in the context of pro-environmental behavior (Cho et al. Citation2013; Rahman Citation2019; Gupta, Wencke, and Gentry Citation2019). Previous research demonstrates that consumers with VC cultural values show pro-environmental attitudes and are prone to other-directed symbolism (Waylen et al. Citation2012; Yi-Cheon Yim et al. Citation2014). However, consumers with HI cultural values display an impersonal interest in nutritional practices and show environmental attitudes (Cho et al. Citation2013; Parker and Grinter Citation2014). Accordingly, this study assumes that there can be a potential influence of HI and VC cultural-congruent values on consumers’ attitude toward green products. Therefore, it is hypothesized that,

H1. HI cultural values positively influence consumers’ attitude toward green products

H2. VC cultural values positively influence consumers’ attitude toward green products

Horizontal IND vs. Vertical COL and environmental responsibility

Consumers are becoming more willing to solve problems and accept environmental responsibility in terms of personal habits, lifestyles, and purchases (Knopman, Susman, and Landy Citation1999; Paco and Gouveia Rodrigues 2016; Kinnear, Taylor, and Ahmed Citation1974; Follows and Jober Citation2000). Researchers further argue that environmentally responsible individuals are different with respect to their values and personality profiles and that environmental responsibility varies across different cultures (Schultz Citation2002; Dagher and Itani Citation2014), specifically across individualistic versus collectivistic cultures (Hanson-Ramussen and Lauver 2018). Several researchers have established that environmentally responsible consumers not only see an improvement in their image, but also project a good image of themselves as environmentally responsible in the opinion of others (Nyborg, Howarth, and Brekke Citation2006; Lee Citation2009). These research findings are compatible with the conceptual definitions of how HI and VC cultural-oriented consumers see themselves. From these research findings, it is inferred that an “environmentally responsible” consumer in a HI culture may project her/himself as being environmentally responsible for self-image/uniqueness in society, and VC consumers will see themselves as an environmentally-friendly, admired persons in the eyes of others, having in-group-status. Accordingly, we hypothesize that

H3. HI cultural values positively influence consumers’ environmental responsibility

H4. VC cultural values positively influence consumers’ environmental responsibility

H5. HI-culture relevant environmental responsibility plays the role of a mediating variable in the relationship between HI cultural values and consumers’ attitude toward green products

H6. VC-culture relevant environmental responsibility plays the role of a mediating variable in the relationship between VC cultural values and consumers’ attitude toward green products

Environmental responsibility and consumers’ attitude toward green products

According to Schwartz (Citation1968), perceived responsibility for environmental damage refers to the degree to which a person believes that he or she is directly or indirectly responsible for harming the environment. Environmental responsibility featured in the value-belief-norm (VBN) model (Stern et al. Citation1999) and a better predictor of consumers’ sustainable behaviors (Luchs, Phipps, and Hill Citation2015), but has been generally neglected by researchers in predicting pro-environmental behavior (Attaran and Celik Citation2015; Wells, Ponting, and Peattie Citation2011).

Environmental responsibility positively influences and predicts consumers’ environmental attitudes (Taufique et al. Citation2014; Paco and Gouveia Rodrigues 2016) that eventually translate into positive green purchase behavior (Lee Citation2009). In their study, Attaran and Celik (Citation2015) found that consumers with a high level of environmental responsibility show favorable attitudes and purchase intentions. Previous research also shows that responsibility toward environmental protection leads consumers to evaluate and form opinions regarding the purchasing of green products (Kanchanapibul et al. Citation2014; Miniero et al. Citation2014). Moreover, environmentally responsible consumers would be ready to be green and purchase green products (Arli et al. Citation2018). For example, they would buy lower emission vehicles (Ngo, West, and Calkins Citation2009). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that

H7. Environmental responsibility positively influences HI consumers’ attitude toward green products

H8. Environmental responsibility positively influences VC consumers’ attitude toward green products

Consumers’ attitude toward green products and purchase intention

Attitude refers to the degree to which a person forms a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior in question (Ajzen Citation1991). Attitude is an important predictor of behavioral intentions (Kotchen and Reiling Citation2000). In the context of tourism research, consumers’ attitude positively determines their green hotel intentions (Han and Yoon Citation2015). Similarly, consumers’ attitude toward organic products positively influences their purchase intentions. Tang, Wang, and Lu (Citation2014) found that consumers’ attitude toward low carbon emitting products positively influences their purchase intentions of these products. Paul, Modi, and Patel (Citation2016) and Sreen, Purbey, and Sadarangani (2018) found that consumers’ attitude toward green products positively influences their purchase intentions. Moreover, consumers’ cultural characteristics can explain the positive link of their attitude and intention with environmentally friendly products (Morren and Grinstein Citation2016). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that,

H9. In a HI-culture, consumers’ attitude toward green products has a positive influence on their purchase intentions

H10. In a VC-culture, consumers’ attitude toward green products has a positive influence on their purchase intentions

Methodology

Measures and sample

The questionnaire in this study has two parts. The first part contains the underlying independent and dependent variables. The second part consists of demographic information about the respondents, such as age, gender, marital status, educational qualifications, and income level. Scale items of the variables are adapted from earlier studies. For instance, the scale items for “horizontal individualism” (HI) (e.g., “I’d rather depend on myself than others”) and “vertical collectivism” (VC) (e.g., “It is important to me that I respect the decisions made by my group”), value orientations, are taken from the study by Triandis and Gelfand (Citation1998). Questions relating to the mediating variable “environmental responsibility” (ER) (e.g., “I should be responsible for protecting our environment”) are taken from the study by Lee (Citation2009). Scale items for the “consumers’ attitude toward green products” (CAGP) (e.g., “I like the idea of purchasing green products”), are taken from the study by Mostafa (Citation2007), and scale items of “purchase intention” (PI) variable (e.g., “I definitely want to purchase green products in the near future”) are taken from the study by Paul, Modi, and Patel (Citation2016). All scale items were measured using a Likert scale of “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

Data collection procedure

Before participating in the survey, the purpose and objectives of the research were explained to the respondents. The questionnaires were translated into Urdu for the Pakistani respondents and Finnish for the Finnish respondents. Moreover, to give an accurate depiction of the exact meaning of the text of the questionnaire in the target languages of both countries, we followed the back translation method (Tyupa Citation2011). A non-probability convenience sampling technique was used to collect the data. Participants were recruited in public places such as parks, malls, city centers, and educational institutes. We used the same data collection technique in both countries. A total number of 172 completed questionnaires were obtained from Pakistani respondents living in the cities of Rawalpindi and Islamabad. In Finland, 193 responses were obtained from residents of the cities of Helsinki and Vaasa.

Data analysis

The collected data were examined using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 20.0). Data were scrutinized for missing and unclear values, and these were removed. Furthermore, to analyze the data and to check the hypothesized relationships and fitness of the model, we used the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique, using the partial least squares (PLS) SmartPLS (v. 3.2.6) software application (Hair et al. Citation2006). PLS is a prediction-oriented SEM-based software package that works with smaller data sets (Henseler, Ringle, and Sinkovics Citation2009).

Results and findings

Sample characteristics

In Pakistan, the majority of the respondents were aged between 26 and 40 years (n = 93, 54.1%); in the Finnish sample, they were aged between 21 and 35 years (n = 97, 50.3%). There were more female respondents in the Finnish sample than males (n = 143, 74.1%). The number of unmarried respondents was almost the same in both samples (Pakistan, 105, 61.1%, Finland, 106, 54.92%). In the Pakistani sample there were 60 (n = 60, 34.88%) bachelor’s degree holders, but in the Finnish sample this number was 77 (n = 77, 39.90%). The monthly income level of the respondents in Pakistan was between Pakistani rupees (PKR) 10,000 − 30,000 (n = 122, 70.93%), and in Finland, the income level was €501 - €2,499 (n = 126, 65.28%).

Variation of dependent variables

To analyze the differences between Pakistani and Finnish groups, we used an independent t-test. Test results show a significant difference between the two groups (See ).

Table 1. Independent t-test comparing Finland-HI and Pakistan-VC samples.

Correlation, reliability, and discriminant validity of measures

For interrelationships between the variables, we established a correlation. To evaluate the convergent validity, we computed the average variance extracted (AVE), and for the reliability of the measures, we calculated the composite reliability (CR). Moreover, we found adequate discriminant validity using the square root of AVEs exceeding the correlation coefficients between pairs of corresponding constructs (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981) (See and ).

Table 2. Discriminant validity and correlation (Finland).

Table 3. Discriminant validity and correlation (Pakistan).

Structural equation modelling analysis

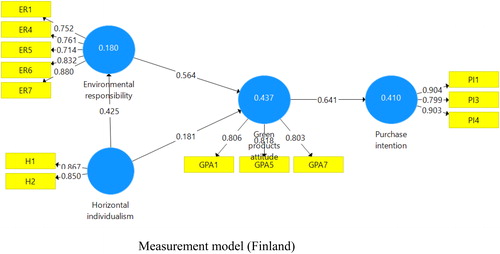

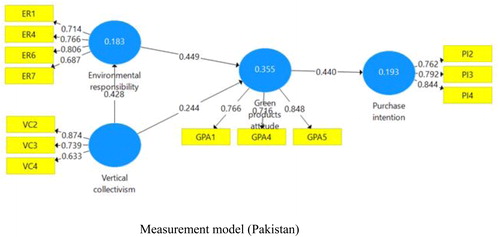

Measurement model

The loadings of the measurement model for the five latent variables show adequate convergent validity, indicating acceptable internal consistency and validity above the recommended value of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981) (See and ).

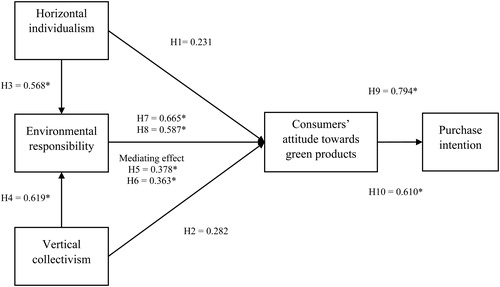

Structural model and hypotheses results

A structural model was used to assess the hypothesized relationships of the constructs. A coefficient of determination R2 was calculated as the first step of the structural model. This shows the amount of variance in a dependent variable via an independent variable using path coefficients and their corresponding significance scores. In the model for Finland, the R2 value for ER is 18%, for CAGP it is 44%, and for PI it is 41%. In the model for Pakistan, the R2 value for ER is 18%, for CAGP it is 36%, and it is 19% for PI, demonstrating considerable significance for the interpretation of the variance (Chin Citation1998). In the next step, to test the prediction relevance of the models, the Q2 value, a cross-validated redundancy measure, was calculated using the blindfolding command. The resulting values of Q2 for the Finland data model are 10% for ER, 26% for CAGP, and 28% for PI. The Q2 results for the Pakistan data model are 9% for ER, 19% for CAGP, and 11% for PI. All the Q2 values in the two models demonstrate that the observed values are well reconstructed and that the model has predictive relevance (Henseler, Ringle, and Sinkovics Citation2009).

To determine the strengths of the direct and indirect hypothesized effects between the variables of the model using path coefficients and t-values, a bootstrapping method for sampling tests was run on the data of both countries, based on 1,000 bootstraps in PLS (Roldán and Sanchez-Franco 2012). Moreover, for the mediating variable analysis, we used specific indirect effect, as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2017), which we chose for convenience and reliability (Cepeda, Nitzl, and Roldán Citation2017). Data results reveal that in Finland, H1 is not supported due to the insignificant influence of HI cultural values on CAGP (β = 0.231, p > 0.05). However, the influence of HI cultural values on ER (β = 0.568, p < 0.05) is positive, therefore H3 is supported. Data results further show that ER positively influences CAGP (β = 0.665, p < 0.05) so H7 is supported. The influence of CAGP on PI in the Finnish sample is also positive (β = 0.794, p < 0.05), and therefore H9 is supported. Regarding the hypothesis results in Pakistan, the influence of VC cultural values on CAGP is not significant (β = 0.282, p > 0.05). Therefore H2 is not supported, but the VC → ER path is significant (β = 0.619, p < 0.05), and thus H4 is supported. Because the influence of ER on CAGP is significant and positive (β = 0.587, p < 0.05) therefore H8 is supported. The influence of CAGP on PI in Pakistan was also found to be positive and significant. Therefore H10 is supported (β = 0.610, p < 0.05). Regarding the mediating factor analysis, we support H5 and H6: the resulting values of specific indirect effects show that ER plays the role of a full mediator between HI and VC cultural values (β = 0.378, p < 0.05), VC (β = 0.363, p < 0.05) and CAGP (See and ).

Table 4. Hypotheses result.

Discussion

Change in consumers’ unsustainable consumption patterns is essential for sustainable consumption and production goals. In this situation, understanding consumers’ culturally relevant buying and consumption motives may help to promote pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, this study expanded the long-standing history of the role of cultural value orientations in environmental behavior research, thereby extending the current research debate on understanding consumers’ green product preferences in a cross-cultural context. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to examine the influence of the horizontal individualism and vertical collectivism facets of horizontal vs. vertical IND and COL cultural orientations on consumers’ attitude toward green product and purchase intentions. In addition to that, the present study attempted to provide empirical evidence regarding the ways in which environmental responsibility mediates the effects of horizontally individualistic and vertically collectivistic cultural values on consumers’ attitude toward green products. The data provide support for our proposed research model and many of our hypotheses. As expected, the measurement scores on cultural values indicate that Pakistanis are vertical collectivist and Finnish are horizontal individualists. Based on the results of the hypotheses, we establish an insignificant influence of vertical collectivism (Pakistan) and horizontal individualism (Finland) on consumers’ attitude toward green products. However, consumers’ attitude toward green products is significantly driven by their environmental responsibility belief in these two countries. Moreover, in Pakistan and in Finland HI environmental responsibility uniquely and theoretically consistently mediates the effects of HI- and VC-culture-specific values on consumers’ attitudes toward green products.

Theoretical and practical implications

This study contributes by advancing the culturally informed understanding of human–environment interaction research as well as by helping managers to design culturally relevant international green marketing and advertising strategies. Consequently, by taking closer look at the results of this study, several salient theoretical and managerial implications are derived. The results show an insignificant influence of HI and VC cultural values on consumers’ attitude toward green products. This result demonstrates that HI vs. VC consumers may have the opinion that consuming green products may not be beneficial in terms of their cultural motives, or they may find it inconvenient to change learned consumption patterns and habits (Morwitz, Steckel, and Gupta Citation2007), showing an attitude-behavior gap (Liobikiene and Juknys 2016). However, when environmental responsibility was introduced between these relationships as a mediator variable, we found a positive influence of HI and VC on ER in both countries. In addition, ER positively influences consumers’ attitude toward green products (Attaran and Celik Citation2015; Miniero et al. Citation2014). Environmental responsibility further plays the role of a full mediator in the relationship between HI and VC cultural values and consumers’ attitude toward green products. These results are theoretically interesting, and they are consistent with earlier research that environmental responsibility varies in IND vs. COL cultures (Hanson-Ramussen and Lauver 2018). In this study, the direct influence of HI and VC on ER and the mediating effect of ER between these cultural values and consumers’ attitude toward green product results clearly show that consumers display HI and VC cultural-congruent environmental responsibility, thereby protecting the environment (Nyborg, Howarth, and Brekke Citation2006; Lee Citation2009). From a theoretical point of view, this study infers that consumers in both cultures show environmentally responsible behavior (Paco and Gouveia Rodrigues 2016), and that they are actively involved in issues that relate to environmental protection, and ultimately show positive green products attitude (Taufique et al. Citation2014). Translating these results, we infer that environmentally responsible consumers see an improvement in their image (to be unique and distinct) in HI culture, and project a good image of themselves as an environmentally responsible person in the opinion of others in the VC culture (in-group status and being admired) (Nyborg, Howarth, and Brekke Citation2006; Lee Citation2009; Shavitt et al. Citation2006). The results further reveal a positive impact of consumers’ attitude toward green product on PI in these two countries (Morren and Grinstein Citation2016). This result indicates that consumers in HI and VC cultures are ready to change their purchasing patterns for the sake of the environment (Kinnear, Taylor, and Ahmed Citation1974; Follows and Jober 2000) and that their attitude successfully translates into green purchase intentions. Previous studies have noted that even the individuals who are aware of and in fact concerned about environmental issues, engage in behaviors that may not reflect this awareness and concern (Costarelli and Colloca Citation2004). However, results of this study indicate that individuals embedded in the HI- and VC-cultures have an awareness of their responsibilities toward the environment and are more likely to purchase green products (Kumar and Ghodeswar Citation2015; Lee Citation2009). Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that this study empirically demonstrated how to translate the HI- and VC- culture-specific values and environmental responsibility into purchase green products (Tam and Milfont Citation2020; Morren and Grinstein Citation2016).

The findings of this study further provide implications for product development, consumer segmentation, advertising, and promotion strategies for manufacturers, producers, and marketers of green products. Because environmental responsibility facilitates HI and VC cultural values in consumers’ attitude toward green products, consequently, in their purchase intentions, marketers should use specific advertising and promotion messages in HI and VC cultures. For example, the characteristics of the VC-Pakistan cultural consumer segment include displaying social status and in-group/family obligations, and therefore being eco-conscious could be a new status symbol for such consumers. Marketers and advertisers should insert such messages in the content of print and media advertisements to appeal to those who wish to enhance their status, thereby promoting the purchase and consumption of green products. In addition, marketers should not try to sway consumers based only on the economic and status benefits of green products. They should also highlight the importance of buying such products for the benefit of their family and the current and future generations. In this regard, marketing managers can attempt to use cause-related, socially responsible, environmentally friendly, and mindful consumption messages in green advertising to stimulate the demand for green products. Regarding HI-Finland, to attract consumers, marketers need to embed HI-congruent content, such as using appeals to uniqueness and self-reliance in their advertisements and promotions. The messages could be the merits of appearing unique in one’s surroundings or representing self-reliance in protecting the environment when buying and consuming green products. Moreover, marketers can penetrate HI cultures using environmentally and socially responsible marketing strategies more easily than when introducing products using signals about the benefits of the product itself. We further suggest multinationals to start adapting their green marketing and advertising strategies to prevailing vertical collectivist and horizontal individualist cultural values in the selected countries for green brand equity formation, market share, to achieve green competitive advantage, and improved business performance.

Limitations and future research recommendations

Although considerable conceptual and methodological effort and attention has been expended on examining the cross-cultural HI and VC differences in consumers’ environmental behavior, this study still cannot claim to be entirely free from limitations. The limitations of this study provide opportunities for future research on the topic. First, as many studies in consumer behavior, our research also relied on the self-report methodology. Especially in relation to green consumption issues, socially desirable responding can hamper its reliability. Green attitudes and behaviors can be over-reported to convey an ideal picture of oneself to others (see e.g., Binder and Blankenberg Citation2017). Thus, when asked directly via self-reporting measures, consumers typically express more socially approved green choice motivations such as health, safety, environmental friendliness and animal welfare - and downplay more reproachable ones such as status drives (Luomala et al. Citation2020). So, methodological triangulation is needed to form a more comprehensive understanding of both direct and indirect cultural influences on green consumption. Priming experiments represent a viable approach to gather more concrete behavioral data. For example, various cultural values or goals can be primed and the effects on actual product choices or consumption experiences can be analyzed (cf. Puska et al. Citation2018). Second, the insignificant influence of HI vs. VC on CAGP generates an opportunity for future research to test this using a larger sample size, employing different data collection techniques and methods of analysis with more than one green product category, and a multi-country or cross-country market context, e.g., western vs. non-western countries, to compare the results for similarities and differences. It would be interesting to employ a qualitative research methodology to explore the factors that would further explain if this insignificant relationship is situational or permanent. Third, to be green may be a difficult decision for a consumer to make (Wells, Ponting, and Peattie Citation2011). Future research can examine the role of factors that either mediate or moderate the green attitude-intention relationship such as ethical responsibility, religious principles and practices, and minimalism factors, to know how these factors would help consumers to buy green products. Fourth, the demography, economic development, and population of the selected countries in this study are different. In the future, research on green consumption should be conducted in countries that are similar regarding these factors. Fourth, as this research has not aimed to examine the role of respondents’ demographic differences, future research could measure the moderating effect of gender, income, and education of consumers on green products preferences. Fifth, technological and information development are changing in H/V IND vs. COL cultures, and ultimately the patterns of consumption are changing. Therefore, in the context of sustainable consumption, an interesting area would be to examine the impact of technological advancements such as internet and mobile technology devices on the consumption patterns of consumers of these cultures. Sixth, it is possible that there are cultural similarities and differences due to the diverse populations of the selected countries. Future research could include other countries. Future research should examine rural as well as urban areas and then compare the populations to determine the HI, VC, also HC and VI culture-level differences, and determine the cultural reasons for consumers’ preference for green products. Last, future studies on advertising could use horizontal and vertical IND/COL culturally relevant message frames and appeals to consumers’ attitudes and intention to purchase of both low-involvement and high-involvement green, organic, and renewable energy products in the countries structured around HI, VC, HC and VI cultural groups.

References

- Ajzen, I. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2):179–211. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Albino, V., A. Balice, and R. M. Dangelico. 2009. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability‐driven companies. Business Strategy and the Environment 18 (2):83–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.638.

- Arli, D., L. P. Tan, F. Tjiptono, and L. Yang. 2018. Exploring consumers’ purchase intention towards green products in an emerging market: The role of consumers’ perceived readiness. International Journal of Consumer Studies 42 (4):389–401. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12432.

- Attaran, S., and B. G. Celik. 2015. Students’ environmental responsibility and their willingness to pay for green buildings. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 16 (3):327–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-04-2013-0029.

- Aycan, Z., B. Schyns, J. M. Sun, J. Felfe, and N. Saher. 2013. Convergence and divergence of paternalistic leadership: A cross-cultural investigation of prototypes. Journal of International Business Studies 44 (9):962–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.48.

- Barr, S. 2003. Strategies for sustainability: Citizens and responsible environmental behavior. Area 35 (3):227–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4762.00172.

- Binder, M., and A. K. Blankenberg. 2017. Green lifestyles and subjective well-being: More about self-image than actual behavior? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 137:304–23.

- Birch, D., J. Memery, and M. D. S. Kanakaratne. 2018. The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 40:221–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.013.

- Cepeda, G., C. Nitzl, and J. L. Roldán. 2017. Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples. In Partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications, eds. H. Latan and R. Noonan, 173–95. Cham: Springer.

- Chen, C. C., C. W. Chen, and Y. C. Tung. 2018. Exploring the consumer behaviour of intention to purchase green products in Belt and Road Countries: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 10 (3):854. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030854.

- Chin, W. W. 1998. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern methods for business research, ed. G. A. Marcoulides, 295–358. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cho, Y. N., A. Thyroff, M. I. Rapert, S. Y. Park, and H. J. Lee. 2013. To be or not to be green: Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behaviour. Journal of Business Research 66 (8):1052–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.020.

- Costarelli, S., and P. Colloca. 2004. The effects of attitudinal ambivalence on pro-environmental behavioural intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (3):279–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.06.001.

- da Costa, J. P., P. S. Santos, A. C. Duarte, and T. Rocha-Santos. 2016. (Nano) plastics in the environment–sources, fates and effects. Science of the Total Environment 566–567:15–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.041.

- Dagher, G. K., and O. Itani. 2014. Factors influencing green purchasing behaviour: Empirical evidence from the Lebanese consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 13 (3):188–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1482.

- De Groot, J. I., and L. Steg. 2008. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior 40 (3):330–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506297831.

- De Mooij, M., and G. Hofstede. 2011. Cross-cultural consumer behaviour: A review of research findings. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 23 (3/4):181–92.

- Dunlap, R. E., K. D. Van Liere, A. G. Mertig, and R. E. Jones. 2000. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues 56 (3):425–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176.

- Dursun, I. 2019. Psychological barriers to environmentally responsible consumption. In Ethics, social responsibility and sustainability in marketing, eds. Ipek Farina, Sebnem Burnaz, 103–28. Singapore: Springer.

- Follows, S. B., and D. Jobber. 2000. Environmentally responsible purchase behaviour: A test of a consumer model. European Journal of Marketing 34 (5–6):723–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560010322009.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1):39–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Gifford, R., and A. Nilsson. 2014. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review . International Journal of Psychology : Journal International de Psychologie 49 (3):141–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12034.

- Gkargkavouzi, A., G. Halkos, and S. Matsiori. 2019. Environmental behavior in a private-sphere context: Integrating theories of planned behavior and value belief norm, self-identity and habit. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 148:145–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.01.039.

- Gouvea, R., S. Kassicieh, and M. J. Montoya. 2013. Using the quadruple helix to design strategies for the green economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 80 (2):221–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.05.003.

- Grebitus, C., and J. Dumortier. 2016. Effects of values and personality on demand for organic produce. Agribusiness 32 (2):189–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21445.

- Griskevicius, V., J. M. Tybur, and B. Van den Bergh. 2010. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (3):392–404. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017346.

- Gupta, S., and D. T. Ogden. 2009. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. Journal of Consumer Marketing 26 (6):376–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760910988201.

- Gupta, S., G. Wencke, and J. Gentry. 2019. The role of style versus fashion orientation on sustainable apparel consumption. Journal of Macromarketing 39 (2):188–207. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146719835283.

- Hair, J. F., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, R. E. Anderson, and R. L. Tatham. 2006. Multivariate data analysis, vol. 6. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2017. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Han, H. 2015. Travelers' pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management 47:164–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.014.

- Hanson-Rasmussen, N. J., and K. J. Lauver. 2018. Environmental responsibility: Millennial values and cultural dimensions. Journal of Global Responsibility 9 (1):6–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-06-2017-0039.

- Han, H., and H. J. Yoon. 2015. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. International Journal of Hospitality Management 45:22–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.11.004.

- Henseler, J., C. M. Ringle, and R. R. Sinkovics. 2009. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing (Advances in International Marketing, Vol. 20), eds. R. R. Sinkovics, P. N. Ghauri, 277–319. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hofstede, G. 1980. Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics 9 (1):42–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(80)90013-3.

- Hofstede, G., and M. Minkov. 2010. Long-versus short-term orientation: New perspectives. Asia Pacific Business Review 16 (4):493–504. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381003637609.

- Hofstede-insights. 2020. Country comparison, Finland and Pakistan. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/finland,pakistan/

- Jahanshahi, A. A., and J. Jia. 2018. Purchasing green products as a means of expressing consumers’ uniqueness: Empirical evidence from Peru and Bangladesh. Sustainability 10 (11):4062. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114062.

- Kanchanapibul, M., E. Lacka, X. Wang, and H. K. Chan. 2014. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. Journal of Cleaner Production 66:528–536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.062.

- Kinnear, T. C., J. R. Taylor, and S. A. Ahmed. 1974. Ecologically concerned consumers: Who are they? Ecologically concerned consumers can be identified. Journal of Marketing 38 (2):20–24.

- Knopman, D. S., M. M. Susman, and M. K. Landy. 1999. Civic environmentalism. Environment 41:24–32.

- Kolk, A., and J. Pinkse. 2004. Market strategies for climate change. European Management Journal 22 (3):304–314. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2004.04.011.

- Kotchen, M. J., and S. D. Reiling. 2000. Environmental attitudes, motivations, and contingent valuation of nonuse values: A case study involving endangered species. Ecological Economics 32 (1):93–107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00069-5.

- Kumar, P., and B. M. Ghodeswar. 2015. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 33 (3):330–347.

- Laroche, M., J. Bergeron, and G. Barbaro-Forleo. 2001. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. Journal of Consumer Marketing 18 (6):503–520. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006155.

- Lee, K. 2009. Gender differences in Hong Kong adolescent consumers’ green purchasing behaviour. Journal of Consumer Marketing 26 (2):87–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760910940456.

- Lee, J. W., Y. M. Kim, and Y. E. Kim. 2018. Antecedents of adopting corporate environmental responsibility and green practices. Journal of Business Ethics 148 (2):397–409. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3024-y.

- Liobikienė, G., and R. Juknys. 2016. The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. Journal of Cleaner Production 112:3413–3422. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.049.

- Lu, L. C., H. H. Chang, and S. T. Yu. 2013. Online shoppers’ perceptions of e-retailers’ ethics, cultural orientation, and loyalty: An exploratory study in Taiwan. Internet Research 23 (1):47–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/10662241311295773.

- Luchs, M. G., M. Phipps, and T. Hill. 2015. Exploring consumer responsibility for sustainable consumption. Journal of Marketing Management 31 (13–14):1449–1471. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1061584.

- Luomala, H., P. Puska, M. Lähdesmäki, M. Siltaoja, and S. Kurki. 2020. Get some respect–buy organic foods! When everyday consumer choices serve as prosocial status signaling. Appetite 145:104492. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104492.

- Markus, H. R., and S. Kitayama. 1991. Cultural variation in the self-concept. In The self: interdisciplinary approaches, eds. Jaine Strauss and George R. Goethals, 18–48. New York: Springer.

- McCarty, J. A., and L. J. Shrum. 2001. The influence of individualism, collectivism, and locus of control on environmental beliefs and behavior. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 20 (1):93–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.20.1.93.17291.

- Milfont, T. L., J. Duckitt, and L. D. Cameron. 2006. A cross-cultural study of environmental motive concerns and their implications for pro-environmental behavior. Environment and Behavior 38 (6):745–767. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505285933.

- Minbashrazgah, M. M., F. Maleki, and M. Torabi. 2017. Green chicken purchase behavior: The moderating role of price transparency. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 28 (6):902–916. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-12-2016-0093.

- Miniero, G., A. Codini, M. Bonera, E. Corvi, and G. Bertoli. 2014. Being green: From attitude to actual consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (5):521–528. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12128.

- Moisander, J. 2007. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. International Journal of Consumer Studies 31 (4):404–409. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00586.x.

- Morren, M., and A. Grinstein. 2016. Explaining environmental behaviour across borders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 47:91–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.05.003.

- Morwitz, V. G., J. H. Steckel, and A. Gupta. 2007. When do purchase intentions predict sales? International Journal of Forecasting 23 (3):347–364. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2007.05.015.

- Mostafa, M. M. 2007. Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: The effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. International Journal of Consumer Studies 31 (3):220–229. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2006.00523.x.

- Nair, S. R., and V. J. Little. 2016. Context, culture and green consumption: A new framework. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 28 (3):169–184. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2016.1165025.

- Ngo, A. T., G. E. West, and P. H. Calkins. 2009. Determinants of environmentally responsible behaviours for greenhouse gas reduction. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2):151–161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00763.x.

- Nidumolu, R., C. K. Prahalad, and M. R. Rangaswami. 2009. Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harvard Business Review 87 (9):56–64.

- Nielsen. 2013. Will a desire to protect the environment translate into action? https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2013/will-adesire-to-protect-the-environment-translate-into-action-.html

- Nyborg, K., R. B. Howarth, and K. A. Brekke. 2006. Green consumers and public policy: On socially contingent moral motivation. Resource and Energy Economics 28 (4):351–366. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2006.03.001.

- Oliver, J. D., and S. H. Lee. 2010. Hybrid car purchase intentions: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Consumer Marketing 27 (2):96–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011027204.

- Oyserman, D., H. M. Coon, and M. Kemmelmeier. 2002. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin 128 (1):3–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3.

- Paco, A., and R. Gouveia Rodrigues. 2016. Environmental activism and consumers’ perceived responsibility. International Journal of Consumer Studies 40 (4):466–474.

- Park, H., C. Russell, and J. Lee. 2007. National culture and environmental sustainability: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Economics and Finance 31 (1):104–121. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02751516.

- Parker, A. G., and R. E. Grinter. 2014. Collectivistic health promotion tools: Accounting for the relationship between culture, food and nutrition. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 72 (2):185–206. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.08.008.

- Paul, J., A. Modi, and J. Patel. 2016. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 29:123–134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.11.006.

- Puska, P., S. Kurki, M. Lähdesmäki, M. Siltaoja, and H. Luomala. 2018. Sweet taste of prosocial status signaling: When eating organic foods makes you happy and hopeful. Appetite 121:348–359. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.102.

- Rahman, S. U. 2019. Differences in horizontally individualist and vertically collectivist consumers' environmental behaviour: A regulatory focus perspective. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets 11 (1):73–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEM.2019.097479.

- Rahman, S., and H. Luoamala. 2020. A comparison of motivational patterns in sustainable food consumption between Pakistan and Finland: Duties or self-reliance? Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing :1–28.

- Rantanen, T., and T. Toikko. 2017. The relationship between individualism and entrepreneurial intention–a Finnish perspective. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 11 (2):289–306. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-10-2014-0021.

- Reisch, L. A., M. J. Cohen, J. B. Thøgersen, and A. Tukker. 2016. Frontiers in sustainable consumption research. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 25 (4):234–240.

- Roldán, J. L., and M. J. Sánchez-Franco. 2012. Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems, eds. M. Mora, O. Gelman, A. Steenkamp, and M. Raisinghani, 193–221. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Schultz, P. W. 2002. Environmental attitudes and behaviors across cultures. In Online readings in psychology and culture, eds. W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, and D. Sattler. Bellingham, 2307–2319. WA: Western Washington University, Department of Psychology, Center for Cross-Cultural Research.

- Schwartz, S. H. 1968. Words, deeds, and the perception of consequences and responsibility in action situations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 10 (3):232–242. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026569.

- Schwartz, S. H. 1977. Normative influences on altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 10 (1):221–279.

- Shavitt, S., and A. J. Barnes. 2019. Cross‐cultural consumer psychology. Consumer Psychology Review 2 (1):70–84.

- Shavitt, S., and H. Cho. 2016. Culture and consumer behavior: The role of horizontal and vertical cultural factors. Current Opinion in Psychology 8:149–154. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.11.007.

- Shavitt, S.,. T. P. Johnson, and J. Zhang. 2011. Horizontal and vertical cultural differences in the content of advertising appeals. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 23 (3–4):297–310.

- Shavitt, S.,. A. K. Lalwani, J. Zhang, and C. J. Torelli. 2006. The horizontal/vertical distinction in cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology 16 (4):325–342. doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1604_3.

- Singelis, T. M., H. C. Triandis, D. P. Bhawuk, and M. J. Gelfand. 1995. Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research 29 (3):240–275. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/106939719502900302.

- Soyez, K. 2012. How national cultural values affect pro-environmental consumer behavior. International Marketing Review 29 (6):623–646. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331211277973.

- Sreen, N., S. Purbey, and P. Sadarangani. 2018. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 41:177–189. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.12.002.

- Stern, P. C. 2000. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues 56 (3):407–424. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175.

- Stern, P. C., T. Dietz, T. Abel, G. A. Guagnano, and L. Kalof. 1999. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review :81–97.

- Stern, P. C., L. Kalof, T. Dietz, and G. A. Guagnano. 1995. Values, beliefs, and pro-environmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25 (18):1611–1636. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02636.x.

- Tam, K. P., and T. L. Milfont. 2020. Towards cross-cultural environmental Psychology: A state-of-the-art review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology 71:101474. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101474.

- Tang, Y., X. Wang, and P. Lu. 2014. Chinese consumer attitude and purchase intent towards green products. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 6 (2):84–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-05-2013-0037.

- Taufique, K. M. R., C. B. Siwar, B. A. Talib, and N. Chamhuri. 2014. Measuring consumers' environmental responsibility: A synthesis of constructs and measurement scale items. Current World Environment Journal 9 (1):27–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.12944/CWE.9.1.04.

- Thøgersen, J., Y. Zhou, and G. Huang. 2016. How stable is the value basis for organic food consumption in China? Journal of Cleaner Production 134:214–224. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.036.

- Triandis, H. C. 1995. Individualism & collectivism. New York: Routledge. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429499845.

- Triandis, H. C., and M. J. Gelfand. 1998. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 (1):118–128. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118.

- Tyupa, S. 2011. A theoretical framework for back-translation as a quality assessment tool. New Voices in Translation Studies 7 (1):35–46.

- United Nations. 2018. Sustainable development goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- van Zomeren, M. 2014. Synthesizing individualistic and collectivistic perspectives on environmental and collective action through a relational perspective. Theory & Psychology 24 (6):775–794. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354314548617.

- Wang, Y. 2014. Individualism/collectivism, charitable giving, and cause‐related marketing: A comparison of Chinese and Americans. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 19 (1):40–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1486.

- Waylen, K. A., A. Fischer, P. J. McGowan, and E. J. Milner-Gulland. 2012. Interactions between a collectivist culture and Buddhist teachings influence environmental concerns and behaviors in the Republic of Kalmykia. Society & Natural Resources 25 (11):1118–1133. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.663065.

- Wells, V. K., C. A. Ponting, and K. Peattie. 2011. Behaviour and climate change: Consumer perceptions of responsibility. Journal of Marketing Management 27 (7–8):808–833. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.500136.

- Wong, J., J. D. Newton, and F. J. Newton. 2014. Effects of power and individual-level cultural orientation on preferences for volunteer tourism. Tourism Management 42:132–140. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.004.

- Yi-Cheon Yim, M., P. L. Sauer, J. Williams, S. J. Lee, and I. Macrury. 2014. Drivers of attitudes toward luxury brands: A cross-national investigation into the roles of interpersonal influence and brand consciousness. International Marketing Review 31 (4):363–389. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-04-2011-0121.

- Zhang, J., and M. R. Nelson. 2016. The effects of vertical individualism on status consumer orientations and behaviours. Psychology & Marketing 33 (5):318–330.