Abstract

Music is considered as an effective tool in shaping consumers’ responses to advertising. The present study examines the effects of mildly incongruent background music upon consumers’ responses to restaurant advertising. It integrates country of origin and genre congruity of music in a single congruity framework through focusing more closely upon the twin components of congruity (expectancy and relevancy) and examines how various quadrants of musical in/congruity affect consumers’ cognitive responses and behavioral intentions. Between-subjects experiment was conducted to explore participants’ responses to an advertisement promoting a fictitious Italian restaurant. Findings indicate how the deliberate crafting of musical incongruity can be used to engage and amuse consumers, proposing that resolving mild musical incongruity may enhance consumers’ attitude toward advertising, perception of brand image and quality, as well as their purchase intent. The present research develops, refines, and redefines the concept of musical congruity in advertising and offers the first empirical evidence for the positive effects of using purposeful, mildly incongruent music upon consumers’ cognitive responses to advertising as well as their behavioral intentions.

Introduction

Music “serves a purpose in advertising through its significant influence on commercial messages and consumer responses” (Graakjaer Citation2014, p. 4). It is a ubiquitous phenomenon in the context of television and radio advertising (Marshall and Roberts Citation2008), with more than 94% of advertisements incorporating a certain type of music (Allan Citation2008). Music accounts for a significant commercial advantage in the context of advertising by producing favorable associations with the product/brand (Gorn Citation1982), contributing to the message (Hung Citation2000), and by attracting consumers’ attention and enhancing message recall (Yalch Citation1991). Advertisers utilize music to attract potential consumers’ attention and create a positive brand image (Oakes and Abolhasani Citation2020), as it is an influential element that can be emotionally appealing (Mogaji Citation2018). In terms of the effectiveness of using background music in the context of marketing, research shows that musical advertising campaigns are 27% more likely to report substantial business effects than nonmusical ones (Binet, Müllensiefen, and Edwards Citation2013).

Previous research highlights the effects of various objective characteristics of music such as key (e.g., Kellaris and Kent Citation1992; Citation1993), tempo (e.g., Kellaris and Kent Citation1993; Milliman Citation1986), complexity (North and Hargreaves Citation1998), frequency (Sunaga Citation2018) and volume (Kellaris and Rice Citation1993), as well as subjective characteristics of music such as liking (e.g., Dube, Chebat, and Morin Citation1995), familiarity (Bailey and Areni Citation2006), arousal (e.g., Dube, Chebat, and Morin Citation1995; Mattila and Wirtz Citation2001), and mood induction (Alpert and Alpert Citation1990). The existing empirical research (e.g., Abolhasani and Oakes Citation2017; Alpert, Alpert, and Maltz Citation2005; North et al. Citation2004; Oakes and North Citation2006) mainly addressed the influence of music/advertising congruity and how it enhances communications effectiveness, recall of advertising information, brand attitude, affective response, as well as purchase intent. Furthermore, researchers have examined the effects of music liking on purchase intention (Vermeulen and Beukeboom Citation2016). For example, Mittal (Citation2015) confirms the classical conditioning effects of advertising music and found that viewing a pair of earrings accompanied by a liked piece of music enhanced the liking for the item. Music may increase customers’ recall of advertising information and influence their purchase intents (Ali, Srinivas, and Bhat Citation2012; Oakes Citation2007).

To date, little research has focused on the effects of deliberate musical incongruity in advertising on communications effectiveness and reinforcing the advertising proposition (Abolhasani, Oakes, and Golrokhi Citation2020). The present research investigates the effects of mildly incongruent music on consumer responses to advertising. Advertising effectiveness depends on the extent to which consumers process the information that is being communicated in a message (Jurca and Madlberger Citation2015). Advertisers may be able to use the novelty, surprise, or unexpectedness of incongruent music in order to enhance consumers’ affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to advertising. Findings from existing studies using nonmusical stimuli underpin the benefits of using incongruity in advertising (e.g., Heckler and Childers Citation1992).

Studies drawing on incongruity, either in nontraditional advertising campaigns such as in-game advertising (Lewis and Porter Citation2010) or in the context of inconsistent brand communication (Halkias and Kokkinaki Citation2013) suggest that a moderate degree of incongruity positively influences advertising effectiveness. These studies reveal how using information that is incongruent with prior expectations may lead to more effortful and complicated processing, enhancing associative memory pathways. Using a mildly incongruent stimulus may be more effective in penetrating the perceptual screen of an audience to attract attention to the advertisement and enhance the identification of the primary theme and message of the advertisement.

Although congruent pieces of music may be well integrated with other elements of the advertisement, the artful use of mildly incongruent background music is also capable of establishing coherent integration with the advertising message. Further analysis of the incongruent musical stimuli used in previous studies (e.g., Kellaris and Mantel Citation1996; Shen and Chen Citation2006) shows that many of the musical stimuli used as examples of incongruity fall short of the artful deviation characteristic of such incongruity because they do not set out to elicit interpretations capable of reinforcing the advertising proposition (Oakes Citation2007). Purposeful and artful musical incongruity may locate musical stimuli within an interpretive zone which may enhance consumers’ responses to advertising. To this end, the present research aims to demonstrate the effects of artful musical incongruity (mild incongruity) on consumers’ cognitive, and behavioral responses to advertising.

Musical congruity in advertising

Musical congruity is a term that is comparable to equivalent authorial terms such as musical fit (e.g., Macinnis and Park Citation1991). It concerns the extent to which a piece of music used in an advertisement conforms to or detracts from the main message of the advertisement and the brand image. Macinnis and Park (Citation1991) point out that music that fits the advertisement (which they define as the listeners’ individual perception of its relevance and appropriateness to the central advertising message and brand), could also affect consumers in terms of their engagement with the advertisement. Kellaris and Kent (Citation1993) suggest that high congruity between music and advertising message may enhance brand name and message recall as opposed to low congruity. Moreover, Oakes (Citation2007) argues that musical congruity may contribute to communications effectiveness through enhancing purchase intent, recall facilitation, and affective response. Research also demonstrates how a higher level of congruity between music and the main message of the advertisement results in greater memorization of the advertising information and induces positive feelings (Lord, Lee, and Sauer Citation1995). Furthermore, Lavack, Thakor, and Bottausci (Citation2008) demonstrate how congruent music results in more positive attitudes to the advertisement and brand compared to incongruent music or no music, but only for advertisements demanding allocation of high cognitive resources.

Although much is known about the effects of congruent information on memory and recall, there is a need to particularly explore the effects of incongruent background music on consumers’ perceptions, attitude formation and evaluations, and to investigate whether a tradeoff exists between the inclusion of various pieces of in/congruent background music and consumers’ behavioral responses to advertising. Incongruous information appears to develop a more complicated set of cognitive connections as consumers attempt to resolve the purpose of incongruous stimuli that they are exposed to. Unlike incongruous information, congruous information is easier to understand and integrate with our prior expectations, and therefore, the absence of incongruous information may result in little need to access memories and prior associations in the search for advertising meaning. This may have clear implications in developing the concept of congruity in the context of advertising.

Conceptual framework and development of hypotheses

Twin component congruity framework

Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) propose a general framework for congruity that postulates two components; expectancy and relevancy. Expectancy refers to “the degree to which an item or piece of information falls into some predetermined pattern evoked by the theme,” while relevancy is defined as “material pertaining directly to the meaning of the theme and reflects how information contained in the stimulus contributes to or detracts from the clear identification of the theme” (Heckler and Childers Citation1992, p. 477). They explore the effects of manipulating in/congruity through the picture component of print advertisements. Their study reveals that advertisements containing unexpected/relevant information produce the more pronounced effort to understand the advertisements compared to expected/relevant information which is relatively easier to comprehend.

A key objective of the current research is to integrate country of origin musical congruity and genre congruity in a single congruity framework through focusing more closely upon the twin components of congruity (expectancy and relevancy). Consequently, the current research seeks to develop, refine, and redefine the concept of congruity by exploring and expanding the application of Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) congruity framework in an advertising music context.

Musical genre and country of origin congruity

Different musical genres may be capable of reinforcing specific advertising messages in various advertising contexts, and each musical genre may have a discrete form of relevance (e.g., utilitarian or hedonic) for the advertising message (Oakes and North Citation2013). Classical music used in advertising may be associated with an image of upmarket sophistication, while rock or dance music may be associated with a hedonic image. For example, Hung (Citation2001) reports how congruently upmarket classical music reinforces the favorable, upmarket brand image of an advertised shopping mall.

On the other hand, certain styles of music can be associated with specific nations, so that music can be identified as “Chinese,” “Italian,” “French,” etc. even by listeners with otherwise limited knowledge of the corresponding culture (Folkestad Citation2002). In other words, each country has its own distinct musical traditions. Although the development of popular music in the UK and USA has had a large influence on the musical culture of other countries, national stereotypes and preferences are still defining some countries’ musical output (iMusician Citation2014). Furthermore, national music styles may evoke concepts and images congruent with cultural stereotypes of that country. For example, while German music might make consumers think of beer and bratwurst, French music might evoke images of wine and the Eiffel Tower.

Although previous studies investigated various types of congruity, controlled studies examining the effects of symbolic meanings represented by musical stimuli in advertisements are few (Hung Citation2000), and hence, there is limited understanding regarding how musical congruity and incongruity affect consumers’ responses to advertisements. Most importantly, investigating the existing studies related to the effects of the twin component congruity theory developed by Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) suggests that there is little critical assessment of the distinction between expectancy and relevancy.

Defining-attribute theories acknowledge that things form themselves into categories because they have certain attributes in common. In other words, a certain concept is characterized by a list of features that are necessary to determine if an object is a member of the category. In identifying expectancy and relevancy as defining-attributes of congruity, such theories suggest that both attributes would be necessary for a stimulus to be categorized as congruent. However, differentiation between the two components in the context of music and advertising is somewhat ambiguous.

Based on Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) twin component congruity framework, there is only one quadrant that can be considered as the congruent condition (expected/relevant). The remaining three quadrants (unexpected/relevant, expected/irrelevant, and unexpected/irrelevant) are regarded as incongruent because they contain an unexpected element, an irrelevant element, or both. It is to be noted that the nature of in/congruity of an advertising component (music in this context) may be determined by its relationship with the advertising message. Depending on the existence or lack of existence of expectancy and/or relevancy, the current study, therefore, proposes that the in/congruent quadrants may be segregated as the quadrants below. The present study then offers the rationale for this categorization.

Congruent (expected/relevant)

Mildly incongruent (unexpected/relevant)

Incongruent (expected/irrelevant)

Severely incongruent (unexpected/irrelevant)

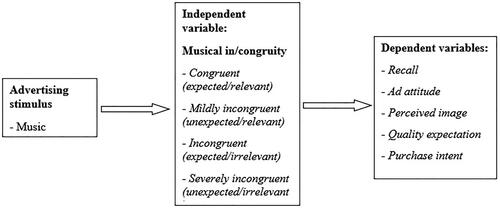

The present research builds on Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) twin-component congruity theory to develop a conceptual framework that examines the effects of various musical in/congruity conditions on a range of dependent variables, including information recall, attitude toward the advertisement, perceived image of the advertised product, expectation of food and service quality, as well as purchase intent (see ).

We test our framework in an experiment that examines the role of music in restaurant advertising.

Mild musical incongruity and recall

In a recent study in the context of background music in restaurants, North, Sheridan, and Areni (Citation2016) suggests that the number of recalled dishes from each country was higher when the music playing was associated with the same country. Advertising music helps consumers to identify a particular brand (Ballouli and Heere Citation2015), as the association of music with the brand may positively aid affect brand recall. Existing studies examine the effects of background music on recall (e.g., Fraser and Bradford Citation2013; Guido et al. Citation2016; Kellaris and Kent Citation1993; North et al. Citation2004; North, Sheridan, and Areni Citation2016; Oakes and North Citation2006; Olsen Citation1995; Roehm Citation2001; Stewart and Punj Citation1998). Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) study the effects of congruity between picture and advertising message for multiple products such as shoes and calculators and found that advertisements with unexpected information produced better recall than advertisements with expected information. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no research has explored the effects of various musical in/congruity conditions on recall of advertising information. Mandler (Citation1982) suggests that when pieces of information are inconsistent, the situation is considered novel and draws attention. Therefore, consumers are likely to pay increased attention to the information and consequently exhibit higher recall and recognition of the information, when faced with situations in which incongruent information must be processed. Unexpected information presents a diversion from the norm and attracts viewers’ attention more than expected information (Haberland and Dacin Citation1992). On the other hand, advertisements with irrelevant information may result in inferior recall compared to advertisements with relevant information. Therefore, it is proposed that:

H1: Unexpected/relevant music in advertising will enhance consumers’ recall of information.

Consumers’ attitudes toward the advertisement represent individuals’ internal evaluations of the overall advertising stimulus. Resource matching notions (Meyers-Levy and Peracchio Citation1995) seem to provide a valuable perspective regarding the complex relationship between music-message congruity, cognitive processing, and attitudes. This framework suggests that music incongruent with an advertising message may consume cognitive resources, thus inhibiting processing which may lead to adversely affecting consumer attitudes toward the advertisement. However, regarding mild incongruity when using an unexpected but relevant piece of music, the underlying meaning of purposeful musical incongruity may be resolved through allocation of the cognitive resources, thus enhancing attitude through a pleasurable resolution of the detected musical incongruity in the advertisement.

Craton and Lantos (Citation2011) reveal that positive attitude toward the background music used in advertisements may result in enhancing attitude toward the advertisement itself. Extant research argues that predictable music is rated as more liked (Craton et al. Citation2016), and more positive (Egermann et al. Citation2013). However, Lee and Mason (Citation1999) investigated incongruity between textual and pictorial information for computer advertisements and found that advertisements with unexpected/relevant information evoked more favorable attitudes than advertisements with expected/relevant information. Also, advertisements with unexpected/irrelevant information elicited less favorable attitudes than advertisements with expected/irrelevant information. Research suggests that consumers react more favorably to moderate incongruity than either extreme congruity or extreme incongruity as it provides more novelty, unexpectedness, and distinctiveness that consumers value (Venkatesan Citation1973). This is consistent with numerous other researchers who hypothesized an inverted-U shape relationship between congruity and attitudes, with more positive attitudes associated with moderate levels of incongruity (Heckler and Childers Citation1992; Lane Citation2000; Jagre, Watson, and Watson Citation2001). It can therefore be proposed that unexpected/relevant background music may elicit a positive hedonic response in consumers that could positively affect their attitude toward the advertisement:

H2: Unexpected/relevant music in advertising will produce the most favorable attitudes towards the advertisement.

Advertisers use music to attract potential consumers’ attention and create a positive brand image (Oakes and Abolhasani Citation2020). Various pieces of music may portray different meanings and images. For example, classical music is considered to be sophisticated, upscale, prestigious, and high quality, whereas dance music may be considered to be hedonic, exciting and trendy (North and Hargreaves Citation1998). Various genres of music associate different genre-related qualities or attributes to the brand image. For example, attributes of various pieces of music used in a restaurant advertisement may be transferred to the restaurant brand, forming a distinctive image for the advertised restaurant.

Mandler (Citation1982) points out that schema incongruity is an interruption of expectations and predictions. The theory suggests that mild incongruity evokes a moderate level of arousal, while severe incongruity produces an extreme degree of arousal. Mandler suggests that individuals enjoy resolving the incongruity (e.g., in an advertisement), and that the process of establishing the underlying purpose of such incongruity may lead to positive evaluation. However, in the case of extreme incongruity, consumers may become frustrated if they are unable to resolve the purpose of incongruity.

It is proposed that musical expectancy influences attention, depth of processing, and image (Craton, Lantos, and Leventhal Citation2017). If the background music in an advertisement violates consumers’ expectations to a moderate degree, it may prompt attention and foster greater depth of information processing. In contrast, if music entirely fails to violate musical expectations, it may lose listeners’ attention and stimulate shallow processing. However, extreme violation of musical expectations may demand a high level of attention that could make the music the center of attention, and compete for cognitive resources that would otherwise be used for processing the advertising information. Therefore, there is a need for a more in-depth examination of the effects of the twin component congruity framework in the context of advertising music in investigating how country of origin musical congruity and genre congruity as two distinct dimensions of musical congruity can be used to determine various expectancy and relevancy levels (highlighting in/congruity quadrants) that could affect cognitive responses such as perceived brand image. Mild incongruity positively affects individuals’ overall feelings and perceptions of the experience (Jurca and Madlberger Citation2015). Therefore, the mildly incongruent advertising treatment (unexpected/relevant) may enhance brand image as a result of the successful incongruity resolution that takes place in the minds of consumers. Thus, it is proposed that:

H3: Unexpected/relevant music in advertising will enhance consumers’ perceived image of the advertised restaurant.

Customers evaluate their restaurant experience in a holistic manner. Service quality is regarded as one of the focal features in consumers’ perception of restaurants, and a short path to enhance customer satisfaction. Perceived service, as the judgment of an organization’s overall excellence or superiority in quality of food and service, is of great importance because of the intangible, inseparable, and multifaceted nature of the service. Managing service quality requires a restaurant to meet the expectations of customers and to do so consistently across service encounters. Similarly, food quality is one of the most important and fundamental components when assessing overall customer experience and satisfaction in the restaurant industry (Namkung and Jang Citation2007), that can influence customers’ evaluation of the brand (Selnes Citation1993).

Previous research reveals how using congruent music in retail stores may enhance consumers’ evaluation of the environment and the brand quality (Eroglu, Machleit, and Chebat Citation2005; Meyers-Levy, Louie, and Curren Citation1994). Conversely, selecting wrong pieces of music may result to negative consumer attitude (e.g., the perception of lower service quality) which may affect their time and money spent inside the retail (Jain and Bagdare Citation2011). The existing literature has investigated the influence of background music on a range of restaurant patrons’ behavior such as flavor pleasantness and overall impression of food (Fiegel et al. Citation2014) and consumer spending (North, Shilcock, and Hargreaves Citation2003), but the researchers are unaware of any previous studies investigating the effects of background music in advertisements on expectations of food and service quality. A recent study by Ziv (Citation2018) explored the effects of background music on consumers’ experience of taste and found that cookies tasted with pleasant background music were evaluated better that those tasted with unpleasant music. Restaurant atmospherics (such as music and light) are believed to influence customers’ emotions and expectations about the quality of food and service (Reimer and Kuehn Citation2005). However, this was in the context where consumers actually tasted the product or experienced the service environment, and not in an advertising context. While the Mehrabian–Russel model (Mehrabian and Russell Citation1974) proposes that individuals respond emotionally to environmental stimuli such as background music, affecting their evaluations of products, background music in advertisements may also affect consumers’ perception of product quality in advertisements prior to consumption. Consumers may have more difficulty resolving the disparate information when the incongruity increases. This may result in negative evaluations of the advertised product quality (Moore, Stammerjohan, and Coulter Citation2005). However, the extant research has not investigated the effects of using artfully incongruent music (mild incongruity) in great depth. When the hidden unexpectedness containing conceptual dissonance transmitted by the advertisement and the playful violation of expectations of the musical type used in advertisement is resolved by consumers, it may ultimately result in enhancing their attitude toward the advertisement and the brand. Consequently, enhancing consumers’ attitude through successful resolution of mild incongruity may enhance evaluation of the brand and expectation of food and service quality for the advertised restaurant: Thus, it is proposed that:

H4: Unexpected/relevant music will enhance consumers’ expectation of food and service quality.

Research on atmospheric cues in retail stores investigated the effects of the congruity of the country of origin of music and the product upon consumers’ product choice (e.g., North, Hargreaves, and McKendrick Citation1999). More recently, North, Sheridan, and Areni (Citation2016) indicate that individuals in a restaurant were more likely to select menu items associated with a given country when the music playing was from the same country. This indicates how music can subconsciously prime relevant knowledge and the choice of certain products if they match that knowledge. It demonstrates that music has the capability to activate knowledge structures associated with a specific country which may result in the selection of products that are congruent with those knowledge structures. While retailers play a variety of musical styles including international, national, and regional music to persuade consumers, advertisers use preexisting, altered, or original music in advertising to influence consumers’ buying behavior (Raja, Anand, and Kumar Citation2020).

The lack of relevance of music to the advertising subject matter may have detrimental effects on consumers’ buying decisions as musical irrelevancy may not be successfully resolved through allocating more cognitive resources, thus leading to negative attitudes toward the advertisement and the brand that result in lower purchase intent. However, elaborative decoding of an apparently incongruous stimulus may positively influence consumers’ purchase intent. Therefore, the current research will explore how using unexpected but relevant music may enhance consumers’ purchase behavior.

Research has revealed that using classical music in a wine store encouraged the purchase of more expensive wines, in contrast to playing top-forty music (Areni and Kim Citation1993). This suggests that classical music may be congruously associated with prestige, class, and elegance, all of which qualities can be linked to consumption of expensive wines, and therefore, this particular type of music encourages purchasing expensive wines. However, although research (e.g., Abolhasani, Oakes, and Oakes Citation2017) demonstrates how selecting a congruously perceived genre of music enhances consumers’ purchase intent, the mild incongruity as a result of selecting an unexpected/relevant musical genre may be resolved by the consumers in an equally successful manner. This fruitful incongruity resolution may be a reinforcing element in enhancing purchase intent. It can therefore be proposed that:

H5: Unexpected/relevant music will enhance consumers’ purchase intent.

Conceptualizing the incongruity quadrants

Much research on unexpectedness in marketing and advertising has focused on examining the positive effects of unexpected elements in advertising for attitude formation (Heckler and Childers Citation1992; Houston, Childers, and Heckler Citation1987; Lee and Mason Citation1999). Based on this stream of research, using unexpected information in advertisements may cause increased elaboration which may generally lead to enhanced positive attitude. On the other hand, a stream of research in neuroscience has revealed that unexpectedness enhances reward salience (e.g., Bromberg-Martin, Matsumoto, and Hikosaka Citation2010; Di Chiara Citation2002; Horvitz Citation2000).

Typically, individuals may be aroused when presented with a novel object (Berlyne Citation1960). Indeed, expectancy is critical to novelty as unexpected information is delivered and received in a unique or unusual mode (Lee and Mason Citation1999). The lack of expectancy is related to the degree of novelty, and unexpected information is naturally conveyed in a distinctive and surprising manner. This is a type of incongruity that may be desired as it results in reducing the arousal produced by the lack of expectancy through exploring the source of novelty. The assumption underlying the positive impacts of unexpected information in advertisements is that consumers must be able to successfully understand the advertising message (Lee and Mason Citation1999). In other words, for unexpected information to generate a favorable attitude, the advertisement must be able to present a relevant and appropriate context to consumers. If the advertisement context does not match the advertised brand’s message, consumers are more likely to perceive the advertising messages as attempts to persuade them (Raney et al. Citation2003), which may result in consumers being skeptical of the ads.

Mild incongruity condition: Unexpected/relevant

Unexpected information may trigger consumers’ cognitive resources to resolve the incongruity, whereas information that is irrelevant may lead to frustration and may not have the same effects as unexpected information. Musical incongruity can only be considered as “mild” when the informational cues (here music) are relevant to the central ad message, as this relevancy is crucial in bringing about positive evaluations toward the ad and the brand. Therefore, it may be proposed that the lack of expectancy only works when there is relevant information in place, and thus, a slight novelty in presenting the information could result in reducing arousal through exploring the source of novelty. Relevant components contain information useful to support the main message of the ad, while irrelevant ones do not help to identify the main message of the advertisement (Lee and Mason Citation1999).

A comprehensive review of the literature using nonmusical stimuli by Muehling and McCann (Citation1993) revealed that ad attitudes are higher when the advertisement contains relevant information. The presence of unexpected information, provided that they are relevant in nature, may then form a sort of incongruity that is desirable and can be decoded successfully, and hence, this quadrant (unexpected/relevant) may be referred to as the mildly incongruent quadrant. The cognitive elaboration may be rewarding in the form of tension reduction (Berlyne Citation1971), and this is what makes the unexpected/relevant quadrant mildly incongruent. Mild incongruity between an ad component and central message tends to trigger the interest of information receivers, and thus, has a better communication effect.

Severe incongruity condition: Unexpected/irrelevant

On the other hand, the obstacle to successful decoding arises when the unexpected information is also irrelevant in nature (Lee and Mason Citation1999). The lack of expectancy in the presence of irrelevant information not only diminishes consumer response, but it may also result in more confusion that cannot be resolved, because unexpected/irrelevant information may not be capable of establishing a connection with the advertising message and leads to frustration rather than resolution. The lack of relevancy of information may result in the creation of a type of incongruity that is not desired in terms of influencing the effectiveness of the ad. For example, Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) found that irrelevant information yielded inferior recall compared to relevant information.

As Lee and Mason (Citation1999) found, the presence of irrelevant information may lead to less favorable advertising evaluation, less favorable thoughts about the advertisement, less favorable brand evaluation, and less favorable thoughts about the brand. The rational conclusion may then be that the presence of irrelevancy will bring about incongruity. The current study proposes that the lack of expectancy may be fruitful in the presence of relevancy only (when there are informational cues that support the central ad message), and the novelty (unexpectedness) used in conveying irrelevant information may not result in a positive response. Therefore, it can be proposed that consumers perceive unexpected/irrelevant information in an advertisement to be severely incongruent.

Incongruent condition: Expected/irrelevant

The unexpected/irrelevant information quadrant represents the greatest incongruity, and therefore, it is expected that the unexpected/irrelevant information produces the most negative responses toward the ad and the brand, in comparison with expected/irrelevant information. The cognitive elaboration of unexpected/irrelevant information is expected to be more extensive compared to the expected/irrelevant information (Lee and Mason Citation1999). Thus, the expected/irrelevant information is likely to elicit less unfavorable thoughts than unexpected/irrelevant information. The current research, therefore, proposes that the expected/irrelevant condition may signify the incongruent quadrant.

Congruent condition: Expected/relevant

Based on the discussions above, and in line with the use of various components in the advertisements and their expectancy and relevancy levels, the current research proposes that the expected/relevant can be considered as the congruent quadrant. In this condition, the information is both expected in the context of a particular advertisement, and relevant and supportive of the main message of that advertisement.

Developing, refining and redefining the in/congruity quadrants

As far as the few existing studies on musical congruity in advertisements are concerned, the criteria based on which the effects of the twin components have been explored are somewhat unclear and the boundaries between the application of the two concepts and their link with particular responses from consumers are blurred. This may be due to the existing ambiguity in theorization when applying and refining Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) congruity model in the context of music and advertising. For example, in the study by Kellaris and Mantel (Citation1996), two examples of Chinese and two examples of western classical music were selected by an expert to represent congruent and incongruent music used for advertising Chinese and British-American restaurants. In their study, high stimulus congruity was operationalized by pairing the Chinese music with the advertising copy for the Chinese restaurant, while low stimulus congruity was operationalized by mismatching Chinese music with the British-American restaurant. However, oversimplification in measuring the expectancy and relevancy dimensions of congruity may have resulted in an unclear categorization of different quadrants that do not entirely correspond to the different logical and possible conditions of musical in/congruity.

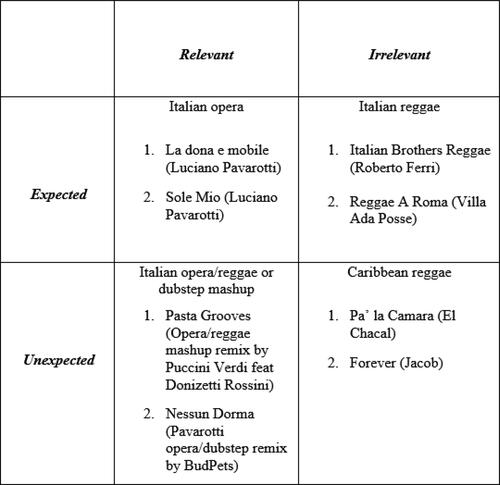

The present study offers alternative definitions for the congruity components to suit the music and advertising context. Expectancy may be referred to as the degree to which a piece of music conforms to the predetermined pattern or structure evoked by the advertising message, while relevancy may be defined as the extent to which a piece of music contributes to or detracts from the identification and recognition of the advertising message. Consequently, in the context of the present study, expectancy will be linked to the country of origin of the music and the extent to which it matches the predetermined or expected pattern elicited by the advertising message, while relevancy is linked to the genre of music and its relevance for reinforcing the advertising message and brand image.

Based on the revised definitions of expectancy and relevancy, the present study investigates the effects of these congruity components through careful categorization of background music pieces into various congruity quadrants in the context of advertising for an authentic Italian restaurant. Therefore, the expectancy deals with the extent to which various pieces of music from different countries of origin fall within the predetermined pattern in terms of being expected to be heard in an advertisement for an Italian restaurant, while the relevancy component of music refers to the extent to which the genre of music reinforces the message to be communicated by an advertisement for an authentic Italian restaurant. The effects of these in/congruity quadrants on consumers’ cognitive and behavioral responses to the advertisement will be examined in the present study.

Materials and methods

Clients and advertising agencies spend a considerable amount of money to use music as one of the crucial features in radio advertising. For example, Páez and Veloso (Citation2008) pointed out that more than 80% of radio advertisements in Spain contain music as an important background feature. Using background music in radio advertisements could result in a significant commercial advantage to advertisers by adding value and improving advertising effectiveness. The high levels of source credibility and penetration rate, as well as the ability to generate mental images in audiences have made radio advertising an important medium for advertisers to influence consumers’ affective and cognitive responses which may in turn result in a greater level of persuasion. Furthermore, radio as a relatively cheaper (compared to television) medium for transferring persuasive advertising messages, provides the opportunity for advertisers to target specific customers with a distinct set of preferences.

Investigating consumers’ responses to radio advertising is particularly important because there is no interference from visual elements associated with television advertising. Research has indicated that music and other types of sound in radio advertising enhance imagery activity in audiences (Miller and Marks Citation1992). It shows that when increased imagery activity is accompanied by the elicitation of positive feelings, it will enhance listeners’ attitude toward the advertment. Furthermore, it indicated that sound may have profound effects on consumers’ affective and cognitive response to radio advertisements as it directly activates memory structures that contain perceptual information. The current research seeks to examine the impact of musical in/congruity in conditions where there is a lack of visual imagery and to assess how musical in/congruity works in the context of radio advertising. Four musical treatments of a radio advertisement promoting a fictitious authentic Italian restaurant were created to manipulate the independent variables which are country of origin of music and genre of music. Advertising-generated mental imagery may reconcile the ad-evoked feelings and attitudes elicited by advertising (Bone et al. Citation1991). In this context, radio advertising is of particular importance as it is a medium that is well-suited and highly relevant for imagery-evoking strategies, music, vivid verbal messages, and specific instructions to listeners to imagine (Russell and Lane Citation1990).

Based on the concept of resource matching, using incongruent information in advertisements may lead to consuming more cognitive resources that may in turn result in inhibiting processing of the ad, thus negatively affecting consumers’ attitudes and recall. This process is more expected when the advertisement demands a high level of cognitive processing effort, as “cognitive resources are likely to be fully extended in such a case, and may be unable to cope with the extra burden imposed by music-message incongruity” (Lavack, Thakor, and Bottausci Citation2008, p. 556). Babin, Burns, and Biswas (Citation1992) argue that the type of advertised product may influence audiences’ imagery processing as well as involvement. For example, products that are considered as strictly utilitarian may hinder consumers’ visualization process and the extent to which they rely on their perceptions of product features and qualities. Consequently, a restaurant is chosen as the context of the current study since it offers the type of product that is relatively low-involvement and completely hedonic in nature. Radio advertisements for restaurants are capable of evoking mental imagery in consumers, allowing them to visualize restaurants’ atmosphere through a quasi-perceptual experience generated by various features of the advertisement such as background music. Therefore, restaurant advertising is used to investigate the effects of musical in/congruity in the context of radio advertising where there is a lack of visual imagery.

Advertising stimulus

An advertisement copy was recorded to promote a fictitious authentic Italian restaurant called “Pasta Masters Restaurant.” The advertisement communicated an authentic Italian experience as follows:

For pasta dishes, pizzas, and the very best in Italian cuisine, a warm welcome is waiting for you at Pasta Masters Restaurant. Soak up the atmosphere of an authentic Italian restaurant and choose from our extensive menu that is freshly prepared for your delight. We offer ample and convenient parking and service that is second to none. Large parties are always welcome, but please book early to avoid disappointment. For further details or to make a reservation, contact us on 0800-080-808 between 11:00 am and 10:00 pm from Monday to Saturday. Pasta Masters Restaurant - menus to please every palate.

The advertising voiceover was narrated by a postgraduate drama student and lasted 53 seconds. The advertisement for the restaurant was recorded in a university Drama department recording studio, using professional recording facilities. Brief excerpts of vocal pieces of music were used in advertisement copies to be prepared for the manipulation checks. They were tested to establish an appropriate volume level to facilitate a comfortable listening experience, as well as ensuring that the background music used in various treatments did not impede the narratives. As the study used an advertisement for a fictitious Italian restaurant, the participants did not have any pre-established perception of the quality and image of the restaurant.

Manipulation check

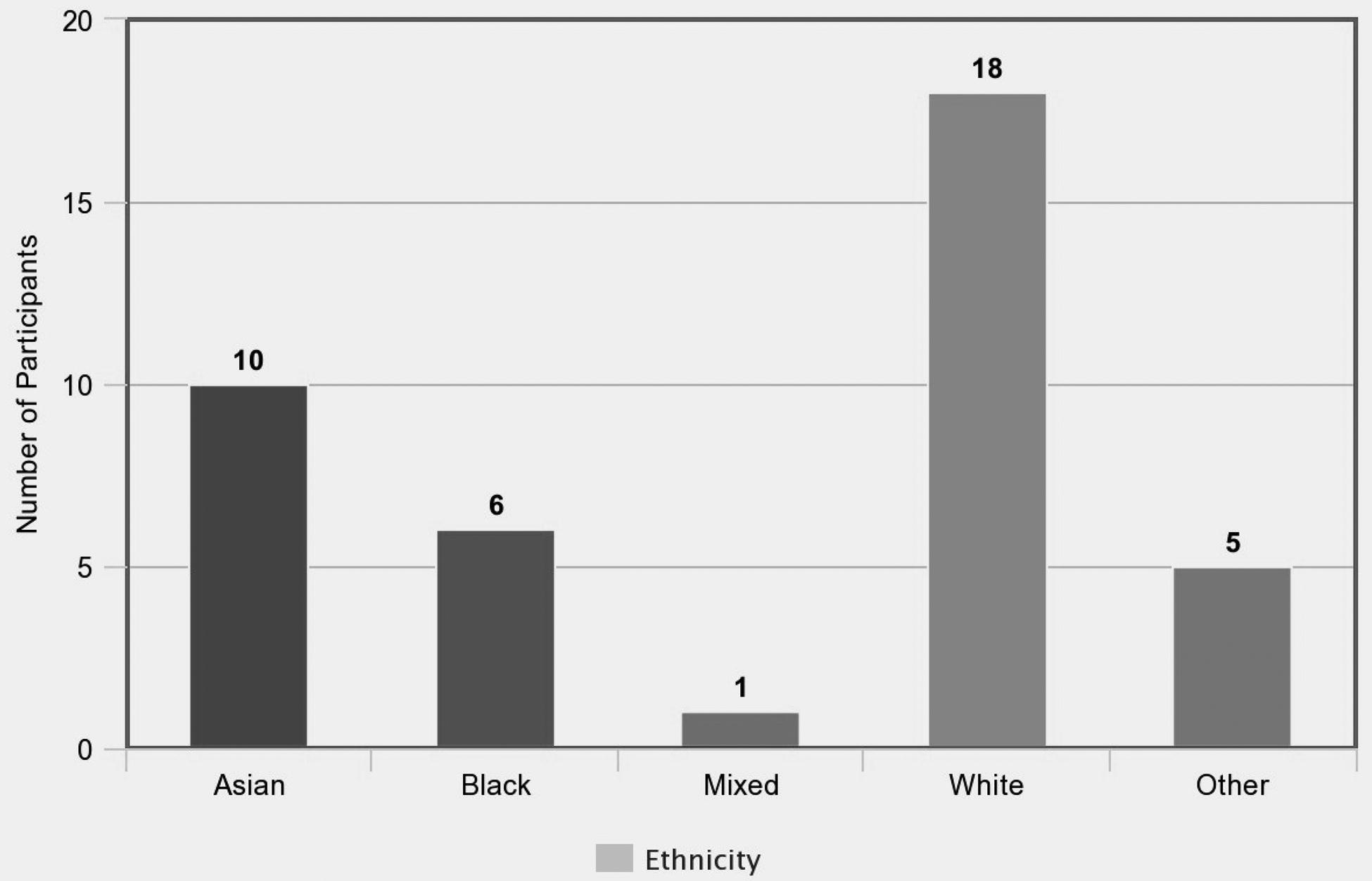

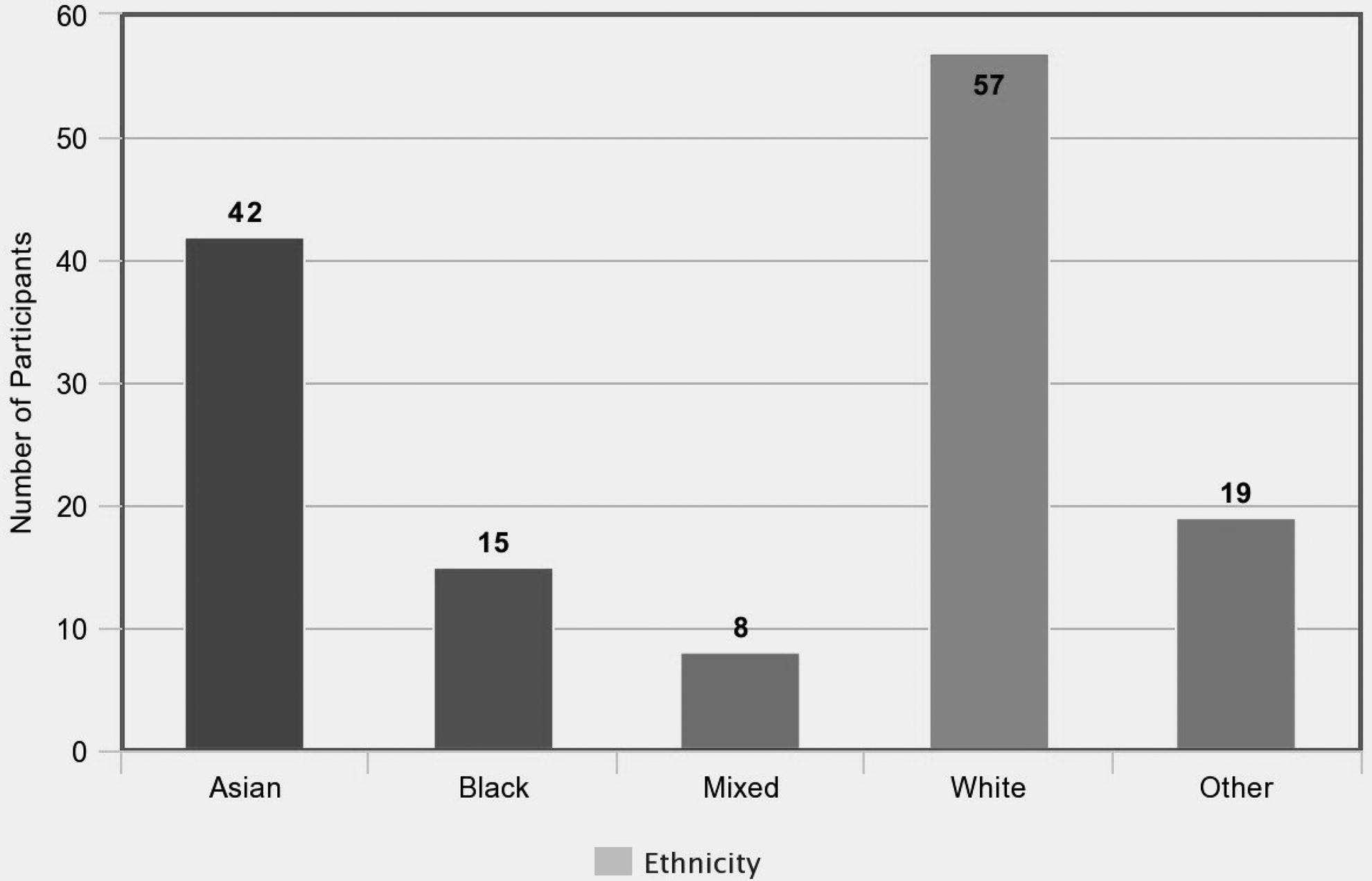

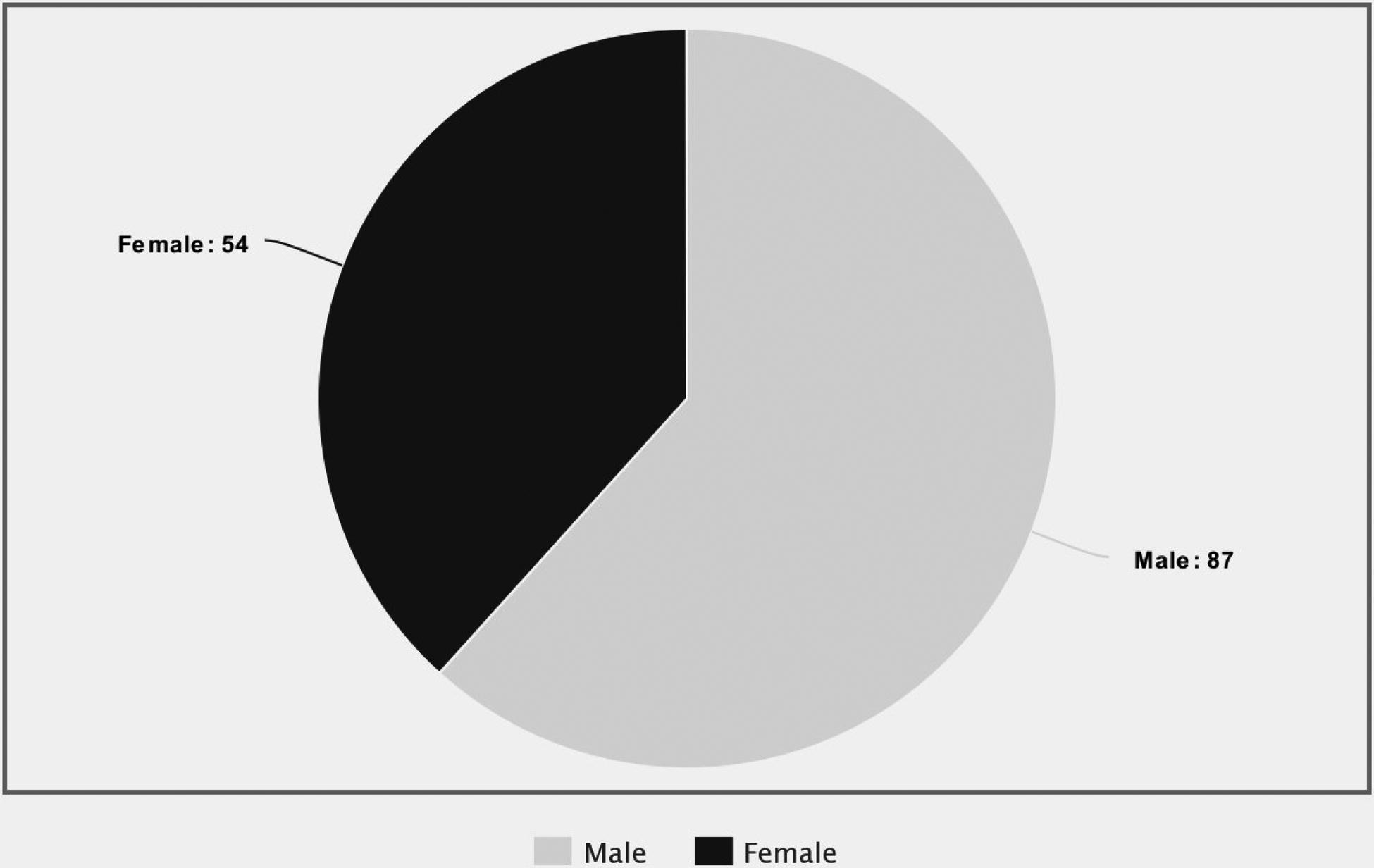

Stimulus congruity was manipulated in a pretest involving eight treatments through within-subjects design in which 40 participants (58% male and 42% female, average age of 18.9 years) were exposed to every treatment (Please see appendix A for the sample’s demographic information for the Manipulation Check). demonstrates various musical treatments selected to be used to constitute different congruity quadrants. Within-subjects design was used at this stage as participants were asked to rate the expectancy and relevancy of each piece of music used in the radio advertisement (Please see appendix B for the questionnaire for the Manipulation Check). This would establish the efficacy of the musical manipulations representing the different treatment conditions of expectancy and relevancy. An objective of conducting the manipulation test was to inform choice of musical treatments for relevancy/expectancy quadrants. Manipulation checks also verified knowledge and recognition of the country of origin of various pieces of music used in different treatments, as well as testing identification of the musical genres in each treatment.

The results of the manipulation checks helped in identifying four of the most appropriate advertising conditions to be used in the main survey study, based on participants’ responses to the four questions involving 1) the extent to which the music identifies the country of origin of the restaurant 2) the extent to which participants were able to specify the country of origin of the music used in the advertisement 3) the extent to which participants were able to specify the genre of music used in the advertisement and 4) the extent to which the music suggests that the restaurant offers authentic Italian food. Based on this, the following four pieces of music were selected to represent four different musical in/congruity quadrants in the main survey study:

1) Expected/Irrelevant: Italian Reggae, Roberto Ferri “Italian Brothers Reggae”

2) Expected/Relevant: Italian Opera, Pavarotti “La Dona e Mobile”

3) Unexpected/Irrelevant: Caribbean Reggae, El Chacal “Pa’ la Camara”

4) Unexpected/Relevant: Opera Reggae Mashup, Puccini Verdi feat Donizetti Rossini “Pasta Grooves”

These four in/congruity quadrants represent various categories in which each selected piece of music may be placed with regards to its degree of relevancy to the advertised restaurant and expectancy to be positioned in this particular radio advertisement.

Main experiment

Design and participants

Having established the final four musical treatments, a between-subjects design was initiated through which each group of participants were exposed to only one advertisement treatment and were asked to answer a set of questions. The between-subjects design was used to avoid the carryover effects that can plague within-subject design and reduce the likelihood of participants becoming aware of the purpose of the study.

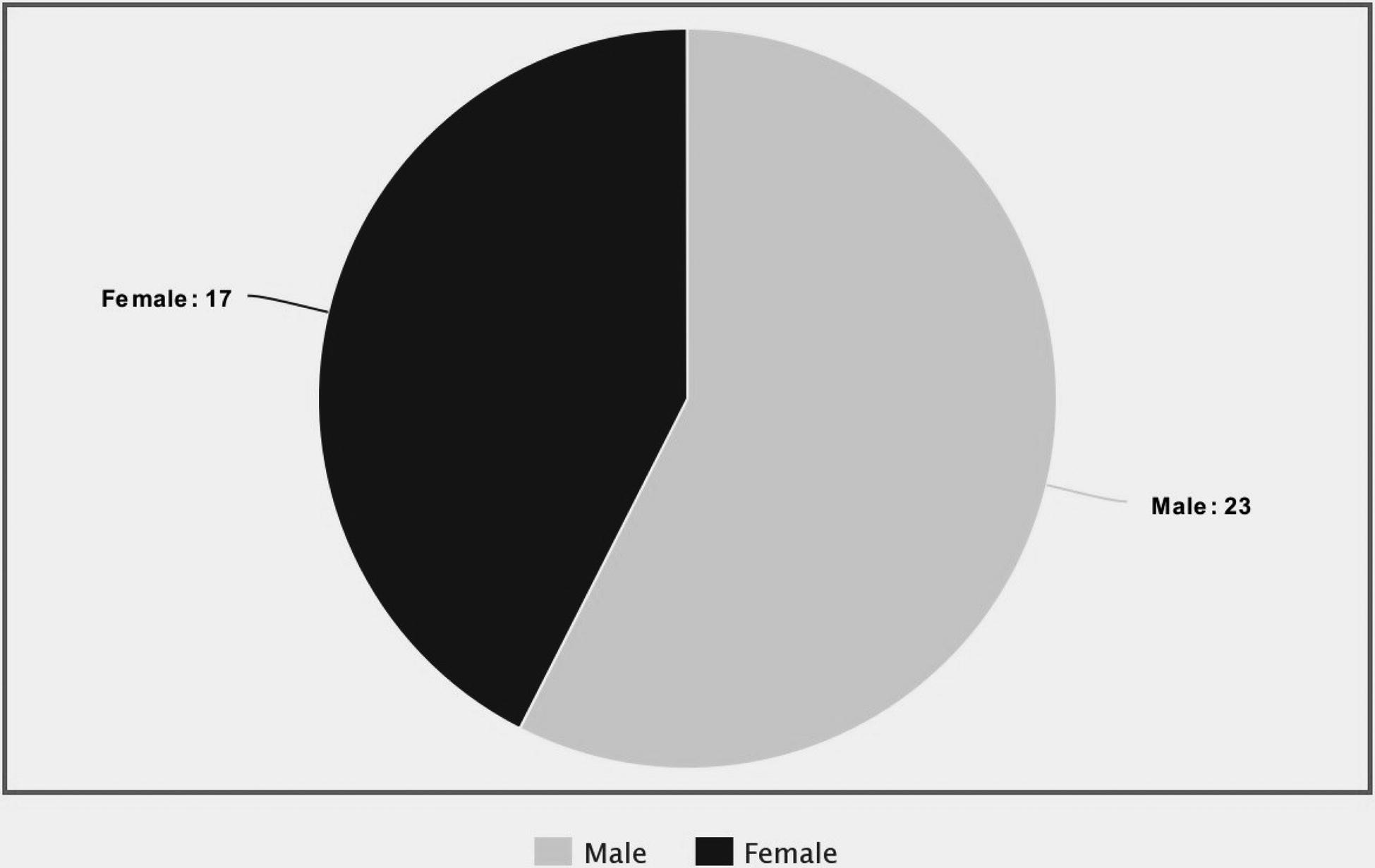

A total number of 141 first year undergraduate students participated in the survey experiment; 33 in the “Expected/Irrelevant,” 35 in the “Expected/Relevant,” 37 in the “Unexpected/Irrelevant,” and 36 in the “Unexpected/Relevant” treatments. The mean age of participants was 18.6 (M = 18.6), and the gender distribution was 62% male and 38% female (Please see appendix C for the sample’s demographic information for the Main Experiment). Millennials (born between 1980 and 2000), which also coincides with today’s university students, are becoming an increasingly important customer group for the restaurant industry (Powers et al. Citation2017). University students are social, open to experiment and adventure, and are highly receptive to advertising for food concepts, and therefore, constitute a valuable target market for restaurants, providing them with the opportunity to attract new customers and grow their business. Moreover, music plays an important part in the lives of students, as highlighted by Shevenock (Citation2020), 51% of adults ages 18–29 stream music every day, compared to 24% of all adults. Therefore, it is appropriate to recruit students as research participants for this study.

Participants were taken to a quiet room one by one, where they were informed that the goal of this study was to explore their evaluation of the effectiveness of the radio advertisement for a restaurant. They were asked to read information sheet and sign the consent form prior to taking part in the study. Participants were asked to listen to the radio advertisement which was played through the high-quality speakers in the room and fill out the questionnaire (Please see appendix D for the questionnaire for the Main Experiment). Although the present research project does not explore a sensitive topic and there was no potential for harm on the part of participants, the researchers have completely adhered to the accepted ethical standards of a research study by obtaining the Ethics’ Committee’s approval and ensuring voluntary participation, as well as the confidentiality of the data and anonymity of the participants.

Results

The findings presented in this section illustrate how purposeful use of unexpected/relevant music representing an artful musical incongruity may positively affect consumers’ responses to advertising through examining the impact on a range of dependent variables including recall of information, attitude toward the advertisement, perceived image of the brand, perceived quality, as well as purchase intent.

Mild musical incongruity and its effects on recall of advertising information

Hypothesis 1 of the present study tests whether unexpected/relevant music in advertising will enhance consumers’ recall of information. The recall of advertising information in various in/congruity quadrants was examined through three different measures.

The first measure to examine recall was the extent to which participants exposed to various treatments were able to recall the restaurant brand name. For this purpose, a frequency test was conducted which revealed that a higher percentage of participants listening to the unexpected/relevant treatment (91.7%) recalled the brand name correctly, while this figure was 85.7% for expected/relevant, 78.8% for expected/irrelevant, and 73% for unexpected/irrelevant treatments.

The second measure to examine recall of information was the extent to which participants were able to recall the advertising slogan. A frequency test showed that the unexpected/relevant treatment produced the highest level for recall of advertising slogan (86.1%), while this figure was 77.1% for expected/relevant, 75.8% for expected/irrelevant, and 75.7% for unexpected/irrelevant treatments.

Furthermore, an ANOVA test revealed a statistically significant difference between in/congruity treatments in recalling the advertising claims, thus supporting hypothesis 1:

Recall of advertising claims (F(3, 137) = 5.08; p < 0.01)

A Tukey test revealed that the unexpected/relevant (M = 3.92, SD = 0.97) treatment produced a significantly higher level of recall of advertising claims compared to expected/irrelevant (M = 3.21, SD = 1.05) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 3.14, SD = 1.00) treatments. There was no significant difference in recalling advertising claims between unexpected/relevant (M = 3.92, SD = 0.97) and expected/relevant (M = 3.66, SD = 0.91) or between any other combination of treatments.

Mild musical incongruity and its effects on consumers’ ad attitude

ANOVA test results revealed a statistically significant difference between treatments in terms of the influence of various in/congruity treatments on the attitude toward the advertisement, partially supporting hypothesis 2, revealing that unexpected/relevant music in advertising produces the most favorable attitudes toward the advertisement:

Enjoyable/Not enjoyable (F(3, 137) = 8.06; p < 0.001)

Not entertaining/Entertaining (F(3, 137) = 5.25; p < 0.01)

Tukey tests reveal that the expected/relevant (M = 2.40, SD = 0.91) treatment produced a significantly more enjoyable attitude toward the advertisement compared to the expected/irrelevant (M = 3.21, SD = 1.08) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 3.49, SD = 0.96) treatments. There was no significant difference in enjoyment of the advertisement between the expected/relevant (M = 2.40, SD = 0.91) and unexpected/relevant (M = 2.58, SD = 1.32) treatments or between any other combination of treatments.

Tests also indicated that participants exposed to the unexpected/relevant (M = 3.50, SD = 1.08) treatment thought that the advertisement was significantly more entertaining compared to those exposed to the expected/irrelevant (M = 2.76. SD = 0.87) or unexpected/irrelevant (M = 2.70, SD = 0.97) treatments. There was no significant difference in level of entertainment between unexpected/relevant (M = 3.50, SD = 1.08) and expected/relevant (M = 3.03, SD = 0.86) treatments or between any other combination of treatments. The results suggest that participants perceived the unexpected/relevant treatment as the most entertaining and enjoyable, although there was no significant difference between expected/relevant and unexpected/relevant treatments. Thus, it can be confirmed that hypothesis 2 is partially supported.

Mild musical incongruity and its impact on perceived image of the Brand

One-way ANOVA results demonstrated a statistically significant difference between in/congruity treatments in terms of the influence on the perceived restaurant image for all of the items, thus supporting hypothesis 3, revealing that unexpected/relevant music in advertising will enhance consumers’ perceived image of the restaurant:

Dull/Exciting (F(3, 137) = 26.79; p < 0.001)

Pleasant/Unpleasant (F(3, 137) = 31.35; p < 0.001)

Tense/Relaxing (F(3, 137) = 44.65; p < 0.001)

Uncool/Cool (F(3, 137) = 32.45; p < 0.001)

Appealing/Unappealing (F(3, 137) = 25.12; p < 0.001)

Tukey tests revealed that the unexpected/relevant (M = 3.86, SD = 1.13) treatment produced a significantly more exciting image compared to expected/relevant (M = 3.37, SD = 0.94), expected/irrelevant (M = 2.82, SD = 0.85), and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 1.89, SD = 0.99) treatments. There was no significant difference in excitement between any other combination of treatments. Tests showed that the unexpected/relevant (M = 2.00, SD = 0.99) treatment produced an image that was significantly more pleasant than expected/irrelevant (M = 3.39, SD = 0.90) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 4, SD = 1.00) treatments. There was no significant difference in pleasantness between unexpected/relevant (M = 2.00, SD = 0.99) and expected/relevant (M = 2.46, SD = 0.98) or between any other combination of treatments. A Tukey test revealed that expected/relevant (M = 4.20, SD = 0.90) and unexpected/relevant (M = 3.78, SD = 0.87) treatments produced a significantly more relaxing image compared to expected/irrelevant (M = 2.15, SD = 1.12) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 2.11, SD = 0.97) treatments. There was no significant difference in terms of producing a tense or relaxing image between any other combination of treatments. Further tests revealed that unexpected/relevant (M = 3.92, SD = 1.18) and expected/relevant (M = 3.40, SD = 0.95) treatments produced an image that was significantly cooler than expected/irrelevant (M = 2.15, SD = 1.06) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 1.86, SD = 0.92) treatments. There was no significant difference in terms of producing an uncool/cool image between any other combination of treatments. A Tukey test also showed that the unexpected/relevant (M = 2.00, SD = 1.10) treatment produced a significantly more appealing image compared to the unexpected/irrelevant (M = 3.92, SD = 0.95) treatment. There was no significant difference in appeal between expected/relevant (M = 2.63, SD = 0.88) and expected/irrelevant (M = 3.09, SD = 0.95) or between any other combination of treatments. Therefore, considering the above results, it can be confirmed that except for one of the measures (tense/relaxing) for which the expected/relevant and unexpected/relevant treatments treatment produced the most positive results, the unexpected/relevant treatment produced the most exclusively positive image perceptions.

Impact of mild incongruity on expectation of food and service quality

ANOVA tests revealed a statistically significant difference between in/congruity treatments in perception of food and service quality, partially supporting hypothesis 4, indicating that unexpected/relevant music will enhance consumers’ expectation of food quality:

Food quality (F(3, 137) = 12.77, p < 0.001)

Service quality (F(3, 137) = 5.95, p < 0.01)

Tukey tests demonstrated that the unexpected/relevant (M = 3.92, SD = 0.94) treatment produced a significantly higher expectation of food quality compared to expected/irrelevant (M = 2.76, SD = 1.00) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 2.62, SD = 1.11) treatments. There was no significant difference in expectation of food quality between unexpected/relevant (M = 3.92, SD = 0.94) and expected/relevant (M = 3.34, SD = 0.91) treatments or between any other combination of treatments.

However, a Tukey test revealed that the expected/relevant (M = 3.63, SD = 0.78) treatment produced a significantly higher perception of service quality compared to expected/irrelevant (M = 2.91, SD = 0.84) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 2.89, SD = 1.10) treatments. There was no significant difference in perception of service quality between expected/relevant (M = 3.63, SD = 0.78) and unexpected/relevant (M = 3.47, SD = 0.94) treatments or between any other combination of treatments. The results concerning the effects of various in/congruity treatments on consumers’ expectation of food quality revealed that the unexpected/relevant treatment produced the highest expectation of food quality. However, although the expected/relevant treatment produced the highest expectation of service quality, there was no significant difference between this treatment and the unexpected/relevant treatment.

The effects of mild musical incongruity on consumers’ purchase intent

An ANOVA test revealed a statistically significant difference between different in/congruity treatments in terms of consumers’ purchase intention, thus supporting hypothesis 5, revealing that unexpected/relevant music will enhance consumers’ purchase intent:

Purchase intention (F(3, 137) = 19.88), p < 0.01)

A Tukey test revealed that the unexpected/relevant (M = 3.39, SD = 0.96) treatment produced a significantly higher purchase intention amongst participants compared to expected/irrelevant (M = 2.70, SD = 0.98) and unexpected/irrelevant (M = 2.51, SD = 1.02) treatments. There was no significant difference in purchase intent between unexpected/relevant (M = 3.39, SD = 0.96) and expected/relevant (M = 3.17, SD = 0.92) treatments or between any other in/congruity treatments.

Discussion

Findings of the present study indicate how the deliberate crafting of musical incongruity can be used to engage and amuse consumers, and advocate a hypothetical continuum of artful, deliberate deviation of musical incongruity, proposing that resolving such musical incongruity may enhance consumers’ responses such as recall, ad attitude, perception of brand image and quality, as well as their purchase intent. Results demonstrate how mild musical incongruity in advertising enables consumers to focus their attention and allows them to muster accessible cognitive resources for an intentional exploration of the incongruent event, resulting in enhancing consumers’ cognitive and behavioral responses to advertising through resolving the incongruity.

The findings of the present study suggest that the unexpected/relevant incongruity quadrant represented by Italian opera/reggae mashup produced the highest level of recall for all three recall components. The humorous amusement created by the mild musical incongruity may have been resolved through allocating higher level of cognitive resources, resulting in enhanced memory. On the other hand, findings indicate that severe musical incongruity created as a result of using unexpected/irrelevant music (Caribbean reggae) significantly impedes consumers’ recall of advertising information. In other words, recall is improved or impaired depending upon whether the abundant cognitive resources generated could help in resolving the incongruity or not.

The use of purposefully artful deviation situates the musical stimulus within an area of interpretive ambiguity capable of fostering symbolic elaboration. Findings of the current research indicate that the successful symbolic elaboration and resolution of mild musical incongruity may also lead to enhancing consumers’ attitudes and perceptions, which has not been explored in the extant body of literature. The results in the present research confirm that the psychological discomfort generated through severe dissonance may result in unfavorable attitude toward the advertisement. As the findings suggest, the musical unexpectedness in the mild incongruity condition (unexpected/relevant) may have resulted in enhancing the entertainment characteristic of the advertisement. A consumer may initially get interested in an advertisement for its entertainment value and this entertainment value of the ad may cause the consumer to remember it.

The results suggest that perceived image of the advertised brand may significantly differ in various congruity conditions. Findings reveal that the unexpected/relevant musical quadrant was responsible for producing the most favorable images of the brand (more exciting, pleasant, cool, and appealing). The expected/relevant quadrant produced the better response only in one of the image perception items (tense/relaxing). Considering the findings related to the ad attitude mentioned earlier, as the expected/relevant musical quadrant produced a slightly more favorable attitude toward the ad in terms of being more enjoyable. This resulted in transferring a more relaxing perceived image for the restaurant when Italian opera was used in the advertisement. Placed in the right context, the highly congruent Italian opera resulted in enhancing the underlying relaxing image for the advertised Italian restaurant.

Instead of using a stereotypically Italian music that is prototypical of the class in question and capable of activating the related knowledge structures concerning Italy, the application of this unexpected music (reggae) may be rewarded by allocation of more cognitive resources, and creating positive thoughts through the enjoyable experience of incongruity resolution. In other words, while the highly relevant Italian opera musical genre reinforces the advertising message and brand image, naturally transmitting and supporting an authentic impression of the Italian restaurant, the unexpected reggae style mixed with the opera has a deliberately underlying communicative purpose for its presence which is humor. This humorous deviation from expectation may then be followed by a resolution in which the congruity is comprehended.

Findings of the present research indicate that the successful resolution of mild incongruity may not only lead to positively affecting consumers’ perceptions of brand image compared to incongruent and severely incongruent quadrants (expected/irrelevant and unexpected/irrelevant quadrants), it may indeed result in a better perception of quality of food, which also positively affected participants’ purchase intent. In contrast, the unexpected/irrelevant incongruity quadrant associated with Caribbean reggae results in severe incongruity without resolution that may leave listeners confused and frustrated because they may not be able to get the purpose.

Drawing on Mandler’s (Citation1982) schema incongruity theory, the current study depicts resolution strategies for incongruity related to different changes in schema structure. The findings reveal that the internal processing activities consumers embrace in an attempt to resolve varying levels of incongruity may have evident consequences for their cognitive and affective (reflected in perceptions, recall, attitude formation, and persuasion) responses to advertising. This confirms the argument made by schema incongruity theory that mild schema-stimulus discrepancies can be successfully resolved, resulting in more positive subsequent responses through a psychological reward mechanism (Mandler Citation1982; Meyers-Levy and Tybout Citation1989). Such positive affect is believed to result from increased feelings of control and self-efficacy accompanying the “I get it” response (Bandura Citation1977). Positive feelings and emotions combined with a continued cognitive appreciation of resolution are then likely to enhance attitudes, perceptions, and evaluations of the advertisement and the brand. Moreover, allocation of more cognitive resources to resolve the incongruity may also enhance consumers’ recall of advertising information. Consequently, positive effects of resolving the mild musical incongruity on consumers’ affective and cognitive responses to advertising may also enhance consumers’ purchase intent.

In contrast, in the condition where the severity of musical incongruity is too extreme to be assimilated into existing schemas (unexpected/irrelevant music), consumers may ascertain that they need a wholly fresh schema that may contradict existing schemas, for the purpose of accommodating and possibly successfully resolving such intense musical incongruity. Accommodating and resolving a severe musical incongruity in the advertisement (figuring out the purpose behind using Caribbean reggae for an Italian restaurant) may take enormous effort on the part of consumers, both cognitively and emotionally, and demands considerable skills in utilizing psychological resources. Therefore, the irrelevant music used in the advertisement results in consumer failure to resolve the extremely intensive incongruity even after they try to make significant changes to the present schema structure.

Findings of the present research indicate that in the case of mild musical incongruity (Italian opera/reggae mashup representing the unexpected/relevant quadrant), participants tend to invest further processing time to review schematic knowledge and initiate new associative pathways or links that harmonize the meanings communicated by musical genre and country of origin with the existing product/brand knowledge. The process of discovering a meaningful linkage between the mildly incongruent music and the intended advertising message strengthens the associative network between stimulus and memory information that results in enhancing recall. However, as the level of mismatch becomes extreme (Caribbean reggae representing the unexpected/irrelevant quadrant), participants may consider any effort in processing the advertisement to be in vain. This may lead to diminished information processing and inability to establish meaningful associations between the message to be transferred by the background music and the restaurant image, which may in turn inhibit recall of advertising information for advertisements using irrelevant music. Findings of the current research also demonstrate how failure to come up with a satisfactory interpretation of the advertisement may lead to negatively affecting consumers’ perceptions, attitudes, and purchase intent.

Theoretical and practical implications

Developing effective advertising communication has been traditionally regarded as an increasing function of the congruity or fit between consumers’ perceptions and the content of the transmitted messages (Halkias and Kokkinaki Citation2013). Therefore, relevant research has predominantly examined several factors that would optimize this function, giving limited attention to the use of incongruity in advertising. The present research contributes to marketing communication literature through providing significant insight on how consumers react to stimulus element that is incompatible with established beliefs and perceptions.

In terms of theoretical contribution, the current study developed, refined, and redefined the concept of musical congruity in advertising through adapting Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) congruity model. It offered new definitions for expectancy and relevancy as the two dimensions of musical congruity, and introduced four quadrants of musical in/congruity, namely; expected/relevant, unexpected/relevant, expected/irrelevant, and unexpected/irrelevant.

From the perspective that an advertisement is a bundle of stimulus elements, the extant literature has not investigated in-depth the way incongruity resolution affects consumers’ responses to advertising. Moreover, few studies involving congruity were predominantly in print advertising and did not explain the effects in the context of advertising music. Consequently, the current research provides an original contribution to understanding the positive impact of using mildly incongruous music in advertising. In addition to contributing to consumer marketing literature through addressing the gap pertaining to the effects of music, as one of the most important executional cues in advertising, on communication effectiveness, the present research contributes to the impact of incongruity with schema-based expectations.

Extant marketing literature often equate incongruity with unexpectedness, and therefore, the existing research around the use of incongruity in advertisements does not produce conclusive findings (Halkias and Kokkinaki Citation2014; Segev et al. Citation2014). For instance, Torn and Dahlen (Citation2007) reveal how the discrepancy between the advertisement and brand schema may result in increasing attention, better recall, and a more positive ad attitude, compared to congruent advertisements. On the other hand, Dahlen et al. (Citation2008) demonstrate that the incongruity between advertisement and the brand may reduce the credibility of the ad and lead to lower ad attitude, compared to congruity. The review of literature, however, shows that the existing studies implement a dichotomous operationalization of incongruity that solely discerns what is congruent and what is not, neglecting the differences in the level of incongruity (Jhang, Grant, and Campbell Citation2012; Han et al. Citation2013). The current research addresses this issue in the context of musical incongruity in advertising. We involve Heckler and Childers (Citation1992) twin component congruity framework in the present research to increase our understanding of the effects of various levels of incongruity on consumer response to advertising. Findings offer the first empirical evidence for the process underlying cognitive and behavioral responses to the use of purposeful, mildly incongruent music in advertising.

The findings of the present research have managerial implications, primarily for companies within the restaurant industry, but could also be taken into consideration in other product and service industries. Firstly, it offers insights into using musical incongruity for enhancing advertising effectiveness, brand positioning, and managing consumer brand perceptions. Advertising agencies and client companies (restaurant owners in this context), gain insight in how consumers process advertising information and how the utilization of mildly incongruent music may help them to increase the effectiveness of their marketing communication campaigns. Mild musical incongruity may be rewarded through inducing a process-based influence form of psychological compensation, which may enhance the favorability of subsequent responses through satisfaction generated by successfully carrying out a more cognitively demanding task and resolving the incongruity. In this research, we have seen that advertisements accompanied by mildly incongruent music were more effective than other in/congruity quadrants in influencing purchase intentions of consumers. Advertisements that are incongruent with the ad schema attract a higher level of consumer attention, and therefore, consumers are more likely to recall the information in the ad. Advertising agencies and managers in the context of restaurant (as well as other business contexts) can utilize these insights to create effective messages that can be liked and well-remembered, through appropriate harnessing of the incongruity effect. Knowing the potential effects of musical in/congruity on consumer message processing and how the musical incongruity is processed in advertising will certainly help advertisers and business managers predict when and how musical incongruity in advertising is likely to lead to desirable communication effectiveness.

Advertisers should also be aware of the negative effects of using incongruent music on consumers’ minds. Irrelevant music used in an advertisement may cause psychological discomfort that will adversely affect consumers’ attitudes and evaluations of brands and advertisements, as well as their purchase intent. When the background music is in extreme conflict with consumers’ beliefs, attention to the advertisement declines. Incongruent background music is found to be useful so long as it contributes to making sense of the intended advertising message. Marketing practitioners may use incongruity-based strategies to enhance the effectiveness of their communication campaigns by attracting consumers’ attention and interest using novelty and surprise delivered by background music and making them actively participate in the communication process.

Limitations and future research

The findings of the present research further develop the existing research on the effects of in/congruity on attention and persuasion. Research has examined contingencies that may impact whether advertisements should be structured as congruent or incongruent. Zanjani, Diamond, and Chan (Citation2011) explore the effects of ad-context congruity upon ad recognition and memory for people with two orientations, i.e., information seekers and surfers. Information seekers view content with the aim of learning and surfers browse content casually with no specific purpose. The first orientation is more goal oriented in nature and those with an information seeking orientation may deem more congruent advertisements as more optimal, and thus pay more attention them, since such advertisements help them meet their information seeking goal. In contrast, the second orientation is more exploratory in nature. In such an instance, whether attention is paid to the advertisement will be driven mainly by the attention-getting properties of the advertisement. Prior work has suggested that a less congruent advertisement may not immediately comply with the mental schemas held by consumers, and as a result, may better attract initial attention (e.g., Goodstein Citation1993). Therefore, for consumers with an exploratory browsing orientation, less congruent advertisements may attract more attention. This discussion suggests that it is important that future research examines the effects of this contingency and explores the impact of musical in/congruity when consumers have an information seeking versus an exploratory browsing orientation.

McQuarrie and Mick (Citation1996) highlighted the importance of verbal and visual incongruity resolution. Both verbal and visual incongruity have been reported to elicit enhanced semantic processing (McQuarrie and Mick Citation1996) and recall (Houston, Childers, and Heckler Citation1987) as listeners seek meaningful reconciliation of the deliberate violation of expectations they have encountered (Oakes Citation2007). Therefore, future research could replicate the current study in the context of TV advertising, exploring the effects of using artfully incongruent music and its coherent integration with visual elements of the advertisement.

Another limitation of the present research is that the study sample was selected from undergraduate students. Therefore, future research might provide advertisers and restaurant owners with additional insights into the effects of advertising music through including a more diverse respondents from various backgrounds and higher income level.

According to Petty and Cacioppo (Citation1986), an executional cue such as background music in advertisements has its prevalent effects on low-involvement consumers’ attitude formation process. Based on this, in the case of a simple product having few attributes, persuasion may be more successful by using background features such as music or visual imagery (Kotler Citation1973; Batra and Ray Citation1983). Future research could also test this assumption through exploring the effects of mild musical incongruity for advertising high-involvement products, involving a higher level of attributes, risk, and money. Furthermore, reviewing the extant literature in the area of music and advertising indicates that there is a general gap in terms of the lack of qualitative research in music and advertising (Abolhasani, Oakes, and Oakes Citation2017). This is in line with the findings of the study by Hanson and Grimmer (Citation2007), highlighting the dominance of quantitative research in marketing. Future research could delve into the lived experience of music in advertising from a consumer perspective.

References

- Abolhasani, M., and S. Oakes. 2017. Investigating the influence of musical congruity in higher education advertising: A genre congruity perspective. In Advances in advertising research, Vol. VIII, 183–96. in Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-18731-6_14.

- Abolhasani, M., S. Oakes, and Z. Golrokhi. 2020. Advertising music and the effects of incongruity resolution on consumer response. In Advances in advertising research, Vol. XI, 183–93. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

- Abolhasani, M., S. Oakes, and H. Oakes. 2017. Music in advertising and consumer identity: The search for Heideggerian authenticity. Marketing Theory 17 (4):473–90. doi: 10.1177/1470593117692021.

- Ali, M. A., Y. M. Srinivas, and M. S. Bhat. 2012. The effectiveness of music in humorous advertisements. BVIMR Management Edge 5 (2):103–17.

- Allan, D. 2008. A content analysis of music placement in prime-time television advertising. Journal of Advertising Research 48 (3):404–17. doi: 10.2501/S0021849908080434.

- Alpert, J. I., and M. I. Alpert. 1990. Music influences on mood and purchase intentions. Psychology and Marketing 7 (2):109–33. doi: 10.1002/mar.4220070204.

- Alpert, M. I., J. I. Alpert, and E. N. Maltz. 2005. Purchase occasion influence on the role of music in advertising. Journal of Business Research 58 (3):369–76. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00101-2.

- Areni, C. S., and D. Kim. 1993. The influence of background music on shopping behavior: Classical versus top-forty music in a wine store. Advances in Consumer Research 20 (1):336–40.

- Babin, L. A., A. C. Burns, and A. Biswas. 1992. A framework providing direction for research on communications effects of mental imagery-evoking advertising strategies. Advances in Consumer Research 19 (1):621–8.

- Bailey, N., and C. S. Areni. 2006. When a few minutes sound like a lifetime: Does atmospheric music expand or contract perceived time? Journal of Retailing 82 (3):189–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2006.05.003.

- Ballouli, K., and B. B. Heere. 2015. Sonic branding in sport: A model for communicating brand identity through musical fit. Sport Management Review 18 (3):321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2014.03.001.

- Bandura, A. 1977. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.