ABSTRACT

A significant proportion of academic spin-offs (ASOs) are founded by entrepreneurial teams (ETs). Yet little is known about how these ETs are formed or the role of technology transfer offices (TTOs) in this formation process. This article examines whether and how TTOs affect the formation of academic spin-off entrepreneurial teams (ASO-ETs). To this end, we study in detail the formation of seven ETs behind life-science ASOs developed in one region in Norway. Our findings show that ASO-ETs followed different paths of formation, partly mirroring the organization of the TTOs. We further identify four different roles played by TTOs, two direct and two indirect, that shape the formation of these ETs. Based on organization imprinting theory, we contribute to the team entrepreneurship literature by developing a new framework showing how TTOs imprint the formation of ETs in ASO settings.

Introduction

The topic of this study is entrepreneurial team (ET) formation in academic spin-offs (ASOs). Specifically, we address the role of technology transfer offices (TTOs). The creation of ASOs is one of several possible ways to commercialize technologies generated by universities and public research institutes (Huyghe et al. Citation2014; Politis, Gabrielsson, and Shveykina Citation2012). In fact, many countries and universities have recently promoted policies to encourage the creation of more ASOs from university inventions (Schaeffer and Matt Citation2016; Shane et al. Citation2015). Interestingly, most of these ASOs are founded by teams rather than individuals (Rasmussen and Wright Citation2015; Visintin and Pittino Citation2014). In spite of this, there are few studies on how these ETs are formed (Nikiforou et al. Citation2018; Vanaelst et al. Citation2006). Most importantly, whether and how TTOs affect the formation of academic spin-off entrepreneurial teams (ASO-ETs) (Fryges and Wright Citation2014) has been overlooked in the literature.

As a precursor and vital element of the organizational founding process (Hormiga, Hancock, and Jaría Citation2017), understanding how ASO-ETs are formed and what role TTOs play in the formation process is crucial for both theory and practice. First, research has shown that ET composition and dynamics are among the most important factors influencing the success of ASOs (Diánez-González, Camelo-Ordaz, and Ruiz-Navarro Citation2016; Grandi and Grimaldi Citation2003; Politis, Gabrielsson, and Shveykina Citation2012). Nonetheless, the composition and dynamics of the ETs may depend on how they are formed. Furthermore, whether and how others join the venture founding process may have long-lasting consequences for the survival and performance of new ventures (Forsstrom-Tuominen, Jussila, and Goel Citation2019; Muñoz-Bullón et al. Citation2015; Ruef, Aldrich, and Carter Citation2003) by bringing more information to or constraining later actions in the venture (Beckman Citation2006). Thus, understanding the formation of ASO-ETs is the first step to understanding the founding process of ASOs, and it may help to explain the behaviour and performance of ASOs (Kim and Aldrich Citation2004; Ruef Citation2010). Second, although prior studies have shown that different institutional set-ups influence the number of spin-offs created by research organizations (Di Gregorio and Shane Citation2003) and impact resource endowment to the created spin-offs (Moray and Clarysse Citation2005), little is known about how differences in the support system affect the early stages of the start-up process (Fini et al. Citation2017; Fryges and Wright Citation2014; Huyghe et al. Citation2014), particularly the ASO-ET formation process. This is surprising because, from organizational imprinting theory, we know that decisions made by entrepreneurs at the early stages of the venture founding process are the mechanisms through which new organizations obtain important features from their contexts (Johnson Citation2007). Thus, to understand what features from the context are imprinted on ASOs one needs to examine how the context affects the formation process of the ASO-ETs. Third, from a policy perspective, knowing how ASO-ETs form and what roles are played by TTOs may help to design policy instruments that will facilitate the formation of successful teams, as well as ASOs, and support them throughout the entrepreneurial process.

In this study, we define an ET as two or more entrepreneurs who organize a new venture having joined the formation process before the new organization’s first main product/service is fully developed. Thus, we use the establishment of the main ends-means framework in the new venture (Harper Citation2008) as a marker for the completion of the ET formation process.Footnote1 Once the ends-means framework is established, the next step will comprise making the established framework efficient and effective (Harper Citation2008) such that the ET may evolve into a management team (Vanaelst et al. Citation2006).Footnote2

To achieve our research objective, we studied seven cases of ASO-ET formation in a single Norwegian region. Since the abolishment of the so-called the ‘professor privilege’ in Norway in 2003, in which academics retained ownership of intellectual property (Rasmussen and Borch Citation2010; Bjørnåli and Gulbrandsen Citation2010), TTOs and other support organizations in the region we studied have passed through different re-structuring processes. Coupled with the legislative and regulatory changes, this context provides us favourable grounds to explore the phenomenon we set out to study. Our results show that the ASO-ETs indeed followed different formation paths, depending on how the TTOs were organized at the time. Furthermore, we identified four important roles played by the TTOs in ET formation, two direct and two indirect. The TTOs played different roles at different times, and this is reflected in the formation paths followed by the ASO-ETs.

By investigating the formation of these ETs and enhancing our understanding of formation processes beyond the traditional lead-entrepreneur approach (see next sections), we have made several contributions to the literature. First, we contribute to the academic entrepreneurship literature by providing new insights into how TTOs affect the formation of ASO-ETs. We identify two direct and two indirect roles through which TTOs affect the ASO-ET formation process. These insights suggest that when policymakers and TTOs change the organization of technology transfer activities they need to consider the potential impact on ETs and their formation. Second, we contribute to the literature on ET formation by developing a framework that shows how contextual factors, particularly TTOs, imprint the formation of ASO-ETs, which responds to the call for studies examining the role of context in shaping ET formation strategies and processes (Lazar et al. Citation2020). The three models in the extant literature that provide alternative explanations for ET formation (i.e. the rational model, the social-psychological model, and the dual strategy model) largely disregard context as an important factor in shaping the ET formation process. By demonstrating the need to consider ETs and TTOs from more dynamic perspectives of entrepreneurship with contexts (Gaddefors and Anderson Citation2019), we elucidate the dynamic role of TTOs in the formation process of ASO-ETs. Third, by linking current theoretical perspectives on ET formation to the entrepreneurship literature and organizational imprinting theory, we extend the latter to the team level. We argue that the four roles played by TTOs form ‘paths’ of social conditions that make an imprint on ASO-ETs at the time of forming. This responds to the call for more studies to address the imprinting process, which has remained largely underexplored (Simsek, Fox, and Heavey Citation2015).

Theoretical background

Perspectives on ET formation and organizational imprinting theory

ETs are formed for a very broad range of reasons (Hormiga, Hancock, and Jaría Citation2017). Nevertheless, three models in the literature provide alternative explanations for this formation (Forbes et al. Citation2006; Lazar et al. Citation2020). The first, the rational model, suggests that ETs are formed based on instrumental criteria, where the desire to fill a particular resource need is the main motive behind adding a new member to an ET (Forbes et al. Citation2006; Smith Citation2007). To add a member, the lead entrepreneur conducts a resource dependence analysis to check for any critical needs that he/she cannot cover (Ben-Hafaiedh Citation2010), followed by a constellation of decisions regarding how to find, choose, and convince partners to join the team (Kamm and Nurick Citation1993). In the second model, the social-psychological model, interpersonal relations rather than economic consideration are the key factor determining who joins the ET (Aldrich and Kim Citation2007; Ruef, Aldrich, and Carter Citation2003). Thus, the desire of existing members to duplicate their own qualities or preserve the team atmosphere determines who will join the ET (Forbes et al. Citation2006). In the third model, Lazar et al. (Citation2020) suggest that ETs follow a dual strategy combining the rational and social-psychological models, either simultaneously or sequentially.

Although these perspectives may be valid in many cases, they make two implicit assumptions. First, they assume that all ETs are the same, irrespective of the contexts in which they emerge and operate. Yet research has shown that the perspectives in the literature may not explain the formation of certain types of ETs, such as family ETs (Discua Cruz, Howorth, and Hamilton Citation2013) and ASO-ETs or ETs in accelerator settings (Lazar et al. Citation2020), due to differences in control and decision rights. Second, all the perspectives portray ET formation as a strategic decision made by the lead entrepreneur(s), who identify, select, and recruit team members (Smith Citation2007). This assumption also seems to prevail in the ASO literature (McAdam and McAdam Citation2008; Würmseher Citation2017). However, as argued by Forbes et al. (Citation2006), ET formation might not always be a strategic choice and the involvement of some team members might not always align with the desires of existing members. Rather, it may occur in accordance with ‘criteria imposed by other forces, such as institutions providing resources and government regulations’ (Forbes et al. Citation2006, 232). In line with this ‘institutional view’ (Forbes et al. Citation2006), we challenge previous assumptions by emphasizing the need to explore the importance of context (Welter and Gartner Citation2016; Anderson and Gaddefors Citation2017; Gaddefors and Anderson Citation2017), and specifically how institutional factors affect the ET formation process. In fact, in their recent literature review on ET formation, Lazar et al. (Citation2020, 31) call on future research to ‘recognize the role of context in shaping entrepreneurial origins and formation strategies for a more holistic understanding of cause-effect relationships and mechanisms at play’. Responding to this call, we investigate how TTOs affect the formation of ASO-ETs in a single Norwegian region.

In our study, we found the theory of organizational imprinting (Stinchcombe Citation1965) a useful lens for shedding light on the multifaceted phenomenon we are investigating. According to this theory, founding conditions – the social structure at the time of founding – affects the initial characteristics of organizations, which will have a long-lasting effect on them (Bryant Citation2014; Johnson Citation2007; Marquis and Tilcsik Citation2013). In line with this, Rasmussen and Wright (Citation2015) assert that during their early stages of development, ASOs depend heavily on the decisions of, and resources provided by, their parent institutes, and that these decisions may have an enduring effect on their development. Thus, ASOs are imprinted by the social conditions i.e. ‘groups, institutions, laws, population characteristics, and sets of social relationships that form the environment of the organization’ (Huynh et al. Citation2017, 11) prevalent during the creation phase (Stinchcombe Citation1965, 142). Venture founders are also identified as among the most important imprinters and have a lasting impact on the future of the new organizations (Marquis and Tilcsik Citation2013).

New venture founders imprint organizations in several ways by influencing the initial strategy (Boeker Citation1989), exit strategies (Albert and DeTienne Citation2016), or positions created (Beckman and Burton Citation2008; Burton and Beckman Citation2007). The position imprinting process is specifically interesting for the ET formation literature. This is because some of the most important activities and decisions at the founding stage of new organizations relate to its structure, including how roles and positions are assigned, organized, and formalized within the venture (Jung, Vissa, and Pich Citation2017). Research has shown that positions created at venture founding will be of lasting significance to the venture, and that the initial incumbents play a critical role in defining organizational positions (Beckman and Burton Citation2008). Interestingly, the imprinting literature mostly takes the composition of the founders for granted, as most studies consider founders only as imprinters or sources of imprints for new organizations (Boeker Citation1989; Simsek, Fox, and Heavey Citation2015). Thus, the ET formation process is not considered to be part of the imprinting process, leaving the early stage of the imprinting process unclear. Nevertheless, the ET formation process might not only affect the composition of the team that defines the initial positions, but the dynamism of this process could also bear an imprint from the context in which it occurs (Lazar et al. Citation2020). Understanding how context matters and leaves its imprints on ETs would provide a more complete picture of the imprinting process in new organizations.

According to Simsek, Fox, and Heavey (Citation2015), imprinting is not a ‘one-off episode’ where the imprinter stamps certain characteristics on the imprinted entity, but rather involves a process. Despite this, empirical studies on the topic are variance-oriented and tend to ignore the processual nature of imprinting (Simsek, Fox, and Heavey Citation2015). Consequently, how the imprinting process occurs is largely underexplored. Our study examines how certain features of imprinters, particularly TTOs, affect ET formation in ASO settings through their interactions. ASOs do indeed provide fertile ground for investigating the impact of institutional context on start-ups and its imprinting effects (Mathisen and Rasmussen Citation2019).

Technology transfer, ASOs and ETs

Following changes to the legislation of several countries aimed at increasing the rate of technology transfer and commercialization, many universities and public research institutes established TTOs (Link and van Hasselt Citation2019) to manage the process (Mathisen and Rasmussen Citation2019; Rasmussen and Borch Citation2010; Siegel, Veugelers, and Wright Citation2007). Although technology can be commercialized in different ways, licencing and patenting have traditionally been the preferred methods (Siegel, Veugelers, and Wright Citation2007). Recently, however, many countries and universities have promoted policies encouraging the creation of more spin-offs (Rasmussen and Borch Citation2010; Schaeffer and Matt Citation2016; Shane et al. Citation2015), leading to the creation of more ASOs.

Partly because of both diverse resource sets and expertise and the relatively longer process required to develop them, ASOs are typically founded and managed by teams (Nikiforou et al. Citation2018; Mathisen and Rasmussen Citation2019; Rasmussen and Wright Citation2015). ASOs founded by teams have also been shown to be more successful than those created by individuals (Müller Citation2006). Research has shown that ET composition is an important factor that affects different dimensions of ASOs, such as performance (Huynh et al. Citation2017; Knockaert et al. Citation2011; Lundqvist (Citation2014); Visintin and Pittino (Citation2014)), commercialization strategy (Conceicao, Fontes, and Calapez Citation2012), internationalization (Bjørnåli and Aspelund (Citation2012)), and the evaluation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Scholten et al. Citation2015). However, despite this emphasis on the importance of ET composition to ASO success, very few studies, apart from those by Clarysse and Moray (Citation2004) and Vanaelst et al. (Citation2006), have dealt with how the ET’s composition is decided, or, in other words, how an ASO-ET is formed (Nikiforou et al. Citation2018).

Clarysse and Moray (Citation2004, 55) followed the formation of one ASO-ET and described how the team ‘copes with crisis situations during the start-up phase’. They conclude that shocks in the founding team co-evolve with the venture. Similarly, Vanaelst et al. (Citation2006) found that the composition of the team evolves as the venture passes through four development phases. For instance, in phase one a pre-founding team comprising researchers and privileged witnesses will be formed. The role of the privileged witnesses is limited to coaching (Vanaelst et al. Citation2006). Moving to phase two, the researchers will decide to pursue the creation of a spin-off and the pre-founding team evolves into a top management team and board of directors.

Although these studies contribute to our understanding of ASO-ET formation, they also have limitations. First, they do not address the academic dimension directly, and the team formation described in the studies could occur in any other high-tech start-up developed by scientists (Visintin and Pittino Citation2014). In line with this, Nikiforou et al. (Citation2018) call for more detailed research to investigate the impact of the originating institutions on ASO-ET formation. Second, existing studies investigate the process within a stable environment. Thus, they do not discuss how the formation of ASO-ETs could be affected by changes in environmental conditions. Furthermore, in the settings covered by these studies it seems that the role of the privileged witnesses, including TTOs, is limited to providing the researchers with assistance. However, we would argue that the technology transfer process can be more complex than this, depending on how TTOs are organized. Understanding this would help to identify any systematic difference in ET formation across ASOs in both the same and different contexts (Nikiforou et al. Citation2018). Indeed, Vanaelst et al. (Citation2006) acknowledged this and emphasized the need to study the formation of ASO-ETs in different institutional contexts. Our study addresses these two limitations.

Although the literature has not addressed the impact of TTOs and their role in ASO-ET formation, it has documented their impact on the technology transfer process in general. In a recent literature Mathisen and Rasmussen (Citation2019, 1914) suggest that TTOs play an important role in areas such as ‘IPR [intellectual property rights] and patenting, seed funding, building legitimacy, networking, management advice, and facilitating access to business services’. In line with this, Arvanitis, Kubli, and Woerter (Citation2008) and Coupé (Citation2003) show that the presence of a TTO is one of the main determinants of patenting in universities. Furthermore, TTOs interact and provide researchers at the parent institution with both advice and training with respect to the technology transfer process and entrepreneurship (Micozzi et al. Citation2021). Hence, TTO quality partly affects researchers’ behaviour and decisions concerning invention disclosure (Walter et al. Citation2018). TTOs assist academic entrepreneurs who are setting up ASOs to evaluate the potential of ideas, write a business plan, and find both financial and industrial partners, as academic entrepreneurs may lack the necessary management skills (Colombo and Piva Citation2008; Micozzi et al. Citation2021).

As much as TTOs affect the technology transfer process from their parent organizations, both internal and external factors affect their performance. Internally, factors such as size (Siegel, Waldman, and Link Citation2003), experience (Kolympiris and Klein Citation2017), organizational structure (Debackere and Veugelers Citation2005), and managerial practices (Lee and Jung Citation2021) play an important role. Externally, institutional and environmental factors (Siegel, Waldman, and Link Citation2003), at both university and government level, affect TTO performance. For instance, Huyghe and Knockaert (Citation2015) demonstrate how universities can encourage researchers to commercialize their inventions by incorporating entrepreneurial intentions in their missions. At macro level, regulation and policy interventions are the most significant factors affecting the work of TTOs (O’Kane et al. Citation2020). In fact, Siegel, Waldman, and Link (Citation2003) argue that these institutional and environmental factors partially explain variations in TTO performance. Besides affecting TTO performance, these policies may have a direct or indirect impact on the ASOs created through the TTOs and may even shape their growth trajectories (Mathisen and Rasmussen Citation2019). Similarly, we would argue that policies and regulations might also affect the ASO-ET formation process directly or indirectly, through TTOs.

Studies addressing the importance of the institutional environment for ASOs mostly focus on how the institutional set-up affects the number and type of spin-offs (Mathisen and Rasmussen Citation2019; Mustar et al. Citation2006), overlooking how and why this occurs (Fini et al. Citation2017), and mostly addressing the process from the standpoint of the parent organization (Mustar et al. Citation2006). In addition, studies taking an institutional perspective are ‘typically static in nature and focus upon the link at a single point in time’ (Mustar et al. Citation2006, 295). Thus, the literature sheds little light on how both changes in legislation (Fini et al. Citation2017) and differences between and changes to the support system, including TTOs (Fryges and Wright Citation2014), affect ASO creation, which warrants additional research.

Research design and methods

Given the limited research dealing with ASO-ET formation (Nikiforou et al. Citation2018), particularly the possible role of TTOs in this process, we adopted an abductive multiple case study approach (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002). This allowed us to address and analyse how ETs are formed in ASO settings. We selected multiple cases in one region, where we knew from prior studies (e.g. Grønning Citation2009) that new ASOs had been created to commercialize research by both universities and public research institutes.

Choice of research site

Our study is based on purposive sampling techniques to relate our findings explicitly to theory (Eisenhardt Citation1989; Yin Citation1994). We clarified a set of conceptual criteria (region, industry, ASOs, ETs) early on to define a homogenous area in which cases are comparable (Rihoux and Ragin Citation2009). All our cases originated at a recognized public university and university hospitals located in one region in Norway. The decision to focus on ETs originating in one region is appropriate for several reasons. First, it enhances comparability across cases and makes the conclusions more valid. Research has shown that the region is an important factor that may determine who sets up new ventures (e.g. Packalen Citation2015), and hence needs to be controlled for when analysing ET formation. Second, the research question we posed requires data collection at different levels (the ET and different actors in the support system) and hence the research should ideally be conducted in a single region. Third, the region we chose has witnessed changes both in the regulations governing the commercialization of academic research and TTOs, which makes it suitable to address this study’s research question.

In addition to the region, we chose ETs operating in a single sector, life sciences. Several studies have suggested that sectoral contextualization can improve understanding of ASO emergence (Nikiforou et al. Citation2018; Conceicao, Fontes, and Calapez Citation2012; Gabrielsson, Landström, and Brunsnes Citation2006) and ET formation in general (Garrone, Grilli, and Mrkajic Citation2018). This sector is conducive to research on ETs for different reasons. First, founding life-science ventures is inevitably a collective effort, because of the wide range of skills and resources it requires (Whittington, Owen-Smith, and Powell Citation2009), as well as the long lead-time (Hine and Kapeleris Citation2006). This long lead-time also makes the sector suitable for studies designed longitudinally to investigate the effect of change. Second, life sciences offer a suitable setting to study innovation-based entrepreneurship, because the sector’s R&D process is exploratory (Oliver Citation2004), which usually leads to the development of new products, tools or business models (Majumdar and Kiran Citation2012). Finally, as argued by Owen-Smith and Powell (Citation2004), the sector is a good representative of science-based industries in general.

The research context

Improving the link between university and industry has been a concern among Norwegian policymakers and university professors for decadesFootnote3 (Gulbrandsen and Nerdrum Citation2007b). Yet the most important policy change in relation to academic research commercialization occurred in 2003, when higher education institutions became the owners of inventions emerging from publicly funded research conducted by their employees. Subsequently, publicly funded TTOs and seed capital funds were established (Bjørnåli and Gulbrandsen Citation2010). Since then, the TTOs and other support organizations have passed through different re-structuring processes. shows the important milestones and changes observed in the organization of TTOs in the region we studied.

The years 2003 and 2011 mark the end of period I and period II, respectively, because of the landmark changes made to rules and regulations affecting ownership and decision-making rights over commercialization of inventions generated by university- and hospital-based research in the region. As depicted in , before 2003 two TTOs managed the transfer of technology from public research institutes in the region. TTO1, created in the late 1980s, helped Hospital1 to collaborate with industry. TTO2, on the other hand, was established in the mid-1980s to lead technology transfer activities from Hospital2, one of the first hospitals in Norway to introduce a regulatory framework similar to the Bayh-Dole Act in the USA. Following the national change to IPR law in 2003, and the merger of Hospital1 and Hospital2 to create University Hospital1, the two TTOs merged in 2007. However, before the merger, two important actors emerged. TTO1 created a financial arm, Facilitator1, in collaboration with private investors. Meanwhile, INNINV was founded as an institutional investor using the capital accumulated in TTO2 prior to its merger with TTO1. Finally, TTO1 itself merged with TTO3, a TTO attached to University1 early in the 2010s to create TTO4. Each of the TTOs followed different policies and practices with regard to transfer technology from their parent institutions. summarizes the most important of these practices in each of the TTOs.

Table 1. Overview of TTOs that has been operating in the region

Case identification and selection

To identify potential cases, we consulted key life sciences cluster member lists and industry databases, key informant interviews, recurrent observations of industry seminars/conferences, relevant science and industry collaborating events, and spoke to ET members. We continued the identification process until cases started recurring in our list. We stopped adding more cases to our analysis when we started observing a similar pattern in the newly added cases, indicating theoretical saturation (Eisenhardt Citation1989). Although the cases were selected from one region, they started their formation process at different times (between the early 1990s and early 2010s), which provided significant variation across cases. Consequently, the ETs (and their ventures) were at different stages of development by the time we collected the data. summarizes the cases we studied and used in the analysis.

Table 2. Overview of cases

Data collection and analysis

We gathered data from both primary and secondary sources through multiple data collection techniques to ensure sufficient details and data triangulation. We collected primary data through interviews with ET members, key informants, and both former and current CEOs of TTOs and other support organizations. In line with our definition of ETs, we required people to fulfil at least three of the following four criteria to be considered as member of an ET in our study: a) is involved in creating the business idea; b) holds an equity in the venture; c) is involved in jointly transforming ideas into enterprise conceptions; and d) was part of the team before the development of the first product, on which the initial ends-means framework of the venture was based.

We developed separate interview guides for the semi-structured interviews with ET members and executives from the support organizations. Both authors were present for all interviews except one, which enhanced follow-up questions and analytical probing (Kreiner and Mouritsen Citation2005). Interviews lasted from 1 hour to 2 hours 53 minutes. In total, we conducted 18 interviews, nine with individual ET members, and nine on the institutional side (TTOs and their subsidiaries), which produced a total of 30 hours 19 minutes of interview data. We recorded and fully transcribed all interviews.

We also collected secondary data, such as the LinkedIn accounts of ET members, company websites (we visited their websites regularly over three years), annual reports and press releases of the ventures, TTO annual reports, media reports related to the ventures, and published research articles and consultation reports about the region’s life-science sector.Footnote4 We also used a company registry database, proff.no, to trace major activities that occurred in the ventures (i.e. changes to ownership structure, management, and board membership). We also participated in several industry seminars as observers.

The collected data provided narratives of the ET formation process and a factual description of the context and actors involved in the process (Zahra and Wright Citation2011). Based on this, we analysed each case individually by writing a detailed case narrative for each team (Eisenhardt Citation1989). We further conducted cross-case analysis by using a temporal bracketing strategy (Langley Citation1999) to identify similarities and differences between cases (Eisenhardt Citation1989). We identified three periods during which the TTOs change their way of organizing, which in turn is partly influenced by changes in legislation. The time scale at the bottom of shows these periods with differences in terms of how TTOs were organized in the region. As it is difficult to simultaneously capture the influence of the two types of changes, legislation and TTO related, temporal bracketing helped us to structure the process analysis and our sensemaking (Langley Citation1999) by bracketing one of them. In temporal bracketing, periods are not phases ‘in the sense of a predictable sequential process but simply a way of structuring the description of events’ (Langley Citation1999, 703). Our within- and cross-case analysis of the data revealed both similar and different patterns across the cases. Below, we analyse our findings and discuss them in relation to the literatures on academic entrepreneurship, ET formation and organizational imprinting.

Findings and analytical discussion

Genesis of ETs revisited

The ET literature (Forbes et al. Citation2006; Ruef, Aldrich, and Carter Citation2003; Smith Citation2007), generally views ET formation as a decision-making process based on either rational (instrumental) criteria (Aldrich and Kim Citation2007), social-psychological considerations (Ruef, Aldrich, and Carter Citation2003), or a combination of both (Lazar et al. Citation2020), in which the lead entrepreneur(s) identify, select and recruit team members (Smith Citation2007). However, our findings indicate that ASO-ET formation is not always a strategic decision by the lead entrepreneur(s) as suggested in the literature. Rather, it is affected and shaped by TTOs and how they are organized in the setting in which the teams are formed. In other words, it is the TTOs, rather than the lead entrepreneurs, who identify, select, and organize the team. When they do not directly play this role, they shape the ASO-ET formation process indirectly (more discussion on this in the next section). Interestingly, the TTOs play these roles differently over time, and this is demonstrated by the different formation paths followed by the ETs considered in our study, as the TTOs organize themselves differently across the three periods we identified.

The two ETs in our study that created their ventures prior to 2003 (Period I) were formed by the researchers, who took the initiative to launch the ventures and form a team around themselves. Yet the two teams followed different paths during the early period of their formation. In venture Alpha, the researcher behind the invention was not necessarily expected to work with the TTO attached to the public institute, but he chose to do so, which led to the involvement of TTO1 in the ET and venture formation. In venture Gamma, on the other hand, the researchers had to report their idea to TTO2 because of the regulations effective at the hospital where they were employed. However, TTO2 allowed the researchers to proceed in their own way because it lacked resources at that time. This flexible interpretation of the regulations was probably possible because they were only in force at that particular hospital. One of the co-founders of venture Gamma recalls:

They [TTO2] said, ‘Hmmm looks very interesting. It looks very difficult … but we don’t have any resources to help you with patents, we are fully employed with all the fighting things with [venture BetaFootnote5].’ So they said, very straight, ‘We have notified your DPFI (Declaration of Potential Financial Interest), but you are allowed to go by yourself.’ Today, it would never happen.

The ventures created between 2003 and 2010 (Period II) had all passed through the TTOs attached to the institutions where the researchers behind the ventures were employed, because of the new national legislation introduced in 2003. How TTOs were organized at the institutes (e.g. TTO1 had a subsidiary facilitating organization dedicated to commercializing life-science inventions), seems to affect the path each ET followed and their composition. For instance, the members of the ETs behind ventures Delta and Zeta all came from Facilitator1 (the subsidiary of TTO1), which did not exist in period I. The difference between the period I and period II cases is further highlighted by the experience of the partly serial ET in venture Epsilon, in which two of the researchers were not allowed to manage their shares in the ventures created out of their research. This policy changed after 2010/11, and the researchers managed to buy back and administer their shares. Following this change, members of ETs formed during period III (post-2010/11) could own and manage their shares themselves from day one. This made a difference with regard to who would become owner of the venture and make strategic decisions, including decisions related to who could and could not become part of the ET. Furthermore, after the merger of TTO1 and TTO3 to form TTO4 in 2010, technology transfer of academic research in the region was centralized and Facilitator1 was terminated in the early 2010s. This led to the departure of some ET and board members who joined ASOs formed with the help of Facilitator1 during period II. In sum, this indicates that the region’s changing TTOs affected the ASO-ET formation.

Our findings suggest that the ASO-ET formation process strictly follows neither of the models in the ET formation literature. The process depends on how the TTOs were organized and the regulations governing the transfer process. This resonates with the proposition by Forbes et al. (Citation2006, 232) that ET formation might be affected by institutional factors, such as ‘government regulations and other actors who provide resources for the team’. In other words, borrowing the words of Stinchcombe (Citation1965) and extending the arguments in organizational imprinting theory (Johnson Citation2007; Marquis and Tilcsik Citation2013), we contend that ASO-ETs founded during a particular period and setting can be affected by the social conditions at that time. The next question is then related to the ‘how’ aspect of the imprinting process – how do social conditions imprint ASO-ETs?

Variability in newness: imprinting influences in ET formation

In organizational imprinting theory, an imprint of social conditions is said to be formed as a result of an interaction between ‘the imprinters (the source of imprints) and the imprinted (the target entity that bears the imprint)’ (Simsek, Fox, and Heavey Citation2015, 290). The list of imprinters includes individual founders (e.g. initial position holders), teams (their composition and diversity) and the environment (including regulatory conditions as well as institutional and cultural norms). Based on our findings, however, we contend that the founders’ composition and diversity is not only an imprinter but also something that is imprinted during the ET formation process.

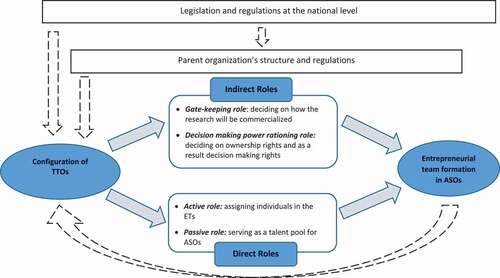

Furthermore, following the suggestion of Simsek, Fox, and Heavey (Citation2015), and responding to the call to investigate ‘how’ the imprinting process occurs (Mathias, Williams, and Smith Citation2015), we develop a framework explaining how a TTO imprints ASO-ET formation. The framework (see below) shows that TTOs imprint ASO-ET formation both directly and indirectly. It further shows that the ET formation process may influence TTOs by modifying the human capital that TTOs have at their disposal. Interestingly, we observe all the roles played by TTOs at work in our cases, but the way they affect the formation appears different, as elaborated below.

Indirect roles

Our findings suggest that the influence of TTOs plays out in two important ways that indirectly determine who will be involved in the ETs (see ). The first role played by TTOs at the idea stage (Kamm and Nurick Citation1993) is a ‘gate-keeping role’, when a decision has to be made on whether to commercialize the research and how. By the idea stage, we do not mean the stage where the idea is ready for commercialization and transfer, but a work-in-progress idea that is enough to initiate an entrepreneurial venture.

This gate-keeping decision for idea commercialization is an important factor in determining the ET formation and may affect it both positively and ‘negatively’.Footnote6 On the ‘negative’ side, the TTOs decided to licence out most of the inventions, giving researchers no chance to create a team to commercialize their inventions, regardless of their interest, and hence there was no need for ET formation. This was particularly true for ideas in life sciences. Once sufficient data was collected for life science inventions, TTOs would look for opportunities to licence the technology to an established firm, because developing it further through an ASO is expensive and time-consuming.

On the ‘positive’ side, TTOs may also persuade researchers to get involved in taking the idea further and join the team in the newly created ventures, even if the researchers had no plans for this initially. Venture Delta provides one example of this. One of the co-founders of venture Delta recalls:

We realized that it seemed to work quite well in the first experiments, and I don’t think I had heard about patents at all before. I was … at least, that was not in my mind, to try to protect this idea or to make a company at all. … I did not really think I had that mission [of starting a company] yet … they wanted me to take the responsibility as the first employee.

This implies that TTOs can affect team formation indirectly at the idea stage by creating or removing a barrier for the researchers to proceed. This finding is in line with Schaeffer and Matt (Citation2016), who highlighted that the features of a TTO may influence the start-up model implemented by universities. Our findings extend this by showing that the features of a TTO influence not only on the start-up model, but also the ETs who will be responsible for creating the ventures and taking them forward. Thus, in addition to imprinting the ASOs and ETs, the TTOs also leave their imprint on ET members and their choice of career path. The imprinting literature suggests that ‘conditions experienced in the early years of organizational tenure or a career exert a lasting influence on subsequent habits, routines, and behaviours’ (Tilcsik Citation2014, 641). Our findings show that TTOs play an important role for ASO-ETs by encouraging (or discouraging) researchers to take a career path in the ASOs.

Interestingly, this ‘gate-keeping role’ seems affected by how the TTOs were organized. For instance, in period II, when Facilitator1 was operating as a subsidiary of TTO1, several spin-offs and ETs were created. One of the co-founders of venture Delta recalls:

[It] has been a fashion over the years. So, at that time, it was not [TTO1] itself that was instrumental in starting the company. It was this [Facilitator 1] that wanted, that has the mission of starting companies on the best ideas from the TTO. And there have been different CEOs in the TTO and different boards. Therefore, for a period, many companies were started, and then they said no to a lot of companies.

This shows that the presence of Facilitator1 led to the formation of several ETs and ASOs. Later, when TTO1 was reorganized, Facilitator1 was closed, and a new CEO and board members arrived at the TTO, it was not possible for many potential ETs to form.

In period III, INNINV played this role by convincing both the TTOs and inventors from the university and University hospital to commercialize technologies through ASOs. The CEO of INNINV recalls:

We know of innovations that will come to [TTO4] — we actually know them before they do — because we also work closely with the scientists all the time. … I knew that the inventors [of the technology behind venture Eta] were taking it to [TTO4], and I said to [TTO4] I will try to get together some more investors to help us and then we will start a company. They then put the invention into the company, and they got part of the company for that. We agreed upon a share, and then I got INNINV and other investors, and we put up [venture Eta].

The second indirect role, ‘rationing decision-making power’ is related to ownership distribution and management. The ownership stake and share administration is critical in ET formation, because it determines the parties that will be involved in strategic decision-making and other actions in the ASO, including, among others, who will join the ET. This distribution may also have implications for the initial strategy of the newly created ventures, as owner-managers are more likely to contribute actively to strategy formulation (Boeker Citation1989) and organizations are more likely to deviate from the initial strategy if managers control ownership at founding (Boeker Citation1989; Useem Citation1984).

Prior to 2003, the inventors in universities and hospitals in the region we studied, except in Hospital2, owned the IPR and hence had decision-making power. However, in Hospital2, researchers were not allowed to own a share in the ventures and hence did not have this power. Furthermore, although they were eligible to receive one third of any revenue generated from the sale of shares, the TTO decided when to sell and how. This practice continued even after the change in legislation in 2003, until researchers were enabled to own their shares in ASOs created out of their inventions in 2011. Besides impacting the financial return that researchers could gain in many ways, including the timing of share sales and how tax is calculated from the proceeds, this question of ownership also affects the dynamics of ASO-ETs and their modus operandi. The differences observed between the ETs behind ventures Gamma and Epsilon demonstrates this.

In venture Gamma, the co-founders recalled that they made all the decisions related to the future of the venture as a team. However, in venture Epsilon, two of the ET members were not allowed to own their own shares and had to be represented by the TTO. This created a situation where technology-related issues were discussed between the co-founders, but anything related to administrative and managerial issues had to be discussed and decided on by one of the co-founders and the TTO. One of the co-founders of venture Epsilon recalls:

The two other co-founders didn’t have the full power of decisions. They had to go via [TTO1] to make decisions for the company. So, it was [TTO1] who decided how to move forward, who was in the board, and so on. All formal decisions related to administrative issues had to be made between me and [TTO1], although, when it comes to technology and such things, I, of course, could talk with the two other founders. Anyway, it works; it seems to work quite okay.

Furthermore, the involvement of the TTO modified the allocation of ownership stock between the co-founders. In venture Gamma, ownership was negotiated between the co-founders themselves, while in venture Epsilon, it became a fixed amount decided by the regulations governing ASOs through the TTO system.

Interestingly, even when they reject the researchers’ initial idea, TTOs seem to play this role if the researcher(s) decide to commercialize it nonetheless through an ASO. According to one of venture Zeta’s co-founders, this is because of a clause in their contract that he and his colleagues question. He said:

They [TTO3] said that they have an exclusive right to either take the idea or abandon the idea. And if they abandon it, it is yours to take. However, if against all odds it should turn out to be a success — so if you by some mysterious way without their help manage to make something out of this — then they still own 50 per cent [of the researchers’ stock] … . They [TTO3] are actually prohibiting alternative commercialization of ideas by having this clause.

Thus, according to the co-founder, if the TTOs allow researchers to take ideas that they have rejected and did not ask for shares in the end, it could encourage more researchers to try to commercialize the ideas themselves. This could lead to the formation of more ASO-ETs.

These cases show that the TTOs imprinted the ETs indirectly through the roles they play in deciding how ownership rights and decision-making powers are distributed in ETs (see ). This can lead to the inclusion/exclusion of some individuals from ETs and the decision-making process, which in turn will have implications for the continued ET formation process, role assignment between the ET members, and positions created in the ASOs.

Direct roles

Direct roles refers to roles played by the TTOs in providing human resources for the ETs, which in turn shapes the course of the ET and the ASO. In this regard, we identify two distinct roles played by the TTOs (see ). They play an ‘active role’ when they assign their own employees to ASO-ETs, either in a leading role or in other full-time/part-time positions. In our cases, prior to 2003, TTO2 played an active role at Hospital2 (e.g. venture Beta). In ventures Alpha and Gamma, however, the researchers took the lead, and hence TTOs did not assign its employees. ASO-ETs started between 2003 and 2011, either had a CEO (e.g. in ventures Delta, Epsilon and Zeta) or other management positions (e.g. in venture Zeta) held by individuals assigned by the TTOs or their subsidiaries. When they do not assign employees, TTOs and/or their subsidiaries play a critical role in finding and assigning member of ASO-ETs. The CEO of INNINV recalls their role in venture Theta:

I told the first CEO of venture Theta from the start: your job is to bring this. I have a plan for three years, that this is your job … When it comes to this phase, I am going to bring in a new CEO and you and this new CEO have to find out whether or not you will still be in the company.

Some of those assigned to the ASO-ETs continued in the spin-offs even after the demise of the support organizations who assigned them (e.g. the Facilitator1 employees stayed in ventures Delta and Zeta). This active role played by the support organizations has continued post-2011, where TTO4 and INNINV employees hold active positions in the ETs behind the ventures they helped to spin-off (e.g. ventures Eta and Theta). This suggests that the TTO involvement in the spin-off process shapes the ASO-ET formation process and composition. Their involvement seems to have implications not only for the composition of the ETs, but also for the positions created in the spin-offs. In most of our cases, those assigned by TTOs and their subsidiaries took a CEO or CFO position in the team.

In addition to the active role they play in assigning their employees to the ETs in ASOs, TTOs and their subsidiaries also play a ‘passive role’ influencing who joins the particular ET in various other ways. We found a range of influences, from suggesting good candidates to merely providing a pool from which ASO-ETs can draw candidates. For example, we found examples of TTO employees who left their positions to join ASO-ETs. A former CEO of TTO3 explained that ‘a number of people that were in the system left to head one of the small companies […] It is a natural way that they would follow a company leaving TTO3’. We observed this in all our cases throughout all periods (e.g. venture Alpha, pre-2003; venture Delta, between 2003 and 2011; and venture Eta, post-2011). Had the TTOs not been there, or had they been organized differently, it might not have been possible for the ASO-ETs to be constituted as they were.

To summarize, our findings suggest that TTOs and how they are organized shape how ASO-ETs are formed. Accordingly, the composition of the ETs and how they were formed reflect who was involved in the ASO creation process and how the TTOs perform their direct and indirect roles. Therefore, we contend that environmental conditions at the time of formation create an imprint on ETs. This indicates that ETs are not only imprinters, but they are also imprinted by the social conditions at the time of forming. Consequently, we suggest that the organizational imprinting process may start during the ET formation process, which precedes the date when the ventures are founded (i.e. registered). Furthermore, we identified four roles played by TTOs in the ASO-ET formation process. This suggests the need to change how we conceive of the role of TTOs in the technology transfer process – from a principal role in transferring technology to ‘a hand on the steering wheel’.

Contextual dynamics and interplay

Our findings also suggest while TTOs and how they are organized affects ASO-ET formation, TTOs themselves are influenced by changes to both the structure of the parent organizations and national regulations (please see ). This resonates with Fini et al. (Citation2017), who suggested that both system and organizational level factors determine the degree to which universities and research institutes commercialize their research. System factors include national laws and regulations governing technology transfer, while organizational level factors are related to, among other elements, the internal organization of the institutes. Based on our findings, we argue that these factors not only influence the level of commercialization of academic research, but also how ETs are formed in ASOs through the TTOs and their organizing. Consequently, we propose that ET formation in ASOs is a process affected by TTOs and how they are organized, which itself is affected by the particular structure and resources of the parent organization as well as systemic level factors, such as rules and regulations on IPR.

We further contend that the ASO-ET formation process may have an effect on the TTOs themselves. When TTOs play their active and passive direct roles, they could lose staff/employees temporarily and/or permanently. When TTO employees are temporarily assigned to ASO-ETs, they will return to the TTOs with more experience and skills in new venture creation. When they quit their TTO position and join the spin-offs permanently, the TTOs have to replace them with someone else. Because of this, both the amount and quality of human capital the TTOs possess could be affected as more ETs are formed to commercialize technology through ASOs. Thus, we argue that the ASO-ET formation process is not only affected by TTOs, but it also affects them by changing the resources they have at their disposal.

Conclusion

In this study, we sought to investigate whether and how TTOs affect ET formation in ASO settings, a topic that the literature has largely overlooked. Drawing on multiple case studies from a single region in Norway where a variety of TTOs were created and re-organized, we found that ASO-ETs did indeed follow different formation paths, partly mirroring the changes in TTOs. We identify both direct and indirect roles of TTOs and how they affect the ASO-ET formation process. Based on organizational imprinting theory (Stinchcombe Citation1965), we interpret this as the social conditions at the time of formation imprinting the composition of ASO-ETs. Our findings reveal that the context in which ETs are formed needs to be considered as more than a backdrop (Gaddefors and Anderson Citation2019), because it explains how the ET formation process unfolds.

Our study makes several unique contributions to different literature streams. First, we contribute to the academic entrepreneurship literature by not only showing a link between TTOs and ETs, but also by revealing how TTOs and their activities affect ASO-ET formation. Second, we contribute to the literature on ET formation by developing a framework showing how TTOs imprint the formation of ASO-ETs and stressing the need to consider contextual factors when investigating ETs and their formation. Our findings suggest that the rational, socio-psychological, or the dual models may not always explain ASO-ET formation, and that scholars must also consider the importance of the specific setting in which ETs are formed. This resonates with the call in the entrepreneurship literature for dynamic and interpretive contextualized views of entrepreneurship (Welter and Gartner Citation2016; Gaddefors and Anderson Citation2017; Anderson and Gaddefors Citation2017). Third, we contribute to organizational imprinting theory by extending it to ETs and discussing how the social conditions at the time of forming may imprint the composition of ASO-ETs. This responds to the call for more research to address ‘how’ imprinting occurs (Simsek, Fox, and Heavey Citation2015). Our findings also have implications for understanding position imprinting in an ASO. The position imprinting literature suggests that positions created at venture founding will have a lasting consequence for the venture, and that the initial incumbent plays a critical role in defining positions in the organizations (Beckman and Burton Citation2008). Extending this view, we suggest that social conditions at the time of the ASO-ETs may influence the positions created in the ventures.

Our study also has both managerial and policy implications. For TTOs and their managers, our findings suggest that they need to pay attention to the way they play their roles in the ASO-ET formation process as it affects not only the composition of the teams but also the dynamics within ASO-ETs. To reduce and avoid any possible strains in the relations between TTOs and researchers as well as between ET members, TTO leaders may need to discuss matters in detail with researchers and team members at each stage of the formation process. Furthermore, the way they play their roles may also affect the career path and choice of the researchers that they are there to help in commercializing their inventions. Thus, TTOs and their managers may need to reflect on how the roles they enact might enable (or hinder) the formation of current and future ET-ASOs. While playing their roles constructively in the ASO-ET formation process, managers of TTOs should also consider both the immediate and future consequences of the ASO-ET formations on the human capital that they will have at their disposal as it can affect the movement of their employees.

From a policy perspective, our findings remind policymakers that any change made to regulations governing TTOs and their technology transfer activities modifies not only whether and how the technology is transferred, but also who is involved in ASO-ETs. This is important on at least two levels. First, at the venture level, it may affect the long-term network and competencies of the spin-offs, which is one factor explaining variations in ASO performance (Rasmussen, Mosey, and Wright Citation2015). The ET is an important resource of ASOs and partly determines the network and competences of the ASOs. Changes in regulations governing technology transfer activities affect the ASO-ET formation process and, by that, who will be involved in the ETs. The composition of the ET in turn affects the network and competences of ASOs. Second, it may also impact the career paths and choices of academic researchers and their involvement in entrepreneurship. For instance, our cases show that some ET members had no plans to start a company or to work in an ASO; they continued along that career path after they were persuaded to join the ETs. This in turn may affect the mobility of labour from academia to entrepreneurship, and vice versa, which again may impact job creation and regional development. Hence, technology transfer leaders and policymakers may need to consider how they engage in the different roles we identified in this study and their potential effect on ASO-ETs when they formulate strategies for technology commercialization.

Although our study offers new insights into the role of TTOs in ASO-ET formation, it has limitations that open avenues for future research. First, to explore our research question in depth, we selected cases from the same region and industry. Further research may explore whether our findings hold both in other countries or regions and in other sectors. Second, though we followed the movement of ASO-ET members assigned by or joining from TTOs and their subsidiaries, we did not study their mindsets, or how they saw themselves during the transition from TTO to ASO. Whether they consider their initial roles as project owner or management team member may influence their involvement in the venture formation process. Future research could address this question and examine whether the ET formation process differs based on how those assigned by TTOs see themselves in the ASOs.Footnote7 Finally, our analysis of social conditions mainly includes support organizations like TTOs, their subsidiaries, (public) institutional investors, and related IPR law. Additional analyses that include other factors, such as the scale of government R&D funding, or the role of other organizations such as research councils, may help to extend the insights presented here. Despite these limitations, the first-hand accounts from life science ventures we documented in this study improve understanding of the roles played by TTOS in ET formation in ASO settings.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2080867

Notes

1. The average number of years that the ASO-ETs took in the formation process (based on our definition) is 8 years and ranges from 5–12 years.

2. The few studies in the literature used markers such as the legal incorporation of the venture (Rasmussen Citation2011), the first sale (Shah, Agarwal, and Echambadi Citation2019), seed funding (Vanaelst et al. Citation2006), or first hire (Matlay and Westhead Citation2005) as markers for the completion of the ET formation (Lazar et al. Citation2020). Because of the lengthy time required to develop a science-based venture, we would argue that none of these markers is appropriate. Entrepreneurial opportunities for ASOs in life sciences evolve long after the legal incorporation of the firm, after receiving the first seed money, or after the first hire (as the new hire could actively participate in developing the entrepreneurial opportunity).

3. See Gulbrandsen and Nerdrum (Citation2007a) and Rasmussen and Rice (Citation2012) for a detailed history of public sector research and different policy initiatives for commercialization in Norway.

4. Please see in the appendix for a summary of the secondary data we collected.

5. Venture Beta was an ASO created out of an invention developed at Hospital2. Although it was not one of the cases that we studied in detail, venture Beta is a crucial venture in the life of TTO2 and venture Gamma. It was formed before venture Gamma, and TTO2 actively took the venture forward. TTO2 invested most of its resources (both human and financial) in venture Beta, which was one of the reasons why TTO2 allowed the researchers behind venture Gamma to take their idea further alone. It is not included in our case list because we had insufficient access to the ET members behind it.

6. We are not suggesting that other alternative commercialization routes (e.g. licencing the patent or other means) must necessarily be classified as ‘negative’ alternatives. We use negative here as a rejection of the creation of an ASO on the particular proposed idea/application, which may in turn indirectly affect ASO-ET formation ‘negatively’ (i.e. the ET will not be created).

7. We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

References

- Albert, L., and D. DeTienne. 2016. “Founding Resources and Intentional Exit Sales Strategies: An Imprinting Perspective.” Group & Organization Management 41 (6): 823–846. doi:10.1177/1059601116668762.

- Aldrich, H., and P. Kim. 2007. “Small Worlds, Infinite Possibilities? How Social Networks Affect Entrepreneurial Team Formation and Search.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1 (1–2): 147–165. doi:10.1002/sej.8.

- Anderson, A., and J. Gaddefors. 2017. “Is Entrepreneurship Research Out of Context? Dilemmas with (Non) Contextualised Views of Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability 13 (4): 3–9.

- Arvanitis, S., U. Kubli, and M. Woerter. 2008. “University-industry Knowledge and Technology Transfer in Switzerland: What University Scientists Think about co-operation with Private Enterprises.” Research Policy 37 (10): 1865–1883. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.07.005.

- Beckman, C. 2006. “The Influence of Founding Team Company Affiliations on Firm Behavior.” Academy of Management Journal 49 (4): 741–758. doi:10.5465/amj.2006.22083030.

- Beckman, C., and D. Burton. 2008. “Founding the Future: Path Dependence in the Evolution of Top Management Teams from Founding to IPO.” Organization Science 19 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0311.

- Ben-Hafaiedh, C. 2010. “Entrepreneurial Team Formation: Any Rationality?” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 30 (10): 1–15.

- Bjørnåli, E., and M. Gulbrandsen. 2010. “Exploring Board Formation and Evolution of Board Composition in Academic spin-offs.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 35 (1): 92–112. doi:10.1007/s10961-009-9115-5.

- Bjørnåli, E., and A. Aspelund. 2012. “The Role of the Entrepreneurial Team and the Board of Directors in the Internationalization of Academic spin-offs.” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 10 (4): 350–377. doi:10.1007/s10843-012-0094-5.

- Boeker, W. 1989. “Strategic Change: The Effects of Founding and History.” Academy of Management Journal 32 (3): 489–515.

- Bryant, P. 2014. “Imprinting by Design: The Microfoundations of Entrepreneurial Adaptation.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38 (5): 1081–1102. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00529.x.

- Burton, D., and C. Beckman. 2007. “Leaving a Legacy: Position Imprints and Successor Turnover in Young Firms.” American Sociological Review 72 (2): 239–266. doi:10.1177/000312240707200206.

- Clarysse, B., and N. Moray. 2004. “A Process Study of Entrepreneurial Team Formation: The Case of A research-based spin-off.” Journal of Business Venturing 19 (1): 55–79. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00113-1.

- Colombo, M., and E. Piva. 2008. “Strengths and Weaknesses of Academic Startups: A Conceptual Model.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 55 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1109/TEM.2007.912807.

- Conceicao, O., M. Fontes, and T. Calapez. 2012. “The Commercialisation Decision of research-based spin-off: Targeting the Market for Technologies.” Technovation 32 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2011.07.009.

- Coupé, T. 2003. “Science Is Golden: Academic R&D and University Patents.” Journal of Technology Transfer 28 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1023/A:1021626702728.

- Debackere, K., and R. Veugelers. 2005. “The Role of Academic Technology Transfer Organizations in Improving Industry Science Links.” Research Policy 34 (3): 321–342. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.12.003.

- Di Gregorio, D., and S. Shane. 2003. “Why Do Some Universities Generate More start-ups than Others?” Research Policy 32 (2): 209–227. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00097-5.

- Diánez-González, J. P., C. Camelo-Ordaz, and J. Ruiz-Navarro. 2016. “Management Teams’ Composition and Academic Spin-Offs’ Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Theoretical Approach.” In Entrepreneurship-Practice-Oriented Perspectives, edited by M. Franco, 65–86. InTechOpen. doi:10.5772/62694.

- Discua Cruz, A., C. Howorth, and E. Hamilton. 2013. “Intrafamily Entrepreneurship: The Formation and Membership of Family Entrepreneurial Teams.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (1): 17–46. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00534.x.

- Dubois, A., and L.-E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: An Abductive Approach to Case Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. doi:10.2307/258557.

- Fini, R., K. Fu, M. T. Mathisen, E. Rasmussen, and M. Wright. 2017. “Institutional Determinants of University spin-off Quantity and Quality: A Longitudinal, Multilevel, cross-country Study.” Small Business Economics 48 (2): 361–391. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9779-9.

- Forbes, D., P. Borchert, M. Zellmer‐Bruhn, and H. Sapienza. 2006. “Entrepreneurial Team Formation: An Exploration of New Member Addition.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00119.x.

- Forsstrom-Tuominen, H., L. Jussila, and S. Goel. 2019. “Reinforcing Collectiveness in Entrepreneurial Interactions within start-up Teams: A multiple-case Study.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 31 (9–10): 683–709. doi:10.1080/08985626.2018.1554709.

- Fryges, H., and M. Wright. 2014. “The Origin of spin-offs: A Typology of Corporate and Academic spin-offs.” Small Business Economics 43 (2): 245–259. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9535-3.

- Gabrielsson, J., H. Landström, and T. Brunsnes. 2006. “A knowledge-based Categorization of research-based spin-off Creation.” CIRCLE Working Paper Series Paper no. 2006/06, Lund University, Lund.

- Gaddefors, J., and A. Anderson. 2017. “Entrepreneurship and Context: When Entrepreneurship Is Greater than Entrepreneurs.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 23 (2): 267–278. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-01-2016-0040.

- Gaddefors, J., and A. Anderson. 2019. “Romancing the Rural: Reconceptualizing Rural Entrepreneurship as Engagement with Context(s).” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 20 (3): 159–169. doi:10.1177/1465750318785545.

- Garrone, P., L. Grilli, and B. Mrkajic. 2018 ”Human capital of entrepreneurial teams in nascent high-tech sectors: a comparison between Cleantech and Internet.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 30 (1): 84–97.

- Grandi, A., and R. Grimaldi. 2003. “Exploring the Networking Characteristics of New Venture Founding Teams: A Study of Italian Academic spin-off.” Small Business Economics 21 (4): 329–341. doi:10.1023/A:1026171206062.

- Grønning, T. 2009. “The Biotechnology Industry in Norway: A Marginal Sector or Future Core Activity?” In Innovation, Path Dependency, and Policy: The Norwegian Case, edited by J. Fagerberg, D. Mowery, and B. Verspagen, 235–263. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gulbrandsen, M., and L. Nerdrum. 2007a. “Public Sector Research and Industrial Innovation in Norway: A Historical Perspective.” Working Paper, University of Oslo.

- Gulbrandsen, M., and L. Nerdrum. 2007b. “University-industry Relations in Norway.” Working Paper, University of Oslo.

- Harper, D. 2008. “Towards a Theory of Entrepreneurial Teams.” Journal of Business Venturing 23 (6): 613–626. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.002.

- Hine, D., and J. Kapeleris. 2006. Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Biotechnology, an International Perspective: Concepts, Theories and Cases. Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hormiga, E., C. Hancock, and N. Jaría. 2017. “Going It Alone or Working as Part of a Team: The Impact of Human Capital on Entrepreneurial Decision Making.” Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business 2 (1): 203–231.

- Huyghe, A., M. Knockaert, M. Wright, and E. Piva. 2014. “Technology Transfer Offices as Boundary Spanners in the pre-spin-off Process: The Case of a Hybrid Model.” Small Business Economics 43 (2): 289–307. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9537-1.

- Huyghe, A., and M. Knockaert. 2015. “The Influence of Organizational Culture and Climate on Entrepreneurial Intentions among Research Scientists.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 40 (1): 138–160. doi:10.1007/s10961-014-9333-3.

- Huynh, T., D. Patton, D. Arias-Aranda, and L. M. Molina-Fernández. 2017. “University spin-off’s Performance: Capabilities and Networks of Founding Teams at Creation Phase.” Journal of Business Research 78: 10–22. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.04.015.

- Johnson, V. 2007. “What Is Organizational Imprinting? Cultural Entrepreneurship in the Founding of the Paris Opera.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (1): 97–127. doi:10.1086/517899.

- Jung, H., B. Vissa, and M. Pich. 2017. “How Do Entrepreneurial Founding Teams Allocate Task Positions?” Academy of Management Journal 60 (1): 264–294. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0813.

- Kamm, J., and A. Nurick. 1993. “The Stages of Team Venture Formation: A decision-making Model.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 17 (2): 17–28.

- Kim, P., and H. Aldrich. 2004. “Teams that Work Together, Stay Together: Resiliency of Entrepreneurial Teams.” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 24: 85–95.

- Knockaert, M., D. Ucbasaran, M. Wright, and B. Clarysse. 2011. “The Relationship between Knowledge Transfer, Top Management Team Composition, and Performance: The Case of Science‐based Entrepreneurial Firms.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (4): 777–803. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00405.x.

- Kolympiris, C., and P. Klein. 2017. “The Effects of Academic Incubators on University Innovation.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 11 (2): 145–170. doi:10.1002/sej.1242.

- Kreiner, K., and J. Mouritsen. 2005. “The Analytical Interview - Relevance beyond Reflexivity.” In The Art of Science, edited by S. Tengblad, R. A. Solli, and B. Czarniawska, 153–176. Malmø: Liber and Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Langley, A. 1999. “Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data.” Academy of Management Review 24 (4): 691–710. doi:10.5465/amr.1999.2553248.

- Lazar, M., E. Miron-Spektor, R. Agarwal, M. Erez, B. Goldfarb, and G. Chen. 2020. “Entrepreneurial Team Formation.” Academy of Management Annals 14 (1): 29–59. doi:10.5465/annals.2017.0131.

- Lee, K., and H. Jung. 2021. “Does TTO Capability Matter in Commercializing University Technology? Evidence from Longitudinal Data in South Korea.” Research Policy 50 (1): 104–133. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2020.104133.

- Link, A., and M. van Hasselt. 2019. “On the Transfer of Technology from Universities: The Impact of the Bayh–Dole Act of 1980 on the Institutionalization of University Research.” European Economic Review 119: 472–481. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.08.006.

- Lundqvist, M. 2014. “The Importance of Surrogate Entrepreneurship for Incubated Swedish Technology Ventures.” Technovation 34 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2013.08.005.

- Majumdar, M., and V. Kiran. 2012. “Imbibing Social Entrepreneurship in Biotechnology.” Business Systems Review 1 (1): 27–38.

- Marquis, C., and A. Tilcsik. 2013. “Imprinting: Toward a Multilevel Theory.” Academy of Management Annals 7 (1): 195–245. doi:10.5465/19416520.2013.766076.

- Mathias, B., D. Williams, and A. Smith. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Inception: The Role of Imprinting in Entrepreneurial Action.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.004.

- Mathisen, M., and E. Rasmussen. 2019. “The Development, Growth, and Performance of University spin-offs: A Critical Review.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 44 (6): 1891–1938. doi:10.1007/s10961-018-09714-9.

- Matlay, H., and P. Westhead. 2005. “Virtual Teams and the Rise of e-entrepreneurship in Europe.” International Small Business Journal 23 (3): 279–302. doi:10.1177/0266242605052074.

- McAdam, M., and R. McAdam. 2008. “High Tech start-ups in University Science Park Incubators: The Relationship between the start-up’s Lifecycle Progression and Use of the Incubator’s Resources.” Technovation 28 (5): 277–290. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2007.07.012.

- Micozzi, A., D. Iacobucci, I. Martelli, and A. Piccaluga. 2021. “Engines Need Transmission Belts: The Importance of People in Technology Transfer Offices.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 46 (5): 1551–1583. doi:10.1007/s10961-021-09844-7.

- Moray, N., and B. Clarysse. 2005. “Institutional Change and Resource Endowments to science-based Entrepreneurial Firms.” Research Policy 34 (7): 1010–1027. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.016.

- Müller, B. 2006. “Human Capital and Successful Academic spin-off.” ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper, (06–081).

- Muñoz-Bullón, F., M. Sanchez-Bueno, and A. Vos-Saz. 2015. “Startup Team Contributions and New Firm Creation: The Role of Founding Team Experience.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24 (1–2): 80–105. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.999719.

- Mustar, P., M. Renault, M. Colombo, E. Piva, M. Fontes, A. Lockett, M. Wright, B. Clarysse, and N. Moray. 2006. “Conceptualising the Heterogeneity of research-based spin-offs: A multi-dimensional Taxonomy.” Research Policy 35 (2): 289–308. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.11.001.

- Nikiforou, A., M. Gruber, T. Zabara, and B. Clarysse. 2018. “The Role of Teams in Academic spin-offs.” Academy of Management Perspectives 32 (1): 78–103. doi:10.5465/amp.2016.0148.

- O’Kane, C., J. Cunningham, M. Menter, and S. Walton. 2020. “The Brokering Role of Technology Transfer Offices within Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: An Investigation of macro–meso–micro Factors.” The Journal of Technology Transfer. doi:10.1007/s10961-020-09829-y.

- Oliver, A. L. 2004. “Biotechnology Entrepreneurial Scientists and Their Collaborations.” Research Policy 33 (4): 583–597. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.010.

- Owen-Smith, J., and W. Powell. 2004. “Knowledge Networks as Channels and Conduits: The Effects of Spillovers in the Boston Biotechnology Community.” Organization Science 15 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1287/orsc.1030.0054.

- Packalen, K. 2015. “Multiple Successful Models: How Demographic Features of Founding Teams Differ between Regions and over Time.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27 (5–6): 357–385. doi:10.1080/08985626.2015.1059896.

- Politis, D., J. Gabrielsson, and O. Shveykina. 2012. “Early-stage Finance and the Role of External Entrepreneurs in the Commercialization of university-generated Knowledge.” Venture Capital 14 (2–3): 175–198. doi:10.1080/13691066.2012.667905.

- Rasmussen, E., and O. J. Borch. 2010. “University Capabilities in Facilitating Entrepreneurship: A Longitudinal Study of spin-off Ventures at mid-range Universities.” Research Policy 39 (5): 602–612. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.02.002.

- Rasmussen, E. 2011. “Understanding Academic Entrepreneurship: Exploring the Emergence of University Spinoff Ventures Using Process Theories.” International Small Business Journal 29 (5): 448–471. doi:10.1177/0266242610385395.

- Rasmussen, E., and M. P. Rice. 2012. “A Framework for Government Support Mechanisms Aimed at Enhancing University Technology Transfer: The Norwegian Case.” International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialisation 11 (1–2): 1–25. doi:10.1504/IJTTC.2012.043934.

- Rasmussen, E., and M. Wright. 2015. “How Can Universities Facilitate Academic spin-offs? An Entrepreneurial Competency Perspective.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 40 (5): 782–799. doi:10.1007/s10961-014-9386-3.

- Rasmussen, E., S. Mosey, and M. Wright. 2015. “The Transformation of Network Ties to Develop Entrepreneurial Competencies for University spin-offs.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27 (7–8): 430–457. doi:10.1080/08985626.2015.1070536.

- Rihoux, B., and C. Ragin, Eds. 2009. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- Ruef, M., H. Aldrich, and N. Carter. 2003. “The Structure of Founding Teams: Homophily, Strong Ties, and Isolation among US Entrepreneurs.” American Sociological Review 68 (2): 195–222. doi:10.2307/1519766.

- Ruef, M. 2010. The Entrepreneurial Group: Social Identities, Relations, and Collective Action. Princeton: NJ, Princeton University Press.