ABSTRACT

We explore the experiences of LGBT* ethnic minority entrepreneurs, their changing locations and their entrepreneurial activities. Using a unique mixed-method approach which collected empirical data from Germany and the Netherlands, the paper combines an ethnographic fieldwork of intersectional entrepreneurs, community activists and policy-makers with an original survey with LGBT* customers. Our findings contribute to understanding of intersectionality by revealing the role played by the contextualized embeddedness of intersectional entrepreneurs at the different geographic scales of supranational, national, regional and inter and intra-urban. While such embeddedness frames the challenges they face, it also provides opportunities for intersectional entrepreneurs. Using a multi-scalar perspective, this paper delivers a spatially contextual perspective of entrepreneurial diversity and provides a framework to analyse the complex issues and contexts with which intersectional entrepreneurs are both confronted and embedded within. This paper contributes to refining the spatial context of entrepreneurship which has gained attention in recent studies of entrepreneurship and regional development. The paper responds to a call for gender entrepreneurship scholars to contribute to understanding of intersectional entrepreneurship. Finally, this study goes beyond the binary view of female migrant entrepreneurship by adopting a more gender diverse lens which considers the experiences of LGBT* entrepreneurs from ethnic minorities.

Introduction

Contemporary societies are increasingly more diverse due to changes in migration patterns and transnational flows of people, capital and ideas. In the context of such ‘superdiversity’ (Vertovec Citation2007), there has been a scholarly call for a wider consideration of other dimensions of diversity in society (Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2021), including ethnicity, race, (dis)ability, religion and gender. Entrepreneurship research has responded, by a growing interest in the intersectionality of entrepreneurs and the impact of this on their experiences of business ownership (Essers, Verduyn, and Kacar Citation2020; Lassalle and Shaw Citation2021; Scott and Hussain Citation2019). Such studies are challenging both ethno-focal perspectives on migration (Glick-Schiller, Çaglar, and Guldbrandsen Citation2006) and assumptions of post-feminism in women entrepreneurship research (Ahl and Marlow Citation2019). In their call to rethink gender approaches to entrepreneurship, Marlow, Greene, and Coad (Citation2018) urge researchers to replace a focus on gender binaries with consideration of the experiences of sexualized or gendered others (Bruni, Gherardi, and Poggio Citation2004).Footnote1 Gender and sexual minoritiesFootnote2 face discrimination in their socialization, and in their economic activities and scholars and policy-makers are interested in better understanding the impact of these discriminations and in achieving equality in society. Individuals situated at the intersection of different structures of oppression suffer from specific discriminations which lead to discriminations and exclusion (Bowleg Citation2008). We propose to explore the experiences of intersectional entrepreneurs – that is entrepreneurs experiencing the intersectional disadvantages of being ethnic gender and sexual minorities – in Germany and the Netherlands.

Understanding that entrepreneurship is impacted by the context in which entrepreneurs and their firms are embedded has become a viable modus operandi in entrepreneurship research (Jack and Anderson Citation2002; Welter Citation2011; Zahra, Wright, and Abdelgawad Citation2014), and scholars have become interested in the growing complexity of factors, actors and practices of entrepreneurship (McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014). By analysing entrepreneurs’ historical, institutional, social and spatial contexts, a richer understanding of their opportunities and boundaries can be acquired (Welter Citation2011). Particularly, the importance of the spatial context of entrepreneurship has received growing attention. For example, migrant entrepreneurship research which has drawn on the mixed embeddedness perspective (Kloosterman and Rath Citation2001; Kloosterman, Van Der Leun, and Rath Citation1999) is a growing research topic as is research emphasizing the urban lens as the preferable unit of analysis (Bosma and Sternberg Citation2014; Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011). Yet, the debate on the spatial aspect of entrepreneurial context has only recently found attention in entrepreneurship and regional development research (McKeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015; Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018). As such, it offers a rich avenue for the study of diversity in entrepreneurship. As Trettin and Welter (Citation2011, 575) point out, ‘entrepreneur’s socio-spatial contexts in which they operate on a daily basis are still absent from much of the entrepreneurship debate’. Following their call to consider the impact of spatial context, this paper delivers a refinement of the spatially contextual embedding of intersectional entrepreneurship. We define entrepreneurs at the intersection of migrant entrepreneurship and gender minority entrepreneurship as ‘intersectional entrepreneurs’. The designation of intersectional entrepreneurs hints not only at the multiple embeddedness of these specific entrepreneurs in minority communities but also at the obstacles and disadvantages they often encounter as multiple minorities.Footnote3 Building on research on contextual embeddedness (Kloosterman Citation2010; Welter Citation2011), this paper analyses the spatial contextualization of intersectional entrepreneurs from a multi-scalar perspective (Brenner Citation2001), which involves analysing their context at national, regional and urban levels.

By using a contextual entrepreneurship lens, we demonstrate how issues of unequal access to resources and markets for particularly intersectional entrepreneurs are inherently connected to their spatial contextual embedding. As our findings show, the nature of entrepreneurial diversity can only be fully captured and analysed against the background of each scale of spatial context and administrative governance (Affolderbach and Carr Citation2016; Brenner Citation2001), in which intersectional entrepreneurs are distinctly embedded. We thus propose a multi-scalar research approach to entrepreneurial contexts. Such spatially contextual embedding across these scales is crucial for research on intersectional entrepreneurs (as in the presented case) and has the potential to be incorporated into the analysis of enterprise by any kind of diverse minorities in future research.

While demonstrating the importance of spatial context, this paper takes intersectional entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs who identify as LGBT*Footnote4 and simultaneously are ethnic minorities, as the contextual example. By going beyond the common male-female binary of female migrant entrepreneurship studies, and taking a more sexual and gender diverse approach, we also contribute to broadening the understanding of intersectional entrepreneurship.Footnote5 We thus follow Marlow and Martinez Dy’s call (Citation2018) to consider intersectional approaches more fully in entrepreneurship research and acknowledge that the diversity of gender and sexual identities has become part of the social diversification observed in society and also the field of entrepreneurship. As this paper shows, the multi-scalar approach to spatially contextual embedding contributes to achieving deeper understanding and insights into the complex issues experienced by intersectional entrepreneurship and is a viable concept to inform future studies of minority entrepreneurship more generally.

After presenting and discussing the theoretical framing of spatial contexts and intersectionality in entrepreneurship, this paper discusses specific methodological challenges involved when researching gender minorities before introducing the original fieldwork. Findings are then discussed according to the different scales of contextual embeddedness, through which to explore intersectionality in entrepreneurship. The paper concludes with a call for further exploration of the dimensions of diversity in entrepreneurial practices by adopting a multi-scalar approach to spatially contextual embedding of entrepreneurship.

Theoretical framing

Spatial contexts in entrepreneurship

Although the spatial context has been identified to be highly relevant for entrepreneurship, its study constitutes a challenge for researchers, especially for capturing ‘everyday’ entrepreneurship (Trettin and Welter Citation2011; Welter et al. Citation2017). Spatiality is not only crucial in the sense of locational choice and access to markets but also in the context of accessibility to relevant resources that enable entrepreneurial activities (Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018). Entrepreneurs are embedded in interwoven networks of social ties and institutions, and their entrepreneurial ventures are also strongly influenced by market and resource availability (McKeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015). Each of these aspects is localized and spatially contextualized. Furthermore, the relativity of acquired and ascribed attributes of entrepreneurs becoming advantageous or disadvantageous depend on the spatial context in which individual entrepreneurs are located and embedded: female rural entrepreneurship has, for example, identified that gender in rural context reveals specific features, especially in the male-dominated agriculture sector (Fitz-Koch et al. Citation2018), which, amongst others, limits the scale of women’s entrepreneurial projects (Bock Citation2004). Likewise, in urban contexts, ethnic minority entrepreneurs have been observed to spatially concentrate in specific areas within cities, drawing advantages from such co-location, including in terms of access to niche community markets (Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011; Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2019; Zhou Citation2004).

In entrepreneurship research, spatial contexts as depicted by Trettin and Welter (Citation2011), Welter (Citation2011) and McKeever, Jack, and Anderson (Citation2015) and by the mixed embeddedness perspective initially developed by Kloosterman, Van Der Leun, and Rath (Citation1999) research on ethnic minority entrepreneurship provide a framework for our proposed multi-scalar spatial contextual embeddedness. Both approaches give ground to explore different contexts at different levels of analysis in entrepreneurship. While the context of entrepreneurship is explicit in the spatial studies across geographical scales (cf. Trettin and Welter Citation2011), the spatial aspect of mixed-embeddedness, which focuses on ethnic minority entrepreneurship, is more implicit. Mixed-embeddedness proposes to analyse minority or migrant entrepreneurship in the different social and institutional contexts in which they operate, which are located at different levels of analysis (Jones et al. Citation2014; Kloosterman Citation2010; Lassalle and McElwee Citation2016; Wang Citation2013).

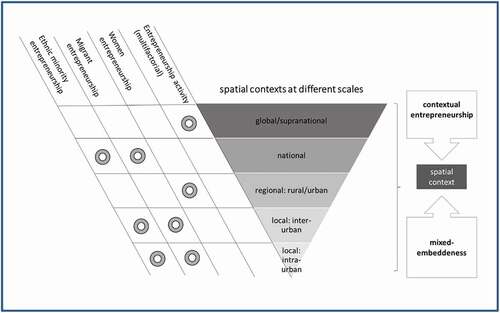

To fully appreciate the diversity of contexts in which entrepreneurs are embedded, it is crucial to consider entrepreneurship at different spatial contextual levels (Welter, Brush, and De Bruin Citation2014). Entrepreneurs’ activities and their challenges are analysed at different geographical scales (cf. Brenner Citation1998, Citation2001). We summarize these strands on the left side of , providing some examples of key references for each level of analysis of minority issues in entrepreneurship research both in terms of gender and ethnic minority.

First, minority, gender and inequalities in entrepreneurship are analysed at the supranational or international level. One crucial reason for this focus on the supranational or international level is the availability of aggregate data at national levels, which can then be compared across national contexts (OECD, GEM, European Commission, etc.). In this strand of research, minority factors, including gender and nationality, are considered alongside other variables when measuring the entrepreneurial activities of these disadvantaged populations. On the basis of such data, international organizations can compare, for example, entrepreneurship and self-employment rates between female and male, their entrepreneurial motivations or growth aspirations internationally (Levie et al. Citation2014; Simmons et al. Citation2019) and recommend policy measures to support, for example, female entrepreneurs (OECD Citation2017, Citation2018). In the case of gender differences, the international level is also considered by organizations, including the OECD, to provide cross-country analysis (OECD Citation2017). Research-based GEM data (Levie and Hart Citation2011; Simmons et al. Citation2019) or those based on national systems of entrepreneurship (Ács, Autio, and Szerb Citation2014) also build on international comparisons to analyse the performance of different environments for gender equality.

At the national level, as displayed in , studies of minority entrepreneurship focus on the barriers faced by women or minority entrepreneurs, including in terms of access to finance and relevant networks (Brush et al. Citation2018; Carter et al. Citation2015; Deakins et al. Citation2009; Hopp and Martin Citation2017; Ram et al. Citation2013). These studies focus on the nexus between research and policy (Jones et al. Citation2014) and explore national policy support, including for categorizing and supporting female or ethnic minority entrepreneurs (e.g. Högberg et al. Citation2016; Scott and Hussain Citation2019) in relation to broader institutional contextual conditions in which entrepreneurs are embedded (Engelen Citation2006; Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah Citation2016) and which affects them (Hagos, Izak, and Scott Citation2019). These studies challenge the more dominant ‘white male’ assumption in entrepreneurship research (Verduijn and Essers Citation2013) by placing more emphasis on less visible communities in policy-making.

Focusing on female entrepreneurs and on gender inequalities, many studies at the national level emphasize the role played by socio-cultural factors which can both enable and constrain women entrepreneur engagement in high growth (Brush et al. Citation2018; Bullough et al. Citation2019; Carter et al. Citation2003; Neergaard, Shaw, and Carter Citation2005). Among these factors, cultural values, including choice of disciplines in higher education, family traditions and childcare, reinforce institutional factors, while different networking practices among women entrepreneurs can impact on their access to finance for growth (Brush et al. Citation2018; Jennings and Brush Citation2013; Welter, Brush, and De Bruin Citation2014). Likewise, studies of ethnic minority and migrant entrepreneurs at the national level show the difficulty such entrepreneurs have in engaging in high growth ventures due to discriminatory practices related to funding, a lack of awareness of existing support and a scarcity of visible role models (Carter et al. Citation2015; Mwaura et al. Citation2018; Scott and Hussain Citation2019). More specifically, when looking at multiple identities, such as women migrant entrepreneurs (Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Lassalle and Shaw Citation2021), research has revealed differences between socio-cultural national contexts (Al-Dajani et al. Citation2019; Chasserio, Pailot, and Poroli Citation2014; Galloway, Brown, and Arenius Citation2002).

We identify that studies which contextualize gender and minority issues in entrepreneurship at the regional level are typically concerned with networks, innovation systems and rural entrepreneurship (Huggins, Waite, and Munday Citation2018; McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014; Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018; Sternberg Citation2009). Studies of rural entrepreneurship, for example, have conceptualized the ‘rural’ as the context itself in a geographical sense of ‘place’ and ‘periphery’ (Korsgaard, Müller, and Tanvig Citation2015; McKeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015; Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018; Muñoz and Kimmitt Citation2019). However, studies of women and ethnic minority entrepreneurship have rarely considered the regional level for the analysis of challenges, barriers and opportunities faced by these entrepreneurs. Some notable exceptions are the consideration of specific situational and gendered barriers faced by women entrepreneurs in rural contexts in terms of access to relevant social capital and markets, and the impact on their coping strategies (Bock Citation2004; Poon, Thai, and Naybor Citation2012). These studies have also focused on the different household, social and geographical contexts that women entrepreneur experience in rural areas (Alsos, Carter, and Ljunggren Citation2011; Fitz-Koch et al. Citation2018). Ethnic minority entrepreneurs also experience specific challenges in rural contexts, with limited opportunities and experience of discrimination (Ishaq, Hussain, and Whittam Citation2010). Ethnic minority entrepreneurs, who often target their ethnic community as their primary market, need to engage in diversification and ‘middleman’ activities (Lassalle and Scott Citation2018; Zhou Citation2004) due to the limited size and reach of their potential market.

Research on ethnic minority entrepreneurship often adopts an urban context as the spatial unit of analysis through which to explore the experiences and challenges of specific ethnic populations of entrepreneurs in specific urban contexts (Ram et al. Citation2002; Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011; Vershinina, Barrett, and Meyer Citation2011). The urban level is the context in which many ethnic minority entrepreneurs operate and identify their opportunity (Lassalle and McElwee Citation2016; Storti Citation2014). These studies pay particular attention to the ethnic market in urban settings including Ram et al. (Citation2002), Rusinovic (Citation2006) or Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon (Citation2011). Recent developments of migrant entrepreneurship research with a focus on transnationality also explore the specific experience of migrants from specific ethnic origins in selected cities, such as Amsterdam, Milan, London or Birmingham (Solano Citation2019; Vershinina et al. Citation2019). Other comparative studies look at the inter-urban level and analyse differences in diversity in entrepreneurship across different urban contexts. These studies show the impact of entrepreneurial diversity on performance and market developments (Baycan-Levent and Nijkamp Citation2009; Nathan Citation2016). Yet, apart from studies by Zhou and Logan (Citation1989) focusing on the bounded enclave, or Werbner (Citation2001) – in her critique of the concept – the spatial lens is generally not accounted for as a contextual factor impacting on entrepreneurial activity in terms of specific municipal policies and conditions.

Finally, analysing the literature on minority entrepreneurs, we distinguish another level of analysis, which is within the city, where research is focused on capturing and measuring differences in diversity at the local level of the street and neighbourhood (Hall Citation2011; Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2019). Such analyses reveal non-negligible differences in the entrepreneurial environments for minority entrepreneurs within cities. Specific areas within the city are more diverse than others, meaning that favourable entrepreneurial environments for minority entrepreneurs are distributed unequally across cities, where diversity provides niche markets for local minority entrepreneurs (Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2019).

While most research has focused on specific spatial contexts, we borrow from Trettin and Welter (Citation2011) review which proposed a multi-scalar approach for the analysis of entrepreneurship. Taking intersectional entrepreneurs as an example, we demonstrate how minority entrepreneurs are embedded simultaneously in different spatial contexts across geographical scales, illustrating the complexity of specific challenges faced by minority entrepreneurs at different levels (Welter, Brush, and De Bruin Citation2014). Intersectional entrepreneurs are a subgroup of much debated ethnic minority as well as increasingly discussed gender minority entrepreneurs, reflecting the growing diversity in contemporary societies. This study thus conceptually refines the idea of the spatial context by combining learnings from both contextual entrepreneurship and mixed embeddedness.

Intersectionality in entrepreneurship

With a growing awareness and acceptance of diversity in gender and sexual identities in societies,Footnote6 the market for gender diverse services and products is growing, as can be seen in LGBT tourism (UNWTO Citation2017), gastronomy, and accommodation (Campbell Citation2015; Sender Citation2018). Such trends are also observed in different markets in the service sector, such as legal and medical services focused on sexual and gender minority issues, or in the development of specific health and leisure products, such as accessories, sex toys or clothes (c.f.: Statista Citation2020, on the global development of the sex toy industry). The LGBT* community is, like other communities,Footnote7 for example ethnic communities, a specific market niche in which specific entrepreneurial strategies evolve and opportunities are identified and enacted (Drucker Citation2011; Gorman-Murray and Nash Citation2017; Oakenfull Citation2018). LGBT* entrepreneurs, however, face different challenges than female entrepreneurs or their mainstream peers (Germon et al. Citation2020; Rumens and Ozturk Citation2019). Moreover, if combined with further attributes of minority, such as ethnic or religious minority, the constellation of chances and challenges for their entrepreneurial activities becomes even more complex – creating a phenomenon of multiple interwoven discrimination and disadvantages faced by intersectional persons in a masculinized entrepreneurship world (Al-Dajani et al. Citation2019).

Recognizing that growing diversity is present in many contemporary societies, entrepreneurship scholars have begun considering issues including intersectionality (Ahl and Marlow Citation2011; Lassalle and Shaw Citation2021; Martinez Dy, Marlow, and Martin Citation2016; Martinez Dy, Martin, and Marlow Citation2014). The multiple entangled disadvantages that intersectional individuals face have become a growing area of policy and research interest (Ahl and Marlow Citation2012; Valdez Citation2016; Wingfield and Taylor Citation2016). In contrast to intersectionality debates within gender studies and sociology (McCall Citation2005; Meyer and Northridge Citation2007), the prime focus of entrepreneurship research on intersectionality has been on gender with ethnic minority or migrant backgrounds (Al-Dajani and Marlow Citation2013; Lassalle and Shaw Citation2021; Levie and Hart Citation2011; Lewis Citation2006). Despite market research on LGBT* consumers, in the hospitality sector (Lugosi Citation2007), the entrepreneurship literature has continued to adopt a largely female-male binary perspective (Marlow and Martinez Dy Citation2018). Similarly, research on gender minorities with respect to LGBT* and in entrepreneurship remains very scarce (Germon et al. Citation2020; Redien-Collot Citation2012). The multi-dimensional challenges that intersectional entrepreneurs face need more consideration, in particular, for entrepreneurs from LGBT* ethnic minorities. Indeed, as highlighted by Ghabrial (Citation2017), when exploring issues faced by LGBT* persons of colour, as called for by Marlow, Greene, and Coad (Citation2018), there is an urge to also address this gap from an academic and also equality agenda in entrepreneurship studies. Confronted with the complexity of intersectional issues, policy-makers do not always account for the specific issues faced by intersectional individuals, be it in law, health or in the economic spheres (Crenshaw Citation1991), thus ‘invisibilising’ specific populations in their actions at different administrative levels, which is why research is particularly required.

As depicted in , the focus of this study is on intersectional entrepreneurs, defined as individuals who are both LGBT* gender and/or sexual minorities as well as ethnic minorities or migrants. Although individuals, including entrepreneurs, naturally feature further attributes, such as age and generations, linguistic or religious characteristics (Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2021), the focus on these two is the most relevant and crucial as policies on minority entrepreneurship tend to focus on either ethnic minorities and migrants or gender minorities. Policies on religious minority or age-related entrepreneurs are rather uncommon but could become more important in the context of, for example, the post-growth ageing societies in future.

Methods: researching intersectional entrepreneurship

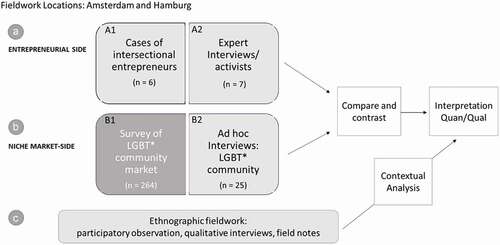

One crucial reason for the lack of research on LGBT* intersectional entrepreneurs is the sensitive nature of sexual orientation and gender identities (SOGI). This includes difficulties in identifying and accessing such a sensitive and often (physically and institutionally) invisible and vulnerable population (Browne Citation2006). LGBT* participants are difficult to identify as not every entrepreneur displays their SOGI nor uses this characteristic for business purposes, making the field highly difficult to access and observe. Categorizing respondents a priori according to their SOGI attribute would result in ‘outing’ individuals. Overall, researching sexual and gender minority populations requires specific ethical considerations – shared by intersectionality researchers (Staunæs Citation2003). These particular considerations of identification, sampling, fieldwork access, data usage and anonymizationFootnote8 are crucial for investigating gender minorities and intersectionality in entrepreneurship. This inevitably results in specific choices and limitations and emphasizes the relevance of conducting qualitative, exploratory and ethnographic fieldwork to capture an encompassing picture of intersectional entrepreneurs. Due to the challenges, our empirical study used a triangulation design, specifically the convergence model recommended by Creswell and Clark (Citation2007). By comparing and contrasting results from mixed qualitative research (expert and qualitative interviews) on the entrepreneurial side with quantitative survey results (with ad hoc interviews) on the niche-market side, we interpret these data as a triangulation of the intersectional entrepreneurial field. Moreover, the interpretation of both data is complemented and contextualized additionally by ethnographic fieldworks (see ).

Data collection: intersectional entrepreneurs in Hamburg and Amsterdam

Fieldwork was conducted primarily in Hamburg (Germany) and Amsterdam (The Netherlands), with further narratives on experiences in other cities. We specifically selected these cities as they are well-established hubs for LGBT*culture and explicitly engage in municipal support for their sexual and gender minority citizens as part of the Rainbow Cities Network (see also the ‘Pink Agenda’ of Amsterdam City Council’s diversity policy). In these contexts, we also conducted an ethnographic assessment of the different locations within the selected cities at the district level, an approach that has recently been addressed in research specifically on superdiversity and entrepreneurship (Hall Citation2011; Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2019). This approach allows an adequate assessment of the spatial context in which entrepreneurs operate, including their entrepreneurial landscapes, their customers and the socio-spatial diversity of the area.

Interviews

This paper primarily builds on original qualitative fieldwork conducted amongst intersectional entrepreneurs, who present different attributes of sexual and gender minority, ethnicity and migration background. On the entrepreneurial side (A in ), the fieldwork encompasses six cases with LGBT* intersectional entrepreneurs (A1 in and )Footnote9 and 7 interviews with relevant experts of intersectionality, conducted with LGBT* community activists and government officials with strong involvement in supporting diversity and intersectionality in entrepreneurship (A2 in , and ). Cases were developed with intersectional entrepreneurs. As discussed, due to the sensitive nature, some of the discussions were conducted as informal discussions and were neither recorded nor transcribed to create a ‘safe(r) space’ for the interviewees. Consistent with this approach, notes of discussions, along with those from ethnographic assessment and participatory observations, were collected (C, see more below on the ethnographic fieldwork). Topics covered life experiences, migration decision and locational choices, as well as socialization issues, along with entrepreneurial activities, providing rare insights into the experiences of intersectional entrepreneurs regarding mobility, entrepreneurship and everyday life in different spatial contexts.

Table 1. Intersectional entrepreneurs.

Table 2. Intersectionality experts.

Looking at the demand-side: spatial contexts and niche market

To explore customers’ perspectives of the LGBT* niche market, we also conducted a survey of the demand-side (B1 in ). As many minority entrepreneurs engage primarily with niche community markets (Jones et al. Citation2014; Lassalle and Scott Citation2018), the importance of the opportunity structure is a critical point to consider when researching entrepreneurial activity (Essers, Verduyn, and Kacar Citation2020). Within LGBT* research, there is very little work on customers. While there are some marketing studies on LGBT* markets (Baker Citation2012; Campbell Citation2015; Lugosi Citation2007; Sender Citation2018) and global industry reports are available (ILGTA, Citation2017; WTM, Citation2015), most focus is on the LGBT* tourism and hospitality industries. We found only one study that considers the spatial context of LGBT* markets and customer behaviours (Gorman-Murray and Nash Citation2017). We conducted a survey of the LGBT* market in Amsterdam and Hamburg focusing on consumer preferences and behaviours with regard to LGBT* businesses and services. We collected 264 usable responses, which constitutes an exceptional sample in the case of LGBT* customers’ population. These original data provide novel descriptive accounts of the opportunity structures in which intersectional entrepreneurs operate. During these surveys, ad hoc interviews were carried out with some of the LGBTI* community respondents (n = 25), these informal interviews were considered when contextually analysing data from our ethnographic fieldwork. Their qualitative perspectives on the issues of the LGBT* community and its market were complementary to the survey.

Ethnographic data

Finally, we conducted ethnographic fieldwork in the different spatial contexts in which intersectional entrepreneurs operate. Additional data accessed during this fieldwork include fieldnotes from observation and participatory observations at important events (C in ). The researcher team also conducted participatory observation at social and political events (Berg and Sigona Citation2013), including – but not limited to – open events such as gay pride marches and festivals, as well as participation and organization of community-driven and government-run equality and diversity events. In such settings, we were actively involved in discussions including at times, chairing and conveying roundtable discussions on inclusivity with business support organizations. The latter were organized by policy-makers in the different locations in which this research took place, involving a range of stakeholders from different gender and ethnic minority communities. Reflective notes from these events were useful to develop a stronger understanding of the issues surrounding policy-making on diversity and entrepreneurship.

Data analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed in different ways. The qualitative data from interviews and the ethnographic fieldwork were analysed using inductive techniques to allow findings to emerge from the different interviews with intersectional entrepreneurs, experts and community members as well as from field notes collected during the fieldworks in each location. The researchers coded the data manually and independently and then compared their interpretations through an inductive process of discovery (Klag and Langley Citation2013; Leitch, Hill, and Harrison Citation2010). Different thematic issues emerged including migration issues, entrepreneurial support, access to customers and societal biases which were then categorized into the different scalar contexts for multi-scalar analysis.

In parallel, for the survey, the respondents were approached face-to-face during the aforementioned events; yet to allow anonymity and privacy, the surveys were conducted digitally on tablets with multilingual questionnaires comprising closed, semi- and open questions created with LimeSurvey (direct questions or discussions with researchers occurred upon request by respondents). These digitally collected survey results were analysed with SPSS to generate descriptive statistics presented below. The combination of qualitative data and descriptive statistics allowed an encompassing understanding of the contextual aspects surrounding the experience of intersectional entrepreneurs (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). In the absence of prior research and reliable statistics on the topic, the use of primary data from different sources was the most suitable research approach. Findings from the qualitative and quantitative fieldworks were then triangulated to inform the analysis (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2011).

Findings: intersecting where?

Various disciplinary themes within entrepreneurship research on minority populations have encouraged a diverse range of spatial units of analysis. The multi-scalar approach to researching entrepreneurship proposed in this paper also adheres to the practical approach to policy-informing research. The relevance of entrepreneurship research for policy-makers and practitioners lies in providing a better understanding of entrepreneurial activities (Ram et al. Citation2013). We found that the motivations, support and barriers that intersectional entrepreneurs are confronted with occur in different spatial contexts, and relevant policies are adapted and implemented also at different geographical, administrative, and political scales. To emphasize but also clarify the complex multi-scalar embeddedness of diversity and intersectionality issues in entrepreneurial activities and environments, the following section presents empirical evidence on the spatially contextual embeddedness of intersectional entrepreneurship across different geographical scales. Based on findings about the multidimensional spatial contextual embeddedness of challenges faced by intersectional entrepreneurs, this paper proposes to explore intersectional issues in entrepreneurship at the national and supranational, regional (rural/urban), inter-urban and intra-urban levels. We discuss this approach by relating our findings to current debates on intersectionality in entrepreneurship.

National & supranational level

Our interviews with intersectional entrepreneurs, government experts and activities confirm that inequalities of gender, ethnic minority and migration are tackled by national-level policy measures both in Germany and the Netherlands. Both activists and experts mentioned that the actions of national governments and governmental agencies regarding gender minority entrepreneurship are part of a wider equality agenda pursued by national-level governments, especially in the Dutch context (e.g. the Netherlands’ Gender & LGBTI Equality Policy Plan). Responses to in-/equality issues in entrepreneurship are typically twofold in these two countries: encouraging and supporting female entrepreneurship, on the one hand, and supporting ethnic minority or migrant entrepreneurship on the other. Whilst those initiatives are currently independently conducted, our participants considered that these should be part of a broader intersectional agenda beyond binary gender issues and include sexual minorities, too, as observed in different events. In Germany, different federal government initiatives support migrants (specifically) to engage in entrepreneurship (e.g. ‘Wir gründen in Deutschland’). The programme is available in various languages and offers comprehensive guidance to migrants looking to start-up in the country. Government agencies in Germany also propose different forms of support (e.g. legal support) to different types of migrants. The mindset among government, the national-level expert accounted,

“is to move from perceiving migrants as Gastarbeiter (guest workers) to recognizing their skills and knowledge that they bring to the country as valuable and respected human resources, including, of course, also migrant entrepreneurs” (Policy-maker C).

Such a national-level shift in regarding migrants and refugees as economically vibrant entrepreneurs is reflected in initiatives targeting refugee entrepreneurship, as in the Netherlands (cf. ‘Startup without Borders’). In general, the vision of government support agencies is both to nurture an inclusive society and sustainable economic growth, through the entrepreneurial activity of different populations. The adoption of a more diversity-oriented approach, at least regarding migrant population, can also be observed with German governmental agencies as stated above, where the information on the platform for migrant entrepreneurs is not only offered in various languages but also categorized according to different migrant (legal) statuses and qualifications (skills).

Likewise, there is an increasingly strong agenda amongst both Dutch and German national governments to support LGBT* individuals from an intersectional perspective and to support the diversity of ‘gender identities, sexual orientations, and sex characteristics with disability, ethnicity, and faith’ (Policy Maker B).

New guidelines and changes in asylum policies concerning LGBT* asylum-seekers are an example of such a national-level change in mindset. Intersectionality and equality policies depend on the political willingness of national governments to foster and encourage diversity in their society. Likewise, migration policies, which are key factors of enabling migration and labour market integration, thus contributing to a favourable entrepreneurial ecosystem for intersectional entrepreneurs, are also under the responsibility of the national governments. These can be linked to supra-national recommendations (such as the OECD, G7 or G20) regarding institutional and infrastructural supports for promoting female but also migrant entrepreneurships at the national level of policy-making. However, our participants highlighted that measures to support gender diversity at the national level tend to focus solely on supporting female and migrant entrepreneurs. The national level provides a general institutional framework for equality (including for LGBT* in society), yet the experience of intersectional entrepreneurs is embedded at other geographical scales for support and entrepreneurial opportunity.

Regional levels: rural & urban

Our findings reveal the importance of the regional level for intersectionality in entrepreneurship since social and institutional environments differ heavily between and within regions. Many ad hoc interviewees during the fieldwork on the niche-market side mentioned that:

Sexual and gender diversity and LGBT* individuals are often “more rejected in our village than in town” (Entrepreneur 2), whereas the reference to the town was to a larger metropolitan city, such as Hamburg. As the Entrepreneur further commented, “conservative and ‘blinkered’ mindset”Footnote12 is more prevalent in rural than areas.

In fact, as one female non-heteronormative activist pointed out:

“[gender and sexual minorities] get more pushbacks than non-queer women” and that “Amsterdam is a free heaven for us, we’re liberated here, but in jail there” (Entrepreneur 6, referring to the village of origin in the South of the Netherlands).

Intersectional entrepreneurs are also limited in their entrepreneurial activities in rural areas and look for further opportunities through diversification activities as revealed by some of our entrepreneurs who moved out to the metropolis.

As one of them gave an example, they did not specialize in serving their own specific ethnic clientele, discussing the entrepreneurial dilemma between the location and the customer base:

“because I would go bankrupt, there were no more than us and a few others” (Entrepreneur 5, referring to their co-ethnics).

For example, as we observed, generic ‘Asian’ corner shops or restaurants are a common feature in rural areas, as well as less obvious combinations (e.g. a Portuguese-Vietnamese restaurant). While these issues are directly related to the rural entrepreneurship and its limited market, it must also be noted that there is – as it is the case with the female and gender minorities – a further dimension of likely societal barriers for ethnic minorities in rural contexts (Ishaq, Hussain, and Whittam Citation2010). These issues are where the concept of intersectionality in entrepreneurship is crucial to better understand these multiple dimensions of individual diversities within the rural setting.

Importantly, while intersectional entrepreneurs encounter the same challenges as mainstream entrepreneurs in rural regions – isolation in terms of access to resources and marketFootnote13 – they also suffer from additional disadvantages due to their ethnicity and gender. Social isolation was cited as the main reason for moving out of rural locations to more urban locations by many participants. This is a central challenge to analytical approaches used to study intersectionality (McCall Citation2005) as it poses a question about the categorization of these entrepreneurs among business support institutions. The argument is that such populations suffer from multiple disadvantages (e.g. being migrant entrepreneurs and operating in rural areas) but also suffer from issues specific to their individual contexts (problems specific to migrant entrepreneurs in rural areas such as facing the lack of an ethnic niche economy, therefore needing to go into diversification to ensure the new venture’s sustainability). In fact, many minority entrepreneurs operating in rural areas suffer from isolation from their own community, and often, additional discrimination and are the victims of racist actions as explained (sometimes crudely) by participants in our studies.

Against a background of cultural conservatism which is often found in rural areas, the regional migration into cities, especially of the young and the diverse, is commonly observed. This also leads to rural depopulation presenting considerable policy issues for the economy and local municipality. For entrepreneurs participating in our study, this trend was evident, too. The sociocultural interplay between push (flight from rurality) and pull (liberalism in urbanity) is clearly reflected in the entrepreneurial context. Push factors included insufficient opportunities in rural areas, such as the lack of a customer market, and limited wholesale networks. Pull factors included the existence of the niche markets in both ethnic minorities and gender minority communities concentrated in the city, as well as access to information and trade markets. A focus on the niche urban market as the major opportunity was mentioned by all intersectional entrepreneurs, especially those who focus on the LGBT* community market. It must be noted that the locational choice fell for these cities. This was less an active conscious entrepreneurial decision but appeared more as an obvious choice, given their position as insiders of the core LGBT* hubs. The participants were very conscious of the benefits of the urban context for entrepreneurship as LGBT*, as well as of the availability of access to the ethnic niche in these cities. ‘Knowing somebody’ or ‘knowing the location’ through previous visits and social networks and the concentration of co-ethnics in the respective city were mentioned as a factor of consideration when choosing the location – not necessarily as part of a conscious business strategy, but more as part of a social embeddedness connected to a social comfort zone.

Considering the LGBT* community, which comprises the niche market for intersectional entrepreneurs, the trend of moving to the city or at least visiting the city for community-related activities and events was prevalent in our findings. On the customer side, more than half of the surveyed LGBT* community members in Amsterdam (62%; N = 125) state that they regularly use LGBT*-specific businesses. Amongst such businesses, the usage of the different types of businesses was distributed at about one-third of those surveyed: LGBT*-owned businesses (32%), LGBT&-staffed shops or businesses (30%) or those with LGBT*-customer base (26%) and LGBT*-specific products or services (31%). In fact, there is a clear tendency of LGBT* customers to prefer LGBT* over mainstream businesses (73%; N = 139), where available. The spatial component of the market in cities compared to the suburban or even rural areas became clear in the question sets on the locational issues. These were mentioned by the respondents either regarding their residential choices and, if they were not living in Amsterdam, regarding the frequency of mobility to reach the city with its environment. 72% of the respondents’ state that the reason for a residence in or visit to Amsterdam is to have the opportunity to access such LGBT* businesses and services. A similar picture can be taken from the Hamburg survey. Whereas 68% (N = 114) of respondents use LGBT*-specific businesses, the frequency was around 30%, with the usage of LGBT*-owned businesses (24%) and LGBT*-staffed shops or businesses (34%), and even higher with the usage of businesses with LGBT*-customer base (38%) and those providing LGBT*-specific products or services (42%). The general preference of LGBT* businesses over non-LGBT* is similarly high with 74% of the respondents, and the locational factor of Hamburg for the purpose of the LGBT* market was at 64% (N = 109). These survey data are supported by the expert interviews and the impression from the participatory observation in the LGBT* community that cities, but especially those broadly known as being ‘gay meccas’, are ‘full with us who are from the boonies’Footnote14 (Activist X), as one of the survey participants pointed out, with the clear intention of fleeing the constraints on sexual and gender minority more prevalent in rural contexts. Such societal trends are crucial for the possibility for intersectional entrepreneurs to break out from limited markets in rural areas and to be starting up in the urban environment. These findings also support the use of a multi-scalar approach to studying entrepreneurial contexts and intersectionality.

Urban level: inter-urban

Reconsidering entrepreneurship from an intersectionality perspective, it becomes clear that those who suffer from multiple disadvantages, e.g. by being female, migrant or ethnic minority, or even additionally LGBT* are potentially provided better entrepreneurial environments in cities, in particular cities with a higher presence and acceptance of diversity in population such as Amsterdam, and to an extent in Hamburg. Yet, it is evident that there are differences in the openness and acceptance, but also discrimination and barriers depending on the cities analysed. Some metropolitan governments, as the example of the Rainbow Cities network illustrates, are not only aware but also pushing forward specifically urban-level policies for promoting and supporting a diversity inclusive society in their cities, whereas others neglect such issue and rely on national-level policies. This is where the consideration of the urban context in the sense of interurban analysis can be called for in entrepreneurship literature.

It is no coincidence that the intersectional entrepreneurs identified were located in ‘gay meccas’ such as Cologne, Berlin and Hamburg in case of Germany or in the popularly known liberal city of Amsterdam. Regarding economic and population statistics, these cities may not necessarily be the first choices for starting up a business in general. Especially in the case of a decentralized country, such as Germany, the market size in terms of population size or the economic potential of a city, other cities than the mentioned above could be taken into consideration. Merely in population size, Munich with its 1.45 million inhabitants or, by economic primacy, Frankfurt am Main, Germany’s financial capital, could be a viable option for a potential business location. In fact, when looking at the GDP per capita rankings of German cities, which could be seen as an indicator for the market potential, none of the mentioned cities of the intersectional entrepreneurs is listed within the top 15. What is crucial for intersectional entrepreneurs then is not primarily the contrast of the rural and urban per se, meaning not just the best next city is taken for the location, but the actual characteristics of the urban environment, with the combination of a higher share of LGBT* as well as ethnic minority population. Contextualized at the inter-urban level within Germany, there are important differences in urban contexts. Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne show an above-average percentage of foreign population (Berlin 22%, Hamburg 17% and Cologne 21.4%), whereas the other of the five most populous German cities have this characteristic in common and even top the others (Munich 27.5% and Frankfurt 30.5%). Yet, the share of the LGBT* community, which is a statistical uncertainty, is much higher in the three intersectional entrepreneurial cities than in the other. This calls for spatially contextualizing the opportunities from a more comprehensive intersectional lens, not merely looking at economic or population size, but also bringing more complexity into the assessment of the market by considering the gender and ethnic diversities among the cities.

Urban level: intra-urban

Consistent with previous research on diversity (and superdiversity) in entrepreneurship (Hall Citation2011; Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2019), the analysis of our qualitative shows that specific areas within the city are more diverse than others, meaning that favourable entrepreneurial environments for minority entrepreneurs are distributed unequally within cities. Our study confirms that such intra-urban differences are in favourability. As is the case with an intersectional entrepreneur in Amsterdam who is of Middle Eastern origin, part of the LGBT* community and a jewellery-maker, for ethnic niches one of the possible and viable environments would have been districts, such as Bos en Lommer. However, as the district is not only characterized by the high diversity of Middle Eastern migrants but also has a dominant Muslim population, the spatial context of favourability for the entrepreneur changes as sexual and gender minority in fact is not well perceived in these areas. Instead, the entrepreneur has started up and is also socially active in Amsterdam-Oost which shows high diversity by not only ethnicity but also religion and gender minorities.

As the person accounts:

“Here”, referring to the particular neighbourhood in Amsterdam-Oost, “it’s real(ly) diverse – old and young, different ethnic(s), different color(s)”, showing also the surrounding shops and people passing by (Activist Y).

The initiative Alle Kleuren Oost is a neighbourhood initiative, aiming to bring together the different communities within the district and organize neighbourhood-level activities and events for the mutual understanding of the people living there. As we observed, city districts, such as the Oost or De Pijp, provide a superdiverse entrepreneurial environment with the opportunity of ethnic and gender minorities to venture into. Other districts with high ethnic minority population, including population and religious diversity, might then become less favourable for other minorities, such as LGBT* minorities. Such is the case with Bos en Lommer, which would otherwise be rightly categorized as being superdiverse, at least when considering the number of ethnicities and religions in the area. As one ethnic and SOGI minority resident highlights:

“My father (of Sicilian origin) was first so shocked that I was living here – next to the mosque with all the men in galabea and things. But, he was then amazed about the diversity in the corner restaurant, just even the variations of women in hijab over abaya to very few, but still niqabFootnote15” (Activist Z). “But, in the end, for me [as a LGBT* activist] it became a bit too confining, and I wanted to get out, so I moved”.

Similar phenomena can also be observed in other LGBT* city hubs as in Hamburg. Districts, such as Hamburg-Billbrook or Veddel, are associated with a high percentage of foreigners and are districts with high diversity of ethnic backgrounds (in particular from Turkish origin) and ethnic minority entrepreneurs. Moreover, they also show higher diversity of business types in ethnic minority entrepreneurs in the neighbourhoods providing services and products for the communities. Similarly, the ‘stronghold’ of Eastern European migrants, in particular, of Polish and Russian backgrounds are highly concentrated in other districts, such as Hamburg-Bergedorf; similarly, Turkish migrants are concentrated especially in Wilhelmsburg. Whereas such districts are diverse in ethnic and also entrepreneurial aspects, offering not only gastronomy but also other ethnic minority businesses, in gender and also religious terms, they show less diversity. The specific concentration of ethnic minorities is also bound to specific religions, such as Roman-Catholic Eastern European or Muslim communities, and thus offers less access to the local market for other attributes of minority entrepreneurs, such as gender minorities. As the local activist X commented:

In Veddel,Footnote16 they [the city government] tried to make it a hip place, like top-down gentrification, offering students, artists and, you know, ‘pioneers’ like us [LGBT*] to come in, make the neighbourhood cool, and wait for the big money, the gentrifiers. But, that didn’t really work out; it’s diverse with all these migrants and people, but it’s not a place for us, we want the liberal colourful place, like Schanze or Karoviertel,Footnote17 right?

Further consideration of the spatial context of the intra-urban level is differentiation within districts or even neighbourhood. Hamburg-St. Georg, a place where while ethnic, sexual and gender minority populations are plentiful, is also commonly known as the gay area in town. Zooming into this district adjacent to the central station, we found that LGBT* community members mention the street Lange Reihe as being the main street of LGBT* community. It is full of bars, restaurants but also smaller shops for the LGBT* customer base. At the same time, the street Steindamm, only two parallel streets away and bridging the red-light district where one of the intersectional entrepreneurs finds the customer base for the sex toys and other product, is known as the ‘Araberviertel’, i.e. the Arabic quarter, where many ethnic minority entrepreneurs are located. This raises the question further that the spatiality is crucial for intersectional entrepreneurs and the research on them alike.

Though these results are still to be further explored in larger-scale empirical studies, what these findings already show is not only the intra-urban diversity of entrepreneurial environments but also the diversity of the degree of intersectionality within the city for the diversity of attributes overlapping in minority entrepreneurs. Research on intersectionality and entrepreneurship must therefore consider the context of the urban but also intra-urban dimensions that change the positioning of the respective intersectional attributes to fully grasp the entrepreneurial environment for minority entrepreneurs.

Discussion: embedding intersectional entrepreneurship into multi-scalar spatial context

By discussing the spatiality of intersectionality in entrepreneurship, the first contribution of this paper addresses recent debates on complex and multi-faceted ‘superdiverse’ contemporary societies (Vertovec Citation2007). While intersectionality in the social sciences refers to multiple dimensions of attributes of individuals (cf. McCall Citation2005), in the entrepreneurship literature, it has been historically limited to gender and ethnic/racial backgrounds (e.g. Al-Dajani and Marlow Citation2013; Carter et al. Citation2015, Citation2007). Gender in the entrepreneurship context focuses primarily on female entrepreneurship and its study has long followed the dichotomous idea of gender between male and female, an approach which has since been criticized (Marlow, Greene, and Coad Citation2018). As a crucial contribution, and responding to calls by Marlow and Martinez Dy (Citation2018) and Rumens and Ozturk (Citation2019) to “revisit the construct [of gender] itself“ (p.5), this paper takes extends the diversity of gender and sexual identities beyond the female-male binary through an analysis of novel and original cases of LGBT* ethnic minority entrepreneurs.

As we have defined, such entrepreneurs present different attributes of gender and ethnic minority background as intersectional entrepreneurs and we call for more research into intersectionality in entrepreneurship with a broader gender perspective.

Our first contribution is to discussions of intersectionality within entrepreneurship. Building from our findings, we show a relationship between entrepreneurship activities and the ability for intersectional entrepreneurs to live their sexuality, adding to the discussion by Shindehutte et al. (Citation2005), Redien-Collot (Citation2012) and Yamamura and Lassalle (Citation2021). The literature on ethnic minority and migrant entrepreneurs as well as the burgeoning literature on LGBT entrepreneurs reveals that the primary market is very often the community niche market. In the case of our study, LGBT-migrant entrepreneurs could choose to serve either of the two communities but face specific barriers due to their intersectional position.

Our second contribution is to embed the diversity and intersectionality of entrepreneurship within its spatial context (Trettin and Welter Citation2011). As can be conveyed from studies on gender, rural (Korsgaard, Müller, and Tanvig Citation2015) and ethnic minority entrepreneurship (Essers, Verduyn, and Kacar Citation2020), intersecting attributes are differently present, and dominant, depending on the spatial context in which entrepreneurial activities are embedded. Actual ‘everyday entrepreneurship’ (Welter et al. Citation2017) for these individuals is highly contextualized and varies by the respective spatial context. Openness to diversity attributes in particular contexts (e.g. Badgett, Waaldijk, and van der Meulen Rodgers Citation2019), be these gender, ethnicity or religion, is embedded in a larger supranational or national-level socio-spatial context of awareness, acceptance and integration of minorities. This can also be broken down to the regional level by contrasting the social environment between rural and urban areas (Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018). Cities in general have stronger tendencies to show more tolerance and acceptance for minorities (Schönwälder Citation2020), thus providing more favourable entrepreneurial environments for minority entrepreneurs as individuals and entrepreneurs. However, despite this general tendency, there are intra-urban differences (Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011; Yamamura and Lassalle Citation2019), which we observed in our findings too. Even in LGBT* hubs like Amsterdam, through the prevalence of the dimension encompassing religious and more conservative social norms in specific urban districts like Bos en Lommer (Muslim dominated population), intersectional entrepreneurs could be constrained in their economic endeavours. At the same time, such ethnically or religiously diverse niches present as favourable environments for ethnic and religious minority entrepreneurs. These issues emphasize the importance of also considering the inter- and intra-urban dimensions of intersectionality when analysing contextualized entrepreneurial activities. Based on the analysis of intersectional entrepreneurship at different geographical scalesFootnote18 (Brenner Citation2019; Trettin and Welter Citation2011), this paper brings together insights from different strands on minority and contextual entrepreneurship and calls for a reconsideration of the question on where intersectionality in entrepreneurship is occurring, adding a spatial contextualization to nascent debates aiming at exploring the diversity and complexity of entrepreneurship through intersectional lenses (Lassalle and Shaw Citation2021; Marlow and Martinez Dy Citation2018). Understanding of the diversity of socio-spatially embedded contexts impacting minority entrepreneurs (both from ethnic minority or sexual and gender minority groups) is crucial both for understanding their entrepreneurial activities, access to resources and enactment of opportunities (Redien-Collot Citation2012), and for developing policies at the adequate levels to better support the affected entrepreneurs. Contributing to discussions on intersectionality in entrepreneurship (Essers, Verduyn, and Kacar Citation2020; Lassalle and Shaw Citation2021) and to an understanding of LGBT* entrepreneurship (Redien-Collot Citation2012; Rumens and Ozturk Citation2019; Schindehutte, Morris, and Allen Citation2005), this paper proposes to conceptualize the spatial context of intersectional entrepreneurship and introduces this crucial spatial lens to the intersectionality debate.

By bringing a spatial understanding to research on intersectionality in entrepreneurship and taking into account recent calls for contextuality (Welter Citation2011) and consideration of gender in entrepreneurship (Marlow and Martinez Dy Citation2018), this paper finally develops the concept of multi-scalar embeddedness of intersectional entrepreneurship. Rather than identifying different research according to different scales of analysis, we propose to research entrepreneurship from a multi-scalar perspective, by contextually embedding entrepreneurial phenomena across the different scales (Brenner Citation2001) and analysing how entrepreneurs, such as intersectional entrepreneurs, are embedded and impacted by contexts at national, regional, city and neighbourhood levels. Contextual entrepreneurship should thus be extended to analyse the multitude of socio-spatial and institutional contexts in which entrepreneurs are simultaneously embedded rather than focusing on only one dimension of context. By bringing novel insights from intersectional entrepreneurship, which goes beyond the binary understanding of gendered entrepreneurship and considering at LGBT* entrepreneurship, we demonstrate how crucial this multi-scalar research approach is for better understanding the entrepreneurial environments and factors influencing the ventures.

As depicted in the model in , intersectional entrepreneurs are embedded simultaneously in different spatial contexts across different geographical scales. Global or supranational policies are as crucial as any national or regional context. The local level encompasses not only issues of inter-urban, that is differences between specific cities, but also within one city at neighbourhood levels. The individual attributes of entrepreneurs are differently embedded in these contexts and thus have different connotations and influences on the entrepreneurial ventures. In the case of minority entrepreneurs, these contexts are different and bear multiple disadvantages as barriers to information, networks or resources, which are existent at different levels. The important aspect of intersectional entrepreneurs, which must be stressed here, is that the challenges they face are not merely added or multiplied by the minority attributes, e.g. issues of ethnic minorities plus issues of LGBT*, but instead – due to the intersectionality of these entrepreneurs – bring even more complicated constructions of resource allocations. Being not only of ethnic minority and also sexual or gender minority, issues of challenges but also opportunities arise which are unique to intersectional entrepreneurs including access to resources and markets as well as restrictions to these (thus, the perforated rectangular which covers both minority groups but also goes beyond these contexts, ).

Conclusion

By adopting a multi-scalar approach, this paper makes the complex contextual embeddedness of intersectional entrepreneurs more visible. It follows Trettin and Welter’s (Citation2011) call for spatially contextualizing entrepreneurship. Yet, we go one step further in not only acknowledging different scalar levels in which studies are conducted and entrepreneurship analysed but in calling for a multi-scalar research approach for each case of entrepreneurship. Although this article is confronted with several limitations, primarily due to the highly sensitive topic of sexual orientation and gender identity in general, and also due to the aspect of the very elusive group of intersectional entrepreneurs, it provides novel and rare insights into the topic. Moreover, limitations may also apply with regard to the cities selected as different urban contexts. As discussed, these are inherently connected to further multi-scalar policy contexts; thus, phenomena could appear differently in other cities.

However, this article demonstrates that only by holistically analysing cases of entrepreneurship across geographical scales can researchers and policy-makers better understand the contexts of entrepreneurial environments for specific entrepreneurs, in particular, minority entrepreneurs. Research on diversity policies has shown that there are differences between municipalities with regard to acceptance and adoption of diversity policies. Similarly, entrepreneurial policies at different levels can also be adapted to the respective population more subtly, allowing more opportunities for potential entrepreneurs at the intersection of different minority groups. For policy-makers at all levels, a coordination and communication of their perspectives on intersectionality can help thrive intersectional entrepreneurs more in their regions of reference.

In fact, intersectional entrepreneurs as a specific group among the minority entrepreneur population are confronted with a lack of consideration by policy-makers due to the specific and complex nature of the different intersecting issues they face. Being embedded in different contexts, their entrepreneurial activities are affected by regulation and support but also by normative assumptions or direct actions taken at different levels. The consideration of intersectional entrepreneurship from a multi-scalar perspective brings understanding of the measures at different scales (supported by institutions of different administrative contexts), which would better address different unequal access to resources, embeddedness in communities and specific discriminations faced in different spatial contexts, which ultimately affect their entrepreneurial activities. First steps for such diversity-oriented and intersectionality-aware entrepreneurial policies could be roundtables bringing together different minorities and addressing specifically intersectional entrepreneurs, and also community-based campaigns by which diversity as a topic is more discussed in the minority groups, supporting the elimination or at least reduction of discrimination of intersectional entrepreneurs in their respective minority communities.

We see potential in this multi-scalar approach to entrepreneurial embeddedness which allows more subtle distinction but also comparison of practices and policies. Future research could use such a spatial contextual approach to holistically understand the entrepreneurial activities and the opportunities but also barrier-specific minority entrepreneurs face. Bringing also a broader understanding of gender diversity and considering intersectionality in entrepreneurship also offers an important and fruitful avenue of future research on entrepreneurship. Indeed, we call out for a more intersectional approach in general to the discourses on gender, ethnic and other minority entrepreneurship.

Acknowledgment

The Authors thank the EmSo team consisting of Lars Bührmann, Luis Karcher and Svenja Bierwirth for their enthusiastic support in Amsterdam and Hamburg. In fond memory of our time together in the “Kuhstall” at CAU Kiel University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Such research on sexual and gender minorities, whilst existent, is still rare in current entrepreneurship research (Germon et al. Citation2020; Redien-Collot Citation2012; Rumens and Ozturk Citation2019).

2. With the term ‘sexual and gender minority’ we refer to those with non-heteronormative sexual orientation and gender identities (SOGI) and use LGBTIQA* or LGBT* interchangeably for these minorities. We explicitly point at the diversities of identities and minorities in this context as the LGBTI* persons do not essentially constitute one homogeneous community.

3. We do address such disadvantages these entrepreneurs face and discuss especially the challenging and conflicting relations to the respective communities. Yet we focus on the entrepreneurial strategy in the spatial contextualization rather than embedding their entrepreneurship in the actual discourse of intersectionality.

4. In fact, intersectional entrepreneurs in broader understanding can also encompass ethnic or religious minority entrepreneurs who are operating in a sexual and/or gender minority market without own LGBT* identity. However, in this paper our cases are individuals who identify themselves as LGBT*, thus, intersectional entrepreneurs in the narrower sense.

5. For the purpose of legibility, we use LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) as an umbrella abbreviation, yet explicitly include the diversity of further gender and sexual identities with the indication of (*).

6. Such societal trends are reflected in different polls worldwide, see e.g. rise in LGBT* identification especially in younger generation of societies (LGBT demographic data on US in Gallup 2018, UK in Ipsos MORI 2017), as well as in the increase of diversity policies implemented in corporations and public institutions.

7. The Authors like to point out that although the usage of ‘community’ in entrepreneurial and business context is common, it is often sociologically inexact. More often, ethnic communities are not uniform within and are increasingly characterized by their diversity (Drucker Citation2011). E.g. one particular ethnic ‘community’ can be socio-culturally divided by the migration history background (oldcomers vs newcomers), by generational issues (first, second, third generations), by differences in regional origins, linguistic groups, socio-economic attributes, occupations or educational backgrounds (cf. superdiversity debates, Vertovec Citation2007). The same can be applied to LGBT* community as intra-group issues of e.g. biphobia or transphobia are existent, and gender and sexual minorities may not overlap in their socio-cultural practices either. However, from an entrepreneurial perspective, the entrepreneurs are trying not to limit themselves to the community niche market in the narrower sense. Instead, entrepreneurs try to extend the enclave by accessing a broader range of customers, even from the same community, in a broader sense (e.g. eastern Europeans instead of just Russians) for sustainability and growth purposes.

8. Interviews might delve into sensitive personal life issues and SOGI discrimination, making anonymization particularly crucial in research with these minority individuals.

9. Due to the aforementioned issues of access, sensitivity of the data and size of the population targeted, our sample was opportunistic by necessity. Other research on LGBT* populations or other vulnerable groups (such as migrants) have considered such sampling as the most viable technique for qualitative research (Browne Citation2006; Vershinina and Rodionova Citation2011).

10. Accessing the field and establishing trust with respondents were key issues and ensuring faultless anonymization was particularly crucial, hence the reference to ‘broad’ categories. Due to sensitivity and anonymity issues, the sexual and/or gender identities of the intersectional entrepreneurs cannot be disclosed here; multiple gender and sexual identities can be found in one individual.

11. In order to assure the anonymity of the entrepreneurs regarding the highly sensitive information on gender and sexual identities, the specific cities in each of the countries will not be listed here.

12. ‘Scheuklappendenken’, figurative term to indicate the narrowmindedness, lit. ‘blinkered (horse) thinking’.

13. Due to the size of the migrant or of the LGBT* communities but also due to the lack of visibility of the latter, the community market is smaller and limiting the sustainability of the businesses and their potential development and growth prospects.

14. „voll mit unsereins, die aus der Pampa kommen“ (colloquial German).

15. NB: Previously living in Egypt, the Activist used the traditionally Egyptian male long garment, also found in East African Muslim regions, but referred to long Muslim costumes of men in general and not necessarily to people of Egyptian origin. The usage of the terms for different veiling garments of women was rather vernacular, too, yet indicated the varieties of not only styles but also religious backgrounds found in the area.

16. NB: Veddel, adjacent neighbourhood to Wilhelmsburg.

17. NB: Areas known for the leftist’ movement and squatting that has been strongly gentrified in the last decades, yet remains a creative and alternative neighbourhood.

18. Developing on the terminology used within entrepreneurship and in geography (Brenner Citation2019; Trettin and Welter Citation2011).

References

- Ács, Z. J., E. Autio, and L. Szerb. 2014. “National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications.” Research Policy 43 (3): 476–494. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016.

- Affolderbach, J., and C. Carr. 2016. “Blending Scales of Governance: Land‐Use Policies and Practices in the Small State of Luxembourg.” Regional Studies 50 (6): 944–955.

- Ahl, H., and S. Marlow (2011). “Exploring the Intersectionality of Feminism, Gender and Entrepreneurship to Escape the Dead End.” EGOS Symposium, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Ahl, H., and S. Marlow. 2012. “Exploring the Dynamics of Gender, Feminism and Entrepreneurship: Advancing Debate to Escape a Dead End?” Organization 19 (5): 543–562. doi:10.1177/1350508412448695.

- Ahl, H., and S. Marlow. 2019. “Exploring the False Promise of Entrepreneurship through a Postfeminist Critique of the Enterprise Policy Discourse in Sweden and the UK.” Human Relations 74(1): 41-68.

- Al-Dajani, H., H. Akbar, S. Carter, and E. Shaw. 2019. “Defying Contextual Embeddedness: Evidence from Displaced Women Entrepreneurs in Jordan.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 31 (3–4): 198–212. doi:10.1080/08985626.2018.1551788.

- Al-Dajani, H., and S. Marlow. 2013. “Empowerment and Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical Framework.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 19 (5): 503–524. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-10-2011-0138.

- Alsos, G. A., S. Carter, and E. Ljunggren. 2011. The Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship in Agriculture and Rural Development. Cheltenham, Uk; Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Badgett, M. L., K. Waaldijk, and Y. van der Meulen Rodgers. 2019. “The Relationship between LGBT Inclusion and Economic Development: Macro-level Evidence.” World Development 120: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.03.011.

- Baker, D. 2012. “A History in Ads: The Growth of the Gay and Lesbian Market.” In Homo Economics, 43–52. Routledge.

- Baycan-Levent, T., and P. Nijkamp. 2009. “Characteristics of Migrant Entrepreneurship in Europe.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 21 (4): 375–397. doi:10.1080/08985620903020060.

- Berg, M. L., and N. Sigona. 2013. “Ethnography, Diversity and Urban Space.” Identities 20 (4): 347–360. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2013.822382.

- Bock, B. B. 2004. “Fitting in and Multi‐tasking: Dutch Farm Women’s Strategies in Rural Entrepreneurship.” Sociologia Ruralis 44 (3): 245–260. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00274.x.

- Bosma, N., and R. Sternberg. 2014. “Entrepreneurship as an Urban Event? Empirical Evidence from European Cities.” Regional Studies 48 (6): 1016–1033. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.904041.

- Bowleg, L. 2008. “When Black+ Lesbian+ Woman≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research.” Sex Roles 59 (5–6): 312–325. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z.

- Brenner, N. 1998. “Between Fixity and Motion: Accumulation, Territorial Organization and the Historical Geography of Spatial Scales.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 16 (4): 459–481. doi:10.1068/d160459.

- Brenner, N. 2001. “The Limits to Scale? Methodological Reflections on Scalar Structuration.” Progress in Human Geography 25 (4): 591–614. doi:10.1191/030913201682688959.

- Brenner, N. 2019. New Urban Spaces: Urban Theory and the Scale Question. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Browne, K. 2006. “Challenging Queer Geographies.” Antipode 38 (5): 885–893. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00483.x.

- Bruni, A., S. Gherardi, and B. Poggio. 2004. Gender and Entrepreneurship: An Ethnographic Approach. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Brush, C., P. Greene, L. Balachandra, and A. Davis. 2018. “The Gender Gap in Venture Capital- Progress, Problems, and Perspectives.” Venture Capital 20 (2): 115–136. doi:10.1080/13691066.2017.1349266.

- Bullough, A., D. M. Hechavarría, C. G. Brush, and L. F. Edelman. 2019. High-growth Women’s Entrepreneurship: Programs, Policies and Practices. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.