ABSTRACT

The practice of ‘academic entrepreneuring’ here signifies a scholar’s innovative, integrative and persistent mode of pursuing and integrating a university’s three tasks, those of doing research, teaching students and performing outreach activities. The success of academic entrepreneuring is conditioned by the individual’s and the university’s ability to become recognized as a legitimate and trusted knowledge-creator in the regional context. Building such confidence in turn requires continuous, hands-on and whole-hearted engagement with relevant stakeholders. This calls for the mobilization of embodied practical knowledge that draws upon cognitive, affective as well as connative capabilities. Four consecutive autobiographic projects, each covering two decades or more, are reported and reviewed as instances of academic entrepreneuring. These projects and their different qualitative methodologies and varying researcher identities jointly constitute a scholar’s life-long learning and achievements as an academic entrepreneur, beginning with mainly listening to the field and ending with invasive enactive research.

1. The challenge: academic entrepreneuring as constant knowledge creation

Here, entrepreneurship is recognized as a processual socio-material phenomenon that combines reflective sense-making and hands-on enactment of new ventures. Thus, entrepreneurship as ongoing creative organizing across boundaries should rightly be addressed as ‘entrepreneuring’ (Steyaert Citation2007; Johannisson Citation2018). The use of the present participle seems especially relevant in a university setting as an arena for constant learning, for the students as well as for its academic staff.

To the notion of ‘academic entrepreneurship’ is usually ascribed an instrumental, rational meaning, signifying the product of an entrepreneurial university as a provider of human capital for business development, for example, through the spin-off of new ventures from the university or the training of students for a career as business entrepreneurs. See, for example, Fayolle and Redford (Citation2014) and Foss and Gibson (Citation2015). What is more, this use of the term suggests that academic entrepreneurship mainly materializes when people and intellectual resources leave the academy! There is obviously a call for an understanding of academic entrepreneurship as innovative ways of organizing a university’s own activities and their relations to the environment.

In Sweden, a university’s three missions research, education and outreach activities, are laid down by law. Usually these missions are dealt with separately, thus conserving the university into a segmented organization. For career reasons, senior scholars prioritize research and junior academics are doomed to teach, while outreach activities are nowadays usually managed by separate administrative units. Rather than being dealt with as a bridge between the research community and the world of practice, entrepreneurial education has become a field of research of its own. See, for example, Gabrielsson et al. (Citation2020). Campus-living and the increasing internationalization of universities entail that students are often socially detached from the university’s regional context. Neither are students regularly invited to partake in the very process of doing research. This situation calls in question whether universities live up to their responsibility to generate and diffuse knowledge in the interest of society.

Others (Eriksson et al. Citation2021) criticize this limited view of academic entrepreneurship (see also Hytti Citation2021). Instead they provide a very generous definition of the field: ‘[W]e refer to all kinds of entrepreneurial activities carried out in academic contexts, including entrepreneurship education, research commercialization, and the extension of university-industry and university-society relationships more widely’. (Eriksson et al. Citation2021, 1) However, in spite of a broad range of contributions, the rich volume does not report on entrepreneuring as creative organizing across the three university missions. A possible explanation is that its use of ‘ecosystem’ as a basic metaphor – that generally can be questioned (Mars, Bronstein, and Lusch Citation2012) – draws attention from individual agency. Sam and van der Sijde (Citation2014, 902) recognizes the importance of focusing the relations between the three tasks but consider that as a managerial and not an entrepreneurial challenge: ‘An entrepreneurial university actively identifies and exploits opportunities to improve itself (with regard to education and research) and its surroundings (third task: knowledge transfer) and is capable of managing (governing) the mutual dependency and impact of the three university tasks’.

Thus, while ‘the entrepreneurial university’ usually is considered as an organizational phenomenon the focus here is on’ academic entrepreneurship’ as attitudes and practices associated with the individual scholar. Academic entrepreneuring here thus stands for continuous and creative ways by individual scholars of doing research, educate and relate to the society as well as enacting new ways of integrating these tasks. Such organizing is best done in the university’s domicile, that is, its regional context, where the university and its staff are visible and reachable.

The purpose of this article is to report and reflect upon the author’s practice of ‘academic entrepreneuring’ during a half-century post-graduate affiliation with Linnaeus University. These reflections concern how, as a researcher and teacher, I initiated and carried out four longitudinal and partially overlapping academic projects, each lasting for two decades or more. As a framework for this storytelling I elaborate in the following section on why and how academic entrepreneuring presents itself as a university scholar’s dedicated contribution to the development of its regional setting. Since such commitment calls for hands-on as well as intellectual and emotional involvement I comment in Section 3 on the call for embodied know-how not only in practising but also when researching academic entrepreneuring. Section 4 reports four empirical projects that carried my maturing to an insight through academic entrepreneuring, and in the following section I describe how these jointly directed my life-long learning journey into entrepreneuring as a practice. The concluding section summarizes the message of the paper in a call for academic entrepreneuring as a way of dealing with an increasingly uncontrollable world.

2. Founding a constructive dialogue between the university and its embedding region

Long-term perspectives on academic research and education may address different issues from the emergence of a discipline and its institutionalization to the individual scholar’s professional career. Today entrepreneurship has become established as an academic field of its own that self-confidently relates to many other disciplines. Presently, entrepreneurship as creative organizing across boundaries does not aim at increased economic wealth alone but also at social, cultural and environmental value production.

In the 1990s, influences from organization research paved the road for subjectivist approaches and associated qualitative methodologies in entrepreneurship research. See, for example, Steyaert (Citation1997) This certainly increased the field’s legitimacy as a social science on its own. Still, it took longer to conceptualize entrepreneurship as practice, an important step towards qualifying its role as a bridge between the academic community and society at large. Although even Schumpeter stated (Schumpeter Citation1943/l987, 132) that entrepreneurship is about ‘getting things done’, its image as practical doings, and hence as a point of departure for further theorizing of the field, was only realized after the turn of the century. Cf. (Johannisson Citation2011). Practice theory in organizational settings had then only recently become recognized as a research field of its own; see for example, Schatzki, Cetina, and von Savigny (Citation2001). Entrepreneurship as a teaching subject has been less questioned by the academic community and several of the programmes being offered include practical elements.

The university’s third mission, its involvement in outreach activities, is, as indicated, usually dealt with by intermediary institutions. Science parks, for example, are established to facilitate the commercialization of academic research, and semi-autonomous centres are created to organize extramural education activities. Regional partnerships in research and education with economic, social, cultural or environmental organizations benefit both the academic and the regional communities. The global research community is fed with contextualized data, while regional businesses and institutions become visible not only on the local arena but also nationally and globally. Less reflected upon are the scholars’ personal membership in regional civic organizations and their visibility in local media. Such engagements reflect the university’s and its academics’ insight into and general concern for the surrounding community. While research on the role of context for entrepreneurship is well established (Welter Citation2019), less is said about what universities do for their region generally and, in particular, whether all their research, educational and outreach activities are creatively organized.

The fact that a university is regionally involved in research as well as in education and outreach activities is no guarantee, however, that potential synergies between the three missions are activated. In his review of six university ranking systems, Marginson (Citation2014) applies eight criteria among which ‘comprehensiveness’ corresponds closest to what is here associated with the integration of the three missions: ‘Comprehensiveness: Rankings of universities should be as comprehensive as possible of university functions’. (Marginson Citation2014, 49). However, there are reasons for being sceptical of that criterion. Not only is it one of those with the lowest average grading of the six universities; it also differentiates the grading of the universities the most. Bliemel et al. (work in progress) in their recent bibliometric review of research on the entrepreneurial university identifies seven macro-themes in the literature that jointly certainly cover research, education and outreach activities. However, again the relations between the themes are not considered, neither on the organizational, nor on the individual level.

A university’s impact on and responsibility for the surrounding region goes far beyond the examination of employable students and contracted exchange with external stakeholders. Even if instrumental exchange certainly generates resources it also creates dependencies that intrude on the university’s integrity. Not only in its own interest but also in that of society, the university must preserve its autonomy so that it can use its voice to both criticize and compliment its regional stakeholders. Some universities, though, consider them to be too distinguished to get involved in the local and regional community, see for example (Feldman and Desrochers Citation2003). On the other hand, only if the university is trusted by its regional stakeholders will its role as an educator, in other words as a communicator of values and norms as well as a knowledge provider, be accepted. To begin with, building such confidence calls for sustained commitment to the bridging of the knowledge and ‘language’ gap between the academic world and the world of practice. Also, while the general aim of academic research and education – stating and communicating facts that are based on evidence – the coping with everyday doings and upcoming ‘situations’ is facilitated if the university, including its staff and students, is familiar with the region as well as visible and active in different public settings.

A relevant question is whether the field of entrepreneurship is feasible for hosting an intense dialogue between the university and regional interest groups. I think it is. First, there is a long tradition of studying small business/entrepreneurship in a regional context, something that many papers published in Entrepreneurship & Regional Development bear witness to. Second, since entrepreneurship, as indicated, concerns not only economic value creation it is, accordingly, in Sweden not only researched and taught at business schools but also at, for example, teachers’ colleges. This broadens the interface with the regional community. Third, considering that the field of entrepreneurship, especially as regards entrepreneurship education (Gabrielsson et al. Citation2020), has only recently become institutionalized, it remains open to new (qualitative) approaches to research. Fourth, from its birth as an academic field of its own, insights into entrepreneuring as a practical activity have been brought to the students via stories told by visiting entrepreneurs and through excursions to entrepreneurial firms. Fifth, as regards Linnaeus University in particular, it is located in a region that is nationally recognized for its entrepreneurial spirit.

Gaining insight and building trust call for patience, compassion and humility. This means that adequate longitudinal research requires a qualitative methodology that radically differs from corresponding studies in the natural sciences. The focus cannot be on process as a chronological phenomenon which can be depicted and analysed as a time series of standardized quantitative data. Instead, a kairos logic that patterns upcoming particularities has to be applied. Such longitudinal studies are rare. Adopting a psychodynamic approach Kisafalvi (Citation2002), though, retrospectively analyses how an entrepreneurial firm evolved over 35 years as the interaction between innate emotional dispositions and the social context.

Summarizing a review of existing qualitative research, Holland, Thomson, and Henderson (Citation2006, 18) state that this is a process where it is difficult to separate between research design and research process and that it is closely linked to how the scholar(s) concerned are involved. Ethnographic research and the way it deals with time should be explored to take on this challenge. Jeffrey and Troman (Citation2004) propose three modes for interacting with the field: ‘compressed’, ‘selective intermittent’ and ‘recurrent’. The compressed mode is momentary, while the recurrent one means that the researcher only periodically interacts with the field. The practising of the selective intermittent mode sounds promising but is not guided by a genuine dialogue between the researcher and the field but rather dictated by the researcher’s need to validate his findings. Obviously, the three modes proposed by Jeffrey and Troman (Citation2004) do not include dealing with situations triggered by the subjects concerned or by accidental occurrences. Besides, in their minds, research that lasts for about two years is long enough for building mutual trust and carrying out joint research. I think, though, that longer periods, even decades of interaction as in Kisafalvi’s (Citation2002) study, are needed.

Traditional ethnographic research sees ‘going native’ as a problem. However, hanging around in one’s own region and making the most of being a native, means engaging not only as a professional academic but also as a responsible citizen. Residence in the region builds trust and legitimacy, facilitates access, stimulates a caring attitude and provides the practical conditions for longitudinal studies. Regional empirical research, students’ internships in the vicinity of the university and outreach activities in the locality create the intimate knowledge needed to disclose how the three missions of a university may be connected. Taking on this challenge I adopt an auto-ethnography longitudinal approach aiming at depicting the author’s learning experience over an even longer period than Kisafalvi’s report on an entrepreneur’s strategizing. An auto-ethnographic study also calls for a different kind of knowledge than that of a visiting scholar.

3. Embodied knowledge as a source of insight into entrepreneuring

As a fairly young social science, entrepreneurship has in its quest for legitimacy mainly adopted analytical and interpretative modes of inquiry when doing empirical research. This reveals the cognitive bias in scholars’ attempts to capture a phenomenon involving human beings who, driven by vision and willpower, engage in the hands-on materialization of new realities. The entrepreneurial process appears as an emerging assemblage of hands-on copings with situations that are generated in dialogue with the environment (Joas Citation1996; Johannisson Citation2018). Entrepreneuring as situated practices thus stands out when compared with institutionalized routines in established organizations; compare, for example, Feldman and Orlikowski (Citation2011). Recognizing entrepreneuring as emergence also complicates adopting the role of a participant observer and practising ‘shadowing’ (Czarniawska Citation2007).

Studying entrepreneuring instead promotes auto-ethnography that ‘acknowledges and accommodates subjectivity, emotionality, and the researcher’s influence on research, rather than hiding from these matters or assuming they don’t exist’. (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011, 274). See also Ellis and Bochner (Citation2000), Hayano (Citation1979) and Van Maanen (Citation2011). The personal life and previous experience of scholars obviously influence the way they share new experiences with the subjects under study. Speaking for social sciences in general, Thanem and Knights (Citation2019) claim that it is time to abolish the belief that knowledge is the product of rational thought alone and instead keep those being studied at a distance in order to avoid ‘going native’. Bispo and Gherardi (Citation2019) also point out that embodied practice-based research implies that the scholar both affects and is affected by the people and phenomena inhabiting the empirical setting being studied.

In their philosophically grounded review of embodied research methods, Thanem and Knights emphatically quote Wacquant (Citation2015), who proposes a ‘carnal sociology’ that ‘strives to eschew the spectatorial viewpoint and grasp action-in-the-making, not action-already-accomplished’ (Wacquant Citation2015, 5). ‘Carnal’ sociology both offers an ‘intellectual understanding’ and triggers ‘dexterous’ handling of upcoming situations. Wacquant (Citation2015) suggests a kind of observing participation as an appropriate embodied approach (see also Seim Citation2021). ‘[E]nactive ethnography, the brand of immersive fieldwork based on “performing the phenomenon”, is a fruitful path towards disclosing the cognitive, conative and cathectic schemata (that is habitus) that generate the practices and underlie the cosmos under investigation’. (Wacquant Citation2015, 2, italics in the original).

While Wacquant studied an institutionalized practice (boxing), entrepreneuring as the creative organizing of situated practices calls for a methodology that can capture the unique emergence of a phenomenon. Only by instigating own new ventures and experiencing their becoming in real time will the researcher be able to track the characteristics of entrepreneuring as a socio-material process. This methodology for disclosing entrepreneuring as a collage of situated practices is what I address as ‘enactive’ research (Johannisson Citation2018). The conclusive findings of empirical research present entrepreneuring as a weaving process where the entrepreneur’s personal network forms the warp while the activities that combine into situated practices make the weft (Johannisson Citation2018, 185–192).

A successful enactment of a venture is conditioned by the scholar’s familiarity with the context, in this case the region, and the social and trust capital created by interacting with the region’s different constituencies and with previous research and educational activities being carried out in the region. Wacquant’s (Citation2015) three years in the field may be sufficient to integrate into the values and practices of a profession but are hardly enough to acquire an insight into such a complex phenomenon as a region with all its distinctive features in terms of business practices, social norms and cultural values. In order to keep up with upcoming situations, the researcher should preferably be domiciled in the region. The risk of becoming enculturated, ‘going native’, has then to be accepted albeit balanced with a reflective mind. Enactive research is obviously no abode for scholars who, like colonizers and robber barons, rush into a location and leave it with ‘facts’ to exploit in their own interest. By enacting ventures in the capacity of an entrepreneur, the scholar is caught by the same paradox as ‘real’ entrepreneurs in that engaging in entrepreneurial activity is about alertly, creatively and timely seizing opportunities while at the same time committing oneself to a long-term involvement in both the venturing process itself and its (regional) setting.

Here, enactive research into entrepreneuring is considered as the closing phase of a long learning experience structured in the same four stages that, according to Wallas (Citation1926), characterize any creative process: preparation, incubation, illumination and verification. Since each of these phases is represented by a lasting and embodied engagement, that is not a product of intellectual activity alone, Wallas’ four-stage model is here applied to what I address as a ‘crea©tive’ process since it is constituted by creative thought and associated creative action. By narrating four such consecutive and partially over-lapping long-term projects, I will present and discuss how research, education and outreach activities may combine into an insight into academic entrepreneuring. In the following, the stories of these projects will be told.

4. Tales of four enduring academic commitments to regional development

My interest in academic entrepreneuring was initiated and maintained by nearly a half-century affiliation with Linnaeus University in my home region. The roots of Linnaeus University only go back as far as the 1960s, and I joined this seat of learning in the mid-70s after having spent my pre-doctoral years at Umeå University in Northern Sweden. It is no wonder that the forerunners of Linnaeus University, in order to be able to stand up against patronizing well-established urban universities, took new initiatives in collaboration with regional interest groups. My attitude to academic work in Växjö in Southern Sweden was that of an explorer of unknown territories.

The four projects that I narrate and reflect upon below brought different academic challenges, each one of them featuring a unique course of events. Nevertheless, the projects had three features in common. First, they all put my capabilities to test, as researcher and teacher and also as communicator. All of them emerged out of an intense dialogue with regional actors, both face-to-face and indirectly through local and regional media. I considered these enduring involvements as self-imposed duties and perceived them equally as personal commitments and professional challenges. Secondly, all projects comprised a number of minor events, some triggered by me as a researcher and teacher and others by regional stakeholders. Third, I left no loose ends in my dialogue with stakeholders. I dealt carefully with any action taken or public statement made by them in order not to jeopardize our emerging trust relationship. As the building contractor has to deal conscientiously with every detail to satisfy the owner, the committed academic has to take all engagements, no matter how small, to his heart and attend to each of them accordingly.

In I summarize some distinctive features of the four projects. My ambition is not to induce a normative model of the ultimate way of making a considerate and responsible scholar. Instead I will in Section 5 comment on how my sequential involvement in these projects constituted my insight into entrepreneuring as a learning process, from that of a hybrid observer and administrator coaching students to that of an academic hands-on doer, challenging both the research community and the students being involved in enacted ventures. The narratives cover rational and planned activities as well as spontaneous, often emotionally driven, initiatives and coincidences that triggered the launching of the projects’, energized their constitutive events and provided reasons for closing the project.

Table 1. Academic entrepreneuring as a long-term engagement.

Starting my learning trajectory the first project The Creation of a Small-Business Management Programme Incorporating Internship (Case A) as the program organizer and main teacher I focused on imbibing the atmosphere that embeds small entrepreneurial firms and shared that with the students as trainees. In the second project – Mapping the Industrial District as the Emblem of Collective Entrepreneurship (Case B) – my identity changed over time from that of a positivist researcher mapping local networking between firms to that of a considerate critic of a self-centred business community. In the third project – Turning a Languishing One-Company Town into a Resilient Community (Case C) – I participated as researcher and volunteering activist in the mobilization of new enterprises and jobs in a community that had undergone a crisis. The fourth narrative -Doing Enactive Research Disclosing Entrepreneuring as Practice (Case D) – describes how I took on the identity of an entrepreneur and over two decades launched two ventures in order to uncover generic entrepreneuring practices. – provides an overview of the four projects.

4.1. Case A: the creation of a small-business management program incorporating internship

When I joined Linnaeus University in the mid-1970s one of my new colleagues had tried to launch a program in Small Business Management. Its basic idea was that the student should spend half the week at the university and the other half as a trainee in a small or medium-sized entrepreneurial firm in the region. Still being an assistant professor he had, however, not been trusted to start the program but as a team we were allowed to go ahead. The objective of the program was not to train the students for entrepreneurship but to make them employable in family businesses where they would support the entrepreneur with administrative tasks. See Johannisson (Citation1991).

Originally, the program just lasted for one academic year and the liabilities of newness resulted in only attracting eight students. Soon enough, the program was, however, extended to cover two academic years and from then on annually attracted about 20 students. In order to increase the legitimacy of the program it was after some years further extended to a three-and-a-half-year master program. Then, the first two years of the program were shared with all master students, while the last one-and-a-half years were run according to the original design, including the internships. Both extensions triggered some other Swedish universities to copy the program. After I left it in the mid-90s, my successor as program coordinator reoriented it towards corporate entrepreneurship and the students were organized as teams that practised in larger firms. (Berglund et al. Citation2021) report in detail about Linnaeus University as an alternative entrepreneurship as creativity-driven university (AEU) with its roots in the Small Business Management program.

Linnaeus University is located in a region that was dominated until the turn of the century by small manufacturing firms with limited professional management. Practising entrepreneurs were often sceptical of academic knowledge. Nevertheless, many firms engaged voluntarily in the program, probably because they felt obliged to be involved in ‘their’ regional university. In turn, those of us who were teachers and examiners paid the entrepreneurs due respect by visiting the company when it was time for ‘their’ students to report their assignments to the entrepreneur. This means that the teachers, including myself, visited the student/company twice every semester during the internship. This routine made the entrepreneurs understand that we took as academics our collaboration very seriously. This was not because the information we received on site might be exploited for research purposes. On the contrary, for two decades I saw this exchange between regional firms and the university only as an opportunity both for coaching the student and for my own learning. Only on one occasion did I try to combine my site visits with research. However, since it felt awkward to break the routine and exploit the situation for my own purposes I did not even then publish an academic report based on the experiences gained during the two decades I organized the program.

The program’s substantial teaching/learning activities were supplemented with joint meetings at the university with students and ‘their’ entrepreneurs. However, even more important were the social events that I and my fellow teachers arranged for and with the students. For example, every new cohort of students was ‘inaugurated’ at a social event outside the university. Further social initiatives were taken by the students themselves. I also brought three cohorts of students abroad to visit foreign universities and institutions involved in small-business education and research. These excursions were partly sponsored by the program enterprises. Obviously, the entrepreneurs appreciated the students’ work in the firms. Many of the students – one year as many as a third – were after their examination offered a job in their host company.

There were of course occasions when the collaboration between the student and the company did not work out well and I had to take a stand. In one enterprise, it was obvious that the owner-manager did not want to offer internship to a student because of his physical handicap. I then cancelled the co-operation with the company altogether. In another case, the student, when presenting his final report to the company board, treated its members as if they were soft-headed. After that meeting I had to apologize for his behaviour to the entrepreneur.

During this first preparatory stage of my crea©tive-learning cycle I paved the ground for a more systematic and in-depth research in the region by giving both the students and myself a general insight into its small-business community. The owner-managers on their part became aware of the competences of young academics and the program also demonstrated to further regional stakeholders the benefits of small-business research and education.

4.2. Case B: mapping the industrial district as the emblem of collective entrepreneurship

Small companies appear in many shapes, for example, as Bohemian artisan firms, as introvert family businesses or as extrovert entrepreneurial firms. Clustered small firms are often looked upon as aggregates that either suffer from a hostile environment or benefit from a conducive environment. There are, however, clusters of small firms, addressed as ‘industrial districts’, which self-organize and become self-sufficient. See for example (Becattini, Bellandi, and De Propris Citation2009). Although individual firms in such settings may lack cost efficiency, as interactive collectives they are entrepreneurial and successful. In the 1970s and 1980s I carried out a series of social-network studies in the community of Gnosjö, the only industrial district in Sweden. See for example (Johannisson et al. Citation1994). Gnosjö was in the 1980s the country’s most prosperous region and its local business climate, ‘The Gnosjö Spirit’, served as a model for other communities

My repeated visits to and intimate knowledge of the Gnosjö region resulted in a number of invitations from its local business associations to present my research. At those meetings, I seized the opportunity to also critically comment on local practices, values and norms (thoroughly reviewed in an ethnographic study by Wigren Citation2003). For example, putting my good name at stake I published, a few days before my presentation of a study at a meeting with the local owner-managers, an article in the local newspaper. There I argued that the Gnosjö business community should establish local funds to finance employee ownership (on the national level these funds had already been laid down by law). This suggestion was not received well. When at the end of my presentation of the research findings I repeated my arguments, a number of owner-managers left the room!

In spite of the provocative article, my legitimacy as a researcher as well as the trust in me remained and the Gnosjö business community hosted some of the student internships reported in Case A. As a co-director of the European Doctoral Program in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management I also brought international students to Gnosjö annually for 15 years. There they were split into smaller groups and assigned alternative conceptual frameworks for making sense of Gnosjö’s historical success and diagnosing its future potential. Thus guided by different models, the students interviewed local actors – besides owner-managers also, for example, local politicians and labour union representatives – in order to find out about the sustainability of the Gnosjö industrial district. Depending on the assigned framework, some groups concluded that Gnosjö would remain as a national role model, while other groups came to the conclusion that the Gnosjö spirit had outlived itself. See Johannisson et al. (Citation2007). I then used these contradictory findings to test the owner-managers’ self-centredness as well as (indirectly) my credibility in Gnosjö. Writing two articles summarizing the students’ contradictory findings, I approached the two dominant daily newspapers in the region. I managed to persuade both editors-in-chief to publish either of the two articles on the very same day. In one newspaper I thus praised the Gnosjö business community, while heavily criticizing in the other one its complacency. Only the critical article was, however, read by the local businessmen and its message triggered a local debate that lasted for several months. It ended up in an urgent request that I should explain myself at a public meeting. For two hours I was then cross-examined by 200 owner-managers who demanded my head. Only when one of the participants, a newcomer to the region with a university degree, made the comment that even the Gnosjö business community might have something to learn, the attacks on me ebbed. See also (Hjorth Citation2011; Steyaert Citation2011).

When, some years later, an industrial development centre was established in Gnosjö it was soon enough considered a leading one in Sweden. However, the imported knowledge creation practices never synchronized with the local ones and after a few years in operation the centre was closed down. When at the turn of the century the region was heavily hit by global market forces, Gnosjö was almost defenceless and my contributions at public meetings then concerned encouraging rather than criticizing the owner-managers.

During this second incubation stage of my crea©tive-learning cycle I used quite traditional research methods, spiced with minor, yet provocative, tests of owner-managers’ attitude to academic knowledge. My ambition was to make the owner-managers aware of the need for broadening their knowledge base in a changing world. My own lesson was that I had to change my researcher identity from that of a participant (although active) observer to that of an observing participant.

4.3. Case C: turning a languishing one-company town into a resilient community

Being about to close my second doctoral thesis work on mergers between family businesses I visited late in 1979, just one week before Christmas Eve, one of them, the Målerås glassworks in the ‘Kingdom of Crystal’, Sweden’s dominant art glassware region in southern Sweden. There Mats Jonasson drew me into a dark corner of the oversized and worn building and asked if I could help him and his fellow glassworkers to redeem the factory and recreate the glassworks as an independent business. Mats was then employed as an engraver at the Kosta Boda glassworks, which had acquired Målerås when the Royal Krona Group, the outcome of a merger between five small family businesses, went bankrupt after just a few years in operation. Mats and I decided to establish Project Målerås and invited not only the few existing local small firms to join in but also all who wanted to start their own local business. Monthly meetings, chaired by Mats Jonasson with me as the secretary, encouraged a dozen persons, locals as well as outsiders, to launch ventures. We then used the networked Gnosjö business community as a role model. For example, as a designer Mats Jonasson helped several firms with product development. In 1983, our efforts were crowned with success. Like Phoenix from the ashes, the Målerås glassworks rose again, even though with only 15 employees. Still, as a cooperative it had now more than a hundred owners, besides Mats and the glassworkers, further local people and external supporters like me.

Well exposed by the media, Målerås’ reincarnation soon enough became a role model for mobilization in other declining Swedish communities. It also aroused the interest of Orrefors glassworks, which together with Kosta Boda then dominated the Swedish crystal-glass industry. Orrefors thus staged a hostile takeover and offered the owners 13 times the nominal value of the shares. Mats Jonasson counteracted but could only offer 5 times the nominal value. The far majority of the owners, however, out of solidarity sold their shares to him. I still kept mine, arguing that to me it mainly had a symbolic value. In the local newspaper I also strongly criticized the Orrefors attack on the truly local firm and its community. Målerås glassworks with Mats Jonasson as the dominant designer and owner continued to grow and with its well-known international trademark became the largest national producer of artistic glass in a declining Kingdom of Crystal.

Introducing the concept of ‘community entrepreneur’, it was not until 1989 that I began to internationally publish my experiences from participating in the mobilization of Målerås. My co-author of that article was the only student involved in the Målerås project. The main reason for this rather weak connection between research and education was my close personal relation to Mats Jonasson, which was difficult to share with others. However, as early as 1983 I had published a booklet in Swedish that presented the Målerås story to a broader audience. Local and national newspapers reporting from the mobilization provided photos for the book free of charge. Shortly afterwards, I had, though, felt obliged to publish a critical article in the local newspaper that addressed the internal organizing of the glassworks. Considering that it was reconstituted as a cooperative, I argued that the glassworkers should be offered training in business administration in order to be able to participate actively in the running of the company. Mats Jonasson and the managerial staff asserted on the contrary that the workers’ focus should be on production. Having to accept this decision, I thus publically proclaimed that my involvement in Målerås as a participant/activist had come to an end. Ever since then I have, though, stayed in touch with Mats Jonasson and Målerås glassworks by occasionally meeting with Mats and regularly and actively participating in the shareholders’ annual meetings. Over the years I have published a number of research papers including the Målerås case; see for example, Johannisson and Nilsson (Citation1989) as well as further articles in the local newspapers commenting on the development of the Målerås glassworks and the Kingdom of Crystal.

During this third illumination stage in my crea©tive learning cycle it became evident to me that I could not remain a passive spectator vis-à-vis an entrepreneurial process but had to gradually engage more actively in order to capture its driving forces. However, when my view of the mobilization process came into conflict with that of the community entrepreneur I realized that I had to back off as an activist/observing participant but stayed as a supporter of the company and the small town.

4.4. Case D: doing enactive research disclosing entrepreneuring as practice

In 1999, I decided to put a different kind of inside study of entrepreneurship to test. This project was triggered as much by personal curiosity as by professional ambition and was both emotionally and rationally energized. The igniting spark was that the university administration turned down my proposal to celebrate the approaching new millennium with an event that would involve the public at large. Another driving force was my budding interest in entrepreneurship as practice and my desire to study it by adopting an embodied methodology: the ‘enactive’ approach. See Johannisson (Citation2018) for details.

Two ventures aiming at non-economic value creation, cultural and social, respectively, were enacted. The aim of the first, the Anamorphosis project, which ran during 1999, was to show that linking culture and science may stimulate regional development. This venture took place at an artists’ colony located in the vicinity of the university. The second venture, the SORIS project, was carried out in 2014 and aimed at demonstrating the potential of social entrepreneurship in regional development. In order to bridge between academic and public interests, both ventures were furnished with advisory boards staffed by practitioners representing different stakeholders but also being members of my personal network. Since the financial budget was very tight in both ventures, this voluntary provision of human capital was decisive to their realization. The participating practitioners also added to the legitimacy of the project and secured that the ventures reached out to further regional stakeholders.

Besides providing an insight into entrepreneuring as practice and feeding outreach activities, the two ventures were also designed to offer an innovative context for educating students for and through entrepreneuring. In the Anamorphosis venture I planned to collaborate with the university’s teachers’ college, which had asked me and a colleague of mine to run a course on entrepreneurial learning. The majority of the students, however, never showed up, possibly because entrepreneurship outside the business context was still a controversial subject. Possibly, their regular teachers had got cold feet and recommended the students to skip the optional course. The few remaining students were like apprentices learning by dealing with different practical issues.

In the SORIS venture, the students joined a regular entrepreneurship program at the business school – the follow-up of the one presented in Case A – participation in the project being an integrated part of that program. The students were divided into three groups, each being assigned to a social project. The public activities in the Anamorphosis venture – an art exhibition and 30 interactive public seminars – were mainly accommodated by the artists’ colony. In the region’s memory it remained in as a major event. The SORIS activities were to a great extent carried out in the field but their findings were presented at public meetings on campus and broadcasted by a local (social) enterprise. The main findings of this project were included in the region’s innovation plan.

Critical incidents accompanied the enactments of both projects. In the Anamorphosis venture, for example, the university denied the project a link to the university’s homepage. The original disagreement between the project organization and the university administration only ceased when the final public seminars were held on campus. In the SORIS venture, tensions were for two main reasons stronger and more frequent. First, the majority of the students were only moderately interested in social entrepreneurship – their focus was on business studies. Secondly, the students had problems with accepting the external leaders of the three ventures – a consultant, two would-be social entrepreneurs and a social worker. In their minds the first project leader was too demanding, the two social entrepreneurs too weak and the last one too irresolute.

A well-founded question is how I bridged the distance in time between the two ventures to make them jointly provide a basis for conceptualizing entrepreneuring as practice (Johannisson Citation2018). This was accomplished by vitalizing my role as a teacher and intensifying my outreach involvement in the region. My teaching during that period mainly concerned graduate and post-graduate courses and guest seminars. The majority of my research publications after the turn of the century have concerned social entrepreneurship and methodological issues, mainly then interactive approaches. As regards outreach activities in the context of the Anamorphosis project I was for a number of years on the board of the cooperative that organized the artists, then also chairing the regional board of Coompanion, a nationwide organization aiming at creating and supporting cooperatives. When SORIS was enacted, I was the chairman of the board of an organization that supported a major regional social enterprise and that organization also formally hosted the SORIS project.

In this closing fourth verification stage in my crea©tive-learning cycle I practised entrepreneuring hands on – appeared as an ‘entresearcher’ in two projects to be able to develop an embodied methodology for capturing the unique features of the phenomenon. In a concentrated form these came out as the entrepreneur’s conscientiousness and grit. In retrospect, I understand that the nature of the approach made it difficult for students to engage whole-heartedly. In both projects a dialogue with the regional society was, however, successfully established, in the Anamorphosis case with the general public and in the SORIS project with different institutional stakeholders.

5. Academic entrepreneuring as a life-long learning experience

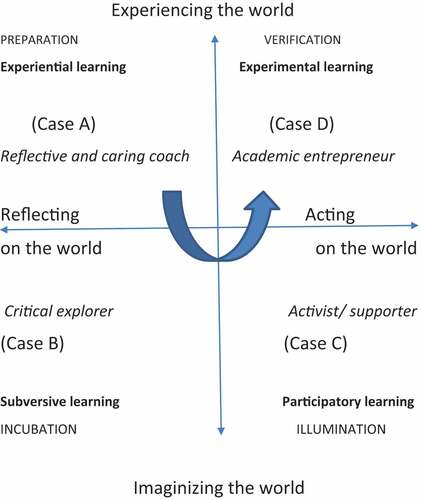

A long-term engagement in the field leads up to both a responsibility and a capability to organize one’s own professional career as an educational journey. As argued above, these experiences only structure themselves in a meaningful, innovative and considerate way if the scholar’s engagement in all three missions of a university – research, education and outreach activities – is recognized, practised and integrated in the regional setting. Here, I thus want to mark out the learning route that I have followed. This task includes narrating how the integration of the three missions was accomplished and what identities and methodologies I adopted to manage my crea©tive-learning process. illustrates this adventurous journey.

Figure 1. Embodied research into entrepreneuring as practice – from experiential to experimental learning.

about here

The graphic model is carried by two dichotomized dimensions. The vertical axis thus differentiates between how the world is approached – as a concrete actuality/practice to bring order to or as a phenomenon to which meaning has to be ascribed. The horizontal axis depicts what means are used to make sense of the world, by reflecting on casually made experience or by deliberate hands-on experimenting with the world. In the figure, the four presented projects are arranged, one in each quadrant according to its position on the two dimensions. The curvilinear arrow indicates the chronical order in which the four projects were enacted, thereby combining into my creative- learning experience as an academic teacher and researcher carried by my embedding in the regional context. The arrow marks my learning experience as a creative process as modelled by Wallas (Citation1926), yet written as crea©tive since transitorily integrating my intellectual work and embodied involvement

The top left quadrant of the figure describes my continued formation as a researcher/teacher after my academic manhood test in terms of a licentiate dissertation. As a teacher, I guided undergraduate students in their bridging between formal, academic knowledge and the practices of entrepreneurial firms (Case A). I myself got acquainted with the world of these organizations by regularly visiting the firms and attending the meetings on site when the students reported the outcome of their investigations to the entrepreneur. My focus was on the education and outreach missions, while the project’s immediate contributions to my research were negligible. My benefit was instead a solid introduction to the mental and practical world of small and medium-sized entrepreneurial family businesses, an experience that prepared me for more dramatic engagements. Here, I address this experience as indirect experiential learning mainly accomplished by listening to a large number of conversations between students and entrepreneurs. My identity as a hybrid of a participant observer and an observant participant (with a focus on the latter identity, compare Seim Citation2021) was accordingly that of a reflective and caring coach.

In the project positioned in the bottom left quadrant, traditional positivist academic research was the point of departure for further knowledge creation (Case B). The original ambition was to empirically test the image of the networked local/regional business community as a self-organizing social system. In the aftermath of these investigations I took action and challenged the local businessmen by arguing in public that a greater outward orientation and more frequent acquisition of formal knowledge were needed to make the business community stay resilient. I address this approach as subversive experiential learning, since I staged provocative tricks in order to make the owner-managers reveal their self-will. Drawing upon my field experiences in the locality I thus took action by putting all the confidence that I had built over almost two decades at stake by taking on the identity of a constructive critic, carried by the ambition to enlighten the local business community. The tumult that my initiative caused made me imaginise even more hands-on venturing. My identity, though, remained that of a hybrid between participant observer and observant participant, although in this case with a focus on the former identity.

The bottom right quadrant accommodates a project aiming at revitalizing a small town (Case C). This emancipatory process was initiated and organized by a community entrepreneur whom I seconded as a member of a local task force. As an observant and active participant I experienced mutual learning as the process evolved. In addition to my concrete contributions to this deliberation process, I positioned myself as a responsible researcher by publishing two controversial articles in the local newspaper. The first announced the end of my participation as an activist in the project since my ideas as regards the further development of the glassworks and the community did not comply with those of the local key actors. The second article dealt with an external threat to the mobilization process in the form of a hostile take-over bid by nearby glassworks. My identity during the intense phase of this process was thus that of a critical activist experimenting with different initiatives. Ever since, I have remained a concerned supporter and the experience gained in that project triggered the idea to launch my own ventures to experience entrepreneuring as practice from the inside.

The top right quadrant accommodates my hands-on enactment of two events with the ambition to induce the practices of entrepreneuring (Case D). The ambition was also to illuminate entrepreneuring as the creation of other values than economic ones and, accordingly, the projects concerned crea©tive organizing aiming at generating new cultural and social values. Covering the other two missions of a university as well, students were engaged in the very enactment of the projects. External stakeholders were invited to legitimize the projects but also to operate as messengers and influencers in the regional context. Being designed and controlled by me as an ‘entresearcher’, these two events provided genuine experimental learning for me as an academic entrepreneur. My enactments made it possible to inductively and crea©tively verify entrepreneuring as a creative practice carried by conscientiousness and grit, cf. Johannisson (Citation2018, 190).

The semicircular arrow connecting the four projects thus features my field-based half-a-century long learning process carried by declarative, procedural, conditional knowledge concerning entrepreneuring as well as contextual awareness (Hägg Citation2017, 47). I started off as a humble teacher, listener and administrator but soon enough challenged an iconic business community on its home ground. Next, I took active part in a project which proved that imagination and will can tame forces that make a whole industry decline. In the last of the four projects, I tested my own capabilities as an academic entrepreneur by enacting events which, with regard to research findings, teaching model and ways of involving regional stakeholders, tried out new ways of doing research, stimulating students and expressing care for the region. My line of argument thus suggests that a good scholar is an entrepreneurial one by integrating in the own work the three missions of a university. The proposed entrepreneurial practices do not aim at achievements favouring a private professional career but rather at personally becoming a constant learner and making the university more able to serve society. This makes the scholar and the university into a soci(et)al entrepreneur (Berglund, Johannisson, and Schwartz Citation2012; Verduijn and Sabelis Citation2021).

Linnaeus University as a contributor to societal development through entrepreneuring is today different from what it used to be in the 1970s and 1980s when its Small Business Management Program, carried by personal relationships, dominated the university’s exchange with external stakeholders. Today, the research into and the teaching of entrepreneurship have, on one hand, broadened considerably to also include, for example, cultural and social entrepreneurship. On the other hand, the once intimate relationship between the university teachers and students on one hand, the external stakeholders on the other, has become more formal. The technology-oriented faculties have also grown considerably after the turn of the century. This means that the (constructive?) tension between Linnaeus University as a ‘technological innovation-driven university’ (TEU) and as the ‘alternative entrepreneurship as creativity-driven university’ (AEU) remains. Compare (Berglund et al. Citation2021).

6. Conclusion: academic entrepreneuring as the core of a regional university

The German sociologist Harmut Rosa claims that the modern world is running amok, in other words is uncontrollable (Rosa Citation2020). The global COVID-19 pandemic during 2020–21 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 are recent mega-events that verify his statement. Like Goodheart (Citation2020), Rosa argues that our confidence in rational thought has gone too far at the expense of knowledge associated with manual skills and care for fellow human beings. Rosa’s compatriot Hans Joas (Citation1996) states that, however, wilful the entrepreneur may be as a sense-maker (Czarniawska-Joerges and Wolff Citation1991) the concrete situation at hand decides what action to take in order to deal with ambiguity. Under such circumstances, planning does not make sense but rather cherishes illusions. Instead, organizations have to be keenly aware of what the present situation demands and be ready to open up for a dialogue and demonstrate responsiveness: ‘A capacity for, or rather a dependence on, resonance is constitutive not only of human psychology and sociality, but also of our very corporeality, of the ways we interact with the world tactilely, metabolically, emotionally and cognitively’. (Rosa Citation2020, 31). It is obvious that an empowering dialogue between a university and society can only be established in a setting where the academic community and the general public are close, in other words in the regional setting. By mutually influencing each other, the university and its regional stakeholders jointly constitute an ‘organizing context’ whose members, the university as well as the business community and further constituencies, jointly create their own development conditions (Johannisson, Ramirez-Pasillas, and Karlsson Citation2002).

By combining its legitimacy as a member of the global research community and encouraging its staff to, locally and regionally, operate as academic entrepreneurs, a university makes a considerable and sustainable contribution to society. Such a ‘glocal’ perspective must, however, be reinforced by strong mutual trust relationship between the university and its regional stakeholders. The latter must accept critical research and the former has to be keenly aware of the needs of the region.

The abdication from a strong belief in objectivity and distance to the phenomena being studied in social research in general, and inquiry into entrepreneurship as practice in particular, calls for mindfulness and a catharsis on the part of the traditional academic. Wacquant’s (Citation2015) vision of more productive research into social phenomena invites a more dedicated and lasting inquiry into entrepreneurship. The respectful and assiduous personal learning process reported here, beginning with a hybrid between observant participation and participant observation and ending with enactive research as proposed aligns with Wacquant’s call for ‘carnal’ knowledge when it comes to uncovering social phenomena: ‘[W]e need to foster long-term, intensive, even initiatory, forms of ethnographic involvement liable to allow the investigator to master in the first person, intus et in cute, the precursive schemata that make up the competent, diligent and appetent member of the universe under examination’. (Wacquant Citation2015, 4; italics in original). Only then will it be possible to balance, on one hand, the digitalization and dehumanization of the world itself and, on the other, the unrestrained exploitation of digital databases that shamelessly offer boundless ‘facts’ to researchers who seldom leave their study and experience the world as it presents itself.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Becattini, G., M. Bellandi, and L. De Propris, eds. 2009. Handbook of Industrial Districts. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Berglund, K., A. Alexandersson, M. Jogmark, and M. Tillmar. 2021. “An Alternative Entrepreneurial University?” In A Research Agenda for the Entrepreneurial University. Elgar Research Agendas, edited by U. Hytti, 7–28. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Berglund, K., B. Johannisson, and B. Schwartz, eds. 2012. Societal Entrepreneurship – Positioning, Penetrating, Promoting. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, Ma, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bispo, M.D.S., and A. Gherardi. 2019. “Flesh.and-blood Knowing. Interpreting Qualitative Data through Embodied Practice-based Research.” RAUSP Management Journal 54 (4): 371–383. doi:10.1108/RAUSP-04-2019-0066.

- Czarniawska, B. 2007. Shadowing and Other Techniques for Doing Fieldwork in Modern Societies. Malmö, Sweden: Liber.

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B., and R Wolff. 1991. “Leaders, Managers, Entrepreneurs on and off the Organizational Stage“”. Organization Studies 12 (4): 529–546. doi:10.1177/017084069101200404.

- Ellis, C., T.E. Adams, and A. P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnographay: An Overview.” Historical Social Research 36 (4): 273–290.

- Ellis, C., and A. Bochner. 2000. “Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 733–768. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications.

- Eriksson, P., U. Hytti, K. Komulainen, T. Montonen, and P. Siivonen, eds. 2021. New Movements in Academic Entrepreneurship. Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA. USA: Edward Elgar.

- Fayolle, A., and D. Redford, eds. 2014. Handbook on the Entrepreneurial University. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Feldman, M., and P. Desrochers. 2003. “Research Universities and Local Economic Development: Lessons from the History of the Johns Hopkins University.” Industry and Innovation 10 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1080/1366271032000068078.

- Feldman, M., and W. Orlikowski. 2011. “Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1240–1253. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0612.

- Foss, L., and D. Gibson, edited by. 2015. “The Entrepreneurial University.” In Context and Institutional Change. London, UK: Routledge.

- Gabrielsson, J., G. Hägg, H. Landström, and D. Politis. 2020. “Connecting the past with the Present: The Development of Research on Pedagogy in Entrepreneurial Education.” Education + Training 62 (9): 1061–1086. published online ahead-of-print 10.1108/ET-11-2019-0265

- Goodheart, S. 2020. Head, Hand, Heart. Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Hägg, G. 2017. “Experiential Entrepreneurship Education. Reflective Thinking as a Counterbalance to Action for Developing Entrepreneurial Knowledge.” Dissertation. Lund: Lund University.

- Hayano, D. M. 1979. “”Auto-Ethnography: Paradigms. Problems and Prospects.” Human Society: Journal of the Society for Applied Anthropology 38 (1): 99–104.

- Hjorth, D. 2011. “On Provocation, Education and Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (1–2): 49–63. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.540411.

- Holland, J., R. Thomson, and S. Henderson. 2006. “Qualitative Longitudinal Research: A Discussion Paper.” London, UK: South Bank University.

- Hytti, U., ed. 2021. A Research Agenda for the Entrepreneurial University. Elgar Research Agendas. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Jeffrey, B., and G. Troman. 2004. “Time for Ethnography.” British Educational Research Journal 30 (4): 535–548. doi:10.1080/0141192042000237220.

- Joas, H. 1996. The Creativity of Action. Cambridge, UK and Malden, MA, USA: Polity Press.

- Johannisson, B. 1991. “University Training for Entrepreneurship: Swedish Approaches.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 3 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1080/08985629100000005.

- Johannisson, B. 2011. “Towards a Practice Theory of Entrepreneuring.” Small Business Economics 36 (2): 135–150. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9212-8.

- Johannisson, B. 2018. Disclosing Entrepreneurhip as Practice. The Enactive Approach. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Johannisson, B., O. Alexanderson, K. Nowicki, and K. Senneseth. 1994. “Beyond Anarchy and Organization: Entrepreneurs in Contextual Networks.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 6 (4): 329–356. doi:10.1080/08985629400000020.

- Johannisson, B., L. C. Caffarena, F. D. Cruz, M. Epure, E. M. Pérez, M. Kapelko, K. Murdock, et al. 2007. “Interstanding the Industrial District - Contrasting Conceptual Images as a Road to Insight.” Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 19 (6): 527–554. doi:10.1080/08985620701671882.

- Johannisson, B., and A. Nilsson. 1989. “Community Entrepreneurship – Networking for Local Development.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 1 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/08985628900000002.

- Johannisson, B., M. Ramirez-Pasillas, and G. Karlsson. 2002. “Institutional Embeddedness of Inter-Firm Networks: A Leverage for Business Creation.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 14 (4): 297–315. doi:10.1080/08985620210142020.

- Kisafalvi, V. 2002. “The Entrepreneur’s Character,Life Issues and Strategy Making: A Field Study.” Journal of Business Venturing 17 (5): 489–518. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00075-1.

- Marginson, S. 2014. “University Rankings and Social Science.” European Journal of Education 49 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1111/ejed.12061.

- Mars, M., J. L. Bronstein, and R.F. Lusch. 2012. “The Value of Metaphor: Organizations and Metaphors.” Organizational Dynamics 41 (4): 271–280. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.08.002.

- Rosa, H. 2020. The Uncontrollability of the World. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Sadler-Smith, E. 2015. “Wallas’ Four-Stage Model of the Creative Process: More than Meets the Eye?” Creativity Research Journal 27 (4): 342–352. doi:10.1080/10400419.2015.1087277.

- Sam, C., and P. van der Sijde. 2014. “Understanding the Concept of the Entrepreneurial University from the Perspective of Higher Education Models.” Higher Education 68 (6): 891–908. doi:10.1007/s10734-014-9750-0.

- Schatzki, T., K. Knorr Cetina, and E. von Savigny, eds. 2001. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. London: Routledge.

- Schumpeter, J. A. 1943l987. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Sixth ed. London, UK: Unwin.

- Seim, J. 2021. “Participant Observation, Observant Participation and Hybrid Ethnography.” Sociological Methods & Research 1–32.

- Steyaert, C. 1997. “A Qualitative Methodology for Process Studies of Entrepreneurship.” International Studies of Management and Organization 27 (3): 13–33. doi:10.1080/00208825.1997.11656711.

- Steyaert, C. 2007. “Entrepreneuring as A Conceptual Attractor? A Review of Process Theories in 20 Years of Entrepreneurship Studies.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 19 (6): 453–477. doi:10.1080/08985620701671759.

- Steyaert, C. 2011. “Entrepreneurship as In(ter)vention: Reconsidering the Conceptual Politics of Method in Entrepreneurship Studies.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 23 (1–2): 77–88. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.540416.

- Thanem, T., and D. Knights. 2019. Embodied Research Methods. London, UK: Sage.

- Van Maanen, J. 2011. Tales of the Field. On Writing Ethnography. Second ed. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

- Verduijn, K., and I. Sabelis. 2021. “The Societally Entrepreneurial University.” In A Research Agenda for the Entrepreneurial University. Elgar Research Agendas, edited by U. Hytti, 29–42. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wacquant, L. 2015. “For a Sociology of Flesh and Blood.” Qualitative Sociology 38 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11133-014-9291-y.

- Wallas, G. 1926. The Art of Thought. London, UK: Jonathan Cape.

- Welter, F. 2019. Entrepreneurship and Context. Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Wigren, C. 2003. The Spirit of Gnosjö. The Grand Narrative and Beyond. Dissertation. Jönköping: Jönköping International Business School.