ABSTRACT

This article presents a Quality Checklist for Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) education. The Checklist is a tool for teachers and educational developers in RCR education containing the results of eleven reviews on the impact of RCR education. It makes these data accessible in a layered way, such that users can quickly find the information that they are interested in. The tool can complement the Predictive Modeling Tool , which allows users to fill out information about a course and provides recommendations on how the course’s efficacy can be improved. We present our approach to developing the Quality Checklist prototype tool, the tool itself and how it can be used. We compare it to the PMT and discuss the added value of the Quality Checklist prototype tool, as well as its limitations. Finally, we indicate some of the ways in which the prototype tool could be further improved.

Introduction

Responsible conduct of research (RCR) trainings and courses have been offered since the early 1990s in order to “promote the accuracy and objectivity of research, collaboration among scientists, public support for research, and respect for research subjects” (Antes and DuBois Citation2014). Since the introduction of responsible conduct of research in the education curriculum, attempts haven been made to determine the impact of such courses in practice (Kalichman Citation2013; Salas et al. Citation2012). For more than 10 years, reports on the impact of RCR education have been published, yet it is not clear to educators which components positively influence the impact of RCR education on the practice of research (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Citation2017). From a practical point of view, the more information is available on what can promote the efficacy of RCR education, the better one can take these lessons into account in developing, assessing and/or improving specific educational practices. However, the large number of potentially relevant outcomes can be overwhelming. To that purpose, creating tools for making the available evidence accessible and manageable, would be welcome. This article presents the development of a Quality Checklist for RCR education as a tool that could fit this purpose. The Checklist includes the results from eleven reviews on the efficacy of education for RCR. The Checklist presents the available evidence in a layered and interactive way, allowing users to navigate between the main lessons from the reviews, on the one hand, and underlying details and variation that could be relevant given the specifics of the local educational practice, on the other hand. As such, it is a “checklist” in a specific sense – it contains detailed lists of characteristics, deriving from the literature, that have proven to contribute to the efficacy of RCR education. The existing evidence, as collected in the Checklist, can be checked to inform decisions about how to design, improve and/or assess one’s own RCR courses.

Currenty, one alternative tool is available, namely the Predictive Modeling Tool (PMT) as developed by Mulhearn et al. (Citation2017) The PMT is a sophisticated tool that can be used to develop, assess and improve education for RCR. While acknowledging the strengths of the PMT, we think there are good reasons to want to complement it. The Quality Checklist could serve that purpose.

Outline

The set-up of this article is as follows. We first present the aims and main characteristics of the PMT. To the best of our knowledge the PMT is the most elaborate and systematic evidence-based tool on offer to design, assess, and improve RCR education. In Section 2 we argue why we think there is a need for additional tools to complement the PMT, and in Section 3 we present the method we used to construe the Checklist. Having introduced the Checklist and how it can be used (Section 4), we show that it can indeed complement the PMT in important respects (Section 5). Finally, in the Discussion section (Section 6), we briefly summarize the main conclusions, discuss the limitations of the checklist, and indicate how it could be further improved.

The Predictive Modeling Tool

Mulhearn et al. have developed and validated a “Predictive Modeling Tool” (PMT) for RCR education (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017).Footnote1 The aims of the tool are ambitious, namely to design, assess as well as improve education for the Responsible Conduct of Research. The PMT was part of a larger project, involving and building on carefully organized meta-studies on the efficacy of education for RCR (Watts et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b). This resulted in a list of 77 variables or performance indicators for RCR education. The final 27 studies used in the validation of the PMT derive from the following disciplinary fields: biomedical (17), engineering (5), social sciences (3), and mixed (2) (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017). These studies are used as a baseline against which users of the PMT can assess their own courses (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 204). In brief, the tool allows users to enter the characteristics of an RCR course, by answering brief questions and scoring the course characteristics on a range of scales. The course characteristics cover eight broad categories: development, content, processes, delivery, trainer characteristics, trainee characteristics, criterion development, and criterion measures (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 197). Criterion measures refer to what is assessed in a course, like e.g., knowledge, ethical awareness, moral reasoning, strategies, perceptions of self, abstract thinking, moral judgment, and ethical decision-making (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 205).

Based on the input from users regarding the performance indicators, the PMT provides an overall score for the course, as well as more detailed scores for individual performance categories (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 199). In addition, it provides recommendations on how the effectiveness of that course can be improved. According to the authors, the effectiveness of a course can often be greatly improved by making only a small number of changes. By way of illustration, a recommendation might be:

Consider increasing the extent to which trainees are asked to think about emotions in decision making. For example, trainees may be instructed on how emotions can impact ethical decision making. Alternatively, trainees may be asked to reflect on their emotions in reaction to a certain ethical situation. (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 201)

Strengths

An obvious strength of this PMT model is that the tool can be used both by developers of new courses, but can also be used to appraise and refine existing courses. The usability of the PMT is stimulated in two ways. First, while the sheer number of variables (77) to be scored by users might seem overwhelming at first, the message that changes to a small number of variables could greatly improve the effectiveness of a course (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 201), can be generally reassuring to users. Furthermore, the PMT accounts for the real possibility that users might not have all the necessary information to score all variables. It does so by automatically assigning a rating when no information on a specific variable is offered (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017,198).

Need for an alternative

For teachers and educational developers, the PMT can play an important role in evidence-based attempts to improve RCR education. The PMT is, to our knowledge, the first tool created for that purpose. Yet, we decided to look for an alternative, which may possibly be complementary to the PMT. The need for an alternative for the PMT arose from the following reasons. Firstly, the PMT seems to equate the quality of courses with their effectiveness and thus mainly focuses on learning outcomes. For example, it does not ask users to provide information on which learning aims are central to a course: even though “criterion measures” are used to assess the effectiveness of the course under examination, such as knowledge, ethical decision-making and perceptions of self (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017, 197, 205). The use of specific criterion measures in the assessment of a course, however, does not necessarily provide information on which learning aims are central to that course. In other words, it is possible that the learning aims deviate from the measured outcomes, which could lead to mismatches between the learning aims that are central to a course and the criterion measures that are used to assess the efficacy of that course. For example, take a course that primarily aims to change behavior, yet also includes knowledge-related aspects. When assessing the course, it shows that knowledge has been effectively increased, but the behavior shows no effects. Such a course could score as “efficient” on “knowledge improvement” but would fail from a didactical perspective if that was not the core aim of the course. We think that this point is broader than the idea of constructive alignment, according to which it is relevant to align learning aims with learning tasks and learning assessment (Biggs Citation1996). In essence, we argue in later sections for a broader concept of quality of RCR education, in which quality is not solely determined by considerations of efficacy. We have collected a number of additional such considerations based on the reviews.

Second, and equally important, the PMT provides scores and recommendations for any course, the characteristics of which are filled-out in the PMT. By doing so, it hides from view (a) that it is based on studies from only a selection of scientific disciplines, and (b) that what works may differ between disciplines. For instance, we found that, whereas RCR education has a large positive effect on skills in engineering, it had a medium positive effect on skills in medical sciences, and a small positive effect on skills in social sciences, and in groups with mixed disciplines (Steele et al. Citation2016). Even though publications related to the development of the PMT consistently highlight as a limitation that the conclusions are based on studies from a selection of disciplines, and recommend caution with regard to interpreting the results, particularly with regard to generalizing the results to other domain (Mulhearn et al. Citation2017; Watts et al. Citation2017c), users of the PMT implicitly could conceive it as a generic tool, which provides them with a score for how effective their course is and how it can be improved.

Hence, some additional information seems relevant when designing and developing or adjusting one’s RCR courses. The PMT is valuable, but also limited. Therefore, we decided to develop a prototype that allows teachers and educational developers to find their way more easily in the bulk of information that is best applicable to their context. The next section describes our approach to developing the prototype of the Quality Checklist to complement the PMT.

Method

The task to come up with a helpful tool that aids teachers and educational developers in shaping their RCR courses is embedded in a European project, called H2020INTEGRITY (www.h2020integrity.eu), which aims to develop innovative tools for high school students, undergraduate students and early career researchers. We decided to search the literature for what is known about the positive impact of courses and trainings on participants, as measured by an increase in their knowledge, skills, attitude and behavior.

Web of Science. An additional targeted search was performed in the journal Research Ethics. Literature from the period 1990–2019 was searched using combinations of the following search terms: RCR, Responsible Conduct of Research, Research integrity, Research ethics, Questionable Research Practices, Integrity, Education, Teaching, Teaching method, Training, Students, Effectiveness, Assessment, Assessing, Evaluation, Criteria, Quality, and Qualities. The search was performed between 1 March–20 May 2019. This yielded a list of approximately 480 articles on the efficacy of RCR education, including eleven reviews, some of which were quite recent. Subsequently, we scored the literature. First, we performed scoring exercises to determine which of the articles where actually relevant for the purposes of our project. Two members of the project team independently scored the articles as either a ‘1ʹ (definitely relevant), ‘2 (might be relevant), or a ‘3ʹ (not relevant). Subsequently, we compared the scores, and discussed all results until we reached consensus. Yet, a closer look at the most recent reviews taught us that many of the articles that we included as relevant had already been included in these recent reviews. We therefore decided to use the results of the eleven recent reviews on the efficacy of RCR training (see ). The numbers [1] to [11] refer to the reviews used for the Quality Checklist. The consensus in the research group was to regard the results from the reviews as the primary evidence-base for the purposes of the quality checklist prototype.

Two internal workshops were organized with our consortium partner in the project in Zürich, to discuss whether we could use the PMT as a basis for our tool. Yet, after thorough examination of the PMT we decided to continue to develop a separate tool as Quality Checklist.

Quality – including and going beyond efficacy

A leading thought in our approach developing the Quality Checklist is that quality includes how effective the education is in promoting specific learning outcomes but is not solely determined by this criterion. We define effectiveness as “the extent to which observable improvements are made by trainees with regard to ethics-related knowledge, skills or attitudes” as a basis for RCR (Krom and Hoven vd Citation2020).

We formulated a number of additional criteria to capture important aspects of the quality of RCR education that are not directly related to efficacy (Textbox 1, Section 4) and should be taken into account when designing a course. These additional criteria also derive from the reviews and are related to e.g., insights shared in the discussion section (like “one size does not fit all”) and that seem highly relevant to take into consideration in addition to the criteria that were used to measure effectiveness. We decided that it is relevant to emphasize that the quality of a course cannot be limited to the effectiveness of a course and that this should be included in the Checklist. In developing quality criteria for our checklist for RCR education, we started with a basic and rough distinction between input, process, and output in a course context. In our categorization, Input refers to everything that proverbially feeds into the educational process (participants, learning aims and content, but also broader conditions like organizational support); Process refers to characteristics of actual educational activities (e.g., the delivery format and specific teaching methods); and Output refers to the assessment of RCR education (assessment criteria and the design of studies assessing RCR education). Subsequently, we took the categories that are commonly used in reviews to organize the results the data on the efficacy of RCR education and subsumed these under the general headings of (the quality of) input, process, and output. We decided to use a descriptive approach, in that the Quality Checklist describes the lessons on the efficacy of RCR education as they are presented in the reviews.

Introducing the Quality Checklist prototype

The result is an interactive Excel-file. It contains key insights from the scientific literature on what contributes to the efficacy of RCR education. The Checklist is meant for anyone interested in what could promote the quality and efficacy of RCR education, either as teacher, educational developer or educational manager. The Checklist is available at http://h2020integrity.eu/aboutus/documentation/.

It makes these data accessible in a layered way, such that users can find the information that they are interested in and that is relevant for their teaching context. This section describes the main characteristics of the Quality Checklist and how it can be used and gives a general indication of how to interpret the main results.

“Intro”

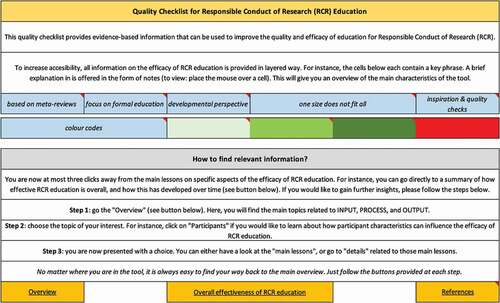

Opening the Quality Checklist, users are taken to the “Intro” page (see screenshot „Intro„ below). Here, users can find basic information about the Checklist: its main aim and key characteristics, how to find relevant information, and how quality is related to the efficacy of RCR education.

Key characteristics of the Quality Checklist

Key characteristics of the Checklist are that it is based on 11 reviews on the efficacy of RCR education, that it focuses on formal education (i.e., on courses), and that it takes a developmental perspective. The latter entails that, as far as possible, the main lessons on the efficacy of RCR education are connected to the educational or career stage of participants.

For each characteristic of the Checklist a brief explanation is available in a note, signaled by a comment triangle in the cell, that users can read by hovering over a box. For instance, the box “based on reviews” explains that the numbers between brackets (e.g., [1]) refer to a specific review. The list of reviews can be accessed via the “References” button (bottom-right). The “Intro” also contains several pointers related to how the insights and conclusions from the reviews can be interpreted. To start with, a key lesson is that one size does not fit all. This means that what is the most effective approach for RCR education, may differ depending on, among other things, what are the central aims of that course, and target groups. The checklist allows users to examine what is known about effective approaches for different target groups.

The added value of the Quality Checklist is that it allows users to perform basic quality checks on important aspects of RCR education that are relevant to their own course. The Checklist is a heuristic device, more than anything else, because studies on the efficacy of RCR education allow for conclusions about correlations between specific approaches and how effective these approaches are. They do not allow for conclusions about strict cause and effect, the use of causality-related terms notwithstanding (cf. the discussion or limitations sections of [1], [2], [3], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]).

To improve accessibility, color codes are used in the Quality Checklist. Green is used to signal positive effects related to certain characteristics of RCR education, red to signal negative effects or correlations. We only included statistically relevant effects. Results indicating that there was no significant negative or positive effect, have been left out of the Quality Checklist. In line with the scientific literature, we used three shades of green to indicate different sizes of positive effects. light green for a small positive effect to the most positive effect in dark green for a large positive effect. We used Cohen’s d-effects to differentiate between effects: small = .20, medium = 0.5 and large = .80. Finally, when presenting the main results on a certain topic, for instance the impact that participant characteristics may have on the efficacy of RCR education, we used the color gray to indicate what is the most effective, statistically speaking. This is because the exact effect sizes may differ, between studies and/or depending on, for instance, the scientific discipline.

How to find relevant information?

The “Intro” page also describes how users can find the information they are interested in. Information on how the overall efficacy of RCR education has developed over time is available directly by going to “Overall effectiveness of RCR education”.

The main lessons on each topic are available within three mouse clicks at most.

Step 1 is visiting the “Overview” page, where key topics related to the efficacy of RCR education are grouped under “INPUT”, “PROCESS”, and “OUTPUT”.

Step 2 is choosing a topic of the user’s interest. For every topic, this will take the user to a basic menu with two options. Users can either go directly to the “Main lessons” on how this topic is related to the efficacy of RCR education or have a look at the “Details” underlying and supporting the main lessons on that topic.

Step 3 is making a choice.

Finally, it is explained that each page of the Checklist contains shortcuts to the “Intro” and “Overview” pages, so users can move around quickly and easily.

This brief description indicates how the Checklist can be used in terms of process. By way of illustration, we will give an example of how the checklist can be used to inform e.g., a decision of what content to focus on in a specific RCR course. Information on how content can influence the efficacy of a course, can be accessed by visiting the “Overview” page, and clicking “Content”. Suppose you are a course developer and wondering whether you should include the use of RCR guidelines. Checking the main lessons in the section “Content”, you find that the use of some guidelines has shown a positive correlation with the overall efficacy of a course (e.g., guidelines on authorship practices, [9]), while the use of other guidelines has shown a negative correlation with the overall efficacy of a course (e.g., guidelines on collaboration, [9]). This information can subsequently be used to inform a decision on whether or not to include specific guidelines in a course. Now suppose our course developer considers that collaboration is an important topic to include, despite the negative correlation just mentioned. Other studies, after all (e.g., [8] show that addressing the topic of collaboration as such has a small positive effect on the overall efficacy of a course. Visiting the “Details” section provides support to think of ways to address the topic of collaboration, other than by means of guidelines. The Checklist helps the user to find more detailed information which could be helpful in developing courses.

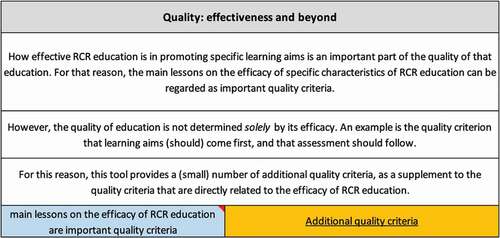

Two types of quality criteria: Effectiveness and beyond

The right-hand side of the “Intro” page describes how quality is related to the efficacy of RCR education (see „quality effectiveness and beyond„ below). Here, it is explained that the quality of RCR education is determined in part by how effective that education is in promoting specific learning aims but should not be reduced to that – for two reasons. First, what is considered important from a quality perspective might not always be easily measurable (including whether “improvements” in that respect have been achieved). Second, factors external to education for RCR might impact how effective education for RCR can be. Suppose that the impact of these external factors on the effectiveness of that course is negative. We think that it would be unfair to conclude that the educational activities in that reported course must be of poor quality.

The main lessons on how certain characteristics of RCR education may improve its efficacy are important quality criteria. The Checklist offers a number of additional quality criteria that go beyond how effective RCR education is in promoting specific learning outcomes (see Text box 1).

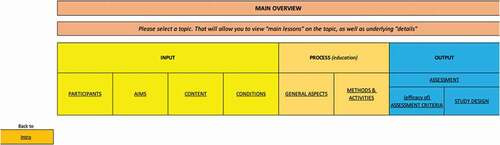

“Overview”

The “Overview” page (see : „main overview„ below) is a central part of the checklist. It contains an overview of key topics related to the efficacy of RCR education. These topics are grouped as being primarily related to INPUT (what is put into education), to PROCESS (the education itself), and OUTPUT (focusing on assessment of education). From this point on, users are two mouse clicks away from either the main lessons on how a topic is related to the efficacy of RCR education, or to more detailed information underlying those main lessons.

An example: “Impact on learning aims”

By way of illustration, we will now show what the page with the main lessons related to learning aims looks like, and how the results should be interpreted. Users can get there by first clicking on “AIMS” in the main “Overview” page. This will take them to the menu shown below ( „impact on learning aims„).

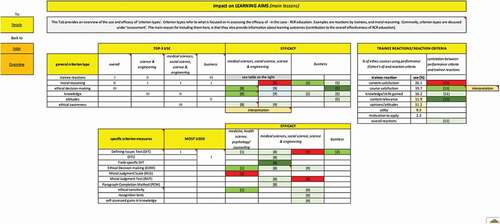

When choosing “Main lessons”, the following page will appear (see „ main lessons„ below). Notice that even when focusing on main lessons, some pages may still contain quite a lot of information. We will now explain how the page on the impact on learning aims can be read.

It is of key importance to determine to what extent RCR educational activities help promote specific learning aims, is of key importance. However, meta reviews do not offer a direct answer to that question. The closest that they come to this is by indicating to what extent different so-called “criterion types” contribute to the effectiveness of these courses. The remainder of the page “Impact on learning aims (main lessons)” indicates which criterion types are used most, and to what extent each criterion type contributes to the overall effectiveness of RCR education.

Most used criteria

To limit the amount of information the Checklist focuses on three criterion types that are used the most. As shows, this may differ between scientific disciplines. For instance, in general trainee reactions are the most-used way to evaluate RCR education, followed by moral reasoning and ethical decision-making (screenshot, top left). In science & engineering, however, moral reasoning is the most-used criterion to evaluate RCR education, followed by trainee reactions and, thirdly, knowledge. The top-3 may change again for other (combinations of) disciplines.

Tools that are used to assess the efficacy of RCR education are mentioned under “specific criterion measures” (, bottom left). The screenshot shows that (variations of) the Defining Issues Test (DIT) are among the most used specific criterion types.

Most effective criteria

The section “Main lessons” also contain information about which criterion types are the most effective. “Most effective” here means which criterion type contributes the most to the overall effectiveness of RCR education. Again, this may differ per academic discipline. Looking at general criterion types first, it seems that ethical decision-making and knowledge are more effective criterion types than ethical awareness. And knowledge, in turn, seems to be more effective than ethical decision-making. The latter conclusion does not become immediately clear by looking at the color codes: both knowledge and decision-making have the same color, corresponding to a medium or large positive effect. The general effect sizes “small,” “medium,” and “large” each leaves room for much variation, however. In this case Cohen’s d = .78 for knowledge, and .51 for ethical decision-making.

Which criterion type is the most effective is complicated by the different outcomes of various reviews. For instance, whereas knowledge and ethical decision-making have a medium positive effect according to review [8], there is a small positive correlation with overall efficacy according to review [9]. Both reviews use the same underlying studies. An important difference between the two reviews is that whereas [8] examines characteristics of RCR education in isolation, [9] modeled multiple characteristics simultaneously.

Conclusions on most used and most effective criteria

The Quality Checklist allows users to compare the criteria that are used most to the criteria that are most effective. For instance, ethical decision-making, a criterion with a medium positive effect in science & engineering according to review [8] is not in the top-3 of most used criteria in that domain. On the other hand, the criterion with the largest positive effect in that domain, knowledge, is third in the top-3 of most-used criterion types in that domain. The results also show that, as far as specific criterion measures go, different versions of the Defining Issues Test can have diverging effects, with a (small) negative correlation with the overall efficacy of a course for the standard DIT according to review [9] and a large positive effect for a field-specific DIT according to review [8].

These examples were an important impetus to include in the current Checklist prototype detailed information on which information form the basis for the main lessons and occasional notes on how specific conclusions should be interpreted. That way, the status of general conclusions remains visible, which to us seems important if they are to function as input for decisions on key aspects of educational activities in a variety of disciplines and target groups.

Trainee reactions

Lastly, the “Main lessons on the impact on learning aims” also contains a section on the use and efficacy of trainee reactions in the assessment of RCR education (top-right). Using trainee reactions for the assessment of RCR education means asking participants what they think about specific aspects of a given course. Review [11] focuses on trainee reactions and examines if specific type of trainee reactions shows a positive correlation with performance criteria (Cohen’s d). Interestingly, the most-used trainee reaction to assess RCR education – content satisfaction – shows a negative correlation with performance criteria. This means that if an evaluation shows that students are satisfied with the content of a course, this is not a sign of that course’s effectiveness. In other words, content satisfaction is not a good (indirect) measure for the efficacy of RCR education. This is different for the criteria “course satisfaction,” “knowledge/skills gained,” and “content relevance,” trainee reactions that are among the most used reaction measures, as these show a medium, weak and strong correlation with performance criteria [11]. In other words, these specific reaction measures could be useful in assessing the efficacy of RCR education, albeit in an indirect way.

This concludes our introduction of the Quality Checklist.

How can the Quality Checklist complement the Predictive Modeling Tool?

Our reasons to want to complement the PMT were twofold. The first was that the PMT defines the quality of courses in terms of their efficacy. It leaves out important insights of constructive alignment and does not consider that courses that show low effects could still be of high quality in other respects. We used additional criteria to broaden the scope of course quality. The Quality Checklist complements the PMT by explaining how criterion types contribute to the overall effectiveness of RCR education. This differs from having insights into how, for instance, specific teaching methods contribute to certain effect sizes related to specific learning aims. Additionally, the Quality Checklist incorporates as an explicit quality criterion that goals (objectives) come first, and that assessment should follow. This entails that:

Without clear delineation of the desired outcomes, measurement and interpretations of the outcomes regarding course effectiveness are not possible [3]. Also, the criterion type that is used to evaluate education must match the intended learning outcomes, Otherwise, important results from education might go unnoticed ([1]-[3], [5], [8], [11]). (See Text box 1).

This underscores the importance of always connecting explicit learning aims to the way in which a course is evaluated. While the studies underlying the PMT are consistent with this point, the PMT itself de facto hides this from view.

The second reason to want to complement the PMT is that it seems to provide scores and recommendations for any type of course. The PMT hides from view that it is based on studies from a selection of scientific disciplines, and that what works may differ significantly between disciplines. The Quality Checklist complements the PMT by explicitly distinguishing between disciplines and target groups. It does so by making explicit in the “References” tab which scientific disciplines are represented in the conclusions from the reviews, by indicating for each effect size on which review it is based, and by including and grouping the main lessons from all reviews as well as underlying details and potential differences. This way, users are reminded at all times about the contextuality of achieving certain effects and effect sizes.

Discussion

In the previous sections we have shown that the Quality Checklist prototype can complement the PMT in these regards, and how. In theory, the PMT could – in the future – be adapted in order to accommodate both points of crititicism that we put forward, and it is not our ambition to somehow replace the PMT with our Quality Checklist. The main purpose of our exercise is to be better able to distinguish between differences in disciplines and to broaden the scope of what we consider as quality in RCR education. That is why we emphasize the possible complementary role of the Checklist. Even though the Checklist is primarily developed to serve a European H2020 consortium in developing educational tools, we think that the Checklist can help fill the growing need to develop RCR courses upon knowledge that is already gained regarding what works and not. Our idea to present the Checklist to a broader audience is inspired by the current lack of opportunities to check the quality of an RCR course.

A number of limitations of the Quality Checklist should be mentioned. First, the use of Excel, or at least our use of Excel results in some limitations in terms of user-friendliness. This is due, in part, to including an admittedly large amount of data, and to the inclusion of explanatory comments to assist users in making sense of the data. Should the Checklist be further developed, options could be explored to further optimize the balance between completeness, on the one hand, and accessibility/user-friendliness on the other. For instance, it might be possible to turn the Quality Checklist into an app that also allows for additional ways to provide information in a layered and intuitive way.

Another limitation highlights the need to accommodate the previous one. It pertains to the (in)completeness of the Quality Checklist. There are several aspects to this. First, after the Checklist prototype had been developed and submitted to the European Commission as a deliverable, it came to our attention that there was an extra meta review, (Marusic et al. Citation2016) that did not show up in our literature search (see Section 3). It falls outside the scope of this article to reflect on any implications that including the additional meta review may have for the Quality Checklist. It does touch on the broader issue of (in)completeness, though. There are several ways in which the knowledge base of the Quality Checklist (and the PMT) can be expanded. For instance, information could be included about the efficacy of types of informal education such as mentoring and supervision, which will also have an impact on the extent to which intended learning outcomes can be achieved. Furthermore, by including studies on a broader range of participants may be included. For instance, none of the meta reviews included in the Quality Checklist (and the same holds for the PMT) included conclusions on the efficacy of RCR education for high school students. Likewise, the knowledge base of the Quality Checklist (and the PMT) can be further expanded by including studies from more disciplines. To give just one example, none of the meta reviews included in the Quality Checklist (and the same holds for the PMT) involved conclusions about the efficacy of RCR in the humanities.

Another (potential) limitation relates to the use of color codes. Using color codes for different effect sizes has the advantage of increasing the accessibility of the Checklist. A potential disadvantage, though, is less precision. That can take two forms. First, the same characteristic may have an effect size of 0,49 according to one study, and 0,51 according to another study. In the Quality Checklist, these effect sizes would receive a different shade of green. Second, one and the same characteristic may have an effect size of 0,51 according to one study, and 0,79 according to another study. In the Quality Checklist, these effect sizes would receive the same shade of green. Fortunately, these examples are rare. By including a comment that becomes visible if users hover over it, we have tried to balance the accessibility of the Checklist, with the loss of precision.

Finally, unlike the PMT, the Quality Checklist does not provide specific recommendations. Instead, it positions the outcomes of the meta reviews as inspiration, and it offers more detailed information to show some of the additional conditionality that can be involved in promoting the efficacy of RCR education. We imagine that some users may consider this a disadvantage, because it increases complexity and offers less clear guidance. Viewing the Quality Checklist as complementary to the PMT, this need not be problematic, since it opens up a range of possibilities with regard to how users can make use of the two tools in different degrees, depending on what best fits their needs.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Johannes Katsarov, Roberto Andorno, Hanneke Mol, Orsolya Varga, Carline Klijnman, Marcell Várkonyi, Lucas van Amstel and consortium members for comments and suggestions related to the Quality Checklist. Thanks to prof. Mumford c.s. for sending the Excel file of the Predictive Modeling Tool (PMT) and guideline for using the PMT.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Prof. Mumford (University of Oklahoma) has been so kind to send us the actual PMT upon request, as well as the PMT manual and a Walkthrough Example, allowing us to attain some additional insights in how the PMT works. The discussion of the PMT in this article only refers to aspects of the PMT that are publicly available.

References

- Antes, A. L., and J. M. DuBois. 2014. “Aligning Objectives and Assessment in Responsible Conduct of Research Instruction.” Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education 15, December: 108–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.c15i2.852.

- Biggs, J. 1996. “Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment.” Higher Education 32: 347–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871.

- Kalichman, M. K. 2013. “A Brief History of RCR Education.” Accountability in Research 20 (5): 380–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822260.

- Krom, A., and M. A. Hoven vd. 2020. “Report on Developing a Quality Checklist for RCR Education (Protype Tool).” www.h2020integrity.eu

- Marusic, A., E. Wager, A. Utrobicic, H. R. Rothstein, and D. Sambunjak. 2016. “Interventions to Prevent Misconduct and Promote Integrity in Research and Publication.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4 (MR000038). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

- Mulhearn, T. J., L. L. Watts, E. M. Todd, K. E. Medeiros, S. Connelly, and M. D. Mumford. 2017. “Validation and Use of a Predictive Modeling Tool: Employing Scientific Findings to Improve Responsible Conduct of Research Education.” Accountability in Research 24 (4): 195–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2016.1274886.

- National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. 2017. Fostering Integrity in Research. National Academy Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.17226/21896.

- Salas, E., S. I. Tannenbaum, K. Kraiger, and K. A. Smith-Jentsch. 2012. “The Science of Training and Development in Organizations:What Matters in Practice.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13 (2): 74–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612436661.

- Steele, L. M., T. J. Mulhearn, K. E. Medeiros, L. L. Watts, S. Connelly, and M. D. Mumford. 2016. “How Do We Know What Works? A Review and Critique of Current Practices in Ethics Training Evaluation.” Accountability in Research 23 (6): 319–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1182025.

- Watts, L. L., K. E. Medeiros, T. J. Mulhearn, L. M. Steele, S. Connelly, and M. D. Mumford. 2017a. “Are Ethics Training Programs Improving? A Meta-Analytic Review of past and Present Ethics Instruction in the Sciences.” Ethics and Behavior 27 (5): 351–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1182025.

- Watts, L. L., T. J. Mulhearn, K. E. Medeiros, L. M. Steele, S. Connelly, and M. D. Mumford. 2017b. “Modeling the Instructional Effectiveness of Responsible Conduct of Research Education: A Meta-Analytic Path-Analysis.” Ethics and Behavior 27 (8): 632–650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1247354.

- Watts, L. L., J. Tyler, T. J. Mulhearn, K. E. Medeiros, L. M. Steele, S. Connelly, and M. D. Mumford. 2017c. “Modeling the Instructional Effectiveness of Responsible Conduct of Research Education: A Meta-Analytic Path-Analysis.” Ethics and Behavior 27 (8): 632–650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1247354.