ABSTRACT

Predatory publishing has recently emerged as a menace in academia. University professors and researchers often exploit this practice for their economic gains and institutional prestige. The present study investigates such existing predatory publishing practices in Pakistani public sector universities drawing on the notion of symbolic violence. For this purpose, we analyzed 495 articles published by 50 university professors in the social sciences and humanities over the period 2017–2021. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with 20 postgraduate students to gather their perspectives on publishing practices. The study shows that 69% of the sample papers were published in predatory journals, as identified in Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission’s (HEC) online journal recognition system (HJRS). Postgraduate students’ insights inform the study that the students misrecognize these malpractices in academia as a problem what is referred to as “symbolic violence.” Consequently, they engage in the process to increase their publications. Such publications enable both the university professors and the students to achieve the desired benefit, such as promotions, tenure, and academic degrees. We recommend that this practice must be altered at the policy level since it not only violates the HEC’s standards for quality research but also damages the researchers’ credibility and country’s scientific reputation.

1. Introduction

Predatory publishing has emerged as a serious concern in the academic publishing as it threatens the integrity of science and publication practices globally. In the 1980s, the publishing industry saw a shift from closed access to open access publishing, which enabled global access to the latest research (Mills and Inouye Citation2021). In line with reputable journals, pay-to-publish journals also appeared and published scholarly work without ensuring the quality of the research (Ebadi & Zamani, Citation2018). The term predatory journal was coined by American academic, researcher, and librarian Jeffrey Beall in 2008 to describe journals that emphasize profit over quality of research and publish articles for a fee without substantial peer review. Others have called predatory journals “questionable,” “hijacked,” “fake,” and “false” (Mills and Inouye Citation2021) and “bogus,” “pseudo,” “deceptive,” “sham,” “dubious,” “low credibility” and “scholarly bad faith journals” (Berger Citation2017). The primary purpose of predatory publishing is to make a profit rather than contribute to the advancement of knowledge (Beall Citation2012, Citation2014; Demir Citation2018; Negahdary Citation2017). Predatory open access journals (POAJs) violate peer review and quality control (Dadkhah, Mohammad, and Borchardt Citation2017). Thus, papers in such journals are considered junk science for citations (Memon Citation2018) as well as deceptive entities (Eriksson and Helgesson Citation2017). An in-depth look at this academic crime reveals the power and grab tactics used by the publishers to attract the writers by providing an easy and quick way to publish their work through e-mails (Butler Citation2013; Kozak, Lefremova, and Hartlye Citation2016). In 2015, Shen and Bjork reported that more than half a million articles were published in predatory open access journals (POAJs).

In the backdrop of the scholarly criticism on predatory publishing as a global trend, the present study is conceptualized to investigate prevalent malpractices of predatory publishing in Pakistan using Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) concept of “symbolic violence” as a theoretical lens. The concept of symbolic violence is useful when attempting to understand dominance, exploitation, and subordination in educational practices (Ebadi and Zamani, Citation2018, 26). According to Bourdieu, the educational system is one of the main agents of symbolic violence (Bourdieu, ibid). Pakistan is chosen as a context for the present study because: a) the country has a historical significance in the South Asian region for its colonial roots reflected in the educational and research policies; it promotes academic publishing as a significant part of national research policy devised by Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan for the recruitment and promotion of the university teachers b) the present authors are affiliated with Pakistani universities that deepens their understanding of predatory publication practices in Pakistan exploited as a means to earn unfair promotions and tenures. Thus, the authors of the study tend to inform the readers both at a national and global level by delving deeper into the issue to see the way it works and gets legitimized at a wider scale in the country. In this study, we have used two datasets: a) a corpus of research articles published by university professors in national and international journals over the period of 2017–2021, and b) semi-structured interviews with postgraduate students to know their views regarding publishing practices at Pakistani public sector universities. For this purpose, we begin with a scholarly review of the predatory as a global phenomenon and theoretical framework of Symbolic violence as proposed by Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1991) followed by the methodological procedures. We then present our results and discussion. Lastly, we propose suggestions to ensure quality research at Pakistani universities considering the institutional structure of the country.

2. Literature review

Predatory publishing is on the rise globally (see Omobowale et al. Citation2014; Shehata and Elgllab Citation2018; Atiso, Kammer, and Bossaller Citation2019; Demir Citation2018; Chavarro, Tang, and Ràfols Citation2017; Ebadi and Gerannaz Citation2018). According to Cobey et al. (Citation2018), predatory publications are common in most journals published in India, the United States, and Ethiopia. Earlier studies have indicated that most individuals who publish in predatory journals are from the Global South, especially India, China, and Africa. Approximately three quarters of predatory publications are produced by African or Asian authors as noted by Shen and Björk (Citation2015). Xia et al. (Citation2015) identified four geographical regions with “predatory” publishers (Nigeria, India, UK, and USA), but noted that most researchers were young and inexperienced. Most predatory journals victimize naive researchers who submit their research to them and have regrettable realizations afterward. Some experienced authors, however, use predatory publications to enhance their CVs (Pond et al. Citation2019). According to Torres (Citation2022), predatory journals and publishers pursue self-interest at the expense of scholarship, provide misleading or false information, ignore standard editorial and publication practices, and engage in aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices that are antithetical to ethical conduct. According to Dinis-Oliveira (Citation2021), scientists receive nearly every day e-mails inviting them to publish in predatory open access journals (POAJs) that do not pertain to their field.

This phenomenon of predatory publishing is also evident in the Pakistani academia. During a public program in Pakistan, Dr Parvez Hoodbhoy, a leading Pakistani physicist, remarked that in the past, publishing 12 papers was considered a big accomplishment, but now academics publish 100s of papers in a short period of time. As a result of publishing substandard research papers, academics and students who take part in quality research are discouraged. These practices devalue Pakistan’s research standards. Masood (Citation2018) highlights that universities are constantly battling for quality in research and teaching through the Higher Education Commission, which funds and regulates them. It is continually exposing academics committing plagiarism – including members of its own staff – and closed 57 PhD and master’s degree programs two years ago due to concerns about quality. Kumari, Babur, and Siddiqui (Citation2017) note that the issue of research culture and research performance/productivity cannot be seen in isolation without examining the nature and quality of the research education being provided by higher education institutions. Memon (Citation2018) noted an increasing trend in predatory publishing that follows “fast review procedures without transparency.” In a recent study by Machacek and Srholec (Citation2021), Pakistan ranked 17 out of 20 OIC countries in predatory publishing, with 20 being the worst ranking. Khan (Citation2021) argues that in the past, it was the lack of financial resources that were held responsible for the backwardness of the Muslim world in science; recently, with the increase in funding coming from governments and national bodies, the OIC countries have had little impact on science and research. It is happening as more papers are published in non-peer reviewed “predatory journals.”

3. Bourdieu’s concept of “symbolic violence”

Bourdieu (Citation1991) describes symbolic power as an invisible force used in everyday social life and is recognized as a “legitimate practice.” The importance of the symbolic power can be seen in its ability to impose reality construction mechanisms on others. This power exercises a “symbolic violence,” which refers to the process of justifying social conventions by naturalizing them in the social structures. Sapiro (in Wright, Citation2015, 781) notes three components through which the symbolic violence functions: ignorance of the arbitrariness of the domination; recognition of this domination as legitimate; internalization of the domination by the dominated. Walther (Citation2014) notes that the symbolic violence results from a power tension in which those with symbolic capital use power against the agents possessing a low amount of capital only to exert a control over them. According to Bourdieu, in contemporary advanced capitalist societies, the symbolic violence is becoming more significant, and the social hierarchies and inequalities are produced and maintained less by physical force than the forms of symbolic violence. The results of the domination are referred to as “symbolic violence” (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992a, 15). Violence is a result of our misrecognition of the systems of classification as natural that are culturally arbitrary and historical.

Symbolic violence is a generally invisible form of violence. In this case, those who dominate do not need more force to control people to maintain social hierarchy. In Bourdieu’s words, “let the system they dominate take its own course in order to exercise their domination” (Bourdieu Citation1977, 190). To put it in other words, this form of violence produces a social structure, in which both the dominant and the dominated perceive these systems as legitimate, and thus, think and act in their own best interests (Schubert in Grenfell, et al, Citation2008, 184). Symbolic violence, is thus, a more effective and brutal means of oppression (Bourdieu in Bourdieu and Eagleton Citation1992e, 115). According to Bourdieu & Wacquant (Citation1992a, 167), those who suffer from “symbolic violence” are usually willing and interested participants in the systems that harms them. According to him, symbolic violence occurs through symbolic systems existing in the culture which shape the reality (Bourdieu Citation1991). In this sense, the institutions and universities with symbolic power do engage in building a representation of the reality by enforcing existing publishing practices as a “reality.” In order to combat this symbolic violence exercised through unfair and unjust practices, it is thus necessary to identify the symbolic acts in a culture and expose it as illegitimate.

Bourdieu’s symbolic violence helps the present researchers to have a critical insight into the ways the predatory publishing is naturalized and deemed “legitimate” at the public sector universities in Pakistan. This conceptual and analytic tool informs the study to problematize such frequently occurring publications, which facilitate the predatory publishing industry affecting the academic integrity and reputation of disciplines in relation to the global research standards. In Wiegmann’s (Citation2017) words, Bourdieu’s theoretical tools like symbolic power and the violence it symbolizes are helpful in highlighting the power relations operating within a social practice.

4. The present study

The present inquiry draws on the notion of symbolic violence in academic publishing primarily used in the work carried out by Ebadi and Zamani (Citation2018) who employed two theoretical lenses: Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) symbolic violence and Critical English for academic purposes (CEAP) to demonstrate the factors contributing to an increase in predatory publications by higher education students in Iran. They explored students’ perceptions through a survey administered at four domestic universities in Iran. Our study, however, situated in the Pakistani context, examines evidence of articles published in the predatory journals by professors at public universities in the social sciences and humanities. In addition to the corpus of articles, we conducted an in-depth semi-structured interview with postgraduate students to learn how they perceive on-going publishing practices. The postgraduate students’ views were interpreted using Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) symbolic violence to understand the mechanism involving predatory publications and the way symbolic violence operates through it and other factors. Therefore, our study extends the debate on symbolic violence in academic publishing taking Pakistan as a case study.

As part of our investigation into predatory publishing practices in Pakistani academia, we attempted to answer the following questions:

What is the prevalence of predatory publishing among social science researchers in Pakistan?

What are postgraduate researchers’ views about publishing practices at public sector universities in Pakistan?

4.1 Research policy in Pakistan

Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan has consistently worked to raise the standards of research since 2005. For this purpose, it facilitates national research journals published by registered entities (universities or departments of faculties of such entities or registered research institutions or nonprofit academic societies with a mandate for research) through financial support and capacity building to enhance their academic and publication standards (Kumari, Babur, and Siddiqui Citation2017). To ensure the quality of research output, the HEC had previously classified research journals into four categories, namely W, X, Y, and Z, with “W” being the highest and “Z” being the lowest standard. With the introduction of the Higher Education Journal Recognition System (HJRS), a newly developed online system for the accreditation of journals, the HEC has removed “Z” category, which means that publication in any of research journals in that category would have no benefit for the author (see Yousufzai Citation2021).

With the revised system that was fully implemented in July 2020, the HEC, however, recognizes only research journals in the W, X and Y categories. In addition, the HEC claims that it will evaluate the journals’ quality by using internationally acknowledged parameters. In a public notification issued on 5 November 2019, HEC released revised guidelines to ensure the quality of both national and international research publications (see for description of each category of journal).

Table 1. Description of HEC journals’ each category.

The journals belonging to the category “W” have the highest standard, whereas those in category “Y” meet the minimum standard for being recognized by the HEC according to the new policy. HEC has connected Pakistan’s research journals with international impact factor companies, abstract and citation databases of Elsevier’s Scopus, and Clarivate Analytics’ Journal Citation Reports through its newly designed online platform – the HJRS which was launched in 2020. The HJRS is designed to:

create such a “recognition and reward ecosystem” where “high quality research” is rewarded and promoted

help HEC, funding agencies and Policy makers to objectively evaluate the prestige of a journal, in a given subject area, and make informed decisions about the prestige of journals where faculty members typically publish

recognize, with high degree of accuracy within the community of researchers, those researchers who aim for the prestigious journals because they are doing world class research

finally, act as a policy instrument to distinguish “quality-centric researchers” from the herd

(Source: https://hjrs.hec.gov.pk/)

According to the HEC policy discussed on its official website, the selection criteria for university recruitment process include 10 research articles with at least 4 publications in the last five years for associate professor, and 15 research papers with at least 5 publications in the last 5 years in HEC recognized journals for full professor besides a PhD and 10 and 15 years of relevant teaching/research experience in HEIs respectively. Moreover, for award of a PhD degree, HEC requires PhD researchers to publish one research article as the first author during their doctoral studies in an HEC recognized “Y” category (or above) journal.

4.2 Corpus for the present study

The study corpus consists of research articles written by university professors within social sciences and humanities at public sector universities in Pakistan (see ). The present researchers restricted their analysis to the last five years’ (i.e., 2017–2021) publications produced by university professors in social sciences and humanities across the country. There are four provinces in Pakistan: Sindh, Punjab, Baluchistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. We considered one public sector university in each province of the country in addition to one university from Islamabad – the capital city of Pakistan. A sample of fifty university professors was chosen randomly. Five university professors, one from each social sciences and humanities discipline at the selected universities across the country was included in the study. We initially gathered the universities’ information through HEC’s official website to ensure the degree awarding programs, specifically masters and PhD in social sciences and humanities. Based on the given information, we selected the universities that award masters and PhD degrees and searched the profiles for the academic staff. As a part of our criteria, we selected a full-time professor for our study.

Table 2. Corpus of the research articles.

To trace the articles written by the selected professors, we referred to academic research sharing forums, such as Google Scholar, Research Gate, Academia, and Semantics Scholar, to gather samples of research articles published by each university professor selected in the study. We prepared an excel sheet for published articles with journals’ names and location, authors’ details, and year of publication for all fields under study. Due to the strict ethical protocols, we have concealed the identity of institutions and participants. Research articles were evaluated using HJRS – an online recognition system developed by HEC, Pakistan. The HJRS helped the present authors to identify the journals as recognized by the system. On the contrary, those journals and published articles that were not recognized by the HJRS were labeled as “predatory” in the present study following the HEC’s guidelines. The corpus of the articles was analyzed using SPSS to calculate the simple frequency of articles published in predatory and HEC recognized journals and also create a graph to show the highest tendency of predatory publication in several disciplines.

4.3. The interviews

A semi-structured interview was conducted with 20 postgraduate researchers, two from each field of study, studying in master’s degree programs at the same public universities in Pakistan where the sample of articles written by the professors was chosen. We first purposively selected postgraduate students, both male and female, and then used the snowball technique to recruit the interview participants. The least criterion for interview participants was the completion of coursework, initial defense seminar delivered on their research proposal and publication of at least one research article. The perception of postgraduate students in the study was necessary as their contribution to increasing the university professors’ academic publications has been noticed widely in Pakistani academic and public discourses. The present study argues that the professors exert a symbolic violence through such practices of publications by the students. Additionally, the authors’ own affiliation with the public sector universities in Pakistan tends to deepen their understanding about how postgraduate students contribute to increasing publication regardless of whether the publications appear in predatory journals.

Average interview duration was 20–25 minutes. In the interview, they were asked about their experiences publishing articles at public sector universities with their research supervisors. We transcribed and analyzed the interview data using Braun & Clark’s (Citation2006) thematic analysis technique, which helped us codify the in-depth interview data for analysis using Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) symbolic violence. However, in presenting our data, we have selected the excerpts to show their insights regarding the publishing practices. We triangulated the interview data with the corpus of articles to further validate our inquiry into predatory publishing practices, a symbol of violence in Pakistan. According to Natow (Citation2019), triangulation is one way to enhance the validity of a study when viewed from a post-positivist perspective. This is accomplished by utilizing a variety of methods, data sources, and researchers, as well as different data analysis methods. Using multiple data sources, methods, researchers or analysis techniques reduces the possibility of biases and inaccuracies.

5. Results

The findings of the study are presented in two sections. We first present the frequencies and percentages of the predatory publication according to the country’s own journal recognition system (i.e., HJRS) followed by the postgraduate students’ views about the academic publishing at public sector universities in Pakistan.

5.1 Predatory publication as a “research scam” in Pakistani academia

The findings of the study indicate that predatory publishing is a dominant trend in Pakistani academia, as evidenced in below. 69% of the articles published by professors in social sciences and humanities were identified in predatory journals. Many articles have been published both nationally and internationally by paying fees to the journals without ensuring that the quality standards are met.

Table 3. HEC recognized and predatory publications.

Of the 150 HEC recognized articles, the increasing trend can be seen in HEC’s “Y” category, whereas those published in HEC’s “W” and “X” categories stand significantly “low.” Most of the articles by university professors were coauthored with their colleagues as well as postgraduate students to comply with institutional policies and criteria for promotions and tenure. In this case, it appears that research supervision in master’s and PhD degree programs is a major contributor to this increase in predatory publications. And this happens because the institutional policies at some universities require the postgraduate students to publish articles as a part of their degree requirement. In this entire process, the predatory publishing industry takes the advantage by offering the easy and quick way to publish their work to meet the required standards set by the institutions. below summarizes the findings on each of the fields of social sciences and humanities at Public sector universities in Pakistan in terms of their recognition in HJRS and status as “predatory.” The data shows that 345 research articles across all fields are unrecognized in the HEC journal recognition system, thus being published in predatory journals.

Table 4. Field-wise recognized and predatory publications.

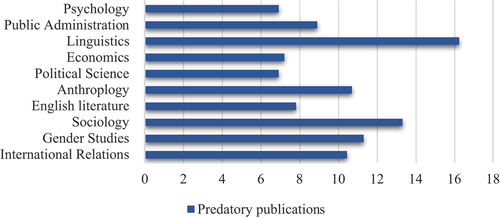

It is worth noting that predatory publications have become widespread at public universities in Pakistan across all disciplines of social sciences and humanities over the last several years. According to , the highest percentage of predatory journals was found in linguistics, with 16.23% followed by sociology, gender studies, anthropology and international relations with 13.3%, 11.3%, 10.7% and 10.4% respectively.

In the current academic climate, predatory publishing is practiced and strengthened through a number of mechanisms aimed at gaining benefits. These include increasing a research profile, obtaining promotions and higher designations, obtaining jobs and tenure, and as an institutional requirement for postgraduate students to defend their final dissertation. According to the set criteria, both university professors and postgraduate students are involved in journal publications, regardless of the quality of the publication. Publishing in a journal with the tag of “an international journal” is regarded as a big achievement in Pakistan, without realizing the malpractices of predatory journals. By paying huge amounts of money, university teachers and researchers easily get their substandard research published in such journals.

5.2 Students’ perspectives about publishing practices in Pakistan

The dominant themes emerged in the interview data were related to a) publication as a symbolic capital e.g., promotions, degree awards, market recognition b) international publication as a big achievement c) unawareness about predatory publishing practices d) university professors’ insistence for more publications e) institutional policies. In presenting our interview data, we have chosen pseudonyms for postgraduate students from different disciplines at public sector universities in Pakistan using their excerpts. The interview findings indicate that postgraduate students are the most important source for the university professors to increase their number of publications to meet HEC criteria for university teachers’ promotions as an Associate/full Professor. In the interview data, one of the participants commented:

I had my first article published solely because it was the requirement of my academic degree. I was not aware of the benefits that publication can bring to one’s profile. However, my second article was a kind of professor’s pressure to get it published from the same thesis/dissertation. And in this process, my professor recommended the specific journal to send the article (Zaib, interview, 25/2/2022).

In Pakistani universities where one publication is mandatory for PhD defense besides the dissertation draft and completion of the coursework, it is also a requirement in some of the universities for the master’s students to publish one article. As per rule, the article is to be published in either HEC recognized national, or in any international peer-reviewed journal. However, the article is published in the predatory journals as the students pay the money to the journals and get their article published without any peer review process. In some cases, the university professors pay for the students’ articles upon their recommendation of the paid predatory journal. The institutional policies, in Bourdieu (Citation1991) sense, legitimize the publication as a dominant practice without realizing the violence enacted through predatory publishing practices. Under the institutional pressure, professors working as research supervisors encourage students to send their articles to the international open access journals (predatory in most cases as the data reveals). These predatory journals publish articles in a short period of time to help the students meet the university’s deadlines. The published articles by the students as a part of universities’ policy ensure the addition of supervisor(s)’ names. In some cases, the names of the professors’ colleagues are also added in the same article. One of the students in the interview remarked:

I was asked to add my professors’ colleagues as coauthors in my article without any academic contribution from them, except for the article processing fee which was required in the journal. When the article was published, I got to know from another teacher that the journal was initially recognized by HEC, but later it was removed from the list for its malpractices in academic publishing (Kulsoom, interview, 28/2/2022).

Most of the students were unfamiliar with the fraudulent acts involving academic publishing. They misrecognized this practice as a natural way of doing it. For most participants in the interview, labels like “European,” “International,” “American,” “Canadian” or alike that refer to the first-world academic publishing was fascinating, and they submitted the manuscripts through e-mails they received from the editors of those predatory journals. One student from linguistics department at a public sector university told in the interview that “my research supervisor forwards the emails to me that he receives from the journal editors. I am asked to send the manuscript to given email address” (Sara, interview, 2/3/2022). As the following excerpt with Sara further illustrates this practice in detail:

Interviewer:Can you please elaborate how you got your first article published?

Sara:I sent the article to the editor – the same e-mail that was forwarded to me by my research supervisor.

Interviewer:What happened then?

Sara:I was contacted by the editor that the article is good, and they are willing to publish it upon the receipt of article processing charges (APC’s).

Interviewer:So, how much time then it took you to process and get the article published?

Sara:It took me one and half week to see my article online.

This phenomenon of publishing in a short time indicates that the predatory journals do not ensure quality measures, such as peer review process. Their only concern is “money.” This pay-to-publish approach facilitates the university professors and the postgraduate students equally to fulfill the institutional criteria. However, what is at stake is the quality of research output compromised in the process. Some other participants from various fields of social sciences and humanities at public sector universities had a similar experience. For example, one postgraduate student from economics stated that “publishing an article is not difficult if we have written it using the correct format of the article. The major problem, however, is the article publishing fee. I am a private school teacher and I earn to afford my university fee and expenses. I cannot manage to pay for publications. But since we have no option, we have to do it” (Barkha, interview, 5/3/2022). The economic pressure associated with the predatory journals remains unidentified and unaddressed in Pakistani academia since the institutional policies obligate the postgraduate researchers to publish an article to be eligible for the dissertation defense. However, this practice of article publication at master’s level is not compulsory at many universities in Pakistan in accordance with Higher Education Commission (HEC) policy. Doctoral researchers, on the other hand, are required to produce one article published in a HEC recognized journal, either nationally or internationally.

In addition, the market factor was also found to play a significant role in increasing predatory publications. In Pakistan, academic and job industry prioritizes publications over pedagogical skills in hiring people for teaching positions at the universities. The following interview excerpt from one participant from sociology department explains how the market forces compel the students and other researchers to increase a publication number instead of quality publication in reputed journals:

I publish the article because it has a market, a sort of academic demand in the institutions, in the job market. Wherever you go for jobs, the first thing they ask you is about the number of publications. It seems like it has come as a sole criterion to judge the merit of the person for teaching, not knowing what is published and where. … very recently, it happened that a boy who appeared in the job interview was considered only based on his number of publications – 17 published articles in less than two years’ time (Khalid, interview, 8/3/2022).

Another participant from gender studies department remarked:

To be honest, I don’t see any interest in publishing in academic journals, since I feel it is limited and people do not read what we publish in the journals. Just because of the market pressure, I am feeling anxious to push myself into this publishing game. My own interest is in translation in my own language. And it is being compromised because of this increasing job market pressure in academia. It is an elite activity I must say (Noor-ul-ain, interview, 10/3/2022).

Bourdieu’s (Citation1991) symbolic violence seems to be acting not only through institution and individual university professors, but also through neoliberal ideology at large, which creates a compelling space for a neoliberal market in the academic publishing in Pakistan. Moreover, the study found that postgraduate students were hardly trained on the differences between predatory journals and reputable ones. As a result, students preferred to follow the similar trends of publication using the similar publication channels. As in the following discussion, one student from the department of International Relations (IR) confesses it:

Interviewer:Have you ever been told about predatory journals in your classrooms?

Ruhail:We have never discussed the term, such as “predatory” in the classrooms. Neither in our coursework, not during the research phase. What we know is that an international publication is a big achievement.

The de-familiarity factor explains how the university courses reinforce the predatory publishing by disallowing such discussions in the classrooms, or during the research phase outside the classes since the postgraduate students’ knowledge of the existing malpractices may not further facilitate the on-going malpractices in the country. Therefore, it is misrecognized in Bourdieuan sense so that the fake publication comes to be considered and accepted as “legitimate/natural” outcome of research degrees in Pakistan.

6. Discussion

University professors’ extensive use of non-peer-reviewed journals indicates a lack of academic integrity and academic reputation in the international research community. Publication goals are perceived as “instrumental” rather than the desire and responsibility to contribute to scientific research in the social sciences and humanities. Furthermore, the slight difference across all fields within social sciences and humanities indicates a common trend in the country. This shows a specific attitude toward knowledge production and its usefulness to the community and academia. The HEC introduced a policy in 2005 that encourages publishing in both national and international journals. The objective was to promote academic and publication standards. Additionally, the publishers and editors were instructed to take safe measures to prevent the publication of papers that contain misconduct, such as plagiarism, citation manipulation, and data fabrication or falsification. However, the data indicates that 157 articles are published in national predatory journals whereas 188 are published in international predatory journals, violating HEC standards.

According to the present study, the primary reason for the predatory turn in the publishing industry in Pakistan is competition to accumulate more symbolic capital (Bourdieu Citation1977, Citation1991). This process of capital accumulation enacts the act of symbolic violence in a way that allows the dominated group, i.e., the postgraduate students, to participate in the symbolic act, which is manifest in the form of a “predatory publication.” Similar participation is found in the case of university professors who compete for publication of their academic work in such journals. University professors enact symbolic violence against postgraduate students while mis-recognizing the neoliberal ideology at play through the predatory publishing industry working actively globally. This is in line with Ebadi and Gerannaz (Citation2018) who highlighted the professors’ pressure upon students that led them to plagiarize and write “wishy-washy paper,” as they describe it, to get the term grade.

These individuals, both professors and students, participate in these symbolic acts without questioning their role in the production of subordination and dominance (Bourdieu Citation1977). As such, symbolic violence is “misrecognized” by the participants since it remains outside the control of their consciousness and everyday life experiences, which Bourdieu refers to as their “habitus.” As one of the study participants stated, their peers and teachers considered an international publication to be a significant accomplishment. As the habitus forms in academia, they become prone to misrecognition, which results from the legitimization of existing practices through symbolic meanings exerted on individuals and social practices in a given social structure (Jenkins Citation1992, 104). The present study found that the labeling of journals associated with symbols, such as “American,” “European,” “Australian” or “Canadian,” was idealized by postgraduate students and they often received e-mails with such “tags” associated with the journals. Kozak, Lefremova, and Hartlye (Citation2016) have reported how the journals send e-mails to attract the audience. For example, their study notes 70% of such journals mentioned in Beal’s list that contact individual authors with generous offers to get their work published in a short period of time. These tags prove to be attractive when compared with Pakistan – a country still under colonial idealizations.

Individuals perceive the situation as “natural.” According to Bourdieu (Citation1991), symbolic violence is a subtle and invisible form of violence. Participants in the study failed to recognize that research journals were neoliberal entities that exploited scholarly labor for economic gain. Both are engaged in a process of symbolic violence and neoliberal ideology that strengthens the existing practices by providing promotions, financial incentives, and degree conferment to students, which generates a symbolic capital for the university faculty as well as the students. Torres (Citation2022) has also indicated that in some cases, those who publish in predatory journals are unaware of it as a contributing factor to business rather than knowledge production.

Some students misrecognize this and submit articles to predatory journals with their university professors acting as their supervisors. This is because they cannot get their degrees without the published article, which is a requirement of some universities in Pakistan. Accordingly, university professors with high levels of capital invest in publishing for promotion and sustaining institutional pressure, while postgraduate students with low levels of capital do the same to defend their thesis. As noted by Ebadi & Zaman (Citation2018), the publication of low-quality papers in predatory journals has prompted a culture in which high-quality publications in reputable journals are given less weightage, and the importance of quantity over quality in research publications is considered legitimate.

In the present study, university professors acted as individuals who comply with the university’s publication policies as determined by the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, to produce research-led knowledge in order to compete for ranking and accreditation. Consequently, they publish through several unfair means, e.g., by encouraging their postgraduate students to publish their work together with the names of the professors and their colleagues as coauthors. In addition, they pay the journals to publish their work. University professors engage in this practice under the pressure of universities and for their own incentives, i.e., to achieve the required number of publications for promotion. Shen and Bjork (Citation2015) have observed that some authors and institutions “are part of a structurally unjust global system that excludes them from publishing in ‘high quality journals’ and confines to publish in dubious journals.” Memon (Citation2018) revealed the same reasons why university professors and academics publish in predatory journals, such as quick and easy publication without a strict peer review process leading to career advancement, securing grants and funding, and satisfying an ego for an international publication.

7. Limitations

This study focuses only on Pakistani social science and humanities researchers. The results of the current study, thus, cannot be generalized to other fields of research or to other countries.

8. Conclusion

We sought to investigate the status of academic publishing in Pakistan in several disciplines of social sciences and humanities. According to findings of the study, a significant number of social science and humanities research papers over the period 2017–2021 in Pakistan were published in “predatory” journals. In this process, job market, promotions and tenures, as well as an institutional requirement that postgraduate students publish at least one article for dissertation defense, played a major role. Universities following Higher Education Commission’s (HEC) publication policy for accreditation and global ranking process are heavily influenced by the predatory publishing industry acting under neoliberalism which trickles down to university professors and postgraduate students.

In a nutshell, this practice undermines academic integrity in Pakistan. As a result, substantial intellectual labor is being wasted, resulting in knowledge that is unreliable and/or untrustworthy. We suggest that the Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan should establish a more centralized research online network for researchers to submit published research articles and work, which then need to be scrutinized by a team of credible researchers and experts before any decisions on promotions are made. Moreover, the universities’ internal selection process for promotions is highly flawed as it promotes favoritism in most cases. The selection boards and experts through their personal contacts influence the entire process of merit and quality assurance for research publications. In order to ensure merit, quality, and transparency across all public sector universities, decisions should be made at the provincial and/or national levels under HEC, Pakistan, making publications visible to all university researchers. As a final comment, we suggest that the current practice of requiring monograph dissertations as well as research article publications in research degree programs is flawed because it does not advance knowledge. Therefore, the HEC should revise its policy to allow universities to shift from monograph dissertations to article-based dissertations. In this case, the articles need to be published in peer-reviewed international journals since the current national research journals are based on networking among university professors and favoritism that compromises the quality of research output. This study has implications for research beyond Pakistan, since many countries are dealing with issues concerning predatory publication. Universities, funding organizations, professional associations and policymakers should take steps to discourage researchers and students from publishing in predatory journals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atiso, K., J. Kammer, and J. Bossaller. 2019. “Predatory Publishing and the Ghana Experience: A Call to Action for Information Professionals.” IFLA journal 45 (4): 277–288. doi:10.1177/0340035219868816.

- Beall, J. 2012. “Predatory Publishers Are Corrupting Open Access.” Nature 489 (7415): 179. doi:10.1038/489179a.

- Beall, J. 2014. “Unintended Consequences: The Rise of Predatory Publishers and the Future of Scholarly Publishing.” IARTEM E-Journal 2 4–6.

- Berger, M. 2017. “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Predatory Publishing but Were Afraid to Ask Introduction: Librarians and Predatory Publishing.” Association of College and Research Libraries 206–217.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of Theory and Practice. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power, edited by B. T. John. Cambridge: England: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and J. D. Wacquant. 1992a. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and T. Eagleton. 1992e. “Doxa and Common Life.” New Left Review 191 (1).

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Butler, D. 2013. “The Dark Side of Publishing.” New Scientist 217 (2910): 29. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(13)60817-9.

- Chavarro, D., P. Tang, and I. Ràfols. 2017. “Why Researchers Publish in non-mainstream Journals: Training, Knowledge Bridging, and Gap Filling.” Research Policy 46 (9): 1666–1680. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2017.08.002.

- Cobey, K. D., M. M. Lalu, B. Skidmore, N. Ahmadzai, A. Grudniewicz, and D. Moher. 2018. “What Is A Predatory Journal? A Scoping Review.” F1000Research 7:1–30. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15256.1.

- Dadkhah, M., L. Mohammad, and G. Borchardt. 2017. “Questionable Papers in Citation Databases as an Issue for Literature Review.” Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling 11 (2): 181–185. doi:10.1007/s12079-016-0370-6.

- Demir, S. B. 2018. “Predatory Journals: Who Publishes in Them and Why?” Journal of Informetrics 12 (4): 1296–1311. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2018.10.008.

- Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. 2021. “Predatory Journals and Meetings in Forensic Sciences: What Every Expert Needs to Know about This “Parasitic” Publishing Model.” Forensic Sciences Research 6 (4): 303–309. doi:10.1080/20961790.2021.1989548.

- Ebadi, S., and Z. Gerannaz. 2018. “Predatory Publishing as A Case of Symbolic Violence: A Critical English for Academic Purposes Approach.” Cogent Education 5 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2018.1501889.

- Eriksson, S., and G. Helgesson. 2017. “The False Academy: Predatory Publishing in Science and Bioethics.” Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy 20 (2): 163–170. doi:10.1007/s11019-016-9740-3.

- Jenkins, R. 1992. Pierre Bourdieu. New York: Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Khan, A. A. 2021. “Rising Reliance on Predatory Publishing as Research Expands.” https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=2021062608133724

- Kozak, M., O. Lefremova, and J. Hartlye. 2016. “Spamming in Scholarly Publishing: A Case Study.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 67 (8). doi:10.1002/asi.23521.

- Kumari, R., M. Babur, and N. Siddiqui. 2017. “Research and Development: Review of Research Performance in Higher Education Sector in the Last Decade.” Higher Education Commission, Pakistan.

- Machacek, V., and M. Srholec. 2021. “Predatory Publishing in Scopus: Evidence on Cross-Country Differences.” Scientometrics 126 (3): 1897–1921. doi:10.1007/s11192-020-03852-4.

- Masood, E. 2018. “What Pakistan’s new government means for science.” https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05974-5

- Memon, A. R. 2018. “How to Respond to and What to Do for Papers Published in Predatory Journals?” Science Editing 5 (2): 146–149. doi:10.6087/KCSE.140.

- Mills, D., and K. Inouye. 2021. “Problematizing ‘Predatory Publishing’: A Systematic Review of Factors Shaping Publishing Motives, Decisions, and Experiences.” Learned Publishing 34 (2): 89–104. doi:10.1002/leap.1325.

- Natow, R. S. 2019. “The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Studies Employing Elite Interviews.” Qualitative Research 20 (2): 160–173. doi:10.1177/1468794119830077.

- Negahdary, M. 2017. “Identifying Scientific High Quality Journals and Publishers.” Publishing Research Quarterly 33 (4): 456–470. doi:10.1007/s12109-017-9541-4.

- Omobowale, A. O., O. Akanle, A. I. Adeniran, and K. Adegboyega. 2014. “Peripheral Scholarship and the Context of Foreign Paid Publishing in Nigeria.” Current Sociology 62 (5): 666–684. doi:10.1177/0011392113508127.

- Pond, B. B., S. D. Brown, D. W. Stewart, D. S. Roane, and S. Harirforoosh. 2019. “Faculty Applicants’ Attempt to Inflate CVs Using Predatory Journals.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 83 (1): 7210. doi:10.5688/ajpe7210.

- Sapiro, G. 2015. “Field Theory.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by J. Wright, D, 140–148. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Schubert, J. D. (2008). “Suffering.” In Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts (London and New York: Routledge) 179–194 , edited by M. G. Acumen.

- Shehata, A. M. K., and M. F. M. Elgllab. 2018. “Where Arab Social Science and Humanities Scholars Choose to Publish: Falling in the Predatory Journals Trap.” Learned Publishing 31 (3): 222–229. doi:10.1002/leap.1167.

- Shen, C., and B. C. Björk. 2015. “‘Predatory’ Open Access: A Longitudinal Study of Article Volumes and Market Characteristics.” BMC Medicine 13 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0469-2.

- Torres, C. G. 2022. “Editorial Misconduct: The Case of Online Predatory Journals.” Heliyon 8 (January): e08999. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08999.

- Walther, M. 2014. Repatriation to France and Germany: A Comparative Study Based on Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice. Springer.

- Wiegmann, W. L. 2017. “Habitus, Symbolic Violence, and Reflexivity: Applying Bourdieu’s Theories to Social Work.” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 44 (4): 95–116.

- Xia, J., J. L. Harmon, K. G. Connolly, R. M. Donnelly, M. R. Anderson, and H. A. Howard. 2015. “Who Publishes in “Predatory” Journals?” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66 (7): 1406–1417. doi:10.1002/asi.23265.

- Yousufzai, A. 2021. “Fraudulent Research Thriving in Pakistan Due to HEC’s Apathy.” https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/902868-fraudulent-research-thriving-in-pakistan-due-to-hec-s-apathy