ABSTRACT

Epistemic responsibilities (ERs) of universities concern equipping and empowering its researchers, educators and students to attain, produce, exchange and disseminate knowledge. ERs can potentially guide universities in improving education, research and in service to society. Building on earlier philosophical work, we applied empirical methods to identify core ERs of universities and their constituting elements. We used a three-round Delphi survey, alternating between closed questions to gain consensus, and open questions to let panelists motivate their answers. 46 panelists participated in our study. We reached consensus on six ERs: 1) to foster research integrity, 2) to stimulate the development of intellectual virtues, 3) to address the big questions of life, 4) to cultivate the diversity of the disciplinary fields, 5) to serve and engage with society at large, and 6) to cultivate and safeguard academic freedom. Together the six ERs contain 27 elements. Consensus rates ranged from 73%-100% for both the ERs and their elements. Participants’ detailed responses led to substantial improvements in the accompanying descriptions of the ERs. Our findings can inform the debate about the roles and responsibilities of universities, and inform researchers and policy makers to emphasize epistemic tasks of universities.

Introduction

Modern universities are places of higher education and research, composed of communities of researchers, educators, students and supporting staff. They are continuously adjusting to the societies in which they are positioned (Holmwood Citation2014). We can therefore speak of a plurality of universities, as local, cultural, political and societal influences lead to their adaptation and transformation. In the last half century, developments included new study subjects emerging rapidly, expanding student numbers, internationalization of academia, and the importance of academic research increasing with the advancement of knowledge economies (Altbach Citation2013; Calhoun Citation2006; Moore Citation2019).

While many of these developments are regarded as positive (e.g., increase in access to university education), universities have also received much critique. Recent debates have centered on, for example, the commodification of education and research, managerialism, bureaucratization, loss of academic freedom and national and global (hyper)competition for funding, prestige and status (the latter often in the form of focus on university rankings) (Brankovic, Ringel, and Werron Citation2018; Cole Citation2021; Collini Citation2012; Copeland Citation2022; Rolfe Citation2013; Shore Citation2010; van Houtum and van Uden Citation2022). University rankings, as Ordorika and Lloyd (Citation2015) argue, provide a uniform (and hegemonic) image of what constitutes “world-class” universities, with universities worldwide wanting to conform (and reform) to those in the highest ranks. Both methodologically and conceptually rankings have received much critique, but it seems surprisingly difficult to steer away from rankings.

In the current research paper, we want to explore an alternative way of regarding what could constitute a good university, treating it both as a philosophical question and testing our ideas on a wider group of experts. Alternative ways of conceptualizing what a good university is may, on the one hand, respond to the abovementioned critique on the contemporary university, and on the other hand, present a different, diversified, and richer view of universities than those presented in current university rankings.

Furthermore, there are myriad examples of research projects that focus on improving the quality of research and education, preserving and improving academic freedom, and improving the connections between universities and society (Bovill Citation2020; Coelho and Menezes Citation2021; Kember Citation2009; Kinzelbach et al. Citation2020; Moher et al. Citation2020; Schmidt, Curry, and Hatch Citation2021; Silvertown Citation2009). However, far fewer initiatives and research projects focus on the university as a whole. Combining these different pieces creates a more complete, multifaceted, and balanced view of the university and, given the framework as we present below, we hope, can inspire improvement of universities through its emphasis on epistemic tasks.

To elaborate, despite local, cultural, political and societal differences, there is more or less a stable core in what universities seek to accomplish: to create, exchange, safeguard, and disseminate knowledge and other knowledge-related (or: epistemic) goods, such as insight, rational belief, and understanding (Peels et al. Citation2020) – through education, research and in service to society. This can be understood as the university having certain epistemic responsibilities. Even though universities have various other responsibilities such as moral, social, financial, and legal, the epistemic ones can be considered to be at the university’s heart (although the different responsibilities clearly overlap). Focusing the attention of universities on these epistemic responsibilities, rather than e.g., rankings, might prove fruitful in diversifying the views of what constitutes a good university.

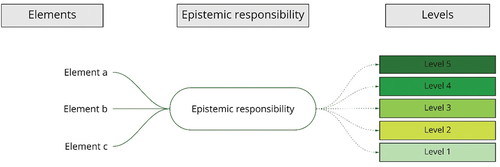

Nonetheless, this raises the question of what concrete epistemic responsibilities of universities are. Peels et al. (Citation2020) proposed five of them, viz: to 1) foster research integrity 2) teach for intellectual virtues, 3) address the big questions of life, 4) give humanistic inquiry and education a proper place and, 5) serve society. These five responsibilities serve as a starting point of the current study, as we want to test, expand, and concretize the previous ideas of Peels et al. For instance, each epistemic responsibility likely consists of several distinct (optional) elements which are the concrete realizations of a particular epistemic responsibility. For example, for research integrity, elements can include supervision and mentoring, research integrity education, and dealing with research misconduct (Labib et al. Citation2021). We were moreover inspired by the TOP guidelines (The TOP Guidelines Committee Citation2014), which aim is to improve Open Science practices in journals. Likewise, we aim to provide a framework that universities might use to reflect on their epistemic responsibilities. Hence, we expect the degree of meeting the responsibilities can be hierarchically ordered in various levels, from minimal to maximal fulfillment (see ).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the epistemic responsibilities, elements and levels. The higher order are the epistemic responsibilities universities have and should meet. The elements are of a lower order than the corresponding epistemic responsibility and are their potential concrete realizations. The levels, from 1–5 from minimal to maximal fulfillment constitute the degree of fulfillment of a specific epistemic responsibility.

With the proposal of Peels et al. (Citation2020) as a starting point, this study aims to explore and collect an empirical basis for these conceptualizations and thus answers: 1) What are the core epistemic responsibilities of universities? 2) What are the elements of these epistemic responsibilities? And 3) how can each of the levels of meeting that epistemic responsibility be described?

Methods

The Delphi method

To answer the research questions, we conducted a three-round online Delphi study. The Delphi approach is characterized by engagement and structured communication with and among experts in order to reach consensus on a topic. It is especially useful in areas where knowledge is scattered or disagreement predominates the discourse (Linstone and Turoff Citation2011; Powell Citation2003). Typically, experts are invited to partake in a Delphi panel, and interaction between Delphi panelists is structured by a steering committee (here, the authors of this paper). Panelists remain unaware of each other’s identities, so renowned or authoritative panelists are unable to dominate the process at the expense of others (Linstone and Turoff Citation2011). Prior to the study, we registered our study protocol on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/j8w93).

Process of the Delphi study

The set-up of the Delphi study was to alternate between explorative-, open-, consensus- and elaboration questions (see ). The rationale for including explorative questions was to investigate newly introduced topics openly and find novel ideas (Powell Citation2003). Panelists were asked to rate their agreement to consensus questions on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree – somewhat agree – neither agree nor disagree – somewhat disagree – strongly disagree). We also included the option “no expertise.” If this option was selected it was not used in calculating the consensus rate. We defined consensus as 67% (i.e., two-thirds) of panelists (strongly) agreeing to a question (Diamond et al. Citation2014). If no consensus was reached, the steering committee made a final decision.

Figure 2. Structure of the Delphi rounds. Epistemic responsibilities are abbreviated to ‘ERs’. After each consensus “rating” question an elaboration question was asked.

Throughout the three rounds we asked consensus questions on the inclusion of the epistemic responsibilities and elements, and about the completeness and accurateness of their working descriptions. After each consensus question we asked an elaboration question where panelists could write down their reasoning, arguments, and comments. We also asked open questions where panelists could propose novel responsibilities and elements (round 1) and reflect on the completeness of the list of responsibilities and elements (round 2). For a detailed description of each Delphi round, see https://osf.io/ef2t9. Surveys were sent using the online survey software Qualtrics (Qualtrics Citation2020). Before the start of the next round panelists received feedback reports of the results of the previous round (https://osf.io/d8gje and https://osf.io/wgrvu).

The preparation phase

In order to make the best use of available knowledge and to diminish time demands on the invited experts we had a preparation phase before the first Delphi round. The first author reviewed relevant literature to identify potential epistemic responsibilities and elements, and to formulate “working descriptions” (https://osf.io/mdgwb). These working descriptions were integral to the Delphi surveys because panelists based their responses on these descriptions.

Additionally, the steering committee discussed the list of potential epistemic responsibilities. Based on these discussions we added “to ensure and safeguard academic freedom” as a sixth potential epistemic responsibility to Peels et al.’s original proposal. We also adapted “to give humanistic inquiry a proper place” to “to accommodate the diversity of all disciplinary fields” (see ).

Table 1. List of potential epistemic responsibilities after the preparation phase.

For academic freedom, we made use of the work of Kinzelbach et al. (Citation2020) to specify elements. For research integrity, a recent Delphi study defining “elements” was conducted by three of the authors of this paper. Therefore, we decided not to include questions about the elements of research integrity in the current study, and to include the nine elements as defined by Labib et al. (Citation2021) instead. In addition, we informally interviewed four experts to identify any gaps in the list of potential epistemic responsibilities (see https://osf.io/hs2kr). These experts did not partake in the Delphi panel.

Based on the above steps, we i) identified six potential epistemic responsibilities ii) identified 26 potential elements, iii) formulated working descriptions for each responsibility and element iv) formulated a broad definition of “epistemic responsibilities of universities” (https://osf.io/6w5pz for i-iv) and v) drafted the first survey questionnaire (https://osf.io/6ejdv Before sending out each survey we asked 1–3 pilot testers (i.e., colleagues who met the inclusion criteria and expressed their interest) to test the survey. Based on the pilot tests we made minor clarificatory adjustments to the surveys prior to sending out each round. The responses of the pilot testers were included in the data set.

Panelist selection

We invited experts from a large geographical spread and took into account gender, disciplinary field, and career stage. The inclusion criteria for participating in the Delphi panel, which had the purpose to select a diverse and heterogenous group of panelists, were as follows. A potential panelist (“expert”) needed to have written at least one article or (co)-authored a book (chapter) on 1) one or more of the potential epistemic responsibilities, 2) the epistemology, responsibilities, or role of universities, or 3) research on or development of university assessment instruments, such as university rankings (Baker, Lovell, and Harris Citation2006). Next to researchers, we included (former) administrators (vice-chancellors, deans, policymakers) with practical knowledge and hands-on experience of leading a university (or its departments) and making policy, bringing in a different kind of expertise on the inner workings of universities. We made use of purposive sampling by selecting experts from relevant literature and reaching out to personal contacts. We additionally used snowballing to search for more experts. The steering committee did not participate in the Delphi panel.

Analyses

Consensus rates were calculated in Excel. Qualitative analysis was performed using MAXQDA 2018/2022 (VERBI-Software Citation2022) and all open (i.e., explorative, open, and elaboration) answers were coded by IL by grouping on type of answers (e.g., revising or changing aspects, adding aspects, importance of the topic, agreement, critique, etc.) (Brady Citation2015). A sample of 15% of open answers were coded by JT, and discrepancies were discussed until agreement was reached. The steering committee discussed the consensus rates and arguments from the panelists. Based on these discussions, the steering committee decided on the content of the next round, as well as on modifications of the descriptions and additions of responsibilities or elements. We drew heavily on the answers participants gave to open questions to guide our decisions. For instance, if consensus was reached but panelists were critical in their answers this led to presenting the topic again in the following round.

Results

The Delphi panel

Of the 231 invited panelists, 46 panelists participated in at least one of the rounds (overall response rate: 20%) and 18 panelists completed all three rounds. Partial responses were not analyzed. In we describe the invitation process, including participation per round. The characteristics of the panelists can be found in . A heterogenous group took part in the Delphi study, in terms of gender, career stage, job position, discipline, and geographic region. Due to the difficulty of selecting expert administrators we made use of convenience sampling of administrators in our (largely Dutch) network, and asked pilot testers working in the Dutch context, which resulted in overrepresentation of Dutch participants of these groups (see https://osf.io/472fm for more detailed characteristics).

Figure 3. Flowchart that demonstrates the selection of participants for all 3 Delphi rounds *13 participants opted out and were not invited for later rounds.

Table 2. Characteristics of Delphi panelists (n = 46). For more details, the list of all countries and other categories see https://osf.io/472fm.

The epistemic responsibilities of universities

Based on the consensus from the three rounds we identified six core epistemic responsibilities: 1) to foster research integrity, 2) to stimulate the development of intellectual virtues, 3) to address the big questions of life, 4) to cultivate the diversity of the disciplinary fields, 5) to serve and engage with society at large, and 6) to cultivate and safeguard academic freedom.

Together the six epistemic responsibilities consist of 27 elements (for 18 of which consensus was reached in the current study, and 9 in the study by Labib et al. Citation2021). In we provide the descriptions of each epistemic responsibility as formulated throughout the three Delphi rounds and list the 27 elements. In we list the consensus rates. For the complete descriptions of all responsibilities and elements (including examples and possible misunderstandings), see https://osf.io/c36sy. The dataset from the study can be found here: https://osf.io/472fm. For the changes in our understanding of the responsibilities and elements, based on our qualitative analysis, see https://osf.io/7pgx2.

Table 3. Descriptions of the epistemic responsibilities and elements.

Table 4. Rates of consensus for the epistemic responsibilities and elements.

As no suitable (general) formulation of epistemic responsibilities of universities was available we asked panelists to comment on this in the first round. Based on these comments we formulated the following characterization:

Epistemic responsibilities of universities are equipping and empowering its researchers, educators and students to attain and produce diverse evidence and knowledge, and to allow exploration of understanding, insight, rationality, and explanation, as well as the dissemination, exchange and safeguarding of knowledge. The freedom toward fulfilling these responsibilities is essential. As knowledge can be understood as a public good, seeking and evaluating knowledge is interlocked with its dissemination to students and its role in service to society.

Consensus and process of the Delphi rounds

In round 1, we reached consensus on all consensus questions. Consensus rates were between 73% and 100% (). On average, explorative, elaboration, and open questions were answered by half of the panelists. Based on qualitative analyses of these answers the “working descriptions” of all epistemic responsibilities and elements were revised (https://osf.io/ne43s). The answers to the explorative and open questions in round 1 led to the inclusion of one new element; “to address epistemic injustice in academia” as part of the responsibility “to stimulate the development of intellectual virtues”. Other answers to explorative and open questions were already included or could be merged with an existing element or responsibility (https://osf.io/d8gje). For instance, four panelists made suggestions to include “sustainability” as a new responsibility or element, this is now included under “to serve and engage with society at large” (see e.g., pg. 14 on https://osf.io/c36sy). Furthermore, panelists made numerous suggestions to change the names of specific epistemic responsibilities and elements. For example, the word “accommodate” in “to accommodate the diversity of the disciplinary fields” raised much discussion. Hence we decided to change the word to “cultivate”. We changed the names of 4 epistemic responsibilities and 5 elements and asked about these name changes in round 2 (see https://osf.io/ne43s for more details).

When asked to provide their reasoning for their (dis)agreement, panelists were often more critical than the consensus rates suggested. These answers were guiding in the iterative process of the Delphi study. Thus, even though consensus was reached, the steering committee decided to present the revisions of five of the epistemic responsibilities and eight elements in round 2 (see https://osf.io/zpy3s for the survey of Round 2).

In round 2 consensus was reached on all questions (ranging between 73% and 100%). Nonetheless, panelists were critical of the newly included element “to address epistemic injustice in academia” so we decided to present revisions of this element in round 3. Based on the qualitative analysis of the elaboration questions of round 2 we revised the working descriptions of the elements and epistemic responsibilities again leading to the next version of the working descriptions (https://osf.io/pyr93), and drafted the survey of round 3 (https://osf.io/ksfcj).

In round 3 we did reach consensus (84%) on the revisions of “to address epistemic injustice in academia.” The name of the element was changed after round 3 to reflect the comments of panelists to “to address and minimize epistemic injustice in academia.” One further open question we asked was whether panelists had a terminological preference for “epistemic justice” or “epistemic injustice.” No consensus was reached on the phrasing of this element (66,7%). The steering committee decided to center on “epistemic injustice” since the current discourse focuses on this term.

Prerequisites of epistemic responsibilities

In round 2 we asked explorative questions on whether panelists thought certain epistemic responsibilities were a requirement for others, or whether some take precedence over others. In round 3 we asked this question again, but this time panelists were asked to put the six responsibilities in three categories: is a prerequisite/is not a prerequisite/none of them are prerequisites. Three trends can be observed here. First, panelists named academic freedom most often as being a prerequisite for the other epistemic responsibilities (Round 2: 9 out of 23 answers. Round 3: 15 out of 25 answers). Research integrity and intellectual virtues were named most after academic freedom (https://osf.io/dybn9).

Second, the majority of panelists pointed out interrelations between various responsibilities. Such as that “the cultivation of diversity of disciplinary fields would create room to address the big questions of life,” that “intellectual virtues are created in the other responsibilities” or that “the responsibilities are mutually dependent,” as three panelists wrote.

Third, a share of the panelists found all epistemic responsibilities to be equally important, and several others wrote down that none of the responsibilities are prerequisites to others. As one panelist wrote, “I feel the 6 responsibilities go hand-in-hand. While the responsibilities can be at different stages of development within a university or within a teacher or student’s realm of comprehension, they are most productive when learned, shared and nurtured together.” This thought was also reflected in other answers.

Potential levels of the epistemic responsibilities

In Round 3 we asked panelists to rate how well their institute was doing with regard to the epistemic responsibilities, on a scale of 1–5, from minimal to maximum fulfillment, and to give a rationale for their answers. We received a myriad of answers focusing on different aspects. For instance, panelists would explain that there was a lack or presence of institutional commitment, or organizational structures (giving lower and higher rates, respectively). Moreover, panelists wrote that individual researchers did not seem to care (lower rates), or that they did care about the responsibility at hand (higher rates). Some panelists wrote that a certain responsibility was a part of the identity of their institute. For instance, one panelist commented that serving and engaging with society “is built into the DNA of my institution.” This was most notable for the epistemic responsibilities “serving and engaging with society” and “cultivating and safeguarding academic freedom”. Furthermore, various panelists pointed out that funding plays an important role. As one panelist wrote for “cultivating the diversity of the disciplinary fields”: “My university supports disciplines that bring in the most research money. Since not all disciplines receive the same levels of research money, not all disciplines receive the same level of support.” Notably, one panelist wrote that they refused to rate their institute since they feared that our study would be “the birth of yet another ranking with yet another (although similar) set of corrupting and undesired consequences.”

Discussion

With this Delphi study we have made a first, systematic attempt at describing concrete epistemic responsibilities of universities in detail. We found widespread consensus among the Delphi panel on six core epistemic responsibilities of universities. First, the five responsibilities suggested by Peels et al. (Citation2020) were judged to be important by the Delphi panelists. Our Delphi study added a sixth responsibility and enriched and clarified the formulations of the epistemic responsibilities and their constitutive elements.

Second, consensus was reached on all responsibilities and elements in this study. Interestingly, no topics were eliminated. In addition, based on the explorative and open questions in the Delphi survey, one element was added: “to address and minimize epistemic injustice in academia”. Since we cover a broad range of topics, panelists’ suggestions could often be added to previously identified responsibilities and elements. The elaborate replies and active engagement of the panelists led to substantial improvements, more clarity, and a greater understanding of the epistemic responsibilities and elements.

Third, universities are but one of many kinds of actors active in complex societies. Panelists often reflected on the extent to which individual universities could and should have control over the extent to which they meet these six responsibilities. On the one hand, societal factors influence what universities can and cannot do, which is most clear for the topic of academic freedom (Barnett Citation2018). Panelists suggested that the role of individual universities in cultivating and safeguarding academic freedom is fairly constrained, as exercising and protecting academic freedom is difficult in politically unstable or authoritative states (Owen Citation2020; Spannagel, Kinzelbach, and Saliba Citation2020). On the other hand, many of the responsibilities can be shared by universities collectively. For instance, panelists suggested that the cultivation of the diversity of disciplinary fields can be shared across a region or nation. This also goes for addressing the big questions, where universities ought to be able to choose which questions they want to focus on, to be able to collectively address a wide range of big questions.

Fourth, our panelists provided some indication that academic freedom is a requirement for other responsibilities. Not everyone agreed, and perhaps unsurprisingly, many panelists pointed out interrelations between the responsibilities, where one stimulates (or impedes) the other.

Fifth, in the literature the term “epistemic responsibility” is generally not used in the way in which it is presented in the current study. The term is, for instance, used to refer to being epistemically blameworthy or praiseworthy (Corlett Citation2008). Chubb and Reed (Citation2017, 3) define it as “relating to knowledge as an epistemic good for which one has responsibility toward the public and society,” which is closer to our use. With our definition we cover the breadth of the epistemic responsibilities while simultaneously demarcating it from other responsibilities.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths and limitations. A first strength is the high percentages of consensus of the Delphi panel. Rates of consensus increased in subsequent rounds, indicating that we improved the descriptions of the responsibilities and elements. However, this strength can also be considered a limitation. While most people agree on the importance of abstract and general concepts, their specification often leads to disagreement. For instance, panelists agreed that “to address the big questions of life” was important, but disagreed about which questions ought to be addressed. While this can be problematic, we aimed to formulate general descriptions, as we recognize local, cultural, and institutional factors are leading in how to understand a specific responsibility or element. To specify this further was also beyond the scope of the current study.

A second strength was the rich content of the answers to open questions. The answers of the panelists allowed us to revise, extend, change, and improve our understanding of epistemic responsibilities throughout the course of the study. Furthermore, Delphi studies provide an explicit “decision-making trail” in the form of feedback reports which participants can read before answering each question in the next round (Brady Citation2015).

Third, in epistemology, and philosophy more broadly, it is common to rely only on a priori methods, such as conceptual analysis. The use of empirical methods in philosophy has so far been limited mostly to experimental studies testing people’s intuitions about key philosophical concepts (Knobe and Shaun Citation2017) and the development of measurement instruments for virtues and vices (Alfano et al. Citation2017; Meyer, Alfano, and De Bruin Citation2021). The use of Delphi methods presents a potentially worthwhile methodological innovation for philosophy and the present study can be considered a “proof of concept” pilot.

Our study also has several limitations. One is the size of the panel and its response rate (20%). In our pre-registration, we estimated to include 60–70 panelists while only 46 panelists participated in our study. We expected a higher response rate based on past response rates of Delphi studies (for instance Hall et al. Citation2018 report a response rate of 59%). However, more recent Delphi studies report similar response rates to our study (Labib et al. Citation2021), which may be explained by previous Delphi studies reporting the response rates based on pre-commitment of panelists to participate in a Delphi panel through pre-invitations. Another limitation with regards to the panel is the relatively large share of panelists working at Dutch research institutes (9 out of 46 panelists, see https://osf.io/472fm). This is likely the result of convenience sampling of administrators and pilot testers working in the Dutch context. It could have, moreover, been the result of participation bias, as panelists might have recognized the names of the Dutch authors and were therefore more likely to participate. Both observations could in theory bias the findings of the Delphi study. However, with regards to the panel size and the participating experts, Powell (Citation2003, 378) states that representation depends mostly on the “qualities of the expert panel rather than its numbers.” The elaborate and insightful answers to open questions showed the expertise of panelists. Moreover, other panelists came from various academic disciplines, backgrounds and countries and created a wide array of diverse perspectives. While these considerations suggest that representational imbalances in our panel did not bias the outcomes, it remains important to expand our efforts to include diverse participant groups in future research.

A third limitation is, in part, inherent to qualitative Delphi studies. Those who have different views are less likely to initially respond to a Delphi study if the research question is too far removed from their interests or prior views, and consequently involvement and commitment may be lower (Keeney, Hasson, and McKenna Citation2001). However, qualitative comments, including divergent and opposing views, were guiding in our revisions.

Future research and implications

The results of this Delphi study will be used as input for our next study in the project Epistemic Progress in the University, using co-creation methodology to explore how to further develop the epistemic responsibilities into an implementable tool for universities. The results of the levels serve as a starting point for thinking about what potential levels could entail and how they can be used by universities to reflect on their responsibilities. Practical implications of our research are the use of the framework of the epistemic responsibilities by administrators and policy makers to serve as guidance and to (re)prioritize their efforts to foster the importance of epistemic responsibilities. The flexibility of the framework, where universities can choose which areas they prioritize, is in line with other developments to diversify, recognize and reward the heterogeneity of academic careers and institutes (COARA Citation2022; INORMS Citation2022). Potential application of this study is to contribute to addressing various of the critiques of contemporary dominant neoliberal view on universities (also see, for instance, Barnett Citation2023; Cohen Citation2020; Conell Citation2019; Grant Citation2020 for alternative ideas on the future of universities). For example, use of the framework may strengthen the emphasis on the diversity of epistemic tasks within universities, shared responsibilities across universities, while de-emphasizing competition.In contrast, rankings, as argued by Brankovic et al. (Citation2018), tend to reinforce competition. On the topic of “to address epistemic injustice”/“to promote epistemic justice” no consensus was reached. However, the current discourse focuses on epistemic injustice (Fricker Citation2007; Kidd, Medina, and Pohlhaus Citation2017; McKinnon Citation2016). Since this topic is pressing in current academic debates, we hope that future research on this topic can further explore whether a positive or negative connotation should take center, especially in policy and institutional guidelines. Lastly, as one panelist pointed out, the results of studies like these can easily be corrupted and turned into university rankings. Carefully drafting next steps in researching the future of higher education is recommended and qualitative approaches (that constrain the use of rankings) to “assess” responsibilities of universities are warranted.

Conclusions

We envision the further development and increased understanding of epistemic responsibilities to allow a broader conception of what can be considered a good university – not solely through rankings. Our findings may have the potential to inform higher education policymakers and leadership and all those involved in shaping the future of universities. We hope that these six epistemic responsibilities, as described in our study, can lead to a regained appreciation and shift in what we ought to admire, value, and foster in the university. Ultimately, we hope, leading to improvements in the way epistemic responsibilities of universities are met and how universities regard and evaluate themselves.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Ethical Review Board of the Faculty of Humanities at the VU Amsterdam under dossier number ETCO0034. Panelists received all information on the aims of the study and procedures, data use and privacy policy (https://osf.io/2vwpt), and were asked to give informed consent online via Qualtrics (https://osf.io/9y3mc).

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (5.7 MB)Acknowledgments

We want to thank all 46 Delphi panelists including 13 anonymous panelists for participating in our study. The following panelists have provided consent to have us publicly acknowledge them: Asha Mukherjee, Bart Penders, Britt Holbrook, Conrado Hübner Mendes, David Vaux, Deming Chau, Dorian Karatzas, Duncan Pritchard, Edward Wang, Edwin Were, Eleonora Espinoza, Eunice Kamaara, Florence Nakayiwa, Ginny Barbour, Heidi Grasswick, Jennifer Byrne, Karen Maex, Krishma Labib, Linda Zagzebski, Lise Wogensen Bach, Liviu Andreescu, Mabel Buelna Chontal, Malcolm Macleod, Marcelo Knobel, Mariela Dejo, Oxana Karnaukhova, Pieter Drenth, Remco Breuker, Sarah de Rijcke, Sergio Litewka, Solmu Antilla, Stefan Lechner and Thomas Rewe.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2023.2255826.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alfano, M., K. Iurino, P. Stey, B. Robinson, M. Christen, Y. Feng, and D. Lapsley. 2017. “Development and Validation of a Multi-Dimensional Measure of Intellectual Humility.” PLoS ONE 12 (8): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182950.

- Altbach, P. G. 2013. “Advancing the National and Global Knowledge Economy: The Role of Research Universities in Developing Countries.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (3): 316–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.773222.

- Baker, J., K. Lovell, and N. Harris. 2006. “How Expert are the Experts? An Exploration of the Concept of ‘Expert’ within Delphi Panel Techniques.” Nurse Researcher 14 (1): 59–70. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2006.10.14.1.59.c6010.

- Barnett, R. 2018. The Ecological University: A Feasible Utopia. London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315194899.

- Barnett, R. 2023. “Only Connect: Designing University Futures.” Quality in Higher Education 29 (1): 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2022.2100627.

- Bovill, C. 2020. “‘Co-Creation in Learning and Teaching: The Case for a Whole-Class Approach in Higher Education’.” Higher Education 79 (6): 1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w.

- Brady, S. R. 2015. “Utilizing and Adapting the Delphi Method for Use in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 14 (5): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915621381.

- Brankovic, J., L. Ringel, and T. Werron. 2018. “How Rankings Produce Competition: The Case of Global University Rankings.” Zeitschrift Fur Soziologie 47 (4): 270–288. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-0118.

- Calhoun, C. 2006. “‘The University and the Public Good’.” Thesis Eleven 84 (1): 7–43. Sage PublicationsSage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513606060516.

- Chubb, J., and M. Reed. 2017. “‘Epistemic Responsibility as an Edifying Force in Academic Research: Investigating the Moral Challenges and Opportunities of an Impact Agenda in the UK and Australia Comment’.” Palgrave Communications 3 (1): 1–4. Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0023-2.

- COARA. 2022. “COARA - Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment.” COARA. https://coara.eu/.

- Coelho, M., and I. Menezes. 2021. “‘University Social Responsibility, Service Learning, and Students’ Personal, Professional, and Civic Education’.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (February): 1–8. Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617300.

- Cohen, F. 2020. De Ideale universiteit. https://uitgeverijprometheus.nl/boeken/ideale-universiteit-paperback/.

- Cole, J. R. 2021. “Academic Freedom Under Fire.” Science 374 (6573): 1300–1300. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn5447.

- Collini, S. 2012. What are Universities For?. London: Penguin UK.

- Conell, R. 2019. The Good University: What Universities Actually Do and Why It’s Time for Radical Change. London: Zed Books. https://publishing.monash.edu/product/the-good-university/.

- Copeland, P. 2022. “Stop Describing Academic Teaching as a ‘Load’.” Nature, January. https://doi.org/10.1038/D41586-022-00145-Z.

- Corlett, J. A. 2008. “Epistemic Responsibility.” International Journal of Philosophical Studies 16 (2): 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/09672550802008625.

- Diamond, I. R., R. C. Grant, B. M. Feldman, P. B. Pencharz, S. C. Ling, A. M. Moore, and P. W. Wales. 2014. “Defining Consensus: A Systematic Review Recommends Methodologic Criteria for Reporting of Delphi Studies.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67 (4): 401–409. Pergamon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/ACPROF:OSO/9780198237907.001.0001.

- Grant, B. 2020. “The Future is Now: A Thousand Tiny Universities.” Philosophy & Theory in Higher Education 1 (3): 9–29. Special Issue: Imagining the Future University.

- Hall, D. A., H. Smith, E. Heffernan, and K. Fackrell. 2018. “‘Recruiting and Retaining Participants in E-Delphi Surveys for Core Outcome Set Development: Evaluating the COMiT’id Study’.” PLoS ONE 13 (7): e0201378. Edited by Bridget Young. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201378.

- Holmwood, J. 2014. “The Idea of a Public University.” A Manifesto for the Public University, no. (February): 11–26. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781849666459.ch-001.

- INORMS. 2022. ‘More Than Our Rank | INORMS’. https://inorms.net/more-than-our-rank/.

- Keeney, S., F. Hasson, and H. P. McKenna. 2001. “A Critical Review of the Delphi Technique as a Research Methodology for Nursing.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 38 (2): 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00044-4.

- Kember, D. 2009. “Promoting Student-Centred Forms of Learning Across an Entire University.” Higher Education 58 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9177-6.

- Kidd, I. J., J. Medina, and G. Pohlhaus. 2017. “The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice.” In edited by I. J. Kidd, J. Medina, and G. Pohlhaus, New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315212043

- Kinzelbach, K., I. Saliba, J. Spannagel, and R. Quinn. 2020. Putting the Academic Freedom Index into Action. GPPI. March 2021, https://www.gppi.net/media/KinzelbachEtAl_2020_Free_Universities.pdf.

- Knobe, J., and N. Shaun. 2017. “Experimental Philosophy.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by N. Zalta Edward, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/experimental-philosophy/.

- Labib, K., R. Roje, L. Bouter, and G. Widdershoven. 2021. “‘Important Topics for Fostering Research Integrity by Research Performing and Research Funding Organizations: A Delphi Consensus Study’.” Science and Engineering Ethics 27 (4): 1–22. Springer Netherlands.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00322-9.

- Linstone, H. A., and M. Turoff. 2011. “Delphi: A Brief Look Backward and Forward.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 78 (9): Elsevier Inc.: 1712–1719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.09.011.

- McKinnon, R. 2016. “Epistemic Injustice.” Philosophy Compass 11 (8): 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12336.

- Meyer, M., M. Alfano, and B. De Bruin. 2021. “Epistemic Vice Predicts Acceptance of COVID-19 Misinformation.” Episteme, no. (2021): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2021.18.

- Moher, D., L. Bouter, S. Kleinert, P. Glasziou, M. Har Sham, V. Barbour, A. Marie Coriat, N. Foeger, and U. Dirnagl. 2020. “The Hong Kong Principles for Assessing Researchers: Fostering Research Integrity.” PLOS Biology 18 (7): e3000737. Public Library of Science: e3000737. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.3000737.

- Moore, J. C. 2019. “A Brief History of Universities.” Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01319-6.

- Ordorika, I., and M. Lloyd. 2015. “International Rankings and the Contest for University Hegemony.” Journal of Education Policy 30 (3): 385–405. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.979247.

- Owen, C. 2020. “The ‘Internationalisation Agenda’ and the Rise of the Chinese University: Towards the Inevitable Erosion of Academic Freedom?” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22 (2): 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148119893633.

- Peels, R., R. van Woudenberg, J. de Ridder, and L. Bouter. 2020. “Academia’s Big Five: A Normative Taxonomy for the Epistemic Responsibilities of Universities.” F1000research 8 (July): 862. F1000 Research Ltd: 862. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.19459.2.

- Powell, C. 2003. “‘The Delphi Technique: Myths and Realities’.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 41 (4): 376–382. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x.

- Qualtrics. 2020. Qualtrics. Provo, Utah. https://www.qualtrics.com.

- Rolfe, G. 2013. The University in Dissent : Scholarship in the Corporate University. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203084281.

- Schmidt, R., S. Curry, and A. Hatch. 2021. “‘Creating Space to Evolve Academic Assessment’.” ELife 10 (September): eLife Sciences Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.7554/ELIFE.70929.

- Shore, C. 2010. “The Reform of New Zealand’s University System: “After Neoliberalism”.” Learning and Teaching 3 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2010.030102.

- Silvertown, J. 2009. “A New Dawn for Citizen Science.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24 (9): 467–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.017.

- Spannagel, J., K. Kinzelbach, and I. Saliba. 2020. ‘The Academic Freedom Index and Other New Indicators Relating to Academic Space: An Introduction’. V-Dem Users’ Working Paper Series, no. March.

- The TOP Guidelines Committee. 2014. “Guidelines for Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) in Journal Policies and Practices “The TOP Guidelines“. OSF. September 8, 2023. https://osf.io/ud578.

- van Houtum, H., and A. van Uden. 2022. “‘The Autoimmunity of the Modern University: How Its Managerialism is Self-Harming What It Claims to Protect’.” Organization 29 (1): 197–208. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508420975347.

- VERBI-Software. 2022. MAXQDA. Berlin. https://www.maxqda.com/.