ABSTRACT

Responsible internationalization is a term increasingly used to promote relationship building in a world shaped by the growing impact of global challenges and geopolitical competition. In these changing global conditions, researchers and universities have learned that they need to adhere to an expanded set of research norms. Today these norms include aspects well known to researchers, such as research integrity, academic freedom, openness, research excellence, and research ethics, but also newer aspects related to societal impact, research security, and science diplomacy. However, managing these aspects is complicated by the fact that they are quite contradictory in tandem. Hence the term responsible internationalization has been used to raise awareness of the changing conditions for academic research and induce more responsible research practices. Nonetheless, the term presently lacks systemization and agreed definitions driving clear narratives, well-articulated goals, or structured responses and behavioral changes. This paper seeks to clarify some of the underlying premises and strategies in working with responsible internationalization and a way forward to the development of clearer guidelines.

Background

Responsible internationalization is a term increasingly used to promote relationship building in a world shaped by the growing impact of global challenges and geopolitical competition (Council of the European Union Citation2023). In these changing global conditions, researchers and universities have learned that they need to adhere to an expanded set of research norms (Shih Citation2024a). Today these norms include aspects well known to researchers, such as research integrity, academic freedom, openness, research excellence, and research ethics, but also newer aspects related to societal impact (Global Research Council Citation2019), research security (National Science Foundation Citationn.d.), and science diplomacy (Ruffini Citation2020). However, managing these aspects is complicated by the fact that they are quite contradictory in parallel. For example, how can openness in the research endeavor be maintained when national security concerns increase compliance-based measures and raise suspicions of foul play from foreign governments?

The need to relate to a wider spectrum of aspects has largely been triggered by various government responses (Nature Citation2021) to navigating a rapidly changing world, where greater geopolitical conflict, the deterioration of a global rules-based order, new technological developments, pandemics, and climate change all comprise the new normal. Governments have at their disposal legislative capacity and funding mechanisms to induce behaviors and compliance in national science systems as well as provide directions for national universities and researchers. For instance, the Australian Minister of Education has withdrawn public funding for several research projects deemed not in the best interest of the nation in recent funding cycles (Francis and Sims Citation2022). In the United States (National Science and Technology Council, 2022), the United Kingdom (National Protective Security Authority, 2023) and China (Mallapaty Citation2023) stricter policies and legislation have been enacted in recent years to protect national science systems from foreign appropriation and control. While few countries have yet followed suit with equally tough measures, interdependencies in the global science system mean that the actions of China and the US will impact the rest of the world.

It is against the above backdrop that the term responsible internationalization has gained increased traction in the past few years. The term has been adopted to raise awareness of the changing conditions for academic research and induce more responsible research practices (European Commission Citation2022; Council of the European Union Citation2023). The latter may for instance entail curtailing behaviors in international collaborations that risk leading to ethics dumping (Shih, Gaunt, and Östlund Citation2020), double dipping (Silver Citation2020), or direct dual use of research (UUK Citation2020), but also avoiding too much of a cooling-down effect on international research collaboration. Nonetheless, the term presently lacks systemization and agreed definitions driving clear narratives, well-articulated goals, or structured responses and behavioral changes. This commentary seeks to clarify some of the underlying premises and strategies in working with responsible internationalization and a way forward to the development of clearer guidelines.

Premises of responsible internationalization

The term responsible internationalization is already in established use by universities, research funders and policymakers in many parts of the world. However, to intentionally raise the level of responsibility in international collaborations, knowledge needs to be systematized and methods for implementation developed. Researchers, universities, state agencies, government officials, and politicians need to gain better knowledge of what needs to be handled, why this must be done and how. The work required relates to managing the complex spectrum of considerations from openness to securitization. Here it is important to note that while researchers and university administrators generally have the ambition to act responsibly, right cannot automatically be told from wrong with respect to navigating a complex portfolio of considerations.

Responsible internationalization can therefore be seen to develop reflective ability concerning the broader set of conditions that researchers and universities need to handle today. Risk management is of course a part of this larger palette, but it is important to note that the main motivation for conducting risk analyses should be to maintain international collaborations and not to end them. In a minority of cases international collaborations should not be initiated or continued. For instance, this can be when there are sanctions involved, direct dual-use risks are presentFootnote1 or grave transgressions of ethics or individual rights occur. Yet the rationale for handling such extreme cases cannot determine how most international collaborations are approached.

Responsible internationalization should also focus on the relationship level. Research is seldom conducted in isolation – advanced research is often performed in international networks, as it requires complementary capabilities, excellent scientists, and resources. Moreover, research dealing with global challenges also needs to have a global outlook and be internationally inclusive to really have meaningful impact. Cumulatively, cross-border collaborations increasingly account for a bigger share of research currently conducted. Hence not addressing responsibility in international relationships would amount to missing a substantial part of the research endeavor. Here notions such as research security, trusted research (National Protective Security Authority, 2023), and sometimes even science diplomacy differ, since they focus on unilateral goals, for instance from a national perspective. Responsible internationalization offers insights that counter unilateral views and zero-sum logic.

Lastly, responsible internationalization focuses on agency rather than compliance. As such it offers possibilities to address issues encountered by individual researchers and research groups involved in international collaborations. Generally, rules and legislation are established in the aftermath of repeated transgressions with adverse impact and these are thus reactive. A focus on responsibility presents epistemic communities, research administrators, or university managements with opportunities to respond proactively to research behaviors perceived as “irresponsible” by university collectives, policymakers and politicians. At the same time, a positive narrative may be created around the academic sector’s actual efforts to improve the situation. This may further lead to the nuancing of some of the more protectionist narratives currently present in the general debate on the role of science in society, where national competitiveness and sovereignty are emphasized before any other goals.

Based on these premises a working definition follows: Responsible internationalization focuses on the discretionary responsibilities that researchers have when building international relationships. This means that researchers need to develop their ability to reflect on contextual factors so that a complex portfolio of risks encountered when national borders are crossed can be proactively and realistically managed. For responsible practices to be effective they also need to be co-created in relationships, rather than representing the expectations of one side only.

Working with responsible internationalization

Addressing a set of complex norms in parallel requires a simplified understanding of the issues that need to be managed. It is evident that good practice in international research collaborations is based on the need not only to consider usual aspects such as research integrity and ethics, but also pressures for research securitization that increasingly shape the current landscape in which international research collaborations are promoted and limited. Thus, there is now much greater emphasis on risk management in the academic sector (see Shih, Gaunt, and Östlund Citation2020), as requested by state actors as well as by universities.

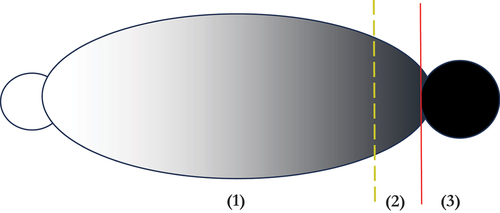

Delineations are helpful to address issues related to responsibilities involved in the balancing of risks with the opportunities presented by international research collaboration. As a starting point for deriving institutional approaches to manage such risks, illustrates possible dividing lines and three domains into which international collaborations may be embedded (from Shih Citation2024b).

The black area represents cases that clearly cross normative boundaries. Such cases may be related to serious instances of ethics dumping, direct military uses of scientific findings or potential for such use, due to the user being a military institution,Footnote2 or grave human rights violations.Footnote3 The gray area is characterized by the opportunities and challenges that arise in international collaborations when research is conducted in different national and institutional contexts. That is, national and institutional variations create differences that must be managed in international research collaborations. These may either be problematic (e.g., when some types of scientific experiments are legal in one country but illegal in another) or more straightforward (e.g., language differences necessitating translation or interpretation) (Shih, Gaunt, and Östlund Citation2020). It is important to underline that most international collaborations take place in the gray area. However, there are different shades of gray and those bordering on black, as illustrated by the yellow dotted line, are much more problematic than those adjacent to the white. Hence, the handling of gray areas will also differ depending on their nature, problem, degree of seriousness, and frequency. The white area may represent unproblematic, reciprocal, and responsible international collaborations where exchanges occur in institutional contexts which have been harmonized to such a level that legal differences, and cultural and linguistic barriers are generally non-existent.

International collaborations that cross red lines (3), either due to transgressions of laws or grave violations of ethics or human rights, must be suspended.Footnote4 Identifying such cases may pose different challenges, depending on what the problem is. Espionage investigations are the task of intelligence services. Higher education institutions do not have the authority to deal with foreign actors who pose a national security threat. Grave cases of ethics dumping can be difficult to uncover. A whistleblower function may be necessary to that end, and research funders can also identify inappropriate projects during the appraisal process. However, it is important to emphasize that transgressions of laws or grave violations of research standards are uncommon, and the proportionality of responses is extremely important to consider (see Shih and Forsberg Citation2023). Aggressively looking for cases in the black area can lead to an erosion of the very democratic institutions, openness, and academic competitiveness one seeks to protect. Raising awareness and providing information on the responsibility of researchers and universities regarding grave violations should, however, be an active strategy.

More importantly identifying responsible practices in the gray area should be prioritized. International collaborations that lie in the gray spectrum (2) and approach the red lines are the most difficult to manage, e.g., when research might constitute grave human rights violations but continue because they are not illegal. Management includes awareness of red lines, understanding of contextual factors, and reflexive capability for navigating complex environments. Decision-making based on developing guidelines for discretionary responsibilities must be emphasized. A range of actors must be integrated such as research funders, epistemic communities, authorities, and university management at different levels. At the same time, academic freedom and institutional autonomy must be respected unless red lines are violated. When collaborations stay around the middle of the gray area (1), the focus should be on managing opportunities, reciprocity, and freedom under responsibility.

Conclusions

This paper has provided a definition of responsible internationalization, which emphasizes the discretionary responsibilities of researchers when undertaking international research collaborations. These discretionary choices should address in parallel issues related to risks, reciprocity and building responsible practices in relationships rather than unilaterally. Important aspects of building responsible practices in international collaborations must be understood, including contextual factors, red lines juxtaposed with discretionary decision-making, and relationship dynamics.

Disclosure statement

The author is a senior adviser at The Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Some research is intended for dual-use purposes, such as for example projects funded by NATO.

2. It should be noted that some funding of science and technology is intended for dual-use purposes, e.g., NATO’s Innovation Fund.

3. What constitute human rights violations in scientific research can be found at: https://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/reports/Scientific_Freedom_Human_Rights.pdf.

4. These might also need to be handled by authorities or the legal system.

References

- Council of the European Union. 2023. “Knowledge Security and Responsible Internationalisation.” https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-8824-2023-INIT/en/pdf.

- European Commission. 2022. Tackling R&I Foreign Interference: Staff Working Document. Brussels: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation Publications Office of the European Union.

- Francis, A., and A. Sims. 2022. Why We Resigned from the ARC College of Experts After Minister Vetoed Research Grants. Melbourne: The Conversation.

- Global Research Council. 2019. Statement of Principles Addressing Expectations of Societal and Economic Impact. https://globalresearchcouncil.org/fileadmin/documents/GRC_Publications/GRC_2019_Statement_of_Principles_Expectations_of_Societal_and_Economic_Impact.pdf.

- Mallapaty, S. 2023. “China is mobilizing science to spur development — and self-reliance.” Nature 615 (7953): 570–571. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00744-4.

- National Science Foundation. (n.d.). “Research Security at the National Science Foundation.” https://new.nsf.gov/research-security.

- Nature. 2021. “Editorial - Protect Precious Scientific Collaboration from Geopolitics.” Nature 593 (7860): 477. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01386-0.

- Ruffini, P. 2020. “Conceptualizing science diplomacy in the practitioner-driven literature: a critical review.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communication 7 (1): 124. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00609-5.

- Shih, T. 2024a. “Recalibrated Responses Needed to a Global Research Landscape in Flux.” Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance 31 (2): 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2022.2103410.

- Shih, T. 2024b. “The Role of Research Funders in Providing Directions for Managing Responsible Internationalization and Research Security.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 201:1–10. Article 123253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123253.

- Shih, T., and E. Forsberg. 2023. “Origins, Motives, and Challenges in Western–Chinese Research Collaborations Amid Recent Geopolitical Tensions: Findings from Swedish–Chinese Research Collaborations.” Higher Education 85 (3): 651–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00859-z.

- Shih, T., A. Gaunt, and S. Östlund. 2020. Responsible Internationalisation: Guidelines for Reflection on International Academic Collaboration. Stockholm: STINT.

- Silver, A. 2020. “Exclusive: US National Science Foundation Reveals First Details on Foreign-Influence Investigations.” Nature 583 (7816): 342. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02051-8.

- UUK. 2020. “Managing Risks in International Research and Innovation.” https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/sites/default/files/field/downloads/2022-06/managing-risks-in-international-research-and-innovation-uuk-cpni-ukri_1.pdf.