ABSTRACT

Literary translation plays a crucial role in the internationalisation of cultural and publishing markets. It constitutes a marker of status in the economic global system, therefore contributing to cultural diplomacy. As such, source-culture institutions often offer support policies to help disseminate their literatures abroad. Focusing on contemporary multilingual Spain, this paper investigates the translation policies of the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia and Valencia, where literature in Spanish coexists with the literatures written in the co-official languages in these regions, paying special attention to the translation grants funding schemes. Through the comprehensive study of the different stages of this funding scheme – from the design and publication of the translation grants to the allocation of funding, also including the participation of the four funding institutions at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2018 – we combine quantitative and qualitative methods with ethnographic research to offer unique insights into the extent to which translation grants from each of the source cultures can successfully contribute to the internationalisation of literatures in these stateless cultures and less translated languages. Our research also offers revealing information about the particularities of the collaboration between institutional funding bodies and the private publishing industry in these regions.

1. Introduction: cultural diplomacy and literatures in translation

Literary translation plays a crucial role in the internationalisation of cultural and publishing markets – not only does it influence the development of a literary field and the construction of any literary canon, but it also constitutes a marker of status in the economic global system. As such, source-culture institutions often offer support policies to help disseminate ‘their’ literatures abroad. These could be understood as part of a broader cultural diplomacy strategy, or ‘a government’s international outreach program […] that varies from country to country and is usually dependent on political motivation, intentions, and histories’ (Flotow, Citation2018, p. 193). If language is often considered a crucial part of cultural diplomacy, the same could be said of literature and literary translation.

Extending the traditional view that ‘understanding and respect’ for the other is crucial for cultural diplomacy (Goff, Citation2013, p. 419), there seems to be general consensus among scholars in the field (Gienow-Hecht & Donfried, Citation2010; Goff, Citation2013) that cultural diplomacy ultimately seeks to exert influence over that other through seductive cultural means. Branding (image) and promotion are key: they enlarge the other’s understanding of the culture in question and, subsequently, enable trading opportunities and business.

However, efforts required from different cultures and literatures to brand themselves and exist internationally differ ostensibly, and the global language network (as defined by Ronen et al., Citation2014) seems to play a key role in these divergences. Powerful international players will easily become dominant given that they are often linked to ‘disproportionately influential languages’ (Ronen et al., Citation2014, p. 616) that facilitate both direct and indirect connections among most of the world’s other languages. On the contrary, less powerful players not linked to global languages and connections will find it harder to gain influence and prestige abroad. As Ronen et al. argue,

[I]t is easy for an idea conceived by a Spaniard to reach an Englishman [sic] through bilingual speakers of English and Spanish. An idea conceived by a Vietnamese speaker, however, might only reach a Mapudungun speaker in south-central Chile through a circuitous path that connects bilingual speakers of Vietnamese and English, English and Spanish, and Spanish and Mapudungun. In both cases, however, English and Spanish are still involved in the flow of information, indicating that they act as global languages (Ronen et al., Citation2014, p. 617)

Nevertheless, the co-official status of these languages grants their governments access to certain resources (albeit limited) for promotion, branding and cultural diplomacy at a non-state level, thus having the opportunity to engage in ‘stateless nation-building’ (Keating, Citation1997, p. 659). This process of stateless nation-building legitimises the markers of collective identity it draws upon, ultimately helping consolidate them at home. The international dimension of this process requires an external policy which is not only targeted towards language and culture development, but also focused on economic needs, promoting trade and investment in the face of the international market, in this case, the book industry (Keating, Citation1997, p. 708). Examples of this include the design of specific supports for translation abroad and the participation at international book fairs, inasmuch as they constitute privileged spaces for cultural diplomacy and soft power (Villarino Pardo, Citation2014, p. 136) as well as offer an opportunity for capital conversion (McMartin, Citation2021, p. 279).

2. Cultural policies in multilingual Spain: aims and methodology

Framing our research in contemporary multilingual Spain, where ‘45 per cent of the population live in a territory where an autochthonous minority language is spoken’ (Brohy et al., Citation2019, p. 25), this article focuses on literatures in co-official languages in those stateless nations (see Bermúdez et al., Citation2002) in which literature written in Basque, Catalan/Valencian and Galician coexists with literature in Spanish.Footnote2 Since Spain is nowadays a decentralised nation-state with respect to certain competences (e.g. culture, education and health), regional governments have the ability to decide on these matters, including language policy.

To briefly summarise the scope of these three languages (for more details, see Oficina para las lenguas oficiales, Citation2019), Basque is a pre-Indo-European language spoken by around one million people that holds co-official status in the Basque Country and Navarra, where it is the native language for 33.7% and 14.6% of the population respectively. Both Catalan/Valencian and Galician are Romance languages. Galician is spoken by around three million speakers and is co-official in Galicia, being a native language for 82.8% of the population. Catalan/Valencian is spoken by some eleven million people and holds co-official status in Catalonia (native language for 55.5% of Catalans), the Balearic Islands (42.9%) and Valencia (35.2%). Catalan spoken in Valencia is sometimes referred to as Valencian, a new coinage introduced in 1995 by the Valencian government. In academic circles, however, there is strong consensus that Catalan and Valencian are two denominations for the same language. The ambiguity regarding this term and its relation to Catalan has led to linguistic and political controversy with particular disputes taken to court (see Ortuño, Citation2017 for some examples). For the purposes of this research, Catalan/Valencian will be used when referring to both varieties of the language in general, while each of the denominations will be used separately when we speak about each of them specifically.

For literatures in these co-official stateless languages, translation has the potential to be a powerful cultural diplomacy asset, contributing to the consolidation of their status (Branchadell & West, Citation2005) and enabling them to access the world literary system (Casanova, Citation2007), reach new readerships and participate in literary exchanges. Given that these regional governments have full competences in terms of cultural and language policy, and stemming from the assumption that financial support is decisive for successful cultural diplomacy (and thus, for the promotion and visibility of their literatures both abroad and within the nation-state),Footnote3 they have been regularly subsidising translations from Basque, Catalan/Valencian and Galician into other languages – including Spanish – since the 2000s (see Bacardí, Citation2019 for an overview of translation policies from/into official languages in Spain). Despite this financial effort, little is known about how successful these initiatives are, especially from a comparative perspective that considers the different stages of the funding schemes along the process, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. To fill out this research gap, we will investigate translation support policies aimed at the internationalisation of literatures in Basque, Catalan/Valencian and Galician, paying special attention to the translation grants offered by the relevant regional governments. Although books in these languages are also eligible for the yearly translation grants offered by the Spanish Ministry of Culture, we are not including these grants in our study due to their limited effect on the literatures in the co-official languages.Footnote4

With this in mind, our two-fold aim is to assess to which extent translation grants from each of the source cultures can be considered successful as well as to identify best practice. We argue that, in order to measure success, it is essential to study the different stages of the funding scheme in a comprehensive way, from the design and publication of the grants to the allocation of funding, and the staging of each of these communities at international book fairs. For this to be feasible, the specific year of 2018 was selected as a case study. Firstly, a qualitative textual analysis of the calls for applications published in 2018 will be undertaken in order to better understand the different priorities in the grant design. This will be followed by a quantitative analysis of the funds allocated to the different publishers who applied that year, in order to ascertain the successes and challenges of these initiatives.Footnote5 Finally, an account of ethnographic research carried out at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2018 will be offered to illustrate how the four institutions promote and present their translation grants in situ and how they collaborate and support the private sector regarding the internationalisation of their literatures.

3. Translation support initiatives from regional institutions in 2018

As mentioned above, regional governments with co-official languages have competencies in what concerns translation policy, which they approach in different ways. In the case of Catalan and Basque, two key institutions have been set up to take care of the promotion of the language and culture both within their borders and abroad. The Institut Ramon Llull (hereafter, Llull), created in 2002, is funded by the government of Catalonia, Barcelona City Council and the government of the Balearic Islands and has been offering translation grants for translations from Catalan and Aranese – co-official in some parts of northern Catalonia – into other languages since the year 2003. The Etxepare Euskal Institutua (hereafter, Etxepare) was created in 2007 and started offering translation grants in 2010 both for books originally written in Basque and for books by Basque authors in Spanish.

Galicia and Valencia do not have specific institutes in charge of the promotion of their literatures abroad. In Galicia, it is the Galician government, the Xunta de Galicia (hereafter, Xunta), who offers specific grants for translation since 2007. These grants have undergone changes and have been discontinued at times, offering a single call for two years (see Montero Küpper, Citation2017). In Valencia, it is also the government, the Generalitat Valenciana (hereafter, Generalitat) who manages these translation grants. They were also discontinued and were only reinstated in 2017 following a change of government in the region two years earlier. Although in principle books in Valencian are eligible for the Llull grant for translations from Catalan, it is unclear whether controversy surrounding the two denominations (as explained above) may create problems.

In what follows, we will provide an overview of the main supports offered in the four territories, in order to contextualise our study and focus on the active initiatives in 2018, the year we are using as a case study. Among many ad hoc initiatives offered in the year 2018 (e.g. a translation award, workshops, talks and other one-off events), the Llull also provided four established supports (Institut Ramon Llull, Citation2018): first, funds for the translation of excerpts and the production of booklets for distribution abroad; second, grants to pay for residential visits of literary translators and international publishers to Catalonia; third, grants for the translation of books into other languages; and fourth, travel grants for writers and translators to promote the translated works at festivals and literary events. As an institution, that year the Llull also participated in eleven national and international book fairs. In 2018 the Etxepare offered support for writers to travel and participate in literary fairs and festivals, and in other international events, as well as offering an award to the best translation from Basque of the year and a competitive call for grants for the translation from Basque into other languages. On top of these supports, grants for participation in fairs for publishers were also provided, and the Institute participated in three national and international book fairs (Euskal Etxepare Institutua, Citation2018). The Xunta also offered competitive supports for the translation of Galician literature, as well as acting as institutional representative in book fairs, participating in five national and international fairs in 2018 (Xunta de Galicia, Citation2018). The Galician government also provided specific support for the creation of promotional booklets and catalogues of Galician children’s literature available for translation. In the case of Valencia, the Generalitat published a call for grants for the translation of Valencian literature and participated in book fairs as an institution in 2018.

This brief introduction shows that the approaches to supporting translation from all four funding bodies are significantly different. The most important of these initiatives, and the only ones available in all four cases, are, first, the competitive grants available for publishers to fund translation into other languages, including Spanish and, second, the participation of these institutions in book fairs. Since these initiatives are comparable across all the contexts studied, they are particularly helpful to understand the most successful practices and the challenging areas regarding translation policy in the stateless literatures of Spain. Focusing on the year 2018, the comparative analysis presented in Section 4 will shed light on these areas. We have not delved into specific information about direct or indirect translation (Assis Rosa et al., Citation2019) in our corpus to understand translation flows; for the purpose of this paper, what must be emphasised is that the books have been presented as written in each of the languages of study in the source culture and this identification is preserved in the translation.

4. A comparative analysis of support initiatives in 2018

4.1. Competitive translation grants: a textual analysis of the calls for applications

This section provides a comparative analysis of the four different calls for grants that these institutions announced in 2018 and their characteristics in order to ascertain, firstly, what aspects of the call for grants might have impacted the final numbers that will be analysed in Section 4.2 and, secondly, what aspects may be considered best practice, and which might create additional challenges. These data were extracted from a variety of primary sources (see BOPV, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; DOG, Citation2017, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; DOGC, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; DOGV, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Institut Ramon Llull, Citation2018).

As shown in , the highest amount of support is offered by the Llull, which budgeted a total of €220,000 for the translation of works originally written in Catalan into other languages. The second highest funding body is the Xunta, which established a total of €80,000 dedicated to translation from Galician into other languages (in theory, 40% of the total €200,000, although this budget is not independent, so the money can be transferred to translation into Galician). The Generalitat published grants budgeted at €50,000 for both directions (into and from Valencian), whereas the Etxepare allocated a budget of €39,000 for translations of Basque literature (both in Spanish and Basque) into other languages. In terms of the amount allocated to each specific project, the Catalan grants cover up to 100% of the project, with a maximum of two applications per publisher, whereas the Etxepare grants cover a maximum of €8,000 per project and a maximum of €12,500 per applicant. The Xunta and the Generalitat either establish a very high maximum of projects per publisher or do not establish a maximum at all.

Table 1. Allocation of funds in the four different calls for applications.

Concerning the timeframe for submissions, shows that the Llull offered three months for the application process in 2018, whereas the Etxepare, the Xunta and the Generalitat all offered between 20 and 30 days. In addition to this, the Llull grants are the only ones that allow applications in English, whereas the three other institutions only allow submissions in their co-official languages and Spanish. The Etxepare, however, does offer an English version of the call for grants on their website, as does the Llull. These two versions are, furthermore, simplified and focused on a lay reader, and thus do not use the administrative language present in the official calls for applications. Neither the Xunta nor the Generalitat provide a layperson version of their calls in their websites, and no English version is available either.

Table 2. Timeframe for submissions and working languages.

The provisions made for the submission of applications by publishers are an important aspect concerning the accessibility of these grants (see ). While self-employed people have the option to present a hardcopy application, online submission is mandatory for commercial entities. For them to access the official online platforms, however, an official digital certificate is needed, which can only be obtained by entities with fiscal residence in Spain. As an alternative, the Llull offers a specific accreditation for foreign publishers that can be requested through their website – through the same place where the summary of the grants is published, along with clear instructions as to how to proceed. The whole process is done online, and the accreditation is issued in a period of 48 hours and is valid for five years unless there are changes. In the case of the Etxepare and the Xunta, no specific accreditation is given, but an exemption is provided for foreign publishers to send their application in person or by mail instead of online, in order to facilitate their participation. In the Generalitat grants, no provision is made for publishers who do not have access to any of the electronic signature systems needed to enter the administration’s digital platform.

Table 3. Submission of applications by foreign publishers (with no fiscal residence in Spain).

From the examples presented above, it derives that all four funding bodies have different approaches to the design of their grants. Firstly, the Llull and the Etxepare establish independent supports for the translation of their literatures into other languages, whereas the Xunta and the Generalitat include translation from and into their languages in the same support, leading to a potential imbalance in the amount of funds allocated to the former. On top of this, neither the Galician nor the Valencian grants establish reasonable limits to the number of projects a publisher can apply for, thus potentially limiting the variety of publications and readerships reached. Furthermore, neither providing clear instructions on their websites nor a translation into English of the call for grants in the case of Galicia and Valencia may hinder efforts to attract foreign publishers. This is complicated further by the lack of provisions for applications in English as well as the difficulty of access for publishers with no fiscal residence in Spain in all cases save for the Llull supports.

The next section will offer an overview of the funds allocated in all four cases, with the aim to ascertain how the design of these grants may have affected the projects that were ultimately submitted and accepted. This will enable an understanding of the successes and challenges in each of the cases.

4.2. The grants in figures: a quantitative analysis of books funded

The textual analysis of the grant design showed that some of the grants were specifically allocated to translation into other languages whereas others combined translation in both directions. However, the fact that an amount had been budgeted for these competitive grants does not mean it would be eventually allocated in full. As shows, the budget from the Llull was allocated almost entirely (99.61%) amounting €219,153 for the translation of 87 books into other languages. The Etxepare follows the same trend (90.75%), although in this case, the absolute figure is considerably lower, both in terms of the amount of €35,395 and the number of books funded (14 from Basque and 1 from Spanish). The amount allocated by the Xunta was similar to that of the Etxepare, with €35,218.41 for 17 books, but this represents less than half of the total initially budgeted (44.02%). The Generalitat allocates a very small percentage (7.41%) of its funds for translation from Valencian into other languages, that is, €3,707 in the context of a total of €50,000 budgeted for both directions.

Table 4. Funds budgeted and allocated for translation into other languages.

Analysing the languages into which translations from these literatures are most funded reveals the flows of translation, as well as the variety of territories and readerships reached. The diversity of publishers funded is also a good indicator of a healthy system, in which supports are visible abroad and attract publishers’ interest. It can show whether there is a broad pool of applications for a particular language, or whether a high number of books is translated by one publisher only.

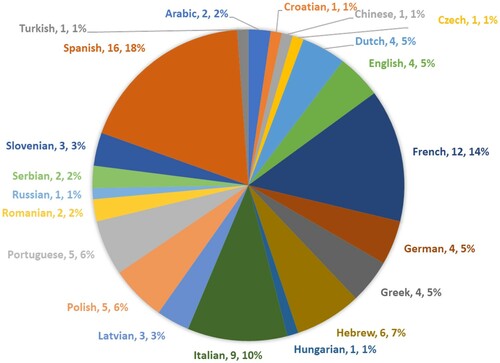

The Llull allocated funding to 87 books, mostly works translated into Spanish (16), followed by French (12) and Italian (9). Behind those, Hebrew had 6, Polish and Portuguese saw 5 funded projects each, while English, German, Greek and Dutch had 4. The rest of books (18) were translated into 11 languages. A total of 74 publishers were funded ().

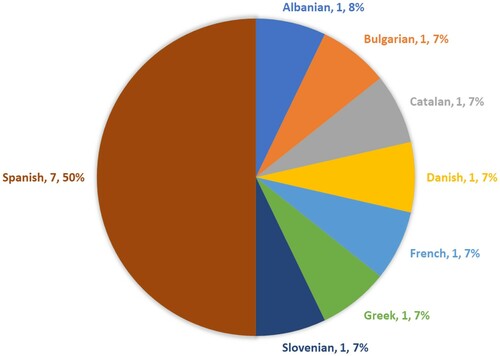

In the case of Basque, 50% of the books funded are translated into Spanish, whereas 6 others are translated into other small European languages, including Catalan (). The landscape of publishers into Spanish is varied, with 6 different publishers funded for the translation of 7 works.

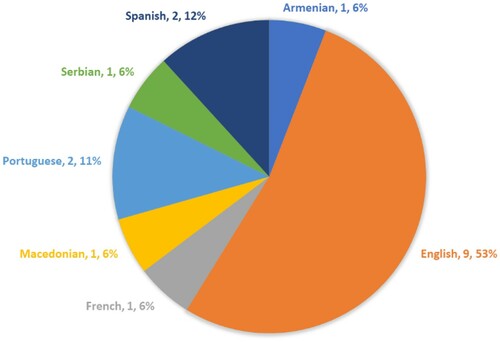

English is clearly the favoured language in 2018 when it comes to funded translations from Galician (), amounting 9 books out of the total 17, brought to the market by 3 publishers. Spanish and Portuguese follow behind with 2 funded projects each.

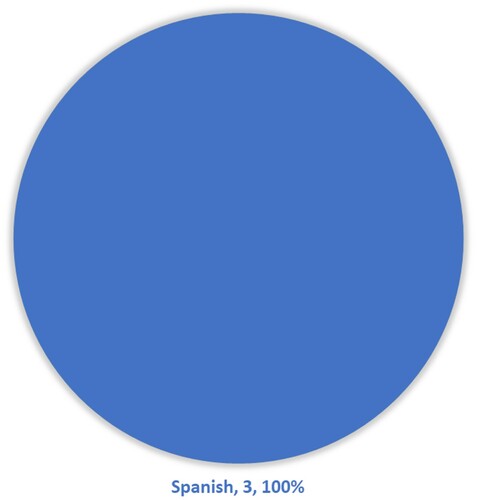

In the case of the Generalitat, 2018 translation grants only allocated funds to 3 translation projects (), all three for translations into Spanish and published by the same publishing company, which is headquartered in Valencia.

This section showcases a clear difference between the priorities presented by the Llull and the other three territories. It seems clear that the internationalisation of Catalan literature beyond the territory of Spain is a high priority in the case of the Llull, which granted supports to a variety of publishers in different languages and territories, highlighting the health of the system and the success of the promotion of the grants. As a matter of fact, it seems remarkable that there are no translations from Catalan into other co-official languages in Spain. On the other hand, it is also surprising to see that, despite the focus on English-speaking markets of the UK and US stated by the Llull (Mansell, Citation2019, p. 129), English is only the seventh language funded in 2018, thus indicating that institutional priorities might not yet have caught up with the design of the grants.

The Etxepare grant allocation shows that there is a varied pool of applicants for the translation of Basque literature into Spanish, showcasing that funded books in Basque are mostly received within the Spanish territory, following a general trend already identified (Manterola Agirregazalaga, Citation2011). These Spanish translations, however, can then be used as a launching pad to gain visibility not only in the Hispanic world, but also abroad. The Extepare grants also highlight that other small languages are prioritised over global ones. It must be noted here that Spanish translations are sometimes used as intermediary texts before indirect translations into other target languages are produced, especially in infrequent language combinations with Basque – a solution that is often championed in other territories, e.g. Scandinavia, via other global languages such as English (see Alvstad, Citation2017). However, in this case and despite the hegemony of English in the publishing market, none of the books funded in 2018 are translated into this language. Therefore, Spanish is the (potentially intermediary) ‘global language’ into which literature in Basque is translated, notwithstanding the differences in power and status between these two languages that coexist (and compete with each other) in the Basque Country.

English is, however, present in the Xunta grants, where it makes up for 9 out of the 17 books funded: this, in principle, indicates a focus on internationalisation. In context, however, only 3 publishers received funds for these translations, demonstrating that the pool of publishers applying for these grants is still small, and thus that they may still be widely invisible. Furthermore, in the Xunta and the Generalitat cases, the lack of separation between translation directions means that a much smaller percentage of the funds was allocated to translation into other languages: this showcases the focus on increasing publications in Galician and Valencian, indicating more fragile systems still focused on the normalisation of their languages, as we have stated elsewhere (Castro & Linares, Citation2019a). The Valencian case is perhaps the most paradigmatic of this trend, as only Valencian publishers accessed the grants in 2018, with only 3 translations from Valencian into Spanish funded. This suggests that these funds are still in their infancy and that the priority when it comes to translations into other languages is to visibilise Valencian literature within the context of the Spanish territory, as well as to potentially use the Spanish language as a vehicle for potential future translations into other languages. This goes in line with what McMartin already observed in his study of the Flemish Literary Fund translation supports (Citation2019) in regard to maximising each title’s capital potential by focusing on central languages: on English as a hyper-central global language, and on German and French as central, neighbouring languages. In the case of the languages of study, a similar pattern is observed in the use of English and Spanish as the main languages into which translation is funded.

4.3. Grants in action: participant observation at the Frankfurt Book Fair (FBM)

Data presented so far has offered revealing findings. Yet, further contextual analysis is needed to provide a more nuanced understanding of the processes involved throughout the different stages of the funding schemes examined. An ideal way of obtaining meaningful contextual data is incorporating an ethnographic approach, a methodology that is gradually gaining ground in translation studies,Footnote6 especially in the wake of the social turn. Inspired by the ethnographic turn in language policy studies that claims for ‘macro–micro connections by comparing discourse analysis with ethnographic data collection in some local contexts’ (Johnson, Citation2009, pp. 139–140), we wanted to complement our previous data with a study about how the four institutions staged their participation at the Frankfurt Book Fair (10–14 October 2018), considered the largest and most important trade book fair for international deals (Villarino Pardo, Citation2016, p. 77). The participant observation and field note collection carried out during the first two days were followed by personal interviewsFootnote7 with governmental translation policymakers and representatives from the different publishers’ associations, in some cases conducted at different locations in the months after the event. A further advantage of this approach, as Canagarajah (Citation2006) argues in relation to linguistic ethnography, is that by providing feedback to stakeholders on the various stages of the process (see for example Castro, Citation2021; Castro & Linares, Citation2019a, Citation2019b), it has the potential to ultimately contribute to shaping policy.

In 2018 the Llull, Etxepare, Xunta and Generalitat attended the FBM with an institutional stand, which suggests they all share an understanding of the fair as a ‘metaphor of a literary field at a global scale (…) a space of power struggle to reach a position of greater centrality’ (Villarino Pardo, Citation2016, p. 90). The FBM is primarily a business event for publishers, providing an opportunity for the buying and selling of translation rights. Funding institutions, therefore, could be expected to offer tailored support to publishers from their own literary contexts, bearing in mind their specific needs and particularities.Footnote8 This support may include financial assistance to travel to fairs as well as help to negotiate translation rights by (a) offering a space for business meetings to take place, (b) promoting their translation grants in an effective way and (c) directly interacting with foreign publishers to showcase literature in the different languages.

Regarding the institutional stands at the FBM, expenses were covered following very different approaches. For Galicia, the Xunta paid for and managed the stand, simply making it available for Galician publishers. Officials from the Xunta were at the stand ‘for anyone interested in finding out more about Galician literature’, although English was not spoken. Due to a ‘lack of funding for travel’, only 2 Galician publishers visited the fair, with one of them paying for its own stand. For the Basque Country, the Etxepare paid for the stand and for a Basque/Spanish-English interpreter who helped with meetings, letting Basque publishers run it. No representatives from Etxepare visited the fair as they considered that ‘the FBM is for publishers to do business’. A total of 7 Basque publishers, who were able to travel thanks to institutional funding, used it to hold previously arranged meetings with different international presses, although ‘mainly to buy [rather than sell] translation rights’. Closer collaboration between publishers and institutions was evident regarding literature from Catalonia and the Balearic Islands, as the stand was paid and managed by both the Llull and the associations of Catalan publishers. As a matter of fact, presses and institutions ‘work hand in hand’. A total of 22 publishers and 27 literary agents held meetings to negotiate translation rights. Involvement of the Llull meant that 5 officials were actively using the stand alongside publishers to hold 180 previously arranged meetings with specific foreign publishers. In practical terms, the Llull worked as a literary agency representing all books written in Catalan. In the case of Valencia, both the Generalitat and Valencian publishers paid for and managed the stand, which was used by the 11 publishers attending thanks to institutional funding, and the 16 Valencian authors paid to attend to ‘help visibilise Valencian literature at home’. Officials were also present at the stand to provide general information about Valencian literature and to help organise events with guest writers, which nevertheless were not attended by foreign presses. The President of the Valencian regional government and two other senior officials also visited the stand, together with a number of journalists who reported back about the participation of Valencia in the FBM in local and national media (see Geli, Citation2018).

Although in 2018 all four institutions published a call for translation grants, the way they were promoted varied ostensibly. In the Galician case, a literal English translation of the legal text with the call was available as paper copy on the stand, without attracting bystanders’ attention. No information was provided about how to apply or about when the new call would be available. In the Basque case, a user-friendly summary translation of the grants was available in English, published on page 5 of the catalogue of translation rights that publishers had produced, with Etxepare funding, to be used in their meetings. However, the information was vague, with no specific details about how to apply from abroad or dates of publication of the new call. The Llull produced a user-friendly, clear and informative booklet entitled ‘Translation grants from Catalan’ with specific details about how to apply from abroad, and offered help to solve any queries. The call was open at the time of the fair, meaning that foreign publishers could apply on the days after the event. Two catalogues of translation rights (one for fiction and one for non-fiction) with a synopsis of each book in English translation were created by the Llull, and used in the meetings their officials were holding with international presses, preselecting a few books to ‘tailor the catalogue to the needs and tastes of foreign publishers’. Finally, the Generalitat did not actively promote the translation grants available for Valencian literature, with no copies provided in situ, as the grants are ‘run and funded by a different governmental department’.

The observations presented above show that a degree of collaboration between the publishing industry and the administration is crucial for international deals to happen. Assistance to help small publishers travel to the FBM (as the Llull, Etxepare and Generalitat do), so that they can make use of the institutional stand, is the sine qua non condition to facilitate their engagement in selling translation rights, as otherwise travelling to Frankfurt to sell one or two books would mean operating at a loss. The contrary leads to using taxpayers' money to have a stand with no significant activity (Xunta). Devoting public funding to promoting specific writers and to cover for institutional visits (Generalitat) also seems to lack purpose, as this is not what foreign publishers are interested in. When it comes to an effective promotion of the grants, it is vital not only to offer attractive and user-friendly booklets (Llull and Etxepare), but to include detailed practical information about how and when to apply (Llull). Having the call opened at the time of the fair and acting de facto as a big literary agent representing all books in the language (Llull) is indeed added value. It must be considered, though, that ‘Catalan Culture’ was Guest Honour of the FBM in 2007, and this may have set the starting point for this powerful model of collaboration between the industry and the administration (see Woolard, Citation2016b).

5. Concluding remarks

Translation support policies have a key role in enhancing the visibility of co-official stateless literatures in the international arena and granting them a higher status in their own societies. In order to understand the successes and challenges of these policies in the context of Basque, Catalan, Galician, and Valencian literatures, we carried out a three-level comparative comprehensive analysis taking 2018 as a case study. We combined qualitative and quantitative methods and compared (a) the grant design and priorities, (b) the average funds allocated and the languages and publishers funded, and (c) the participation of the funding bodies at the FBM.

This enables us to conclude that, in terms of gaining visibility abroad, only the Catalan support policies are successful, whereas the Basque, Galician and Valencian ones are mostly focused on internal dissemination and networks, failing at reaching wider international target audiences. This is illustrated at different levels. First, in several sections of the grant design articulated along the areas of accessibility and focus on internationalisation. In terms of accessibility, aspects such as the arrangements put in place for publishers to submit their applications online, the availability of a summary of the call in English and the provision of the option to apply in English guarantee that foreign presses are able to find, understand and participate in the grants. Second, the articulation of a series of general and clear criteria for fund allocation enables publishers to prepare focused grant applications with more chances for success. Regarding their focus on internationalisation, the Catalan case stands out due to the separation of funds for translation from Catalan into other languages, as well as the clear limits to the amount of funds available per publisher, which guarantees a diverse landscape of outlets for these translations. The Basque case follows closely, having implemented many of the same initiatives, but fails in fully accessing the international arena, remaining focused mostly on the Spanish territory. The Galician and Valencian cases, for their part, clearly prioritise translation flows into their own languages. Third, ethnographic research at the FBM revealed that the most effective approach to attract foreign publishers’ attention is for the funding body to act de facto as a proactive literary agent for the whole literary system, as it happens in the case of literature in Catalan, offering detailed and practical information about the grants available, especially if the call is open at the time of the fair. The Etxepare’s attempt to offer support for the internationalisation of Basque literature was limited by their absence from the fair as an institution, decreasing chances of successful deals regarding the sale of translation rights. In the case of the Xunta and Generalitat, publishers holding translation rights were not supported by the administration in any meaningful way and an opportunity to effectively disseminate the translation grants was missed.

All in all, adding this contextual explanation clearly shows that cooperation between funding bodies in the regional governments and the private sector is vital for the internationalisation of stateless literatures in low-diffusion languages, that is, for a successful cultural diplomacy via translation. For this reason, a multifactorial approach to the funding of translation must be implemented, starting with well-designed and accessible calls for grants, coupled with direct involvement from the institutions at book fairs as well as with governmental support to their local private sectors. Only in this way will they facilitate publishers’ meaningful participation in business encounters, enabling the sale of their translation rights internationally.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the personnel at the different institutions and publishing associations for their support and their availability to answer questions during the research process. All subjects provided informed consent in line with the ethics approval obtained for conducting research as part of the ‘Stateless Cultures in Translation: The Case of 21st Century Basque, Catalan and Galician Literatures in the UK’ project. Special thanks to Elisabete Manterola Agirrezabalaga, in her role as advisor on Basque literature for this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Olga Castro

Olga Castro is Associate Professor in Translation Studies at the University of Warwick, Great Britain, where she is Deputy Director of Graduate Studies and convenes the MA Translation and Cultures. Her research focuses on the social and political role of translation in the construction of gender and national identities in the Hispanic world, with a particular focus on transnational feminism, multilingualism, self-translation and stateless cultures in Spain. Recent publications include the co-edited books Translating Women in the Anglosphere: Activism in Action (ITI, 2020), Feminist Translation Studies (Routledge, 2017) and Self-Translation and Power (Palgrave, 2017). She is Principal Investigator of the project “Stateless Cultures in Translation: the case of 21st century Basque, Catalan and Galician literatures in the UK” funded by the British Academy. She is Vice-President of the Association of Programmes in Translation and Interpreting of the Great Britain and Ireland (APTIS) and corresponding member of the Royal Galician Academy.

Laura Linares

Laura Linares is a translator and researcher. She completed her PhD in Translation Studies at University College Cork, Ireland, in 2021, focusing on the translation of Galician narrative into English. Her main research interests include translation and ideology, cultural representation, translation in non-hegemonic cultures and the role of translation in the construction of identities in a global world, as well as the application of corpus-based methodologies to the study of texts and their translations. Laura has recently co-edited, with Olga Castro, a special issue on “Crossing Borders in Translation and Interpreting Studies” for Galicia 21. Journal of Contemporary Galician Studies, issue I (2019). She worked as research assistant for the project “Stateless Cultures in Translation: the case of 21st century Basque, Catalan and Galician literatures in the UK” funded by the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust.

Notes

1 Other categories should be devised to include non-official stateless languages, e.g. Amazige, Asturian or Aragonese in Spain (Brohy et al., Citation2019, p. 24), which are not considered in this article due to the lack of opportunities that their non-official status brings to institutional branding. It is precisely for this reason that some regional governments like the Principality of Asturias have been actively demanding co-official status for their language.

2 There are ongoing heated debates about whether Basque, Catalan/Valencian and Galician literatures are limited to texts written in the co-official languages or whether they may include literature in Spanish (or other languages) by authors identified with those territories. Although consensus is far from being achieved (see Liñeira, Citation2015; Woolard, Citation2016a), whenever the expression Catalan/Valencian, Basque and Galician literature is used in this article, we refer to literature in those languages.

3 Besides these regional initiatives, in May 2021 the Spanish Ministry of Culture published a call for grants to promote the translation of literature among all four co-official languages within the Spanish nation-state for the first time. This new approach could have a future impact on the language pairs subsidised by the regional government funds.

4 Careful scrutiny of the award decisions reveals that in the vast majority of cases these grants are requested to translate from Spanish. In the year 2018, for example, a total of 114 publishers applied for these grants, with only one publisher applying to translate from Galician and another one from Catalan. A total of 84 publishers received funding, these two included.

5 This study focuses on translation grants and funding allocated in 2018, and not on books published in that year that might have received funding from previous calls.

6 See Marin-Lacarta and Yu (Citation2021), which also offers an overview of ethnographic translation studies.

7 The participant observation was conducted by Olga Castro, followed by interviews in person between October 2018 and July 2019 with representatives from the following institutions: Institute Ramon Llull (Frankfurt, 12-10-2018); Xunta de Galicia (Frankfurt, 12-10-2018); Guild of Basque Publishers (Frankfurt, 13-10-2018); Galician Publishers Association (Frankfurt, 13-10-2018); Valencian Book Trust ‘Fundació FULL’ (Frankfurt, 13-10-2018); Xunta de Galicia (Santiago de Compostela, 20-12-2018); Association of Publishers in Catalan Language (Barcelona, 29-11-2018); Basque Etxepare Institute (Donostia/San Sebastian, 21-06-2019); Association of Publishers in Basque Language (Donostia/San Sebastian, 24-06-2019); Valencian Publishers Association (Benicarló, 11-09-2019). All translations into English of direct quotes are our own. These quotes have not been attributed to specific subjects to ensure interviewees are not traceable, in line with ethical standards.

8 While publishers in the Basque, Galician and Valencian languages are often small independent presses with low resources and in some cases operating for a small profit, the book industry in Catalan is much stronger, with publishers in this language being part of larger corporations, many of which are based in Barcelona (see Hooft Comajuncosas, Citation2004). Indeed, the fact that a considerable part of the Spanish-language publishing houses is located in Barcelona likely affects the policies and strategies of the Catalan-language publishing industry.

References

- Primary sources

- BOPV. (2018a). Resolución de 10 de octubre de 2018, de la directora del Instituto Vasco Etxepare. Boletín Oficial del País Vasco. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://www.euskadi.eus/t65aLocatorWar/locatorJSP/t65aSubmitLocator.do;jsessionid=uXXLpdSmW8UGfSeIKuqXqmQ5iVByZ0uIZ5nFOKNZvZIVq45J-IYm!2108788430!-1390990025

- BOPV. (2018b). Resolución de 20 de marzo de 2018 de la directora del Instituto Vasco Etxepare. Boletín Oficial del País Vasco, 4-05-2018, 85. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://www.euskadi.eus/gobierno-vasco/-/eli/es-pv/res/2018/03/20/(7)/dof/spa/html/

- DOG. (2017). Orde do 22 de novembro de 2017. Diario Oficial de Galicia, 241, 21-12-2017. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://www.xunta.gal/dog/Publicados/2017/20171221/AnuncioG0164-301117-0005_gl.html

- DOG. (2018a). Corrección de erros. Resolución do 21 de xuño de 2018 pola que se dá publicidade ás axudas concedidas ao abeiro da Orde do 22 de novembro de 2017. Diario Oficial de Galicia, 137, 18-07-2018. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://www.xunta.gal/dog/Publicados/2018/20180718/AnuncioG0164-130718-0001_gl.html

- DOG. (2018b). Resolución do 21 de xuño de 2018. Diario Oficial de Galicia, 131, 10-07-2018. Retrieved November 15, 2020 from https://www.xunta.gal/diario-oficial-galicia/mostrarContenido.do?paginaCompleta=false&idEstado=5&rutaRelativa=true&ruta=/2018/20180710/Secciones2_gl.html

- DOGC. (2018a). Resolución del director del Institut Ramon Llull por la que se abre la convocatoria para la concesión de subvenciones. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 7667, 19-07- 2018. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://dogc.gencat.cat/es/pdogc_canals_interns/pdogc_sumari_del_dogc/?numDOGC=7667&anexos=1#

- DOGC. (2018b). Resolución por la que se modifica la dotación presupuestaria. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 7769, 17-12-2018. Retrieved September15, 2020 from https://dogc.gencat.cat/es/pdogc_canals_interns/pdogc_sumari_del_dogc/?numDOGC=7769&anexos=1#

- DOGV. (2018a). Resolución de 15 de marzo de 2018, de la Conselleria de Educación, Investigación, Cultura y Deporte. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana, 8264, 29-03-2018. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from http://www.dogv.gva.es/portal/ficha_disposicion_pc.jsp?sig=003208/2018&L=1

- DOGV. (2018b). Resolución de 20 de julio de 2018, de la Conselleria de Educación, Investigación, Cultura y Deporte. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana, 8354, 3-03-2018. Retrieved November 15, 2020 from http://www.dogv.gva.es/portal/ficha_disposicion.jsp?L=1&sig=007556%2F2018&url_lista=

- Institut Ramon Llull. (2018). Resolución de la convocatoria para la concesión de subvenciones. Institut Ramon Llull. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://oficinavirtual.llull.cat/ov/sites/default/files/tauler_anuncis/11N-RESOL_TRD_CONV_2018_CAST.pdf

- Secondary sources

- Alvstad, C. (2017). Arguing for indirect translation in twenty-first century Scandinavia. Translation Studies, 10(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2017.1286254

- Anholt, S. (2003). Brand new justice. Elsevier.

- Assis Rosa, A., Pięta, H., & Bueno Maia, R. (2019). Indirect translation: Theoretical, methodological and terminological issues. Routledge.

- Bacardí, M. (2019). Translation policies from/into the official languages in Spain. In R. A. Valdeón, & Á. Vidal (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish translation (pp. 429–453). Routledge.

- Bermúdez, S., Cortijo, A., & Mc-Govern, T. (2002). From stateless nations to postnational Spain. Boulder Society of Spanish-American Studies.

- Branchadell, A., & West, L. M. (2005). Less translated languages. Amsterdam.

- Brohy, C., Climent-Ferrando, V., Oszmiańska-Pagett, A., & Ramallo, F. (2019). European charter for regional or minority languages: Classroom Activities. Council of Europe. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from http://www.mptfp.es/dam/es/portal/politica-territorial/autonomica/Lenguas-cooficiales/Consejo-Europa-Carta-lenguas/Guia-didactica/ECRML-Educational-Toolkit-English.pdf0#page=1

- Canagarajah, S. (2006). Ethnographic methods in language policy. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An Introduction to language policy: Theory and method (pp. 153–169). Blackwell.

- Casanova, P. (2007). The world republic of letters. (Malcolm DeBevoise, Trans.). Harvard UP.

- Castro, O. (2021). Rutas diversas para un mismo fin? El apoyo institucional a la traducción de las literaturas en catalán, gallego, valenciano y vasco en la Feria del libro de Fráncfort. In C. Villarino, A. Luna, & I. Galanes (Eds.), Promoción literaria, cultural y traducción en la actualidad. Ferias internacionales del libro e invitados de honor (pp. 225–241). Peter Lang.

- Castro, O., & Linares, L. (2019a). Conclusións e propostas de acción das xornadas A internacionalización da literatura galega en tradución ao inglés. Consello da Cultura Galega and British Academy. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from http://consellodacultura.gal/mediateca/extras/CCG_pr_2019_Conclusions-e-Propostas-de-Accion-para-Traducion-Literatura-Galega-ao-Ingles.pdf

- Castro, O., & Linares, L. (2019b, June 17–19). The internationalization of Galician literature in English translation. Public event and training workshops. Consello da Cultura Galega, Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from http://consellodacultura.gal/evento.php?id=200826

- Chitnis, R., Stougaard-Nielsen, J., Atkin, R., & Milutinovic, Z. (Eds.). (2019). Translating the Literatures of Small European nations. Liverpool UP.

- Díaz Fouces, Ó. (2005). Translation policy for minority languages in the European Union. Globalisation and resistance. In A. Branchadell, & L. M. West (Eds.), Less translated languages (pp. 95–104). Amsterdam.

- Etxepare Euskal Institutua. (2018). Urteko txostena/Memoria anual 2018. Etxepare.

- Flotow, L. v. (2018). Translation and cultural diplomacy. In J. Evans, & F. Fernández (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and politics (pp. 193–203). Routledge.

- Geli, C. (2018, July 15). Cataluña y Valencia, vecinas en la Feria del Libro de Fráncfort. El País. Retrieved November 10, 2020 from https://elpais.com/ccaa/2018/10/11/catalunya/1539273970_919652.html

- Gienow-Hecht, J. C. E., & Donfried, M. C. (Eds.). (2010). Searching for a cultural diplomacy. Berghahn.

- Goff, P. (2013). Cultural diplomacy. In A. Cooper, J. Heine, & R. Thakur (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of modern diplomacy (pp. 419–435). OUP.

- Hooft Comajuncosas, A. v. (2004). Un espacio literario intercultural en España? El polisistema interliterario en el Estado español a partir de las traducciones de las obras pertenecientes a los sistemas literaios vasco, gallego, catalán y español. In A. Abuín González, & A. Tarrío Varela (Eds.), Bases metodolóxicas para unha historia comparada das literaturas da península Ibérica (pp. 313–333). USC.

- Institut Ramon Llull. (2018). Memòria 2018. Ramon Llull.

- Johnson, D. C. (2009). Ethnography of language policy. Language Policy, 8(2), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-009-9136-9

- Keating, M. (1997). Stateless nation-building: Quebec, Catalonia and scotland in the changing state system. Nations and Nationalism, 3(4), 689–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1997.00689.x

- Liñeira, M. (2015). Something in between: Galician literary studies beyond the linguistic criterion. Abriu, 4, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1344/abriu2015.4.5

- Lynch, A. (2011). Spain’s minoritized languages in brief sociolinguistic perspective. Romance Notes, 51(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/rmc.2011.0006

- Mansell, R. (2019). Strategies for success? Evaluating the rise of Catalan literature. In R. Chitnis, J. Stougaard-Nielsen, R. Atkin, & Z. Milutinovic (Eds.), Translating the Literatures of Small European nations (pp. 126–144). Liverpool UP.

- Manterola Agirregazalaga, E. (2011). La traducción de literatura vasca a otras lenguas. mTm, 3, 58–79. http://hdl.handle.net/10810/46463

- Marin-Lacarta, M., & Yu, C. (2021). Call for Papers: Ehnographic research in translation and interpreting studies. The Translator (2023). Retrieved February 10, 2020 from https://think.taylorandfrancis.com/special_issues/ethnographic-research-translation-interpreting-studies/

- McMartin, J. (2019). A small, stateless nation in the world market for book translations: The politics and policies of the Flemish literature fund. TTR, 32(1), 145–175. https://doi.org/10.7202/1068017ar

- McMartin, J. (2021). This is what we share: Co-branding Dutch literature at the 2016 Frankfurt Book fair. In H. van den Braber, J. Dera, J. Joosten, & M. Steenmeijer (Eds.), Branding books across the ages: Strategies and key concepts in literary branding (pp. 273–292). Amsterdam UP.

- Montero Küpper, S. (2017). Sobre as subvencións públicas á tradución editorial galega (2008-2016). Madrygal. Revista de Estudios Gallegos, 20, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.5209/MADR.57632

- Oficina para las lenguas oficiales. (2019). Informe de diagnóstico sobre el grado de cumplimiento del uso de las lenguas cooficiales en la administración general del Estado. Ministerio de Política Territorial y Función Pública. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from http://www.mptfp.es/dam/es/portal/politica-territorial/autonomica/Lenguas-cooficiales/Consejo-de-Lenguas-Cooficiales/Informes/INFORME-DIAGNOSTICO-LENGUAS-2019.pdf

- Ortuño, A. (2017, January 24). Los nuevos títulos de valenciano acaban con el bloqueo en Cataluña. Valencia Plaza. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from https://valenciaplaza.com/los-nuevos-titulos-de-valenciano-acaban-con-el-bloqueo-en-cataluna

- Ronen, S., Gonçalves, B., Hu, K. Z., Vespignani, A., Pinker, S., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2014). Links that speak: The global language network and its association with global fame. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(52), E5616–E5622. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1410931111

- Schiffman, H. F. (2017). Diglossia as a sociolinguistic situation. In F. Coulmas (Ed.), The handbook of sociolinguistics (pp. 205–216). Blackwell.

- Villarino Pardo, C. (2014). As feiras internacionais do livro como espaço de diplomâcia cultural. Brasil/Brazil. A Journal of Brazilian Literature, 50, 134–154. http://hdl.handle.net/10347/13432

- Villarino Pardo, C. (2016). Estrategias y procesos de internacionalización. Vender(se) y mostrar(se) en ferias internacionales de libro. In I. Galanes Santos, A. Luna Alonso, S. Montero Küpper, & Á. Fernández Rodríguez (Eds.), La traducción literaria. Nuevas investigaciones (pp. 73–92). Comares.

- Woolard, K. A. (2016a). Singular and plural: Ideologies of linguistic authority in 21st century Catalonia. OUP.

- Woolard, K. A. (2016b). Branding like a state: Establishing Catalan singularity at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Signs and Society, 4(1), 20–50. https://doi.org/10.1086/684492

- Xunta de Galicia. (2018). Memoria de actividades de cultura 2018.