ABSTRACT

Achieving a detailed understanding of source documents is an essential step in the translation process. Furthermore, in modern settings of translation projects in which various actors, such as clients, project managers, and translators, are involved, it is crucial to share such understanding through a properly formulated terminology. While the previous literature on translation studies, particularly in relation to functionalist approaches, has provided various frameworks and methods for source text analysis and profiling, the terminology for such processes has not been sufficiently established. This article, therefore, examines the previous literature to widely collect terms regarding source document properties and organise them as a terminology from the documentational point of view. The formulated terminology covers four major categories, i.e. knowledge, communication, formation, and text properties, consisting of a total of 57 terms. The constructed terminology not only theoretically systematises the knowledge accumulated in previous studies but also would provide a scaffold for better process and communication in translation practices and training.

1. Introduction

In many practical settings of translation projects, various actors are involved in the translation process, such as clients, translation service providers (TSPs), project managers, translators, revisers, and reviewers (ISO, Citation2015). To facilitate smooth communication between them, it is crucial to use consistent terminologies in each step of the translation workflow, including source document (SD)Footnote1 understanding, translation, revision, and review. Among others, terminologies for the revision and review processes have been established. Several translation quality assessment frameworks offer systematic lists of terms for identifying translation issue types and have been widely adopted by TSPs to ensure the quality of translations. For example, MQM (Multidimensional Quality Metrics) (Burchardt & Lommel, Citation2014; Lommel et al., Citation2014) hierarchically lists more than 100 issue types derived from an examination of existing quality assessment frameworks.

In contrast, terminologies for the SD understanding process have not necessarily been utilised in translation practices, while many efforts hitherto have been made to present terminologies (e.g. ISO, Citation2012; Nord, Citation2005). One of the reasons for this is that, although each terminology is useful individually, taken together, terminologies may not be consistent; their scope, perspectives and entries are different from each other. A consensus about the process and terms among translation scholars and practitioners has yet to be established. To enhance the translation process and encourage communication among the actors involved in it, a well-managed terminology is crucially needed.

The SD understanding process can be further grouped into two processes: (1) the process of understanding the status and properties of a document as a whole, and (2) the process of understanding the specific textual elements within the document, or translation units, which will be transferred into a target language. With a specific focus on the former process, which can be called source document (SD) profiling, this article aims to provide a systematic typology of document properties as a terminology by reviewing literature on translation theories and practices. While the target literature was mainly selected from the influential work of functional theories, in which communicative situations and purposes are given great importance, terms and concepts regarding such text-external factors were interpreted as the properties of documents, which is the most substantial theoretical standpoint of this review.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 examines the notion and role of documents in translation and provides the formal definition of the SD profiling process in comparison with the related processes of translation. Section 3 explains the scope and procedures of the literature review used to collect and organise the existing terms. In Section 4, the resulting systematic typology of document properties is presented as the terminology for SD profiling. Finally, Section 5 concludes the article with implications for future work.

2. What is source document profiling?

The core process of translation includes achieving a proper understanding of the object to be translated in the initial step. As Nord (Citation2005, p. 1) emphasised, translation-oriented source text analysis not only facilitates thorough comprehension of a text but also provides a foundation for each decision made by the translator in the translation process. The widely-acknowledged standard for translation services, ISO 17100, explicitly defines the ‘source language content analysis’ as a preparatory step taken before embarking on the productive process of translation, stating that TSPs ‘shall ensure that the source language content is analyzed to ensure efficient and effective performance of the translation project’ (ISO, Citation2015, p. 9). From the viewpoint of translation competence, PACTE (Citation2000, p. 102) lists ‘comprehension competence (the ability to analyse, synthesise and activate extra-linguistic knowledge so as to capture the sense of a text)’ as one of the sub-components of ‘transfer competence’, which is the central competence necessary for translation. The translation competence defined in EMT (Citation2017, p. 8) also includes the following: ‘Analyse a source document, identify potential textual and cognitive difficulties and assess the strategies and resources needed for appropriate reformulation in line with communicative needs’.

While the studies and frameworks above refer to a similar range of translation processes, i.e. processes taking place before the interlingual transfer process, several terminological variations are observed in terms of the object to be translated, such as ‘source text’, ‘source language content’, and ‘source document’, and of the action, such as ‘analysis’ and ‘comprehension’. Hence, the following subsections include an examination of these terms and an attempt to formalise their usage and scope.

2.1. The notion of documents in translation

In the field of translation studies, the term ‘source text’ (ST) is usually adopted to refer to the object to be translated, which is ‘not simply a linguistic entity, as it enters into networks of relationships of not only a linguistic, but also a textual and cultural nature’ (Shuttleworth & Cowie, Citation1997, p. 158). For example, to lay the foundations for translation-oriented source text analysis, Nord (Citation2005, pp. 13–17) critically examined the ‘text-centred’ notions of textuality and provided a perspective for considering both the structural and pragmatic aspects of text along with their interdependence. However, in a general sense, the notion of ‘text’ is chiefly regarded as comprising linguistic elements, and, particularly, research communities in linguistics and natural language processing have tended to focus on the linguistic or structural aspects of a text. This may sometimes become a source of miscommunication between translation studies and related areas in both research and practice. In this context, this article adopts this rather general view of texts and, instead, examines the notion of documents in contrast to that of texts.

Referring to communication theory, Sager (Citation1997, p. 27) pointed out that ‘[i]t is the writer’s intention encoded in the document which distinguishes a document from a ‘text’, i.e. a unit of form and content only’, noting that translators ‘mainly deal with documents’. The point is, again, that while a text is viewed as a neutral linguistic or informational unit, a document can be positioned in a situation of communication involving actors, such as writers and readers.

This view is useful as a point of departure, but it does not suffice to define documents. For example, consider the sentence ‘Please send me the book by Wednesday’ as a text that expresses a writer’s intention, such as requesting a reader to do something. Is this sentence a document? Is it possible to translate this sentence adequately? The answer may be no; translators may not be able to concretely decide how to translate this isolated text even if they know (only) the intention of the writer. They may also need to know other kinds of information regarding the text, such as the intended reader of the sentence and the medium used to convey the message. In other words, the intention is only a single aspect of the document although it is an important factor to be considered in translation. More importantly, the notion of a document precedes a text and its properties; the intention encoded in the text is identifiable only after the document is objectified. Here, we can observe the inherent status of a document that is conceptually different from the text.

The notion of documents has been extensively discussed in the field of library and information science (e.g. Buckland, Citation1997, Citation2018; Lund, Citation2010). Among the physical, social, and cognitive aspects of documents mentioned by Buckland (Citation2018), the social aspect can be of great importance in translation, subsuming the communication situation regarding the documents. Thus, this view is naturally related to the ‘functionalist’ approach (e.g. Nord, Citation2018) in that the communication situation surrounding an ST is considered in the process of translation. Nevertheless, we should note that the functionalist approach tends to regard an ST as one of the variables in the overall situation under the purpose, or ‘Skopos’, of translation. This is different from the view that each document is unique and irreplaceable in society. In this view, as described above, we first objectify the document as a base unit and then identify its surrounding information as its properties. This can be called the ‘documentational’ approach.

Given the unique status of each document in society, a text included in the document is not a random collection of text pieces. These pieces are interrelated to each other to form a whole text. This view is related to the genre perspective which focuses on ‘the conventional structures used to construct a complete text within the variety, for example, the conventional way in which a letter begins and ends’ (Biber & Conrad, Citation2009, p. 2). The notion of completeness is, therefore, important. From the genre perspective, we view any textual segment not in isolation, but in relation to the complete text, or the document, of which it forms a part.

In summary, a document cannot be compositionally defined using a text and its properties.Rather, it can be defined as a unique object that bears functions in society and mainly consists of a complete text. Only after the acknowledgement of the document itself can the certain properties of and textual elements within the document be examined. It should be noted here that in contemporary technologised environments of commercial translation in which translation memories (TMs) are employed, the original units of documents are fragmented and translators are presented with ‘a set of sequentially numbered segments’ (Olohan, Citation2020, p. 52). Although facilitating or constraining translators to reuse previously translated segments can increase their productivity and improve the consistency of translations, the problem of the decontextualisation of texts induced by TM-based translation environments has long been recognised and has sometimes been referred to as the ‘sentence salad’ phenomenon (Bedard, Citation2000; Bowker, Citation2005) or ‘collage’ translations (Mossop, Citation2006). Schneider et al. (Citation2018, p. 753) also stated that ‘picking one suggested translation “out of context” is a very risky procedure since the topic of the original document might be completely different and thus unsuitable’. While translators process texts in a variety of linguistic forms using various technologies, their decision-making processes during translation are premised on the proper recognition of the documents.

2.2. Definition of source document profiling

Based on the examination of the notion of documents above, we can broadly identify two aspects of (source) documents: properties and elements. The document properties widely cover the external attributes of a document or any document-wide characteristics of a complete text. For example, the document properties include the ‘author’ and ‘created period’ as well as the ‘degree of formality’ of language use generally observed in the document. On the other hand, document elements are document-internal segments that can mostly be identified in textual or linguistic forms, such as words, phrases, and sentences. A relevant concept is the translation unit, which is defined as ‘the entity which is taken to be processed by the translator at a given time during the process of translation’ (Palumbo, Citation2009, p. 140). Bassnett (Citation2013, pp. 126–127) stressed that the entire text, which corresponds to the document in this article, is the ‘prime unit’ and that smaller translatable units within the text should be related to the whole. In this regard, while this term, the translation unit, encompasses the document itself (including its properties) as well as the document elements, the conception of the document as a distinct, primal unit is important in translation.

Moreover, the dichotomy between the properties of the whole document and its internal elements is practically beneficial as the identification process of the document properties may be separately conducted in advance of that of document elements. In commercial translation projects, the process of identifying document properties is conducted in the project preparation stage. ISO (Citation2012, p. 12) prescribes that the preliminary project specifications should cover ‘source content information, including source language, text type, audience and purpose, subject field, volume, known complexity and challenges, and origin’, most of which can be regarded as document properties. This information is provided to the translators in the subsequent production stage. The process of identifying document elements is more closely tied to the productive process of translation. Gile (Citation2009, p. 89), for example, stated that ‘[t]ranslation can be modelled as a recurrent two phase process operating on successive Text segments: the first phase is comprehension, and the second is reformulation in the target language’.

This article is focused on the former process, that is, the identification of SD properties, which can be called ‘source document (SD) profiling’. A document property can be formalised as a {name: value(s)} pair, such as {language: Japanese}, {genre: business letter}, and {purpose: to inform stakeholders of the release of a new product}. Here, the ‘names’ of the document properties correspond to the ‘terms’, and they are interchangeably used in this article. A well-organised set of SD properties constitutes an SD profile.Footnote2 Hence, the SD profiling process can be restated as the process of specifying the values of the document properties listed in the SD profile.

The specified SD profile provides the basis for the subsequent core process of translation. These SD properties are not necessarily preserved in the target document (TD). Instead, the SD properties should be, when necessary, appropriately converted to TD properties based on the translation brief or purpose, which will directly govern translators’ decision making. While the detailed formalisation of this conversion process is beyond the scope of this article, we should be aware that the role and necessity of SD profiling in the overall process of translation (see Nord, Citation2005, pp. 5–39 for detailed discussions).

3. Methodology: a literature review

3.1. Target literature

The aim of this article is to provide a formalised terminology for SD profiling, that is, an organised list of terms that refer to document properties. Although several terminologies used for ST analysis or source content analysis (e.g. ISO, Citation2012; Nord, Citation2005) can be referenced as a starting point, their perspectives and coverage diverge, and some terminological inconsistencies are observed. What is first needed is to establish a broad, consistent understanding of the existing terminologies. Therefore, taking the literature review approach, this article investigates the existing terminologies to collect the terms that are used to indicate document properties and conceptually organise them to form a comprehensive terminology.

shows eight books or documents on translation studies and practices selected as the target of this review,Footnote3 all of which include terms regarding document properties. The target literature was mostly selected from authoritative books on functional theories of translation, that is, Nord (Citation2005), Reiss (Citation1971/2000), Reiss and Vermeer (Citation1991/Citation2013), and Snell-Hornby (Citation1995).Footnote4 As mentioned in Section 2, the functionalist approach attaches importance to extralinguistic communicative situations, that naturally overlap with the scope of document properties. To further expand the coverage of terminology, different perspectives were also incorporated. The work on translation evaluation models by House ([Citation1977] Citation2014; [Citation1997] Citation2014), which can be broadly categorised as a ‘discourse and register approach’ (Munday, Citation2016, pp. 141–168), includes source text analysis processes in the models. The textbook by Newmark (Citation1988) has been widely used in translation training and offers practical methods and frameworks for translation, including the analysis of source text. While these textbooks are chiefly used for theoretical readings in universities or professional translator training, ISO (Citation2012) principally caters to the practical needs of the translation industry. As such, the target literature covers various perspectives on SD profiling, and a wide range of terms can be obtained from the review.

Table 1. Target literature for the review.

3.2. Procedure for terminology construction

The targeted literature is used as a source of terms for document properties. The review proceeds in two phases:

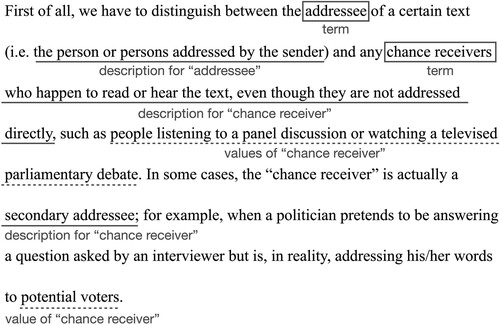

Term extraction phase: From each source, extract (1) noun phrases that refer to document properties as terms (i.e. property names), (2) presented examples or options for the properties as values, and (3) the definitions or explanations to be used as descriptions.

Term organisation phase: Examine the extracted terms, referring to, if any, their values and descriptions, and hierarchically synthesise them into a unified typology.

Figure 1. Example of extraction of terms with their descriptions and values from the source literature; the paragraph is excerpted from Nord (Citation2005, p. 58) and the annotations are inserted by the author of this article.

In the term organisation phase, the collected terms are aggregated to form a comprehensive terminology. In this process, the terms are adjusted in scope and, if necessary, renamed to resolve any inconsistencies in related terms and maintain the systematicity of the terminology.

4. Terminology of source document properties

Through the review process in Section 3, a total of 90 terms regarding document properties were extracted from the literature and examined in a bottom-up manner. shows the overview of the resultant terminology consisting of 57 formalised terms that are hierarchically organised. The correspondence between the formulated terms and collected original terms is provided in Appendix.

Table 2. Formulated terminology of source document properties.

One novelty of this terminology is the systematic categorisation of terms. Nord (Citation2005) provided a well-organised framework in which factors for ST analysis are broadly divided into extratextual and intratextual categories. The former includes, sender, sender’s intention, audience, medium, place of communication, time of communication, motive for communication, and text function, while the latter includes subject matter, content, presupposition, text composition, non-verbal elements, lexis, sentence structure, and suprasegmental features. This dichotomy – extratextual vs. intratextual – is generally applicable but seems too coarse-grained to systematically accommodate the wide variety of document properties identified in the review. More importantly, the focus of this study is the unit of document, and even communicative situations are regarded as properties of the document.

Therefore, the top-level categories of the formulated terminology were defined based on the general aspects of documents, namely knowledge, communication, formation, and text. The knowledge properties indicate the status of a document in relation to the knowledge or other documents accumulated in society. The communication properties capture the role and function of a document in the overall communicative situation surrounding it; these properties have been extensively mentioned in the literature on functionalist approaches, such as by Nord (Citation2005) and Reiss and Vermeer (Citation1991/Citation2013). The formation properties are related to how the content to be conveyed is packaged and encoded as a visible document – whether physical or digital – with a specific structure. The text properties, in contrast, pertain to how the content to be conveyed is linguistically materialised. Although the text properties are applicable to various textual spans within a document, the focus of this study is the whole text, that is, the document-wide characteristics of text.

In the following subsections, details of each term in these four categories will be explained.

4.1. Knowledge properties

(K01) subject field and (K02) topic pertain to the following question: What is this document about? The subject field refers to the general categories of subjects, such as chemical engineering and personal finance, while the topic can be defined to indicate more specific content, such as ‘a story about a bear family’ (House, [Citation1997] 2014, p. 75). Although the previous literature does not seem to explicitly distinguish between such differences in granularity, e.g. ‘topic’ (House, [Citation1977] 2014, p. 30; Newmark, Citation1988, p. 40) and ‘subject matter’ (House, [Citation1997] 2014, p. 65; Nord, Citation2005, p. 93; Reiss, Citation1971/Citation2000, p. 70), it would be useful to conceptually separate these terms to understand an SD in detail.

The notion of the (K3) genre and its equivalents has been well discussed in the literature on translation studies. House, [Citation1997]Citation2014, p. 64), for example, affirms the importance of the category of genre for translation quality assessment, noting that ‘it enables one to refer any single textual exemplar to the class of texts with which it shares a common purpose or function’. Nevertheless, the definition of genre has not been fully established or shared in the target literature, even in linguistics (e.g. Biber & Conrad, Citation2009, pp. 21–23). Since a rigorous inspection of the definition of genre is beyond the scope of this article, the following concise definition which is acknowledged in translation studies is adopted: ‘conventional forms of texts associated with particular types of social occasion’ (Hatim & Mason, Citation1997, p. 218). A wide variety of genres with different levels of granularity have been presented in various types of literature from utility patents and appliance user manuals (ISO, Citation2012, p. 19) to recipes and weather reports (Reiss & Vermeer, Citation1991/Citation2013, p. 167). These text classes may also be called ‘text types’ not only in everyday language, but also in the target literature, such as ISO (Citation2012, p. 19) and the work of Newmark (Citation1988, p. 40). However, the term ‘text type’ is specifically used as a function-oriented notion of text classes in translation studies (e.g. expressive text type). To avoid confusion between theory and practice, the term ‘genre’, which is also familiar to those who are not researchers, has been adopted.

(K04) difficulty is an ordinal concept, ranging from easy to difficult. Newmark (Citation1988, p. 14) provides convenient categories of difficulty: simple, popular, neutral (using basic vocabulary only), educated, technical, and opaquely technical (comprehensible only to an expert). It should be noted that this property focuses on the difficulty of the content conveyed by an SD. While the difficulty of content is generally correlated with that of form, i.e. lexis and structure, it is important to distinguish between the two as difficult content may sometimes be conveyed in plain language.

(K05) background knowledge is the knowledge that is supposed to be or should be known by readers to properly understand an SD. Snell-Hornby (Citation1995, p. 33) mentioned the ‘non-linguistic disciplines’ underlying translation, stating, for example, ‘literary translation presupposes a background in literary studies and cultural history’. This can be regarded as an SD property and renamed as (a) academic discipline. Other types of background knowledge have been broadly categorised as (b) presupposition, examples of which are ‘the knowledge on the part of the receiver that this [Twelfth Night or What You Will] is the title of a play’ (Nord, Citation2005, p. 105) and ‘the reference to Goethe’s play Faust, Part I, line 421’ (Reiss & Vermeer, Citation1991/Citation2013, p. 138).

Finally, (K06) resource is different from the other knowledge properties as it refers to concrete, visible entities, such as documents and linguistic expressions, rather than abstract types of knowledge, such as topic and difficulty, as mentioned above. While many kinds of resources can be included in this property, the following two terms were specifically identified: the (a) origin of an SD and the (b) terminology relevant to the source content (ISO, Citation2012, p. 20).

4.2. Communication properties

The first three properties, C01–C03, are related to the sending–receiving situation. (C01) sending and (C02) receiving symmetrically cover (a) sender/receiver (‘who’), (b) sending/receiving time (‘when’), and (c) sending/receiving place (‘where’). Some of the inconsistencies among similar terms such as ‘receiver’, ‘addressee’, ‘audience’, ‘readership’, and ‘recipient’ have been adjusted to keep the typology systematic. It is important to note that the values of these properties greatly vary; for example, ‘adult’, ‘Spanish’, and ‘his wife’ (Nord, Citation2005, pp. 59–60) are all instances of (C02-a-i) addressee. We can observe here that the focus and granularity of the descriptions differ from each other. How to effectively specify these values with the subsequent translation process in mind is yet to be established.

The (C04) communication field refers to the domain in which an SD is communicated and captures the broader communication situation. Examples include ‘scholarly, philosophical, religious, aesthetic or everyday communication’ (Reiss & Vermeer, Citation1991/Citation2013, p. 139). In this regard, it is different from the actor-oriented (C03) sender–receiver relationship.

The (C05) function indicates the communicative effects that are implied in an SD, which are of central importance in the functionalist approach. The notion of function is also closely associated with the ‘text type’, the categories of which correspond to those of functions, such as expressive, informative, and operative. These categories are based on the functional view of language (e.g. Buhler, Citation1934; Jakobson, Citation1959/Citation2013). As mentioned earlier, the term ‘text type’ might be a source of confusion outside translation studies; thus, the term ‘function’ is adopted. Although the range of functions differs depending on the literature, in general, three to six basic categories have been listed, examples of which are as follows:

expressive, informative, vocative, aesthetic, phatic, metalingual (Newmark, Citation1988, pp. 39–44);

referential (denotative, cognitive), expressive (emotive), operative (appellative, conative, persuasive, vocative), phatic (Nord, Citation2005, p. 47);

representation, expression, pursuation (Reiss, Citation1971/Citation2000, p. 26);

informative, expressive, operative, multimedia (Reiss & Vermeer, Citation1991/Citation2013, p. 137).

Like the notion of function, the (C06) purpose is the communicative goal of an SD. A purpose can be abstracted as a function; for example, ‘to give a list of the necessary ingredients’ for cooking (Nord, Citation2005, p. 56) corresponds to an ‘informative’ function. The sender’s intention (Newmark, Citation1988, p. 12; Nord, Citation2005, p. 53) is interpreted as the purpose of an SD. This is important as the present study takes the document-oriented view of translation, avoiding subjective concepts such as intention.

The (C07) background situation explains how and through what process an SD is produced and communicated, broadly covering its chronological and causal background, such as ‘because something of importance has happened’ and ‘because it is Grandfather’s 70th birthday’ (Nord, Citation2005, p. 75). This property was rendered from the term ‘motive of communication’ (Nord, Citation2005, p. 74) to avoid the subjective connotation of the term ‘motive’.

4.3. Formation properties

The most basic forms of a document are the (F01) communication medium, such as newspaper, magazine, book, multi-volume encyclopedia, leaflet, and brochure (Nord, Citation2005, p. 64), and (F02) symbol type, such as text, images, audio, and video recordings (ISO, Citation2012, p. 20). Although the direct object to be translated is the linguistic expressions or text, these properties fundamentally govern the way of translation.

The (F03) file covers the properties from the viewpoint of document management, including (a) volume, (b) format, (c) markup, and (d) editability. Importantly, these properties are only mentioned in ISO (Citation2012, p. 20), which is mainly intended for prescribing the processes of translation projects in practice. These practical aspects of documents tend to be missed in translation theories.

The formation properties mentioned above can be specified in the form ‘The [property name] is [property value]’. Some examples are as follows:

The (F01) communication medium is a newspaper.

The (F03-c) markup is XML.

In contrast, (F04) structure properties deal with the internal structure of documents, and description of the values can be more complicated. Some examples are as follows:

(F04-a) document structure: the document is composed of a title, two levels of sections at maximum with headings, and endnotes.

(F04-b) content structure: the document is composed of an introduction, an entry into the subject, examples, and a conclusion.

The focus here is not on each element in the values, such as the title or introduction, but on the composition of the elements within the whole document. In relation to this point, it is also notable that each element is interrelated with the other elements and the document itself; for example, a subsection with a heading is hierarchically subsumed under the section.

4.4. Text properties

The (T01) language is the basic property, although it has seldom been explicitly mentioned as a document property in the literature since it is a given from the outset. The exception is ISO (Citation2012, p. 19), which not only mentions languages in the general sense (e.g. Portuguese and English) but also variants or locale (e.g. Brazilian Portuguese and UK English).

The (T02) register refers to ‘a variety associated with a particular situation of use (including particular communication purposes)’ (Biber & Conrad, Citation2009, p. 6). While the basic options of the (a) mode are spoken or written, actual texts may combine them in a complex manner, such as ‘[w]ritten to be read aloud as if not written’ (House, [Citation1997] 2014, p. 78). As for the (b) formality scale, Newmark (Citation1988, p. 14) provides fine-grained options: officialese, official, formal, neutral, informal, colloquial, slang, and taboo. These parameters are decided according to the situational contexts of discourse, and the resulting linguistic variations are functional.

On the other hand, (T03) dialect is not functional but conventional, and linguistic variations are associated with specific groups of language users (Biber & Conrad, Citation2009, p. 11). While many types of dialects have been investigated in sociolinguistics (e.g. Holmes & Wilson, Citation2017; Hudson, Citation1996), in this review, three properties – (a) geolect, (b) chronolect, and (c) sociolect,Footnote5 which respectively reflect the geographical, temporal, and social dimensions of language users – are identified. In this study, dialects are regarded as properties of the text in the document, not its sender. It is possible that an American author in the twenty-first century might write texts using old British English. In this case, the text properties would be identified chiefly based on text written in old British English.

The (T04) style is related to the notion of register, and the definitions and scope of these terms are often vague and inconsistent in the target literature. Indeed, the existing terminology in translation studies points out that style is ‘a highly contentious term, disliked by many scholars and researchers because of its vagueness yet frequently used in descriptions of linguistic and translation phenomena’ (Palumbo, Citation2009, p. 110). According to the style perspective presented by Biber and Conrad (Citation2009, p. 18), linguistic patterns are ‘associated with aesthetic preferences, influenced by the attitudes of the speaker/writer about language’.Footnote6 Here we can extend this view and define styles as manifested varieties of text ascribable to the author’s preferences or characteristics. Importantly, this definition includes diverse types of preferences, such as (a) stance and (b) emotional tone, which are not limited to ‘aesthetic’ ones.

(T05) quality refers to how linguistically good/bad, or easy/complex, the text is. Although the quality of a translation is one of the central topics in translation studies, that of an SD is not widely mentioned in the literature. The exception is ISO (Citation2012, p. 20), which lists several aspects of an SD’s quality as complexity parameters in the translation process, such as (a) cohesion and (b) coherence. The (c) readability property is distinguished from the (K04) difficulty property in Section 4.1, with the former being concerned with the linguistic forms of a text and the latter being concerned with the knowledge that it aims to convey.

The last property, (T06) representation pattern, refers to how communicative acts are materialised in a text, which is beyond linguistic viewpoints. This includes, for example, monologue and dialogue (House, [Citation1977] 2014, p. 29). Although this appears to be included in the communication properties in Section 4.2, the communicative acts in question are solely at the level of the text and are irrelevant to the document-external actors. For example, the dialogue between two characters in a novel can be identified without referring to the author’s communication situation.

5. Conclusions and outlook

In this article, a literature review was conducted to formulate a systematic terminology for SD profiling, an important preparatory process of translation to specify the properties of an SD. A total of 90 terms regarding document properties were first collected from the literature on translation studies and practices, and were then comprehensively examined and organised hierarchically as a terminology. The formulated terminology consists of 57 formalised terms in four major categories: knowledge, communication, formation, and text properties. The theoretical significance of this review is that existing terms were examined from the documentational point of view; even document-external parameters, such as the sender’s intention, were interpreted as properties of documents.

This wide-ranging terminology can be used in the SD profiling process and facilitate accurate communication between the various actors engaged in translation practices, including project managers, translators, and clients. To that end, the terminology should first be validated in actual use scenarios. Although it was formulated with the use by various people in mind, including those outside the field of translation studies, some document properties may not be easily understood by them. In practice, furthermore, it is unrealistic to fully specify all the document properties in the SD profiling process. Hence, the refinement of terminology based on users’ feedback and the development of user guidelines will be an important step towards the effective and efficient implementation of SD profiling in practice.

The proper use of terminologies also plays a crucial role in translation education and training.Footnote7 Terminologies can be used as common languages to share the understanding of translation processes and products between translation trainers and trainees, and can help trainers transfer their expertise to the trainees. In such use scenarios, the formulated terminology of SD properties should be evaluated in terms of learnability (whether the terminology is easily assimilated by learners), accuracy (whether learners can correctly specify the document properties), and effectiveness (whether the use of terminology improves the translation processes and products).

This article is specifically focused on the SD profiling process and does not explicitly consider the subsequent core task of translation, including comprehending SD elements and transferring them into a target language. Future work should include elaboration on their relationship. Although previous studies have pointed out the role and function of SD profiling in the translation process (e.g. Nord, Citation2005; Reiss & Vermeer, Citation1991/Citation2013), the detailed linkage between SD properties and translation strategies has not been comprehensively investigated. Since frameworks and terminologies of translation strategies have already been proposed (e.g. Chesterman, Citation2016; Molina & Albir, Citation2002; Vinay & Darbelnet, Citation1958/Citation1995), efforts should be invested in identifying which SD properties prompt the use of which strategies. These attempts to establish terminologies and their relations would eventually lead to the explicit understanding of translation processes, which can contribute not only to theoretical discussions in the field of translation studies but also to translation practices.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Professor Kyo Kageura of the University of Tokyo for useful discussions on the notion and role of documents in translation. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rei Miyata

Rei Miyata, PhD, is Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Japan. His main research topic is the development of natural language processing technologies for document authoring and translation. His publications include Controlled Document Authoring in a Machine Translation Age (Routledge, 2020) and Metalanguages for Dissecting Translation Processes: Theoretical Development and Practical Applications (co-edited, Routledge, forthcoming 2022).

Notes

1 In the field of translation studies, the term ‘source text’ (ST) is commonly used to refer to the object to be translated in the source language, but, in this article, ‘source document’ (SD) has been deliberately adopted. The rationale for this choice is discussed in Section 2.

2 Although the range of SD properties to be identified can be defined on an ad hoc basis, in practical translation projects, it is effective to define the scheme of SD profile, i.e. a list of the SD properties to be identified, in advance.

3 The book by House (Citation2014) was used to refer to the work of House (Citation1977) and House (Citation1997), reference notations of which are House, ([Citation1977] Citation2014) and House ([Citation1997] Citation2014), respectively.

4 Importantly, these books were selected by Munday (Citation2016, pp. 113–114) as ‘key texts’ in translation studies. Hence, it is reasonable to refer to them as a point of departure.

5 The terms ‘geolect’, ‘chronolect’, and ‘sociolect’ have been adopted from Young and Harrison (Citation2004, pp. 35–36).

6 This view also overlaps the term ‘idiolect’, which is the ‘characteristics of the speech of an individual, as against a dialect’ (Jackson, Citation2007, p. 85).

7 In the field of language education, for example, Berry (Citation2010) extensively discusses the role of terminologies or metalanguages.

References

- Bassnett, S. (2013). Translation studies (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Bedard, C. (2000). Memoire de traduction cherche traducteur de phrases … Traduire, 186, 41–49.

- Berry, R. (2010). Terminology in English language teaching: Nature and use. Peter lang.

- Biber, D., & Conrad, S. (2009). Register, genre, and style. Cambridge University Press.

- Bowker, L. (2005). Productivity vs quality: A pilot study on the impact of translation memory systems. Localisation Focus, 4(1), 13–20.

- Buckland, M. K. (1997). What is a ‘document’? Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(9), 804–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199709)48:9<804::AID-ASI5>3.0.CO;2-V

- Buckland, M. K. (2018). Document theory. Knowledge Organization, 45(5), 425–436. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2018-5-425

- Buhler, K. (1934). Theory of language: The representational function of language (D. F. Goodwin, Trans.). John Benjamins.

- Burchardt, B., & Lommel, A. (2014). QT-LaunchPad Supplement 1: Practical Guidelines for the Use of MQM in Scientific Research on Translation Quality. http://www.qt21.eu/downloads/MQM-usage-guidelines.pdf.

- Chesterman, A. (2016). Memes of translation: The spread of ideas in translation theory (2nd ed.). John Benjamins.

- EMT. (2017). European Master’s in Translation Competence Framework 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/emt_competence_fwk_2017_en_web.pdf.

- Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins.

- Hatim, B., & Mason, I. (1997). The translator as communicator. Routledge.

- Holmes, J., & Wilson, N. (2017). An introduction to sociolinguistics. Routledge.

- House, J. (1977). A model for translation quality assessment. Narr. (in House, 2014, 21–53).

- House, J. (1997). Translation quality assessment: A model revisited. Narr. (in House, 2014, 63–84).

- House, J. (2014). Translation quality assessment: Past and present. Routledge.

- Hudson, R. A. (1996). Sociolinguistics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ISO. (2012). ISO/TS 11669:2012. Translation Projects – General Guidance. International Organization for Standardization.

- ISO. (2015). ISO 17100:2015. Translation Services – Requirements for Translation Services. International Organization for Standardization.

- Jackson, H. (2007). Key terms in linguistics. Continuum.

- Jakobson, R. (1959/2013). On linguistic aspects of translation. In R. Brower (Ed.), On Translation (pp. 232–239). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1959).

- Lommel, A., Uszkoreit, H., & Burchardt, A. (2014). Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM): A Framework for Declaring and Describing Translation Quality Metrics. Tradumatica, 12, 455–463. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.77

- Lund, N. W. (2010). Document, text and medium: Concepts, theories and disciplines. Journal of Documentation, 66(5), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411011066817

- Molina, L., & Albir, A. H. (2002). Translation techniques revisited: A dynamic and functionalist approach. Meta, 47(4), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.7202/008033ar

- Mossop, B. (2006). Has computerization changed translation? Meta, 51(4), 787–805. https://doi.org/10.7202/014342ar

- Munday, J. (2016). Introducing translation studies: Theories and applications (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Newmark, P. (1988). A textbook of translation. Prentice Hall.

- Nord, C. (2005). Text analysis in translation: Theory, methodology, and didactic application of a model for translation-oriented text analysis (2nd ed.). Rodopi.

- Nord, C. (2018). Translating as a purposeful activity: Functionalist approaches explained (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Olohan, M. (2020). Translation and practice theory. Routledge.

- PACTE. (2000). Acquiring translation competence: Hypotheses and methodological problems of a research project. In A. Beeby, D. Ensinger, & M. Presas (Eds.), Investigating translation (pp. 99–106). John Benjamins.

- Palumbo, G. (2009). Key terms in translation studies. Continuum.

- Reiss, K. (1971/2000). Translation Criticism – The Potentials and Limitations: Categories and Criteria for Translation Quality Assessment (E. F. Rhodes, Trans.). St. Jerome. (Original work published 1971).

- Reiss, K., & Vermeer, H. J. (1991/2013). Towards a general theory of translational action: Skopos theory explained (C. Nord, Trans.). Routledge. (Original work published 1991).

- Sager, J. C. (1997). Text types and translation. In A. Trosborg (Ed.), Text typology and translation (pp. 25–41). John Benjamins.

- Schneider, D., Zampieri, M., & van Genabith, J. (2018). Translation memories and the translator: A report on a user survey. Babel, 64(5–6), 734–762. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00062.sch

- Shuttleworth, M., & Cowie, M. (1997). Dictionary of translation studies. St. Jerome.

- Snell-Hornby, M. (1995). Translation studies: An integrated approach (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins.

- Vinay, J.-P., & Darbelnet, J. (1958/1995). Comparative stylistics of French and English: A methodology for translation. John Benjamins. (Original work published, 1958).

- Young, L., & Harrison, C. (2004). Systemic functional linguistics and critical discourse analysis: Studies in social change. Continuum.

Appendix.

Correspondence between the formulated terms and collected original terms

Table A1. Knowledge properties.

Table A2. Communication properties.

Table A3. Formation properties.

Table A4. Text properties.