ABSTRACT

Following the Bologna reform, Translation Work Placement, designed as a practical, hands-on experience in translation, has become a compulsory part of EMT translator training at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Combined with courses entailing Situated Learning and professional aspects of translation, it offers an insight into real-life translation practices enabling MA-level trainee translators to gain new skills and experience. This paper explores the work-readiness of future translators from the perspective of Language Service Providers (LSPs) offering work placement to trainees from the University of Ljubljana. Our study investigates the expectations and impressions of Slovene LSPs on trainee translators’ profession-related knowledge, skills and competences. The findings of the survey with LSPs in Slovenia reveal that Translation Work Placement is a contributing factor in bridging the gap between the educational and workplace settings. However, the results of the study also show that in addition to the development of disciplinary knowledge, skills and competences, translator training could place more efforts into the acquisition of those transferable skills and competences which foster professional development and enhance employability in the ever-changing professional workplace settings.

1. Introduction

To enhance the work-readiness of translation graduates of the University of Ljubljana and equip them with the knowledge, skills and competences expected on the labour market in Slovenia, it seems important to establish what expectations employers have on trainee translators’ readiness for professional workplace settings. Since the translation market in Slovenia is rather small, there is heavy competition in language service provision. Therefore it seems useful for educational institutions to gain an insight into the requirements of professional settings to provide suitable training to trainee translators for their future professional life (cf. Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2020). Situated Learning, highlighting the importance of simulated professional practices while using authentic materials in translator training, as well as profession-related entrepreneurial and occupational aspects, may provide a useful framework for this purpose (for more details on Situated Learning, entrepreneurial prospects and employability, see Astley & Torres Hostench, Citation2017; Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, Citation2017; Calvo, Citation2011, Citation2015; Calvo et al., Citation2010; Chouc & Calvo, Citation2010; Cuadrado-Rey & Navarro-Brotons, Citation2020; Galán-Mañas et al., Citation2020; Gonzalez, Citation2014; Katan, Citation2009; Kearns, Citation2008; Kelly, Citation2005; Kiraly, Citation2005, Citation2016; D. Li, Citation2007; Massey & Ehrensberger-Dow, Citation2014; Milton, Citation2004; Muñoz-Miquel, Citation2020; Pym, Citation2003, Citation2013; Pym et al., Citation2016; Risku, Citation2002, Citation2016; Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, Citation2020; Schmitt et al., Citation2014; Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017; Vandepitte, Citation2009; Way, Citation2016).

As the Department of Translation Studies in Ljubljana endeavours to facilitate its graduates’ employment prospects and raise their awareness of the realia of their profession, its EMT programme combines translation seminars focused on Situated Learning, a course on professional aspects of translation and compulsory Translation Work Placement (TWP). However, to our knowledge, no in-depth studies on the effects of Situated Learning nor the work-related skills, competences and personal attributes expected by LSPs have so far been conducted in Slovenia.

The specific relevance of employers’ perspective has been highlighted by Gabr (Citation2007, p. 70) who maintains that ‘[e]mployers, as suppliers of internships and on-the-job training opportunities, can help students to bridge the theory-practice gap’. In an effort to improve translator training and create conditions that might ease bridging ‘the theory-practice gap’, an exploratory study was designed to reveal the perspective of Slovene LSPs. This paper aims to explore employers’ views on the profession-related knowledge, skills and competences of trainee translators required to facilitate their integration with the labour market. We intend to gather information on the tasks assigned to trainees during their work placement, elicit information on LSPs’ impressions of trainees’ performance and assess what LSPs perceive as valuable personal assets required in the profession. The results of the study could be used to establish whether TWP is a contributing factor to better employment prospects and whether there are aspects of translator training that require further adjustments to better facilitate our graduates’ transition from educational to professional workplace settings.

2. Employability and work placement: employers’ perspective

2.1 Situated Learning, employability, employment prospects

Parallel to the ongoing debate in Translation Studies on whether translator training should match the market needs or not, and to what extent, Situated Learning combined with the development of entrepreneurial competence and occupational integration training has increasingly been gaining prominence in translator training (cf. Berthaud & Mason, Citation2018; Calvo, Citation2011, Citation2015; González-Davies & Enríquez-Raído, Citation2016; Gouadec, Citation2007; Kelly, Citation2008; Kiraly, Citation2005, Citation2016; Pym, Citation2003; Pym et al., Citation2016; Risku, Citation2002, Citation2016; Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, Citation2020; Torres-Hostench, Citation2012; Vandepitte, Citation2009; Way, Citation2016, to name just a few). González-Davies and Enríquez-Raído (Citation2016, p. 3) highlight the importance of implementing ‘various pedagogical procedures through simulated work, real-life work or a combination of both’ to equip trainees with the necessary profession-related competences. They underline that ‘optimal pedagogical procedures in Situated Learning aim at facilitating the transition from (near-)authentic task- and/or project-based work to real-life professional practice’ (González-Davies & Enríquez-Raído, Citation2016, p. 3). This can be achieved through collaborative learning in simulated practices involving real-life activities, tasks and projects (cf. González Davies, Citation2004; González-Davies & Enríquez-Raído, Citation2016; Kiraly, Citation2005) while using authentic materials where professional settings are embedded in translator training. In addition, trainee translators can also engage in professional workplace settings where they ‘engage in real-life professional work and/or settings facilitated through work placement schemes’ (cf. González-Davies & Enríquez-Raído, Citation2016, p. 3). All this may ‘encourage the wider community of researchers, key industry players and practitioners to ‘focus on the long-neglected economic and financial aspects of the profession’ (González-Davies & Enríquez-Raído, Citation2016, p. 4) as well as on issues related to graduates’ employability.

As a term, employability has been widely established in higher education institutions (HEIs) and has ‘come to be understood as a set of skills that enable students to become employable in today's very competitive labour market’ (Rodríguez de Céspedes et al., Citation2017, p. 103). Together with entrepreneurial aspects it has recently gained considerable scholarly attention also in translation and interpreting studies (cf. Astley & Torres Hostench, Citation2017; Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, Citation2017; Calvo, Citation2011, Citation2015; Calvo et al., Citation2010; Chouc & Calvo, Citation2010; Katan, Citation2009; Klimkowska & Klimkowski, Citation2020; D. Li, Citation2007; Massey & Ehrensberger-Dow, Citation2014; Milton, Citation2004; Muñoz-Miquel, Citation2020; Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, Citation2020; Schmitt et al., Citation2014; Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017; Vandepitte, Citation2009; Way, Citation2016 among others), foregrounding in particular that ‘HEIs and LSPs should collaborate further to bridge the so-called gap existing between academia and the labour market’ (Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, p. 110).

Although the term employability has been widely used in literature, it is still quite a challenge to determine what exactly it entails. Yorke (Citation2006, p. 8) defines employability as ‘[…] a set of achievements – skills, understandings and personal attributes – that makes graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy’. It relates to the prospects of graduates to grow professionally in the society, and not only to what is currently demanded on the labour market, which is bound to undergo significant changes over the next few years, in particular, due to the speedy advances in the technology and AI.

Defining the term skills is no less of a challenge, as Cinque (Citation2016) asserts that the terms ‘skill’ and ‘competence’ are often used interchangeably, although they can seldom be used synonymously. The European Qualifications Framework (EQF)Footnote1 provides a set of descriptors relevant to qualifications, which also cover the concepts related to:

Knowledge: i.e., the ‘facts, principles, theories and practices’ of a field of expertise, which is theoretical and/or factual;

Skills: i.e., the ability to apply knowledge to accomplish tasks and solve problems, which are either cognitive (i.e., the use of logical, intuitive and creative thinking) or practical (i.e., the use of methods, materials, tools and instruments); and

Competence: i.e., the ability to use knowledge, skills and personal, social and/or methodological abilities needed for professional and personal development (cf. Ornellas, Citation2018, p. 1327).

Initiated by the EMT, the OPTIMALE large-scale survey helped identify the essential skills and competences employers in the language service industry were looking for in their future employees. The list is quite extensive: from being able to produce quality translation and apply quality control procedures, to being able to identify the requirements of their clients, while also being aware of the ethical behaviour and professional standards (cf. Toudic, Citation2012). Translator competence models have managed to provide sound albeit constantly changing grounds for further studies on employability and employment prospects. Together with several associations from the language industry (i.e., ELIA, EUATEC and GALA), the Directorate-General of Translation at the European Commission has been investigating the field as part of the annual Expectations and Concerns of the European Language Industry Survey since 2016. Their findings foreground the importance of translation-related professional aspects and skills: from general communication and language skills to organisational, interpersonal, negotiation, team-working and ICT skills, which should be supported by formal qualifications in translation/interpreting or a similar language-related field.Footnote3

However, Rodríguez de Céspedes (Citation2017, p. 108) is correct in highlighting that ‘employability entails a series of skills that go beyond the aim of becoming part of the labour market’. Although there are a number of studies outlining activities related to employability and professional aspects of translation, exploring, in particular, the relationship between translator training and the translation market requirements (cf. Al-Batineh & Bilali, Citation2017; Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, Citation2017; Calvo, Citation2011, Citation2015; Calvo et al., Citation2010; Chouc & Calvo, Citation2010; Cuadrado-Rey & Navarro-Brotons, Citation2020; Galán-Mañas et al., Citation2020; Katan, Citation2009; Kelly, Citation2005; D. Li, Citation2007; Massey & Ehrensberger-Dow, Citation2014; Milton, Citation2004; Muñoz-Miquel, Citation2020; Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, Citation2020; Schmitt et al., Citation2014; Thelen, Citation2014), ‘Language Service Providers (LSPs) still confirm that, generally speaking, graduates are not fully prepared for the translation profession’ (Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, p. 110). Chouc and Calvo (Citation2010) report that according to a survey with the UK employers (cf. Archer & Davison, Citation2008) the top three skills most valued by employers are communication skills, team-working skills and integrity, while some of the most highly rated skills in Spain (cf. University of Murcia, in Chouc & Calvo, Citation2010, p. 73) are related to teamwork, adaptability, problem-solving, self-management and interpersonal skills: these are all transferable or soft skills, which can be useful in a variety of jobs and industries, rather than just LSP industry skills. Employers in the UK also report their disappointment with graduates’ attitudes to work, self-management, business awareness and foreign language skills, while their Spanish counterparts underline the problems related to the knowledge of at least two foreign languages, IT skills and management skills (Chouc & Calvo, Citation2010, p. 73). However, no similar studies have been conducted for Slovenia, so currently little information is available on the LSPs’ employment and employability expectations.

Schnell and Rodríguez (Citation2017, p. 160) note that there has been ongoing pressure on HEIs ‘to meet the needs of an increasingly knowledge-driven economy and to produce competent, knowledgeable, flexible and employable graduates’. This is one of the reasons why the notion of employability is increasingly gaining prominence and scholarly attention (cf. Chouc & Calvo, Citation2010; Cinque, Citation2016; Gonzalez, Citation2014; Katan, Citation2009; King, Citation2017; D. Li, Citation2007; X. Li, Citation2018; Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017; Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017; Yorke & Knight, Citation2004), although it is often misunderstood and mingled with market demands and the rate of employment. Schnell and Rodríguez (Citation2017, p. 164) believe that employability should be discussed in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes related to the discipline, complemented by generic skills and competences (i.e., transferable and soft skills related to personal attributes) and job-related professional skills (such as self-management skills, team-working skills and similar). These present the key assets from which our graduates will be gaining and developing throughout their professional lives as active members of society. Translator training should therefore not be reduced to educating graduates for the current translation market, where things are rapidly changing, nor for the immediate needs of LSPs. Instead, translator training should empower graduates to be flexible and adaptable to withstand the quick labour-market changes and continue with their professional and personal development to remain employable throughout their careers.

It thus seems well-worth exploring the acquisition of graduates’ profession-specific knowledge, skills and competences, and aligning them with the current perceptions of employers on work-readiness for their future profession (cf. Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017, p. 161). As the Department of Translation Studies in Ljubljana wishes to prepare its graduates for later integration with the labour market, it introduced – as part of its EMT translator training – a compulsory Translation Work Placement scheme, briefly outlined in the next section of the paper.

2.2 Translation Work Placement at the University of Ljubljana

The Bologna reform foregrounds the role of work placement in HE programmes; as a result, Translation Work Placement was introduced as an integral part of EMT translator training at the University of Ljubljana (UL). The Department of Translation Studies in Ljubljana is the only EMT institution in Slovenia. Translation Work Placement was made a compulsory component of its MA curriculum for first-year students of Translation/Interpreting to raise their awareness of the realia of their profession. Combined with translation seminars focused on Situated Learning, where project work and team collaboration are employed, as well as a course on the professional aspects of translation, our Translation Work Placement scheme endeavours to prepare its graduates for the challenges of their future careers.

Translation Work Placement (TWP) spans over three weeks (120 hours, 6 Credit Points) and can be extended for additional three weeks (6 CP) as an elective. It is designed as a practical course, providing a hands-on experience in professional translation workplace settings. Offering an insight into real-life translation practices, it is instrumental for the development of MA-level trainee translators’ skills and competences as it helps them to gain translation confidence necessary for their future profession. Currently, the department has formal co-operation agreements on work placement with a multitude of different employers, from both EU institutions to Slovene LSPs from public and private sectors. As the traineeship at the EU is much longer than the three-week TWP required at our department, it is not included in the study.

The main objective of TWP is to offer to all our MA students (ranging from 20 to sometimes well over 30 per academic year) a valuable practical experience in professional settings through working with state-of-the-art translation technologies used by professional LSPs. Ensuring a TWP with the actual LSPs takes a lot of time and effort and could be highlighted as a forte of EMT translator training in Slovenia, in particular as some translation departments in countries with a large number of students (in France, Italy, Spain or the UK, for example) find it challenging to enable TWP in professional translation settings to all of their students (cf. Calvo, Citation2015, p. 317), and instead have to come up with alternative solutions.

The outcomes of the language-industry surveys (cf. Expectations and Concerns of the European Language Industry Report Citation2020 and earlier) show that a wide range of work-related skills and competences is required from translation professionals: from general communication and language skills to organisational, interpersonal, negotiation, team-working and ICT skills, which should also be supported by formal qualifications in translation/interpreting or a similar language-related field. This suggests that more efforts on part of HEIs should be placed into becoming familiar with the expectations of all the stakeholders. Schnell and Rodríguez (Citation2017, p. 163; see also Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2020) believe that to ‘bridge the gap between academia and workplace reality’ we also need to be taking into account ‘the employers’ perspective, regarding the specific requirements they place on staff attributes and expertise’.

This paper, therefore, aims to explore the perceptions and expectations of Slovene LSPs on work-readiness, i.e., the profession-related knowledge, skills and competences required to facilitate trainee translators’ transition to the labour market. The following research questions are addressed:

What are Slovene LSPs’ expectations on the profession-related knowledge, skills and competences of trainee translators?

What tasks are assigned to trainees and which text types are most frequently commissioned for translation during their work placement?

What are LSPs’ impressions of translation performance during TWP and their satisfaction with trainees? Is TWP a contributing factor to better employment prospects?

3. The study

3.1 Instrument

For the purposes of this study, both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered. The results were subsequently analysed and are presented in Section 4. Quantitative and qualitative data were obtained through an online questionnaire, designed using Google Forms survey platform administered to employers via an emailed invitation requesting their participation. The questionnaire consists of 20 items and comprises six main sections (general data, work placement organisation, mentoring scheme, employer expectations of trainee translators’ skills and knowledge, tasks assigned, employer satisfaction with trainees’ performance).

Section 1 comprises 14 items, aiming to collect general information on the respondents, i.e., eliciting data on LSP profile, the organisational aspects of TWP, plans to offer TWP in the future and plans to hire trainee translators who had completed work placement in their organisation.

The second part of the questionnaire (Sections 2, 3 and 5) is designed to gather information on the tasks assigned to trainees during their work placement, LSPs’ expectations and perceptions of trainees’ performance, drawing on similar studies focusing on expected skills and competences related to employability and/or entrepreneurial aspects (cf. Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, Citation2017; Cuadrado-Rey & Navarro-Brotons, Citation2020; Galán-Mañas et al., Citation2020; Gonzalez, Citation2014; Horbačauskiene et al., Citation2017; Klimkowska & Klimkowski, Citation2020; X. Li, Citation2018; Muñoz-Miquel, Citation2020; Rodríguez de Céspedes, Citation2017, Citation2020; Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017). In Sections 4 and 6, the questionnaire seeks to explore employers’ opinions on the skills and knowledge of trainees required prior to TWP. LSPs were also requested to provide information on their impressions of trainees’ performance during TWP and their perceptions of the need for additional training. In Section 4, eliciting data on employer expectations, and Section 6, showing employer satisfaction with trainees’ performance, LSPs were asked to respond to short statements (a total of 20 and 21 statements in each section) using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with responses expressing their agreement or disagreement with the given statements ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ (with additional options providing a choice between ‘somewhat agree’, ‘neither’ and ‘somewhat disagree’). Information on the tasks assigned to trainees during their TWP was elicited from a number of multiple-choice questions in Section 6. In an open-ended part of the questionnaire, offered after each main section, the respondents were encouraged to provide their own comments. The questionnaire was piloted prior to its distribution.

3.2 Respondents

The targeted respondents were representatives of LSPs in Slovenia, who regularly offer TWP to MA-level trainee translators studying at the University of Ljubljana. In addition, several members of the Association of Translation Companies in Slovenia were also asked to participate, since they are the largest industry players with an expressed interest in entering the TWP scheme. Consequently, a total of 32 LSPs were invited to participate.

3.3 Data collection and data analysis

The questionnaire was available online for two weeks in May 2019; a reminder was sent to participants after 10 days. In the two weeks, 21 respondents completed the questionnaire in full. This is a surprisingly high response rate since almost 70% of all participants responded (in comparison, Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017, p. 166, report that 30 out of the total of 155 respondents accessing their online questionnaire completed the entire questionnaire; Horbačauskiene et al., Citation2017, p. 151, report of a 46% employer response rate in their study; a fairly low employer response rate is also reported in Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, Citation2017, p. 149).

The results were analysed based on the quantitative and qualitative data obtained through the online questionnaire. Even though not all LSPs in Slovenia took part in the survey, but only those that offer TWP to UL trainee translators, the results nevertheless provide a solid overview of perceptions and expectations on the key skills, competences, knowledge as well as personal attributes of our graduates.

4. Results of the questionnaire

Responses by 21 LSPs that completed the entire questionnaire were analysed for the purposes of this study.

4.1 Type of employer and provision of Translation Work Placement

As far as the types of TWP providers participating in the study are concerned, an equal share of respondents (60% or 30% each) were either the representatives of translation agencies or public institutions with translation departments, 35% of responses came from the representatives of translation companies, and 5% from press agencies.

Some LSPs have long been involved in TWP in Slovenia (longest for 20 years, and 8 LSPs for over 10 years), while some LSPs are newcomers and have been engaged in TWP offered to MA trainee translators for only about a year or two; the respondents’ average engagement in TWP is just under 8 years (mean = 7.76).

A three-week TWP seems well suited to about three-quarters of LSPs (76%). The remaining quarter (24%) believe that this time framework is not suitable: 2 LSPs stated that TWP should last for at least one month, while 3 LSPs explicitly commented that work placement should last from 3–6 months.

4.2 Importance of formal qualification and disciplinary knowledge

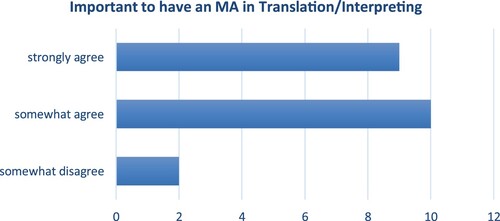

When asked about the importance of formal qualifications (see ), 92% of the LSPs participating in the survey stated that having an MA degree in Translation/Interpreting was important; only 2 LSPs were not entirely convinced about the importance ascribed to formal qualifications.

4.2.1 Importance ascribed to the knowledge of languages and cultures and trainee translators’ computer literacy

When asked about the importance of language skills and knowledge of cultures 17 out of 21 LSPs (81%) strongly believe that trainee translators ought to have an excellent knowledge of their working languages and cultures. Even more respondents foregrounded the importance of computer literacy for future translators: all but one LSP (95%) strongly agreed this is a key asset.

4.3 Impressions of trainee translators’ knowledge

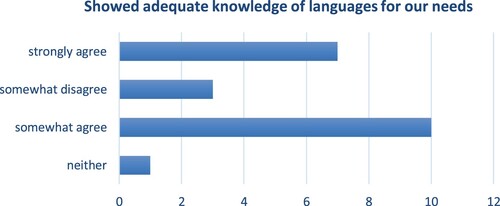

The employers were also asked about language knowledge, general world knowledge and cultural background knowledge of trainee translators during their TWP. Well over three-quarters of LSPs believe that the trainees demonstrated adequate language knowledge for their company requirements (7 strongly agree (33%), 10 somewhat agree (48%)), only 3 (14%) somewhat disagree, while one LSP (5%) was undecided (cf. ).

However, there was more variety in responses related to the trainees’ general world knowledge and cultural background knowledge: as far as general world knowledge is concerned, 3 LSPs (i.e., 14%) expressed a strong agreement with adequate general world knowledge shown by trainees, 13 agreed with this to some extent (62%), while 5 LSPs could not decide (24%). Similar responses were given on the trainees’ cultural background knowledge: only 3 LSPs strongly agreed that there was an adequate display of cultural background knowledge (14%), 12 LSPs responded that they somewhat agree (57%) with this statement, 1 somewhat disagreed (5%), while 5 LSPs marked option neither (24%).

The LSPs participating in the study also believed that, overall, the trainees know enough about translation technologies (10, i.e., 48% strongly agree, 3 (14%) agree with this to some extent, 3 LSPs (14%) somewhat disagree, while 5 marked neither (24%)).

4.4 Professional skills, work discipline, work ethics and interest in translation

As far as professional skills are concerned, just over half of the participating LSPs (13 out of 21) believe that the trainees have the necessary professional skills required for a successful integration with the translation market at least to some extent (strongly agree: 29%, somewhat agree: 33%).

In the comments’ box, one representative of LSPs stated that ‘[i]n general, the professional knowledge has increased over the years’Footnote4 which indicates that introducing the compulsory TWP scheme and a course on the professional aspects of translation to our MA curriculum might gradually be bringing results. On the other hand, there was a comment posted that ‘[t]he students need additional training in aspects related to the entrepreneurial environment in order to be adequately prepared to enter the labor market’. This suggests that further work is required in better equipping the students with the expected professional skills.

LSPs also responded that the trainees, in general, had no problems with work discipline during their TWP (12 LSPs or 57% strongly agree, while 6 (29%) somewhat agree) and were aware of professional conduct, ethical standards and professional behaviour (8 LSPs strongly agree (38%), while 11 LSPs agree to some extent (52%), see ).

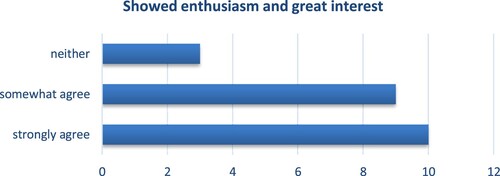

In general, LSPs seemed to believe that most trainees have good work ethics (strong agreement: 18 out of 21 LSPs, i.e., 86%), are enthusiastic about their work and show great interest in translation work (9 LSPs expressed strong agreement: 42%, while 8 somewhat agreed: 38%, as evident from ).

4.5 Most valued personal skills and attributes

When asked about the skills and personal attributes that they value the most, LSPs listed interpersonal skills (95% agreement), team-working skills (90% agreement), communication skills (86% agreement), organisational skills (86% agreement) and negotiation skills (48% agreement). Also highly appreciated is critical thinking (90% agreement). No LSPs disagreed with the importance ascribed to these skills and attributes. In all, 18 out of 21 representatives of LSPs (i.e., 85%) firmly believe that having good self-management skills is essential for translators, and additional 2 (10%) agree with this to some extent. Even more appreciated is the trainees’ ability to meet deadlines (strongly agree: 19 out of 21 LSPs, i.e., 91%).

There was also a strong agreement on what LSPs expect most from the trainees: that they have a positive ‘can do’ attitude (14 LSPs or 67%), show flexibility and are adaptable in a given situation (15 LSPs, i.e., 71%), are willing to learn new things (16 LSPs or 76%) – both during their work placement and in general – and, most of all, are reliable (all but one LSP, i.e., 95%, strongly agreed with this statement). Reliability is the key asset most highly appreciated by the LSPs surveyed in our questionnaire.

4.6 At the Translation Work Placement

LSPs also reported on the tasks generally assigned to trainee translators during their work placement and the text types most frequently commissioned for translation.

4.6.1 Tasks performed during TWP

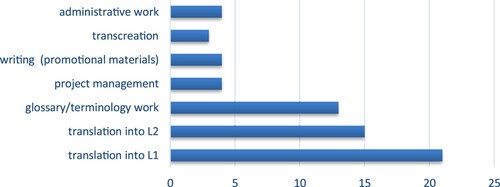

All 21 LSPs assign trainees with translation into L1, while 15 LSPs also request translation into a foreign language; this is hardly surprising, given that Slovene is a language of lesser diffusion (cf. Hirci & Pisanski Peterlin, Citation2020; Pokorn, Citation2005). Of the 21 participating LSPs, 13 have their trainees engage in glossary work and terminology tasks (see ). Project management, writing promotional materials, administrative work, transcreation and marketing-related assignments were less frequently commissioned to trainees.

4.6.2 Text types translated at TWP

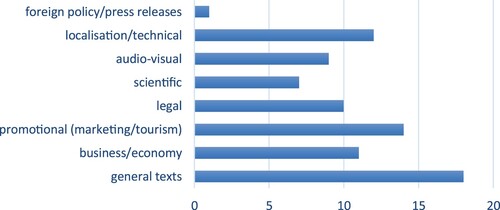

When asked about the types of texts that trainee translators are expected to translate, the answers varied quite considerably (see ): for the majority, it is general texts (18), followed by promotional texts related to marketing and tourism (14), localisation and technical texts (12), business and economy-related texts (11), legal text (10), audio-visual content (9) and texts related to foreign policy and press releases (1).

4.6.3 Needs for additional training

LSPs believe that trainee translators need additional training in first language skills (strongly agree: 40%, somewhat agree: 20%, neither: 40%), foreign language skills (strongly agree: 60%, somewhat agree: 10%, neither: 30%) and the use of CAT tools and other technology-related aspects of translation (strongly agree: 52%, somewhat agree: 20%, neither: 28%). In the open-ended comments box, some LSPs pointed out that additional training is necessary in post-editing, an increasingly growing part of translation workflow. Some comments were also concerned with the lack of motivation on part of some TWP seekers. As one LSP put it,

… our general view is that placement seekers are pretty disconnected from the actual needs and expectations of the translation labor market, while only a few of them showed the actual enthusiasm and deeper interest in translation processes and work as such. For many of them, this trainingFootnote5 was perceived only as a must and the structured 8-hr daily schedule seemed to be heavy on them.

4.7 Mentoring

All LSPs have mentors assigned to trainee translators during TWP. However, in 62% of the cases (13 out of 21 LSPs), these mentors are not remunerated for their supervision of trainees. Moreover, they are not provided with any training on proper trainee mentorship (62%). However, feedback on trainees’ translation work is one of the most valuable aspects of TWP and is highly appreciated by TWP seekers, so regular feedback from mentors should also be highlighted as one of the most crucial aspects of TWP (similar is underlined in Risku, Citation2016, p. 17).

4.8 Overall employer satisfaction with trainee translators’ performance at TWP

LSPs believe that, overall, trainee translators are satisfied with the TWP they offer (strongly agree: 62%, somewhat agree: 33%). In addition, over 60% of LSPs stated that the trainees occasionally exceed their expectations, which is quite encouraging.

What is even more encouraging is that most LSPs (17 out of 21, i.e., 81%) reported that they plan to offer employment to trainee translators who prove themselves during their TWP. Only 2 LSPs cannot offer full-time employment, but they will continue to offer work to trainees, while another LSP hopes they might be able to offer employment in the future.

5. Discussion

The present study was designed to address the expectations of LSPs in Slovenia related to the work-readiness of MA-level trainee translators from the University of Ljubljana, as well as the types of texts and tasks assigned to trainees during their work placement. The study has also enabled us to gain valuable information on LSPs’ perceptions and expectations on the profession-related knowledge, skills and competences as well as personal attributes required from future translators in Slovenia.

Only about half of the LSPs believe that the trainees have adequate profession-related skills required for a successful integration with the translation market. Moreover, fewer than half responded that there are no problems with work discipline during TWP and that the trainees are aware of professional conduct and ethical standards. This suggests that additional efforts should be placed into empowering the students to develop and expand the necessary profession-related skills (cf. also Gonzalez, Citation2014, p. 64). Introducing a course on professional aspects of translation combined with the TWP scheme might be a good start, but other activities promoting translation business know-how and fostering entrepreneurial skills, with regular rather than random lectures and workshops held by professional translators, could additionally enhance translator training in this respect (similar is suggested in Álvarez-Álvarez & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, Citation2017; Calvo, Citation2015; Cuadrado-Rey & Navarro-Brotons, Citation2020).

All LSPs surveyed assign their trainees with tasks involving translation into L1, while most LSPs also have trainees translate into L2 or have them engage in glossary and terminology work. Project management is rarely undertaken, as it requires greater expertise. Trainee translators are expected to translate general texts, followed by promotional texts on marketing and tourism, localisation and technical texts, business-related and legal texts, and audio-visual content. Other text types are less frequently commissioned. These results can serve as a guideline when decisions are made on the types of seminars offered in postgraduate translator training (cf. Kelly, Citation2005, Citation2008; X. Li, Citation2018).

Our findings have shown that over 90% of Slovene LSPs participating in the study find a degree in Translation/Interpreting important (cf. OPTIMALE survey from 2012 or Horbačauskiene et al., Citation2017, p. 152). Over half underline that additional training is required in L1, with an even more pronounced significance ascribed to improving the trainees’ foreign language skills and increasing their tech-savviness. Similarly, as underlined also in Schnell and Rodríguez (Citation2017, p. 169), additional training is required in ‘project management, CAT tools, administrative procedures’. Situated Learning with ‘project-based approaches to translator education […] where learning is dependent on authentic situations’ (Risku, Citation2016, p. 16, see also Kiraly, Citation2005, Citation2016; Olvera Lobo et al., Citation2005) combined with on-site work placement in professional workplace settings can certainly contribute to MA-level trainee translators assuming a more active, meaningful role, while integrating ‘socially into the situation and cooperation’ (Risku, Citation2016, p. 16).

Our survey has revealed that LSPs appreciate a positive ‘can do’ attitude, flexibility and adaptability, willingness to learn new things and, to some extent, negotiation skills. Also deemed highly valuable are team-working and communication/interpersonal skills and critical thinking, self-management, the ability to meet deadlines and especially reliability, mirroring, in fact, the seven principles of Situated Learning (cf. Risku, Citation2016, pp. 15–18). Similar is reported in Gonzalez (Citation2014, p. 64), while Horbačauskiene et al. (Citation2017, p. 153) voice the need for TS programmes ‘to correspond adequately to the needs of employers in respect to the development of graduates’ transferable skills’. Since these are part of the set of skills often mentioned in the literature as crucial for professional development and employability (cf. Andrews & Higson, Citation2008; Bennett, Citation2002; Gonzalez, Citation2014; Horbačauskiene et al., Citation2017; OECD, Citation2015; Orlando, Citation2016; Schnell & Rodríguez, Citation2017; Waltz, Citation2011; Yorke, Citation2006; Yorke & Knight, Citation2004), translator training should strive to address this issue in a more systematic way. Together with suitable feedback from work-placement mentors (cf. Risku, Citation2016) and post-placement (self)-reflection students could gain the necessary boost in translation confidence and find additional motivation for translation work which – as some LSPs commented in our survey – trainees occasionally lack at present. In Slovenia, trainee translators have no specific training in transferable skills. Related topics are randomly addressed in translation seminars, but it is left to individual trainers whether – or not – to highlight their importance. Yet it is precisely these skills that can earn a job to translation graduates not only in translation business but also outside the LSP industry. This again calls for a systematic in-depth training, underlining the acquisition of both transferable as well as profession-related entrepreneurial skills and competences (cf. Cuadrado-Rey & Navarro-Brotons, Citation2020, p. 66) in addition to what is already offered in translator training – in particular, since translation graduates might seek employment outside the translation industry.

The majority of LSPs participating in the study claim that they intend to employ the trainees who prove themselves during their TWP, which shows that TWP is mutually beneficial to all stakeholders (cf. Jaccomard, Citation2018). Similarly, Cuadrado-Rey and Navarro-Brotons (Citation2020, p. 76) believe that ‘internships act as a bridge between university and professional life’. This is aligned with the stance by Yorke and Knight (Citation2004, p. 13) that work experience ‘may become a passport to employability where employers use work placements as a central part of their graduate recruitment processes’.

6. Conclusion

Translation Work Placement and employability seem to be among the key concepts linking educational settings of translation graduates with professional workplace settings. Creating a partnership between academia and prospective employers from the language industry is instrumental in raising awareness of MA-level trainee translators on the requirements of their future profession.

The findings of our study focusing on Slovene LSPs’ perspective on TWP revealed that trainee translators have some awareness of the profession-related knowledge, skills and competences, but at times lack personal motivation. The study also shed light on LSPs’ expectations on the work readiness and personal attributes of trainee translators required in professional settings, highlighting the need to raise the trainees’ awareness of transferable and soft skills, including adaptability, flexibility, positive ‘can do’ attitude, teamwork and reliability, which are some of the qualities that are most appreciated by LSPs. The results of the study reflecting the types of texts and tasks commissioned by LSPs could also be considered in the curriculum design on what to incorporate into EMT translator training. However, many challenges remain, and further discussions are needed on the support offered in organising TWP and recognising its merit within the university settings, on a reward system for both trainees and mentors, as well as the quality of supervision, where additional training is required especially for TWP mentors. Also requiring further attention are ethical dilemmas related to no-remuneration placement arrangement and possible exploitation of free workforce, as well as complementary training in profession-related aspects and transferable skills to facilitate life-long professional development.

One of the shortcomings of the study is that only one side is presented due to the scope of the paper, that of LSPs. A follow-up study focusing on an enquiry into how LSPs’ expectations are mapped with the perceptions of other stakeholders could help additionally enhance translator training needed to empower translation graduates to be better prepared for their future profession.

While TWP offers trainee translators with an opportunity to establish first business contacts with professional workplace settings and to gain hands-on experience in real-life translation practices while also gaining the necessary translation confidence, the findings of the study revealed the need for further adjustments in translator training. We hope that these findings can contribute to a wider debate on how to incorporate a more in-depth, systematic guidance on the development of not only disciplinary but also profession-related transferable skills and competences. This requires further attention if translator training institutions wish to foster employment prospects and employability of their graduates, so that they can compete on the labour market and, at the same time, play an active role in our society as versatile, reflective and creative professionals – flexible enough to adapt to the ever-changing labour market throughout their professional career.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nataša Hirci

Nataša Hirci is an assistant professor at the Department of Translation Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. In 2007, she received her PhD in Translation Studies from the University of Ljubljana. Her research interests include translator training, directionality and translation into L2, digital tools and digital collaboration in translation, English phonetics and employability. She is also the Department Coordinator in charge of trainee translators’ work placement with translation service providers.

Notes

2 For more on PACTE publications, see https://ddd.uab.cat/collection/pacte?ln=es.

3 Compare the Expectations and Concerns of the European Language Industry Report (2020 and earlier).

4 These comments are provided verbatim.

5 Work placement is meant here.

References

- Al-Batineh, M., & Bilali, L. (2017). Translator training in the Arab world: Are curricula aligned with the language industry [Special issue]? The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. , 11(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1350900

- Álvarez-Álvarez, S., & Arnáiz-Uzquiza, V. (2017). Translation graduates under construction: Do Spanish translation and interpreting studies curricula answer the challenges of employability [Special issue]? The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 11(2), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344812

- Andrews, J., & Higson, H. (2008). Graduate employability, ‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’ business knowledge: A European study. Higher Education in Europe, 33(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720802522627

- Archer, W., & Davison, J. (2008). Graduate employability. The view of employers. The Council for Industry and Higher Education, 3–15. http://cced-complete.com/documentation/graduate_employability_eng.pdf

- Astley, H., & Torres Hostench, O. (2017). The European graduate placement scheme: An integrated approach to preparing master’s in translation graduates for employment [Special issue]. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 11(2), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344813

- Bennett, R. (2002). Employers’ demands for personal transferable skills in graduates: A content analysis of 1000 job advertisements and an associated empirical study. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 54(4), 457–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820200200209

- Berthaud, S., & Mason, S. (2018). Embedding reflection throughout the postgraduate translation curriculum: Using communities of practice to enhance training. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 12(4), 388–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2018.1538847

- Calvo, E. (2011). Translation and/or translator skills as organising principles for curriculum development practice. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation, 16, 5–25. http://www.jostrans.org/issue16/art_calvo.php

- Calvo, E. (2015). Scaffolding translation skills through situated learning approaches: Progressive and reflective methods. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 9(3), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2015.1103107

- Calvo, E., Kelly, D., & Morón, M. (2010). A project to boost employability chances amongst translation and interpreting graduates in Spain. In V. Pellat (Ed.), Teaching and testing interpreting and translating. Intercultural studies and foreign language learning (Vol. 2, pp. 209–226). Peter Lang.

- Chouc, F., & Calvo, E. (2010). Embedding employability in the curriculum and building bridges between academia and the workplace: A critical analysis of two approaches. La linterna del traductor, 4, 71–86. http://www.lalinternadeltraductor.org/n4/employability-curriculum.html

- Cinque, M. (2016). Lost in translation. Soft skills development in European countries. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 3(2), 389–427. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-3(2)-2016pp389-427

- Cuadrado-Rey, A., & Navarro-Brotons, L. (2020). Proposal to improve employability and facilitate entrepreneurship among graduates of the master’s degree in institutional translation of the University of Alicante. HERMES – Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 60, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v60i0.121311

- Expectations and Concerns of the European Language Industry Report. 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/2020_language_industry_survey_report.pdf

- Gabr, F. M. (2007). A TQM approach to translator training. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 1(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2007.10798750

- Galán-Mañas, A., Kuznik, A., & Olalla-Soler, C. (2020). Entrepreneurship in translator and interpreter training. HERMES – Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 60, 7–11. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v60i0.121307

- Gonzalez, M. (2014). Changing perspectives: Aligning the placement curriculum with current industry needs. Investigations in University Teaching and Learning, 9, 61–69.

- González Davies, M. (2004). Multiple voices in the translation classroom: Activities, tasks and projects. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.54

- González-Davies, M., & Enríquez-Raído, V. (2016). Situated learning in translator and interpreter training: Bridging research and good practice. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2016.1154339

- Gouadec, D. (2007). Translation as a profession. John Benjamins.

- Hirci, N., & Pisanski Peterlin, A. (2020). Face-to-face and Wiki revision in translator training: Exploring the advantages of two modes of collaboration. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 14(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2019.1688066

- Horbačauskiene, J., Kasperavičiene, R., & Petroniene, S. (2017). Translation studies: Translator training vs employers’ expectations. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 5(1), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1515/jolace-2017-0009

- Jaccomard, H. (2018). Work placements in masters of translation: Five case studies from the University of Western Australia. Meta, 63(2), 277–567. https://doi.org/10.7202/1055151ar

- Katan, D. (2009). Occupation or profession: A survey of the translators world. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 4(2), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.4.2.04kat

- Kearns, J. (2008). The academic and the vocational in translator education. In J. Kearns (Ed.), Translator and interpreter training: Issues, methods and debates (pp. 184–214). Continuum.

- Kelly, D. (2005). A handbook for translator trainers. A guide to reflective practice. St Jerome.

- Kelly, D. (2008). Training the trainers: Towards a description of translator trainer competence and training needs analysis. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Redaction, 21(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.7202/029688ar

- King, H. (2017). Translator education programs & the translation labour market: Linear career progression or a touch of chaos? T and I Review, 7, 133–151.

- Kiraly, D. (2005). Project-based learning: A case for situated translation. Meta, 50(4), 1098–1111. https://doi.org/10.7202/012063ar

- Kiraly, D. (2016). Towards authentic experiential learning in translator education. V&R Academic Mainz University Press.

- Klimkowska, K., & Klimkowski, K. (2020). Entrepreneurial potential of students graduating from translation studies. HERMES – Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 60, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v60i0.121308

- Li, D. (2007). Translation curriculum and pedagogy: Views of administrators of translation services. Target: International Journal of Translation Studies, 19(1), 105–133. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19.1.07li

- Li, X. (2018). Tailoring T&I curriculum for better employability: An exploratory case study of using internship surveys to inform curriculum modification. Onomázein: Revista de lingüística, filología y traduccíon, 40, 159–182. https://doi.org/10.7764/onomazein.40.10

- Massey, G., & Ehrensberger-Dow, M. (2014). Looking beyond text: The usefulness of translation process data. In J. Engberg, C. Heine, & D. Knorr (Eds.), Methods in writing process research (pp. 81–98). Peter Lang.

- Milton, J. (2004). The figure of the factory translator: University and professional domains in the translation profession. In D. Gile, G. Hansen, & K. Malmkjær (Eds.), Claims, changes and challenges in translation studies: Selected contributions from the EST Congress, Copenhagen 2001 (pp. 169–179). John Benjamins.

- Muñoz-Miquel, A. (2020). Translation and interpreting as a profession: Some proposals to boost entrepreneurial competence. HERMES – Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 60, 29–46. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v60i0.121309

- OECD. (2015). OECD skills outlook 2015: Youth, skills and employability. OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264234178-en

- Olvera Lobo, M. D., Castro-Prieto, M. R., Quero-Gervilla, E., Muñoz Martín, R., Muñoz-Raya, E., Murillo-Melero, M., Robinson, B., Senso-Ruiz, J. A., Vargas-Quesada, B., & Domínguez-López, C. (2005). Translator training and modern market demands. Perspectives, 13(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760508668982

- Orlando, M. (2016). Training 21st century translators and interpreters: At the crossroads of practice. Research and pedagogy. Frank & Time.

- Ornellas, A. (2018). Defining a taxonomy of employability skills for 21st-century higher education graduates. In 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’18) (pp. 1325–1332). València: Universitat Politècnica de València. http://doi.org/10.4995/HEAd18.2018.8197

- PACTE. (2015). Results of PACTE’s experimental research on the acquisition of translation competence: The acquisition of declarative and procedural knowledge in translation. The dynamic translation index. Translation Spaces, 4(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.4.1.02bee

- Pokorn, N. K. (2005). Challenging the traditional axioms: Translating into a non-mother tongue. John Benjamins.

- Pym, A. (2003). Redefining translation competence in an electronic age. In defence of a minimalist approach. Meta, 48(4), 481–497. https://doi.org/10.7202/008533ar

- Pym, A. (2013). Translation skill-sets in a machine translation age. Meta, 58(3), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.7202/1025047ar

- Pym, A., Orrego-Carmona, D., & Torres-Simon, E. (2016). Status and technology in the professionalisation of translators. Market disorder and the return of hierarchy. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 25, 54–73. https://www.jostrans.org/issue25/art_pym.php

- Risku, H. (2002). Situatedness in translation studies. Cognitive System Research, 3(3), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-0417(02)00055-4

- Risku, H. (2016). Situated learning in translation research training: Academic research as a reflection of practice. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 10(1), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2016.1154340

- Rodríguez de Céspedes, B. (2017). Addressing employability and enterprise responsibilities in the translation curriculum [Special issue]. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 11(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344816

- Rodríguez de Céspedes, B. (2020). Beyond the margins of academic education: Identifying translation industry training practices through action research. Translation and Interpreting, 12(1), 90–114. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.112201.2020.a07

- Rodríguez de Céspedes, B., Sakamoto, A., & Berthaud, S. (2017). Introduction [Special issue]. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 11(2), 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1339980

- Schmitt, P. A., Gerstmeyer, L., & Müller, S. (2014). CIUTI-Study 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303495625_CIUTISurvey2014_Schmitt

- Schnell, B., & Rodríguez, N. (2017). Ivory tower vs. workplace reality. Employability and T&I curriculum – balancing academic education and vocational requirements: A study from the employers’ perspective [Special issue]. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, , 11(2), 160–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1344920

- Thelen, M. (2014, November 8). Preparing students of translation for employment after graduation: Challenges for the training curriculum [Paper presentation]. Portsmouth, UK: Fourteenth Portsmouth Translation Conference, University of Portsmouth.

- Torres-Hostench, O. (2012). Occupational integration training in translation. Meta, 57(3), 787–811. https://doi.org/10.7202/1017091ar

- Toudic, D. (2012). The OPTIMALE employer survey and consultation report. http://www.biblit.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/OPTIMALE-report-2010.pdf

- Vandepitte, S. (2009). Entrepreneurial competences in translation training. In I. Kemble (Ed.), Proceedings of the Conference. The Changing Face of Translation. Portsmouth, UK: University of Portsmouth.

- Waltz, M. (2011). Improving students’ employability (E-book). Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.jobs.ac.uk/media/pdf/careers/resources/improving-student-employability.pdf

- Way, C. (2016). Intra-university projects as a solution to the simulated/authentic dilemma. In D. Kiraly (Ed.), Towards authentic experiential learning in translator education (pp. 147–160). Mainz University Press.

- Yorke, M. (2006). Employability in higher education: What it is – what it is not (The Higher Education Academy Learning & Employability. Series 1). York: THEA. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/hea-learning-employability_series_one.pdf

- Yorke, M., & Knight, P. T. (2004). Embedding employability into the curriculum (Learning and Employability Series). Retrieved July 14, 2020, from http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/publications/learningandemployability