ABSTRACT

This paper deals with a central aspect related to translation that has been given surprisingly little attention in Translation Studies: sameness. We study sameness in a type of translation that according to previous studies entails additional shifts and losses – indirect translation. By indirect translation we mean a ‘translation based on a text (or texts) other than (only) the ultimate source text’ Our aim is to identify what stays the same in indirect literary translation in terms of plot. Our article is based on two case studies that comprehend particularly fuzzy chains of texts: the first Finnish translations of Robinson Crusoe and Peter Pan. Our main units of analysis are the plots of both works. We approach plot from a structural perspective and utilize plot function theory in our analysis. Our main research questions are: What in the plots of the two works studied has remained unaltered throughout the textual chain? What is the relation between plot elements that have been altered versus plot elements that have remained the same?

1. Introduction

In contemporary Translation Studies, surprisingly little attention has been given to an essential and self-evident translational characteristic, one that is perhaps even too self-evident, namely samenessFootnote1 in translation, understood here as the fact that elements of the source text (for instance, semantic content, stylistic features) remain unaltered in the target text. As Mossop (Citation2017, pp. 331–332, quotation 335) points out, while ‘most of the world’s translators and interpreters are not primarily in the business of difference; they are primarily in the business of sameness’, sameness is paradoxically under-researched within the discipline. A comparable lack of interest in Translation Studies can be observed vis-à-vis similarityFootnote2, which is a related concept but less absolute than sameness. Chesterman (Citation2007, pp. 53–54) observes that, apart from the discussion on equivalence by scholars such as Catford, Nida and Koller, the main focus in Translation Studies has been on differences, shifts and not least on loss in translation. One of the reasons for this tendency could be that ‘translations are supposed to be ‘the same as’ the original, and so when we realize they are not, and cannot be, we then look at the differences’ (Chesterman, Citation2007, p. 56). Differences might be easier to point out and characterize than sameness or similarities, and differences could also be considered more interesting because they entail an element of surprise, something in the target text that cannot be expected on the basis of the source text (Chesterman, Citation2007, p. 56; see also Mossop, Citation2017, p. 335; Tymozcko, Citation2004, p. 28, 38).

The point of departure of this article is the opposite (see also e.g., Goethals, Citation2008 and Rybicki, Citation2006). Arguing that sameness is an essential characteristic of translation and worth investigating, we focus on it in a context where this aspect has not yet been addressed and where it is perhaps less likely to be found: indirect translation. By indirect translation we mean a ‘translation based on a text (or texts) other than (only) the ultimate source text’ (Ivaska & Paloposki, Citation2018, p. 43n1; see also Ivaska, Citation2020, p. 19). According to our understanding, indirect translation can entail acts of intralingual translation in addition to interlingual translation; it thus involves at least two languages (see Assis Rosa et al., Citation2017, pp. 119–120).

While we agree with Mossop (Citation2017, p. 135) that sameness is not an exotic feature in translation, we argue that in complex translation chains, where the risk of omissions or shifts seems to be higher (see Ringmar, Citation2007, Citation2012 and Hadley, Citation2017, for instance), sameness can reveal something essential about texts and their translators. Elements that remain unaltered probably show what translators and other agents participating in the translation event (editors, for example) consider the core meaning of a given text and worth transferring to the target text. These might be essential semantic elements, salient stylistic features or key terms (see Chesterman, Citation2007, p. 55, 59). The unchanged elements might also turn out to be features that are particularly easy to remember and translate.

Our research addresses issues that have rarely been thoroughly investigated in Translation Studies. In addition to studying sameness in indirect translation, we examine what happens to the components of narrative and especially the plot in literary translation. It is evident that narratives consist of many elements other than plot, such as narration, style, and presentation of the storyworld and its characters. We focus on plot since it has received less attention in Translation Studies than, for example, style (for some rare exceptions in plot analysis, see Robyns, Citation1990 and Zuschlag, Citation2016). Our analysis concerns sameness of plot, which is a subtype of semantic sameness (see below). The main research questions are: In the plots studied, what has remained unaltered throughout the translation chain? What is the relation between plot elements that have been altered and plot elements that have remained the same?

2. Data and method

Our article is based on a comparative functional analysis of the plots in two complex translation chains that originate in two classics in children’s literature: Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (Citation1719) and James Matthew Barrie’s Peter Pan (originally Peter and Wendy, Citation1911/2007). Both analysed translation chains consist of the ultimate source text, more than one mediating text and the ultimate target text (see Assis Rosa et al., Citation2017, p. 115). The texts in both chains were identified through earlier research (Martin, Citation2006; Sagulin, Citation2010; Winqvist, Citation1973) and the textual relationships were confirmed with the help of parallel readings and text comparisons (for Robinson Crusoe by Merikallio, Citation2013 and the authors and for Peter Pan by the authors). Consequently, our study concerns two cases of indirect translation proven by research (Assis Rosa et al., Citation2017, p. 119; see also Ivaska, Citation2020, pp. 26–27).

The translation chain of the first Finnish translation of Robinson Crusoe by Otto Tandefelt (Citation1847) has involved at least three acts of interlingual translation and at least three de facto source languages (see Ivaska, Citation2020, pp. 22–23, 25): the ultimate source text [L1, English] > [possibly (an)other mediating text(s)]Footnote3 > mediating text 1 [L2, German] > mediating text 2 [L3, Swedish] > the ultimate target text [L4, Finnish]. The ultimate source text was Defoe’s original text (1719). The mediating texts that can be named with some certainty are a German translation from 1841 by A. Geyger and a Swedish translation from Citation1847 by an anonymous translator (possibly Wilh. Aug. Wall, whose translation’s first edition was published in 1844) (Merikallio, Citation2013; Sagulin, Citation2010; Winqvist, Citation1973).

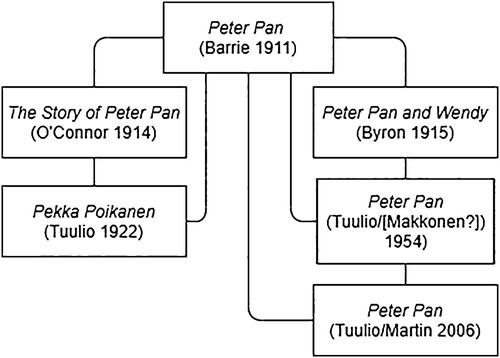

As for Peter Pan, the chain of the first translation by Tyyni Tuulio (Citation1922) and its subsequent editions involves both intralingual and interlingual translation as well as compilative (several source texts are used in one act of translation) and collaborative (several agents participate in translating or editing the text) indirect translation (see Ivaska, Citation2020, pp. 27–33). We conducted a comparative text analysis of Tuulio’s translation and the texts that Alice MartinFootnote4 (Citation2006) mentions as its source texts. The analysis was made comparing the ultimate source text (Barrie, Citation2006), shortened versions identified by Martin (Byron, Citation1915/1976; O’Connor, Citation1914/2012) and three editions of Tuulio’s translation (Citation1922; Citation1954 and Citation2006) side by side and keeping track of the presented events. Our analysis corroborated Martin’s – editor of the 2006 translation – conclusions. Martin (Citation2006, p. 126) notes that the substantial differences between Tuulio’s 1922 translation and the revised translation from 1954 can only be explained by them having different source texts. She further writes that the 1922 translation has the same illustrations as Stephen O’Connor’s adaptation, The Story of Peter Pan (Citation1914/2012). According to our analysis, Tuulio’s 1922 version was most probably based on both Barrie’s original and the O'Connors version. Tuulio’s translation was revised for a later edition, probably by Inka MakkonenFootnote5 (Tuulio[/Makkonen?] Citation1954), this time based on Barrie's original and another adaptationFootnote6, Peter Pan and Wendy by May Byron (Citation1915/1976). This version differs significantly from the 1922 edition: the main source text of the translation changes from O’Connor’s version to Byron’s version, which is an indication of retranslation rather than mere revision. Consequently, neither version uses the ultimate source text as their primary source text. As pointed out by Koskinen and Paloposki (Citation2010/2016), versions may get labelled as revisions or retranslations rather arbitrarily. Such is the case with the 1954 edition, which is stated to be a revised edition, but the person responsible for the revisions is not credited. The 1954 edition was further revised by Martin for the 2006 edition (Tuulio/Martin, Citation2006). This edition deviates little from the 1954 edition and is also based on Byron's version (see ).

3. Theoretical background

3.1. Similarity in translation = sameness + difference

Sameness and its counterpart, difference, are the quintessential factors of similarity in translation (Chesterman, Citation2007, p. 53). Tymozcko (Citation2004, pp. 36–37), for whom translation is a ‘metonymic process’, explains that since translators cannot translate everything in the source text, they must select a limited number of elements or aspects that can be rendered in the target text. They privilege certain aspects that are relevant for their translation task and might for instance have to sacrifice a stylistic effect in order to render the semantic meaning, or vice versa. Paradoxically, it is this attempt to conserve certain elements that causes dissimilarities or shifts in translation (see Mossop, Citation2017, p. 332; Tymozcko, Citation2004, p. 37). Consequently, a balanced analysis takes account of both sameness and difference in translation (see Tymozcko, Citation2004, p. 38; Chesterman, Citation2007, p. 64), which is why we also examine not only passages where the plot has changed but also passages where the plot has remained unaltered.

Chesterman (Citation2007, p. 57) proposes that similarity in translation be observed in four categories of sameness: formal, semantic, stylistic and pragmatic sameness.Footnote7 He does not describe these categories, but according to our interpretation formal sameness means syntactic invariance, such as identical phrase/clause/sentence structures in the source and target texts, no shifts of word classes or changes in person, tense and mood in verb phrases, and so forth (see Chesterman, Citation1997, p. 94). Semantic sameness refers to unchanged meaning,Footnote8 hence identical abstraction level, emphasis, deictic perspective, and, naturally, denotation (e.g., the French word chat is translated into English as ‘cat’ and not for example ‘feline’ or ‘pet’). The sameness of plot that we study in this article is a subtype of semantic sameness. By sameness of plot, we mean that the functions of the events that move the plot forward remain unchanged in translation (see below). Naturally, also other components of translated narrative, such as the description of the storyworld can be analysed from the perspective of semantic sameness, but we focus only on plot because of the limits of this article.

Stylistic sameness implies invariance in the manner of expression: schemes, tropes, rhetorical devices, and the narrative form remain the same, and so forth. Pragmatic sameness could mean identical purpose and effect on the readership of both the source and target texts (see Chesterman, Citation1997, pp. 107–112). It is obvious that these categories overlap and that for instance stylistic shifts can affect the story-level (for instance, characterization) because in literary translation narrative content is usually communicated through language (see Zuschlag, Citation2016). Furthermore, sameness in one category might require shifts in other categories.

3.2. Different approaches to plot in narratology

Plot has been described as one of the most difficult terms to define in narratology (Dannenberg, Citation2008, p. 6). The formulation of plot theory is linked to the structuralist attempts to distinguish the components of narrative. Tomashevsky (Citation1965, pp. 66–67) divides narrative into fabula and syuzhet. He defines fabula as the chronological sequence of the presented events and syuzhet as the order in which the events are presented to the reader. In Genette’s (Citation1993, p. 27) influential model, the narrative consists of three aspects: story, discourse, and narrating. By story he refers to the content of narrative, by discourse to the textual level of narrative, and by narrating to the act of producing the narrative action and the fictional situation where it takes place. One can argue that syuzhet (or discourse) encompasses much more than mere plot, for example, the literary techniques pertaining to narrative perspective and style. Placing the plot between the textual level of narrative and its event sequence as suggested by some theorists (e.g., Chatman, Citation1978, p. 43; Kukkonen, Citation2014) is one way to resolve this complication. This is also the approach taken in this article. Our focus is on how the events are presented to the reader in the form of plot, not the chronological sequence of events constructed by the reader.

A couple of main ways to conceptualize plot can be distinguished. According to Kukkonen (Citation2014), one such way is to regard plot as a dynamic development in the progress of the narrative (e.g., Dannenberg, Citation2008 Phelan, Citation1989;). Plot theories that take this approach can stress, for example, the causality of the presented events or the process in which the author designs the plot to engage readers. For example, Phelan (Citation1989, p. 15) uses the term progression to refer to the development of narrative, which is shaped by introducing, complicating and resolving (or failing to resolve) instabilities within the work. He distinguishes between two main kinds of instabilities: the ones occurring within the story, and the ones created by the discourse, such as instabilities of values and beliefs between the authors and narrators and the audience. Plot can also be approached from the perspective of the character's actions and relations: characters’ actions shape the plot as they aspire to their goals. For example, Greimas (Citation1966/1983) distinguishes six main actants (subject, object, sender, receiver, opponent, helper) and argues that their interactions create larger narrative structures.

In addition to the plot theories outlined above, efforts to form abstract representations of plot have been a central part of the development of plot theory. A prominent example of this approach is Propp’s (Citation1928/1968), classification of thirty-one functions in Russian folktales. He argues that functions are stable, constant elements in a tale, independent of how and by whom they are fulfilled, and that they constitute the fundamental components of a tale (Citation1968, p. 21). Another notable example of an attempt to form a representation of plot is Todorov’s (Citation1969, p. 75) more general model, where he defines a minimal complete plot as a shift from one equilibrium to a state of imbalance, followed by another state of equilibrium. Based on these two theories, Kafalenos (Citation2006) has developed a model of ten functions. She defines functions as ‘events that change a prevailing situation and initiate a new situation’ (Kafalenos, Citation2006, p. 6). She argues that the context in which the events are perceived is determined by the narrative, and thus the narrative guides the interpretations of the events’ function. The term function enables comparing interpretations of an event's consequences depending on this context: the same event can have different functions in different narratives.

Structural plot models describe clear, identifiable key events in narratives and are thus well suited for making plot comparisons (especially for versions of plot-driven works such as Robinson Crusoe and Peter Pan), which is why we have chosen to take this approach. Kafalenos’s model provides a macrostructure for our plot analysis, for it is general enough to be readily applicable to the different versions of Peter Pan and Robinson Crusoe, yet detailed enough to allow meaningful comparisons between them.

The concept of event is central for conducting a plot analysis. Generally, an event can be defined as a transition between states in the represented world (see, e.g., Chatman, Citation1978, pp. 31–32; Ryan, Citation1991, p. 127). Bal (Citation1985/1997, pp. 32–34) distinguishes narrative, argumentative and descriptive elements of the text. Narrative textual passages refer to the events of the fabula, argumentative passages refer to a topic external to the fabula (e.g., references to cultural attitudes), and descriptive passages help the imagined world of the fabula become visible and concrete (2009, 32–34, 36). While these categories may overlap, they provide a general framework for our analysis to distinguish the textual passages that concentrate on plot.

Numerous categorizations regarding events have been produced in narratology, such as differentiation between actions and happenings (Chatman, Citation1978, p. 44) and processes and instantaneous events (Ryan, Citation1991, pp. 127–128). In the context of this article, one categorization of events is especially important: whether the event advances the plot or not. As Ryan (Citation1991, p. 125) points out, narratologists have long been aware of the importance of distinguishing between the information that moves the plot forward and the information that does not. Chatman (Citation1978) uses the terms kernels and satellites and Ryan (Citation1991) the terms narrative and descriptive elements to describe this difference. In this article, we determined which parts of the narrative advance the plot and which ones do not with the help of Kafalenos’s model: if an event moves the plot forward, it is categorized as a function.

Kafalenos’s functions follow the same pattern as Todorov’s model, shifting from the state of equilibrium to a state of instability and back to equilibrium. She defines the ten functions as follows:

The following Kafalenos’ modelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s version of the fairy tale ‘The Princess and the Pea’ illustrates how the functions are defined in practice:

At the beginning of ‘The Princess and the Pea’, the prince realizes there’s an imbalance in the equilibrium: he needs a princess to fulfil his future role as king but does not have a princess (function ‘a’).Footnote10 The structure of the fairy tale follows the quest to find a princess until she is found and thus the equilibrium is restored. As the example demonstrates, Kafalenos’s model is flexible: not every narrative includes every function, and one function can appear numerous times in one narrative (Citation2006, p. 8, 37). As such, the model is a useful analysing tool for the purposes of this article.

4. The analysis

4.1. Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe tells the story of the eponymous character’s life in England and overseas and recounts his twenty-eight years on a desert island before he is rescued and returned to England. When we apply Kafalenos’s model to the plot of the ultimate source text, the key points can be listed as follows:

At the beginning of the ultimate source text Crusoe neglects his father’s advice and runs away to sea (A1, a destabilizing event). His ship is wrecked, but he does not return home. He has several adventures overseas: he is captured by Turkish pirates, spends two years in slavery at Salé, escapes by boat with a boy named Xury and is rescued by a Portuguese ship. Crusoe settles in Brazil and starts a plantation (a new equilibrium). Eight years after running from his paternal home Crusoe goes on a slaving trip to Guinea. He shipwrecks near a desert island and is the only survivor (A2, a second destabilizing event). In the following years, he manages to build an organized and comfortable life on the island. Fifteen years after the shipwreck, he discovers a fresh human footprint in the sand and three years later observes that other humans, cannibals, occasionally visit the island. After some years of circumspection, he plans to face the cannibals and save one of their captives in order to get to the mainland. Twenty-five years after his shipwreck, he rescues a captive – Friday – from their hands. He intends to leave the island together with Friday (F). Their preparations are interrupted by cannibals who arrive with other captives, including Friday’s father and a Spaniard, who is one of seventeen sailors rescued by Friday’s people some years earlier. Crusoe, Friday and the Spaniard fight the cannibals victoriously. The Spaniard and Friday’s father leave for the mainland to bring the other sailors and build a ship that could take them to Europe (F2). Before their return an English vessel with mutineering sailors anchors near the island. With the help of Robinson and Friday, the captain of the ship manages to seize his ship again (C-actant’s primary action to alleviate A2). The English vessel takes Robinson back to England, with Friday (success of the primary action to alleviate A2). Robinson discovers that his parents are dead (failure of the primary action to alleviate A1) but that he has two sisters and two nephews from one of his deceased brothers. He settles his affairs concerning the plantation in Brazil by travelling to Lisbon and becomes a wealthy man. He takes his nephews under his care, marries and has three children (success of the primary action to alleviate A1). His wife dies. He leaves England with one of his nephews and visits his island. This voyage is recorded in the sequel of Robinson Crusoe.Footnote11 (Defoe, Citation1719/2007, pp. 269–271 and passim.)

According to our analysis, the German and Swedish mediating texts and the Finnish ultimate target text bear a strong resemblance, which is why it seems justified to claim that they are part of the same translation chain (see Winqvist, Citation1973, p. 41). If we believe the cover page of the first mediating text, Geyger’s translation, it was made from the English original. That is possible, since Geyger’s version contains all the key points of the ultimate source text’s plot except for the unfolding (I1). It also mediates – though in a condensed form – the main themes of the ultimate source text as identified by Keymer (Defoe, Citation1719/2007, p. vii): ‘a study of solitary consciousness; a parable of sin, atonement, and redemption; a myth of economic individualism’. However, it is also possible that Geyger’s source text is an abridged piracy or an adaptation in the English language. It might even be an earlier German translation (see note 3). In his preface, Geyger (Citation1841, iii) mentions that his affordable adaptation is aimed at poor children. Despite this, his version is not a censored version of the ultimate source text. For example, Crusoe’s usage of tobacco and rum and the brutal details concerning cannibalism have been retained in Geyger’s translation as well as in the Swedish and Finnish versions that follow Geyger’s text very closely. There are several possible explanations for the contradiction between the stated target audience and the actual makeup of the translation, the most obvious ones being genre expectations and a different conception of what is suitable for children in the 1840s.

The macrostructures of the German, Swedish and Finnish versions are very similar.Footnote12 The three versions are brief compared to the ultimate source text. We observed similar plot simplification in our corpus as Robyns (Citation1990), who writes about French translations of a particular genre: Anglo-American detective novels published in the Série Noire between 1952 and 1972. He notes that ‘[…] the translators strive for a narrative structure devoid of ‘dead’ or ‘wild’ branches, in which every single action contributes to the development of the intrigue (Robyns, Citation1990, p. 29)’. In the Crusoe corpus, the shortening of the ultimate source text has been achieved by summarizing events, dialogues and descriptive passages (e.g., excerpts from Crusoe’s diary have been cut, Crusoe’s dialogues with Friday are shorter, the trip to Lisbon and back to England through the mainland that Crusoe makes with Friday at the end of the novel has been completely omitted). However, the plot structure is the same as in , except for the ending and alleviation of function A1, which concerns Crusoe’s backstory and is less central for the core plot structure than function A2 (the shipwreck) and I1 (leaving the island). The two mediating texts and the ultimate target text only acknowledge that Crusoe’s parents are dead. No other family members are mentioned. In the last two paragraphs, there is a short description of Robinson’s and Friday’s life after their return to England. The three versions then stress Robinson’s relationship to Friday, whereas the ultimate source text depicts Robinson’s reunion with his family. However, since the core structure of the plot is the same in all four texts and the themes have remained the same in the translations, it could be claimed that the ‘essence’ of Robinson Crusoe has been altered surprisingly little, in terms of plot, in the long chain of indirect translation.

Table 1. The plot structure of the ultimate source text of Robinson Crusoe.

4.2. Peter Pan

Peter Pan (Barrie, Citation1911/2007) is a story about both the Darling family's life in England and the Darling children’s adventures in Neverland with Peter Pan. At the beginning of the novel, Mrs Darling learns that her children have been dreaming about a boy named Peter Pan. Shortly after, Peter Pan visits the nursery and persuades the children to leave for Neverland with him. Upon their arrival, Peter is reunited with the lost boys, children brought to Neverland by fairies. The children experience various adventures. The pirates’ leader Captain Hook kidnaps the children with his crew. Peter Pan comes to the children’s rescue, and a fight ensues between the children and the pirates. The children are victorious and travel home with the pirate ship. Back at home, the children are reunited with Mr and Mrs Darling, who also adopt the lost boys. Peter Pan, who does not want to grow up, leaves for Neverland.

The key points of the plot can be depicted as follows:

The story starts with an equilibrium: Wendy, John and Michael live with their parents. This equilibrium is disrupted when they fly away with Peter Pan (A). After some adventures in Neverland, Peter raises doubts about whether Mrs and Mr Darling are really waiting for their children to come back. This prompts John and Michael to cry ‘Wendy, let us go home!’ (Barrie, Citation2006, p. 137) (B). Wendy makes the decision to restore the equilibrium by going back home (C) and asks Peter Pan to make the necessary arrangements for the journey (function C’). By making these arrangements Peter empowers Wendy to go home (F1). Later, the children acquire the pirate ship Jolly Roger, which also empowers them to travel home (F2). After the trip back home (H) the children are reunited with their parents and the equilibrium is restored (I).

In addition to the plotline described above, there are several plot lines located entirely in Neverland. As the narrator describes (Barrie, Citation2006, pp. 96–98), the children are involved with an unspecified number of adventures that involve disrupting and restoring the equilibrium (the children living peacefully in their home in Neverland). In regard to the core structure of the plot, the pirates kidnapping the children and the subsequent fight in the pirate ship is the most crucial one, because it permanently resolves the imbalance between the children and the pirates in Neverland. Pirates kidnapping the children can be regarded as function ‘a’, which reveals the imbalance in Neverland: the pirates and the children are no longer able to coexist on the island. Peter decides to rescue the children (C), and his initial act to achieve his goal is to track down the pirates (C’). Peter arrives at the Jolly Roger (G) and fights the pirates with the children’s assistance (H). Peter and the children win the battle and thus restore the equilibrium: Hook and most of the pirates are no longer a threat to them (I). O’Connor’s (Citation1914/2012) and Byron’s (Citation1915/1976) adaptations and the three editions of Tuulio’s translation (1922, 1954 & 2006) all follow plot functions depicted in : the core structure stays the same in all versions. Despite the main plotline remaining unaltered, the adaptations and translations differ from each other somewhat in terms of plot. The greatest differences are between the adaptations and the ultimate source text, but there are also some differences between the adaptations and their respective translations. The plot of the Finnish versions (1922, 1954 & 2006) closely resembles that of the adaptations, which makes us presume that the adaptations were the primary source texts (see Ivaska, Citation2020, p. 30) of all three Finnish versions, but there are some minor differences where the translations follow the ultimate source text instead of the adaptation. A good example of this is the passage where Peter and Wendy are stranded on a rock and Michael’s kite floats by, and Wendy is tied to it and sent home. The reason why Peter cannot join him (Peter knows that the kite cannot sustain the weight of two) is explained in the ultimate source text (Barrie, Citation2006, p. 115) but is left out in O’Connor’s adaptation. The 1922 translation follows the ultimate source text and includes the explanation. The 1954 and 2006 editions also contain passages that follow the ultimate source text rather than the adaption: for example, the dialogue between the children after arriving home is much longer than in Byron’s (Citation1915/1976) version and is clearly translated from the original.

Table 2. The plot structure of the ultimate source text of Peter Pan.

Both O’Connor’s adaptation and Tuulio 1922 are only one third of the length of the original novel. In large part, this is due to summarizing the events and omitting descriptive passages (such as the contents of chapter 7 of Barrie’s original, which describes the children living in their underground home) and shortening dialogues between characters. Byron’s adaptation (1976) and the 1954 & 2006 editions of Tuulio’s translation resemble the ultimate source text more closely, but the events are summarized and some descriptive passages, such as representation of Hook's thoughts after capturing the children, are omitted. All adaptations and Finnish editions omit some events entirely. For example, in chapter 1, the backstory of the Darling family (Mr and Mrs Darling getting married and their children being born) is mostly left out and replaced by a brief description of the family. This corresponds to findings of Robyns (Citation1990, p. 30), who notes that in the French translations of Série Noire the passages describing the characters’ past are often either omitted or summarized. He concludes that ‘[…] in […] Série Noire’s narrative model, characters are less important than pure action, in which the character is merely the agent and as a function of which he is presented (Robyns, Citation1990, p. 31)’. Similarly, Paloposki (Citation2010, p. 43) observes omissions of textual passages that shed light on the personality of characters in her research on the translations of Les Misérables into Finnish. Such is the case also with adaptations and translations of Peter Pan: in addition to the summarizing of the Darlings’ backstory, the passages about the children growing up and Wendy’s daughter meeting Peter Pan are omitted.

If some of the alterations in the adaptations and the three Finnish versions do not seem to have a clear motivation, others can be characterized as ideological in nature, such as toning down the allusions to sexuality. As Yuan (Citation2020, p. 65) describes, while Peter Pan tells an adventure story, it explores the theme of eternal childhood which is developed through confrontations with the protagonists’ sexuality. This double messaging to child and adult audiences comes through primarily in descriptive passages, but also through some events. As Yuan (Citation2020, pp. 72, 76–77) points out, throughout the novel, Wendy is frustrated because she is not able to communicate adult feelings such as romance with Peter. For example, in the ultimate source text a discussion concerning romance between Peter and Wendy takes place. Wendy is disappointed when she hears that Peter thinks of her as his mother, and Peter does not understand why. In both adaptations and the three Finnish versions, this passage has been deleted, and thus the adult messaging through subtext is diluted. Another example is the censoring of violence. For example, in the ultimate source text’s depiction of the fight in the Jolly Roger, Peter and the children kill many of the pirates by stabbing them (Barrie, Citation2006, p. 184). In O’Connor’s version (2012, chapter 5) and Tuulio’s 1922 translation (chapter 5), the boys drive the pirates into the sea where they drown, and mentions about them striking the pirates with swords are removed. Byron's version states that ‘They [pirates] were killed and thrown overboard’. The 1954 edition (Tuulio/[Makkonen?]) replaces a direct mention of killing with pirates jumping into the sea. In the 2006 (Tuulio/Martin) edition, the wording has been changed back to killing.

In the adaptations and the three editions of Tuulio’s translation, the depiction of the storyworld is reduced because of the omission of descriptive passages. The thematics of the work is also altered due to the leaving out of passages pertaining to romance. It can be concluded that there are more changes in the translation chain of Peter Pan compared to that of Robinson Crusoe. Despite these changes in Peter Pan, the plot functions stay the same in all versions. For example, in the fight on the Jolly Roger, the result of the fight is the same although details have been changed. The conflict between the children and the pirates is resolved and thus the function of the event to the plot remains unchanged. Similarly, while omitting or softening the sexual allusions affects the thematic exploration aimed at adult audiences, it does not affect the advancement of the plot.

Conclusion

This study has shown that most of the essential plot functions of the texts studied had been preserved in the various versions of Robinson Crusoe and Peter Pan, whereas the events that can be characterized as descriptive were not present in all versions or had been altered. In that sense, our study corroborates Robyns’s (Citation1990) findings, which however did not concern indirect translation.

What remains of a work after it has been compressed to a shorter intra- or interlingual version? We suggest that this is strongly affected by genre expectations. Both Robinson Crusoe and Peter Pan can be characterized as adventure novels. A suspenseful plot is a key feature of adventure novels (Hosianluoma, Citation2003, p. 830), which are typically structured around various actions experienced by the protagonists in their journey outside the course of their ordinary life (D’Amassa, Citation2009, p. vii–viii). Both Robinson Crusoe and Peter Pan fit this definition well, and the intra- and interlingual translations of both works in our corpus have accentuated their plot-oriented nature: the core structure of the plot had remained unaltered while many passages such as descriptions of the storyworld, characters’ backstories and dialogues between characters had been shortened or omitted entirely. Thus, it seems that the adaptors, translators and editors have had a perception of what is essential for an adventure novel, a perception that prioritizes a clear and easy-to-follow plot.

Peter Pan is not only adventure fiction but also children’s literature, which might further increase the probability of highlighting the main plotline and removing passages not connected to the plot from the book’s adaptations and translations. Children’s literature has traditionally been regarded as plot-oriented (see Nikolajeva, Citation2002, p. 18). A tendency to plot-orientedness at the expense of other textual features was also observed by Leden (Citation2021, p. 279) in the Finnish and Swedish translations of children’s literature aimed at girls in the mid-1900s. Leden (Citation2021, p. 279) calls this process ‘narrative simplification’: in her corpus the descriptions of storyworld and characters as well as minor events were often shortened or omitted, while events of the main plotline were typically left unaltered (Leden, Citation2021, pp. 272–277).

Our results indicate that the process of indirect translation does not necessarily involve loss of essential plot points even in exceptionally long translation chains where several agents contribute to the makeup of the ultimate target text. It all depends on the aims and translation/editing strategies of these agents. In the translation chain of Robinson Crusoe, the greatest dissimilarities can be observed between the ultimate source text and the three translated versions, whereas a strong resemblance can be witnessed between the latter; the Swedish and Finnish versions seem to have been translated quite literally. In the case of Peter Pan, the greatest shifts from the ultimate source text appear in the mediating texts – Byron’s and O’Connor’s adaptations – and not in the subsequent Finnish translations. This corroborates Spirk's (Citation2014, p. 127, 167) findings concerning the indirect Portuguese translation of Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk. He found that most changes to the ultimate source text originated in the mediating text and that the ultimate target text did not introduce nearly as many shifts. Similarly, while Byron’s and O’Connor’s adaptations entail significant shifts with regard to the ultimate source text, the Finnish translations are quite faithful to these adaptations and do not introduce nearly as many changes. It can be concluded that the number of participating agents in indirect translation does not necessarily indicate a phenomenon of ‘Chinese whispers’. On the contrary, as Ivaska (Citation2020, p. 33) points out, in the context of indirect translation ‘collaboration can be seen as a strategy devised to minimize the number of deviations that translating indirectly has been claimed to cause […]’. In this study, Martin’s actions as the editor of the 2006 edition of Tuulio’s translation indicates such motivations, especially since she attached an editor’s note to the translation.

While our findings show that the plot functions remained in the varying intra- and interlingual translations of Peter Pan and Robinson Crusoe, altering the core structure of the plot in translation is not unheard of as Robyns (Citation1990, p. 40) Footnote13 also points out (see, e.g., the French ‘imitation’ of Aphra Behn’s (Citation1745/2008) Oroonoko by La Place, where the translator has turned the tragic unfolding to a happy ending). The conditions under which plot alterations do or do not occur require further investigation. Clearly, they cannot be explained by the nature of the translation process alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tuuli Hongisto

Tuuli Hongisto is a PhD student majoring in translation studies at the University of Turku. She graduated from the University of Helsinki in 2020 with comparative literature as her major (thesis topic: ‘Essential narrative features in story generating algorithms'). The working title of her PhD thesis is 'Literary stylistic features in story generating algorithms and machine translation'.

Kristiina Taivalkoski-Shilov

Kristiina Taivalkoski-Shilov is a Full Professor of Multilingual Translation Studies and Vice Head of the School of Languages and Translation Studies at the University of Turku, Finland. Prior to that she was employed by the University of Helsinki and has the title of Docent (i.e. Adjunct Professor) at the University of Helsinki (2013-). Taivalkoski-Shilov was a member of the Nordic research group ‘Voices of Translation: Rewriting Literary Texts in a Scandinavian Context' (2013-2016) and she has published articles on translation history and on the concept of 'voice' in translation.

Notes

1 We understand sameness as ‘The quality of being the same; = identity’ (OED online, s.v. ‘sameness’).

2 By this notion we mean ‘[t]he state or fact of being similar in some way; likeness, resemblance’ (OED online, s.v. ‘similarity’).

3 In his preface, Geyger (Citation1841, iii–iv) mentions that there are other German adaptations of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Therefore, it is possible that he has used one or several of them as secondary source texts.

4 Alice Martin is a literary translator and an editor for fiction translated into Finnish at WSOY Publishers (375 Humanists, Citationn.d.).

5 Inka Makkonen (1909-2008) worked for WSOY Publishers for more than thirty years. In 1952–1972 she was the publishing manager of children's literature (Karjalainen, Citation2008). Martin (Citation2006, p. 127) suspects that Makkonen revised the 1954 edition.

6 Within Translation Studies, adaptations can be defined as intra-, interlingual or intersemiotic reworkings of a text that can still be recognised as the work of the original author. The distinctive feature of adaptation is tailoring the text for a particular audience (Milton, Citation2010). Hutcheon (2013, 3, 6) notes that adaptations have a double nature: they have an overt defining relationship to prior texts but can also be valued and interpreted as autonomous works.

7 Chesterman’s types of sameness might recall some classifications of types of equivalence. However, since equivalence is a much fuzzier notion than sameness in contemporary Translation Studies, we do not use the notion of equivalence.

8 It goes without saying that semantic sameness is not always possible in translation, owing to fundamental differences between the source and target cultures.

9 Punctuation marks in the quoted section have been altered slightly for clarity.

10 Function ‘a’ refers to the re-evaluation that reveals instability (as opposed to function A which refers to a destabilizing event).

11 The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (Citation1719).

12 For example, unlike the ultimate source text, the German, Swedish, and Finnish versions are divided into (the same number of) chapters with the same kind of headings. They are also in third-person narration as opposed to the ultimate source text, which is in first-person narration.

13 In the cases Robyns (Citation1990, p. 40) mentions (Série Noire translations and 17th and 18th-century French translations of picaresque novels), the alterations to the plot are made due to genre expectations. Robyns (Citation1990, p. 24) sees the translations of Série Noire as a continuation of the belles infidèles tradition.

References

Primary sources

- Robinson Crusoe

- Defoe, D. (1841). Schicksale Robinson Crusoë’s von Daniel Foë. Nach dem Englischen dargestellt von A. Geyger [The fate of Robinson Crusoë by Daniel Foë. Adapted from the English by A. Geyger]. Trans. A. Geyger. Berlin: Hahn.

- Defoe, D. (1847). Robinson Crusoe’s besynnerliga öden. Bearbetade af A. Geyger efter D. Foe. Öfwersättning. Med Plancher [The strange fate of Robinson Crusoe. Adapted from D. Foe by A. Geyger. With illustrations]. Trans. Anonymous. Helsinki: Öhman.

- Defoe, D. (1847). Robinpoika Kruusen ihmeelliset elämänvaiheet. De Foen jälkeen mukailtu [The strange life of Robin’s son Kruuse. Adapted after De Foe.] Trans. Otto Tandefelt. Helsinki: Öhman.

- Defoe, D. (1719/2007). Robinson crusoe. In T. Keymer (Ed.), Oxford world’s classics. Oxford University Press.

- Peter Pan

- Barrie, J. M. (1911/2007). Peter pan. Oxford University Press.

- Barrie, J. M. (1922). Pekka Poikanen. Trans. Tyyni Tuulio.Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved January 12, 2021, from www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/48434

- Barrie, J. M. (1954). Peter Pan. Trans. Tyyni Tuulio. Kuopio: WSOY.

- Barrie, J. M. (2006). Peter Pan. Trans. Tyyni Tuulio. Porvoo: WSOY.

- Byron, M. (1915/1976). Peter Pan and Wendy. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Martin, A. (2006). Peter pan. WSOY.

- O’Connor, S. (1914/2012). The Story of Peter Pan. Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved January 12, 2021, from https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/39755

Other references

- Assis Rosa, A., Pięta, H., & Maia, R. B. (2017). Theoretical, methodological and terminological issues regarding indirect translation: An overview. Translation Studies, 10(2), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2017.1285247

- Bal, M. (1985/1997). Narratology: Introduction to the theory of narrative. University of Toronto Press.

- Behn, A. (1745/2008). Oronoko, l’esclave royal. Trans. Pierre-Antoine de La Place. Paris: Éditions La Bibliothèque.

- Chatman, S. (1978). Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film. Cornell University Press.

- Chesterman, A. (1997). Memes of translation: The spread of ideas in translation theory. John Benjamins.

- Chesterman, A. (2007). Similarity analysis and the translation profile. Belgian Journal of Linguistics, 21(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1075/bjl.21.05che

- D’Amassa, D. (2009). Encyclopedia of adventure fiction. Facts on File Library of World Literature, Infobase Publishing.

- Dannenberg, H. P. (2008). Coincidence and counterfactuality – plotting time and space in narrative fiction. University of Nebraska Press.

- Genette, G. (1993). Narrative Discourse. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Goethals, P. (2008). Between semiotic linguistics and narratology: Objective grounding and similarity in essayistic translation. Linguistica Antverpiensia, 7, 93–110. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v7i.210

- Greimas, A.-J. (1966/1983). Structural semantics: An attempt at a method. Trans. Danielle McDowell, Roland Schleifer, and Alan Velie. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Hadley, J. (2017). Indirect translation and discursive identity: Proposing the concatenation effect hypothesis. Translation Studies, 10(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2016.1273794

- Hosianluoma, Y. (2003). Kirjallisuuden sanakirja [Dictionary of literature]. WSOY.

- Ivaska, L. (2020). A Mixed-methods approach to indirect translation: A case study of the finnish translations of modern greek prose 1952–2004. PhD diss., University of Turku. Retrieved 21 December 2020, from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-8234-9

- Ivaska, L., & Paloposki, O. (2018). Attitudes towards indirect translation in Finland and translators’ strategies: Compilative and collaborative translation. Translation Studies, 11(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2017.1399819

- Kafalenos, E. (2006). Narrative causalities. Ohio State University Press cop.

- Karjalainen, M. (2008). “Inka Makkonen.” obituary at Helsingin Sanomat 20 January 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2021, from https://www.hs.fi/muistot/art-2000002624213.html

- Koskinen, K., & Paloposki, O. (2010/2016). Retranslation. In Y. Gambier, & L. v. Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies online. John Benjamins. https://benjamins.com/online/hts/articles/ret1

- Kukkonen, K. (2014). Plot. In P. Hühn, W. Schmid, & J. Schönert (Eds.), The living handbook of narratology. Hamburg. https://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de/node/115.html

- Leden, L. (2021). Adaption av flickskap [Adaptation of girlhood]. PhD diss., University of Helsinki.

- Merikallio, A. (2013). Untitled and unpublished research report (a comparative analysis of the Finnish and Swedish translations of Robinson Crusoe published by Öhmann in 1847).

- Milton, J. (2010). Adaptation. In Y. Gambier, & L. v. Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies online, vol. 1. John Benjamins. https://benjamins.com/online/hts/articles/ada1

- Mossop, B. (2017). Invariance orientation: Identifying an object for translation studies. Translation Studies, 10(3), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2016.1170629

- Nikolajeva, M. (2002). The rhetoric of character in children’s literature. Scarecrow Press.

- OED=Oxford English Dictionary. (online). s.v. similarity.

- Paloposki, O. (2010). Suomentaminen, korjailu, toimittaminen: Esimerkkinä Les Misérables -romaanin suomennokset. [translation, revising and editing: The Finnish translations of Les Misérables as a case in point]. AVAIN - Kirjallisuudentutkimuksen Aikakauslehti, 3(3), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.30665/av.74800

- Phelan, J. (1989). Reading people, Reading plots. University of Chicago Press.

- Propp, V. (1928/1968). Morphology of a folktale. Trans. Laurence Scott. University of Texas Press.

- Ringmar, M. (2007). Roundabout routes: Some remarks on indirect translations. In F. Mus (Ed.), Selected papers of the CETRA research seminar in Translation Studies 2006 (pp. 1–17). Lund University Publications. Retrieved 8 January 2016, from https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/files/ringmar.pdf

- Ringmar, M. (2012). Relay translation. In Y. Gambier, & L. v. Doorslaer (Eds.), The Handbook of Translation Studies online, vol. 3. John Benjamins. https://benjamins.com/online/hts/articles/rel4

- Robyns, C. (1990). The normative model of twentieth century belles infidèles: Detective novels in French translation. Target, 2(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.2.1.03rob

- Ryan, M.-L. (1991). Possible worlds, artificial intelligence and narrative theory. Indiana University Press.

- Rybicki, J. (2006). Burrowing into translation: Character idiolects in henryk sienkiewicz’s trilogy and its Two English translations. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 21(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqh051

- Sagulin, M. (2010). Jälkiä ajan hiekassa: Kontekstuaalinen tutkimus Daniel Defoen Robinson Crusoen suomenkielisten adaptaatioiden aatteellisista ja kirjallisista traditioista sekä subjektikäsityksistä [Traces in the sand of time: A contextual study on the ideological and literary traditions of Finnish adaptations of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and the notions of subject in them]. PhD diss., University of Eastern Finland.

- Spirk, J. (2014). Censorship, indirect translations and Non-translation. Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

- Todorov, T. (1969). Structural analysis of narrative. NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 3(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/1345003

- Tomashevsky, B. (1965). Thematics. In L. T. Lemon, & M. J. Reis (Eds.), Russian formalist criticism, four essays (pp. 61–95). University of Nebraska Press.

- Tymozcko, M. (2004). Difference in similarity. In S. Arduini, & R. Hodgson Jr (Eds.), Similarity and difference in translation: Proceedings of the international conference on similarity and translation (pp. 27–43). Guaraldi.

- Zuschlag, K. (2016). Analyse structurale du récit: “narratologie” et traduction. In J. Albrecht, & R. Métrich (Eds.), Manuel de traductologie (pp. 550–572). De Gruyter.

- Winqvist, M. (1973). Den engelske Robinson Crusoes sällsamma öden och äventyr genom svenska språket [The strange fate and adventures of the English Robinson Crusoe through the Swedish language]. Bonnier.

- Yuan, M. (2020). The translation of sex-related content in PeterPan in China. Translation Studies, 13(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2019.1604256

- 375 Humanists. (n.d.). 375 Humanists=“Alice Martin”, University of Helsinki, Retrieved 26 April 2021, from https://375humanistia.helsinki.fi/en/humanists/alice-martin