ABSTRACT

This study aims to adopt existing methodologies to build a Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL)-based multimodal analytical framework capable of analysing swearing and its subtitling in their full multimodal context. The proposed framework offers tools to investigate how the communicative meanings of swearing are constructed through the interaction between different elements in different modes, and the effects of the retention and modification of the intermodal relations on subtitled films. This study finds that swearing is constructed multimodally through three metafunctional levels. Although the original swearwords are mostly omitted or changed to be less offensive in the Chinese subtitles, most communicative meanings of swearing can be inferred from the complementary relation between subtitles and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes. The study concludes that the focus of subtitle translation analysis should not be on what is lost in the target texts but on the contributions of different elements in different modes and their intermodal relations as well as how individual translation techniques work in a multimodal environment.

1. Introduction

Swearing has been extensively discussed in the area of audiovisual translation (AVT) (Abdelaal & Al Sarhani, Citation2021; Abu-Rayyash et al., Citation2023; Al-Zgoul & Al-Salman, Citation2022; Ávila-Cabrera, Citation2015, Citation2016; Baines, Citation2015; Díaz-Pérez, Citation2020; Greenall, Citation2011; Han & Wang, Citation2014; Pardo, Citation2015; Pavesi & Zamora, Citation2022; Wu, Citation2021). While the term swearing is often used interchangeably with offensive, obscene, and taboo language, in this study, it refers to the non-literal use of taboo words primarily for expressive purposes, as defined by Ljung (Citation2011). In genres such as action crime films, swearwords often play a crucial role in constructing film narratives and characters (Filmer, Citation2014). In feature films, swearing serves three primary communicative functions: expressing positive emotions (e.g. happiness and joy) and negative emotions (e.g. anger and frustration), characterisation (e.g. representing the identity or personality of certain characters such as gangsters, drug-dealers, criminals or murders), and creating humour (Fernández Dobao, Citation2006; Pardo, Citation2015).

Existing studies on the subtitling of swearwords focus primarily on the spoken and subtitle modes,Footnote1 while ignoring the elements in other modes and the impact of translation techniques on intermodal relations and the communicative meanings they fulfil. This might be due to the lack of an analytical framework capable of accounting for various elements in different modes in constructing the communicative meanings of swearing in audiovisual texts. To address this gap, this study adopts existing methodologies to build a multimodal analytical framework capable of analysing swearing and its subtitling in their full multimodal context, with a focus on Chinese subtitling of six English-language films, including Bad Boys (1995), Enemy of the State (1998), Miami Vice (2006), Wanted (2008), Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014), and Criminal (2016). To the best of the author’s knowledge, no study has yet been conducted on the subtitling of swearwords using a multimodal framework. Moreover, research on Chinese subtitling of swearing is still limited, as most studies have focused on European languages and contexts. Additionally, subtitle translation may pose more challenges between culturally-distant contexts (e.g. Chinese and English) than within European contexts.

Drawing on existing approaches, this study proposes a Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL)-based multimodal framework to investigate how the communicative meanings of swearing are constructed through the interaction between different elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modesFootnote2 (Ramos Pinto, Citation2018). It also aims to explore whether these intermodal relations in the original film remain the same or change in the corresponding subtitled film. Futhermore, this study analyses the effects of the retention and modification of intermodal relations on subtitled films, particularly on the role of different modes in audiovisual texts.

2. Previous studies on the subtitling of swearwords

Existing literature on the translation of swearing in audiovisual texts has primarily focused on linguistic transfer, with less attention given to the role of intermodal relations and their contribution to the construction of communicative meanings. For example, Ávila-Cabrera’s (Citation2015) analysis of the translation of offensive and taboo language in Pulp Fiction (1994) from English into Spanish suggests that the omission and neutralisation of taboo words in subtitles can result in a loss of communicative meanings, such as the expression of emotions and the portrayal of characters’ personalities. However, this analysis does not take into account the elements in other modes, such as sound, facial expressions, and body language, and their contribution to conveying similar communicative meanings to swearing. In a corpus-based study of the reality TV series The Family, Han and Wang (Citation2014) draw upon relevance theory and functional equivalence to suggest that omitting or substituting English swearwords in the Chinese subtitles may not affect the communicative goal, as the target audience can infer the meaning from other linguistic elements in subtitles, such as negative words and expressions. However, as the current study shows, the construction of communicative meanings of swearing in subtitled films is not limited to linguistic elements alone. There are also cases when the target audience can infer the communicative meanings identified in the source texts (STs) through modes other than the subtitle mode. This happens, for instance, when the elements in the mise- en-scène mode express a similar meaning to the meaning expressed in the spoken mode.

Some studies do touch upon the role of other elements in different modes in the construction of the communicative meanings of swearing in subtitled films beyond linguistically-focused research. Greenall (Citation2011) highlights the importance of the original soundtrack in subtitled films, which is considered one of the factors for the substantial omission of the original swearwords in Norwegian subtitles. She suggests that the target audience’s English competence plays a main role in translators’ decisions, as most Norwegian audiences can recover the swearwords from the original soundtrack even if they are omitted in subtitles. Although this finding heavily relies on the target audience’s mastery of the source language, her study draws scholars’ attention to modes other than the subtitle mode that the target audience can draw on for meaning-making in subtitled films.

So far, the most relevant and illuminating study for analysing swearing in subtitled films is Baines’s (Citation2015) article on the subtitling of taboo language in three French- English/English-French films. Focusing on the film genre of social realism, Baines suggests that there are linguistic and visual cues embedded in the genre that trigger audiences’ expectations of the representation of swearwords. He argues that the partial omission of swearwords in subtitled films, especially in the genre of social realism, is not necessarily detrimental to characterisation (e.g. depicting low socio-economic groups). Many other elements in films, such as the visual (e.g. the setting and atmosphere), the use of non-standard language in character’s speech, and the use of swearwords elsewhere in the subtitles, are enough to set up audience’s perceived expectation of the register of character’s speech and their social backgrounds. In this case, ‘transferring all the taboo language to the subtitles is unnecessary’, either for reasons of politeness restrictions or time and space constraints (Citation2015, p. 442). However, as I will demonstrate in the data analysis, the crucial role of these elements in different modes in constructing the communicative meanings of swearing is not limited to the genre of social realism, but also applies to other genres such as action crime films. In addition, the current study differs from Baines’s (Citation2015) study since his research lacks a systematic and strong multimodal framework. Therefore, the elements he focuses on seem to be very general and randomly selected, rather than specific and systematically identified, in a way which allows for quantitative analysis or a more general overview. Furthermore, Baines only addresses the contribution of separate modes, without considering their intermodal relations to the construction of meaning in subtitled films.

Although the abovementioned studies have touched upon the role of different elements in different modes and acknowledged their importance in constructing the communicative meanings of swearing in subtitled films, the analysis of their interplay, specifically the intermodal relations, has not been integrated into a system. Therefore, the impact of translation techniques on intermodal relations and the communicative meanings they achieve in subtitled films has not been thoroughly addressed. I argue that it is essential to develop a multimodal framework to analyse the subtitling of swearing, since swearing is a type of communication that always involves various elements such as facial expressions and body language that interact with speech to indicate the actual communicative meanings of swearwords and influence how they are interpreted (Jay, Citation1999; Ljung, Citation2011). These elements are primarily used to express the interpersonal meanings of swearing, which are crucial for the target audience to retrieve the original communicative meanings, especially if the swearword is omitted or euphemised in subtitled films.

3. The multimodal analytical framework

3.1. Theoretical background

Several attempts have been made to establish a multimodal framework for analysing AVT (Chaume, Citation2004; Mubenga, Citation2015; Pérez-González, Citation2014; Ramos Pinto, Citation2018; Ramos Pinto & Mubaraki, Citation2020). This section reviews multimodal frameworks previously used for AVT and explores the limitations of these approaches, thus providing context for the design of the analytical framework for swearing proposed in the current study.

Drawing on theoretical contributions from film studies and translation studies, Chaume (Citation2004) suggests using an integrated framework to analyse audiovisual texts from a translational perspective. The theoretical framework that he proposes considers all the signifying codes of cinematographic language (e.g. the linguistic, the paralinguistic, the musical and the special effects, the sound arrangement, iconographic, photographic, the planning, mobility, graphic and syntactic codes) and the potential impact of these codes on translation. Although the semiotic codes listed in Chaume’s model make researchers more sensitive to the full semiotic environment of AVT, his framework focuses on how individual signifying codes influence the translator’s choices during the translation process rather than how meanings are conveyed by various codes and the intermodal relations between them. Thus, questions remain, including how these codes interact to make meaning in audiovisual texts, how translation techniques impact intermodal relations, and what communicative meanings these intermodal relations achieve. Therefore, his framework is more practical than analytical and is best regarded as a guide or checklist for translators rather than an analytical framework for researchers.

Drawing on insights from Halliday’s (Citation1978, Citation1994) SFL and theories from studies of multimodality and pragmatics, Mubenga (Citation2015) proposes a Multimodal Pragmatic Analysis (MPA) framework for the study of subtitle translation. One characteristic of his approach is that it both retains the linguistics-based analysis of the original dialogue and subtitles, and conducts a semiotic analysis of how different modes work together to make meaning in the final translated product. This differs from Chaume’s (Citation2004) approach, as Mubenga (Citation2015) focuses on the final translated product rather than the translation process. Mubenga’s framework has three basic components – functional, semiotic and cognitive – and three metafunctional levels of analysis – ideational, interpersonal and textual. Each component is analysed on all the three metafunctional levels. The functional component of Mubenga’s approach is concerned with analysis of the original dialogue and subtitles in order to interpret semantic and syntactic shifts and then identify translation techniques. The semiotic component focuses on the analysis of different modes at each metafunctional level based on Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2006) visual grammar and van Leeuwen’s (Citation1999) theory of sound design. The cognitive component concerns how the translation of culturally-specific references relates to the wider sociocultural context. Mubenga (Citation2015) explains that since his analytical subject is film, he prioritises the semiotic component in his framework.

However, despite their valuable contributions, the above approaches only list the individual modes which one must consider. To provide researchers with a systematic and effective tool for identifying the intermodal relations between modes in audiovisual texts, Pérez-González (Citation2014) develops a typology of modes in audiovisual texts based on Stöckl (Citation2004), who modelled multimodality as a networked system of core modes and sub-modes. For the purpose of analysing audiovisual texts, Pérez-González (Citation2014, p. 192) simplifies Stöckl’s (Citation2004) model by identifying four core modes: language, image, sound and music. According to Pérez-González (Citation2014), each core mode consists of multiple sub-modes; the interplay between different sub-modes determines the overall meaning of a communicative event. However, Pérez-González’s model does not analyse the contributions of different types of intermodal relations to the construction of meaning. Failure to address the interactions between different modes may result in a superficial and incomplete understanding of the impact of translation techniques on audiovisual texts.

To fill this gap, Ramos Pinto (Citation2018) and Ramos Pinto and Mubaraki (Citation2020) propose a multimodal analytical framework for studying the subtitling of non-standard varieties. Building on the work of Pastra (Citation2008), Pérez-González (Citation2014) and Bordwell and Thompson (Citation2010), Ramos Pinto (Citation2018) and Ramos Pinto and Mubaraki (Citation2020) identify three modes: the speech mode, the mise-en-scène mode and the subtitle mode. The speech mode consists of two categories (i.e. accent and vocabulary/morphosyntax), and the mise-en-scène mode consists of three categories (i.e. setting, figure behaviour and costume and makeup) for analysing non-standard varieties. Two intermodal relations are included in Ramos Pinto’s (Citation2018, p. 24) framework: confirmation, which refers to a situation in which the meaning expressed by any one element assumes the same communicative meaning expressed by the other elements, and contradiction, which refers to a case in which the meaning expressed by one or more elements is not compliant with the communicative meaning expressed by the remaining elements. Ramos Pinto argues that these intermodal relations can achieve different communicative meanings and diegetic functions in the STs and TTs, such as establishing interpersonal relations, characterisation and authenticity. Although this framework enables identification of the different modes at play as well as their intermodal relations as they relate to the construction meaning, it is designed specifically for the analysis of non-standard varieties. Due to the unique nature of swearing, a new framework capable of analysing swearing is proposed in this study based on existing frameworks.

3.2. The SFL-informed multimodal framework

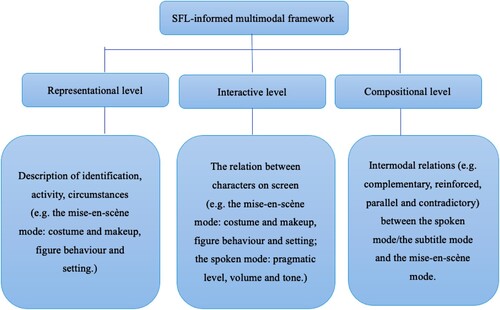

This study proposes a Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL)-informed multimodal framework capable of analysing swearing and its subtitling in their full multimodal context, as shown in . The framework uses the three metafunctions from Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2006) visual grammar as its theoretical foundation, which allows a systematic and comprehensive identification and classification of the different modes at play. I have also included Nikolajeva and Scott’s (Citation2000) classification of intermodal relations in the compositional metafunctional analysis, as it allows for the analysis of how the communicative meanings of swearing are conveyed through the interactions and intermodal relations between different modes.

The basic structure of the proposed theoretical framework is based on Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2006) visual grammar. Kress and van Leeuwen extend the metafunctional perspective of SFL to include visual images and rename the three metafunctions of SFL (ideational, interpersonal and textual) as representational, interactive and compositional; these are the three levels of analysis which make up the structure of my theoretical framework. However, Kress and van Leeuwen’s model is based on the analysis of modes in static images. To account for the dynamicity of film texts, I have also drawn on Bordwell and Thompson (Citation2010), Pérez-González (Citation2014) and Ramos Pinto (Citation2018) for the classification of modes in audiovisual texts. Thus, in this study, three modes are considered: the spoken mode, the mise-en-scène mode and the subtitle mode (only in subtitled films). The spoken mode consists of three elements: pragmatic level (the meaning of the utterance based on context), tone, and volume. The mise-en-scène mode consists of three elements: setting (objects such as props that function to depict space, place and time), figure behaviour (the expressions and movement of any figures) and costume and makeup (the clothing and attire of characters). These elements allow us to identify, for example, the location, the actions happening on-screen and the characters’ emotions and identities, which are significant for the meaning construction of swearing.

The selection of the elements for analysis in this study does not mean that other elements are not important or do not participate in meaning-making. There are many other elements in modes (e.g. camera shot, camera angle, size, lighting, colours) that contribute to the meaning-making of swearing, but one mode is often ‘made salient while others recede into the background’ in the construction of meaning in a given context (Stöckl, Citation2004, p. 15). The three modes chosen for this study are perceived as consistently more salient than other modes, based on the assumption that swearing fulfils specific communicative functions (e.g. characterisation and expressing emotions). Due to the time and space limitations of this study, the selected modes are considered in the quantitative analysis, while other elements are only touched upon when necessary. Thus, this study can be considered a first step; it is hoped that future studies will consider other elements in the meaning construction of swearing. The following sections introduce the analytical elements in each of the three metafunctional levels of the framework.

3.2.1. Representational level

The representational level of film concerns the portrayal of certain types of characters and surroundings, including the identification (who the social actors are), activity (what is taking place) and circumstances (where the action is taking place) (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006), which can be achieved through different elements in the mise-en-scène mode, including setting, figure behaviour and costume and makeup.

3.2.2. Interactive level

Analysis at the interactive level involves the interactive relations between different participants. According to Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2006, p. 48), there are two main types of participants in every communication: ‘the represented participants within the text and the interactive participants actually engaged with the act of communication’. In film, the former are the characters represented on-screen, which are the focus of this study, while the latter are the film and actual audiences, which only reception studies could give us more empirical evidence and thus are not discussed in this study. Different elements in different modes are considered when investigating the interactive relations between the characters on-screen. For instance, elements in the mise-en-scène mode, such as figure behaviour and costume and makeup, and elements in the spoken mode, such as volume and tone, play an important role in conveying interpersonal meanings in film, including establishing characterisation, conveying social status and expressing emotions (Bordwell & Thompson, Citation2010). Other elements proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2006), such as gaze (direct or indirect), social distance (e.g. camera shot) and point of view (e.g. camera angle) as well as colours, light and shade are also important for the construction of interactive meaning.

3.2.3. Compositional level

Analysis of subtitled films at the compositional level focuses on the intermodal relations between different elements in different modes when constructing meaning. In film, these elements do not simply co-exist but relate to each other in specific ways to make meaning. In this study, in the original films, the intermodal relations established between the elements in the spoken mode and mise-en-scène mode are considered, while in the corresponding subtitled films, the intermodal relations established between the subtitles mode, the spoken mode and the mise-en-scène mode are considered. Since subtitle translation involves the transfer of source spoken dialogue into target written text, the subtitles added to the TTs may retain or modify the intermodal relations established in the STs. The intermodal relations in both the original films and the corresponding subtitled films are considered when investigating the contribution of intermodal relations to the construction of meaning in both the STs and the TTs.

The classification of intermodal relations in this study uses the terms proposed by Nikolajeva and Scott (Citation2000), who provide a classification refined to account for the different types of relations between two or more elements in modes from a multimodal perspective. Four types of intermodal relations are considered in this study: complementary relation, parallel relation, reinforced relation and contradictory relation. Complementary relation refers to a type of intermodal relation in which the meanings expressed by one or more elements in modes provide additional information relevant to the other elements. In this case, viewers need to refer to all these elements to fully comprehend the communicative meanings. When elements in modes have a parallel relation, they do not combine to form a specific meaning; instead, the information that they provide is considered independent from other information in the given context. Reinforced relation refers to a type of intermodal relation in which the meanings expressed by one element convey more or less the same information expressed by one or more other elements. In other words, repeated information is conveyed through different elements in different modes, which can facilitate viewers’ comprehension since they express similar information. Lastly, in a contradictory relation, the meaning expressed by one element expresses information opposite to or incompatible with one or more elements; that is, one element expresses one thing while the other elements express the opposite.

To describe the ways in which different elements interact to make meaning and the impact of translation techniques on intermodal relations as well as on the multimodal whole, I also designed a multimodal transcription adapted from Taylor (Citation2016). The transcription, as shown in , is based on the multimodal framework previously discussed.

Table 1. The multimodal transcription.

Multimodal description, according to Taylor (Citation2016), is advantageous for investigating multimodal texts, as it shows the active involvement of different elements in the process of meaning-making and thus reflects how dispensable or indispensable any given element is in different situations. In other words, it can justify certain translation techniques since subtitles are viewed in terms of their interaction with other elements in film.

4. Method

4.1. Research data

This study focuses on the six Chinese subtitled action crime films, as shown in . These films are rated RFootnote3 due to the high levels of strong language and accompanying violence in the film. The six selected films cover both the use of a high (e.g. Bad Boys) and a low (e.g. Miami Vice) number of swearwords. It is believed that this selection, covering both extremes and average use of swearwords, can make the analysis of this study less biased and the results more generalisable.

Table 2. The selected films.

4.2. Analytical procedure

First, I analysed the transcribed English film dialogue of the selected films to identify and quantify the original English swearwords. The English transcripts were downloaded from the Internet Movie Screenplay Database (IMSDB) and then saved in Word files. The identification of swearwords in this study follows Ljung’s (Citation2011) definition, which includes stand-alones such as expletive interjections (e.g. Fuck!, God!), curses (e.g. Damn you!), unfriendly suggestions (e.g. Go to hell!), ritual insults (e.g. Your mother), and name-calling (e.g. asshole); slot-fillers such as adverbial intensifiers (e.g. bloody and damned), adjective intensifiers (e.g. fucking), and emphasis (e.g. What the fuck is this?); and idiomatic swearing such as fuck off and piss off. I counted each occurrence of a swearword as one token, even if the same type of swearword occurs multiple times in the film. For instance, in Enemy of the State (1998), the word fuck occurs 23 times, so it was counted as 23 tokens. For instances such as Shut the fuck up and Fuck you, I counted them as two tokens of swearwords in the analysis.

After identifying the samples from the original films, I then identified their corresponding Chinese translations by watching the subtitled films. Then, a comparative analysis was conducted between the original film dialogue and the Chinese subtitles to identify the translation techniques used and general patterns in terms of the subtitling of swearing. Lastly, a multimodal transcription based on the SFL-informed multimodal framework was used to describe how the communicative meanings of swearing are constructed through the three metafunctional levels. The impact of different translation techniques on the intermodal relations and the meanings they fulfil were also explored.

The data was analysed using a mixed-methods approach (McKim, Citation2017): quantitative analysis allows for general statements, including the identification of patterns in terms of the translation techniques used and the regularities of intermodal relations in meaning construction; qualitative analysis, on the other hand, focuses on specific cases, detailing how different elements in modes participate in meaning construction and the impact of translation techniques on intermodal relations and the multimodal whole.

5. Results

Han and Wang (Citation2014) propose four translation techniques for subtitling English swearwords into Chinese: semantic shift, which involves changing the semantic category,Footnote4 such as translating ‘Fuck’ (a semantic category of sex) into 他妈的 (his mother’s – a semantic category of mother); omission, which involves omitting the English swearword in the Chinese subtitles; de-swearing, which refers to the replacement of the original swearword with plain and non-swearwords, such as translating ‘What the fuck are you doing’ into 你究竟在干什么 (what on earth are you doing); and literal translation, which involves rendering the English swearword into Chinese swearwords in the same semantic category, such as translating fuck into 操 (fuck) in Chinese subtitles, as they both belong to the category of sex. However, after analysing the examples in my data, I have identified a fifth translation technique – functional shift, referring to a change in the function of swearwords as categorised by Ljung (Citation2011). For instance, Fuck! That hurt! is translated into 该死! 好疼! (Deserve to die! That hurt!), which involves a functional shift from an expletive interjection into a curse. Drawing on this classification of translation techniques, and show the distribution of each translation technique in the chosen films.

Table 3. The distribution of translation techniques.

shows that de-swearing and omission are the two most frequently used translation techniques, accounting for 41% and 29% respectively. Literal translation is the least used technique, accounting for only 3%. These findings indicate a strong tendency to tone down swearwords, with 70% of the original swearwords either omitted or de-sweared in the Chinese subtitles. When different translation techniques are employed, the intermodal relations in the STs may remain the same or change in the TTs. Due to space constraints, two examples ( and ) from the chosen films are shown to illustrate how the communicative meanings of swearing are constructed through the three metafunctional levels and the impact of translation techniques on the multimodal whole.

In this shot (), which takes place on the street, Marcus (played by Martin Lawrence), a detective in Miami, is kidnapped by two gangsters on his way home. The sudden kidnap makes Marcus furious, and he swears ‘Hold the fuck on!’ at the gangsters with a wide-open mouth. At the interactive level, the medium close-up highlights Marcus’s exaggerated figure behaviour, allowing the audience to see his mouth when he emphasises the word the fuck, which is reinforced by his loud, angry, and high-pitched voice. By using infixation, the word fuck in the ST emphasises the phrase hold on and expresses Marcus’ anger. These meanings are retained in the subtitled films through the complementary relation between the subtitle and the elements in the spoken (i.e. volume and tone) and mise-en-scène modes (i.e. figure behaviour) at the compositional level. The following shows another example:

This shot () takes place in a local pub where Eggsy (played by Taron Egerton) and Harry (played by Colin Firth) are having a conversation. They are interrupted by a gang of thugs led by Rottweiler (shown in the first screenshot), who is surprised to see Eggsy back at the pub since he had stolen their car the other day. At the interactive level, Rottweiler points his finger at Eggsy and interrogates him, saying ‘What are you doing here? You taking the piss?.’ According to Pease and Pease (Citation2004), pointing a finger at someone is a potent gesture of power and provocation, as it conveys the message ‘do it or else’. In this example, Rottweiler’s use of the gesture highlights his aggressive and dominant personality, and his dominant status among the thugs. This construction of this identity can also be inferred representationally: Rottweiler’s costume and make-up (e.g. hoodies and sportswear, bruises and scars on his face). The use of the swearwords taking a piss in the ST is for characterising the street thugs and conveying Rottweiler’s anger and surprise. These meanings are achieved through the reinforced relation between the spoken mode (i.e. pragmatic, tone and volume) and the mise-en-scène mode (i.e. figure behaviour, makeup and costume) at the compositional level. The same meanings are retained in the TT through the complementary relation between the subtitle and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes.

After analysing each instance of swearing in the six films, provides a summary of the percentage of each type of intermodal relations between the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes when constructing the communicative meanings of swearing in the STs. , on the other hand, shows the percentage of each type of intermodal relations between the subtitle mode and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the TTs.

Table 4. The intermodal relations between the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the STs.

Table 5. The intermodal relations between the subtitle mode and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the TTs.

As shown in , two types of intermodal relations are identified in the STs: reinforced and parallel. However, shows that three types of intermodal relations are identified in the TTs: complementary, parallel, and reinforced. One of the most noteworthy findings is that the reinforced relation between the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the STs is mostly changed into a complementary relation between the subtitle mode and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the TTs, in order to achieve the original communicative meanings such as expressing characters’ emotions and portray their identities. This occurs when the translation techniques of omission and de-swearing are employed, as the target audience may be able to retrieve the original meanings from the complementary relation between the subtitle mode and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes.

6. Discussion and conclusion

The data in this study show a strong tendency to tone down swearing in Chinese subtitling of English action crime films, which is consistent with previous studies that have identified a tendency to omit or change swearwords into non-swearwords when translating swearing in audiovisual texts, although the degree of toning-down varies slightly among different language pairs (Abdelaal & Al Sarhani, Citation2021; Abu-Rayyash et al., Citation2023; Ávila-Cabrera, Citation2015; Díaz-Pérez, Citation2020; Greenall, Citation2011; Han & Wang, Citation2014). Analysis of modes and intermodal relations using the SFL-informed multimodal framework shows that although most original swearwords are omitted or de-sweared in the Chinese subtitles, there is still room to communicate the original meanings in the TTs. The toning-down of swearwords does not necessitate complete loss of the original meanings because most communicative meanings of swearing can be inferred from the complementary relation between the subtitles and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes. This finding contradicts previous studies which argue that the toning-down of swearing in subtitled films is detrimental to understanding characters’ emotions and personalities (Ávila-Cabrera, Citation2015; Fernández Dobao, Citation2006; Han & Wang, Citation2014; Lung, Citation1998).

The first and most obvious finding that supports the above argument is that swearing is constructed multimodally through the three metafunctional levels (representational, interactive and compositional). In particular, my study shows that the communicative meanings of swearing are not constructed by film dialogue alone but by the intermodal relations between different elements in modes at the three metafunctional levels. In most cases (65%), in the STs,, the meaning expressed by figure behaviour reinforces the meaning expressed by the elements in the spoken mode (pragmatic level, tone and volume) to construct the communicative meaning of swearing, including expressing the characters’ emotions (). In 25% of cases, the meaning expressed by figure behaviour and costume and makeup reinforces the meaning expressed by the elements in the spoken mode to construct the communicative meanings of swearing, such as portraying the character’s identity or indicating a violent and aggressive atmosphere. In only 10% of cases does the setting reinforce the elements in the spoken mode to construct the communicative meanings of swearing. For instance, in the opening scene of Miami Vice (2006), the setting of a dark basement with graffiti and guns on the wall and the low lighting reinforce the aggressive and threatening atmosphere established by the elements in the spoken mode of José, the drug ring leader. In the most frequently used translation techniques of omission and de-swearing, the reinforced relation between one or more elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the STs does change the corresponding subtitled films at the compositional level in most cases. This happens because one or more elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes complement the subtitles and retain the original meaning. There are also cases in which the reinforced relation between one or more elements in the spoken and mise- en-scène modes in the STs remain as a reinforced relation between the subtitles and the elements in the spoken and mise-en-scène modes in the TTs. This usually happens when using the translation techniques of semantic shift, functional shift and literal translation.

Table 6. The omission of the fuck in Bad Boys (1995).

Table 7. The de-swearing of taking the piss in Kingsman (2014).

However, one cannot assume that the elements in the three metafunctional levels are always sufficient to retrieve the original meanings. There are also cases in which the elements in modes cannot compensate for the loss of swearing, such as the sudden shift of a character’s speech from his normal register (which is full of swearwords) into a formal register in Criminal (2016). The omission of the original swearwords in the subtitles removes the possibility of establishing a contrast between the character’s normal register and their sudden shift into a formal register. It should also be noted that there can be incongruence between the verbal expression of swearing and the emotions that it conveys. However, as seen in the examples discussed, this study primarily considers examples where these are congruent. This is perhaps due to the nature of the genre of action crime films, as the characters are meant to present themselves consistently in terms of behaviour, emotions and language. Film genres that are rich in parody or ironic humour might contain more incongruence of expression/emotion. In such instances, it may not be possible to replicate the findings of this study. As Ramos Pinto (Citation2018) suggests, it is also important to keep in mind that it depends on the target viewer’s ability to identify the different elements in modes and their familiarity with these elements, which can be tested in future audience reception studies. Therefore, I argue that the focus of subtitle translation analysis should not be on what is lost in the TTs but on the contributions of different elements in modes and their intermodal relations as well as how individual translation techniques work in a multimodal environment.

The multimodal analytical framework that this study proposes based on previous studies (Bordwell & Thompson, Citation2010; Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006; Nikolajeva & Scott, Citation2000; Pérez-González, Citation2014; Ramos Pinto, Citation2018; Ramos Pinto & Mubaraki, Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2016) is useful for analysing the subtitling of swearing. It enables the analysis of different elements in modes at the three metafunctional levels, particularly the way in which intermodal relations participate in the construction of meaning. It also allows investigation into the impact of different translation techniques on intermodal relations and allows researchers to determine to what extent the overall meaning in the STs differs from that in the TTs. In this way, this study answers the recent call for a multimodal analytical framework capable of enabling quantitative analysis of larger datasets of audiovisual products across genres that can produce generalisable results without overlooking the participation of intermodal relations in the construction of meaning (Adami & Ramos Pinto, Citation2020; Gambier & Ramos Pinto, Citation2018). The exploration of intermodal relations and the communicative meanings which they express produces a level of detail and nuance not found in previous studies on Chinese subtitling of swearing.

This study is one of the first attempts to integrate the SFL-informed multimodality into a theoretical framework for the analysis of subtitling swearing. This study moves research beyond the analysis of subtitled films based on the spoken and subtitle modes since these are only part of the multimodal ensemble of audiovisual texts. This translational shift will inevitably influence the overall construction of meaning at the three metafunctional levels as well as the target audience’s interpretation of the film. The multimodal framework that this study proposes and the data analysis based on it not only bridge a gap in research on the subtitling of swearing but also move traditional linguistically-focused research in this area in a more interdisciplinary, multimodally-informed direction. It contributes to the study of AVT research in general and the study of Chinese subtitling of English swearing more specifically. Although the framework is designed for the analysis of swearing, it is likely adaptable to other language pairs and translation issues (e.g. humour and culture references), an assumption which can be tested in future research. This study can form the basis of future studies on audience reception (e.g. questionnaires, interviews or eye-tracking experiments), which could provide empirical evidence for viewers’ interpretation and reception of different intermodal relations and translation techniques.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Siwen Lu

Dr Siwen Lu is currently a Lecturer in Translation Studies at University of Sheffield. She was a Visiting Post-Doc Researcher at University of Cambridge and University of Bristol before joining Sheffield. She completed her PhD in Translation Studies at University of Liverpool. Her research interests include audiovisual translation (e.g. subtitling, fansubbing, danmu subtitles), multimodality and digital media cultures. She has published several articles in peer-reviewed journals including Babel: International Journal of Translation, New Media & Society, Visual Communication, International Journal of Communication and Perspectives: Studies in Translation Theory and Practice. She is a member of The British Association for Chinese Studies (BACS) and European Association for Studies in Screen Translation (ESIST).

Notes

1 The term ‘mode’ in this study refers to those ‘sets of meaning-making resources that we intuitively fall back on’ in the production and consumption of audiovisual texts (Pérez-González, Citation2014, p. 192).

2 I follow the term used by Ramos Pinto (Citation2018), who defines ‘the mise-en-scène mode’ as the stage design and actors’ arrangement in scenes for film, including costume and makeup, figure behaviour and setting.

3 The rating is based on The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) film rating system.

4 Han and Wang (Citation2014) categorise English and Chinese swearwords into different semantic categories: the former includes body parts (arse), sex (fuck), mother (bastard), religion (god), and etc.; the latter includes sex (操 fuck), mother (他妈的 his mother’s), death (死人 dead man), and etc.

References

- Abdelaal, N. M., & Al Sarhani, A. (2021). Subtitling strategies of swear words and taboo expressions in the movie “training Day”. Heliyon, 7(7), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07351

- Abu-Rayyash, H., Haider, A. S., & Al-Adwan, A. (2023). Strategies of translating swear words into Arabic: A case study of a parallel corpus of Netflix English-Arabic movie subtitles. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(39), 1–13.

- Adami, E., & Ramos Pinto, S. (2020). Meaning-(re) making in a world of untranslated signs: Towards a research agenda on multimodality, culture, and translation. In M. Boria, Á Carreres, M. Noriega-Sánchez, & M. Tomalin (Eds.), Translation and multimodality: Beyond words (pp. 77–91). Routledge.

- Al-Zgoul, O., & Al-Salman, S. (2022). Fansubbers’ subtitling strategies of swear words from English into Arabic in the Bad boys movies. Open Cultural Studies, 6(1), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2022-0156

- Ávila-Cabrera, J. J. (2015). Subtitling Tarantino’s offensive and taboo dialogue exchanges into European Spanish: The case of pulp fiction. Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4995/rlyla.2015.3419

- Ávila-Cabrera, J. J. (2016). The subtitling of offensive and taboo language into spanish of inglourious basterds. Babel, 62(2), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.62.2.03avi

- Baines, R. (2015). Subtitling taboo language: Using the cues of register and genre to affect audience experience? Meta, 60(3), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036137ar

- Bordwell, D., & Thompson, K. (2010). Film Art: An introduction (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Chaume, F. (2004). Film studies and translation studies: Two disciplines at stake in audiovisual translation. Meta, 49(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.7202/009016ar

- Díaz-Pérez, F. J. (2020). Translating swear words from English into galician in film subtitles: A corpus-based study. Babel, 66(3), 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00162.dia

- Fernández Dobao, A. M. (2006). Linguistic and cultural aspects of the translation of swearing: The spanish version of pulp fiction. Babel, 52(3), 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.52.3.02fer

- Filmer, D. (2014). “The ‘gook’ goes ‘gay’. Cultural interference in translating offensive language”. Intralinea 15. www.intralinea.org/archive/article/the_gook_goes_gay

- Gambier, Y., & Ramos Pinto, S. (2018). Audiovisual translation: Theoretical and methodological challenges. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Greenall, A. K. (2011). The non-translation of swearing in subtitling: Loss of social implicature? In A. Serban, A. Matamala, & J. M. Lavour (Eds.), Audiovisual translation in Close-Up: Practical and theoretical approaches (pp. 45–60). Peter Lang.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold.

- Han, C., & Wang, K. (2014). Subtitling swearwords in reality TV series from English into Chinese: A corpus-based study of The family. Translation and Interpreting, 6(2), 1–17.

- Jay, T. (1999). Why We curse: A neuro-psycho-social theory of speech. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Ljung, M. (2011). Swearing: A cross-cultural linguistic study. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lung, R. (1998). On mis-translating sexually suggestive elements in English-Chinese screen subtitling. Babel, 44(2), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.44.2.02lun

- McKim, C. A. (2017). The value of mixed methods research: A mixed methods study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815607096

- Mubenga, K. S. (2015). Film discourse and pragmatics in screen translation. LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Nikolajeva, M., & Scott, C. (2000). The dynamics of picturebook communication. Children’s Literature in Education, 31(4), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026426902123

- Pardo, B. S. (2015). On the translation of swearing into spanish: Quentin tarantino from reservoir dogs to inglourious basterds. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Pastra, K. (2008). COSMORE: A cross-media relations framework for modelling multimedia dialectics. Multimedia Systems, 14(5), 299–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00530-008-0142-0

- Pavesi, M., & Zamora, P. (2022). The reception of swearing in film dubbing: A cross-cultural case study. Perspectives: Studies in Translation Theory and Practice, 30(3), 382–398.

- Pease, A., & Pease, B. (2004). The definitive book of body language. Pease International.

- Pérez-González, L. (2014). Audiovisual translation: Theories, methods and issues. Routledge.

- Ramos Pinto, S. (2018). Film, dialects and subtitles: An analytical framework for the study of Non-standard varieties in subtitling. The Translator, 24(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2017.1338551

- Ramos Pinto, S., & Mubaraki, A. (2020). Multimodal corpus analysis of subtitling: The case of non-standard varieties. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 32(3), 389–419. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.18085.ram

- Stöckl, H. (2004). In between modes: Language and image in printed media. In E. Ventola, C. Charles, & M. Kaltenbacher (Eds.), Perspectives on multimodality (pp. 9–30). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Taylor, C. (2016). The multimodal approach in audiovisual translation. Target, 28(2), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.28.2.04tay

- Van Leeuwen, T. (1999). Speech, music, sound. Macmillan.

- Wu, S. (2021). Subtitling swear words from English into Chinese: A corpus-based study of big little lies. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 11(2), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2021.112022