ABSTRACT

This study examines multilevel factors shaping Indonesian student performances attending non-madrasah/sekolah and madrasah schools. Using multistratified sample design and grouped based on their school system, data from 30 schools, 64 teachers, and 1,319 students were analysed. Focusing on student, teacher, and school-level variables, hierarchical linear modelling revealed that reading difficulties and anxiety, along with school climates emphasizing achievement pressure and discipline, significantly influenced reading outcomes in both groups. Students grappling with heightened learning complexities and anxiety faced the greatest challenges. Interestingly, madrasah students thrived within competitive environments emphasizing high achievement pressure and minimal disciplinary constraints, while sekolah students who excelled in settings that valued discipline over relentless achievement pressure performed better. Unique influences emerged: peer relationships and anxiety directly affected reading scores in sekolah, while gender was the sole predictor in madrasah. Interaction effects among these multilevel factors in shaping student reading achievement across diverse educational settings were revealed.

Introduction

The effectiveness of the educational system in Indonesia is significantly influenced by the dichotomy between madrasah, which are Islamic schools managed by the Ministry of Religious Affairs (MoRA), and non-madrasah education. While the madrasah represents a formal Islamic education system, there are also other Islamic schools such as Maarif Islamic School, Muhammadiyah Islamic School, and Integrated Islamic School that, despite being Islamic, do not fall under the madrasah category. These schools are part of the broader non-madrasah education system. The non-madrasah or sekolah education is overseen by local governments, with the Ministry of Education and Culture (MoEC) providing guidance and regulatory frameworks. This dual structure, with distinct administrative bodies and types of schools, creates a unique dynamic that impacts the overall effectiveness and integration of educational policies and practices within the country. The data provided by the Directorate of Basic Education Data (Data Pokok Pendidikan, Citation2024) and the Educational Management Information System (EMIS, Citation2024) present a stark contrast in the distribution of public and private secondary educational institutions in Indonesia. According to these data, the MoEC oversees a total of 28,501 secondary schools (sekolah), of which 10,679 (approximately 37%) are public schools, while a significant majority, 17,822 (approximately 63%), are private. In contrast, the madrasahs, Islamic educational institutions managed by the MoRA, show an even more pronounced tilt towards private management. Out of the total 9,827 secondary madrasahs reported, a staggering 92% (9,017) are operated privately, and only a small fraction, 8% (810), are public. Simultaneously, the governance models of these institutions differ significantly; madrasahs are centrally managed by the central authority of MoRA, requiring strict adherence to central government policies and coordination, which might restrict their ability to quickly adapt to local educational needs. Conversely, non-madrasah schools benefit from a decentralized management approach by MoEC, allowing greater flexibility and responsiveness to local educational demands and conditions (Muttaqin et al., Citation2020).

This dichotomy not only influences the operational dynamics of these schools but also affects the overall effectiveness of the educational system in Indonesia, potentially impacting the quality of education and the ability of these institutions to meet the diverse needs of their students. Studies such as those by Hendajany (Citation2016) and Newhouse and Beegle (Citation2006) have indicated that students in madrasah schools, on average, perform less satisfactorily in terms of learning outcomes and language competencies compared to their counterparts in non-Islamic/madrasah schools. In this case, Stern and Smith (Citation2016) have further clarified the primary barrier to high-quality education in madrasah schools, identifying insufficient government funding as a major issue. Despite their predominantly private operation, madrasahs are restricted from regularly receiving funding from local governments due to government policies. While they can receive community funds, their financial support often relies on less predictable sources such as private donations and Islamic charitable organizations. This distinction contrasts with non-madrasah schools, which receive more consistent funding from local governments (Shaturaev, Citation2021). In contrast, non-madrasahs benefit from a decentralized management system as outlined by Muttaqin et al. (Citation2020), which allows greater autonomy in decision making, resource allocation, and educational planning. This decentralization enables non-madrasah or sekolah schools to tailor their educational programs to better fit the specific needs, conditions, and priorities of their communities and manage their resources more efficiently and effectively. Consequently, the financial constraints faced by madrasah schools can limit their capacity to provide the necessary resources and facilities for optimal learning outcomes, highlighting a significant disparity in educational equity across different types of Indonesian schools.

Furthermore, these challenges facing madrasah education in Indonesia are multifaceted, extending to both infrastructural and human resource domains, as elucidated by various studies. One prominent issue lies in the inadequate and substandard nature of school facilities within madrasah schools, encompassing classrooms, laboratories, and learning materials, as highlighted in comprehensive reports (Ali et al., Citation2011; Asian Development Bank [ADB], Citation2014; Ependi, Citation2020; Muhajir, Citation2016). This deficiency significantly hinders the teaching and learning processes, impacting the psychological wellbeing of both students and teachers. Compounding this challenge is the fact that the majority of madrasah teachers operate outside the civil servant system, receiving low wages directly from the school budget without the standardized salary support provided to their counterparts in other schools (ADB, Citation2014; Muhajir, Citation2016). Furthermore, a notable study by Ahid (Citation2010) has revealed that 28% of madrasah teachers lack undergraduate qualifications, and these educators face limited opportunities for participation in essential teacher training, certification, and professional development programs compared to their counterparts in the sekolah or schools under the MoEC (ADB, Citation2014; Kholis & Murwanti, Citation2019). Consequently, the prevalence of underpaid, untrained, and uncertified teachers in madrasah schools is a pervasive issue, directly influencing the efficacy of teaching practices and, consequently, the student’s academic performance, including language competencies.

While challenges persist in the realm of school resources in madrasah education, various studies have underscored the positive impact of religious values on school effectiveness, including school environment, teacher behaviours, and student needs within Islamic schools. Research findings have consistently indicated that Islamic values play a pivotal role in fostering an effective school climate, as evidenced by heightened school-community engagement (Na’imah et al., Citation2022), positive teacher attitudes (Yafiz et al., Citation2022), favourable student attitudes towards language learning (Amri et al., Citation2017; Tahir, Citation2015), and enhanced psychological outcomes (Na’imah et al., Citation2022). These aspects collectively contribute to creating an environment conducive to effective teaching and learning outcomes in madrasah schools. In line with findings from previous research, it becomes evident that both non-madrasah and madrasah schools wield distinct strengths that significantly impact teacher and student-level factors, thereby influencing various aspects of the educational landscape. Non-madrasah schools have been consistently noted for their substantial advantages in terms of school resources, encompassing facilities, materials, and infrastructure. Simultaneously, madrasah schools have been recognized for fostering positive school climates rooted in religious values. Although many madrasah students come from middle- and low-income socioeconomic backgrounds, their families often possess significant human, social, and cultural capital. For example, many students are children of highly respected community members, such as religious leaders, preachers, and clerics, who choose madrasahs for their rooted values and religious affiliations (Asadullah et al., Citation2015). These unique strengths, each characteristic of its educational paradigm, play a pivotal role in shaping teacher- and student-level factors. Teaching performance, teacher attitudes, student wellbeing, behaviours, and learning achievement are all intricately influenced by the distinct advantages that non-madrasah/sekolah and madrasah schools offer. This confluence of strengths underscores the multifaceted nature of the educational experience, highlighting the importance of considering both school resources and climates and teacher and student factors in understanding the nuanced dynamics of teaching and learning within these different educational contexts.

Despite this acknowledgement, there remains a dearth of comparative investigations delving into the factors influencing student language performance when contrasting non-madrasah and madrasah education in both global and local contexts. The present study aims to contribute valuable insights by exploring how school-, teacher-, and student-level factors may influence student performance (e.g., English reading competencies) across both schools differently. The research questions framed for this study seek to unravel the intricate dynamics influencing language proficiency in these educational settings, shedding light on the nuanced interplay between sekolah and madrasah approaches to education, as follows:

What are the differences in the direct effects of student-level factors (demographics, learning motivation, anxiety, difficulty, and wellbeing), teacher-level factors (professional attributes and development, professional attitudes, and teaching effectiveness), and school-level factors (demographics, resources, and climate) between non-madrasah/sekolah and madrasah schools on their students’ English reading achievement?

How do the tested school- and teacher-level factors in the sekolah and madrasah groups interact with the student-level factors and their English reading achievement differently?

What are the proportions of variance in students’ English reading performances in the sekolah and madrasah groups explained by the student-, teacher-, and school-level predictors?

To systematically address the research inquiries at hand, a meticulous comparative analysis was undertaken, distinctly examining Indonesian sekolah and madrasah schools. Employing statistical methods, particularly multilevel analysis, the study aimed to discern how specific factors contribute to direct effects and interactions influencing students’ English reading capabilities within these educational settings. The comprehensive set of variables encompassed school-related aspects such as demographics, characteristics, resources, and climate, scrutinizing the influence at the school level. Additionally, factors at the teacher level, including personal and professional attributes, professional development, job-related attitudes, and teaching effectiveness, were carefully considered. At the student level, demographic variables, along with measures of wellbeing, motivation, anxiety, and difficulty, were incorporated to provide a holistic understanding of the dynamics at play. To fortify the credibility of the study, a rigorous examination of the instrument’s validity and reliability was conducted, ensuring the integrity and quality of the reported findings. This methodological approach, blending statistical rigour and comprehensive factor inclusion, strengthens the robustness of the study’s findings and contributes to a nuanced comprehension of the multifaceted influences on students’ achievements in non-madrasah and madrasah educational settings.

Literature review

English reading achievement

In the 21st century, student performance, such as English reading literacy, has emerged as a foundational skill crucial for both economic growth and personal cognitive development. Extensive literature underscores its pivotal role in metalinguistic and critical thinking tasks, contributing to enhanced oral and written language competencies (Mart, Citation2012; Mermelstein, Citation2015) and superior critical thinking abilities (Duru & Koklu, Citation2011). Notably, individuals with strong English reading skills are more adept at securing employment, as these skills are perceived as indicative of superior communication abilities, including effective collaboration and negotiation with international counterparts (Araújo et al., Citation2015; Longweni & Kroon, Citation2018; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2021). Recognizing the global significance of English literacy, countries like Indonesia have adapted their curricula to align with the demands of a competitive global landscape (Isadaud et al., Citation2022; Pajarwati et al., Citation2021). Preparing the younger generation to be globally competitive is critically important, and mastery of the English language is a fundamental component of this preparation. English proficiency, including reading, not only enhances individual employability on the international stage but also equips students with the tools necessary to engage in global discourse, fostering broader perspectives and deeper understanding. The widespread recognition of the multifaceted benefits of English reading has heightened interest in understanding the factors influencing students’ achievement in this skill across diverse school contexts and countries. Consequently, the quest to comprehend these influences has become paramount, reflecting the growing acknowledgement of English reading literacy as an essential skill with far-reaching implications for individuals and countries alike.

Student-level factors

Student demographics

The exploration of the complex interplay between student demographics and academic success in English reading has generated significant scholarly discussion across various educational environments. A particular emphasis has been placed on gender disparities, with research, such as the studies by Mirizon et al. (Citation2018) and Rianto (Citation2021), conducted in global school settings consistently revealing a gender gap where male students often lag behind their female counterparts in English reading performance. This trend is notably pronounced in a specific educational setting, such as Islamic school contexts, where studies by Ali et al. (Citation2011) and Murtafi’ah and Putro (Citation2020) further demonstrate that boys not only show lower motivation but also achieve lower scores in English proficiency. Additionally, age-related differences in English reading achievement have been identified, presenting a mixed picture. For instance, Bećirović and Hurić-Bećirović (Citation2017) found that 10-year-old students in Bosnia and Herzegovina excel in English reading compared to their older peers, while Gawi (Citation2012) reports an opposite trend in younger students in Islamic schools who perform worse. Despite the abundance of data, there is a clear gap in the literature that integrates these disparate findings into a cohesive understanding of how various student attributes affect English reading outcomes in different school contexts. Such comprehensive comparative research is necessary to develop targeted educational strategies that can effectively address these demographic-related disparities in student language performance.

Student wellbeing

While there is no single, universally accepted definition of wellbeing, its complex nature is widely recognized, especially within educational contexts. Wellbeing is generally understood as a state of life quality where psychological, social, and physical aspects are in harmony, enhancing academic performance. This understanding, though varied in its specifics, resonates across much of the scholarly literature, including works by Seligman (Citation2018) and Zajenkowska et al. (Citation2021). These perspectives on wellbeing offer a robust framework for evaluating both individual and collective flourishing in diverse life domains. Research such as that conducted by Borgonovi and Pál (Citation2016) and outlined by the OECD (Citation2017) further explores these concepts, delving into the nuances of mental states, emotional wellbeing, and social connectedness among students. They examine factors like happiness, optimism, anxiety, peer relationships, and experiences of bullying, all of which crucially influence students’ academic outcomes. By incorporating these varied dimensions, the wellbeing constructs provide a comprehensive approach to assess and enhance the overall wellness and success of students within educational environments, aiming for more holistic development and better learning experiences.

Several studies across a variety of educational settings have consistently highlighted a strong correlation between students’ English skills, including reading, and aspects of their wellbeing. Notably, happiness and anxiety are significant emotional factors influencing academic outcomes. Research by Reindl et al. (Citation2018) and Li (Citation2020) indicates that students who experience higher levels of joy and positivity tend to achieve better academically, while Lindorff (Citation2020) found that increased anxiety correlates with lower English proficiency. Social wellbeing, characterized by feelings of peer belonging and experiences of bullying, also plays a crucial role in the development of language skills. Students who feel a strong sense of belonging tend to perform better academically due to the support they receive from peers, as shown in studies by Finley (Citation2018) and Mikami et al. (Citation2017). Conversely, those who are victims of bullying often show decreased motivation and poorer academic performance, including in English subjects, as detailed by Alotaibi (Citation2019) and Muluk et al. (Citation2021). The link between student social wellbeing and the broader educational environment is highlighted by research from Acosta et al. (Citation2019) and Kalkan and Dağlı (Citation2021), which emphasizes that the overall school climate significantly impacts key domains of student wellbeing. These studies underscore how achievement-oriented and supportive teacher behaviours contribute to a positive school atmosphere, thereby influencing student learning outcomes in potentially diverse ways. This perspective suggests that the impact of the educational setting on academic performance may extend beyond demographic factors to include the holistic school environment. While these studies collectively affirm the positive influence of wellbeing domains on language learning, there remains a notable gap in comparative research exploring these relationships across different school types and settings. This suggests a need for comprehensive investigations to uncover potential variations and better understand the dynamics of student wellbeing and academic success in diverse educational contexts.

Motivation, anxiety, and difficulty

The impact of learning motivation, anxiety, and difficulty on English skills has garnered recognition in various studies, shedding light on the intricate dynamics within diverse educational settings. Learning motivation, a cornerstone of educational psychology has been significantly developed since work by Brown (Citation1987), which depicted learning motivation as an internal drive that propels individuals to pursue certain actions, highlighting its vital role in guiding and regulating goal-oriented behaviours. Brown’s foundational idea has been expanded upon by researchers such as Svinicki and Vogler (Citation2012) and the OECD (Citation2013), who further described learning motivation as a blend of intrinsic personal drives and reactions to the educational environment. This nuanced understanding emphasizes how motivation shapes the efficacy with which individuals approach their learning tasks. In contrast to the positive aspects of learning motivation, educational challenges like learning anxiety and difficulties also play a crucial role in shaping educational experiences. MacIntyre (Citation1999) defined learning anxiety as the worries and negative emotions learners encounter, which can significantly hinder the learning process. Complementing this, Elkins (Citation2002) identified learning difficulties as obstacles that impede the comprehension and retention of information, often leading to incomplete learning experiences. These challenges are further explored in studies by Alrabai (Citation2014) and the OECD (Citation2017), which attribute learning anxiety to psychological stressors, and by Hamouda (Citation2013), which examines the intricate relationship between emotional states and learning capabilities. Together, these concepts of motivation, anxiety, and difficulty create a comprehensive framework for understanding the complex dynamics of learning, highlighting the intertwined effects of emotional and motivational factors on educational outcomes.

Research spanning various countries and educational settings, including work by Assiddiq (Citation2019), Indrayadi (Citation2021), and Nguyen (Citation2019), has highlighted that motivations for learning English often surpass basic communication needs, embracing cultural enrichment and career advancement as well. Particularly in Islamic school contexts, motivations also include cross-cultural understanding, international travel opportunities, and Islamic propagation, as detailed by Rahman et al. (Citation2021) and Setiyadi and Sukirlan (Citation2016). These studies collectively find that students who are highly motivated to learn English tend to develop stronger English reading skills. On the other hand, English-related challenges such as anxiety and difficulty are noted as major barriers to both motivation and achievement. This is evident in both Islamic educational settings, as discussed by Hermida (Citation2021) and Zubaidi (Citation2021), and in more general contexts, as seen in studies by Ahmad and Nisa (Citation2019) and Saraswaty (Citation2018). These challenges often stem from psychological and technical aspects of reading, which can include a lack of confidence, fear of making mistakes, struggles with unfamiliar topics and vocabulary, and a general disinterest in learning the language. Such factors significantly hinder the development of reading competency. This body of research underscores the urgent need for further empirical studies in diverse educational contexts to deeply explore how learning motivation, anxiety, and difficulty influence language learning, thus providing a clearer understanding of these dynamics across different educational landscapes.

Teacher-level factors

Teacher characteristics and professional development

The influence of teacher characteristics on teaching effectiveness and student language performance has been extensively studied, with multiple investigations underscoring the substantial benefits of teacher experience, education levels, and certification on student achievement in language proficiency. Research by Clotfelter et al. (Citation2006) robustly supports the notion that teachers who are well experienced and highly educated typically achieve superior outcomes in student language development. Experience in teaching often correlates with greater classroom management skills and a deeper understanding of student behaviour and learning needs. Higher education levels in teachers not only enhance their content knowledge but also equip them with advanced pedagogical skills. Simultaneously, Darling-Hammond (Citation2000) suggests that certified teachers have usually met specific professional standards of competence and adhere to a prescribed set of teaching principles. This often leads to more structured and effective teaching practices and adherence to high educational standards. Collectively, these attributes contribute significantly to improved student outcomes. Students taught by teachers who are experienced, well educated, and certified often demonstrate higher achievement levels and a greater ability to apply learned knowledge critically and creatively. These teachers are better positioned to foster a learning environment that is supportive, challenging, and enriching, thus playing a crucial role in the academic and personal development of their students. Interestingly, when exploring the implications of teacher job status, Upa and Mbato (Citation2020) discovered that non-permanent English teachers demonstrate strong teaching abilities, positively influencing their students’ learning experiences.

Furthermore, the influence of professional development (PD) on teaching effectiveness and student outcomes has been significantly highlighted in educational research, notably in studies such as the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) conducted by the OECD (Citation2014). This survey, along with research by Desimone et al. (Citation2002) and Didion et al. (Citation2020), has established a strong link between ongoing PD and enhanced teaching skills, particularly in fostering improvements in student reading competencies. Continued PD provides educators with regular updates on the latest educational strategies and theories, specifically those related to literacy. This exposure is crucial as it equips teachers with advanced methods and tools to effectively engage students and improve their reading skills. Teachers learn to implement innovative literacy teaching techniques that can be adapted to the diverse learning styles and needs of students. Consequently, this ongoing professional growth not only boosts teachers’ confidence and proficiency in delivering lesson instruction but also directly impacts student achievement. However, the prior studies also argue that the teacher’s demographics and effectiveness of PD in equating student language achievement consistently across different teacher backgrounds and school contexts remain varied. This inconsistency highlights the need for more detailed research. Such studies should aim to dissect the specific effects of the variables within varied educational environments to address the disparities in student language skills.

Job-related attitudes and teaching effectiveness

The concepts of teacher job-related attitudes, such as teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction, play crucial roles in shaping educational outcomes and the quality of instruction in schools. Teacher self-efficacy, a concept introduced by Bandura (Citation1991), refers to a teacher’s belief in their ability to reach specific performance targets. This belief strongly influences their capability to plan, organize, and execute instructional tasks effectively, aiming to meet educational goals. Studies, such as those by Demir (Citation2020) and the OECD (Citation2009), have shown that teachers who possess a high sense of self-efficacy tend to demonstrate greater persistence, are more open to adopting innovative practices, and generally perform better in their instructional roles. Parallel to the concept of self-efficacy is the idea of teacher job satisfaction, which was defined by Locke (Citation1969) as a positive emotional state derived from one’s appreciation of their teaching role. This feeling of satisfaction encompasses contentment, comfort, and fulfilment within the profession. Further research by Lopes and Oliveira (Citation2020) and the OECD (Citation2009) suggests that job satisfaction is deeply connected to the interplay between teachers and their professional responsibilities. This connection results from teachers’ emotional responses to their roles and their expectations and perceptions of their careers. When teachers feel satisfied and valued in their roles, they are more likely to deliver high-quality education, which in turn positively impacts student academic performance. These linked concepts highlight the importance of fostering environments that enhance both the efficacy and satisfaction of teachers to promote optimal educational outcomes.

The study by the OECD (Citation2009) provides compelling evidence for the significant direct influence of teacher job-related attitudes, such as self-efficacy and job satisfaction, on teaching effectiveness and indirectly on student outcomes. This research highlights teachers who exhibit high levels of self-efficacy and believe strongly in their capabilities to manage classroom challenges and effectively deliver curriculum, which is a critical driver of their success in fostering student learning and engagement. These findings are echoed in English as a foreign language (EFL) settings, where effective teaching methods, including the use of technology especially in reading class, have been shown to critically influence student reading performance, as noted in prior studies (Firdaus & Mayasari, Citation2022; Par, Citation2020; Yazar, Citation2013). The incorporation of technology in EFL classrooms has been identified as a significant enhancer of student motivation and achievement, a trend supported by research from Azmi (Citation2017). Such effectiveness in teaching practices and their positive outcomes are not confined to EFL or specific educational settings but are consistent across various cultural and educational contexts, including Islamic schools, as demonstrated by Dimyati and Avicenna (Citation2022), the OECD (Citation2009), and Yafiz et al. (Citation2022). However, while information and communication technology (ICT) generally promotes learning, it can also have a downside, such as inducing anxiety among students, as highlighted by Bhuttah et al. (Citation2021). These studies collectively emphasize the multifaceted effects of teacher attitudes on both the effectiveness of teaching and the broader spectrum of student learning experiences.

Furthermore, the direct effects of teacher efficacy and job satisfaction on student language skills have been recognized. Research findings, such as those from Alibakhshi et al. (Citation2020) and Ma (Citation2022), underscore that teachers who possess high levels of self-efficacy and satisfaction are instrumental in elevating student performance, particularly in language and reading skills. Teachers with strong self-efficacy are found to be more creative and innovative in their instructional approaches, which not only enhances the quality of teaching but also boosts student motivation and achievement in learning. This increase in creativity among teachers directly influences their teaching practices, making learning experiences more engaging and effective. Concurrently, job satisfaction among teachers contributes positively to academic outcomes by fostering an encouraging and supportive classroom environment. According to previous studies (Afshar & Doosti, Citation2016; Banerjee et al., Citation2017), satisfied teachers are likely to build stronger relationships with their students, which are crucial for the students’ psychological wellbeing. These positive relationships help increase students’ motivation to learn and decrease problems associated with learning, creating a more conducive environment for academic success. The body of research discussed underscores a compelling correlation between teacher attitudes, including self-efficacy and job satisfaction, and effective teaching practices, all of which significantly influence student language outcomes. Despite clear evidence linking teacher attitudes and teaching effectiveness to student learning outcomes, there is a significant lack of specific research on how these factors improve English reading skills in varied educational contexts. Conducting such focused research will help confirm the broad applicability of these benefits and allow for the creation of customized strategies that can be effectively implemented, ensuring educational interventions are both effective and appropriately tailored to their contexts.

School-level factors

School demographics

The disparities in language skills among students from diverse school demographics have received considerable attention in various educational research. Studies like those conducted by Cadiz-Gabejan (Citation2022) and Madrid and Barrios (Citation2018) in global contexts have highlighted substantial differences in English language proficiency, especially in reading skills, where students in private schools generally outperform their peers in public settings. The existence of this achievement gap extends beyond different school sectors; it is also shaped by various additional factors, such as school location aligned with the quality of school facilities and the nature of educational services offered. For example, Ellah and Ita (Citation2017) noted that urban schools tend to have better facilities, while research by Ulva and Widyawati (Citation2022) found that full-day school services facilitate enhanced learning activities. Urban schools often have distinct advantages in terms of resources that can significantly boost student achievement compared to their rural counterparts. Urban schools also benefit from greater funding and investments, which facilitate the integration of technology in the classroom, further enhancing teaching and learning through digital tools and resources. Simultaneously, full-day schools offer numerous benefits that can significantly enhance student achievement across various educational domains. By extending the hours students spend in an educational environment, full-day schools provide more time for both academic and extracurricular activities, allowing for a more in-depth exploration of their learning.

The previous findings corroborate with the studies in specific contexts, such as rural Islamic schools in Bangladesh, illustrating that resource disparities significantly impact language competencies (Asadullah, Citation2015; Asadullah et al., Citation2007). Similarly, Suardi et al. (Citation2017) documented benefits in language learning from full-day programs in Indonesian Islamic boarding schools. Moreover, several studies support the varied effects of school demographics on student outcomes. For instance, Ali et al. (Citation2011), Muhajir (Citation2016), and Muttaqin et al. (Citation2020) indicate that English language learning may be more effective in public Islamic schools compared to their private counterparts. This contradiction underscores the complex relationship between school attributes – such as funding, teacher quality, and instructional methods – and student language skills. The mixed results signal the need for more comprehensive comparative research that spans different educational settings. Such studies could dissect the myriad factors influencing language competencies, enabling a clearer understanding of the conditions under which language learning thrives or falters. This nuanced examination is crucial for developing targeted educational strategies that effectively address and leverage the unique characteristics of each school environment to optimize language learning outcomes.

School autonomy and resources

The significant relationships between school autonomy, resources, and student achievement have been well documented. School autonomy is defined as the extent to which individual schools have the freedom to make independent decisions across a variety of operational domains without excessive external oversight. This concept primarily encompasses the ability to determine curriculum content, teaching methodologies, and assessment strategies to better tailor educational experiences to the specific needs of the student body (OECD, Citation2011). When schools possess the autonomy to make decisions that directly affect their operational environment, they can align their resources more strategically to meet the specific needs of their students and community (Patrinos et al., Citation2015). This alignment is crucial, as it allows schools to optimize the use of available resources, whether these are physical assets like technology and libraries, or human resources such as teachers and administrative staff. Autonomous schools often demonstrate a higher capacity to innovate and adapt to changing educational demands, which can result in enhanced student learning experiences and outcomes. However, the positive impacts of autonomy are most pronounced when schools also have access to adequate resources. Without sufficient resources, autonomy alone may not be enough to improve educational outcomes significantly. This claim is supported by some studies conducted in global contexts suggesting the prominent roles of school resources on student language performance. Enhanced facilities and access to qualified English teachers are crucial for fostering greater learning engagement and boosting reading achievement (Eric & Ezeugo, Citation2019; Mahmood & Gondal, Citation2017). The studies underline the advantageous impact of school facilities, including classrooms and libraries, on students’ learning engagement and reading achievement. Quality learning materials and human resources, such as qualified English teachers, are also integral factors linked to improved reading performance globally.

Research exploring the impact of school autonomy on English language skills within the educational context, such as Islamic schools, particularly in Indonesia, has been limited, yet existing studies shed light on some critical challenges. The underperformance of students in certain educational settings, particularly highlighted in studies focused on Indonesian Islamic schools, is frequently linked to the lack of adequate educational resources. Key issues identified include poor facilities and insufficient teacher quality, which significantly impede effective teaching and learning (ADB, Citation2014; Kholis & Murwanti, Citation2019; Muhajir, Citation2016). These substandard conditions hinder students’ ability to engage with and benefit from the educational process, leading to lower academic achievement. The environment in which students learn greatly influences their ability to absorb and apply knowledge, and when schools lack necessary resources such as well-maintained facilities and highly qualified teachers, the educational experience and outcomes can be severely compromised. This connection underscores the critical need for investment in educational infrastructure and professional development to boost the quality of education and student performance in these settings. This scarcity of specific studies points to an urgent need for more detailed investigations that consider how varying levels of school autonomy might influence the deployment and effectiveness of resources in enhancing English language competencies within distinct school settings. Such research would not only fill a critical knowledge gap but also potentially guide policy adjustments and resource allocations to improve educational outcomes in these communities.

School climate

The concept of school climate, while lacking a universally accepted definition, is described by the OECD (Citation2005) as encapsulating the culture and life within a school. This includes the prevailing attitudes and relationships that characterize the school community, aspects of which cover teacher enthusiasm, their concern for student achievement, the support provided, and the disciplinary environment. This expansive understanding underscores the profound impact that school climate can have on student outcomes, especially in critical academic areas such as language and reading skills. By fostering a positive and supportive educational environment, schools can significantly influence the educational experiences and success of their students, making school climate a pivotal focus for educational improvement initiatives. This assertion is corroborated by numerous studies that highlight the significant relationship between positive school climates, teacher attitudes, and their effectiveness, all of which are closely linked to student outcomes. Research by Zakariya (Citation2020) underscores how supportive and encouraging school environments positively influence teacher positive attitudes. Additionally, İhtiyaroğlu and Demirbolat (Citation2016) provide evidence that such climates enhance teacher effectiveness, which in turn has a direct impact on student outcomes. These studies collectively illustrate that a positive school climate not only uplifts educators but also optimizes their ability to deliver high-quality education, thereby fostering better learning environments.

Furthermore, research supports the notion that the school climate, shaped by factors such as teacher morale and support, directly influences students’ language performance. For instance, teachers who exhibit high morale are likely to bring positive attitudes to their classrooms, creating a learning atmosphere that is both encouraging and conducive to student engagement and success (Govindarajan, Citation2012; OECD, Citation2016). Additionally, the presence of supportive teachers has been shown to boost students’ motivation and assist them in overcoming learning challenges, thereby enhancing educational outcomes (Lumpkin, Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the elements of academic pressure and discipline within a school’s climate also play a crucial role, with studies indicating that environments oriented towards achievement can positively correlate with improved learning performance (Shouse, Citation1996). Specifically, the study by Ning et al. (Citation2015) highlights a clear connection between positive classroom disciplinary climates and enhanced reading outcomes, suggesting that well-managed classrooms facilitate better learning environments that directly contribute to improved academic performance. Similarly, research by Ehiane (Citation2014) in Nigeria supports the notion that disciplined school environments play a critical role in boosting learning effectiveness, thereby improving academic outcomes across the board. While these studies focus on broader educational contexts, research specific to different school settings, such as those conducted by Na’imah et al. (Citation2022), is more limited. However, the study acknowledges the significant influence of Islamic or religious values in creating an effective school climate within madrasah schools in Indonesia and Malaysia, suggesting that these values might shape student outcomes in unique ways. Such findings indicate that while the principles of effective school climates are universally recognized, the specific cultural and religious contexts can vary their impacts, necessitating tailored approaches to cultivating positive environments in diverse educational settings.

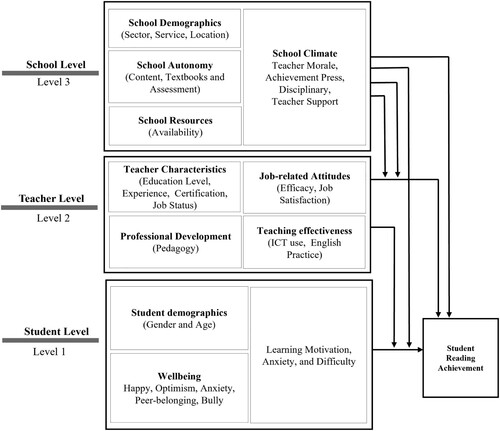

Conceptual framework

The hypothesized three-level (3L) model of English reading achievement, as illustrated in , is grounded in the theoretical background outlined in the previous section. This proposed model applied to both the sekolah/non-madrasah and madrasah groups elucidates how various predictors at the school, teacher, and student levels directly influence students’ English reading performance as the outcome variable. At the school level, predictors encompass characteristics, autonomy, resources, and climate. The teacher level includes predictors related to teacher characteristics, professional development, job-related attitudes, and teaching effectiveness. Student-level variables comprise demographics, wellbeing, learning motivation, anxiety, and difficulty. The 3L model also accounts for potential cross-level interactions among the school, teacher, and student levels, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate dynamics shaping English reading achievement across the comparative groups. The forthcoming methods section will delve into specific explanations of the derived variables employed in this study.

Methodology

Participants

This study targeted secondary education within Bone Regency, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, encompassing a diverse demographic across 84 schools, split into 36 non-madrasah/sekolah schools managed by the MoEC and 48 madrasah schools overseen by the Ministry of Religious Affairs (MoRA). The participant pool included 168 English teachers and 16,021 students – 9,205 in sekolah and 6,816 in madrasah. Aiming for a representative sample, the research employed a two-stage stratified sampling design which involved segmenting the population into comparable groups for random selection from these strata. The stratification was meticulously designed at multiple levels, particularly integrating districts and schools to enhance sample representativeness.

A total of 64 English teachers/classrooms were chosen for the study, comprising 34 from sekolah and 30 from madrasah. The selection process involved a combination of probability random stratified sampling and purposive sampling methods to ensure a robust and representative sample. Initially, districts were randomly selected to ensure geographical diversity and eliminate selection bias at the regional level. Out of 27 districts, 12 were randomly chosen based on the presence of at least one non-madrasah (sekolah) and one madrasah school. Within these selected districts, participants – including students and teachers – were drawn from 16 sekolah and 14 madrasah schools in the second sampling stage. Teachers and students were then purposely chosen based on specific criteria relevant to the study’s objectives, such as schools with at least two English teachers/classrooms and their Year 12 students. Ultimately, 726 students from sekolah and 593 from madrasah schools were sampled. Overall, 30 schools, 64 English teachers, and 1,319 students participated in this study. The robust sampling methodology, reinforced by guidelines from Cohen et al. (Citation2018) and Mills and Gay (Citation2016), ensures a well-represented cross-section of sekolah and madrasah schools, thereby instilling confidence in the study’s generalizability and reliability.

In addition, this study primarily concentrates on evaluating the effect of various factors at the school, teacher, and student levels on the English reading achievements of Year 12 students in Indonesia. Given that these Year 12 students are at a pivotal point in their educational journey, where they are preparing for national exams and transitioning either to higher education or entering the workforce, understanding their proficiency in English reading is crucial. This proficiency serves as a key indicator of their readiness to thrive in future academic and professional settings where English plays an increasingly dominant role. By focusing on English reading achievement, the research aims to gauge how well prepared Indonesian students are to participate effectively in international contexts. This includes their ability to succeed in globally oriented higher educational programs and compete in international job markets, making this an essential area of study.

Derived variables

offers an exhaustive overview of three key sets of variables covering student, teacher, and school levels that are integral to the conceptual model, encompassing both sekolah and madrasah groups. At the school level, adapted from OECD (Citation2005), a comprehensive set of four variables – school characteristics, autonomy, resources, and climates – sourced from the school principals’ responses to sekolah and madrasah questionnaires was employed. The variables under school characteristics encompassed features such as school sector (SCSECTOR), service (SCSERV), and location (SCLOC). Simultaneously, the autonomy levels relating to the selection of textbooks (AUTB), content (AUCC), and assessment (AUAS) were probed. Resource availability (RSCAV) was gauged based on the perception of staff, learning materials, and facilities by school principals. Climate responses delved into various aspects of school life and environment, encapsulating teacher–student relationships (MORALE), pressure to achieve (PRESS), disciplinary measures (DSCPLN), and teacher support (SUPPORT). Furthermore, five group variables at the teacher level (Level 2), drawn from OECD (Citation2014), encompassed teacher characteristics such as level of education (EDULV), job status (JBSTAT), teaching experience (TCEXP), certification (CERT), professional development (PD), job-related attitudes: job satisfaction (JOBS), teaching efficacy (EFF), ICT usage (ICTUS), and reading practice (READ) – grouped as indicators of teaching effectiveness.

Table 1. Variables used in this study.

Additionally, four theoretical dimensions at the student level were measured: demographic attributes like gender (GENDER) and age (AGE); wellbeing domains – happiness (HAPPY), anxiety (ANX), peer belonging (PEER), and bullying (BULLY) adapted from OECD (Citation2017); three scales of reading motivation/MOTREAD (OECD, Citation2019); anxiety/ANXREAD and difficulty/DIFREAD (Hamouda, Citation2013), associated with English reading; and reading achievement, derived from English reading test results adopted from Ujian Nasional Tahun Pelajaran 2016/2017 (National Examination Test for Academic Year 2016/2017; MoEC, 2017). The coding methodology varied across variables, with raw scores used for school characteristics, school autonomy, teacher attributes, and student demographics. While other scales were measured using Likert scale responses (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree) and converted to weighted likelihood estimate (WLE) scores via Rasch analysis to mitigate scoring biases. Additionally, the representation of school location was transformed into dummy variables – school locations in the village (SCLOC1), district (SCLOC2), and city (SCLOC3, the baseline variable) – distinguishing treatment groups using binary values. The validation process encompassed scale and item stages, undertaken using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017) and Conquest software (Adams et al., Citation2020), ensuring the integrity and quality of the measurement framework adopted for the study.

During the validation process of the measurement instruments, various scales relevant to school and teacher data – such as MORALE, PRESS, DSCPLN, SUPPORT, JOBS, EFF, ICTUS, and READ – were rigorously evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for both study groups. These scales demonstrated strong reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values indicating high internal consistency: MORALE (α = .85), PRESS (α = .80), DSCPLN (α = .80), SUPPORT (α = .86), JOBS (α = .80), EFF (α = .88), ICTUS (α = .84), and READ (α = .91). The CFA results yielded highly satisfactory goodness-of-fit indices, affirming the robustness of the scales used. The analysis revealed factor loadings ranging from 0.40 to 0.98, highlighting a substantial correlation between observed variables and their respective constructs. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for each scale exceeded the threshold of .60, further attesting to the adequacy of the construct measurements. Additionally, both composite reliability (CR) and coefficient omega exceeded 0.80, suggesting excellent internal consistency across the scales. The model’s overall fit was further supported by the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), each surpassing the 0.90 mark. Furthermore, the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) was maintained at or below 0.05, and the weighted root-mean-square residual (WRMR) remained below 0.75, both indicating a precise fit of the model to the data (Wang & Wang, Citation2020). These metrics collectively underscore the validity and reliability of the instruments used for teacher and school data.

With an adequate sample size exceeding 200 participants per group, as recommended by Lee and Smith (Citation2020), this study employed multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) using the measurement invariance technique to assess whether different sample groups share a consistent psychometric understanding of the underlying constructs. Initially, separate baseline CFA was conducted for both groups across seven distinct scales: HAPPY, ANX, PEER, BULLY, MOTREAD, ANXREAD, and DIFREAD. The results from these analyses showed acceptable goodness-of-fit metrics, confirming the models’ adequacy. Subsequently, the study advanced to more intricate comparisons by testing three levels of measurement invariance: configural (pattern), metric (item loading), and scalar (intercept). The configural models for all variables demonstrated a strong fit, with CFI values greater than 0.98 and TLI values over 0.90, while both the RMSEA and the WRMR remained well below 1.00, thereby validating the configural stage of invariance. Further testing involved evaluating changes in ΔCFI between metric and configural models as well as between scalar and metric models with deviations between 0.01 and −0.01 considered as indicating invariance, as per the methodology outlined by Cheung and Rensvold (Citation2002). The study found statistically significant ΔCFI values (less than 0.01) in nested model comparisons across all constructs. Citing similar research methodologies used by Wang and Wang (Citation2020) and Pezirkianidis et al. (Citation2021), the study confirmed that full measurement invariance is established when scalar invariance is completely supported.

This comprehensive analysis led to the conclusion that the measurement tools used are comparable among students from both sekolah and madrasah groups, revealing that students from both non-madrasah and madrasah educational backgrounds exhibit similar perceptions on the scales assessing learning motivation, anxiety, perceived difficulty, and overall wellbeing. Additionally, the performance metrics of the achievement test, including item fit and discrimination measures, highlighted its effectiveness and suitability for assessing the intended constructs. Mean square (MNSQ) values fell within the ideal range of 0.97 to 1.0, as recommended by Bond and Fox (Citation2015), indicating a proper fit of items to the model’s expectations. The item discrimination indices, all exceeding the 0.20 benchmark, underscored the test’s capability to distinguish varying levels of respondent abilities, affirming the test items’ effectiveness in differentiating based on the assessed construct. The item separation reliability (ISR) score was 0.99 for each scale, underscoring the precision in categorizing items by difficulty, enhancing the test’s efficacy in accurately discerning between respondents’ abilities. In addition, detailed descriptive statistics and correlations between variables at the levels of school, teacher, and student are provided in through .

Hierarchical linear modelling

The utilization of hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) through HLM software (Raudenbush et al., Citation2019) was employed to investigate the intricate relationships present within and between hierarchical levels within grouped data. This approach facilitated a more nuanced examination of direct and cross-level interaction effects among variables distributed across varying data hierarchies. HLM analysis assumes a single dependent variable at the individual level (Level 1) influenced by multiple predictors or independent variables within and between hierarchical levels (Luo & Azen, Citation2013; Woltman et al., Citation2012). The implementation of HLM analysis involved several steps. Initially, the data were organized into three distinct levels: students, teachers, and schools, delineated separately for sekolah and madrasah groups. Students were nested within classrooms or teachers, while classrooms or teachers were nested within schools or principals. Subsequently, a null model devoid of predictors was run to ascertain the interclass correlation (ICC). Next, random coefficients were introduced to examine the direct effects of predictors at Levels 1, 2, and 3 (student-, teacher-, and school-level factors) on student outcome. This phase assessed how various predictors at different levels impacted English reading achievement. Concurrently, cross-level interaction effects were explored, shedding light on moderation between student-level (Level 1), teacher-level (Level 2), and school-level (Level 3) predictors. However, only predictors demonstrating statistical significance at a p value < .05 were integrated into the model for both groups. Recognizing HLM's limitations in facilitating group comparisons, separate analyses were conducted for the sekolah and madrasah groups, allowing for a focused and detailed investigation of each educational setting.

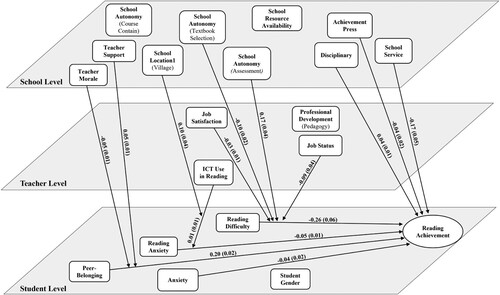

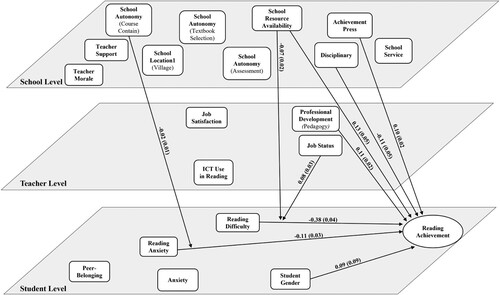

Findings

The equations presented in and emerged from the results of null and full models applied to both the sekolah and madrasah Groups. In ’s model, READINGijk represents students’ English reading achievement, and π0jk signifies the intercept of students’ achievement (i) under teacher (j) in school (k). The symbol eijk denotes a Level 1 random effect, capturing the deviation of student i in the teacher j’s classroom within school k from the mean score of reading performance. In the Level 2 model, each teacher’s mean (π0jk) varies randomly around a grand mean across the school. β00k signifies the average score of students’ reading achievement in school (k), and r0jk represents the teacher-level error term, signifying the deviation of teacher mean (j) from the school grand mean (k). In the Level 3 model, β00k stands for the mean of the intercept of students’ reading performance in school (k). y000 represents the grand mean of students’ reading performance across schools, and u00k describes the random error for the school effect. Likewise, illustrates the final model applied to both sekolah and madrasah groups. The equations presented separately for each group articulate that the combined English reading results are defined as a function of the overall intercept (γ000). In the sekolah group, seven direct or main effects, eight cross-level interaction effects, and a random error are significantly revealed. Simultaneously, the madrasah group exhibits seven direct effects, six cross-level moderating effects, and a random error. However, only significant (p < .05) direct and moderation effects are displayed in the final-model equations for both groups. A more detailed exploration of the predictors and their direct and indirect influences on the outcome is discussed in the subsequent section, providing a nuanced understanding of how various factors contribute to students’ English reading achievement in the different contexts of sekolah and madrasah schools.

The direct effect of predictors on students’ reading scores between the groups

and and intricately showcase the conclusive outcomes of the final model’s fixed effects concerning students’ reading performance across the compared groups. Among the tested predictors, student-level factors such as reading anxiety (ANXREAD) and difficulty (DIFREAD), alongside school-level aspects like achievement pressure (PRESS) and disciplinary measures (DSCPLN), have significant direct effects on student English reading scores in both sekolah and madrasa groups. The negative estimates of DIFREAD (sekolah, β = −0.26; madrasah, β = −0.38) and ANXREAD (sekolah, β = −0.05; madrasah, β = −0.11) indicate that high levels of reading difficulty and anxiety correlated with poorer English reading outcomes in both sekolah and madrasah school settings. Divergent effects of PRESS and DSCPLN between the groups reveal distinct patterns. Specifically, in non-madrasah schools, higher pressure for academic achievement (β = −0.04) tends to result in lower reading scores, whereas increased discipline (β = 0.04) corresponds to higher reading achievement. Conversely, in madrasah schools, elevated pressure to achieve (β = 0.10) and lower discipline (β = −0.11) are linked to improved English reading test scores. Each standard deviation rise in PRESS indicates a 0.04 decrease in sekolah students’ scores but a 0.10 increase in madrasah students’ reading performance. Similarly, a 1 SD increase in DSCPLN leads to a 0.04 increase in sekolah school scores but a 0.10 decrease in madrasah students’ English reading achievements. The findings suggest that in non-madrasah schools, increased academic pressure may lead to stress or anxiety among students, potentially impairing their reading performance. Conversely, students in madrasah schools might perceive academic pressure as a positive motivational factor, in contrast to their peers in sekolah schools, who may find it stressful. Additionally, the disciplined or structured environments and clear behavioural expectations at sekolah schools could enhance students’ academic performance in English reading. In contrast, the less rigid disciplinary approach in madrasah schools might create an environment more conducive to learning reading skills, possibly by allowing greater freedom or creativity in the learning processes.

Figure 2. The final three-level model of students’ reading achievement for the sekolah group.

Note: No arrow = not statistically significant (p > .05).

Figure 3. The final three-level model of students’ reading achievement for the madrasah group.

Note: No arrow = not statistically significant (p > .05).

Table 2. Final-model results: fixed effects for English reading achievement.

Additionally, while predictors like peer belonging (PEER), anxiety (ANX), and school service (SCSERV) exclusively also have direct effects on student reading achievement in the sekolah group, variables like gender (GENDER), teacher professional development, and school resources availability (RSCAV) directly affected students’ English reading tests in madrasah schools. High-performing students in the sekolah group were depicted as those more engaged with peers, less anxious, and enrolled in public non-madrasah schools. Conversely, low-performing students in madrasah settings were predominantly male, while high reading scores were associated with madrasah students taught by teachers with extensive pedagogical knowledge through PD programs and studying in madrasah schools with ample resources available. These findings imply that increased peer engagement and reduced anxiety contribute to score increments and decrements of 0.20 and 0.04, respectively, in sekolah students’ reading scores. Moreover, a 1 SD rise in RSCAV in madrasah results in a 0.13 increase in students’ English reading achievement in that context.

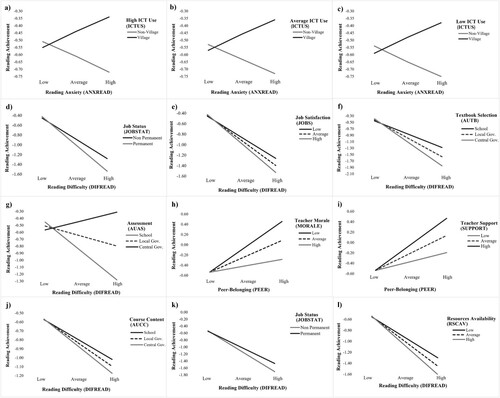

The interaction effects of the predictors on the slope of student-level factors and reading achievement across the groups

and intricately depict the comprehensive array of interaction effects among various variables concerning the slope of student-level predictors and their effects on English reading performance in both the sekolah and madrasah groups. Diverse predictors emerged to moderate the slope of students’ reading anxiety (ANXREAD) and difficulty (DIFREAD) in both settings. Nevertheless, sekolah schools exhibited unique cross-level interaction effects between variables such as schools located in the village (SCLOC1, β = 0.10), ICT use (ICTUS, β = 0.01) at the teacher level, ANXREAD slope, and reading achievement. Notably, increased technology usage in English reading lessons within city and district schools demonstrated a potential to alleviate reading anxiety and bolster reading outcomes, contrasted by stronger anxiety effects in village-based schools. Furthermore, sekolah group analysis unravelled four significant cross-interactional effects involving teacher job status (JBSTAT, β = −0.09), job satisfaction (JOBS, β = −0.03), school autonomy in textbook selection (AUTB, β = −0.10), and assessment (AUAS, β = 0.17) concerning the slope of students’ reading difficulty (DIFREAD) and its effect on English reading achievement. These effects highlighted the influence of teacher permanence, job satisfaction, textbook selection autonomy, and assessment policy autonomy on students’ reading difficulties and achievements. Additionally, sekolah-specific effects involving peer belonging (PEER), teacher morale (MORALE, β = −0.05), and teacher support (SUPPORT, β = 0.05) emphasized intriguing dynamics. Lower teacher morale heightened the impact of peer belonging, indicating stronger engagement among peers in these settings. Conversely, higher teacher support within non-madrasah schools amplified the effect of peer belonging on reading performance, underscoring the significance of supportive teacher–student relationships. Moreover, the analysis unveiled the moderation effects of school autonomy over course content (AUCC, β = −0.02), teacher job status (JBSTAT, β = 0.08), and school resource availability (RSCAV, β = −0.07) on the slope of student-level predictors. These effects portrayed the effect of school control over course content, teacher permanence, and school resources on reading anxiety, difficulty, and subsequently, reading achievement. These findings collectively underscore the nuanced interplay between diverse factors across both sekolah and madrasah school settings, emphasizing their multifaceted influence on students’ English reading performance.

Variance explained by the three-level model between groups

provides a comprehensive overview of the estimated variance components and the proportions of variance explained by both null and final models in the sekolah and madrasah groups (see and ). In the null model, student-level factors account for 88% (.87/ [.87 + .03 + .09] = .88) of the variability in English reading performance in the sekolah group and 81% (.57/ [.57 + .09 + .04] = .81) in the madrasah group. At the teacher level, 3% (.03/ [.87 + .03 + .09] = .03) variance is observed in sekolahs, and 13% (.09/ [.57 + .09 + .00] = .13) in madrasahs. Meanwhile, 9% (.09/ [.87 + .03 + .09] = .09) in sekolah schools and 6% (.04 / [.57 + .09 + .04] = .06) in madrasah schools indicate variance at the school level concerning students’ English reading scores. This variance at the school level is intriguing and reflects differing parental motivations and school selection criteria. While the data in this paper do not include parental socioeconomic status (SES) background, it is generally observed that parents often send their children to private schools when they are not accepted into public schools. This situation suggests that some private schools may serve as a “residual” option. In contrast, many parents choose madrasahs not out of necessity, but due to a preference for the religious values and affiliations these schools embody (Asadullah et al., Citation2015). This distinction likely influences the observed variance, as the student populations in private schools and madrasahs may differ significantly in terms of parental expectations and community support. Comparing the final models to the null model, as shown in , incorporating Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 predictors in both groups explains about 85% in the sekolah group and 82% in the madrasah group of the variance at the student level. At the teacher level, the final models account for approximately 67% of the sekolah group and 88% in the madrasah group, while at the school level, they explain around 67% and 75% of the variance in the sekolah and madrasah groups, respectively. The comparison reveals slight differences in the total available variance, with 83% in the sekolah and 82% in the madrasah groups explained by the model at all three levels. Approximately 17% of the variance in the sekolah and 18% in the madrasah group remains unexplained, suggesting the potential influence of other factors, such as family background, including SES and family support not accounted for in the model. This comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of considering various levels of predictors in understanding the complex interplay of factors affecting students’ English reading performance in different educational settings.

Table 3. Estimations of variance components for English reading achievement across the groups.

Discussion

This study bears significant importance in its comprehensive examination of the contrasting dynamics between non-madrasah or sekolah and madrasah education in Indonesia, focusing on multifaceted factors at the school, teacher, and student levels that impact student achievement, such as English reading competence. Using the HLM method, this study unfolds insightful findings shedding light on the nuanced intricacies and interactions among these tested factors, ultimately providing a holistic perspective on the English achievement disparities observed between sekolah and madrasah schools in Indonesia. For example, this study revealed that the 3L models explain approximately 83% and 82% of the variance for sekolah and madrasah groups, respectively, showcasing the multifaceted factors influencing student performance. The final models highlight their significant roles, accounting for substantial variances, and emphasizing the importance of these hierarchical levels in shaping student outcomes across the groups. Although the models explain a significant portion of the variance, approximately 17% in sekolah and 18% in madrasah remain unexplained, suggesting the presence of unaccounted factors, such as family socioeconomic backgrounds, influencing students’ English reading performance. This study acknowledges that the influence of family backgrounds as evidenced by parental education, occupation, wealth, and SES, has been frequently linked to higher academic achievement, including in reading, due to better learning resources and more supportive home environments (Liu et al., Citation2020). Students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds often have access to a broader range of resources, including books, educational materials, and technology, which can significantly enhance their reading skills from an early age. Additionally, such families are more likely to afford extracurricular activities that promote advanced literacy skills, such as English tutoring or enrolment in specialized programs beyond the schools. Although the study’s current data set does not include these variables, future studies could benefit from incorporating them to account for the remaining variance observed. Methodologically, this could involve expanded data collection efforts or longitudinal studies designed to capture these influences over time. By addressing these gaps, subsequent research could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the factors which include family background factors influencing student performance in diverse educational settings.

The research findings from both sekolah and madrasah groups illuminate the multifaceted dynamics between student learning difficulties, school climates, and English reading achievements. The study underscores the detrimental effects of reading problems and anxiety on students’ English reading scores, a pattern observed universally in both sekolah and madrasah schools. This corroborates earlier research (Ahmad & Nisa, Citation2019; Saraswaty, Citation2018) highlighting the adverse consequences of learning anxiety and difficulties in academic performance. The findings serve as a substantial reminder of the multifaceted nature of academic struggles, emphasizing the need for inclusive teaching strategies that address both learning challenges to enhance students’ reading abilities and overall academic success. Teachers in sekolah and madrasah schools should be trained in adaptive pedagogical techniques that recognize and address language anxiety, such as providing constructive feedback in private instead of public critiques and using error correction methods that focus on learning opportunities rather than faults. Furthermore, incorporating technology, such as learning apps or online platforms, can provide students with personalized and self-paced learning options, allowing them to learn comfortably and confidently at their rhythm (Janssen & Kirschner, Citation2020). In addition to technological tools, practising collaborative or cooperative learning can also significantly enhance language acquisition. Collaborative learning encourages students to engage with their peers through group activities, discussions, and projects, fostering a supportive and interactive learning environment. This approach not only helps improve language skills but also develops critical thinking, communication, and teamwork abilities. By integrating both individualized technological resources and cooperative learning strategies, students can benefit from a comprehensive, well-rounded approach to language education that addresses various learning styles and needs.

Remarkably, the study unveils the nuanced influence of school climates, specifically achievement pressure and disciplinary levels, on student English reading performance. madrasah students thrive amidst high achievement pressure and minimal disciplinary constraints, indicating that a competitive atmosphere propels their academic achievements in English reading. Conversely, students in sekolah excel in environments emphasizing discipline over achievement pressure. This divergence challenges established research paradigms (Ehiane, Citation2014; Ning et al., Citation2015; Shouse, Citation1996) by demonstrating that the effects of achievement pressure and disciplinary levels are intricately entwined with specific school contexts and students’ unique needs. The impact of pressure and discipline on student reading performance across different types of schools, such as Indonesian madrasah and sekolah education, suggests that the effects are not uniform and may be influenced by a variety of factors including cultural norms and individual student perceptions. In madrasah schools, where academic pressure is often viewed as a motivating force (Koo et al., Citation2009), students may use this pressure as a catalyst for improvement, seeing it as a positive challenge that drives their educational progress. Conversely, in sekolah schools, similar pressures can lead to stress and anxiety (Sarouni et al., Citation2016), potentially detracting from students’ performance, particularly in areas like reading. This indicates a disparity in how students in different educational settings respond to academic stress, which could be linked to the underlying educational philosophies and cultural attitudes towards schooling.

The differences in how discipline is perceived and internalized across various educational settings significantly impact student outcomes. For instance, sekolah schools, known for their stricter discipline measures, often report better academic performance. This suggests that students in these environments may thrive under structured and predictable learning conditions, where clear rules and consistent expectations provide a sense of security and focus (Ning et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, madrasah schools, which tend to implement less rigid disciplinary approaches, often foster an educational climate that allows greater autonomy for students. This flexibility can be particularly beneficial in promoting creative and self-directed learning experiences, where students are encouraged to explore and engage with the material in a manner that suits their learning styles and interests (Han, Citation2021). The contrast between these approaches highlights the importance of tailoring disciplinary and educational strategies to the specific needs and preferences of the student population, as the effectiveness of these strategies can vary widely depending on the cultural context and the inherent values of the educational institution. This adaptability is key in maximizing educational outcomes and ensuring that students not only achieve academically but also develop the skills and confidence necessary for independent learning and future success.

These findings underline the necessity for educational policymakers and school administrators in sekolah and madrasah schools to consider cultural and perceptual differences when implementing or modifying academic pressures and disciplinary strategies. Practical implications might include the introduction of customizable education plans that allow for adjustments based on the cultural context and individual needs of the students. For example, madrasah schools could organize workshops at the beginning of the academic year to help students set specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound goals. This process involves students identifying what they hope to achieve academically throughout the year, with realistic targets that align with their capabilities. Simultaneously, by focusing on positive reinforcement and restorative justice, sekolah schools can build a culture of self-discipline and mutual respect, where students are motivated to engage in learning and achieve their educational goals. This environment enables students to thrive academically and socially, preparing them for successful futures both in and out of the classroom. Moreover, both schools could implement regular assessments of student stress levels and satisfaction to better tailor their approaches. Additionally, professional development programs for sekolah and madrasah teachers that focus on cultural competency and adaptive teaching strategies could be beneficial in helping educators understand and respond to the diverse needs of their students, thus optimizing the learning environment for all students.