ABSTRACT

Purpose

To develop and assess psychometric properties of a disease-specific quality of life (QOL) assessment tool for patients with chronic uveitis.

Methods

The initial 42-item chronic uveitis-related QOL questionnaire (CUQOL) was developed by literature review, semi-structured interviews, and expert consultation. Further development and assessment of the CUQOL were performed using Classic Test Theory and Rasch analysis.

Results

The CUQOL version 1.0 was constructed with 28 items in five dimensions. The five subscales satisfied the requirements of unidimensionality, local independence, and threshold ordering. Cronbach’s α coefficient for overall and each scale of the CUQOL 1.0 ranged from 0.75 to 0.94, with test-retest intraclass correlation ranging from 0.95 to 0.99. The CUQOL 1.0 has satisfactory convergent validity (r = 0.41–0.82), reasonable known group validity (p < .05), and good responsiveness (p < .05).

Conclusions

The CUQOL 1.0 is reliable and vaild for evaluating the QOL of patients with chronic uveitis.

The term uveitis clinically describes inflammation of the iris, ciliary body, choroid, and adjacent structures, including the retina, vitreous, and optic nerve.Citation1,Citation2 Uveitis is a major cause of severe visual impairment and predominantly occurs in working-age individuals. Approximately 35% of patients with uveitis suffer from significant visual loss, even legal blindness,Citation3 which can have a significant impact on the quality of life (QOL). Inflammation lasting more than 3 months is defined as chronic uveitis. Persistent ocular inflammation in patients with chronic uveitis can lead to severe ocular complications, including cataract, glaucoma, and macular edema. Patients with chronic uveitis are usually treated with systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biological agents to reduce intraocular inflammation. The long-term use of these medications produces a series of side effects, such as infections, liver damage, and kidney failure. Therefore, the visual impairment caused by uveitis, and its complications, the side effects of systemic therapy, and the economic burden due to the high cost of treatment and loss of working ability have a significant impact on the patient’s physical, psychological, and social functions, resulting in a decrease in the QOL of chronic uveitis sufferers.Citation3 Thus, determining how chronic uveitis impairs patients’ QOL is essential for choosing the most appropriate therapy, increasing patients’ compliance with treatment, and improving patients’ QOL.

Although research on the QOL of uveitis patients has been presented in the literature,Citation4–7 all these studies used generic vision-related quality of life (VR-QOL) or health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) questionnaires, such as the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, the National Eye Institute Vision Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25), and the Low-Vision Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. These may underestimate the impact of chronic uveitis on patients’ daily life, because they fail to take into account disease-specific aspects, particularly psychological disorders caused by a complicated disease course and long-term therapeutic process. Furthermore, there are no specific instruments for measuring the QOL of patients with chronic uveitis.

Therefore, we here developed and evaluated psychometric properties of a new instrument, the Chronic Uveitis-related Quality of Life Questionnaire (CUQOL), for Chinese patients with chronic uveitis, for the sensitive and specific evaluation of the multifaceted effects of chronic uveitis on patients’ daily lives.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Participants were recruited from a tertiary uveitis service at Tianjin Medical University Eye Hospital (TMUEH), Tianjin, China, between February 2021 and May 2022, for the development and validation phases of the new questionnaire. The inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) a clinical diagnosis of uveitis according to the diagnostic criteria of the International Uveitis Study Group,Citation1,Citation2 (3) disease duration longer than 3 months, and (4) with or without other ocular complications associated with uveitis,Citation2 such as complicated cataract, secondary glaucoma, and retinal detachment among others. Patients with other ocular diseases that could affect visual acuity (e.g., primary glaucoma, age-related cataract, and diabetic retinopathy) and other major physical, neurological, or psychiatric illnesses were excluded.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the TMUEH (Ethics approval: February 10, 2021, Ethics ID: 2021KY(L)-07). All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and were assured that their comments and answers would remain confidential.

Stage 1: Development of the CUQOL

We comprehensively reviewed the literature and considered existing VR-QOL and HR-QOL questionnaires to generate an overview of the areas of life impacted by chronic uveitis. An in-depth semi-structured interview was conducted with eligible patients to determine how chronic uveitis affects their QOL in multiple domains. The participants were asked open-ended questions such as “How does uveitis bother you?” “How does low vision affect your daily life?” and “How does impaired vision affect your relationships with other individuals?” After interviewing 20 patients (mean age, 42.3 ± 9.0 years; 9 men and 11 women), thematic saturation was reached as no new themes emerged.Citation8 These processes generated 47 questionnaire items.

Subsequently, a panel of experts discussed the importance and appropriateness of each item. Based on the experts’ suggestions, we drafted a 42-item preliminary version of the CUQOL. We used a 5-point degree scale (“Very severe,” “Severe,” “Moderate,” “Mild,” and “None”) for responses on each questionnaire.

To confirm the face and content validity of the 42-item CUQOL, 30 eligible participants (mean age, 39.3 ± 9.1 years; 15 men and 17 women) were invited to complete the preliminary questionnaire. Subsequently, the participants were interviewed regarding the comprehensiveness of the sentences, clarity of instructions, and completion time of the questionnaire. Furthermore, they were asked whether the questionnaire covered all the major aspects relevant to their chronic uveitis-related QOL. Based on the participants’ feedback, we eliminated those items considered redundant, ambiguous, or difficult to understand and created a second version of the CUQOL with 36 items.

To reduce the number of items and determine the factor structure, statistical testing based on item analysis and factor analysis was performed. It has been reported that the sample size should be at least 5–10 times the number of questionnaire items to support factor analyses.Citation9 Of the 372 eligible individuals, a total of 340 participants patients were given the 36-item CUQOL to complete during the clinic visit (72.8% response rate). We excluded 16 invalid questionnaires with incomplete data, leaving 322 respondents for the analyses. For analysis, “Always” or “Very severe” responses were scored as 1, “Often” or “Severe” as 2, “Sometimes” or “Moderate” as 3, “Rare” or “Mild” as 2, and “Never” or “None” as 1. Item analysis was performed by calculating the correlation between each item and the whole scale score. Items that showed low item-total score correlations (r < 0.3) were deleted, as this demonstrated that they made minimal contribution to the underlying scale. Additionally, the percentage of missing values and the distribution of the items were identified. Items with high levels of missing data (> 20%) were considered for deletion, and items with >50% floor or ceiling effects were also removed.

Exploratory factor analysis was applied to determine the factor structure of the CUQOL. We extracted the factors using varimax rotation with an eigen value cut off point > 1. The number of factors was selected by considering a screen test, as well as the possibility of a theoretical interpretation. Items with factor loadings < 0.4 and cross-loadings < 0.1 in absolute value were excluded.Citation10

Stage 2: Evaluation of psychometric properties

Rasch analysis

Rasch analysis was conducted using the Andrich rating scale model with Winsteps software, version 3.66.0. Rasch analysis encompasses probabilistic mathematical modelling to estimate the relative item difficulty and person ability along a common invariant interval-level scale in logits, thereby allowing an easy comparison of measures. Rasch analysis also provides substantial insight into the psychometric properties of the scale, including unidimensionality, local dependency, response category functioning, item fit to the model, and differential item functioning (DIF). Unidimensionality can be considered if the principal component analysis results show raw unexplained variance by the first contrast with an eigenvalue less than 2.0.Citation11 The residual correlations between items should be below 0.30.Citation12 The stringent criterion for fit statistics is above 0.70 and below 1.30.Citation13 Small or absent DIF was defined as a difference in item measure of less than 0.50 logits, minimal DIF as 0.50 to 1.00 logits, and notable DIF as greater than 1.00 logits.Citation14 Measurement precision could be estimated by person separation index (PSI). A PSI of at least 2.00 indicates that the instrument can distinguish different levels of person ability.Citation15 The Rasch analysis results may help us to comprehensively understand whether these items are suitable for the targeted scale and whether there are any potential disadvantages. Furthermore, we created conversion tools to convert raw CUQOL responses into Rasch-scaled interval scores. Higher logits scores represent better Symptoms, Visual Function, Concern about Disease and Treatment, Anxiety and Depression, and Social Function.

Reliability

The internal consistency of the CUQOL was tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha, with values α > 0.7 considered acceptable.Citation16 To evaluate the test-retest reliability, a subset of 180 participants was asked to complete the CUQOL twice, one week apart. A sample size of > 50 was desired for the test-retest reliability study.Citation17 The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) between the first and second measurements were analyzed, with values > 0.7 regarded as acceptable.Citation18

Validity

To demonstrate convergent validity, participants were asked to complete the NEI-VFQ-25 immediately after completing the CUQOL. We then calculated the Spearman’s rank correlation between the scale scores of the CUQOL and NEI-VFQ-25. The NEI-VFQ-25 is a widely used instrument for evaluating visual function and its related QOL.Citation19–22 Several studies demonstrated that the Rasch-based NEI-VFQ-25 contains fewer validated subscales, with higher reliability and validity.Citation23–25 Therefore, the NEI-VFQ-25 score was calculated using the Rasch-transformed scores based on the long-form visual scale (LFVFS 25) and the long-form socio-emotional scale (LFSES 25).Citation24

Known group validity was evaluated by testing the CUQOL’s ability to discriminate between groups of patients known to differ by clinical characteristics. Patients’ clinical data were obtained from medical records. The details of clinical uveitis, including laterality, anatomical location, activity, relapse, and complications, were determined according to Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature criteria.Citation2 The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test for statistical differences between the groups.

Responsiveness

To assess the responsiveness, 104 consecutively followed-up patients were asked to complete the questionnaire again six months after the first survey. The scores before and six months after the survey were compared using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26.0; IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Group comparisons were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U, Kruskal–Wallis, and Wilcoxon tests. Correlations were analyzed using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Study subjects

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 322 participants are presented in . A total of 201 participants (62.4%) were aged between 30 and 50 years, and 166 (51.6%) were women. The majority of patients (64.6%) presented with panuveitis, 213 (66.1%) had bilateral involvement, and 131 (40.7%) experienced recurrence.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants (n = 322).

Stage 1: Development of the CUQOL

According to the results of the item analysis of 36 items, two items with an item-total correlation coefficient of less than 0.3 and two items with >50% ceiling effects were deleted. Factor analysis was performed on the remaining 32 items, revealing that three items with factor loadings < 0.4 and one item with cross-loadings < 0.1 were removed. Finally, we obtained the CUQOL version 1.0 including 28 items. The CUQOL 1.0 contained five factors: symptoms (5 items), visual function (7 items), concern about disease and treatment (5 items), anxiety and depression (6 items), and social function (5 items), which accounted for 66.21% of the total variance. The factor loads of items located in each factor varied from 0.45 to 0.84 ().

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of the Chronic Uveitis-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire version 1.0 (CUQOL 1.0).

Stage 2: Evaluation of psychometric properties

Rasch analysis

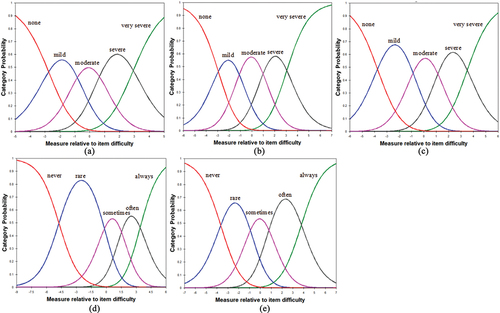

presents the results of the analyses for unidimensionality and local item dependence for the five subscales of the CUQOL 1.0, which satisfy the assumption of the Rasch model. As shown in the category probability curve (), the response option thresholds were ordered for all the items of the CUQOL 1.0. The PSIs for the five subscales were between 1.40 and 2.53 (). Three items (Item 9, Item 10, and Item 11) had fit mean square values below 0.7 and four items (Item 3, Item 16, Item 14, and Item 25) had DIF contrast greater than 0.5 logits by gender. However, we retained these items due to their clinical significance. Furthermore, we created an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Inc.) to convert raw CUQOL responses into Rasch measurement estimates (Supplementary material A).

Figure 1. (a) Category probability curves (CPC) of five response categories for Symptoms subscale. (b) CPC for Visual Function subscale. (c) CPC for Concern about Disease and Treatment subscale. (d) CPC for Emotional subscale. (e) CPC for Social function subscale.

Table 3. Dimensionality and Local Dependence Analysis of the subscales of the Chronic Uveitis-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire version 1.0 (CUQOL 1.0).

Table 4. Summary of psychometric analysis of the Chronic Uveitis-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire version 1.0 (CUQOL 1.0).

Reliability

Cronbach’s α coefficient for CUQOL 1.0 was 0.94, and that for the five subscales ranged from 0.75 to 0.91, which confirmed a high degree of internal consistency. One hundred and fifty-eight completed questionnaires were returned one week after the first evaluation (validity rate 95.8%). The test–retest reliability was satisfactory for the total scale and five subscales of the CUQOL 1.0 (ICC = 0.95–0.99, all P < .01) ()

Validity

presents the correlations between the CUQOL 1.0 and the NEI-VFQ-25. The summary score and each subscale score of the CUQOL 1.0 were moderately to highly correlated with LFVFS 25 and LFSES 25 (r = 0.41–0.82, all P < .01). This indicated an acceptable convergent validity.

Table 5. Correlations between the Chronic Uveitis-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire version 1.0 (CUQOL 1.0) scores and the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25).

There was a significant difference in the CUQOL 1.0 total score and each subscale score between groups with varying degrees of vision loss in the better- and worse-seeing eye (all P < .001) (). Patients with unilateral eye involvement had lower overall and subscales scores than those with bilateral involvement (all P < .005). The overall and subscales scores of the CUQOL 1.0 differed significantly among different anatomic location groups (all P < .01). These findings demonstrated an excellent known group validity.

Responsiveness

The responsiveness was confirmed by the significant difference in the overall and subscales scores of the CUQOL 1.0 between the first survey and six months later (P < .02) (). Meanwhile, a six-month follow-up survey showed significant improvements in the best-corrected visual acuity of the better- and worse-seeing eyes (both P < .001). Over a six-month period, only 6 of the 107 patients experienced recurrence, and most had well-controlled ocular inflammation.

Table 6. Responsiveness of the Chronic Uveitis-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire version 1.0 (CUQOL 1.0) in 107 patients.

Discussion

In the current study, we adopted two methods, classical test theory (CTT) and Rasch analysis, to develop and assess comprehensively the psychometric properties of a new scale for specific measurement of the QOL in Chinese patients with chronic uveitis. The CUQOL 1.0 consisted of 28 items and was divided into five dimensions: symptoms (5 items), visual function (7 items), concern about disease and treatment (5 items), anxiety and depression (6 items), and social function (5 items). The results of CTT-based psychometric analysis indicate that the CUQOL 1.0 have excellent stability with high internal consistency and good test–retest reliability over a one-week period. Moreover, the whole scale and each subscale of the 28-item CUQOL were correlated significantly with LFVFS 25 and LFSES 25, confirming a good convergent validity. The known group validity was verified from the finding that each subscale score and the total score of the CUQOL were significantly different between clinically distinct subgroups. Meanwhile, the results of our survey demonstrated that patients with more severe conditions (such as bilateral involvement, posterior uveitis or panuveitis, worse visual acuity, and recurrence) were more likely to have worse QOL.

The results of Rasch analysis more robustly demonstrate the psychometric properties of the CUQOL 1.0 compared to CTT. Rasch analysis is not sample- or test-dependent as CTT,Citation26,Citation27 resulting in more reliable and meaningful parameter estimates. The five subscales of the CUQOL 1.0 all meet the assumption of unidimensionality, and there were no high levels of local dependence between items. The category probability curves demonstrated that these five response categories (for frequency from “never” to “always” or for degree from “none” to “very severe”) were ordered in five subscales, indicating that participants were able to distinguish the response options. The PSIs for these subscales, except for the symptom subscale of the CUQOL 1.0, roughly satisfied the criterion. For the symptom subscale, the low PSI reflected limited ability to differentiate the patients with varying degrees of symptom severity. Indeed, the severity of symptoms is extremely susceptible to change due to medication intake, emotion, and other factors. Some patients were unable to perfectly match their intensity of symptoms with response options of items, which may contribute to undesirable outcomes, as reported previously.Citation28,Citation29 Moreover, there were three overfitting items (Item 9, Item 10, and Item 11) and four items (Item 3, Item 16, Item 14, and Item 25) with minimal DIF. Considering their clinical significance, if we delete these items solely to obtain statistical fit to the model, content validity can be affected, leading to an underrepresentation of the construct.Citation30,Citation31 Additionally, since the developed scale is at an early stage of development, we would like to retain as many items as possible to provide more valuable information to other researchers. For these reasons, we retained the above items with poor Rasch-based performance in the CUQOL 1.0. However, we acknowledge that Rasch analysis results clearly show the potential shortcomings of CUQOL 1.0.

To our knowledge, no previous questionnaire has been developed to measure QOL specifically in patients with chronic uveitis, in contrast to the existing generic VR-QOL or HR-QOL questionnaires that have been used to assess the QOL of patients with chronic uveitis in the literature. The strength of the CUQOL is that each item was specifically designed for patients with chronic uveitis and could be more sensitive in evaluating the impact of chronic uveitis on the patient’s QOL. In particular, for the assessment of psychological health, we designed items that are highly correlated with chronic uveitis to reflect the impact of this disease on QOL more accurately, and other psychological assessment tools are difficult to exclude other confounding factors, such as daily work and study pressure. There are no existing generic instruments that could encompass many aspects that influence the QOL of patients with chronic uveitis. Most studies used a combination of several generic questionnaires to evaluate patients’ overall QOL.Citation4,Citation32,Citation33 Thus, it would be difficult and time-consuming for patients with low vision to complete these scales. We have designed a single CUQOL that covers comprehensively the range of QOL issues relevant to chronic uveitis, and it can be completed within 10 minutes, which improves the efficiency of the evaluation remarkably.

There are some major limitations in our study. First, since our hospital is a tertiary referral center, our samples may have been biased toward patients with more serious disease and under-represented certain socioeconomic and cultural groups. Therefore, it is possible that we would have selected different items if we had tested the preliminary questionnaires with other patient populations. Second, we have provided Rasch-based scoring conversion tools for CUQOL 1.0, which were derived from our study population. Since populations vary, it may be preferable to implement Rasch measurement properties by actually performing Rasch analysis. In addition, some items with acceptable CTT-based psychometric properties but poor Rasch-based performance were included in the CUQOL 1.0 due to their clinical importance. Therefore, these possible weaknesses of the CUQOL 1.0 should be considered when using it to assess QOL in chronic uveitis patients. As Smith stated: “The psychometric development and refinement of a scale is a necessarily iterative process,”Citation34 in our following study, we plan to further revise these potential flaws, as well as form a truly multi-dimensional QoL instrument for patients with chronic uveitis, by administering the CUQOL to a larger number of patients with chronic uveitis in multiple clinical centers. In the future, the CUQOL could also be translated and cross-culturally adapted to other countries.

In conclusion, the CUQOL 1.0 is a valuable measurement instrument to characterize the impact of chronic uveitis on patients’ daily lives in routine clinical practice and research. A combination of clinical examination findings and patient perceptions of QOL may assist in clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgment

The authors want to thank all patients for valuable contribution to the questionnaire study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bloch-Michel E, Nussenblatt RB. International Uveitis Study Group recommendations for the evaluation of intraocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:234–235. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)74235-7.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–516.

- Qian Y, Glaser T, Esterberg E, et al. Depression and visual functioning in patients with ocular inflammatory disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:370–378 e372. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.028.

- Schiffman RM, Jacobsen G, Whitcup SM. Visual functioning and general health status in patients with uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:841–849. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.6.841.

- Miserocchi E, Modorati G, Mosconi P, et al. Quality of life in patients with uveitis on chronic systemic immunosuppressive treatment. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:297–304. doi:10.3109/09273941003637510.

- de Smet MD, Taylor SR, Bodaghi B, et al. Understanding uveitis: the impact of research on visual outcomes. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:452–470. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.06.005.

- Jalil A, Yin K, Coyle L, et al. Vision-related quality of life and employment status in patients with uveitis of working age: a prospective study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20:262–265. doi:10.3109/09273948.2012.684420.

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

- Hou X, Zhu D, Zheng M. Clinical nursing faculty competence inventory - development and psychometric testing. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:1109–1117. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05520.x.

- Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, et al. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149.

- Gothwal VK, Bagga DK. Vision and quality of life index: validation of the Indian version using Rasch analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4871–4881. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-11892.

- Klassen AF, Cano SJ, East CA, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q scales for patients undergoing rhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18:27–35. doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2015.1445.

- Pesudovs K, Burr JM, Harley C, et al. The development, assessment, and selection of questionnaires. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84:663–674. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e318141fe75.

- Khadka J, Huang J, Mollazadegan K, et al. Translation, cultural adaptation, and Rasch analysis of the visual function (VF-14) questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4413–4420. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-14017.

- Khadka J, Pesudovs K, McAlinden C, et al. Reengineering the glaucoma quality of life-15 questionnaire with rasch analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:6971–6977. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-7423.

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555.

- Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012.

- Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL. Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12:142S–158S. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(05)80019-4.

- Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute visual function questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–1058. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050.

- Mazhar K, Varma R, Choudhury F, et al. Severity of diabetic retinopathy and health-related quality of life: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:649–655. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.003.

- Bertrand PJ, Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, et al. Quality of life in patients with uveitis: data from the ULISSE study (Uveitis: cLInical and medico-economic evaluation of a standardised strategy for the Etiological diagnosis). Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105:935–940. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-315862.

- Samuelson TW, Singh IP, Williamson BK, et al. Quality of life in primary open-angle glaucoma and cataract: an analysis of VFQ-25 and OSDI from the iStent inject(R) pivotal trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;229:220–229. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.007.

- Marella M, Pesudovs K, Keeffe JE, et al. The psychometric validity of the NEI VFQ-25 for use in a low-vision population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2878–2884. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-4494.

- Pesudovs K, Gothwal VK, Wright T, et al. Remediating serious flaws in the National Eye Institute visual function questionnaire. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:718–732. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.11.019.

- Petrillo J, Bressler NM, Lamoureux E, et al. Development of a new Rasch-based scoring algorithm for the National Eye Institute visual functioning questionnaire to improve its interpretability. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:157. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0726-5.

- Bhakta B, Tennant A, Horton M, et al. Using item response theory to explore the psychometric properties of extended matching questions examination in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:9. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-5-9.

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Psychometric evaluation of a knowledge based examination using Rasch analysis: an illustrative guide: AMEE guide no. 72. Med Teach. 2013;35:e838–848. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.737488.

- Begley CG, Chalmers RL, Mitchell GL, et al. Characterization of ocular surface symptoms from optometric practices in North America. Cornea. 2001;20:610–618. doi:10.1097/00003226-200108000-00011.

- Johnson ME, Murphy PJ. Measurement of ocular surface irritation on a linear interval scale with the ocular comfort index. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4451–4458. doi:10.1167/iovs.06-1253.

- Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35:382–385. doi:10.1097/00006199-198611000-00017.

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Anderson KG. On the sins of short-form development. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:102–111. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.102.

- Niemeyer KM, Gonzales JA, Rathinam SR, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes from a randomized clinical trial comparing antimetabolites for intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;179:10–17. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.04.003.

- Kelly NK, Chattopadhyay A, Rathinam SR, et al. Health- and vision-related quality of life in a randomized controlled trial comparing methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil for uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:1337–1345. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.02.024.

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM. Methodological considerations in the refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:300–308. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.300.