ABSTRACT

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome is a disorder that was originally described in 1975. The syndrome, although diagnosed in all age ranges, is more frequently reported in pediatric patients. Diagnosis can be difficult, and its clinical spectrum is still being defined. In this article, we review the epidemiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, clinical findings, prognosis, and treatment of both the ocular and renal disease. We comment on the current difficulties in diagnosis and study of the disease, its expanding clinical spectrum, and treatment strategies in pediatric patients.

Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) is a syndrome first identified by Dobrin et al. in 1975, who described two teenage girls with renal failure due to eosinophilic interstitial nephritis, bone marrow granulomas, hypergammaglobulinemia, and bilateral anterior uveitis.Citation1 Since this initial description, TINU has been increasingly recognized as a prominent etiology of pediatric uveitis with one larger series estimating a prevalence of 32% in patients under 20 with bilateral acute anterior uveitis.Citation2 However, despite increased recognition, there remains great difficulty in accurately diagnosing the syndrome, which poses problems in appropriately treating patients and in studying the disease. Ultimately, the syndrome may go unrecognized, or the diagnosis may be delayed. Prompt diagnosis is important as early recognition of occult kidney disease may improve outcomes.Citation3 In this article, we review TINU in the pediatric population with an emphasis on the expanding manifestations of disease phenotype, testing and diagnosis strategies, and treatment approaches.

Materials and methods

The pubmed.gov database was queried between April and July of 2023. Pertinent articles were chosen based on relevance to the subject (with descriptions of both kidney and ocular disease) as well as clinical studies that included a proportion of children as study subjects (at least one patient). Keywords searched included “tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis,” “children,” and “pediatric.” Articles were limited to the English language, and all years were included. Both clinical studies and review articles were included; single case reports were excluded. Reference lists from articles were additionally reviewed to identify pertinent articles to the subject. Articles were initially screened by two authors (PHL, TMJ) and approved for final inclusion by all authors.

Diagnostic criteria: Evolving disease spectrum

Diagnostic criteria are necessary to standardize a clinical syndrome and improve recognition, however the current proposed criteria for TINU, although helpful, are problematic. Mandeville et al. proposed the first diagnostic criteria in 2001 based on a review of 133 cases ().Citation4 This series’ population was mainly pediatric patients (average age of diagnosis 15) with a 3:1 female predominance. The majority of cases (80%) were non-granulomatous anterior uveitis. Ocular disease preceded kidney disease in 20% and followed kidney disease in 65%. The Mandeville criteria are based on this initial description, and although helpful, may miss disease that does not match this original description; furthermore, it’s classification of “possible”, “probable”, and “definite” TINU introduces the potential for ambiguity and misclassification.

Table 1. Comparison of Mandeville et al. and SUN working group clinical criteria for TINU.

The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) developed new diagnostic criteria for TINU in 2021.Citation5 The SUN criteria are similar, although simpler, than Mandeville et al.’s and eliminate the categories of “possible” and “probable” as well as the symptoms required for a diagnosis of TIN (). Ultimately, both are classifications based on a clinical phenotype of sudden-onset bilateral anterior uveitis in combination with TIN. This is problematic, as will be discussed in subsequent sections, as the spectrum of disease is expanding with many reports of posterior manifestations and asymptomatic/insidious uveitis.Citation6,Citation7

Both classifications rely on a diagnosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) either via kidney biopsy or a combination of clinical and laboratory investigations. Urine beta-2 microglobulin and serum creatinine have been studied specifically in the pediatric population and were found to have high sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV) for detecting cases of TINU; however, the methodology of the study is debatable given that the diagnosis of TINU in the study relied on the tests in question.Citation8 Urine beta-2 microglobulin has the advantage that it may stay elevated for a longer period after a kidney insult even if serum creatinine has returned to normal.Citation9 These markers are not specific to TINU and can be elevated in the setting of TIN of any etiology.

TINU is, by definition, a diagnosis of exclusion. There are other etiologies of uveitis that can cause TIN and need to be excluded; most notable is sarcoidosis, which can present with TIN and ocular involvement. Indeed, some have postulated that both sarcoidosis and some cases of TINU are a variant of the same disease process.Citation10 Even in Dobrin et al.’s initial 1975 report, the authors devoted a portion of their conclusions to differentiating between their proposed new syndrome and sarcoidosis given the granulomatous disease of their two patients. The prevalence of kidney involvement in sarcoidosis is not well understood, with a recent review noting a wide range (1% to 30–50%) of reported kidney involvement.Citation11 Ultimately, sarcoidosis in children and isolated sarcoid kidney involvement without other findings of widespread granulomatous disease (e.g., hilar adenopathy on chest imaging) is rare.Citation12 Sarcoidosis is characterized by granulomatous disease, whereas granulomatous uveitis and histologic evidence of granulomas appears to be present in the minority of TINU patients. Indeed, the SUN criteria specifically excludes patients with a tissue diagnosis showing non-caseating granulomata—which notably would exclude Dobrin et al.’s original cases from the definition, and 13% of Mandeville et al.’s patients that had kidney biopsies with granulomas.Citation4 Perhaps, some cases in the literature that are attributed to TINU are really due to underlying sarcoidosis and vice versa. Ultimately, one should have an increased suspicion for sarcoidosis in cases of TINU characterized by granulomatous disease.

The previous discussion demonstrates the difficulty in disease definition. Both classification schemes are helpful but are ultimately based on clinical phenotype rather than a distinct entity with an associated specific diagnostic test. Therefore, it is important to recognize that current literature is limited by our ability to definitively diagnose and detect disease. There is likely underreporting of disease due to a lack of detection of kidney involvement when uveitis is diagnosed. There are also likely some cases of “possible” or “probable” TINU reported in the literature that are truly not part of the disease spectrum. The search for a more definitive marker of TINU is ongoing. One area of promising research includes HLA allele associations which will be discussed in a subsequent section.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Although the only objective measure available, prevalence studies need to be considered in the context of potential underdiagnosis discussed above. In a 2017 systematic review, Okafor et al. compiled survey studies of reported uveitis services and noted a TINU prevalence anywhere between <0.1% to 2% in the “all age” cohorts, and a higher range of 1.12% to 2.28% in four pediatric specific cohorts.Citation13 This systemic review, however, included 13 surveys in which no cases of TINU were reported, which would lead to suspicion of underdiagnosis in these cohorts. Mackensen et al. noted a prevalence of 1.7% of all patients evaluated at their uveitis service from 1985 through 2005 (33/1985 patients).Citation2 Of patients presenting with bilateral sudden onset anterior uveitis, TINU was diagnosed in 10% (32/316). Furthermore, in patients 20 and younger, TINU represented 32% (20/62) of patients with bilateral sudden-onset anterior uveitis. However, patients with a diagnosis of TIN may have a significantly increased risk of uveitis development that may be asymptomatic and thus not recognized in uveitis cohort studies. A Finnish study in the nephrology literature noted out of their cohort of 26 biopsy-proven TIN in children, uveitis was diagnosed in 12/26 (46%) and was asymptomatic in 7/12 (58%) of these patients.Citation14 A prospective study of the same population noted a uveitis diagnosis rate of 84% (16/19) among TIN patients when screened at the onset of TIN, 3-months, and 6-months after diagnosis.Citation6

No racial predilection has been identified. Ohguro et al. noted a prevalence of 0.4% in a Japanese population (15 out of 3,830 patients); Jones noted a prevalence of 0.2% in a United Kingdom population (7 out of 3,0000 patients).Citation15,Citation16

Lastly, it should be noted as there are few recent cases and series published linking the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic to a diagnosis of TINU.Citation17 Although there may be a viral trigger for the disease, this association may be due to an increased recognition of the disorder rather than an actual surge in the disease.Citation17,Citation18

Age

The disease is more common in children. Most studies are heavily weighted to pediatric patients; however, TINU has been reported in all ages. Even Mandeville et al.’s initial review had adult patients with an age range of 9–74 years (median age 15 at diagnosis).Citation4 Mackensen et al.’s 2007 review also had a median age of 15 at diagnosis (range 6–64 years).Citation2 Goda et al. noted that TINU was the second most common uveitis diagnosis in children in their cohort and noted a bimodal age distribution with one peak at ages 11 to 20 years and a second at 31 to 35 years of age.Citation19 Other studies have noted a similar bimodal age distribution.Citation20 Cao et al. noted an older bimodal distribution among 10 patients who presented with posterior segment manifestations (10–46 years and 77–83 years).Citation21 Some more recent cohorts have a significantly older mean age of presentation. Yang et al.’s mean age of onset was 41.1 years (range 10 to 66 years).Citation20 A recent 2022 cohort of Spanish and Portuguese patients noted a slightly older mean age of diagnosis of 25 with a range of 14.8 to 49.5 years.Citation22 Pichi et al.’s cohort had a median age at diagnosis of 16 (range 9 to 50), more consistent with previous earlier studies.Citation23

Gender

Mandeville et al.’s original series noted a female predominance, but subsequent studies show varying gender compositions. Mackensen et al.’s series noted a male predominance with males representing 60% of all patients and 70% of patients under 20.Citation2 Since then, gender within cohorts has been mixed.Citation6,Citation22–24 A recent large systematic review published in the nephrology literature compiled 233 articles including 592 TINU cases and demonstrated a female predominance of 65%.Citation25 Furthermore, there may be an association between age of onset and gender with females presenting later than males. Mackensen et al. noted the median age for male patients to be 15 years versus 40 years in females.Citation2,Citation20 Pichi et al. and Yang et al. also noted a higher median age at diagnosis among female patients (34 years and 49 years, respectively). Paroli et al. had similar findings but with a smaller difference with a median age at diagnosis of 17.5 years in females versus 12.5 years in males.Citation24

Pathogenesis

TINU may be preceded by an infectious or pharmacologic trigger.Citation4 For instance, the syndrome has been diagnosed in patients following infection with Epstein-Barr virus, herpes zoster, toxoplasmosis, and even following insect bites.Citation4 Pharmacologic triggers have been proposed as well and include antibiotics, diuretics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.Citation12 However, these are all associations and proving causality may be impossible as pharmacologic agents are often used for the systemic symptoms of TIN. Furthermore, systemic symptoms of TIN may be confused for a preceding infection. However, it is logical that a foreign antigen may trigger an over-reactive immune response given the relationship between certain class II HLA molecules and TINU, which is discussed below.

Likely there is a genetic component as evidenced by reports of TINU occurring in siblings, twins, and within families.Citation26–29 HLA allele associations have been studied in multiple cohort studies. However, most studies are small and do not have a comparison or control group. Therefore, it is hard to draw any true conclusions. We identified four studies with samples greater than 10 patients with a comparison group.Citation30–33

Levinson et al. in 2003 reported a very high rate of HLA-DQA1 × 01, HLADQB1 × 05 and HLA-DRB1 × 01 in 18 (72%) of their TINU patients. In particular, HLA-DRB1 × 0102 had a relative risk of 167.1 for TINU when compared to a control population of North American Caucasians.Citation30 Of note, this original study had a higher rate of chronic, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis TINU patients. This group further studied these alleles in three patient groups: TINU syndrome patients, patients without TIN but with bilateral, sudden-onset anterior uveitis, and patients with interstitial nephritis alone, and showed that HLA-DRB1 × 0102 was still significantly associated with the TINU group and the sudden-onset bilateral anterior uveitis alone group, but not TIN alone.Citation31 There are two interpretations of this study. The first being that HLA-DRB1 × 0102 is specific to TINU in that it was found in both TINU patients and uveitis patients matching a TINU phenotype, but perhaps the kidney disease was mild or missed entirely. Alternatively, a second interpretation is that HLA-DRB1 × 0102 is not specific to TINU but rather to a broader uveitis phenotype that may present without TIN.

Reddy et al. further studied HLA-DRB1 × 01 in pediatric TINU patients with panuveitis and in pediatric panuveitis without kidney disease.Citation32 Their population phenotype was primarily characterized by chorioretinal lesions; 14/15 panuveitis without TIN and 3/6 TINU patients had such findings. They noted a high percentage of both HLA-DRB1 × 01 and HLA-DQB1 × 05, which they termed “TINU alleles,” in both of these populations. Again, this suggests that the HLA-DRB1 × 01 allele in particular may be associated with a broader uveitis phenotype in which the kidney is not involved, or that potentially kidney involvement was missed, and cases were inappropriately labeled as idiopathic panuveitis.

It is also important to note that both of the above studies were conducted in North American patients, and HLA associations may have significant geographic variations. A Finnish study of TINU patients found a significant association between HLA-DQA1 × 0104 (RR 6.1) and HLA-DRB1 × 14 (RR 8.2) but not HLA-DRB1 × 01 when compared with a European control group.Citation33 Other HLA associations of unknown significance appear in smaller studies that often lack control groups and include HLA-A2 and HLA-A24 in a Japanese population, and HLA-DR14 among Spanish subjects.Citation4,Citation19,Citation34 We mention these because they are often cited, however studies of this nature can be misleading; the HLA-A2 and HLA-A24 alleles are present in a high percentage in Japan and in a larger series of TINU patients were not statistically greater than the control population.Citation35 Furthermore, the study associating HLA-DR14 among Spanish patients was based on a cohort of three patients, and other studies have not found this association.Citation36

Therefore, the strongest evidence appears to associate HLA-DRB1 × 01 to a uveitis phenotype consistent with TINU at least in North American Caucasian patients and may be a helpful marker in workup of uveitis patients suspected of having TINU. However, it is still to be determined whether this is a specific marker for TINU or rather some broader disease phenotype.

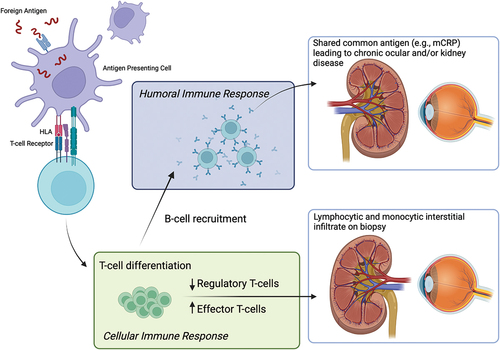

Proposed pathogenesis

The cell-mediated immune response is believed to be the primary driver of inflammation in TINU. Kidney biopsies show a primarily T-lymphocytic and monocytic interstitial infiltrate that spares the glomerulus.Citation37 Regulatory T-cells, cells that are involved in dampening the immune response, were found in a significantly lower volume in TINU patient kidney biopsies among those who developed chronic uveitis suggesting that chronic uveitis patients may have an imbalance that tips towards a proinflammatory immune state.Citation38 Patients with both TIN and TINU were further shown to have significant genetic variation in the frequency of IL-10 alleles compared with control patients.Citation39

HLA gene associations also support a cell-mediated immune response as Class II HLA molecules are involved in antigen presentation to prime T-cells. This suggests molecular mimicry as a potential driver of inflammation, in which a foreign antigen primes T-cells against both ocular and kidney tissue. This is further supported by the potential infectious preceding trigger that is associated with TINU cases.

Although kidney biopsies usually do not show immune complex deposition, there is evidence to suggest that humoral immunity likely also plays a role.Citation40 Shimazaki et al. found that serum from patients with TINU reacted against healthy kidney, retinal, and ciliary tissue.Citation41 Abed et al. found autoantibodies in a 15-year-old male with TINU that were reactive against human renal tubular epithelium tissue and murine iris and ciliary body.Citation42 Anti-monomeric C-reactive protein (anti-mCRP) was found in 9/9 TINU patients in one study, a significantly higher proportion than found in a uveitis control group and in patients with other autoimmune disorders.Citation26 Additionally, mCRP was found in kidney biopsies and in human iris/ciliary body tissue. The presence of the anti-mCRP antibody was found to be a risk factor for the development of chronic uveitis in a cohort of Chinese adult TINU patients (OR 14.7).Citation43 However, it is unclear if this antibody is a driver of disease or merely a marker of disease activity.

Taken together, it is reasonable to hypothesize that a foreign antigen, such as an infectious agent, may prime T-cells against ocular and kidney tissues with subsequent development of autoantibodies leading to continued chronic inflammation ().

Clinical findings

Mandeville et al.’s original series defined a clinical phenotype of sudden-onset bilateral anterior uveitis, which was noted in 80% of their cases; however, this series did have several patients with posterior findings such as chorioretinitis (3 patients), neovascularization of the optic disc (1 patient), and retinal vasculitis (2 patients).Citation4 Since then, there have been several reports documenting posterior findings, an insidious onset of uveitis, and granulomatous findings. Although the majority of cases published still heavily favor bilateral sudden-onset anterior uveitis, this should be interpreted in the context of the current diagnostic criteria that requires bilateral anterior uveitis for a definite diagnosis. As discussed above, these diagnostic criteria are problematic and may not capture the full spectrum of disease.

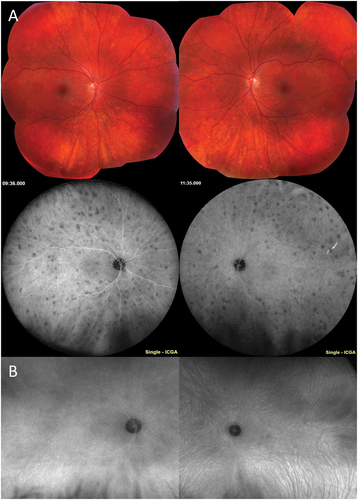

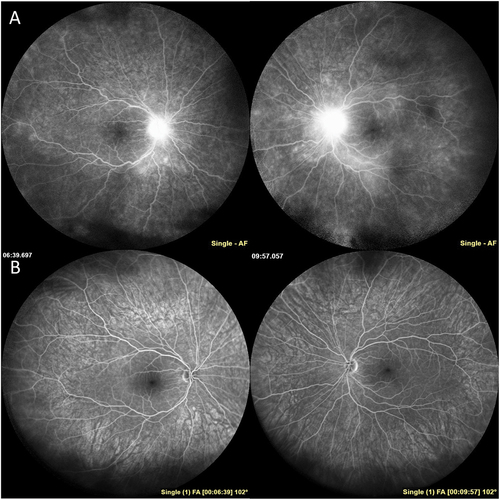

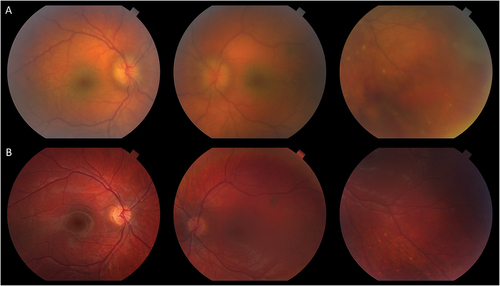

Koreishi et al. noted 11/17 (65%) of their TINU cohort (12/17 pediatric patients) developed posterior segment findings including multifocal choroidal lesions (3/11), optic disc edema (7/11), macular edema (4/11), choroidal neovascular membrane (3/11), retinal vasculitis (2/11), optic disc neovascularization (1/11), and posterior scleritis (1/11).Citation7 Takemoto et al. also reported two children with TINU who developed choroidal neovascularization—although both of their patients were diagnosed as “probable” TINU based on elevated urine beta-2 microglobulin, but no other workup was reported.Citation44 Paroli et al. noted 40% of their cohort of 21 patients (60% pediatric) had posterior, intermediate or panuveitis, although there was limited description of specific findings.Citation24 Sobolewska et al. noted 3/9 patients with intermediate uveitis and 1/9 with panuveitis.Citation45 Examples of choroidal inflammation, retinal vascular inflammation, and inflammatory neovascularization in TINU are demonstrated in .

Figure 2. Choroidal inflammation in TINU. A 16-year-old male was referred after three months of bilateral anterior uveitis following a febrile illness. On first visit to the uveitis clinic, he had 2+ anterior chamber (AC) and 2+ vitreous cell with few snowballs in the right eye. Posterior examination showed areas of subtle small choroidal lesions throughout both eyes (A) with few small pigmented atrophic choroidal lesions inferiorly. ICGA demonstrated many small hypofluorescent spots throughout both eyes more prominent than seen clinically. Workup was only notable for elevated urine beta-2 microglobulin; sarcoidosis workup was unrevealing. In addition to topical prednisolone, the patient was treated with a course of oral prednisone and transitioned to adalimumab with quiescence of disease. Follow-up ICGA (B) nine months after starting adalimumab showed resolution of hypofluorescent lesions.

Figure 3. Retinal vascular inflammation in TINU. A 15-year-old male was referred for anterior and intermediate uveitis for six months, treated with topical prednisolone and intravitreal triamcinolone. The patient noted upper respiratory tract infection one month prior to ocular symptoms. On first visit at the uveitis clinic, the patient had 3+ anterior chamber cell and 2+ anterior vitreous cell, 1+ haze, and snowballs in both eyes. The posterior examination was notable for hyperemic optic nerves and few pigmented small choroidal lesions. Fluorescein angiography demonstrated diffuse small vessel vasculitis, angiographic cystoid macular edema, and disc leakage (A). Workup was notable for elevated urine beta-2 microglobulin. Work up for sarcoidosis (ACE, lysozyme, chest x-ray) was unremarkable. The patient was treated with a course of prednisone and transitioned to adalimumab with quiescence of inflammation and resolution of vasculitis (B).

Figure 4. Inflammatory neovascularization of the disc in TINU. A 10-year-old boy was referred for anterior uveitis that developed three months after biopsy proven severe tubulointerstitial nephritis. On first examination at the uveitis clinic, the patient had 4+ anterior chamber cell, 3+ anterior vitreous cell, and 2+ haze with snowballs in both eyes. The optic nerves were edematous with fine neovascularization of both nerves (A). There were small chorioretinal lesions in the periphery of both eyes and vitreous hemorrhage in the left eye (A). The patient was treated with a course of oral prednisone and transitioned to methotrexate and adalimumab therapy with improvement in inflammation and resolution of inflammatory neovascularization and disc edema (B).

Imaging plays an important role in diagnosing posterior uveitis and following response to treatment. Cao et al. noted a high proportion of posterior segment findings in their review of 10 patients (3 pediatric) with TINU who received ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (UWF-FA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Specifically, 19/20 eyes had exam abnormalities including vitreous cell (55%), snowballs or snowbanks (25%), vascular sheathing (10%), and optic disc edema (15%). The eye that did not have posterior segment findings on exam had disc leakage on UWF-FA.Citation21,Citation46 On UWF-FA, there was a noted 50% prevalence of vascular leakage and 35% prevalence of macular edema on OCT. Interestingly, on follow-up FA, 4 eyes (22.2%) developed vascular leakage and 2 eyes (11.1%) developed peripheral nonperfusion.Citation21 Yang et al. noted peripheral vascular leakage on UWF-FA in 22/26 eyes of which only 13/26 eyes had findings of active inflammation on clinical exam.Citation20 Of note, this study had a much older patient population (average age 41.1 years with 6/13 patients being pediatric). These two cohorts, although retrospective and mainly only studying patients with posterior segment abnormalities, demonstrate the potential need for imaging to follow posterior segment inflammation in TINU patients.

Uveitis is generally thought to develop two months prior to and up to 14 months after kidney disease.Citation2,Citation4 However, this is based on the ophthalmology literature and is only as accurate as our ability to detect both manifestations. When studying patients prospectively with TIN who were screened for uveitis, some 84% of TIN patients (16/19) developed uveitis, with 50% (8/16) having no ocular symptoms.Citation6 Patients were treated for TIN with oral corticosteroids. This raises the possibility that there may be a group of TINU patients whose uveitis is masked by treatment for TIN or who present later after the kidney disease has resolved. Alternatively, systemic treatment of symptomatic uveitis may mask the development of kidney disease.

Lastly, an interesting phenotype of small chorioretinal lesions in TINU patients has been reported.Citation7,Citation32,Citation47 Reddy et al. also associated this phenotype with HLA-DRB1 × 01 in patients both with and without TIN.Citation32 Furthermore, a recent study on TINU looked at indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) in three TINU patients (ages 9, 10, and 33 years) and found subclinical hypofluorescent lesions on imaging.Citation48 However, it should be noted that only one patient in this study had a kidney biopsy, and one patient had elevated angiotensin converting enzyme and lysozyme on workup. This phenotype of small chorioretinal lesions, its relation to kidney disease, the use of ICGA to follow patients, and the association with HLA-DRB1 × 01 deserves further study.

Prognosis and treatment

The ocular disease is predominantly chronic and characterized by recurrences and relapses.Citation6 Saarela et al. noted 88% (14/16) of their patients had a chronic course of uveitis. Mackensen et al. noted that 28 out of 33 patients still had active disease on last follow-up with inflammation lasting greater than one year in six patients, and lasting greater than two years in four patients.Citation2 Goda et al. reported that 50% of their 12 patients had recurrence or exacerbation of uveitis during follow-up.Citation19 When corticosteroids were discontinued, Sanchez-Burson et al. noted that 50% of patients recurred.Citation36 All of these studies, and most older series, treated TINU patients solely with courses of topical and oral corticosteroids, which may not be an ideal treatment for patients with chronic disease.

There are no randomized studies on treatment strategies in TINU; however, general principles in treating chronic inflammatory disease should apply. Several studies have utilized immunomodulatory treatment with good outcomes. Gion et al. in 2000 treated six patients (four pediatric) with antimetabolites in combination with cyclosporine and achieved quiescence.Citation49 Recently, Pichi et al. treated 12 patients who recurred after discontinuation of corticosteroids with either methotrexate (5 patients), mycophenolate mofetil (2 patients) or adalimumab after failing an antimetabolite (5 patients) and achieved quiescence in all patients with excellent visual acuity (mean 0.04 logMAR) and resolution of retinal vasculitis on FA.Citation23 In Koreishi et al.’s series, 6/17 (35%) of patients received immunomodulatory therapy for ocular disease, and one was placed on immunomodulatory therapy for renal disease. The initial agent used was methotrexate in 5/7 patients and mycophenolate mofetil in 2/7 patients. Three of these patients required escalation to biologic therapy with adalimumab. Adalimumab failed to control inflammation in 2/3 patients. One patient was switched to infliximab and one further failed infliximab and golimumab with eventual disease control on intravenous tocilizumab therapy. Giralt et al. treated all of their 48 TINU patients initially with topical or oral corticosteroids, but 27 patients ultimately required immunomodulatory therapy including methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or adalimumab.Citation22 All patients on last follow-up had excellent visual acuity (mean 0.00 logMAR); however, there were still a fair number of structural complications noted, including 13 patients with posterior synechiae, 10 with cataract, 5 with ocular hypertension, and 5 with macular edema. Early initiation of immunomodulatory therapy prior to failure of corticosteroids should be considered to avoid structural complications.

Renal disease is thought to be self-limiting, especially in pediatric patients; Takemura et al. noted kidney recovery within 1 month without systemic therapy.Citation50 Indeed, it is currently debated whether acute TIN in isolation needs to be treated given spontaneous recovery, although the mainstay of treatment is corticosteroids. One study initially randomized TIN patients (with or without uveitis), and subsequently recruited additional nonrandomized patients, in order to study prednisone treatment versus placebo/no treatment. The treated group had a faster kidney recovery, although there was no significant difference between creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, or low molecular weight (LMW) proteinuria between the two study groups at 6-month follow-up. Additionally, a significant proportion in both groups still had persistent LMW proteinuria at last follow-up suggesting continued renal dysfunction regardless of prednisone treatment.Citation6,Citation51

Longer-term studies have also noted persistent kidney dysfunction in children. A study of three pediatric TINU patients who were treated with oral prednisone and received sequential kidney biopsies noted a transition from a lymphocytic infiltration to areas of atrophy, fibrosis, and scar formation.Citation40 The authors concluded that even if the kidney dysfunction is initially transient, there is a need for continued kidney monitoring, and patients may benefit from immunomodulatory therapy early to prevent long-term damage. Mycophenolate is often preferred by nephrologists over methotrexate in patients with kidney dysfunction due to the risk of methotrexate accumulation and toxicity.

Adult patients may have more severe kidney dysfunction, with one survey of adult patients with TINU revealing that 32% of patients still had moderate to severe kidney dysfunction one year after diagnosis.Citation52 Initial creatinine, serum bicarbonate and phosphate levels and age were significantly associated with kidney dysfunction at one year. Indeed, the largest review of kidney disease in TINU, which included 122 nephrology articles, demonstrated that kidney outcomes were statistically worse in adult patients compared with pediatric.Citation53 This is likely due to adults having a lower kidney “reserve.” The greatest predictor of long-term renal dysfunction was the initial severity of renal insult.Citation53

Differences between pediatric and adult cases—implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

It should be noted that most of the literature on TINU contains both pediatric and adult patients, and therefore specific conclusions unique to the pediatric population are difficult to make. Further pediatric specific studies would be useful in this regard. However, several differences can be identified. TINU is more prevalent in children, with up to 32% of all pediatric cases with bilateral sudden-onset anterior uveitis diagnosed with TINU.Citation2 However, as discussed, the disease spectrum is expanding with more reports of posterior findings, granulomatous findings, and an insidious/asymptomatic onset.Citation7,Citation14,Citation47 Therefore, we advocate for routine screening for kidney disease with urine beta-2 microglobulin and creatinine in any new uveitis patient, as these have good sensitivity and PPV in detecting TIN.Citation8

Furthermore, even in cases with normal kidney function on presentation, one must consider the possibility of transient kidney disease that may have resolved prior to presentation, especially in asymptomatic pediatric patients who present with chronic complications of uveitis. The utility of HLA-DRB1 × 01 testing in these instances is still being investigated and may prove to be useful—although the significant geographic variation in HLA alleles needs to be considered. Furthermore, HLA-DRB1 × 0102 was seen in higher frequency in pediatric patients over adults and may turn out to be more useful in the pediatric population.Citation31

Patients with kidney dysfunction detected by the ophthalmologist should be referred to a nephrologist for long-term monitoring. Even though kidney function may return to normal more frequently in the pediatric population, and is typically not the driver of treatment management, there may be long-term kidney damage that could manifest even years after the initial insult.Citation40,Citation51

The eye disease is predominantly chronic and should be treated as such. Even in Mandeville et al.’s original series, patients under 20 years more frequently had a chronic course of uveitis than older patients (23% versus 4%, respectively) and recent series show a much higher rate of chronic disease.Citation4,Citation22,Citation23 Immunomodulatory therapy for chronic disease, especially in pediatric patients, should be considered early to prevent long-term sequelae.Citation22,Citation23 Visual outcomes can be good with treatment, and several series have shown benefit from antimetabolites and TNF alpha inhibitors.Citation22,Citation23 Ultimately, a high degree of suspicion for TINU and a low threshold for kidney function testing should be employed given the implications for prognosis and treatment in both ocular and kidney disease.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dobrin RS, Vernier RL, Fish AJ. Acute eosinophilic interstitial nephritis and renal failure with bone marrow-lymph node granulomas and anterior uveitis. Am J Med. 1975;59(3):325–333. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(75)90390-3.

- Mackensen F, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Enhanced recognition, treatment, and prognosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(5):995–999.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.002.

- Kanno H, Ishida K, Yamada W, et al. Clinical and genetic features of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome with long-term follow-up. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:1–8. doi:10.1155/2018/4586532.

- Mandeville JTH, Levinson RD, Holland GN. The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46(3):195–208. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00261-2.

- Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification criteria for tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;228:255–261. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.041.

- Saarela V, Nuutinen M, Ala-Houhala M, Arikoski P, Rönnholm K, Jahnukainen T. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in children: a prospective multicenter study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1476–1481. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.039.

- Koreishi AF, Zhou M, Goldstein DA. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: characterization of clinical features. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(7–8):1312–1317. doi:10.1080/09273948.2020.1736311.

- Hettinga YM, Scheerlinck LME, Lilien MR, Rothova A, De Boer JH. The value of measuring urinary β2-microglobulin and serum creatinine for detecting tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in young patients with uveitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(2):140. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.4301.

- Amaro D, Carreño E, Steeples LR, Oliveira-Ramos F, Marques-Neves C, Leal I. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(6):742–747. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314926.

- Clive DM, Vanguri VK. The syndrome of Tubulointerstitial Nephritis with Uveitis (TINU). Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(1):118–128. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.013.

- Bergner R, Löffler C. Renal sarcoidosis: approach to diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(5):513–520. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000504.

- Yao L, Foster CS. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2001;41(4):217–221. doi:10.1097/00004397-200110000-00019.

- Okafor LO, Hewins P, Murray PI, Denniston AK. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome: a systematic review of its epidemiology, demographics and risk factors. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):128. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0677-2.

- Jahnukainen T, Ala-Houhala M, Karikoski R, Kataja J, Saarela V, Nuutinen M. Clinical outcome and occurrence of uveitis in children with idiopathic tubulointerstitial nephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26(2):291–299. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1698-4.

- Ohguro N, Sonoda KH, Takeuchi M, Matsumura M, Mochizuki M. The 2009 prospective multi-center epidemiologic survey of uveitis in Japan. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56(5):432–435. doi:10.1007/s10384-012-0158-z.

- Jones NP. The Manchester Uveitis Clinic: the first 3000 patients—epidemiology and casemix. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015;23(2):118–126. doi:10.3109/09273948.2013.855799.

- Sakhinia F, Brice V, Ollerenshaw R, Gajendran S, Ashworth J, Shenoy M. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: report of four cases. J Nephrol. 2023;36(5):1451–1455. doi:10.1007/s40620-022-01564-x.

- Eser-Ozturk H, Izci Duran T, Aydog O, Sullu Y. Sarcoid-like uveitis with or without tubulointerstitial nephritis during COVID-19. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31(3):483–490. doi:10.1080/09273948.2022.2032195.

- Goda C, Kotake S, Ichiishi A, Namba K, Kitaichi N, Ohno S. Clinical features in Tubulointerstitial Nephritis and Uveitis (TINU) syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):637–641. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.019.

- Yang M, Chi Y, Guo C, Huang J, Yang L, Yang L. Clinical profile, ultra-wide-field fluorescence angiography findings, and long-term prognosis of uveitis in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome at one tertiary medical institute in China. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(3):371–379. doi:10.1080/09273948.2017.1394469.

- Cao JL, Srivastava SK, Venkat A, Lowder CY, Sharma S. Ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography and OCT findings in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020;4(2):189–197. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2019.08.012.

- Giralt L, Pérez-Fernández S, Adan A, Figueira L, Fonollosa A. The IBERTINU study group*. Clinical features and outcomes of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in Spain and Portugal: the IBERTINU project. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31(2):286–291. doi:10.1080/09273948.2022.2026413.

- Pichi F, Aljeneibi S, Neri P. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in the United Arab Emirates. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. Published online February 15, 2023;1–5. doi:10.1080/09273948.2023.2178939.

- Paroli MP, Cappiello D, Staccini D, Caccavale R, Paroli M. Tubulointerstitial Nephritis and Uveitis syndrome (TINU): a case series in a tertiary care uveitis setting. J Clin Med. 2022;11(17):4995. doi:10.3390/jcm11174995.

- Regusci A, Lava SAG, Milani GP, Bianchetti MG, Simonetti GD, Vanoni F. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37(5):876–886. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfab030.

- Tan Y, Yu F, Qu Z, et al. Modified C-Reactive protein might be a target autoantigen of TINU syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):93–100. doi:10.2215/CJN.09051209.

- Rodriguez A. Referral patterns of uveitis in a tertiary eye care center. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(5):593. doi:10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130585016.

- Rothova A, Buitenhuis HJ, Meenken C, et al. Uveitis and systemic disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(3):137–141. doi:10.1136/bjo.76.3.137.

- Mercanti A, Parolini B, Bonora A, Lequaglie Q, Tomazzoli L. Epidemiology of endogenous uveitis in north-eastern Italy. Analysis of 655 new cases. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79(1):64–68. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0420.2001.079001064.x.

- Levinson RD, Park MS, Rikkers SM, et al. Strong associations between specific HLA-DQ and HLA-DR alleles and the tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(2):653. doi:10.1167/iovs.02-0376.

- Mackensen F, David F, Schwenger V, et al. HLA-DRB1*0102 is associated with TINU syndrome and bilateral, sudden-onset anterior uveitis but not with interstitial nephritis alone. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(7):971–975. doi:10.1136/bjo.2010.187955.

- Reddy AK, Hwang YS, Mandelcorn ED, Davis JL. HLA-DR, DQ class II DNA typing in pediatric panuveitis and tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(3):678–686.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2013.12.006.

- Peräsaari J, Saarela V, Nikkilä J, et al. HLA associations with tubulointerstitial nephritis with or without uveitis in Finnish pediatric population: a nation-wide study: HLA association in TIN. Tissue Antigens. 2013;81(6):435–441. doi:10.1111/tan.12116.

- Gorrono-Echebarria MB. The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome is associated with HLA-DR14 in Spanish patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(8):1007c–11007. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.8.1007c.

- Kanaya A. A report of an adult case of Tubulointerstitial Nephritis and Uveitis (TINU) syndrome, with a review of 102 Japanese cases. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:119–123. doi:10.12659/AJCR.892788.

- Sanchez-Burson J, Garcia-Porrua C, Montero-Granados R, Gonzalez-Escribano F, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in Southern Spain. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32(2):125–129. doi:10.1053/sarh.2002.33718.

- Vohra S, Eddy A, Levin AV, Taylor G, Laxer RM. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis in children and adolescents: four new cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13(5):426–432. doi:10.1007/s004670050634.

- Rytkönen SH, Kulmala P, Autio-Harmainen H, et al. FOXP3+ T cells are present in kidney biopsy samples in children with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(2):287–293. doi:10.1007/s00467-017-3796-z.

- Rytkönen S, Ritari J, Peräsaari J, Saarela V, Nuutinen M, Jahnukainen T. IL-10 polymorphisms +434T/C, +504G/T, and -2849C/T may predispose to tubulointersititial nephritis and uveitis in pediatric population. Ciccacci C, ed. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211915. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211915.

- Yanagihara T, Kitamura H, Aki K, Kuroda N, Fukunaga Y. Serial renal biopsies in three girls with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(6):1159–1164. doi:10.1007/s00467-009-1142-9.

- Shimazaki K, Jirawuthiworavong GV, Nguyen EV, Awazu M, Levinson RD, Gordon LK. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome: a case with an autoimmune reactivity against retinal and renal antigens. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008;16(1–2):51–53. doi:10.1080/09273940801899772.

- Abed L, Merouani A, Haddad E, Benoit G, Oligny LL, Sartelet H. Presence of autoantibodies against tubular and uveal cells in a patient with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;23(4):1452–1455. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm890.

- Li C, Su T, Chu R, Li X, Yang L. Tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis in Chinese adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):21–28. doi:10.2215/CJN.02540313.

- Takemoto Y, Namba K, Mizuuchi K, Ohno S, Ishida S. Two cases of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013;23(2):255–257. doi:10.5301/ejo.5000240.

- Sobolewska B, Bayyoud T, Deuter C, Doycheva D, Zierhut M. Long-term follow-up of patients with Tubulointerstitial Nephritis and Uveitis (TINU) syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;1–7. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1247872.

- Diala FGI, McCarthy K, Chen JL, Tsui E. Multimodal imaging in pediatric uveitis. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2021;13:251584142110592. doi:10.1177/25158414211059244.

- Ali A, Rosenbaum JT. TINU (Tubulointerstitial Nephritis Uveitis) can be associated with chorioretinal scars. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22(3):213–217. doi:10.3109/09273948.2013.841624.

- Scifo L, Willermain F, Postelmans L, et al. Subclinical choroidal inflammation revealed by indocyanine green angiography in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022;30(5):1190–1198. doi:10.1080/09273948.2020.1869267.

- Gion N, Stavrou P, Foster CS. Immunomodulatory therapy for chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis–associated uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(6):764–768. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00482-7.

- Takemura T, Okada M, Hino S, et al. Course and outcome of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34(6):1016–1021. doi:10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70006-5.

- Jahnukainen T, Saarela V, Arikoski P, et al. Prednisone in the treatment of tubulointerstitial nephritis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(8):1253–1260. doi:10.1007/s00467-013-2476-x.

- Legendre M, Devilliers H, Perard L, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome in adults: a national retrospective strobe-compliant study. Medicine. 2016;95(26):e3964. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003964.

- Southgate G, Clarke P, Harmer MJ. Renal outcomes in tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2022;36(2):507–519. doi:10.1007/s40620-022-01478-8.