ABSTRACT

This paper explores how the educational and career paths of Indigenous people in STEMM have been impacted by ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues. Based on a survey of over 400 Indigenous students and professionals in STEMM fields, plus over 30 follow up interviews, we find that these issues cause some Indigenous people to leave particular fields altogether, others to avoid certain tasks within their chosen field, and still others to intentionally select particular fields. Ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues also are the reason some Indigenous people choose certain career paths, because of their desire to help their communities. By understanding these pathway impacts, STEMM leaders and educators can ensure more equitable pathways and can prepare, recruit, and retain Indigenous people in STEMM fields.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The persistent under-representation of Indigenous people in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medical (STEMM) fields suggests that more research is needed to fully understand why these patterns continue and what can be done to alleviate the inequities that cause them. Our research suggests that certain standard practices in STEMM pathways pose ethical and/or spiritual conflicts for some Indigenous people and, therefore, contribute to the disparities in STEMM participation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

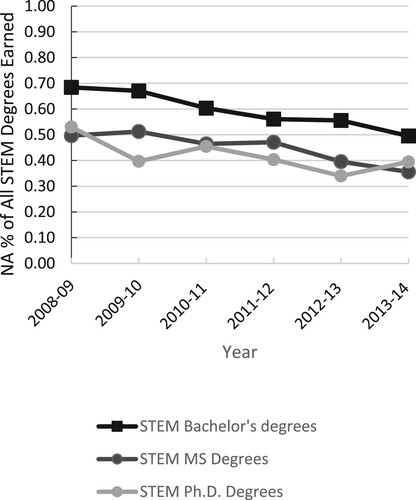

Among 18–24 year old Indigenous people in the U.S., approximately 19% are enrolled in college, compared to 41% of the general U.S. population. Among all postsecondary students, 1% of the undergraduate population and less than 1% of the graduate population identifies as American Indian/Alaska Native (Postsecondary National Policy Institute, Citation2020). highlights the percentage of degrees attained by Native American students in STEM fields at the Bachelor's, Master's, and doctoral levels from 2008 to 2014. There is a general downward trend over these years, and the percentages for STEM degrees are lower than the overall population of Indigenous students enrolled in higher education, thus indicating an under-representation that is more acute in STEM majors. Indeed, in the most recent year reported in , compared to 1% of postsecondary students identifying as AI/AN, only .5% of bachelor's, .36% of master's, and .39% of doctoral degrees in STEM disciplines were awarded to AI/AN students.

Figure 1. The percent of AI/AN students in the United States earning STEM degrees between 2008 and 2014 (National Center for Education Statistics, Citation2016).

Even with the more recent focus among STEMM funders and researchers on systemic change initiatives to address these equity gaps (e.g. NSF's Racial Equity in STEM initiative; A.P. Sloan Foundation's grant-making priorities related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, etc.), there is still a relative silence around the fundamental conflicts inherent in standard STEMM practices for many Indigenous people. Our research aims to both shed light on these conflicts and illuminate how these conflicts inform the educational and career pathways for many Indigenous students and professionals.

There is a growing body of knowledge about what constitutes ethical STEMM research and practice (e.g. Hess & Fore, Citation2018; NIH, Citation2015; Shamoo & Resnik, Citation2009), but most of this knowledge does not adequately consider the way ethics intersects with culture, and specifically, with Indigenous cultural knowledges and worldviews. Given the authors’ extensive lived experiences, work with Indigenous communities, and experience with STEMM teachers, students, and professionals, we anticipated culturally-embedded ethical issues were a significant, relatively unexplored impediment to the success of some Indigenous people in STEMM fields. For example, in some reservation-based schools, the school board members seek to limit STEMM subjects because they are perceived by Elders as contradictory to traditional cultural teachings (K. White, personal communication, 20 February 2018). Similarly, concerns have been shared with public health researchers regarding community members’ beliefs that traditional and western medicine are fundamentally at odds (N. Lee, personal communication, 2 February 2018). To investigate the extent to which this was a more general phenomenon, we explored ethically and/or spiritually-based conflicts Indigenous students and professionals experience in STEMM fields and the extent to which these conflicts impact the pursuit of STEMM related careers among Indigenous people. The nature and frequency of these conflicts are reported elsewhere (Castagno et al., Citation2022; Ingram et al., Citation2021), and we extend those findings here to explore how these conflicts impact STEMM pathways among respondents in our study. This paper specifically addresses the questions: Have educational and career pathways of Indigenous people been impacted by ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues in STEMM fields? If so, how have they been impacted?

The body of work investigating challenges for Indigenous students and professionals in STEMM disciplines has mainly focused on the lack of available role models in these fields (Ingram, Citation2009), differences in the way Indigenous people interact with each other and their surroundings (Bang & Medin, Citation2010), and the absence of culturally responsive educational practices in schools serving Native youth (Castagno & Brayboy, Citation2008). But there is virtually no empirical research that investigates the role or frequency of culturally significant ethical and spiritual taboos that may be experienced in STEMM pathways among Indigenous people. There is also limited work on how these issues may present very real conflicts with STEMM training and career expectations for Indigenous people (Williams & Shipley, Citation2018). Indeed, Caughman (Citation2013) points out that we have not adequately investigated the diverse backgrounds of cultural groups in STEMM or, more importantly, Indigenous people's spiritual and/or religious relationships to the universe and how fundamental these relationships are to engaging in STEMM career paths. Many of us know from experience that some Indigenous people may consider certain standard practices in STEMM (i.e. viewing of an eclipse, working with human remains, designing infrastructure on sacred sites) as taboo or otherwise problematic, but we lack empirical research that confirms the anecdotes many of us have accumulated over the years. Further, the perceived non-acceptance of religion and spirituality within the scientific community accentuates cultural differences between some Indigenous people and STEMM fields (Weldon, Citation2007).

Terminology

Before proceeding, it is important to explain our use of particular terms throughout this paper. The first is the acronym STEMM. Our initial project was conceptualised as including STEM fields (not including the final M for medicine/health-related fields). However, our research included survey respondents and interviewees in medicine/health-related fields, so our subsequent analysis and discussion uses the more inclusive acronym of STEMM. When citing other work that uses the STEM acronym, we follow the usage of the relevant author(s). Second, we use ‘Indigenous,’ ‘Native American,’ and ‘American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN)’ interchangeably throughout our research to refer to the original peoples in what is now the United States. We recognise that these terms have distinct meanings and carry important differences depending on context. We prefer the term Indigenous as it recognises land-based identities and is inclusive of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Peoples. We use this term in most cases, but we follow the lead of other authors when referring to their work and/or datasets. And finally, readers will note that the title of the paper and the survey items detailed later include the terms ‘cultural,’ ‘ethical,’ and ‘spiritual’ to describe the possible conflicts experienced by Indigenous people in STEMM fields. Our initial study design and survey included all three terms because they each seemed to capture a potential type of conflict that our research team was attempting to understand. We also anticipated that some research participants may have found resonance with one term, while other participants may have been drawn to a different term. As this was an exploratory study, we wanted to be as inclusive and open as possible in our data collection efforts. We realise some readers may find these terms repetitive, but we have carried these three terms forward in our dissemination of the study results in order to, again, not limit the way the conflicts experienced by some Indigenous people in STEMM are characterised.

Methodological framework and research design

Our research employed a mixed methods approach informed by both Grounded Theory and Critical Indigenous Research methodologies to investigate the ethical considerations faced by Indigenous STEMM students and professionals in the western United States. Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) is an inductive, iterative, and comparative methodology aimed at theory-development (Charmaz, Citation2006). Researchers in this tradition move back-and-forth between data collection, data analysis, and writing to ultimately arrive at a clear understanding and/or explanation of a particular phenomenon (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Although there are various iterations of Grounded Theory, they all share a focus on ‘studies of individual and collective actions and social and social psychological processes’ (Thornberg & Charmaz, Citation2012, p. 42). Drawing on Grounded Theory, we worked through the quantitative and qualitative data to develop an explanation for the role of cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical conflicts in the STEMM pathways of Indigenous people in the western U.S. Critical Indigenous Research Methodologies (CIRM) have developed out of a long tradition of Indigenous scholars and communities who have argued that research with Indigenous peoples must adhere to a set of guiding principles (Smith, Citation1999). These principles include fore-fronting the inherent sovereignty and self-determination of tribal nations, honoring and building on relationships within and between researchers and community members, and pursuing research questions that will advance community needs and interests (Brayboy et al., Citation2012). Our research necessitates a combining of both Grounded Theory and Critical Indigenous Research Methodologies because methodology, by definition, informs how and why research is pursued, drives the assumptions of the research and the selection of methods, and situates research in a particular place and time.

This project developed explicitly out of the authors’ relationships, experiences, and expertise around Indigenous education, STEMM pathway concerns, and Native Nations’ desires for highly educated STEMM professionals who can serve their communities. Ingram and Castagno came together around a shared interest in understanding the role ethical conflicts may play in Indigenous people's STEMM career pathways. Ingram is an Indigenous woman and analytical chemist whose expertise centers on environmental health issues on tribal lands caused by legacy hard rock mining and pesticide use. In her labs and student training programs, Ingram has experienced, first hand, concerns involving ethical issues in science and her Indigenous students’ perspectives. Castagno is a White woman whose expertise is in Indigenous education, racism and educational equity, and qualitative research methodologies. After securing funding from the National Science Foundation for this project, Camplain joined the team as a Research Specialist because of her expertise in quantitative research methods and statistics. As an Indigenous woman in STEMM, Camplain also brought important lived experience and insight to the research team. The authors’ combined lived experiences and disciplinary expertise informed the development of the survey and the interview questions used in this research. Castagno and Ingram initially drafted the survey and interview questions, which were then disseminated to a dozen Indigenous colleagues in diverse STEMM fields. These colleagues were asked to complete the survey and provide feedback on content, clarity, and structure of both the survey and interview questions. We asked these colleagues to especially reflect on their own lived experiences, and to consider how the questions could explicitly elicit narratives that typically get erased within STEMM communities. Castagno and Ingram then revised the survey and interview questions accordingly and these final iterations of the protocols were used for data collection via Qualtrics. We intentionally combined surveys with interviews in our mixed methods design to account for both breadth and depth in the data collection, and both the survey and the interviews allowed for diverse modes of storytelling among participants.

Study design and study sample

The cross-sectional online survey was sent to two distinct participant groups in the western United States: Indigenous post-secondary (undergraduate and graduate) students in STEMM degree programs and Indigenous professionals in STEMM fields. The western United States region was defined as all states inclusive and west of New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana.

Using purposive sampling (Etikan et al., Citation2016), Indigenous students and professionals were recruited through student and professional listservs (i.e. American Indian Science and Engineering Society, Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science, Native Research Network), professional connections, and snowball sampling. Participants were included if they (1) identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, (2) were an undergraduate student, graduate student, or professional in a STEMM field at the time of the study, (3) 18 years of age or older, and (4) resided in the western U.S. at the time of the study. The Northern Arizona University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study, and all participants provided informed consent. A total of 409 participants met inclusion criteria and completed the survey (206 Indigenous professionals and 203 Indigenous students).

Demographics

Participants were asked about demographic information, including which STEMM field they identified with (life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, mathematics, computer sciences, health sciences, or other); age group (18–22 years, 23–29 years, 30–40 years, 41–50 years, or >50 years); gender (male, female, other); where they grew up (urban, suburban, rural, reservation, or other); and where they currently live (urban, suburban, rural, reservation, or other).

Data collection and analysis

Participants were asked to reflect on cultural, spiritual, and ethical considerations in their career decisions and the ways culture, spirituality, and ethics impact Indigenous people in STEMM. Specifically, participants were asked:

Have your career decisions been at all influenced by cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical considerations? (yes, no, other)

Do you think some Indigenous people in STEMM professional roles have unique cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual concerns or issues to consider? (yes, no, other)

Do you think being an American Indian/Alaska Native creates advantages or disadvantages in STEMM careers? (advantages, disadvantages, both, neither, not sure)

Participants were additionally asked to report on their level of agreement on statements regarding cultural, ethical, and spiritual impacts on Indigenous people in STEMM using Likert scale responses (Strongly Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neither Agree or Disagree, Somewhat Agree, Strongly Agree). Frequencies and relative frequencies were used to summarise STEMM-related activity information. All analyses of these sections of the surveys were conducted using SAS V9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Participants responded to six open-ended questions asking them to elaborate on earlier survey responses.

‘Please give an example of an ethical, spiritual, and/or cultural issue you have experienced in your STEM work/professional roles. Provide as much detail as possible about what the issue was, how/why it was significant for you, and how you handled the issue. If you have never experienced an ethical or cultural issue in your STEM professional roles, please state that and comment on why that might be.’

‘Please describe any additional cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual issues you think some Native people in STEM professions face. If you don't believe there are cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual issues that are unique to Native people in STEM professions, please state that and comment on why you believe that.’

‘Please explain your answer to the previous question (i.e. have your educational or career decisions been influenced by cultural/spiritual/ethical considerations) by providing an example or other explanation.’

‘Please explain your answer to the previous question (i.e. do some Indigenous people in STEM fields have unique cultural/ethical/spiritual issues to consider) by providing an example or other explanation.’

‘Please explain your answer to the previous question (i.e. does being AI/AN create advantages or disadvantages in STEM fields) by providing an example or other explanation.’

‘Please explain your answer to the previous question (i.e. have your career decisions been influenced by cultural/spiritual/ethical considerations) by providing an example or other explanation.’

‘Please explain your answer to the previous question (i.e. do some Indigenous people in STEM have unique cultural/ethical/spiritual issues to consider) by providing an example or other explanation.’

‘Please explain your answer to the previous question (i.e. does being AI/AN create advantages or disadvantages in STEM careers) by providing an example or other explanation.’

We followed up the survey with 17 interviews with Indigenous students and 13 interviews with Indigenous professionals. The interviews were accomplished either in person or virtually. Some of the interviews were one-on-one interactions while others involved two participants. One student interview session included a virtual discussion with a class of seven students. The interviews were recorded and transcribed using Landmark Associates, Inc. (Phoenix, AZ). Notes were also collected by the interviewers during the session.

The open-ended survey questions and transcribed interviews were inductively analysed using open coding methods (Glesne, Citation2010), followed by focused coding using the constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). An important limitation relevant to the findings reported in this paper is that our data does not include Indigenous people who may have started in STEMM fields and later opted out of these pathways since a criterion for inclusion in the study was current involvement in STEMM degree programs and/or careers.

Results

This paper specifically reports on the data that speak to the way educational and/or career paths of Indigenous people in STEMM have been impacted by ethical/cultural/spiritual conflicts. But it is important to first establish that Indigenous people in STEMM do indeed experience unique cultural, ethical, and spiritual dilemmas given the norms and expectations of their fields and their spiritual and cultural commitments. We report on these data in a forthcoming paper, so we offer only a brief overview here to frame the discussion in this paper about the ways these conflicts impact educational and career pathways.

Of the 203 Indigenous students who completed the survey, 27% were in health sciences, 22% in life sciences, 16% in engineering, 15% in mathematics, 11% in physical sciences, and 6% in computer sciences (). Almost half of students were 18–22 years, 50% had not completed a degree yet, and 57% were female. Students grew up in urban (19%), suburban (22%), rural (34%), and reservation (24%) areas. Half of the student participants lived in urban areas while only 11% lived on reservation land at the time of survey completion.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics among Indigenous STEMM students and professionals, 2019.

Of the 206 Indigenous professionals who completed the survey, 23% were in life sciences, 22% in engineering, 18% in health sciences, 12% in physical sciences, 10% in mathematics, and 10% in computer sciences (). Three-quarters of the professional participants were 30 years or older, over half were male, 54% had a bachelor's degree, and about 30% had a master's or professional degree. Professionals grew up in urban (23%), suburban (17%), rural (33%), and reservation (28%) areas. Over half of the professional participants lived in urban areas while only 9% lived on reservation land at the time of survey completion.

The impact of ethical conflicts on indigenous students’ STEMM pathways

We focus first on what we learned about the ways cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts may be impacting Indigenous students’ STEMM pathways. Most student participants indicated that their career decisions were influenced by cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical considerations (58%, ) with a higher proportion of engineering (61%) and health science students (70%) indicating cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical considerations (Supplemental Table 1). A higher proportion (77%) of student participants said they believed Indigenous people in STEMM roles, in general, have unique cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual concerns or issues to consider in the discipline. About half of the student participants (51%) also indicated that being American Indian/Alaska Native creates both advantages and disadvantages in the STEMM fields. Student participants additionally, on average, agreed (Likert mean above 3) to all Likert questions regardless of STEM discipline, including stating that their cultural identity and tribal affiliation impacted their choice of majors in college and career decisions (). Students also agreed that American Indian/Alaska Native people in STEM fields have unique cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical issues to consider and they knew at least one Indigenous person (besides themselves) whose cultural identity had some impact on their choice of STEM majors/careers. Agreement to cultural, spiritual, and ethical impacts was similar across STEMM discipline (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2. Perspectives of Cultural, Spiritual, and Ethical Considerations in STEMM among Indigenous STEMM students and professionals, 2019.

Table 3. Level of agreement on a Likert Scale of cultural, spiritual, and ethical impact in STEMM fields among Indigenous STEMM students and professionals, 2019.

The qualitative responses from Indigenous students in our research indicate that approximately two-thirds of the students who responded qualitatively report that their educational path was not yet impacted by cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts in STEMM. Those who report that their paths have not been impacted by these issues attribute this to one of two reasons: either because they are ‘early’ in their educational journeys (i.e. in their first few years of college) or because they do not identify as being ‘traditional.’ As one student said, ‘I have not been influenced by ethical considerations because I am not traditional.’ And another echoed this same rationale: ‘No because although I identify as Native American, I have never really led a traditional lifestyle.’ Among those who referenced being early in their educational pathways, most also noted that they anticipated that conflicts could arise later in their STEMM journey. Almost all students acknowledged that they have heard about conflicts from their friends, family, or other acquaintances, and that most of these conflicts arise related to animal testing, working with cadavers, and/or land extraction activities.

About a third of the students who provided qualitative responses either on the survey or through interviews, however, did indicate that their educational pathways have been impacted by cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual issues in STEMM. Among these students, the responses typically fell into one of two categories, as we describe below. Among students in both categories, the qualitative responses often included reference to family members and/or Elders whom the students either talked explicitly to about these issues or thought about and recalled memories of interactions with that informed the students’ decision making related to these issues.

Serving one's community as a driver of STEMM field selection

The first category of those whose educational path was impacted by cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts was students who described intentionally choosing a particular field or area of study because they wanted to serve their community, and they perceived this field or area of study to be relevant to the needs of their community. Admittedly, when we initially designed this research, we did not have these students in mind, but their experiences and rationales are telling. Some students’ responses were fairly general, such as the young man who explained, ‘My educational decisions have been influenced by my cultural background. By going into a STEM major, I plan on coming back to my reservation and helping with problems that they are being affected by,’ and the young woman who told us, ‘My grandparents always told me I needed to go to school to learn. I went to school for them. They knew the conditions of reservations and how they need help. They wanted their grandchildren to learn to help their people.’ Other students were more specific about their chosen pathways, and most of these responses were either in the medical/health fields or in the environmental and natural sciences fields. Consider this student's narrative:

My major educational influence came from my great-grandfather's life teachings based in Navajo traditional philosophy and history. He lived into old age, was/is highly regarded by the Navajo community, represented resilience, and was my first role model for health. His personal attributes and characteristics instilled in me the importance of physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental health molded by Navajo traditions. This reflection motivated me to pursue exercise science and public health as ways to combat the imbalance Navajo people are currently facing that have resulted in negative health effects such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and community disintegration.

I have always wanted to pursue a career in the medical field. I believe in order to be successful in this field I will have to make some sacrifices, but I am lucky enough to have a family and community who encourages the pursuit of a degree.

According to Anishinaabe tradition, women are the traditional protectors of water. Knowing this, I knew it was important for me to carry on this tradition, especially coming from a community that is surrounded by water and continuously threatened by climate change and large corporations.

We see a similar centring of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (Brayboy & Maughn, Citation2009; Finn et al., Citation2017; Whyte, Citation2013) in this woman's reference to the role of being a water protector and the relationships between gender, the earth, and community. Another student draws on his epistemological, axiological, and ontological understandings when he explained ‘I chose to do biochemistry because I wanted to know everything about the earth, as my culture teaches everything has a reason.’

Avoiding STEMM fields due to ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual conflicts

The second category was students who described intentionally avoiding a particular field or area of study because of actual or anticipated cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts. Medical and biological sciences, in particular, were especially conflict-laden for most students in this category – which is an interesting juxtaposition to the students we discuss above who intentionally selected medical and health-related pathways because they perceived these fields as leading to important careers that allowed them to serve and/or give back to their communities. We share quotes from four different students that are representative of the ideas expressed by many others who intentionally avoided medical and biological pathways because of the association of these fields with animal and human lab work:

‘I don't believe in animal testing, so I choose not be involved in that area of medicine development and research.’

‘I have had to kill macroinvertebrates in order to study them. I do not think this is ethical, and it hurts to do work like that. This ultimately made me stop doing the water quality work I was engaged in.’

‘I have chosen to be a part of a STEM field that did not deal directly with humans, human remains, as it could alter my spiritual state short and long term. I have chosen to pursue physics as opposed to biology.’

‘As I began to think about my career choices, I juxtaposed my personal interests and cultural understanding of the STEM fields and came to choose mathematics and statistics over medicine because of my cultural considerations. I did not want to see a dead human body or dissect anything.’

Clearly, there is a strong avoidance for some Indigenous students to pursue STEMM pathways that involve working with animals and animal remains (including, of course, humans). The students sharing these narratives are those that found pathways in other STEMM fields that worked for them, but we can safely infer that there are many other students for whom similar conflicts lead to educational and career pathways outside of STEMM.

As we discuss in more detail elsewhere (Castagno et al. Citation2022), some students engage in complex navigational and negotiation processes along their educational pathways. Of particular relevance for our discussion in this paper, a handful of students who chose medical or biological fields did so knowing about the likely cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts, but they found ways to accommodate the necessary tasks. As one student explained,

I was quite hesitant to even begin this degree for veterinarian technician since I would need to be able to conduct these tasks in order to complete the degree successfully. It's a constant clash of modern day and traditional teachings.

Part of my public health major required me to take anatomy and physiology. In that class, we had the option of viewing a cadaver. My husband and I discussed if I should go to the optional class. We weighed the pros and cons of me going and we both decided that I shouldn't go because it would require me to have a protection prayer done, which I could not schedule in before the optional class.

In high school I was in an anatomy & physiology class where we conducted dissections every other week. Since in my cultural beliefs it is bad or taboo to dissect animals from the ocean, which in class they did regularly, I was unable to participate along with another Native American friend of mine. I was then sent to the library to conduct research online instead, which made me miss out on that hands-on experience. I listened to my father who was very strict about such things and did not dissect anything that whole year of my anatomy class.

Also, I am beginning to start my journey on obtaining a veterinarian technician degree, which involves me potentially dissecting many animals and performing many procedures on them. This has put me at a setback since my family is quite traditional, so I discussed this problem with my parents and we had come to an agreement that I get a certain ceremony done before I begin my vet tech classes next year so that the blood from the animals does not affect me later in life mentally, spiritually, emotionally, and physically.

The impact of ethical conflicts on indigenous professionals’ STEMM pathways

As compared to students, a higher percentage of professional participants indicated that their career decisions were influenced by cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical considerations (61%, ), with the highest proportions coming from those in mathematics (71%) and health sciences (78%, Supplemental Table 3). However, most computer sciences professionals (52%) did not consider cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical reasons when making career decisions. A higher proportion (73%) of professional participants said they believed Indigenous people in STEMM roles, in general, have unique cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual concerns or issues to consider in the STEMM disciplines. Compared to students (51%), a higher proportion of professional participants (64%) suggested that being American Indian/Alaska Native creates both advantages and disadvantages in the STEMM fields. Professional participants additionally, on average, agreed (Likert mean above 3) to all Likert questions regardless of STEM discipline, including agreeing that their cultural identity and tribal affiliation impacted their choice of majors in college and career decisions (). However, averages were close to ‘neutral’ responses, overall and by STEMM discipline (Supplemental Table 4).

There were a number of similarities between the qualitative responses of STEMM professionals and STEMM students in our study. In particular, the two categories we identified among student responses were also evident among professional responses – that is, some professionals discussed avoiding certain fields because of anticipated conflicts, and other professionals discussed intentionally selecting certain fields because of the opportunities those fields presented for serving their communities. Similar to the student narratives, these responses most often related to medical and health fields, as well as occasionally to environmental and natural sciences. As one professional respondent summarised, ‘A lot of Native people will stay away from the STEM fields because certain areas and research require you to kill animals.’ Another professional explains his avoidance of a particular career path and intentional selection of another that he perceived to be ‘safer’:

I was trained in the medical field as a combat medic and I wanted to increase my skills, but I will not work with a dead body. In the same respect, I will not experiment on living beings for testing, confinement, or any other unhealthy experiments. I have no issues with microbes for determining effective resolutions for the healing of people or animals. I would and did work with cultures to diagnosis diseases. The safer route has been working with electronics, programming, networking, web development.

I have not experienced ethical, spiritual, and/or cultural issues with my profession as an analyst and environmental technician. My job is to help monitor air quality, tribal source water quality, and drinking water quality with my tribe. I choose my interest for my profession around the fact that I respect the dead and am unable to perform dissections. I was interested originally in a biology degree, but I found I excelled in chemistry luckily so I was able to avoid any issues with biology.

Professionals’ pathways decisions benefit from time and lived experience

In addition to the similarities across the students’ and professionals’ narrative responses in our study, there was also a notable difference in that some of the professionals’ narratives pointed to how their understandings of these issues have evolved over time with more lived experience. Consider, for example this professional's lengthy description:

Death is a huge cultural, ethical, and spiritual issue among many Southwest tribes. There are ceremonies that address it in different ways and teachings of how it is linked to physical, mental, and emotional health. Many professionals pursuing a career that addresses this issue either through environmental science or health science are cautioned about the dangers. This plays heavily on many decisions we make on a daily basis. In my experience, many of my own personal struggles have been because of the career I have chosen in health sciences and have had to see a traditional practitioner to help me see what is affecting me and how to resolve it. Over time, I have learned to defend my position on whether to partake in certain practices at my job or to speak up if it makes me uncomfortable. As I become more certain in my beliefs and way of life, I no longer feel obligated to compromise them in order to do my job and I know how to deal with them should they occur. Another key issue regarding cultural issues is that of being able to come home often to help with family events like ceremonies and livestock. This was of particular concern to me as I chose how to continue my education into college. I wanted to be able to do this as well as pursue a career in research. Many opportunities exist away from the area I live and this was hard to pursue because of my obligations to my traditional practices.

I have seen many opportunities pass me by because I chose not to pursue them due to my cultural beliefs, but I have also been given many opportunities because I possess this unique knowledge. I don't consider it bad or good but I do know that the extra freedom to live where you want and do what you want is tempting and some might see cultural beliefs as holding them back. I feel like it has kept me grounded and focused. I believe it's a matter of perspective on this one.

Discussion

The focus of this paper is to address the questions: Have educational and career pathways of Indigenous people been impacted by ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues in STEMM fields? If so, how have they been impacted? The survey results indicate that 51% of the student participants reported their educational and career pathways were influenced by ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual considerations. In particular, those students in the engineering and health fields reported the highest levels of impact. Interestingly, the qualitative results collected through short responses within the survey or the interviews of a smaller set of student participants report less impact of ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual conflicts in STEMM fields, particularly among those early in their academic training. This is not surprising as many of these students expressed that they had not met any barriers in their academic training, but they did know of other Indigenous students who had conflicts related to ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues. Additionally, an overlying theme from the qualitative results was that student participants thought by not majoring in biology or health sciences, they would avoid ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues such as dissection of animals or working with cadavers.

Ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues played two roles in impacting the choices of Indigenous students. Some of the student participants reported that cultural values and the desire to help their communities was important to them in making choices on career paths. Other student participants reported that their choice in a specific academic discipline was determined based on avoiding perceived cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts that would make it hard to do well in classes. These very different effects on choices made by Indigenous students points to the complexity of how ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues impact career choices at the student level. Factors observed from the qualitative results included how traditional a student considered themselves as well as support or opposition their family provided in participating in educational activities that were considered culturally taboo.

Likewise, the results from the Indigenous professionals that participated in the study indicate 61% reported their educational and career pathways were influenced by ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual considerations, which is a larger fraction than the student participants. Of these, the professionals in mathematics and health sciences had higher proportions compared to professionals in computer sciences. Interestingly, about three-fourths of the professional participants believed Indigenous people in STEMM have unique ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual considerations compared to non-Indigenous people. Similar to the student participants, the professionals' career choices were impacted by ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues either to avoid conflicts or to help their communities by becoming a professional in a STEMM field. Our qualitative results from the professionals indicated a maturity in dealing with conflicts that arise from ethical, cultural, and/or spiritual issues. Clearly, the lived experiences of the professionals allow them to report nuanced perspectives on the issues as well as navigation strategies.

Lessons learned and future directions

The results of our study indicate that some Indigenous people experience uniquely significant ethical tensions between standard practices, norms, and expectations in STEMM fields and their own cultural, spiritual, and epistemological commitments. Although there is a growing body of research on factors that contribute to the under-representation of Indigenous people in STEMM, there exists a paucity of research focused on the potential impact of culturally-, spiritually-, and/or epistemologically-informed ethical conflicts on Indigenous students’ and professionals’ decisions to pursue and remain in STEMM careers. We also know very little about the nature and frequency of these types of conflicts that emerge in practice for Indigenous people in STEMM. In addition to our research, a recent notable exception can be found in the work of Williams and Shipley (Citation2018), who interviewed 96 students from 42 different tribes at Haskell Indian Nations University. They found that over half of the students generally observe tribal taboos, and over a third of the students would not pursue STEMM majors if they suspected that doing so would require them to violate taboos. Importantly, over two-thirds of the students responded that they would be more likely to take STEMM classes if the curriculum was more respectful of tribal taboos.

Our mixed methods research was designed because of a series of anecdotal experiences with STEMM students and professionals who struggled with conflicts between their own cultural and spiritual beliefs and tribal taboos, and various standard practices within their STEMM fields. Critical Indigenous Research Methodologies informed the identification of the research questions, the development of the survey and interview protocols, the recruitment of participants, the relational rapport-building we engaged during interviews, and the analysis of data. Grounded Theory pushed our thinking towards the development of an accurate and robust explanation for the patterns we identified in the data. Through a survey with over 400 Indigenous student and professionals, and follow up interviews with over 30 of them, we found that culturally and spiritually-informed ethical conflicts are quite common among Indigenous people in STEMM fields, and that these conflicts do indeed impact the educational and career pathways of many Indigenous individuals. An important nuance in our findings was that some Indigenous students opt in to STEMM pathways because of their cultural, spiritual, and/or ethical commitments, so we should not always assume that Indigenous identity equates only to decisions to opt out of STEMM. But for many of the participants in our research, intentional pivoting was a common strategy – either pivoting to a STEMM field that was perceived to be ‘safer’ and/or pivoting away from specific tasks that were especially conflict-laden for them. Overall, we learn that ‘one size does not fit all’ with respect to taboo activities among Indigenous people in STEMM, which should not be surprising given that there are over 470 federally recognised tribes in the western U.S. (and over 570 in the entire U.S.), each with distinct languages, cultures, histories, and knowledge systems.

We would be remiss not to point out that the students and professionals in our study also reference many of the issues that are already common in the literatures on Indigenous education and equity gaps in STEMM. Specifically, the students often noted experiencing racism, discrimination, and bias in their STEMM pathways; the importance of having faculty who have some familiarity with Indigenous communities and are willing to accommodate the students’ cultural responsibilities when they arise; and feelings of inadequacy and imposter syndrome. This student's narrative illustrates many of these themes:

I think Natives in STEM experience racism and ignorance that can negatively affect relationships. People tend to think that we are only here because our tribe or the government pays for school and we are involved in an affirmative action type of situation. We have much to prove, especially in STEM, as far as our deserving to be there. And it isn't fair that we have to. In the majority of instances, we have to earn our way like any other student.

I choose to be an Indigenous STEM professional because I wanted to be one of the few who are working in the field, representing their tribe and culture, as well as battling misconceptions and racism. I want to make it easier for someone younger to claim space in a field that needs representation.

Although our research confirms many of the known barriers to more inclusive and equitable STEMM pathways for Indigenous students and professionals, we also add knowledge and evidence about the additional structural barrier caused by many standard practices in STEMM fields. The lessons learned from our survey respondents and interviewees should give pause to those of us who teach, lead, advocate, and research in STEMM pathways. Now that we understand how the educational and career pathways of many Indigenous students and professionals are impacted by cultural, ethical, and/or spiritual conflicts, it is incumbent upon us to be responsive if we are truly committed to broadening participation in STEMM among Indigenous people.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of the National Science Foundation for support of this research (grant # 1835108), as well as Ms. Davona Blackhorse, who served as a Graduate Research Assistant and provided support during the early years of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bang, M., & Medin, D. (2010). Cultural processes in science education: Supporting the navigation of multiple epistemologies. Science Education, 94(6), 1008–1026. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20392

- Brayboy, B., Gough, H., Leonard, B., Roehl, R., & Solyom, J. (2012). Reclaiming scholarship: Critical Indigenous research methodologies. In S. Lapan, M. Quartaroli, & F. Riemer (Eds.), Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and design (pp. 423–450). Jossey Bass.

- Brayboy, B. M. J., & Maughn, E. (2009). Indigenous knowledges and the story of the bean. Harvard Educational Review, 79(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.1.l0u6435086352229

- Castagno, A. E., & Brayboy, B. K. J. (2008). Culturally responsive schooling for Indigenous youth: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 941–993. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308323036

- Castagno, A. E., Ingram, J. C., Camplain, R., & Blackhorse, D. (2022). “We constantly have to navigate”: Indigenous students’ and professionals’ strategies for navigating ethical conflicts in STEMM. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 17(3), 683–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-021-10081-5

- Caughman, L. (2013). Native American women in science: A historical and cultural perspective. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1523.8161

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Finn, S., Herne, M., & Castille, D. (2017). The value of traditional ecological knowledge for the environmental health sciences and biomedical research. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(8), 085006. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP858

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine.

- Glesne, C. (2010). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Pearson.

- Hess, J. L., & Fore, G. (2018). A systematic literature review of US engineering ethics interventions. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(2), 551–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9910-6

- Ingram, J. C. (2009). Establishing relationships and partnerships to engage Native American students in research. In M. Boyd & J. Wesemann (Eds.), Broadening participation in undergraduate research: Fostering excellence and enhancing the impact (pp. 269–280). Council on Undergraduate Research.

- Ingram, J. C., Castagno, A. E., Blackhorse, D., & Camplain, R. (2021). Role of professional societies on increasing Indigenous peoples’ participation and leadership in STEMM. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.753488

- National Center for Education Statistics, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. (2016). Degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions in selected professional fields, by race/ethnicity and field of study: 2013-14 and 2014-15. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_324.55.asp

- National Institute of Health (NIH). (2015). Notice NOT-OD-15-103: Enhancing reproducibility through rigor and transparency. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-103.html

- Postsecondary National Policy Institute. (2020). Factsheet: Native American Students in Higher Education. https://pnpi.org/native-american-students/

- Shamoo, A. E., & Resnik, D. B. (2009). Responsible conduct of research. Oxford University Press.

- Smith, L. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

- Thornberg, R., & Charmaz, K. (2012). Grounded theory. In S. Lapan, M. Quartaroli, & F. Riemer (Eds.), Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and design (pp. 41–68). Jossey Bass.

- Weldon, S. (2007). Science & religion: A historical introduction. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Whyte, K. P. (2013). On the role of traditional ecological knowledge as a collaborative concept: A philosophical study. Ecological Processes, 2(7). https://doi.org/10.1186/2192-1709-2-7

- Williams, D., & Shipley, G. (2018). Cultural taboos as a factor in the participation rate of Native Americans in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0114-7