ABSTRACT

Outdoor early childhood education contexts such as nature kindergartens have been established for well over 50 years in the United Kingdom and Scandinavia. Despite their popularity in these settings, similar approaches in countries such as Canada, China, New Zealand and Australia have taken time to become established. One example of where this approach to nature kindergartens in early childhood education has recently taken a foothold is the Australian ‘bush kinder’. Bush kinders are a context where four- to five-year-old preschool children can experience and learn biological, chemical and physical sciences in natural environments through play. This paper draws on research undertaken in bush kinders, applying ethnographic data. Data collection commenced in 2015 and subsequently, members of the research team returned to bush kinders in 2017, 2020 and 2023 to understand how the bush kinder approach to curriculum has continued to develop and grow. We respond to two research questions in this paper, (1) What are teachers’ experiences of an emergent science curriculum in bush kinder setting? And (2) How does an emergent science curriculum develop within bush kinder settings? Through observing educators’ application of emergent curriculum, we found that time spent in bush kinder provides children with the voice to articulate their science understandings.

Introduction

There has been a growing movement in early childhood education and care (ECEC) towards getting young children ‘back to nature’ (Speldewinde et al., Citation2020). Nature kindergartens, as a way of building young children’s experiential knowledge of the environment, have been prevalent in contexts such as the UK and Scandinavia for well over 50 years (Knight, Citation2016). Leveraging upon the popularity and rich teaching and learning experiences of their European counterparts, educators in other contexts including Canada, China, New Zealand and Australia have begun to establish their own forms of nature-based education for ECEC, often based on local environmental conditions. An example of nature kindergartens is the Australian ‘bush kinder’ approach, an educational context where 4- to 5-year-old preschool children attend weekly kindergarten sessions in an underdeveloped setting such as a nature reserve, a beach or a parkland within close proximity to the kindergarten premises. Bush kinders move children from the bounded environment of the usual kindergarten setting to a new ‘place’ or setting. This ‘place’ emphasises direct experience as the best way to nurture children’s relationships with nature and learning that provides ‘direct and unmediated sensory contact with non-human others’ (Greenwood & Hougham, Citation2015 , p. 97). Nature kindergartens such as bush kinders facilitate a range of learning which can include children’s social and emotional development, risk and resilience development, cognitive and affective learning. Through developing these skills, children then learn about STEM, Art, Humanities and Literacy (Dillon, Citation2016; Rickinson, Citation2001). Engaging in play within these natural environments creates a meaningful context in which children can experience and learn biological, chemical, and physical sciences (Campbell & Speldewinde, Citation2020).

The introduction in 2009 of the Australian Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF), a curriculum document that provides educators with broad direction to facilitate children’s learning, provided the impetus for the bush kinder approach to nature-based ECEC to take hold in Australia (Hughes, Citation2022). The EYLF proposed that educators should teach children ‘about the natural environment and how to take care of it’ (DEEWR, Citation2009, p. 8) which played a role in educators developing nature pedagogy, that is, a form of experiential teaching and learning practice exemplified in UK and Scandinavian contexts that involves embracing a sense of being with and in nature that often follows the child’s lead in play (Speldewinde et al., Citation2020). Revised in 2022, the EYLF (AGDE, Citation2022) outlines five learning outcomes for children from birth to five years supporting children to have a strong sense of identity, to be connected and contribute to their world, develop a strong sense of wellbeing, be confident and involved learners and effective communicators. From the perspective of science teaching and learning, however, the framework does not specify science conceptual or procedural knowledge (Guarrella et al., Citation2022; Havu-Nuutinen et al., Citation2021). Rather, the EYLF states that educators should be ‘responsive to children’s funds of knowledge (experiences and understandings), ideas, sociality and playfulness, which form an important basis for curriculum decision-making … . They make use of … spontaneous ‘teachable moments’ to scaffold children’s learning’ (AGDE, Citation2022, p. 21). This description loosely describes what can be termed as an emergent curriculum.

An emergent curriculum in ECEC often starts as a spontaneous process generated from young children’s daily lives and is subsequently supported by educator planning and intentional teaching (Mogharreban et al., Citation2010; Salmon & Barrera, Citation2021). Allowing the child to articulate their thoughts, as opposed to the educator leading the thinking, facilitates children to (co)construct their learning (Sampson & McLean, Citation2021). This is particularly important in science. Giving children a voice has been shown to be critical in supporting their science learning as it allows a child to demonstrate their science knowledge and share their ideas with educators (Campbell et al., Citation2023). We identify a young child’s voice as giving the opportunity to give rise to a child’s ‘feelings, beliefs, thoughts, wishes, preferences and attitudes’ (Murray, Citation2019, p. 1). Similarly, through the experience of an emergent curriculum, the child’s voice is drawn out allowing educators to deeply understand their shared experiences (Wien, Citation2015). Further to this, in consideration of science in ECEC, emergent curriculum develops from and as a response to children’s investigations and interests to create meaningful learning experiences (Howitt & Jobling, Citation2021). There is a strong emphasis on children’s interests in natural scientific phenomena acting as the vehicle to develop science skills and knowledge (Guarrella, Citation2021) and to propel the progression of an emergent curriculum. Therefore, educators can draw upon opportunities to identify children’s science learning in play and embed these within an emergent curriculum that is flexible and responsive to children’s discovery (Antara, Citation2021). Whilst the EYLF does not provide teachers with guidance on how to systematically embed science teaching and learning in ECEC (Guarrella et al., Citation2022) promisingly, the framework highlights that opportunities for teaching and learning occur in outdoor, natural settings such as bush kinders. Further, mechanisms such as the Early Years Planning Cycle (AGDE, Citation2022), enable teachers to collect and analyse information about children’s learning. This planning cycle includes the five components of Observe, Assess, Plan, Implement and Evaluate that support educators to plan, document, respond to and support children’s learning. With the knowledge gained from adhering to the planning cycle, educator’s thinking about children’s experiences is more deeply informed and improvement of practice to develop and implement a curriculum that is inclusive of all children occurs (AGDE, Citation2022). Through documenting multiple cycles, over time a curriculum based on the children’s capabilities and interests emerges.

To frame the approach to emergent curriculum, this analysis builds on Fleer’s (Citation2010, p. 565) view that ‘the main purpose of science curriculum in early childhood education is to give young children a new perspective of/on their surroundings’. This paper therefore responds to two questions:

What are teacher's experiences of an emergent science curriculum in bush kinder setting?

How does an emergent science curriculum develop within bush kinder settings?

Literature review

Emergent curriculum in science education

An emergent curriculum is an open-ended style of teaching and learning (Sampson & McLean, Citation2021). Facilitating collaborative teaching and learning between educators and children that can focus on a child’s ideas, questions, development, and topics of interest, an emergent curriculum is often child-centred, and of great value to children’s learning and development through creative and imaginative experiences across contexts (Card & Burke, Citation2021; Nxumalo et al., Citation2018). Children’s ideas and processes of meaning-making become pivotal to learning and form part of shared curricula with educators who support the mutual construction of knowledge (Edwards et al. (Citation2012) cited in Nxumalo et al. (Citation2018)). The term ‘emergent curriculum’ is inherently contradictory (Wien, Citation2008) and the course of teaching and learning that evolves can be unpredictable (Jones & Nimmo, Citation1994). This can lead to the term ‘emergent’ to be interpreted as teachers taking a passive role in curriculum development, yet to ensure the curriculum addresses individual children’s learning needs, ideas and voice, intentional teaching is central to an emergent curriculum approach. Teachers play an active role in seeking out children’s ideas, interests and questions and extending learning through ‘planful, thoughtful and purposeful’ (Epstein, Citation2014, p. 1) interactions in play. An emergent curriculum therefore grows from the opportunities available to the educator to support learning while an educator concentrates on providing support for children and their sense of agency and community. The emergent curriculum then leads to children’s ability to cooperate, research, plan and develop problem solving (Wien, Citation2008).

Many early childhood education programs, including those that embrace a ‘nature pedagogy’ (Warden, Citation2015), have been interpreting emergent curriculum with ‘some subtle differences’ (Sampson & McLean, Citation2021). Sampson (Citation2019) suggests these differences include ‘treating children as citizens who are capable of participating in society; considering children as creators of culture; thinking of the environment as a third teacher, guiding behaviour and inspiring creative thought; and creating pedagogical documentation’ (p. 7). By basing an emergent curriculum upon children’s theories and curiosities as drivers of learning, and through considering children as citizens who can participate in society, the children assume roles as creators of culture, placing the environment as a third educator, and guiding behaviour and inspiring creative thought, and creating pedagogical documentation for educators (Nxumalo et al., Citation2018; Wien, Citation2008). These fundamental and foundational ideas of the role of the educator and the child are necessary for understanding and co-constructing emergent curriculum.

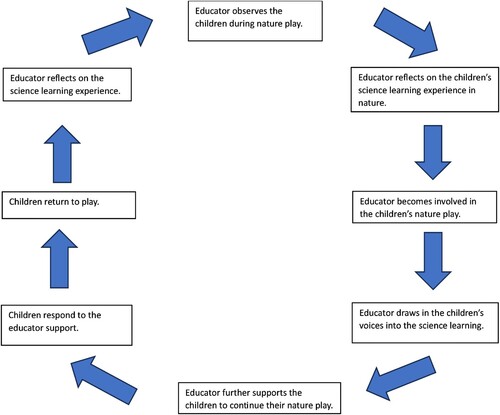

Characterised through a continuous process, emergent curriculum requires educators to watch children and listen closely to their ideas (Stacey, Citation2011). Stacey (Citation2011) has determined that an emergent curriculum can take the form of an eight-step cycle, one that often begins with educator observation and listening (). This is followed by the educators’ thoughtful response to what they are observing, which builds on what the children are doing and thinking. Following the initial observation, a period of deliberation occurs between the educator and children in which the experience or what was observed is reflected. The reflection then leads to questions being posed by the educator to the children which can include ‘What do I wonder?’ or ‘What interests me?’. These questions facilitate the educator understanding of what the child is trying to discover and how that discovery will lead to meaning making. The educator can then involve themselves in that meaning making by offering support and through that support, observe how the children react. Then, with the educator considering the children’s reaction, the educator can initiate the next steps in the learning and return to further observation (Stacey, Citation2011).

Table 1. Stages of an Emergent Curriculum Cycle Adapted from Stacey (Citation2011, p. 6).

An emergent curriculum affords opportunities for teachers and children to engage in a full spectrum of playful learning opportunities (Hirsh-Pasek et al., Citation2009; Zosh et al., Citation2018). With intentional learning goals for children in hand, children can step in and out of free play, (where play is initiated and directed by the child), guided play (where the adult establishes the context for play based on a learning intention and the child directs the play within that context), and playful instruction (where adults initiate and direct the play) providing the children with a range of playful experiences (Zosh et al., Citation2018). This range of playful experiences allows educators to adopt an emergent curriculum approach and focus on supporting children’s sense of agency and community, which includes their ability to research, plan, work together, and problem solve (Sampson & McLean, Citation2021). In undertaking their own investigations, or even through everyday play, children are often exposed to science experiences stemming from their individual curiosities. This is termed incidental science by Campbell and colleagues (Citation2023) and is an essential element of an emergent curriculum. Research continually acknowledges that ECEC educators lack knowledge and confidence to teach science (Pendergast et al., Citation2017) so building sufficient requisite science knowledge to effectively respond in immediacy to children’s questioning and inquiry whilst also being an educator who can focus their observation, showing interest in the child’s science discovery and suggesting how the knowledge can be developed further, is important. Research has demonstrated that emergent curricula in outdoor environments enable creative play-based learning of benefit to young children (Card & Burke, Citation2021). This suggests an emergent curriculum approach is well positioned for application in bush kinder settings that provide opportunities for nature-based science teaching and learning.

Children’s involvement, voice, attitudes and behaviours, can be brought to the fore in an emergent curriculum. An emergent curriculum can be viewed as a group activity that includes children and educators, one where all participants have an equal voice (Wien, Citation2015). In this collaborative environment for learning, the ownership that is given to the group to develop their learning, provides opportunities for educators to build an ‘envelope of safety’ (Wien, Citation2015, n.p.) for children. By allowing children to give voice to their own learning, educators are provided with opportunities to respond to children’s reactions to what is occurring around them (Stacey, Citation2011) thus altering what Sampson and McLean (Citation2021, p. 46) view as the ‘traditional adult-to-student flow of knowledge’. This becomes particularly relevant in a context such as a nature-based education environment as the educator can facilitate the potential science learning through questioning and discussion while ensuring the children’s voice can lead the thinking and meaning-making.

Nature-based education and bush kinders

Ingrained within Australian cultural traditions of outdoor learning, a nature-based education movement in the ECEC sector gained momentum in the early 2010s through the creation of a small number of ‘bush kinders’ (Christiansen et al., Citation2018). Bush kinders are a place-based context, one that gives young children the opportunity to learn among trees and grassed areas, sometimes quite open spaces are often inter-mixed with shrubbery that provides places to climb, hide, and play that include affordances and opportunities that are available for science teaching and learning (Campbell & Speldewinde, Citation2020). Contextually, bush kinders are an approach to nature-based ECEC with Australian climatic and topographic conditions in mind (Cumming & Nash, Citation2015). Bush kinder programs have been observed to occur in a range of settings from ‘green spaces’ such as parks and gardens (Barrable & Barrable, Citation2022) in urban settings to more undeveloped peri-urban and regional settings, in places that include wooded parklands (sometimes called ‘the bush’ in Australian contexts), open fields and paddocks, beach settings and public reserves (Campbell & Speldewinde, Citation2020). The bush kinder programs are often intended for children aged four to five who are yet to commence their schooling.

In Australia, bush kinder sessions take place in most weather and climatic conditions, often only postponed in strong storms or very high temperatures where the children’s safety cannot be guaranteed. A little rain does not mean that a bush kinder session will not proceed (Speldewinde et al., Citation2021). Previous bush kinder research (Speldewinde et al., Citation2020) highlights the range of pedagogical approaches that guides educators’ practice. Educators apply a nature pedagogy to the teaching and learning that is prevalent in bush kinder.

Nature-based learning or ‘nature pedagogy’ provides educators with opportunities to support children to develop skills that facilitate the ‘practice of working with nature … that sit within a set of values’ (Warden, Citation2015, p. 35). Nature pedagogy is an ‘embodied cultural approach to that is part of daily living and early childhood education’ (McLeod, Citation2019, p. 181). An approach that is child-centred and humanistic to learning and development is a tenet of nature pedagogy (McLeod, Citation2019, p. 81). McLeod (Citation2019) draws attention to nature pedagogy in Denmark, which bears similarity to observations of Australian bush kinder educators’ practices, as it is a pedagogical approach that provides children with discovery-based, child-led activities in nature supported by teacher scaffolding (Speldewinde et al., Citation2020). For example, the discovery of a small animal such as a spider or a worm often leads to a conversation about habitat, a puddle of water can encourage a discussion focused on the weather or evaporation as the puddle dries over time. Bush kinders, as a place-based learning context in which nature pedagogy can be applied, afford a richness of learning about what is available in the environment. They provide the educator to teach children how to care for the environment (Speldewinde & Campbell, Citation2023) by understanding the plants and animals that inhabit the landscape and use natural materials for shelter and food sources. Educators can apply nature pedagogy to children’s development of understanding of science skills and content knowledge as well as strengthening children’s nature connectedness and pro-environmental values (Speldewinde & Campbell, Citation2023). The use of nature pedagogy sits well with the development of an emergent curriculum as both rely on child-instigated play in the natural setting.

Methodology

Ethnography

This paper reports on a research project that adopted an ethnographic approach. Ethnography allows the researcher to take a passive and non-intrusive approach, simply observing what is occurring around them. Then at other times, the researcher can be actively positioned amid children’s play, themselves an important contributor to what is occurring (Delamont, Citation2016; Speldewinde, Citation2022). Ethnography, with its emphasis on researcher participation and involvement over an extended time, was applied in this research.

Ethnography incorporates a range of data-gathering methods which in an open, wide space can be beneficial to understanding the events that take place between educator and child (Stan & Humberstone, Citation2011). The social interactions that take place between educator and children leading to teachable moments develop over the duration of a three to five-hour, weekly bush kinder session. This project draws on data gathered as part of a longitudinal study, and its application of ethnography involved close interactions so trust building between researcher, educators and children allowed friendly researcher-informant relationships to form. We found regularly returning to the bush kinders valuable to ensure our data remained current and allowed us to observe and discuss the shifting social contexts that were occurring (Speldewinde, Citation2022).

Bush kinders are often wide-open spaces. Small research teams constituting one or two researchers can be presented with the challenge of capturing numerous, simultaneous events as they occur. Despite the potential to not see everything that is occurring at a given time, it has been confirmed elsewhere that ethnography is an appropriate research methodology for outdoor settings where children learn through their nature-play (Stan & Humberstone, Citation2011). Ethnography applies ‘a particular set of methods (a toolkit)’ (Madden, Citation2017, p. 25). This toolkit was adaptable, allowing us to draw upon research methods including participating, observing, listening and conducting interviews. This paper analyses 32 transcribed semi-structured interviews, transcribed informal on-the-spot discussions, researcher participant observations written into a researcher journal supported by photographic images of play and teaching. This range of data allowed us to interrogate the shifting relations between children, and early childhood professionals and how the emergent science curriculum was applied.

Bush kinder settings and participants

This research project commenced in 2015 and was undertaken at four bush kinders located in the rural Sandy Shores Shire (pseudonym) of south-eastern Australia. Bush kinders located at Chatlock, Sunrise, Wicklesham and Whitesands (pseudonyms) participated in this research during 2015, 2017 and 2020. Each bush kinder exhibited dissimilar characteristics in terms of the landscape and what was available for teaching and learning. In 2023, we returned to Sunrise and Whitesands and added a new bush kinder to the study (Greenfields). Greenfields bush kinder is in the major city of Melbourne. Two of the three bush kinder sites visited in 2023 (Whitesands and Greenfields) were set away from the regular kindergarten, Sunrise was adjacent to the regular kindergarten site. The data applied in this paper is drawn from the 2017 and 2023 visitations to the bush kinders at Greenfields, Chatlock, Sunrise and Whitesands.

Over the duration of this study, the authors both individually but on occasions jointly, undertook approximately one hundred and fifty visits to the bush kinders that focussed on the educators and several hundred children. At each bush kinder site visited, three or four educators were present, one of whom was a lead educator and each bush kinder group comprised between 16 and 25 children per session. The early childhood education professionals who taught in the bush kinder were all experienced and lead educators were all degree qualified.

In 2015 and 2017, we (authors one and three) visited the bush kinders four to six times per ten-week term for three terms. In 2020, author one conducted additional visits to extend the data so we could understand what further developments had occurred in the bush kinders. The COVID pandemic curtailed further planned visits until 2023 when author one conducted a further thirty-five visits to four bush kinders for three kindergarten terms and interviewed eight bush kinder educators to develop an understanding of how emergent curriculum is enacted. By 2023, the educators we worked with in this research had experience ranging from three to eight years of bush kinder teaching practice. As a natural environment in the outdoors subject to considerable seasonal changes, we were cognisant of attending the bush kinder at different times of the year so we could observe the different experiences the educators and children would be involved in at their bush kinder.

Procedure

Once the appropriate authorities had granted us approval to conduct the study, we met with the educators to establish the research protocols. The agreed protocols incorporated one semi-structured interview and researcher participant observation. During the interview, participants were asked three questions specific to this inquiry:

How is learning and teaching (of science) being enacted in a bush kindergarten?

Are you aware of the term ‘emergent curriculum’? If yes, what does it mean to you as an educator working in a bush kinder setting?

What is available in the bush kinder environment that provides opportunities for children’s learning?

Then during the fieldwork, informal discussions occurred during which the researcher elicited the educators’ thoughts on how emergent curriculum was occurring during the bush kinder session.

Analysis

The data that follows is presented via interview quotes from educators and three vignettes that are drawn from observing and participating in the bush kinder session. The three vignettes are provided as examples of how children’s play can lead to educators applying an emergent science curriculum thus deepening children’s understandings of physical, chemical and biological science in nature. The three vignettes were selected from many dozens of rich examples to support the narrative of this paper as they are representative of the science learning activities occurrences that would consistently occur in a bush kinder. They were chosen as they individually represent physical, chemical and biological science learning in action, and they support us to demonstrate the teachers’ experiences of an emergent curriculum in bush kinder setting and the science teaching and learning that can develop through an emergent curriculum within a bush kinder. The ethnographic data gathered through interview and participant observation provided here is analysed thematically (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We looked for common themes to understand how educators experience an emergent curriculum and how educator practice and the events we observed can (re)interpret Stacey’s definition of emergent curriculum within a bush kinder setting. Then, the data from the vignettes is analysed through applying Stacey’s (Citation2011) eight-step emergent curriculum model.

Findings

The following sections present the analysis of educator interview data and three vignettes to highlight how educators understand the experience of an emergent curriculum and how an emergent curriculum applied in a bush kinder setting supports early childhood nature-based science education.

Interviews

Thirty-two interviews conducted with twenty different educators between 2015 and 2023 were thematically analysed leading to the identification of four themes. Some educators were interviewed on separate occasions across the duration of the study (for example, one educator was interviewed in 2017, 2020 and 2023) and throughout the study, the educators, in considering how they interpret an emergent curriculum, have noted the critical role the child plays in the learning. The resultant four themes that became apparent were: that the characteristics of an emergent curriculum included both student-centred and teacher intentionality; spontaneity in both children and teachers was important to the application of an emergent curriculum; the need for familiar surroundings for an emergent curriculum specific to bush kinders and; children’s free play being important in facilitating an emergent curriculum.

In the section that follows, the themes, as they became apparent, will be discussed supported by the teacher’s voice from interviews in relation to an emergent curriculum.

Student centeredness and teacher intentionality within an emergent curriculum in science

All educators were enthusiastic about the opportunities available for children’s involvement and learning occurring during a bush kinder session. They expressed their understanding of how emergent curriculum in science education occurs in a bush kinder setting while understanding the important critical and intentional role that they play as educators working with children. The educators also acknowledged how the changing nature of the setting supports the development of emergent curriculum.

It is student centered, but educator supported (Maria, Greenfields, 2023)

It’s about that sort of teaching and learning changing every week, and I think that that sort of being able to think on your feet is really a part of that. So, you’re not dictated by, we’ve got to do this today or that today … (Maria, Greenfields, 2023)

Emergent curriculum to me means that the curriculum is evolving and changing depending on the interests of the children but it also changes with me as the educator and what they might be interested in but they might be leading it or I might say something like, I saw this really cool thing in pictures, does anyone want to try it … I probably would do more emergent than child-led (Rebecca, Whitesands, 2023)

Emergent curriculum is so relevant to bush kinder, that child-led learning, having their interests and developing your curricula around that … (if there’s) an interest (for the child) where do we go from that … you can take that a lot further. It might lead to a dead-end, they may have discovered all they want to discover and your intentional teaching, if you spark interest with two or three children, you can take that further (Kelly, Sunrise, 2023)

Spontaneity when enacting an emergent curriculum

The importance of spontaneity when enacting an emergent curriculum was noted:

It’s what we do a lot of the time. I feel like I’m quite good at it because I’m a spontaneous educator at bush kinder. So, what the children are bringing to you, and you are developing what they (are learning), so it is child led I suppose. If I can see, for example, at bush kinder they are looking at bugs or let’s get the magnifying glass, I involve them in getting them, let’s find them. (Emma, Greenfields, 2023)

Emma stated that taking an emergent curriculum is what she does consistently making it more than an occasional occurrence. Yet, an emergent curriculum requires educators to be spontaneous (Jones & Nimmo, Citation1994) and willing to be adaptable to what interests the children exhibit according to Emma. This adaptability is particularly important if we are to work in a nature-based setting that is constantly changing with the seasons.

Familiarity of surroundings as important in an emergent curriculum

Being aware of what supports the enactment of emergent curriculum, and a familiarity with the surroundings was important:

… even just the walks along the beaches, just being familiar with all the things that I just wouldn’t have known that can be discussion points. Just more of an awareness. Yes, you have your free play but with what the children are actually using and manipulating, (it’s important) to have a bit of a background on what they’ve got their hands on. (Angie, Chatlock, 2015)

Free play as a facilitator of an emergent curriculum

Being reliant on only what nature provides for teaching and learning what noted as was the preferred approach of using free play as part of an emergent curriculum:

I’ve stopped taking too much stuff (for the children to play with). I used to take binoculars, I used to take magnifying glasses, and books and charts and then I’d put them out but then the children would just use those and not actually free play … So I’ve stopped taking them or I might take them and just hide them and see if anybody actually wants them. But when I did the Bush Kinder training, because they tend to do schools as well, they have more intentional outcomes, where they might do whittling, and they might do things like that. (Laurel, Sunrise, 2017)

Here, Laurel understood the merits of an emergent curriculum as being one where she only draws on what nature provides to enable the children to learn science. Laurel has taken the opportunity to remove all the tools which could be viewed as valuable for learning such as magnifying glasses and pushing the children towards developing their own ways to investigate the science evident in nature. Relying on only what nature provides is often the approach bush kinder educators apply in their teaching approach to nature-based ECEC (Speldewinde, Citation2022).

Through analysing the interview data, we gained an understanding of how an emergent curriculum in bush kinders is viewed by educators. We came to understand from the analysis that, much like Card and Burke’s findings (Citation2021), educators’ applications of an emergent curriculum are determined by the children’s capacity to play in a spontaneous manner amongst familiar surroundings where teachers can be intentional in their teaching interactions with the children.

Vignettes

The following vignettes demonstrate occurrences of an emergent curriculum leading to intentional science teaching. We have selected three events, articulated here as individual vignettes, one to show each of biological, chemical and physical science learning at bush kinder.

Biological science

Eliza and two other girls had spent time sitting on a large fallen tree limb during a session at Sunrise Bush Kinder. The limb had been trimmed to remove the sharp edges so that it would be safe for the children to play around. The girls decided they would try and walk along the limb, balancing on the limb and jumping off the end of the log. Eliza jumped and began to stare at the end of the log. She started to point to the circles that formed the tree rings. Eliza used her finger to follow each ring, staring intently. While this was taking place, Kelly, the educator, observed what was happening. Standing next to me (Author one), Kelly told me that she had wondered about the tree rings and whether the children would notice them. This awareness, she told me, led her to do some internet searching, as she wanted to know more about tree rings. Kelly approached Eliza to ask what she was doing and what she had noticed. Eliza was unsure of why the circles were there. Kelly asked why she thought the rings were visible, what were the reasons the tree would have these circles inside of it ()? Eliza stated that it might have something to do with how the tree had grown. Eliza began to ask questions of Kelly. Would the tree grow wider? Does the tree bark have a function? Kelly said that they could investigate what the tree rings do to help the tree at their next kindergarten session. The two other girls also joined in the discussion with Kelly who gave all four girls the opportunity to talk about how they understood that trees grow. One girl, after thinking, asked Kelly ‘Does this mean we can work out how old the tree is?’ The girls began using their fingers to feel the cut section and after counting and deduced the tree was at least ten years old. After a few minutes of further questioning, Kelly took the girls over to a smaller tree to explain more about how plants and trees grow. Eliza noticed that the bark on the smaller tree was peeling off which generated further discussion on tree rings and tree growth. Tired of the discussion, Eliza and her friends ran away to a different area of the bush kinder but they were observed to remain interested in the different trees for the remainder of the session. Kelly and I resumed talking and walking and we chatted about the learning experience of the science of plant growth and how it would be something she took back to the kindergarten sessions.

Physical science

During another session at Sunrise Bush Kinder, a group of children were climbing over two large fallen logs (). These logs were slippery as there had been some overnight rain. Occasionally, one of the children would topple off and land on the soft ground then dust themselves off and rejoin the play. The children falling concerned one of the educators, Laurel, who informed me she was worried one of the children would hurt themselves. Despite the potential for injury, Laurel had also identified that there was an opportunity to teach the children about gravity and why they were falling to the ground. I asked Laurel if any of the children had fallen and been injured, and she had not experienced any child being injured. Finally, another child slipped, and Laurel felt compelled to become involved in the play and moved towards the children. Laurel asked the children to stop playing for a few minutes and then spoke to them about what they were sensing as they fell onto the ground. She asked the children ‘why do we fall down’? One boy said the log was wet and another boy stated that they weren’t being careful enough. A girl replied that it had something to do with gravity, so Laurel immediately asked if any of the children knew what gravity is? Laurel then handed each child a stick and a small rock and explained that gravity is the force that pulls objects to the Earth. She asked each child to throw their stick and rock, upwards and watch what happened. Laurel asked the children what they saw and why they thought the projectiles were falling to the ground. She also asked the children to tell her what they thought would happen if we didn’t have gravity. One child responded he would float away. The children, now keen to play elsewhere, bored with talking about gravity and balancing, moved on into different groups in other parts of the bush kinder. Laurel reflected that the play equipment at the kindergarten also posed balancing challenges and she would embed this discussion later in the week at kindergarten.

Chemical science

As soon as two boys arrived at Whitesands Bush Kinder, they asked Rebecca their educator if they could use their water bottles as they wanted to make some mud balls. Rebecca turned to her fellow educator Rochelle and said ‘off they go to their chemical laboratory again’. Rebecca, Rochelle and I watched as the boys began by digging a small hole and using the loose earth at the edge of the hole to mix with water to make mud. Rebecca had left the boys to work on their mud and we talked about what was happening and how Rebecca could use this as a teaching opportunity. After five minutes, Rebecca decided she wanted to join in and talk to the boys about the different consistency of the mud and what charactistics the mud needed to have to create a good mud ball. Rebecca did not take a hands-on role in the mud mixing, standing back and questioning the boys as the mud ball emerged from the mixing of the water in the hole. Rebecca asked the boys what would happen if they added too much water. One boy said it would be too wet and they would need to add more earth. Rebecca asked the boys what they thought would happen if different volumes of water were added to the mud to see what would happen. One boy replied, too much water would make a slush, so that it could not be formed into a ball. The mixing and the discussion continued for a further fifteen minutes, all the while Rebecca asked questions and the boys responded about what they were experiencing. The boys had intended to throw the mud ball at a tree to see what would occur and eventually, they ran off, mud balls in hand to search for a tree to hurl their mud balls towards ().

Emergent curriculum cycle in bush kinder

On the occasions provided here in the vignettes, Kelly, Laurel and Rebecca had to be adaptive with their thinking and apply intentionality to the science they were exploring with the children. aligns key excerpts from the vignettes with Stacey’s (Citation2011) 8-step emergent curriculum cycle. Within each vignette, a process was occurring that resembled Stacey’s (Citation2011) model. In addition, we have identified nuances specific to a nature-based ECEC setting. Across the three vignettes, similarities are evident with the opening stages of the emergent curriculum cycle. All three educators began by keeping their distance and observing the children during their nature play (Step 1). By observing they could then reflect on what occurring before becoming involved (Step 2). Having another educator, either author one, as was the case with Laurel and Kelly or Rebecca who spoke to Rochelle, shows that having time to reflect is important gave each educator the time to think further on what they needed to know so that intentionality could be built into the next steps of the teaching (Step 3). In the example of biological science, Kelly spent time allowing the children’s voice to become an important component of learning about tree circles and plant growth. In all three examples, each educator needed to comprehend what it was that the children were investigating and what they were inquiring about (Step 4). Steps 5 and 6 occasion the children to include their voices in the teaching. For example, Laurel’s application of an emergent science curriculum that focussed on gravity gave rise to the children voicing their ideas of science. Likewise, Rebecca’s decision to stand back, reflect then apply an emergent curriculum by entering the children’s chemical science learning of mixing earth and water to make mud gave the children the opportunity to add their voice to their learning. In each instance, the educator’s intentionality in their teaching included opportunities to draw out the children’s voices.

Table 2. Data analysis table using an 8-step emergent curriculum cycle.

The children’s voices became apparent through Stages 6 (further support) and 7 (children respond). The questioning and discussion that took place at this time in each vignette added to the richness of the children’s voices. For example, when Eliza was asked about the tree circles by Kelly, she was able to articulate that she thought they had some function in tree growth. Laurel in her discussion with the group of children regarding falling off a log, was able to elicit the word ‘gravity’ from a girl which led to the conversation and demonstration with sticks and small rocks of falling objects found in the bush kinder. Rebecca was similarly able to draw on the children’s voice during the discussion of the mud and one boy was able to mention that the amount of water influenced the chemical reaction between the earth and the water. The ensuing conversations that occurred with the children allowed Kelly, Laurel and Rebecca to provide additional support to each child which allowed for further play to occur and for the children to deepen their knowledge of science through nature play. They also allowed the educator to consider how the children responded (Step 7). The response in some vignettes was that the children returned to their play for some time as a response to the educator support and by the time the teaching had ended, we had witnessed the children, along with the educator, demonstrating their capacity to problem-solve as described by Wien (Citation2008). Kelly, Laurel and Rebecca then reflected on the learning experience and moved away from the children allowing for the current experience to continue or for the children to move away and commence a new learning experience through play (Step 8).

Discussion

Through this research, we have sought to identify how teachers experience an emergent science curriculum in bush kinder and how science teaching and learning develop through an emergent curriculum within this setting. Drawing on children’s voices while undertaking science play in bush kinder is critical as that voice incorporates elements such as a child’s desires and preferences for play (Murray, Citation2019). Educators once aware of a child’s interests can initiate an emergent science curriculum to build on the child’s science knowledge. The thematic analysis of interview data undertaken here allowed us to identify how educators experience an emergent curriculum for science learning that occurs in bush kinder settings. We found that the educators understood the importance of the children’s voice and their need to incorporate intentionality in their actions during bush kinder science teaching and learning. A child’s familiarity with a bush kinder setting and their capacity to play with spontaneity, then learn through that play, were pivotal in supporting educators to facilitate an emergent science curriculum.

The bush kinder setting has been shown to contribute to children’s science learning by allowing them to explore, to investigate materials and draw their own conclusions (Campbell & Speldewinde, Citation2020) then giving rise to their voice by orally confirming that science learning with an educator (Murray, Citation2019). As we interviewed, spoke to, and observed the educators, we began to understand that our research was confirming that an emergent curriculum was being implemented that was allowing children to voice the science understandings they were developing whilst spending time in bush kinders. Our interview data alerted us to the fact that the educators were cognisant to what is defined as an emergent science curriculum. Complimenting Nxumalo et al.’s (Citation2018) work, the educators in this study saw the value of young children’s voice in an emergent curriculum, and placed particular emphasis on their own role and intentionality of their teaching. It was the intentionality we witnessed during the educators’ teaching that led to our deeper understanding of the evolving and changing nature of an emergent science curriculum.

The interview data allowed for the development of a clearer understanding of how an emergent science curriculum is interpreted by the educators. Understanding how the educators experienced emergent curriculums allowed us to determine if processes resembling Stacey’s (Citation2011) theories had been adopted in bush kinder sessions. Our analysis of three vignettes demonstrated that a process was occurring that resembled Stacey’s (Citation2011) work, along with nuances specific to the bush kinder settings in which the research was conducted. The bush kinder sessions provided many examples of children questioning and discussing science with their educators during play. Nature-based contexts provisioned children with opportunities to learn about biological, physical, and chemical sciences and for the children with educator support, to research, plan, work together, and problem solve (Sampson & McLean, Citation2021). In undertaking their own investigations with the educator support through an emergent curriculum, the children were exposed to incidental science experiences and began to ask questions of the educators who could intentionally extend children’s science knowledge. The myriad opportunities to learn through play, in addition to those described here, created opportunities for children to develop new understandings in relation to science concepts surrounding weather, plants, small animals, mixing and forces, as well as science process skills such as observation, predicting and comparison (Guarrella, Citation2021).

Elsewhere, we have reported that natural settings like bush kinders (Speldewinde & Campbell, Citation2022) provide children with features unlike those in a conventional kindergarten. This leads to educators and children having more space and more opportunities to be creative. To develop a more thorough understanding and to analyse the vignettes, we considered elements from Stacey’s (Citation2011) emergent curriculum model. Stacey’s model was selected for application here due to its cyclical and dynamic nature. The analysis of educators eliciting children’s voices during science learning at bush kinder was influenced by Stacey’s notion (Citation2011) of an emergent curriculum and the processes that occur when an emergent curriculum is applied. With the educator at the centre, supporting the learning that was occurring, Stacey’s work allows us to conceptualise what we witnessed taking place during the bush kinder session.

Our data demonstrates that the elicitation of children’s ideas by educators enables a greater variety of voices leading to more complex thinking and facilitating the application of an emergent science curriculum. The vignettes provided here were therefore selected from the data to demonstrate the importance of an educator implementing an emergent science curriculum. The vignettes also suggest that through educator application of an emergent curriculum, children can give voice to science ideas in the environment where natural phenomena are the catalyst for a child’s play (Berrington, Citation2012; Davis & Waite, Citation2005).

Our data demonstrates an emergent curriculum for nature-based science education in early childhood was being enacted that could be broken down into a similar eight-step cyclical model specifically for nature-based spaces (). Each of the vignettes exhibits steps in the model of bush emergent science curriculum. Using key moments in the vignettes as indicated in , we can tabulate those to correspond with the steps in the model.

Through interacting with the environment and their intentional teaching, educators can develop an emergent curriculum that incorporates the children’s voices as the children build their understanding of science concepts evident in nature. The unpredictable nature of the learning as described by Jones and Nimmo (Citation1994) came to the forefront in each learning opportunity. The educators’ science content knowledge, such as the understanding of how trees grow and the chemistry of mixing different substances and their ability to scaffold the children to experiment, test, and explain, were apparent in the bush kinder during nature play. The advancement of the children’s science knowledge, that is, demonstrated through the subsequent play then has the potential to lead to the cycle of an educator’s application of the emergent curriculum cycle to recommence.

Elsewhere (Speldewinde et al., Citation2021) it has been observed by the researchers that bush kinder educators’ pedagogical approaches play an important role in fostering children’s noticing of nature. This new paper provides a way to now conceptualise how educators can enhance that noticing through the application of an emergent science curriculum. Applying an emergent curriculum (Stacey, Citation2011) for science teaching and learning and following the steps in the emergent curriculum cycle in nature-based education (), affords opportunities for children to apply their voice and articulate their learning, whilst interacting with every aspect of the outdoor environment. The eventuality of educators allowing children’s voices to be apparent through an emergent science curriculum during bush kinder sessions provides those children with the potential to be more confident in their understandings of science in nature and potentially for educator support to allow for effective science teaching and learning to occur in nature-based settings.

Strengths and limitations

The small number of field sites is a limitation in this research. Additionally, this paper applies data in a cross-sectional manner, drawing on specific incidents at a point in time. However, we mitigate these limitations through the longitudinal aspect of the study and the ability to return to the bush kinders multiple times assisting us in building a robust understanding of what occurs in and during bush kinder sessions. Over the duration of this study, we have dealt mainly with the same educators. Despite the small number of sites that participated in this research being a restricting factor, the seasonal changes in the bush kinder environment provided a wide-ranging experience. Rather than it being a static place for learning and teaching, seasonal changes led to children’s differing interests being piqued, so we were able to generate a diverse range and volume of data for analysis.

Conclusion

The wide panorama of a bush kinder has proven to be a context that can provide many opportunities for science learning. The learning is only limited by the seasons, weather and the boundaries educators establish so the children remain safe and within sight. This paper set out to develop an understanding of the intersections between an emergent curriculum, teacher’s experiences and science teaching and learning in bush kinders. It drew on research literature, and we found that an emergent curriculum is more than child-led learning, as it is occasionally misinterpreted to be. By analysing our data, we highlighted the important role that educators play and that their intentionality in providing science teaching and learning experiences can be an important component of a bush kinder session. The interview data provided an understanding of how we can extract themes pertinent to what educators view as being necessary to implement an emergent curriculum. These themes are that an emergent curriculum incorporates student-centredness and teacher intentionality, spontaneity in both children and teachers, the need for familiar bush kinder surroundings and children’s free play, all contribute to what constitutes an emergent curriculum. Through our analysis of three vignettes which are representative of the play-based learning that occurs in a bush kinder, an emergent curriculum can be described and then categorised into the eight teaching and learning stages that take place when an emergent curriculum is implemented by an educator. For children to develop a sense of agency, they need to feel that their voice is heard and viewpoint valued. The vignettes demonstrate that children’s voice is activated by enacting an emergent curriculum but this activation is predicated on the intentionality that is a necessary component of the educator’s teaching practice in a bush kinder.

Potentially the links between children’s voices and an emergent curriculum with intentional teaching need to be further clarified for educators in bush kinders. This may lead to greater knowledge of the impact of their interactions with children. Where there exists potential for future research is considering the science teaching and learning opportunities overlooked in the bush kinder environment. The educators we observed were very experienced and, some had almost a decade of bush kinder teaching experience, what may be worth consideration elsewhere are educators that lack experience, knowledge and confidence in science teaching and how this compares to the educators reported on here. There is also the possibility that further interrogation of our data has the potential to uncover other learning areas including literacy, numeracy and children’s social and emotional development. If, ‘the main purpose of the science curriculum in early childhood education is to give young children a new perspective of/on their surroundings’ (Fleer, Citation2010, p. 565), then a model for an emergent science curriculum in bush kinders that incorporates intentional teaching will continue to support children’s capacity to develop their science understandings.

Ethics

University Human Research Ethics approval (Deakin University (2015) # HAE_2015_016 and University of Melbourne (2023) # 2023-26094-39761-3) was gained, and local and state government research protocols were adopted. Research participation was voluntary and signed consents by the kindergarten organisation, its educators and its parents (on behalf of their children) were obtained. We made the parents and guardians aware of the study through the educators, who distributed consent documents on our behalf. We also were available prior to commencing the research and whilst on site at the bush kinders for parents to discuss any concerns or ask questions about our research. Anonymity as a condition of participation (pseudonyms have been used throughout this paper), secure and timely data storage, and rights to withdraw from the study were offered as part of the research consent process. Between 2015 and 2020, the children’s involvement in the study was limited to observation of play and interactions with the educators. In 2023, children became more active participants in the study, with ethical approval and subsequent consent from parents for their children to be involved in the study. We remained cognisant at all times of adopting an approach to this research that ensured that the children’s play and learning were not interrupted by our presence (Speldewinde et al., Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antara, P. A. (2021). Emergent curriculum in the form of creative class in kindergarten. Journal of Education Technology, 5(2), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.23887/jet.v5i2.36342

- Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE]. (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council.

- Barrable, D., & Barrable, A. (2022). Affordances of coastal environments to support teaching and learning: Outdoor learning at the beach in Scotland. Education 3-13, 52(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2022.2100440

- Berrington, A. (2012). The impact of forest schools in Bradford. BCEP. http://bradfordforestschools.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2012/03/BCEP-Forest-School-Impact-Assessment-Report.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

- Campbell, C., Kewalramani, S., & Chealuck, K. (2023). Approaches to enhance science learning. In C. Campbell, & C. Howitt (Eds.), Science in early childhood (5th edition) (pp. 72–88). Cambridge University Press.

- Campbell, C., & Speldewinde, C. (2020). Affordances for science learning in bush kinders. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education, 28(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.30722/IJISME.28.03.001

- Card, B., & Burke, A. (2021). Outdoor kindergarten: Achieving outcomes with a place-based & land-based approach to emergent curriculum. The Morning Watch: Educational and Social Analysis, 47(1), 122–138.

- Christiansen, A., Hannan, S., Anderson, K., Coxon, L., & Fargher, D. (2018). Place-based nature kindergarten in Victoria, Australia: No tools, no toys, no art supplies. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-017-0001-6

- Cumming, F., & Nash, M. (2015). An Australian perspective of a forest school: Shaping a sense of place to support learning. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 15(4), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1010071

- Davis, B., & Waite, S. (2005). Forest schools: An evaluation of the opportunities and challenges in early years final report January 2005. University of Plymouth. https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/6/6761/Forestschoofinalreport2.pdf

- DEEWR (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations). (2009). Australian government department of education, employment and workplace relations for the Council of Australian Governments. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Delamont, S. (2016). Fieldwork in educational settings: Methods, pitfalls and perspectives (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315758831

- Dillon, J. (2016). Towards a convergence between science and environmental education: The selected works of Justin Dillon. Taylor & Francis.

- Edwards, C., Gandini, L., & Forman, G. (2012). The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Norwood: Ablex.

- Epstein, A. S. (2014). The intentional teacher: Choosing the best strategies for young children (2nd ed.). National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Fleer, M. (2010). The re-theorisation of collective pedagogy and emergent curriculum. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 5(3), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-009-9245-y

- Greenwood, D. A., & Hougham, R. J. (2015). Mitigation and adaptation: Critical perspectives towards digital technologies in place-conscious environmental education. Policy Futures in Education, 13(1), 97–116.

- Guarrella, C. (2021). Weaving science through STEAM: A process skill approach. In C. Cohrssen, & S. Garvis (Eds.), Embedding STEAM in early childhood education and care (pp. 1–19). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65624-9

- Guarrella, C., van Driel, J., & Cohrssen, C. (2022). Science education in early childhood education—Are we approaching a cure for the state of chronic illness? Research in Science Education, 33(4), 634–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-022-10087-1

- Havu-Nuutinen, S., Kewalramani, S., Veresov, N., Pöntinen, S., & Kontkanen, S. (2021). Understanding early childhood science education: Comparative analysis of Australian and Finnish curricula. Research in Science Education, 52(4), 1093–1108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-020-09980-4

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Berk, L. E., & Singer, D. G. (2009). A mandate for playful learning in preschool: Presenting the evidence. Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195382716.001.0001

- Howitt, C., & Jobling, W. (2021). Planning for teaching science in the early years. In C. Campbell, W. Jobling, & C. Howitt (Eds.), Science in early childhood (4th ed.) (pp. 221–238). Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, J. (2022). Reflecting on research; strands and provocations. In F. Hughes, S. Elliott, K. Anderson, & B. Chancellor (Eds.), Early years learning in Australian natural environments (pp. 57–75). Oxford University Press.

- Jones, E., & Nimmo, J. (1994). Emergent curriculum. National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1509 16th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036-1426 (NAEYC# 207).

- Knight, S. (2016). Forest school in practice: For all ages. Forest school in practice. Sage Publications.

- Madden, R. (2017). Being ethnographic: A guide to the theory and the practice of ethnography. Sage.

- McLeod, N. (2019). Danish outdoor nature pedagogy. In N. McLeod, & P. Giardiello (Eds.), Empowering early childhood educators (pp. 175–200). Routledge.

- Mogharreban, C. C., McIntyre, C., & Raisor, J. M. (2010). Early childhood preservice teachers’ constructions of becoming an intentional teacher. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 31(3), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2010.500549

- Murray, J. (2019). Hearing young children’s voices. International Journal of Early Years Education, 27(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1563352

- Nxumalo, F., Vintimilla, C. D., & Nelson, N. (2018). Pedagogical gatherings in early childhood education: Mapping interferences in emergent curriculum. Curriculum Inquiry, 48(4), 433–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2018.1522930

- Pendergast, E., Lieberman-Betz, R. G., & Vail, C. O. (2017). Attitudes and beliefs of prekindergarten teachers toward teaching science to young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0761-y

- Rickinson, M. (2001). Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research, 7(3), 207–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620120065230

- Salmon, A. K., & Barrera, M. X. (2021). Intentional questioning to promote thinking and learning. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40, 100822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100822

- Sampson, M. (2019). Early childhood educators shifting their understanding of emergent curriculum: “It’s about transforming thought” Doctoral dissertation, Mount Saint Vincent University.

- Sampson, M., & McLean, C. (2021). Shifting from a rules-based culture to a negotiated one in emergent curriculum. Journal of Childhood Studies, 46(1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs00202119744

- Speldewinde, C. (2022). Where to stand? Researcher involvement in early education outdoor settings. Educational Research, 64(2), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2022.2064323

- Speldewinde, C., & Campbell, C. (2022). Mathematics learning in the early years through nature play. International Journal of Early Years Education, 1–18.

- Speldewinde, C., & Campbell, C. (2023). Bush kinders: Building young children’s relationship with the environment. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 40(1), 7–21.

- Speldewinde, C., Kilderry, A., & Campbell, C. (2020). Beyond the preschool gate: Educator pedagogy in the Australian ‘Bush kinder’. International Journal of Early Years Education, 36(1), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2020.1850432

- Speldewinde, C., Kilderry, A., & Campbell, C. (2021). Ethnography and bush kinder research: A review of the literature. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 46(3), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/18369391211011264

- Stacey, S. (2011). The unscripted classroom: Emergent curriculum in action. Redleaf Press.

- Stan, I., & Humberstone, B. (2011). An ethnography of the outdoor classroom–how teachers manage risk in the outdoors. Ethnography and Education, 6(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2011.587360

- Warden, C. (2015). Learning with nature: Embedding outdoor practice. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Wien, C. A. (Ed.). (2008). Emergent curriculum in the primary school: Interpreting the Reggio Emilia approach in schools. Educators College Press.

- Wien, C. A. (Ed.). (2015). Emergent curriculum in the primary classroom: Interpreting the Reggio Emilia approach in schools. Teachers College Press.

- Zosh, J. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Hopkins, E. J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Solis, S. L., & Whitebread, D. (2018). Accessing the inaccessible: Redefining play as a spectrum. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01124