Abstract

It has previously been suggested that there is a need for a more language focused science instruction, especially in linguistically diverse classrooms, where many students are second language learners. But it has also been suggested that teachers may feel uncertainty about how to teach in ways that promote learning of both subject matter and language. Previous studies have revealed how the language of science, especially the written language of science, is used to create a certain meaning. Research on interventions shows how this knowledge, through a functional metalanguage, can be used successfully. However, few studies explore how teachers in science instruction themselves integrate a language focus in their linguistically diverse classrooms. This ethnographic case study investigates how a teacher, through her planned metalanguage activities, integrated language in her physics classrooms in Year 5. The results reveal that (1) the activities focused on the students’ literacy development; (2) the activities sometimes had an integrated language and subject focus and sometimes an isolated language focus; and (3) the students put a great deal of effort into understanding how they were to perform the various framed activities. The study has implications for how a language focus can be integrated in subject teaching.

Introduction

Migrant students constitute a heterogeneous group, with different mother tongues, educational backgrounds, and levels of the target language. However, many of these students struggle to succeed at school. This is because, to a greater extent, second language learners, have to handle the dual task of acquiring the language of instruction, while learning the content. In order for second language learners to succeed at school, teachers are expected to integrate a linguistic focus, more specifically, to integrate an explicit academic language instruction for second language learners, in their teaching. This integration places high demands, and challenges on teachers, not least teachers in science education (e.g. Weinburgh et al. Citation2014).

In science education, there has also been some uncertainty about how to integrate an explicit academic language instruction so that the language is not focused on in isolation disconnected from the subject content to be learned (e.g. Howes, Lim, and Campos Citation2009; Weinburgh et al. Citation2014).

As science is conceptually dense, due to the subjects’ required precision, it is not surprising that there is a lexical focus in science instruction. Given this context, it has been claimed that teachers have mainly focused on isolated technical terms (Richardson Bruna, Vann, and Perales Escudero Citation2007, Citation2010; Seah Citation2016; Wilson and Jesson Citation2018), and that this is due to the teachers’ limited understanding of what school science language is, and how it can be taught so as to strengthen their students’ subject learning (Richardson Bruna, Vann, and Perales Escudero Citation2007, Citation2010; Seah Citation2016).

Previous research has revealed how the language of science, especially the written language of science, is used to create a certain meaning (e.g. Halliday and Martin Citation1993), and how it becomes increasingly written-like, abstract, dense, technical, and objective over the school years (e.g. Christie Citation2012). Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) has also been used by science education researchers to further explore the language demands of science, and how these can be made explicit in the classroom (e.g. Cheng, Danielsson, and Lin Citation2020; Seah, Clarke, and Hart Citation2015; Tang Citation2016). Through intervention studies, research has shown how the use of a functional metalanguage can help second language learners to gain control of how language works in science instruction (e.g. Forey and Cheung Citation2019; Schleppegrell and Moore Citation2018). However, only a few studies have explored how teachers themselves integrate a language focus in their science instruction, together with their linguistically diverse students at the primary or lower secondary school levels. Seah and Yore (Citation2017) investigated how three science teachers made explicit references to the language of science in their linguistically diverse Grade 4 classes. Their study shows that these teachers did not just focus on basic literacy skills, but also on disciplinary literacy skills. Seah and Silver (Citation2020) investigated how three science teachers foregrounded language so as to support their students’ access to the topic in linguistically diverse Grade 9 classes. Especially one of the teachers, who participated in the study, supported the students to better understand and express the subject content by ‘consistently tun[ing] in to the students’ prior knowledge of and about scientific knowledge and their difficulties with scientific language and use’ (Seah and Silver Citation2020, 2467). Overall, more research is needed in the area of how teachers in science instruction support the parallel language and knowledge development of second language learners (Seah and Yore Citation2017). Particularly rare are ethnographic case studies of teachers in science instruction who have undergone further training in genre pedagogy and who are used to teaching linguistically diverse classes.

This study is set in Sweden, where around 25 per cent of the students in Year 1 to 9 are born abroad or have two foreign-born parents (The Swedish National Agency for Education, 2019/Citation2020). This means that many students in Swedish schools are second language learners and educated through their second language. However, previous studies in Sweden, as well as abroad, demonstrate that teachers in science education face difficulties in identifying what language to focus on, and figuring out how and when to integrate that language in the context of content instruction, where several students are second language learners (e.g. Seifeddine Ehdwall and Wickman Citation2018).

The Swedish National Agency for Education has been given the task of providing systematic support to enable schools to offer students who have another mother tongue other than Swedish an equitable education of high quality. Before supporting actions are implemented, it is important to closely examine examples of how teachers integrate a linguistic focus into their instruction. This understanding can also give better information about the design of interventions that seek to promote language and content-integrated learning for students taught in their second language.

This article focuses on a teacher, Karin, and her communication with her students (aged 11–12) in a physics classroom. Karin identified herself as having a language focus in her science instruction, and as being used to teaching linguistically diverse classes. The study investigates: (1) which metalanguageFootnote1 is used in planned metalanguage activities, and (2) how the communication of metalanguage relates to subject-specific content and the learning opportunities revealed in these activities. This ethnographic case study contributes to previous research by showing how a teacher, who had a language focus in her science instruction, and was used to teaching linguistically diverse classes, integrated a linguistic focus in her physics classrooms in Year 5, through planned metalanguage activities

Theoretical framework

Every subject at school has its own activities and texts, which are connected to how knowledge is presented and dealt with. The specialized written language of science is often described in terms of linguistic density, objectivity, a high degree of abstraction, creating a distilled and objectified world (Halliday and Martin Citation1993). The point of departure in this article is that learning science entails not only learning science through language but also learning about the language of science (Halliday Citation1993). Halliday (Citation1993) explains that, with gradual control of different lexicogrammatical meaning potentials, students learn to understand and express increasingly abstract and objectified meanings, which, in their turn, improve conditions for learning. For example, access to the lexicogrammatical meaning potentials that express generalizations, such as a move from the specific to more general terms, provides increased conditions to refer to a class. Through a gradual understanding and control over the meaning potentials, students learn to understand and express an increasingly abstract and specialized meaning. SFL offers explanations of what language resources, that is, lexicogrammatical resources, could be used to create a certain meaning in a certain context, for instance how the academic registers of schooling are created (Christie Citation2012; Halliday and Martin Citation1993).

Metalanguage can be used by teachers to show how lexicogrammatical choices create meaning (Christie Citation2012; Halliday and Martin Citation1993). For instance, teachers can explain why nominalizations are a common resource in science. By transforming a process (such as ‘move’) to a nominalization (such as ‘motion’) there is an entity that can be measured, generalized over, and classified. Using metalanguage can be especially beneficial for second language learners who are not as rooted in the target language: ‘what best supports language development is meaningful interaction, with frequent opportunities for learners to attend to and use new forms, guided by explicit talk about language and meaning’ (de Oliveira and Schleppegrell Citation2015, 118).

In this study, I employ the concepts an integrated language and subject focus (Uddling Citation2019) and an isolated language focus to analyse different linguistic foci in Karin’s planned metalanguage activities. The concepts applied here correspond to Bernstein’s concepts of weak classification and strong classification (Bernstein Citation2000). A weak classification between metalinguistic knowledge and subject-specific knowledge integrates the learning objects with each other, whereas a strong classification between metalinguistic knowledge and subject-specific knowledge keeps the learning objects separate from one another (cf. Bernstein Citation2000). To deepen the understanding of how the communication of metalanguage relates to subject-specific content, and the learning opportunities revealed in these metalanguage activities, I also used Bernstein’s (Citation2000) concept of framing. Thus, framing is coupled with classification, and used to further illustrate the didactic choices that were made by the teacher.

In fact, there are many points of contact between SFL and Bernstein’s sociological framework. These points of contact include similar explanations of how language varies in accordance with social origins and social functions. Both frameworks argue that every student, regardless of his or her background, should be given access to the language demands of schooling. One way to compensate for a student’s different condition is explicit instruction. Genre pedagogy (Martin and Rose Citation2008), which is based on SFL, aims to make educationally valued genres explicit.

Materials and methods

The data of this study was collected within an interdisciplinary project, funded by The Swedish Research Council, called ‘Multilingual students’ meaning-making in school physics and biology’. Schools with a high proportion of multilingual students were contacted, and at one of these schools Karin agreed to participate. She was trained to teach mathematics and science subjects, in Years 1-7, and in Swedish as a second language. Furthermore, she was an experienced teacher who had worked in linguistically diverse classrooms for several years. She had also received training in content and language-based instruction inspired by genre pedagogy. In her physics class, in Year 5, 16 out of 21 students consented to participate, and these students reported that they spoke more than one language at home. The languages spoken at home were for example Arabic, Bulgarian, English, French, Mongolian, Somali and Turkish. Two students were newly arrived and had spent between one to two years in the Swedish school system. All participants have been assigned pseudonyms, so as to ensure their anonymity.

The data consists of classroom observations during the unit measuring time (a period of nine weeks). It comprises transcribed video and audio recordings, digital photographs, worksheets, students’ written texts and textbook texts. The audio recordings were carried out by attaching a dictaphone to the teacher. Four other dictaphones were placed on benches that were situated between four pairs of students. Video recordings were made using a main camera placed at the back of the classroom. The data also includes a transcribed audio recording of a semi-structured interview with the teacher. The interview was conducted at the end of the observation period and lasted for 33 minutes. I asked the teacher questions which addressed how she adapted her teaching to the students in the class, how she described school science language, and how she tried to further develop this language in the classroom.

The planned metalanguage activities (hereafter PM activities) that were selected for closer examination were based on identification of the activities where students were expected to speak about language on the teacher’s initiative. This meant that an activity where the students themselves requested a metalanguage, for example, a request for information on how to write an analysis, was not categorized as a PM activity. In the ‘Recap activities’, however, students were expected to participate in metalanguaging (talking about language), even though the teacher was the primary user of metalanguage, these activities were categorized as PM-activities. Two of the PM activities that were identified, namely, ‘Dictogloss from a textbook text’ and ‘Reading and finding advantages and disadvantages about the use of hourglasses, as expressed in a textbook text’, were referred to by Karin in the interview as ‘planned linguistic activities’ (Swe. planerade språkövningar). During Karin’s 22 observed lessons (16 hours of video recordings and 93 hours of audio recordings), I identified nine different types of PM activities. Eight of these are included in this article (see ).Footnote2 also describes which metalanguage Karin used and what metalanguage students were expected to use in the different PM activities.

Table 1. The types of PM activities and the metalanguage that was used.

The analysis of the PM activities began with an examination of the overall result of the metalanguage used in the PM activities. I analysed (a) whether words, grammar and/or texts were talked about; and (b) if the metalanguaging included talk of how the lexicogrammar creates meaning.

In the second step of the analysis, I investigated what learning the metalanguaging in the PM activities might offer the students in terms of whether there was an integrated or an isolated linguistic focus. When language is used as a tool for students to learn about the language that carries the content, while learning the subject content through the language, there is an integrated language and subject focus (Uddling Citation2019, 19), i.e. focusing on the linguistic meaning potentials that support particular subject learning. For example, this occurred during the students’ individual reading session, when Karin made it explicit how the disadvantages (of hourglasses) were expressed with the word ‘problem’ in a textbook text. When the language is focused on in isolation, disconnected from the subject content to be learned, there is an isolated language focus. This happened, for example, during a text-talk, when Karin was preoccupied with her questions being answered, through the use of a certain word, and not accepting the student’s reformulations that covered the same content as correct answers. This resulted in the loss of content focus (Uddling Citation2019). When analysing whether there was an integrated or isolated linguistic focus, I mainly focused on whether the metalanguaging that took place helped the students to better understand or express the subject content.

In the third step of the analysis, I used Bernstein’s (Citation2000) concept of framing (cf. Love and Simpson Citation2005). Framing relates to how Karin controlled the communication of the learning objects in the PM activities, and specifically how she controlled what language students would use to perform a certain activity. This, in turn, relates to the learning opportunities that were revealed in the activities. A strong framing means that Karin was in control of the communication in the activities, whereas a weak framing means that there was more room for students to negotiate how to communicate and use metalanguage in the PM activities. For example, the framing was strong within an activity when students were instructed and controlled by the teacher to talk about language in a particular way.

Thus, the first step of my analysis examined which metalanguage was used in planned metalanguage activities, and the other two steps examined how the communication of metalanguage related to subject-specific content and the learning opportunities revealed in these activities. The digital photographs, students’ written texts, and worksheets were collected to confirm or complement the recordings. For example, when analysing the PM activity ‘Planning and writing a recount of a school day without any clocks’ the collected worksheet made it possible to compare the worksheet´s use of ‘summary’ with ‘re-orientation’, as stated by Karin in her review in the beginning of the lesson. When analysing ‘Putting strips from a cut-up text in the right order’ and ‘Constructing sentences concerning the revolving of celestial bodies related to time, such as a day and night, a month and a year’ the photographs made it possible to see some of the sentences that students had put together in pairs. When analysing ‘Argument developed in writing concerning the choice of a sundial or a clepsydra’, the students’ written texts gave examples of how the students had formulated their arguments. Thus, I have used the diverse data sources to gain a more nuanced understanding of how the different PM activities were performed.

In order to include Karin’s didactic reasoning in my analysis, I related the results from the classroom observations to what she had said during the interview. Her expressed linguistic focus and views about the planned linguistic activities may enhance the credibility of the claims made from the lessons observed.

The analyses were carried out in Swedish, which enabled me to follow what the teachers and the students expressed verbatim. The results were later translated into English.

The metalanguage used in the PM activities

The unit measuring time was built up over a period of nine weeks. The subject content was processed in the following order: how to measure time before there were clocks, imaginary consequences of not having any clocks, the rotation of the celestial bodies and what they give rise to (day, night, month, year and seasons), investigations of how different types of clocks measure time and the historical development of clocks (sundial, clepsydra, hourglass, pendulum clock, mechanical clock, atomic clock) and humans in space.

The findings start with presenting the PM activities overall before zooming in on the two types of an integrated language and subject focus and an isolated language focus. lists the types of PM activities that Karin used, except for the textbook talks, and whether these activities were performed by the whole class, in pairs, or individually. The table also describes what metalanguage Karin used, what metalanguage the students were expected to use in the different PM activities, whether the metalanguaging used contributed to an integrated language and subject focus or an isolated language focus, and the number of times a certain type of PM activity was performed.

The overall results, based on the whole data set, revealed that both SFL’s grammar terminology, in itself meaning-based, and a more traditional grammatical terminology, were used in the PM activities. For instance, SFL was used to explicitly explain the meaning of processes and participants, and the processes that are often used to describe something. The more traditional grammatical language was used when Karin mentioned that a recount is written in the past tense, and that students could put the text strips together by looking at the tense of ‘being used’.

The metalanguage used in the PM activities suggests that Karin had a broad language focus. She focused on words, grammar, and text. When focusing on words, she talked about subject-specific words like ‘frequency’, ‘time measuring instruments’ (Swe. ur), and unusual words like ‘mass’. When she was focusing on grammar, she explained processes and participants, and how disadvantages are expressed in the textbook text through the use of the word ‘problem’, how descriptions often are expressed with the processes ‘are’, ‘has’, and ‘is’, and how arguments are expressed with phrases like ‘I choose x because’. Thus, Karin explained and exemplified how the lexicogrammar creates meaning, which Christie (Citation2012) and Halliday and Martin (Citation1993) promote as an important resource in subject teaching. When Karin focused on texts, for instance, she talked about the text structure of a recount. In five out of eight PM activities, the metalanguaging contributed to an integrated language and subject focus. In 3 activities it contributed to an isolated language focus (‘Planning and writing a recount of a school day without any clocks’, ‘Putting strips from a cut-up text in the right order’, and ‘Constructing sentences concerning the revolving of celestial bodies related to time, such as a day and night, a month and a year’).

Results reveal that the different types of PM activities involved the written language of science in one way or another, such as reading, writing and orally expressing the subject content in a more written-like and decontextualized way. Karin’s use of metalanguage in the PM activities also suggests that she was fully aware that learning science entails not only learning science through language, but also involves learning about the language of science (Halliday Citation1993). She explicitly stated that the two most important genres in science education are to describe and explain. Karin also mentioned the processes that are often used in descriptions. Furthermore, she encouraged her students to use subject-specific words and generalizations, which can increase student participation in science classrooms. There was a clear expectation in the classroom that students should express the content in a subject-specific way (cf. Seah and Silver Citation2020; Seah and Yore Citation2017). Some activities, like ‘Planning and writing a recount of a school day without any clocks’, focused more on basic literacy skills. The PM activities were designed to promote both the students’ basic literacy and disciplinary literacy (cf. Shanahan and Shanahan Citation2008).

In the interview, Karin said that her knowledge of genre pedagogy had helped her to identify a subject-specific focus in her classes. This included determining how subject-specific participants and processes can be spoken about, for example, Karin wondered ‘do electrons flow or do they run or do they stream? In that way, you know’. She also said that genre pedagogy had helped her to identify what was particularly difficult in school science language, which, in turn, helped her to support her students to, for example, unpack dense nominalizations and fill out abstract concepts like ‘ecosystem’ with a descriptive content. Her linguistic focus was also evident when she reported: ‘I want the final product to be a free-standing text. It is not always the case that you get a whole text…but this is always my goal that they [the students] will be able to put into words something substantial that they have been working on’.

Karin planned which language she needed to be particularly clear about in her teaching. Furthermore, she said that she ‘in almost every lesson, tried to include a linguistic activity that would enhance the subject-specific language that she wanted to focus on’. One activity that she performed, was to set up a dictogloss where her students first would listen to the word ‘mechanical clock’, for example, and then use it:

I set up assignments where they are forced to use the words even if they have not mastered them. Mechanical clock. Mechanical clock. Yes, they heard it. This is then included in a dictogloss. They revise [it] and then they have already had the opportunity to say it a number of times, and so, yes, step by step, you know. I think it is extremely important to use planned linguistic activities which reinforce the subject language. (Karin)

According to the interview, the PM activities were carried out in order to get the students to use the subject-specific language, but it was also revealed that one of the activities, ‘Reading and finding advantages and disadvantages about the use of hourglasses, as expressed in a textbook text’, was designed to help students understand the arguments that could be found throughout the textbook text (cf. Uddling Citation2019). Both in the interview and during the classroom observations, it was revealed that Karin, in addition to having a focus on the words and grammar, she also focused on the textual level. Furthermore, several of the PM activities offered the students the opportunity to ‘put into words something substantial they have worked on’ (see the PM activities: ‘Planning and writing an account of a school day without any clocks’, ‘Recap activities’ and ‘Argument developed in writing concerning the choice of a sundial or clepsydra’).

Now zooming in on the two types of foci: an integrated language and subject focus and an isolated language focus. When focusing on the linguistic meaning potentials that support particular subject learning there is an integrated language and subject focus, and when focusing on the language in isolation, disconnected from the subject content to be learned, there is an isolated language focus.

An integrated language and subject focus

This section provides examples of two different types of PM-activities: ‘Recap activities’ and ‘Argument developed in writing concerning a choice of sundial or clepsydra’, where an integrated language and subject focus was identified.

The ‘Recap activities’ were performed regularly in the Year 5 classroom. In these teacher-led whole class activities, students were expected to express common, often practical classroom experiences with a more decontextualized and precise subject language. On one occasion, the students were expected to recapitulate what they had discovered the previous lesson, during which they had investigated which factor (the length, weight, or angle of a pendulum) affects the frequency of the pendulum. The students had experienced that it was the length of the pendulum (the length of the string) that affected how fast the pendulum was swinging ().

Except 1 illustrates how, in response to the teacher’s questions, the students made their reasoning more ‘scientifically qualified’ in terms of preciseness (turn 4, 6, 10, 16), used subject-specific words (turn 8), and expressed a general relationship (turn 16).

Excerpt 1

By using the teacher’s linguistic support, which required students to express themselves in a precise and written-like manner, the students moved forward in a more scientific discourse. Excerpt 1 also illustrates how Karin through her use of repetition (turn 5, 11), a reformulation (turn 17), and praise (turn 17) made her students’ language use visible. When their previous classroom experiences were expressed in a more written-like and subject-specific way, Karin used the students’ own language as a resource (cf. Seah and Silver Citation2020).

In the ‘Recap activities’, there were many instances where the students were encouraged to express themselves technically and precisely, and to report on general relationships and conclusions. Mortimer and Scott (Citation2003, 15) claim that ‘[g]eneralizability is a fundamental characteristic of scientific knowledge, which applies to all scientific theories and concepts’. In an associated discussion of science, Shanahan and Shanahan (Citation2020, 102) note that ‘[w]ithout precision, there can be no replication, and the whole idea of science is to create knowledge that can be replicated no matter what various scientists’ beliefs or ideologies may be’. Because science education can be seen as a recontextualization of the discipline, precision and generalizability are also important in science classrooms (Halliday and Martin Citation1993). As mentioned above, the students were expected to express the subject content in a subject-specific way, for example, by means of making generalizations, using subject-specific words, and by specifying references, all of which promoted their language and content-integrated learning.

To value the use of a certain language, Karin controlled her students’ use of a decontextualized, written-like language to express earlier classroom experiences. Thus, the framing (Bernstein Citation2000) was strong, and students had no room to negotiate which language they would use to express the subject content that they had learnt. However, Karin never explicitly told her students what the aim of the ‘Recap activities’ was, or why she valued a certain use of language in the activities over another. Whilst Karin implicitly communicated the learning objects and how they would be performed, she still controlled the communication that took place in the ‘Recap activities’.

Another PM activity, where an integrated language and subject focus was identified was the ‘Argument developed in writing concerning the choice of a sundial or a clepsydra’ activity. During previous lessons, the students had investigated how sundials and clepsydras worked. They had also talked about their advantages and disadvantages. Just before they were to write an argumentative text, the advantages and disadvantages were repeated and Karin explained to the students that this was done to make the students’ opinions more visible. In their writing, she urged them first to use ‘I think x is best because’ or ‘I select x because’, with the motivation that this is how arguments are expressed. During the writing activity, Karin supported her students individually by asking whether they would choose a sundial or a clepsydra, and by reminding them how arguments should be expressed, and to use the fixed forms. The students wrote, for example, ‘I choose the clepsydra because you can use it if it is dark and it measures the time more accurately’ and ‘I’d like to use the clepsydra. Firstly, I think the result is more accurate than the sundial. Secondly, the clepsydra can be used even when the weather outdoors is cloudy or rainy’.

At the beginning of the following lesson, Karin said that the students would improve their texts by developing their arguments. To explain what they were to do, she said: ‘I choose the sundial because it’s easy. Can I expand it somehow? What made the sundial easy? Well you just need a stick and the sun. Do not only write that it is simple, but why it is simple. Ok?’. Because they were supported or controlled by the teacher’s questions, like: ‘Why is that important?’, the students were able to justify their choice of time measuring instrument by using more developed arguments. One student explained why it was important to have the clepsydra in a room that was neither too warm nor too cold (Excerpt 2):

Excerpt 2

The teacher then encouraged the student to write down his more developed argument and confirmed that the student had identified and presented a well-developed argument (Excerpt 2). Because the metalanguage, in this PM activity, was used as a tool for the students to learn about how to express the subject content in a more developed and precise way, there was an integrated language and subject focus. The framing was fairly strong, and especially related to aspects of causality, since Karin had made it clear that students should use fixed expressions in their choice of sundials or clepsydras, and develop their arguments by explaining why the time measuring instrument was simple to use, for instance. She explicitly told the students to express the subject content in a certain way and valued their developed arguments. However, she never explicitly mentioned what lexicogrammatical resources students were to use to express the developed arguments, which made the framing weaker.

To summarize; there was an integrated language and subject focus during the ‘Recap activities’, and when the students were supposed to write developed arguments. Metalanguaging became a tool that made it possible for the students to learn about language, while learning the subject content through the language. Thus, it offered increased opportunities for the students’ language and content-integrated learning. The communication that took place in the ‘Recap activities’ had a stronger framing, where Karin to a greater extent controlled the interaction and what language students would use.

An isolated language focus

This section provides examples from three different types of PM-activities; ‘Planning and writing a recount about a school day without any clocks’, ‘Putting strips from a cut-up text in the right order’ and ‘Constructing sentences concerning the revolving of celestial bodies related to time, such as a day and night, a month and a year’, where an isolated language focus was identified.

At an early stage of the unit measuring time, Karin talked to her students about the imaginary consequences of not being able to measure time by using clocks in school. Inspired by genre pedagogy, the students were then supposed to plan and write a recount about a school day without any clocks. At the beginning of this PM activity, ‘Planning and writing a recount about a school day without any clocks’, she mentioned that the text structure consists of an orientation, events, an evaluation, and a re-orientation. She also said that the verb tense typical for the recount genre is the past tense and that ‘time-words’ (Swe. tidsord) are used to organize the text chronologically. Karin’s rather quick review revealed that she expected her students to be familiar with the text structure of a recount.

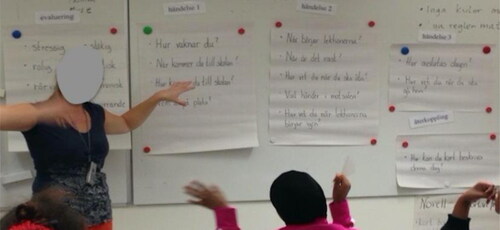

After she had presented her quick review, Karin showed the model plan that the students should follow when writing their recount. Karin read aloud (‘orientation’, ‘events one, two and three’, ‘evaluation’, ‘summary’), asked questions about what it said and gave many examples of so-called ‘support questions’. These support questions were on flipcharts () and were to be used to describe event one, event two, and event three.

As an example, Karin said: ‘And event one then, here we should ask ourselves, how do you wake up? How or when do you get to school? How do you get to school? Who is in the classroom when you get to school? Let’s concentrate on one event at a time, and then we make an evaluation of the event’. She then gave examples of ‘evaluating language’, which was also exemplified on a flipchart. The students were finally asked to plan their text with the help of the model plan. However, this was not easy. Many students had difficulty in understanding what they should write under the heading ‘orientation’, where it said ‘Who?, Where?, When?, What?, Why?’, as well as what to write under the headings of ‘evaluation’, ‘event’ and ‘summary’. The planning model’s use of the word ‘summary’ (Swe. sammanfattning), instead of ‘re-orientation’ (Swe. återkoppling), which Karin had used in her review of the task, made the model plan more difficult to use.

The learning in focus, when students were supposed to plan and write a recount, were primarily the names ‘orientation’, ‘event’, ‘evaluation’ and ‘summary’, but also how to use the model to plan and structure their recount. The metalanguaging was not directly linked to the scientific subject content; to understand the imaginary consequences of not being able to measure time by using clocks, which rather led students away from the subject content. Furthermore, the metalanguage did not seem to facilitate the students’ writing. Possibly, it would have been easier for the students to write the recount without the planning models’ form focus, not least considering that the recount is a fundamental/primary and common genre (Martin and Rose Citation2008). The PM activity primarily focused on how the model plan would be understood and used, and not on the subject content to be learned. The metalinguistic knowledge of how to write a recount was separated from the imaginary consequences of not being able to measure time with clocks. Since Karin explicitly instructed what language students should use to perform the activity, demanded that they use the model plan to perform the activity, and explained how she had assessed the text, the framing was strong. Nevertheless, her alternative support questions could be seen as a weakened framing, where it became more negotiable what the students should write about.

A few lessons later during the activity ‘Putting strips from a cut-up text in the right order’, the language also became its own learning object, isolated from the subject content to be learned. The students were instructed to put strips from a cut-up text in the right order. The complete text explained the historical development of the hourglass and had been cut up into ten strips. Since the students were not told the genre of the text, or how they should assemble the strips, they had difficulty knowing what to do. The students worked in pairs and were unaware of their teacher’s focus on form. This focus on form emerged as she moved around the classroom, helping students to put the strips in the correct order. The teacher said they should look at the tense of the process ‘to use’ to help them put the strips in order. During the activity, the teacher used a metalanguage that involved words like ‘processes’ (Swe. processer), ‘tense’ (Swe. tempus) and ‘present tense’ (Swe. nutid), which she expected the students to know.

To one pair, Ibrahim and Emre, Karin first said ‘Find the ones [the strips] with the process ‘is/are used’ and put them in the same paragraph’. The idea that students were supposed to distinguish the strips based on which tense the process ‘to use’ was in, emerged later, when the teacher pointed out that on some strips it said ‘is/are used’ and on other strips the tense was ‘has been used’. For Ibrahim, who also seemed to be unsure of how the present- and past tense are expressed, the activity was challenging (see Excerpt 3):

Excerpt 3

During this PM activity, Karin was following a plan that was logical to her, but that students had difficulty following. This was partly related to the vague answer Karin provided (i.e. turn 2, above), when the students asked her how the text strips should be arranged. It became particularly evident when she said to another pair of students, ‘And then you have to check if this is in a logical order’, whereupon one student replied ‘But we do not know the order. That’s what we don’t know’. The metalanguage that the teacher made explicit, when she moved around in the classroom talking to the students, potentially offered the students a learning opportunity for how a paragraph can be structured, by seeing if the sentences in the paragraph had the same tense of ‘to use’. Since the teacher’s focus on form did not give students increased opportunities to understand the historical development of an hourglass or how a typical scientific genre is structured, the activity probably did not improve the students’ understanding of the subject content.

Karin did not give instructions about what subject content students were supposed to learn nor what metalanguage they should focus on so as to perform the activity. When, in pairs, they asked for help, Karin explained her linguistic form focus. She confirmed that the students were supposed to put the strips together in the intended order, and that they themselves should explain why their order was correct. Thus, the framing was strengthened, since Karin controlled the students’ focus on the verb tenses and how the strips should be ordered, so as to produce a coherent paragraph.

In this activity, the metalanguage was isolated from the subject content, and was initially implicit, which probably explains the students’ expressed uncertainty. In addition, not all of the students seemed to be familiar with the metalanguage about ‘processes’, ‘tense’, and ‘present time’. When the learning objects were ambiguous, but combined with a strong framing, then the students struggled to understand how they were to perform the activity.

The two PM activities where an isolated language focus was identified were framed quite differently, not least concerning what language that was focused on and how explicitly this language was instructed. One main insight gained from the two ‘isolated activities’ mentioned above are that they seemed to leave some students confused. In the activity ‘Planning and writing a recount about a school day without any clocks’ the confusedness was likely to be related to students’ lack of knowledge of the words ‘orientation’, ‘event’, ‘evaluation’ and ‘summary’. In the activity ‘Putting strips from a cut-up text in the right order’ the confusedness was likely related to the implicit form focus and students lack of knowledge of how to talk about ‘processes’, ‘tense’, and ‘present time’. Another insight gained from the two isolated activities is that they added less to the students’ subject-specific language abilities, compared to the integrated activities. Neither ‘Planning and writing a recount of a school day without any clocks’ nor ‘Putting strips from a cut-up text in the right order’ were activities where students would use a subject-specific language, irrespective of how Karin motivated her planned linguistic activities during the interview. The metalanguage that the students were expected to use in the two PM activities focused on text structure, and were not related to the subject content. Thus, an isolated language focus can distract the students’ attention away from the subject content and even stand in the way of subject learning.

Finally, in this section, I will present an example of how an integrated language and subject focus becomes an isolated language focus, to some students. During one lesson, Karin taught her students about the rotation of the celestial bodies. At the end of the lesson, the students were instructed to ‘construct sentences concerning the revolving of celestial bodies related to time such as a day and night, a month and a year’ with the help of cut-up sentences, that had been written on sets of cards. The cards were coloured differently depending on whether they represented a process (green cards), a participant (red cards), or a circumstance (white cards). When Karin introduced the activity ‘Constructing sentences concerning the revolving of celestial bodies related to time, such as a day and night, a month and a year’, she made sure that her students knew the meaning of the words ‘participants’ and ‘processes’, which belong to SFL’s metalanguage. She also explained that ‘are’, ‘has’ and ‘is’ are common processes used to describe something (which earlier had been considered one of the most important genres in science education), that several of the cards would contain the process ‘is’, and that, by using the cards, students would describe what a day and night, a month and a year areFootnote3. As Karin focused on the linguistic meaning potentials that support particular subject learning there was an integrated language and subject focus.

Since the students in pairs were implicitly supposed to use SFL’s metalanguage to successfully perform the activity, some of them first expressed an uncertainty about what they should do with the cards. In one group, they discussed how day and night, month and year occur, after which they put the sentences together correctly. In another group, they quickly put together grammatically correct sentences, but with an incorrect subject content; ‘Day and night is the time it takes for the earth to spin around the sun’ and ‘Month is the time it takes for the earth to spin around its own axis’. The isolated language focus offered the students in this group the tools to formulate grammatically correct sentences, which may not have helped them to express or to understand the subject content. This example shows that teachers’ imagined integrated linguistic focus can lead to an isolated linguistic focus for the students.

Perhaps the gap between the teacher’s introduction of how lexicogrammar creates meaning to how students themselves would use this knowledge in the activity was too large. In addition, the example shows how student groups can interpret the teacher’s instructions quite differently. It is difficult to know how the teacher’s metalanguaging was received by the students. In the instruction Karin explicitly named the kind of language that was often used to describe something. However, she neither mentioned the language items that the students were supposed to use when they were to perform the activity, nor did she monitor the language that was used in the activity. Thus, the framing was weak; the students had the opportunity to negotiate how the activity was to be performed.

The communication of the metalanguage varied between the different PM activities described in this section, which likely can explain some of the students’ expressed uncertainty about how they were expected to perform the activities. The linguistic focus was sometimes related to linguistic concepts, while at other times to grammar, or genres. Furthermore, the linguistic focus was sometimes explicit, and at other times implicit. During the interview it was made clear that Karin positioned herself as a genre pedagogy educator. However, it sometimes seemed difficult for her to put the genre pedagogy into practice.

Discussion

Despite the importance of focusing on and using language while learning, little is known about how teachers in science instruction attend to these demands in linguistically diverse classrooms. This ethnographic case study contributes to this area of research interest with knowledge of how a teacher in science instruction used metalanguage in her PM activities to integrate a language focus in her linguistically diverse physics classrooms. The present study further makes a conceptual distinction that can be used to differentiate these PM activities from each other in terms of whether they integrate a language focus with, or isolate a language focus from, a science content focus.

Concerning which metalanguage was used in the PM activities, Karin focused on words as well as on text construction and how the subject content can be expressed in a more written-like, decontextualized and precise way (cf. Richardson Bruna, Vann, and Perales Escudero Citation2007, Citation2010; Seah Citation2016; Wilson and Jesson Citation2018). The PM activities focused the students’ literacy development, which is crucial for second language learners’ school success (de Oliveira and Schleppegrell Citation2015). Similar to the teachers in Seah and Yore’s study (Citation2017) and Seah and Silver’s study (Citation2018), Karin did not focus on basic literacy only, but also on disciplinary literacy. For instance, she explicitly stated that the two most important genres in science education are to describe and to explain, and she encouraged her students to use subject-specific words and generalizations. Karins’s subject-specific focus was also noticeable in the interview, where she claimed that her planned linguistic activities were intended to further develop the students’ subject-specific language.

With regard to how the communication of metalanguage related to subject-specific content and the learning opportunities revealed in these activities, the students in Karin’s classroom had frequent opportunities to attend to and use new forms of language, but the metalanguage in the PM activities was sometimes ambiguous and isolated from the subject content. The integrated linguistic focus enables increased subject learning, while the isolated linguistic focus can stand in the way of subject learning. If Karin had been clearer about how the students were expected to use the metalanguage, i.e. what they were expected to learn via the PM activities, then the uncertainty that was expressed by some of her students would probably have diminished. The fact that the communication of the metalanguage varied considerably between the different PM activities can also explain the students’ uncertainty about how they were expected to perform the activities. Creese (Citation2005) argues that teachers need to be explicit about what students are expected to learn during a certain activity, so that the linguistic focus of subject teaching does not become confusing for students. The present study seems so further support this claim.

In linguistically diverse classes, it is challenging to establish a level of instruction that suits most students. It is likely the case that Karin’s vagueness was connected to her expectations that the students were already familiar with the metalanguage used in the PM activities. In her quick briefings, the students were, for instance, expected to understand and be able to use a metalanguage to talk about the text structure of a recount, SFL’s processes and participants, and how text strips using the different verb tenses of the processes would be joined together. Possibly, the students did not have sufficient metalinguistic understanding to perform the activities in the manner the teacher expected them to. However, in the ‘Recap activities’, Karin supported the students as they moved forward in a more scientific discourse, by starting out from their expressed knowledge and language use (cf. Seah and Silver Citation2020). Thus, PM activities need to be tuned in to the students’ prior knowledge and language use.

Karins’ views and reasoning enhanced the credibility of the claims made from the lessons observed, because she reported that she carried out planned linguistic activities to further develop her students’ subject-specific language. Furthermore, many of the PM activities offered a text focus and that students would ‘put into words something substantial that they have been working on’, as mentioned by Karin in the interview. This approach also enabled Karin’s instruction to build on to the students’ expressed knowledge and language use (Seah and Silver Citation2020). The concept of framing (Bernstein Citation2000) deepened the analysis of how the communication of metalanguage varied between the PM activities. The concepts of an integrated language and subject focus (Uddling Citation2019, 19) and an isolated language focus, contribute with a metalanguage which can facilitate analysis of how teachers integrate a linguistic focus in their subject teaching, and what learning opportunities are revealed in their metalanguaging. Possibly, teachers themselves could use these concepts when planning metalanguage activities. When subject teachers plan what linguistic focus should be integrated into instruction, they need to ask what linguistic focus can contribute to increased learning and participation in subject teaching, so that language does not become its own learning object separated from subject learning.

Thus, the study has implications for how language can be integrated in subject teaching to offer increased opportunities for the students’ language and content-integrated learning; namely 1) when planning the metalanguage activities teachers need to ask what linguistic focus that can contribute to increased learning and participation in subject teaching 2) during the instruction the PM activities have to be attuned to students’ prior knowledge and language use, and 3) teachers need to be explicit about what students are expected to learn during a certain PM activity. In order to develop knowledge of how language can be integrated in subject teaching, teachers need to cooperate and learn from each other. This is since language teachers often lack knowledge of ‘content, discourse patterns, literate practices and habits of mind within specific disciplines’, and subject teachers (in subjects other than language) often lack ‘the necessary language awareness and literacy strategies to help students cope with the specific language and literacy demands of their discipline’ (Fang and Coatoam Citation2013, 629).

The present article has shown the complexity of teaching in ways that promotes learning of both subject matter and language in a linguistically diverse class. The present study has also shown how courageous teachers can be in trying out new strategies in order to develop students’ learning. Karin, primarily a mathematics and science teacher, constantly made efforts to explore how a linguistic focus might enhance her content-area teaching. The understanding of a teachers’ possibilities and challenges when integrating a linguistic focus into instruction can also be used in different supporting actions and to give better information about the design of interventions that seek to promote language and content-integrated learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest are reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Metalanguage is defined as talk about language (Berry Citation2010). This broad definition entails that I do not just focus on the meaning-based metalanguage grounded in SFL (like Schleppegrell Citation2013), but I also include instances when the teacher explained the meaning of words or employed an isolated form-focus, for example.

2 The textbook talks have already been analysed by Uddling (Citation2019).

3 See Jakobson and Axelsson (Citation2017) for a more detailed description of the same activity.

References

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Berry, R. 2010. Terminology in English Language Teaching: Nature and Use. Linguistic Insights. Studies in Language and Communication [Electronic Resource]. Bern: Peter Lang Publishing Group.

- Cheng, M. M. W., K. Danielsson, and A. M. Y. Lin. 2020. “Resolving Puzzling Phenomena by the Simple Particle Model: Examining Thematic Patterns of Multimodal Learning and Teaching.” Learning: Research and Practice 6 (1): 70–87.

- Christie, F. 2012. Language Education throughout the School Years: A Functional Perspective. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Creese, A. 2005. “Is This Content-Based Language Teaching?” Linguistics and Education 16 (2): 188–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2006.01.007.

- de Oliveira, L. C., and M. J. Schleppegrell. 2015. Focus on Grammar and Meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fang, Z., and S. Coatoam. 2013. “Disciplinary Literacy: What You Want to Know about It.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 56 (8): 627–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.190.

- Forey, G., and L. M. E. Cheung. 2019. “The Benefits of Explicit Teaching of Language for Curriculum Learning in the Physical Education Classroom.” English for Specific Purposes 54: 91–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.01.001.

- Halliday, M. A. K. 1993. “Towards a Language-Based Theory of Learning.” Linguistics and Education 5 (2): 93–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0898-5898(93)90026-7.

- Halliday, M. A. K., and J. R. Martin. 1993. Writing Science: Literacy and Discursive Power. London: Routledge.

- Howes, E. V., M. Lim, and J. Campos. 2009. “Journeys into Inquiry-Based Elementary Science: Literacy Practices, Questioning, and Empirical Study.” Science Education 93 (2): 189–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20297.

- Jakobson, B., and M. Axelsson. 2017. “Building a Web in Science Instruction: Using Multiple Resources in a Swedish Multilingual Middle School Class.” Language and Education 31 (6): 479–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1344701.

- Love, K., and A. Simpson. 2005. “Online Discussion in Schools: Towards a Pedagogical Framework.” International Journal of Educational Research 43 (7-8): 446–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.07.009.

- Martin, J. R., and D. Rose. 2008. Genre Relations: Mapping Culture. London: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

- Mortimer, E., and P. Scott. 2003. Meaning Making in Secondary Science Classrooms. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Richardson Bruna, K., R. Vann, and M. Perales Escudero. 2007. “What’s Language Got to Do with It?: A Case Study of Academic Language Instruction in a High School “English Learner Science” Class.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6 (1): 36–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2006.11.006.

- Richardson Bruna, K., R. Vann, and M. Perales Escudero. 2010. “You Got the Word Now: Problematizing Vocabulary-Based Academic Language Instruction for English Learners in Science.” Tapestry Journal 2 (1): 19–36.

- Schleppegrell, M. J. 2013. “The Role of Metalanguage in Supporting Academic Language Development.” Language Learning 63 (1): 153–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00742.x.

- Schleppegrell, M. J., and J. Moore. 2018. “Linguistic Tools for Supporting Emergent Critical Language Awareness in the Elementary School.” In Bilingual Learners and Social Equity. Critical Approaches to Systemic Functional Linguistics, edited by R. Harman, 23–43. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Seah, L. H. 2016. “Elementary Teachers’ Perception of Language Issues in Science Classrooms.” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 14 (6): 1059–1078. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9648-z.

- Seah, L. H., D. J. Clarke, and C. Hart. 2015. “Understanding Middle School Students’ Difficulties in Explaining Density Differences from a Language Perspective.” International Journal of Science Education 37 (14): 2386–2409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1080879.

- Seah, L. H., and R. E. Silver. 2020. “Attending to Science Language Demands in Multilingual Classrooms: A Case Study.” International Journal of Science Education 42 (14): 2453–2471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1504177.

- Seah, L. H., and L. D. Yore. 2017. “The Roles of Teachers’ Science Talk in Revealing Language Demands within Diverse Elementary School Classrooms: A Study of Teaching Heat and Temperature in Singapore.” International Journal of Science Education 39 (2): 135–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1270477.

- Seifeddine Ehdwall, D., and P.-O. Wickman. 2018. “Hur lärare kan stödja andraspråkselever på gymnasiet att tala kemi.” Nordic Studies in Science Education 14 (3): 299–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.5870.

- Shanahan, T., and C. Shanahan. 2008. “Teaching Disciplinary Literacy to Adolescents: Rethinking Content-Area Literacy.” Harvard Educational Review 78 (1): 40–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.v62444321p602101.

- Shanahan, C., and T. Shanahan. 2020. “Disciplinary Literacy.” In The SAT® Suite Classroom Practice: English Language Arts/Literacy, edited by J. Patterson, 91–125. New York: College Board.

- Tang, K.-S. 2016. “Constructing Scientific Explanations through Premise–Reasoning–Outcome (PRO): An Exploratory Study to Scaffold Students in Structuring Written Explanations.” International Journal of Science Education 38 (9): 1415–1440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1192309.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. 2019/2020. [Skolverket]. SIRIS data base, Skolverket, Stockholm.

- Uddling, J. 2019. “Textsamtalens möjligheter och begränsningar i språkligt heterogena fysikklassrum [Opportunities and Limitations of Text-Talks in Linguistically Diverse Physics Classrooms].” Doctoral diss., Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Weinburgh, M., C. Silva, K. H. Smith, J. Groulx, and J. Nettles. 2014. “The Intersection of Inquiry-Based Science and Language: Preparing Teachers for ELL Classrooms.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 25 (5): 519–541. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9389-9.

- Wilson, A., and R. Jesson. 2018. “A Case Study of Literacy Teaching in Six Middle- and High-School Science Classes in New Zealand.” In Global Developments in Literacy Research for Science Education, edited by K.-S. Tang and K. Danielsson, 133–147. Cham: Springer International Publishing.