Abstract

Curricular reform requires Finnish schools to be language aware and promote instruction that builds on students’ linguistic resources. However, knowledge about students’ experiences related thereto remains scarce. To create understanding about linguistic integration in increasingly multilingual schools, this study quantitatively explores the relationship between lower secondary school students’ (aged 13–16, N = 409) experiences and their linguistic backgrounds from three perspectives: (i) pedagogical practices, (ii) first language(s), and (iii) participating in academic-language situations. Theoretically, the study follows a sociocultural understanding of operationalising scaffolding within a learner’s zone of proximal development, valuing multilingualism as a resource, and identifying the demands of academic language. The data were collected at two multilingual schools via a survey. The findings reveal questions about the implementation of the language-aware curriculum requirement in schools. The experiences of students with diverse linguistic backgrounds differ, and thus, multilingual schools should pay specific attention to translating language awareness into pedagogical practices. The results further suggest that if activating learners via co-constructing, negotiating, and reformulating knowledge is helpful for emergent learners of Finnish, finding novel strategies to transform language and pedagogical understandings for sociocultural applications could help students overcome linguistic boundaries.

1. Introduction

To respond to increasing linguistic diversity, twenty-first century schools need to attend to language, learning, and learners simultaneously (Teemant Citation2018). Often, immigrant students are acquiring conversational proficiency in the language of the majority population while simultaneously participating in situations that require academic language (Cummins Citation2000; Schleppegrell Citation2004). These students come from various backgrounds and have a wide range of language proficiency levels (Majhanovich and Deyrich Citation2017); thus, an understanding of (second) language learning cannot be overlooked in schooling (Lucas and Villegas Citation2013). This study is positioned within the context of the reformed Finnish curricula’s promotion of language and culture awareness and multilingualism as a normative framework of basic education (Finnish National Agency for Education [EDUFI], Citation2014).

The term language awareness has been continuously redefined in educational linguistics and sociolinguistics (Komorowska Citation2014). From a holistic perspective, language awareness emphasises the extensive presence of language in education and the pedagogical practices that integrate students’ prior linguistic knowledge into all learning processes (ALA, Citation2021; Lilja, Luukka, and Latomaa Citation2017). For teachers, being language aware means planning instruction with consideration for the possible challenges language may present to students’ learning (Hélot Citation2017; Komorowska Citation2014). Language awareness provides a lens through which to examine the role and experience of language in multilingual schools; conceptually, it relates to multilingual language awareness (Candelier Citation2017) and critical multilingual language awareness (Garcia Citation2017). In language education, the fields of language awareness and multilingualism intertwine, with language awareness playing a role in the development of learners’ first language(s) (Finkbeiner and White Citation2017; Hélot Citation2017; Lehtonen Citation2021). The framework emerges as a foundation that, if translated into linguistically responsive pedagogical practices, could revolutionise schools (Cummins Citation2012; Lucas and Villegas Citation2013).

This study investigated the experiences of lower secondary school students (aged 13–16) who were different generations of Finnish learners. The goal of the study was to examine learners’ experiences in language-aware schools where instruction is supposed to be built on students’ multilingual resources. Drawing on a sociocultural premise, students’ experiences encompassed perspectives on pedagogical practices, first language(s), and participating in situations requiring the use of academic language. The study was built on the assumption that students’ perspectives on these three themes must be considered to advocate for language awareness in multilingual schools.

A deeper understanding of students’ experiences is important, as previous studies (Suuriniemi, Ahlhom, and Salonen Citation2021; Zilliacus, Paulsrud, and Holm Citation2017) have generated questions about how changed educational policies have been implemented in ways that help students achieve academic learning goals. Unfortunately, persistent inequalities in access to academic opportunities and resources have been documented in Finland (e.g. in PISA assessments) for immigrant-background students (Bernelius and Huilla Citation2021; Harju-Luukkainen et al. Citation2014; Zacheus, Kalalahti, and Varjo Citation2017). While research about teachers’ perspectives is available (Alisaari, Sissonen, and Heikkola Citation2021; Iversen Citation2021; Lundberg Citation2019), knowledge about students’ perspectives as language learners, language users, or participants in academic tasks remains scarce. Positioning students as knowledgeable in research allows for insights into their needs, experiences, and expertise related to multilingualism (Duarte Citation2019; Harju-Autti, Mäkinen, and Rättyä Citation2022; Lehtonen Citation2021; Seltzer Citation2019). When invited to discuss language, students have been willing and able to provide information on the importance of support when learning language and content (Harju-Autti, Mäkinen, and Rättyä Citation2022) and the benefits that fostering multilingualism brings to everyone in the classroom (Duarte, Citation2019; Lehtonen Citation2021; Seltzer Citation2019).

In a language- and culture-aware school system (EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education) Citation2014), all students are considered diverse (e.g. by gender, class, home, religion, sexuality, disability, physical appearance, and educational background), not only those with diverse linguistic and ethnic backgrounds (Zilliacus, Paulsrud, and Holm Citation2017). Students’ experiences echo the intersecting factors of their lives (Bradley Citation2016; Grzanka Citation2014). This study focussed on students’ linguistic backgrounds (see group definitions in Section 4), and quantitatively explored relationships between their experiences and backgrounds (RQ1). The aim was to advance the field of language awareness research by (i) demonstrating how pedagogical practices appear to learners, (ii) obtaining information on valuations that students give their first language(s), and (iii) providing insights into the demands of academic language. The analysis enhanced understanding of immigrant students’ linguistic integration (RQ2). The following research questions were addressed:

In what ways do the experiences of learners with diverse linguistic backgrounds differ with regard to i) pedagogical practices, ii) first language(s), and iii) participating in the language of schooling?

How do these aspects relate to one another within the language awareness framework?

2. Sociocultural understanding as a premise for applying pedagogical practices, valuing first language(s), and identifying the demands of academic language

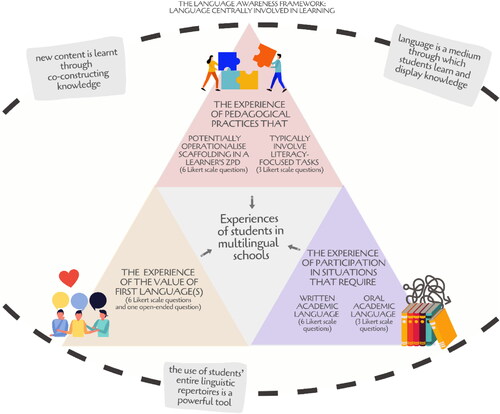

Following the understanding of (language) learning as an intrinsically social phenomenon (Lantolf and Thorne Citation2006; Vygotsky Citation1978), this study adopted the view that students in multilingual schools need specific types of language-related support and instruction that are built on their linguistic resources (Lucas and Villegas Citation2013). Language learning is supported in a student’s zone of proximal development (ZPD; Vygotsky Citation1978) when a more knowledgeable other (teacher, parent, or peer), through collaboration, helps them function beyond their current capabilities, which is known as scaffolding (Gibbons Citation2014; Vygotsky Citation1978). Through a sociocultural lens, language-aware schools recognise how central language is to mediating classroom interactions (Hélot Citation2017). Language use also shapes students’ cognition during classroom activities, which help students internalise content and perform at higher levels independently. Summarily, new content is learnt through co-constructing knowledge, ‘first as intermental, then intramental’ (Lantolf and Thorne Citation2006; Vygotsky Citation1978). The triangular theoretical framework around language awareness includes i) applying pedagogical practices that operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD (Lucas and Villegas Citation2013; Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014); ii) valuing learners’ first language(s) as a resource (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; García and Wei Citation2014); and iii) identifying the demands of academic language (Cummins Citation2000; Schleppegrell Citation2004).

2.1. Pedagogical practices

Traditionally, learning has been based on textual artefacts and literacy-focussed tasks (Barton Citation2007; in the Finnish context e.g. Luukka et al. Citation2008), and students often do individual ‘benchwork’. However, in classrooms where students work independently, the co-construction of knowledge does not emerge as intermental activity (Teemant Citation2018). Rethinking this (often teacher-led) classroom setting, this study draws on practices that have been argued (e.g. by Lucas and Villegas Citation2013; Teemant Citation2018; Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014) to operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD when learning academic content. These practices include extralinguistic supports (i.e. students’ entire linguistic repertoires, visuals, and hands-on activities); supports for written texts (i.e. study guides and opportunities to negotiate meaning orally); repetition in instruction; and clear and explicit instructions (Lucas and Villegas Citation2013; Verplaetse and Migliacci Citation2008). Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff (Citation2014) termed appropriate language-related and interactional practices standards of effective pedagogy, applying sociocultural understanding to teaching multilingual learners. These practices teach language, meaning, and academic content in joint productive activities, during which the teacher assists students to co-construct knowledge. The practices focus on increasing collaboration (teacher and a small group of students) and language production (teacher enacts instructional activities that generate the development of content vocabulary and assist literacy development through rephrasing and modelling). Practices also include contextualisation (teacher integrates activities with students’ prior knowledge to connect everyday and academic concepts) and challenging activities (activities that assist the development of complex thinking). Moreover, practices contain instructional conversation (teacher engages students through dialogue that has a clear academic goal and elicits discussion by questioning, listening, and responding) and a critical stance (teacher invites students to question conventional wisdom and seek to transform inequities through civic engagement; Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014, 138).

2.2. Valuing first language(s)

In language-aware schools, multilingual repertoires are deployed for social purposes (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015) and to create a foundation for efficiently operating within a student’s ZPD (Cummins Citation2000; García and Wei Citation2014). These can be implemented through translanguaging pedagogy, meaning the affordances that the use of students’ first language(s) can bring to enhance knowledge acquisition by enabling students to develop metacognitively, interact fluently and confidently, mediate understandings, and co-construct meaning (García and Kleifgen Citation2018). The flexible use of students’ linguistic repertoires allows them to, for instance, question, recap, reformulate, and elaborate on knowledge, which strengthens the quality of intermental activity (Duarte Citation2019) and provides students with access to classroom content and higher levels of participation. Furthermore, learning opportunities that draw on everyday life experiences, prior knowledge, and semiotic resources that are mediated by and include the use of first language(s) help learners develop stronger senses of identity and self. The purpose of translanguaging pedagogy is not only transitional; in addition to facilitating the learning of content and the language of the majority population, translanguaging serves as a powerful tool to destabilise oppressive language ideologies and support the development of first languages (Seltzer Citation2019). Indeed, normalising translanguaging pedagogies may reduce linguistic hierarchies (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; Nieto and Bode Citation2012). If multilingual classroom interactions are orchestrated in cognitively powerful and identity-affirming ways, they can reflect students’ experiences of the value of each other’s first language(s) (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; García and Kleifgen Citation2018; Lehtonen Citation2021). These experiences can demonstrate intrinsic (e.g. how proud I am of my first language[s]) or extrinsic (e.g. how much teachers or peers are interested in my first language[s]) aspects of value. When students see themselves (and know their teachers see them) as emergent multilinguals rather than as language learners (which defines students by what they lack), they are more likely to take pride in their linguistic proficiency (García and Kleifgen Citation2018).

2.3. Identifying the demands of academic language

Much research on language awareness discusses the linguistic features of disciplines and academic tasks (Candelier Citation2017; Finkbeiner and White Citation2017; Komorowska Citation2014). Often, academic language refers to the dimensions of language proficiency related to the language and literacy skills needed to participate in school situations (Cummins Citation2000; Schleppegrell Citation2004). Developing such proficiency is crucial for functioning in today’s text-based society (Haneda Citation2014), as language is the medium through which students learn and display knowledge (Cummins Citation2000; Schleppegrell Citation2004). Academic language differs fundamentally from conversational language (Cummins Citation2000; Gibbons Citation2014): different syntactic and semantic features, audiences, and registers of academic situations set cognitive demands higher than during informal oral situations wherein there is interactional co-construction of meaning (Schleppegrell Citation2004). For instance, situations requiring written academic language proficiency demand that students seek, analyse, and interpret information; understand and explain abstract concepts; and produce and edit written knowledge presentations (Lucas and Villegas Citation2013). Although oral academic situations exist, research on students’ language development focuses on the challenges of written academic language (Gumperz, Kaltman, and O’Connor Citation1984; Michaels and Collins Citation1984). Viewed through a sociocultural lens, language and thinking related to everyday and academic concepts develop simultaneously when participating in social situations with various registers and discourses (Vygotsky Citation1978). Thus, differing access to such situations before beginning school serves as preparation for the command of oral and written academic registers (Cummins Citation2000; Haneda Citation2014).

3. The context of the study: a language-aware school system

In Finland, the population growth is due to immigration; almost 8% of the 5.5 million Finnish citizens are speakers of languages other than Finnish, Swedish, or Sami (the three official languages of Finland; Statistics Finland, Citation2015/2021), particularly in disadvantaged neighbourhoods in big cities (Bernelius and Huilla Citation2021). Alarmingly, the process of developing teachers’ preparedness for linguistic integration has been slow (Repo Citation2020; Tarnanen and Palviainen Citation2018) and not self-evident (Alisaari et al. Citation2019; Suuriniemi, Ahlhom, and Salonen Citation2021).

Traditionally, Finnish and Swedish have been the languages of instruction in schools; officially, instruction can be in Sami, Romani, and Finnish Sign Language. However, societal changes due to the growing number of speakers of, for example, Russian and Estonian (languages that already have a long history in Finland) and Somali and Arabic (languages with a more recent presence) are challenging schools to become more inclusive. To emphasise schooling as a language-learning process, the Finnish national core curricula implemented ‘language awareness’ as a guideline for the development of school culture, stating that ‘each adult is a linguistic model’ (EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education) Citation2014, 26), and language development and the attainment of the literacy needed for successful academic participation are central to instruction. Schools are places where multiple languages interact, and students are encouraged to use the languages they know during lessons (EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education) Citation2014; Zilliacus, Paulsrud, and Holm Citation2017). Instruction that draws on students’ linguistic repertoires should recognise both indigenous languages and the languages of immigrant groups. Constitutionally, everyone has the right to maintain and develop their first language(s), and the municipalities are guided to offer first language lessons (as an extracurricular activity) (Piippo Citation2017).

4. Materials and methods

The data of this study are part of a larger survey investigating the experiences of students (n = 409) in linguistically diverse schools. The survey was used to study learners’ perspectives because of its anonymous nature, with the expectation of attaining a relatively large sample of honest perspectives (Field Citation2018; Tähtinen, Laakkonen, and Broberg Citation2020). Research on students’ experiences in multilingual schools has often been qualitative (Duarte Citation2019; Harju-Autti, Mäkinen, and Rättyä Citation2022; Lehtonen Citation2021; Seltzer Citation2019); thus, this study sought to explore how quantitative data would align therewith.

The terms used with regard to ‘multilingualism’, ‘immigration’, and ‘language proficiency’ did not come without consideration. Language proficiency is a multilingual and dynamic personal repertoire (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; Lantolf and Thorne Citation2006); therefore, the variable groups of the study are not fully unified in reality. Although adopting linguistic background as a variable enabled examination of groups’ characteristics, on the grassroots level, an individual student’s experiences cannot be explained this simply. Therefore, immigrant-background ‘multilingual Finnish language learners’ are referred to as MLLs (what some researchers call ‘language minoritised’ students; Flores and Rosa Citation2015). MLLs were further categorised as ‘emergent learners of Finnish’ (ELFs), meaning first-generation immigrant students (they and both parents were born somewhere other than Finland), and ‘more advanced learners of Finnish’ (ALFs), denoting second-generation immigrant students (they were born in Finland, but their parents were born elsewhere). All MLLs typically spoke languages other than that of the majority population as their first language(s). Recognising the problems of defining someone as ‘native’ (Eisenchlas and Schalley Citation2020; Leung, Harris, and Rampton Citation1997), ‘other learners of Finnish’ (OLFs) included learners of Finnish ‘origin’ and learners with more remote immigrant backgrounds. These learners were also multilingual and could communicate in different language contexts with their linguistic resources (Duarte and Gogolin Citation2013); the group included students with potentially more access to language proficiency, affiliation, and inheritance related to Finnish language and culture than MLLs (Leung, Harris, and Rampton Citation1997). The categorisation was also made for statistical reasons: the survey responses of students with more remote backgrounds aligned with the answers of students of Finnish ‘origin’ in ways that no statistically significant differences were found.

4.1. Data collection and instrument

The survey data were collected in 2017 at two multilingual lower secondary schools (grades 7–9) in Southern Finland. The participating schools were chosen due to the high immigrant concentration in the area (20–35%; Statistics Finland, Citation2015/2021). Throughout the data collection, it was acknowledged that some of the participants represented a vulnerable population. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent for the research was obtained at both the institutional and individual levels. Participants’ guardians gave permission to participate, and the participants could withdraw at any time. Participants’ privacy rights were respected by pseudonymisation of the data, and ethical regulations (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK) were followed. Before the data collection, a smaller group of student volunteers who were representative of the multilingual school population tested a pilot version of the survey and commented on its comprehensibility, length, and feasibility. These responses were examined to see whether the survey questions measured what they were meant to, after which a few sentences were reformulated.

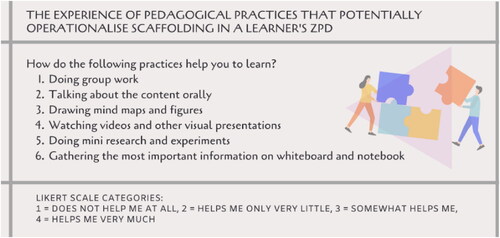

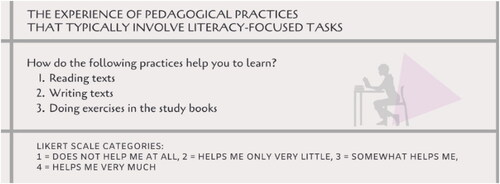

The survey instrument (Appendix) consisted of background information (e.g. linguistic background, gender, years in the school system, academic success, parents’ job situation, and students’ free-time activities) and a question section. The larger survey (which this study is part of) was developed in conjunction with the ‘Kielitietoisuus osaksi kaikkien aineiden opetusta [Language Awareness for Everyone]’ field project, in which the author was involved in advancing a linguistically responsive operating culture in targeted schools. The way of presenting the questions was inspired by previous research and assessment reports regarding MLLs’ learning outcomes in Finland (e.g. Harju-Luukkainen, Tarnanen, and Nissinen Citation2017; Kuukka & Metsämuuronen Citation2016; Pirinen Citation2015); however, as these reports focused on assessing educational success and language proficiency without focussing on the language awareness framework, new questions were designed for the specific purposes of this study. The survey was created to provide information about multilingual schools while resonating with Finland’s language-aware curricular reforms and echoing the sociocultural premise of (language) learning (Section 2). The questions covered the three angles of interest shown in . The experience of pedagogical practices consisted of two sub-themes: practices that potentially operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD, and practices that typically involve independent literacy-focussed tasks. The division into sub-themes was theory based, as intermental activity emerges in the course of co-constructing knowledge in one more than the other (Teemant Citation2018; Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014; Vygotsky Citation1978). Stemming from differing linguistic features and registers, the experience of participation in situations that require academic language was also divided into two sub-themes: oral and written situations (Cummins Citation2000; Schleppegrell Citation2004).

Data collection was conducted in Finnish; the survey was created with emerging language proficiency in mind. When formulating the questions, the experiences of teachers working with MLLs were considered to ensure that the questions were clear and accessible to the participants. Complex sentence structures and abstract idiomatic expressions were avoided. The teachers were also consulted on whether the questions were representative and relevant to the participants. The data were collected in mainstream classrooms to guarantee that the participating MLLs had lived at least one school year in Finland and would have the language proficiency to answer. Notably, the term ‘first language(s)’ instead of ‘home language’ was chosen to refer to the language(s) the students reported their parents speaking to them. In this way, the term did not limit the domain of the language to the speakers’ home; rather, it applied the idea of the language closest to a student’s identity (Seltzer Citation2019). Indeed, an MLL’s ‘first language’ may consist of a multilingual repertoire of distinct languages (Duarte and Gogolin Citation2013); thus, this angle of interest was approached using open-ended questions (Section 4.3) to avoid binary categories arising from a monolingual norm.

4.2. Participants

Of the 409 students who completed the survey, 73.8% (n = 302) were OLFs, 12.2% (n = 50) were ALFs, and 13.9% (n = 57) were ELFs, reflecting a typical multilingual school population in Finland. These groups were used as classes of categorical independent variables in the analysis, recognising their inner heterogeneity (e.g. MLLs had 46 different countries of origin) and linguistic proficiencies. According to the students’ reports, multilingualism is a part of everyday life, as seen in the following example: an emergent learner of Finnish from Rwanda speaks Finnish and Kinyarwanda to both of her parents. Both parents speak Kinyarwanda to her. With her friends and in hobbies, she speaks Finnish and English. She likes speaking English the most.

As could be interpreted from the participants’ background information (), the students’ experiences in multilingual schools were influenced by multiple overlapping and intersecting factors (e.g. gender, years in the school system, and academic success; Bradley Citation2016; Grzanka Citation2014). However, we chose to focus on students’ linguistic backgrounds because the groups differed from one another when described quantitatively.

Table 1. Participants.

The participants’ academic success was similar to the results of international assessments (Harju-Luukkainen et al. Citation2014; Zacheus, Kalalahti, and Varjo Citation2017), demonstrating that the schools chosen for the study were representative of typical multilingual schools in Finland. The differences in academic success between OLFs and MLLs were statistically significant (see ‘Average grade’ in ; F(2, 387) = 17.62, p < 0.001, ω2 = 0.079). With regard to repeating a school year, statistically significant differences (p = 0.006, Fisher’s exact test) between OLFs and ALFs versus ELFs align with previous research (Kirjavainen and Pulkkinen Citation2015).

Grounding in intersectionality, reported background information on parents’ employment and students’ free time activities could be a description of social class, and, in accordance with language learning theories (Haneda Citation2014; Vygotsky Citation1978), students’ access to societal situations and social interactions in Finnish. However, the participants’ families seem to have had varying opportunities to participate in informal and academic social interactions through work or organised free-time activities. First, 91.4% of the OLFs’ mothers had a job, compared to 49.1% of the ELFs and 50.0% of the ALFs (χ2= 87.99, df = 2; p < 0.001, Cramér’s V = 0.46), indicating an association between participants’ linguistic backgrounds and their mothers’ employment status. Similarly, 87.7% of the OLFs’ fathers had a job, compared to 70.2% of the ELFs and 80.0% of the ALFs (χ2 = 12.04, df = 2, p = 0.002, Cramér’s V = 0.17). Second, according to answers to the open-ended question ‘What do you typically do after school?’, 57.9% of the OLFs participated in an organised free time activity, compared to 24.6% of the ELFs and 34.0% of the ALFs (χ2= 27.48, df = 2, p < 0.001, Cramér’s V = 0.26).

4.3. Data analysis

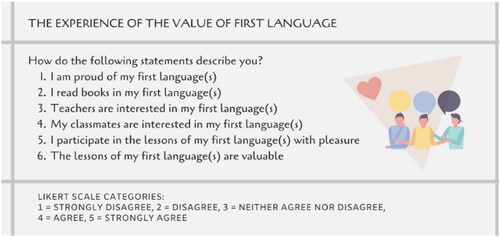

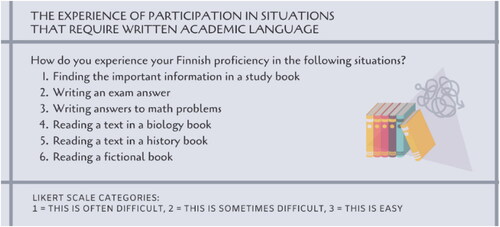

The data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS version 27. Students’ experiences of pedagogical practices, value of first language(s), and participating in academic situations were measured using 24 Likert scale questions and one open-ended question. Drawing on the theoretical framework, the Likert scale questions were used to construct summed variables () based on the statistical analysis of inter-item correlation and the content. In total, there were three summed-variable themes (1–3) corresponding to the three angles of interest; as mentioned, the first and third were divided into two sub-themes each (1a and 1b, 3a and 3b). The second variable was followed by an open-ended question on the use and valuation of participants’ language(s). The reliability of the summed variables was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. Overall, the reliability was good, suggesting high internal consistency between the items (the items of each summed variable are introduced in Sections 5.1–5.3). The lowest reliability was observed in the experience of the value of first language(s) (α = 0.63), but this was accepted as an adequate reliability value (α > 0.70). The construction of the variables considered the sociocultural understanding of pedagogical practices, valuing first language(s), and identifying demands academic language; the construction was supported by the fact that Cronbach’s alpha was weakened if the variables were constructed differently.

Table 2. Summed variables.

The first summed variable theme, The experience of pedagogical practices, comprised questions about how helpful (in terms of learning) the students found practices that have been argued (Lucas and Villegas Citation2013; Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014) to offer temporary support to provide learners with access to the content being taught (1a). To enable comparison, a similar variable was formed by measuring experiences of practices that are typically based on textual artefacts (1b; the variables being ‘compared’ contained fewer items). The second theme, The experience of the value of first language(s), included items measuring valuations that students gave their first language(s) (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; García and Wei Citation2014). The third theme, The experience of participation in situations that require academic language, contained estimations about participants’ Finnish proficiency in accordance with various academic classroom tasks (Cummins Citation2000; Schleppegrell Citation2004) and included summed variables of situations with registers of schooling in oral (3a) and written (3b) modes.

In the analysis, the summed variables were employed as response variables to analyse how students’ linguistic backgrounds related thereto. This was done using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc tests (Hochberg’s GT2) when appropriate. In cases where the data violated the assumption of homogeneity of variances, Welch’s test was used instead of ANOVA (with consideration for the different group sizes), followed by post hoc tests (Games-Howell). The effect size was measured using the Omega squared (ω2) value.

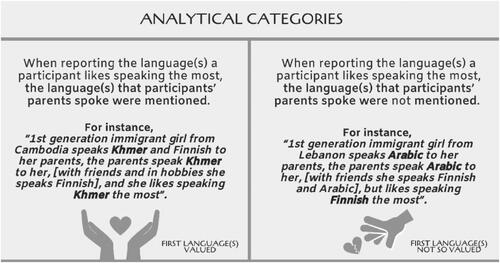

Regarding the experience of the value of first language(s), the study included an open-ended question asking participants the following: what language(s) a) they speak to their mother, b) their mother speaks to them, c) they speak to their father, d) their father speaks to them, e) they speak with their friends, f) they speak in hobbies, and g) they like speaking the most. To focus on first language(s), questions a)–d) and g) were analysed to ascertain whether the students mentioned the language(s) that their parents spoke to them among the language(s) they liked speaking the most. The reports were classified according to the two categories seen in .

After classifying the data, statistical analysis was conducted using t-tests, and, in cases where both variables were categorical, cross-tabulations. The effect size for the t-tests was measured using Cohen’s d value. The association between two categorical variables was observed from Cramer’s V value.

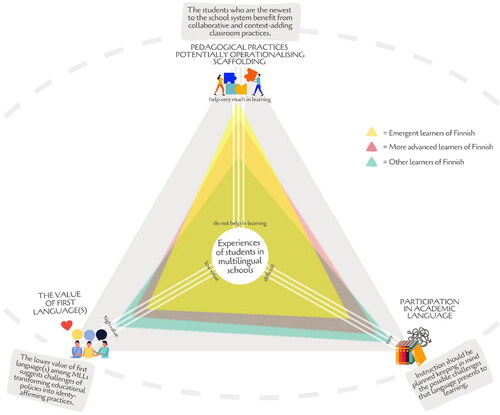

5. Results and discussion: being a learner in the language-aware Finnish school system

From an intersectional view, no single factor can unambiguously explain students’ learning outcomes or experiences (Ahonen Citation2021; Ansala, Hämäläinen, and Sarvimäki Citation2020); however, overlapping factors that influence students’ schooling were identified. Although several statistically significant differences were observed between the three participant groups, the measured effect size (ω2) sometimes suggested small to moderate practical significance. However, as the participants had varying access to educational resources and Finnish language expertise (indicated by background information), the analysis sheds light on certain characteristics of linguistic integration. presents the findings, which will be discussed in more detail in Sections 5.1–5.3.

Table 3. Findings.

5.1. The experience of pedagogical practices

As can be seen in (Section 4.3), the students experienced the practices that operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD when learning academic subject content (M = 2.82, SD = 0.65) and the practices that typically involve literacy-focussed tasks (M = 2.90, SD = 0.69) as almost equally helpful (the higher the mean on a scale of 1–4, the more helpful the practices in terms of learning). Analysing relationships to participants’ linguistic backgrounds, however, elucidated what to consider when designing instruction for new arrivals in the school system. The summed variable the experience of pedagogical practices that potentially operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD comprised six items ().

There were significant differences in the students’ experiences. According to a post hoc test (Hochberg), ELFs experienced the practices that operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD as more helpful than OLFs did. No difference in the reports of the ALFs was found. Clearly, OLFs have an advantage in learning academic content, concepts, and registers, as they do so through the medium of their first language(s) (Gibbons Citation2014; Schleppegrell Citation2004). The ELFs’ reports can be understood via the Vygotsky (Citation1978) premise that language learners are active in co-constructing, reformulating, and innovating. In practices such as ‘doing group work’, ‘talking about the content orally’, and ‘doing mini research and experiments’, interaction comprises the learning process, and language serves as the means for mediation in the ZPD, guiding the internalisation of the content from a social to an individual level (Vygotsky Citation1978). Here, intermental activities (e.g. explanation, disagreement, and mutual regulation) trigger extra cognitive mechanisms (e.g. knowledge, elicitation, and reduced cognitive load). Potentially, the practices with extralinguistic supports enhance linguistic integration, as the use of academic language becomes modelled and reinforced from multiple directions during interaction (Teemant Citation2018). This finding indicates that when classrooms have multiple small-group activities during which students negotiate meaning and integrate content with their prior knowledge, linguistically diverse students find instruction more helpful.

The summed variable the experience of pedagogical practices that typically involve literacy-focussed tasks contained three items (). These practices, which are often teacher-led, are traditional in Finnish schools (Luukka et al. Citation2008).

Interestingly, there were no statistically significant differences in students’ experiences regarding how helpful the practices involving literacy-focussed tasks were. However, both OLFs and ALFs found these practices more helpful than those that operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD. From the perspective of linguistic integration, this may be because the school context has socialised students with more years in the system to appreciate literacy and texts in written modes (Schleppegrell Citation2004).

5.2. The experience of the value of first language(s)

The summed variable the experience of the value of first language(s) included six items (). The items covered both intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of value.

The statistical analysis suggested a significant difference in students’ experiences of the value of their first language(s). A post hoc test (Games-Howell) indicated that ELFs gave their first language(s) less value than OLFs; again, neither group differed statistically from the ALFs. When critically interpreting the findings from a sociolinguistic perspective, the prestige and power associated with the first language(s) of OLFs must be recognised (Cummins Citation2000; Nieto and Bode Citation2012). Finnish is the language of the majority population for these students; thus, it might be easier for OLFs to, for instance, find suitable readings in Finnish or consider participation in the lessons pleasurable. However, the normative framework for basic education (EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education) Citation2014) explicitly fosters multilingualism across curricula. The lower value of first language(s) among MLLs highlights the challenges of transforming educational policies into identity-affirming practices (Zilliacus, Paulsrud, and Holm Citation2017). This finding resonates with research documenting teachers’ difficulties with embracing multilingual discourses (Repo Citation2020; Tarnanen and Palviainen Citation2018). From the perspective of mediation within a ZPD, seeing first language(s) as a resource plays an important role in language-aware schools: employing entire multilingual repertoires allows for wider intermental activity when students mutually scaffold one another, for example, by translanguaging (Duarte Citation2019; García and Wei Citation2014).

Analysis of the open-ended question regarding the language(s) the participants’ parents spoke compared to the language(s) the participants liked speaking the most enabled methodological triangulation. Overall, 14.7% of the participants liked speaking language(s) other than what their parents spoke to them the most. When looking at relationships with participants’ backgrounds, 50.9% of the ELFs and 32.0% of the ALFs did not mention their first language(s) among the languages they liked speaking the most (the corresponding percentage for OLFs was 5.0%; χ2 = 94.41; df = 2; p < 0.001; Cramér’s V = 0.48). With regard to linguistic integration, the ELFs’ reports potentially reflect an eagerness to participate actively in Finnish in linguistic and cultural settings, such as school, free time activities, peer group interaction, or even family life. Arguably, this finding reiterates the importance of access to social interactions when learning a new language (Lantolf and Thorne Citation2006). However, if half of the students experienced their first language(s) as ‘less usable or likeable’ than the language of the majority population a few years after entering the school system, this might, at worst, demonstrate persistent societal language hierarchies that render MLLs’ languages invisible, or a school’s lack of commitment to shifting away from monolingual ideologies (Alisaari et al. Citation2019; Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; Tarnanen and Palviainen Citation2018).

As expected, the participants who mentioned their first language(s) among the languages they liked speaking the most generally experienced the value of their first language(s) as higher (M = 3.55, SD = 0.76) than those who preferred speaking other language(s) (M = 3.02, SD = 0.78; t(407) = 4.94, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.68). Although causality cannot be inferred from the analysis, developing grassroots practices that stem from viewing linguistically diverse learners as emergent multilinguals could help MLLs take pride in their first language(s). Indeed, if the potential of translanguaging pedagogy overcame the many restrictions that societal institutions and cultural practices impose on the side-by-side use of different languages, the use of students’ first language(s) in meaning-making would be established as of equal value and a norm in academic contexts (García and Kleifgen Citation2018).

5.3. The experience of participation in situations that require academic language

The summed variables regarding the experience of participation in situations that require academic language contained items characteristic of classroom tasks. As seen in (Section 4.3), according to all participants, participation in both oral (M = 2.88, SD = 0.37) and written (M = 2.84, SD = 0.39) academic situations was experienced as similar (the higher the mean on a scale of 1–3, the easier it was experienced to have sufficient language proficiency for the situation). However, Welch’s test indicated that academic registers, especially in a written mode, were more difficult for ELFs. Viewed through a sociocultural lens, this is not surprising. In situations where a student, for instance, independently reads a text or writes an exam answer, there is potentially less mediation in their ZPD than in oral situations with more opportunities for intermental activity (Vygotsky Citation1978).

The summed variable the experience of participation in situations that require oral academic language comprised three situations, as shown in .

Once again, there were statistically significant differences in the experiences of students with different backgrounds. A post hoc test (Games-Howell) suggested that ELFs experienced oral academic situations as more difficult than OLFs. There was no significant difference in the ALFs’ experiences.

The summed variable the experience of participation in situations that require written academic language included six situations ().

Statistical analysis again demonstrated significant differences between the participants’ experiences. This time, a post hoc test (Games-Howell) showed that ELFs experienced participating in written situations as more difficult than OLFs and ALFs. Notably, compared to situations using academic language orally, the only ‘drop’ (when observing the mean) occurred in the ELFs’ experiences. In any case, in Finnish mainstream classrooms, there are newcomers who find participating in academic situations at least ‘sometimes difficult’ linguistically, creating an interesting contrast with teachers’ tendencies to overestimate students’ linguistic competences (Suni and Latomaa Citation2012). This finding echoes a report on the objectives of Finnish-as-a-second-language teaching (Kuukka & Metsämuuronen 2016) that proposes that the lowest language proficiency levels (level A in the Common European Framework of Reference) are best explained by a low number of years in the school system. Moreover, ELFs’ experiences can be tied to Cummins (Citation2000) observation of the characteristics of language proficiency development: while a newcomer is likely to develop conversational language in one to two years, it may take up to seven years to develop the registers of written academic language to a level equivalent to a more advanced speaker of the same age.

6. Conclusions

‘If the school system wants learners to emerge from schooling after basic education as intelligent, imaginative, and linguistically talented, the system must treat them as intelligent, imaginative, and linguistically talented from the first day they arrive in school’ (foreword by Cummins, in Gibbons Citation2014). With diverse student populations increasing internationally, school systems everywhere are being challenged to increase the achievement and integration of linguistically diverse students (Teemant Citation2018; Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014). The implementation of language awareness in schools has become an inextricable part of educational discussions in Finland (Aalto Citation2019; Ahlholm, Piippo, and Portaankorva-Koivisto Citation2021; Rapatti Citation2020). This study traced the experiences of different students (ELFs, ALFs, and OLFs) in multilingual lower secondary schools related to the language awareness framework from the perspectives of pedagogical practices, first language(s), and utilising academic language at a time of changing demographics and educational policies. The findings indicate that, because the experiences of students with diverse linguistic backgrounds in multilingual schools differ, language-aware schools should pay specific attention to these themes. Statistical analysis of the students’ responses suggested that the ELFs’ experiences differed significantly from the OLFs’ (interpretation of the conclusions presented in [not to scale]). For the ELFs, participation in academic situations proved more challenging, and practices that potentially operationalise scaffolding in a learner’s ZPD were more helpful (for similar findings, see Harju-Autti, Mäkinen, and Rättyä Citation2022). In addition, the ELFs gave their first language(s) lower values, and many preferred to speak Finnish instead of the language(s) their parents spoke.

With such a non-recurrent, pre-controlled setting, it was only possible to collect experiences related to the questions designed by the researcher. The explored reports are experiential testimonies of students about their situations; in reality, academic activities may involve different language-related challenges (Li and Zhang Citation2020). Nevertheless, the lower value that the ELFs gave their first language(s) leads to questions about the implementation of the language-aware curricula requirement that different languages interact in schools (EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education) Citation2014). The results further suggest that the students who are the newest to the school system benefit from collaborative and context-adding classroom practices; if activating learners via co-constructing, negotiating, and reformulating knowledge is helpful for MLLs, finding novel strategies to transform language and pedagogical understandings for sociocultural applications could help students overcome linguistic boundaries (García and Wei Citation2014; Lehtonen Citation2021). For instance, responding to linguistic diversity using standards-effective pedagogy (Teemant, Leland, and Berghoff Citation2014) might offer teachers concrete examples of scaffolding.

The significance of this study lies in its effort to capture ‘snapshots’ of students’ experiences related to schools’ ever shifting and evolving language policies (Shohamy Citation2006; Spolsky Citation2004). The ALFs’ experiences were positioned between the ELFs’ and OLFs’, perhaps because their language repertoires have been integrating into the academic communication environment longer. The cross-sectional comparison of different generations of Finnish learners shows how supporting MLLs’ linguistic integration through scaffolding, valuing first language(s), and identifying the demands of academic language cannot be considered ‘either-or’ matters. In this study, ELFs recognised the supports as helpful in terms of learning, indicating that measures of linguistic integration are at least empirically appropriate. However, if the language demands of academic tasks are not identified from learners’ perspectives and instruction does not attend to language, MLLs’ attitudes may be blamed for their learning outcomes (Pettit Citation2011; Repo Citation2020) in socio-political discussions, thereby (unfortunately) perpetuating xenophobic and racist discourses. The development of a school system that promotes equal access to learning opportunities has several intersecting dimensions (Bradley Citation2016; Grzanka Citation2014), one of which is linguistic background. Combining this with other dimensions for creating pedagogical practices and forthcoming research plans will be an important next step. For instance, qualitative approaches to multilingual scaffolding strategies in classroom contexts would provide relevant information on underlying language hierarchies. In sum, future educational policy decisions cannot be made without an awareness of language and consideration for different generations of language learners.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the study participants for their time and effort, and to statistician Eero Laakkonen for SPSS consulting. I thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Aalto, E. 2019. Pre-Service Subject Teachers Constructing Pedagogical Language Knowledge in Collaboration. Jyväskylän yliopisto. JYU Dissertations, 158.

- Ahlholm, M., I. Piippo, and P. Portaankorva-Koivisto. 2021. “Koulun Monet Kielet. Plurilingualism in the School.” AFinLA-e.Soveltavan Kielitieteen Tutkimuksia 2021 (13), 4–20.

- Ahonen, A. 2021. “Finland : Success through Equity: The Trajectories in PISA Performance.” In Improving a Country’s Education: PISA 2018 Results in 10 Countries, edited by N. Crato, 121–136. Berlin: Springer.

- ALA (Association for Language Awareness). 2020. Association for Language Awareness. www.languageawareness.org.

- Alisaari, J., L.-M. Heikkola, N. Commins, and E. Acquah. 2019. “Monolingual Practices Confronting Multilingual Realities. Finnish Teachers’ Perceptions of Linguistic Diversity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 80: 48–58. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003.

- Alisaari, J., S. Sissonen, and L.-M. Heikkola. 2021. “Teachers’ Beliefs Related to Language Choice in Immigrant Students’ Homes.” Teaching and Teacher Education 103: 103347. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103347.

- Ansala, L., U. Hämäläinen, and M. Sarvimäki. 2020. “Age at Arrival, Parents and Neighborhoods: understanding the Educational Attainment of Immigrants’ Children.” Journal of Economic Geography 20: 459–480.

- Barton, D. 2007. Literacy. An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bernelius, V., and H. Huilla. 2021. “Koulutuksellinen Tasa-Arvo, Alueellinen ja Sosiaalinen Eriytyminen ja Myönteisen Erityiskohtelun Mahdollisuudet.” Valtioneuvoston Julkaisuja 2021: 7. Valtioneuvosto. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-383-761-4

- Bradley, H. 2016. Fractured Identities: Changing Patterns of Inequalities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Candelier, M. 2017. “Awakening to Languages” and Educational Language Policy.” In Language Awareness and Multilingualism. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, edited by J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, and S. May, 161–172. Berlin: Springer.

- Cummins, J. 2000. Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins, J. 2012. “Language Awareness and Academic Achievement among Migrant Students.” In Éveil Aux Langues et Approches Plurielles. De la Formation Des Enseignants Aux Pratiques de Classe, edited by C. Balsiger, D. Bétrix Köhler, J.-F. de Pietro, and C. Perregaux, 41–56. Paris: l’ Harmattan.

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2015. “Translanguaging and Identity in Educational Settings.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35: 20–35. doi:10.1017/S0267190514000233.

- Duarte, J. 2019. “Translanguaging in mainstream education: a sociocultural approach.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (2): 150–164. doi:10.1080/13670050.2016.1231774.

- Duarte, J., and I. Gogolin. 2013. “Superdiversity in Educational Institutions.” In Linguistic Super-Diversity in Urban Areas: Research Approaches, J. Duarte and I. Gogolin, 1–24. Hamburg Studies on Linguistic Diversity. John Benjamins Publishers.

- EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education). 2014. National core curriculum for basic education.

- Eisenchlas, S., and A. Schalley. 2020. “Making Sense of “Home Language” and Related Concepts.” In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development, edited by S. Eisenchlas and A. Schalley, 17–37. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Field, A. 2018. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London, England: Sage.

- Finkbeiner, C., and J. White. 2017. “Language Awareness and Multilingualism: A Historical Overview.” In Language Awareness and Multilingualism. Encyclopedia of Language and Education. 3rd ed. edited by J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, and S. May, 3–17. Cham: Springer.

- Flores, N., and J. Rosa. 2015. “Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education.” Harvard Educational Review 85 (2): 149–171. doi:10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149.

- Garcia, O. 2017. “Critical Multilingual Awareness Raising and Teacher Education.” In Language Awareness and Multilingualism. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, edited by J. Cenoz, D. Gorter, and S. May, 263–280. Berlin: Springer.

- García, O., and J. Kleifgen. 2018. Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs and Practices for English Learners. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- García, O., and L. Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gibbons, P. 2014. Scaffolding Language. Scaffolding Learning. Teaching Second Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Heinemann: Portsmouth.

- Grzanka, P. 2014. Intersectionality. A Foundations and Frontiers Reader. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Gumperz, J., H. Kaltman, and M. O’Connor. 1984. “Cohesion in Spoken and Written Discourse: Ethnic Style and the Transition to Literacy.” In Coherence in Spoken and Written Discourse, edited by D. Tannen, 3–19. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Haneda, M. 2014. “From Academic Language to Academic Communication: Building on English Learners’ Resources.” Linguistics and Education 26: 126–135. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.004.

- Harju-Autti, R., M. Mäkinen, and K. Rättyä. 2022. “‘Things Should Be Explained so That the Students Understand Them’: Adolescent Immigrant Students’ Perspectives on Learning the Language of Schooling in Finland.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25 (8): 2949–2961. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1995696

- Harju-Luukkainen, H., K. Nissinen, S. Sulkunen, M. Suni, and J. Vettenranta. 2014. Avaimet Osaamisen Tulevaisuuteen. Selvitys Maahanmuuttajataustaisten Nuorten Osaamisesta ja Siihen Liittyvistä Taustatekijöistä PISA 2012-Tutkimuksessa. Finland: Finnish Institute for Educational Research, University of Jyväskylä.

- Harju-Luukkainen, H., M. Tarnanen, and K. Nissinen. (Red.) 2017. “Monikieliset Oppilaat Koulussa: eri Kieliryhmien Sisäinen ja Ulkoinen Motivaatio ja Sen Yhteys Matematiikan Osaamiseen PISA 2012 -Arvioinnissa.” In Kielitaidon Arviointitutkimus 2000-Luvun Suomessa, edited by A. Huhta and R. Hildén, 167–183. Soveltavan kielitieteen tutkimuksia, 2016:9. Jyväskylä, Finland: Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistys AFinLA ry.

- Hélot, C. 2017. “Awareness Raising and Multilingualism in Primary Education.” In Language Awareness and Multilingualism. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, edited by J. Cenoz, D. Gorter and S. May, 247–261. Berlin: Springer.

- Iversen, J. 2021. “Negotiating Language Ideologies: Pre-Service Teachers’ Perspectives on Multilingual Practices in Mainstream Education.” International Journal of Multilingualism 18 (3): 421–434. doi:10.1080/14790718.2019.1612903.

- Kirjavainen, T., and J. Pulkkinen. 2015. Maahanmuuttajaoppilaat ja Perusopetuksen Tuloksellisuus. Tuloksellisuustarkastuskertomus 12:2015. Helsinki: Valtiontalouden tarkastusvirasto.

- Komorowska, H. 2014. “Language Awareness: From Embarras de Richesses to Terminological Confusion.” In Awareness in Action, edited by A. Lyda and K. Szcześniak, 3–20. Cham: Springer.

- Kuukka, K., and J. Metsämuuronen. 2016. Perusopetuksen PääTtöVaiheen Suomi Toisena Kielenä (S2) -OppimääRän Oppimistulosten Arviointi 2015. Julkaisut 13:2016. Helsinki: Karvi.

- Lantolf, J., and S. Thorne. 2006. Sociocultural Theory and the Genesis of Second Language Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lehtonen, H. 2021. “Kielitaitojen Kirjo Käyttöön, Limittäiskieleilyä Luokkaan.” In Koulun Monet Kielet. Plurilingualism in the School, edited by M. Ahlholm, I. Piippo, and P. Portaankorva-Koivisto, Vol. 13, 70–90. Jyväskylä: Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistyksen julkaisuja. doi:10.30660/afinla.100292.

- Leung, C., R. Harris, and B. Rampton. 1997. “The Idealised Native Speaker, Reified Ethnicities, and Classroom Realities.” TESOL Quarterly 31 (3): 543–560. doi:10.2307/3587837.

- Li, M., and X. Zhang. 2020. “A Meta-Analysis of Self-Assessment and Language Performance in Language Testing and Assessment.” Language Testing 38: 189–218.

- Lilja, N., E. Luukka, and S. Latomaa. 2017. “Kielitietoisuus Eriarvoistumiskehitystä Juurruttamassa.” In Kielitietoisuus Eriarvoistuvassa Yhteiskunnassa, edited by S. Latomaa, E. Luukka, and N. Lilja, 11–29. AFinLAn vuosikirja 2017. Jyväskylä: Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistyksen julkaisuja 75.

- Lucas, T., and A.-M. Villegas. 2013. “Preparing Linguistically Responsive Teachers: Laying the Foundation in Preservice Teacher Education.” Theory into Practice 52 (2): 98–109. doi:10.1080/00405841.2013.770327.

- Lundberg, A. 2019. “Teachers’ Viewpoints about an Educational Reform concerning Multilingualism in German-Speaking Switzerland.” Learning and Instruction 64: 101244–101248. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244.

- Luukka, M.-R., S. Pöyhönen, A. Huhta, P. Taalas, M. Tarnanen, and A. Keränen. 2008. Maailma Muuttuu - Mitä Tekee Koulu? Äidinkielen ja Vieraiden Kielten Tekstikäytänteet Koulussa ja Vapaa-Ajalla. Finland: Jyväskylän yliopisto, Soveltavan kielentutkimuksen keskus.

- Majhanovich, S., and M.-C. Deyrich. 2017. “Language Learning to Support Active Social Inclusion: Issues and Challenges for Lifelong Learning.” International Review of Education 63 (4): 435–452. doi:10.1007/s11159-017-9656-z.

- Michaels, S., and J. Collins. 1984. “Oral Discourse Styles: Classroom Interaction and the Acquisition of Literacy.” In Coherence in Spoken and Written Discourse, edited by D. Tannen, 219–244. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Nieto, S., and P. Bode. 2012. Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Pettit, S. 2011. “Teachers’ Beliefs about English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom: A Review of the Literature.” International Multilingual Research Journal 5 (2): 123–147. doi:10.1080/19313152.2011.594357.

- Piippo, J. 2017. “Näkökulmia oman Äidinkielen Opetukseen: kuntien Kirjavat Käytänteet.” Kieli, Koulutus ja Yhteiskunta, 8(2). Saatavilla. https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-jayhteiskunta-huhtikuu-2017/nakokulmia-oman-aidinkielen-opetukseen-kuntien-kirjavat-kaytanteet

- Pirinen, T. 2015. Maahanmuuttajataustaiset Oppilaat Suomalaisessa Koulutusjärjestelmässä. Koulutuksen Saavutettavuuden ja Opiskelun Aikaisen Tuen Arviointi. Tampere: Kansallisen koulutuksen arviointikeskus.

- Rapatti, K. 2020. Kaikkien Koulu(Ksi) – Kielitietoisuus Koulun Kehittämisen Kulmakivenä. Helsinki: Äidinkielen opettajain liitto.

- Repo, E. 2020. “Discourses on Encountering Multilingual Learners in Finnish Schools.” Linguistics and Education 60 (2): 100864. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2020.100864.

- Schleppegrell, M. 2004. The Language of Schooling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Shohamy, E. 2006. Language Policy. Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. London: Routledge

- Seltzer, K. 2019. “Reconceptualizing “Home” and “School” Language: Taking a Critical Translingual Approach in the English Classroom.” TESOL Quarterly 53 (4): 986–1007. doi:10.1002/tesq.530.

- Spolsky, B. 2004. Language Policy. Cambrigde: Cambridge University Press.

- Statistics Finland. 2015/2021. Finnish National Statistical Service.

- Suni, M., and S. Latomaa. 2012. “Dealing with Increasing Linguistic Diversity in Schools: The Finnish Example.” In Dangerous Multilingualism, edited by J. Blommaert, S. Leppänen, P. Pahta, and T. Räisänen, 67–95. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Suuriniemi, S.-M., M. Ahlhom, and V. Salonen. 2021. “Opettajien Käsitykset Monikielisyydestä: heijastumia Koulun Kielipolitiikasta.” In Koulun Monet Kielet. Plurilingualism in the School, edited by M. Ahlholm, I. Piippo, and P. Portaankorva-Koivisto, Vol. 13, 44–69. Jyväskylä: Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistyksen julkaisuja.

- Tarnanen, M., and Å. Palviainen. 2018. “Finnish Teachers as Policy Agents in a Changing Society.” Language and Education 32 (5): 428–443. doi:10.1080/09500782.2018.1490747.

- Teemant, A. 2018. “Sociocultural Theory as Everyday Practice: The Challenge of K-12 Teacher Preparation for Multilingual and Multicultural Learners.” In The Routledge Handbook of Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Development, edited by J. Lantolf, M. Poehner and M. Swain, 529–550. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Teemant, A., C. Leland, and B. Berghoff. 2014. “Development and Validation of a Measure of Critical Stance for Instructional Coaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 39: 136–147. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.008.

- Tähtinen, J., E. Laakkonen, and M. Broberg. 2020. Tilastollisen Aineiston Käsittelyn ja Tulkinnan Perusteita. Kasvatustieteiden tiedekunnan julkaisuja. Turku: Turun yliopisto.

- Verplaetse, L., and N. Migliacci. 2008. Inclusive Pedagogy for English Language Learners: A Handbook of Research Informed Practices. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Zacheus, T., M. Kalalahti, and J. Varjo. 2017. “Cultural Minorities in Finnish Educational Opportunity Structures.” Finnish Journal of Social Research 10 (2): 132–144. doi:10.51815/fjsr.110772.

- Zilliacus, H., B. Paulsrud, and G. Holm. 2017. “Essentializing vs. Non-Essentializing Students’ Cultural Identities: Curricular Discourses in Finland and in Sweden.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 12 (2): 166–180. doi:10.1080/17447143.2017.1311335.

Appendix

Background information

After School

Question section

Multilingual repertoires

The experience of practices

The experience of first language(s)

The experience of participating in situations