Abstract

This research project involved a mixed-methods study investigating language-related challenges of first-year students at an English Medium Instruction (EMI) university in Hong Kong. The two-phased sequential study employed a questionnaire survey and semi-structured student interviews. The survey and interview findings indicate that first-year students face a number of language-related academic challenges during their first year at an EMI university in writing, reading, speaking, and listening, many of which appear to stem from lower levels of vocabulary knowledge in English, unfamiliarity with academic and technical terminology, and limited exposure to varieties of English. Additionally, the findings suggest that these challenges can vary significantly based on background and first language, relating specifically to three different demographic student groups: local Hong Kong Cantonese-speaking students, Putonghua-speaking mainland Chinese students, and non-Chinese speaking local and international students.

1. Introduction to the global phenomenon of EMI

The continued growth of English-medium instruction (EMI) programmes on a global level, and the ongoing trend of universities in non-Anglophone countries to ‘internationalize’ (Chan and Ng Citation2008; Walkinshaw et al. Citation2017; Bowles and Murphy Citation2020) has led to increasing student mobility and a rising number of non-local students integrating into EMI higher education institutes (HEIs), most notably in Asia in recent years (Huang Citation2006; Mok Citation2007; Haberland et al. Citation2013; Hou et al. Citation2013; He and Chiang Citation2016; Tsou and Kao Citation2017), and in Europe (Fabricius et al. Citation2017; Smit Citation2018). Söderlundh (Citation2013) views EMI as ‘a strategy of transnational character in the process of internationalising higher education’.

Macaro et al. (Citation2018) define EMI as ‘The use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the first language of the majority of the population is not English’ (p. 37). EMI at the tertiary level has been expanding globally since the 1990s, most rapidly in Europe due in large part to the 1999 Bologna Process (Wächter and Maiworm Citation2014), but also in Africa (Kamwangamalu Citation2013), the Middle East (Pessoa et al. Citation2014), and Asia (Galloway et al. Citation2017), particularly in East and Southeast Asia (Floris Citation2014; Kirkpatrick Citation2017). South-Asian countries and territories formerly colonized by England, such as Hong Kong (the context of the current study), India, and Malaysia also have witnessed an increase in EMI programmes (see Evans and Morrison Citation2011; Fenton-Smith et al. Citation2017; Kirkpatrick Citation2017).

Similar to other EMI contexts in Asia and Europe, as EMI HEIs in Hong Kong and elsewhere continue the trend of internationalizing by increasing the number of international students, classrooms that were largely made up of local students speaking the predominant L1 are becoming increasingly diverse. While many of the local students in such contexts may share a similar L1, non-local students are likely to be from a variety of different linguistic backgrounds and may have varying levels of fluency in English which differ from those of local students. Consequently, non-local students may face different challenges than those experienced by local students when learning subject content through English.

EMI language-related or linguistic challenges refer to the ‘difficulties experienced when instructors and/or students are working in a non-native language’ (Bradford Citation2016, p. 341). An in-depth systematic review of 83 empirical studies related to EMI in higher education (HE) revealed that in nearly all of the studies, there were ‘a number of deep concerns’ communicated by both students and lecturers in terms of ‘student English language proficiency, lecturer proficiency, or both’ (Macaro et al. Citation2018, p. 52). Previous EMI–related studies have shown differences between local and non-local students in terms of language related challenges, attitudes towards EMI programmes, and student interaction (see Kim et al. Citation2014 in Korea; Chapple Citation2015 in Japan; Kuteeva Citation2020 in Sweden). These combined with differences in English proficiency levels could influence students’ learning experiences, knowledge of subject content, and overall academic performance.

Research in the European EMI context indicates that local students generally use their respective predominant L1s more than they use English - both as support languages or more (Doiz et al. Citation2013; Söderlundh Citation2013; Mortensen Citation2014; Smit Citation2018; Kuteeva Citation2020). Likewise, in the Hong Kong context, in-class student-led discussions, group discussions, and questions for lecturers are generally done by local students in Cantonese (Evans and Green Citation2007; Evans and Morrison Citation2011; Shepard and Morrison Citation2021). On the other hand, in a more recent study, Sung (Citation2020, p. 262) found that international students in Hong Kong use ‘English as a de facto lingua franca for intercultural communication in the university and emphasised its value for their academic and social integration’. Other researchers have pointed to a tendency of EMI research in East Asia to overlook the international student experience (Kim et al. Citation2014). As these longstanding EMI contexts continue to internationalize and attract non-local students of varying linguistic backgrounds into their EMI programmes, research into EMI language-related challenges of these students is essential—a gap that this study aims to address. This study examines and compares language-related challenges experienced by local and two groups of non-local students at an EMI university in Hong Kong.

2. EMI in Hong Kong

2.1. Background and evolution

A central aim of the rapid expansion of EMI for many universities globally is to increase student enrolment of international students (Macaro et al. Citation2018). As a result, universities worldwide are grappling with meeting the linguistic needs and preparedness of both local and international students, and Hong Kong makes for an intriguing context to explore these issues. While Hong Kong has a history of teaching through English that spans more than 170 years (Evans Citation2008), recent decades have seen new complexities emerge. Following the 1997 transfer of sovereignty from Great Britain to China, Hong Kong (HK) adopted a Chinese medium of instruction (CMI) policy (i.e., spoken Cantonese and written standard Chinese) which reduced the use of EMI in public secondary schools from around 90 per cent to only 25 per cent (Evans Citation2002). In response to backlash over this reduction (Poon Citation2010), the HK government implemented a ‘fine-tuning’ policy in 2010 (Evans Citation2011) offering CMI schools some flexibility in terms of medium of instruction (MOI) practices based on the schools’ own determinations of students’ needs and qualifying criteria. Presently, fewer than a third of secondary schools in Hong Kong are EMI schools, while the large majority are CMI and have retained a ‘biliterate/trilingual’ policy (Evans Citation2013) intended to allow students to learn written Chinese and English while developing speaking proficiency in Cantonese, Putonghua, and English. In most of these schools, CMI is used in all classes with the exception of one or two academic subjects taught in English.

In contrast, the medium of instruction (MOI) at the tertiary level is predominantly English. Of the eight Hong Kong universities funded by the University Grants Committee (UGC), six are EMI universities, and two maintain a mixed-medium of instruction policy using both Cantonese and English. While generally supported (Choi Citation2010), the EMI policy at the university level has been somewhat problematic given that Cantonese is used by the large majority of students as their usual language (Evans and Green Citation2007). A longitudinal study conducted from 2004 to 2007 (Evans and Morrison Citation2011) exploring language-related challenges found that Cantonese-speaking university students experienced considerable difficulties using English. Their study revealed academic writing to be the most difficult of the four language ‘macro-skills’, specifically in terms of academic writing style, cohesion in texts, and complex grammatical structures. Students reported that insufficient vocabulary knowledge was the main factor preventing them from communicating ideas effectively and fluently in written and spoken English, while also acknowledging grammatical issues and pronunciation challenges. Lo and Murphy (Citation2010) compared the L2 English vocabulary knowledge of students in two Hong Kong secondary schools, one CMI and the other EMI, and found that greater exposure to English in EMI schools resulted in ‘consistently demonstrated superior vocabulary knowledge’ (p. 228). Tsang (Citation2009) claimed that local Hong Kong students from CMI schools had around half as much chance of achieving the compulsory English language qualifications for admission to Hong Kong’s EMI universities as those coming from EMI secondary schools. Consequently, a large number of Cantonese-speaking students face considerable challenges when making the transition from CMI secondary schools to EMI universities (Evans and Green Citation2007, Lin and Morrison Citation2010, Lo and Murphy Citation2010; Evans Citation2009).

Local Cantonese-speaking students make up the overwhelming majority of the student populations in Hong Kong, but the number of non-Cantonese speaking students at all levels of education has been growing rapidly over the past two decades, changing the linguistic landscape in classrooms. As part of the push by the Hong Kong government to ‘internationalize’ Hong Kong’s higher education (Chan and Ng Citation2008), Hong Kong universities have experienced a substantial increase in the number of international or ‘non-local’ students. According to the Hong Kong University Grants Committee (Citation2019) in the 1997/98 academic year, there were 1,355 non-local students at all eight UGC funded universities, comprising only around 2% of the total student population. By the 2021/Citation2022 academic year, the number of international students rose to non-local students, making up more than 20% of all Hong Kong university students and representing an increase of more than 900% over two decades. This substantial increase of non-Cantonese speaking students has widened the linguistic diversity at Hong Kong universities, which until recently consisted almost exclusively of local Cantonese-speaking students and presents various challenges for both learning and teaching. The growing linguistic diversity in the classrooms is likely to affect students’ language-related challenges and learning experiences at EMI universities in Hong Kong, and may mirror and inform other EMI contexts globally which are also witnessing changing demographics in their student populations.

2.2. Rationale and research questions

EMI-related research on language-related challenges at the tertiary level has traditionally focused on local students (see, for example, Kamasak et al. Citation2021 in Turkey; Aizawa et al. Citation2023 in Japan; Rose et al. Citation2020 in China), or in the case of Hong Kong, the local Cantonese-speaking student population (Flowerdew et al. Citation2000; Evans and Green Citation2007; Evans and Morrison Citation2011). Similar to Hong Kong, increased student mobility and the rise in EMI ‘international’ universities in many parts of the world has resulted in EMI classrooms that are more linguistically and culturally diverse. As such, there is a growing need for EMI-related research that extends beyond the issues faced by the local majority of students, and that takes into account the growing non-local student population. Therefore, the findings of this research have significant implications not only applicable for EMI HEIs in Hong Kong, but for many other EMI contexts as well. Furthermore, as Baker and Hüttner (Citation2017) point out, the need for research in this area extends beyond EMI HEIs and could have considerable implications for non-EMI contexts as diverse multilingual classrooms have also increased in Anglophone HEIs, such as in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Thus, the purpose of this study is to explore students’ language-related challenges during their first year at university and to examine how these may vary between local Cantonese-speaking students, Putonghua-speaking students from Mainland China, and other non-Chinese-speaking international students. The aforementioned background, conditions, and rationale necessitated the following research questions central to this study:

Against a backdrop of increased internationalization, how do students’ reported language-related challenges compare to previous research conducted 15 years prior?

Do language-related challenges faced by Hong Kong tertiary students in EMI programmes in their first year of study vary based on student demographic groups?

Specifically, does the reported level of difficulty vary between local Cantonese-speaking students, Putonghua-speaking students from Mainland China, and other non-Chinese-speaking non-local students?

3. The study

The data and findings discussed in this paper are part of a larger case study by the first author which employed both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. While some exploratory descriptive results of this study have been presented in Shepard and Morrison (Citation2021), this paper applies a sequential explanatory design (Ivankova et al. Citation2006) to the data and is presented for the first time. A self-report questionnaire was administered, followed by semi-structured student interviews for a more comprehensive understanding of students’ language challenges. Ethical approval was granted by the home university of the researchers as well as the university in HK, where the data were collected. An online link to the survey was provided to students in class, for them to complete in their own time. Participation was voluntary.

3.1. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed following a similar design pertaining to students’ self-efficacy related to using academic English at university (Evans and Green Citation2007; Evans and Morrison Citation2011). Participants were asked to rate the degree of difficulty of 45 different items related to academic writing (15), reading (10), speaking (10), and listening (10) on a scale ranging from 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult). (See supplementary materials for full abridged questionnaire, and the IRIS database for the full questionnaire.) A 7-point Likert type scale was selected as previous research suggested that 7-point scales are more suitable for unsupervised questionnaires distributed electronically and generally result in greater accuracy of participants’ evaluation (Finstad Citation2010).

3.2. Questionnaire participants and setting

Participants in the questionnaire were 636 undergraduate students in their first year at a university in Hong Kong. Participants ages ranged from 17 to 20 years (M = 18.41, SD = .610) with 46.7% identifying as female (297), 52.4% as male (333), and 0.9% as ‘prefer not to say’ (6). Students were from seven different faculties including Applied Science and Textiles, Business, Engineering, Construction and Environment, Health and Social Science, Hotel and Tourism Management, and Humanities. Students also reported twelve different first languages (L1s), including Cantonese (484), Putonghua (106), Kazakh (11), Korean (10), Indonesian (10), Russian (8), Hokkien (2), French (1), Kinyarwanda (1), Taiwanese (1), Thai (1), and English (1).

Of the 819 students who initially responded, 51 failed to complete the questionnaire in its entirety. Approximately 17% of participants (108) were omitted as they were not first-year students, and another 11 were excluded based on being 21 or older, as they represented non-typical first-year university students in Hong Kong who had not entered from high school. Suspicious answering patterns by another seven participants (i.e., all 1’s, 4’s, or 7’s) resulted in their subsequent removal. The remaining data set was screened for univariate outliers, resulting in the identification of six cases with z-scores > 3.29, which were excluded in line with conventional criteria (Tabachnick and Fidell Citation2013), resulting in a final sample of 636, representing approximately a quarter of the first-year undergraduates enrolled at the university that academic year.

3.3. Student interview participants

Selection of the interview participants was purposive following maximum variation sampling (Patton Citation2002). The procedure was as follows: Of the total number of the questionnaire survey sample (n = 636), approximately 83% of respondents (531) reported interest in participating in student interviews by consenting to be contacted and providing first names and email addresses. Of those respondents, based on their various L1s and academic fields of study, a total of 96 were targeted for selection and were contacted. Final selection of participants was based on Patton’s (Citation2002) ‘purposeful sampling’ approach in order to target participants who could provide rich data through ‘maximum variation sampling’ (2002, p.73).

Interview participants (n = 32) ages ranged from 17 to 20 years (M = 18.43, SD = .669) with 66% female (21) and 34% male (11) and represented the same seven academic faculties and schools mentioned previously. They also represented nine different L1s, including 12 Cantonese speakers, seven Putonghua speakers, and 13 others who spoke either Indonesian, Russian, Kazakh, Korean, French, Kinyarwanda, or English (1). All twelve Cantonese speakers were from Hong Kong, while the Putonghua speakers were from Mainland China (4), Taiwan (2), and Inner Mongolia (1). The interviews were semi-structured, conducted in English, and questions focused mainly on students’ language-related challenges (See Appendix B, supplementary material).

3.4. Data analysis

The online questionnaire data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (Version 25). Descriptive statistics including the mean and standard deviation for each of the items were calculated to compare the range and variance of scores between the different groups. One-way ANOVA tests were conducted to compare scores between the three groups, and Tukey HSD post-hoc tests were conducted. As the three sample sizes were unequal, Welch’s F was used for correction as an adjustment for F and the residual degrees of freedom in order to counter any potential issues arising from violating the assumption of homogeneity of variance (Jan and Shieh Citation2014); Hence, Welch’s p-value was interpreted and used to replace the standard ANOVA p-value. As the questionnaire employed seven different subscales with varying numbers of items, the internal consistency of each construct was measured using a Cronbach’s alpha test. The academic writing (α = .93), reading (α = .92), speaking (α = .93), and listening (α = .93) skills subscales were each found to have high internal consistency.

The 32 student interviews produced approximately nine and a half hours of audio recordings, averaging around 17 and a half minutes in duration and ranging from 00:10:39 (shortest) to 00:31:45 (longest). The audio recordings were converted to mp3 files enabling them to be transcribed using transcription software. The transcriptions were then compared with the audio recordings and edited for accuracy before coding.

Data from the semi-structured interviews were examined through a ‘six-phase approach’ for thematic analysis, as proposed by Braun et al. (Citation2018, p.10), and all coding and thematic analysis of the interview transcriptions were completed using NVivo 12 Pro. All participants were anonymized by means of pseudonyms, which are used in the reporting and discussion of the findings.

4. Results

4.1. Academic language-related challenges compared to prior research (RQ1)

A detailed descriptive analysis of individual items can be found in Shepard and Morrison (Citation2021). This paper offers a focused examination of the data in terms of the increased multilingual EMI classrooms that have emerged as a result of internationalization (RQ1), and sets the stage for between-group analysis (see RQ2).

In terms of specific language-related challenges for students as a whole, while many of the findings echoed those of Evans and Morrison (Citation2011) study, some new issues emerged which seem to relate to the increased multilingual diversity in the classrooms compared with that between 2004 and 2007 when the researchers collected their data. For example, while challenges related to writing and reading remained very similar to the earlier study, the current findings related to listening and speaking appear to differ.

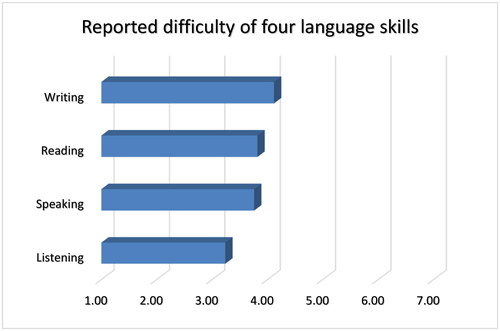

As can be seen in , respondents reported academic writing to be the most challenging (M = 4.12), followed in order by reading (M = 3.82), speaking (M = 3.76), and listening (M = 3.24), which is largely in line with the findings from Evans and Morrison (Citation2011).

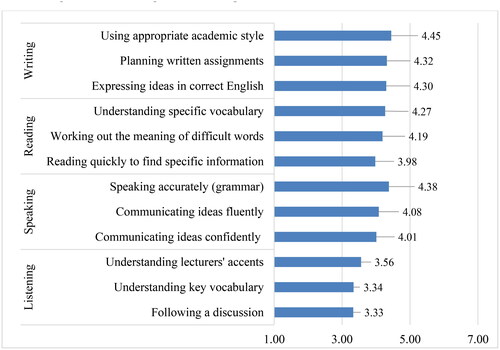

shows the most challenging three items for each of the four skills according to the overall mean score of each item. These highlight the type of activities within the four academic skills that EMI students appear to struggle with the most. By and large the questionnaire results mirror those of Evans and Morrisons, indicating that students continue to have challenges in the same areas of academic literacy. One exception was the item of ‘understanding lecturers’ accents’ which was considerably more marked with difficulty by the students in our study than those in Evans and Morrison (Citation2011), warranting further investigation of the qualitative data.

Figure 2. Most difficult aspects of writing, reading, speaking, and listening.

Scale: 1 = very easy, 7 = very difficult.

The student interviews provided more nuanced data of the language-related challenges associated academic writing, reading, speaking, and listening. When asked about the most challenging aspects of their English use in EMI, ten of the students, which included four speakers of Cantonese, and one speaker each of English, Indonesian, Kazakh, Korean, Putonghua, and Russian, expressed that their main challenges were associated with writing, which was in agreement with the data from the questionnaire. Most stated that difficulties stemmed from unfamiliarity with academic style, grammatical difficulties and a lack of vocabulary. One international student described her writing challenges as having to do primarily with achieving academic style, supporting the findings from the quantitative data:

I would think that writing is more important and more challenging because here we have to use academic writing, which I didn’t know how to use when I was in high school. So, I needed to adapt to this and try to learn as fast as I can.

(Adelle, Female, Russian L1)

I think I’m weak in writing because my grammar is not really good. And I have difficulties in writing that correctly. So I’m afraid of writing.

(Linda, Female, Cantonese L1)

And reading because of my vocabulary; it’s not really good So, yeah. Sometimes I need to check for a dictionary all the time I’m reading.

(Linda, Female, Cantonese L1)

I think the most difficult is speaking. Because I need to think, think in myself, and I need to generate many vocabularies and grammars, which is different – totally different, a huge difference with Cantonese.

(Christina, Female, Cantonese L1)

Well, ninety percent of the time I use Cantonese and ten percent I use English.

(Kelvin, Male, Cantonese L1)

I would say half and half, because you can talk to the teacher in Chinese, and usually in English, but when you have to, like, discuss with your classmates, usually we’ll do [sic] in Chinese – uh, Cantonese, because it’s our Mother language, so, of course Cantonese will be easier for us.

(Edward, Male, Cantonese L1)

So basically because we have, uh, cultural diversity inside the group, everybody’s tending to use English.

(Adelle, Female, Russian L1)

I think the most difficult problem is the accent. There are some different accent here at our university like [sic] Indian accent. Very very difficult to recognize for me.

(Celeste, Female, Putonghua L1)

Actually, I think the people from the English speaking countries like from the United States, from the U.K. they speak English more rapidly and they speak it faster, and but, and I just can’t catch up with them.

(Peter, Male, Putonghua L1)

4.2. Language-related challenges: Local vs non-local students

All the UGC publicly funded universities categorize students into one of three categories: Local Cantonese-speaking students from Hong Kong; non-local Putonghua-speaking students from Mainland China; and non-local (international) students. The non-local international students are generally from other parts of Asia, Europe, the Americas, and elsewhere, and are often referred to as ‘Internationals’. This tripartite grouping is not dissimilar to other areas of the world, such as many European universities, which classify their student population as ‘home/local’, ‘EU’ and ‘International’. The university in this study has different admission requirements for each of the three groups including different minimum levels of English proficiency, which is common in all UGC universities in Hong Kong. These three groups are termed herein as ‘CL1’ for the local Cantonese speakers, ‘PL1’ for the Putonghua speakers, and ‘OL1’ referring to the non-local international students.

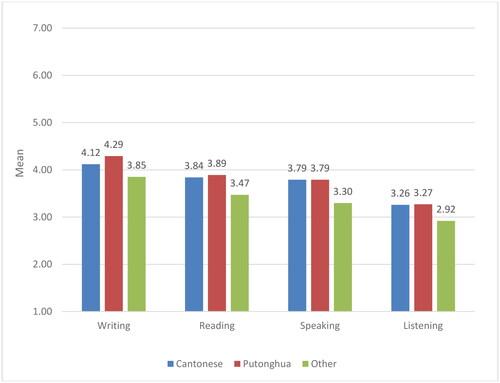

In terms of academic challenges, respondents’ mean scores for each of the four macro-skills are illustrated across the three groups as shown in . All three groups followed the same order of difficulty (i.e., writing, reading, speaking, listening), but with variations among between groups. The mean scores were higher for the PL1 group than the other two groups in writing, reading, and listening, indicating higher levels of perceived difficulty for this group. Alternatively, mean scores are shown to be consistently lower for the OL1 group in all four macro-skills, suggesting they found the four macro-skills to be less challenging than the other groups overall.

As can be seen in , there were statistically significant differences between the groups in reported challenges for writing, reading, and speaking. Results are corrected with Welch’s F for the obvious unequal sample sizes among the three groups (Jan and Shieh Citation2014). Results revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in mean responses between at least two groups for writing (F(2, 633) = [3.815], p = 0.025), reading (F(2, 633) = [3.674], p = 0.029), and speaking (F(2, 633) = [4.299], p = 0.016). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey’s HSD test were also carried out.

Table 1. Mean scores of three L1 groups for academic challenges.

Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple comparisons found that the mean value writing difficulty was significantly higher for the PL1 group compared to OL1 group (p = 0.025), indicating that the Putonghua-speaking students found academic writing significantly more challenging than the non-local students. Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple comparisons also revealed differences in mean scores among the groups in terms of academic reading between the PL1 and OL1 groups (p = .048) as well as the PL1 and CL1 groups (p = .046), indicating that both the Putonghua speakers and Cantonese speakers also found academic reading significantly more challenging than the non-local students. There was no statistically significant difference between the Cl1 and Pl1 groups. In regards to speaking, post hoc tests revealed significant differences between the OL1 group and the PL1 group ((p = .030) and CL1 groups (p = .010), indicating that Cantonese-speaking and Putonghua-speaking students reported academic speaking significantly more challenging than the internationals.

5. Discussion and conclusions

In terms of the specific language-related challenges faced by year-1 students, results indicated that writing is the most challenging of the four language-skills. Students reported struggling with a variety of writing-related activities, such as planning what to write, organizing their ideas, finding and selecting appropriate sources, integrating sources into their work, summarizing and paraphrasing, adhering to academic format, structure and style, and expressing their ideas using appropriate vocabulary. Difficulties in academic writing are pervasive in the EMI literature both in the research from Hong Kong (Lin and Morrison Citation2010; Evans and Morrison Citation2011) and elsewhere (see, for example, Rose et al. Citation2020 in China, and Kamasak et al. Citation2021 in Turkey). It is clear that Year 1 EMI students would benefit from further L2 writing support as the current provision in many EMI models globally may be insufficient to alleviate their reported difficulties in this areas.

In terms of reading-related challenges, the main obstacle impeding students’ success appears to be a lack of knowledge of vocabulary in English. With vocabulary so central to underpinning challenges, EMI in higher education might advantage students from a EMI high school background. Previous research has shown that EMI high school students develop a much larger vocabulary than their CMI counterparts (Lo and Murphy Citation2010)—a situation that continues into their first year of university studies (Lin and Morrison Citation2010). These findings have also been found in other EMI contexts such as Japan (see Aizawa and Rose Citation2020). Such results suggest that students from a non-English-medium high school background may benefit from more intensive vocabulary support during their first year academic literacy support programmes, which concurs with findings in the wider literature on EMI. It also raises issues regarding whether students from an L1 medium high school background are at an inherent disadvantage when studying through the medium of English, which is an issue raised not only in EMI settings, but also in Anglophone higher education contexts (see Trenkic and Warmington Citation2019).

A number of EMI-related empirical studies highlight the link between proficiency and challenges in EMI programs with many suggesting that proficiency may be the most significant predictor of success (Rose et al. Citation2020; Aizawa et al. Citation2023). As mentioned previously, for admission to publicly funded universities in Hong Kong, there are generally different English language proficiency requirements for each of the three groups discussed here. The most stringent requirements are in place for the non-local ‘internationals’, followed by those for the local CL1s and the mainland PL1s respectively. Accordingly, the non-local international students may be entering local Hong Kong universities with generally higher English proficiency levels, which would presumably result in overall lower levels of language-related challenges in EMI programs. These findings highlight inherent systematic problems in EMI models of education where varying admissions benchmarks are used for different cohorts of students.

Moreover, as these international students are generally comprised of various L1s and backgrounds, they seem to be using English as the default lingua-franca much more than their CL1 or PL1 counterparts (Shepard and Morrison Citation2021). Alternatively, local Cantonese-speaking students are for the most part at home in their L1 environment where Cantonese is ubiquitous in Hong Kong for almost every aspect of daily life apart from their university lectures. While the majority of local Hong Kong students have had many years of English classes, either periodically in CMI secondary schools or more regularly in the (fewer number of) EMI secondary schools, they still use Cantonese as their ‘every day’ language. As such, local students may experience greater difficulty than the internationals in switching to L2 English while living and studying in their natural L1 Cantonese environment. These findings might resonate in other educational systems which see large numbers of international students who share an L1 (such as in UK postgraduate programs, as reported in Baker and Hüttner (Citation2017)), and may have more difficulties adapting to using the L2 in their wider contexts.

This raises broader issues of the efficacy of EMI in contexts where a majority of students share a common L1. While the majority of local students have had several years of exposure to English from an early age, their language for everyday use and almost all spoken interaction is Cantonese. Moreover, the medium of instruction in the public school system in Hong Kong is largely CMI. Public primary schools in Hong Kong generally use CMI, and CMI is used by more than two-thirds of schools at the secondary level. This also holds true for language use within EMI universities: while instruction is predominantly through English, local students generally use Cantonese for spoken interaction both in and out of the classrooms unless they are taking part in formal whole-class discussions, presentations, or assessments (Evans and Morrison Citation2011; Shepard and Morrison Citation2021). Apart from academic settings, for many local students, English is largely seen as peripheral to their everyday lives until it may be needed at some point in future workplace environments. Findings in other EMI contexts suggest that while local students attach some specific roles for English, its use generally remains limited to some academic interaction, and that the local language plays a greater role – both in and out of the academic setting. Haberland and Mortensen (Citation2012, p. 4) explain that ‘English rarely exists all by itself at the international university, but rather tends to play a role in [a] system in which the local language (or languages) will often also have an important role’. As such, it is not surprising that local students experience linguistic challenges and difficulties using English at the tertiary level where they are required to adapt to a much higher level of English for academic purposes than what they experienced in secondary schools. It can also be argued that local students are at somewhat of a disadvantage when compared to either their international counterparts, who are using English in a more authentic context as an academic lingua franca. Unlike international students, local EMI students are in the precarious position of being expected to use L2 English on a regular basis for academic purposes while remaining in their L1 home environment, where their everyday language is entrenched and ever-present.

International students, as suggested in research findings from other EMI contexts, seem to have a greater association with English as the lingua franca in HEIs (Söderlundh Citation2013; Kim et al. Citation2014; Chapple Citation2015). Söderlundh (Citation2013, p. 125) explains that language norms are constructed so that EMI ‘fits local expectations, traditions and ideologies’. In the Swedish EMI context, Söderlundh (Citation2013, p. 125) found that while non-local exchange students were generally linked with English, ‘Swedes are associated with English and Swedish’. Chapple (Citation2015) noted that local Japanese students were less likely than the international students to interact in English with students from other countries. In the Korean EMI context, Kim et al. (Citation2014) reported that international students found interaction with local students difficult due to the latter’s tendency to use Korean in the classroom. Similarly, in the Hong Kong context, the OL1s, unlike the CL1s and PL1s, generally did not share a common L1 and relied heavily on English as the lingua franca when interacting within the OL1 group as well as with those from both the CL1 and PL1 groups.

Such disparities between locals and non-locals in terms of language-related challenges and the use of English for classroom interaction could result in what Chapple (Citation2015) termed ‘Double-sided dissatisfaction’, where neither the local students nor the non-local students seem to benefit from EMI to the fullest extent. While local students may feel that the learning through English is considerably challenging and prefer to use more L1 for general classroom interaction and additional language support, non-locals may have experience considerably fewer challenges and prefer more interaction in English with local students.

5.1. Limitations

While the findings of this study have shed light on EMI challenges by local and non-local students in Hong Kong, there are several limitations which affect how these results are interpreted. First, data collection via our questionnaire may have narrowed the scope of challenges investigated by only probing language-related issues surrounding academic skills. While strong reliability of these constructs was established, the focus of these constructs was solely on academic language-related challenges. As such, we may have missed core difficulties faced by EMI students of a broader sociocultural or sociolinguistic nature, such as challenges adjusting to new educational cultures. Future research on EMI student challenges may benefit from a widening of the lens of the types of challenges captured.

Another limitation of the study was its cross-sectional approach to data collection from first-year university students. While this approach was useful to compare data according to group demographic differences, the findings are limited to challenges experienced by students at the beginning of their EMI experience and cannot report on how these challenges might be exacerbated or alleviated as these students progress through their degree program. Future research could address this limitation via a longitudinal study tracking a cohort of EMI students over the duration of their studies.

Lastly, the online survey and the semi-structured interviews were conducted with students only. As such, the findings are based solely on the attitudes, challenges, and perspectives of the students themselves, and do not take into account the views and perspectives of other EMI stakeholders, namely language support instructors or EMI subject-content lecturers. While one could argue that within the EMI context in HEIs in Hong Kong students are the primary EMI stakeholders, alternative perspectives and viewpoints from other stakeholders could provide greater insight into the learning complexities and challenges faced by students. Future EMI-related empirical studies within this context could be expanded to include interviews and surveys from other EMI stakeholders who may be able to evaluate and gauge students’ challenges more objectively through the vantage points of those with pedagogical experience and training.

5.2. Conclusion

The HK HE sector has established academic language programmes in the first year of study to ease the transition of students to tertiary study, which in many ways address the academic difficulties outlined in this study. However, many of these programmes were originally established during an era when most students in universities had attended HK high schools and had come from somewhat homogenous academic backgrounds. A rapidly internationalising HK has meant a growth in student numbers from more diverse settings, especially a rise in international students, a rise in students from local CMI high school backgrounds (post 1997), an influx of students with Putonghua as their L1, and an increase in local students who speak a non-Chinese L1. Our study has revealed differences in the challenges faced by students from different linguistic backgrounds, which may necessitate different types of academic language support to address these needs. While our study was conducted within the specific context of Hong Kong, the results might hold relevance to other EMI contexts that are rapidly adapting to similar changing student demographics.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aizawa I, Rose H. 2020. High school to university transitional challenges in English Medium Instruction in Japan. System. 95:102390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102390

- Aizawa I, Rose H, Thompson G, Curle S. 2023. Beyond the threshold: Exploring English language proficiency, linguistic challenges, and academic language skills of Japanese students in an English medium instruction programme. Lang Teach Res. 27(4): 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216882096551

- Baker W, Hüttner J. 2017. English and more: A multisite study of roles and conceptualisations of language in English medium multilingual universities from Europe to Asia. J Multiling Multicult Dev. 38(6):501–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2016.1207183

- Bowles H, Murphy AC. 2020. English medium instruction and the internationalisation of universities. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bradford A. 2016. Toward a typology of implementation challenges facing English-medium instruction in higher education: evidence from Japan. J Stud Int Educ. 20(4):339–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316647165

- Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. 2018. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong, P. (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health social sciences; Singapore: Springer Singapore, p. 843–860.

- Chan D, Ng PT. 2008. Similar agendas, diverse strategies: The quest for a regional hub of higher education in Hong Kong and Singapore. High Educ Policy. 21(4):487–503. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2008.19

- Chapple J. 2015. Teaching in English is not necessarily the teaching of English. IES. 8(3):1. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n3p1

- Choi PK. 2010. ‘Weep for Chinese university’: A case study of English hegemony and academic capitalism in higher education in Hong Kong. J Edu Policy. 25(2):233–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930903443886

- Doiz A, Lasagabaster D, Sierra J. 2013. Globalisation, internationalisation, multilingualism and linguistic strains in higher education. Stud Higher Educ. 38(9):1407–1421. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.642349

- Evans S. 2002. The medium of instruction in Hong Kong: policy and practice in the new English and Chinese streams. Res Pap Educ. 17(1):97–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520110084030

- Evans S. 2008. The introduction of English‐language education in early colonial Hong Kong. History of Education. 37(3):383–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/00467600600745395

- Evans S. 2009. The medium of instruction in Hong Kong revisited: Policy and practice in the reformed Chinese and English streams. Res Pap Educ. 24(3):287–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520802172461

- Evans S. 2011. Historical and comparative perspectives on the medium of instruction in Hong Kong. Lang Policy. 10(1):19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-011-9193-8

- Evans S. 2013. The long march to biliteracy and trilingualism: Language policy in Hong Kong education since the handover. Ann Rev Appl Linguist. 33:302–324. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190513000019

- Evans S, Green C. 2007. Why EAP is necessary: A survey of Hong Kong tertiary students. J English Acad Purposes. 6(1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2006.11.005

- Evans S, Morrison B. 2011. The first term at university: Implications for EAP. ELT J. 65(4):387–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq072

- Fabricius AH, Mortensen J, Haberland H. 2017. The lure of internationalization: paradoxical discourses of transnational student mobility, linguistic diversity and cross-cultural exchange. High Educ. 73(4):577–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9978-3

- Fenton-Smith B, Humphreys P, Walkinshaw I. 2017. English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing.

- Finstad K. 2010. Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: evidence against 5-point scales. J Usability Stud. 5(3):104–110.

- Floris FD. 2014. Learning subject matter through English as the medium of instruction: students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Asian Englishes. 16(1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2014.884879

- Flowerdew J, Miller L, Li DC. 2000. Chinese lecturers’ perceptions, problems and strategies in lecturing in English to Chinese-speaking students. RELC J. 31(1):116–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368820003100106

- Galloway N, Kriukow J, Numajiri T. 2017. Internationalisation, higher education and the growing demand for English: an investigation into the English medium of instruction (EMI) movement in China and Japan. London: British Council.

- Haberland H, Mortensen J. 2012. Language variety, language hierarchy and language choice in the international university. Int J Sociol Language. 2012(216):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2012-0036

- Haberland H, Lønsmann D, Preisler B. 2013. Language alternation, language choice and language encounter in international tertiary education. Dordrecht: Springer.

- He J. J., Chiang S. Y. 2016. Challenges to English-medium instruction (EMI) for international students in China: A learners’ perspective: English-medium education aims to accommodate international students into Chinese universities, but how well is it working?. English Today 32(4):63–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078416000390

- Hong Kong University Grants Committee. 2022. Profile of UGC-funded institutions. Retrieved from https://cdcf.ugc.edu.hk/cdcf/searchUniv.action?lang=EN.

- Hou AYC, Morse R, Chiang CL, Chen HJ. 2013. Challenges to quality of English medium instruction degree programs in Taiwanese universities and the role of local accreditors: A perspective of non-English-speaking Asian country. Asia Pac Edu Rev. 14(3):359–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-013-9267-8

- Huang F. 2006. Internationalization of curricula in higher education institutions in comparative perspectives: case studies of China, Japan and the Netherlands. High Educ. 51(4):521–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2015-6

- Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. 2006. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. 18(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05282260

- Jan SL, Shieh G. 2014. Sample size determinations for Welch’s test in one‐way heteroscedastic ANOVA. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 67(1):72–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12006

- Kamaşak R, Sahan K, Rose H. 2021. Academic language-related challenges at an English-medium university. J Engl Acad Purp. 49:100945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100945

- Kamwangamalu NM. 2013. Effects of policy on English‐medium instruction in Africa. World Englishes. 32(3):325–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12034

- Kim J, Tatar B, Choi J. 2014. Emerging culture of English-medium instruction in Korea: experiences of Korean and international students. Language Intercult Commun. 14(4):441–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2014.946038

- Kirkpatrick A. 2017. The languages of higher education in East and Southeast Asia: will EMI lead to Englishisation?. In: Fenton-Smith B., Humphreys P., Walkinshaw I. (Eds.), English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific. Multilingual Education. Vol. 21. Springer, Cham; p. 21–36.

- Kuteeva M. 2020. Revisiting the ‘E’ in EMI: students’ perceptions of standard English, lingua franca and translingual practices. Int J Bilingual Educ Bilingualism. 23(3):287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1637395

- Lin LH, Morrison B. 2010. The impact of the medium of instruction in Hong Kong secondary schools on tertiary students’ vocabulary. J English Acad Purposes. 9(4):255–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2010.09.002

- Lo YY, Murphy VA. 2010. Vocabulary knowledge and growth in immersion and regular language-learning programmes in Hong Kong. Language Educ. 24(3):215–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780903576125

- Macaro E, Curle S, Pun J, An J, Dearden J. 2018. A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Lang Teach. 51(1):36–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000350

- Mok KH. 2007. Questing for internationalization of universities in Asia: Critical reflections. J Stud Int Educ. 11(3-4):433–454.

- Mortensen J. 2014. Language policy from below: language choice in student project groups in a multilingual university setting. J Multiling Multicul Dev. 35(4):425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874438

- Patton MQ. 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Pessoa S, Miller RT, Kaufer D. 2014. Students’ challenges and development in the transition to academic writing at an English-medium university in Qatar. Int Rev Appl Linguistics Language Teach. 52(2):127–156. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2014-0006

- Poon AY. 2010. Language use, and language policy and planning in Hong Kong. Curr Issues Language Plann. 11(1):1–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664201003682327

- Rose H., Curle S, Aizawa I, Thompson G. 2020. What drives success in English medium taught courses? The interplay between language proficiency, academic skills, and motivation. Studies in Higher Education 45(11):2149–2161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1590690

- Shepard C, Morrison B. 2021. Challenges of English-medium higher education: The first-year experience in Hong Kong revisited a decade later. In D. Lasagabaster, A. Doiz Language use in English-medium instruction at university: International perspectives on teacher practice (pp. 167–192). New York: Routledge.

- Söderlundh H. 2013. Applying transnational strategies locally: English as a medium of instruction in Swedish higher education. Nordic J English Stud. 12(1):113–132. https://doi.org/10.35360/njes.278

- Smit U. 2018. Classroom discourse in EMI: On the dynamics of multilingual practices. In English-medium instruction from an English as a Lingua Franca Perspective. London: Routledge; p. 99–122.

- Sung CCM. 2020. English as a lingua franca in the international university: language experiences and perceptions among international students in multilingual Hong Kong. Lang Cult Curric. 33(3):258–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2019.1695814

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. 2013. Using multivariate statistics (6th edn). Boston (MA): Pearson.

- Tsang WK. 2009. The effect of medium-of-instruction policy on educational advancement in HKSAR society. Public Policy Digest. Retrieved from http://www.ugc.edu.hk/rgc/ppd1/eng/05.htm.

- Trenkic D, Warmington M. 2019. Language and literacy skills of home and international university students: How different are they, and does it matter?. Biling: Lang Cogn. 22(2):349–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136672891700075X

- Tsou W, Kao SM. 2017. Overview of EMI development. In English as a medium of instruction in higher education. Singapore: Springer; p. 3–18.

- Hong Kong University Grants Committee (UGC). 2019. General Statistics on UGC-funded Institutions/Programmes. https://cdcf.ugc.edu.hk/cdcf/searchProgramme.action?lang=EN.

- Wächter B, Maiworm F (Eds.) 2014. English-taught programmes in European higher education: The state of play in 2014. Bonn: Lemmens Medien GmbH.

- Walkinshaw I, Fenton-Smith B, Humphreys P. 2017. EMI issues and challenges in Asia-Pacific higher education: an introduction. In: Fenton-Smith B, Humphreys P, Walkinshaw I. (Eds.), English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific; Multilingual Education, vol. 21, p. 1–18. Cham: Springer.