Abstract

While translanguaging has gained increasing recognition as a multiliteracy pedagogy in English-medium instruction (EMI) education, research exploring its implementation in STEM classroom contexts remains limited. Furthermore, the interplay of EMI teachers’ professional identities and their instructional strategies has received little attention. This qualitative study explores how STEM academics in an EMI programme in China implemented translanguaging pedagogy, developed their professional identities, and examined the impact of identity on their classroom instructional language use. Drawing upon nexus analysis, the study maps the intersecting discourses influencing two EMI lecturers’ divergent language ideologies and translanguaging strategies. The findings highlight the role of teacher identity and agency in navigating institutional and classroom discourses, facilitating planned and effective translanguaging pedagogy. The study reveals identity struggles within the examined institution, where academic staff faced a challenge in balancing their roles as effective EMI teachers and successful researchers due to a discourse of research meritocracy and were constrained in exploring translanguaging pedagogy due to a discourse of internationalism. These challenges undermined their motivation to invest in teaching identity and pedagogical skills. This study underscores the need for a balanced view of research and teaching, more robust teacher evaluation systems, and institutional support to foster effective translanguaging pedagogy in EMI by incorporating teacher identity construction into EMI teacher preparedness.

Introduction

English medium instruction (EMI) has gained popularity in higher education worldwide, notably in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects (Wächter and Maiworm Citation2014; Macaro Citation2018); China is also part of this trend (Hu Citation2009; Jablonkai and Hou Citation2021). In the context of STEM-EMI in China, students whose foundational disciplinary knowledge primarily resides in their L1 Chinese often face language challenges when studying advanced academic concepts and topics in English (e.g. Jiang et al. Citation2019). The students’ insufficient (academic) English proficiency has been identified as a key factor contributing to the discrepancy between EMI goals outlined in policy documents and the actual practices in classrooms, where Chinese is frequently utilised as a ‘compromised’ language practice (Hu and Lei Citation2014). Recent studies have increasingly recognised that EMI across diverse contexts is seldom exclusively conducted in English but is instead multilingual in nature (Mazak and Carroll Citation2016). Consequently, scholars advocate for a translanguaging perspective in EMI teaching to better capture the fluidity of language use in EMI classes and to leverage the multilingual resources and identities of teachers and students in the learning and teaching process (Paulsrud et al. Citation2021). Research on translanguaging pedagogies in EMI aligns with the contemporary call in applied linguistics for ‘researching multilingually’ (Holmes et al. Citation2013) in terms of an ecological view of linguistic diversity within the research context and the endeavours to normalise the teaching and learning practices based on students’ full linguistic repertoires.

Despite the growing attention given to translanguaging in EMI literature, research exploring teachers’ implementation and practice of translanguaging pedagogies in STEM classrooms remains limited, particularly in China (with a few exceptions noted by Gu and Ou forthcoming; Yuan and Yang Citation2023). Additionally, there is a dearth of studies into the interplay of EMI teachers’ professional identity and their use of translanguaging pedagogical approaches. It is crucial to understand the role of teachers’ professional identity – how teachers perceive themselves professionally and enact their professional roles (Beijaard et al. Citation2004) – in moulding their translanguaging practices for effective implementation. EMI teachers often navigate multiple linguistic and cultural factors as they engage with classroom teaching (e.g. Trent Citation2017; Xu and Ou Citation2022). Their professional identities, influenced by their language expertise, disciplinary backgrounds, and institutional contexts (van Lankveld et al. Citation2017), can significantly impact their beliefs, decision-making, and teaching practices. Therefore, this study aims to explore how STEM teachers’ professional identity influenced their translanguaging pedagogical practices in a Chinese EMI context.

The present study contributes to this special issue with a critical examination of the utilisation of multilingual and multimodal resources by EMI teachers in classroom teaching. It explores the intricate relationship between various levels and dimensions of discourses regarding EMI policies and practices, ranging from institutional decisions and values to individual teachers’ beliefs and actions. Using nexus analysis (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004; Hult Citation2017), an ethnographic discourse analytical approach, we collaborated with bi/multilingual STEM teachers from the investigated institute and worked with diverse types of multilingual data to uncover how teachers constructed their professional identities in their situated context of EMI education and how these identities impacted their use of translanguaging practices in classrooms. This study provides insights into the complexities of language, teacher identity, and pedagogical approaches in STEM-EMI contexts. It also has practical implications for EMI policymaking and teacher professional development, designing context-specific strategies to support EMI teachers and improve their instructional effectiveness in EMI teaching.

Literature review

Teaching STEM in EMI and translanguaging pedagogy

Using English in STEM subjects has been increasingly popular worldwide (Wächter and Maiworm Citation2014). This trend is evident in China’s disciplinary representation in EMI research, with STEM subjects accounting for 73% of studies (Jablonkai and Hou Citation2021). Although STEM teachers generally exhibit positive attitudes towards EMI (Kuteeva and Airey Citation2014), research across contexts suggests significant challenges in implementing effective teaching. The studies highlight language-related issues stemming from the non-native English-speaking background of both lecturers and students (Doiz et al. Citation2012; Macaro Citation2018). A recent study in Turkey shows that STEM students encountered specific academic English-related challenges concerning reading and writing across vocabulary, syntax and discourse levels, although to a lesser extent than students in social science disciplines (Kamaşak et al. Citation2021). These challenges can make EMI learning particularly difficult for students whose prior disciplinary knowledge has been established in their L1, like Chinese students. As Jiang et al. (Citation2019) argued, language-related difficulty facing EMI teachers is ‘particularly salient in mainland China’ (p. 2), especially in EMI programmes targeting only domestic Chinese students. Similar findings have emerged from recent research conducted in Europe and China (Hu and Duan Citation2019; Lasagabaster and Doiz Citation2023), indicating that EMI classes in STEM fields are no different from those in other disciplines, such as social science and humanities, in terms of the limited interactivity and simplified cognitive and linguistic teacher-student interaction.

In response to the language-related challenges, translanguaging, originally proposed to break down the boundary between languages in bilingual education (García and Li Citation2014), has been widely recommended as a possible pedagogical method in EMI. Translanguaging pedagogy is broadly known as ‘the instructional mobilization of students’ full linguistic repertoire and the promotion of productive contact across languages’ (Cummins Citation2019, p. 21). Research has distinguished spontaneous translanguaging pedagogies from planned translanguaging pedagogies, with the former involving the undesigned use of teachers’ and students’ linguistic and semiotic repertoires for learning and the latter requiring ‘systematic planning on the part of the teacher (and curriculum designers) and an intimate knowledge of the students’ multilingual linguistic resources’ (Lin Citation2020, p. 6). In EMI contexts where most students share their L1, researchers found that spontaneous translanguaging practice was an inherent part of the fabric of EMI teaching (Mazak and Carroll Citation2016). Moreover, in a Chinese EMI setting, Chen et al. (Citation2020) reported that STEM lecturers used planned translanguaging pedagogy strategies for different teaching goals; partial word-by-word and meaning translation was used to introduce new concepts and formulae to enhance students’ comprehension of content knowledge, while inter-sentential Chinese-English switching was used to develop affiliative bonds with students. Besides enhancing teaching quality, translanguaging has pedagogical value in facilitating classroom interactions, empowering students to recognise their local languages and identities, and promoting the plurality of knowledge systems (e.g. Gu and Lee Citation2019; Li Citation2022; Ou et al. Citation2022; Song Citation2023). Given the numerous benefits of translanguaging pedagogy, STEM education scholars have suggested EMI teachers actively and strategically utilise students’ L1 in teaching and develop their professional knowledge in planned translanguaging pedagogies (Rahman and Singh Citation2022).

However, implementing translanguaging pedagogy in EMI classrooms can be complicated when teachers must navigate various linguistic and cultural factors. Research in Chinese EMI settings has highlighted teachers’ divergent and discordant attitudes towards translanguaging (Wang Citation2019). Furthermore, a discrepancy often exists between teachers’ perceptions of translanguaging and their actual classroom language use. This can be attributed to political, institutional, and ideological influences (Fang and Liu Citation2020), a lack of guidance on translanguaging pedagogy (Yuan and Yang Citation2023), teachers’ linguistic purism ideology (Chang Citation2019), the assumed risks of students’ excessive use of L1 (Liu and Fang Citation2022), or combinations of or interactions between the above (Jia et al. Citation2023). These studies suggest that EMI teachers’ translanguaging practice is situated in a complex discourse system and mediated by multiple factors beyond one’s language proficiency.

Our review indicates that an increasing number of studies have investigated the various stakeholders’ language ideologies of translanguaging, identifying the beneficial impacts of translanguaging pedagogy on multilingual students’ learning. Nonetheless, a pressing need remains for further research to comprehensively capture the intricacies of translanguaging pedagogical practices in knowledge construction within EMI higher education classrooms (Gu et al. Citation2022). Moreover, it is crucial to explore how teacher identities influence translanguaging and how they are constructed and shaped in the process. Such research would shed light on developing professional identities among multilingual STEM teachers as they engage in meaning-making and knowledge construction across L1 and L2 of their students. It would also highlight teachers’ agency in employing translanguaging pedagogies strategically and suggest the professional training/support they require for different phases of knowledge building in EMI.

EMI teacher professional identity and translanguaging

According to Beijaard et al. (Citation2004), a teacher’s professional identity is ‘an ongoing process of integration of the ‘personal’ and the ‘professional’ sides of becoming and being a teacher’ (p. 113). Teachers’ professional identity – i.e. how they perceive and enact their professional roles in their daily work – can influence their beliefs about teaching and decision-making and their actual teaching practices (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009). Teachers’ professional identity is discursively constructed and negotiated in local sociocultural discourses, often presenting as a struggle because teachers must make sense of different, sometimes conflicting perspectives and expectations at work (Beijaard et al. Citation2004). The professional identities of university staff rarely stand alone but rather are built on other identities (i.e. teacher, researcher, academic and intellectual identities) and shaped by multiple contextual factors, such as contact with students and colleagues, staff development activities, and the larger institutional and sociocultural contexts of higher education (van Lankveld et al. Citation2017).

In EMI higher education, teachers’ professional identities and their translanguaging practices in classrooms, albeit not focally examined, were frequently reported and made relevant to the teachers’ language identities, i.e. being a multilingual, native, or non-native speaker of English (e.g. Inbar-Lourie and Donitsa-Schmidt Citation2020). EMI lecturers from China have been found to accentuate their non-native-English-speaker identities, ruling themselves out of language expert roles; for them, translanguaging is a pragmatic strategy because they prioritise subject-content knowledge construction over language in teaching (Jiang et al. Citation2019). Similar findings were reported by Block and Moncada-Comas (Citation2022), who pointed out that STEM lecturers’ disciplinary identities – i.e. their deep feelings of attachment to their respective academic disciplines – contributed to their reluctance to take responsibility for addressing students’ language development in EMI learning at a Spanish EMI university. Furthermore, Trent’s (Citation2017) study in Hong Kong indicated that some lecturers’ pragmatic use of translanguaging was shaped by a discourse of rationality in EMI’s wider sociocultural and institutional context. University assessment policies place a premium on academic staff engaging in research-related activities that best serve their career development needs, such as promotion and contract renewal, and therefore advocate minimising efforts to address students’ language development needs. Although some studies have portrayed EMI lecturers in China as reluctant to take act as language teachers and resorting to spontaneous translanguaging as a pragmatic approach (Dang et al. Citation2023), other studies have revealed that teachers activate their agency – i.e. their capacity to act and make teaching decisions based on their beliefs and identities (Biesta et al. Citation2015) – to implement translanguaging as a planned pedagogical strategy, integrating students’ L1 and L2 in classroom teaching to facilitate students’ content comprehension and language development (Xu and Ou Citation2022).

In sum, previous research has shown that EMI lecturers’ classroom teaching is affected by how they position themselves in relation to different languages, their fields of specialisation, their other professional roles, and university policies and management. This requires closely examining translanguaging pedagogy in its situated sociocultural contexts and investigating how individual, interpersonal, and institutional factors shape a teacher’s language use in the classroom. This study focuses on exploring the connection between STEM teachers’ professional identity and their translanguaging pedagogical practices in EMI classroom settings in China by addressing the following research questions:

How did the STEM lecturers develop their professional identities in EMI teaching?

How did the lecturers’ professional identities influence their use of translanguaging pedagogical practices in classrooms?

The study

A nexus analysis

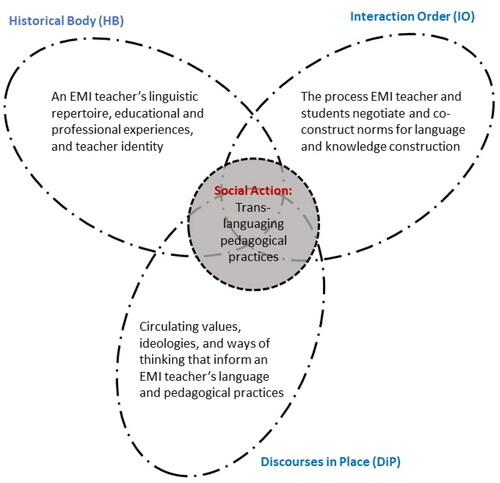

In this study, we employed nexus analysis as a ‘meta-methodology’ (Hult Citation2017) to integrate complementary data collection and analysis methods to examine the interaction of STEM teachers’ professional identity and their translanguaging pedagogies in EMI classrooms. At its core, nexus analysis is an ethnographic discourse analysis method in which discourse is understood as ‘different ways of thinking, acting, interacting, valuing, feeling, believing, and using symbols, tools, and objects’ (Gee Citation1999, p. 13). It examines a social action – an individual’s meaning-making behaviour in its social context (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004) – by addressing the connection between two levels of discourses: ‘the micro-analysis of unfolding moments of social interaction’ and ‘a much broader socio-political-cultural analysis of the relationships among social groups and power interests in the society’ (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004, p. 8). In this study, EMI teachers’ translanguaging pedagogical practice is the focal social action that is studied through the following three inter-related types of discourses:

Discourse in place (DiP): The material and ideological phenomena that reflect the circulating values and beliefs that exist at the moment of EMI classroom teaching and that influence the teacher’s language and pedagogical practices (Hult Citation2017);

Interaction order (IO): The immediate interpersonal and interactional cycle of discourse that involves all ‘possible social arrangements by which we form relationships’ (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004, p. 13), such as the shared norms co-constructed/negotiated by EMI teachers and students for interaction and knowledge construction.

Historical body (HB): The embodiment of individuals’ life history and experience (Hult Citation2017), especially language repertoires and beliefs and identities, which shape the way EMI teachers perceive teaching and interact with students.

Informed by nexus analysis (), our study examines the translanguaging practice in STEM-EMI classrooms enacted by individual teachers as the ‘nexus of practice’ (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004, p. viii), shaped by the relationships and interactions between different EMI stakeholders’ actions and beliefs (i.e. teachers, students, administrators, and policymakers). This method highlights teacher identity as an important component of a teacher’s historical body (HB), which intertwines with the teacher’s life experiences and other discourses from the immediate and structural contexts of EMI teaching to impact the pattern and effect of the teacher’s classroom practice.

Research site and data collection

The study is part of a larger linguistic ethnography project conducted in an interdisciplinary STEM institute at a top-tier university in Southeast China. The instituteFootnote1 provides four undergraduate-level programmes, three master’s programmes, and one doctoral programme in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biological sciences; all are taught in English. The institute enrols about 60 undergraduate students, 60 postgraduate students, and 60 doctoral students every year. Most of the student body comes from China, though the postgraduate programmes are open to international students. The faculty members (n = 40) are mainly of Chinese ethnicity, but all obtained postgraduate degrees overseas, primarily in English-speaking countries. The institute implements a flexible EMI policy, namely ‘English-based bilingual teaching’ in the policy text, leaving space for faculty members to reinterpret and translate the policy into individualised translanguaging pedagogical strategies (vide infra). Students and teachers at the institute agree, however, that all textbooks, learning materials, and assessments must be in English, while teachers have autonomy in choosing the language used in lectures and classroom interactions.

Data collection was conducted in the 2021 spring semester. Using purposive and snowball sampling, we recruited four focal teachers from different disciplines with different educational backgrounds and teaching experiences. The study involved class observations, interviews with participants, and informal interviews with other teachers and researchers from the institute to gain a comprehensive understanding of the institute’s EMI policy, common values, and teaching practices. For this nexus analysis, we re-organised classroom observations, field notes, policy texts, and teacher interviews to provide insights into the HB, IO, and DiP cycles of discourses of translanguaging pedagogy in EMI. To better illustrate the intersection of multi-dimensional discourses, especially the impacts from the HB and IO cycles, we focused on the experiences of two teachers – Ye and Ming (pseudonyms) – who shared sufficient similarities in their backgrounds (): both were Chinese-English bilinguals who spoke English as a second language and identified as proficient users of English in their professional contexts. In addition, both were assistant professors with the same required duties regarding their research engagement and teaching activities (two undergraduate-level courses per semester) at the time of the data collection.

Table 1. The focal EMI teacher participants.

Data analysis

Data analysis was informed by the collected ethnographic observation and interview data and the nexus analysis framework. Specifically, to examine the dominated DiPs and how they were made relevant by teachers in EMI classrooms, we drew on incorporated critical discourse analysis (Johnson Citation2011) of the institute’s language policy texts (in both English and Chinese, with two pages in each language) and thematic analysis of interviews, including formal semi-structured interviews with the two focal teachers and formal or informal interviews with other teachers (documented in field notes). The analysis identified the dominant ideologies and assumptions embedded in the institute’s EMI policy texts. Moreover, we examined the recontextualisation process of policy from policy texts to local classroom activities, which ‘transforms the meaning of a text by either expanding upon or adding to the meaning potential or, perhaps, suppressing and filtering particular meanings’ (Johnson Citation2011, p. 270).

Interactional analysis (Scollon and Scollon Citation2004) of class observations provided insights into the IO cycle. Amy observed two continuous classes (90 min) taught by each focal teacher during the regular instructional period in the middle of the semester. Ye was observed in his material characterisation course (class size = 9), and Ming was observed in her analytical chemistry course (class size = 38). All classes were recorded with a video camera; field notes were taken. To understand the IO, we coded the teachers’ verbal and non-verbal behaviours and interaction patterns with students. Special attention was paid to instances when shared norms of interpretation occurred between the teacher and students to guide their language use and methods of knowledge construction.

After the observations, both teachers received a semi-structured interview, each lasting about one hour, wherein they elaborated on the specific language and teaching methods they employed in the observed classes, discussed their experiences and perceptions of EMI teaching, the teaching effects, and how they positioned themselves to different professional roles, i.e. teaching, research, and administration. Both interviews were conducted in Mandarin Chinese – the teachers’ first language – and were audio-recorded and then transcribed by an independent researcher. The examination of the HB cycle was mainly facilitated by thematic analysis of the interviews, by which we identified the recurring patterns related to the teachers’ language ideologies and professional identities, such as beliefs about language and content teaching, teaching and research experiences, and interactions with students.

Once the three discourse cycles were identified and analysed, we mapped the three-tier discursive relationships (). During this phase, we focused on exploring the formation and utilisation of pertinent discourses across various scales (i.e. institutional, interpersonal, and individual) of EMI education. We examined how individual teachers employed these discourses in their classroom teaching and analysed how their interplay influenced the construction of teachers’ professional identities and meaning-making processes as they engaged in pedagogical translanguaging practices in classroom teaching.

Findings

The discourses of internationalism and research meritocracy

First, our analysis identified two prevailing DiPs within the institute: ‘the discourse of internationalism’ and ‘the discourse of research meritocracy’. These DiPs were frequently evoked by the teachers, albeit to varying degrees, to inform their linguistic choices in classroom interactions and pedagogical approaches towards EMI teaching.

The discourse of internationalism addresses how the role of English in EMI was conceptualised in the institute’s language policy and by its teaching staff. The analysis shows a consistent understanding of the value of English manifested in the policy text and among the lecturers. That is, English has been promoted in terms of the rhetoric of internationalism, a symbol of the university’s internationalisation. For example, the institute’s official webpage notes:

The institute adopts an English-based bilingual teaching mode and provides a large number of international exchange opportunities for students…. 60% of 2019 undergraduates went to overseas universities to continue their studies, …. Many students were accepted by Oxford University, UC Berkeley, Columbia University, University of Pennsylvania, Brown University, Johns Hopkins University, University College London and other world-renowned schools.

Jerry: I was told that the university sought so-called ‘internationalisation’. So obviously, English teaching is quite important. However, if they realise that the students’ language proficiency is not good, they should provide more English courses.

Ye: Teaching in Chinese is definitely more effective for students. After all, their ways of thinking and knowledge foundations were all developed in Chinese. However, the purpose of using English to teach is, we hope, to benefit them in their future studies and research abroad.

Another DiP that greatly impacts how teachers develop pedagogical strategies and regulate their language use in classrooms is the discourse of research meritocracy, referring to institutional values prioritising research over teaching. The teachers in this study believed that the university’s staff assessment system placed more value on research outputs than teaching. Jerry commented that the university sends mixed messages about staff performance evaluation:

Jerry: Even though they claim they will evaluate a particular person on teaching, research, and administration. In reality, only on research. If they want to get rid of you, they will pay attention to your teaching.

Ye: ‘research has taken up a lot of time’

Ye translanguaged in his classes by using English as the primary language for communicating with students and Chinese for translating the instructed technical terminologies. In his embodied teaching, Ye actively engaged with multimodal resources in the classroom, such as diagrams, charts, drawing, circling and gestures in teaching. The following excerpt demonstrates a typical moment of Ye’s lecturing:

Excerpt 1

Table

In the above extract, Ye elucidated the concept of Rayleigh Criteria to the students. Upon introducing the term, he promptly provided its Chinese translation, then elaborated on the knowledge point exclusively in English, employing a deliberate pace and incorporating frequent pauses within each sentence to facilitate students’ comprehension. It is noteworthy that Ye’s spoken English during the instruction was not flawless; he frequently utilised simplified and ungrammatical sentence structures and consistently mispronounced ‘criteria’ as ‘cri-rium’ until he redirected his attention towards the whiteboard, where the word was displayed, and encircled it. Nevertheless, his seamless utilisation of body movement in instruction, such as gestures and interaction with the projected slides on the whiteboard, helped students visualise his thoughts. Through translanguaging practice, Ye made his teaching an embodied activity of largely meaningful instruction.

However, as demonstrated above, Ye’s translanguaging emerged unintentionally, spontaneously, and seamlessly during his lectures; his use of the students’ L1 Chinese was minimal and solely employed for offering translations of certain thematic concepts. Remarkably, Ye remained oblivious to his employment of translanguaging as a valid teaching strategy in EMI contexts. When asked about his language use for classroom teaching, he responded paradoxically:

Ye: English only. But if there are English words they don’t understand, I just explain the meaning in Chinese.”

Ye: When our institute was initially set up, it expected us to deliver instruction solely in English. However, considering that not all students feel at ease with English-only instruction, we now allow English-Chinese bilingual teaching. In practice, it’s up to individual teachers to decide whether to use English only or use Chinese.

In the interview, Ye acknowledged and reflected on his monologic lecturing and yet-to-improve teaching effect:

Researcher: How do you evaluate your own EMI teaching ability?

Ye: Well, after all, English is not my mother tongue, so I need to practice more. But most of the time it’s fine, maybe because the science discipline does not require that much English proficiency from teachers.… This group of students are not very interactive in class, they usually didn’t initiate questions when I was teaching.… The curriculum is heavy as well. So now my class leaves no time for group discussion or student presentation. It is basically only lecturing.

Researcher: Then how about the students’ learning effect?

Ye: It’s so-so, not very good. The students’ learning abilities and motivations vary a lot…. Also, the learning materials are only in English. So some students are doing well, and some find it difficult to cope with learning.

Ye: Of course, I hope I can receive a better evaluation from students and teach better, yet I have not found any good method. Also, research has taken up a lot of time.

Researcher: How do you allocate your time for research and teaching?

Ye: Taking this semester as an example, I use yesterday afternoon, this afternoon, and nights for teaching, preparing for lectures, delivering lectures, and examining homework. Usually, teaching takes two days a week, and the rest five days of the week are all for research.

The DiP of research meritocracy and Ye’s strong researcher identity also contributed to his English-dominated language use in the classroom:

Ye: My course contents are all related to my research, so the process of updating teaching materials is also a self-study process for me. Furthermore, EMI teaching allows me to practice my spoken English. This benefits my academic English writing, and my ability to make English presentations at academic conferences.

In summary, Ye employed a spontaneous translanguaging pedagogy characterised by an organic blend of English, Chinese, and multimodal resources, with English playing a dominant role. As depicted in , Ye’s pedagogical approach was shaped by the intersection of various discourses operating at multiple levels within the examined EMI institute, particularly in terms of how Ye constructed his professional identities in relation to the institution’s teaching and research values. Specifically, the influence of the English-monolingualism ideology, driven by the discourse of internationalism, and the prominence of the researcher identity, prompted by the discourse of research meritocracy that emphasizes research performance in faculty evaluation, played significant roles in shaping Ye’s decision to prioritise English language in the classroom. This decision was pragmatic and unadvised, leading to a teacher-centred, monologic, and non-interactive instructional environment that impeded students’ learning effectiveness.

Ming: ‘communicating with students is my major source of the sense of achievement as a teacher’

Ming developed a different classroom language strategy despite having a language and education background similar to Ye’s. In Ming’s class, Chinese was a verbal resource she and her students frequently used. Ming proactively initiated teacher-student interactions, and students tended to adopt the language in which she asked questions when responding. The following dialogue exemplifies how knowledge was co-constructed between the teacher and students through dialogic translanguaging (Nikula et al. Citation2013):

Excerpt 2

In this dialogue, Ming first asked a question in English (mainly) (turn 1), and the students responded in the same language. We can understand the use of ‘還是’(or) as a marker to raise the students’ awareness of the concepts of ‘precision’ and ‘accuracy.’ In turns 3–4, Ming provided a bilingual explanation for a critical part and then used English for additional explanation (turn 5). She followed the flow and raised a question in English to check students’ understanding in turn 6. In the subsequent explanation (turns 8–9), instead of solely repeating her English utterances in Chinese, Ming provided further elaboration in Chinese (turn 9).

As evident in this dialogue, Ming’s classroom exhibited a high level of interactivity, with the teacher’s and students’ active participation through translanguaging practices. Ming strategically employed a ‘fluid, flexible, and distributed’ (Lin and Lo Citation2017) utilisation of various registers of English and Chinese during the knowledge construction process. Specifically, L1 everyday language (e.g. 還是, 對吧), L1 academic language (e.g. 精密度, 顯著性), and English academic language (e.g. modification methods, equivalent precision) were used to facilitate knowledge co-construction. In addition, Ming skillfully responded to students’ contributions by elaborating or transitioning to new topics, extending or linking them to students’ personal experiences (Lin and Lo Citation2017).

Ming conventionally ended her classes by playing a short English lecture video () covering the academic content taught in the lecture, but voiced by a native-English-speaking academic. She explained:

Figure 3. Ming played a video about T-test (in English).

Footnote3Ming: I think the speaker’s English in the video is more standard than mine. The video is used to help [students] consolidate their newly-learnt knowledge and improve their English.

Ming adeptly incorporated this native-English and multimodal teaching resource as an integral component of her translanguaging pedagogy. In this approach, the video served as a language expert in EMI teaching, enhancing students’ English proficiency through ‘standard’ English input. This strategy was underpinned by the interplay between the institute’s DiP of internationalism, which advocates for EMI implementation regardless of students’ English proficiency, and Ming’s strong teacher identity, which strove to support students in content knowledge acquisition and English language development (HB). She perceived language teaching as essential to her teaching responsibilities while recognising her non-native English speaker language identity and lack of professional training in academic English literacy (suggested in the subsequent interview).

Ming’s interview revealed that her translanguaging in classrooms was a planned pedagogy (Lin Citation2020), shaped by her continuous self-reflection on the past three years of teaching experiences and influenced by ongoing negotiations surrounding the institute’s language policy:

Researcher: How did you decide on your language strategy?

Ming: This is the third year I have taught this course. In the first year, I used 50% English and 50% Chinese in teaching. In the second year, I used 100% English, no Chinese at all. Then I found the second year’s students demonstrated worse mastery of the knowledge. The difficulty of the exams was almost the same. So, I think the English-only teaching method could make it difficult for students to learn.

Researcher: Why half-English-half-Chinese teaching in the first year? Is this the institute’s requirement?

Ming: Our institute requires “English-based bilingual teaching, " so I only taught my first lecture in English. But the students responded that they could not understand. So I switched to half-and-half upon the students’ request.

Researcher: Then why did you switch back to 100% English the next year?

Ming: That was decided by the department head. The institute used to let us decide our classroom language, depending on our students’ situations. To my knowledge, most teachers preferred speaking more Chinese, but they also found that the students had problems with English proficiency. So, our department head suggested we should not make the concessions the students requested. We should “push them, train them (to learn in English), but not compromise,” she said. She believes learning in English is beneficial for them to study abroad in the future.

Ming’s agency in language policy negotiation is closely associated with her professional identity (HB), which highlights a pursuit of balance between teaching and research. Unlike Ye, who showed reluctance to improve teaching, Ming was keen on improving her translanguaging pedagogy to better cater to students’ learning needs. When asked what motivated her to explore different pedagogical methods, Ming responded:

Ming: To me, teaching and research are equally important. Because I enjoy teaching very much. I think communicating with students is the primary source of my sense of achievement as a teacher, even though I must acknowledge that the university’s staff assessment is more geared towards research.

As illustrated in , with a robust teacher identity and a flexible language ideology when implementing EMI teaching, Ming explored a planned translanguaging pedagogy in response to students’ learning needs. In contrast to Ye, Ming prioritised her professional identity as an EMI teacher – a combination of disciplinary teacher and language teacher – and demonstrated considerable agency in navigating the discourses imposed by the institution and transforming her classroom into a dialogic translanguaging environment. In her class, the students’ L1 was valued and strategically employed to support knowledge construction and online English media was recontextualised to facilitate English language development.

Discussion and concluding remarks

This study has explored the implementation of translanguaging pedagogy by STEM teachers in EMI classrooms and addressed how the teachers’ professional identities can influence their language strategies in classrooms and the teaching effects. The findings, in line with prior research (e.g. Wang Citation2019), indicate the presence of divergent language ideologies (monoglot or flexibly multilingual) among the teachers regarding EMI teaching, which correspond to their respective language approaches (unplanned or planned translanguaging) in classroom instruction. Using nexus analysis, our investigation has focused on the intricate web of discourses surrounding how the teachers developed different ideologies and beliefs and utilised their linguistic repertoires in teaching. The findings reveal that teachers’ translanguaging pedagogy is intricately embedded and shaped by a dynamic social-discursive system, in which the discourses of internationalism and research meritocracy prevailing in their institution and the teachers’ individual perceptions of and commitment to EMI teaching interact with each other to influence their teaching practices. This discursive intersection highlights the impact of individual academic staff’s teacher identity and agency on their engagement with institutional and classroom discourses. When the university prioritised scholarly achievements over teaching quality, a planned and interactive translanguaging pedagogy could only thrive when teachers possess a strong teacher identity that drives them to address students’ learning needs, like Ming. In such cases, the teachers are empowered to act as local EMI policymakers who can reshape EMI classroom communication norms to create a supportive learning environment for students’ knowledge construction and language development. Conversely, absent a strong teacher identity, academics may resort to a spontaneous and pragmatic approach to EMI teaching, embracing unplanned translanguaging practices that alleviate their teaching responsibilities and allow more time for research outputs.

The professional identity of the investigated EMI teachers reifies a site of struggle (Beijaard et al. Citation2004). However, unlike the anticipated conflicting identities associated with their disciplinary expertise and English language competence (e.g. Jiang et al. Citation2019; Block and Moncada-Comas Citation2022), participants in this study encountered a more systematic identity challenge – the competition between their professional roles as good EMI teachers and successful researchers – that was deeply embedded in the academic staff management system of the examined institution. This identity dilemma problematises an unspoken discourse of research meritocracy bred in the contemporary higher education system, which seeks to foster world-class universities but exacerbates academic pressures on scholars and devalues teaching-related activities (Tian and Lu Citation2017). This discourse demotivates faculty members from investing in their teacher identity and improving pedagogical skills. For example, Ye’s desire to develop a good EMI teacher identity was greatly hampered by the lack of time for teaching preparation and institutional support for pedagogical knowledge. This reminds us that the call for more planned translanguaging pedagogy in EMI (e.g. Lin Citation2020) ought to go hand-in-hand with constructing robust university staff performance evaluation systems that treat research and teaching equally. Establishing a more balanced view of academic staff’s research merits and teaching achievements will also facilitate the mutual informing process between research and teaching.

Our analysis reveals that the institution-level discourse of internationalism could hinder teachers’ identity formation and exercise of teacher agency in EMI teaching. Driven by this discourse, which mainly associates English with its extrinsic and symbolic value in internationalising the institution profile, university administrators (and policymakers) perceived translanguaging as problematic and promoted a monoglot approach to EMI teaching. This finding aligns with similar observations in other EMI contexts (e.g. Mortensen Citation2014), where monolingual-English EMI policies often contradict multilingual teachers’ and students’ ‘translanguaging instinct’ (Li Citation2018) and their flexible language use for teaching and learning. Due to the inherent power imbalance between EMI teachers and administrators, teachers are often constrained (as observed in Ming’s case) in their exploration and development of translanguaging pedagogy based on their own teaching beliefs. This constraint risks undermining the cultivation and preservation of EMI teacher identity, which is already precarious due to its competing relationship with the institution-imposed researcher identity.

It is important to note that the findings in no way present Ming as a model translanguaging pedagogy executor. While commendable, her exploration of planned translanguaging pedagogy proceeded as a self-motivated process without professional guidance. Moreover, Ming acknowledged her challenges in effectively fostering students’ English language development due to a lack of academic English literacy teaching training. As Lasagabaster (Citation2022) pointed out, when universities strive to satisfy increased demand for international education through EMI, teachers must be provided sufficient and handy support to effectively deliver EMI education. The results of this study shed light on the importance of teacher identity construction as part of teacher training for EMI. Firstly, it is crucial that institutions acknowledge and appreciate faculty members’ teaching accomplishments on par with their research performance. To that end, the staff assessment mechanism should equally recognise teaching merits.

Concrete guidance and toolkits are also essential for STEM-EMI teachers to develop and strengthen their teacher identity. Specifically, universities should provide pre- and in-service teachers with opportunities to engage in reflective teaching practices, enabling them to deepen their understanding of their teaching beliefs, values, and language ideologies. They should move away from the monoglot and English speakerism view of EMI teaching, recognising the pedagogical value of students’ multilingual repertoires.

Additionally, drawing from Ming’s experience, EMI teachers need to adopt a self-reflective teaching approach, forester active interaction with students, and draw insights from cutting-edge pedagogical translanguaging theories and practices to develop effective translanguaging instructional strategies. In particular, if STEM teachers are expected to be academic English language educators, they should be equipped with the necessary disciplinary knowledge of academic literacy education and skills to integrate English education with content teaching. One possible method is to build a teacher-researcher partnership in content and language-integrated learning.

Lastly, developing teacher identity requires a collaborative effort to establish a more inclusive language policymaking system within the institution. Teachers should be encouraged to exercise their agency in negotiating language policy and creating supportive instructional environments, while faculty management members and policymakers should actively acknowledge and incorporate teachers’ perspectives, facilitating opportunities for knowledge-sharing and co-designing language policies.

The study has limitations. STEM-EMI teachers’ professional identities were examined mainly through the experience of two bilingual Chinese teachers with similar linguistic, sociocultural, and professional backgrounds. Despite the contrastive beliefs and practices revealed by the analysis, the study left no space for a more diverse EMI teaching faculty (such as Jerry, a native English-speaking teacher at the same institute in a non-research position). Future studies may explore how teachers with divergent backgrounds position themselves differently to EMI policy discourses and compare teachers’ positionings and teaching practices from different universities with different EMI policy discourses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The examined EMI department is anonymised and addressed as [the institute] in this article.

2 (.): brief pause.

3 This piece of data was published in another work (Gu and Ou forthcoming), but the analytical approach and arguments are completely different.

References

- Beauchamp C, Thomas L. 2009. Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb J Educ. 39(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

- Beijaard D, Meijer PC, Verloop N. 2004. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach Teach Educ. 20(2):107–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

- Biesta G, Priestley M, Robinson S. 2015. The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach Teach. 21(6):624–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Billot J. 2010. The imagined and the real: Identifying the tensions for academic identity. Higher Educ Res Dev. 29(6):709–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.487201

- Block D, Moncada-Comas B. 2022. English-medium instruction in higher education and the ELT gaze: STEM lecturers’ self-positioning as NOT English language teachers. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 25(2):401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1689917

- Chang S-Y. 2019. Beyond the English box: constructing and communicating knowledge through translingual practices in the higher education classroom. Engl Teach Learn. 43(1):23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-018-0014-4

- Chen H, Han J, Wright D. 2020. An investigation of lecturers’ teaching through English medium of instruction—a case of higher education in China. Sustainability. 12(10):4046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104046

- Cummins J. 2019. The emergence of translanguaging pedagogy: a dialogue between theory and practice. J Multilingual Educ Res. 9(13):19–36.

- Dang TKA, Bonar G, Yao J. 2023. Professional learning for educators teaching in English-medium-instruction in higher education: a systematic review. Teach Higher Educ. 28(4):840–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1863350

- Doiz A, Lasagabaster D, Sierra JM. 2012. English-medium instruction at universities: global challenges. Bristol (UK): Multilingual Matters.

- Fang F, Liu Y. 2020. ‘Using all English is not always meaningful’: stakeholders’ perspectives on the use of and attitudes towards translanguaging at a Chinese university. Lingua. 247:102959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102959

- García O, Li W. 2014. Translanguaging: language, bilingualism, and education. New York (NY): Palgrave.

- Gee JP. 1999. An introduction to discourse analysis: theory and method. London: Routledge.

- Gu MM, Lee JC-K. 2019. ‘They lost internationalization in pursuit of internationalization’: students’ language practices and identity construction in a cross-disciplinary EMI program in a university in China. High Educ. 78(3):389–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0342-2

- Gu MM, Lee JC-K, Jin T. 2022. A translanguaging and trans-semiotizing perspective on subject teachers’ linguistic and pedagogical practices in EMI programme. Appl Ling Rev. 0(0):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0036

- Gu MM, Ou AW. forthcoming. Trans-languaging and trans-knowledging practices among STEM teachers in EMI programmes in higher education. Appl Ling Rev.

- Holmes P, Fay R, Andrews J, Attia M. 2013. Researching multilingually: new theoretical and methodological directions. Int J Appl Ling. 23(3):285–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12038

- Hu G. 2009. The craze for English-medium education in China: driving forces and looming consequences. Engl Today. 25(4):47–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078409990472

- Hu G, Duan Y. 2019. Questioning and responding in the classroom: a cross-disciplinary study of the effects of instructional mediums in academic subjects at a Chinese university. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 22(3):303–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1493084

- Hu G, Lei J. 2014. English-medium instruction in Chinese higher education: a case study. High Educ. 67(5):551–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9661-5

- Hult FM. 2017. Nexus analysis as scalar ethnography for educational linguistics. In: M. Martin-Jones and D. Martin, editors. Researching multilingualism: critical and ethnographic perspectives. New York: Routledge; p. 89–105.

- Hult FM. 2018. Engaging pre-service English teachers with language policy. ELT J. 72(3):249–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx072

- Inbar-Lourie O, Donitsa-Schmidt S. 2020. EMI Lecturers in international universities: is a native/non-native English-speaking background relevant? Int J Biling Educ Biling. 23(3):301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1652558

- Jablonkai RR, Hou J. 2021. English medium of instruction in Chinese higher education: a systematic mapping review of empirical research. Appl Ling Rev. 0(0): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2021-0179

- Jia W, Fu X, Pun J. 2023. How do EMI lecturers’ translanguaging perceptions translate into their practice? A multi-case study of three Chinese tertiary EMI classes. Sustainability. 15(6):4895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064895

- Jiang L, Zhang LJ, May S. 2019. Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: teachers’ practices and perceptions, and students’ learning motivation and needs. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 22(2):107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231166

- Johnson DC. 2011. Critical discourse analysis and the ethnography of language policy. Crit Discourse Stud. 8(4):267–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2011.601636

- Kamaşak R, Sahan K, Rose H. 2021. Academic language-related challenges at an English-medium university. J Engl Acad Purposes. 49:100945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100945

- Kaplan R. 2001. Language teaching and language policy. Appl Lang Learn. 12(1):81–86.

- Kuteeva M, Airey J. 2014. Disciplinary differences in the use of English in higher education: reflections on recent language policy developments. High Educ. 67(5):533–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9660-6

- Lasagabaster D. 2022. Teacher preparedness for English-medium instruction. JEMI. 1(1):48–64. https://doi.org/10.1075/jemi.21011.las

- Lasagabaster D, Doiz A. 2021. Language use in English-medium instruction at university: international perspectives on teacher practice. New York: Routledge.

- Lasagabaster D, Doiz A. 2023. Classroom interaction in English-medium instruction: are there differences between disciplines? Lang Cult Curriculum. 36(3):310–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2022.2151615

- Li W. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl Ling. 39(1):9–30.

- Li W. 2022. Translanguaging as a political stance: implications for English language education. ELT J. 76(2):172–182.

- Lin AM. 2020. Introduction: translanguaging and translanguaging pedagogies. In: Vaish V, editor. Translanguaging in multilingual English classrooms: an Asian perspective and contexts. Singapore: Springer, p. 1–9.

- Lin AM, Lo YY. 2017. Trans/languaging and the triadic dialogue in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. Lang Educ. 31(1):26–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2016.1230125

- Liu Y, Fang F. 2022. Translanguaging theory and practice: how stakeholders perceive translanguaging as a practical theory of language. RELC J. 53(2):391–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220939222

- Macaro E. 2018. English medium instruction: content and language in policy and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mazak CM, Carroll KS. 2016. Translanguaging in higher education: beyond monolingual ideologies. Tonawanda (NY): Multilingual Matters.

- Mortensen J. 2014. Language policy from below: Language choice in student project groups in a multilingual university setting. J Multiling Multicultural. Dev. 35(4):425–442.

- Nikula T, Dalton-Puffer C, García AL. 2013. CLIL classroom discourse: research from Europe. JICB. 1(1):70–100. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.1.1.04nik

- Ou AW, Gu MM, Lee JC-K. 2022. Learning and communication in online international higher education in Hong Kong: ICT-mediated translanguaging competence and virtually translocal identity. J Multiling Multicultural Dev. 0(0): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.2021210

- Paulsrud B, Tian Z, Toth J. 2021. English-medium instruction and translanguaging. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Rahman MM, Singh MKM. 2022. English medium university STEM teachers’ and students’ ideologies in constructing content knowledge through translanguaging. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 25(7):2435–2453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1915950

- Scollon R, Scollon SW. 2004. Nexus analysis: discourse and the emerging internet. New York (NY): Routledge.

- Song Y. 2023. ‘Does Chinese philosophy count as philosophy?’: Decolonial awareness and practices in international English medium instruction programs. High Educ (Dordr). 85(2):437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00842-8

- Tian M, Lu G. 2017. What price the building of world-class universities? Academic pressure faced by young lecturers at a research-centered University in China. Teach Higher Educ. 22(8):957–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1319814

- Trent J. 2017. ‘Being a professor and doing EMI properly isn’t easy’. An identity-theoretic investigation of content teachers’ attitudes towards EMI at a university in Hong Kong. In: Fenton-Smith B, Humphreys P, Walkinshaw I, editors. English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific. Cham: Springer. p. 219–239.

- van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Volman M, Croiset G, Beishuizen J. 2017. Developing a teacher identity in the university context: A systematic review of the literature. Higher Educ Res Dev. 36(2):325–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1208154

- Wächter B, Maiworm F. 2014. English-taught programmes in European higher education. Bonn: Lemmens.

- Wang D. 2019. Translanguaging in Chinese foreign language classrooms: students and teachers’ attitudes and practices. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 22(2):138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231773

- Xu J, Ou AW. 2022. Facing rootlessness: language and identity construction in teaching and research practices among bilingual returnee scholars in China. J Lang Identity Educ. 0(0):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2022.2060228

- Yuan R, Yang M. 2023. Towards an understanding of translanguaging in EMI teacher education classrooms. Lang Teach Res. 27(4):884–906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820964123