Abstract

A key pedagogical goal in any classroom is to engage students in learning. This study examines how an English-Medium-Instruction (EMI) teacher employs available resources to engage his students in the classroom for promoting participation, keeping the lesson moving forward and meeting the pedagogical goals. The data for this study is based on a intensive fieldwork in an EMI secondary history classroom in Hong Kong. Multimodal Conversation Analysis is deployed to analyse the classroom interactional data. The classroom analysis is triangulated with the video-stimulated-recall-interviews that are analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. The study’s crucial theoretical contribution is that it broadens our comprehension of an EMI classroom as an integrated translanguaging space, which may involve various fluid and mobile translanguaging sub-spaces. This paper aims to illustrate the process of engaging students affords the teacher to create different translanguaging sub-spaces at a whole-class level and at an individual level. It is argued that creating these translanguaging sub-spaces requires the teacher to mobilise available resources for catering for the different needs of all students, which promotes interaction and inclusion in the classrooms.

1. Introduction

A key pedagogical goal in any classroom is to engage students in learning. There has been a growing number of studies that conduct research into language learner engagement (e.g. Mercer Citation2019; Mercer and Dörnyei Citation2020). The main lines of enquiry focus on investigating engagement with L2 (e.g. Svalberg Citation2018); engagement in task-based interaction (e.g. Philp and Duchesne Citation2016; Phung Citation2017; Dao et al. Citation2019) and positioning the concept of engagement within a broader theoretical framework (e.g. Lawson and Lawson Citation2013). The general finding is that when students are engaged in L2 classroom interactions, it is likely to result in greater learning outcomes (e.g. Storch Citation2008; Phung Citation2017). Therefore, L2 teachers are encouraged to engage the students in classroom learning through utilising various pedagogical strategies. These entail modelling (e.g. Kim and McDonough Citation2011); developing student’s awareness in deploying various communication strategies (e.g. Sato and Lyster Citation2012); training students to attend to the task features (e.g. Baralt et al. Citation2016) and designing motivating tasks (e.g. Maehr Citation1984; Lambert et al. Citation2017). Since teachers are often expected to purposefully engage their students in the classroom, it is vital to understand how L2 teachers construct their pedagogical practices for engaging the students in learning. Although the findings that are analysed here demonstrate what a teacher has done, not necessarily what teachers should be done, the findings offer a basis for explicating the choices that teachers make in their own classroom contexts. It can also bring to light a variety of strategies that teachers can potentially use in their respective classroom contexts. It is hoped that the research study can offer a useful extension to the existing work on EMI classroom interaction.

The notion of translanguaging celebrates the multilingual’s capabilities in drawing on their diverse and holistic multilingual, multimodal, multi-semiotic and multisensory resources for enabling the meaning-making processes (Li Citation2018). Recent studies (e.g. Sharma Citation2023) on translanguaging classroom practices have demonstrated how multilingual learners deploy cross-linguistic and cultural boundaries to generate new configurations of language and pedagogical practices in order to disrupt the hierarchy of languages, create a translanguaging space for learning and enable students’ full participation in knowledge construction. This paper aims to offer an alternative view of engaging students in learning by linking it to translanguaging and its emphasis on the mobilisation of multiple resources by the teacher in the under-explored research context, namely English-Medium-Instruction (EMI). EMI requires teachers to carry out their content teaching through the medium of English. It is a pedagogical policy and practice in countries and regions where English is not usually spoken by the majority of the population. A key theoretical contribution of the study is that it extends our understanding of an EMI classroom which can entail multiple translanguaging sub-spaces which are fluid and mobile. This study investigates how an EMI teacher creates translanguaging sub-spaces at a whole class level and at an individual level respectively to engage students in learning the content knowledge and cater to different students’ learning needs in the EMI history classroom in a secondary school in Hong Kong (HK). The study is a two-month intensive classroom observation which involves the researchers collecting classroom video recordings and video-stimulated-recall-interview data with the participating teacher. The classroom interactional data is analysed using Multimodal Conversation Analysis (MCA). The analyses of the classroom interactional data are triangulated with the video-stimulated-recall-interview data which are analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA).

2. Engaging students in classroom learning

The notion of engagement has been well-explored in language education. It has been conceptualised by researchers in different ways since it is a multi-dimensional construct that entails different components. In the context of L2 interaction, student engagement is often defined as ‘a state of heightened attention and involvement, in which participation is reflected not only in the cognitive dimension, but in social, behavioural and affective dimensions’ (Philp and Duchesne Citation2016, p. 51). Behavioural engagement refers to the student’s attention and effort which is often measured by time on task or participation (Philp and Duchesne Citation2016). In SLA research, the measurement of behavioural engagement entails counting the number of words, number of turns and the amount of time on tasks (e.g. Phung Citation2017). Cognitive engagement is concerned with the student’s attention and alertness (Helme and Clarke Citation2001). This is assessed through analysing language-related episodes (i.e. discussion of linguistic forms), negotiation of meaning, exploratory talk (i.e. talk that is used to challenge, accept and expand arguments, see Mercer Citation1995), self-corrections and idea units (e.g. the amount of ideas). Emotional engagement involves the student’s display of emotions and affective responses to the tasks. According to Reeve (Citation2012), students’ interests and willingness to participate in tasks are examples of task-facilitating emotions, whereas students’ negative attitudes or anxiety towards the task demonstrate their task-withdrawing emotions. Hence, emotional engagement can function as a filter for the student’s behavioural and cognitive engagement in using L2 while completing tasks (Baralt et al. Citation2016). Emotional engagement can be identified through self-report data, such as stimulated-recall interviews, and discourse analysis of the students’ interactions (Mercer Citation2015). Finally, social engagement refers to the social dimension of interaction and it highlights how students interact with their interlocutors (Storch Citation2001). These interactional behaviours can be tracked through analysing the student’s interactions, as reflected in the student’s mutuality, their willingness to interact with peers, and provide scaffolding and assistance to their peers during the interaction. In recent years, Conversation Analysis (CA) researchers suggest that engagement is observable, and they can be examined through the detailed analysis of social interaction (Sandlund and Greer Citation2020). Features including backchannels, moments of offering peer assistance, and equally distributed turns are examples of measuring social engagement. It can be argued that social engagement is closely related to emotional engagement since the relationship between peers can influence how students feel about a specific task (Baralt et al. Citation2016).

Recent classroom interaction research has investigated how teachers engage students in completing classroom tasks. Using CA as a methodology, Waring and Hruska (Citation2011) document the interactional strategies of how a novice ESOL student teacher manages student resistance in interaction and keeps the lesson moving forward. The CA findings reveal that the student teacher attempts to negotiate with the student through aligning with the student’s world, maximising opportunities for student participation and mitigating any possible opposition between herself and the student. These findings echo Walsh’s (Citation2002) work on teacher talk which promotes student involvement. This includes interactional features, such as wait time, scaffolding and content feedback, for engaging student participation in a task. Lin and Wu (Citation2015) study conducts a fine-grained analysis of the EMI secondary science classroom interaction in order to explore the interactional resources that the teacher has employed to invite students to construct meaning and display their understanding in the interaction. Based on the analysis of a five-minute interaction, the findings indicate that when the teacher grants permission to students with low English proficiency levels to answer the teacher’s questions in L1 Cantonese, this creates an opportunity for the students to fully involve in the class discussions, as evidenced by the extended elaborations of their responses in Cantonese. This reveals that the teacher’s agency in resisting monolingual ideology in EMI policy engages students in learning new scientific knowledge and resolves the students’ struggle in exhibiting their scientific understanding in L2 English.

The studies highlight how teachers use interaction to engage students in real-time classroom interaction through analysing the micro-details of the talk. Prior research has emphasised that multimodal features, including gestures, and paralinguistic features, such as intonations, can be as important as linguistic resources for teachers to utilise for engaging students in undertaking classroom activities (e.g. Li and Ho Citation2018; Ho and Li Citation2019). This paper examines the EMI teacher’s actions in promoting student engagement through maintaining student attention to the lesson content and maximising opportunities for student participation.

3. Medium-of-instruction policy in Hong Kong

Medium-of-instruction has been a heated issue in HK amid the political, economic and social concerns that happened over the past five decades (Poon Citation2009). Over 90% of the population in HK is ethnic Chinese, with Cantonese as their language for everyday communication and standard written Chinese as their written language. Most of the primary schools in HK adopt Chinese-Medium-Instruction (CMI) for most content subjects and English is taught as a separate core subject (Poon Citation2010). There are various reasons for universities in HK to use EMI, including the need to align with international tertiary education, attract more international students and strengthen their competitive edge (e.g. Evans Citation2002). Whilst the medium-of-instruction policies are broadly set for primary and university education, medium-of-instruction policy at the secondary level has gone through immense changes (Poon Citation2010). HK’s secondary schools have witnessed three key stages in the development with regard to medium-of-instruction policies, including (1) the laissez-faire policy prior to 1994; (2) the compulsory CMI policy during 1998-2010 which allowed 114 secondary schools to use EMI to teach content subjects while the remaining 307 schools were mandated to use CMI; and (3) the fine-tuning medium-of-instruction policy since 2010. The policy is in part responding to the parental desire for their children to be educated in EMI settings. Under the fine-tuning policy, it has resulted in a diversified mode of medium-of-instruction in schools. This includes CMI in nearly all subjects for all secondary levels, medium-of-instruction switching (i.e. CMI/EMI in different subjects in different grade levels), or EMI in nearly all content subjects for all grade levels.

Research studies (e.g. Chan Citation2013, Citation2014; Poon et al. Citation2013) have demonstrated that the fine-tuning medium-of-instruction policy has its limitations. Although the government has provided specific criteria for schools to provide EMI classes, placing students into EMI classes does not mean that learning will take place in the classrooms automatically (Chan Citation2013, Citation2014). It is important for the government to pay attention to how the policy is implemented in the local level in order to resolve the difficulties that are currently faced by teachers and students in teaching and learning through EMI. This includes developing appropriate teaching and learning strategies in EMI classrooms and deciding the amount of professional and practical support that should be provided to schools and teachers.

4. Translanguaging as an inclusive pedagogical resource for student engagement

The term ‘inclusive education’ has different meanings in different contexts. In the UK, it is often associated with special needs schools (Spurgeon Citation2007), but in other contexts, such as school attendance or discipline, it has different meanings (Slee Citation2004). Slee (Citation2004) argues that there is conceptual confusion over the issue, but it may necessarily have different meanings depending on the context. Ainscow et al. (Citation2006) have developed a framework of six ways of thinking about inclusion, which includes principles like education and society, disabled students, and special educational needs. In essence, inclusion is fundamentally about promoting social justice and fighting exclusion in schools and communities (Salend and Garrick-Duhaney Citation1999). Researchers have studied the impact of inclusive arrangements on students’ learning experiences, and it has been found that adopting the practice of inclusion in classrooms can improve academic achievement, increase peer acceptance, and higher self-esteem (Salend and Garrick-Duhaney Citation1999; Averill Citation2012; Chan and Lo Citation2017; Roos Citation2019).

In this study, inclusion is understood more broadly as a philosophy emphasizing acceptance and respect towards all individuals. The notion of participation is a central idea in inclusive pedagogy and it reinforces the role of the teacher’s pedagogical practices in supporting all students’ learning processes. Trussler and Robinson (Citation2015) conceptualize two main inclusive practices, namely the individual and whole-class approaches, for addressing the various needs of all students to promote their learning processes. The individual approach focuses on how students with specific learning difficulties can perform successfully in the context of whole-class teaching. This may entail preparing differently graded tasks and giving them out to different students on various levels. This can mitigate the possible stigma of ‘requiring extra assistance’ or ‘doing easy work’. Alternatively, the whole-class approach involves the teacher designing the learning experience for everyone, not only those who are in need. In other words, when teachers are planning classroom activities or tasks, they need to have all students in mind instead of focusing on the majority or the minority. By doing so, this makes learning accessible to every student in the class.

The Welsh-inspired term translanguaging was coined to describe a pedagogical practice of switching between different input and output languages in bilingual classrooms (Williams Citation1994). Li (Citation2018) further shapes the concept of translanguaging as a process of knowledge construction which involves going beyond different linguistic structures and systems (i.e. not only different languages and dialects, but also styles, registers and other variations in language use) and different modalities (e.g. switching between speaking and writing, or coordinating gestures, body movements, facial expressions, visual images). Emphasizing the transformative nature of translanguaging practices, Li (Citation2011, Citation2018) proposes the notion of ‘translanguaging space’ where multiple multilingual, multimodal and multi-sensory repertoires interact and co-produce new meanings. The notion of translanguaging space is different from other conceptualisations of language since translanguaging space aims to go beyond the boundaries between spatial and other semiotic resources since it views spatial positioning and display of objects as semiotic and socially meaningful.

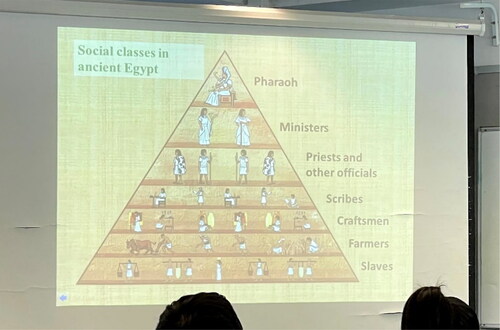

Image 1. Social classes in ancient Egypt. The graph illustrates the social pyramid of ancient Egypt.

The notion of translanguaging is associated with promoting equity and social justice in multilingual classrooms since it takes into account the teacher’s and students’ full repertoire for creating a translanguaging space for meaning-making. In the context of multilingual classrooms, the hierarchy of named languages often leads to the prioritization of one or more languages (usually the dominant or official languages of a given region or country) over other named languages spoken by students (Sah and Li Citation2022; Li Citation2023). This can marginalize students who speak minority languages or dialects and create an environment where their linguistic resources are undervalued and underutilized (Mendoza Citation2023). In order to teach for equity and social justice, teachers need to integrate the students’ available linguistic resources and diverse funds of knowledge into learning opportunities (Garcia and Li Citation2014; Tai and Li Citation2021; Tai Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). This can potentially provide a voice to students who are not given sufficient chance to employ their multilingual and multicultural resources due to the implementation of a monolingual policy in bi/multilingual classrooms. Therefore, translanguaging encourages classroom participants to utilise their diverse linguistic, multimodal and multicultural resources to challenge the hierarchy of named languages in the classrooms and enable students’ participation in creating new knowledge and new configurations of language practices.

To date, there are a number of EMI studies that have conceptualised translanguaging as a practice for facilitating equity and social justice in the classrooms (e.g. Sah and Li Citation2022). However, the intricacies of translanguaging pedagogy (Li Citation2018) and how EMI policy is talked-into-being in conversations (Bonacina-Pugh Citation2012) are under-explored in the literature. Specifically, does this inclusive pedagogy of translanguaging actually enhance students’ engagement in actual EMI classroom interaction, and how? In order to substantiate the argument of translanguaging as an inclusive pedagogy for engaging students in classroom learning, this paper aims to reveal how the EMI history teacher seeks out available multilingual and multimodal resources and make strategic choices among these resources to create different translanguaging spaces at the whole-class level and at the individual level in order to deepen students’ engagement and involvement in the classroom.

To date, the complexity of translanguaging space has not been adequately explored (Tai and Li Citation2020; Tai Citation2023b) and there is still a lack of comprehensive understanding of how a classroom as an integrated translanguaging space which can be separated into several translanguaging spaces for teachers to achieve different kinds of pedagogical goals. We argue that the division of “translanguaging space” (Li Citation2011) into different sub-spaces can help classroom interaction researchers to identify the nuances in the overarching construct of ‘translanguaging space’ and highlight the dynamic nature of translanguaging space (Tai and Li Citation2020; Tai Citation2023b). This perspective echoes Seedhouse’s (Citation2004) argument that classroom interaction is not an undifferentiated whole. Rather, it can be divided into a number of sub-varieties which includes form and accuracy contexts, meaning and fluency contexts, task-oriented contexts and procedural contexts (Seedhouse Citation2004). Previous studies on classroom interaction have narrowed their focus down to the studies of particular action types (e.g. Markee Citation1995; Morell Citation2007) and the particular interactional structures in the classrooms (e.g. Lee Citation2007). These studies portray teachers as constructing one pedagogical action on one level at a time. Seedhouse (Citation2004) demonstrates that L2 teachers may be simultaneously orienting to multiple separate pedagogical goals and that classroom interaction may be operating simultaneously on multiple levels. Analysing classroom interactional features, therefore, needs to take into account the context in which the features are operating and avoid acontextual overgeneralizations. It can be argued that a classroom should not be seen as a single translanguaging space that is static and invariant. On the contrary, a classroom is an integrated translanguaging space which consists of multiple translanguaging sub-spaces that afford teachers to draw on particular resources in a coordinated performance to achieve their pedagogical goals at specific moments in the lessons. In this study, we build on Li’s (Citation2011) notion of “translanguaging space” and we aim to reveal the process by which an EMI teacher establishes different translanguaging sub-spaces in an EMI history classroom. These sub-spaces are created both at the whole class level and at an individual level, with the aim of facilitating student engagement with the content knowledge and addressing the diverse learning needs of students.

5. Methodology

The secondary school is a prestigious EMI secondary school in the New Territories, and it is the first EMI school in the local district. The school is a typical local EMI secondary school, which provides education from year 7 to twelve based on the curriculum guides set by the HK Education Bureau. The school uses English to deliver most of the lessons (except Chinese, liberal studies and Mandarin classes), and the school examinations are assessed in English. Although the school’s mission statement is explicit that it aims to develop students to be bi/multilinguals, the school language policy places heavy emphasis on the use of English on the school campus which aims to create a rich and strong English learning environment for all students. All morning assemblies and staff meetings are conducted in English. All teachers and students are explicitly informed that English has to be used during the content lessons. Moreover, English-for-all-day is held on every Monday when everyone (all teaching staff and students) in school must use English for communication. However, in practice, the actual implementation of English-for-all-day could vary as not all students are willing to speak English to their peers and teachers outside the classrooms. Chinese Week and Mandarin (Putonghua) Week are also held to promote Chinese language acquisition, but these events are only held annually. Hence, it can be seen that the school’s language policy is biased in favour of English over other named languages (Cantonese and Mandarin in this case) and is not designed to support students’ multilingualism.

The history teacher, who agreed to participate in this study, has taught for more than twenty-one years at the participating school and he serves as Head of History and Head of Guidance and Special Educational Needs (SEN) at the school. He is a native speaker of Cantonese and he can speak fluent English. He has a limited level of Mandarin/Putonghua and Japanese proficiency. He attended an EMI school for his own secondary education. He majored in History and minored in Chinese Language and Literature and Japanese Studies during his undergraduate studies. His bachelor’s degree and postgraduate diploma of education were obtained at a prestigious EMI university in HK. He is qualified to teach Chinese language, Chinese history and western history. He often attended professional development programmes offered by the Education Bureau in order to enhance his knowledge of history pedagogy and SEN. Before coming a teacher, he worked as an editor for a publisher and a research assistant at an EMI university in HK.

A one-hour semi-structured interview was conducted with the teacher before classroom observation in order to understand the teacher’s perceptions of his attitudes towards using multiple languages in the EMI history classrooms. The first author carried out classroom observation in the year 7 history class for two months from October to November 2020, when face-to-face teaching was resumed after months of online teaching from January to June 2020. The year 7 class taught by the teacher had 30 students and according to the teacher, the students’ English proficiency was below average among their cohort in the internal English examination. Since the teacher taught all year 7 history classes, he noticed that the student’s general academic performance in this particular year 7 class was below average. These students have received at least 6 years of primary education, where Cantonese was employed as the Medium-of-instruction and English was taught as an L2. Eleven 30-minute lessons were observed and video-recorded. Informal interviews were carried out with the teacher and students during the observational period in order to obtain information regarding the observed lessons. A one-hour post-video-stimulated-recall-interview was conducted with the teacher in order to allow the researcher and the teacher to achieve a shared understanding of the roles of the teachers’ own translanguaging practices in the EMI history classroom.

5.1. Combining multimodal conversation analysis with interpretative phenomenological analysis

MCA is used as the methodology to analyse the video-recorded classroom interaction data. The classroom data were transcribed using Jefferson’s (Citation2004) and Mondada’s (Citation2018) transcription conventions. MCA adopts an emic/participant-relevant perspective in order to focus on ‘how social order is co-constructed by the members of a social group’ (Brouwer and Wagner Citation2004, p. 30) through conducting fine-grained analysis of the social interaction. MCA extends CA by incorporating multimodal actions, such as gaze, gestures and manipulations of objects, which the translanguaging perspective perceives multimodal actions as integral to social interaction as linguistic utterances. In our analysis, we also employ screenshots from the video recordings to illustrate multimodal interactions in the EMI classrooms.

For reporting purposes, we can only select the representative extracts rather than presenting all the transcribed interactional sequences. When identifying representative cases, the following aspects were considered:

The presented extracts are being directly or indirectly comparable to other extracts (ten Have Citation1990);

The deviant cases are being considered (Ford Citation2012).

As ten Have (Citation1990) argues, MCA analysis ‘is always comparative, either directly or indirectly’ (ten Have Citation1990, p. 34). In other words, the analysed extracts are inter-related to illustrate how the interactional features recurrently occurred (by relevantly similar instances) or how the features are employed in dissimilar ways (by deviant instances). In this study, the chosen extracts are typical instances of translanguaging practices in the EMI history classroom. The aim of doing MCA analysis is to find the ‘devices’, or ‘the technology of conversation’ in the speakers’ situated interaction, instead of justifying the best possible representative extracts (ten Have Citation1990). Hence, as long as the selected extracts can address the research questions to reveal the relevant interactional phenomenon with their representative nature, this can be said, to a large extent, that the representativeness is sufficient, or the research findings can be reliable.

In order to ensure that the MCA analysis is reliable and valid, the identified translanguaging practices are solidified by reiterative line-by-line analyses of the data at least two times to minimise the possibility of any subjective interpretations. Throughout the re-analysis process, we strived to maintain the ‘radically emic perspective’. We have also presented the MCA transcripts to CA Data Session at our university. These data sessions involved PhD students and academic staff from different universities whose research interests are situated in social interaction. Having other MCA analysts examining our data can bring a ‘fresh’ eye to the data and make sure that our analysis is not our own ‘interpretation’, but ‘sharable and shared understandings which can […] be analysed in procedural terms’ (ten Have Citation2007, p. 140).

We then triangulate the MCA findings with the video-stimulated-recall-interview data which is analysed using IPA. IPA allows us to understand how the teacher views his translanguaging practices at particular moments in the interactions. IPA follows a dual interpretation process called ‘double hermeneutic’. This requires researchers to try to make sense of the participants trying to make sense of their world (Smith et al. Citation2013). This allows analysts to take an emic approach to make sense of the teacher’s personal experience. Since MCA cannot reveal how participants bring various dimensions of personal history, beliefs etc to create the translanguaging spaces in the classrooms (Tai Citation2023b), using IPA to analyse the video-stimulated interviews allowed us to understand the teacher’s descriptions of his pedagogical practices and gather additional contextual information to inform the interpretations of our classroom analysis. In order to present the IPA analysis in a reader-friendly way, a table with four columns is designed in order to help readers to comprehend how the researcher makes sense of the EMI teacher attempting to make sense of his own teaching practices (see Appendix). From left to right, the first column includes the classroom interaction transcripts. The second column entails the video-stimulated-recall-interview excerpts. The third column demonstrates the teacher’s perspectives on his pedagogical practices at that moment of the classroom interaction. The last column records the researcher’s own interpretations of the teacher’s perspectives, which corresponds to IPA’s two-stage interpretation process (i.e. double hermeneutic). The double hermeneutic perspective can be evident in the form of interpretative statements, such as “it can be argued”, “may be understood as”, “may explain why”, and so on.

In order to ensure the validity of our IPA analysis, some security is offered by the detailed guidelines and discussion in relation to the interpretative process (e.g. Smith et al. Citation2013). IPA aims to provide evidence of how the participants make sense of phenomena under investigation and simultaneously document the researcher’s sense-making. Hence, this requires the researcher to move between emic and etic perspectives. Adopting an emic perspective allows the researcher to analyse the participants’ account of experience inductively. On the other hand, adopting an etic perspective requires the researcher to study the data through psychological perspectives and interpret it by applying psychological concepts or theories which the researcher finds useful in demonstrating the understanding of research problems. However, we were careful when applying external theories in interpreting participants’ experiences. When doing IPA analysis, we made sure that all the interpretations must be grounded in the interview data and this requires close attention to the interview data itself. As Smith et al. (Citation2013, p. 37) argue, a successful interpretation is one which is ‘based on a reading from within the terms of text which the participant has produced’.

5.2. Researchers’ positionality

The first author recognised that his role as a researcher could shape the research process in different ways, particularly when he was interviewing the EMI teacher, identifying translanguaging instances for analysis and interpreting the interactional data and video-stimulated-recall-interview data. His positionality as a researcher and his status as a former student of the participating school could have affected how he talked to the teachers, what the teacher shared with him, and how he analysed the data.

Moreover, our positionality as bilingual education teacher educators, researchers, and multilingual speakers contributes to our understanding of the value of translanguaging as a transformative pedagogy for inclusion and social justice. As such, our stance, teaching experience, and knowledge shape our perspectives in examining translanguaging practices of the EMI history teacher.

6. Analysis

6.1. Creating a translanguaging space for engaging the whole class

We now analyse examples of how the teacher engages students at the whole class level. In the dataset, ten instances are identified which illustrate how the teacher engages students at the whole class level.

Extract 1:

Engaging All Students in Making a Stance

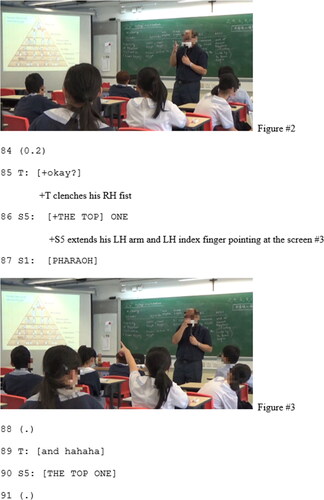

Prior to the extract, the teacher (T) was presenting an image on the PowerPoint which illustrates the social pyramid of ancient Egypt (Image 8). At the top were the pharaoh and those associated with divinity and farmers and slaves made up the bottom. T then invited students to think about whether ancient Egypt was a fair society. T pointed to the bottom of the social structure and explained the meaning of ‘slaves’ and their job responsibilities, including building the Pyramid, transporting goods and laborious work. In the extract, T asks students whether they wish to be a slave in ancient Egypt (line 71) and this leads to a follow-up question which prompts students to consider the social class that they want to be affiliated with (lines 78-83).

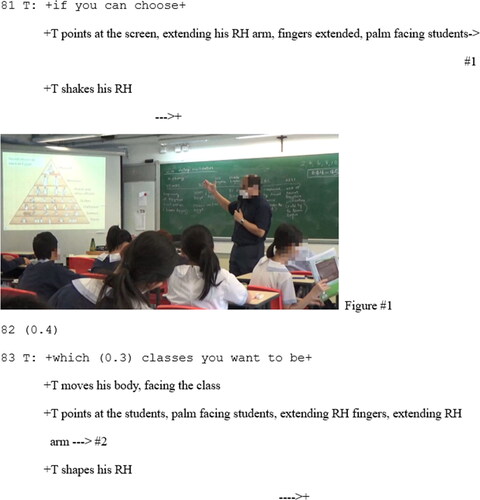

In this classroom scenario, T initiates a discussion about the social classes in ancient Egypt and the roles of slaves ( and ). He invites students to take a stance in terms of their willingness to become a slave (line 71). He also points at the students and looks around the class to invite student participation. This leads to responses from several students by saying ‘no:’ in an extended sound (line 75) to emphasise their unwillingness to become a slave.

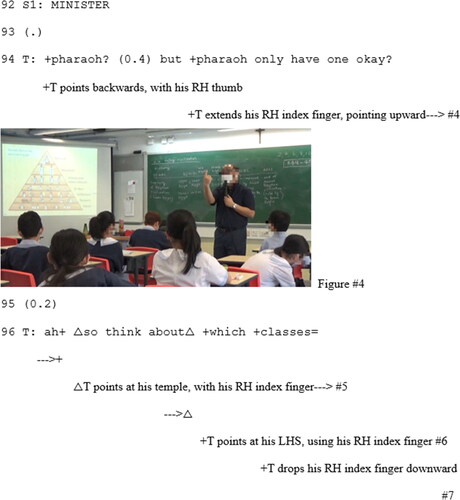

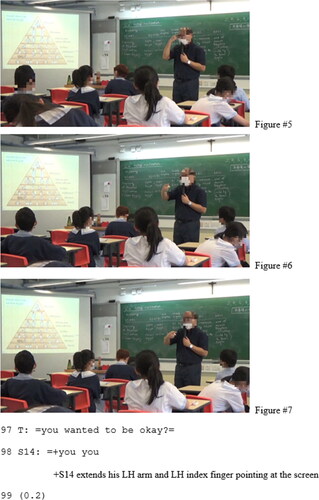

As the discussion unfolds, several students express their desire to be Pharaoh, despite the teacher’s reminder that there can only be one Pharaoh. While T is uttering ‘okay?’ to seek confirmation from students (lines 85), a number of students utter their opinion in a loud voice. In line 86, student 5 yells out ‘THE TOP ONE’ while pointing at the top of the pyramid on the screen to highlight her desire to be Pharaoh. Similarly, student 1 also yells out ‘PHAROH’ to indicate her opinion (line 87; ). Note that teacher B does not stop students from yelling out uninvited responses, rather he initiates a follow-up question (line 94) to invite further responses from students, possibly promoting students’ engagement in this topic. In line 94, T points upwards () to visually represent the numerical number 1 as he utters ‘pharaoh only have one okay?’. This question invites all students to think about the other possible option that students can become if they were in ancient Egypt (line 96; , , ).

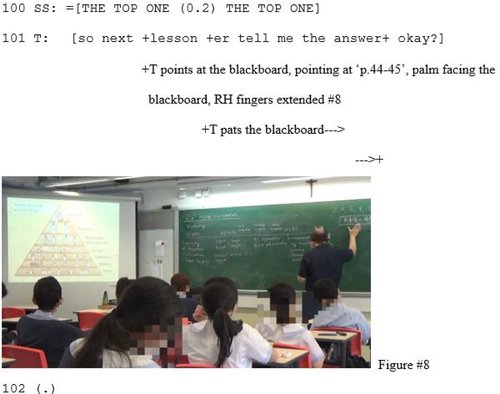

Despite T’s suggestion to students for considering other social classes, a group of students ignore the teacher’s suggestion that there is only one pharaoh, and they repeatedly initiate uninvited responses in loud voice: ‘THE TOP ONE (0.2) THE TOP ONE’, in order to draw T’s attention to their desire to be at the top of the pyramid (line 100). While the students are speaking, T ignores them and invites them to inform their answers to T in the next lesson (line 101; ).

In this extract, it is demonstrated that T utilises various gestures, a visual image of the social class pyramid and his use of if-clause to encourage students to take a stance in terms of the social class that they wish to be affiliated with. It is noticeable that students’ responses are marked with a loud and exaggerated volume, which is audibly different from the way the students normally speak in class, in order to display their opinion which results in laughter from T. T and students’ use of interactional resources (e.g. different ways of speaking, T’s use of if-clause) and multimodal resources craft out a translanguaging space for engaging in meaningful communication about social class in ancient Egypt. However, the analysis of the extract reveals that T only accepts what students say without further elaboration. This begs the question of a lack of language scaffolding, even if there is engagement. It can be argued that T could have used this as an opportunity to scaffold students’ responses to something more academically appropriate. For example, T could have invited the students to justify why they would rather be at the top of the hierarchy. By building on the students’ contributions, T could involve students in co-constructing curriculum knowledge and scaffolding his students’ learning (Haneda 2009). During the video-stimulated-recall-interview, T is asked to explain the rationales for him to engage in playful talk with students and fulfil his pedagogical goals ().

Table 1. Video-stimulated-recall-interview (Extract 1).

In the interview, T argues that encouraging students to think about which ancient Egyptian social class that they want to be in can potentially develop their critical thinking skills as it requires them to make a decision based on the historical facts that they have learnt. T suggests that the majority of the students claim that they want to be the most powerful person. This is possible that students understand the responsibilities of a slave which entails doing laborious work. Alternatively, being a Pharaoh can get access to power and a wide range of students’ answers which involved them imagining themselves living in that historical moment. T is annoyed by the naivety of the student’s written answers since students demonstrate a lack of criticality in terms of the historical context. It can be argued that T sees a value in bridging experiences across spatial and temporal scales (Thibault Citation2011; Ho and Li Citation2018) through inviting students to imaginatively place themselves in a historical context. This has an important pedagogical goal for enhancing students’ historical and critical thinking about the societal system in ancient Egypt.

Although the curriculum limits T in introducing the different social classes in ancient Egypt, T believes that it is important to bridge the gap between historical knowledge and the student’s everyday life experience. This is exemplified in the MCA analysis as T asks students to think about which social class that they wish to be in. Students show their excitement by voicing out their desire to be “the top one” in a loud voice (lines 86, 90, 100). It can be argued that T’s question potentially helps students to imagine themselves travelling back to the ancient Egyptian period and consider what will be like to be surviving in a hierarchical society. By allowing students to engage in such a discussion, it creates a translanguaging space for T and students to utilise various paralinguistic and semiotic resources to communicate and defend their stances. Nevertheless, it can also be suggested that T’s translanguaging practices can be further utilised to scaffold students’ responses, “the top one’. T can first accept the students’ contributions and he can translanguage between everyday and academic speech in order to create opportunities for students to justify their stance of wanting to be “the top one”.

Extract 2:

Extending Student Contributions for Inviting Student Participation

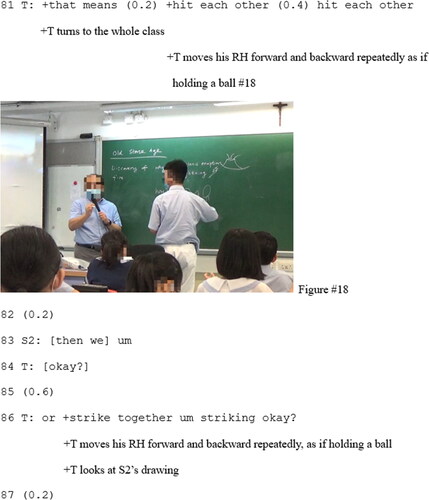

Prior to the extract, T was using English only to introduce the definitions of primary and secondary sources to students and he presented the definitions through the PowerPoint. He attempted to create an imaginary context of a murder scene through mobilising diverse resources in order to develop students’ subject-specific ways of thinking and consolidate students’ understanding of primary and secondary sources in the study of history as a discipline. In this extract, T invites students to think about different examples of primary and secondary sources.

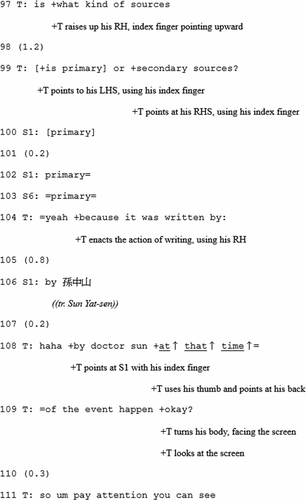

From lines 85-99, T presents a hypothetical scenario about discovering Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s diary, asking students if it would be considered a primary or secondary source. Particularly, T first switches from English to Cantonese to introduce Dr. Sun Yat-sen ‘孫中山’ (line 87). It is possible that T may know that students are familiar with Dr. Sun’s Chinese name, which motivates him to utter Dr. Sun’s name in Cantonese. In lines 95-99, T asks students to classify his diary as a primary or secondary source (lines 95-99; ). Student responds with ‘primary’ (lines 100, 102-103), leading T to further the discussion by initiating a designedly-incomplete utterance (Koshik Citation2002), ‘yeah because it was written by:” (line 104), and gesturing the action of writing. Student 1 (S1) answers with a mix of English and Cantonese, ‘by 孫中山 (Sun Yat-sen)’, in line 106 which is an example of multilingual translanguaging. It is noticeable that S1 first utters the preposition ‘by’ to build on T’s DIU (line 104) and enunciates the answer ‘孫中山’ in Cantonese. Although S1’s response does not align with the school’s EMI language policy, T transforms S1’s response by 1) translating it into English - ‘by doctor sun’ (line 108) and 2) providing additional information to S1’s response (lines 108-109). Notably, T points at his back while uttering the phrase, at↑ that↑ time↑, with stress and raising intonation (line 108) in order to emphasise the past time frame.

Subsequently, T presents more information on the PowerPoint (, ). In line 117, T directs students’ attention to the second point listed on the PowerPoint (i.e. “oral history 口述歷史, letters, diaries”). It is noted that T includes a Chinese translation of ‘oral history’ on the PowerPoint, which enables all students to achieve an understanding of the meaning of the subject-specific terminology. T creates another hypothetical scenario of a murder case that was constructed prior to the extract. Particularly, he invites students to guess the meaning of ‘witness’ (lines 120-127; ). As students have not provided a preferred response in lines 128-130, T provides a short English explanation, ‘he was at […] at the place of the event happen’ (lines 131-133). This leads to S1’s understanding and responding in Cantonese as she says ‘見證人 (witness)’ (line 135), which T positively assesses (line 137) and student 13 also displays his understanding (line 138). T then translanguages by using Cantonese to validate S1’s answer (line 143) and subsequently switching back to English to offer further information about a witness (lines 142-145; , , ).

In this extract, it is seen that T is creating a translanguaging space through mobilising different linguistic (Cantonese and English verbal utterances and bilingual glosses) and multimodal resources in order to acknowledge the value of students’ contributions to the whole-class discussion. In particular, he allows students to tap into Cantonese as their familiar language to deepen their understanding of the concepts of primary and secondary sources and the meaning of ‘witness’. In doing so, such a translanguaging space affords T to promote diverse student participation and creates learning opportunities for all students by expanding on students’ contributions. During the video-stimulated-recall-interview, T explains the purposes of using different linguistic resources in classroom interaction ().

Table 2. Video-stimulated-recall-interview (Extract 2).

T explains that he will make a judgment in terms of whether that word/terminology is considered as a key term. If so, he will choose to use English to explain it. If not, he will prefer to use Cantonese to explain the term to students due to the time limit. It is noticeable that the ways in which T decides his use of language for explaining subject-specific terms are mostly motivated by his goal to prepare students for examination. Such a phenomenon is reflected in the MCA analysis when T uses Cantonese to create a hypothetical scenario of having Dr. Sun’s diaries (lines 85-109) and validate students’ vocabulary explanation of ‘witness’ (line 143). Additionally, it is evident that T only used English to explain the definitions of primary and secondary sources prior to Extract 1. It can be suggested that limited lesson time is a factor that motivates T to determine what language that he should orchestrate in order to enable students to better understand the historical knowledge. Therefore, this video-stimulated-recall-interview extract illuminates additional insights into T’s rationale for using different linguistic resources for shaping students’ contributions in the interaction. Due to the lack of teaching hours, it becomes necessary for T to be strategic in using the appropriate linguistic resources in order to ensure that 1) all students can understand the abstract historical concepts within a limited time and 2) assist all students to have the ability to use particular keywords in the school examinations.

6.2. Creating a translanguaging space at an individual level for catering to individual needs

In this section, we analyse an example of how the teacher engages students with individual needs (Extract 3). In the dataset, two instances are identified which demonstrate the ways the teacher engages individual students.

Extract 3:

Including SEN Student into the Process of Knowledge Construction

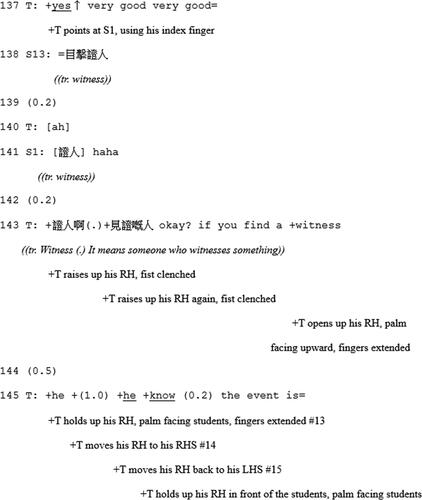

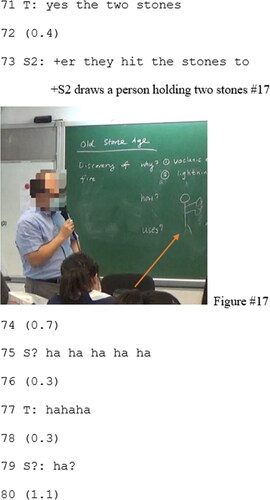

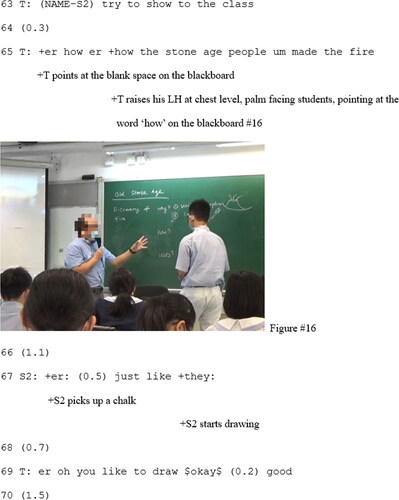

Prior to the extract, T was playing a Youtube clip which illustrated how the old stone age people discovered fire. Before watching the clip, T advised students to pay attention to why and how stone age people made fire. While students were watching the clip, T asked students to identify ways to make a fire. Student 2 (S2) then created voices ‘puss puss puss’ to imitate the sounds of two stones striking and moved his hands forward and backwards to enact the act of striking. Here, S2 aims to convey the idea that striking is a way for the stone age people to make fire. Note that S2 has autism and S2 sometimes struggles to convey his thoughts clearly. T then invites S2 to come out to the class to demonstrate the action of striking.

In lines 63 and 65, T invites S2 to show the action of striking to the class. Particularly, T points at the word ‘how’ on the blackboard () while uttering the question: ‘how the stone age people um made the fire’ (line 65). By doing so, this encourages students to make notes in terms of how the fire was made by the stone age people. Instead of enacting the action, S2 picks up a chalk and he starts drawing on the blackboard as he utters concurrently: ‘just like they’ (line 67). T realises that S2 prefers drawing and he does not immediately stop student 2 from drawing. Rather, T gives permission to S2 as he says: “oh you like to draw $okay$ (0.2) good’, which in turn gives the floor to S2 to engage in drawing (line 69). During the 1.5-second pause, S2 draws two stones on the blackboard (line 70) and T acknowledges S2’s drawing by stating the items that S2 has drawn (line 71). S2 then draws a person holding two stones () and simultaneously S2 provides an additional explanation of his own drawing: ‘they hit the stones to’. As seen in Figure 5, S2 draws out a matchman holding two stones and the stones are represented in the form of circles. The drawing is treated as humorous by a student and T, as evidenced by the laughter in lines 75, 77 and 79. This is possibly because the classroom participants orient to S2’s drawings as basic and mediocre.

Figure 2 & 3. T points at the students, palm facing students, extending RH fingers, extending RH arm. S5 extends his LH arm and LH index finger pointing at the screen.

Figures 5–7. T points at his temple, with his RH index finger. T points at his LHS, using his RH index finger. T drops his RH index finger downward.

Figure 8. T points at the blackboard, pointing at ‘p. 44-45’, palm facing the blackboard, RH fingers extended.

Figure 9. T points at his back, pointing at the blackboard.

Figure 10. T clicks the PowerPoint and reveals the text on the screen. T reveals the text on the screen which includes examples of sites, remains, artifacts, oral history, letters, diaries and government documents.

Figure 12. T points at his eyes, using his index fingers.

Figure 13–15. T holds up his RH, palm facing students, fingers extended. T moves his RH to his RHS. T moves his RH back to his LHS.

Figure 16. T raises his LH at chest level, palm facing students, pointing at the word ‘how’ on the blackboard.

In line 81, T shifts from individualised orientation to whole class orientation as he offers an additional explanation of the meaning of ‘striking’ to all students. Specifically, T turns his gaze to the whole class in order to signal to the class that he is introducing new knowledge to the class. T then utters ‘hit each other’ repeatedly while moving his right-hand forward and backwards repeatedly () which allows T to both verbally and visually explain the action of striking to all students. Although S2 is still drawing (line 83), T continues to offer vocabulary explanations to the whole class. In line 86, T takes the opportunity to extend his vocabulary explanation by introducing the target vocabulary item ‘striking’ to students. T enacts the gestural action of striking (), and this is accompanied by his verbal explanation, ‘or strike together um striking’. T’s vocabulary explanation deliberately includes the target word ‘strike’ and T explicitly connects it back to his simple linguistic utterances in line 81.

In this extract, it is evidenced how T opens up a translanguaging space by providing opportunities for S2 to engage in drawings for visualising his understanding to the class. This space facilitates the participation of S2, who is an SEN student, in the process of knowledge construction. While S2 is drawing, T also provides additional explanations about S2’s drawings to the class through using English and various gestural actions in order to assist other students in the class to make sense of S2’s drawings of the action of striking. During the video-stimulated-recall-interview, T comments on the pedagogical goals for allowing S2 to draw on the blackboard ().

Table 3. Video-stimulated-recall-interview (extract 3).

It is noticeable that T expects S2 to enact the action of striking in front of the class, rather than asking him to draw pictures on the blackboard. However, T eventually allows S2 to carry on with his drawings. It is questionable in terms of why T did not request S2 to do the action. This is because T could have taken a more authoritative position and asked S2 to follow the instruction since T needs to cover the curriculum content within the limited lesson time. Nevertheless, T shows his understanding of S2’s personality traits since he realises that S2 seldom listens to instructions and he has his own way of doing things. T gives an example of S2 not listening to orders: “即係佢答緊嘢呢, 你想stop佢呢, 佢都會繼續係囉 (when he is responding in the interaction and you want to stop him, he will continue to speak and ignore your request)”. It can be argued that T is aware that S2 has autism and based on T’s extensive experience in working with SEN students as Head of Guidance and SEN, he understands S2’s autism characteristics. This motivates him to give the interactional floor to S2 which affords him to visualise and verbalise his thoughts.

In addition to including S2 into the knowledge construction process, it is evidenced in the MCA analysis that T adds further descriptions of S2’s drawings to the whole class while S2 is drawing in order to fully utilise the lesson time to maintain the whole class engagement. T explains that it is part of his plan to elaborate on S2’s drawings so that all students can make sense of what S2 has drawn on the blackboard. This demonstrates that T has created a translanguaging space in the classroom for promoting student engagement at both individual and whole class levels. At an individual level, the space affords S2 in utilising drawing in a way that is comfortable for him to express his understanding of the meaning of ‘striking’, although S2 does not engage in the way that T expects (i.e. using gestures to represent the action of striking). At a whole-class level, the students at first are not empathetically engaged with S2, as shown through a student’s laughter in lines 75 and 79. It is observable that T attempts to engage all students by offering additional explanations of S2’s drawings while S2 is taking his time to draw the whole picture on the blackboard. This allows all students to learn the meaning of ‘striking’, which is an important term in understanding the life of the old stone age people.

7. Discussion and conclusion

This paper aims to reveal how the EMI history teacher deploys various linguistic and multimodal resources to create different translanguaging sub-spaces to stimulate student engagement in the classroom. In order to identify examples of the teacher stimulating student engagement, interactional behaviours are tracked through analysing student’s responses, as reflected during the interaction (Sandlund and Greer Citation2020). Extracts 1 and 2 demonstrate the ways in which the teacher creates a translanguaging space for engaging students at a whole-class level. Extract 1 demonstrates the way in which the teacher constructs a playful translanguaging space for students to engage in whole-class discussion regarding their preferences to be affiliated with one of the social classes in ancient Egypt. The teacher skillfully utilizes the visual image on the PowerPoint and gestures to complement his guided questions in order to invite students to form an opinion regarding their choice. The MCA analysis of Extract 1 has also revealed that the student’s gestures, laughter, raised volumes and mounting excitements are indicators of their engagement on the whole class discussion. In particular, the teacher encourages students to envision themselves travelling back to ancient Egypt and contemplate what it might have been like to survive in a hierarchical society. This type of discussion creates a space in which the teacher and the students can use different paralinguistic and semiotic resources to communicate and justify their perspectives. Nevertheless, it is noted that the teacher could have translanguaged between everyday and academic language to not only validate the students’ point of view, but also expand on the students’ contributions by inviting them to justify their respective positions and co-construct curriculum knowledge. Extract 2 illustrates how the teacher is establishing a translanguaging space by utilizing various linguistic and multimodal resources, including Cantonese and English verbal expressions and bilingual glosses, to recognize the significance of students’ input in the whole-class exchange. Specifically, he extends students’ contributions by asking follow-up questions in order to invite students to elaborate their own ideas, opinions, and perspectives and promote student participation. In Extract 2, the teacher permits students to employ Cantonese, their native language, to construct their understanding of the concepts of ‘primary and secondary sources’ and the meaning of a subject-specific terminology (i.e. ‘witness’). Such a translanguaging space enables the teacher to encourage diverse student contributions to class discussions and expand on those contributions to foster learning opportunities.

On the other hand, Extract 3 differs from Extracts 1-2 which illuminates a different kind of engagement. The extract reveals how the teacher creates a translanguaging space at an individual-level for catering to a particular student’s learning needs. Specifically, the teacher attempts to engage an SEN student by attending to student 2’s self-initiation of unintelligible sounds, due to his inability to articulate the idea in English. In this extract, it is evidenced that the teacher creates a translanguaging space by offering opportunities for student 2 to engage in drawings to visually demonstrate his understanding to the whole class. Concurrently, the teacher attempts to engage other students in the class through a balance between whole-class management and engaging individual students. It is evidenced that the teacher offers verbal English explanations of ‘striking’ through using simple linguistic utterances while student 2 is drawing in order to scaffold the whole student’s understanding and engage their attention.

It is evidenced that the teacher orients to the English-only policy in Extracts 1 and 3. Nevertheless, it is shown that the teacher is engaging in translanguaging practices as he synchronizes his English verbal utterances with his use of multimodal and multi-semiotic resources, such as gestures, pictures and intonations, to compensate for restricted L1 use and promote student engagement in the classroom. As explained in section 4, the notion of translanguaging encourages us to attend to a range of multimodal and multi-semiotic resources whilst rejecting to privilege specific communicative modes and methods for creating meanings over other resources (Li Citation2018). In other words, translanguaging is not about using more named languages in teaching and learning or simply employing different communicative means (including spatial, technological or gestural) of interactions. The analytical focus is on how the teacher mobilises different resources to shape his/her to facilitate student participation in the classroom discourse. That is, it is not quantity but quality that matters in the process of knowledge construction. A seemingly slight change in gestures or ways of speaking can alter the meaning of a message, which is just as significant as a change in the choice of named languages. Hence, the notion of translanguaging aims to challenge the traditional lingual bias which focuses primarily on conventionalised speech and writing.

This paper reinforces the view of inclusive pedagogy, such as translanguaging, as a right to participate in educational practices and explains how EMI teachers can strategically draw on appropriate resources to deepen student’s engagement in the classroom. As the significance of translanguaging is being recognized in the field of applied linguistics and academics have been suggesting teachers to integrate translanguaging in the EMI classrooms, it is essential to better understand how multiple translanguaging spaces can afford teachers to bring the relevant multilingual and multimodal resources and sociocultural knowledge for engaging students in classroom learning. In this study, we argue that the process of engaging student’s learning is a process of translanguaging which requires the EMI teacher to construct different translanguaging spaces in order to cater for the different needs of all students and faciliate their learning success in the classrooms. Inspired by the work by Trussler and Robinson (Citation2015), this paper proposes that an EMI classroom can be conceptualized as an integrated translanguaging space (Li Citation2011; Tai and Li Citation2020; Tai Citation2023b) and it involves different translanguaging sub-spaces. These translanguaging sub-spaces can be constructed to maximise student engagement at a whole-class level and at an individual level respectively. When creating a translanguaging sub-space at the whole-class level, the teacher needs to have all students in mind instead of focusing on the majority or the minority when engaging in translanguaging practices during classroom activities, so that it can make learning more accessible for all students. At the individual level, this requires the teacher to focus on using translanguaging to engage students with specific learning difficulties so that it can bring equal access to educational opportunities and full participation in the context of whole-class teaching. Throughout the paper, we have demonstrated how multiple translanguaging sub-spaces are created and how these sub-spaces afford teachers and students to bring in a range of linguistic and multimodal resources and various kinds of knowledge into the lessons for facilitating understanding and meaning-making processes and achieving a range of pedagogical goals.

In terms of how the teacher makes sense of his use of translanguaging in engaging students in learning in the classroom, the analysis of the video-stimulated-recall-interview data exhibits the teacher’s open attitude towards the flexible use of language and multimodal resources in the EMI history classroom for students to learn the historical knowledge. Importantly, the teacher also stresses the significance of inviting students’ proactive contribution to the learning processes. Particularly, the teacher believes that inviting students to respond to questions, such as asking them to take a stance, initiating follow-up questions and extending students’ contributions through using different linguistic and multimodal resources can develop their historical and critical thinking skills (). This can engage students’ learning and the engaged students are likely to create more engagement among their peers. This is especially evidenced in Extract 1 where students are excited to yell out their opinion in raising volume which signals their mounting excitement. Moreover, the teacher also acknowledges the need to understand a particular student’s autism characteristics and values the alternative ways for students to express their understanding (). By doing so, the teacher can include students with individual needs in the knowledge construction process. Hence, the teacher’s pedagogical beliefs in inclusive education and multilingualism are essential in constructing a translanguaging space for inspiring active student participation and creating a positive climate in the classroom.

The findings contribute to the current literature on translanguaging and EMI education in a number of ways. Theoretically, the study reconceptualises the EMI classroom as an integrated translanguaging space which entails the teacher to create different translanguaging sub-spaces through the use of diverse multilingual and multimodal resources in contexts with rigid language policies in order to enable multilingual teachers to be more inclusive at the individual and whole-class levels. Methodologically, this study highlights how adopting the combination of MCA and IPA can assist us to understand the way that teachers can create translanguaging sub-spaces for making learning accessible for all students in an EMI classroom. Such a methodological approach emphasises the need for researchers to pay attention to the details of how the teachers interact with the environment and how they orchestrate different resources, orient and adapt their bodies in relation to the students and artefacts in the classroom in order to understand inclusive pedagogical practice as a dynamical process of deepening student engagement (Li Citation2018). Regarding pedagogical implications, the classroom interaction analysis affords EMI teachers with tools for understanding classroom interaction at a deep level, with the potential for fostering effective instructional strategies for increasing student engagement and allowing student voice and choice (Jiang et al. Citation2022; Mendoza Citation2023).

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to thank the EMI history teacher and students who participated in this study. Thanks must also be given to the anonymous reviewers who took time to give feedback on our work. We would like to thank Assistant Professor Jenifer Ho (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Assistant Professor Anna Mendoza (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) for giving us invaluable ideas and input for this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kevin W. H. Tai

Professor Kevin W. H. Tai is Assistant Professor of English Language Education and Co-Director of the Centre for Advancement in Inclusive and Special Education (CAISE) at the Faculty of Education in The University of Hong Kong. Additionally, he is Honorary Research Fellow at IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society in University College London (UCL). He was recently awarded the RGC Early Career Award (ECA) in 2023/24 from the Research Grants Council (RGC) of Hong Kong and the Faculty Early Career Research Output Award from the Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong for recognising his excellent achievements in research. In relation to his editorial positions, Kevin Tai is Associate Editor of The Language Learning Journal (ESCI-listed Journal; Routledge), Assistant Editor of the International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (SSCI-listed Journal; Routledge) and Managing Guest Editor of Learning and Instruction (SSCI-listed Journal; Elsevier). His research interests include: language education policy, classroom discourse, translanguaging in multilingual contexts and qualitative research methods (particularly Multimodal Conversation Analysis, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and Linguistic Ethnography). Kevin Tai is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (FRSA) and an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (AFHEA).

Li Wei

Professor Li Wei is Director and Dean of IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society, University College London (UCL), where he is also Chair of Applied Linguistics. His work covers different aspects of bilingualism and multilingualism. He is Editor of the International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism and Applied Linguistics Review. He is a Fellow of the British Academy, Academia Europaea, Academy of Social Sciences (UK), and Royal Society of Arts (UK).

References

- Ainscow M, Booth T, Dyson A. 2006. Improving schools, developing inclusion. London: Routledge.

- Averill R. 2012. Caring teaching practices in multiethnic mathematics classrooms: attending to health and well-being. Math Ed Res J. 24(2):105–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-011-0028-x

- Baralt M, Gurzynski-Weiss L, Kim Y. 2016. Engagement with the language: how examining learners’ affective and social engagement explains successful learner-generated attention to form. In: Sato M, Ballinger S, editors. Peer interaction and second language learning: pedagogical potential and research agenda. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; p. 209–239.

- Bonacina-Pugh F. 2012. Researching ‘practiced language policies’: insights from conversation analysis. Lang Policy. 11(3):213–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-012-9243-x

- Brouwer CE, Wagner J. 2004. Developmental issues in second language conversation. J Appl Linguist. 1(1):29–47. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.1.1.29.55873

- Chan JYH. 2013. A week in the life of a ‘finely tuned’ secondary school in Hong Kong. J Multilingual Multicultural Dev. 34(5):411–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.770518

- Chan JYH. 2014. Fine-tuning language policy in Hong Kong education: Stakeholders’ perceptions, practices and challenges. Lang Educ. 28(5):459–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.904872

- Chan C, Lo M. 2017. Exploring inclusive pedagogical practices in Hong Kong primary EFL classrooms. Int J Inclusive Educ. 21(7):714–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1252798

- Dao P, Nguyen MXNC, Iwashita N. 2019. Teachers’ perceptions of learner engagement in L2 classroom task-based interaction. Lang Learn J. 49(6):711–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2019.1666908

- Evans S. 2002. The medium of instruction in Hong Kong: policy and practice in the new English and Chinese streams. Res Papers Educ. 17(1):97–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520110084030

- Ford CE. 2012. Clarity in applied and interdisciplinary conversation analysis. Discourse Stud. 14(4):507–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445612450375

- Garcia O, Li W. 2014. Translanguaging: language, bilingualism and education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Helme S, Clarke D. 2001. Identifying cognitive engagement in the mathematics classroom. Math Ed Res J. 13(2):133–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03217103

- Ho WYJ, Li W. 2019. Mobilizing learning: a translanguaging view. Chin Semiot Stud. 15(4):533–559. https://doi.org/10.1515/css-2019-0029

- Jefferson G. 2004. Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In: Lerner G, editor. Conversation analysis: studies from the first generation. Philadelphia: John Benjamins; p. 14–31.

- Jiang L, Gu MM, Fang F. 2022. Multimodal or multilingual? Native English teachers’ engagement with translanguaging in Hong Kong TESOL classrooms. Appl Linguist Rev. Epub ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0062

- Kan V, Lai KC, Kirkpatrick A, Law A. 2011. Fine-tuning Hong Kong’s medium of instruction policy. Strategic Planning Office and Research Centre into Language Education and Acquisition in Multilingual Societies, Institute of Education, Hong Kong.

- Kim Y, McDonough K. 2011. Using pretask modelling to encourage collaborative learning opportunities. Lang Teach Res. 15(2):183–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810388711

- Koshik I. 2002. Designedly incomplete utterances: a pedagogical practice for eliciting knowledge displays in error correction sequences. Res Lang Social Interac. 35(3):277–309. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3503_2

- Lambert C, Philp J, Nakamura S. 2017. Learner-generated content and engagement in second language task performance. Lang Teach Res. 21(6):665–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816683559

- Lawson MA, Lawson HA. 2013. ‘Newconceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy and practice. Rev Educ Res. 83(3):432–479. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313480891

- Lee Y. 2007. Third turn position in teacher talk: contingency and the work of teaching. J Pragma. 39(6):1204–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2006.11.003

- Li W. 2011. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. J Pragma. 43:1222–1235.

- Li W, Ho WYJ. 2018. Language learning sans frontiers: a translanguaging view. Ann Rev Appl Ling. 38:33–59.

- Li W. 2018. Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. ApplLinguist. 39:9–30.

- Li W. 2020. Multilingual English users’ linguistic innovation. World Englishes. 39(2):236–248.

- Li W. 2023. Transformative pedagogy for inclusion and social justice through translanguaging, co-learning, and transpositioning. Lang Teach. :1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444823000186

- Lin AM, Wu Y. 2015. May I speak Cantonese?’–Co-constructing a scientific proof in an EFL junior secondary science classroom. Int J Bilingual Educ Bilingualism. 18(3):289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2014.988113

- Maehr ML. 1984. Meaning and motivation: toward a theory of personal investment. In Ames RE, Ames C, editors. Motivation in education: student motivation. Vol. 1. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; p. 115–144.

- Markee N. 1995. Teachers’ answers to students’ questions: problematizing the issue of making meaning. Issues Appl Linguist. 6(2):63–92. https://doi.org/10.5070/L462005218

- Mendoza A. 2023. Translanguaging and English-as-a-Lingua Franca in the plurilingual classroom. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

- Mercer N. 1995. The guided construction of knowledge: talk amongst teachers and learners. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

- Mercer S. 2015. Dynamics of the self: a multilevel nested systems approach. In: Dörnyei Z, MacIntyre PD, Henry A, editors. Motivational dynamics in language learning. New York: Multilingual Matters; p. 139–163.

- Mercer S. 2019. Language learner engagement: setting the scene. In: Gao X, Davison C, Leung C, editors. International handbook of English language teaching. Cham: Springer; p. 1–19.

- Mercer S, Dörnyei Z. 2020. Engaging students in contemporary classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mondada L. 2018. Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: challenges for transcribing multimodality. Res Lang Social Interac. 51(1):85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

- Morell T. 2007. What enhances EFL students’ participation in lecture discourse? Student, lecturer and discourse perspectives. J English Acad Purpose. 6(3):222–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2007.07.002

- Philp J, Duchesne S. 2016. Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Ann Rev Appl Linguist. 36:50–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190515000094

- Phung L. 2017. Task preference, affective response, and engagement in L2 use in a US university context. Lang Teach Res. 21(6):751–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816683561

- Poon AYK. 2009. A review of research in English language education in Hong Kong in the past 25 years: reflections and the way forward. Educ Res J. 24(1):7–40.

- Poon AYK. 2010. Language use, language policy and planning in Hong Kong. Curr Issues Lang Plann. 11(1):1–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664201003682327

- Poon AYK, Lau CMY, Chu DHW. 2013. Impact of the fine-tuning medium-of-instruction policy on learning: some preliminary findings. LICEJ. 4(1):1037–1045. https://doi.org/10.20533/licej.2040.2589.2013.0138

- Reeve J. 2012. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. New York: Springer; p. 149–172.

- Roos H. 2019. Inclusion in mathematics education: an ideology, a way of teaching, or both? Educ Stud Math. 100(1):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-018-9854-z

- Sah P, Li G. 2022. Translanguaging or unequal languaging? Unfolding the plurilingual discourse of English medium instruction (EMI) in Nepal’s public schools. Int J Bilingual Educ Bilingualism. 25(6):2075–2094. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1849011

- Salend SJ, Garrick-Duhaney LM. 1999. The impact of inclusion on students with and without disabilities and their educators. Remedial Spec Educ. 20(2):114–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193259902000209

- Sandlund E, Greer T. 2020. How do raters understand rubrics for assessing L2 interactional engagement? A comparative study of CA- and non-CA-formulated performance descriptors. SiLA. 9(1):128–163. https://doi.org/10.58379/JCIW3943

- Sato M, Lyster R. 2012. Peer interaction and corrective feedback for accuracy and fluency development. Stud Second Lang Acquis. 34(4):591–626. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263112000356

- Seedhouse P. 2004. The interactional architecture of the language classroom: a conversation analysis perspective. London: Blackwell.

- Sharma BK. 2023. A new materialist perspective to studying L2 instructional interactions in engineering. Int J Bilingual Educ Bilingualism. Epub Ahead of Print. 26(6):689–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1767030

- Slee R. 2004. Inclusive education: A framework for reform? In: V. Heung, M. Ainscow, editors. Inclusive education: a framework for reform? HK: HK Institute of Education.

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. 2013. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method, and research. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE.

- Spurgeon W. 2007. Diversity and choice for children with complex needs. In: R. Cigman, editor. Included or excluded? The challenge of the mainstream for some SEN children. London: Routledge.

- Storch N. 2001. How collaborative is pair work? ESL tertiary students composing in pairs. Lang Teach Res. 5(1):29–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216880100500103

- Storch N. 2008. Metatalk in a pair work activity: level of engagement and implications for language development. Lang Aware. 17(2):95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410802146644

- Svalberg AM-L. 2018. Researching language engagement; current trends and future directions. Lang Aware. 27(1-2):21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2017.1406490

- Tai K. W. H. 2022a. Translanguaging as inclusive pedagogical practices in english medium instruction science and mathematics classrooms for linguistically and culturally diverse students. Res Sci Educ. 52(3):975–1012.

- Tai KWH. 2022b. A translanguaging perspective on teacher contingency in Hong Kong english medium instruction history classrooms. Appl Linguist: Epub ahead of Print.

- Tai KWH. 2023a. Cross-curricular connection in an english medium instruction western history classroom: a translanguaging view. Lang Educ: Epub ahead of Print.

- Tai KWH. 2023b. Multimodal conversation analysis and interpretative phenomenological analysis: a methodological framework for researching translanguaging in multilingual classrooms. London: Routledge.

- Tai KWH, Li W. 2020. Bringing the outside in connecting students’ out-of-school knowledge and experience through translanguaging in Hong Kong english medium instruction mathematics classes. System. 95:102364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102364

- Tai KWH, Li W. 2021. Co-learning in Hong Kong english medium instruction mathematics secondary classrooms: a translanguaging perspective. Lang Educ. 35(3):241–267.

- ten Have P. 1990. Methodological issues in conversation analysis. Bull Méthodol Sociol. 27(1):23–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/075910639002700102

- ten Have P. 2007. Doing conversation analysis. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Thibault PJ. 2011. First-order languaging dynamics and second-order language: the distributed language view. Ecolog Psychol. 23(3):210–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10407413.2011.591274

- Trussler S, Robinson D. 2015. Inclusive practice in the primary school: a guide for teachers. London: SAGE.

- Walsh S. 2002. Construction or obstruction: teacher talk and learner involvement in the EFL classroom. Lang Teach Res. 6(1):3–23. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168802lr095oa