Abstract

Diffracting a research project in a UK primary school, this paper concerns feminist materialist orientations to odd-ness as a relational, distributed, and affective form of “thinking-feeling”. It suggests that attuning to affect as it moves through a context resistant to disruption, involves becoming “bad researchers”; bad for composing an unruly research problem, for embracing a transgressive methodology, and for writing in willfully inconclusive ways. It comments too on the dangers of embracing badness as an identity if used to conceal rather than acknowledge ongoing inequalities between researchers and children and between privileged researchers and others routinely marginalised.

Keywords:

Introduction

Throughout this paper, we make several moves. We dip into the broader UK context of education and associated processes of schooling that shape children’s sense of what it means to grow and develop outside of a “normal” developmental trajectory so readily determined and practiced by what Barker and Mills (Citation2018) refer to as the “psy-disciplines”. We then turn to one particular school site where staff are committed to working with tensions evoked by living with such psycho-pathologisation whilst trying to develop inclusive practices. Here, we introduce our research project called Odd: feeling different in the world of education. We briefly outline the impetus behind this study before paying much closer attention to the topological practices emerging from one of its compositional methodologies, Position of Child.

From deep in the midst of the socializing, disciplinary, and normalizing work of school, we attempt to communicate our affective encounters with odd-ness, transgression, and productive discomfort. We explore this as researchers working in the host school’s nursery class, with children from a diverse range of backgrounds where Amanda devised and took up “Position of Child”, an interdisciplinary methodology involving participant sensation (Weig, Citation2020), and Rachel acted in both a carer/parental role to Amanda, and as a researcher invested in observing Amanda’s daily wayfaring through school. We fold out the “problem space” Lury (Citation2021) of Position of Child to articulate how it might be perceived as “bad” research, whilst troubling the currency of “bad” when coming from the researchers’ privileged positions. We then enfold into an instance, an affective encounter in the nursery classroom drawn from Position of Child’s undulating composition. Entangling Amanda, a white researcher and a dual heritage nursery child, Samuel, with globes of spittle, the paper move into an opaque landscape of carpet piles and moisture, secrecy, and complicity as we sink into the murky always-more-than-one (Manning, Citation2013) relational middle of the encounter. The spit event features as an interruption to the typical order of school, including the conventional logics of child development, opening up a counter-intuitive moment of refusing stasis and becoming wild. Caught up with a child’s improvisations in the opaque folds of the school assemblage, we acknowledge the positions from which our writing issues: white, entitled, cisgendered, and queer, steeped in a middleness that can never be fully understood nor articulated, but is always connecting with the materiality and fleshy life of the research site that exceeds its place and time in the world, and refuses to fully coalesce within the structures that act to tame and confine it.

In making these moves we mobilise different writing strategies by writing across tenses and linguistic styles to invoke differently textured research milieu; movements we try to articulate in between what feels like the arid landscape conjured by researcher voice and the moist underworld where Amanda, in Position of Child, found herself immersed and which appeared to her as “the kelp forest”. These moves seek to produce a deliberate instability of times, spaces, and voices.

Feeling different—interrupting conventional logics of child development

The research project, Odd: feeling different in the world of education, was based in a primary school in the northwest of England and was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Our Odd research took place over an initial three-years (2018–2021) and was further extended by six months due to the partial closure of the school and other impacts of COVID19 on the life of the community. In addition to Alma Park School, our research partners included Catalyst Psychology, National Children’s Bureau, and the Anti-bullying Alliance. The project was borne from our concern that despite decades of interventions, anti-bullying campaigns, and inclusion initiatives, school remains a hostile place for many children. Caught up in streams of developmental practices authorised by what Barker and Mills refer to as the psy-disciplines (2018), children’s experiences of school are deeply enmeshed in the cartesian underpinnings of the education system maintained by complicit understandings of the young emerging self as a mind joined to, but gradually learning to overrule its body.

The “normal” developmental trajectory built into primary education’s model of the unfolding child fails to recognise change as something continuously ongoing, divergent, excrescent, manifold, and collective, presuming a carefully regulated move from one predefined position to another. We propose that the imposition of conformity to compare and evaluate difference in the classroom, tasks children to grow in prescribed steps towards increasing “possession” of themselves, positioning any difference to what is categorised as “normal”, as a failure of tidy steps towards adulthood. As Sue Chantler (Citation2013, p. 73) argues, we identify or label only those deemed to be “abnormal” and the phenomenon of labelling reflects how particular psy-disciplines, such as psychiatry, medicine, and psychology inform school practices in the construction of some children as “disorderly or disordered”. The realities and impact of “feeling different” when difference is perceived or encountered as problematic can leave some children feeling awkward, overlooked, odd, misunderstood, and isolated in school, whilst others can be experienced by staff as recalcitrant and illegible (Bohlmann, Citation2016; Watson, Citation2016; Wolff, Citation1995). The way schools, as part of a busy and productive education system, contribute to a young person’s learning about where, and in what ways they “fit in”, matters to their experiences in—and beyond—school.

Odd research—being counter-intuitive

We all, as human beings, have to navigate surprising and sometimes unsettling things and experiences that seem or feel odd, out of place, or different. The research set out to interrogate the idea of oddness with the children and wider school community, particularly wherever we came to sense and respond to oddness in school, and in whatever ways it affected us, the building and stuff of school, the furniture, things and the young people around us. The research opened up an unruly problematic field, offering a series of provocations, whilst anchoring itself in the lived, sensory, and embodied experiences of school, situating knowledge and knowing within the community itself. Mindful that well-established school-based humanist inquiry can overlook the entanglements of matter and meaning vital to sensing differences experienced in school, we attuned to the creative potential of art practice coupled with qualitative research methodologies (Irwin et al., Citation2005; Rotas & Springgay, Citation2014; Schneider & Wright, Citation2005) to develop a structure of school-based research in which our inquiries might flourish in more unruly, improvisational and compositional ways.

The research team included visual anthropologist Amanda Ravetz, artist Becky Shaw, artist researcher Jo Ray, artist consultant Steve Pool and two educational researchers Rachel Holmes and Kate Pahl, who pursued streams of research methods, as well as techniques that coalesced around ideas of encountering and composing oddness in school. We sought inter-disciplinary forms of knowledge production, engaging with the school as a moving collection of bodies, of matter, of relationships, and of time. This required skill and curiosity about how the ordinary forces of encounter might “galvanize hives of activity and determine the twists and turns difference might take” (Stewart, Citation2007, p. 84). Tuning into such forces, the team drew on a range of art practices to pay close attention to how various bodies combine, how expression finds its mode, how whole regimes of signs and scales constitute lines of interrogation, ranging from the microscopic to the discursive; the politic to the haptic; the conceptual to the sonic.

Like the vast majority of educational provision for the youngest children, the physical building and structural body of the school where the Odd project was co-produced was deeply regulated and compartmentalised within the wider system of education. Bounded classroom spaces, discrete age-related cohorts of pupils, categorical curriculum subjects, all fixed in their organisation. The materiality and fleshy life of school disrupted this regulation however, always exceeding its place and time in the world, refusing to fully cohere or to be possessed within the structures that sought to tame and confine it (Moten, Citation2014). Committed to the school’s deeply complex, composite right to opacity (Glissant, in Davis, Citation2019), this Odd research wanted to embrace rather than defy the resistance accomplished through this imperceptibility, to be complicit with a middleness that could never be fully understood nor articulated.

Position of child—becoming wild

In 2018, near the start of the research project, Rachel and Amanda suggested to the partner school that Amanda take up “Position of Child” in the nursery. Position of Child was an ekphrastic phrase that swam into Amanda’s mind when Rachel (as Principal Investigator on the project) asked her what she wanted to contribute to the research. She imagined herself alongside the children, inhabiting the same material and affective conditions, staying close to the ground, wearing the same clothing (a school uniform of grey trousers, yellow aertex shirt, black sweatshirt), and being spoken to by teachers and assistants in the same way they spoke to the children.

For the period of a week Amanda was brought to school each day and picked up in the afternoons by Rachel, mirroring the daily practices of nursery class children and carers. She joined in all classroom activities, including one to one reading practice with the teaching assistant, numeracy, phonics, self-directed play, and sports day. She was addressed by adults who came into contact with her as a new child would be. She had previously outlined her suggested rules of engagement to staff and parents. Rooted in the ethical research principal to “do no harm”, and supported by the Odd research ethics protocol, these included not speaking in a child-like voice; being open about her intentions as a researcher when questioned by children; being led by children, rather than initiating interactions with them; not questioning children about home or school life. Key was the notion of children’s assent or lack of it, whether indicated verbally or through body language—for example, a child walking away from the researcher, an averted gaze, or utterances, such as “I want to be alone” were all taken as lack of assent for research purposes.

Amanda’s interest in sensory participation and undergoing, led her during her week in nursery to avoid adult capacities and associated roles which might too easily eject her from the body-thinking experienced as part of Position of Child. She averted her eyes from the classroom clock from the very first day, knowing it would give her information that might break her ability to stay in the present moment and which the children around her might not have the same access to. It seemed vital to protect the strangeness of being displaced from her habitual adult identity and self-recognition, in order to become part of what increasingly felt like an assembly of children.

Amanda’s impulse to be displaced from an adult positioning in material and affective ways drew on her practice of observational cinema, or OC (Grimshaw & Ravetz, Citation2009) in which the filmmaker’s remit to direct the action is surrendered in favour of respectfully following the sensorially-, socially- and politically-situated experiences of a film’s protagonists by “sharing with them the improvisatory character of lived experience” (Grimshaw & Ravetz, Citation2009, p. 543). Although she was not working at this time with a camera, the precepts of OC guided her ethnographic approach. Added to this was a commitment to artistic research as a form of “undergoing”, a practice of conscious submission to an unfolding environment rather than a methodology reliant on mastery and agentive doing (Ingold, Citation2014).

The idea to dress like the children drew on Amanda’s vague memory of an art work once described to her by Becky Shaw (Co-investigator on the project) in which the artist wore school uniform. The work, it turned out, had been made by Pilvi Takala, who at the time was an exchange student at Glasgow School of Art. Every day as Takala walked to the art school she passed younger students from a private Catholic school. Walking amongst them she felt alienated and ignored: “I know they are probably just like normal kids back home, only in weird clothes.” Takala purchased a second-hand school uniform to wear in the streets around the school (2005) and devised three rules for herself: to stay in public areas, not to approach anyone of her own accord, and not to lie about anything. A few weeks later, based on a split-second decision, the artist allowed herself to be swept through the school gates with some of the school’s pupils. A suspicious teacher called her over at which point she identified herself as an art student, not a school pupil, bringing the work to an end.

Position of Child drew on one element of Takala’s work—the power of dress—in its attempt to get closer to children’s experiences of feeling odd in school. Amanda quickly found that the apparently simple adjustments of wearing school clothing, together with sitting on the floor, running in the playground, playing in the sandpit, or being part of the children’s line for playtime or assembly “produced new experiences and feeling” (Warming, Citation2011, p. 45). In its disturbance of social norms, this underlined the ethical dilemmas of carrying out research about childhood with children.

To Christina MacRae, an early years specialist and colleague generous in sharing her responses and ideas with Rachel and Amanda, Position of Child resonated with, but also differed from, Nancy Mandell’s Least Adult Role (LAR) through which Mandell (and others since) adopted the position of an ethnographer in early years classrooms (1988). While Position of Child and LAR both share an attempt to enter a lifeworld that is mostly closed off to everyday adult experience, in LAR, as described by Mandell, rapport involves observation, which leads to joint action based on objects employed by children for social ends. Mandell theorises transactions where the rules have to be learned well enough by the adult to be able to enter into the children’s system of exchange as an equal and where children move objects to establish an alternative and parallel ecology of social practice. But as Christina MacRae pointed out in Position of Child, rapport is imagined as something that happens through sensation and immersion such that affect and soma became rich forms of participation, exchange, and methodological composition.

From Position of Child Amanda became aware of a powerful ethos being practised by the children themselves. They observed what was unfolding within and around them, moment by moment, with a presence that she found remarkable, but relatable, since on taking up Position of Child each day she fell sharply out of retrospective or anticipatory thinking, into an expansive body-focused perception. Her companions appeared mutually attuned to the ongoing flux of experience, whether physical discomfort, painful or pleasant emotions, acts of cooperation and coercion; they were adept at witnessing and responding to their own and each other’s feelings, ideas and dilemmas, offering and eliciting kindness, solidarity, protection, mediation, and interpretative commentary. For Amanda these acts of watching, listening, speaking, comforting, and where needed seeking adult help, seemed to constitute an overlooked ethics of presence amongst the nursery children.

Amanda nonetheless occupied a highly ambiguous status through Position of Child. Her classmates frequently noted her differences from them, quizzing her about her size, age, hair colour, teeth, family status, and reasons for being there. Rachel perceived Amanda—a visual anthropologist with no specific expertise in educational research—to be entering the early years classroom perfectly primed to work in uncertain, barely formed, and provisional ways. From Rachel’s perspective Position of Child felt like a nomadic and treacherous method in requiring Amanda to infiltrate the world of the nursery classroom, sitting with peers on the carpet, finding companions in the sandpit, dressing up with allies in costumes, making sellotape bangles to wear and holding hands as she ran and jumped with peers, becoming caught up with, and composed by the forces of movement and rest that pulsated through the collective bodies in and of that world. She was affectively unmoored but equally unsettling to the adults around her.

As a space of methodological potential saturated with changing relations, and seeming to suggest transgression of the conceptual and physical boundaries of child and adult, Position of Child could consequently be seen as steeped in the affective charges of “wrong-doing” and being a “bad” researcher. In composing oddness as a problem, the separation between different social categories were blurred in ways that treated truth, as Lury suggests, “not as an empiricist absolute certainty,” (cited in Tironi, Citation2020, p. 80) but as a claim to knowledge in a self-referential system that cannot be entirely validated outside itself. Yet this messy methodology-in-practice was also teeming with potentialities to undergo and correspond with the affective atmospheres, murmurative flows, and vital rhythms of that collective world, as Childers et al. (Citation2013) propose, always already being ahead of what we thought it was.

Attune, undergo, correspond—promiscuous affectivity in action

It is 8.45 a.m., and we (Amanda and Rachel) are standing in line at the classroom door alongside other children, parents, and carers, awaiting the arrival of the teacher. The nursery classroom is open plan, a largely self-directed environment, with indoor and outdoor areas, facilitating climbing, running, scooting, messy play, sand and water, and dressing up. It also has more obviously pedagogical provisions, such as a reading corner and number area.

Amanda, quickly absorbed into the fascia-like system (Weig, Citation2020, p. 94) of nursery teacher, teaching assistants, children of three to four years of age, parents, occasional visitors, classroom spaces, rhythms and materialities, experiences nursery as an incalculable body of moisture, at times terrifyingly turbulent with nothing to cling on to, at others mesmerizingly suspenseful, an underworld kelp forest in which teachers’ legs and shoes, children’s faces, hair bows, and gestures loom towards her, hallucinatory and out of scale with her prior, habituated, adult positioning. Rachel, the researcher in carer/parental role, observing the daily wayfaring of Amanda in Position of Child traduces in her colleague the daily incursion of a “nomadic, dispersed, and fragmented vision” (Braidotti, Citation2006, p. 4).

Each day, at regular intervals, the teacher gathers the children together to sit on a small carpeted area near to her desk, whether to listen to a story, introduce a visitor to the classroom, or while she takes the register. The collective of bodies overspills the carpet area, with some children sitting on the uncarpeted floor, some choosing middle or marginal areas, whilst others are eager to sit right up close to the teacher’s legs. The carpet and its surrounds are a zone often pulpy with clandestine movement, prodding, flicking, and daydreaming.

The pre-composed teacher role of sitting above, overshadowing events, uses the carpeted area as a pedagogical vehicle; driven by an impetus to talk with the children, it is a place to concentrate bodies, focus attention, and gather minds to minimise distractions, a head-led place of rationality that from its middle areas “subtract[s] from the fielding of much richer events… rarely acknowledged” (Manning & Massumi, Citation2014, p. 12). Like the microbiome in the synthetic pile of the carpet, a great deal of what happens in the place where children listen to what the teacher has to say is invisible to the seated adults looking down.

Without volition Amanda’s everyday heady awareness gives way to a vegetal consciousness, “a mode of receptivity that acknowledges without rushing to judge, that listens without filtering the sounds through conventional standards of good and bad.” (Bennett, Citation2020, p. 93). In Position of Child the experience of sitting on the carpet with her peers is profuse with reverie, oddness, and awe. It is where her out-of-kilter body sits still, towering above, out of scale with those who surround her, her body an obdurate reminder of being odd—too large, too compliant—the oddness paradoxically allowing her to persist in a state of necessary undoing. In one moment, Amanda is drawn into what her “senses are compelled to attend to” (Mukhopadhyay, in Manning & Massumi, Citation2014, p. 13), as the middle gapes as both huge looming assaults, and exquisite miniature fabulations.

Spitting open the sky—eruptions of difference

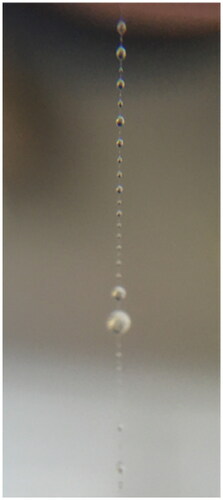

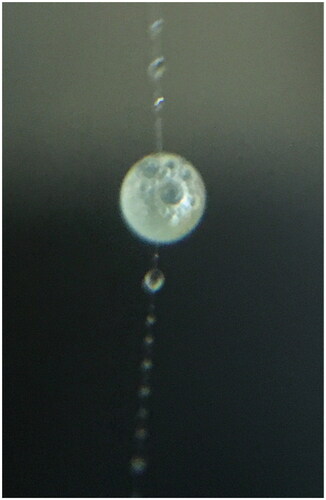

He is sitting next to me on the floor. Our nursery teacher is talking but I am not concentrating on what she is saying. We: me and him, in this other place, spun together through saliva, spittle. A few seconds ago, he put his finger and thumb to his mouth and now he is moving it around in his hand, stretching its slippery elasticity into a bouncing string. The substance pools into bubbly globs that slide and shake along an ever-thinning line. He holds my eyes with his gaze, dispassionately, but with such steadiness it feels conspiratorial. His eyes flick towards our teacher, then return with unstudied neutrality. He does not draw attention to himself (Ravetz, extract from the field, 2018) ().

On the carpet, this child has chosen several times over the last two days to sit next to the new person Amanda, bigger than others, dressed the same in yellow shirt and grey trousers. Amanda registers the nursery teacher talking. Her voice, almost indistinguishable, reverberating with impedance, says something about a surprise visitor and sports day. Amanda’s attention is swampy. She is absorbed by the child’s interest in his interlaced fingers amidst the tiny lines of thread, edges of grit, and stars of colour amongst the carpet’s pile and the spit he is impersonally yet intimately producing.

The child and the researcher in Position of Child are folded into a web-like skein, camouflaged, their apparently orderly bodies allowing them to somehow disappear as if they are functioning unproblematically (Curtis & Biran, Citation2001). They have inculcated and abide by the rules of classroom culture, sitting calmly, not fidgeting or talking, impersonating attentiveness. But under cover of this simulacrum the child’s uncontainable body oozes its unruly desire to secrete, spitting out its excess. With deep fascination, he is mesmerised by (t)his materiality, the warm oral leakages, and movements of saliva’s unique qualities.

He holds her gaze, holds himself open in this slimy and wildly disorganising matter. Suspended and lingering, their connection is characterized by oddness, subversion. Deposited in the middle, atmospheric formations coalesce as a fragile moment. Washed up, spat out, buffeted by the relentless tide that carries her and her carpet peers along ().

The spit strung between his fingers playfully improvises across a space of impersonal intimacy formed through their connection with this everyday thing moving between them. Globes of spit run and wind down the string or hang for long moments like tiny worlds before they break and fall. Bound by this viscous “secret capillarity” (Deleuze & Parnet, Citation2007, p. 139), they are no longer straight-forwardly apart, still deciphering the ways they are conspiring with one another. In their resemblance as peers, they menace the stasis (Bhabha, Citation1994) deftly interfering with the process of compliance so coveted by the pre-imposed role of nursery teacher, weakening classroom systems from the inside.

They do not draw attention to themselves. Somehow this salivary transgression remains indiscernible to the teacher and others on the carpet. If noticed, a tissue and a visit to the washroom will truncate the string of planets, the dilation of time, sanitise the undoings, dampen the furtive stain of contamination, and reseal the bounded body. Unnoticed, unimpeded, a dangling thread of conspiratorial exchange emerges full of “secrets that can slide into pockets or come to feel, in themselves, like a pocket or folded interiority” (Seigworth & Tiessen, Citation2012, p. 49). The secrecy surrounding flows and folds of saliva binds them into the slippery interstices of openness and intimacy. In the public space of the carpet, they hide; sensations of closeness and of being un/seen, they both resemble and threaten their surroundings, ebbs, and flows of concealment and disguise. Neither fully perceptible to the teacher’s surveillance, nor invisible, they are shaded into “the secret’s ontology […] forever resid[ing] in a kind of half-light: always partly dimmed or obscured, always partly open or exposed” (Seigworth & Tiessen, Citation2012, p. 50). Amanda and Samuel are strung together in the saliva’s secret capillarity. This fluid life of school exceeds any sense of the individualised and bounded body, as well as refusing the confines of fixed, and coherent developmental theories, systems, and structures that seek to command the child into im/proper pupil. This fluid life of the school is unbodied, existing in the pre-corporeal community, antecedent to school’s hegemonic form (Mason, Citation2020, p. 163).

We suggest that this small but affective event, resembling other small events that adults are present for but rarely present to, far from being explainable or interpretable, “tears open the sky behind the action” (Salzani, Citation2013, p. 273) to produce what Deleuze might describe as “the adding of space to space” (1986, p. 17). Although the spit remains suspended between his fingers, it also takes flight from the dense school assemblage. There is a deterritorialising process of re-arranging, re-organizing, and mis-fitting—the spit potentiates a crack in the school assemblage of bodies and collective enunciations including the school building, its nursery and carpeted area; the colonising curriculum and assessments saturated by political imperatives to catch up and make progress; the system’s civilising project turning young children into socially malleable and economically viable citizens; streams of developmental psychology determining hierarchies of need and normalcy; the hegemony of adult-centrism and incompetent cultural foreclosing that assumes knowledge of, having a voice for, and sharing experiences with those typically infantilised.

The spit’s tiny yet significant flight trajectory, reveals a shift of the school assemblage from one state to another, that made visible plugs into the semiotic, material, and social flows and fantasies of childhood. Spit, as undesirable excessive oral secretion conjures something primitive and wild, whether childhood being understood as a human experience of the wild (Halberstam, Citation2020); or being the wild as a beyond to the structures we inhabit and that inhabit us (Harney & Moten, Citation2013). The spit inhabits a space that refuses the call to order, described by Harney and Moten (following Fanon) as being a space “abandoned by colonialism, by rule, by order” (2013, p. 8). In the present moment, even if imperceptible to the teacher, it carries Amanda and Samuel beyond the boundaries of what is recognised as, or constitutes the pupil or maturing body “proper”, reconfiguring modes of being to lie outside the nursery’s system of easy classification that otherwise nestles adult/child, human bodies into clear categories. The spit, cadenced as primitive, wild, feral, marks a transitional space for dissonant bodies in resistance to conventional ordering of school spaces that are so concerned with “making progress” and “becoming civilized”.

Enfolded with/in the eruption of difference

This event attuned Amanda to the strange ordinariness of the nursery classroom as it enfolded moments of usual orderliness along with a different order of things or dis-orderliness, often below the register of consciousness, but nevertheless affectively felt. As Joss Hands points out, “much sensation that is ‘enfolded’ into the body, in the form of intensity, does not make it into consciousness” (2015, p. 144). This enfolding nevertheless allowed something of the existing order to become partially legible, for example, the relations between adult and child; human and non-human; white, cisgendered researcher and dual heritage British child; bounded bodies and leaking orifices; clock time and duration; focused and swampy attention; head-led logic and bodily sensations; difference eliding and difference differentiating.

The spit event produced a heady and bodily mixture of sensations that, at times reinforced, whilst also undermining such hierarchical binaries that so often shape research and education. The adult-child binary in both nursery and research relationships, for example, has always privileged the adult as older, wiser, adept, self-controlled, and rational. The child has traditionally been perceived as younger, lacking, not as competent, and less knowledgeable. However, in Position of Child the anomaly of growth became enfolded into the experience. Amanda recalls her peers’ reflections on her body’s profusions, kinship, and anomalies—“why are you too big?”, “I can see your baby hair”, “Is that your Mummy? (referring to Rachel)”, calling into question how the relationship between physical size and age, age, maturation, and development are understood. Inside the spit event, Samuel’s steady assuredness that held Amanda’s gaze and interest so competently lured her curiosity and was, at times disconcerting. He was leading her away from the teacher’s task at hand, playfully enticing and intriguing in his manner, she willingly drifted with him into a different order of things. Amanda’s patient attending-to and waiting-with Position of Child gave access to a different world of a young child which was far less bound by goals, borders and foregrounded the importance of trying affective approaches that are steeped in rigorous ethical safeguards but nevertheless might cause unease. Her willingness to go with the flow, stay in the middle, and resist the rush to read events, afforded a space to hold open such anomalous moments that unsettled the habitual time-sensitive and adult-led pedagogies as well as researcher/participant divide. As Erin Manning reminds us, Samuel was not

an empty vessel hoping to be filled by content devised by adults. Nor is [he] a neutral entity moving along a pre-constituted developmental path. [He] is a researcher of life, and a maker of worlds. The indefinite runs through [him], protecting [him] from the frames we so eagerly wish to impose on [him] … [often he] knows something the adult has not yet attuned to, too concerned, as is often the case, with the presumed overlay of content and form (2020, pp. 7–8).

Lubrication and viscosity as concepts in (“bad”) research

Claire Colebrook points out that “A concept is not a word; it is a creation of a way of thinking” (Citation2002, p. 20, cited in Kuby & Murris, Citation2021, p. 44). This final section will explore the usefulness of saliva or more specifically its properties of lubrication and viscosity as a way of thinking when put to work alongside Position of Child. Particularly how saliva’s viscosity enabled Amanda to attend-to and wait-with the event, holding her place as peer in the nursery, steered carefully by her own established rules, whilst its slippery consistency lubricated the connections between this transgressive methodology with its ambivalent relationship with what might take on an appearance of “bad” research, and theory and practice.

Saliva’s viscosity as well as its lubricating features, produce both inhibitory and enhancing functions in the mouth (Vinke et al., Citation2020, p. 4019). Saliva’s properties help to limit, prevent, enhance, aid, and facilitate. The approach we have referred to as Position of Child could be perceived as an ethically unsettling methodology that both inhibits and enhances; it risks reinscribing power-relations already at play—in this instance between adult researcher and child pupil, whilst promising a fluid and affirmative approach, augmenting a body’s capacity to do, say, and think according to an immanent mode of existence, fostering deeply ethical interactions with a young child.

The process of being in/with Position of Child released Amanda from her over-coded adult researcher habituations of perception and action, as she experienced some of the qualities of being a child, and in so doing manifested otherwise suppressed potentials. In its strangeness Position of Child pressed upon the ethical research principal to “do no harm”, surfacing anxieties and possibilities of being co-opted into problematic endeavours. For example, as method, by cultivating trusting familiarity with a group of children, many drawn from a range of cultural backgrounds outside of Amanda’s white, middle-class identity and lived experience, Position of Child could be viewed as a play of pretence and seduction to gain allies without open acknowledgement of, or reflexivity about power differentials. As a method, it carried traces of the potentially problematic relational ethics that have been routinely ground into the fine grain of method and the fibres of researcher habits that inadvertently reinscribe research hierarchies and power differentials, subversive opportunities to exploit, manipulate and coerce.

However, enfolded into the process of Position of Child was a carefully considered mixture of rules that contained and organised the more nomadic, free flowing space of the lived experience of Amanda in the nursery. These rules intertwined fixed and variable elements, producing an order to the experience whilst still enabling intense and affective events, such as the spit-event described here, to emerge. Drawing on the Deleuzo-Guattarian concept of becoming-child, we can see this as an instance of Amanda finding new connections, sharing ineffable sensations with Samuel, eroding something of research’s well-defined body of methods, as well as school’s governing apparatus, both dependent on some degree on more usual adult/child positions. Drawing on Markus Bohlmann’s use of becoming-child in Deleuze and Children (2020), Amanda did not stop being an adult and Samuel did not stop being a child at this moment. They did engage however in a dispersion of intensities and energies that transformed them both, becoming “a ‘unit’ of ‘child-ness’…” (2020, p. 183). In Position of Child, Amanda was “steered out of her sedimented and enclosed selfhood” (p. 185), contagiously flowing in relation to/with Samuel, feeling a quality or sense of child-ness and finding herself continually being composed, decomposed, and recomposed. Amanda was not engaging with Samuel and the spit as authoritative figure, someone who might somehow halt or question the interaction or re-instantiate nursery hygiene rules. She was attending-to and waiting-with the event, as its affectivity unfolded into the space of the carpet, alive from the middle of things.

Following MacRae and MacLure, she was attending carefully to “the unfolding dynamics of events”, which as they point out,” gives methodological substance to Tim Ingold’s image of observation” (2021, p. 278) where “waiting upon things is precisely what it means to attend to them” (Ingold, Citation2014, p. 389). It is fair to say that Position of Child was not needed to foreground the presence of such material events that regularly erupt into the order of the nursery, as so many teachers and researchers are already cognisant of these. However, the practice of waiting-with the eruption as it unfolded awkwardly, attending-to its intensity, allowing herself to be carried and affectively engaged, enables us to question what is overlooked by more typical research methods or teacher meaning-making practices that rush to respond to disturbances in particular ways. What is afforded if the usual status of things, meanings, significations become unsettled? Rather than this being interpreted as an interruption that needs quelling via a ready-made response in the inevitable restoration of order in the nursery, Amanda remained enthralled to the event, experiencing it as an eruption of difference, as she stayed awake to how it was always “on the cusp of continual emergence” (Ingold, Citation2014, p. 389, cited in MacRae & MacLure, Citation2021, p. 278).

As a researcher with a focus on how difference emerges, or erupts into spaces like school that typically encourage conformity, Vivienne Bozalek and Weili Zhao point out how ethically challenging it is to reject views of difference “as abject or pejorative to be avoided or overcome” and instead encounter it “as something affirmative” (2021, p. 52). Perhaps this transgressive approach, experimental in its intention whilst grounded in rigorous ethical decision-making processes, theoretical ideas of undergoing and artistic research, offered a different space to wait-with difference. Position of Child was about participating in the school’s nursery context by way of sensation, an ethics of affirmation, and practice of working with forces of intensity, lines of movement, presence, and values that did not foreclose the possibilities and potentialities of complicity in the act of becoming-child. By not conforming to the usual expectations of classroom order, being momentarily dis-possessed of their “proper pupil” (and “proper researcher”) selves, Samuel and Amanda waited-together-with the event as it unfolded. In the middle of this waiting-with, we note Samuel’s confidence, knowing the ways the teacher kept order and the delicate ways he might subvert this; his ongoing and intensive interest in the properties, and affordances of bodily seepages in spite of his chronological age and associated expectations; his competent skills sustaining eye contact and holding attention, enticing interest, non-verbal communication and ways to captivate.

Rather than a fixed method, Position of Child emerged as an improvisational, compositional practice. Lisa Mazzei proposes that the method often has a script; participant observation for example is inscribed with a mental and even embodied map outlining ways to carry out the basic approach, identifying its temporal and causal relations. Whereas process methodology she suggests, foregrounds the need to undo a researcher’s associative chain of actions to allow for ways of innovative doing and new thinking to emerge, often “happening in the middle of things, in the threshold” (2021, p. 198). Position of Child’s ethical instance with Samuel and the spit was located in ongoing relationality and duration, engaging more immanently with what Guattari (Citation1995) might describe as the affective in situ, or in Baradian terms, “the complicity inherent in affectivity—the ability to affect and be affected” (Christie, Citation2020, p. 133).

We are proposing here that multiple lines of flight happen but are so often obscured from adults by their own adult preoccupations with goals, school protocols, ethical norms. Children in the kelp forest body-think otherwise, act from an ethics of presence, pursue attending-to and waiting-with. This can be felt and perhaps conceived of as wild, and slippery as spit; this is part of children’s capacity, lived experience, ways of knowing, and learning. Of course, we need to be mindful not to use “bad” research as superficial currency, nor imagine it is possible to erase power imbalance and other kinds of problematic difference, given their utter entrenchment. But we also need to go beyond conventional thinking about what is assumed to be “good” research—with its taken-for-granted quality that re-produces the status quo, confirming an existing knowledge hierarchy—and what is “bad” research—something tolerated at the margins, contesting the nature of knowledge, questioning truth and unsettling rationality. This paper goes some way in opening up this dichotomy, not by establishing scripts for “new” methods that may, in turn, solidify into other preoccupations or habits that obscure the more-than what actually becomes visible, tangible, or audible, but by producing accounts of undergoing so that the experiencing of difference can slip and slide out with the writing as it does from the classroom always already alive with the more-than.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rachel Holmes

Rachel Holmes is Professor in the Education and Social Research Institute, Manchester Metropolitan University. Holmes co-leads ESRI's Children and Childhood Research Group and has authored numerous studies of early childhood education.

Amanda Ravetz

Amanda Ravetz is Professor Emeritus, Manchester Metropolitan University. Ravetz's work explores the interdisciplinary connections between anthropology and art/design, and theories and practices of observational cinema. She is the author (with Anna Grimshaw) of Observational Cinema (2009) and co-editor of Collaboration Through Craft (2013).

References

- Barker, B., & Mills, C. (2018). The psy-disciplines go to school: Psychiatric, psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches to inclusion in one UK primary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(6), 638–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1395087

- Bennett, J. (2020). Influx & efflux: Writing up with Walt Whitman. Duke University Press.

- Bhabha, H. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Bohlmann, M. (Ed.). (2016). Misfit children: An inquiry into childhood belongings. Lexington Books.

- Bohlmann, M. (2020). Deleuze, children and worlding. In M. P. J. Bohlmann & A. Hickey-Moody (Eds.), Deleuze and children. Edinburgh University Press.

- Bozalek, V., & Zhao, W. (2021). Difference. In K. Murris (Ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 52–54). Routledge.

- Braidotti, R. (2006). Transpositions: On nomadic ethics. Polity Press.

- Childers, S. M., Rhee, J., & Daza, S. L. (2013). Promiscuous (use of) feminist methodologies: The dirty theory and messy practice of educational research beyond gender. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(5), 507–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.786849

- Chantler, S. (2013). ‘Is this inclusive?’; Teachers’ perspectives on inclusion for children labelled with autism [Doctoral thesis]. Sheffield Hallam University. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (shu.ac.uk).

- Christie, A. (2020). “Flying at our hand”: Toward an ethics of intra-active response-ability. Configurations, 28(1), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1353/con.2020.0004

- Colebrook, C. (2002). Gilles Deleuze. Routledge.

- Curtis, V., & Biran, A. (2001). Dirt, disgust and disease: Is hygiene in our genes? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 44(1), 17–31.

- Davis, B. P. (2019). The politics of Édouard Glissant’s right to opacity. The CLR James Journal, 25, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.5840/clrjames2019121763

- Deleuze, G. (1986). Cinema 1: The movement image (H. Tomlinson & B. Habberjam, Trans.). Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Parnet, P. (2007). Dialogues II (H. Tomlinson & B. Habberjam, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

- Grimshaw, A., & Ravetz, A. (2009). Rethinking observational cinema. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 15(3), 538–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01573.x

- Guattari, F. (1995). Chaosmosis: An ethico-aesthetic paradigm. Power.

- Halberstam, J. (2020). Wild things: The disorder of desire. Duke University Press.

- Hands, J. (2015). From cultural to new materialism and back: The enduring legacy of Raymond Williams. Culture, Theory and Critique, 56(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735784.2014.931782

- Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The undercommons: Fugitive planning and black study. Minor Compositions.

- Ingold, T. (2014). “That’s enough about ethnography!” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4(1), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau4.1.021

- Irwin, R. L., Springgay, S., & Wilson Kind, S. (2005). A/r/tography as living inquiry through art and text. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(6), 897–912.

- Kuby, C. R., & Murris, K. (2021). Concept. In K. Murris (Ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 44–45). Routledge.

- Lury, C. (2021). Problem spaces: How and why methodology matters. Polity Press.

- MacRae, C., & MacLure, M. (2021). Watching two-year-olds jump: Video method becomes ‘haptic’. Ethnography and Education, 16(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2021.1917439

- Mandall, N. (1988). The least-adult role in studying children. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 16(4), 433–467.

- Manning, E. (2013). Always more than one. Duke University Press.

- Manning, E. (2020). Radical pedagogies and metamodelings of knowledge in the making. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 8(SI), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v8iSI.261

- Manning, E., & Massumi, B. (2014). Thought in the act: Passages in the ecology of experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mason, E. C. (2020). Thing: A fugitive in()operation. Journal of Italian Philosophy, 3, 163–189.

- Mazzei, L. (2021). Postqualitative inquiry: Or the necessity of theory. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 198–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420932607

- Moten, F. (2014). (In conversation with Saidiya Hartman) Fugitivity & Waywardness – EPISODE 6: Make a way out of no way, Tramway and in Stereo, Glasgow. https://vimeo.com/151775530

- Rotas, N., & Springgay, S. (2014). How do you make a classroom operate like a work of art? Deleuzeguattarian methodologies of research-creation. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(5), 552–572.

- Salzani, C. (2013). In a Messianic Gestire: Agamben’s Kafka. In B. Moran, C. Salzani, & P. Alberts (Eds.), Philosophy and Kafka. Lexington Books.

- Schneider, A., & Wright, C. (2005). Contemporary art and anthropology. Taylor & Francis.

- Seigworth, G. J., & Tiessen, M. (2012). Mobile affects, open secrets, and global illiquidity: Pockets, pools, and plasma. Theory, Culture & Society, 29(6), 47–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276412444473

- Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary affects. Duke University Press.

- Takala, P. (2005). Retrieved March 22, 2022, from https://pilvitakala.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/event-on-garnethill.pdf

- Tironi, M. (2020). The social life of methods as epistemic objects: interview with Celia Lury. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from Entrevista_a_Celia_Lury_Celia_Lury_inter.pdf

- Vinke, J., Kaper, H. J., Vissink, A., & Sharma, P. K. (2020). Dry mouth: Saliva substitutes which adsorb and modify existing salivary condition films improve oral lubrication. Clinical Oral Investigations, 24(11), 4019–4030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03272-x

- Warming, H. (2011). Getting under their skins? Accessing young children’s perspectives through ethnographic fieldwork. Childhood, 18(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568210364666

- Watson, K. (2016). Inside the ‘inclusive’ early childhood classroom: the power of ‘normal’. Peter Lang.

- Weig, D. (2020). Fascias: Methodological propositions and ontologies that stretch and slide. Body & Society, 26(3), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X20952138

- Wolff, S. (1995). Loners: The life path of unusual children. Routledge.