Abstract

Indigenous Australian young people comprise over 50% of the total Indigenous population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017). Yet, the voices of Indigenous young people are seldom centred in policy or scholarship (Shay & Sarra, Citation2021). This paper shares findings from a three-year national transdisciplinary, qualitative study that explored the identity and well-being of Indigenous young people in diverse school settings. The data told counter-stories through the lens of Indigenous young people currently absent in mental health and educational wellbeing scholarship. This article illustrates how the theoretical/methodological approach and data provide a strengths-based alternative to trauma-informed and medicalised mental health frameworks that dominate policy and practice approaches. This paper shares key findings from Indigenous young people who articulated their identities as underpinned by respect, pride and collectivism and shaped by culture, where you are from, physicality and role models. These expressions are clearly at odds with broader deficit discourses on Indigenous identity and have implications for health and schooling settings.

Introduction

There is increasing demand for research and policy to include the voices of young people on issues that affect them (Bassett & Geron, Citation2020). Listening to young people’s experiences, visions, and aspirations is critical when authentically engaging with and understanding a broad range of issues concerning young people (Faircloth et al., Citation2020). Researchers globally have emphasised the need for more participatory approaches to balance the power dynamics between researchers and young people to elicit better data (Lohmeyer, Citation2020). However, when working with minority youth voices, local sociocultural issues can emerge that prompt the need for researchers to deeply consider epistemology and ontology (Kidman, Citation2014).

As researchers, we must position ourselves within the research we are reporting on. As the study was undertaken with Indigenous Australian communities, our lens and positionality must be stated upfront. Author one, Shay, is an Aboriginal researcher whose family is from Wagiman Country in the Daly River region in the Northern Territory of Australia. Author two, Sarra, is an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researcher of Aboriginal heritage from Bindal and Birri clan groups of the Birrigubba nation and Torres Strait Islander heritage of Mauar, Stephen and Murray Islands. Author three, Proud, was born and grew up in the community of Cherbourg and is a Koa and Kuku Yalanji Elder with extensive experience in early childhood and prison education. Author four, Blow, is a Wakka Wakka woman with extensive experience in community and education and has worked on multiple research projects in her community as a research assistant. Author five, Cobbo, is a Wakka Wakka man trained in community development who also has extensive experience in education and has worked across multiple research projects in his community.

Aboriginal people (mainland Australia) and Torres Strait Islander people (cluster of islands off the northern tip of Queensland) are Indigenous and first peoples of Australia. We recognise the diversity of the many Aboriginal nations and acknowledge that the term Indigenous is an imposed term used to homogenously label people throughout the colonial project in Australia. Using the fictional legal term “terra nullius,” a Latin word that means “empty land” (Reynolds, Citation1996), rendered Australia’s first people inhuman from the earliest contact with the colonisers. The discourse of terra nullius influenced many policies affecting Indigenous Australians over the past 250+ years. Despite this, the Australian Government now recognises that Indigenous peoples have lived in Australia for at least 60,000 years and are considered the oldest surviving culture in the world (Sherwood & Geia, Citation2014). Indigenous people in Australia are now considered a minority, making up just over 3% of the total population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018). Australia’s colonial history has impacted how Indigenous peoples and voices are represented in political, social, and cultural discourses. Although this paper focuses on the voices of Indigenous young people, we must contextualise the findings by summarising how Indigenous identities in Australia have been constructed and perceived.

Not so black or white - Indigenous identities in Australia

There are many complexities in researching identities. The scholarship on identities is differentiated through the conceptual and theoretical lens of the researcher undertaking the study, resulting in diversity in how the term identity is defined, researched, and analysed. Identity can be explored and understood through anthropological, psychological, philosophical, biological, and sociological underpinnings (Elliot & du Gay, 2009); however, many of these epistemes stem from Western ways of being, knowing, and doing. Indigenous researchers have recently broken the myths of intellectual inferiority and primitivity that persisted throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Moreton-Robinson, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2019). Smith et al. (Citation2019) explains that the Indigenous research agenda is primarily concerned with strategic shifts in achieving self-determination and social justice, and this will be achieved through a framework of ethics underpinned by Indigenous protocols and interests.

With the recent inclusion of Indigenous produced scholarship, a new wave of knowledge has surged. For centuries, Indigenous people were subject to the “colonial gaze” (Paris, Citation2019) as colonial projects operationalised worldwide. Australia’s colonial histories bear many similarities to the experiences of Indigenous peoples globally; however, the myth of terra nullius (and therefore the absence of a treaty with Australia’s First Peoples) and the power of its influence historically, ideologically, culturally, and socially has weighed heavily on how Indigenous identities have been perceived, constructed, (re)produced and (re)presented, particularly by non-Indigenous peoples.

Brough et al. (Citation2006) outline the propensity of non-Indigenous Australia to apply binaries when understanding Indigenous identities, purporting that unless they fit neatly into a black or white binary, they are often perceived as not genuine. Indigenous peoples have rejected these constructs despite superficial understandings of Indigenous identities, conflated with colonial ideologies, ideals, and discourses. We have also actively sought to analyse what would motivate such mistruths critically. For example, in the early 1990s, Dodson (Citation1994) posed the question: “If the images of Aboriginality do not reflect us, it is not actually about us; what purpose have they served for those who constructed and adopted them?” (p.12).

The way that Indigenous identities are constructed contemporarily is intimately intertwined with the past (Bolt, Citation2010). The doctrine Terra nullius (empty land) assists in understanding the consequent Indigenous identity constructs. An initial focus on the total decimation of Indigenous peoples in the early stages of colonisation (through poisonings, massacres, and other means) progressed to many variants of categorisations that used the concept of blood quantum (connected to the pseudoscience of eugenics as a marker for how Indigenous people were to be categorised and managed legislatively) (Carlson, Citation2016; Weaver, Citation2001). These categorisations highlight how Indigenous people are commonly defined and represented; however, they starkly contrast with how Indigenous peoples talk about identity (Sarra, Citation2011).

Indigenous voices on Indigenous identities

Indigenous voices on identity are at odds with the constructs proffered in the literature and those created socially, politically, and culturally by non-Indigenous Australia. Bodkin-Andrews and Carlson (Citation2016) explain that understanding Indigenous identity means understanding how diverse Aboriginal peoples are, shifting away from notions of pan-Aboriginality; a concept that assumes homogeneity of Indigenous peoples. Dodson (Citation1994) argues Indigenous peoples must define ourselves, because of the mistruths and stereotypes perpetuated in our absence and because these are our stories to tell.

Although there is no consensus of definitions on Indigenous identities (Weaver, Citation2001) and no simple way to explore the issue, there is an emerging body of literature on how Indigenous adults talk about identity. In a study about Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal perceptions of Aboriginality, Sarra (Citation2011) investigated how both groups talk about Aboriginal identities. The results revealed the relevance of standpoint and cultural locations in defining identities and lived experiences of such realities. Non-Aboriginal participants (or what Sarra terms as mainstream perceptions) prevalently used the following adjectives to describe Aboriginal people: alcoholics, boongs, niggers, and many other highly racist terms, lazy, uneducated, welfare-dependent, dirty, good dancers, unreliable, aggressive, and good sportspeople. Divergence was distinct when Aboriginal participants responded to similar questions about their perceptions and experiences of being Aboriginal. While the participant cohort was far smaller, Sarra (Citation2011) used story and thick descriptors from Aboriginal participants to form an understanding of how Aboriginal peoples in this study conceived and expressed their identities. The results revealed that Aboriginal participants reported strong feelings about “being” Aboriginal; there was a strong sense of pride, respect for Elders, families, ways of connection, connection to Country, and spirituality.

Urban Indigenous identities within Australian adult populations are increasingly focused on in literature. Despite beliefs that Indigenous peoples mostly live in regional and remote areas, the 2016 census data revealed that 79% of Indigenous Australians now live in urban contexts, which explains the focus of the literature on urban identities (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017). Brough et al. (Citation2006) undertook a qualitative study exploring social capital in an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander context. Using focus groups and in-depth interviews, the authors found that family and community connections appeared to be what they described as “the primary sources of bonding social capital” (p. 396). Participants in this study spoke of a two-world construct, referring to feeling caught between an Aboriginal world and the mainstream. This was a source of stress for some participants, but their connections to their culture and Country appeared to be a vital aspect of their identities. Racism was also an issue for some participants in this study, despite recognising that cities sometimes provided more racial anonymity than regional areas.

Carlson (Citation2016) also investigated the concept of contemporary Aboriginal identities, exploring the politics of who counts as Aboriginal. Carlson (Citation2016) outlined the deep complexities and nuances that occur in identifying as Aboriginal, particularly when it comes to the Government’s three-part definition of who is defined as an Aboriginal person: that the person is of Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander descent; that the person identifies as such; and that their communities recognise them as being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. The latter can cause huge issues for people who meet the first two criteria. If a person needs to access government services designated explicitly for Indigenous people, a person will usually need to provide a “Confirmation of Aboriginality” certificate (Carlson, Citation2016, pp. 131–133). These certificates are provided by local Indigenous organisations, such as Land Councils, as they are tasked with navigating all the complexities and granting a person’s status as Indigenous, which has emotional, social, and material significance.

How are Indigenous young people talking about identity? Existing research

The voices of Indigenous young people must have a platform to express their identities. Australian Indigenous people are a young population. The 2016 census data reveals that more than half of Indigenous people, 53%, are under 25 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017), demonstrating the importance of ensuring young people have a platform for their voices to be heard – they are our future Elders and custodians. A national mentoring program, AIME (Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience), supported a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people at a recent annual cultural event to deliver a statement named “The Imagination Declaration,” an articulate call to education ministers, governments, and broader Australian society to listen to Indigenous young people, to expect the best from them, and to understand that they “are not the problem, they are the solution” (Shay et al., Citation2019). The statement indicated that Indigenous young people have felt voiceless when labelled the most educationally disadvantaged group in Australia (Beresford, Citation2004; Tripcony, Citation2000). The lack of literature that provides Indigenous young people with a platform to be heard attests to the lack of Indigenous young people’s voices on topics such as identity.

Shay and Sarra (Citation2021) undertook an Indigenist analysis of the research literature in Australia that included the topic of identity and focused on data directly from Indigenous young people in health and education. The analysis revealed that only fourteen studies met these criteria, with many of the studies using interviews as the primary methods for data collection. The studies were too broad to generalise themes or findings. Still, it was clear across the research that Indigenous young people see culture and identity as essential to their wellbeing. Shay and Sarra (Citation2021) concluded that minimal studies centred the voices of Australian Indigenous young people on identity across the health and education literature, outlining that there was not enough data to theorise Indigenous youth identities in contemporary contexts. They also identified that most studies were undertaken by non-Indigenous researchers using primarily western methods of interviews and surveys to explore the issue, which has the potential to reproduce colonial hegemonies and imaginings of Indigenous young people, as is outlined in the literature on Indigenous identities in adult populations.

Connections between identity and “mental health”

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Citation2009) defined social and emotional wellbeing for Indigenous Australians as broad and holistic, moving away from medical models of mental health to reflect Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing. Increasingly, social and emotional wellbeing are being used in place of terms such as mental health to incorporate policy and program responses to health that recognise social determinants of health such as institutional racism, social and economic inequality, colonialism, and access to education (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022).

The Australian Government recognises that “Culture and cultural identity are critical foundations of a person’s social and emotional wellbeing and capacity to lead successful and fulfilling lives” (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022). The evidence supporting connections between culture, identity, and wellbeing for Indigenous people globally has been increasing. For example, Dockery (Citation2012) outlined the data demonstrated that Indigenous people with stronger affiliations with their “traditional” culture were connected to more favourable socioeconomic outcomes, thus stronger engagement with education and employment. Further, a systematic review by MacLean et al. (Citation2017), of whether interventions that focus on the expression of cultural identities are connected to measurable improvements in health and wellbeing for Indigenous peoples, found that most studies showed strong evidence that the inclusion of identity expression can have beneficial effects on wellbeing.

In more focused research on Indigenous youth, the literature is limited. However, in an empirical study by Williams et al. (Citation2018) in Aotearoa, New Zealand, that examined connections between cultural identity and mental health outcomes for Māori young people, the evidence showed that “Māori youth with strong cultural identities were more likely to experience good mental health outcomes” (p. 1). In Australia, the Report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adolescent and Youth Health and Wellbeing by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Citation2018) outlined that Indigenous young people overall are in good health. However, some aspects of Indigenous young people’s health require action, one of which is mental health. In an earlier publication about the study discussed in this paper, Shay and Sarra (Citation2021) demonstrate that national studies exploring connections between Indigenous youth identity and wellbeing are scarce, meaning there is no published evidence to provide strong correlations between identity and wellbeing. However, the lack of evidence is not because studies are disproving the connections. Instead, there has not yet been an investment in research to explore this aspect of Indigenous youth wellbeing.

Indigenous peoples globally “appear to experience better health and wellbeing where cultural practices have been maintained” (MacLean et al., Citation2017, p.309). Although a solid evidence base does not yet exist within Australia about Indigenous youth, it has been established that cultural identity has strong associations with wellbeing (Dockery, Citation2012). Therefore, we have attempted to contribute to building this evidence base through the data from Indigenous young people in this study.

Our study

The reported findings are part of the three-year funded study “Our stories, our way: Cultural identities and health and well-being of Indigenous young people in diverse school settings.” The project aimed to privilege the voices of Indigenous young people to explore how young people were representing their identities and how their perspectives on how identity connects with health, wellbeing, and school engagement. By investigating the importance of cultural identity to health, well-being, and diverse school settings, co-constructed spaces were created to allow young people time, space, and a safe environment to explore these concepts. This project explored a range of elements and considered cultural determinants of health, including: self-determination; freedom from discrimination; individual and collective rights; freedom from assimilation and destruction of culture; and connection to and custodianship of Country (The Lowitja Institute, 2014).

The research team worked with 110 Indigenous young people across six urban, regional, and remote schools and communities in the States of Queensland and Western Australia. The findings reported in this paper report on data from 5 of these sites and focus on one of the critical research questions set out at the beginning of the project: how are Indigenous youth representing their identities? We will present a case for a more holistic understanding of mental health in education by analysing Indigenous young people’s data on identity.

Theoretical lens

The study draws from the Funds of Identity (FOI) Theory that originated from the scholarship on Funds of Knowledge (FOK). Funds of Knowledge theorise skills and extant knowledge that students (particularly of minority backgrounds) bring from their home and community contexts (Esteban-Guitart & Moll, Citation2014; Hogg, Citation2011). FOK and FOI were developed as an alternative to the pervasive deficit discourses produced in research that focused on culture and difference as a cause of student underachievement (Hogg & Volman, Citation2020). A limitation of FOK is that it privileges the voices of adults - teachers, parents, carers, and community members (David, Citation2016), and lacks student insights and rich data (Gonzalez et al., Citation2005).

FOI is instead concerned with students’ lived experiences and stories regarding their understandings and expressions of identity (Gonzalez et al., Citation2005). FOI positions identity from a sociocultural (Vygotskian) and ecological (Bronfenbrenner) framing (Esteban-Guitart, Citation2016) that allows identities to be understood as fluid, complex, and dynamic (Esteban-Guitart & Moll, Citation2014). FOI aims to counter deficit discourses to build on student knowledge and strengths, providing explicit space for exploring and expressing students’ abilities, competencies, interests, histories, and cultures through the concept of sociocultural identities (Hogg & Volman, Citation2020). Deficit theorising and discourses in Indigenous Australian literature and research are dominant. Thus, a robust theoretical framework was necessary to guide the research design and analysis of the data.

This study focused on Indigenous young people; it was conceptualised by Indigenous scholars and had a majority Indigenous research team. Thus, FOI required a theory that allowed the nature of Indigenous knowledge paradigms to be visible and distinct. FOI works alongside Indigenist Theory (Rigney, Citation2006) which provides three principles to guide Indigenous researchers in contesting scientific discourses and the objectification of Indigenous peoples within knowledge production. Rigney (Citation2006) outlines three principles to frame Indigenous research as resistance: the emancipatory imperative, political integrity, and privileging Indigenous voices. These principles were integral to ensuring the study was grounded in local knowledge and included knowledge holders through the paid appointment of local Indigenous researchers (Shay et al., in press). Furthermore, ensuring the research process honoured local cultural protocols aligned the importance of local research that centres on local culture, histories, and discourses outlined in FOI literature (Esteban-Guitart & Moll, Citation2014).

Methodology

The methodology and methods used in this project were culturally responsive and fit for purpose. They allowed the researchers to employ their professional knowledge and cultural reading of the context to work with participants when gathering data. FOI caution against using interviews and surveys and advocates for techniques such as arts-based methods (Hogg & Volman, Citation2020). Several research workshops were developed using creative ways such as drawing, yarning, painting, videoing, photographing, cooking, and being on Country, all of these methods were utilised to enable young people multiple ways of expressing their opinions and experiences (Stuart & Shay, Citation2018). Yarning is a culturally based way of orally sharing knowledge, stories, and connecting with people (Shay, Citation2019). Yarning, sharing stories and knowledge, was a critical way of developing relationships with research partners (Bessarab & Ng’Andu, Citation2010; Shay, Citation2019). A method called collaborative yarning was used individually and with groups of young people, whereby yarning was utilised to explore the research topics and storyboarding was used to textually record and co-analyse the yarns with participants (Shay, Citation2019). The breadth of the data collection options allowed an extensive range of data to emerge.

Local Indigenous researchers were employed at each site, often male and female researchers, because of cultural protocols and sensitivities. In many Indigenous cultures, there is what is called “men’s business and ‘women’s business, meaning some things would only be shared and discussed amongst women and men separately. It was essential to undertake the research workshops with young men and women at separate times for various topics at some sites. Once the research workshops were completed, the local Indigenous researchers supported the young people in making a creative artefact.

The data was analysed using Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) six-phased model for qualitative thematic analysis. The analysis took an inductive approach whereby the study was focused on developing from the data, and the themes were driven by the data from young people rather than the research questions. However, as the workshop data was shaped around the research question reported in this paper, “how are the cultural identities represented by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in diverse school settings?,” the themes emerged to address this question. In addition to the indicative qualitative analysis, the theoretical principles from Indigenist theory (Rigney, Citation2006) and FOI (Esteban-Guitart, Citation2016; Hogg & Volman, Citation2020) guided the framing of themes and how the research team identified themes.

The data

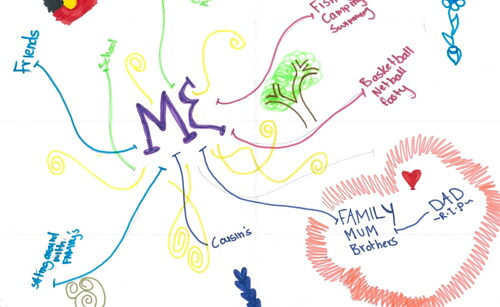

The data reported are from two data sets. The first data set is from a workshop we called “me maps.” Me maps included drawings, text, and symbols from young people about how they described themselves, their cultures, and their identities. This was accompanied by yarning these through with a researcher and the researcher and young people taking notes from the discussion. provides an example:

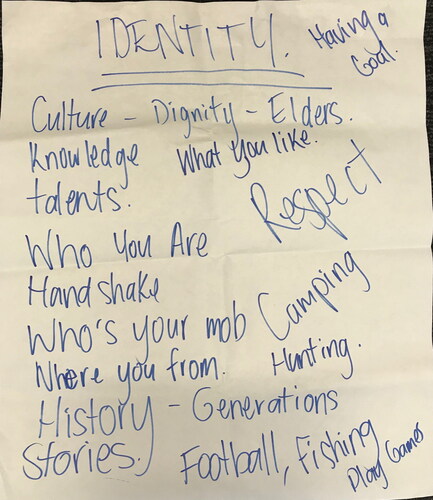

The second data set is from the collaborative yarning storyboards (Shay, Citation2019). Yarning was predominantly undertaken in a group context (often preferred by Indigenous participants). As the yarning developed, textual summaries were recorded onto large paper stuck on the wall. Participants could see what was being recorded, ensure its accuracy, and commence co-analysis with the researchers. The data presented in this paper includes collaborative yarning storyboards from both Indigenous young people and local Indigenous researchers on the project. provides an example of a storyboard:

Results

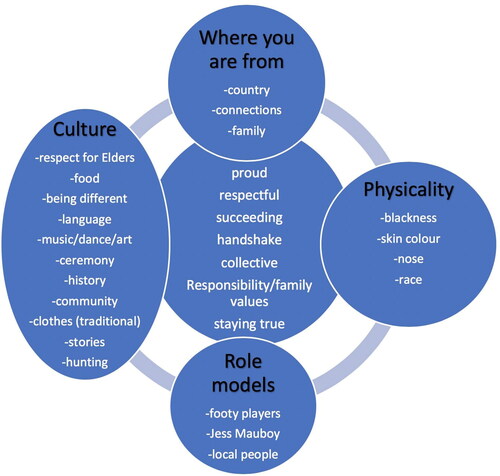

Our analysis revealed that Indigenous young people talk about their identity representations across several dimensions, and these were strongly underpinned by values that surfaced in the data from each site. below provides a visual representation of the key codes that emerged through the analysis, with the values that appear across the data at the centre of the figure. This section will provide key findings from the research under the codes and subcodes that arise from the study.

Theme 1: Values

The theme of values surfaced across all codes. In representing this significant finding, these values and behaviours attributed to values that were frequently discussed in the following codes. Being proud, respectful, responsible, having family values, staying true, and being part of a collective were represented in different ways across the data. The significance of handshakes (which was described in the data from males) and succeeding was significant and is defined here as two behaviours or ways of enacting these values that surfaced so frequently across the data.

Theme 2: Where you are from

The notion of where young people are from surfaced across all data analyses. Where a young person was from did not necessarily mean just in a geographical sense but often meant deeper connections underpinned by relationality (Graham, Citation2014). Country, or place, is used in Indigenous contexts to describe a person’s ancestral homeland. Many young people across the study talked about how their Country represented their identities and how they identify themselves to others. For many Indigenous young people across the project, it was not just about knowing where traditional ties to Country are, even though some young people did not have access to that information. It was about “understanding where you come from” (quote, young person).

In identifying where they were from, young people talked consistently across the project about their connections. These may be with the community they grew up in, other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people they are connected to, or their traditional Country connections. Finally, family surfaced consistently across all sites, strongly connected to where you are from; family connections underpinned the young people’s relatedness to where they came from. The family was recognised as significant to how Indigenous young people identified themselves across the project and their ability to know “who they are.”

Theme 3: Culture

Culture was a strong theme and was articulated by Indigenous young people as a critical part of their identities. Respect for Elders, community, language, and “being different” was mentioned frequently by diverse cohorts as distinct to their cultures and identities. The significance of food, music, dance, art, ceremonies, history, stories, and hunting (for young men) also featured strongly across the data. However, young people in regional and remote communities mentioned hunting and ceremonies more distinctly.

Theme 4: Physicality

The theme of physicality is underpinned by concepts of race and how young people conceptualised racism. Skin colour was referenced across the data; dark skin colour was commonly described as a marker for whether young people would experience discrimination within the school or broader community setting. Lighter skin was also raised as some young people expressed concern about identifying as Indigenous. Nose shape was also mentioned frequently, referencing the raced concept of physical attributes of Indigenous people. Data on nose shape often were connected to discussions about skin colour and race.

Theme 5: Role models

The theme of role models surfaced across data. Indigenous young people described the importance of role models in their understanding and development of their own identities. Of significance in this theme is how crucial local role models were in how young people described their role in identity development. Examples of local role models include Elders, community leaders and knowledge holders, and people from the community who had achieved their goals. Well-known Indigenous role models were predominantly Indigenous football players with public profiles and famous singer, Jessica Mauboy.

Discussion

Identity and wellbeing in schools

The data that young people created and shared in this study provides powerful insights and counter-stories that affect how schools can approach the well-being and engagement of Indigenous students, privileging their strengths and identities. Counter-stories is a term now widely used by minorities globally that ensure the voices of oppressed and minoritised groups are central and amplified in topics that affect them. Brown and Shay (Citation2021) made an empirical case using data from this project and a project based in the United Kingdom for focusing on identity as an alternative to mental health approaches in improving the well-being of children and young people in school settings. The foundation of this proposition is through using data from children and young people themselves who clearly articulated the importance of expression and identity affirmation, particularly for a group such as Indigenous young people who are navigating a system that continuously positions Indigenous education and students within deficit paradigms (McCallum & Waller, Citation2022). These deficit discourses continue to impact Indigenous students’ well-being and mental health (Fogarty et al., Citation2018).

Youth mental health has been a national priority in Australia and many developed countries. As outlined, Indigenous youth mental health has been identified as an area of focus. Yet, there are very few studies that centre on the voices of Indigenous young people in understanding the issues and potential solutions. Indigenous young people in this study expressed the importance of values such as respect for Elders, succeeding, and collectivism. Western approaches that value individualism and that position Indigenous peoples as the inferior “other” dominate even in program and policy settings that are aimed at improving conditions for Indigenous peoples. Thus this data and how the data was collected with Indigenous young people has the potential to reshape current approaches in health and education settings.

Indigenist theory (Rigney, Citation2006) provides a theoretical lens that enabled Indigenous voices and knowledge to frame this study and illustrates the significance of Indigenous ways of being, knowing and doing. Schools continue to be Eurocentric and centred around the cultures of the white hegemony (Paris, Citation2019). Therefore, providing explicit space for Indigenous young people (and the many other minorities in diasporic countries such as Australia) should play an essential role in how schools approach students’ mental health and wellbeing. Indigenous young people in this study talked extensively about the importance of culture, where you are from, role models and physicality. If these perspectives are not present in school or health settings, this cohort of young people is explicitly excluded. The concept of mental health has not reflected Indigenous conceptualisations of health and wellbeing. Thus, unless schools implement programs on a broad scale that enable identity exploration and affirmation, only mainstream models of mental health will be used to approach the well-being of students in schools, likely serving students belonging to the cultural majority.

Counter stories – Indigenous young people speaking loud and proud

The findings reported are at odds with how Indigenous youth are generally represented through a deficit lens socially, politically, and in the media (McCallum & Waller, Citation2022). As outlined, Indigenous identities are contested broadly and Indigenous young people, and the mainstream, absorb these racialised ideas that are entrenched in deficit discourses and do not accurately reflect the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples (Dodson, Citation1994). This research highlights the importance of centring the voices, perspectives, and aspirations of Indigenous young people to ensure knowledge production does not contribute to broader deficit discourses within Australian education settings.

Indigenous young people in this study defined identity as “how you see yourself,” “understanding where you come from,” “being different,” and “representing who you are.” They expressed the importance of knowing where you are from, whose Country you are on, the importance of culture and cultural expression in maintaining strong identities, how physicality impacts identity expression, and the impact of role models in identity formation and development. As the research and literature on identity continue to grapple with such complexities (Elliot & du Gay, 2009), the data demonstrates that Indigenous young people have deep insights as they have had to traverse places like schools where they are in contexts that are not necessarily designed to meet their needs. They are also sometimes met with overt and covert racism. Further studies that centre the voices of Indigenous young people are needed as the data from this study provides new knowledge to a field that often excludes Indigenous young people’s perspectives (Shay & Sarra, Citation2021).

Transdisciplinary approaches and the importance of grounded, local knowledge

This research’s design enabled young people’s strengths and existing knowledge to emerge, supported by local knowledge of Country, community, and connections. The methodological significance of employing FOI and Indigenist theory allowed for transdisciplinarity in exploring wellbeing and schooling experiences through the lens of identity. Providing spaces enabled young people to reflect upon their experiences, share their perspectives, and for diverse forms of understanding and knowledge to emerge. We propose that transdisciplinarity, defined by Wickson et al. (Citation2006) as an “interpenetration of epistemologies in the development of methodology” (p. 1050) is a fusion of epistemologies, theories, and methodologies rather than a mixing of, as seen in multi and interdisciplinary research. Using a transdisciplinary approach grounded in local Indigenous knowledge, led by local knowledge holders, which was unique to each site, allowed for these rich stories and knowledges to foreground the research.

Impact and translation of outcomes are significant for Indigenous research and essential for transdisciplinary research. The employment of local Indigenous researchers provided a mechanism for the products and focus of research to extend beyond the life of the funded research period (3 years). Local Indigenous researcher voices are critical as holistic Indigenous wellbeing incorporates a whole of community approach. Therefore, data from local researchers on their observations of how this research impacted the well-being of Indigenous young people provided a holistic understanding of the research’s impact.

The workshops with the local researchers outlined the way ideas from the project were sustained in their schools and communities to support school engagement and wellbeing beyond the project’s life. One local researcher stated, "the project highlighted to me young people need to know more about their culture and [there are] some gaps in their knowledge.” Therefore, several sites continued to develop cultural and identity-based projects the year after the project finished. Another local researcher said the project had a “big impact on our students. They aim high and want more.” A further observation was that this research “opened opportunities for our young people to take pride in their culture, art, identity – and this may be as a career.” Another practical outcome in one community was the appointment of the first Aboriginal school captain in the school’s 75-year history. In the same school, the development and delivery of the first local Aboriginal language curriculum also occurred after this study, with the local researcher outlining connections in how the project opened opportunities for the growth of Indigenous leadership and embedding Indigenous knowledge throughout the school.

Conclusion

Indigenous young people in this study spoke about their identities and experiences of being Indigenous paradoxically to how Indigenous young people are represented in education policy, literature, and the media. Through undertaking research using a transdisciplinary approach, our team were able to fuse Indigenous knowledge paradigms and Western theories, such as Funds of Identity, to understand the perspectives, stories, and experience of Indigenous young people; this informed how schools can continue to consider identity-affirming and development work in the pursuit of student wellbeing and engagement in schools. We argue that more diverse understandings of mental health and wellbeing are needed to meet the needs of students in contemporary classrooms. Existing research provides evidence of the connections between well-being and identity for Indigenous peoples (Dockery, Citation2012). Although this study provides new data on how Indigenous young people conceptualise and express their identities, well-being, and schooling, we propose further studies that investigate the mental health and well-being impact on Indigenous students at schools that implement identity-based programs and curricula as these are urgently needed as a way of understanding evidence-based approaches to wellbeing in schools.

The data presented from Indigenous young people and local researchers on this project provide a vastly different narrative to that in current policy and the literature. Therefore, this study provides evidence of the need for research guided by Indigenous theories, transdisciplinary in approach and primarily concerned with centring the voices of those whom the research is discussing. The inclusion and authentic understandings of Indigenous peoples, identities, and cultures are essential for all students in Australian schools. As one young person articulated, “if it wasn’t for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people there would be no Australian culture.”

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the young people, local research assistants, schools and communities who participated in this research. We recognise all contributions and contributors to this research and thank the Lowitja Institute for the funding to undertake this research.

Disclosure statement

This research was funded by the Lowitja Institute.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2023.2264027)

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017, June 28). 2071.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the Census, 2016: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0∼2016∼Main%20Features∼Aboriginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20Population%20Data%20Summary∼10

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018, September 31). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2009, January). Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/5b75be10-49ee-4d9c-baf0-5092936c585e/msewatsip.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018, November 29). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescent and youth health and wellbeing 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/atsi-adolescent-youth-health-wellbeing-2018/contents/table-of-contents

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022, May 23). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing. National Indigenous Australians Agency. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-18-social-emotional-wellbeing

- Bassett, B. S., & Geron, T. (2020). Youth voices in education research. Harvard Educational Review, 90(2), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-90.2.165

- Beresford, Q. (2004). Indigenous alienation from school and “the embedded legacy of history": The Australian experience. International Journal on School Disaffection, 2(2), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJSD.02.2.03

- Bessarab, D., & Ng’Andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

- Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Carlson, B. (2016). The legacy of racism and Indigenous Australian identity within education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(4), 784–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.969224

- Bolt, R. (2010). [Urban Aboriginal identity construction in Australia: An Aboriginal perspective utilising multi-method qualitative analysis]. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of Sydney.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brough, M., Bond, C., Hunt, J., Jenkins, D., Shannon, C., & Schubert, L. (2006). Social capital meets identity: Aboriginality in an urban setting. Journal of Sociology, 42(4), 396–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783306069996

- Brown, C., & Shay, M. (2021). Context and implications document for: from resilience to wellbeing: Identity‐building as an alternative framework for schools’ role in promoting children’s mental health. Review of Education, 9(2), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3263

- Carlson, B. (2016). The politics of identity: who counts as Aboriginal today? Aboriginal Studies Press.

- David, S. S. (2016). Funds of knowledge for scholars: Reflections on the translation of theory and its implications. NABE Journal of Research and Practice, 7(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/26390043.2016.12067803

- Dockery, A. M. (2012). Do traditional culture and identity promote the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians? Evidence from the 2008 NATSISS. In B. Hunter & N. Biddle (Eds.), Survey analysis for Indigenous policy in Australia: Social science perspectives (pp. 281–305). Australian National University E Press.

- Dodson, M. (1994). The Wentworth Lecture – The end in the beginning: re(de)finding Aboriginality. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 2–13.

- Elliott, A., & Du Gay, P. (2009). Identity in question. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Esteban-Guitart, M. (2016). Funds of identity: Connecting meaningful learning experiences in and out of school. Cambridge University Press.

- Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014). Lived experience, funds of identity and education. Culture & Psychology, 20(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13515940

- Faircloth, S. C., Hynds, A., & Webber, M. (2020). Exploring methodological and ethical opportunities and challenges when researching with Indigenous youth on issues of identity and culture. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 33(9), 971–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1697467

- Fogarty, W., Lovell, M., Langenberg, J., & Heron, M.-J. (2018). Deficit discourse and strengths-based approaches: Changing the narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. Lowitja Institute. https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Document/Lowitja-Publishing/deficit-discourse-strengths-based.pdfhttps://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2018-05/apo-nid172676_1.pdf

- Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Routledge.

- Graham, M. (2014). Aboriginal notions of relationality and positionalism: A reply to Weber. Global Discourse, 4(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2014.895931

- Hogg, L. (2011). Funds of knowledge: An investigation of coherence within the literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 666–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.005

- Hogg, L., & Volman, M. (2020). A synthesis of funds of Identity research: Purposes, tools, pedagogical approaches, and outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 90(6), 862–895. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320964205

- Kidman, J. (2014). Representing Māori youth voices in community education research. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 49(2), 205–218.

- Lohmeyer, B. A. (2020). ‘Keen as fuck’: Youth participation in qualitative research as ‘parallel projects. ‘ Qualitative Research, 20(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118816627

- MacLean, S., Ritte, R., Thorpe, A., Ewen, S., & Arabena, K. (2017). Health and wellbeing outcomes of programs for Indigenous Australians that include strategies to enable the expression of cultural identities: A systematic review. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 23(4), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY16061

- McCallum, K., & Waller, L. (2022). Un-braiding deficit discourse in Indigenous education news 2008-2018: Performance, attendance and mobility. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1817115

- Moreton-Robinson, A. (2020). Sovereign subjects: Indigenous sovereignty matters. Routledge.

- Paris, D. (2019). Naming beyond the white settler colonial gaze in educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1576943

- Reynolds, H. (1996). Aboriginal sovereignty: Three nations, one Australia. Allen & Unwin.

- Rigney, L. (2006). Indigenist research and Aboriginal Australia. In J. E. Kunnie & N. I. Goduka (Eds.) Indigenous peoples’ wisdom and power (pp. 32–50). Ashgate Publishing.

- Sarra, C. (2011). Strong and smart - towards a pedagogy for emancipation: Education for first peoples. Routledge.

- Stuart, K., & Shay, M. (2018). Countering epistemological exclusion through critical ethical research to support social justice: methodological comparisons between Australia and the United Kingdom. In V. Reyes, J. Charteris, A. Nye & S. Marvopoulo (Eds.), Educational research in the age of the anthropocene (pp. 188–210). IGI Global.

- Shay, M. (2019). Extending the yarning yarn: collaborative yarning methodology for ethical indigenist education research. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.25

- Shay, M., & Sarra, G. (2021). Locating the voices of Indigenous young people on identity in Australia: An Indigenist analysis. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 15(3), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2021.1907330

- Shay, M., Sarra, G., & Woods, A. (2019, August 14). The imagination declaration: young Indigenous Australians want to be heard – but will we listen? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-imagination-declaration-young-indigenous-australians-want-to-be-heard-but-will-we-listen-121569

- Shay, M., Sarra, G., & Woods, A. (in press). Grounded ontologies: Indigenous methodologies in qualitative cross-cultural research. In P. Liamputtong (Ed). Qualitative cross-cultural research: A social science perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sherwood, J., & Geia, L. K. (2014). Historical and current perspectives on the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In O. Best & B. Fredericks (Eds.), Yatdjuligin: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery care (pp.7–30).

- Tripcony, P. (2000). The most disadvantaged? Indigenous education needs. New Horizons in Education, (December 2000), 59–81.

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonising methodologies research and indigenous peoples. (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

- Smith, L. T., Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2019). Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education mapping the long view. Routledge.

- Weaver, H. (2001). Indigenous identity: What is it and who really has it? The American Indian Quarterly, 25(2), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2001.0030

- Wickson, F., Carew, A. L., & Russell, A. W. (2006). Transdisciplinary research: characteristics, quandaries and quality. Futures, 38(9), 1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.011

- Williams, A. D., Clark, T. C., & Lewycka, S. (2018). The associations between cultural identity and mental health outcomes for Indigenous Māori Youth in New Zealand. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(319), 319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00319