?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article analyses the so-called trade-in-tasks models based upon the Heckscher-Ohlin theory recently developed to explain the process of fragmentation. These models continue to rely on comparative advantage to determine trade patterns. The notion of comparative advantage rests on the basic assumption that countries trade only finished goods whose production is domestically integrated. However, since fragmentation implies an increasing trade in intermediate and capital goods and domestic disintegration of production, it does not seem easy to see how comparative advantage continues to work. We identify two crucial assumptions behind these models that allow the principle to work: first, there is a strict distinction between intermediate and finished goods; second, intermediate inputs do not enter the production of themselves. One could relax these assumptions and consider circular production instead. Even so, we identify a third assumption: the neglect of payment of an interest rate over the value of inputs advanced in production. We relax this assumption and consider international capital mobility to show that comparative advantage fails to predict the trade pattern. Therefore, the Heckscher-Ohlin theory is incompetent to explain fragmentation and modern trade patterns.

1. Introduction

Since the end of the last century, financial and commercial integration among countries has been increasing. The advances of information and communication technologies have enabled the fragmentation of production, thereby changing the world production landscape. By fragmentation,Footnote1 we understand the division of previously ‘vertically integrated production processes into separate segments that may enter international trade’ (Jones and Kierzkowski Citation2001, p. 17).

The mainstream of international trade theory has not ignored the implications of this phenomenon. Indeed, there has been a substantial development of so-called trade-in-tasks models. However, these models do not challenge the standard theory’s results. For Bhagwati, Panagariya, and Srinivasan, fragmentation

is fundamentally just a trade phenomenon; that is, subject to the usual theoretical caveats and practical responses, outsourcing leads to gains from trade, and its effects on jobs and wages are not qualitatively different from those of conventional trade in goods. (Bhagwati, Panagariya, and Srinivasan Citation2004, p. 94)

Admittedly, the principle of comparative advantage continues to prevail in the new models.Footnote2 Based upon it, mainstream economists hold that fragmentation allows a deeper degree of specialisation, thereby increasing trade gains. As Jones and Kierzkowski (Citation2001, p. 18) claim, ‘if the term fragmentation suggests destruction, it is creative destruction in the Schumpeterian tradition. Breaking down the integrated process into separate stages of production opens up new possibilities for exploiting gains from specialisation.’

The principle also continues to help determine trade patterns. For example, according to Baldwin (Citation2013), fragmentation has two first-order effects. Firstly, the range of intermediate goods produced domestically shrink. Secondly, international trade in intermediates rises.

The first effect stems from the fact that at the high end of the range, imports displace domestic production of intermediates. While bad news for any specific factors involved in the newly uncompetitive intermediates, this is good news for downstream competitiveness. Since the imports are cheaper, downstream competitiveness is improved. More local downstream production is good news for intermediate producers in the middle segment. The second effect stems from the way that lower coordination costs allow [countries] to export the parts where it has the greatest comparative advantage. (Baldwin Citation2013, p. 196)

As another example, take former World Bank economist Justin Yifu Lin, who claims that ‘countries at different stages of development could even concentrate on different segments at the same industry, each using different technologies and producing different products according to comparative advantages’ (Lin and Chang, Citation2009, p. 135).

In most trade-in-tasks models, fragmentation raises the overall income of each country over a pre-fragmentation scenario. The models focus on long-run analysis and, therefore, assume full employment. Thus, fragmentation does not affect the employment level but changes income distribution. Paraphrasing mainstream economists, Paul Samuelson offers a fair summary of their position:

Yes, good jobs may be lost here in the short run. But still total U.S. net national product must, by the economic laws of comparative advantage, be raised in the long run (and China, too). The gains of the winners from free trade, properly measured, work out to exceed the losses of the losers … (Samuelson Citation2004, p. 135)

This paper answers this question by analysing the modelling strategy of fragmentation within the Heckscher-Ohlin or factor proportions theory. The reason to focus on this theory is its widespread use in the literature. Adrian Wood (Citation1994a, Citation1994b, Citation1995) and Leamer (Citation1995) revived the Heckscher-Ohlin model in the early 1990s to explain the rise in the wage skill premium in developed countries since the late 1970s. This model’s well-known result is that a country’s abundant factor gains from trade, while the scarce factor loses. Trade integration with developing economies increases the skilled-unskilled wage ratio in developed countries, thereby raising income inequality. If unskilled workers refuse the wage cuts, then unemployment follows. Consequently, trade with developing economies hurts unskilled workers from developed countries.Footnote3 Since then, the proliferation of Heckscher-Ohlin-type models to either defend or refute this hypothesis has been increasing.

In the Heckscher-Ohlin theory, the factor-intensity ranking is a crucial tool to define the trade pattern. However, there is ambiguity regarding whether direct or total factor intensities when production requires intermediate inputs and capital goods. Total factor intensity is the best choice if trade in intermediates is not allowed, though fragmentation challenges this assumption. The trade-in-tasks models that we analyse recur to a comparative-advantage chain based on direct factor intensity. We find two assumptions for this chain to work: first, there is a strict distinction between intermediate and finished goods; second, intermediate inputs do not enter in the production of themselves.

According to Deardorff (Citation1979), one could relax these assumptions, consider circular production, and continue to use direct factor intensities to determine the trade pattern. The analysis would not convey information on relative prices but relative value-added. In this case, we identify a third assumption: the neglect of payment of an interest rate over the value of inputs advanced in production. We show how the direct factor intensity ranking fails to predict the trade pattern when we relax this assumption in a scenario of full capital mobility.

After this introduction, Section 2 presents a standard Heckscher-Ohlin model with two primary factors. A key concept for our analysis is the chain of comparative advantage. We discuss its specification in this standard model. Section 3 analyses the modelling strategy of fragmentation by reviewing two trade-in-task models. Following this scrutiny, Section 4 discusses the underlying assumptions that allow these models to continue working with a comparative advantage chain. As fragmentation implies increasing trade in capital goods and financial capital mobility, Section 5 discusses the introduction of ‘capital’ as a factor of production. As anticipated, we show that the payment of an interest rate on the capital goods employed causes the chain to stop working. Section 6 offers our concluding remarks.

2. Comparative Advantage in the Heckscher-Ohlin Model

The theory of comparative advantage states that each country specialises in the set of products that it can produce relatively cheaper before international trade (Dixit and Norman Citation1980). Thus, the basis for the comparison is autarky competitive prices. The latter must cover the production cost, pay a uniform rental to each productive factor, and not make extra profits. Implicitly, there is also the assumption of domestic integration of production.

Suppose that the global economy consists of two regions — North and South — and two products — Machinery and Apparel. Consider the following list of prices:

If the South produces one Machinery unit less, it releases resources that could deliver (1000/250=) 4 more Apparel units. Similarly, the North can get one Machinery unit by reallocating the resources engaged in producing (400/200=) 2 units of Apparel. Thus, the global output of Apparel increases without affecting that of Machinery. If Apparel is the numeraire, Machinery’s relative price is two in the North and four in the South. Thus, with free trade, the North has an incentive to produce more output than it consumes of Machinery and export the excess in return for imports of Apparel from the South. The latter has the same incentive to specialise in Apparel.

Due to specialisation, the global output of both products increases. Hence, countries are better off from international trade. However, the level of factor employment stays unchanged in this analysis. Factor prices adjust to keep full employment in neoclassical theory and, therefore, international trade only changes domestic income distribution.

Our light-touch presentation of the theory of comparative advantage only assumed differences in the autarkic relative prices of countries. In neoclassical theory, prices depend on technology, factor endowments, and consumer preferences. Hence, any difference in these data among countries will lead to a difference in relative prices. Heckscher-Ohlin models focus exclusively on differences in factor endowments as the source of comparative advantage.Footnote4,Footnote5 Within these models, the ranking of commodities in terms of factor intensities is a helpful tool to predict the trade pattern. We can discuss this point by first considering the standard-textbook Heckscher-Ohlin model.

2.1. The Heckscher-Ohlin Model

Let us discuss a standard Heckscher-Ohlin model with the following assumptions:

The global economy consists of two regions — North and South, and two manufacturing goods — Apparel and Machinery.

There are two internationally immobile non-produced, primary production factors — unskilled labour (or shortly, labour) and skilled labour (or briefly, skill). The two are susceptible to combination in variable proportions in production.

The production of goods requires only skilled and unskilled labour with no time lag and is subject to constant returns to scale.

Each region has a different relative endowment of skilled and unskilled labour.

Technology is the same as between regions.

Consumers in both regions have the same set of homothetic preferences.

There is perfect competition, zero transport costs, and free trade.

We have chosen unskilled and skilled labour as the non-produced, primary factors following the current literature on fragmentation (e.g., Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg Citation2008). The third assumption implies dealing with a production system without intermediates or capital goods (cf. Petri Citation2004, pp. 72–88).Footnote6 Section 3 will relax this assumption and analyse how the recent literature has dealt with this type of goods.

The inability of the non-produced, primary factors to move internationally is the differentia of the theory of international values relative to the general theory of value. The latter usually deals with national or single markets. If all primary factors were mobile, there would be no need for a theory of comparative advantage because international competition would work the same way as competition within a nation (cf. Shaikh Citation2007, p. 57). According to our assumptions, since the only difference among regions are relative endowments, countries’ relative prices before international trade differ exclusively for this motive (cf. Ohlin Citation1967).

Let us initially consider the zero-profit condition under autarky. This condition states that the price of every commodity must equal its long-run minimum unit cost.Footnote7 Let stand for the price of good

(Machinery), 2 (Apparel);

the rental of factor

(skilled labour),

(unskilled labour); and

the optimal amount of factor

required per unit of output of good

. We may also refer to the latter as the direct factor-input coefficient. Therefore, we can express the condition as:

(1)

(1) From system (1), we can write the relative price of Machinery as:

(2)

(2) The variable

stands for the skilled-unskilled wage ratio.

The quotient shows the ratio of skilled to unskilled labour employed in the production of good

. It is also known as factor intensity — in our case, skill intensity. The quotient obtains from the optimal factor input coefficients, so only factor rentals may affect factor intensity. The output level does not affect it due to the assumption of constant returns to scale.

From equation 2, we can see that the relation between the relative price of Machinery and the skilled-unskilled wage ratio is positive if Machinery is more skill-intensive than Apparel.Footnote8 For this relationship to be monotonic, we must introduce the supplementary assumption of no factor intensity reversal. Under this supposition, the factor intensity of Machinery is always higher for all skilled-unskilled wage ratio values.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem states that each country specialises in the product that uses intensively the relatively abundant factor. There are two ways to define factor abundance. The first is comparing relative factor endowments, while the second looks at autarky relative factor rentals. According to the latter, the skill-abundant region has a lower skilled-unskilled wage ratio than the labour-abundant region. Therefore, it has a lower relative cost of the skill-intensive good. If we consider the North as skill-abundant, it follows that it will export Machinery. By contrast, the South is labour-abundant and will export Apparel.

2.2. Free Trade

It is convenient to analyse the process of specialisation with the help of the Lerner-Pearce diagram (Leamer Citation1995). This analysis will also reveal how — under the given assumptions — the flexibility of prices and factor substitution mechanisms underlie the mainstream assertion that free trade leaves the factor employment levels unchanged.Footnote9

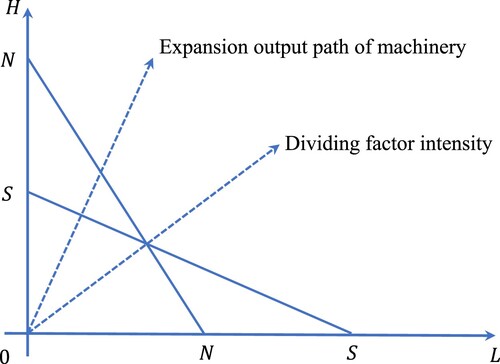

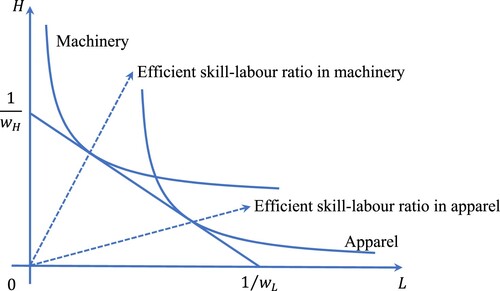

plots two unit-value isoquants labelled Machinery and Apparel. These show the alternative combinations of skill and labour employed to generate a money unit worth of output. On the other hand, the unit-isocost line shows the alternative combinations of both factors that cost one money unit.

Figure 1. The Lerner-Pearce diagram.

Source: Own elaboration based on Leamer (Citation1995).

There is a unique set of prices that make the unit-value isoquants tangent to the unit-isocost line. If an isoquant lies above the isocost line, there would be negative profits, and vice versa. The ray that goes from the origin and passes through the tangency point reveals the efficient factor intensity of commodities. Finally, the intersection of the unit-isocost line in each axis reveals the factor rentals.

displays two autarky unit-isocost lines. Following the price definition of factor abundance, North’s isocost line, , is steeper than South’s,

. The ray that goes from the origin and passes through the intersection of both isocost lines is the ‘dividing’ factor intensity. For goods with a factor intensity higher than the dividing one, the North can produce the same output as the South but at a lower cost.Footnote10 Naturally, with factors combined in variable proportions, both countries could deliver one commodity at an equal price but with a different factor intensity. However, this cannot happen for more than one good in the absence of factor intensity reversal.

Let us suppose that the North has a competitive advantage in Machinery and the South in Apparel before trading. With free trade, output expands in the skill-intensive industry and contracts in the labour-intensive industry in the North, leading to excess demand for skilled labour and the unemployment of unskilled labour. By admitting indefinite wage flexibility (cf. Garegnani Citation1990), skilled workers wage increases while unskilled workers wage drops. The increase in the skilled-unskilled wage ratio leads firms to employ a lower proportion of skilled-to-unskilled labour in both industries. In the South, there is excess demand for unskilled labour and unemployment of skilled labour. As the scarce factor becomes dear, all activities tend to employ a higher ratio of skilled-unskilled workers. Together with factor substitution, wage flexibility assures both countries’ full employment in the free trade equilibrium.

One of the core propositions of the Heckscher-Ohlin theory is that product-price equalisation tends to reduce factor-price differences. Under specific circumstances (e.g., similar factor-endowments ratio), this convergence implies absolute factor-price equality. In this situation, unit-isocost lines are equal in free trade; both regions produce the two commodities, and specialisation is incomplete. However, the North will generate more output than it consumes of Machinery and export the surplus in return for Apparel, vice versa the South. If the variation of the factor-endowments ratio among countries is large enough, there will be complete specialisation and only relative factor-price convergence.

2.3. Many Commodities: The Chain of Comparative Advantage

With more than two commodities, we can rank them from higher to lower skill intensity. The ranking defines a chain of comparative advantage. The chain tells the order of goods that a country can produce more cheaply. The skill-abundant country reads the chain from left to right, while the labour-abundant in the opposite sense. The former will necessarily export the highest skill-intensive commodity, and the latter will necessarily specialise in the least skill-intensive good.

From technology alone, we cannot deduce which other commodities North and South will produce. The chain breaks also depend on endowments and consumer preferences. Nevertheless, wherever it cuts, the factor intensity of North’s exports will always be higher than imports, and vice versa in the South.

If factor-price equalisation obtains, the trade pattern is undetermined. However, one could assert that North exports on average skill-intensive commodities, while the South labour-intensive (Dornbusch, Fischer, and Samuelson Citation1980).

3. Fragmentation

The standard Heckscher-Ohlin model assumes that the production of final goods requires skilled and unskilled labour alone. However, this is not very realistic. Final goods also need intermediate inputs and capital goods for their production. One way to deal with reproducible means of production is to assume vertically integrated production processes and only trade of final goods. However, fragmentation precisely implies the vertical disintegration of production within domestic borders to develop global supply chains. Intermediate and capital goods become tradable along with final goods.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was an emergence of trade models focusing on the general-equilibrium effects of fragmentation on domestic income distribution and output composition (Arndt Citation1998; Venables Citation1999; Deardorff Citation2001; Jones and Kierzkowski Citation2001; Kohler Citation2004).Footnote11 The literature later baptised them as trade-in-tasks models (Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud Citation2014). Their novelty lay in a modelling strategy that broke down finished goods factor-input coefficients into different task-specific factor-input coefficients.

For better understanding, it helps to lay it down in formal terms. Let us suppose that the production of final good requires

tasks.Footnote12 We normalise the quantity of a task needed to obtain one unit of the finished good to one.Footnote13 Let

be the amount of factor

needed to deliver task

(

). Due to normalisation, the quantity of factor

needed to get one unit of good

is simply the sum of all

:

(3)

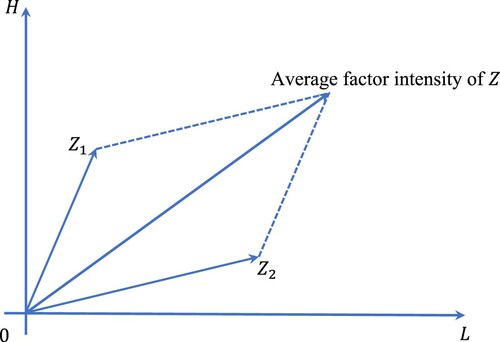

(3) illustrates the case for a good that needs two tasks for completion. In the figure, the vectors

and

represent the quantity of skill and labour needed for the first and second task, respectively. Task one is more skill-intensive than task two. The vector sum of

and

makes the factor intensity of the finished good

.

Note that since the absence of fragmentation is equivalent to the assumption of domestic vertical integration, we could have interpreted each of the standard model of Section 2 as an average or, more precisely, a linear combination of the quantity of each factor employed in the tasks needed to deliver the final goods.Footnote14

We will examine two trade-in-tasks Heckscher-Ohlin models. Our examination will show that these models continue to employ the comparative advantage chain to determine trade patterns. Therefore, these models do not challenge but reinforce the standard Heckscher-Ohlin model’s core tenets.

Before we continue to the analysis of these models, a final appreciation follows. In both models, each country has a given endowment of labour and ‘capital.’ The latter is an input for producing finished goods and tasks, but no industry produces it. That is, both models treat ‘capital’ as a primary factor. For this reason, it is convenient to replace ‘capital’ with skilled labour following our standard Heckscher-Ohlin model (cf. Section 2). We leave the discussion of the implications of a more realistic specification of ‘capital’ as a productive factor for Section 5.

3.1. Arndt’s Analysis

Arndt (Citation1997, Citation1998) studies the effects of fragmentation for a small open economy. The author considers two final goods, X and Y, produced in variable skilled and unskilled labour proportions. The average skill intensity of product Y is higher than product X. The country is skill-abundant; it exports Y and imports X.

Arndt separates the analysis of fragmentation according to which industry it occurs in. Let us consider first the exporting sector. Suppose that Y’s production requires two discrete stages, the first involving the completion of an intermediate input and the second being the final good’s manufacturing. Arndt assumes the second stage to be more skill-intensive than the early stage. The skill intensity of this latter stage can be higher or lower than that of product X.

If fragmentation is possible, it may be convenient for the country to outsource the first stage and dedicate more resources to the second stage. Now it could export Y in return for imports of X and the intermediate product. Arndt makes the supplementary assumption that the intermediate product’s foreign sourcing is so cheap that home production ceases entirely.

The change in sourcing practices reduces Y’s production costs. Since international prices do not change, short-run extra profits appear. The production of Y increases and absorbs part of the factors previously employed in the first production stage. However, since the second stage is more skilled labour-intensive, there will be an excess demand for skilled labour and unemployment of unskilled labour. The competition in factor markets raises the wage of skilled workers and lowers that of unskilled workers. The increase in the factor price ratio will induce all producers to employ more unskilled labour-intensive techniques.

Let us now consider the importing industry. As before, suppose that X’s production takes over in two stages and that the second stage is more skill-intensive than the first. The outsourcing of the intermediate input reduces X’s production costs and induces an expansion of its output. Since X is, on average, the unskilled labour-intensive industry, this expansion can happen only at the expense of Y’s production. Thus, there is an excess demand for unskilled labour and unemployment of skilled labour. The competition in factor markets lowers the wage of skilled workers and raises that of unskilled workers. The decrease in the factor price ratio will induce all producers to employ more skilled labour-intensive techniques.

As we can see, the chain of comparative advantage changes from comparing average factor intensities to comparing task’s factor intensities. Nonetheless, after fragmentation, the small economy’s exports are still more skill-intensive than the imports. Thus, the chain preserves its explanatory power. As in the standard model, wage flexibility and factor substitution ensure full employment in the long run. Arndt’s weakness is that the aggregate effect on income distribution is a priori indeterminate as it depends on the extent of fragmentation on the exporting and importing industries.

3.2. Jones and Kierzkowski’s Analysis

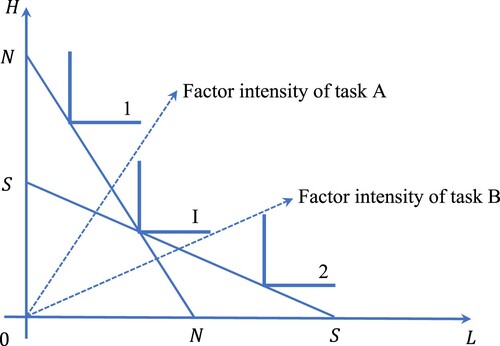

Jones and Kierzkowski (Citation2001) consider three final goods, namely 1, 2, and I. The production of I requires two tasks, A and B. The authors assume only one production process for each product. Let us continue to assume that the global economy consists of two countries, North and South.

displays a hypothetical pre-fragmentation free-trade equilibrium. From the unit-isocost lines, we can see that the North, skill-abundant, is the sole producer of good one, and the South, labour-abundant, is the only producer of good two; both countries can produce good I at the exact cost.

Figure 4. Free trade equilibrium without fragmentation.

Source: Own elaboration based on Jones and Kierzkowski (Citation2001).

Now imagine that fragmentation of I is possible. Since task A is more skill-intensive than task B, and the average factor intensity of I is equal to the dividing one, then we may deduce that, at current factor prices, the North and the South can supply at a lower cost task A and B, respectively. If task A stands for components production and task B for the assembly of I, then the North exports good one and task A in return for imports of goods two and I.

The adjustment toward the new equilibrium requires a change in factor prices. In the North, the resources released from task B shift to industries one and A. However, since task B is less skill-intensive than task A, there is an excess demand for skilled labour and unemployment of unskilled labour. Therefore, the wages of skilled workers rise, and the wages of unskilled workers fall. The opposite happens in the South. The resources released from industry A shift to industries two and B. Given that task A is more skill-intensive, there is an excess demand for unskilled workers and unemployment of skilled labour, raising the wages of the first and lowering those of the latter.

In this model, the effect on income distribution within countries is unambiguous as in the standard Heckscher-Ohlin model. Fragmentation leads to a relative factor price convergence.Footnote15 As in Arndt, the average factor intensity of I disappears from the comparative advantage chain and instead considers those of each task. Wage flexibility and indirect factor substitution (changes in the composition of final demand) ensure full employment.

4. Uncovering the Underlying Assumptions of Trade-in-Tasks Models

As we have seen, the factor-intensity ranking defines countries’ comparative advantage and helps to predict the trade pattern. In the two-factor model without intermediate goods (cf. Section 2), the comparison of direct factor intensities is sufficient. When there are intermediate goods, we can assume that they are non-tradable and compare the average factor intensities of final commodities (Batra and Casas Citation1973). However, the fragmentation setting poses a challenge to this procedure since increasing trade in intermediates is one of its crucial features. Thus, it is not acceptable to rank final goods based on average factor intensities as this ranking no longer strictly reflects domestic production conditions.

In the models we have presented, fragmentation develops a new and different ranking based on the factor intensities of tasks. It is as if it creates new commodities and destroys others. Final goods may enter the chain but as a task after which one obtains the finished product. We will show that this ranking works under a specific structure of production.

Let us consider a model with many commodities that have both intermediate and final uses. Let be the matrix of input-output coefficients, with

being the quantity of good

used as input for producing one unit of good

. Since producing commodities now requires themselves as inputs, we need to distinguish between direct and total factor intensity. The latter considers the quantity of skilled and unskilled labour directly and indirectly employed in producing commodities.

For computing the total quantity of a factor needed in the production of commodities, let stand for Leontief’s inverse matrix, with

being the direct and indirect quantity of good

used as input for producing one unit of good

. The vertically integrated amount of each factor employed for producing one unit of

obtains by multiplying the factor input coefficient vector and the

-th column of Leontief’s inverse matrix:

This sum is like equation 3, but now the bs act as weights instead of having ones. In equation 3, there is a strict distinction between intermediate inputs (tasks) and finished goods. One group of commodities consists of pure intermediates, while the other group of pure final goods. The latter do not employ factors directly. For all positive bs to be equal to one, the pure intermediates must not enter the production of themselves.

These assumptions allow us to consider a task as a final good whose production cost does not depend on the cost of other tasks conducted abroad. In other words, as if there were domestic integration of production.Footnote16 We may illustrate this point with the help of a simple example. Consider a case with three products: two consumption goods and one intermediate input. The finished products employ the intermediate commodity in fixed proportions. We can summarise the production relationships through the following use table:

Table

The absence of fragmentation means that the intermediate is non-tradable. To define the trade pattern, we use the total factor intensity ranking and consider only finished products. As the example shows, good 2 employs a higher total skill-unskilled labour ratio than good 1.

With fragmentation, the intermediate input becomes tradable. In this case, what we previously defined as ‘final good’ in the earlier use table now becomes the final manufacturing stage. The new use table would be:

Table

Total factor intensities are no longer relevant in finding the trade pattern. Instead, we must build the ranking with the direct ones. We have that input 3 employs a higher direct skilled-unskilled labour ratio than task 2, which employs a higher direct skilled-unskilled labour ratio than task 1. Naturally, a different trade pattern from the previous could emerge. For example, the skill-abundant country might entirely specialise in the intermediate input production, and the labour-abundant country could take over one and two. However, the patterns will not violate the new comparative advantage chain.

4.1. Unit Value-Added Isoquants

The analysis becomes more complicated than previously if we lose the above assumptions and consider circular production. Which factor intensity should one use to construct the chain of comparative advantage?Footnote17 Total factor intensity might not be adequate since it assumes the domestic integration of production. Deardorff (Citation1979) suggests a device to employ direct factor intensities for predicting the trade pattern. It consists of replacing the notion of unit-value isoquant with that of unit-value-added isoquant.

Taking prices as given, firms maximise the net revenue distributed to payment of primary factors, skill, and labour. We can write the value-added function of any commodity as:

Where

is the output of

;

is the quantity of

used as inputs for producing

; and

is the production function.

The unit-value-added isoquants are obtained by setting , and production requires tangency between these and the unit-isocost line. With free trade, all prices are the same for the countries. Therefore, they should share identical unit-value-added isoquants. Thus, the ranking of direct factor intensities continues to work even with circular production.

5. ‘Capital’ in the Heckscher-Ohlin Model

So far, we have considered two primary factors and avoided introducing ‘capital’ as a productive factor. The main difficulty of introducing ‘capital’ is that it consists of reproducible means of production; that is, a set of heterogeneous inputs needed to obtain final goods.

One alternative is to circumvent the problem by defining ‘capital’ as a single, physically homogeneous, and indestructible good. As Gandolfo (Citation2014) aptly claims, this definition of the capital endowment serves only to give an illusory sense of realism since it is indistinguishable from other primary factors such as land.

Once we admit that ‘capital’ consists of physically heterogeneous goods, another route considers the capital endowment as a single magnitude of variable form or composition (cf. Petri Citation2004). Here appears the problem of selecting the standard of value for measuring the capital endowment. This choice is arbitrary, and it is not a mere technical point. It may affect the ranking of countries in terms of relative endowments and goods in terms of factor intensity.

Furthermore, once we introduce ‘capital,’ the interest rate emerges as a variable to be determined. According to neoclassical theory, the interest rate results from the equality between supply and demand for ‘capital’ services. Economic equilibrium also requires the following conditions (Petri Citation2004, chap. 3):

As it consists of produced means of production, the price of new capital goods must be equal to their long-run production cost (supply price).

Since it is an investment, the rental of capital goods must pay a uniform rate of return.

The demand price of each capital good (i.e., the rental) must also equal the supply price; otherwise, there will be no incentive to produce it.

From these conditions, we can deduce that relative prices depend on the interest rate. It is well-known how this dependence affects the measurement problem mentioned above. Whatever the standard of value, a change in the interest rate modifies relative prices and, consequently, alters the capital endowment value (even if its composition remains the same) (cf. Gandolfo Citation2014, pp. 121–123).

Moreover, this dependence may also affect the monotonic relationship between the relative price of goods and factors. As we said, one explanation of the absence of such a relationship is the possibility of factor-intensity reversals. However, with ‘capital’ as a productive factor, the violation of monotonicity may occur, even ruling out this phenomenon (cf. Metcalfe and Steedman Citation1979a). Consequently, even if price effects do not alter the ranking of factor intensities, it is still possible a scenario where the ‘capital’-abundant country with a lower interest rate exports the labour-intensive commodity and vice versa. Therefore, the ordering of goods in terms of factor intensities conveys no information about comparative advantage.

In what sense we can speak of a capital endowment if capital goods are reproducible and internationally traded? Also, how does this endowment influence trade patterns? (cf. Subasat Citation2003). Mainstream economists have long acknowledged these supply-side problems of ‘capital.’ For example, Wood (Citation1994b, p. 32) claims that ‘capital cannot be a basic source of comparative advantage.’ He grounds this assertion on the increasing evidence of substantial international trade in capital goods. Thus, the relative scarcity (or quantity) of this factor does not determine the interest rate. Although Wood does not offer an alternative explanation of the interest rate, he assumes it to be equal across countries due to international (finance) capital mobility.

These assumptions allow the author to explain the trade patterns based on differences in relative endowments of skilled to unskilled labour, such as the standard Heckscher-Ohlin model presented in Section 2. However, contrary to the standard model, the author misses that the payment of an interest rate and full capital mobility may affect the trade pattern in ways that contradict the factor intensity ranking.Footnote18

It may be convenient to see this by considering the following counterexample. Let us introduce a third commodity, say Iron, to our standard model from Section 2. The production of Machinery requires Iron as an intermediate input. Since Iron is a tradable intermediate input, we must compare the direct factor intensities. Hence, suppose that Machinery employs a higher direct skill/labour ratio than Apparel, which employs a higher direct skill-labour ratio than Iron. Therefore, we should expect that the North specialises in Machinery and the South in Iron, specialising in Apparel being a priori undetermined. Now consider the following assumptions:

The North has a lower, near-zero autarky interest rate.

The South is so large that we can take its prices as independent from trade.

With free trade, the North could reduce the cost of Machinery by sourcing Iron from the South. However, given full capital mobility, the interest rate rises in the North due to arbitrage, raising its costs. The result of these opposing effects is uncertain a priori. If capital costs eventually increase, the impact could be strong enough to make the North uncompetitive in Machinery. Instead, it shifts to Apparel as it does not require Iron as an input. Thus, the North could export Apparel and import Machinery, thereby violating the chain of comparative advantage.

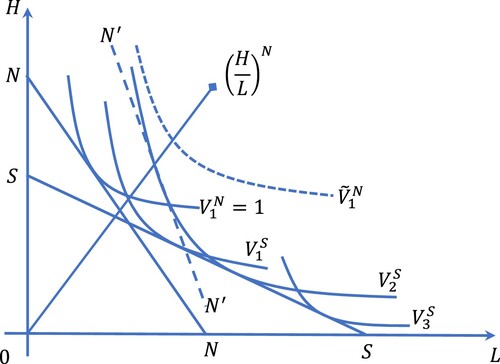

We can reflect the intuition of this result with the aid of . The autarky unit-value-added isoquants of Machinery are not the same. The reason is due to differences in the iron-input coefficient and interest rates. Nonetheless, suppose that the autarky price of Machinery is equal in both countries. The rest of the isoquants are identical since Apparel and Iron do not need intermediate inputs. Thus, the South has a cost advantage in Apparel and Iron.

Figure 5. Trade pattern reversal with trade in intermediate inputs and free capital mobility.

Source: Own elaboration based on Deardorff (Citation1979).

The effect of free trade with full capital mobility is to push North’s unit-value-added isoquant of Machinery far away from the origin (northeast). With free trade, all prices are the same, but the unit value-added isoquants of Machinery continue to differ. The reason is that for different factor prices, the optimal technique changes. Therefore, the iron input coefficient varies among countries leading to distinct capital costs. The unit value-added isoquant is above

because at North’s free-trade equilibrium factor prices, its optimum iron-input coefficient is higher. As the North shifts to Apparel, factor prices adjust to ensure zero profits and employ factors according to its relative endowment ratio. It follows that North exports Apparel and imports Machinery. Full capital mobility completely reversed the trade pattern.Footnote19

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper has analysed the workings of the principle of comparative advantage in the new trade-in-task models. As we have seen, the main innovation in Ardnt and Jones-Kierzkowski is to change the comparative advantage chain by considering factor intensities at each production stage or task. The two conditions needed for this ranking to work are: a strict distinction between intermediate and finished goods, and intermediate inputs must not enter the production of themselves. Even if these two conditions do not hold, Deardorff claims that direct factor intensities remain relevant. The analysis would not convey information on relative prices but relative value-added.

However, two crucial features of fragmentation are the increasing trade in intermediates and capital goods and the growing mobility of financial capital. We have seen that Wood acknowledges these features and considers that the Heckscher-Ohlin model continues to be fit. The models we reviewed lack an adequate specification of ‘capital’ as a productive factor. Moreover, the models neglect the payment of an interest rate over the value of the means of production. From our analysis of Section 5, we can see that this is also a condition for the chain to work. As we have seen, when all commodities are tradable, and full capital mobility prevails, the chain breaks down: it is no longer helpful in figuring out the trade pattern.

This result exhibits the inadequacy of the factor proportions theory to explain the recent changes in trade patterns due to fragmentation. That is, factor endowments play — if they do — a small role in defining specialisation along a global supply chain. Therefore, it would be preferable to discuss these phenomena through models that downplay the role of differences in factor endowments. Such is the case of ‘Ricardian’ models that emphasise differences in technology among countries. As one authoritative figure of mainstream international trade theory says,

The Heckscher-Ohlin model is hopelessly inadequate as an explanation for historical or modern trade patterns unless we allow for technological differences across countries. For this reason, the Ricardian model is as relevant today as it has always been. (Feenstra Citation2004, p. 1)

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Special thanks go to Ariel Dvoskin for continued advice and encouragement during the process of writing this article. The author is solely responsible for the contents of this work.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Other similar definitions are outsourcing, offshoring, production sharing, ‘intra-mediate’ trade, vertical specialisation, global value chains, etc. These terms refer to the greater geographical dispersion of global production and the increasing functional integration among countries through trade. See Feenstra (Citation1998) and Hummels, Ishii, and Yi (Citation2001) for an analysis of the evidence.

2 According to Milberg and Winkler (Citation2013, chap. 3), the principle regained strength vis-à-vis the increasing use of the Heckscher-Ohlin model for the analysis of fragmentation.

3 There was considerable debating during the 1990s about this hypothesis. Understandably, it is politically unsatisfactory for free-trade ideologists since it supports protectionist policies. According to the critics, a weak point of the trade hypothesis is the lack of evidence. One of the implications of the standard Heckscher-Ohlin model is a decline in the ratio of skilled to unskilled labour in most industries in the North. However, the empirical evidence at the time suggests that this ratio had increased. The alternative hypothesis of the increasing wage gap in the North was skill-biased technical change. Eventually, this explanation gained a growing consensus concluding the debate. See Wood (Citation2018) for a review.

4 Models that focus on differences in technology are called ‘Ricardian’ in the literature. This paper does not deal with these models. See Crespo, Dvoskin, and Ianni (Citation2021) for a critical assessment.

5 As we have seen, the principle of comparative advantage has two core propositions (cf. Findlay Citation2008). The first is about the direction of trade: each country exports the set of goods with lower opportunity costs ratios. The second is about the existence of trade: any country can sell a range of goods in free trade, no matter how technologically backward it is (Krugman Citation1996, p. 89). Heckscher-Ohlin models do not present a difficulty sustaining this last proposition since they usually assume that technology is the same for all countries. Therefore, this article will focus exclusively on discussing the proposition of direction, that is, on the model’s aptitude for predicting the trade pattern.

6 Other standard models conceive capital as a primary factor given in quantity, not produced in any sector and indestructible, together with labor. This assumption makes capital indistinguishable from land (cf. Section 5).

7 Taking prices and rentals as given, producers select the efficient ratio of skilled to unskilled labour. This ratio is independent of the level of output because of the supposition of constant returns to scale. Thus, given factor prices, it is possible to determine univocally the long-run minimum unit cost for every commodity (cf. Petri Citation2021).

8 This proposition is similar but not equivalent to the Stolper-Samuelson theorem. The latter states that an increase in the relative price of one commodity favours the factor used intensively in its production. Therefore, it suggests a causal direction from prices to factor rentals.

9 Also, it will show that the only sustainable factor employment levels are the full-employment ones.

10 The proof is straightforward. As we said, the tangency condition defines the efficient factor intensity in producing a commodity. With constant returns to scale, the ray that goes from the origin and passes through the tangency point is also the expansion output path. Hence, the intersection of a unit-isocost line with this path below the tangency point implies a lower output level (and a higher price).

11 Another stream of literature has focused on the analysis of fragmentation from the transaction-costs perspective. These studies discuss how recent technological changes redefine the boundaries of the multinational firm and lead to fragmentation. See, e.g., Antràs and Chor (Citation2013).

12 One can speak interchangeably of stages, components, among others; formally, there are no differences.

13 This assumption is like that of Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg (Citation2008), although they assume that only one factor performs each task.

14 The fragmentation literature identifies two alternative configurations of a supply chain (Baldwin and Venables Citation2013). In the spider, producers assemble separate parts and get the final good. In the snake, production is sequential; each task transforms the product. Assuming a nil interest rate and ruling out transaction costs makes inconsequential this distinction.

15 Given the importance of the fragmentation effect on the scarce factor rental, Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg (Citation2008) show how this factor may not lose. The authors identify three channels through which fragmentation affects the rental of the scarce factor. The first is a productivity effect. Recall that the factor input coefficient of a final good equals the sum of the factor input coefficients of the requiring tasks. If fragmentation reduces the number of stages performed domestically, it also reduces the factor input coefficient of final goods. This reduction is equivalent to an overall boost in the factor productivity and tends to increase its rental. The second is a relative-price effect. If fragmentation reduces the commodity price that uses the scarce factor intensively, then, as per the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, there is downward pressure on the factor rental. Finally, the third is a supply effect. As we have seen, fragmentation frees up units of the scarce factor that the market must reabsorb, and that may contribute to a fall in their rental. The first effect may dominate over the others and raise the scarce factor rental.

16 In Sraffa’s (Citation1960) terminology, these assumptions are equivalent to ruling out basic commodities. A solution could be assuming that final goods enter the consumption basket of workers.

17 Vanek (Citation1963) was among the firsts to extend the factor proportion theory to consider interindustry flows. In his two-commodity model, it is irrelevant the factor intensity used. Batra and Casas (Citation1973), conversely, introduced a third, pure intermediate commodity and showed that the total and direct factor intensity rankings might differ. The authors maintain that the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem would hold if the intermediate product were non-tradable. Later, Riedel (Citation1976) extended Batra and Casas’ analysis. On the one hand, he criticises the general procedure of empirical tests of the factor proportion hypothesis that consider total factor intensities and assume domestic vertical integration. On the other, the author suggests alternative factor intensity measures that include imported intermediates. Logically, these measures are only relevant for practical purposes. On this issue, cf. Hamilton and Svensson (Citation1983).

18 Although aware of the Sraffian criticism of neoclassical trade theory, Wood also omits Metcalfe and Steedman theoretical results (Metcalfe and Steedman Citation1979b; Steedman and Metcalfe Citation1979). Briefly put, they show that when the interest rate is positive, on the one hand, a higher skilled-unskilled wage ratio is no longer associated with skill-intensive methods. On the other hand, a higher relative supply of skilled labour is no longer associated with a lower skilled-unskilled wage ratio and a lower relative price of the skill-intensive commodity. Therefore, machinery could be relatively cheaper in the South than in the North. So, the skilled-unskilled wage ratio would be higher in the latter, contradicting the price definition of factor abundance. In this case, the relative-price convergence will benefit one of the scarce factors. International trade will either raise the real wage of unskilled labour in the North or the real wage of skilled labour in the South. Overall, trade may not hurt (northern) unskilled workers.

19 Our example is based on Deardorff (Citation1979) but it is worth pointing out some crucial differences. First, Deardorff neglects the payment of an interest rate on the value of advanced inputs for production. The reversal in Deardorff occurs–in our terms–by North’s imposition of a tariff in Iron, that is, a trade distortion. Conversely, we maintain the assumption of absence trade barriers of any kind (made in Section 2.1). The introduction of an interest rate with free capital mobility invalidates the comparative advantage chain, even in a frictionless, distortion-free imaginary world.

References

- Antràs, P., and D. Chor. 2013. ‘Organizing the Global Value Chain.’ Econometrica 81 (6): 2127–2204.

- Arndt, S. W. 1997. ‘Globalization and the Open Economy.’ The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 8 (1): 71–79.

- Arndt, S. W. 1998. ‘Globalization and the Gains from Trade.’ In Trade, Growth, and Economic Policy in Open Economies, edited by K.-J. Koch, and J. Klaus. Berlin: Springer.

- Baldwin, R. 2013. ‘Trade and Industrialization After Globalization’s Second Unbundling: How Building and Joining a Supply Chain Are Different and Why It Matters.’ In Globalization in an Age of Crisis: Multilateral Economic Cooperation in the Twenty-First Century, edited by R. C. Feenstra, and A. M. Taylor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Baldwin, R., and F. Robert-Nicoud. 2014. ‘Trade-in-Goods and Trade-in-Tasks: An Integrating Framework.’ Journal of International Economics 92 (1): 51–62.

- Baldwin, R., and A. J. Venables. 2013. ‘Spiders and Snakes: Offshoring and Agglomeration in the Global Economy.’ Journal of International Economics 90 (2): 245–254.

- Batra, R. N., and F. R. Casas. 1973. ‘Intermediate Products and the Pure Theory of International Trade: A Neo-Hecksher-Ohlin Framework.’ The American Economic Review 63 (3): 297–311.

- Bhagwati, J., A. Panagariya, and T. N. Srinivasan. 2004. ‘The Muddles Over Outsourcing.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 18 (4): 93–114.

- Crespo, E., A. Dvoskin, and G. Ianni. 2021. ‘Exclusion in “Ricardian” Trade Models.’ Review of Political Economy 33 (2): 194–211.

- Deardorff, A. V. 1979. ‘Weak Links in the Chain of Comparative Advantage.’ Journal of International Economics 9 (2): 197–209.

- Deardorff, A. V. 2001. ‘Fragmentation in Simple Trade Models.’ The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 12 (2): 121–137.

- Dixit, A., and V. Norman. 1980. Theory of International Trade. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dornbusch, R., S. Fischer, and P. A. Samuelson. 1980. ‘Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theory with a Continuum of Goods.’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics 95 (2): 203–224.

- Feenstra, R. C. 1998. ‘Integration of Trade and Disintegration of Production in the Global Economy.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 12 (4): 31–50.

- Feenstra, R. C. 2004. International Economics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Findlay, R. 2008. ‘Comparative Advantage.’ In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Gandolfo, G. 2014. International Trade Theory and Policy. 2nd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

- Garegnani, P. 1990. ‘Quantity of Capital.’ In The New Palgrave: Capital Theory, edited by J. Eatwell, M. Milgate, and P. Newman. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Grossman, G. M., and E. Rossi-Hansberg. 2008. ‘Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring.’ American Economic Review 98 (5): 1978–1997.

- Hamilton, C., and L. E. O. Svensson. 1983. ‘Should Direct or Total Factor Intensities be Used in Tests of the Factor Proportions Hypothesis?’ Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 119 (3): 453–463.

- Hummels, D., J. Ishii, and K. M. Yi. 2001. ‘The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade.’ Journal of International Economics 54 (1): 75–96.

- Jones, R. W., and H. Kierzkowski. 2001. ‘A Framework for Fragmentation.’ In Fragmentation, edited by S. W. Arndt, and H. Kierzkowski. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kohler, W. 2004. ‘Aspects of International Fragmentation.’ Review of International Economics 12 (5): 793–816.

- Krugman, P. 1996. Pop Internationalism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Leamer, E. 1995. The Heckscher-Ohlin Model in Theory and Practice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Studies in International Finance, 77.

- Lin, J. Y., and H.-J. Chang. 2009. ‘Should Industrial Policy in Developing Countries Conform to Comparative Advantage or Defy it? A Debate Between Justin Lin and Ha-Joon Chang.’ Development Policy Review 27 (5): 483–502.

- Metcalfe, J. S., and I. Steedman. 1979a. ‘Heterogeneous Capital and the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson Theory of Trade.’ In Fundamental Issues in Trade Theory, edited by I. Steedman. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Metcalfe, J. S., and I. Steedman. 1979b. ‘Reswitching and Primary Input Use.’ In Fundamental Issues in Trade Theory, edited by I. Steedman. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Milberg, W., and D. Winkler. 2013. Outsourcing Economics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ohlin, B. 1967. Interregional and International Trade. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Petri, F. 2004. General Equilibrium, Capital and Macroeconomics: A Key to Recent Controversies in Equilibrium Theory. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Petri, F. 2021. Microeconomics for the Critical Mind. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Riedel, J. 1976. ‘Intermediate Products and the Theory of International Trade: A Generalization of the Pure Intermediate Good Case.’ The American Economic Review 66 (3): 441–447.

- Samuelson, P. A. 2004. ‘Where Ricardo and Mill Rebut and Confirm Arguments of Mainstream Economists Supporting Globalization.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 18 (3): 135–146.

- Shaikh, A. 2007. ‘Globalization and the Myth of Free Trade.’ In Globalization and the Myths of Free Trade, edited by A. Shaikh. Oxon: Routledge.

- Sraffa, P. 1960. Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

- Steedman, I., and J. S. Metcalfe. 1979. ‘Reswitching, Primary Inputs and the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson Theory of Trade.’ In Fundamental Issues in Trade Theory, edited by I. Steedman. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Subasat, T. 2003. ‘What Does the Heckscher-Ohlin Model Contribute to International Trade Theory? A Critical Assessment.’ Review of Radical Political Economics 35 (2): 148–165.

- Vanek, J. 1963. ‘Variable Factor Proportions and Inter-Industry Flows in the Theory of International Trade.’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics 77 (1): 129.

- Venables, A. J. 1999. ‘Fragmentation and Multinational Production.’ European Economic Review 43: 935–945.

- Wood, A. 1994a. ‘Give Heckscher and Ohlin a Chance!.’ Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 130 (1): 20–49.

- Wood, A. 1994b. North-South Trade, Employment, and Inequality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wood, A. 1995. ‘How Trade Hurt Unskilled Workers.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 9 (3): 57–80.

- Wood, A. 2018. ‘The 1990s Trade and Wages Debate in Retrospect.’ The World Economy 41 (4): 975–999.