ABSTRACT

This qualitative research paper discusses how the material environment of preschool classrooms contributes to early childhood experiences of gender. It applies poststructuralist and posthumanist concepts – primarily Barad’s agential-realism – to analyse ethnographic data extracts drawn from the author’s semi-longitudinal study in a UK nursery. This data focuses on two specific areas of the classroom, the ‘home corner’ and the ‘small world’, and the paper argues that these areas and the objects contained within them can support or challenge/queer gender roles depending on temporal material-discursive conditions. It concludes with specific thinking points for practitioners, arguing that applying these theoretical concepts to explore gender in the early years produces interesting perspectives on how rigid, binary gender roles can be challenged effectively in non-discursive ways within classrooms.

Introduction

In this paper I apply ‘posthuman’ analytic methods and concepts drawn from Barad’s agential-realism (Citation2003, Citation2007, Citation2010) to explore processes of gendering within and through a UK preschool classroom. This entails a focus on non-human objects and materials, however the concern of the paper is to explore how we might support non-normative gender experiences for young children. To accommodate this concern with individual gender experience I draw on Warner’s concept of ‘heteronormativity’ (Citation1991) to explore gendering relations of power through a posthuman lens. Using ethnographic data I interrogate the role that physical environments and objects of play and learning have in producing gender as a phenomenon in early childhood. The data have a particular focus on two areas of the featured classroom: the ‘home corner’ and the ‘small world’, and the objects (or ‘non-human bodies’) that constitute them both materially and symbolically. These areas hold significant interest in relation to gender in terms of their classroom presence and design, however they also bear comparison to the properties and possibilities of their ‘real life’ counterparts in the social world outside the nursery. Data analysis identifies a queerness in early childhood gender experiences characterised by fluidity and temporality in continually shifting relations of power that gender human and non-human bodies. Through this analysis I argue that the physical environment of the preschool classroom has an observable influence on early childhood gender experiences and may contribute to what gender subjectivities are made possible and which are foreclosed. I also draw out specific points of practitioner interest based on my analysis. These include suggestions and strategies relating to preschool classroom content, design, and arrangement that early childhood teachers and schools may find interesting to consider.

Becoming classrooms: why learning environments matter

Active engagement with classroom spaces and areas for learning frequently features in recent pedagogic literature as a key channel for learning in the early years. This focus stems from the significant international impact that progressive and child-centred pedagogies have held over early years education training, policy, and practice. Dewey (Citation1916) and Pratt (Citation1948) placed significant value on the contents and arrangements of the ‘physical classroom’, regarding material stimulation and learning environment as essential to effective pedagogy. This view reaches its zenith in Montessori’s ‘prepared environment’, within which, she argued, the child ‘perfects himself’ through specific apparatus and space (Citation1949, 363). Piaget (Citation1954) further cemented the primacy of physical environment to learning, with the former’s establishment of a holistic cognitive development framework becoming embedded in early years pedagogy. Interestingly, the Reggio Emilia approach to education actually applies a level of agency to learning spaces, characterising classrooms as a ‘third teacher’ (Strong-Wilson and Ellis Citation2007). This radical move points directly towards a posthuman analysis that considers materiality as substantially more than mere backdrop to early years education.

This genesis of pedagogical thought has led to recent guidelines for early education in the UK highlighting the importance of the design and layout of classrooms to learning and development (DCELLS Citation2008). The spaces of preschools and nurseries also create opportunities for social learning that, depending on their design and layout, open certain possibilities and foreclose others to the children who play within and through them; these possibilities are not recognised in the same literature. With ‘gender differences’ in play and learning style so widely reported, accepted, and accounted for in practice guidelines (see, e.g. DCSF Citation2007), it is problematic that this literature does not engage with the matter of how the use of space and place in preschool is contributing to young children’s experiences of gender and the adult-perceived differences of boys and girls that provoke concern and pedagogic reaction in educational discourse (Ivinson Citation2014).

In present-day Wales preschool classrooms are arranged according to the principles of the Foundation Phase curriculum where this productive capacity of classroom and playground spaces is acknowledged. This approach foregrounds the physically and mentally explorative preschool-learner (Siraj-Blatchford Citation1999; Siraj-Blatchford et al. Citation2002). The centrality of the relationship with space and place is presented as such that the classroom itself and its objects seems to emerge as equal to or even surpassing teachers as a learning resource in an enactment of Reggio Emilia pedagogy. In guidance documents teachers become facilitators of children’s becomings with space and matter, observing and assessing their engagements while materiality itself provides learning opportunities (DCELLS Citation2008, 20–21). Despite the emphasis on the material environment as productive for young children’s learning, the possibilities of classroom and playground places and spaces to facilitate particular experiences of gender are not interrogated in this guidance.

To engage in this interrogation, I discuss here two dynamic spaces in a preschool classroom – the ‘home corner’ and ‘small world’ areas – through data extracts featuring children playing together and around each other, in and through these spaces. My analysis concentrates on a perception of temporal gender ‘becomings’ opening up and closing down in relation to the changing social-material configuring of the two areas. To explore the possibilities of a posthuman approach, I do not locate the agency of these gender becomings solely within individuals, but instead perceive it as constituted through the interplay of human and non-human bodies in that shifting social-material (re)configuring, contextualised within the wider world beyond the classroom walls (Barad Citation2003; Massey Citation1994).

Gender and the child subject: theory and research

Traditional understandings of gender in early childhood are located within developmental and/or biological paradigms, centralising the binary sexed body and producing naturalised differential expectations for the behaviours and emotions of boys and girls (Burman Citation2008). Recent research, influenced primarily by the variants of post-structuralism and social constructionism associated with Butler (Citation1990, Citation1993) and Foucault (Citation1980a, Citation1980b) has attempted to counteract this essentialism through exploring how power and discourse affect gender in early childhood.

Gender and early childhood is a field that has flourished in the wake of poststructuralist approaches to power and subjectivity becoming popularised in feminist sociology. Such work has challenged heteronormativity in preschool classrooms and culture (Blaise Citation2005; Davies Citation2003), refused the essentialism of binary conflation of sexed/gendered bodies, and focused on young children’s immersion in discursive notions of gender (Marsh Citation2000; Paechter Citation2007; Wohlwend Citation2009). It has ‘queered’ understandings of gender and early childhood by recognising the flexibility and fluidity of young children’s gender subjectivities, and encouraged challenges to hetero-sexism through creating new non-normative discourses and practices in the classroom and beyond.

This strand of research in early childhood classrooms has explored such diverse topics as the circulation of gender discourse through child and teacher talk (Danby Citation1998; MacNaughton Citation2000; Sheldon Citation1990; Surtees and Gunn Citation2010), pedagogical content such as books and construction materials (Blaise Citation2010; Davies Citation2003; Epstein Citation1995), and cultural content like toys and dressing up clothes (Blaise Citation2005; Taylor and Richardson Citation2005; Wohlwend Citation2009). Poststructuralist theory has created an appreciation for the multiple and contradictory experiences of early childhood, and enabled important interrogations of what kind of ideas about gender (and sexuality) are articulated within preschool policy and practice.

‘Power’ and ‘performativity’ have emerged as key themes within this poststructuralist analysis of gender and childhood, and are frequently used alongside the concept of heteronormativity to understand how gender subjectivities are enacted. In Foucault’s conception of the subject as produced through engagement with a ‘net-like organisation’ (Foucault Citation1980b, 98) of transient relations of power through which individual agency can be enacted, it is in the uptake and rejection of discourses that the subject as a collection of varied and, perhaps, contradictory positionings, is constructed (Foucault Citation1980b, 151). This framework informed Butler’s theory of ‘performativity’ in which the repetition of embodied performances across multiple sites of gender and sexual meaning creates an impression of the coherent gendered subject (Citation1990, 41–42); hence, gender is characterised by doing, not being. This doing produces a binary division of sex (Carrera, DePalma, and Lameiras Citation2012; Fausto-Sterling Citation1993; Citation2003) with correlating ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ gender identities (Sedgwick Citation1990). The concept of heteronormativity (Duggan Citation2004; Warner Citation1991) theorises the way that these gendering relations of power are socially circulated, privileging knowledges that inform verbal and physical performances of heterosexual gender and sexuality. These discourses are particularly powerful in early childhood contexts where heteronormativity is implicitly linked to child protection narratives of innocence that encompasses sexuality and, hence, many aspects of adult gender discourse (Faulkner Citation2011; Robinson Citation2012). The heteronormativity of education throughout childhood and the teenage years has been located as a damaging phenomenon through the rigidity of identities it supports. The hegemony of heteronormative masculine and feminine identities lead to non-normative experiences, feelings, and performances (to use Butler’s term) being ignored, invalidated by a lack of recognition, or actively discriminated against (Epstein and Johnson Citation1998; Gunn Citation2011). Many researchers and educators have expressed concern regarding the negative impact that the heteronormativity of schooling has on children’s’ self-esteem, levels of social tolerance, and attitudes towards relationships and sexuality (Flom Citation2014; McNeill Citation2013; Robinson Citation2005; Robinson and Jones Díaz Citation2005; Surtees and Gunn Citation2010).

These understandings of power and gendered subjectivity are extremely helpful in questioning what sort of ideas about gender are articulated within preschool classrooms, and identifying how children engage with (or defy) gender roles and stereotypes. However, a subject-focused epistemology struggles to capture the complex reciprocity of social relations with space, place and objects. Discussions of how materiality and space impacts gender in early childhood tend to focus on how objects and spaces are discursively gendered in such a way that transmits those discourses to the children using them. They also tend to treat material objects and spaces as static, unchanging in form or meaning, regardless of context.

To better understand how discourse and materiality converge in producing gender as a phenomena, some early childhood researchers are turning to, so-called, ‘posthuman’ approaches to gender. This collection of theoretical approaches decentre the humanist subject and expand analytic scope to include human and non-human, material and discursive bodies (Blaise and Taylor Citation2012; DeJean Citation2010; Holford, Renold, and Huuki Citation2013; Huuki and Renold Citation2016; Osgood Citation2015; Renold and Mellor Citation2013). This enables explorations of fluidity, dynamism, and unpredictability that are often hard to describe within a purely poststructuralist framework that focuses on discourse.

Barad’s emergent subject

Post-humanism broadly seeks to transcend binaries of materiality/discourse and human/non-human to locate phenomena as simultaneously produced by and productive of ‘entangled’ material and discursive bodies, both human and non-human, subject and object. In this paper I engage with these concepts though the theoretical framework of ‘agential realism’ offered by Barad, a theorist commonly aligned with the branch of post-humanism termed ‘new feminist materialism’. This strand of work extends the posthumanist de-centring of the human subject with a non-hierarchical approach to discourse and matter (Coole and Frost Citation2010). Drawing from theories of quantum physics that link with the work of Braidotti (Citation2005), Deleuze and Guattari (Citation2004), Haraway (Citation1991), and Grosz (Citation1994), concepts drawn from Barad are increasingly applied within the field of gender and education (see, e.g. Ivinson and Renold Citation2013; Juelskjaer Citation2013; Lenz Taguchi and Palmer Citation2013; Taylor Citation2013).

Barad provides a holistic theoretical framework (she terms it an ‘onto-epistemology’) that locates both subjects and objects within a ‘timespacemattering’; that is, we become as subjects through our engagement with other material and discursive bodies, including space and time, in a modification of the Deleuzean ‘assemblage’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation2004) that Barad terms ‘entanglement’. Her approach disrupts the unilateral consideration of discourse in experiences and subjectivities by re-emphasising the role of materiality and destabilising fixed, boundaried subjectivity. In ‘timespacemattering’, subjects, objects, time, and space are continuously unfolding in multiple iterations of possibility that open up particular opportunities (to become a particular subject or object) and foreclose others depending on their momentary configurations and the observation of their entanglements. In destabilising the passive constancy of material space, and producing it as a further ‘body in becoming’, this framework develops the approach suggested by Massey (Citation1994) to employ the study of temporal material properties in feminist considerations of gender and spatiality.

Barad’s work explicitly builds on Butler’s theory of performativity to construct an agency of doing and becoming that encompasses these diverse entangled bodies, though Barad does not simply expand human agency to include ‘matter with intent’. She relocates agency as working through materiality and discourse, removing it as a property or possession, stating that ‘agency is a matter of intra-acting; it is an enactment, not something that someone or something has … agency is “doing” or “being” in its intra-activity’ (Barad Citation2007,178). Hence agency, for Barad, becomes more akin to a ‘life force’ or vitalism (Deleuze and Guattari Citation2004, 454) that propels productions of phenomena and can incorporate any human or non-human, material or discursive bodies in its path.

This locates agency as not only contingent on, but co-created by circumstance and context. It provides a framework through which we can understand subjectivity as always emergent – never fixed – and always contingent on human relations with other human and non-human bodies. It prompts researchers to examine material and discursive bodies as complex webs of intra-activity – a recent addition to posthuman vocabulary that bears further discussion. Barads’s ‘intra-action’ is distinct from interactivity as it articulates a continuous becoming of subject/object through entanglement, challenging the notion that fixed, boundaried bodies pre-exist their meeting. This conception of relationality foregrounds complexity, difference, and power dynamics, and constitutes a ‘refusal of privilege’ (Taylor, Blaise, and Giugni Citation2013; drawing from Haraway Citation2008) by focusing on response in relations. In simpler terms, it attends to the temporal ‘how’, rather than the historical ‘why’ of phenomena and subjectivity. The de-centring of subject-privilege in analysis enables a mapping of agency as operative through human/non-human relations. Such an expansion prompts analytic readings that ‘look around’ the human subject, rather than directly at it, in an appropriation of the subjective gaze that reveals otherwise obscured agential entanglements. In other words, to explore ‘intra-actions’, rather than ‘interactions’, means to consider all bodies around a phenomenon as (potentially) equally agential and engaged in production. It does not mean that we, in some way, attribute human subjectivity to non-humans, or that we ought to dismiss our sociological concern regarding human experience. In fact, it is one method of achieving greater clarity as to what relations and responses (‘becomings’) a given human or group of humans experiences at a given time.

In this paper I argue that applying these theoretical concepts in analysis encourages a shift in perspective that proves useful in considering how rigid, binary gender roles may be indirectly challenged in a classroom. By perceiving gender subjectivity as temporal, ‘territorially based’ and ‘environmentally bound’ (Barad Citation2007), we can identify how it is produced through particular co-constituting material-discursive experiences and the subjective shifts and flows of human and non-human bodies. Exploring this approach prompts a rethinking of gendering processes in early childhood classrooms by tracking short- and long-term configurations of subjects, objects, and spaces and locating the often surprising ways that they collide to produce tangible effects on how gender roles are experienced, promoted, and challenged in play. Within the analysis the gendering possibilities of material-discursive intra-activity within classroom space are identified, as well as tangible possibilities to support and to, literally, make space for non-normative gender.

Methodology

The data shared here are taken from field notes I generated during a yearlong ethnographic study of a class of three- and four-year-olds that sought to explore how young children experienced gender in the preschool years. The research site was a suburban nursery attached to a primary school, known here as ‘Hillside’, located in a suburban area on the edge of a large town in Wales, UK. The suburb consisted mostly of affordable and council housing and had one of the highest proportions of workless households in Wales (so high, that I will not report the figure here for purposes of anonymity). There were approximately 25 three and four year old children in the class (20 of whom participated in the study) which ran for three and a half hours in the afternoons, providing the free preschool provision then offered by the Welsh Government. The class was moderately ethnically diverse for the area, with 15% of the class being of black or minority ethnic (BME) origin compared to an average BME population of 6% in the local area and 4% in Wales (ONS Citation2012). The intersectionality of race and gender in this study is the focus of a paper currently in preparation and is not foregrounded here to enable extended theoretical and practice-based discussion specifically relating to gender.

Data were generated in the form of field notes through participant observation in the classroom, talking and playing with the children. Research practice in this study was informed by debates surrounding research relations of power and researcher positioning (Fine and Sandstrom Citation1988; Gallagher Citation2008). In response to these debates, I endeavoured to act as an ‘adult friend’ to the children, available to help with reading and working but also playing enthusiastically in the classroom and the playground, being primarily engaged in active play with children during the fieldwork and writing up field notes as soon as possible after events occurred.

Though I had not set out to observe materiality and the classroom environment, being initially focused on discourses and social constructions of gender, though the data I generated it soon became impossible to ignore the significant impact of the children’s’ learning environment. The classroom and objects within it seemed to take on a reciprocal relationship with gender, being simultaneously produced by and producing it, in a manner that was similar to what I expected to (and did) find in the children themselves. The remainder of this paper describes and discusses this revelation and its consequences for analysis.

Worlds apart: the home corner and the small world

This section discusses the material features of two spaces in the nursery: the home corner and the small world. I then share data extracts describing some children’s encounters with those spaces and explore how gender is produced and changed through those encounters.

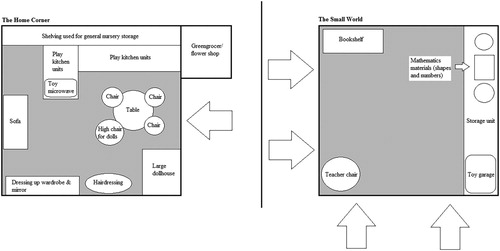

The home corner and the small world were two of the most-used areas of the classroom and were significantly different in terms of their spatial and material features. The home corner, as the name suggests, was themed around homemaking, caring, and dress-up play. Its contents and layout are broadly similar to the descriptions of such spaces around the world as documented in countless research studies and are shown in . The space was filled with furniture and toys, and was always cluttered and usually messy, with dolls, cutlery, and dressing up outfits strewn around the floor and the surfaces covered in utensils and accessories. It was also used as a storage area for nursery books and toys that were not being used and there was a large, high shelf out of the children’s reach dominating one wall above the kitchen units holding these items. Located in a secluded corner, with three permanent walls enclosing it, visibility from the rest of the nursery was significantly limited and, indeed, the home corner was very rarely directly monitored by teachers.

Figure 1. The home corner and the small world floor plans.

Note: Arrows indicate the lines of sight available into the areas from the main classroom space.

On the other side of the classroom, the small world differed greatly from the home corner, not only in contents but in layout and visibility. A small shelf filled with storybooks was placed in one corner; a large ‘teacher’ chair was in the other (usually facing towards the small world) and was frequently occupied by a teacher monitoring the classroom activity and talking to children. A low storage shelf held mathematics materials alongside trains, cars, and building bricks. The expansive open space which this sparse furnishing provided was a stark contrast to the home corner’s clutter.

The small world was effectively a public space. It was visible from most areas of the classroom, its lack of furniture creating a spacious open area with nothing to hide behind. This gave the small world a utilitarian feel, defined by its clear, empty carpet, and practical concealed storage. In contrast the home corner was distinguished by its relative privacy; visible only from one side (the right-hand opening illustrated by the arrow in ) it could not be monitored from half of the classroom. The variety of furniture and large play equipment contained within it further hindered visibility and permitted secrecy and shelter from both teachers and other children. The differing location and monitoring potential of the two spaces prompted contrasting styles of play from their occupants.

There are obvious parallels here between the properties of these spaces and their ‘real world’ counterparts (public, visible space, and private, personal home environments. For further discussion of the gendering of public and private spaces, see Connell Citation1995; Massey Citation1984). The enclave of the home corner ensured that one was much less likely to be disturbed by other children or regulated by teachers than in other areas of the classroom. Its material layout and positioning protected long, complex imagination play where groups of children could cluster out of sight and earshot from the rest of the classroom. These properties also enabled it to be used as an effective ‘withdrawal space’ by individual children (Skånfors, Lofdahl, and Hagglund Citation2009), however the small world area enabled occupants to be constantly monitored, so playing in this area meant accepting this surveillance. It also suggested that those who wished to play in the area needed to be monitored, the implication being that play in the small world was likely to be more disruptive and/or potentially violent than that in the home corner. The result of this was that violent conflicts tended to occur more in the home corner.

Over the school year the home corner became perceptively ‘messier’ at the end (and, hence, beginning) of the day – more cluttered and overflowing than it had been when I entered the nursery. Faced with the impossibility of keeping this space tidy, both children and teachers gradually accepted a state of continuous chaos and objects migrated from hidden storage to public view. Clothes were not hung as neatly, often not at all, simply shoved into corners by the dressing up box. Kitchen accessories that started out living in cupboards rested acceptably on surfaces overnight. The unmanageability of the space was established while the small world remained static, looking identical throughout the year.

Gender, space, place, and play

I record in my field notes that over the school year, boys started to avoid the home corner and girls the small world, until by the end of the summer term the small world was primarily populated by boys and the home corner by girls. This observation prompted my interest in what was actually happening during the children’s play in these areas and how it might be impacting their gendering experiences. However, while much work focuses on interactions between children, this paper explores intra-actions between the children and the physical environment of these areas. To understand why and how these spaces matter for gender experiences, this paper applies Barad’s distinctive approach to space and place, dissolving the hierarchic concern positioning subjects above objects, and discourse above matter in a radical disruption of temporality, linear causality, and possessive agency. Barad’s approach leads us to consider all bodies involved in a spatial/temporal moment as entangled in an agential collusion where subject(ivities) and object(ivities) become distinct through their intra-activity with each other. In other words, we are not boundaried subjects that move through external space and time, cumulatively developing as we do so, but rather continuously become-as-subjects through ongoing engagements with diverse material-discursive bodies. Conducting analysis in his fashion prompts an understanding of gender as an iterative, fluid, and multiple phenomenon, inextricable from the material-discursive configurations of its emergence. To enact this approach, the data analysis offered here explores how particular iterations or formations of gender emerge within subjective experience as entangled bodies intra-act and produce possibilities for past, present, and future gendered selves. I identify what possible gender becomings are opening and closing, being supported and being challenged, as the children intra-act with play objects within these classroom spaces.

The tower

In the data extracts that follow, children are observed playing in each area of the classroom in ways that produce gendering effects. In Extract One, a group of boys use the materials in the small world to build a tall tower in the middle of its carpet. I produced this extract late in the school year when the gender division in the occupation of classroom space was at its strongest levels, and most girls spent very little time in the small world.

Extract One

Jack, George, Ethan and Adam are all building together with the giant Lego bricks. Sally tries to join in but Jack gives her a few bricks and tells her to go and build in the corner. I ask him why she can’t build with them and he says it’s because she won’t build it right … Jack is in charge of the building project and directs the other boys, telling them off when he thinks they aren’t building correctly. Once the tower is quite high, Daisy, without asking, grabs a doll and puts it on top of the tower. Ethan looks up for a moment, then stops building and grabs a doll himself, perching it on top to join Daisy’s and then they start making the dolls walk around on the tower. Jack stands up to protest, ‘Everyone stop! Stop doing silly things! This is a writing table so stop, okay? Okay? I said, okay?’ Jack then has a bit of a tantrum and tells everyone to clear off his tower, then he and George start drawing on top of it with paper and pencils from the real drawing table.

The tower does not pre-exist this extract but comes to matter during its events, being constructed from the giant Lego-style bricks that lived in the small world. How these bricks are used, and who uses them, saturates the emergent tower with gendered meaning: bricks that are to constitute the tower are in the hands of boys, while those which Jack allows Sally to take go with her away from the tower and into a corner, becoming invisible in the field notes I go on to produce. Therefore, the bricks that make up the tower produce gendered relations of power in several ways: they carry a material weight that forms a large, strong, and visible object at the centre of the discursively masculinised small world area. They also carry a symbolic weight that represents the boys who are engaged in the tower building and the girl, Sally, who is excluded to the periphery of the entanglement, literally and figuratively. There is a third obvious allusion here in the tower’s embodied phallic materiality.

In these three ways, the presence of the gendering tower anchors an assemblage of the small world as a ‘boy space’, whilst simultaneously increasing its visibility and prominence in the nursery space, demanding attention and admiration for its increasing height and complexity. The ability of the tower to become so high and complex is mediated by Jack, who acts as a gatekeeper to protect and encourage its growth. Meanwhile, Jack’s ability to divert Sally away from the tower is supported by a temporally bound masculinity that emerges in the small world space, characterised by the material and temporal features described above. However the attention that the structure garners has an effect apparently unanticipated and undesired from Jack’s point of view: just as the boys start to run out of bricks, and the building activity tails off, the tower attracts Daisy and her plastic baby doll from outside of the small world.

The introduction of Daisy and her doll, already in entanglement, to the tower offers a significant disruption to the activity, and it is this moment where the stable, boy-space of the tower becomes a liminal space of gender disruption, creating a metaphysical borderlands where the contents and play-styles of the home corner engage directly with the small world. The doll has transitioned from the home corner, where the dolls are kept on a low sofa in a jumbled pile of limbs and torsos. Already symbolically feminised and strongly associated with young girls, it then becomes an effective avatar for Daisy’s own girl-body, who leaps on the opportunity to dance (her doll) on top of the tower. The immediacy and presumption with which she does this spontaneously creates a purpose for the tower – a stage – with a taken-for-grantedness that consumes any prior trajectory and co-opts its phallic visibility to instead act as a convenient stage for the doll and its femininity. Daisy’s doll therefore diverts and questions the masculinity of the small world and its building activity, (re)configuring the space to enable a queerness to emerge where normative masculinity and femininity are (temporarily) undercut.

The challenge to the emergent binary gender subjectivities that the tower supports, escalates further as one of the boys, Ethan, is apparently captivated by the dancing doll and abandons his building to join in this subversion. Here, the possibilities of gender experience in the small world are queered through its entanglement with the material features and (re)configurings of the non-human bodies of the dolls. While the tower alone formed a stable anchor for boy-gender the dancing doll exerts a power in creating this liminal, gender-queer entanglement that clashes together the symbolism of the phallic and the mother. It breaks apart and becomes something new from its shards – something non-binary and tangibly joyful in the freedom that Daisy and Ethan experience. In doing so, the home corner, embodied by the doll-Daisy entanglement, and the small world, embodied by the tower-Ethan entanglement creates a scenario where Ethan feels able to disregard the activities considered socially desirable for his genderFootnote1 and enjoy a rebellion that irritates his male peers. Then, as suddenly as it begins, the intrusion stops with Jack’s protest.

The emotional reasoning behind Jack’s angry outburst is beyond the scope of this analysis; to speculate on this would mean zooming out from the micro-detail of the moment and accommodating discourses and circulating powers that feed into the scenario produced here. It would include a consideration of Jack’s ethnic status as a child of middle-class Eastern European migrants, whose mother revealed in interview data not discussed here the family’s traditional values relating to gender and her masculine ideals for her son, who looked up to his successful skilled labourer father. It would also involve talking to Jack and requesting self-reflection, something which a four year old would find extremely challenging and this is not attempted here. What can be approached analytically is the temporal context and effects of his intervention, and subsequent activity (the displaced or, at least, disrupted possibilities of intersectional analysis entailed by a new materialist approach are significant here. See Ahmed Citation2008 and Hinton, Mehrabi, and Barla Citation2015 for further discussion of this). While the gendering tower entanglement may temporarily exist in a liminal, gender-queer space, its material location in space and time remains in the small world. The context all this activity remains, therefore, a stable gendered apparatus engaged in producing a boy-space, drawing on discursive and material features associated with masculinity to affirm it. It would take radical and consistent reconfiguring to shift the terms of this boy-space to a non-binary-space and the dancing dolls are not enough to disrupt its trajectory. The strength and persistence of the emergent boyness of this material space lends itself to Jack to support a reclaiming of the tower, and its final shift of form to ‘writing table’ and he draws on this to reject the carnivalesque possibilities of the dolls and their gender-queering. The extract closes with Jack and George huddled over the top of the tower-table, using their physical bodies to close off the liminal space to intrusion and rearranging it once more as a heteronormative ‘boy’ assemblage. This shift back to a ‘productive’ activity (in that the performance of writing aligns with ‘real work’ in the way that dancing does not) mirrors the traditional value of ‘proper jobs’ in discourses of heteronormative masculinity that simultaneously devalue ‘women’s work’ (McDowell and Massey Citation1984).

The dynamic movement of the dolls from the home corner into the small world entails a challenge to the binary gendering of these spaces that enact boundaries around what subjectivations can be pursued and which are rejected. The subjective effects of this material disruption suggest that a non-linear approach to arranging and filling early childhood classrooms may be productive in challenging gender binaries and stereotypes, not simply enabling but prompting freedom of gender expression.

The teapot rebellion

The next data extract describes another, more light-hearted and, yet, violent conflict involving Jack, Daisy, and dolls that takes place in the home corner:

Extract Two

After carpet time I hear a commotion in the home corner and go over to investigate. The first children I encounter are Jack and Ethan, who are dressed up in the wolf and lion costumes respectively, growling and roaring with hands raised up like claws. The units of the home corner have been lined up a short distance from the back wall and behind these, the targets of the boys’ performance, are Maya, Daisy, Caitlin and Chloe, crouching, peering over the top at Jack and Ethan, laughing and shouting hysterically. The boys stalk around the units, coming closer and closer, while the girls become increasingly hysterical until eventually they begin to fight back. The sofa sits near to where they are hiding and is filled with baby-dolls which the girls start to throw at Jack and Ethan like missiles: a funny sight. Daisy starts grabbing the nearby plastic kitchenware and utensils, hurling first some cutlery and then a cup. She finds a red teapot and, emboldened by her new weapon, moves to the front of the group to threaten the boys away, brandishing the teapot fiercely. Jack and Ethan do indeed back away in mock fear but Daisy soon throws the teapot at them and her weapon is lost. Caitlin, following Daisy’s plan, grabs a wooden spatula and replaces Daisy at the front of the group, while Maya continues to throw dolls and Chloe puts her hands to her face, screaming in terror and laughing with delight in equal measure. Just as potential weapons are running low, and the boys are closer than ever to the group, still growling intently and reaching out to scram the girls, a teacher shouts across the classroom, irritated by the loud noise emanating from the home corner, and the chastened children disperse as another teacher announces it is time to go outside to play.

The home corner often acted as a locus of violence in the nursery and many physical conflicts occurred in the space, both serious and playful (tears and tantrums were also most likely to occur there as a result). The privacy it offered evokes the contexts of ‘real life’ domestic spaces which provide a ‘capacity to conceal’ violence and oppression within their material and discursive walls (Miller Citation2005; drawing from Wigley Citation1993). This particular light-hearted conflict is a continuation of the ‘monster’ narrative which informed much of the children’s physically active play, including chasing, capturing, and wrestling. It was rare for girls to be the monster in such games and these games were usually instigated by one of several boys who would start roaring at groups of other children and bring their hands up to their shoulders to act as claws. This action was rarely ignored and the children (along with others who had recognised the start of the game and wished to take part) would run screaming and laughing, searching for somewhere to hide. Girls tended to take on the ‘victim’ roles in monster games, though at least one or two younger boys would often be included as well.

Where in the previous extract the dolls emerged as symbolically laden with femininity, here the animal costumes suggest an intrusion of masculinity into the feminised home corner space. The introduction of the animal costumes was relatively recent and their presence had reinvigorated the monster game. The full transformation of appearance they offered – most with sharp (felt) fangs and fierce eyes – enhanced the wildness and aggression of the monster character and they immediately achieved a level of popularity with boys that rivalled the attraction of girls to the many princess dresses that were already provided for dress-up play. Here the employment of the wolf and lion costumes by Jack and Ethan creates the monsters more aggressively and threatening than mere motions and noises might have managed. Thus these cloth objects facilitate an enhancement or extension of accessible masculinised power, transforming the possibilities for subjective-becomings by providing a range of supportive violent symbolism to draw from in the gendered enactments of the monster game.

The extract is characterised by constantly shifting subject positions of power: though the girls initially flee to the units out of (mock) fear, they quickly become a fortress which they actively defend (forming an equivalent tower-space), and then a trap as weapons run out. Though Chloe hides and screams, the other girls take active measures to protect themselves and the disarray of clutter in the home corner, intended for the enactment of nurturing, caring activities, becomes violent and dangerous weaponry, aggressively wielded. Most unruly of all, the baby dolls laying in a pile on the sofa become missiles flying through the air. In each of these extracts, dolls representing babies – helpless and vulnerable, intended to prompt care and love – become tools of subversion and violence. Their transformation echoes the possibilities variously enacted by the girls in their defence of the home corner: though Chloe chooses to locate herself as a highly feminised victim, screaming and cowering excitedly in the corner, the other girls break away from the victimhood suggested by the animal-boys’ pursuit to become aggressors themselves.

Conclusion

The home corner and the small world provide settings imbued with gendering relations of power that work on and with the children in the classroom in material and discursive ways. The focus on effects rather than causes, prompted by Barad, entailed an analysis on how gender emerges in (re)configurations of human and non-human bodies rather than where it comes from, producing a temporal displacement that looks to the consequences of gendering intra-activity on those bodies in entanglement. When considered as a performative phenomenon, gender is not matter or a discourse that interprets matter but is something that comes to matter through the iterative becomings of subjects and objects in space and time. An analysis based on this perspective recognises the flexibility and transformative capacity of gender, rather than viewing it as an inherent property of bodies or a monolithic pre-existing law that governs social behaviour.

This analysis has revealed points where the emergence of binary gendering was subverted or encouraged. By treating gender and gendered subjectivities as temporally emergent rather than pre-existing in children’s experiences, we move away from understandings of children as passive sponges for discourse, and instead locate them in dynamic entanglement with a variety of human and non-human ‘others’ with which they play and tussle in producing gendered early childhoods. For those who wish to challenge rigid and heteronormative gender stereotypes, this expands our focus from thinking purely about what ideas surround children, to considering what opportunities and possibilities for gender enactments surround them.

While the underlying theory with its new vocabulary can be obfuscating, using agential realist theory to explore gender as it emerges through material and discursive channels is a highly practical approach for political and educative application through the ability to identify multiple points of potential intervention. Jones (Citation2013) argues that applying Barad in analysis is helpful in finding potential points of resistance and change as rather than bodies carrying the weight of pre-existence they become anew with each moment. It is this potential of new materialist approaches to identify new points for change, where different becomings are possible that enable young children to experience gender outside of regulative heteronormative boundaries, which makes this theoretical work so intriguing.

This analysis leads to some specific thinking points that teachers could consider applying in their practice. De-zoning activities by reorganising classrooms in ways that disregard or question ‘common sense’ gender associations of particular activities could produce new and unexpected linkages between those activities. The spaces of the small world and the home corner exerted greater gendering power because of the unproblematised narratives suggested by their content: in the home corner: homemaking, beauty, shopping, and clothes. In the small world: cars, trains construction, and mathematics. Breaking these narratives that lead girls and boys to play only with objects of a similar (gendering) theme may support children whose interests or skills do not fit such a binary pattern, enabling greater freedom of expression outside of gender expectations. Deregulating gendering use of space may also be productive; for example, ‘no princess dresses outside where they might get dirty’ was a rule in the nursery featured here, with the effect of preventing girls enjoying princess-play the opportunity to also be active and boisterous. It may be productive to ask, how are certain choices of gendering play or learning restricting children from engaging in contrasting activities that do not fit heteronormative gender roles? Finally, through carefully selecting and mixing play objects for use in the early years classroom, teachers may be able to discourage gender segregation in engagement with those objects. If there is a box of vehicles, do they all evoke a powerful, active heroic narratives indelibly linked to heteronormative masculinity (such as fire trucks, police cars, bulldozers) or are vehicles provided which allow for play themed around caring and creative narratives (such as a pet ambulance, a delivery van, or a family vehicle like a camper van)? If children choose to play with vehicles, it is then not made necessary for them to act as a strong, powerful hero which boys may feel more encouraged to pursue than girls. Providing diversity of play and learning objects and spaces supports both boys and girls in accessing a diversity of subjective experiences, including those which challenge the normativity of gender stereotypes. Therefore it is important that when pedagogic guidelines argue for the strong impact of classroom design on learning, they should also account for the social learning opportunities provided and ensure that they promote an agenda of equality and diversity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Jennifer Lyttleton-Smith is a researcher at the CASCADE Children's Social Care Research and Development Centre. Her current interests include marginalised childhoods, subjectivities, wellbeing, and outcomes for care-experienced children and young people.

ORCID

Jennifer Lyttleton-Smith http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0704-2970

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this particular nursery, new boys and girls seemed to play with the home corner dolls in equal amounts but as they grew older boys stopped engaging with them so much; by Ethan’s age at this point in the year, it was unusual for a boy – including Ethan – to elect to play with the dolls.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2008. “Open Forum. Some Preliminary Remarks on the Founding Gestures of the ‘New Materialism.’” European Journal of Women’s Studies 15 (1): 23–39.

- Barad, K. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3): 801–831.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. 2010. “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/Continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come.” Derrida Today 3 (2): 240–268.

- Blaise, M. 2005. Playing it Straight!: Uncovering Gender Discourses in the Early Childhood Classroom. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Blaise, M. 2010. “Kiss and Tell: Gendered Narratives and Childhood Sexuality.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 35 (1): 1–9.

- Blaise, M., and A. Taylor. 2012. “Using Queer Theory to Rethink Gender Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Young Children 67 (1): 88.

- Braidotti, R. 2005. “A Critical Cartography of Feminist Post-postmodernism.” Australian Feminist Studies 20 (47): 169–180.

- Burman, E. 2008. Deconstructing Developmental Psychology. 2nd ed. Hove: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 1993. Bodies That Matter. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carrera, M. V., R. DePalma, and M. Lameiras. 2012. “Sex/Gender Identity: Moving Beyond Fixed and Natural Categories.” Sexualities 15 (8): 995–1017.

- Connell, R. W. 1995. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Coole, D., and S. Frost. 2010. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Danby, S. 1998. “The Serious and Playful Work of Gender: Talk and Social Order in a Preschool Classroom.” In Gender in Early Childhood, edited by N. Yelland, 175–205. London: Routledge.

- Davies, B. 2003. Frogs and Snails and Feminist Tales: Preschool Children and Gender. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- DCELLS (Department for Children, Education, Lifelong Learning and Skills). 2008. Foundation Phase: Framework for Children’s Learning for 3 to 7 Year Olds in Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government.

- DCSF (Department for Children, Schools and Families). 2007. Confident, Capable and Creative: Supporting Boys’ Achievements. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

- DeJean, W. 2010. “The Tug of War: When Queer and Early Childhood Meet [online].” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 35 (1): 10–14.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 2004. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated from the French by B. Massumi. London: Continuum ( Originally published in 1980).

- Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan.

- Duggan, L. 2004. The Twilight of Equality: Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Epstein, D. 1995. “Girls Don’t do Bricks’: Gender and Sexuality in the Primary Classroom.” In Educating the Whole Child: Cross-curricular Skills, Themes and Dimensions, edited by J. Siraj-Blatchford and I. Siraj-Blatchford, 56–69. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Epstein, D., and R. Johnson. 1998. Schooling Sexualities. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Faulkner, J. 2011. The Importance of Being Innocent: Why We Worry about Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fausto-Sterling, A. 1993. “The Five Sexes: Why Male and Female Are Not Enough.” The Sciences 33 (2): 20–25.

- Fausto-Sterling, A. 2003. “The Problem with Sex/Gender and Nature/Nurture.” In Debating Biology: Sociological Reflections on Health, Medicine and Society, edited by G. Bendelow, L. Birke, and S. Williams, 123–132. London: Routledge.

- Fine, G. A., and K. L. Sandstrom. 1988. Knowing Children: Participant Observation with Minors. Vol. 15 of Qualitative Research Methods. London: Sage.

- Flom, J. 2014. Heteronormativity in Schools [Online]. Edutopia. Accessed December 19, 2016. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/heteronormativity-in-schools-jason-flom

- Foucault, M. 1980a. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. Translated from the French by R. Hurley. London: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. 1980b. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Writings 1972–1977. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

- Gallagher, M. 2008. “‘Power is not an evil’: Rethinking power in participatory methods.” Children's Geographies 6 (2): 137–150.

- Grosz, E. 1994. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Gunn, A. C. 2011. ““Even If You Say It Three Ways, It Still Doesn’t Mean It’s True”: The Pervasiveness of Heteronormativity in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 9 (3): 280–290.

- Haraway, D. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Haraway, D. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hinton, P., T. Mehrabi, and J. Barla. 2015. New Materialisms_New Colonialisms (Online self-published work-in-progress). http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/44393079/Barla__Hinton__Mehrabi_-_New_Materialisms_New_Colonialisms___Position_Paper.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId = AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires = 1488562420&Signature = IJAcgrVQQBri9IkYqzbmAoaC23g%3D&response-content-disposition = inline%3B%20filename%3DNew_materialisms_New_colonialisms.pdf.

- Holford, N., E. Renold, and T. Huuki. 2013. “What (Else) Can a Kiss Do? Theorizing the Power Plays in Young Children’s Sexual Cultures.” Sexualities 16 (5–6): 710–729.

- Huuki, T., and E. Renold. 2016. “Crush: Mapping Historical, Material and Affective Force Relations in Young Children's Hetero-Sexual Playground Play.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 37 (5): 754–769.

- Ivinson, G. 2014. “How Gender Became Sex: Mapping the Gendered Effects of Sex-group Categorisation Onto Pedagogy, Policy and Practice.” Education Research 56 (2): 155–170.

- Ivinson, G., and E. Renold. 2013. “Valleys’ Girls: Re-theorising Bodies and Agency in a Semi-rural Post-industrial Locale.” Gender and Education 25 (6): 704–721.

- Jones, L. 2013. “Children's Encounters With Things: Schooling the Body.” Qualitative Inquiry 19 (8): 604–610.

- Juelskjaer, M. 2013. “Gendered Subjectivities of Spacetimematter.” Gender and Education 25 (6): 754–768.

- Lenz Taguchi, H., and A. Palmer. 2013. “A More ‘Livable’ School? A Diffractive Analysis of the Performative Enactments of girls’ ill-/well-being with(in) School Environments.” Gender and Education 25 (6): 671–687.

- MacNaughton, G. 2000. Rethinking Gender in Early Childhood Education. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

- Marsh, J. 2000. “‘But I Want to Fly Too!’: Girls and Superhero Play in the Infant Classroom.” Gender and Education 12 (2): 209–220.

- Massey, D. 1984. Spatial Divisions of Labour: Social Structures and the Geography of Production. London: Macmillan.

- Massey, D. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- McDowell, L., and D. Massey. 1984. “A Woman’s Place?” In Geography Matters! A Reader, edited by D. Massey and J. Allen, 124–147. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McNeill, T. 2013. “Sex Education and the Promotion of Heteronormativity.” Sexualities 16 (7): 826–846.

- Miller, L. J. 2005. “Denatured Domesticity: An Account of Femininity and Physiognomy in the Interiors of Frances Glessner Lee.” In Negotiating Domesticity: Spatial Productions of Gender in Modern Architecture, edited by H. Heynen and G. Baydar, 196–212. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Montessori, M. 1949. The Absorbent Mind. Chennai: The Theosophical Publishing House.

- ONS (Office for National Statistics). 2012. Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales: 2011. [Online]. file:///H:/My%20Documents/Downloads/Ethnicity%20and%20National%20Identity%20in%20England%20and%20Wales%202011.pdf.

- Osgood, J. 2015. “Reimagining Gender and Play.” In The Excellence of Play, 4th ed, edited by J. Moyles, 49–60. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Paechter, C. 2007. Being Boys; Being Girls: Learning Masculinities and Femininities. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Piaget, J. 1954. The Construction of Reality in the Child. New York: Basic Books.

- Pratt, C. 1948. I Learn from Children: An Adventure in Progressive Education. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Renold, E., and D. Mellor. 2013. “Deleuze and Guattari in the Nursery: Towards a Multi-Sensory Mapping of Young Gendered and Sexual Becomings.” In Deleuze and Research Methodologies, edited by R. Coleman and J. Ringrose, 23–40. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Robinson, K. H. 2005. ““Queerying” Gender: Heteronormativity in Early Childhood Education.” Australian Journal of Early Childhood 30 (2): 19–28.

- Robinson, K. H. 2012. “‘Difficult Citizenship’: The Precarious Relationship between Childhood, Sexuality and Access to Knowledge.” Sexualities 15 (3–4): 257–276.

- Robinson, K., and C. Jones Díaz. 2005. Diversity and Difference in Early Childhood Education: Issues for Theory and Practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Sedgwick, E. K. 1990. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: California University Press.

- Sheldon, A. 1990. “Pickle Fights: Gendered Talk in Preschool Disputes.” Discourse Processes 13 (1): 5–31.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I. 1999. “‘Early Childhood Pedagogy, Practice, Principles and Research’.” In Understanding Pedagogy and its Impact on Learning, edited by P. Mortimore, 20–45. London: Paul Chapman.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I., K. Sylva, S. Muttock, R. Gilden, and D. Bell. 2002. Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years: DfES Research Report 365. HMSO London: Queen’s Printer.

- Skånfors, L., A. Lofdahl, and S. Hagglund. 2009. “Hidden Spaces and Places in the Preschool: Withdrawal Strategies in Preschool Children’s Peer Cultures.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 7 (1): 94–109.

- Strong-Wilson, T., and J. Ellis. 2007. “Children and Place: Reggio Emilia’s Environment as Third Teacher.” Theory into Practice 46 (1): 40–47.

- Surtees, N., and A. C. Gunn. 2010. “(Re) Marking Heteronormativity: Resisting Practices in Early Childhood Education Contexts.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 35 (1): 42.

- Taylor, C. A. 2013. “Objects, Bodies and Space: Gender and Embodied Practices of Mattering in the Classroom.” Gender and Education 25 (6): 688–703.

- Taylor, A., M. Blaise, and M. Giugni. 2013. “Haraway’s ‘bag Lady Storytelling’: Relocating Childhood and Learning Within a ‘Post-human Landscape’.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 34 (1): 48–62.

- Taylor, A., and C. Richardson. 2005. “Queering Home Corner.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 6 (2): 163–173.

- Warner, M. 1991. “Introduction: Fear of a Queer Planet.” Social Text 29: 3–17.

- Wigley, M. 1993. The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 97–147.

- Wohlwend, K. E. 2009. “Damsels in Discourse: Girls Consuming and Producing Identity Texts Through Disney Princess Play.” Reading Research Quarterly 44 (1): 57–83.