ABSTRACT

Early marriage and pregnancy hinder global commitment to attain gender parity in education. This article discusses educational challenges experienced by parenting college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. The study qualitatively assessed the effects of COVID-19 on the National Teacher Colleges’ learning environment. On the reopening of schools after the lockdown, colleges were overwhelmed with an increased number of students who returned either pregnant or with young babies. Colleges were not prepared since pregnancy in college is prohibited through denial of on-campus accommodation and other services. Pregnant students were stigmatized, shunned and blamed for having engaged in immoral sexual behaviour and punished for their indiscretions. Pregnant and abandoned is structural gender-based violence that manifests in the physical, emotional, economic and social violence faced by pregnancy and parenting students, the young mothers are abandoned by their families and partners, and are denied child support and other student services. Future studies need to investigate the effects of such tormenting experiences of being abandoned on the academic performance and future parenting decisions of such girls.

Introduction

Attempts to improve access to education as a development goal remain at the top of the global development agenda. Transitions from the Women in Development (1970–1980s), Gender and Development strategies (1990s), and 1990 World Declaration on Education for All (1990), to the present-day global development goals have contributed to strategies to tackle equality in education access, retention and quality of education for women and girls (Chilisa and Ntseane Citation2010; David Citation2017). Core to these strategies addressing the negative effects of early marriage and teenage pregnancy on girls’ education (Monk et al. Citation2021; Okwany Citation2016). Globally, sexual and gender-based violence (SBBV) remains one of the major challenges faced by educational settings and is a major obstacle to efforts to attain gender parity in education (Bhana, Singh, and Msibi Citation2021). This paper presents findings from a study on the impact of COVID-19 on young women attending post-secondary teacher training institutions revealing systemic effects of SGBV on girls’ education.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020 and closure of schools and other educational institutions was among the major responses adopted to slow down the spread and infection rate of the COVID virus (Burgess and Sievertsen Citation2020; de Bruin et al. Citation2020; WHO Citation2020). Shutting schools meant that formal learning and education were disrupted. Uganda is on record for the longest school closure period at nearly 2 years (Angrist et al. Citation2021). At the peak of school closure, for the first time, the world saw more than 1.6 billion students out of school across 190 lower-income countries (UNESCO Citation2020b, Citation2020a). Remote learning increased for those who could afford access to the internet causing a digital divide with children from lower socioeconomic groups in poor countries lacking support to continue education (Azubuike, Adegboye, and Quadri Citation2021). Te related major effect is the increase in the number of children who are unable to read and write which has been projected to rise from 50% to 70%, further worsening the already dire global education divide between low and high income countries (Unicef Citation2022).

Pregnancy and education

Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia rank on top of the regions with the highest teenage pregnancy and early marriage associated with high rates of school dropouts among girls (Gunawardena, Wondwossen Fantaye, and Yaya Citation2019; Unicef Citation2015). African countries have instituted laws that allow girls to stay in or return to school after pregnancy, though with restrictions on when and how to return (Mubatsi Citation2022; Mwangi Citation2021). In most countries, being pregnant while in school results in discontinuation which is a punishment for defying the expected moral behaviours and deterrent measure to avoid setting a bad example to the other girls (Chigona and Chetty Citation2007). These restrictions, coupled with cultural and social norms that shame and blame a girl for being pregnant outside marriage, return to school policies are ineffective with only 5% of girls who become pregnant ever returning to school (Birungi et al. Citation2015; Nyariro Citation2021). There are significant benefits to women and their empowerment associated with girls’ education at every level (Eastwood and Lipton Citation2011; Tiedeu, Para-Mallam, and Nyambi Citation2019) yet efforts to keep girls in school remain hampered by high rates of dropout at lower levels of education (Iddy Citation2021; Undie et al. Citation2015).

Uganda has one of the lowest numbers of children who transition from primary to secondary education with less than 30% transitioning to secondary education and higher education (Candia et al. Citation2018; Nabugoomu Citation2019) translating into millions of school-age girls who become pregnant and never get opportunity to return to school. Young girls engage in risky sexual behaviours due to lack of sexual and reproductive health information and are victims of structural limitations and barriers to address SGBV (Lundgren and Amin Citation2015; Muhanguzi Citation2011). While not all unplanned pregnancies outside marriage may be attributed to SGBV, being pregnant at a young age, outside marriage or at worse as a student, exposes girls and young women to SGBV. Girls who drop out of school due to pregnancy tend to be abandoned by their families and the men who made them pregnant (Mubatsi Citation2022). This puts them at risk of sexual violence and harassment as they fend for themselves and their babies (Nyakato et al. Citation2021). The long-term effect of adolescent pregnancy is the intergenerational transmission of poverty for women and their children as they lose the opportunity to better their economic status through education (Salvi Citation2019).

Pregnancy before or outside marriage

In traditional Africa, pregnancy before or outside marriage is harshly punished and is blamed on the girl for failure to adhere to the expected sexual morals and behaviours. Punishments range from excommunication, forced into marriage, and in some cultures girls could be punished by death (Ninsiima et al. Citation2018), boys and men are however not blamed, women and girls take full responsibility. The girl’s pregnancy brings shame and blame on the family for not properly raising her; because of this, pregnant girls lose chances of ever getting ‘properly’ married (Neema et al. Citation2021). Controlling girls’ sexuality is structurally interwoven with a traditional patriarchal system, including the reproduction role associated with womanhood (Chilisa and Ntseane Citation2010; MacDonald Citation2012). It’s this view that contradicts victimization and the failure to hold men and boys accountable for pregnancy (Ninsiima et al. Citation2018). Poverty, religion and culture are the primary proliferators of vulnerability to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and repulse attempts to offer girls a chance for education after pregnancy (Salvi Citation2018; Yakubu and Salisu Citation2018).

SGBV and learning environments

School-based SGBV is the most destructive social disorder associated with unsafe learning environments affecting all learners (Agardh, Odberg-Pettersson, and Östergren Citation2011; Parkes et al. Citation2016). In school settings, more girls than boys experience SGBV, negatively affecting their enrolment, academic performance and completion causing gender inequality in education (Badri Citation2014; Devries et al. Citation2014). Unsafe learning environments not only constrain women’s pursuit for higher education but propagate patriarchal attitudes and justification to control freedom of movement as a disguise for the protection and safety of women and girls. Girls’ access to education in the global south is influenced by what Salvi (Citation2019) described as push and pull factors: pull factors include household poverty, gendered labour demands, health, gendered cultural regulations and cost of education while push factors are SGBV, gendered curricula and school practices that position girls to attain less than boys.

Theoretical underpinnings

Post-colonial approaches to gender in education specifically African feminism and positive youth development have been adapted to provide critical dimensions and debate that are relevant to the experiences of pregnant and parenting students in Uganda. The paper presents an example of structural limitations to access education after pregnancy by putting into perspective the escalation of pregnancy among pregnant students in NTCs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. The application of liberal feminism theories to girls’ education and pregnancy has limited focus on legal and institutional frameworks to promote equity. The paper underscores the need for flexibility towards dealing with specific cultural contexts (Chilisa and Ntseane Citation2010) and expound from narrow views on women equal opportunities to education, by adapting to African feminism, the paper emphasizes the understanding, regulation, resistance and activism in educational policies and programming. Unlike Western Feminism, African Feminism owns it’s origin to the struggles against crosscutting issues that surround patriarchal power and multiple experiences of colonialism including women’s resistance to western hegemony and appreciates the transformative strides made in the political, economic and socio-economic spheres (Ahikire Citation2014).

By referring to both feminism and the positive youth development (PYD) frameworks, the paper discusses the need to secure young people’s well-being. PYD provides perspectives for comprehensive sexuality education and promotion of positive and protective sexual behaviours as an alternative to abstinence only education (Romeo and Kelley Citation2009) and is suitable because of its application to sexual health and well-being including the management of high rates of early pregnancy among school-going girls (Benson et al. Citation2006; Lerner et al. Citation2011). In addition, working with PYD provides a theoretical linkage to the contemporary increased focus on teenage pregnancy within education policy and programming, emphasizing attention to individual cognitive, emotional and behavioural engagement with family, school and the community. As opposed to western feminists, proponents of the global south gender theories in education posit the existence and recognition of the global gender disparities pointing to harnessing resilience factors in gender and power relations (Fennell and Arnot Citation2008).

Methods

The data for this paper were generated from a qualitative study on the assessment of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on SGBV in the five National Teacher Colleges (NTCs) which is a sub-study of an ongoing project on improving secondary teachers’ education in the NTCs. The project was implemented based on evidence generated from a study in 2019 on the prevalence of SGBV in the NTCs and the Business Technical and Vocational Education Training (BTVET) institutions in Uganda. SGBV is ‘any act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and is based on gender norms and unequal power relationships’ (UNHCR Citation2021), encompassing threats of violence and coercion. SGBV can be physical, emotional, psychological or sexual in nature, and take the form of a denial of resources or access to services.

Setting

In Uganda, higher education is offered at universities and other tertiary institutions, such as polytechnics, teacher colleges, business, vocational and technical colleges, and colleges of commerce. There are both public/state-owned and private institutions with a great proportion of the ownership by the religious foundation bodies and other members of the private sector and civil society. The study was conducted in NTCs of which Uganda has five regional NTCs. Participants were recruited from the north and northeastern Kaliro and Muni colleges. Uganda like most countries in the region lacks evidence on SGBV in higher institutions of learning.

Data collection

Six gender-specific focus group discussions (FGD), including female and male groups were conducted totalling 06 FGDs. Participants included 43 students and 19 teaching and non-teaching staff (total N = 26 females and N = 32 males) and students and staff were interviewed separately. Data were collected in January 2022, a few weeks after Uganda’s official reopening of schools after about 18 months of school closure as a prevention measure for COVID-19. The discussions centred on personal and community SGBV experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The FGD data were supplemented with data from other project activities, specifically the strengths-based participatory assessment of the safety of the learning environment and mapped existing resources for prevention of SGBV in the 5 NTCs conducted between November and December 2022. The participatory assessment activities involved 230 people included teaching and non-teaching staff, students and selected community resource persons participating in the other project activities.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the transcripts for each FGD and other project activities data sets. Thematic analysis is a qualitative analytic method used to search for themes or patterns, and in relation to different epistemological and ontological positions in given data sets (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). First, the transcripts were independently coded by three members of the research team. A research team meeting was held to come to consensus on a code list. Together, the team merged related codes to create categories, the categories were further merged to generate themes and these were checked against the data to ensure their salience and fit. A code book was created with products from all phases of analysis and memos were written on each salient theme with interpretation and possible inferences. Data exemplars were generated for each theme. They were then checked for linkage and relevance to the study aim. Overarching themes that best described the overall effect of COVID-19 on SGBV in NTCs were identified and related to generate a pattern.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics’ Committee of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST 2021-289) and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST) (SS1487ES). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study during enrolment. Permission was also obtained to allow recording of the interviews and FGDs. Privacy and confidentiality were maintained during the data collection process by selecting an agreed on convenient location for the interviews and FGDs within the college, a place where participants felt comfortable to express their views.

Results

There were three overarching themes with parenting students’ experience of abandonment after pregnancy, as the major theme. The other themes were: COVID-19 lockdown consequences and College responses to increased numbers of parenting students. The following quote represents the burdens of pregnancy experienced in the NTCs after COVID 19:

the impact of the 2 years lockdown will be with us for a long time, for example when our students came back, some of them were already pregnant and this pregnancy was a result of the lockdown, and it has impacted their academic performance. I am saying this because I had to investigate a student who was in the hospital to give birth. (Staff, Muni NTC).

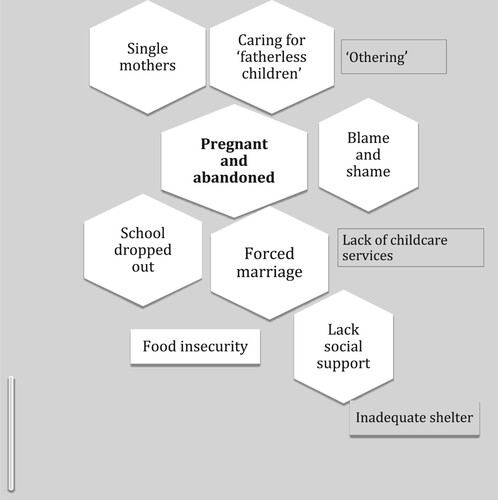

Abandonment after Pregnancy is characterized by the burdens of being a single parent, including parenting babies whose fathers are not known publicly. The students were continuously faced with voices of blame and shame for giving birth outside marriage. Not all students who became pregnant returned to school; some dropped out and never returned to college to complete their studies. Others were forced by their families to get married to the men who made them pregnant. Those who chose to return had to silently bear the burdens of being a single parent, including ‘othering’, that is being subjected to demeaning conditions, including being treated differently and suffering from lack of child care support and food insecurity. Parenting students were forced to live in unsafe shelter themselves and their children.

Abandoned to be a single student mother in care of ‘fatherless’ children

Parenting students bore burdens of being single mothers, and for many of them, their families stopped providing and supporting as a form of punishment. Some needed to find their own school fees, meet childcare needs and were continuously humiliated. Men and boys responsible for the pregnancy were either unknown or unrevealed, the girls feared revealing in fear, and they wanted to protect the perpetrators being punished or imprisoned. They feared to blamed and victimized by the perpetuators both in the colleges and community. They didn’t want to freely talk about the fathers of their children mostly because they are not present, supportive or the pregnancy was a result of SGBV, and revealing the men would result in forced marriages. Those who were raped may not have known who the fathers of the children were, others were forced by circumstances to abort the pregnancy. Respondents described these circumstances:

Some of older men in our communities took this Covid19 situation as an advantage to sexually abuse young girls. It reached an extent whereby men would come in the name of helping and promising that they will provide everything. The situation was so bad that cases of abortions increased, some girls did not have a choice but to just abort and move on with their lives (Female Student, Muni NTC).

The boy ended up denying the responsibility and the girl had to use part of her school fees to cater for herself, so there was struggle to raise the school fees. And some girls are even denied access and necessities from home because she became pregnant when the parents are not aware and when they become aware, they cut off their support (Male Student, Kaliro NTC).

Blame and shame by family and community

Because pregnancy outside marriage brings shame to the family of the girl, pregnant girls often experience abandonment by family, sexual partner/person responsible for the pregnancy, friends, family, school and community. Students shared the following:

Being pregnant when one is still in school reduces the chances of ever enrolling for school for girls education is not a ‘right’ so when one gets pregnant they are assumed to have wasted their chances even for other girls in the family and the rest of the community (Female Student, Muni NTC)

At risk for school dropout

Pregnant girls are denied the opportunity to remain in school. Reasons given for drop out: when pregnant, they can no longer concentrate on their studies; they have divided attention, and they are shunned by teachers and colleagues; they dodge lecturers to find school fees and fend for their children.

The issues of pregnancies and abortions have affected students because most students have ended up dropping out of school. For example, imagine a situation whereby someone is impregnated and, in that process, the parents decide to maybe not continue paying school fees and in many cases the person who made her pregnant is either not or will be in hiding, we have seen many such girls drop out of school (Female Student, Muni NTC).

Forced marriages

When students were sent home due to the COVID 19 pandemic, parents feared that girls could get pregnant while out of school and they opted to instead give them away for marriage. Some girls were married off for lack of resources to meet their needs, or in protection against engaging in risky sexual encounters that may lead to pregnancy outside marriage. The following quote is an expression of how forced marriage manifests as a form of GBV:

There was nothing as a girl consenting, when you are pregnant, parents just order you to pack your things and go only to realize, you are in a man’s house, just like that, no agreement, no nothing (Female Student, Muni NTC).

Girls in my village were exchanged for cows by their parents (Female Student, Muni NTC).

Lack of social support

Being pregnant before marriage is synonymous with physical, emotional and financial abandoned by family, the person responsible for the pregnancy, and the community as expressed: being pregnancy is worse than contracting HIV, you are denied everything by everyone (Female Student, Kaliro NTC)

During the COVID-19 lockdown, many young people became victims of SGBV and lacked protective SHR education. This manifested in the high number of unplanned pregnancies among female students. It could be that the students were not equipped with knowledge, skills and awareness about SRH. Pregnant students who were victims found a lack of procedures and awareness about SGBV: In the community and colleges, there are no clear reporting procedures to ensure that the person responsible for pregnancy takes responsibility. A staff at Muni NTC had this to say I shared with a lot of the victims and realized that they young people were not aware of the consequences engaging in risky sexual practices, many after becoming pregnant realized the challenges, I found a poor mother of the parenting student trying to toil up and down with the daughter in the hospital and her fear was the daughter may never be in school again.

Colleges lack childcare services

Student mothers were visibly at the college compound with their babies, babies came to school with their mothers, and mothers juggled the demands of the school with parenting. In most cases, only mothers are talked about without considering the plight of their babies. Some students reported to the school and left their toddlers home without structured opportunities to see and bond with their infants since childcare is not integrated into the college structures. The challenges faced by parenting students extend to their babies, these students have to catch up with the demands of education, family and community. In the following expression is a narration of the children who have to be ‘in school with their mother’, an experience some of them who had babies as they were about to come back, one student was forced by the father to come back to college and carry alongside her child to college, his child was just 8 months. (Staff, Kaliro NTC).

Student mothers are not accommodated in the colleges for fear of setting a bad example for other students who may look at it as normal to give birth while still in school (Staff, Muni NTC).

Increased number of students reporting pregnancy or carrying a baby

NTCs reported an increase in the number of students who reported back to school after the lockdown who were either pregnant or having a baby. More boys, therefore came back to college compared to girls after the lockdown. Many girls ended up with unwanted pregnancies and in forced marriages which denied some of them a chance to return to college and others who went back had the burden to look after their children. These student mothers reported a hard time concentrating in class, sleeping in unworthy places outside the colleges and having to walk long distances to go and attend lectures among college students. A staff at Muni reflected:

The unintended pregnancies have occurred even for primary school-going girls, the abortions have occurred because I have gone to the police and the data is available. I have not heard much about early marriages … I am aware that these students have already been wounded, and wounded in the sense that, they are pregnant, others aborted, and they have gone through a lot.

Lack of parental guidance and support

During the lockdown, many students and their families lost their main sources of livelihood. Some students were forced to open up small businesses to support their families but even these didn’t work due to many restrictions on movement. As expressed in the following quote, families found it hard to look after their children during the COVID lockdown. In cases where parents were away from home for work they lacked time to provide guidance and protection against sexual exploitation including harassment and violence. Students were home with little to do. There was a lack of parental guidance and this created exposure to sexual risk taking and immorality among the children. Staff from Muni said: I think these 2 lockdowns have caused so much GBV compared to before because there are so many reasons which we have already shared for example lack of control. You know during the lockdown children did not have much guidance and counselling, so I think GBV in my community was too much during the lockdown compared to before.

In response to the children’s behaviour, parents became angry, depressed, mentally unstable and lost control over their children while at home. Parents started abusing their children verbally, physically and psychologically. In this case, the children resorted to leaving home and becoming independent. When they became independent, they started looking after themselves at a young age which exposes them to different challenges like financial constraints and men who take advantage of them sexually.

There were instances where some young people were engaged in sex for gain; Students during the lockdown were not getting support from their parents, so they resorted to getting money from older men who took advantage of them.

I went to look for a job by then and that was during the lockdown the woman who was supposed to employ me asked me to have sex with him before she could employ me and that was after a long time of her tossing me around. (Male student, Kaliro NTC)

Lack of resources to meet personal needs

Girls more than boys lack resources to meet their needs; during the lockdown, families lacked enough money to support the needs of their children, especially girls. While some students were able to work to meet their needs, for others it was difficult. When colleges were opened, some female students didn’t report to school because of financial constraints. Some exchanged their bodies for their needs. A student from Muni had this to say the Covid-19 pandemic seasons exposed us to a lot of challenges, majorly the females looked at men as solution makers, thought that being men they are able to find solutions.

Risky sexual behaviours associated with lack of activities to be pre-occupied with

The lockdown was associated with having a lot of free time and lack of activities that preoccupied them; they got involved in risky sexual behaviours. These sexual activities could have exposed them to diseases like HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Male students got engaged in drug use and abuse and it was feared that this could have caused failure to report back to school. For example, a lecturer at Kaliro NTC said personally I have seen peer groups of both girls and boys who later start drug abuse.

Another expressed: Young girls who live alone were victims of GBV and sexual harassment. Some people who did not have money to meet their needs gave in sex for pay, some of these sexual encounters resulted in pregnancy. Some girls were forced to get married, they lost hope of returning to school. (Staff, Muni NTC)

College response to the increased number of students returning to College with pregnancy or babies

Providing improvised accommodation in campus

Accordingly, on-campus accommodation guidelines do not provide for students with babies. All students with families, parenting or pregnant are expected to privately arrange for their place of residence. The available accommodation is mostly outside or off campus, this is intended to separate them from the ‘normal students’. When the government reopened the schools, the standard operating procedures for prevention and management of the spread of the COVID-19 required that colleges limit students’ interactions with outside communities. As such all students including those who were pregnant were required to stay within the college compound. Because of the large numbers, colleges did not have accommodations and services appropriate for parenting and pregnant students, there was no standard way pregnant and parenting students could be provided with accommodation that befits them and their babies or families. They were given improvised structures for accommodation, some of these improvised accommodation spaces that were not fit for babies who were always falling sick. For example: Pregnant girls could share accommodation with the other students, however, the colleges are overwhelmed by the number of student mothers that returned after lockdown. That is why these mother students designated halls are substandard, congested and could be a cause of other health conditions like pneumonia, malaria and typhoid for the mothers and their children (Staff, Muni NTC).

Emotional and material support offered by the colleges

On return to school, colleges prioritized offering psychological and emotional support because of the wide range of SGBV student mothers had experienced. These ranged from lack of protective SHR information, forced marriage, drug abuse and unplanned pregnancies. The following quotes represent the college response mechanism:

These students are provided with college food that they share with the baby sitters. They also get to the college’s the college inevitabilities like water, electricity, and security. This helps the student mothers not to spend money renting unworthy houses outside the colleges (Senior Staff, Muni NTC).

We have to make male students accountable, in some cases the male student who has made a girl student pregnant, they are required to look after the female student and this agreement is reached upon by having a meeting with the family of the 2 parties and the school management. Failure to look after the impregnated student half of the male student’s tuition is cut off and given to the female student (GBV Resource Mapping Exercise, Unyama NTC).

Discussion

While the literature on pregnancy and education tends to focus on adolescents, abandonment experiences among parenting NTC students in Uganda reveal systemic patriarchal oppression that extends to institutions of higher education and the young mother’s resistance to complete their studies. After COVID 19 lockdown, a number of female students reported back either pregnant or breastfeeding, many others reportedly got married. A large number of parenting female students returned to colleges to no accommodation provisions for students with children a state of affairs that uncover another important form of gender discrimination against student mothers in higher institutions of learning. As such we present dimensions of abandonment experienced by pregnant and student mothers comprised of single parenting, lack of childcare services, caring for ‘fatherless’ children, blame and shame, forced marriage, lack of social support, inadequate shelter and food insecurity.

Because of the requirements to open schools safely and prevent the spread of COVID 19 infections, it was necessary that all students find accommodation within the college housing. This would minimize regular interface with the public but one group of students would be isolated; pre COVID 19 any student who became pregnant would have to find private housing outside the college and the college could no longer take responsibility for the pregnant students’ accommodation. Failure to provide housing and childcare facilities to student mothers is consistent with African and Post-colonial Feminist theories on entrenched and systemic discrimination that manifests in patriarchal oppression in education systems and a symbolic representation of roles to reproduce and care for children (Chilisa and Ntseane Citation2010; Salvi Citation2019). This may further explain the widespread unequal access and differential treatment that girls and women face in educational institutions (Bhana et al. Citation2008; Chilisa Citation2002).

Student pregnancy has gender inequitable effects on access to higher education which are rarely in focus because of the overwhelming large numbers of girls who drop out of school due to teenage pregnancy in lower levels of education. It should be noted that the few numbers of girls who struggle through the challenges of completing lower levels of education are not spared the gender factors and are unfortunately inhibited by other barriers that hinder them from successfully attaining their higher education aspirations (Mieszczanski Citation2018; Mirembe and Davies Citation2001). Further, establishing gender-sensitive and equitable learning environments in higher institutions of learning contributes to national and global commitments to gender equality and the promotion of women’s education (Kwesiga and Ssendiwala Citation2006; UNESCO Citation2019).

While it may be assumed that after lower levels of education, girls will have crossed school completion barriers and this paper provides contrary evidence to these assumptions. We confirm that the older girls in higher institutions of learning were not protected from SGBV during the COVID 19 lockdown that manifested in their high rates of pregnancy while waiting for school to re-open. Worse still, the results of the study confirm other findings which have emphasized the country’s delayed implementation of policies and guidelines coupled with social structures that perpetuate SGBV and increased risky sexual behaviours among young people without appropriate SHR awareness (De Haas and Hutter Citation2019; Kemigisha et al. Citation2019; Moore et al. Citation2022).

The results of this paper indicate that parenting students in higher institutions of learning are discriminated against across different levels of society, at home and in the community where they come from and at college. At the college, discrimination is entrenched in the housing rules and regulations, for example, in most religious founded institutions of higher learning, if a pregnant student cannot prove they are formally married, they are automatically dismissed from the institution, and among public or government founded institutions, girls who become pregnant lose their right to student housing and are required to find private housing. Although Colleges made accommodation available, the housing was considerably substandard.

While most studies on the effects of early pregnancy on access to education tend to focus on younger adolescents, this study provides perspectives for older girls. The unmarried student mothers have to bear the economic and social burdens of childcare and this inhibits them from fully concentrating on their studies. They are thus more likely to perform poorly in school and many drop out. It was mentioned repeatedly that these girls struggle to find food for themselves and their children as well as adequate shelter since they are not allowed in college housing.

In most cultures in Uganda, pregnancy before marriage brings shame to the family of the girl, forced marriages are culturally constructed as a way of protecting the family image and keeping a high value on the value of bride price (Achen et al. Citation2022; Neema et al. Citation2021; Nyakato et al. Citation2021). On the contrary, there are limited societal measures put in place to protect young girls from sexual abuse that may result in outside marriage pregnancies. Girls’ sexuality is controlled using blame, as boys are seemingly free to have sex in proof of their manhood (Ninsiima et al. Citation2018). These and many other cultural norms lack of the ethos to protect women against SGBV.

While abortion is both illegal and morally preconceived (Babigumira et al. Citation2011), the paper agrees with previous studies that revealed that students engage in unsafe because of the fear of lack of child support, need for school continuation and because of pregnancies resulting from SGBV (Cleeve et al. Citation2017) and validation of studies which have reported high rates of abortion among school going girls resulting from lack of agency to negotiate their sexuality amidst competing priority to continue with school (Muhanguzi Citation2011). Similarly, reproductive coercion and unplanned pregnancy have been found to be interconnected, unlike previous studies which associate reproductive coercion from male partners (Grace and Anderson Citation2018), unsafe abortion could be seen as a tradeoff for academic progress.

Lack of sexual health knowledge and skills puts young people at risk of risky sexual behaviour which could explain the high rates of unplanned pregnancies among college students. Uganda still lacks consistency in the implementation of sexuality education in schools. In 2018, the country launched the Sexuality Education Framework which provides policy guidance on sex education in schools. This however is not yet in operation because resistance by a number of stakeholders on grounds of cultural and religious concerns (Kemigisha et al. Citation2019; Ninsiima et al. Citation2020). In consonance with the positive youth development approaches, sexuality education should be comprehensive in a way that does not only focus on sexuality and sexual health but the promotion of positive relational skills as well as collective dimensions of human development (Lerner et al. Citation2011).

Conclusions

The shutdown of schools to prevent the spread of COVID-19 exposed gaps in community support systems for the prevention of SGBV against young people when they are outside the school environment. The vulnerability and lack of resilience among school-going students to sexual violence leading to unplanned and unwanted pregnancies show the prevailing challenge of adhering to traditional gender norms and values. When norms and values do not change with education, it confirms the critique of liberal and western feminist feminists approaches which may not deal with the entrenchment of culture and perpetuation of patriarchal oppression of girls’ sexuality and agency to prevent and protect them against SGBV in and outside the school environment.

Shame and blame, lack of adequate accommodation for students with children, and single parenting are presented as dimensions of abandonment experienced by pregnant and parenting students on return to school to continue with their education after COVID-19. These are examples of the lack of preparedness for inclusiveness and gender equality in education; they are examples of systemic failure to address education needs for pregnancy in the education system. On the other hand, the pregnant students’ persistence to carry on amidst restrictive power and structural system controls could be associated with African Feminism’s perspectives on women and girls’ agency and resilience to overcome cultural and structural oppression. Becoming pregnant as a college student comes with significant burdens of childcare and the associated disruption of learning. Since most of the parenting students were not married, they had the shame and blame for being sexually immoral, they were treated as the other by their colleagues and the college leadership, and lacked family support but still made it to school. Not holding the men and boy’s responsible and accountable for childcare and support to the mothers of their babies is a dimension of gender inequality and injustice in the girls’ education agenda.

Not providing childcare for pregnant and parenting students in higher institutions of learning is discriminatory and perpetuates gender inequality in education. Vulnerability to sexual violence calls for an education system that addresses individual cognitive, emotional and behavioural engagement with family, school and the community aspects of learning and wellbeing. Future studies need to investigate the effects of such tormenting experiences of being abandoned young mother on academic performance and future parenting decisions of such girls.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Viola Nilah Nyakato

Dr. Viola Nilah Nyakato is a sociologist and a community-based participatory research expert. Her specialties are in public health, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, and gender relations. Dr. Viola N Nyakato is a senior lecturer at Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST) and a research associate with Nordic Africa Institute Sweden. She is currently leading studies with a wide range of scientific and policy communication publications in the areas of sexuality education, parent-child communication, gender-based violence in higher institutions of learning, prevention of repeat teen pregnancy, and girls' education after teen pregnancy.

Elizabeth Kemigisha

Dr. Elizaebth Kemigisha is a lecturer at Mbrara University of Science and Technology and a researcher at the African Population and Health Research Centre. Kemigisha is a public health specialist and a pediatricain. She has more than 14 years of research experience. Her research interests cuts across adolescent health issues, including sexuality education, gender attitudes, equity, sexual violence, mental health, HIV/AIDS, menstrual hygiene management, and migrant health. She applies mixed methods methodology in clinical trials, program monitoring and evaluations, and impact evaluations.

Faith Mugabi

Faith Mugabi is a social scientist and a research intern in the Faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies, Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), Uganda

Shakillah Namatovu

Shakillah Namatovu is a social scientist specialized in gender and women's health with five years professional experience in community engagement and development for better project results. Additional experience in project results documenting and dissemination, qualitative and quantitative research and training on public health issues in fragile communities such as refugee settlements, adolescent girls and gender-based violence victims.

Kristien Michielsen

Prof. Dr. Kristien Michielsen is Professor in Promotion of Sexual Wellbeing and Comprehensive Sexuality Education at the Institute of Family and Sexuality Studies, University of K Leuven, Belgium. Her field of expertise is Global Sexual and Reproductive Health, with a specific focus on Sexual and Reproductive Health Behaviour, in particular of adolescents and young people.

Susan Kools

Susan Kools, RN, PhD, FAAN is the Madge M. Jones Emeritus Professor Emeritus at the University of Virginia, Professor Emeritus at the University of California San Francisco, Honorary Professor, Faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies at the Mbarara University of Science and Technology in Uganda, and Fellow in the American Academy of Nursing. Her expertise as a child and adolescent psychiatric nurse scientist has underpinned her 30 years of scholarship with young people who experience vulnerability, marginalization and health inequities.

References

- Achen, Dorcus, Viola N Nyakato, Cecilia Akatukwasa, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Wendo Mlahagwa, Ruth Kaziga, Gad Ndaruhutse Ruzaaza, Godfrey Z Rukundo, Kristien Michielsen, and Stella Neema. 2022. “Gendered Experiences of Parent–Child Communication on Sexual and Reproductive Health Issues: A Qualitative Study Employing Community-Based Participatory Methods among Primary Caregivers and Community Stakeholders in Rural South-Western Uganda.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (9): 5052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095052.

- Agardh, Anette, Karen Odberg-Pettersson, and Per-Olof Östergren. 2011. “Experience of Sexual Coercion and Risky Sexual Behavior Among Ugandan University Students.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-1

- Ahikire, Josephine. 2014. “African Feminism in Context: Reflections on the Legitimation Battles, Victories and Reversals.” Feminist Africa 19 (7): 7–23.

- Angrist, Noam, Andreas de Barros, Radhika Bhula, Shiraz Chakera, Chris Cummiskey, Joseph DeStefano, John Floretta, Michelle Kaffenberger, Benjamin Piper, and Jonathan Stern. 2021. “Building Back Better to Avert a Learning Catastrophe: Estimating Learning Loss from COVID-19 School Shutdowns in Africa and Facilitating Short-Term and Long-Term Learning Recovery.” International Journal of Educational Development 84: 102397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102397

- Azubuike, Obiageri Bridget, Oyindamola Adegboye, and Habeeb Quadri. 2021. “Who Gets to Learn in a Pandemic? Exploring the Digital Divide in Remote Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria.” International Journal of Educational Research Open 2: 100022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100022

- Babigumira, Joseph B, Andy Stergachis, David L Veenstra, Jacqueline S Gardner, Joseph Ngonzi, Peter Mukasa-Kivunike, and Louis P Garrison. 2011. “Estimating the Costs of Induced Abortion in Uganda: A Model-Based Analysis.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-1

- Badri, Amira Y. 2014. “School-Gender-Based Violence in Africa: Prevalence and Consequences.” Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences 2 (2): 1–20.

- Benson, Peter L., Peter C. Scales, Stephen F. Hamilton, and Arturo Sesma Jr. 2006. “Positive Youth Development: Theory, Research, and Applications.”

- Bhana, Deevia, Lindsay Clowes, Robert Morrell, and Tamara Shefer. 2008. “Pregnant Girls and Young Parents in South African Schools.” Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 22 (76): 78–90.

- Bhana, Deevia, Shakila Singh, and Thabo Msibi. 2021. “Introduction: Gender, Sexuality, and Violence in Education—A Three-Ply Yarn Approach.” In Gender, Sexuality and Violence in South African Educational Spaces, edited by Deevia Bhana, Shakila Singh, and Thabo Msibi, 1–46. Springer.

- Birungi, Harriet, Chi-Chi Undie, Ian MacKenzie, Anne Katahoire, Francis Obare, and Patricia Machawira. 2015. “Education Sector Response to Early and Unintended Pregnancy: A Review of Country Experiences in Sub-Saharan Africa.”.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burgess, Simon, and Hans Henrik Sievertsen. 2020. “Schools, Skills, and Learning: The Impact of COVID-19 on Education.” VoxEu. org 1 (2): 73–89.

- Candia, Douglas Andabati, Claire Ashaba, James Mukoki, Peter Jegrace Jehopio, and Brenda Kyasiimire. 2018. “Non-school Factors Associated with School Drop-Outs in Uganda.” Sciences 4 (1): 477–493.

- Chigona, Agnes, and Rajendra Chetty. 2007. “Girls’ Education in South Africa: Special Consideration to Teen Mothers as Learners.” Journal of Education for International Development 3 (1): 1–17.

- Chilisa, Bagele. 2002. “National Policies on Pregnancy in Education Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Botswana.” Gender and Education 14 (1): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250120098852

- Chilisa, Bagele, and Gabo Ntseane. 2010. “Resisting Dominant Discourses: Implications of Indigenous, African Feminist Theory and Methods for Gender and Education Research.” Gender and Education 22 (6): 617–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2010.519578

- Cleeve, Amanda, Elisabeth Faxelid, Gorette Nalwadda, and Marie Klingberg-Allvin. 2017. “Abortion as Agentive Action: Reproductive Agency Among Young Women Seeking Post-Abortion Care in Uganda.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19 (11): 1286–1300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1310297

- David, Miriam E. 2017. “Femifesta? Reflections on Writing a Feminist Memoir and a Feminist Manifesto.” Gender and Education 29 (4): 525–535.

- de Bruin, Yuri Bruinen, Anne-Sophie Lequarre, Josephine McCourt, Peter Clevestig, Filippo Pigazzani, Maryam Zare Jeddi, Claudio Colosio, and Margarida Goulart. 2020. “Initial Impacts of Global Risk Mitigation Measures Taken During the Combatting of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Safety Science 128: 104773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104773

- De Haas, Billie, and Inge Hutter. 2019. “Teachers’ Conflicting Cultural Schemas of Teaching Comprehensive School-Based Sexuality Education in Kampala, Uganda.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 21 (2): 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1463455

- Devries, Karen M, Jennifer C Child, Elizabeth Allen, Eddy Walakira, Jenny Parkes, and Dipak Naker. 2014. “School Violence, Mental Health, and Educational Performance in Uganda.” Pediatrics 133 (1): e129–e137. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2007

- Eastwood, Robert, and Michael Lipton. 2011. “Demographic Transition in sub-Saharan Africa: How Big Will the Economic Dividend Be?” Population Studies 65 (1): 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2010.547946.

- Fennell, Shailaja, and Madeleine Arnot. 2008. “Decentring Hegemonic Gender Theory: The Implications for Educational Research.” Compare 38 (5): 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920802351283

- Grace, Karen Trister, and Jocelyn C Anderson. 2018. “Reproductive Coercion: A Systematic Review.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 19 (4): 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016663935

- Gunawardena, Nathali, Arone Wondwossen Fantaye, and Sanni Yaya. 2019. “Predictors of Pregnancy Among Young People in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis.” BMJ Global Health 4 (3): e001499.

- Iddy, Hassan. 2021. “Girls’ Right to Education in Tanzania: Incongruities Between Legislation and Practice.” Gender Issues 38 (3): 324–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-021-09273-8.

- Kemigisha, Elizabeth, Katharine Bruce, Olena Ivanova, Els Leye, Gily Coene, Gad N Ruzaaza, Anna B Ninsiima, Wendo Mlahagwa, Viola N Nyakato, and Kristien Michielsen. 2019. “‘We Have to Clean Ourselves to Ensure That Our Children Are Healthy and Beautiful’: Findings From a Qualitative Assessment of a Hand Hygiene Poster in Rural Uganda.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6343-3.

- Kemigisha, Elizabeth, Olena Ivanova, Gad N Ruzaaza, Anna B Ninsiima, Ruth Kaziga, Katharine Bruce, Els Leye, Gily Coene, Viola N Nyakato, and Kristien Michielsen. 2019. “Process Evaluation of a Comprehensive Sexuality Education Intervention in Primary Schools in South Western Uganda.” Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 21: 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2019.06.006

- Kwesiga, Joy C, and Elizabeth N Ssendiwala. 2006. “Gender Mainstreaming in The University Context: Prospects and Challenges at Makerere University, Uganda.” Paper Read at Women’s Studies International Forum.

- Lerner, Richard M, Jacqueline V Lerner, Selva Lewin-Bizan, Edmond P Bowers, Michelle J Boyd, Megan Kiely Mueller, Kristina L Schmid, and Christopher M Napolitano. 2011. “Positive Youth Development: Processes, Programs, and Problematics.” Journal of Youth Development 6 (3): 38–62. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2011.174

- Lundgren, Rebecka, and Avni Amin. 2015. “Addressing Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Among Adolescents: Emerging Evidence of Effectiveness.” Journal of Adolescent Health 56 (1): S42–S50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.012.

- MacDonald, Madeleine. 2012. “Schooling and the Reproduction of Class and Gender Relations.” In Schooling, Ideology and the Curriculum (RLE Edu L), edited by Len Barton, Roland Meighan, and Stephen Walker, 29–49. New York: Routledge.

- Mieszczanski, Elena. 2018. “Schooling Silence: Sexual Harassment and Its Presence and Perception at Uganda’s Universities and Secondary Schools.”

- Mirembe, Robina, and Lynn Davies. 2001. “Is Schooling a Risk? Gender, Power Relations, and School Culture in Uganda.” Gender and Education 13 (4): 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250120081751

- Monk, David, Maria del Guadalupe Davidson, and John C. Harris. 2021. “Gender and Education in Uganda.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. England.

- Moore, Erin V, Jennifer S Hirsch, Esther Spindler, Fred Nalugoda, and John S Santelli. 2022. “Debating Sex and Sovereignty: Uganda’s New National Sexuality Education Policy.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 19 (2): 678–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00584-9

- Mubatsi, Asinja Habati. 2022. Uganda: New Pregnancy Policy Bears Twin Problems. The Indipendent. Kampala Available at https://www.independent.co.ug/new-pregnancy-policy-bears-twin-problems/.

- Muhanguzi, Florence Kyoheirwe. 2011. “Gender and Sexual Vulnerability of Young Women in Africa: Experiences of Young Girls in Secondary Schools in Uganda.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 13 (6): 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.571290

- Mwangi, Monicah. 2021. Africa: Rights Progress for Pregnant Students: Five More Sub-Saharan Countries Act to Protect Girls’. Education; Barriers Remain. Human Rights Watch. Available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/09/29/africa-rights-progress-pregnant-students

- Nabugoomu, Josephine. 2019. “School Dropout in Rural Uganda: Stakeholder Perceptions on Contributing Factors and Solutions.” Education Journal 8 (5): 185. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.edu.20190805.13

- Neema, Stella, Christine Muhumuza, Rita Nakigudde, Cecilie S Uldbjerg, Florence M Tagoola, and Edson Muhwezi. 2021. “‘Trading Daughters for Livestock’: An Ethnographic Study of Facilitators of Child Marriage in Lira District, Northern Uganda.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 25 (3): 83–93.

- Ninsiima, Anna B, Gily Coene, Kristien Michielsen, Solome Najjuka, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Gad Ndaruhutse Ruzaaza, Viola N Nyakato, and Els Leye. 2020. “Institutional and Contextual Obstacles to Sexuality Education Policy Implementation in Uganda.” Sex Education 20 (1): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1609437.

- Ninsiima, Anna B, Els Leye, Kristien Michielsen, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Viola N Nyakato, and Gily Coene. 2018. “‘Girls Have More Challenges; They Need to Be Locked Up’: A Qualitative Study of Gender Norms and the Sexuality of Young Adolescents in Uganda.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (2): 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020193

- Nyakato, Viola N, Charlotte Achen, Destinie Chambers, Ruth Kaziga, Zina Ogunnaya, Maya Wright, and Susan Kools. 2021. “Very Young Adolescent Perceptions of Growing Up in Rural Southwest Uganda: Influences on Sexual Development and Behavior.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 25 (2): 50–64.

- Nyariro, Milka. 2021. “‘We Have Heard You But We Are Not Changing Anything’: Policymakers as Audience to a Photovoice Exhibition on Challenges to School Re-entry for Young Mothers in Kenya.” Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 35 (1): 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2020.1855850.

- Okwany, Auma. 2016. “Gendered Norms and Girls’ Education in Kenya and Uganda: A Social Norms Perspective.” In Changing Social Norms to Universalize Girls’ Education in East Africa: Lessons from a Pilot Project, 12–29. Leiden: Maklu.

- Parkes, Jenny, Jo Heslop, Freya Johnson Ross, Rosie Westerveld, and Elaine Unterhalter. 2016. “A Rigorous Review of Global Research Evidence on Policy and Practice on School-Related Gender-Based Violence.” New York: UNICEF.

- Romeo, Katherine E, and Michele A Kelley. 2009. “Incorporating Human Sexuality Content Into a Positive Youth Development Framework: Implications for Community Prevention.” Children and Youth Services Review 31 (9): 1001–1009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.015

- Salvi, Francesca. 2018. “In the Making: Constructing In-School Pregnancy in Mozambique.” Gender and Education 30 (4): 494–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1219700.

- Salvi, Francesca. 2019. Teenage Pregnancy and Education in the Global South: The Case of Mozambique. London: Routledge.

- Tiedeu, Barbara Atogho, Oluwafunmilayo Josephine Para-Mallam, and Dorothy Nyambi. 2019. “Driving Gender Equity in African Scientific Institutions.” The Lancet 393 (10171): 504–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30284-3

- Undie, Chi-Chi, Harriet Birungi, George Odwe, and Francis Obare. 2015. “Expanding Access to Secondary School Education for Teenage Mothers in Kenya: A Baseline Study Report.”

- UNESCO. 2019. “From Access to Empowerment: UNESCO Strategy for Gender Equality in and Through Education 2019-2025.” In: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000369000.

- UNESCO. 2020a. 2020 Global Education Meeting Extraordinary Session on Education Post-COVID-19 Background Document. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2020b. “Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All.” 92310038.

- UNHCR. 2021. “UNHCR Policy on the Prevention of, Risk Mitigation, and Response to Gender-Based Violence (GBV).” In International Journal of Refugee Law, edited by UNHCR Division of International Protection. Geneva: UNHCR.

- UNICEF. 2015. “Ending Child Marriage and Teenage Pregnancy in Uganda: Formative Research to Guide the Implementation of the National Strategy on Ending Child Marriage and Teenage Pregnancy in Uganda.” Kampala: Unicef and Government of Uganda.

- UNICEF. 2022. “COVID:19 Scale of Education Loss ‘Nearly Insurmountable’, Warns UNICEF.” Unicef 2022 [cited May 2022 2022].

- WHO. 2020. “The Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).”

- Yakubu, Ibrahim, and Waliu Jawula Salisu. 2018. “Determinants of Adolescent Pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review.” Reproductive Health 15 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0439-6