ABSTRACT

Public policy is increasingly implemented through projects and project managers are often hired on temporary contracts to manage the implementation. There is scant research on how temporary employment affects public governance. This article explores how the employment of managers with part-time and limited duration contracts affects public innovation.

IMPACT

This study provides empirical evidence of the effects of employing public sector project managers on a temporary basis. Hiring managers on part-time contracts reduces the innovative potential of experimenting with new ways of working. Public sector agencies need to carefully weigh the negative effects of temporary appointments on innovation and balance best practice against cost-savings when hiring managers for public sector projects.

Introduction

Partnerships and collaborations are increasingly used by governments to solve difficult problems without putting additional pressures on public finances (Donahue & Zeckhauser, Citation2011). Time-limited projects with a specific task allow knowledge, money, public authority, and other crucial resources to be combined for specific interventions (Brulin & Svensson, Citation2012; Sjöblom et al., Citation2013). Regional development in the European Union (EU) (Bache, Citation2010) and local environment protection in the USA (Munck af Rosenschöld & Wolf, Citation2017) are good examples of areas in which these projects are used. These projects are part of the general shift in Western liberal democracies from top-down government to bottom-up governance (Hodgson et al., Citation2019; Jacobsson et al., Citation2015). However, although they enable learning and innovation (Grabher, Citation2004a; Jensen et al., Citation2013), the time-limited nature of these projects poses governance problems in terms of accountability (Büttner, Citation2019) and sustainable results (Godenhjelm et al., Citation2019). Despite the extensive research conducted on public project management and governance, little has been published on the fact that partnerships and collaborations employ project managers on a temporary basis (Lundin et al., Citation2015), and the effect that this practice has on public policy implementation and governance (Bache, Citation2010; Le Galés, Citation2011; Sjöblom et al., Citation2013). This article provides an analysis of the temporary employment of project managers and its impact on project outcomes. The research question behind this article was:

What are the effects on innovation of the temporary employment of project managers?

The article answers this question by testing the mechanisms of uncertainty resulting from temporary employment that either impede or incentivize innovation, based on the theory of the temporary organization (Lundin et al., Citation2015; Lundin & Söderholm, Citation1995). The theoretically-derived assumptions were tested on the EU’s Cohesion Policy programme in Finland with official data on the projects from the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and survey data from the project managers. The main analysis with logistic regression estimates the probability of innovations, given certain employment and management factors in projects, as well as their interaction. The Cohesion Policy was treated as a proxy for the increasingly common use of flexible and time-limited organizational forms in the public sector. By studying the effects of the conditions under which project management is performed, this article increases our understanding of how these new organizational forms affect public governance, with public managers playing new roles in agencies (Lynn, Citation1981; Pollitt, Citation2003) and, more recently, as network managers (O’Toole & Meier, Citation2010).

Public governance research and ‘projectification’

The governing of Western welfare states has undergone fundamental changes in the past three decades—largely because of administrative reforms aimed at creating a more effective public sector and harnessing the transformative powers of the private and third sectors (Du Gay, Citation2000; Hood, Citation1991; Osborne & Gaebler, Citation1992). At the macro level, these changes have been conceptualized as the new public governance (NPG), entailing social control based on multi-level mechanisms with various agents and organizational forms (Osborne, Citation2010). The move from top-down administered public policies and services to policy implementation and service delivery in public–private partnerships and collaborative arrangements has required new governance tools to manage the complex web of interdependencies between public and non-public agents (Osborne & Brown, Citation2013). Among the new flexible forms of organization, temporary organizations present specific challenges to public governance (Hodgson et al., Citation2019; Sjöblom et al., Citation2013). Although there is no shortage of research on project management in the public sector, for example on such technological projects as the Manhattan project and Apollo project (Lundin & Söderholm, Citation1995; Sahlin-Andersson & Söderholm, Citation2002) and, more recently, in the contexts of environment protection and natural resource management (Engwall, Citation2003; Munck af Rosenschöld & Wolf, Citation2017) and urban, rural and metropolitan governance (Grabher, Citation2004b; Marsden et al., Citation2012), insufficient attention has been paid to the effects of employing temporary project managers.

With the distinctive organizational character of being a temporary endeavour, a project offers efficiency and innovation (Grabher, Citation2002). After a long history in science and construction and then in entertainment and business (Bakker, Citation2010), projects started to appear regularly in the public sector in the late 1980s in the wake of new public management reforms and the spread of managerialism (Sjöblom et al., Citation2013). The rise of the public innovation paradigm in the 2000s and 2010s further strengthened the position of the project as the standard organizational solution for ‘wicked’ problems (Gripenberg et al., Citation2012). Indeed, sociologists started to talk about the ‘project society’ in the early 2010s (Jensen, Citation2012). The importance of the project as a governance tool in public innovation policy and governance (Jacobsson et al., Citation2015; Sjöblom & Godenhjelm, Citation2009) is why the question raised in this article is so important. The project organization perspective, and more specifically its temporary dimension, may illustrate new aspects of public innovation, complementing previous studies that focused explicitly on public innovation as a concept (Walker, Citation2006), its sources (Walker, Citation2008), and its drivers (Damanpour et al., Citation2009) and effects (Walker et al., Citation2011).

Public innovation in theory and the EU’s regional policy

‘Innovation’ has become a buzzword in the public sector, signifying progress, development and performance (Osborne & Brown, Citation2013). Most Western democracies have an explicit policy on innovation that is designed to support R&D activities in enterprises and experimenting and learning in universities (Anttiroiko et al., Citation2011). Innovation is also implicitly ingrained in public policies that present reform and development as a way to solve complex problems, such as environmental policy aimed at managing environmental hazards or social policies that manage socio-economic segregation (Brulin & Svensson, Citation2012; Munck af Rosenschöld & Wolf, Citation2017).

Traditionally, an innovation refers to a technical invention in the form of a new or improved product or formula (Rowley et al., Citation2011; Walker, Citation2006). In the context of public governance, innovation or renewal has also been regarded as change in institutions or systems (Bevir & Bowman, Citation2011). Walker (Citation2006) offers a systematization of various public innovation concepts. More recently, the term ‘social innovation’ has been used for initiatives aimed at changing faults in society, such as growing socioeconomic segregation (Clegg et al., Citation2011). This kind of innovation is often initiated by or developed from minor changes in processes or institutions at the local level of the governance system (Anttiroiko et al., Citation2011).

As a general concept, innovation comprises the creation of something new that requires development and reform (Vento, Citation2020). However, what is new in one community might be old in another and the benefits of a product or process might be realized long after the initial invention (Torfing & Triantafillou, Citation2016). Further, to make use of new knowledge and make sure that use is sustainable and potentially generalizable to other organizations, new processes need to be tested and conceptualized in the organization (Skelcher & Sullivan, Citation2008). Process innovations that have been shown to work, and that have been consciously conceptualized with the idea of disseminating them to other organizations, are often referred to as ‘best practices’ by innovation practitioners (Hartley, Citation2016). Therefore, public innovation is embedded in the structures and processes of public governance (Anttiroiko et al., Citation2011).

Research has also suggested that public innovations form complex webs of interdependencies (Walker, Citation2006), but empirical research has shown them to be less complementary than theorized (Walker, Citation2008). Bold innovations that diverge significantly from the norm have been found to be the most likely to be successful, as opposed to incremental innovations (Damanpour et al., Citation2009), but the drivers of diffusion vary by the type of innovation (Walker et al., Citation2011).

This article looks at process innovations—novel processes or solutions conceptualized to be transferable to other organizations, i.e. best practice. Public sector process innovation includes management, organizational and technological innovations (Walker, Citation2006). Considering the various conceptions of innovation, this definition is by no means exhaustive and it excludes both traditional innovations such as tangible products and patents, as well as more elusive innovations, such as learning, knowledge and grand systemic changes. The strength of the best practice concept is that it captures the essence of public innovation by constituting a renewed or entirely new process put into good use that increases public value.

Temporary employment of project managers

Lundin and Söderholm (Citation1995) proposed ‘a theory of the temporary organization’ to include the kinds of projects discussed in this article. Their theoretical framework is very much a patchwork of different assumptions from different fields of knowledge (see, for example, Bakker, Citation2010; Godenhjelm et al., Citation2015; Grabher, Citation2002; Lundin & Söderholm, Citation1995; Raab et al., Citation2009; Sahlin-Andersson & Söderholm, Citation2002). Some central elements in organizing projects continue to be open-ended questions. The effect of working in a temporary organization is a key aspect of project organization, particularly in terms of incentivizing and managing project managers (Lundin et al., Citation2015). Researchers have found that ‘temporariness’ both enhances and restricts project managers’ performance. This, in turn, is crucial to project performance and innovation (Lundin et al., Citation2015).

Theoretical work has also largely been focused on the private sector (see, for example, Meredith & Mantel, Citation2018). However, projects in the public sector are distinct from private sector or third sector projects because attempting to deliver public value can make them more complex (Sjöblom & Godenhjelm, Citation2009). Public sector projects are also often embedded within public institutions, in terms of funding, supervision and objectives, decreasing the freedom that managers have in comparison to private or third sector projects. In addition, public sector projects, which are either organized to implement policy or renew intra-organizational activities (Jensen et al., Citation2006), are generally less driven by a novel idea and more by how much public funding is available (Fred, Citation2018). As well, public sector project managers often just move on to a sequel project which is only marginally different from the previous project once the earlier one has been completed (Büttner, Citation2019). This so-called ‘projectification’ of the public sector has given rise to a class of project managers whose career moves from project to project (Kovách & Kučerova, Citation2009). Project-based policy implementation in ‘temporary’ organizations has made project management a key part of public governance (Fred, Citation2018).

In public governance research to date, temporariness has been addressed by analysing the boundary between the project team and the permanent organization (Godenhjelm et al., Citation2015; Sjöblom et al., Citation2013). The effects of the temporary organization on the implementation of public policy have largely been ignored. By focusing on the form of employment of the project manager—the most important person in the public project—the effects of its temporary nature can be better understood. (Godenhjelm et al., Citation2015).

Project management is always temporary, with a predefined organizational lifetime, so project managers work under contract (Lundin et al., Citation2015). These managers may therefore be concerned about obtaining future work, increasing the significance of their employment outlook in comparison to employment in permanent organizations. This can sometimes mean that public sector project managers work part time on a project while performing other roles or working on other projects. Sometimes projects are more intensive and require full-time managers.

Direct effect: uncertainty and innovation

Temporary employment will affect performance through mechanisms of uncertainty (Lundin et al., Citation2015) that either impede or incentivize a manager (Andersen, Citation2016; Godenhjelm & Johanson, Citation2018). The uncertainty that arises from being hired for a temporary project may mean that a manager will focus on finding a new job before the end of the project. One risk in this is the manager could become a ‘lame duck’ (suffering from reduced trust among co-workers and lack of interest in the goals of the project) with negative consequences for innovation (Meyerson et al., Citation1996).

Uncertainty can also arise from having a part-time manager, potentially limiting the socialization of the project team into a functional group (Meyerson et al., Citation1996; Saunders & Ahuja, Citation2006), or distracting the manager from the project’s goals (Lundin et al., Citation2015). Public sector projects often require high competence and the full attention of the manager, which part-time employment risks undermining (Lundin et al., Citation2015).

On the other hand, the uncertainty of finding work can give the manager the incentive to push for better results and add resources to the project, in the hope that their performance and results might lead to a new project or employment in another organization (Sjöblom & Godenhjelm, Citation2009; Raab et al., Citation2009). Similarly, part-time work, if the manager also works part time in another organization, can bring in new influences, networks, ideas or knowledge (Bakker, Citation2010). However, evidence for this comes from the private sector (Lynn, Citation2006) and therefore this effect is not considered in this article.

Indirect effect: the benefit of flexibility

Apart from temporariness, managerial flexibility is often considered to be a major benefit of projects (Sahlin-Andersson & Söderholm, Citation2002). The extensive literature on managing public sector innovation considers innovation to flow from mixing ideas and influences, thinking ‘outside the box’, and experimenting with different ways of doing things (Clegg et al., Citation2011). These qualities can be encouraged by managing the organization flexibly, such as by allowing meaningful collaboration, and pushing for new ways of doing things, instead of falling back on old habits (Sørensen, Citation2012). The theory of the temporary organization considers this in terms of managerial autonomy, which is established by decoupling from institutions and routines (Godenhjelm et al., Citation2015; Lundin & Söderholm, Citation1995). Autonomy gives the project manager an opportunity to try new methods without fear of failure. Flexibility can also be spatial, such that, instead of being tied to a particular place, activities are performed in the best space for problem-solving; in project work, this can mean telecommuting.

However, flexible management does not reduce bureaucracy (Du Gay, Citation2000); instead, there may be even more forms, schedules and other controls (Hodgson, Citation2004). Bureaucracy in projects may even be a precondition for innovation, by providing certainty and stability as a counterweight to experimenting and learning. This is the case particularly when the project manager is supported by other administrative personnel in the project. According to specialization theory, a temporary project manager can focus on leading the work on innovation instead of being burdened by bureaucracy (Clegg et al., Citation2011).

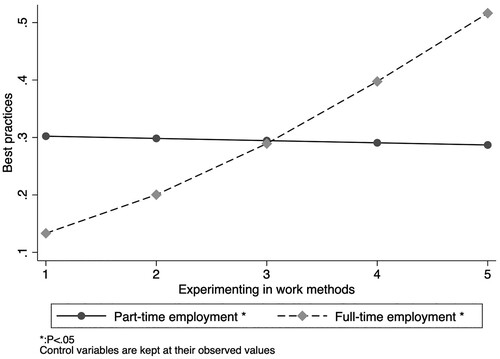

In contrast to temporariness, the forms and effects of flexible management have been scrutinized both in projects and in other new organizations (Ika, Citation2009; Too & Weaver, Citation2014). The present research recognized the importance of flexible management in explaining innovation. The management aspects are treated in the analysis as covariates, but their direct effects on innovation are not analysed with specific research hypotheses. However, how much temporary employment conditions the effect of management flexibility on innovation has not been considered before. In other words, can project managers on part-time and full-time contracts both harness the innovative potential of experimenting with new work methods?

Research hypotheses

The following effects of the temporary employment of project managers on public innovation were investigated:

H1: Part-time employment of a project manager reduces innovation in public sector projects.

H2: The manager’s uncertainty about their employment after the completion of the project reduces innovation in public sector projects.

H3: Part-time employment of a project manager limits the benefits of experimenting in public projects with regard to creating innovation

H1 and H2 concern direct effects of temporary employment on innovation, whereas H3 concerns a conditional effect of temporary employment on innovation.

Context

The case study was the EU’s European Regional Development Fund programme (ERDF) in Finland between 2007 and 2013. Public innovation is fundamental to realizing the EU’s future strategies of smart and sustainable growth in the EU under the EU Cohesion Policy and the ERDF programme (Piattoni & Polverari, Citation2016).

Accounting for one-third of the total EU budget (a total of €347 billion in 2007–2013, €352 in 2014–2020 and €392 in 2021–2027), the Cohesion Policy has been one of the more significant transformative public policies in the EU (Brulin & Svensson, Citation2012). Implemented according to the Open Method of Coordination (OMC), the Cohesion Policy sets common goals for member states, which are then adjusted to local needs (Nugent, Citation2017).

Although implementation of the Cohesion Policy is governed by the national administrations to suit local conditions, implementation is meant to be standardized. Local non-state agents apply for funding from the regional administration for development projects and must meet a range of criteria of good governance by appointing a project manager (Brulin & Svensson, Citation2012). As a well-governed Nordic welfare state (Virtanen, Citation2016), Finland is a ‘best case’ context for the administration of complex interdependencies in project-based policy implementation. By focusing on the micro-level organization of the projects—which are similar in all Cohesion Policy projects—this article sheds light on common mechanisms that do not vary across national programmes.

Data, method and operationalization

During the ERDF programme period, some 18,000 EU projects were implemented in Finland. The data presented here are follow-up data on the projects, gathered by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, together with an independent research survey of project managers. The projects were classified according to their objectives. Most projects provided financial support to companies. Some 2200 projects were development or innovation projects in the sense of having a project organization with a manager and the goal of economic or social development (Godenhjelm & Johanson, Citation2018). Approximately half of these projects were ERDF projects and the rest were projects from other EU funds. Of the ERDF development projects in Finland, 728 had ended by 2012. The project managers of these projects were surveyed in summer 2013 with an electronic survey (response rate 49%). The programme logic ensures a certain degree of cross-project coherence, which is necessary for an extensive study based on register and survey data. Moreover, the focus on organizational form and management in this study transcends the policy goals, which change with each policy programme period, making the findings relevant in more recent and also future Cohesion Policy programmes.

Dependent variable: public innovation

Public innovation was the dependent variable in the analysis and was coded using quantitative content analysis of the official project reports, originally written by the project manager for the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. The creation of an improved process that could be adopted by other organizations or sectors for improved social service delivery was counted as an innovation, or best practice. The projects received a score of 0/1 depending on whether or not they created a best practice ().

Table 1. Variable and independent variables analysed.

Independent variables and covariates

The survey of project managers asked whether their employment was part time or full time; this was the primary independent variable. The secondary independent variable—employment outlook—was operationalized with the statement ‘Most of those employed in the project had work after the end of the project’. Answers were on a Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree).

Managerial flexibility, as experimenting with new methods of working, was operationalized with the answers to the survey statement ‘We often experimented with new ways of doing things and working methods’ and the answer on a Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree). Flexibility in terms of being able to telecommute was established with simple ‘yes’/‘no’ answers.

Lastly, management flexibility, defined as separation of project management and administration, was operationalized with the question ‘Did the project employ administrative personnel other than the project manager?’ with the answers: ‘yes, part time’; ‘yes, full time’ and ‘no other administrative personnel’. The variable was coded as binary with 0 for no other administrative personnel than the project manager and 1 for part- or full-time administrative personnel other than the project manager. The variables representing different aspects of management flexibility were included in the analysis as covariates: their effect was analysed but the primary interest lay in explaining the effect of the independent variables.

In addition, the project budget (obtained from the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment’s register on EU Cohesion Policy projects in Finland) and the project manager’s years of experience (a categorical variable categorized as 0–2 years, 3–5 years, and 6 years or more and obtained from the survey of project managers) were controlled for to estimate the effect on innovation of management and employment of the project manager in relation to that of organizational size and the project manager’s characteristics.

Method

The analysis began with a short exploration of the descriptive statistics on the variables to give a general view of the distribution of the various ways in which project managers were employed on public projects. The effects of the factors and their interaction on innovation, which were operationalized as a binary variable, were estimated with logistic regression models and illustrated with Stata 15. The interaction effect (the effect of the primary independent variable on the dependent variable, taking the moderating variable into account) was further analysed at different levels of the primary and moderating variables with adjusted means. The adjusted means were estimated with the post-estimation test ‘margins’, producing the mean predictive values of the primary independent variable on the dependent variable given certain values of the moderating variable, while holding the control variables at their observed values.

Analysis

Around one-third of the projects examined were successful in generating best practice (see ), and could therefore be considered innovative. also shows that there was considerable variation in the temporary employment of managers in public projects. A small majority of the managers were hired to work part time and, surprisingly, most of the personnel found work after the project was completed.

There was also an interesting variation in the flexible management of the projects. Most projects allowed telecommuting (see ). However, the extent of experimenting with new methods of working was evenly distributed. A clear majority of the projects also had a person hired to administer the project.

The managers of public projects, on average, were experienced; years of experience were categorized as low (0–2 years), medium (3–5 years) and high (6+ years). The average budget of the projects was €340,000.

Regression of the probability of innovation with regard to the form of employment of the project manager and management factors in Model 1 (see ) did not find a significant relationship between the project manager’s employment status, whether part time or full time, and best practice. Neither was the project manager’s employment outlook after the project ended significantly related to being innovative. However, experimenting with new methods of working slightly increased the chance of innovation (1.237, p < .05), and the presence of administrative personnel in addition to the project manager increased the chances of innovation (2.115, p < .05).

Table 2. The effects of the temporary employment of managers in public projects on public innovation by logistic regression modeling, including management flexibility and organizational factors as covariates (part-time employment was the baseline).

However, controlling for the budget and the project manager’s experience in Model 2 changed the statistical significance of the factors in Model 1 (see ). An increase in budget added to the likelihood of innovation on average, while the managerial flexibility factors that were found to have an impact in Model 1 became insignificant. The explanatory power of Model 1 is therefore questionable.

Model 3 (where part-time employment was the baseline) found that the interaction between the employment status of project the manager and experimenting increased innovation (see ). Of the other employment and management flexibility factors, only the presence of administrative personnel in addition to the project manager was significantly related to innovation. The strength of the relationship between the interaction term and innovation did not change when control variables were added in Model 4 (). The direct effect of administrative personnel on innovation, however, disappears once again. The effect of the interaction between the employment status of the project manager and experimenting was therefore robust.

Table 3. Predictive margins of estimated effect of experimenting on best practices moderated by part-time or full-time employment of a project manager (Wald test values reported z and the two-tailed p value used in testing the null hypothesis).

The post-estimation with predictive margins shows the effect on innovation of experimenting with new methods of working, and also the effect of the project manager’s employment status (whether part time or full time). The adjusted means were statistically significant (p < .05) on all estimated levels ().

The effect is illustrated in with the predictive margins of experimenting on best practices with the project manager hired part time or full time, and holding the control variables at their observed values. The estimation shows that projects with a full-time manager and low experimenting were less likely to generate best practices compared to projects with a part-time manager and low experimenting. Projects with a high level of experimenting with new methods of working and a full-time manager had more than double the chance of creating best practices in comparison with projects that had a full-time manager but low levels of experimenting. Interestingly, projects with a project manager hired on a part-time basis that experimented to a high degree with new methods of working were no more likely to create best practices than projects with a part-time manager and a low level of experimentation.

Discussion

There is considerable variation in the employment of managers for public sector projects, in terms of tasks and whether managers work full time or part time on a project. Looking at these variations in the public projects funded by the EU Cohesion Policy programme in Finland, and their effect on generating innovation and best practice, at the micro-level of public policy implementation, adds to our understanding of organizational forms in the public sector (Donahue & Zeckhauser, Citation2011).

The fact that only a third of the projects examined produced a best practice means that there are interesting mechanisms which impact innovations in public sector projects. Hiring a full-time project manager was found not to be directly more beneficial for innovation than hiring a part-time manager, so H1 was not proved. Similarly, there was no evidence that a project manager’s concerns about post-project employment would limit innovation, so H2 was not proved.

The strong direct effect found between the presence of non-managerial administrative personnel and innovation suggested support for specialization theory which, in the case of public administration, implies that having administrative assistance to take care of the bureaucracy enhances a project manager’s capacity to manage the development work (Hodgson, Citation2004). However, the reduction of this effect when controlling for budget suggests that larger projects are more innovative and have a project administration staff due to their size. It was similarly interesting that management flexibility did not impact the probability of innovation (Clegg et al., Citation2011).

Interaction analysis showed that the temporary employment of manager affects innovation indirectly in terms of experimenting for creating best practices. H3 was therefore confirmed. Based on the theory of public projects and innovation management, it is possible that a full-time project manager is more capable of, or interested in, identifying and conceptualizing successful new processes that would be beneficial to other organizations (Clegg et al., Citation2011; Lundin et al., Citation2015). The theory of temporary organizations should take note of this finding, as should the literature on public innovation governance which so far has not considered how the temporariness of managers hired on contract affects innovation.

The study did not reveal the reason for more than half of the projects having a part-time project manager, but an educated guess would be that the ongoing pressure of cost control in the public sector results in hiring part-time project managers to reduce expenditure (Jacobsen & Thrane, Citation2016). This is being done at the cost of innovation.

Concluding remarks

There has been a surge in new organizational forms in public policy implementation and service delivery aimed at collaboration with other organizations and creating new innovations (Osborne, Citation2010). In this micro-level development of public governance, temporary organizations in the form of projects have proliferated (Marsden et al., Citation2012). Despite the widespread use of projects, their effects on public innovation have rarely been studied. Public innovation research, project management and public governance research has largely ignored the effects of the temporary nature of projects. Publications to date have interpreted the uncertainty arising from the temporary employment of managers as either an incentive for innovation or an obstacle to it.

With evidence from a large empirical data set, this article has shown that there is considerable variation in terms of employing managers and the degree of managerial freedom in EU-funded projects in Finland. Most project managers were employed part time but considered their employment outlook when the project ended to be satisfactory. The projects also allowed several forms of managerial flexibility. Only a third of the projects created a process innovation, or a best practice.

Despite this variation in the organization and management of the projects, only the hiring of administrative personnel other than the project manager had a direct effect on innovation, in favour of projects with a separate administration. However, this effect can be explained by project size, because larger projects that hire administrative personnel are also more innovative. The employment status of the project manager was indirectly important for innovation. Flexible management made a difference in terms of innovation only when the project manager worked full time. Projects with a part-time manager were no more successful in terms of innovation, regardless of the extent of experimentation. This finding is important in developed welfare states where costs are constrained.

The article has shown that our knowledge of NPG needs to recognize temporary employment and its effects on public sector projects. Uncertainty arising from temporary employment has been shown to reduce innovation. Of course the data were country- and policy-specific, so a comparative study of several countries and perhaps different policies would provide more robust evidence. Similarly, research with panel data or a field experiment based on public projects would give more reliable findings on the effect on innovation of the temporary employment of managers to deliver public sector projects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersen, L. B. (2016). Can command and incentive systems enhance motivation and public innovation? In J. Torfing, & P. Triantafillou (Eds.), Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance (pp. 237–255). Cambridge University Press.

- Anttiroiko, A.-V., Bailey, S. J., & Valkama, P. (2011). Innovations in public governance in the western world. In A.-V. Anttiroiko, S. J. Bailey, & P. Valkama (Eds.), Innovations in public governance (pp. 1–22). IOS Press.

- Bache, I. (2010). Partnership as an EU policy instrument: A political history. West European Politics, 33(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903354080.

- Bakker, R. M. (2010). Taking stock of temporary organizational forms: A systematic review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 466–486.

- Bevir, M., & Bowman, Q. (2011). Innovation in democratic governance. In A.-V. Anttiroiko, S. J. Bailey, & P. Valkama (Eds.), Innovations in public governance (pp. 173–193). IOS Press.

- Brulin, G., & Svensson, L. (2012). Managing sustainable development programmes. Gower.

- Büttner, S. M. (2019). The European dimension of projectification: Implications of the project approach in EU funding policy. In D. Hodgson, M. Fred, S. Bailey, & P. Hall (Eds.), The projectification of the public sector (pp. 169–188). Routledge.

- Clegg, S., Kornberger, M., & Pitsis, T. (2011). Managing & organizations. An introduction to theory and practice. Sage.

- Damanpour, F., Walker, R. M., & Avellaneda, C. N. (2009). Combinative effects of innovation types and organizational Performance: A longitudinal study of service organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 46(4), 650–675. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00814.x.

- Donahue, J. D., & Zeckhauser, R. (2011). Collaborative governance: private roles for public goals in turbulent times. Princeton University Press.

- Du Gay, P. (2000). In praise of bureaucracy—Weber, organization, ethics. Sage.

- Engwall, M. (2003). No project is an island: Linking projects to history and context. Research Policy, 32(5), 789–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00088-4.

- Fred, M. (2018). Projectification—the Trojan horse of local government. Lund University.

- Godenhjelm, S., & Johanson, J. E. (2018). The effect of stakeholder inclusion on public sector project innovation. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852315620291.

- Godenhjelm, S., Lundin, R. A., & Sjöblom, S. (2015). Projectification in the public sector – The case of the European Union. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 8(2), 324–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-03-2014-0027.

- Godenhjelm, S., Sjöblom, S., & Jensen, C. (2019). Project governance in an embedded state. In D. Hodgson, M. Fred, S. Bailey, & P. Hall (Eds.), The projectification of the public sector (pp. 149–168). Routledge.

- Grabher, G. (2002). Cool projects, boring institutions: Temporary collaboration in social context. Regional Studies, 36(3), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400220122025.

- Grabher, G. (2004a). Learning in projects, remembering in networks?: Communality, sociality, and connectivity in project ecologies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 11(2), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776404041417.

- Grabher, G. (2004b). Temporary architectures of learning: Knowledge governance in project ecologies. Organization Studies, 25(9), 1491–1514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604047996.

- Gripenberg, P., Sveiby, K.-E., & Segercrantz, B. (2012). Challenging the innovation paradigm: The prevailing pro-innovation bias. In K.-E. Sveiby, P. Gripenberg, & B. Segercrantz (Eds.), Challenging the innovation paradigm (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

- Hartley, J. (2016). Organizational and governance aspects of diffusing public innovation. In J. Torfing, & P. Triantafillou (Eds.), Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance (pp. 95–114). Cambridge University Press.

- Hodgson, D. E. (2004). Project work: The legacy of bureaucratic control in the post-bureaucratic organization. Organization, 11(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508404039659.

- Hodgson, D. E., Fred, M., Bailey, S., & Hall, P. (2019). Introduction. In D. E. Hodgson, M. Fred, S. Bailey, & P. Hall (Eds.), The projectification of the public sector (pp. 1–17). Routledge.

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19.

- Ika, L. A. (2009). Project success as a topic in project management journals. Project Management Journal, 40(4), 6–19.

- Jacobsen, M. L. F., & Thrane, C. (2016). Public innovation and organizational structure: Searching (in vain) for the optimal design. In J. Torfing, & P. Triantafillou (Eds.), Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance (pp. 217–236). Cambridge University Press.

- Jacobsson, B., Pierre, J., & Sundström, G. (2015). Governing the embedded state: The organizational dimension of governance. Oxford University Press.

- Jensen, A. F. (2012). The project society. Arhus University Press.

- Jensen, C., Johansson, S., & Löfström, M. (2006). Project relationships – A model for analyzing interactional uncertainty. International Journal of Project Management, 24(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.06.004.

- Jensen, C., Johansson, S., & Löfström, M. (2013). The project organization as a policy tool in implementing welfare reforms in the public sector. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 28(1), 122–137.

- Kovách, I., & Kučerova, E. (2009). The social context of project proliferation-the rise of a project class. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 11(3), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080903033804.

- Le Galés, P. (2011). Policy instruments and governance. In M. Bevir (Ed.), The Sage handbook of governance (pp. 142–159). Sage.

- Lundin, R. A., Arvidsson, N., Brady, T., Ekstedt, E., Midler, C., & Sydow, J. (2015). Managing and working in project society: Institutional challenges of temporary organizations. Cambridge University Press.

- Lundin, R. A., & Söderholm, A. (1995). A theory of the temporary organization. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 11(4), 437–455.

- Lynn, L. E. J. (1981). Managing the public’s business: The job of the government executive. Basic Books.

- Lynn, L. E. J. (2006). Public management: Old and new. Routledge.

- Marsden, T., Sjöblom, S., Andersson, K., & Skerratt, S. (2012). Exploring short-termism and sustainability: Temporal mechanisms in spatial policies. In S. Sjöblom, K. Andersson, T. Marsden, & S. Skerratt (Eds.), Sustainability and short-term policies. Improving governance in spatial policy interventions (pp. 1–16). Ashgate.

- Meredith, J., & Mantel, S. J. J. (2018). Project management: A managerial approach (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Meyerson, D., Weick, K. E., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research. Sage.

- Munck af Rosenschöld, J., & Wolf, S. A. (2017). Toward projectified environmental governance? Environment and Planning, 49(2), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16674210.

- Nugent, N. (2017). The government and politics of the European Union (8th edn). Macmillan.

- Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1992). Re-Inventing government. Addison-Wesley.

- Osborne, S. (2010). Conclusions - Public governance and public services delivery: a research agenda for the future. In S. Osborne (Ed.), The new public governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance (pp. 413–428). Routledge.

- Osborne, S., & Brown, L. (2013). Introduction: Innovation in public services. In S. Osborne, & L. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of innovation in public services (pp. 1–14). Edward Elgar.

- O’Toole, L. J. J., & Meier, K. J. (2010). Implementation and managerial networking in the new public governance. In S. Osborne (Ed.), The new public governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance (pp. 338–352). Routledge.

- Piattoni, S., & Polverari, L. (2016). Handbook on Cohesion Policy in the EU. Edward Elgar.

- Pollitt, C. (2003). The essential public manager. Open University Press.

- Raab, J., Soeters, J., van Fenema, P., & de Waard, E. (2009). Structure in temporary organizations. In P. Kenis, M. Janowicz-Panjaitan, & B. Cambré (Eds.), Temporary organizations—Prevalence, logic and effectiveness (pp. 171–200). Edward Elgar.

- Rowley, J., Baregheh, A., & Sambrook, S. (2011). Towards an innovation-type mapping tool. Management Decision, 49(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111094446.

- Sahlin-Andersson, K., & Söderholm, A. (2002). The Scandinavian school of project studies. In K. Sahlin-Andersson, & A. Söderholm (Eds.), Beyond project management: New perspectives on the temporary - permanent dilemma. Liber ekonomi.

- Saunders, C. S., & Ahuja, M. K. (2006). Are all distributed teams the same? Differenting between temporary and ongoing distributed teams. Small Group Research, 37(6), 662–700.

- Sjöblom, S., & Godenhjelm, S. (2009). Project proliferation and governance—Implications for environmental management. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 11(3), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080903033762.

- Sjöblom, S., Löfgren, K., & Godenhjelm, S. (2013). Projectified politics —Temporary organizations in a public context. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 17(2), 3–12.

- Skelcher, C., & Sullivan, H. (2008). Theory-driven approaches to analysing collaborative performance. Public Management Review, 10(6), 751–771. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14719030802423103.

- Sørensen, E. (2012). Governance and innovation in the public sector. In D. Levi-Faur (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of governance (pp. 215–227). Oxford University Press.

- Too, E. G., & Weaver, P. (2014). The management of project management: A conceptual framework for project governance. International Journal of Project Management, 32(8), 1382–1394.

- Torfing, J., & Triantafillou, P. (2016). Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance? In J. Torfing, & P. Triantafillou (Eds.), Enhancing public innovation by transforming public governance (pp. 1–32). Cambridge University Press.

- Vento, I. (2020). Public innovation – Concept, praxis, and consequence. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance (pp. 1–5). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3886-1.

- Virtanen, T. (2016). Roles, values, and motivation. In C. Greve, P. Laegreid, & L. H. Rykkja (Eds.), Nordic adminstrative reforms: Lessons for public management (pp. 79–103). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Walker, R. M. (2006). Innovation type and diffusion: An empirical analysis of local government. Public Administration, 84(2), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00004.x.

- Walker, R. M. (2008). An empirical evaluation of innovation types and organizational and environmental characteristics: Towards a configuration framework. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 591–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum026.

- Walker, R. M., Avellaneda, C. N., & Berry, F. S. (2011). Exploring the diffusion of innovation among high and low innovative localities: A test of the Berry and Berry model. Public Management Review, 13(1), 95–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.501616.