?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.IMPACT

This article advances a new form of leadership—audit leadership—for cultivating internal audit quality in medical clinics. The authors document the power of audit leadership, manifested by two facets—professional and relational behaviours—for developing a work environment in which people develop interpersonal trust and psychological safety, which is conducive for internal audit quality. The authors show how managers of medical clinics can shape a work environment in which internal audit is embraced and supported in ways that can help the units to perform at higher levels. Importantly, internal audit, often viewed as an unproductive organizational function, enables learning, process improvement and is a deterrence against potential transgressions. This article will be of particular interest to financial, accounting and management scholars, as well as professional auditors, managers, accountants and financial experts.

ABSTRACT

This article provides a novel contribution to the literature of public sector organizations in general and healthcare organizations in particular. The authors explore the ways leaders help facilitate internal audit quality and drive work performance by employing a mixed-methods approach in which qualitative data was collected to construct a new concept—audit-enabling leadership—followed by time-lagged data collected from multiple respondents. The findings indicate that two facets—professional and relational behaviours— constitute audit-enabling leadership.

Internal audit is a key managerial mechanism that has significant implications for ethical, responsible, efficient and effective organizational processes and outcomes. It has been described as an ongoing management check process of comparing behaviours, actions and outcomes against standards or expectations, based on relevant indices, to improve an organization’s processes and effectiveness (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Globerson & Globerson, Citation1990). Internal audit can also help where organizational control mechanisms have failed to detect and spur immediate improvement (Krishnan, Citation2005), thus contributing to a greater alignment between organizational members’ actions and the desired direction and ends of the organization in general (Cardinal, Citation2001). Moreover, data from an audit can facilitate positive change (Goodman & Ramanujam, Citation2012). By identifying the disparity between the desired ends and reality and analysing its consequences, internal audit can be powerful in driving better work outcomes in organizations and developing safer and more reliable systems, particularly in organizations that operate under difficult conditions, such as emergency rooms in hospitals, aircraft carriers and nuclear facilities (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001).

Recognizing the value of organizational audit led organizational scholars (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Globerson & Globerson, Citation1990) to study both external audit (Penini & Carmeli, Citation2010) and internal audit (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Ma’ayan & Carmeli, Citation2016). Some studies attempted to identify the antecedents of audit in organizations, while others focused on whether and why audit improves performance (for example Carmeli & Tishler, Citation2004a; Citation2004b; Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Ma’ayan & Carmeli, Citation2016). Particular attention has been paid to the influence of management support on internal audit (Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009). However, this line of research is still in the early stages of development, both conceptually and empirically:

Research has tended to focus on the level of support the organization’s leadership provides to the audit activity (Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009) and leadership behaviours, but did not reveal all the leadership facets that can enhance internal audit quality.

We can further advance the study of leadership–audit relationships by shifting the focus from generic leadership (for example transformational/transactional leadership) to specific leadership behaviours (i.e. behaviours focusing on specific outcomes such as safety and service) (Schneider et al., Citation2005). This can be useful theoretically to more precisely conceptualize the leadership facets that are conducive for a specific process, such as internal audit, as well as empirically by testing whether and why these specific leadership behaviours facilitate this particular activity.

Third, research needs to further advance theorizing about the process by which internal audit is facilitated in organizations (Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009), particularly about how leadership can have a positive influence and help develop internal audit quality.

Finally, our understanding of the mechanisms that leadership helps develop to facilitate internal audit quality and further drive work performance of organizational units, such as medical clinics, is limited. We need to better explain what is the type of leadership that produces internal audit quality and why, as well as how by facilitating such leadership better work performance can be fostered. This is even more important in medical clinics where the importance of internal audit translates into saving human lives through better work processes and medical treatment.

We addressed these theoretical issues by developing the concept of audit-enabling leadership, manifested by leaders who behave professionally and are relationally sensitive to others. We then tested a serial mediation model in which audit-enabling leadership, through the development of a climate of trust and psychological safety, facilitates internal audit quality driving up the performance of medical clinics. In so doing, we have contributed to the literature of organizational auditing (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Globerson & Globerson, Citation1990) by explaining why the professional and relational facets of leadership are particularly important for developing internal audit quality.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Internal audit quality

Internal audit ‘is a process that examines and evaluates the functioning of an organization (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996, p. 263) and compares actual performance against standards or expectations, based on relevant indices, to improve the organization’s achievements (Globerson & Globerson, Citation1990)’ (see Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009, p. 895). Internal audit differs from internal control in that audit is one of the methods where organizations develop and maintain organizational control, both formal (officially sanctioned (usually codified), institutional) and informal (non-official values, norms, shared values and beliefs) to guide behaviours and actions (Brink, Citation1982; Cardinal, Citation2001; Chambers et al., Citation1987; GAO, Citation1988).

Internal audit quality can be conceptualized as a multifaceted process of learning, deterrence, motivation and process improvement (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996). Specifically, internal audit:

Instructs the organization’s members how to better perform their jobs by pinpointing both major and minor issues that need to be addressed.

Deters members from behaviours or actions that may negatively influence the organization.

Enhances the motivation of members to learn from the audit activity.

Increases the likelihood that, by revealing errors and indiscretions as early as possible, the required work tasks are completed and in the right ways (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996) (in Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009, p. 895).

Internal audit is key to obtaining effective internal control in ways that avoid the repetition of errors and ensure alignment of actual work efforts to plans and procedures. However, it may be particularly essential for effective improvement of work processes, especially in inter-disciplinary groups facing complex challenges (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001), such as in health service units. In particular, this activity is key for ensuring high levels of safety and reliability (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001) for at least two reasons: it helps identify and address medical errors, bearing significant implications for human life (Abbott et al., Citation2005; Kohn et al., Citation2000); and it develops the knowledge bases that are particularly critical in medical services (Bohmer & Edmondson, Citation2001; Carroll & Edmondson, Citation2002; Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006).

Internal audit: perceptions of leaders and auditees

Despite its potential contribution to organizations in general and healthcare systems in particular, internal audit is not always perceived by leaders, and to a greater extent by auditees, as a vital process in the value chain, as compared with other activities, such as research and development, marketing and distribution. A key difficulty that scholars have noted is a tendency to view audit as a punishment which, not surprisingly, induces negative reactions and feelings (Mints, Citation1972). Moreover, people tend to associate audit with excessive bureaucracy (Arena & Azzone, Citation2009): a view that leads to a need to depreciate the value of the audit activity and a tendency to avoid, or worse, not to co-operate with it.

Thus, scholars have advanced an approach that enhances the willingness to comply and even embrace the audit activity, which emphasizes guidance, learning and process improvement (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996) as a way to transform the negative perceptions often held by auditees and other organizational members and encourage them to co-operate with the audit activity. Research on team leadership in healthcare organizations suggests that leaders are enablers of a psychologically safe environment for learning (Baker & Denis, Citation2011; Bohmer & Edmondson, Citation2001) and can further be transformational for shaping a workplace culture (Bryman, Citation1989). We further suggest that transforming negative reactions to internal audit requires organizations and leaders to alleviate members’ concerns and convince them that audit is not about punishment but, rather, it is an effective managerial mechanism that can help the organization, its units and members to perform better (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Ma’ayan & Carmeli, Citation2016; Mints, Citation1972). However, a key question concerns how organizations and their leaders can shape perceptions and facilitate internal audit quality in ways that will improve organizational unit performance (Penini & Carmeli, Citation2010) and it remains unclear what specific leadership behaviours are conducive to facilitating internal audit quality and the conditions and mechanisms that such leadership develops to help facilitate it.

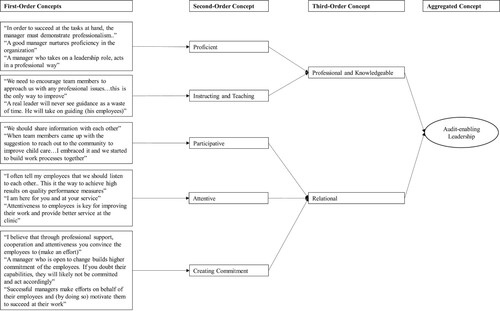

We advanced this line of research by developing the concept of audit-enabling leadership and theorizing about the socio-psychological conditions it develops to facilitate internal audit quality and improve the performance of medical clinics, even in resource-constrained settings. Drawing on Ha’elion’s (Citation1996) research, in-depth interviews, focus groups and a semi-structured pilot survey, we uncovered a specific set of leadership behaviours that facilitate internal audit quality. These can be classified into two multidimensional concepts:

Professional and knowledgeable leadership comprised of proficient behaviours and instructing and teaching behaviours.

Relational leadership, which is manifested by participative, attentive and commitment-based behaviours.

Professional and knowledgeable leaders are recognized by their followers and other constituencies as possessing substantial knowledge about the tasks and the context in which they are performed. Relational leaders invite others to engage in the process—they pay attention to the task requirements and the needs of those who perform them and they are committed to the organization by taking responsibility for their own performance and that of their followers.

Facilitating internal audit quality: audit-enabling leadership develops trust and psychological safety

We suggest that audit-enabling leaders, who behave professionally and are relationally sensitive to others, develop a climate of trust and psychological safety which facilitates internal audit quality in medical clinics. Trust refers to members’ ‘expectations, assumptions, or beliefs about the likelihood that another’s future actions will be beneficial, favorable, or at least not detrimental to one’s interests’ (Robinson, Citation1996, p. 576). As a relational concept, audit-enabling leadership captures the perceived risk of vulnerability of members within a connection (Rousseau et al., Citation1998). Psychological safety refers to perceptions members hold about an interpersonal context in which they ‘are comfortable being themselves’ (Edmondson, Citation1999, p. 354). As such, in a psychologically safe environment, unit members feel free to express concerns, self-doubts and their needs for learning in order to perform effectively (Kahn, Citation1990, p. 708).

Professional and knowledgeable leadership: When leaders act professionally, they instill trust in members through an increased sense of the integrity of each other’s behaviours. Following Mayer et al.’s (Citation2009) theorizing on the influence of leadership on team processes, we stress that leaders can act as role models, sending a clear message of integrity and benevolence that guides their choices and actions and those of others, thus helping to develop higher levels of trust, such as trust in each other. In addition, leaders convey their expectations from their employees (Vinarski-Peretz & Kidron, Citation2023). They set norms to engage in activities such as audit (Blay et al., Citation2019). Leaders also serve as role models by acting in a professional way such that team members engage in honest ways (rather than perpetuating political discourse) and with a sense of integrity towards each other in day-to-day activities. Further, when leaders are recognized as being knowledgeable and expert in their field, confidence grows in the competency of the leader and the medical clinic. In similar vein, professional and knowledgeable leaders create a psychologically safe environment in the medical clinic. Acting professionally is likely to mitigate members’ concerns associated with expressing themselves. Conversely, it is less likely that team members will express their opinions freely if leaders do not act in a professional way and act upon their knowledge (for example if they put political considerations first).

Relational leadership: We also suggest that relational leadership can build trust and psychological safety in medical clinics. When leaders act in a participative way, they send a clear signal to the team members that they are invited to engage and that their inputs matter (Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006). Leaders sending such messages of confidence in, and concern and respect for, their followers are likely to instill trust among members (Dirks & Ferrin, Citation2002), enabling them to develop trusting relationships and feel psychologically safe to share their perspectives and knowledge freely. Similarly, leaders who are attentive to team members’ needs create a holding environment of supporting and nurturing each other (see Kahn, Citation2001). Leaders also influence trust and psychological safety by creating commitment through behaviours that manifest in taking responsibility for the team and its performance. In this work climate, members feel that they can trust the team even if things do not progress as expected and feel motivated to express their ideas freely in ways that help the team succeed.

Trust and psychological safety as keys for internal audit quality: These socio-psychological mechanisms of trust and psychological safety are conducive to facilitating internal audit because they help in alleviating inherent concerns associated with being scrutinized. When discrepancies are identified through an internal audit process, trust allows members to realize that this activity is aimed to help improve rather than punish. In such a climate where integrity- and competence-based trust is developed, members are likely to be more receptive to the audit’s findings, realize its benefits and feel safe with it. Drawing on research about learning from failure in hospitals (Tucker & Edmondson, Citation2003), we suggest that a psychologically safe environment determines the approach towards internal audit and willingness to learn and benefit from this activity (see also Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009). This logic led us to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Audit-enabling leadership is indirectly, through trust, related to internal audit quality.

Hypothesis 2: Audit-enabling leadership is indirectly, through psychological safety, related to internal audit quality.

Internal audit quality and the performance of medical clinics

Audit is a fertile platform for learning how medical clinic members develop and refine their knowledge, skills and competencies in ways that enable their clinic to effectively perform the tasks at hand. This mode of learning enables medical clinics to improve performance by bridging knowledge gaps. Internal audit, however, can shift members’ perspectives regarding how to approach and conduct work tasks in medical clinics. Auditors may need a set of qualities (Langella et al., Citation2021) that evolve continuously to align with new developments (Barrett AO, Citation2022). These qualities are instrumental in helping auditees to develop a new or different viewpoint about how they approach and complete tasks, particularly through ‘systematic information gathering, questioning and clarifying (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996)’ (in Ma’ayan & Carmeli, Citation2016, p. 353).

Internal audit also provides an opportunity for feedback and critical reflection about the work processes and knowledge that can be created internally (DeShon et al., Citation2004). First, research suggests that when providing feedback members’ attention is likely to shift towards aspects that might otherwise be overlooked (Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996). Second, feedback drives subsequent engagement in setting goals (Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996) and helps build group potency (Prussia & Kinicki, Citation1996; Tindale et al., Citation1991).

Based on this reasoning, we developed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3. Internal audit quality is positively related to medical clinic performance.

Hypothesis 4. Audit-enabling leadership is indirectly, through trust and psychological safety, related to internal audit quality which, in turn, drives medical clinic performance.

Method

Sample and procedure

The study was carried out in Israel where all citizens and residents must be members of one of four healthcare providers (also known as ‘health funds’). These are public organizations that administer healthcare services and funding for their members. We collected both qualitative and quantitative data in six steps. First, one of the authors conducted semi-open interviews with 120 managers of whom 20 held senior leadership positions and 100 held middle-level managerial positions in one of the healthcare providers. Of these managers, 60% were also physicians. The interviews were conducted in each interviewee’s office. Their ages ranged from 30 to 60. The goal was to understand the leadership behaviours that are most effective in promoting and facilitating internal audit quality. During the interviews, the interviewer limited their involvement in the interview, allowing the interviewees to describe events and experiences to provide further specificity to their responses (Gabriel, Citation2000; Mishler, Citation1986) (guidelines for the semi-open interviews are available from the authors). Overall, participants were willing to openly share their perspectives about audit-enabling leadership.

Second, we analysed the interview data, following Gioia et al.’s (Citation2013) guidelines and devised the audit-enabling leadership construct which is best understood as an aggregated concept comprised of two third-order concepts: professional and knowledgeable leadership (proficiency and instructing and teaching); and relational leadership (participative, attentive and creating commitment). The logical shift from the first-order concept to the second-order concept to the third-order concept is based on Gioia (Citation2021); first-order concepts are informant-centred whereas second-order concepts are theory-centred data and findings (see ).

Third, we requested 20 employees working in audit in a variety of organizations, as well as 20 postgraduate students, to assess the generated measurement items that we constructed based on the qualitative data (for audit-enabling leadership). We were specifically interested in their assessment of which item manifests what dimension of the audit-enabling leadership. Overall, we received 34 (out of 40) responses and after some refinements we structured a multi-item measure of audit-enabling leadership.

Fourth, we conducted a pilot study with a focus group of about 20 managers and members of the audit unit in the healthcare fund to assess the survey items. We were particularly interested in the clarity of the items and assessing the extent to which items adequately reflected the construct they were meant to measure.

Fifth, we administered the final version of the structured survey at three points in time to members (employees) of the medical clinics in a single healthcare provider selected for the research because of the consent and support from its top management.

Sixth, we administered a survey to each of the clinic managers with the aim of assessing its performance. We collected data through structured surveys at four points in time, using five-month lags. The study involved a randomly selected sample of 80 out of the provider’s 1,378 clinics. Top management supported the project and all clinics that were selected agreed to participate in the study. Our interest was to survey both the employees in the medical clinics and their managers. The first author ensured that each participant received the survey in person and completed it voluntarily (at their discretion). We crafted two different structured surveys—one for the employees which was composed of three parts (at three different points in time (T1, T2 and T3) and the other (T4) for the managers. At Time 1, we administered surveys to 877 employees and received 806 completed surveys (a response rate of 91.90%); in this part of the survey, we collected data from employees regarding their audit-enabling leaders. At Time 2, we administered 806 surveys to the employees in the medical clinics and received 702 completed surveys (response rate of 80.04% from T1); in this part of the survey, employees reported their level of trust in the medical clinic and their perception of the medical clinic’s psychological safety. At Time 3, we administered 702 surveys to the employees in the medical clinics and received 586 completed surveys (response rate of 66.82% from T1); in this part of the survey, employees reported their medical clinics’ internal audit quality. Finally, at Time 4, we administered a survey to the 80 clinic managers, who were asked to assess the performance achievement of their own medical clinic. Research applying a time-lagged data design, using multiple respondents and different sources for the explanatory and dependent variables allows the mitigation of problems of common method bias and variance (Doty & Glick, Citation1998; Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). The surveys were administered and collected on site by the first author to increase the response rate by encouraging the participants to complete the survey parts. Of the participants (employees and managers), 35% were paramedics, 30% were medical doctors, 27% were nurses and the remainder were administrative employees; 41% were 20 to 40 years old, 56% were 41 to 60 years old and the rest were over the age of 60.

Measures

All survey/measurement responses were on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all, to 5 = to a very large extent.

Medical clinic performance: We adapted four items to the group (clinic) level that directly measure task-related (in-role) performance (α = .87) (Williams & Anderson, Citation1991). An example is: ‘This medical clinic adequately completes assigned duties’.

Internal audit quality: We utilized scale items employed in previous research (Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009) to assess internal audit quality and its four dimensions—learning (α = .93), motivation (α = .83), process improvement (α = .95) and deterrence (α = .85). Examples include: ‘Internal audit serves as a tool for learning work processes in my medical clinic’/‘The employees in my medical clinic resist internal auditing’ (a reverse-scored item).

Trust: This measure was assessed by six items from Robinson’s scale (Citation1996). We replaced ‘employer’ by ‘medical clinic’ following comments received in the pilot study (α = .93). An example is: ‘In general, I believe that the motives and intentions of members of my medical clinic are good’.

Psychological safety: We used six items from the scale employed by Edmondson (Citation1999) (α = .90). An example is: ‘It is safe to take a risk in my medical clinic?’

Audit-enabling leadership: We constructed this measure following our qualitative data and generated 24 items, which we then assessed through a pilot study (Step 4) for construct validity. Following a factor analysis, we removed two items of the dimension—instructing and teaching. Thus, we used a final set of 22 items to measure audit-enabling leadership. Since this is a second-order latent construct, we first performed exploratory principal factor analysis using MSA—Kaiser’s Measure of Sampling Adequacy (Kaiser, Citation1970). This measure gives an indication of whether a particular variable belongs psychometrically to a latent factor. MSA(i)-Kaiser values for measurement items ranged from .84 to .95, which is a clear indication that it is appropriate for factor analysis (Kaiser, Citation1970) (see ). Then, we calculated the average for the selected items on each dimension. This produced the dimensions that constituted the second-order latent construct. MSA(i) for the third-order dimensions of the two second-order dimensions (professional and knowledgeable and relational) ranged from .85 to .91, above the cutoff value of .60. Examples are: ‘My manager professionally supports their employees in organizational processes at work’ and ‘My manager builds commitment among their followers at work’. Using a separate sample, we also tested the convergent and discriminant validity of the audit-enabling leadership concept. The results suggested that audit-enabling leadership is a valid construct and that it clearly diverges from and converges with the Ohio State leadership behaviours—consideration and initiating structure (Judge et al., Citation2004) (the correlation matrix and the fit-of-indices for the model structure results are available from the authors).

Controls: We also controlled for gender, tenure in the organization and family status because of their potential to explain differences in perceptions of the internal audit activity. We controlled for family status (1 = single, 2 = married or partnered) because unmarried individuals might develop lower levels of trust (Lindström, Citation2012) and lower levels of commitment, thus affecting the relationship between relational audit-enabling leadership and performance via trust.

Data analysis: We first drew up descriptive statistics at level 1 (individual) followed by level 2 (medical clinic). Second, we performed aggregation (homogeneity and reliability) tests (ICC1, ICC2, Rwg and ADM). Third, we examined the shape of the relationships between the aggregated (level 2) measures using two different models: LOESS and SPLINE. LOESS is a well-known instrument in performing a regression analysis to help in seeing relationships between variables and expected trends, by creating a smooth line through a time plot or scatter plot (Cleveland & Devlin, Citation1988). Spline regression is a method for testing non-linearity in the explanatory variables and for modeling non-linear functions (Racine, Citation2018). When fitting a LOESS model, s(x) is a component manifesting the fit between X and Y. Spline models divide the space of data into different regions and approximate the function in each one by linear, quadratic or cubical regression (an example can be found in Binyamin & Carmeli, Citation2017). Fourth, we assessed the research model using structural equation modeling (SEM) for aggregated data. This procedure also included an assessment of all direct and indirect effects and their bootstrap confidence intervals using MPLUS.

Results

The descriptive statistics (sample size, mean and SD) for the variables at levels 1 and 2 are provided in , and the matrix of correlations appears at both levels in , respectively. After carrying out a series of measurement tests for the key constructs in our model and establishing its conceptual structure, we performed CFA using Mplus 6 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2008).

Table 1(a). Descriptive statistics of the variables (level 1).

Table 1(b). Descriptive statistics of the variables (based on randomly sampled respondents) (level 2).

Table 2(a). Correlations between the research variables (level 1).

Table 2(b). Correlations between the research variables (level 2).

CFA for the four constructs of the basic model measurement structure (audit-enabling leadership, internal audit quality, trust and psychological safety) was performed at the individual level. In order to account for the hierarchical nature of the data at the individual level, with workers nested in clinics, all CFA analyses at the individual level were conducted using the Mplus option ‘type = COMPLEX’ with medical clinics treated as clustering variables. In addition, we performed CFA using maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a chi-square test statistic that are robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations when used with type = COMPLEX command. Due to the limitation on the number of clinics, the baseline measurement model converged only while using the averages of the items of the first-order constructs of audit-enabling leadership and internal audit quality and using these averages as indicators for the second- and third-order factors of these constructs.

We conducted a series of CFAs to assess the fit of the baseline measurement model versus alternative measurement models. The fit of the four-factor model (audit-enabling leadership, trust, psychological safety and internal audit quality) was compared to models in which highly correlated variables were merged onto one factor. Alternative model 1 included three factors (merging psychological safety and internal audit quality) and alternative model 2 consisted of a one-factor structure (with all variables merged onto one factor). The findings indicate that the hypothesized conceptual model had a better fit with the data (χ2 = 369.09; df = 181[χ2/df = 2.04]; AIC = 23574.17; CFI = .986; TLI = .984; RMSEA = .048; SRMR = .024) than the alternative models (see ).

Table 3. Fit-of-indices for the measurement models.

Table 4. SEM results for the baseline model.

We used the multilevel library of R program (Bliese, Citation2008) to run aggregation tests for all variables, except for medical clinic performance, which was measured at the clinic level, using ICC1 and ICC2 (Bliese, Citation2000), Rwg (Klein & Kozlowski, Citation2000) and average deviation around mean (ADM) (Burke et al., Citation1999). The clinic size ranged from three to 14 responding members, with the majority having more than four respondents. Aggregation indices tend to be influenced by group size, so we ran aggregation with and without a medical clinic of three respondents. Rwg(j) for medical clinic trust and medical clinic psychological safety were .88 and .87. We did not test for audit-enabling leadership and internal audit quality because these are third- and second-order constructs. The values of ADM for trust and psychological safety were .57 and .67. ICC1 and ICC2 values were: audit-enabling leadership (.70, .90), trust (.53, 89), psychological safety (.59, .91) and internal audit quality (.71, .94) and F was statistically significant for all (p < .05). All these indices demonstrate both agreement and consistency among individuals within medical clinics, hence justifying aggregation.

Preliminary test of the relationships between the research variables at level 2

In order to test the relationships between the research variables at the medical clinic level, participants’ variables were aggregated to this group level using averages over the clinic’s individuals. Although clinic average is a crude estimate of clinic mean value, and has drawbacks at the group level, it provides an approximate representation of the relationships between the research variables at the group (in this case medical clinic) level (Preacher et al., Citation2010).

We used two different types of nonparametric models to examine the shape of the relationships between the research variables: the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) model (in which the relationship between the independent variable X and the dependent variable Y is given by the expression , where s(x) expresses the shape of the relationship between X and Y); and the smoothing spline model (in which the relationship between the independent variable X and the dependent variable Y is given by the expression

, where s(x) expresses the shape of the relationship between X and Y, after subtracting the linear component, to indicate whether an additional component is needed beyond the linear component and its shape). To estimate these models, we utilized the GAM (generalized additive models) procedure of SAS (version 9.2). Overall, these analyses indicate that an additional component beyond the linear one is not needed in any of the relationships between the research variables.

Model comparisons and test of the hypotheses

In view of the high correlations between the variables, we used random sampling of respondents per clinic (group). As each sampling was done separately for each factor, the respondents in different groups did not completely overlap (hence minimizing further the same source bias problem). For each clinic, the number of randomly sampled respondents was equal. Sampling at equal size from each group addresses a claim against using group means when group sizes are different (see Bliese, Citation2000; Bryk & Raudenbush, Citation1992). These randomly sampled values were averaged for each clinic and the relationships between the aggregated variables were examined. After such sampling, MSEM (multi-level structural equation modeling), which can be useful (Preacher et al., Citation2010), cannot be performed, hence aggregation, as described above, is necessary. Since the sample size was 80 clinics, we needed to consider a number of parameters that would yield a reliable solution of the model—so we used observed variables, instead of indicators, for the main research variables. We tested for the most parsimonious model and thus removed relationships between variables that were not statistically significant and did not contribute to a better fit with the data (χ2) and generated higher AIC values.

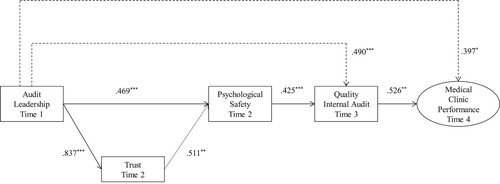

The SEM results indicate that our hypothesized multiple and sequential indirect relationships between audit-enabling leadership, internal audit quality and medical clinic performance is supported. As illustrated in , there was a significant relationship between audit-enabling leadership and both trust and psychological safety. In addition, trust was indirectly related (through psychological safety) to internal audit quality. Audit-enabling leadership was directly and indirectly related to both internal audit quality and medical clinic performance. This model has a good fit with the data: χ2 = 40.506, df = 26, χ2/df = 1.557, AIC = 787.273, Bayesian (BIC); 875.408; CFI = .977; TLI = .957; RMSEA = .084 and SRMR = .035. The results did not indicate statistically significant relationships between the control variables and the medical clinic performance.

Figure 2. Illustrative results of the model.

Notes: Dashed lines denote direct relationships; Dashed lines denote link that were not originally hypothesized; Trust-quality internal audit link is not shown (because only significant relationships are shown here), but was originally hypothesized.

**p < .01; ***p < .001; Control variables are not shown here.

We also tested three alternative models and compared them with the illustrative model in . We present the results of these analyses in , where the illustrative model in is listed as the baseline model. None of the alternative models showed statistically significant better fit with the data.

Indirect and total effects

We also examined the indirect influence of the variables in the model and their statistical significance by calculating confidence intervals (CI). CI of 10% was used to obtain fit of the one-sided tests (α < .05), as well as bias corrected CI based on 10,000 bootstrap replicates using Mplus (Preacher et al., Citation2010). The findings were (see :

Indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership on internal audit quality:

Path 1: AL→ TRU → PS → IAQ. The indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on internal audit quality (IAQ) via trust (TRU) and psychological safety (PS) was significant: (.18), 90% CI: [.09, .30].

Path 2: AL→ PS → IAQ. The indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on internal audit quality (IAQ) via psychological safety (PS) was significant: (.20), 90% CI: [.10, .34].

Total indirect effects: of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on internal audit (IAQ) quality (path 1 + path 2) were significant: (.38), 90% CI: [.22, .55].

Total indirect effects: of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on internal audit quality (IAQ) (path 1 + path 2 + AL → IAQ) were significant: (.87), 90% CI: [.77, .96].

Indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership on medical clinic performance:

Path 3: AL→ TRU → PS → IAQ → UP. The indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on medical clinic performance (UP) via trust (TRU), psychological safety (PS) and internal audit quality (IAQ) was significant: (.09), 90% CI: [.04, .18].

Path 4: AL→ PS → IAQ → UP. The indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on medical clinic performance (UP) via psychological safety (PS) and internal audit quality (IAQ) was significant: (.10), 90% CI: [.04, .22].

Path 5: AL→ IA → UP. The indirect effect of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on medical clinic performance (UP) via internal audit quality (IAQ) was significant: (.26), 90% CI: [.14, .47].

Total indirect effects: of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on medical clinic performance (UP) (paths 3 + 4 + 5) were significant: (.46), 90% CI: [.25, .70].

Total effects: of audit-enabling leadership (AL) on medical clinic performance (UP) (paths 3 + 4 + 5 + AL → CP) were significant: (.85), 90% CI: [.65, 1.03].

Effect of trust on internal audit quality:

Path 6: Tru → PS → IAQ. The indirect effect of medical clinic trust (TRU) on internal audit quality (IAQ) via psychological safety (PS) was significant: (.21), 90% CI: [.11, .35].

Path 7a: The total effect of trust on internal audit quality: (.28), 90% CI: [.13, .43].

Path 7b: The indirect effects of trust on internal audit quality: (.18), 90% CI: [.08, .36].

Path 7c: The direct effect of trust on internal audit quality: (.10, n.s.), 90% CI: [-.10, .27].

Effect of trust on medical clinic performance:

Path 12: TRU → PS → IAQ → UP. The indirect effect of trust (TRU) on medical clinic performance (UP) via psychological safety (PS) and internal audit quality (IAQ) was significant: (.11), 90% CI: [.05, .21].

Path 8a: The total effect of medical clinic trust on medical clinic performance (UP): (.14), 90% CI: [.00, .33].

Path 8b: The indirect effects: (.11), 90% CI: [.04, .21].

Path 8c: The direct effect of trust on medical clinic performance: (.03), 90% CI: [-.20, .23].

Effect of psychological safety on medical clinic performance:

Path 9: PS → IAQ → UP. The indirect effect of psychological safety (PS) on medical clinic performance (UP) via internal audit quality (IAQ) was significant: (.22), 90% CI: [-.38, .18].

Path 10a: The total effect of psychological safety (PS) on medical clinic performance: (.14), 90% CI: [-.11, .42].

Path 11b: The indirect effects: (.24), 90% CI: [.11, .43].

Path 12c: The direct effect of psychological safety (PS) on medical clinic performance: (-.10), 90% CI: [-.38, .18].

Overall, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were only partially supported as audit-enabling leadership was directly related to internal audit quality, as well as indirectly, through trust and psychological safety. Hypothesis 3 was supported as there was a positive link between internal audit quality and medical clinic performance. Finally, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported as audit-enabling leadership is both directly and indirectly, through trust, psychological safety and internal audit quality, related to medical clinic performance.

Table 5(a). SEM results for baseline and alternative models.

Table 5(b). Indirect and total effects for audit-enabling leadership on internal audit quality (AL → IAQ).

Table 5(c). Indirect and total effects for audit-enabling leadership on medical clinic performance (AL → UP).

Table 6. Measurement items and sources and MSA-Kaiser values.

Discussion

Our results indicate that leaders who are knowledgeable, act professionally and exhibit relational behaviours create conditions of trust and psychological safety in their medical clinics. We also found that trust is related to internal audit quality through psychological safety. In addition, we found that psychological safety facilitates internal audit quality which, in turn, drives a clinic’s performance. Finally, audit-enabling leadership is both directly and indirectly, through trust and psychological safety, related to internal audit quality, as well as directly and indirectly, through a sequential process of trust, psychological safety and internal audit quality, thereby influencing the performance of medical clinics.

Our research advances the literature on internal audit in organizations in general and healthcare settings in particular. Internal audit quality is key to improving work processes and outcomes in organizations (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Globerson & Globerson, Citation1990). It allows the development of better control mechanisms (Cardinal, Citation2001) by which a more reliable organizational system can be built, particularly in organizational units such as healthcare medical clinics working in difficult conditions (Weick & Sutcliffe, Citation2001). More specifically, internal audit is vital in medical clinics where members address health issues of patients on a daily basis and are responsible for providing them with safe and effective treatment (Abbott et al., Citation2005). The audit gives an opportunity for feedback where decision-makers are better informed and work outcomes of clinical procedures can be improved significantly.

Our study extends research on both the antecedents and implications of audit activities in organizations (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Globerson & Globerson, Citation1990) and healthcare organizations (Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009). In particular, we have extended the research on how audit can be effective in medical clinics by expanding on the four facets of internal audit quality: learning, motivation, process improvement and deterrence (Eden & Moriah, Citation1996). We have also explained why internal audit that allows auditees to learn from the activity motivates them to engage in the process and enables them to improve work processes and avoid potential pitfalls at work. We suggest that internal audit, which is often viewed as an unproductive organizational function, enables learning, process improvement and deterrence against potential transgressions, all of which bear positive implications that are either tangible (i.e. economic benefits, patient safety, error prevention) or intangible (i.e. knowledge assets).

Further, we shift the discussion from management support in audit (Penini & Carmeli, Citation2010) to specific leadership behaviours that leaders of medical clinics exhibit to facilitate this activity. This is important because we need to identify the set of behaviours that are specifically aimed at advancing specific activities (see Schneider et al., Citation2005). In particular, we depart from research focusing on management support in audit activity (for example Carmeli & Zisu, Citation2009), and research examining a single facet of leadership, by shedding light on the multifaceted nature of audit-enabling leadership that leaders of medical clinics exhibit to facilitate effective internal audit processes and improve their clinic’s performance. Our research shows that leaders of medical clinics may have the capacity to transform the negative perceptions that members hold on internal audit. They can do this by behaving professionally and demonstrating relational sensitivity to the auditees about their fears and concerns. Leaders can further help in developing a socio-psychological climate of trust and psychological safety in which members of their medical clinic are more receptive to the audit activity, thus potentially contributing to greater reliability. We further explain that leadership is particularly important because medical clinics and their members, despite recognizing the importance of internal audit, are often fearful of it and develop negative or non-constructive views about its essence and substance (Arena & Azzone, Citation2009; Eden & Moriah, Citation1996; Ma’ayan & Carmeli, Citation2016; Mints, Citation1972). By constructing a new concept, audit-enabling leadership, we hope to open up a new line of research that specifies the cognitive, behavioural and emotional conditions through which this leadership can facilitate audit activities in organizations in general and healthcare systems in particular. We point to the importance of advisory and instructional as well as relationally-oriented leadership that can make a positive influence. Finally, we elaborate on the socio-psychological conditions conducive to effective audit and higher levels of performance of medical clinics. This is key because operating with the purpose of achieving quality patient care in medical clinics is challenging and the suboptimal conditions under which they often work impede effective functioning. Knowledge and professionalism alongside relational behaviours that leaders display help in shaping the socio-psychological conditions that facilitate audit quality, which is vital for cultivating quality management in healthcare organizations.

Empirically, by using a mixed-method approach of collecting both qualitative and quantitative data, we were able to enhance triangulation, namely increasing the validity of the constructs and inquiry results by reducing the inherent method bias (Gibson, Citation2017; Greene et al., Citation1989). We constructed a new way to assess leadership that enables and facilitates internal audit quality activities. In addition, using time-lagged survey data, which has rarely been applied in research on audits in organizations, allowed us to shed light on how audit-related leadership facilitates internal audit quality and enhances medical clinic performance.

Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations and opens up new opportunities for research. First, we cannot ascertain full sample representation of the entire population. This is not an easy issue to resolve, but it is important to caution against generalized inferences. Hence, we call for cautious interpretation of the findings of our study and particularly their generalizability to other industries, because the healthcare sector is very different in the types of care and attention given to patients and the structural constraints in which medical clinics operate. We used structured surveys to collect the data, which may result in common method bias (for example Doty & Glick, Citation1998), but attempted to reduce the measurement bias by temporally separating measures of the variables across four different points in time (Mitchell & James, Citation2001) and collecting data from several sources, namely managers and employees. This five-month time-lag design helped to mitigate the effect of respondents’ consistency. Second, a possible limitation that arises from our use of observed variables concerns the lack of measurement error, which may pose a threat to the establishment of a causal relationship. Third, we do not have reason to assume that medical clinics operate differently but socio-cultural differences across countries may play a role that we did not capture here in our sample of medical clinics of a healthcare fund in Israel. Fourth, our endeavour to construct a new form of leadership that specifically aims at facilitating internal audit quality is a key theoretical and practical advancement, but we need further research to validate it by applying it in different settings, particularly with regard to criterion validity. Fifth, there were high correlations between the key research variables at the group level, which, although expected and assessed here, need to be considered. Sixth, we derive two socio-psychological conditions through which leaders can facilitate internal audit quality, but it is important to note that other unobserved mechanisms may be involved. We also did not examine why some leaders believe internal audit quality to be important and others do not but, rather, we focused on how specific leadership behaviours influence this activity and the performance of medical clinics. This is an important question because understanding the motives underlying leaders’ behaviours and actions with regard to internal audit can shed light on potential leadership development programmes. In addition, understanding their motives can inform us whether some managers have an interest in maintaining uncertainty to preserve their power and enjoy greater managerial discretion. Seventh, we implied that internal audit quality can be beneficial for performance but did not examine the relative influence vis-à-vis extrinsic motives. In a broader perspective, communities of scholarship and practice may benefit from expanding research on the importance of trust in audit activities. Eighth, because all clinics were monitored by the same audit unit, we acknowledge the potential impact of the audit unit’s behaviours, but our empirical design did not allow us to investigate this potential influence. We encourage future research examining this potential effect of the audit unit and its auditors and the socio-psychological conditions, perceptions of audit quality and subsequent performance. Finally, we focused on specific (task or in-role) performance but future research can advance this line of work by examining the social and economic performance implications.

Implications for policy and practice

Our research also has important policy and practical implications. This study was conducted in the context of medical clinics, where employees work under time pressure with high workloads. In this context, ongoing improvement through internal audit translates into saving human lives though better processes and the elimination of medical errors. We have shown how managers can facilitate internal audit by engaging in specific actions that promote it and help employees overcome their negative perceptions of audit (Arena & Azzone, Citation2009; Mints, Citation1972). The use of audit information can be powerful in facilitating changes and further improvements in processes and outcomes as it offers opportunities for learning, knowledge creation and, ultimately, quality improvements in healthcare settings. Specifically, organizations and managers that display audit-enabling leadership behaviours can motivate employees to contribute to internal audit quality by framing it as an effective managerial mechanism that will enable them to perform better across work groups and domains. A more positive perspective about the internal audit activity may be achieved if the medical clinics and the auditors shift their attention to audit as instructional, learning and improvement opportunities. In this regard, tolerance towards mistakes should be the guiding principle for both auditors and the management of the audited medical clinics as it helps facilitate learning and drives performance.

This requires a shift in the policy of the organization towards the audit activity, as well as the auditors towards it. It is essential to approach the practice of audit not as merely a way to detect errors. Such an approach only intimidates auditees and creates barriers that inhibit any constructive ways for co-operative engagement on their part. Instead, viewing the practice of audit as an opportunity to learn and improve processes can create positive dynamics between auditors, organizations and their audited medical clinics. Errors and mistakes, observed through the audit activity, are fertile ground for new insights and are not tools for punishment. Moreover, this approach can actually facilitate the process by which auditors and auditees work co-operatively and allow a full spectrum of mistakes to be revealed—creating more opportunities for new knowledge creation. This can be accomplished by relational support and professionalism on the part of the organizational leaders. They shape the context for audit as a resource for learning, knowledge creation and work improvements by shifting the focus from audit as simply an error-detecting machine to audit as a way to co-operatively explore with auditors what can be learned and improved and how. This suggests a broader call for universities to teach about the value of a new policy and a new perspective about audit as a mutual process between auditors and organizations and their auditees for learning and process improvement.

Acknowledgements

We thank Public Money & Management’s editors and two anonymous reviewers of this journal for their helpful comments and suggestion. In addition, we thank Ayala Cohen and Etti Doveh for their help with the data analysis. We also acknowledge the financial support from the Jeremy Coller Foundation and the Henry Crown Institute of Business Research in Israel. We also acknowledge the editorial work of Gerda Kessler.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Malka Zisu

Malka Zisu is an independent scholar. She earned her PhD from Bar-Ilan University, Israel. She is an expert on audit and has held executive and professional roles in this area in the healthcare system. Her research interest focuses on internal audit system and processes in medical settings.

Natalie Shefer

Natalie Shefer is at the Coller School of Management, Tel Aviv University, Israel. Her research sits at the intersection of three domains of strategic management scholarship: executive personality, corporate governance and strategic decision-making.

Abraham Carmeli

Abraham Carmeli is faculty member at Tel Aviv University, Israel. His current research interests include leadership and top management teams, relational dynamics, learning from failures, knowledge creation and creativity and innovation in the workplace.

References

- Abbott, R. L., Weber, P., & Kelley, B. (2005). Medical professional liability insurance and its relation to medical error and healthcare risk management for the practicing physician. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 140(6), 1106–1111.

- Arena, M., & Azzone, G. (2009). Identifying organizational drivers of internal audit effectiveness. International Journal of Auditing, 13(1), 43–60.

- Baker, G. R., & Denis, J. L. (2011). Medical leadership in health care systems: From professional authority to organizational leadership. Public Money & Management, 31(5), 355–362.

- Barrett AO, P. (2022). New development: Whither the strategic direction of public audit in an era of the ‘new normal’? Public Money & Management, 42(2), 124–128.

- Binyamin, G., & Carmeli, A. (2017). Fostering members’ creativity in teams: The role of structuring of human resource management processes. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 11(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000088

- Blay, A. D., Gooden, E. S., Mellon, M. J., & Stevens, D. E. (2019). Can social norm activation improve audit quality? Evidence from an experimental audit market. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(2), 513–530.

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability. In K. J. Klein, & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Bliese, P. D. (2008). Multilevel: Multilevel functions. R package version 2.3. Retrieved Feb 1, 2011 from http://cran.r-project.org/doc/contrib/Bliese_Multilevel.pdf.

- Bohmer, R. M., & Edmondson, A. (2001). Organizational learning and health care. Health Forum Journal, 44(2), 32–5.

- Brink, V. Z. (1982). Modern international auditing. John Wiley and Sons.

- Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications.

- Bryman, A. (1989). Leadership and culture in organisations. Public Money & Management, 9(3), 35–41.

- Burke, M. J., Finkelstein, L. M., & Dusig, M. S. (1999). On average deviation indices for estimating interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 2, 49–68.

- Cardinal, L. B. (2001). Technological innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: The use of organizational control in managing research and development. Organization Science, 12(1), 19–36.

- Carmeli, A., & Tishler, A. (2004a). Resources, capabilities, and the performance of industrial firms: A multivariate analysis. Managerial and Decision Economics, 25(6-7), 299–315.

- Carmeli, A., & Tishler, A. (2004b). The relationships between intangible organizational elements and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 25(13), 1257–1278.

- Carmeli, A., & Zisu, M. (2009). The relational underpinnings of quality internal auditing in medical clinics in Israel. Social Science & Medicine, 68(5), 894–902.

- Carroll, J. S., & Edmondson, A. C. (2002). Leading organizational learning in health care. BMJ Quality & Safety, 11(1), 51–56.

- Chambers, A., Selim, G. M., & Vinten, G. (1987). Internal auditing. Pitman.

- Cleveland, W. S., & Devlin, S. J. (1988). Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(403), 596–610.

- DeShon, R. P., Kozlowski, S. W., Schmidt, A. M., Milner, K. R., & Wiechmann, D. (2004). A multiple-goal, multilevel model of feedback effects on the regulation of individual and team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 1035.

- Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 611–628.

- Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1998). Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organizational Research Methods, 1(4), 374–406.

- Eden, D., & Moriah, L. (1996). Impact of internal auditing on branch bank performance: A field experiment. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 68, 262–271.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383.

- Gabriel, Y. (2000). Storytelling in organizations: Facts, fictions, fantasies. Oxford University Press.

- GAO. (1988). Government auditing standards.

- Gibson, C. B. (2017). Elaboration, generalization, triangulation, and interpretation: On enhancing the value of mixed method research. Organizational Research Methods, 20(2), 193–223.

- Gioia, D. (2021). A systematic methodology for doing qualitative research. The Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 57(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/00218863209827

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31.

- Globerson, A., & Globerson, S. (1990). Control and evaluation in organizations: Management by measurement. Tel Aviv University.

- Goodman, P. S., & Ramanujam, R. (2012). The relationship between change across multiple organizational domains and the incidence of latent errors. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 48(3), 410–433.

- Greene, J., Caracelli, V., & Graham, W. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11, 255–274.

- Ha’elion, T. (1996). The mediating processes between internal audit and organizational performance improvement. Unpublished thesis. Tel Aviv University.

- Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., & Ilies, R. (2004). The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.36

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724.

- Kahn, W. A. (2001). Holding environments at work. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 37(3), 260–279.

- Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35, 401–415.

- Klein, K. J., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (eds.). (2000). Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations. Jossey-Bass.

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). Effects of feedback intervention on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 254–284.

- Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. (2000). Errors in health care: A leading cause of death and injury. In L. T. Kohn, J. M. Corrigan, & M. S. Donaldson (Eds.), To err is human: Building a safer health system (pp. 26–47). National Academy Press.

- Krishnan, J. (2005). Audit committee quality and internal control: An empirical analysis. The Accounting Review, 80(2), 649–675.

- Langella, C., Anessi-Pessina, E., & Cantù, E. (2021). What are the required qualities of auditors in the public sector? Public Money & Management, 41(6), 466–476.

- Lindström, M. (2012). Marital status and generalized trust in other people: A population-based study. The Social Science Journal, 49(1), 20–23.

- Ma’ayan, Y., & Carmeli, A. (2016). Internal audits as a source of ethical behaviour, efficiency, and effectiveness in work units. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(2), 347–363.

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13.

- Mints, F. E. (1972). Behavioural patterns in internal audit relationships. The Institute of Internal Auditors.

- Mishler, E. G. (1986). Research interviewing: Context and narrative. Harvard University Press.

- Mitchell, T. R., & James, L. R. (2001). Building better theory: Time and the specification of when things happen. Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 530–547.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2008). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables (5th edn). Muthén & Muthén.

- Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 27(7), 941–966.

- Penini, G., & Carmeli, A. (2010). Auditing in organizations: A theoretical concept and empirical evidence. Systems Research and Behavioural Science, 27(1), 37–59.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

- Prussia, G. E., & Kinicki, A. J. (1996). A motivational investigation of group effectiveness using social-cognitive theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 187–198.

- Racine, J. S. (2018). A primer on regression splines. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/crs/vignettes/spline_primer.pdf.

- Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574–599.

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404.

- Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., Mayer, D. M., Saltz, J. L., & Niles-Jolly, K. (2005). Understanding organization-customer links in service settings. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1017–1032.

- Tindale, R. S., Kulik, C. T., & Scott, L. A. (1991). Individual and group feedback and performance: An attributional perspective. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 12, 41–62.

- Tucker, A. L., & Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Why hospitals don’t learn from failure: Organizational and psychological dynamics that inhibit system change. California Management Review, 45, 55–72.

- Vinarski-Peretz, H., & Kidron, A. (2023). Antecedents of public managers’ collective implementation efficacy as they actualize new public services. Public Money & Management, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2023.2203869

- Weick, K., & Sutcliffe, K. (2001). Managing the unexpected. Jossey Bass.

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviours. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617.