Abstract

Background and objectives

There is an unmet need for topical treatments with good tolerability in management of acne vulgaris. The present study aimed to evaluate efficacy and safety of a novel tretinoin (microsphere, 0.04%) formulation in combination with clindamycin (1%) gel for treatment of acne vulgaris.

Materials and methods

This phase 3 randomized, double-blind study included patients with moderate-to-severe acne. Patients were treated with tretinoin (microsphere, 0.04%) + clindamycin (1%) or one of the monotherapies (tretinoin, 0.025%; clindamycin, 1%). Key endpoints included percent change in lesion counts, and improvement in Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score.

Results

750 patients were randomized (combination, n = 300; tretinoin and clindamycin, each n = 150). At week 12, reductions in inflammatory (77%), non-inflammatory (71%) and total lesions (73%) were significantly greater with combination treatment versus either monotherapy (p < .03). Proportion of patients rated ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ with ≥2-grade ISGA improvement was higher with combination (46%) versus monotherapies (p < .02). Adverse events occurred in 20 patients, most were mild-moderate; no deaths or serious adverse events were reported. The discontinuation rates due to adverse events with combination therapy were low (≤1%).

Conclusion

The once-daily, microsphere-based formulation was generally tolerable with a positive impact on therapeutic outcomes and patients’ compliance.

ClinicalTrial Registration No.

CTRI/2014/08/004830

Introduction

Presence of acne is synonymous with teenage. Although the degree of acne severity differs from person-to-person, almost all individuals suffer from acne at some phase during adolescence or as young adults (Citation1). Acne vulgaris or acne is the most common dermatological disorder affecting approximately 9.4% of the global population, ranking it as the eighth most prevalent disease (Citation2). The presence of lesions and permanent scars due to acne present esthetic challenges, particularly during the adolescent years and frequently lead to emotional and psychosocial distress and negatively affects the quality of life (Citation3). Acne, an androgen-regulated disease of pilosebaceous follicles is characterized by non-inflammatory comedones and inflammatory papules, pustules and nodules (Citation4).

Acne is the most common skin condition in the United States, affecting about 50 million people annually (Citation4,Citation5). Epidemiology of acne in India is unknown due to lack of published data, but based on judgements from dermatological clinics across urban areas, prevalence of acne is thought to be similar as in Western population (Citation5). Hospital-based studies reported in Asian populations have shown that acne vulgaris constitutes 11.2–19.6% of the total new patients attending hospitals (Citation6,Citation7). In a hospital-based study from South India, it was found that 59.8% of acne cases were in the age group of 16–20 years, but patients aged ≥20 years were more likely to have more severe grade of acne vulgaris (Citation8). The prevalence rate of acne is similar to the historic data; among adolescents (12–17 years of age) the prevalence of acne was reported to be 50.6% in boys and 38.13% in girls (Citation8,Citation9).

Based on recent evidence-based guidelines from the European Dermatology Forum (European (S3) guidelines), the choice of treatment strategy for acne depends on disease activity that can be classified into four categories including comedonal acne, mild-to-moderate papulopustular acne, severe papulopustular or moderate nodular acne, and severe nodular or conglobate acne (Citation10,Citation11). In the current European S3 guidelines and the consensus report from the Global Alliance to improve outcomes in acne, combination treatment with topical retinoids and antimicrobials is recommended as frontline treatment option for acne management (Citation11–13).

Tretinoin, a retinoid derived from naturally occurring all-trans-retinol (Vitamin A1), when used topically decreases cohesiveness of follicular epithelium, normalizes keratinocyte desquamation and accelerates turnover of follicular epithelial cells causing extrusion of the comedones. Clindamycin has a direct bacteriostatic effect against Propionibacterium acnes in the pilosebaceous duct and also has an anti-inflammatory effect. An additional benefit of retinoid and clindamycin combination in comparison with antimicrobial monotherapy is its more rapid and better efficacy, possibly due to the retinoid normalizing desquamation and facilitating penetration of the antimicrobial agent into the subcutaneous follicle. This may decrease the exposure to antimicrobials, thus reducing the possibility of antimicrobial resistance (Citation14,Citation15). Several clinical studies have demonstrated that combination of tretinoin (0.025%) with clindamycin (1 or 1.2% as clindamycin phosphate) gel is more effective than the respective monotherapies for treatment of various stages of acne (Citation16–21); this could be due to the complementary mechanisms of action of these two agents that effectively target both inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions.

Although the effectiveness of topical tretinoin is well established, the skin irritation resulting in exfoliation, redness and photosensitivity can limit its use, particularly in patients with sensitive skin. Tretinoin-induced irritation depends on dose and formulation of the product (Citation22–25). Tretinoin gel microsphere (0.04%) is a novel formulation developed to minimize tretinoin-associated cutaneous irritation while maintaining the efficacy. In this novel formulation, tretinoin is entrapped in porous polymeric microspheres that serve as a reservoir and deliver the drug in a controlled manner over a longer period, and thus, reducing irritation. Moreover, the microsphere formulation offers an enhanced protection against tretinoin photo-degradation (Citation26,Citation27). The present phase 3 study compared the efficacy and safety of a gel-based tretinoin (microsphere) 0.04% and clindamycin 1% combination versus tretinoin 0.025% gel and clindamycin 1% gel monotherapies over 12 weeks for the treatment of acne vulgaris.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients aged ≥12 years with a clinical diagnosis of facial acne (inflammatory lesion count [papules + pustules] count between >20 to <50; non-inflammatory lesion count [open + closed comedones] between >20 to <100, and nodules [inflammatory lesion ≥5 mm in diameter] ≤ 2) and Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 (moderate) or 4 (severe) were included. Sexually active women of child-bearing potential who had a negative urine pregnancy test at baseline visit and who had agreed to use adequate birth control during the study were permitted. Patients with a known allergy or sensitivity to study drug, or who were concomitantly using any potentially irritating over-the-counter products that contained benzoyl peroxide, α-hydroxy acids, salicylic acid, retinol or glycolic acids, or who required concurrent use of topical (antimicrobials, anti-acne drugs, anti-inflammatory agents, corticosteroids, retinoids) or systemic (corticosteroids, antimicrobials, retinoids) medication and not willing to undergo the specified washout period were excluded. Patients with any other dermatological conditions of face, or with a history of other clinically significant medical disorders within last 6 months of study enrollment were excluded. Patients with facial beard or mustache that could interfere with the study assessments were excluded.

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles that originate in the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable regulatory requirements. The study was compliant with the protocol. Written informed consent with audio-video recording was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the study. This study is registered with ctri.nic.in (CTRI/2014/08/004830).

Study design and treatment

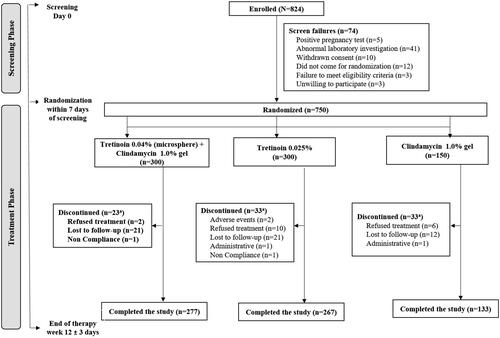

This was a multicenter, randomized, phase 3, three arm, double-blind, active controlled, parallel assignment study of 12 weeks conducted in patients with moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris from 31 centers across India. Eligible patients were randomly assigned (2:2:1) to fixed dose combination of tretinoin 0.04% (microsphere) plus clindamycin 1.0% gel, tretinoin 0.025% gel or clindamycin 1.0% gel to assess the efficacy and safety of tretinoin + clindamycin in comparison to either agents as monotherapies (). Randomization was performed using random allocation software. Enrollment was competitive enrollment and was closed once the target number was reached. After the specified washout periods (2 weeks: for topical antimicrobials and other topical anti-acne drugs; 4 weeks: for anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids; and 6 months: for systemic retinoids), eligible patients underwent a baseline medical history and physical examination including assessment of acne lesions, ISGA score and photographic measures. The duration of treatment was 12 weeks for all treatment groups and each patient reported to the center after 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment for efficacy and safety assessments.

Patients in all treatment groups were instructed to apply one fingertip of assigned study medication over the facial acne lesions once daily at bedtime for 12 weeks. Patients were advised to wash their face with a mild soap and warm water and pat the skin dry before application of study medication. Hands were to be washed thoroughly before and after applying the medication. Patients were cautioned not to apply the medication to the eyes, mouth, angles of the nose, or mucous membranes. The use of sunscreen was recommended to avoid risk of photosensitivity and sunburn, and patients were advised to avoid excessive exposure to sunlight, sunlamp, ultraviolet light, and other medicines that may increase sensitivity to sunlight. Topical emollient creams were allowed during the study period to keep the skin moist.

Study endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was mean percent change from baseline to week 12 in acne lesion count (inflammatory, non-inflammatory and total lesion count). The secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients rated ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ and who had ≥2 grades of improvement from baseline to week 12 in ISGA score. Also, physician’s global evaluation of efficacy score was determined at week 12 (or early termination visit), wherein the efficacy of the treatment was evaluated by the investigator and classified as ‘Excellent’, ‘Good’, ‘No change’, ‘Poor’ and ‘Worse’.

Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events (AEs) and laboratory evaluations. Hematological and biochemical laboratory evaluations were done at baseline and at week 12. Local tolerability assessments were performed by the physician and the patient (documented in the patient’s diary). During each visit, physician evaluated the patient for local tolerability in terms of erythema and scaling (grade 0 = none and grade 3 = severe). Patients were asked to record their skin reactions (itching, burning, and stinging) in the diary, every day during the study period (grade 0 = none and grade 3 = severe).

Statistical analysis

Based on previous data (Citation20), a sample size of 625 patients (250 in tretinoin + clindamycin group, 250 in tretinoin group and 125 in clindamycin group), excluding drop-outs, was considered sufficient to demonstrate superiority of tretinoin + clindamycin with a superiority margin of 5%, a significance level of 5% and a power of 80% to detect a statistically significant difference between tretinoin + clindamycin group versus either tretinoin or clindamycin monotherapy group. Assuming a drop-out rate of 17%, a total of 750 patients (tretinoin + clindamycin: tretinoin: clindamycin, 300:300:150) were to be randomized. Statistical testing was performed at 0.05 level using two-tailed tests. No interim analysis was planned in this study.

The primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population that included all patients who were randomized into the study irrespective of their eligibility status, completion status and protocol adherence. The primary and secondary endpoints were also analyzed in the modified ITT (mITT) population, including all patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one post-baseline evaluation visit. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with mean baseline as a covariate and t-test was used to assess the clinical superiority of fixed-dose combination of tretinoin 0.04% and clindamycin 1% versus monotherapies. Superiority of the combination over monotherapies was considered to be demonstrated if there was a statistically significant difference between treatments in the primary efficacy endpoint for two of the three types of lesions evaluated. Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method was used to carry forward the missing entries as part of data imputation methods. The safety parameters were also analyzed in ITT population. All key analyses were performed primarily using licensed version of Stata 13.0 for Windows.

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

Between October 02, 2014, and February 11, 2015, a total of 824 patients were assessed for eligibility, of which 750 patients were randomized to tretinoin + clindamycin group (n = 300) or comparator tretinoin group (n = 300) or clindamycin group (n = 150) and were included in the analysis (). The patients included 448 men and 302 women with a mean age of 21.2 years (range: 12–48 years). Of 750 patients in ITT population, 677 (90.27%) completed the study; the primary reason for discontinuation was lost to follow-up (n = 54).

The baseline demographic characteristics and facial acne lesions status were comparable between the treatment groups (). The mean ± SD duration of acne was 14.3 ± 19.12 months; the shortest being 15 days and the longest was 180 months.

Table 1. Patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics by treatment groups (ITT population).

Efficacy

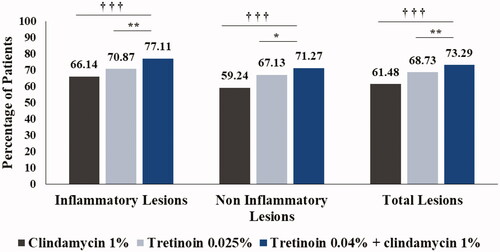

The primary and secondary efficacy outcomes are summarized in . In patients treated with tretinoin + clindamycin, the mean baseline inflammatory lesion count was 29.42 that reduced to 6.88 after 12 weeks; while the mean inflammatory lesion count of 29.93 reduced to 8.87 for tretinoin group, and 29.83 reduced to 10.28 for clindamycin group. For tretinoin + clindamycin treated patients, the mean baseline non-inflammatory lesion count was 38.28 that reduced to 11.62 after 12 weeks; while the mean non-inflammatory lesion count was reduced from 39.01 to 12.64 in tretinoin group, and from 38.38 to 16.97 in clindamycin group. For tretinoin + clindamycin treated patients, the mean baseline total acne lesion count was 67.70 that reduced to 18.50 after 12 weeks; while the mean total acne lesion count of 68.94 reduced to 21.50 in tretinoin group, and that for clindamycin group reduced from 68.21 to 27.25. Mean percentage change in inflammatory, non-inflammatory and total acne lesion counts from baseline to week 12 in tretinoin + clindamycin group was significantly higher (77.11%, 71.27% and 73.29%, respectively) when compared to tretinoin group (70.87% [p = .007], 67.14% [p = .022], 68.73% [p = .009], respectively) and clindamycin group (66.14%, 59.24%, 61.46%, respectively; p = .000 for all comparisons) ( and ). Overall, patients treated with tretinoin + clindamycin combination demonstrated a significant improvement in all three types of acne lesions over 12 weeks of treatment.

Figure 2. Comparison of mean percentage change in inflammatory, non-inflammatory and total lesion counts between treatment groups (ITT analysis set). †††p < .001 combination vs. clindamycin monotherapy; *p < .05, **p < .01 combination vs. tretinoin monotherapy. ITT: intent-to-treat.

Table 2. Primary and secondary efficacy endpoints (ITT population).

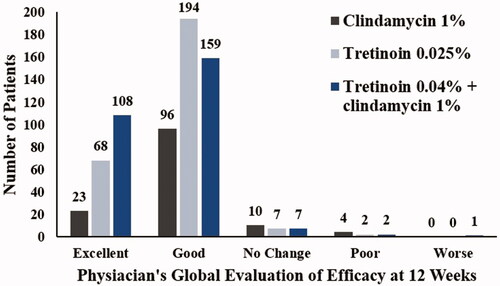

At baseline, all patients had ISGA scores of 3 or 4, which improved (decreased to 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) at week 12 in a significantly greater proportion of patients in tretinoin + clindamycin group (41% [n = 123]) when compared with patients in tretinoin group (31.67%, n = 95; p = .017) and clindamycin group (27.33%, n = 41; p = .005) (). The proportion of patients rated ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ and had achieved ≥2 grade improvement in ISGA score from baseline to week 12 was 45.67% in tretinoin + clindamycin group, which was significantly higher when compared with tretinoin group (36.00%; p = .016) and clindamycin group (28.67%, p = .001). Based on physician’s global evaluation of efficacy scores, the study treatment was considered excellent in 199 (29.22%) patients, of which 108 (38.99%) patients were in tretinoin + clindamycin group, 68 (25.09%) patients in tretinoin group and 23 (17.29%) patients in clindamycin group ( and ).

Figure 3. Comparison of physician’s global evaluation of efficacy (ITT analysis set). ITT: intent-to-treat.

The primary and secondary outcomes analyzed in the mITT population showed a similar trend as in the ITT population, with patients in the tretinoin + clindamycin group achieving significantly greater reduction in both inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions and lower ISGA scores when compared to either monotherapies (Supplementary Table SI).

Safety

Overall, 20 AEs were reported (6 in tretinoin + clindamycin, 11 in tretinoin, and 3 in clindamycin group); skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (n = 8) being the most common (). Of the 20 AEs, 19 (95%) were mild-moderate and only one severe AE was reported in the tretinoin group. Total 3 AEs were considered to be study drug-related (erythema [n = 2] and irritant dermatitis [n = 1]), all in the tretinoin group. No deaths or serious adverse events were reported during the study. Total three events of abnormal laboratory findings were reported; increased blood glucose (n = 1 in each tretinoin and clindamycin monotherapy groups) and increased bilirubin levels (n = 1 in clindamycin group), but were clinically not significant. In tretinoin + clindamycin group, no patient discontinued the treatment due to AEs, whereas in tretinoin group, 2/300 (0.67%) patients discontinued due to excessive irritation (n = 1) and increase in acne lesion counts (n = 1). The most common AEs in tretinoin + clindamycin group were pyrexia in 3/300 (1%) patients (vs 2/300 [0.67%] patients in tretinoin group; none in clindamycin group), eczema asteatotic in 1/300 (0.33%) patients (vs none in either tretinoin or clindamycin monotherapies), constipation in 1/300 (0.33%) patients (vs none in either tretinoin or clindamycin monotherapies) and increase in acne in 1/300 (0.33%) patients (vs 1/300 [0.33%] patients in tretinoin group; none in clindamycin group). In addition, other AEs reported in this study included gastroesophageal reflux disorder (n = 1), upper respiratory tract infection (n = 1), dermatitis (n = 2), facial swelling (n = 1), erythema (n = 2) in tretinoin monotherapy and urinary tract infection (n = 1) in clindamycin monotherapy; none of these AEs were observed in combination therapy group. Of the 6 AEs reported in tretinoin + clindamycin group, five AEs (pyrexia: n = 3, eczema asteatotic: n = 1, constipation: n = 1) were resolved without sequelae, following the administration of concomitant medication. One event of increase in acne was not resolved and monitored throughout the study duration.

Table 3. Summary of adverse events.

Local tolerability assessment showed that all the three study treatments were generally tolerated by patients. Itching and erythema were the most common events reported. As per the tolerability assessment at week 2, itching was reported in 35.08%, erythema in 32.46%, scaling in 29.83%, burning in 28.45% and stinging in 10.77% patients. These events showed a progressive decline in incidence as well as severity over the course of treatment. At week 12, erythema was observed in 15.81% patients in tretinoin group vs 10.11% patients in tretinoin + clindamycin group; while burning was observed in 13.60% patients in tretinoin group vs 8.30% patients in tretinoin + clindamycin group.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a novel gel formulation containing tretinoin 0.04% and clindamycin 1% using a controlled release microsphere delivery system. Although the efficacy of tretinoin is well established, adverse events related to skin irritation in the current standard treatment regimen (tretinoin 0.025% gel) has been a concern. The microsphere formulation facilitates controlled release of the drug; thereby, reducing the possibility of irritation and permitting the use of higher concentration of the drug for improved efficacy.

The combination of tretinoin (microsphere) 0.04% and clindamycin 1% gel used in this study was found to be an effective treatment option that targets both inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions. Treatment with combined tretinoin and clindamycin was significantly superior to tretinoin or clindamycin alone in the reduction of all types of acne lesions (inflammatory, non-inflammatory and total). A pooled analysis from three randomized phase 3 studies demonstrated that clindamycin and tretinoin combination gel was significantly (all p < .01) more effective than either of the monotherapies in terms of median percentage change from baseline to week 12 in alleviating different types of lesions (51.6–65.2%) in patients with mild to severe acne (Citation28). The mean percent reduction in acne lesions was higher for the combination group (71.3–77.1%) in this study than those reported in previous clinical studies with clindamycin and tretinoin combination (45.2–65.2%) (Citation17,Citation28). The superior efficacy noted in this study in terms of reduction in acne lesion counts could be attributed to the microsphere delivery system that might have enhanced penetration and retention of tretinoin at the lesion site.

Based on the ISGA score, a significant number of patients were confirmed as ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ from lesions at week 12 when compared with treatment with clindamycin or tretinoin alone, and these results were consistent with the results obtained in another study with combination of clindamycin and tretinoin (Citation17). At the end of treatment, only five patients had grade 4 ISGA score (vs 38 patients at baseline) and nearly half of the patients (46%) achieved ≥2 grade improvements in the combination group. Based on physician’s assessment, treatment was considered ‘excellent’ in a greater number of patients in the combination group (38.9%) as compared with monotherapy with tretinoin (25.1%) or clindamycin (17.3%).

Topical retinoids are often associated with varying degrees of cutaneous irritation within the first few weeks of treatment of acne vulgaris (Citation29,Citation30). In this study, clindamycin and tretinoin combination treatment was generally tolerable, as supported by local tolerability assessment data. Further, despite the higher concentration of tretinoin in the combination treatment, a trend toward progressive decline in cutaneous irritation was observed over the course of the treatment. These results may have occurred due to the use of microsphere technology, which allows use of higher concentration of tretinoin (0.04%) without increasing the risk of adverse skin reactions.

No new safety concerns or clinically significant changes in laboratory parameters was observed with the combination therapy when compared with either monotherapies. There were no discontinuations in the combined tretinoin and clindamycin group, whereas in tretinoin group, two patients discontinued the treatment due to AEs.

The findings of the present study support the previously reported studies with combination of tretinoin and clindamycin in acne, where combination therapy was found to be more effective and superior to individual agents but with similar safety and tolerability profile as that of tretinoin (Citation16,Citation17,Citation20). Furthermore, among patients treated with the combination therapy, discontinuation rates due to AEs were noticeably less when compared to other studies (Citation17,Citation20).

This phase 3 study was executed per protocol plan with determined sample size of 750 (patients enrolled). Minor protocol deviations were observed in the study; the most common reason being the study visit out of window period of 4–7 days.

The clinical efficacy and safety results obtained in this study suggest that the combination therapy with tretinoin 0.04% microspheres and clindamycin 1% gel can effectively clear both inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions, and has good tolerability in patients with moderate-to-severe acne.

Conclusion

Taken together, these findings suggest that the novel microsphere technology allows high concentration of tretinoin to be delivered at the acne site in a controlled manner for a longer duration and thus reducing irritation. The discontinuation rates can be a critical factor for patients’ adherence to treatment amongst available tretinoin and clindamycin combinations in Indian scenario, thus this controlled-release, once-daily, gel-based formulation of tretinoin and clindamycin could be considered as a potential option to improve patients’ compliance and overall therapeutic outcomes.

Author contributions

S.M., R.M., A.M., and S.N.C. contributed to conceptualization and designing of the study and had primary roles in data analysis and interpretation. SD, T.K.S., C.N., G.R., and P.P.V. were investigators who conducted the study and collected data. The complete list of investigators is provided in supplementary material. All authors contributed to the data interpretation for the results.

All authors met ICMJE criteria and all those who fulfilled those criteria are listed as authors. All authors had access to the study data, provided direction and comments on the manuscript, approved the final version for submission and made the final decision about where to publish these data.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (210 KB)Acknowledgements

Akshada Deshpande, PhD and Jyothi Ramanathan, PhD (both from SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd., India) provided writing assistance for this manuscript. The authors thank the study participants without whom this study would not have been accomplished, and the investigators:- Dr. A. Gugle, Dr. B. J. Shah, Dr. C. B. Mhaske, Dr. D. V. S. Pratap, Dr. G. Kiran, Dr. G. Prasad, Dr. H. R. Yogeesh, Dr. H. S. Chopade, Dr. H. V. Nataraja, Dr. J. Betkerur, Dr. J. Martis, Dr. M. Kuruvila, Dr. M. Parekh, Dr. M. Philip, Dr. N. Khanna, Dr. N. Sarma, Dr. P. Padmaja, Dr. P. Shukla, Dr. R. Agarwal, Dr. R. Dhurat, Dr. R. P. Singh, Dr. R. Rathod, Dr. R. Shah, Dr. S. C. Bharija, Dr. S. Sengupta, Dr. Y. S. Marfatia, for their contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

S.M., R.M., A.M., and S.N.C. are employees of Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd. and may hold company stock. SD, T.K.S., C.N., G.R., and P.P.V. received grants from Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd. for the conduct of this study. The material presented in this paper reflects authors own personal views and should not be interpreted as being representative of the views of their employers or institutions.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2020.1730581)

Additional information

Funding

References

- Burton J, Cunliffe W, Stafford I, et al. The prevalence of acne vulgaris in adolescence. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85(2):119–126.

- Tan JK, Bhate K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172 (Suppl 1):3–12.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Psychiatric and psychological co-morbidity in patients with dermatologic disorders: epidemiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(12):833–842.

- Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet (London, England). 2012;379(9813):361–372.

- Kubba R, Bajaj A, Thappa D, et al. Acne in India: Guidelines for management-Introduction. Indian J Dermatol Venereol and Leprol. 2009;75(S1):1–2.

- Al‐Ameer AM, Al‐Akloby OM. Demographic features and seasonal variations in patients with acne vulgaris in Saudi Arabia: a hospital‐based study. Intl J Dermatol. 2002;41(12):870–871.

- Tan HH, Tan A, Barkham T, et al. Community‐based study of acne vulgaris in adolescents in Singapore. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(3):547–551.

- Adityan B, Thappa DM. Profile of acne vulgaris-A hospital-based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(3):272.

- Pandey S. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 1983;28(3):109–110.

- Nast A, Rosumeck S, Erdmann R, et al. Methods report on the development of the European evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of acne – update 2016. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(8):e1–e28.

- Nast A, Dreno B, Bettoli V, et al. European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(Suppl 1):1–29.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1):S1–S37.

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1–S50.

- Abdel-Naser MB, Zouboulis CC. Clindamycin phosphate/tretinoin gel formulation in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9(16):2931–2937.

- Leyden JJ. A review of the use of combination therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(3):S200–S210.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(3):318–326.

- Leyden JJ, Krochmal L, Yaroshinsky A. Two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of 2219 subjects to compare the combination clindamycin/tretinoin hydrogel with each agent alone and vehicle for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):73–81.

- Richter J, Bousema M, Boulle KD, et al. Efficacy of a fixed clindamycin phosphate 1.2%, tretinoin 0.025% gel formulation (Velac) in the topical control of facial acne lesions. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;9(2):81–90.

- Rietschel RL, Duncan SH. Clindamycin phosphate used in combination with tretinoin in the treatment of acne. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22(1):41–43.

- Schlessinger J, Menter A, Gold M, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy studies of a novel formulation combining 1.2% clindamycin phosphate and 0.025% tretinoin for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(6):607–615.

- Yaroshinsky A, Leyden J. The safety and efficacy of clindamycin (1% as clindamycin phosphate and tretinoin (0.025%)] for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a combined analysis of results from six controlled safety and efficacy trials conducted in Europe. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(3):P23.

- Galvin S, Gilbert R, Baker M, et al. Comparative tolerance of adapalene 0.1% gel and six different tretinoin formulations. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:34–40.

- Luckya AW, Cullenb SI, Jarratt MT, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of two 0.025% tretinoin gels: results from a multicenter, double-blind, parallel study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(4):S17–S23.

- Quigley JW, Bucks DA. Reduced skin irritation with tretinoin containing polyolprepolymer-2, a new topical tretinoin delivery system: a summary of preclinical and clinical investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(4):S5–S10.

- Skov MJ, Quigley JW, Bucks DA. Topical delivery system for tretinoin: research and clinical implications. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86(10):1138–1143.

- Nighland M, Yusuf M, Wisniewski S, et al. The effect of simulated solar UV irradiation on tretinoin in tretinoin gel microsphere 0.1% and tretinoin gel 0.025%. Cutis. 2006;77(5):313–316.

- Nyirady J, Lucas C, Yusuf M, et al. The stability of tretinoin in tretinoin gel microsphere 0.1%. Cutis. 2002;70(5):295–298.

- Dreno B, Bettoli V, Ochsendorf F, et al. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025% formulation for the treatment of acne vulgaris: pooled analysis of data from three randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, phase III studies. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24(2):201–209.

- Culp L, Moradi Tuchayi S, Alinia H, et al. Tolerability of topical retinoids: are there clinically meaningful differences among topical retinoids? J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19(6):530–538.

- Thielitz A, Gollnick H. Topical retinoids in acne vulgaris: update on efficacy and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(6):369–381.