Abstract

This article examines the overlooked phenomenon of how black British grime music artists intentionally and selectively remix Japanese pop cultural artifacts to carve out a hybrid cultural space that gives voice to their urban realities and articulates counterhegemonic black subjectivities. From the early 2000s, at the same time as state-centered discourses of ‘Cool Japan’ emerged to explain the global rise of Japanese pop culture, grime artists were already on their own terms sampling Japanese video games and anime to articulate emergent feelings of ‘coldness’, which reflects their sense of alienation on the margins of British society. The author introduces ‘Cold Japan’ as the other Cool Japan, and a way of understanding this fundamentally intertwined mode of cultural hybridity and being that forms the essence of black Britain’s grime. This article uses the cyborg figure to disclose how grime artists transform Cold Japan into a site of countercultural resistance to subvert their oppression by self-generating and embodying transgressive posthuman identities. Examining how selected ‘cold’ Japanese pop cultural elements and technologies entangle with urban black life and identity formation in 21st century Britain, the article contributes to discussions on the impact of transnational flows of Japanese pop culture and cultural hybridization.

Before grime, never had a voice. (Jme, 96 of My Life)

You hear people talking about the grime sound coming from another planet? Well, that’s because it does. (Wiley, Eskiboy)

Introduction

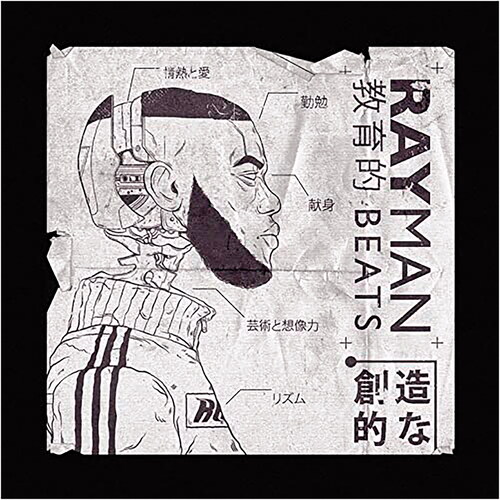

Measuring the physical attributes of human skulls, in his 1839 book Crania Americana, phrenologist Samuel George Morton famously claimed similarities between Africans and primates as scientific proof of black racial inferiority. In contrast to Morton’s artistic representation of a sub-human negro profile, the cover artwork for a song by grime artist Blay Vision produced by Raymanbeats, pictures a manga-inspired profile of a black male cyborg; a hybrid of machine and organism (see ). This technologically enhanced ‘negro profile’ from the future is dissected to reveal multiple intellectual traits that are curiously rendered only in Japanese characters.Footnote1 Emerging from the urban streets of London, the hybridized grime cyborg becomes a desired form of posthuman embodiment, which subverts ideologies of race that thrusts the black body backwards into primitiveness or the silent margins. This article explores how through remodeling specific elements from Japanese pop cultural content and technologies, which became entangled with the lives and bodies of young black Britons, grime artists carve out a new hybrid cultural space that gives voice to black urban life in early 21st century Britain and generates empowered cyborgian identities that articulate counterhegemonic black subjectivities.

Developing in the early 2000s out of council estates, school playgrounds and pirate radio stations in London, grime traces its roots to an eclectic mix of genres including, but not limited to, dancehall; jungle; garage; hip hop; and Jamaican sound clash culture. The pioneers and practitioners of grime who will be the focus of this study are predominantly young, male, second to fourth generation black British, with either Caribbean or West African heritage. As such, grime is primarily considered an African diaspora musical form. Thrashing along at a blistering 140 beats per minute, its disjointed and emotive electronic sound provides a frenetic backdrop for performers to rapidly and playfully deliver lyrics that channel the frustrations of being poor, black and marginalized in urban London. As explained by Richard Bramwell (Citation2011, 255), the word ‘grime’ and its association with filth and the undesirable grittiness of inner-city life, is transformed by artists into a desirable aesthetic quality to be pursued in their creative practice as demonstrated by the appreciative term ‘grimy’. In particular, the grime pioneers wanted to generate a sound and deliver a lyrical flow that was distinct from American rap styles in order to speak to their unique circumstances and represent their local identities ‘in their own voice’ (Wiley Citation2017, 93). In other words, it was also a space for identity formation and creating a shared culture and sense of belonging across ethnic backgrounds among black British youth in working-class urban areas (see Bramwell and Butterworth Citation2019). The soundscapes are described as, and self-applauded for evoking feelings of ‘coldness’ to articulate black urban life on the margins in Britain. First expressed by the self-proclaimed godfather of grime, Wiley (aka Eskiboy), who produced the ‘Eskibeat’ sound, a collection of tracks in the early 2000s replete with icy themes, such as Eskimo (2002), Snowflake (Tokyo) (2002), Ice Pole (2002) and Igloo (2003), ‘coldness’ describes the experience of radical alienation; a switching off from the dominant society in Britain characterized by hierarchies of race and class, and a general discontent at the state of the world (Reynolds Citation2011, 381–382; Wiley Citation2017, 255; Adams Citation2019, 440; Hancox Citation2018, 57–80). Yet what has been missing from this narrative of grime’s countercultural expression of coldness is the centrality of Japanese pop cultural artifacts.

As children of the 1980s and 1990s, the grime pioneers grew up on a diet of Japanese pop culture that was ubiquitous in the form of home entertainment systems, television anime series, portable game devices, and arcade machines in frequented spaces such as Afro-Caribbean barbers and local fast food takeaway shops (Boakye Citation2018, 166). It made up a significant part of the world they lived in and interacted with. Japanese pop cultural artifacts became to grime artists what Henry Jenkins (Citation2020, 2) describes as ‘stuff – that is, the accumulated things that constitute…familiar surroundings’.

Especially from the early 2000s, the wider international success of Japanese pop culture and media mix franchisesFootnote2, became associated with state-centered soft power (Nye Citation1990) discourses of ‘Cool Japan’, which focus on Japan’s capacity to influence foreign nations and publics through cultural exports despite facing a ‘Lost Decades’Footnote3 of economic stagnation, the rise of its East Asian neighbors, and long-term structural challenges at home (Yano Citation2013, 5). This essay reveals how during this very same moment of Japan’s expanding global cultural presence, grime artists were on their own terms consuming and remodeling Japanese pop cultural artifacts to better comprehend and give voice to their latent feelings of coldness. Grime musicians remix these Japanese pop cultural artifacts in a ‘transmedia’ manner (Jenkins Citation2006), crisscrossing and amalgamating narrative and audio-visual elements from multiple media sources, such as video games, anime and manga. Jenkins (Citation2006) explains that ‘transmedia storytelling is the art of world making’ (21) with each new text making a contribution to the whole (95–96). In this way, grime artists take on the role of what Jenkins describes as ‘hunters and gatherers’ (21), to chase down the pieces that make up their world of coldness across media channels. This constructed cold world becomes a liminal space of cultural hybridity where African diaspora musical traditions as interpreted by black British youth collide and merge with Japanese pop cultural content, generating something totally new – a sound ‘from another planet’ in the words of Wiley (Citation2017, 79). This article introduces ‘Cold Japan’ as the other ‘Cool Japan’, and a way of understanding the interstices between the lived experiences of grime artists as alienated black working-class youth on the edges of British society, and the Japanese pop cultural content that they selectively remix to articulate their subaltern voice of coldness through grime.

Grime artists are not only drawn to the familiarity of Japanese pop cultural artifacts as the ‘stuff’ of their surroundings, which became fused with their lives and feelings of coldness. Japanese pop cultural content also operates as ‘fantasy-ware: goods that inspire an imaginary space at once foreign and familiar’, as Anne Allison (Citation2006, 277) puts it. The attraction, therefore, also lies in the very imagined spatial and temporal distance of ‘Japan’ that can, to borrow the words of Robin Kelley (Citation2003, 11), take them ‘to another place…a different way of seeing, perhaps a different way of feeling’, where, as Deborah Gould would suggest, ‘squelched desires’ or previously unimaginable new ones can enter into the realm of existence and articulation (quoted in Fawaz Citation2016, 29). Identifying this impulse towards the other-worldly, music journalist Dan Hancox (Citation2018, 70–77) points to the early 2000s sub-genre of ‘sino-grime’, which intentionally utilized ‘oriental’ sounding instruments, such as the shamisen or guzheng and samples from kung fu movies. In an interview discussing his landmark album, Boy in Da Corner (2003), Dizzee Rascal explains that he uses the shamisen because the sound was ‘about as out there as they come’ and didn’t remind him of anything else (Sound on Sound, January, 2004). Growing up during the 1980s and early 1990s, an era of an expected ever increasing Japanese economic and technological dominance, meant that the grime artists-to-be were regularly exposed to popular images of Japan as what William Gibson calls, the ‘global imagination’s default setting for the future’ (The Observer, April 1, 2001). As introduced by David Morley and Kevin Robins (1995, 169–170), Western fears of a Japanese dominated technological future were characterized by techno-Orientalist discourses, which present Japan as an ‘alienated and dystopian image of capitalist progress’ where the culture ‘is cold, impersonal and machine-like, an authoritarian culture lacking emotional connection to the rest of the world’. Delineating how techno-Orientalist images of cold dystopian futures resonate with and permeate grime’s hybrid space of Cold Japan, I argue that artists embrace the radical imaginative and transgressive possibilities of an alternate postmodern time-space and sonic palette that displaces the sound waves of Western modernity. Grime artists leverage a ‘DIY ethos’ (Luvaas Citation2012) to disassemble and remix selected Japanese pop cultural artifacts and attach these components as prosthetic enhancements to build their creative practice and identities. They become grime ‘cyborgs’ made in Cold Japan, ‘a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction’ (Haraway Citation1991, 149). The cyborg illuminates grime’s fundamentally intertwined mode of cultural hybridity. Performances of cold cyborg embodiment through grime music becomes a self-emancipatory creative expression to ‘move out of one’s place’ (hooks Citation1989, 15) and enter a different world, a new way of being where they can disrupt the racial and class oppression of British society characterized by socio-economic inequality, perceptions of unjust policing and hegemonic representations of blackness. The coldness of subalternity is subverted and transformed into an invigorating source of pleasure and power, because as Morley and Robins (Citation1995, 170) suggest of an imagined postmodern ‘Japanised’ future, maybe it is the mutated aliens and cold unfeeling cyborgs, who are ‘better adapted to survive in the future’. Becoming the cold hybrid grime cyborg expresses the artists’ desires for an alternative future beyond marginalization. As rapped by the grime pioneer Jme (Citation2006c), ‘Cause I know that I need the future/but I want the future to need me’.

That Cold Japan emerges as a hybridized cultural site for grime artists to locate and enunciate ideas of black liberation is striking. Extending back to the nineteenth century from the time of Japan’s opening and rise during the Meiji period, through the African American press and the writings of W.E.B Du Bois among other black intellectuals at the turn of the twentieth century, Japan has long played a symbolic role in the black imagination as a source of inspiration and challenger to Western hierarchies of civilization and race (see Kearney Citation1998; Gallicchio Citation2000; Mullen Citation2004; Horne Citation2018; Doan Citation2019). Similarly, throughout the twentieth century, broader Afro-Asian affinities and shared agendas have materialized. Most notably the 1955 Bandung conference, Yellow Peril and Black Power activism in 1960s America, and the popularity of 1970s kung fu movies among black audiences, which in the 1990s influenced the lyrics and personas of African American rap groups like the Wu Tang Clan (see Prashad Citation2002; Ho and Mullen Citation2008; RZA Citation2009). Grime’s Cold Japan phenomenon draws from these deep-rooted cultural, intellectual and political urges towards Afro-Asian solidarity and black transnationalist discourses of Afro-Orientalism (Mullen Citation2004), which look outside of a dominant white Western culture to ‘darker’ extraterritorial and countercultural time-spaces to engage in a global struggle against racial and class exploitation. However, such instances of non-state level transnational linkages often remain hidden as scholarly discussions of black-Japanese interactions frequently center on issues of race and (mis)representations of the Other (Bridges and Cornyetz Citation2015, 4), leading to perceptions of an ‘unbreachable rift between Blacks and Asians’ (Russell Citation2012, 44; also see Ho Citation2021, 154). Especially in the case of Britain, as British people of African descent have historically been excluded from serving as the outward face of the nation and their transnational mobility or cultural traffic is only imagined within the bounds of the ‘Black Atlantic’Footnote4 (Gilroy Citation1993), it is believed that black British-Japanese interactions are non-existent, and so has yet to feature in examinations of Anglo-Japanese encounters. Most previous academic studies have unearthed examples of black-Japanese connectivity by exploring cultural flows from the opposite direction to consider how Japanese populations have appropriated essentialized representations of blackness through African diaspora cultural productions, such as jazz, hip hop, reggae and fashion, to form and assert their own identities (see Condry Citation2006; Sterling Citation2010; Bridges and Cornyetz Citation2015). Music scholar Ken McLeod’s (Citation2013) survey of techno-Orientalism in contemporary hip hop critically shifts the focus to identify how African American artists such as RZA, Kanye West and Nicki Minaj incorporate Japanese aesthetics into their music as strategies of hybridity. Arising from such impulses and collaborations, for example, is the 2007 ‘Afro Samurai’ television anime series, which was adapted from the manga by Okazaki Takashi and included two original hip hop soundtracks by RZA. Thorsten Botz-Bornstein (Citation2011) similarly points towards the rise of an ‘Afro-Japanese’ cultural convergence by highlighting the global attractiveness of African American hip hop ‘cool’ and Japanese ‘kawaii’ cute aesthetics that form ‘cool-kawaii’ cultural hybrids, such as BAPE (A Bathing Ape), a Japanese fashion brand, which combines a hip hop streetwear style with kawaii designs. Such instances of increased mutual cultural borrowing and inspiration as part of the globalization of African American and Japanese popular cultural exports, prompts hybridization to enrich the aesthetic of the original and achieve that ‘next level of fashion’ (Botz-Bornstein Citation2011, 17) to further appeal to global audiences. All the while, ‘both Japanese popular culture and African American hip hop maintain their own discreet cultures’ (McLeod Citation2013, 272). A framework of cultural hybridity where the ‘Afro’ and the ‘Japanese’, so to speak, are distinct entities that co-exist. This article argues that the case of grime music that emerged in black Britain makes an important intervention into our understanding of processes of cultural hybridization and a growing body of research on Afro-Japanese or Afro-Asian connectivity, by demonstrating how grime has, from its inception, been ontologically dependent on its comprising parts and is thus necessarily hybrid. Phrased differently, grime music isn’t just incorporating a globally ‘hot’ and trendy Japanese pop culture or using these elements as aesthetic additions, it is these very elements fused with black British urban life that make up the essence of grime culture.

Local grime, global Japan?

Media discourse surrounding grime during the years of its growth in the early 2000s likened the genre to an American gangster rap that inevitably inspires crime and violence among unproductive and anti-social black youth in dilapidated urban spaces. Hancox (Citation2018, 149–164) describes how the genre has been noted for its hyper-localism and that ‘neighbourhood nationalism’ is considered as integral to its identity. Grime’s lyrics and themes are frequently centered on one’s block or postcode known as the ‘endz’, suggestive of the artists’ sense of alienation from a gentrifying and increasingly globally connected London, which they can only view from afar. With few opportunities for outward or upward mobility and increasingly hemmed into their local areas, grime’s sound, which is lo-fi, sub-bass heavy and made up of ‘icy cold synths’ (67), has thus been described as ‘claustrophobic’ (154) and reflective of bleak urban conditions, or as grime artist Jme (Citation2019) puts it, a life ‘trapped in the endz’.

Video game researcher Rob Gallagher (Citation2017) has contributed to understandings of grime by exploring the relationship between fighting games and grime’s iteration of clash culture. Rooted in African diaspora cultural traditions of wordplay competitions, such as the dozens, rap battles and Jamaican clash culture, lyrical ‘battles’ have shaped grime music. Centering his discussions on Capcom’s Street Fighter series, Gallagher delineates how grime artists playfully cite fighting game characters during songs and rap battles, as can be seen in D Double E’s Street Fighter Riddim (2010). Just like fighting game characters, through their lyrics they can deliver combos, warrior charge ad-libs and land special moves to finish off the opposing artist. To date, then, grime’s relationship with gaming has only been understood in terms of its evocation of playful weapons used for declaring authority and committing acts of symbolic violence towards competitor artists. Through this lens, grime artists as black youth are once again confined to the ‘iconic ghetto’Footnote5 repeating artistic performances of so-called internecine black-on-black violence. Such analyses inadvertently contribute to narratives that reinforce stereotypes of young black males being disproportionally associated with violent imagery, and grime as a form of rap music that is bound to parochial concerns. By overlooking a much broader process of cultural hybridization and the symbolic function of an imagined ‘Japan’ in envisioning alternative ways of being, these instances of citation become scattered and ultimately only appear as ‘hypermasculine brags’ and taunts through novel means (Gallagher Citation2017, 16). I argue that we cannot fully understand the countercultural expression of grime as a significant feature of black British life and youth identity formation in the 21st century apart from a transnationally formed hybrid space of Cold Japan.

There is a wealth of literature that explores the rise of Japan as a global cultural superpower centered on the growth and influence of Japanese pop culture, such as anime, video games, food, J-pop and toys in Western countries since the 1990s (see Napier Citation1998; Iwabuchi Citation2002; Allison Citation2006; Kelts Citation2006; Yano Citation2013; Alt Citation2020). Emboldened by Douglas McGray’s (Citation2002) assertions of ‘Japan’s Gross National Cool’ and in part inspired by New Labour’s ‘Cool Britannia’ campaign of the late 1990s (Valaskivi Citation2013, 491–492), Japanese government agencies adopted a ‘Cool Japan’ brand strategy from the early 2000s hoping to capitalize on the apparent international success of Japan’s creative industries for economic gains and soft power influence. In other words, the Japanese government were very much latecomers to the scene as a bottom-up popularity and perception of Japanese culture as ‘cool’ existed even before official state-sanctioned nation-branding narratives of ‘Cool Japan’ (Yano Citation2013, 257–260). This top-down vs bottom-up dynamic has implications for how we interpret the phenomenon of Japan as ‘cool’. As identified by Laura Miller (Citation2011, 98), a central conundrum of Cool Japan is the question of who gets to decide what constitutes ‘coolness’. While the Japanese government is engaged in a national inscription that emphasizes the ‘Japaneseness’ of targeted cultural exports and content, some scholars have conversely highlighted the quality of mukokuseki statelessness and odorlessness – that is without a national identity or ‘fragrance’ – in understanding the global popularity of Japanese anime and video games (see Napier Citation1998; Iwabuchi Citation2002). In other words, it is the very nation-lessness of Japanese pop culture that creates an anywhere space where anyone can project themselves. Mark McLelland (Citation2017, 6) observes, in today’s ‘remix’ world, producers and governments have little control over the way content is consumed, accessed and (re)interpreted. The idea of Cool Japan, therefore, is unstable and the meanings attached to it are constantly in flux and contested (Sugimoto Citation2014, 291). This study reveals how when the global flow of Japanese pop cultural goods, which are now associated with discourses of Japan ‘cool’, merged with the lives and bodies of urban black youth in Britain, they were remodeled to articulate emergent feelings of coldness. Grime’s ‘Cold Japan’ demonstrates the dynamic nature of the Cool Japan phenomenon as something that is continuously recontextualized by multiple populations, and in particular suggests the indispensable role of transnational flows of Japanese popular culture in identity formation and generating new hybridized cultural sites of resistance.

London’s streets of rage

Drawing on concerns of marginalization and the deprived material conditions of urban underclass communities, grime music emerged as a way for artists to give testimony to their perspectives of the realities of life on the ‘road’ or the ‘endz’. What hooks (Citation1989, 20) would call life ‘on the edge’, or a ‘part of the whole but outside the main body’, to describe a particular positionality and way of seeing that develops from living on the margins of society. These alternate realities exist outside of state-centered narratives of ‘Cool Britannia’ national pride, urban revitalization, and a post-racial society under a New Labour government at the turn of the twenty-first century. As grime pioneer Dizzee Rascal puts it in Graftin’ (2004), ‘I swear to you it ain’t all teacups, red telephone boxes and Buckingham Palace/I’m gonna show you it's gritty out here’ (quoted in Hancox 2018, 17). Grime displays a commitment to ‘realism’, explained by Imani Perry (Citation2004, 86–88) as the constant injunctions within rap music ‘to be real’ and ‘keep it real’. Artistic approaches within rap music forms to demonstrate realism and authenticity, such as staging music videos within the rapper’s milieu of urban inner-city locations surrounded by one’s crew (Rose Citation1994, 10) are replicated in grime music videos that utilize street corners and council estates as their setting (Adams Citation2019, 440). Grime especially emerged as a deliberate departure from the upbeat genre of garage music, which frequently incorporated female RnB vocals culminating in a sound that could spirit one away to memories of 1990s UK rave culture dance parties on sun-drenched islands overseas. In contrast, the grime aesthetic is one that is intentionally cold as a way of reflecting the darker realities of existing as poor, black and trapped in a dreary Britain with little opportunity for upward mobility. Wiley speaks at length about coldness in his book and media interviews (Hyperdub, October, 2003), noting how it describes the emotional dislocation and rage he and others feel towards society and their surroundings. ‘It’s a cold, dark sound because we came from a cold, dark place. These are inner-city London streets. It’s gritty’ (Wiley Citation2017, 79).

Grime artists frequently refer to the cold. Wiley (Citation2013) raps about being ‘Born in the Cold’. Jme (Citation2006a) asserts that his ‘Riddim is cold like a winter day’. Blay Vision (Citation2019) describes the urban experience on the ‘road’ as, ‘Cold fam everytin cold/life just filled with pain and woe’. Skepta (Citation2016) laments, ‘Nah, last year man lost a yute and my heart turned cold/dem man lost Lukey and my heart just froze’. Grime’s distinct manifestation of a commitment to realism and sonic articulation of the coldness of life in the endz as experienced by young black Britons, is generated through, and imagined in dialogue with Japanese pop cultural artifacts. To date, the transnational spread of Japanese pop culture since the 1990s and explanations of Japanese ‘cool’ have almost always been associated with warmer feelings and tones produced by the flow of ‘kawaii’ (Yano Citation2013), ‘fun-loving…playful’ (Sugimoto Citation2014, 293), and ‘healing’ or ‘soothing’ iyashikei (Allison Citation2006, 14) goods. What Christine Yano (Citation2013, 6) calls a process of ‘pink globalization’ represented by ‘Japanese Cute-Cool’ ambassadors, such as Hello Kitty. This is also true for hip hop culture with American artists such as Kanye West and Pharrell Williams choosing to integrate warm ‘kawaii’ Japanese elements into their aesthetic. Grime, however, reproduces a very subjective image of Japanese pop culture as artists remix video game and anime worlds that activate cold structures of feeling. As we will see, grime artists especially select grittier spaces that are characterized by struggle, such as fighting, adventure and cyberpunk futures, to narrate their own cold realities. For grime artists then, Japanese pop culture isn’t just cool, it is cold.

First released in 1991, Sega’s 2 D side-scrolling beat ‘em up game series Streets of Rage, is used as a recurring trope to describe the challenges and mental trauma that black youth face growing up on the streets of London, as cited by Skepta (Citation2012) in the song Castles: ‘It’s real life, no computer game, we’re living in the streets of rage’. The Streets of Rage game is set in a cyberpunk city that has been taken over by a crime syndicate that dominates the skylines via unreachable high-rise towers while the decaying streets below are lawless battlefields inhabited by corrupt police and nefarious criminals. The cyberpunk aesthetic first gained popularity during the 1980s out of a subgenre of science fiction represented by books such as William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), Ōtomo Katsuhiro’s 1982 manga series and the 1988 animated film adaption Akira, and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner movie (1982), which frequently utilize techno-Orientalist tropes and depict what writer Bruce Sterling describes as ‘high tech and low life’ futures (quoted in Henthorne Citation2011, 40). These visions of dystopian cyberpunk futures reflect how grime artists perceive present-day London as a cold environment of dislocation and hostility (Hancox Citation2018, 23). If the video game devices and other pop cultural content dependent on advanced technologies, which they were consuming from childhood are the ‘high tech’, then the streets of Britain’s inner-cities are the ‘low life’.

The Streets of Rage game begins with an opening scene that slowly pans across the metropolis’ night skyline while rolling text appears announcing the story of how a once peaceful city was suddenly hijacked and chaos ensued. The accompanying chiptune music by Yūzō Koshiro opens with a piercing synthesized melodic line that holds the listener in a state of suspense before the song drops with a late 1980s UK rave music inspired breakbeat to create a chilling atmosphere of urban disarray. ‘Press Start Button’ appears. The game has fully loaded. Mirroring this narrative progression, Skepta’s (Citation2016) Konnichiwa, the first song on his studio album of the same name, opens in a peaceful calm with the sound of chirping birds, flowing water, a shakuhachi flute and the sound of a katana sword being removed from its sheath. The introduction continues with a dark synth melody while Fifi Rong, a Chinese-British female vocalist driftingly repeats the line ‘Lookin for me? Konnichiwa’. The scene is rudely interrupted by a riotous noise of sirens, glass smashing, people shouting, and a thumping bassline. The prolonged 55 second introduction creates a feeling of uncertainty and disjunction as multiple spatialities and temporalities co-exist; is this just a game, or is this real life? In a book on the connection between sound technologies and black music cultures, Alexander G. Weheliye (Citation2005, 1) writes of the remarkable power of introductions, ‘the allurements that lurk in the crevices of sonic beginnings, those sonorous marks that launch new worlds’. The introduction to Konnichiwa thus operates to sonically load a new world for listeners just like a game would load a virtual world for players. Aptly named Konnichiwa, the song is a greeting to the soundscape of London’s ‘streets of rage’.

Similarly, the music video for Joe Grind and Jme’s (Citation2019) Boss visually transforms London into the ‘streets of rage’ that grime artists experience. After touching Super Nintendo gamepads and entering into a hallucinatory state, the duo are suddenly transported from a living room and dropped into a Streets of Rage inspired side-scrolling game. Just like the original game, they become 2 D pixelated characters that must battle their way through each level by defeating oncoming adversaries. The enemies are baton wielding white police officers and a final pig boss, fittingly named ‘constable swine’. The background scenes, uniform designs and black custodian helmets suggest that this is set in an imaginary London. Blurring the boundaries between fictional conflict with an oppressive police force as depicted in the video, with his own real-world experiences of police harassment, Jme raps, ‘Still getting violated by feds too/on streets it’s peak every week I see flashing red blue’. The fictional Streets of Rage game world is transposed onto their reality, and vice versa; the struggles of life in black urban London as comprehended by the artists are projected onto the virtual world. The real and virtual become entangled.

Jme’s (Citation2006b) song Final Boss, is a remix of a sample of the music from ‘The Doomsday Zone’ final boss level of Sega’s Sonic & Knuckles (1994). Sonic and Knuckles must avoid asteroids and oncoming missiles to defeat Dr. Robotnik in a time-limited outer space battle. The accompanying game music is discordant and hurried to enhance the tension and create a constant sense of panic as a reminder that you are against the clock. During the chorus of Jme’s song he has a robotic voice that sings the main melody of the game music, while in the verses he energetically raps about the dangers of the streets of London where there is a risk of police violence, gunshots and ‘nuff badman to beware of’, as though he is frantically trying to dodge a minefield just like Sonic in the final boss zone: ‘See I ain’t got time to tell you the nitty-gritty/about the danger in England’s capital city’. There are frequent high-pitched upward chromatic runs sampled from the game music that interject into the already busy sonic landscape creating a hazardous buzzing sound of chaos. He laments that society doesn’t care about the plight of the endz and their subaltern voice is ignored: ‘Blud, open your ears up, it’s like no one hears us’. Jme hybridizes the perils of London’s ‘streets of rage’, his vocal cords and lyrical flow with the speed of life of ‘The Doomsday Zone’ to portray in ‘sonic’ form the coldness, which cannot be communicated in words. He enjoins the listener to hear the ‘breaks’ (Eshun Citation1998, −001), the ruptures, the spaces that only lie inbetween.

Blay Vision (Citation2018) pursues a similar liminality in his track, Won’t Let Em, which is an audio-visual illustration of the precariousness of life in the endz. The music video is stripped of color to become grayscale and depicts the rapper performing in a black hoody outside of a housing block in North London. He raps about the dangers of getting involved in the ‘trap’ life and the potential for conflict in the hood. The song opens with stacked ascending and descending chromatic runs that escalate with a relentless energy throughout. A chiptune synth is used to generate the chromatism, and the dizzying digital beeps create a disorienting and menacing effect. It mirrors storytelling techniques found in video games, famously employed by the Pokémon game series composer, Masuda Junichi, who harnesses chromatic movements to create a sense of danger in battle scenes, underground caves and boss fights. Blay Vision’s voice is digitally enhanced during the chorus to give him a sonorous and monstrous resonance, as if he is the final boss.

Weaving and interlacing soundscapes drawn specifically from dark and ominous spaces within games through the streets of black London produces grime’s creative expression of coldness. Ruth Adams (Citation2019, 440) observes that grime has a strange and unique sound that seems to have been ‘recorded deep in a cave or under water’. To the extent that grime reproduces sounds designed to give this effect in Japanese games, underground lairs and caves are exactly where it has emanated from. The ‘griminess’ of everyday life in the endz is perceived to be captured in the absurd surreality and structures of feeling of the murky spaces within video games. Forming grime’s sonic tapestry, these spaces and sounds provide a new language to make sense of, and voice the cold universe that they inhabit. What once was inarticulable through existing structures and modes of expression – the coldness of black British urban life – finds its articulation through merging with and recombining these sonic fragments from Japanese pop cultural artifacts into something totally new. From its genesis, grime was always hybrid and inbetween. The dividing lines between urban black Britain and Cold Japan are blurred and eradicated as they melt into each other.

Fantasy worlds within Japanese manga and anime series similarly merge with life in the endz. For the front cover of his genre-crossing mixtape Secure the Bag 2 (2020), fusion rapper AJ Tracey is pictured transformed into a manga character wearing a schoolboy uniform. The image depicts AJ Tracey fleeing from a gigantic explosion and a metropolis in flames in the background while clutching onto a bag overflowing with yen in one hand and an assault rifle wielding schoolgirl in the other. The black and white illustration is an allusion to the destruction of Neo-Tokyo in the artwork of the manga series and animated film Akira. Set in a futuristic and post-apocalyptic Tokyo of 2019, Akira deals with dystopian cyberpunk themes of deracination, excessive control, government corruption, scientific experimentation on children, and competing gangs of youth roaming the streets (Napier Citation1998, 44). Confirming this connection, the opening line of Yumeko,Footnote6 the first song on the mixtape, is ‘Akira’ (AJ Tracey Citation2020a). Later in the song he raps, ‘Slide round your block and it’s frying/come to the trench where the bullets are flying’. Through lyrical allusions to anime narratives that center on struggle within dystopian environments and an album sleeve that shows a collapsing city up in flames he is inviting listeners to peer into life in the endz. Sitting above the track list on the flipside of the album artwork is the Japanese character for warrior (武). If present-day urban London is collapsed into the time-space of Akira’s post-apocalyptic Neo-Tokyo, a cyberpunk world where ‘sudden transformations in shadowy environs where daylight is extinguished in an instant, where playful schoolyard boys and girls become warriors’ (Kelts Citation2006, 40), then AJ Tracey is that young schoolboy-cum-warrior thrust into a sci-fi nightmare.

He names another track, Hikikomori (AJ Tracey Citation2020b), referring to the contemporary phenomenon where some Japanese youth choose to withdraw from society through varying levels of isolation and confinement. The song repeatedly mentions, ‘I wanna stay inside, I wanna stay…I know I’m safe…I’m tryna get back home’, while also expressing that he doesn’t ‘wanna go outside’ because ‘outside’s not cool…outside’s not fun’. The hikikomori condition is given a new meaning and significance as a reflection of the feelings of coldness and switching off from the world that is central to grime’s creative expression. In the song’s second verse he weaves in Naruto references. Arriving to the UK in the mid 2000s, the anime series follows the story of an orphan boy named Uzumaki Naruto who is shunned as an outcast by his village as they fear the dangerous Nine-Tailed Fox beast that was sealed within his body. Despite having experienced countless instances of pain and rejection during his childhood, Naruto is committed to improving his situation through training to become a powerful ninja so that he can turn the tables on his fate and take up a position as an admired village leader. Using word play that rapidly swings between urban London and the fictional world of Naruto, struggles in the endz are likened to clan rivalries and clashes of magical ninjutsu abilities.

No genjutsu, I was in that trap, chop, drop

That Lee I’m a Guy like that

Deidera birds, I’m fly like that (brrapp)

No hand signs, just waps

Sixty-four palms and we sky this clap

Akatsuki my gang, I’m stylish black

I’m Shisui, bros know I got their back

Orochimaru, you snakes can’t gap.

Beyond his individual anime fandom, AJ Tracey assumes a level of intercultural knowledge of Urban British English slang and Naruto references on the listeners’ part in order to generate the intended interlaced narrative effect. As a later generation artist that grew up within the grime scene, he taps into an existing shared hybrid cultural space that is situated inbetween the worlds of Japanimation and the endz to dialogue with an audience who must understand both languages to engage in this space. He cites ‘genjutsu’, a paralyzing battle technique used to control a victim’s mind by manipulating their five senses so they believe an illusion, to describe the ‘trap’ that binds urban youth to the ghetto. He imagines himself as the often-mocked Rock Lee who overcomes deficiencies, naysayers, and the born privileges of others through extreme effort and special training from Might Guy. He describes his ‘gang’ as the black robe wearing outsider group known as the Akatsuki. A particular focus on stories of ostracized and underdog heroes resonates with cold feelings of alienation. Perhaps we can say that Naruto is that ‘Boy in Da Corner’, to repurpose the title of Dizzee Rascal’s album, which pictures the hooded rapper sat in the corner of yellow panels as a way of communicating the positionality of disenfranchised urban black youth.

Through entwined and overlapping audio-visual narratives grime music affirms that black urban life in the endz is a science fiction, which is spatially and temporally at the ‘end of the world’, because as Tao Leigh Goffe (Citation2020) writes, ‘some perpetually live close…to the limit of the apocalypse’. ‘Apocalypse already happened’, as Mark Sinker (Citation1992, 31) opines on black science fiction. Black Britain’s life of grime is a post-apocalyptic parallel universe that exists outside of social and historical reality. The endz becomes the space at the very edges of reality that press against the cold fictional spaces found in Japanese pop cultural content. What jazz composer and pioneer of Afro-futurism, Sun Ra, once described as a slide into ‘myth’, where blackness becomes space, the void and outer darkness (Youngquist Citation2016, 192). Afro-futurism, as first coined by Mark Dery (Citation1994), describes how people of African descent draw upon science fiction and images of technologically enhanced futures to explore black-centered narratives of oppression, estrangement and emancipation. For Sun Ra, science fiction myth was more powerful than mere reality as the latter was bound in the mortal coil of finite time, whereas myth is not confined to linear historical time or ghettoized space (Youngquist Citation2016, 197). In the infinite outer space of myth, new life may emerge as alternative fictions can be apprehended and spoken forth into existence. Grime artists too embrace the cold nether-space of the ‘endz of the world’. As Wiley (Citation2017, 255) submits, ‘There’s something uplifting in the cold, too’. It is out of this liminal cold world of dissolved borders that they can re-emerge as the hybrid ‘cyborg myth’, a potent fusion of fiction and lived experiences, because the boundaries between the two were always an ‘optical illusion’ (Haraway Citation1991, 149). In these new cyborg identities, which are not limited to externally defined social categories for they are transgressive, lies the promise of agency, liberation and imaginative possibility (154).

Cyborgs made in Cold Japan

Grime is rooted in a remix culture of dubbing and sampling associated with the spread of Jamaican sound system culture across the African diaspora, where technologies are disassembled and reassembled to create new (mis)uses and meanings that lie outside of the manufacturers’ original intended purpose. Grime’s distinct expression of remix culture is especially striking as artists engage in a conscious mining of specific cold components from Japanese pop cultural artifacts to attach these to their bodies as prosthetic enhancements and re-code themselves as cyborgs in an autopoietic process of self-generation. I use cold components here to describe the technologies, sounds and themes, which are selectively extracted in a transmedia approach from multiple platforms of Japan’s ‘cool’ pop cultural goods, and converted by artists into Cold Japan parts that can be re-pieced together to generate grime cyborgs. These cold components serve as conductors allowing artists to channel their feelings of coldness because ‘the twenty-first century body no longer ends at the skin’ and includes the machines and digital devices we use to augment human bodily functioning (Graham Citation2002, 65) – not a disembodiment but a hyperembodiment (Eshun Citation1998, −002). Choosing this DIY approach to create a corporeal boundary breaking ‘extended self’ (Thweatt-Bates Citation2012, 21) by attaching cold components as prosthetic enhancements, gives the artists agency in articulation and self-definition, rather than being subjected to hegemonic discourses (Aoyagi, Kovacic and Baines Citation2020, 7).

Embodying cyborg identities demonstrates grime’s ‘radical commitment to otherness’ (Perry Citation2004, 47); a strategy of active detachment from official society and an embrace of the margins as a site of resistance (hooks Citation1989). Formerly a tool of oppression to demarcate urban black youth as subhuman ghetto dwellers, grime artists instead subvert the coldness of alienation to engage in a ‘counter-hegemonic discourse of the body’ (hooks Citation1994, 127) by accumulating cold posthuman attributes that enable them to transcend the limitations of the iconic ghetto stereotype attached to black humanity. In the words of Kodwo Eshun (Citation1998, −005) speaking of Afro-futurism within black music, they ‘amplify the rates of becoming alien’ to ‘synthesize’ themselves because for black people the ‘human is a pointless and treacherous category’. That grime artists engage in a rewiring of technologies to dehumanize and reinvent themselves is particularly significant as it disrupts the notion that technology is only ‘brought to bear on black bodies’ (Dery Citation1994, 180) through perceptions of a digital divide across racial lines or means such as experimentation, surveillance and policing. Rather, by reappropriating technologies and machines that seem to have arrived from some distant future beyond Western space-time, they can sabotage their subjugation and move out of a fixed place assigned to them by a dominant society. Equipping cold extensions to their bodies as cyborgs, they are ‘playing with the robot’, what Rose explains as, ‘like wearing body armor that identifies you as an alien: if it’s always on anyway, in some symbolic sense, perhaps you could master the wearing of this guise to use it against your interpolation’ (Dery Citation1994, 214). To be made in Cold Japan becomes, to repurpose the title of Haraway’s (Citation1991) seminal essay, grime’s ‘Cyborg Manifesto’.

Commentators that trace the history of grime’s development in London in the early 2000s highlight the importance of an increase in affordable consumer electronics, which aspiring teenage music producers who would later become the pioneers of grime, newly gained access to (Bramwell Citation2011, 135; Hancox Citation2018, 63). These changes in the marketplace of consumer goods were occurring within a broader socio-economic context that largely precluded their access to professional music studios, structured sound engineering educational programs and a seemingly impenetrable music industry. Those involved in the creation and distribution of grime music had to become ‘DIY superheroes’ (DJ Logan Sama Citation2019) reworking whatever high or low-tech devices they could find. Alongside peer-shared cracked copies of the FruityLoops music production software, video game consoles that many of these adolescent boys just happened to have at home, were indispensable tools in a growing suite of equipment. Bedrooms in London council estates became the music studios.

While video game and anime worlds intertwined and hybridized with their urban environments, grime artists were also entangled with the physical machines and wires that powered these spaces. Giving new meanings to ‘playing’ video games, during the early years of grime, artists utilized consoles as music making equipment. Brothers Skepta and Jme reveal in interviews and song lyrics, that they produced on the Super Nintendo and PlayStation using games, such as Mario Paint and Music 2000 (Vice, November 13, 2013; Fader, June 4, 2015). Further extracting from these technologies, artists selectively sample and reproduce 8-bit and 16-bit chiptune sound effects, such as beeps, suctions, swipes, chimes, coin grabbing jingles, throbs, battle cries and whips. These ‘cold’ sounds continue to make up grime’s distinctive sonic palette.

Disassembling and reordering pieces that comprise grime’s hybridized cultural space of coldness, and equipping these cold components as extensions of themselves gives artists agency in embodying empowered virtual identities. Grime’s DIY element transforms artists from helpless victims of domination in dystopian sci-fi worlds, to active players and world makers through music creation and performance. In Jme’s (Citation2015) The Very Best, an adaption of the English version of the Pokémon anime television series theme song, he utilizes imagery from Pokémon’s media mix of video games, anime and trading cards to narrate his personal journey of transcending life in the endz, which is likened to that of becoming a master Pokémon trainer. In the music video, Jme is variously depicted as an animated or gamified character wearing the clothes of the series protagonist, Ash Ketchum. Ash begins his journey as an average boy with little resources who is thrown into the wild. By catching and training Pokémon through battles and acquiring items and allies along the way, he can level up to become a master, ‘the very best’. Projecting his story onto Ash and ‘playing’ his own virtual reality, Jme raps that life began on the Meridian Walk Estate in North London’s Tottenham suggesting that he too began with few resources. However, now within the 16-bit Gameboy Advance world (which he renames ‘Rude Boy Advance’), he has successfully levelled up to reach the Pokémon city of Viridian, an advanced stage used as a rhyming contrast to his humble beginnings in Meridian. He highlights the assemblage quality of the game by recounting his own process of achieving mastery, which was obtained through hard work and an accumulation of skills, represented by his collection of rare ‘shiny Charizard’ and ‘Japanese and Chinese’ Pokémon cards. Born again within this hybridized space of Cold Japan, Jme self-generates a cyborg identity through the cumulative equipping of components found within this virtual environment to narrate a story of liberation – a playful recreation for re-creation. Cold Japan is turned into a virtual site of generative potential where artists can reshape their avatars and external environment to locate visions of emancipation. Through multisensory embodiment of cold grime cyborgs, artists can hack into and recode their identities with sonic and narrative glitches that disrupt society’s programming of black male bodies that would otherwise have them imprisoned in jail or the ghetto.

Grime’s DIY ethos follows the logic of game and anime worlds that promise infinite possibility, what Allison (Citation2006, 26) summarizes as the ‘impulse to keep changing’ through constant acquisition or instantaneous transformations. The song and music video for IC3 by Ghetts featuring Skepta (Citation2021), illustrates such an instantaneous morphing into cyborg identities. The track title IC3 overturns the meanings of the UK police identity code ‘IC3’, which is used to categorize black people as potential criminal suspects. They play on the code ‘IC’ to assert how they ‘see’ a different reality: ‘I see’ a king when looking in the mirror. In the first verse, Skepta identifies that reclaiming a knowledge of self and his history became the key to gaining his superpowers, which allowed him to change form. He lyrically expresses a rebirth and acquiring untapped powers connected to his black skin that are unlocked under pressure. This transformation under intense stress is a process that Wu Tang Clan’s RZA similarly discusses in relation to the Dragon Ball Z anime series, which he likens to the black experience. The main protagonist, Son Goku, is from an ancient Saiyan race of warriors but his knowledge of self has been destroyed. Until one day his Super Saiyan power is unleashed through tragedy and rage, revealing long spikey hair that RZA likens to dreadlocks and Afro hairstyles. ‘So I say we are the Saiyans; I even use the name Goku as a tag when I write. And when my hair is in an Afro? Word up: I’m Super Saiyan’ (RZA Citation2009, 54–55). Ghetts and Skepta are shown as having demon-like animated yellow-gold eyes and a crown that flashes above their heads. Whether it’s Super Saiyan charges in Dragon Ball Z or Evil Ryu and Violent Ken in the Street Fighter series, a change in eye color and a new crown of hair is a way of visually depicting possession and a sudden surge of power. The video incorporates these elements to invert reality and in the opening scene depicts three young black boys with boosted eyes in an empowered position staring down two white police officers. The coldness of urban and racial oppression is embraced as that energy can be harnessed to mutate into cold cyborgs who return the gaze as a form of resistance. To be sure, although drawing from similar revolutionary urges towards black liberation through what Deborah Elizabeth Whaley (Citation2006, 189) calls ‘tactical performances’ of an ‘Orientalist aesthetic’ as seen in African American hip hop and visual culture’s appropriation of Japanese samurai and Chinese kung fu warrior themes, grime cyborgs that emerge from the hybridized space of Cold Japan should not be reductively understood as ‘black bodies’ in ‘yellow masks’ (188). It is the fusion of black British urban life and Japanese pop cultural elements that gives birth to a different, fundamentally new oppositional ‘grimey’ way of being in the world that from inception is outside of the epistemological limits of ‘Afro’ and ‘Japanese’.

Financial rewards associated with grime’s increasing mainstream popularity from the 2010s has enabled artists to visit Japan as the original source of the artifacts that make up their hybridized cultural space. In the same way that grime artists construct and insert themselves into Cold Japan through remixing virtual surfaces, they recreate and physically occupy these environments in the real world. Shooting music videos in Tokyo at nighttime is a key way that artists reproduce a hybrid Cold Japan. Several music videos follow this pattern: Stormzy’s One Take Freestyle (2016), Blay Vision’s Eyes (2018) and Regret (2020), and Who Am I (2018) by fusion artists Kojo Funds and Bugzy Malone. The artists are filmed surrounded by neon-lit skyscrapers, narrow alleyways with kanji-inscribed lanterns hanging on bar doors, noisy arcade centers, highways at night, 24-hour convenience stores and underground nightclubs – all common techno-Orientalist tropes of the cyberpunk genre. There is no contradiction in performing within this milieu, as these spaces, those structures of feeling were always grime. In AJ Tracey’s (Citation2016) Buster Cannon music video filmed around streets and venues in Shibuya at night, editing techniques, such as turning up the saturation of a neon purple color so that the sky is given an unnatural hue, are used to transform Tokyo into a futuristic anime-esque augmented reality. By recrafting the streets of Tokyo into an imagined Cold Japan, artists bring the endz and Japan into the same shared hybrid grime spatiality. If a central feature of Western modernity has been the spatial and temporal displacement of black bodies and blackness to cast these in the antithetical role of the perpetual other that is out of the reach of the West (Weheliye Citation2005, 4), then perhaps digitally enhanced performances in the streets of Tokyo represent a physical self-extrication from linear models of historical time where the future supersedes the past, and a way of inserting their mutated cyborgian selves into a parallel cold grimey universe that is already future and they are the adapted posthuman natives.

Conclusion

This essay has revealed that from the early 2000s at the same moment discourses of ‘Cool Japan’ were surfacing to explain the global rise of Japanese pop culture, urban young black men in Britain were already entangled with the wires and worlds of Japanese pop cultural artifacts and remixed these components as a source of pleasure and power in the form of grime music to articulate the cold alienation felt at the margins of British society. What emerged was a hybrid cultural space of Cold JapanFootnote7 that fused lived experiences in the urban ‘endz’ of London with what were felt as the dark spaces and cold elements from Japanese video games and anime. This new space, which was born at the intersections and always lies inbetween, forms the very foundations of what it means to sound and be ‘grimey’. The figure of the cyborg is especially useful in disclosing this hybrid cultural space as it speaks to grime’s fundamental intermixedness. Grime’s DIY recombination of technologies and fictional dystopian narratives, transforms Cold Japan into a generative site of cultural resistance where counterhegemonic black identities and alternative futures can be conceived and performed. Remade as assemblages of techno-cultural artifacts, ideas and aesthetics found in Cold Japan, grime artists overturn the coldness of marginalization by becoming cold hybridized cyborgs themselves that can master this alternate virtual reality. The posthuman cyborg gains further significance for in its embodiment lies the subversion of the historical role of science and technology in demarcating the supremacy of an advanced Western modernity and the power to subjugate primitive black bodies that are ‘not yet’ civilized (Chakrabarty Citation2000, 8). This underground layer of black-Japanese transnational connectivity has hitherto been hidden from discourses of Japan ‘cool’ precisely because grime’s countercultural hybrid space of Cold Japan dismantles the fixed binaries and boundaries of East-West; organism-machine; Afro-Japanese; center-periphery; fact-fiction; present-future. Grime cyborgs made in ‘Cold Japan’ transgress and transcend these bifurcating categories to reimagine and reposition themselves in urban Britain and a postcolonial world.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (889 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Mateja Kovacic for her expert guidance, insightful feedback, and above all, committing time to read multiple drafts of this article. I also wish to thank a supportive network of Japan scholars including Manimporok Dotulong, Linda Flores, Tristan Grunow, Sho Konishi, Ben Moeller, Reginald Jackson, Marvin Sterling and the Japan Forum reviewers for their advice and comments. With special thanks to Jamie Adenuga of Boy Better Know Ltd for song lyric permissions and Jason Adenuga, Andre Jonas, Sakura Motonakano and Logan Sama for support with interviews, artwork and permissions. This article was generously supported by the Tanaka Memorial Foundation, Pembroke College, Oxford and the Toyota-Shi Trevelyan Trust.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest (whether financial or non-financial) to report.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Warren A. Stanislaus

Warren A. Stanislaus is a DPhil Candidate in History at the University of Oxford where he researches transnational, cultural and intellectual histories of modern Japan. As an Associate Lecturer at Rikkyo University’s Global Liberal Arts Program, Warren designs and delivers courses that explore Afro-Asian encounters and Japan in the wider world, while actively incorporating digital humanities and cross-sector public engagement approaches. In 2019, he was named No. 3 in the UK’s Top 10 Rare Rising Stars awards. E-mail: [email protected]. You can learn more and get in touch via his website www.warrenstanislaus.com or Twitter @warren_desu.

Notes

1 Jōnetsu to ai (情熱と愛) passion and love; kinben (勤勉) industrious; kenshin (献身) devotion; geijutsu to sōzōryoku (芸術と想像力) art and imagination; rizumu (リズム) rhythm; kyōikuteki (教育的) educational; sōzōteki (創造的な) creative.

2 A Japanese model of media convergence that disperses content, or the same characters and story across multiple channels, such as anime, video games, toys, manga, film etc. See Steinberg (Citation2012).

3 For an overview of Japan’s ‘Lost Decades’ see Funabashi and Kushner (Citation2015).

4 Grime has similarly only been imagined in this way. For instance, see White (Citation2017) for a discussion of grime as a Black Atlantic creative expression and Charles (Citation2019) who traces grime’s genealogical links to African spiritual practices and outlooks.

5 Anderson (Citation2012) describes the process by which black people are stigmatized by being ascribed with the stereotypes of an impoverished, crime-ridden, drug-infested and violent ghetto.

6 Referring to Yumeko Jabari, the protagonist in the anime series Kakegurui (2017). Yumeko is a compulsive gambler (as suggested by the Japanese title) attending an elite private school that operates a system of hierarchy based on gambling.

7 I curated a ‘Cold Japan’ Spotify playlist as a digital public engagement resource: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/0MomjaBecDZ35m8ARuKbcP?si=ccc2cf1d171a4a58

References

- Adams, Ruth. 2019. “‘Home Sweet Home, That’s Where I Come from, Where I Got My Knowledge of the Road and the Flow From’: Grime Music as an Expression of Identity in Postcolonial London.” Popular Music and Society 42 (4): 438–455. doi:10.1080/03007766.2018.1471774.

- Allison, Anne. 2006. Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Alt, Matt. 2020. Pure Invention. How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World. New York: Crown.

- Anderson, Elijah. 2012. “The Iconic Ghetto.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 642 (1): 8–24. doi:10.1177/0002716212446299.

- Aoyagi, Hiroshi, Mateja Kovacic, and Stephen Grant Baines. 2020. “Neo-Ethnic Self-Styling among Young Indigenous People of Brazil: Re-Appropriating Ethnicity through Cultural Hybridity.” Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 17:e17352. doi:10.1590/1809-43412020v17a352.

- Boakye, Jeffrey. 2018. Hold Tight: Black Masculinity, Millennials and the Meaning of Grime. London: Influx Press.

- Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten. 2011. The Cool Kawaii: Afro-Japanese Aesthetics and New Modernity. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- Bramwell, Richard. 2011. “The Aesthetics and Ethics of London Based Rap: A Sociology of UK Hip-Hop and Grime.” PhD diss., The London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Bramwell, Richard, and James Butterworth. 2019. “I Feel English as Fuck’: Translocality and the Performance of Alternative Identities through Rap.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (14): 2510–2527. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1623411.

- Bridges William H., IV, and Nina Cornyetz, eds. 2015. Traveling Texts and the Work of Afro-Japanese Cultural Production: Two Haiku and a Microphone. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Charles, Monique. 2019. “Grime and Spirit: On a Hype!.” Open Cultural Studies 3 (1): 107–125. doi:10.1515/culture-2019-0010.

- Condry, Ian. 2006. Hip-Hop Japan: Rap and the Paths of Cultural Globalization. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Dery, Mark. 1994. “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose.” In Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, edited by Mark Dery, 179–222. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Doan, Natalia. 2019. “The 1860 Japanese Embassy and the Antebellum African American Press.” The Historical Journal 62 (4): 997–1020. doi:10.1017/S0018246X19000050.

- Eshun, Kodwo. 1998. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet Books.

- Fawaz, Ramzi. 2016. The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics. New York and London: New York University Press.

- Funabashi, Yoichi and Barak Kushner, eds. 2015. Examining Japan’s Lost Decades. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Gallagher, Rob. 2017. “All the Other Players Want to Look at My Pad: Grime, Gaming, and Digital Identity.” The Italian Journal of Game Studies 6: 13–29. https://www.gamejournal.it/all-the-other-players-want-to-look-at-my-pad-grime-gaming-and-digital-identity-work/.

- Gallicchio, Marc. 2000. The African American Encounter with Japan and China Black Internationalism in Asia, 1895–1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness. London: Verso Books.

- Goffe, Tao L. 2020. “The DJ is a Time Machine.” Public Books, October 29. Accessed April 22, 2021: https://www.publicbooks.org/the-dj-is-a-time-machine/.

- Graham, Elaine. 2002. “Nietzsche Gets a Modem: Transhumanism and the Technological Sublime.” Literature and Theology 16 (1): 65–80. doi:10.1093/litthe/16.1.65.

- Hancox, Dan. 2018. Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime. London: William Collins.

- Haraway, Donna J. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

- Henthorne, Tom. 2011. William Gibson: A Literary Companion. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company.

- Ho, Fred and Bill V. Mullen, eds. 2008. Afro Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections between African Americans and Asian Americans. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ho, Jennifer. 2021. “Anti-Asian Racism, Black Lives Matter, and COVID-19.” Japan Forum 33 (1): 148–159. doi:10.1080/09555803.2020.1821749.

- hooks, bell. 1989. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 36: 15–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44111660?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- hooks, bell. 1994. “Feminism inside: Toward a Black Body Politic.” In Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, edited by Thelma Golden, 127–140. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Horne, Gerald. 2018. Facing the Rising Sun: African Americans, Japan, and the Rise of Afro-Asian Solidarity. New York: New York University Press.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. 2002. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2020. Comics and Stuff. New York: New York University Press.

- Jme. 2015. The Very Best, (YouTube Video), September 4. Accessed April 22, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XvsTYq9INU.

- Kearney, Reginald. 1998. African American Views of the Japanese: Solidarity or Sedition? Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Kelley, Robin D. G. 2003. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. New York: Beacon Press.

- Kelts, Roland. 2006. Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Logan, Sama. 2019. Keepin it Grimy Podcast: Episode 15 Blay Vision (YouTube Video) 00:40:14–00:40:52, August 20. Accessed April 22, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWqZjxtL6bQ.

- McGray, Douglas. 2002. “Japan’s Gross National Cool.” Foreign Policy 130 (130): 44–54. doi:10.2307/3183487.

- McLelland, Mark, eds. 2017. The End of Cool Japan: Ethical, Legal, and Cultural Challenges to Japanese Popular Culture. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- McLeod, Ken. 2013. “Afro-Samurai: Techno-Orientalism and Contemporary Hip Hop.” Popular Music 32 (2): 259–275. doi:10.1017/S0261143013000056.

- Miller, Laura. 2011. “Taking Girls Seriously in “Cool Japan” Ideology.” Japanese Studies Review 15: 97–106.

- Morley, David, and Kevin Robins. 1995. Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. London and New York: Routledge.

- Mullen, Bill V. 2004. Afro-Orientalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Luvaas, Brent. 2012. DIY Style: Fashion, Music and Global Digital Cultures. London: Berg.

- Napier, Susan J. 1998. Anime: From Akira to Princess Mononoke – Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave.

- Nye, Joseph S., Jr. 1990. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy 80 (80): 153–171. doi:10.2307/1148580.

- Perry, Imani. 2004. Prophets of the Hood, Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Prashad, Vijay. 2002. Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Reynolds, Simon. 2011. Bring the Noise: 20 Years of Writing about Hip Rock and Hip Hop. Berkeley: Soft Skull Press.

- Rose, Tricia. 1994. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press.

- Russell, John G. 2012. “Playing with Race/Authenticating Alterity: Authenticity, Mimesis, and Racial Performance in the Transcultural Diaspora.” CR: The New Centennial Review 12 (1): 41–92. doi:10.1353/ncr.2012.0022.

- RZA. 2009. The Tao of Wu. New York: Riverhead Books.

- Sinker, Mark. 1992. “Loving the Alien—Black Science Fiction.” The Wire 96 (February): 30–33.

- Steinberg, Marc. 2012. Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sterling, Marvin D. 2010. Babylon East: Performing Dancehall, Roots Reggae, and Rastafari in Japan. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Sugimoto, Yoshio. 2014. An Introduction to Japanese Society. 4th ed. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press.

- Thweatt-Bates, Jeanine. 2012. Cyborg Selves: A Theological Anthropology of the Posthuman. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate.

- Valaskivi, Katja. 2013. “A Brand New Future? Cool Japan and the Social Imaginary of the Branded Nation.” Japan Forum 25 (4): 485–504. doi:10.1080/09555803.2012.756538.

- Weheliye, Alexander G. 2005. Phonogrophies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Whaley, Deborah Elizabeth. 2006. “Black Bodies/Yellow Masks: The Orientalist Aesthetic in Hip-Hop and Black Visual Culture.” In AfroAsian Encounters: Culture, History, Politics, edited by Heike Raphael-Hernandez and Shannon Steen, 188–203. New York and London: New York University Press.

- White, Joy. 2017. Urban Music and Entrepreneurship: Beats, Rhymes and Young People’s Enterprise. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Wiley. 2017. Eskiboy. London: William Heinemann.

- Yano, Christine R. 2013. Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek across of the Pacific. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Youngquist, Paul. 2016. A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afrofuturism. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Discography

- Tracey, A. J. 2016. “Buster Cannon.” Lil Tracey – EP. ℗© AJ Tracey.

- Tracey, A. J. 2020a. “Yumeko.” Secure The Bag! 2 – EP. ℗© AJ Tracey.

- Tracey, A. J. 2020b. “Hikikomori.” Secure The Bag! 2 – EP. ℗© AJ Tracey.

- Blay Vision. 2018. “Won’t Let Em.” Pre Vision. © Blay Vision.

- Blay Vision. 2019. Do Not Disturb. © Blay Vision.

- Ghetts feat. Skepta. 2021. “IC3.” Conflict of Interest. ℗© Warner Records UK.

- Jme. 2006a. “96 Bars of Revenge.” Boy Better Know – Shh Hut Yuh Muh Edition 1. © Boy Better Know.

- Jme. 2006b. “Final Boss.” Boy Better Know – Shh Hut Yuh Muh Edition 1. © Boy Better Know.

- Jme. 2006c. “The Future.” Boy Better Know – Poomplex Edition 2. © Boy Better Know.

- Jme. 2019. “96 of My Life.” Grime MC. ℗© Boy Better Know.

- Joe Grind and Jme. 2019. Boss. ℗© SN1 Records.

- Skepta. 2012. “Castles.” Blacklisted. ℗© 3Beat.

- Skepta. 2016. “Konnichiwa.” Konnichiwa. © Boy Better Know.

- Wiley. 2013. Born in the Cold. ℗© Big Dada/A-List.