ABSTRACT

Labels on food and beverage products are important information sources that can profoundly influence consumer evaluations. This is particularly so for wines, where the text, design, and colour of labelling appearing on both the front and back of the bottle will shape consumer reactions and guide purchase intent. Importantly, the colour of a wine’s back label – that which appears on the rear of the bottle – offers a range of opportunities for wine marketers to generate heightened levels of involvement and curiosity in wine. Despite this, prior research has yet to fully examine how the colour of a back label shapes consumer attitudes and purchase behaviours. Guided by construal level theory and employing an experimental design, the current research set out to test how colour (vs. black and white) labelling influenced consumer decision-making and whether the colour of the focal wine influenced the effects. The results demonstrate black and white labelling increases consumer purchase intentions by increasing the consumer’s level of involvement and curiosity. However, the effect only occurred when the labels were paired with a red wine. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed, as well as directions for future research.

Introduction

The design of a wine label is one of the most important decisions a wine marketer makes. This is largely due to the design of the label influencing consumer evaluations and behaviours towards the wine product (Celhay & Remaud, Citation2018; Lick et al., Citation2017; Staub et al., Citation2020). The significant influence of wine labels is underpinned by the labels being perceived as indicators of quality (Lunardo & Rickard, Citation2019) and taste (Jaud & Melnyk, Citation2020). One important design consideration involves the colours used in the wine label. This is highly relevant to our study, given prior research (Spence, Citation2015) has shown colour is one of the most important design elements because it can influence the perceived taste (Spence et al., Citation2010), smell (Parr et al., Citation2003), and texture (Chylinski et al., Citation2015) of food and beverages, including wine. As such, the colour of wine labels has received increasing academic attention in recent years (Celhay & Remaud, Citation2018; Lick et al., Citation2017; Pelet et al., Citation2020).

Wine labels communicate a range of diverse information to potential consumers. This is particularly the case with front labels, which might include information such as the brand, grape variety, country, region, and vintage, as well as any other relevant information (Lockshin & Corsi, Citation2012). However, prior research (Goodman, Citation2009) has suggested back labels are more important determinants for product selection. This may be why almost two-thirds of wine consumers read a bottle’s back label to inform their purchase decision (Charters et al., Citation1999). Despite that, a review of existing literature shows a dearth of research examining back labels’ influence on consumer attitudes and purchase behaviours. Building on this, the current study will examine the differential effects a back label’s colour (vs. black and white) has on wine consumer decisions.

An important point when comparing the effects of colour (vs. black and white) labels is that either option can influence the effectiveness of any marketing message, whether this involves advertising or packaging (Lee et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2020). For example, in some contexts, research (Wang et al., Citation2020) suggests black and white imagery ‘feels right’ in comparison to other colours and is more likely to encourage product choice (Lee et al., Citation2014). However, when this is applied to wine labelling, most of the research to date has focused on front labels (Galati et al., Citation2018; Lick et al., Citation2017; Pelet et al., Citation2020), despite back labels often being a key source of information for wine consumers (Mueller et al., Citation2010). Complicating any research on wine label colour is that the colour of the product can also change, meaning the influence of any label colour on consumer decision-making might be affected by the colour of the wine in the bottle.

While prior research (Celhay & Remaud, Citation2018; Lick et al., Citation2017) has highlighted the importance of colour for wine labels, studies have typically focused the findings on red wine varieties, including cabernet sauvignon, merlot, and shiraz. This is despite the growing popularity of white wines, such as sauvignon blanc (Karlsson & Karlsson, Citation2021). The focus on labelling for red wine varieties suggests an important gap in the literature exists, given that prior research (Bruwer et al., Citation2011; Mora et al., Citation2018) shows motivation and preference for red or white wine differ significantly. Thus, it may be that critical nuances regarding wine labelling have been overlooked, given the lack of empirical evidence comparing the effects of label colouring using red and white wine varieties.

Colour, whether on a label or as part of the product, can profoundly influence consumer attitudes. Importantly, prior research (Ferdman, Citation2014) has suggested the colour of the wine can influence consumer involvement. The concept is premised on 2014 research from the United States showing American consumers prefer red (vs. white) wine. More recently, research (Thach et al., Citation2020; Thach & Camillo, Citation2018) has shown almost three-quarters of American wine consumers prefer red wine. This preference for red wine may mean consumers are more ‘involved’ in the product and its labelling if it is red (vs. white) wine. In this regard, involvement is often measured through an individual’s interest in an object (Zaichkowsky, Citation1985). Given that American consumers are shown to prefer (and purchase more) red wine, they are likely more ‘interested’ and thus more ‘involved’ in red wine purchases than white wine. Therefore, it is plausible to suggest red wine will have a stronger impact upon involvement than white wine. What is more, the colour of the wine and the label might also elicit certain emotional responses in consumers.

Emotion is a particularly important consideration in wine marketing, which, to date, scholars have noted as not being thoroughly explored (Calvo-Porral et al., Citation2020). Of the limited studies that have examined emotions related to wine consumption, the majority have focused on asking how consumers feel when consuming or thinking about wine as opposed to why this emotive state has been created (Niimi et al., Citation2019). The lack of investigations into the emotions associated with wine and why they may be shaped by the colour of wine labels across different wine types is a noteworthy limitation in current knowledge, as researchers in food and drink consumption note that context is important when considering the emotions elicited (Ferrarini et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, of the research available, the majority take a dimensional (valence-based, e.g. positive vs. negative) perspective to measuring and understanding emotions (e.g. Calvo-Porral et al., Citation2021; Chi et al., Citation2020; Pelegrín-Borondo et al., Citation2020). Whilst a dimensional perspective to emotions offers some limited understanding, different emotional states impact different cognitive and behavioural outcomes (Hosany et al., Citation2021). Thus, understanding the discrete emotions elicited by wine consumption becomes important to precisely understand how they predict behavioural outcomes. This research, therefore, seeks to extend understanding of the role of emotions in wine by taking a more nuanced approach to its conceptualisation and measurement, specifically by exploring the discrete positive emotional state of ‘curiosity,’ a positive emotion whereby an individual feels pleasure or reward for exploring, acquiring, and expanding knowledge (Thomas & Vinuales, Citation2017). The third aim of this research is to explore the potential mediating role of curiosity in explaining the process by which different colours of wine labels for different wine types are influential on consumers’ purchase intentions. As such, the paper begins by outlining the conceptual development and approach to developing the hypotheses. This is followed by a section detailing the methodology and analyses and finishes with a general discussion that identifies the theoretical and managerial contributions of this research.

Conceptual development

The importance of wine labels

Wine labels communicate a range of diverse information to potential consumers. This is particularly the case with front labels, which might include information such as the brand, grape variety, country, region, and vintage, as well as any other relevant information (Lockshin & Corsi, Citation2012). Despite that, prior research (Mueller et al., Citation2011) suggests consumer perception of wine labels is primarily subconscious. As a result, it has been suggested back labels are more important determinants for product selection (Goodman, Citation2009). This dovetails with research by Charters et al. (Citation1999) that found almost two-thirds of consumers regularly read back labels to inform their purchase decisions. Further, the research by Charters et al. (Citation1999) found that even though the back label information is important, consumers have difficulty matching the back label descriptions to the expected taste experience. However, because colour can have such a profound influence on human perception (Chylinski et al., Citation2015; Northey et al., Citation2018), the colour of the wine is also an important consideration given the colour of the wine and the colour of the label might act in concert to shape consumer preference.

Wine type and label colour

Though research has considered what motivates the consumption of red or white wine (e.g. Thach et al., Citation2020), as evidenced in , studies rarely compare both red and white. Further, little comparison has occurred when specifically considering wine back label colour, involvement, curiosity, and purchase intentions. Many wine studies have varied in their foci of colour of labels; however, there appears to be a common approach to comparing colours which are monochrome and colour, with this at times being termed traditional and non-traditional (Elliot & Barth, Citation2012), as well as heraldic and vivid (Pelet et al., Citation2020). Further, whilst prior research provides some understanding of the importance of wine label colours, the majority have also focused on front labels. Thus, whilst there is evidence of the importance of labels and their colours for wine, how this translates to back of wine labels has yet to be considered.

Table 1. Chronological overview of related studies on Wine type, label colour, emotion, and purchase intentions.

There are notable differences in front and back labels for wine. For example, front labels often provide more heuristic characteristics of the brand, whereas the back label is focused more on taste attributes and is used to reduce the perceived risk of purchase (d’Hauteville, Citation2003). Given the importance of back labels for wine, the rarity of the investigations into this area is interesting. For example, in addition to the Charters et al. (Citation1999) study above, Mueller et al. (Citation2010), found that, amongst Australian consumers, back label information such as taste attributes, food pairing information, and family information was most preferred. Thus, given the importance of back wine labelling, it is critical to further understand this area. Next, the concept of involvement is defined and reviewed.

Involvement in wine

Involvement refers to a person’s perceived relevance and the significance of an object to their needs, values, and interests (Zaichkowsky, Citation1985). Based on previous wine research, in the current study, involvement is defined as the level of interest and importance wine and wine consumption has to the individual (Bruwer et al., Citation2017; Hollebeek et al., Citation2007). As demonstrated in , the effect of wine label colour on involvement has yet to be thoroughly explored – despite involvement being shown to exert a considerable influence over the purchase and consumption of wine (Hollebeek et al., Citation2007) and being a concept well-suited to wine research (Bruwer et al., Citation2017). Involvement can be conceptualised according to a product’s enduring, long-lasting personal relevance or situational, transitory short-term changes in the consumer’s immediate environment (Lesschaeve & Bruwer, Citation2010). The current study aligns with the enduring approach to involvement as prior wine research shows extrinsic cues, also referred to as image variables, align with this perspective (Lesschaeve & Bruwer, Citation2010). Thus, given that wine labels are image-based, the enduring perspective to involvement is suggested to appropriately align with the current study.

Emotional curiosity relating to wine

Emotions are an essential agent in the human behaviour system (Khalil et al., Citation2022). This is particularly true when considering wine consumption and curiosity (Charters & Ali-Knight, Citation2002). A review of psychology literature demonstrates that curiosity has been measured as both an emotional state and a personality trait (Reio et al., Citation2006). For example, from a trait perspective, scales have measured how individuals learn about things as ‘interesting,’ ‘exciting,’ and ‘enjoyable’ (Litman & Jimerson, Citation2004; Naylor, Citation1981). Whereas, when conceptualising and investigating curiosity as an emotional state, researchers have assessed the influence of different sensory stimuli on creating this response in individuals. For instance, Collins et al. (Citation2004) evaluated the positive feelings of curiosity relating to visiting art galleries and museums. The latter is particularly relevant to the current study, given that this research aims to understand how wine labels as a form of sensory stimuli may trigger a change in curiosity levels. Thus, the current study aligns with these prior studies of curiosity, viewing this state as being emotionally driven, whereby individuals feel positive affective states by exploring, acquiring, and expanding knowledge about wine (Thomas & Vinuales, Citation2017).

Given that wine consumption is often seen as a hedonically (emotionally) orientated activity (Neeley et al., Citation2010), it is logical to propose that curiosity may be altered by stimuli such as different colours of wine labels. To some degree, this may be explained by wine consumption being an ‘experience’ (Bruwer & Rueger-Muck, Citation2019) and potentially involving situations that are new or different (Kansara, Citation2019). Research supports the influence of curiosity on wine purchasing behaviour, demonstrating that curiosity can lead to consumers paying a higher price for organic wines (D’Amico et al., Citation2016) or to motivations to undertake a wine tour (Kansara, Citation2019). One may suggest that wine label colour could alter the levels of consumer curiosity as it is often an informational cue, and some research appears to support this idea. Research shows that the level of information provided about a product impacts curiosity and its influence on product attitudes (Daume & Hüttl-Maack, Citation2020). Similar results were evidenced in another study whereby advertising that created a sense of ‘mystery’ increased consumers’ curiosity (Toteva et al., Citation2021). Thus, as colour too can provide information to consumers about products, it could be possible that wine label colours may also change consumers’ levels of curiosity. However, such assumptions are yet to be empirically validated. The current research aims to provide insight by exploring the impact of wine label colour on consumer curiosity.

Conceptual model and theoretical framework

Wine is an inherently hedonic product (Neeley et al., Citation2010; Ugalde et al., Citation2022). According to prior research (Scarpi, Citation2021), such hedonism can lead to higher construal levels in consumers. As a result, construal level theory (CLT) becomes an important element underpinning the conceptual development of this research.

CLT (Trope et al., Citation2007) explains how psychological distance influences the thoughts and behaviours of individuals. CLT proposes individuals construe objects that are psychologically ‘near’ by their concrete, detailed attributes. By contrast, ‘distant’ objects are construed by their abstract, high-level attributes or characteristics. This is important with a product like wine because the product can be construed in abstract (high-level construal) or concrete (low-level construal) ways, depending on the perceived psychological distance between the consumer and the product (Adler & Sarstedt, Citation2021; Dhar & Kim, Citation2007). According to CLT, several types of psychological distance exist. However, for the purposes of this research, temporal distance – the distance of time – is used as the main theoretical explanation for why black and white (vs. colour) labelling will lead to observable differences in involvement, curiosity, and purchase intentions.

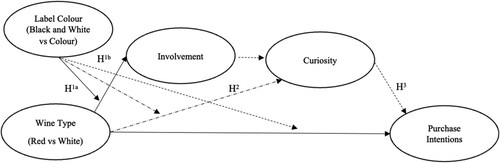

Prior research (Yan & Sengupta, Citation2011) involving CLT has shown abstract representations of a product or brand have a greater influence on consumer evaluations and choice when the object is perceived to be more psychologically distant. Because of this, CLT is an appropriate theoretical lens that might explain why black and white (vs. colour) wine labels may have a differing impact upon consumers’ perception of wine. In fact, construal level theory is a useful theoretical lens when comparing black and white to colour imagery in a variety of settings, such as consumer goods and advertising (Lee et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2020). Research (Hansen, Citation2019) has also shown construal level theory to help understand why colour affects consumers’ drink perceptions. Thus, given construal level theory has been used in prior studies with similar aims to the current research, it was deemed an appropriate and useful foundation to hypothesise the relationships presented in .

Hypotheses

Wine types, colour labels, and involvement (H1)

It could be suggested that the red wine variety (vs. the white wine variety) will have a significantly stronger impact on involvement. This proposition is supported by industry research and media publications, which report US consumers prefer red to white wine (Ferdman, Citation2014). This is also further supported by Thach and Camillo’s (Citation2018) study, which showed that 69% of their US sample preferred red wine. Furthermore, Thach et al.’s (Citation2020) study shows that US consumers across different age cohorts had significantly higher preferences for red wine. Involvement is often measured through an individual’s interest in an object (Zaichkowsky, Citation1985). As consumers are shown to prefer (and purchase more) red wine, it is likely they are more ‘interested’ and thus more involved in red wine purchases as opposed to white wine. Therefore, it is plausible to suggest red wine potentially will have a stronger impact upon involvement than white wine.

In addition to proposing consumer involvement will be higher when exposed to red wine, it is also suggested that this effect will become stronger when black and white back labels are used instead of coloured labels. When considering construal level theory for wine labelling, it could be suggested individuals tend to associate black and white labels with high-level temporal distance, signifying abstract thinking (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). For instance, black and white labels are associated with the past (high-level construal) in comparison to colour labelling, which would be associated with a more recent time (low-level construal) (Lee et al., Citation2014). This, for example, could be explained by black and white movies or other imagery being continuously paired and associated with the distant past, whereas more recent advancements or future advancements in technology and other products are associated with colour (Lee et al., Citation2014). More recent neuroscience experiments support this notion, suggesting through the lens of construal level theory that when imagining past events, individuals often consider monochrome (black and white), whereas when imagining future events, it is often in colour (Stillman et al., Citation2020). Transferring this thinking of black and white colours signifying high-level construal thinking of past events, it is suggested that this will enhance involvement (interest) in the wine. This is due to wine being noted for improving with age due to the chemical reactions among the wine’s sugars, acids, and other components. A black and white label will, therefore, signal to consumers that the wine is older, making consumers more interested in (involved with) that wine. Thus, although the prevailing discussion of construal level theory and related literature provides strong evidence to suggest the effect of red wine on consumer involvement will be amplified using black and white labelling, there appears to be little literature that demonstrates that these effects indeed might occur. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed to be empirically tested in the current study:

H1a. Red wine (versus white wine) will have a more profound positive influence on involvement.

H1b. Red wine (versus white wine) will have a stronger positive impact upon wine involvement for those consumers exposed to a black and white label (versus coloured label).

Wine types, label colour and curiosity via involvement (H2)

Although it is predicted that consumers will be more involved with red wine with black and white labels, it is also expected that consumers will subsequently (indirectly) experience an emotional response, specifically curiosity. To support this proposed relationship, construal level theory is used to link wine type and wine labels to curiosity, and support from the literature is used to justify the link between involvement and curiosity.

Support for the proposed indirect effect of red wine with black and white labels on curiosity via involvement can be drawn from construal level theory, which suggests the higher the perceived temporal distance, the greater the level of abstract thinking a consumer must process (Adler & Sarstedt, Citation2021; Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). Prior research demonstrates that high levels of construal make people think more adventurously (Liberman & Trope, Citation1998) and that an individual’s construal can also positively influence their creativity (Jin et al., Citation2016). Thus, as this research has theorised black and white labels to be representative of high-level construal in line with prior research (Lee et al., Citation2014), it is likely that this will enhance the indirect effect of red wine on curiosity via involvement.

As the proposed relationship in H2 is a mediation, this study suggests the mechanism by which curiosity is increased is due to a consumer’s level of involvement. It is important to consider why this should occur based upon evidence from extant literature. Santos et al.’s (Citation2017) study lends support for the relationship between involvement and curiosity, with their results demonstrating that wine involvement has a positive direct influence on the destination emotions for Porto wine cellars. In further support, Calvo-Porral et al. (Citation2019) showed that highly involved wine consumers experience a stronger level of emotional response, and this, in turn, also strengthens the emotional-satisfaction link for wine. In a related study by the same authors, Calvo-Porral et al. (Citation2021) confirmed that consumers’ level of involvement explained differences in consumers’ emotional responses to wine.

Despite both construal level theory and the literature providing support and explanation, there is a need to empirically validate this relationship. Thus, this study seeks to shed new insight by testing the following proposed moderated mediation hypothesis:

H2. Red wine (versus white wine) with a black and white label (versus coloured label) will have a significant indirect impact on curiosity via involvement.

Colour label, wine types, and purchase intentions (H3)

In H3, wine type and colour label are hypothesised to impact purchase intentions via the serial mediation of involvement and curiosity. To justify this relationship, literature supporting the impact of label colour on amplifying motivational factors’ effect on purchase intentions is first discussed. After this, literature supporting the mediating roles of involvement and emotions (curiosity) is discussed to justify the serial mediation relationships.

First, regarding the impact of labelling colour on purchase intention relationships, research shows that the colour of labels can amplify the effect of motivating factors on purchase intentions (Pelet et al., Citation2020). For instance, Pelet et al.’s (Citation2020) study found consumers exposed to labels with heraldic colours (vs. vivid colours) for wine experience a stronger effect of authenticity on buying intention. Other studies have shown that green (versus) pink labels for coffee, which are angular (vs. round), lead to stronger purchase intentions (de Sousa et al., Citation2020). Thus, in line with these previously mentioned studies and consistent with the prior hypotheses (H1-H2), the current study also proposes that the impact of red wine (vs. white wine) on purchase intentions will be significantly stronger when black and white labels are used. However, an important nuance of this study is its attempt to uncover the multiple mechanisms that explain why this relationship occurs. These explanatory mechanisms (mediators) are involvement and the emotion of curiosity, which are justified next.

In relation to involvement being considered as a mediator in wine literature, Taylor et al.’s (Citation2018) study shows involvement to mediate the relationship between motivation and wine consumption for US consumers. Similar findings of involvement mediating relationships have also been found in the study of food consumption (Lim et al., Citation2019; Pourfakhimi et al., Citation2021; Teng & Lu, Citation2016). Teng and Lu’s (Citation2016) study shows that involvement mediates the relationship between consumption motives and behavioural intentions to consume organic food. Pourfakhimi et al.’s (Citation2021) study also confirms involvement as a mediator, evidencing that food involvement mediates the relationship between neophobia and well-being in the case of international tourists visiting Iran. In further support, involvement has also been shown to mediate the relationship between gastronomy online reviews and behavioural intentions to consume ethnic food (Lim et al., Citation2019). Thus, based on evidence from prior wine (Taylor et al., Citation2018) and food studies (Lim et al., Citation2019; Pourfakhimi et al., Citation2021; Teng & Lu, Citation2016), the current research also proposes involvement will be the first mediator of the wine type and back label colour-purchase intention relationship.

Next, the second and sequential mediator to involvement, curiosity, is considered based on prior literature. Recall that it was suggested that red wine with black and white labels should have a stronger effect based on related literature suggesting it would trigger feelings of the past via abstract processing. In support of this notion of the impact of red wine and black and white labels on purchase intentions via the mediator of emotions, the study of Chi and Chi (Citation2022) demonstrates that past-oriented cognition (one imagining living in a past time) on visit intentions for heritage tourism sites is mediated by positive emotions (Chi & Chi, Citation2022). Other studies also evidence the mediating role of emotions when considering purchase intentions and related outcomes such as customer satisfaction (Jang & Namkung, Citation2009; Song & Qu, Citation2017). Song and Qu (Citation2017) demonstrate that positive consumption emotions, including joy, excitement, relaxation, and refreshment, mediate the value and customer satisfaction relationship when eating at a restaurant. More relevant to the focus of purchase intentions in the current study, Jang and Namkung (Citation2009) find that positive emotions mediate the relationships between the atmospherics of a restaurant and future purchase intentions. From the previously raised points and review of prior studies, it can be concluded that curiosity as a positive emotion should also mediate the wine type and wine label-purchase intention relationship.

Based on the prior discussions, this study suggests that the interaction of wine type and wine labelling will impact purchase intentions, but this will be serially mediated by involvement and curiosity. Thus, the following moderated serial mediation relationship hypothesis is proposed:

H3. The influence of red wine (versus white wine) with black and white labels (versus colour labels) on purchase intentions will be mediated by an individual’s involvement and curiosity toward the wine in a moderated serial mediation relationship.

Methodology

Participants and design

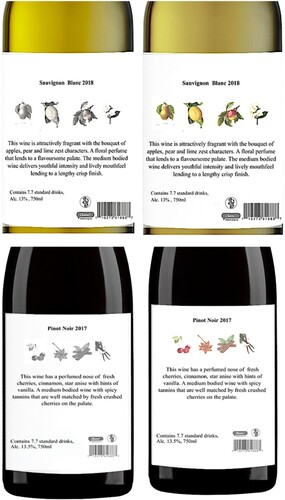

A total of 491 participants (56.61 percent female; Mage = 38, SD = 12.19) were recruited through a research agency in the United States. The study employed a 2 (wine type: red vs. white) x 2 (wine back label colour: black and white vs. colour) between-subjects design (see ). The study was conducted online, whereby participants were randomly allocated to one condition of the experiment using the randomisation feature within the survey platform Qualtrics.

The wines utilised as stimuli for this study were fictitious to eliminate any potential confounds with previous attitudes towards existing wine brands, ruling out alternative explanations to the observed results. Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir represented the white and red wine types, respectively. To ensure realism in the label, the descriptions of the tastes for each wine were designed to align with that grape variety. These design features enabled the authors to create black and white and colour variations of the labels.

Measures

To measure the mediators, involvement and curiosity, and the outcome variable, purchase intentions, reliable and valid scale items were adapted from previous studies (Hollebeek et al., Citation2007; Lu et al., Citation2016; Wiggin et al., Citation2019). For involvement, three items were adapted from the study of Hollebeek et al. (Citation2007). The items were measured on a 9-point Likert scale and included: (1) ‘the appearance of the wine in the glass is very important to me,’ (2) ‘I have a strong interest in wine,’ and (3) ‘The aroma of the wine is very important to me’ (α = .704, loadings .75-.81, average variance explained (AVE) = .62). To measure curiosity, we used a single item 9-point scale (1 = ‘not at all,’ 9 = ‘extremely’), ‘having seen this label I feel curious,’ which was adapted from Wiggin et al. (Citation2019). Purchase intention was measured with a single item 9-point scale ‘Having seen this label, how likely are you to buy this wine?’ (1 = ‘not likely,’ 9 = ‘extremely likely’) which has been widely used in wine research (e.g. Lu et al., Citation2016).

Results

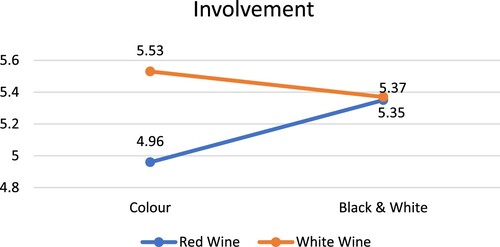

Hypothesis 1. First, manipulation checks were taken to test the perceived colour (colour vs. black & white) of the stimuli. The results revealed significant differences between the conditions, in line with the images on each label. Following that, a moderated regression analysis (PROCESS, model 1) was run with involvement as the dependent variable. For the independent variables, the authors included wine type (1 = red wine, 2 = white wine) and label colour (1 = black and white, 2 = colour) and their two-way interactions. Wine type (B = 1.15, SE = .44, p = .01) and label colour (B = .42, SE = .20, p = .03) were shown to have a significant positive effect on involvement. As hypothesised, a significant interaction effect was observed (B = -.59, SE = .28, p = .03); see and .

Table 2. Moderated Serial Mediation Results.

Hypothesis 2. Consistent with H2, the authors used PROCESS Model 8 to test for a moderated mediation, with 5,000 bootstraps and a 95 percent confidence interval. When the authors examined the impact of wine type and label colours interaction on curiosity, through the mediator of involvement, it was found this effect was significant for red wine with black and white labels (B = .26, LCI = .07, UCI = .48). In contrast, the indirect was non-significant for white wine (B = -.01, LCI = -.20, UCI = .16). The index of moderated mediation was significant (index = -.26, LCI = -.57, UCI = -.02).

Hypothesis 3. To test H3, which proposed a serial mediation relationship, the authors used Model 85 of PROCESS with 5,000 bootstraps and a 95 percent confidence interval. In this test, the interaction effect of wine type and label colours on purchase intentions via the mediators of involvement and curiosity. The indirect effect of red wine with a black and white label was significant (B = .15, LCI = .04, UCI = .27) but not for the white wine condition (B = .00, LCI = -.11, UCI = .09). The index of moderation serial mediation also confirmed the indirect effect the red wine x black and white label as being significantly stronger (index = -.15, LCI = -.33, UCI = -.01).

Discussion

Theoretical implications

As noted previously, there was a lack of research relating to back labels of wine (for a notable exception, see Mueller et al., Citation2010), particularly investigating black and white versus coloured labels for different wine types (red and white), as well as emotions (e.g. Calvo-Porral et al., Citation2020). The current paper theorised relationships using construal level theory as a basis to support and explain the relationships within the conceptual model (). Further, this research took a novel approach by examining a moderated serial mediation to better understand the mediating mechanisms by which wine type and wine label colour increase the likelihood of purchase. In taking these theoretical and empirical approaches, this research contributes to the literature in three ways.

First, this paper contributes by leveraging construal level theory to understand how yet to be compared colour comparisons for back wine labels may enhance consumers’ responses. In line with construal level theory studies (Lee et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2020), the current research demonstrates how black and white labels signify high-level temporal distance and abstract thinking (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010), creating heightened levels of involvement. The theorising and empirical results of this study, therefore, provide explanations and guidance to future scholarship regarding how the application of colours on wine labelling may represent different levels of construal and how these impact consumers’ evaluation of food and beverage products such as wine.

The second contribution of this paper concerns the contemplation of emotions, specifically curiosity as a mediating mechanism, which explains consumer responses toward wine marketing. Emotions are under-researched in wine (Calvo-Porral et al., Citation2020), and literature has generally concentrated on valence-based (positive vs. negative) emotional approaches (Calvo-Porral et al., Citation2021; Chi et al., Citation2020; Pelegrín-Borondo et al., Citation2020). Researchers studying emotions have called for more nuanced and precise understanding using discrete approaches (Hosany et al., Citation2021), and this research has begun to address this gap. Through the lens of construal level theory, and particularly high-level construal whereby individuals use abstract thinking, this research provides evidence that the emotion of curiosity is one mechanism that explains how wine types and wine back label colours influence consumer judgement and purchase intentions. The theorising and empirical results of this study, therefore, provide guidance to future research to consider the inclusion of curiosity as an emotional explanatory factor when considering food and beverage products such as wine, which may use high-level construal or require abstract thinking of consumers.

Given prior wine literature has not extensively explored the concepts of foci to the current research, it is not surprising that the literature has yet to consider their interrelationships to explain consumer evaluations. This research has therefore bridged multiple streams of literature pertaining to wine type (Thach et al., Citation2020; Thach & Camillo, Citation2018), wine label colours (Celhay & Remaud, Citation2018; Lick et al., Citation2017; Pelet et al., Citation2020), involvement (Hollebeek et al., Citation2007; Roe & Bruwer, Citation2017; Taylor et al., Citation2018) and curiosity (Thomas & Vinuales, Citation2017). Combining these literature streams and empirically demonstrating a moderated serial relationship provides a deeper theoretical explanation as to the psychological processes (involvement followed by curiosity) consumers have toward wine and how wine label colours can amplify this. This study, therefore, bridges these bodies of literature and, by doing so, empirically demonstrates how they collectively can be used to explain consumer responses to wine marketing and the mediating (involvement and curiosity) or moderating roles they play (wine label colour).

Practical implications

There are several practical implications derived from the findings of this study. The results of this study suggest wine marketers should carefully consider the type of wine (i.e. red, or white) that they are attempting to select labelling for and subsequently market. For instance, wineries and wine marketers which only focus on red grape varieties should strongly consider using back black and white labels in comparison to coloured labels. In addition, when considering the black and white labels, designers should consider how they can create a sense of temporal distance (e.g. age or history) for red wine. It is also recommended that for wineries and marketers with a portfolio of red and white varieties, black and white labels be used across both varieties where possible. This is due to the results evidencing black and white labels increasing purchase intentions for red wine and having no significant negative impact on white wines. For wineries and marketers who focus on white wine alone, they have some greater flexibility and can be confident that the use of black and white or colour labels will not have a considerable impact.

A second practical implication arising from the findings relates to construal level theory and curiosity for wine marketing. The results of the current study suggest wine marketers should consider targeting their efforts, inclusive of consideration for wine labels, towards triggering a curious reaction potentially via abstract thinking based upon temporal distance. Wine marketers should, therefore, consider how they can create high-level construal and large temporal distance, which can assist in potentially creating interest and curiosity in the wine. The results of this study, for instance, support practices whereby winery tours or labels discuss the history and heritage of the wine as this high-level construal assists in engaging consumers’ interest and curiosity, which are likely to increase their intentions to purchase the wine.

Limitations and future research directions

Like all research, this study has some limitations that provide opportunities for future research. The first limitation is that this study was conducted with a US sample. The meaning of colour across different markets and cultures can be considerable (see Spence & Velasco, Citation2018). As a result, future research could explore whether the influence of wine back label colours differs across different cultural markets and whether any other important nuances exist. For example, a consumer’s experience with wine might affect the influence back label attributes have on purchase decisions. A second limitation is that survey participants were only shown back labels, meaning their responses were entirely dependent on the attributes of the back label shown. However, in a retail environment, consumers will likely be exposed to the front label of the bottle, as well as shelf signage and other environmental factors. Future research could examine the effects of the current study in a field study, where survey participants are exposed to the whole range of visual cues that exist in a retail setting. A third limitation is that the current study did not contextualise the situation by which the wine was bought or to be consumed. Party, gifting, and casual consumption could all play a potentially additional explanatory role in how or why colour of wine labels influences consumer responses. Furthermore, there may also be design considerations where the colour being used in the label may elicit different effects (i.e. when pictures are used in the label vs. not). This invites additional research that investigates the interaction between the design and colour of labels. Finally, future research could conduct scenario-based or field experiments to uncover whether the consumption situation and context may change the nature of the relationships observed in the current study.

Conclusion

Overall, this study contributes new insight into the domain of wine marketing, specifically showcasing the imperative role of wine labels. It provides an important foundation for future theory and practice as well as areas of future research. This research has demonstrated that black and white labels for red wine can generate significantly stronger consumer responses and that this can be explained through construal level theory.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adler, S., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). Mapping the jungle: A bibliometric analysis of research into construal level theory. Psychology & Marketing, 38(9), 1367–1383. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21537

- Boudreaux, C. A., & Palmer, S. E. (2007). A charming little Cabernet: Effects of wine label design on purchase intent and brand personality. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 19(3), 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511060710817212

- Bruwer, J., Chrysochou, P., & Lesschaeve, I. (2017). Consumer involvement and knowledge influence on wine choice cue utilisation. British Food Journal, 119(4), 830–844. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2016-0360

- Bruwer, J., & Rueger-Muck, E. (2019). Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19(4), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358418781444

- Bruwer, J., Saliba, A., & Miller, B. (2011). Consumer behaviour and sensory preference differences: Implications for wine product marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111101903

- Calvo-Porral, C., Lévy-Mangin, J. P., & Ruiz-Vega, A. (2020). An emotion-based typology of wine consumers. Food Quality and Preference, 79, 103777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103777

- Calvo-Porral, C., Ruiz-Vega, A., & Lévy-Mangin, J. P. (2019). The influence of consumer involvement in wine consumption-elicited emotions. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 31(2), 128–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2018.1482587

- Calvo-Porral, C., Ruiz-Vega, A., & Lévy-Mangin, J. P. (2021). How consumer involvement influences consumption-elicited emotions and satisfaction. International Journal of Market Research, 63(2), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785319838747

- Celhay, F., & Remaud, H. (2018). What does your wine label mean to consumers? A semiotic investigation of Bordeaux wine visual codes. Food Quality and Preference, 65, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.10.020

- Charters, S., & Ali-Knight, J. (2002). Who is the wine tourist? Tourism Management, 23(3), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00079-6

- Charters, S., Lockshin, L., & Unwin, T. (1999). Consumer responses to wine bottle back labels. Journal of Wine Research, 10(3), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571269908718177

- Chi, C. G. Q., Ouyang, Z., Lu, L., & Zou, R. (2020). Drinking “green”: What drives organic wine consumption in an emerging wine market. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly.

- Chi, O. H., & Chi, C. G. (2022). Reminiscing other people’s memories: Conceptualizing and measuring vicarious Nostalgia Evoked by Heritage tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 33–49.

- Chylinski, M., Northey, G., & Ngo, L. V. (2015). Cross-modal interactions between color and texture of food. Psychology & Marketing, 32(9), 950–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20829

- Collins, R. P., Litman, J. A., & Spielberger, C. D. (2004). The measurement of perceptual curiosity. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(5), 1127–1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00205-8

- D’Amico, M., Di Vita, G., & Monaco, L. (2016). Exploring environmental consciousness and consumer preferences for organic wines without sulfites. Journal of Cleaner Production, 120, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.014

- Daume, J., & Hüttl-Maack, V. (2020). Curiosity-inducing advertising: How positive emotions and expectations drive the effect of curiosity on consumer evaluations of products. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1633163

- de Sousa, M. M., Carvalho, F. M., & Pereira, R. G. (2020). Colour and shape of design elements of the packaging labels influence consumer expectations and hedonic judgments of specialty coffee. Food Quality and Preference, 83.

- Dhar, R., & Kim, E. Y. (2007). Seeing the forest or the trees: Implications of construal level theory for consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70014-1

- d’Hauteville, F. (2003, July 26–27). The mediating role of involvement and values on wine consumption frequency in France. Colloquium in Wine Marketing, University of South Australia, Adelaide.

- Elliot, E., & Barth, J. (2012). Wine label design and personality preferences of millennials. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 21(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421211228801

- Ferdman, R. (2014). It’s official: Americans like red wine better than white wine. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/09/12/its-official-americans-like-red-wine-better-than-white-wine/

- Ferrarini, R., Carbognin, C., Casarotti, E. M., Nicolis, E., Nencini, A., & Meneghini, A. M. (2010). The emotional response to wine consumption. Food Quality and Preference, 21(7), 720–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2010.06.004

- Galati, A., Tinervia, S., Tulone, A., Crescimanno, M., & Rizzo, G. (2018). Label style and color contribution to explain market price difference in Italian red wines sold in the Chinese wine market. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 30(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2017.1402728

- Gmuer, A., Siegrist, M., & Dohle, S. (2015). Does wine label processing fluency influence wine hedonics? Food Quality and Preference, 44, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.03.007

- Goodman, S. (2009). An international comparison of retail consumer wine choice. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 21(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511060910948026

- Hansen, J. (2019). Construal level and cross-sensory influences: High-level construal increases the effect of color on drink perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(5), 890. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000548

- Hollebeek, L. D., Jaeger, S. R., Brodie, R. J., & Balemi, A. (2007). The influence of involvement on purchase intention for new world wine. Food Quality and Preference, 18(8), 1033–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.04.007

- Hosany, S., Martin, D., & Woodside, A. G. (2021). Emotions in tourism: Theoretical designs, measurements, analytics, and interpretations. Journal of Travel Research, 60(7), 1391–1407.

- Jang, S. S., & Namkung, Y. (2009). Perceived quality, emotions, and behavioral intentions: Application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model to restaurants. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.038

- Jaud, D. A., & Melnyk, V. (2020). The effect of text-only versus text-and-image wine labels on liking, taste and purchase intentions. The mediating role of affective fluency. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101964

- Jin, X., Wang, L., & Dong, H. (2016). The relationship between self-construal and creativity – regulatory focus as moderator. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.044

- Kansara, S. (2019). Exploring the wine sector in the Nashik district of India. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 32(2), 203–217.

- Karlsson, P., & Karlsson, B. (2021). Sauvignon Blanc: This multitalented, aromatic grape is growing in popularity. https://www.forbes.com/sites/karlsson/2021/04/12/sauvignon-blanc-this-multitalented-aromatic-grape-is-growing-in-popularity/?sh=2efdd31491a7

- Khalil, M., Northey, G., Septianto, F., & Lang, B. (2022). Hopefully that’s not wasted! The role of hope for reducing food waste. Journal of Business Research, 147, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.080

- Lee, H., Deng, X., Unnava, H. R., & Fujita, K. (2014). Monochrome forests and colorful trees: The effect of black-and-white versus color imagery on construal level. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(4), 1015–1032. https://doi.org/10.1086/678392

- Lesschaeve, I., & Bruwer, J. (2010). The importance of consumer involvement and implications for new product development. In S. S. Jaeger & H. MacFie (Eds.), Consumer-driven innovation in food and personal care products (pp. 386–423). Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition.

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (1998). The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.5

- Lick, E., König, B., Kpossa, M. R., & Buller, V. (2017). Sensory expectations generated by colours of red wine labels. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.07.005

- Lim, X. J., Ng, S. I., Chuah, F., Cham, T. H., & Rozali, A. (2019). How do consumers respond to fun wine labels? British Food Journal, 122(8), 2603–2619. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2019-0286

- Litman, J. A., & Jimerson, T. L. (2004). The measurement of curiosity as a feeling of deprivation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8202_3

- Lockshin, L., & Corsi, A. M. (2012). Consumer behaviour for wine 2.0: A review since 2003 and future directions. Wine Economics and Policy, 1(1), 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2012.11.003

- Lu, L., Rahman, I., & Chi, C. G. Q. (2016). Can knowledge and product identity shift sensory perceptions and patronage intentions? The case of genetically modified wines. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.10.010

- Lunardo, R., & Rickard, B. (2019). How do consumers respond to fun wine labels? British Food Journal, 122(8), 2603–2619. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2019-0286

- Mora, M., Urdaneta, E., & Chaya, C. (2018). Emotional response to wine: Sensory properties, age and gender as drivers of consumers’ preferences. Food Quality and Preference, 66, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.12.015

- Mueller, S., Lockshin, L., Saltman, Y., & Blanford, J. (2010). Message on a bottle: The relative influence of wine back label information on wine choice. Food Quality and Preference, 21(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2009.07.004

- Mueller, S., Remaud, H., & Chabin, Y. (2011). How strong and generalisable is the generation Y effect? A cross-cultural study for wine. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 23(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/17511061111142990

- Naylor, F. D. (1981). A state-trait curiosity inventory. Australian Psychologist, 16(2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050068108255893

- Neeley, C. R., Min, K. S., & Kennett-Hensel, P. A. (2010). Contingent consumer decision making in the wine industry: The role of hedonic orientation. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(4), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011052369

- Niimi, J., Danner, L., & Bastian, S. E. (2019). Wine leads us by our heart not our head: Emotions and the wine consumer. Current Opinion in Food Science, 27, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2019.04.008

- Northey, G., Chylinski, M., Ngo, L., & van Esch, P. (2018). The cross-modal effects of colour in food advertising: An abstract. Back to the Future: Using Marketing Basics to Provide Customer Value: Proceedings of the 2017 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference (pp. 683-684), Springer International Publishing.

- Parr, W. V., White, G., Heatherbell, K., & A, D. (2003). The nose knows: Influence of colour on perception of wine aroma. Journal of Wine Research, 14(2-3), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571260410001677969

- Pelegrín-Borondo, J., Olarte-Pascual, C., & Oruezabala, G. (2020). Wine tourism and purchase intention: A measure of emotions according to the PANAS scale. Journal of Wine Research, 31(2), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571264.2020.1780573

- Pelet, J. E., Durrieu, F., & Lick, E. (2020). Label design of wines sold online: Effects of perceived authenticity on purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102087

- Pourfakhimi, S., Nadim, Z., Prayag, G., & Mulcahy, R. (2021). The influence of neophobia and enduring food involvement on travelers’ perceptions of wellbeing – evidence from international visitors to Iran. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(2), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2391

- Reio, T. G., Jr., Petrosko, J. M., Wiswell, A. K., & Thongsukmag, J. (2006). The measurement and conceptualization of curiosity. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 167(2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.167.2.117-135

- Roe, D., & Bruwer, J. (2017). Self-concept, product involvement and consumption occasions: Exploring fine wine consumer behaviour. British Food Journal, 119(6), 1362–1377. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-10-2016-0476

- Santos, V. R., Ramos, P., & Almeida, N. (2017). The relationship between involvement, destination emotions and place attachment in the Porto wine cellars. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 29(4), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-04-2017-0028

- Scarpi, D. (2021). A construal-level approach to hedonic and utilitarian shopping orientation. Marketing Letters, 32(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-021-09558-8

- Song, J., & Qu, H. (2017). The mediating role of consumption emotions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.06.015

- Spence, C. (2015). Multisensory flavor perception. Cell, 161(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.007

- Spence, C., Levitan, C. A., Shankar, M. U., & Zampini, M. (2010). Does food color influence taste and flavor perception in humans? Chemosensory Perception, 3(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-010-9067-z

- Spence, C., & Velasco, C. (2018). On the multiple effects of packaging colour on consumer behaviour and product experience in the ‘food and beverage’ and ‘home and personal care’ categories. Food Quality and Preference, 68, 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.03.008

- Staub, C., Michel, F., Bucher, T., & Siegrist, M. (2020). How do you perceive this wine? Comparing naturalness perceptions of Swiss and Australian consumers. Food Quality and Preference, 79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103752

- Stillman, P., Lee, H., Deng, X., Unnava, H. R., & Fujita, K. (2020). Examining consumers’ sensory experiences with color: A consumer neuroscience approach. Psychology & Marketing, 37(7), 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21360

- Taylor, J. J., Bing, M., Reynolds, D., Davison, K., & Ruetzler, T. (2018). Motivation and personal involvement leading to wine consumption. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(2), 702–719. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2016-0335

- Teng, C. C., & Lu, C. H. (2016). Organic food consumption in Taiwan: Motives, involvement, and purchase intention under the moderating role of uncertainty. Appetite, 105, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.006

- Thach, L., & Camillo, A. (2018). A snapshot of the American wine consumer in 2018. https://www.winebusiness.com/news/?go=getArticle&dataId=207060

- Thach, L., Riewe, S., & Camillo, A. (2020). Generational cohort theory and wine: Analyzing how gen Z differs from other American wine consuming generations. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 33(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-12-2019-0061

- Thomas, V. L., & Vinuales, G. (2017). Understanding the role of social influence in piquing curiosity and influencing attitudes and behaviors in a social network environment. Psychology & Marketing, 34(9), 884–893. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21029

- Toteva, I. T., Lutz, R. J., & Shaw, E. H. (2021). The curious case of productivity orientation: The influence of advertising stimuli on affect and preference for subscription boxes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102677

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

- Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70013-X

- Ugalde, D., Symoneaux, R., & Rouiaï, N. (2022). French wine buyers’ expectations of an environmentally friendly wine. Journal of Wine Research, 33(4), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571264.2022.2143335

- Wang, B., Liu, S. Q., Kandampully, J., & Bujisic, M. (2020). How color affects the effectiveness of taste- versus health-focused restaurant advertising messages. Journal of Advertising, 49(5), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1809575

- Wiggin, K. L., Reimann, M., & Jain, S. P. (2019). Curiosity tempts indulgence. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(6), 1194–1212. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy055

- Yan, D., & Sengupta, J. (2011). Effects of construal level on the price-quality relationship: Table 1. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(2), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.1086/659755

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/208520