ABSTRACT

The statutory inclusion of modern foreign languages (MFL) into the Key Stage 2 curriculum in England in 2014 aimed to raise the language skills of younger learners in preparation for their secondary education. This change to the curriculum has occurred at a time in which the linguistic diversity within primary schools across the country has been consistently increasing. This study used interpretative phenomenological analysis to qualitatively examine the impact of the curriculum change on teachers implementing it in multilingual classrooms in Greater Manchester. Six teachers with varying experience in teaching MFL participated in semi-structured interviews focussing on different aspects of the curriculum change. This paper focuses on the teaching of MFL, as well as on teachers’ perceptions of English as an additional language (EAL) pupils’ aptitude for language learning in comparison to their monolingual peers. The superordinate themes identified from the data included the inconsistent delivery of MFL in primary schools, and the role of multilingual classrooms as opportunities for augmented MFL provision. The findings from this study will have implications for teachers, head teachers and policy-makers regarding the effectiveness of the initial implementation of MFL into the primary curriculum, with specific reference to the EAL school population.

Introduction

The statutory entitlement for all Key Stage 2 pupils (aged 7–11) to access modern foreign language (MFL) teaching was implemented in England in September 2014 (DfE Citation2013). With data collected two years after the curriculum change, this research qualitatively examines the experience of primary school teachers who were teaching MFL in the 2015/2016 academic year. Within the study, there is a special focus on those working in multilingual classrooms, as the introduction of language teaching in primary schools comes at a time in which the linguistic landscape of the country is becoming increasingly complex. Growing multilingualism, resulting from both mass migration and globalisation (Extra and Verhoeven Citation1998; Lin and Martin Citation2005), is reflected in the 20.6% of primary school pupils in England now speaking a language other than English at home (National Statistics Citation2017). Therefore, the inclusion of MFL in the primary curriculum adds a further linguistic dimension to the diverse makeup of contemporary English schools.

MFL teaching has been a traditional staple of secondary education for decades, with the most common languages taught in schools in England – French and Spanish – remaining consistently popular (Board and Tinsley Citation2014; DfE Citation2016). However, an overall decline in the popularity of language learning in secondary and post-compulsory education in England has been apparent since the beginning of the twenty-first century. This has raised concerns about the future of languages in education from both teaching professionals and politicians (Macaro Citation2008).

In response to such downward trends, the government’s National Languages Strategy, announced in 2002, ensured financial support was in place to promote and enhance language provision for children of all ages in England. For primary education, this resulted in the proportion of schools providing languages increasing from 22% to 92% between 2002 and 2008 (Wade, Marshall and O'Donnell Citation2009). Such figures suggest that the strategy had been successful in generating a solid base for the introduction of the 2014 statutory Key Stage 2 MFL entitlement.

In addition to the inclusion of foreign languages into the primary curriculum, the growth in the number of English as additional language (EAL) pupils has created further levels of linguistic and pedagogical complexity in the classroom. The achievement of EAL pupils attracts significant attention from academics and government departments, with considerable focus on outcomes in core subjects from Key Stage 2 SATs (standard achievement tests) and Year 11 General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) exams (Demie Citation2013). However, little research has been conducted on the attainment of EAL pupils in languages other than English and this is an area requiring further study. How teachers perceive the attainment and abilities of EAL pupils, compared to their monolingual peers, could also give researchers a useful insight into how this growing group of students is engaging with the curriculum (DeMulder, Stribling and Day Citation2014).

With interview data collected two years on from the inclusion of MFL in the primary curriculum, this paper evaluates the experiences of teachers delivering languages at Key Stage 2.

Our main research question is: how has the introduction of statutory modern foreign language teaching at Key Stage 2 impacted on teachers in multilingual classrooms? We address this question by focussing on two main areas:

Foreign language teaching in primary schools

A well-used argument for the introduction of languages into the curriculum at an early stage is the apparent enhanced capacity that younger children have for learning languages (Hunt et al. Citation2005). However, successful progression in the foreign language cannot be automatically assumed. It appears dependent on factors such as linguistic continuity in secondary education (Martin Citation2000), as well as other variables such as the length of exposure to the language, individual aptitude, teaching quality and motivation (Johnstone Citation2003).

One factor that influences the quality of teaching that children receive in MFL is the attitudes teachers hold regarding the subject and the role this plays in establishing an effective curriculum (Mellegard and Pettersen Citation2016), and the fact that many teachers do not attribute sufficient importance to languages, in a timetable that is already overloaded (McLachlan Citation2009).

Another important factor in the quality of the teaching relates to the lack of detail within the national MFL curriculum. The Key Stage 2 languages programme of study only sets out broad skills that should be focused upon (DfE Citation2013), and therefore teachers rely on ready-made schemes of work or internal planning when choosing topics that are appropriate for their MFL classes. A third factor that affects the quality of MFL teaching is the worrying lack of confidence amongst existing primary teaching staff regarding the pedagogical demands of MFL (Barnes Citation2006; Woodgate-Jones Citation2008).

To help address this issue, initial teacher training (ITT) centres across the UK began to offer an integrated MFL specialism into their courses (Woodgate-Jones Citation2008). For the one-year primary Post Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE), this has involved an optional 4-week placement overseas in a country using the target language which is not available to existing teachers.

In addition to teacher confidence, the impact of linguistic competence and teachers’ perceptions of their own language ability are dominant themes in past primary MFL research. From the outset, trainee teachers’ subject knowledge is the most influential factor on their subsequent confidence teaching MFL (Barnes Citation2006). For in-service teachers, the demographics of the school, and the burden of time needed to teach and plan for an additional subject, are additional obstacles (Legg Citation2013). Finally, the status given to MFL by the individual school is also a factor; without the support and enthusiasm of the management to provide training and resources, it is difficult for MFL to be truly integrated into the primary curriculum (Legg Citation2013).

EAL pupils and attainment

Although the current educational model in the UK promotes the integration of EAL pupils into the mainstream classroom (Edwards and Redfern Citation1992), the physical presence of a child in a lesson does not necessarily equate to equal access to the curriculum or to academic achievement (Franson Citation1999). Teachers’ perceptions of EAL pupils’ attainment and engagement with the education system are an important measure of how effective the syllabus is for a steadily growing group of children in the UK (Archer and Francis Citation2006). With one in five primary school children now speaking a different language at home than they do in school (National Statistics Citation2017), there is an inevitable impact on both teachers’ delivery of the curriculum (Butcher, Sinka and Troman Citation2007) and the attainment results on which pupils, teachers and schools are evaluated (Strand and Demie Citation2005).

Multilingualism, or proficiency in more than one language, is internationally gaining positive support and is viewed as an educational goal by many countries (McPake, Tinsley and James Citation2007). Yet, in McPake et al.’s (Citation2007) study, British teachers identified a lack of training and support for working with increasingly diverse groups of children from varied cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Thus, the challenges multiculturalism and multilingualism bring to the classroom appear to be a concern for educators (Theodorou Citation2011).

Past research into the attainment of EAL children in primary school has often focussed on their progression in English (Demie Citation2013), with attention paid to their advancement in reading and comprehension (Burgoyne, Whiteley and Hutchinson Citation2011), fluency in English (Demie Citation2013) and writing abilities (Cameron and Besser Citation2004). These studies advocate extra targeted support for children as soon as they embark on formal education to help them meet expected standards in English.

Research into the attainment of EAL pupils across the core subjects of English, maths and science at Key Stage 2 by Strand and Demie (Citation2005) found that EAL itself is not a clear indicator for achievement. However, the children’s level of fluency in English had a marked affect on results in Key Stage 2 assessments. Although children with developing fluency gained lower overall results, children with full fluency performed better and received higher test scores in all areas in comparison with their monolingual peers. This suggests that, given the heterogeneity of EAL pupils’ language profiles, studies with this group need more sophisticated analyses.

One area of the primary syllabus which has received little attention is how EAL pupils respond to a foreign language curriculum. Cross-linguistic research from Reder et al. (Citation2013) suggests that the metalinguistic awareness of children who speak more than one language is enhanced in comparison with monolingual children. This is further supported by third language (L3) research; with bilingual children out-performing monolingual counterparts (Cenoz Citation2013; Jessner Citation2008). However, this advantage has been debated, with other studies finding EAL children performing at an equal or lower level than their peers on metalinguistic tasks (Bialystok Citation2001; Simard, Fortier and Foucambert Citation2013). Therefore, although teachers may worry about EAL pupils coping with a new language before they have an adequate skill in English (Legg Citation2013), the possibility that their multilingualism could in fact equip them with the skills to excel as foreign language learners should be considered.

To summarise, the recent introduction of statutory MFL teaching for Key Stage 2 children comes at a time when the linguistic diversity of classrooms in England is increasing. The addition of MFL to the primary curriculum has placed increased demands on teachers who often have limited training in foreign language pedagogy and who may perceive themselves as underprepared to teach the subject through a lack of linguistic competence. The growing number of multilingual learners in primary schools adds further linguistic complexity to the MFL classroom. Although EAL pupil attainment in core subjects gains much attention, less is known about how they respond to the foreign language curriculum. Previous research indicates that speaking more than one language may confer advantages when it comes to learning other languages (Cenoz Citation2013), and therefore, MFL could provide an area of the curriculum where EAL pupils excel. With concurrent changes in cohort demographics and curriculum content, it is timely to address the research questions of this study:

How do teachers perceive MFL teaching in linguistically diverse schools?

What perceptions do teachers have regarding EAL pupils’ attainment and MFL learning?

Methods

Participants

Ethical approval was gained for the study through the University of Manchester’s research ethics committee. An online questionnaire was distributed to 25 teachers from schools across Greater Manchester, who responded to an invitation to participate. Sixteen teachers returned a signed consent form and completed the questionnaire in full. The questionnaire focused on four main areas: teacher experience, the pupil demographics within the school, the current MFL provision and ideas for MFL best practice. The questionnaire data were used to identify teachers to take part in the more in-depth interview. The inclusion criteria for involvement in the interviews were being involved in teaching MFL at Key Stage 2, and the presence of both EAL and monolingual children in the class cohort. Eight teachers met these criteria, but two did not consent to the interview component of the study, resulting in six participants. In this study, we focus only on the analysis of the interview data. The six teaching staff interviewed for the project are profiled in .

Table 1. Profiles of interviewed teaching staff.

Interviews

Prior to the interviews, the schedule was piloted with an experienced primary teacher who had been teaching MFL to their class for two years. This resulted in the order of some questions being changed and the removal of those questions that appeared repetitive (Turner Citation2010). The interviews were semi-structured, with the use of preliminary open-ended questions to allow the participants the opportunity to speak freely about the area of their teaching experiences they felt most comfortable with (Turner Citation2010). Subsequent questions focussed the interview more closely on specific areas. The six interviews conducted were all carried out within the workplace of each teacher and lasted between 38 and 62 minutes.

The audio recordings were transcribed by the first author using denaturalised transcription methods. During the transcription process, the data were anonymised and the use of vague descriptors for places and specific people ensured no individual could be recognised from the data.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)

IPA was chosen to analyse the data from the six semi-structured teacher interviews. The analysis technique addresses the idiosyncratic lived experience of an individual participant, using a social constructionist lens (Alvesson and Skoldberg Citation2010). The study’s focus on teachers’ personal experiences of curriculum change, and the implementation of MFL teaching, support the use of IPA as the method of analysis. During the interviews, participants verbalised their own practices and experiences while simultaneously interpreting them in relation to their personal and social domains (Smith and Osborn Citation2003). The researcher subsequently further interpreted the data provided by the teachers employing relevant analytical techniques. This resulted in a double hermeneutic perspective of the experience being developed (Brocki and Wearden Citation2006).

Due to the relatively recent introduction of the curriculum change involving MFL in primary schools in 2014, and the novelty of examining the position of EAL children within the MFL classroom, an inductive analysis grounded in the data was appropriate (Smith et al. Citation2002). Existing models regarding the introduction of primary MFL and the teaching of the subject in multilingual classrooms are being developed, but are both still under-researched, therefore there were insufficient theoretical frameworks available for a deductive analysis that could test a pre-determined hypothesis. Initially, the analysis involved immersion in the data on an individual case-by-case basis through multiple readings of the transcriptions. This was followed by the notation of exploratory comments regarding content, language and preliminary researcher interpretations of the transcripts (Smith et al. Citation2000). These preliminary notes were made on each text in isolation, without reference to the content of the other interviews.

Next, emergent sub-themes were identified through the application of a more psychological conceptualisation of the notes. This involved researcher interpretation and re-labelling of the initial notes to include formal linguistic terminology that encompassed the variations within the data, for example, labelling the ‘impact’ and ‘idiosyncrasies’ of MFL provision as well as highlighting the ‘dynamics’ that may be present in multilingual classrooms This resulted in a concise phrase being devised by the researcher which still reflected the participant’s account, yet was an interpretative result of the analysis (Pietkiewicz and Smith Citation2012). Once these sub-themes were completed, they were added to a theme log, with a short quotation from the transcripts as an example. Once all the interviews were completed and coded, the iterative analysis was conducted to identify common sub-themes between the participants. This was done by repeatedly combining similar themes and re-labelling them in order to reduce the total number, whilst still ensuring all the data were suitably represented by the theme name. We addressed the convergence and divergence within the sample as teachers had varying opinions and experiences encapsulated within the same theme (Smith Citation2011). By clustering sub-themes together, a number of superordinate themes were then identified, each containing related sub-themes. This process involved some overlapping sub-themes to be merged together, as well as the renaming of themes to ensure they suitably reflected the data collected from all six of the participants (Pietkiewicz and Smith Citation2012).

Results

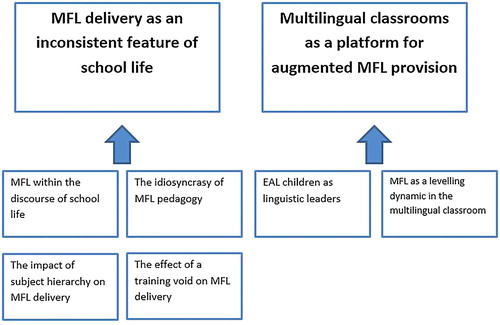

All six teachers perceived both positive and negative aspects of the curriculum change. Each teacher highlighted issues emphasising the inconsistencies surrounding the implementation of MFL, yet positive insights into the position of EAL children and the role of linguistic diversity in the MFL classroom were also presented. These components have been separated into two superordinate themes and a range of supporting sub-themes. The themes focussed on for this paper from the IPA of the interview data are shown in .

MFL delivery as an inconsistent feature of school life

The perceptions teachers have of how MFL fits into the overall primary curriculum appear to present the subject as inconsistent in both its delivery within schools and in relation to other subjects attributed greater priority.

MFL within the discourse of school life

The way MFL is discussed within the school environment and the position it holds in the discourse of each school can vary greatly. For Ruth, working at a school in a diverse but affluent area of Greater Manchester, MFL is enhanced through enrichment and actively encouraged through support from a dynamic parent and community voice:

I did a fiesta week, they helped loads at that. They came and offered their expertise … I had an au pair that came and we went round every class in the school and we taught them traditional Spanish nursery rhymes. (Ruth)

They wouldn’t see it. They wouldn’t know it was part of the curriculum … . They wouldn’t know they even did French. (Amy)

We don’t talk about French really. The transition things are just English and maths and any results. As we don’t have any tests in a different language … It isn’t something you would discuss, really. (Michelle)

Similarly, for Maria, the absence of MFL from the school discourse appears to stem from the allocation of a teaching assistant, rather than a teacher, to deliver the subject:

You know class assembly, and week after week, in literacy we have been learning, in numeracy we have been learning, in science we have been learning, and then that’s it. Because it’s what the teachers teach, … we won’t put Spanish in as that’s nothing to do with us. (Maria)

The idiosyncrasy of MFL pedagogy

The methods for teaching MFL to primary school children appear to have an impact on how the subject is perceived by both teachers and pupils. For Lucy, the pedagogical differences between language teaching and other subjects can raise barriers for subject delivery within a school:

One of the challenges about teaching it, is that it is not just like history … I’m not very good at history at all, but if I am planning a history unit I go and get a history book and I learn about it. But for me, it isn’t about how much language do they know by the end of year 6, it is about the language learning skills. And that is something that almost, unless you have been there and done that, you can’t teach it. (Suzie)

They are really upbeat about it and we have games and things to do. I don’t think they see it as an actual lesson, I don’t think they do as we don’t get books out and things. (Lucy)

I think it is just like that there is no pressure on them and we play games and things like that. In English and maths there isn’t a lot of time for playing games. (Michelle)

Every child, well I guess it is the way you teach it, loves doing it, they love learning languages, I’ve found. It’s the way you present it, it’s so different to other academic subjects. (Amy)

The impact of subject hierarchy on MFL delivery

Across all teachers, the low status of MFL within the hierarchy of subjects in the primary curriculum has an impact on its provision. For many teachers like Lucy, Michelle and Amy, it is perceived as ‘way down the list’ (Lucy) and is a dispensable subject which can easily be omitted from the timetable. Even with statutory entitlement status, MFL is not deemed equal to other subjects, partly because it is not assessed as other core subjects.

If you are having a busy week then it is just trying to fit it in desperately somewhere … .it is one of the things that they are not being assessed on or checked on, then it is one of the things that you can let slip. (Michelle)

It is definitely the first thing to drop off the timetable … they are very busy and you know there is a lot of pressure to focus on maths and English. It does seem to be the subject, along with say RE that does get forgotten about. (Amy)

I don’t know if it’s because I’m a TA or because it is a subject other people don’t have to teach or if people genuinely don’t believe it is as important as literacy and numeracy. (Maria)

I just don’t think it is of that level of importance to people in society for it to be of that level of importance for people in primary schools. (Suzie)

The effect of a training void on MFL delivery

The lack of opportunities to access suitable training was an issue raised by all teachers. The delivery of MFL appears to be negatively affected by the absence of developmental support. For those teachers confident in their linguistic competency, such as Michelle, there is a desire to access pedagogical training:

We’ve not had any meetings about it or training. I feel kind of prepared just because of my A level … . I would like to know more things about what I should be doing with them. You know, how do I go about teaching it? (Michelle)

They were showing us all different games and to be fair you’ve always seen the games before, because they do games everywhere. Every time you go on the course you think oh god, not that again. (Maria)

Multilingual classrooms as a platform for augmented MFL provision

All teachers highlighted the enhanced abilities of children with additional language learning experience within MFL lessons. Some acknowledged how MFL can offer pupils with limited English fluency an equal opportunity to engage with the curriculum.

EAL children as linguistic leaders

EAL children are highlighted as the prominent language learners within their cohort by Amy in a school context where their linguistic profile can often be a burden:

I think it is important to know that they are the language learners, aren’t they? They are the children who have got the talent … I think it’s nice for the children to recognise that because often it is the language barrier that holds them back. (Amy)

I feel like, from my perspective that those [EAL] children I have had have thrived in French and MFL because they can do it and they are doing it all the time so what’s another language? (Lucy)

I do think they pick it up quicker. And they have more of a go at pronunciation … .I think they are more confident. (Michelle)

I’ve noticed that because they are used to hearing different languages, my theory is that they pick up other languages quicker. I am quite convinced about it … They are used to hearing things as being different and so they tune in more. (Maria)

I think if they have got really good learning behaviour, they are in a really, really strong place to be excellent linguists. And be able to go from bilingual to multilingual in a really short number of steps. (Suzie)

MFL as a levelling dynamic in the multilingual classroom

For many teachers, teaching in a multilingual classroom presents them with the challenge of ensuring the curriculum can be accessed by all pupils, no matter their linguistic fluency in English. However, most of the teachers interviewed perceived the MFL classroom as a place where the dynamics were altered for EAL children and they had the equal access and engagement with the curriculum that is not always possible in other subjects.

I think it puts a lot of kids on a level playing field. They are all learning and it is not necessarily the ones who are good at numeracy or literacy that are on top table for those, that are the best speakers … .. It can be the EAL ones or the SEND [special educational needs and disabilities] ones. (Maria)

I think it might actually be those stronger ones who are a bit more wary of it, as it is like, oh this is something I don’t actually know. With the SEN [special educational needs] and EAL children, they are all starting at the same level. They all don’t know. (Michelle)

We are all using the same way of communicating, we aren’t having to go through Google Translate or anything else. So yeah, it is a huge leveller. And I think their attitude has been to get involved and have a go (Suzie)

It is a level playing field you know, in French … it is the way you teach it, isn’t it? It’s the enthusiasm and it is the fact we are all the same and everyone is having a go. (Amy)

Discussion

The IPA of the interview data has highlighted a number of novel points regarding teacher perceptions of teaching MFL in multilingual settings that could be developed in subsequent research and could ultimately assist teachers and managers with the future implementation of primary MFL.

The teaching of MFL in primary schools

The data suggest that the crowded curriculum in primary schools appears to have had a universally negative impact on MFL provision. All teachers interviewed perceived the subject as one which is overshadowed by other priorities within the school and is therefore often absent from discussions in day-to-day school life, as well as from the overarching educational discourse. This perception of ‘overcrowding’ is well represented in the literature (Legg Citation2013; McLachlan Citation2009) and may well be further exacerbated by teacher perceptions of their current workload. 93% of teachers in 2016 reported that excessive workload was a serious problem in their school (Higton et al. Citation2017). Therefore, it seems likely that the introduction of an additional, non-externally assessed subject, in which most teachers have limited training or experience (Woodgate-Jones Citation2008), will be avoided in favour of the core, assessed subjects such as English and maths. From 2014, the increased focus on core-subject summative assessment in the primary phase is reflected in the amount of the weekly timetable dedicated to these subjects (Harlen Citation2014) with a further risk that assessment preparation will add to their pre-eminence (Torrance Citation2007). The importance attributed to these subjects by external agencies could be a significant factor which prevents the consistent presence of languages in the classroom (Wyse, McCreery and Torrance Citation2008).

A consequence of the prominence of core subjects is the low status attributed to MFL within the hierarchy of class subjects. Although parental and academic support for primary MFL has been recorded in the past (Nuffield Foundation Citation2000), it could be that this approval in principle is not strong enough to push the subject into the educational fore. Although the majority of teachers interviewed displayed positive support for MFL, which aligns with previous work by Hunt et al. (Citation2005), the impact of sampling bias within this study must be considered. The linguistic competency and managerial responsibilities present in the sample may not be representative of the general teaching population, with colleagues not sharing the same commitment to the subject. Most of the teachers interviewed had access to a community of practice, a vital tool for building confidence and promoting subject engagement (Jones and Coffey Citation2017), or alternatively, had the strong linguistic competence to support their teaching (Woodgate-Jones Citation2009). In contrast, the interview data regarding the regular omission of MFL from the weekly timetables by their colleagues suggest that primary language learning is often viewed as dispensible and is attributed little value within the hierarchy for those without such support. This perspective supports the previous findings of McLachlan (Citation2009) regarding teacher outlook on primary languages and the lack of importance and esteem teachers hold for the subject.

The challenges the subject faces, if it is to be viewed as more than a low-status, peripheral extra for students, must be addressed at both a national and local level. Effective and enthusiastic leadership with investment in suitable training appears paramount if primary MFL is to transition into a mainstay of the curriculum (Board and Tinsley Citation2014; Legg Citation2013). If managerial teams were prompted by national initiatives to perceive MFL as integral to primary school education, as is the case for the promotion of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects by the Primary Science Quality Mark®, teachers might be more motivated to engage with the subject and deliver higher quality, consistent teaching. Furthermore, the utilisation of the wider school community such as teaching assistants, parents and governors to promote languages through events or the management of specific projects may also help to lift the subject’s standing (Jones and Coffey Citation2017). However, for many schools, it seems that only those subjects that are currently included in national attainment figures can be afforded sufficient time and commitment in the timetable (Wyse, McCreery and Torrance Citation2008).

The perceived pedagogical difference between MFL and other primary subjects appears to be both a strength and weakness for the subject. Teachers appear to see a need to utilise alternative and additional skills in order to deliver quality language teaching, and for many, this is a daunting prospect (Board and Tinsley Citation2014; Maynard Citation2012). The concerns of non-specialist staff regarding the demands of acquiring any language-specific pedagogical skills could be expected, given the time required to develop these skills (Woodgate-Jones Citation2009), and the current workload of staff (Higton et al. Citation2017). Although links between MFL teaching practices and other subjects, such as literacy, have been made (Maynard Citation2012), teachers appear aware of a uniqueness within MFL teaching that they may not feel prepared for due to a possible lack of linguistic competence as well as the more ludic nature of many MFL activities. Therefore, support from leadership teams and CPD opportunities are paramount (Barnes Citation2006; Legg Citation2013). Furthermore, by more effectively integrating MFL into the curriculum and encouraging a whole-school approach to languages with increased cross-curricular learning, for example, the anxiety experienced by teachers could be reduced (Barnes Citation2015; Jones and Coffey Citation2017). Without such support, the perceived ‘idiosyncratic’ pedagogy may continue to alienate teachers and prompt them to avoid the subject, further reducing the standing of MFL in primary school life. As Jones and Coffey (Citation2017) note:

Although the data suggest that teachers perceive MFL as a subject that requires alternative pedagogical tools when compared to other lessons, it may be that a lack of guidance and certainty as to what constitutes appropriate pedagogy for primary MFL (Macaro and Mutton Citation2009) is the real issue; with clearer guidance being called for at a national level (Cable et al. Citation2010). However confidence in teaching MFL can be improved if it is planned for as robustly and cohesively as other subjects. MFL pedagogy would benefit from exploiting cross-curricular and cross-linguistic opportunities offered by the SPaG (Spelling, punctuation and grammar) English curriculum, possibly from Key Stage 1.

Although teachers may retreat from the teaching practices of language learning, the data support studies, such as that by Bolster, Balandier-Brown and Rea-Dickens (Citation2004), that the opposite is true for primary school pupils, who instead display considerable enthusiasm for the subject. Active participation, communicative pedagogies and opportunities for group work are now promoted in the foreign language classroom (Kramsch Citation2014; Richards and Rodgers Citation2014), and the findings here suggest that this engages children and places MFL more favourably within the syllabus for them. The altered pedagogy offers pupils valuable opportunities to communicate with peers that may be absent in other subjects (Maynard Citation2012). This view is supported by studies into teaching instruction across primary schools, with McNess et al. (Citation2001) suggesting that collaborative work and interactive activities are rare in core subjects and that assessment can often overshadow important formative learning. Although inclusive differentiation for MFL is still in its infancy for many primary MFL teachers (Beltran, Abbott and Jones Citation2013), the communicative focus of the subject may offer an opportunity for schools to engage all pupils, in particular, those who may not excel in the less communicative environments of some of the other lessons. If inferior language provision is delivered, or the subject omitted altogether, schools may miss out on this opportunity to develop the skills of those pupils for whom traditional pedagogy can be a barrier to learning.

EAL children and primary MFL

Interviewees repeatedly suggested that EAL children have a predilection for language learning that is less apparent in their monolingual peers. All teachers were able to give examples of children being better equipped for the MFL classroom and attributed this to their multilingual background. As experienced language learners, EAL children may be equipped with linguistic knowledge that gives them an advantage in MFL (Maluch, Neumann and Kempert Citation2016). If this translates to an increased confidence in the foreign language classroom and encourages a positive emotional attitude to the subject, this may boost their language learning ability (MacIntyre and Gregerson Citation2016). In contrast, if monolingual children feel a sense of anxiety in the MFL lesson, possibly due to their accessibility to the class content being diminished by the use of the target language (Meiring and Norman Citation2002), research suggests their attainment in MFL will also be reduced (Dewaele et al. Citation2017). Therefore, the EAL cohort may well have a notable lead in the subject that teachers can easily identify.

However, teacher use of the target language in many MFL lessons may not be consistent or significant (Chambers Citation2016) and therefore any levelling effect created by linguistic accessibility may not fully explain such increased confidence and subsequent improved performance in EAL pupils. Alternatively, it could be that the motivation for learning a new language and the value attributed to language learning is heightened in communities in which multilingualism is the norm (Canagarajah Citation2007). In monolingual English-speaking households and across English society, a lack of confidence and competence in foreign languages may result in pupils not attributing any sense of importance to the subject and therefore not engaging sufficiently with the lesson content (Coleman Citation2009). In addition, the small amount of time given to the subject in English primary schools may reinforce this notion that it is not a priority for pupils (Macaro Citation2008) and success in the subject is not necessarily advantageous.

Although motivation and positive affect towards the subject may account for a proportion of the findings in this study, previous research focussing on bilingual children learning a third language (L3) suggests a number of alternative explanations for a perceived EAL pupil advantage in MFL. Firstly, as EAL children have existing knowledge of at least two languages when they approach their MFL studies, they are able to draw on a broader repertoire of linguistic skills as they learn (Cenoz Citation2013). The advantages may come in the form of more accurate pronunciation through phonological or prosodic similarities between the languages spoken (Gut Citation2010), or from a wider lexicon that can assist in the decoding and learning of new vocabulary (Cenoz and Todeva Citation2009). Cross-linguistic transfer of morphology and syntax: - for example, the notion of grammatical gender which is non-existent in English, could also assist in L3 learning (Mahbube and Aliakbar Citation2014), alongside heightened sensitivity to pragmatic cues that could help in foreign language communication (Soler Citation2012). These linguistic advantages, however, may be reliant on the languages involved being closely related, in order for the full benefits to be gleaned by the learner (Jarvis and Pavlenko Citation2008); this linguistic relationship may not be present for many EAL pupils learning French or Spanish in school.

If, as the participants in this study perceive, EAL children do perform better in MFL than their monolingual peers, it may be due to a potential development of enhanced metalinguistic awareness, which gives them a greater ability to manipulate and control language (Cenoz Citation2013; Galambos and Goldin-Meadow Citation1990). Jessner (Citation2014) suggests that this awareness is vital for the development of multilingualism and the successful learning of additional languages. Research in this area has produced mixed findings (Bialystok Citation2001; Bruck and Genesee Citation1995; Reder et al. Citation2013; Simard, Fortier and Foucambert Citation2013) with an overarching conclusion that metalinguistic benefits may be limited to those with a more balanced bilingual profile (Bialystok Citation2001). It should also be considered that the extent of any metalinguistic advantage may again be determined by the specific home language of the individual child. Cross-linguistic similarities between the L1 and the MFL in pronunciation, spelling and word order could significantly aid comprehension (Ringbom Citation2007). The proximity and characteristics of the languages may play a vital role in how the languages interact (Jessner, Megens and Graus Citation2015) and on how successful the learner is in the target foreign language (Reder et al. Citation2013).

EAL children may also come to the MFL classroom with a more active learning approach paired with a stronger realisation that language is a system to be utilised for communication (Naiman et al. Citation1996), and may be more likely to approach foreign language learning in metacognitive ways that are different from monolinguals (Jessner Citation2008). Those with prior language learning experience will also adapt the strategies they use more effectively (Thomas Citation1992) and show more self-direction in doing so (Bowden et al. Citation2005). Such approaches may well account for the teacher observations of linguistic leadership in EAL pupils.

Nevertheless, there is great diversity within the EAL population of English schools (NALDIC Citation2016) with many children possessing varying degrees of fluency in the languages they use (Strand and Demie Citation2005). For some, there may be little literacy instruction in their home language which could hinder their written skills in the MFL (Maluch, Neumann and Kempert Citation2016). Furthermore, the advantages found in some studies with bilingual participants may be constrained in English EAL cohorts due to the socio-economic background of many pupils (Cenoz Citation2013), as well as by their absence from formal education during periods of migration (Strand Citation1999). As suggested by Jessner (Citation2014) there appears to be a need for further research with multilingual children from lower socio-economic status families.

Conclusions and recommendations

Although the perception of a unique language teaching pedagogy can deter some staff from delivering MFL, the perceived ‘idiosyncratic’ style of language lessons can engage a wide range of pupils, including those who may find the traditional methods of core subjects difficult to access. The positive response from children at Key Stage 2 towards MFL may act as a motivator for teachers to engage with it. However, further training and curriculum guidance may be needed to ensure teachers feel confident when teaching the subject. With limited space in the timetable to deliver MFL, pedagogical and linguistic confidence seems vital for ensuring staff are able to meet the challenges of teaching primary languages and consequently ensure the subject is well integrated into primary education. .

Furthermore, MFL classes could offer EAL children improved opportunities to access the curriculum through a reduction in the linguistic barriers that may often hinder their attainment. This levelling effect promotes high levels of participation in lessons from EAL pupils and the interactive pedagogy encourages involvement. Moreover, EAL children are regularly perceived by teachers as linguistically more capable than their monolingual peers due to their exposure to multiple languages and this may be linked to improved learning strategies and enhanced metalinguistic abilities.

Further consideration needs to be given by teachers, leadership teams and policy-makers regarding how to utilise MFL pedagogy effectively in increasingly diverse English schools. Research is needed to empirically address whether EAL children have the perceived enhanced metalinguistic skills and awareness which could see them excelling in MFL. By exploring how EAL children may differ from their monolingual counterparts in the way they approach and react to MFL provision, there could be an opportunity to develop a curriculum that caters well for the diversity within multilingual classrooms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alvesson, M. and K. Skoldberg. 2010. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Archer, L. and B. Francis. 2006. Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement: Race Gender, Class and ‘Success’. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Barnes, A. 2006. Confidence levels and concerns of beginning teachers of modern foreign languages. The Language Learning Journal 34: 37–46.

- Barnes, J. 2015. Cross-Curricular Learning 3–14. London: Sage.

- Beltran, E.V., C. Abbott and J. Jones. 2013. Inclusive Language Education and Digital Technology. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Bialystok, E. 2001. Bilingualism in Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Board, K. and T. Tinsley. 2014. Language Trends 2013/14: The State of Language of Language Learning in Primary and Secondary Schools in England. Reading: CfBT Education Trust.

- Bolster, A., C. Balandier-Brown and P. Rea-Dickens. 2004. Young learners of modern foreign languages and their transition to the secondary phase: a lost opportunity? The Language Learning Journal 30: 35–41.

- Bowden, H.W., C. Sanz and A. Stafford. 2005. Individual differences: age, sex, working memory and prior knowledge. In Mind and Context in Adult Second Language Acquisition, ed. C. Sanz, 105–140. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Brocki, J.M. and A.J. Wearden. 2006. A critical evaluation of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) in health research. Psychology and Health 21: 87–108.

- Bruck, M. and F. Genesee. 1995. Phonological awareness in young second language learners. Journal of Child Language 22: 307–324.

- Burgoyne, K., H.E. Whiteley and J.M. Hutchinson. 2011. The development of comprehension and reading-related skills in children learning English as an additional language and their monolingual, English-speaking peers. British Journal of Educational Psychology 81: 344–354.

- Butcher, J., I. Sinka and G. Troman. 2007. Exploring diversity: teacher education policy and bilingualism. Research Papers in Education 22: 483–501.

- Cable, C., P. Driscoll, R. Mitchell, S. Sing, T. Cremin, J. Earl, I. Eyres, B. Holmes, C. Martin and B. Heins. 2010. Languages Learning at Key Stage 2: A Longitudinal Study. Nottingham: DfES Publications.

- Cameron, L. and S. Besser. 2004. Writing in English as an Additional Language at Key Stage 2. Nottingham: DfES Publications.

- Canagarajah, S. 2007. Lingua franca English, multilingual communities and language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal 91: 923–939.

- Cenoz, J. 2013. The influence of bilingualism on third language acquisition: focus on multilingualism. Language Teaching 46: 71–86.

- Cenoz, J. and E. Todeva. 2009. The well and the bucket: the emic and etic perspectives combined. In The Multiple Realities of Multilingualism, eds. E. Todeva and J. Cenoz, 265–292. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Chambers, C. 2016. Pupils’ perceptions of Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 transition in modern foreign languages. The Language Learning Journal 44: 1–15.

- Coleman, J.A. 2009. Why the British do not learn languages: myths and motivation in the United Kingdom. The Language Learning Journal 37: 111–127.

- Demie, F. 2013. English as an additional language pupils: how long does it take to acquire English fluency? Language and Education 27: 59–69.

- DeMulder, D.K., S.M. Stribling and M. Day. 2014. Examining the immigrant experience: helping teachers develop as critical educators. Teaching Education 25: 43–64.

- Dewaele, J., J. Witney, K. Saito and L. Dewaele. 2017. Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: the effect of teacher and learner variables. Language Teaching Research 21: 1–22.

- DfE. 2013. Languages Programmes of Study: Key Stage 2. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-languages-progammes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-languages-progammes-of-study#key-stage-2-foreign-language (accessed 13 February, 2018). Crown Copyright.

- DfE. 2016. Get into Teaching, June 10. www.gov.uk: https://getintoteaching.education.gov.uk/explore-my-options/teach-languages.

- Edwards, V. and A. Redfern. 1992. The World in a Classroom: Language in Education in Britain and Canada. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Extra, G. and L. Verhoeven. 1998. Immigrant minority groups and immigrant minority languages in Europe. In Bilingualism and Migration, eds. G. Extra and L. Verhoeven, 3–29. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Franson, C. 1999. Mainstreaming learners of English as an additional language: the class teacher's perspective. Language, Culture and Curriculum 12: 59–71.

- Galambos, S.J. and S. Goldin-Meadow. 1990. The effects of learning two languages on metalinguistic awareness. Cognition 34: 1–56.

- Gut, U. 2010. Cross linguistic influence in L3 phonological acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism 7: 19–38.

- Harlen, W. 2014. Assessment, Standards and Quality of Learning in Primary Education. York: Cambridge Primary Review Trust.

- Higton, J., S. Leonardi, N. Richards, A. Choudhoury, N. Sofroniou and D. Owen. 2017. Teacher Workload Survey 2016. London: DfE.

- Hunt, M., A. Barnes, B. Powell, G. Lindsay and D. Muijs. 2005. Primary modern foreign languages: an overview of recent research, key issues and challenges for educational policy and practice. Research Papers in Education 20: 371–390.

- Jarvis, S. and A. Pavlenko. 2008. Cross-linguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jessner, U. 2008. Teaching third languages: findings, trends and challenges. Language Teaching 41: 15–56.

- Jessner, U. 2014. On multilingual awareness or why the multilingual learner is a specific language learner. In Essential Topics in Applied Linguistics and Multilingualism, eds. M. Pawlak and L. Aronin, 175–184. London: Springer International Publishing.

- Jessner, U., M. Megens and S. Graus. 2015. Cross linguistic influence in third language acquisition. In Crosslinguistic Influnce in Second Language Acquisition, ed. R. A. Alonso, 193–214. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Johnstone, R. 2003. Enabling change. CILT ITT Conference, Cambridge.

- Jones, J. and S. Coffey. 2017. Modern Foreign Language 5-11: A Guide for Teachers. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kramsch, C. 2014. Teaching foreign languages in an era of globalization: an introduction . The Modern Language Journal 98: 296–311.

- Legg, K. 2013. An investigation into teachers’ attitudes towards the teaching of modern foreign languages in the primary school. Education 3–13 41: 55–62.

- Lin, A. and P.W. Martin. 2005. Decolonisation, Globalisation: Language in Education Policy and Practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Macaro, E. 2008. The decline in language learning in England: getting the facts right and getting real. The Language Learning Journal 36: 101–108.

- Macaro, E. and T. Mutton. 2009. Developing reading achievement in primary learners of French: inferencing strategies versus exposure to ‘graded readers’. The Language Learning Journal 37: 165–182.

- MacIntyre, P. and T. Gregerson. 2016. Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 2: 193–213.

- Mahbube, T. and J. Aliakbar. 2014. Cross-linguistic influence in the third language (L3) and fourth language (L4) acquisition of the syntactic licensing of subject pronouns and object verb property: a case study. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning 3: 29–42.

- Maluch, J.T., M. Neumann and S. Kempert. 2016. Bilingualism as a resource for foreign language learning or language minority students? empirical evidence from a longitudinal study during primary and secondary school in Germany. Learning and Individual Differences 51: 111–118.

- Martin, C. 2000. An Analysis of National and International Research on the Provision of Modern Foreign Languages in Primary Schools. London: QCA.

- Maynard, S. 2012. Teaching Foreign Languages in the Primary School. Abingdon: Routledge.

- McLachlan, A. 2009. Modern languages in the primary curriculum: are we creating conditions for success? The Language Learning Journal 37: 183–203.

- McNess, E., P. Triggs, P. Broadfoot, M. Osborn and A. Pollard. 2001. The changing nature of assessment in English primary classrooms: findings from the PACE project 1989–1997. Education 3–13 29: 9–16.

- McPake, J., T. Tinsley and C. James. 2007. Making provision for community languages: issues for teacher education in the UK. Language Learning Journal 35: 99–112.

- Meiring, L. and N. Norman. 2002. Back on target: repositioning the status of target language in MFL teaching and learning. The Language Learning Journal 26: 27–35.

- Mellegard, I. and K.D. Pettersen. 2016. Teachers’ response to curriculum change: balancing internal and external change forces. Teacher Development 20: 181–196.

- Naiman, N., M. Frohlich, H. Stern and A. Todesco. 1996. The Good Language Learner. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- NALDIC. 2016. The EAL Learner, December 22. https://naldic.org.uk/the-eal-learner/.

- National Statistics. 2017. Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics: January 2017. London: Department for Education.

- Nuffield Foundation. 2000. Languages: The Next Generation. London: The Nuffield Foundation.

- Pietkiewicz, I. and J.A. Smith. 2012. A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne 18: 361–369.

- Reder, F., N. Marec-Breton, J. Gombert and E. Demont. 2013. Second language learners’ advantage in metalinguistic awareness: a question of languages’ characteristics. British Journal of Educational Psychology 83: 686–702.

- Richards, J.C. and T.S. Rodgers. 2014. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ringbom, H. 2007. Cross-Linguistic Similarity in Foreign Language Learning. Cleveland: Multilingual Matters.

- Simard, D., V. Fortier, and D. Foucambert. 2013. Measuring metasyntactic ability in among heritage language children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 19–31.

- Smith, J.A. 2011. Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychology Review 5: 9–27.

- Smith, J.A., S. Michie, A. Allanson and R. Elwy. 2000. Certainty and uncertainty in genetic counselling: a qualitative case study. Psychology and Health 15: 1–12.

- Smith, J.A., S. Michie, M. Stephenson and O. Quarrell. 2002. Risk perception and decision making in candidates for genetic testing in Huntington’s disease: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology 7: 131–144.

- Smith, J.A. and M. Osborn. 2003. Interpretative phenomenological analysis . In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, ed. J. A. Smith, 53–80. London: Sage.

- Soler, E.A. 2012. Teachability and bilingualism effects on third language learners’ pragmatic knowledge. Intercultural Pragmatics 9: 511–542.

- Strand, S. 1999. Ethnic group, sex and economic disadvantage: associations with pupils’ educational progress from baseline to the end of Key Stage 1. British Educational Research Journal 25: 179–202.

- Strand, S. and F. Demie. 2005. English language acquisition and educational attainment at the end of primary school. Educational Studies 31: 275–291.

- Theodorou, E. 2011. ‘Children at our school are integrated. No one sticks out’ Greek-Cypriot teachers’ perceptions of integration of immigrant children in Cyrpus. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 24: 501–520.

- Thomas, J. 1992. The role played by metalinguistic awareness in second and third language learning. In Cognitive Processing in Bilinguals, ed. R. Harris, 531–545. Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Torrance, H. 2007. Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 14: 281–294.

- Turner, D.W. 2010. Qualitative interview design: a guide for novice investigators. The Qualitative Report 15: 754–760.

- Wade, P., H. Marshall and S. O'Donnell. 2009. Primary Modern Foreign Languages: Longitudinal Survey of Implementation of National Entitlement to Language Learning at Key Stage 2. London: Department for Education.

- Woodgate-Jones, A. 2008. Training confident primary modern foreign language teachers in England: an investigation into preservice teachers’ perceptions of their subject knowledge. Teaching and Teacher Education 24: 1–13.

- Woodgate-Jones, A. 2009. The educational aims of primary MFL teaching: an investigation into the perceived importance of linguistic competence and intercultural understanding. The Language Learning Journal 37: 255–265.

- Wyse, D., E. McCreery and H. Torrance. 2008. The Trajectory and Impact of National Reform: Curriculum and Assessment in English Primary Schools. Cambridge: The Primary Review.