ABSTRACT

Validation of data collection instruments is a necessary step in all research and should be regarded as an integral component in every stage of the research process; however, the validation process is often not accounted for in detail in published studies. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development and validation of the Ungspråk electronic questionnaire, which was designed to explore teenagers’ multilingualism and multilingual identity in the Norwegian school context. It aims to examine whether having a multilingual identity correlates with several variables such as language practices, languages studied in school, open-mindedness, and beliefs about multilingualism. To our knowledge, the Ungspråk questionnaire is one of the first validated tools for quantitatively investigating learners’ multilingual identity in school settings. Different qualitative and quantitative procedures were adopted for validating Ungspråk, including piloting sessions with students from two lower secondary schools. The results of the validation processes suggest that the Ungspråk questionnaire is a robust instrument for investigating young learners’ multilingual identity. It is easy to use, acceptable to learners, and fulfils stringent criteria of reliability and validity.

Introduction

Validity is at the same time one of the most important and contentious concepts in academic research, a fact supported by the multitude of theoretical and methodological approaches dedicated to it. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary (Citation2020) defines the word valid as denoting something that is ‘well-grounded or justifiable […] at once relevant and meaningful’, ‘logically correct’ and ‘appropriate to the end in view’. The aptness of these attributes to define high-quality academic research attest to why validity is something to be strived for. What seems open to dispute are the means used to validate a research study or, in other words, how one justifies the appropriateness of the research methods and instruments and how they lead to meaningful and well-grounded results.

The authors of this article consider validity as an integral component of all stages of a research process. Therefore, it should be accounted for in the purposes of a study, in the design of the research instruments and methods for collecting data and answering research questions, and in the ethical principles guiding the relationship between researchers, participants, collaborators and the research community.

In this article, we provide an account of the quantitative and qualitative procedures adopted in the validation of the questionnaire Ungspråk.Footnote1 The questionnaire is the main quantitative component of the Ungspråk project (2018–2022), a longitudinal mixed methods study that uses a combination of instruments for data collection and methodologies of analysis to investigate multilingualism and multilingual identity in Norwegian secondary schools (Haukås et al. Citation2021). Due to the prevalence of socio-constructivist views in language and identity research (Block Citation2013), qualitative methodologies have become more common in research on multilingualism and multilingual identity (see, e.g. Duff [Citation2015] for an overview of relevant studies). However, we see it beneficial to collect and analyse both qualitative and quantitative data on the phenomena under focus. Combining results from quantitative and qualitative research on multilingual identity may provide valuable and complementary insights to the research field (Monrad Citation2013; Kroger Citation2007).

By offering a narrative of the development of a questionnaire aimed at investigating young learners’ multilingualism and multilingual identity, we aspire to show how validity can be best understood as an iterative and cumulative process in which specific methodological procedures (such as face, content and construct validity) are not just isolated, one-time measures but relate and contribute to the overall quality of the study. From this perspective, even the writing of an academic paper is seen as part of the validation process, since it is not a neutral account of events but a ‘literary technology designed to persuade readers of the merits of a study’ (Sandelowski and Barroso Citation2002). Furthermore, research papers are usually the only means audiences have to ‘understand the ground on which a study was undertaken, the means and methods adopted to realize the findings’ (Lincoln Citation2001: 25) and, therefore, to assess its validity and relevance for future research.

To our knowledge, the Ungspråk questionnaire is one of the first validated quantitative research instruments designed specifically for studying multilingual identity in an educational context. The paper starts with an introduction to multilingualism and multilingual identity in the Norwegian educational context, followed by an overview of the theoretical framework that supports our research. After presenting our international partners in the project, the text focuses on the development of the electronic version of our research instrument and the challenges involved in designing a questionnaire to young learners. Particular attention is paid to specific procedures aimed at strengthening the overall validity of the questionnaire, such as expert reviews, translation and piloting. Next, we provide a detailed description of each section of the questionnaire, placing particular emphasis on how relevant theoretical concepts were operationalised.

Setting up the context and the theoretical framework for the development of the Ungspråk questionnaire

The increasingly diverse makeup of contemporary societies, and consequently of classroom environments, have promoted a dramatic shift in language learning and teaching. More and more, the knowledge of foreign languages, coupled with the ability to understand different cultures, are seen as crucial resources in preparing citizens for the global challenges of the twenty-first century. These demands are reflected, for instance, in institutional discourses and documents (Council of Europe Citation2001, Citation2018; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training [NDET] Citation2017) and in the need for pedagogies that harness the potentials of linguistic and cultural diversity in the language classroom (Cenoz Citation2017; Hu Citation2018).

These societal shifts have engendered an impressive amount of research focusing on multilingualism in education. One aspect that remains under-researched, however, is the relationship between having a multilingual identity and its implications for language learning and teaching. The Ungspråk project seeks to address this gap by investigating multilingualism and multilingual identity in Norwegian secondary schools (see Haukås et al. [Citation2021] for a detailed discussion of the whole research project). In the next sections, we provide an overview of multilingualism in the Norwegian educational context and explain the importance of the concept of multilingual identity to our research.

Multilingualism in Norway

Norway can be considered a multilingual country for several reasons. It has two official languages, Norwegian and Sami. Sami is a group of indigenous languages spoken and taught in northern Scandinavia. The two written variants of Norwegian, Nynorsk and Bokmål, are both taught as compulsory school subjects. Bokmål is currently the most frequently preferred language, with 85% of first graders learning it (NDET Citation2018). Nynorsk is mainly chosen by school children living primarily in western rural areas (Vangsnes Citation2018). However, all pupils learn both variants starting in school year 8. Furthermore, dialects are highly valued, and schoolchildren are encouraged to speak their local dialects in and out of class (Kulbrandstad Citation2018). Norwegians are also able to understand their neighbouring languages, Danish and Swedish, a common phenomenon in Scandinavia known as receptive multilingualism (Cenoz Citation2013; Zeevaert Citation2007).

English as a foreign language is taught from year 1 of regular schooling and when students start lower-secondary school (school year 8), about 75–80% opt for taking another foreign language; predominantly Spanish, German or French (Norwegian National Centre for Foreign Languages in Education Citation2020). In the past decades, this unique linguistic scenario has been enriched even further by a host of immigrant languages such as Polish, Lithuanian, Somali and Arabic (Statistics Norway Citation2020). The value of Norway’s rich linguistic diversity for its citizens is emphasised in several white papers, such as in the Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education and training (NDET Citation2017):

Knowledge about the linguistic diversity in society provides all pupils with valuable insight into different forms of expression, ideas and traditions. All pupils shall experience that being proficient in a number of languages is a resource, both in school and society at large.

The second reason is more general and relates to the ambivalent meaning of the term ‘multilingual’ (flerspråklig) in Norwegian educational contexts. Haukås (CitationForthcoming) suggests that the word flerspråklig is often exclusively employed to refer to children and adults with immigrant backgrounds who struggle to learn Norwegian, therefore having a negative connotation. However, Sickinghe (Citation2016) found that teenagers in upper-secondary school in Norway have a much more nuanced and flexible understanding of the concept. This finding is of particular relevance to our study in lower secondary school, an age range which has so far been neglected in this kind of research.

The concept of multilingual identity as a defining element of the Ungspråk project

Even though all schoolchildren in Norway can be considered multilingual (Haukås CitationForthcoming), this does not necessarily mean that their language knowledge, practices and beliefs correspond to their self-perceptions as multilinguals. Following Fisher et al. (Citation2018), we distinguish between linguistic identity and multilingual identity in the context of this study. According to Fisher et al. (Citation2018), the former refers to ‘the way one identifies (or is identified by others) in each of the languages in one’s linguistic repertoire’ (1). So, for instance, the fact that an individual deliberately stresses (or hides) distinctive phonological features of her local variant or dialect in an interaction might be revealing of that person’s negotiation of her linguistic identity. In this sense, linguistic identity is interpreted in poststructuralist terms as situated, contextual, fluid and dynamic.

Multilingual identity, on the other hand, refers to one’s explicit self-identification as multilingual ‘precisely because of an awareness of the linguistic repertoire one has’ (Fisher et al. Citation2018: 2). In addition to poststructuralist attributes of linguistic identity, this notion reflects a psychological theoretical perspective on identity and relates to a core identity, that is, a ‘temporary fixed’ sense of what one is (Block Citation2013: 18). As emphasised by Fisher et al. (Citation2018: 3), this core identity develops over time and connects one’s past, present and future (possible) images of oneself, thus providing guidance for actions and interpretations of experience. This understanding of multilingual identity as a temporary fixed phenomenon that can be connected with other factors has a direct bearing on the longitudinal, mixed methods design of the Ungspråk project and particularly on the construction of the Ungspråk questionnaire.

Several researchers (Fisher et al. Citation2018; Henry Citation2017; Henry and Thorsen Citation2018; Ushioda Citation2017) point out that the awareness and self-identification as a multilingual individual can be a potentially significant factor in the maintenance and development of the languages an individual already knows and in the effort and investment placed in learning new languages. In addition, some scholars consider multilingual identity as a holistic phenomenon, which can be related to and have an influence on other dimensions of identity, such as beliefs, attitudes, and personal life scenarios (Aronin Citation2016; Busse Citation2017). Fisher et al. (Citation2018) and Pavlenko (Citation2006) also suggest that a positive self-identification as multilingual can be empowering.

Multilingual identity and its connection to other factors

The researchers in the Ungspråk team adopt a holistic approach to multilingualism and are interested both in the language-learning implications of having a multilingual identity and in its relationship to other ‘cognitive, societal and personal aspects’ (Aronin Citation2019b: 9). Consequently, the Ungspråk questionnaire explores several aspects that can contribute to a better understanding of pupils’ multilingualism and multilingual identity. In what follows, we present some of these aspects and discuss the theoretical orientations that support them.

Language use habits. As mentioned earlier, the language habits of a multilingual individual do not necessarily correspond to her self-identification as multilingual. In order to enquire into the relationship between multilingual identity and language learning, it is crucial to have a mapping of the languages known and used by participants, both at school and beyond. Knowing the purposes and contexts in which a language is used and the speaker’s attitudes towards that particular language provide researchers with valuable information not just about that individual language per se. More importantly, they offer a broad picture of the interplay among the language resources an individual has and the communicative, cognitive and identity purposes they serve (Aronin Citation2019b). In the section that presents the final version of the questionnaire, we describe in detail how a mapping of participants’ language habits was obtained.

Student’s beliefs about multilingualism. Our interest in looking into possible correlations between having a multilingual identity and students’ beliefs about multilingualism is due to the general scarcity of research that takes into account the participants’ beliefs on the latter topic. Scholars have repeatedly pointed to several advantages of multilingualism, for example, higher cognitive flexibility, creativity, and better episodic and semantic memory compared with monolinguals (for an overview of general cognitive advantages see Antoniou Citation2019; Bialystok Citation2011; Leivada et al. Citation2020). Positive effects of multilingualism on additional language learning have also been documented in several studies. Above all, multilinguals seem to have an increased metalinguistic awareness, and they show better developed metacognitive skills related to using language learning strategies (Jessner Citation2008; Kemp Citation2007). In addition to cognitive effects, scholars emphasise positive economic effects of multilingualism and increased empathy/intercultural competence (Bel Habib Citation2011; Dewaele and Wei Citation2012). It should be noted, however, that scholars have also failed to demonstrate cognitive advantages in multilinguals in several studies and the debate is still ongoing (Antoniou Citation2019; Bialystok Citation2011; Leivada et al. Citation2020).

Yet, the abundance of research on the benefits of multilingualism stands in contrast with the rare studies on pupils’ beliefs about multilingualism, especially considering the direct implications they may have for language learning outcomes. For example, whereas positive beliefs about multilingualism may spark interest in investing time and effort in the learning process, negative beliefs may hinder students seeing the relevance of being multilingual, resulting in decreased motivation.

Future multilingual self. The third focus derives from recent research in the field of language learning motivation (Busse Citation2017; Henry Citation2017; Henry and Thorsen Citation2018; Ushioda Citation2017). Research in this field uses the concept of the future/ideal multilingual self to refer to a particular aspect of multilingual identity, i.e. learners’ future-oriented self-conception as speakers or users of multiple languages, and investigates the effects this image can have on students’ motivation in language learning. Scholars argue that in the contemporary world where English language has a dominant status as a global language and significantly shapes learners’ language choices, the ideal multilingual self may have a powerful effect on students’ motivation in learning languages other than English. However, even though researchers believe that a future oriented image of oneself as a multilingual speaker can have a significant potential for research, empirical studies that explore this aspect of identity are still rare.

Open-mindedness. Our interest in the correlation between a multilingual identity and open-mindedness is sparked by the growing emphasis on the role of intercultural competence in foreign language education. This trend is reflected, for example, in the new Norwegian curriculum for foreign languages which highlights fostering intercultural competence as one of the most important aims of the subject (NDET Citation2019). In research and assessment instruments, intercultural competence is often associated with learners’ open, unprejudiced and positive attitudes towards diversity, which can be unified under the term open-mindedness. A number of studies indicate that open-mindedness can be positively connected to one’s multilingualism (Dewaele and Van Oudenhoven Citation2009; Dewaele and Wei Citation2012). Other scholars (e.g. Mellizo Citation2017; Ruokonen and Kairavuori Citation2012) also show that pupils’ positive attitudes and emotions towards cultural differences, among other factors, can be correlated to their language repertoires and language learning. Stemming from the above research, the Ungspråk questionnaire investigates whether and to what extent a multilingual identity is connected to learners’ open-mindedness as a significant indicator of intercultural competence development.

Other significant variables. In order to broaden the scope of analysis and strengthen our findings, the Ungspråk questionnaire collects data on a number of other variables that might be associated with self-identification as multilingual, such as attitudes towards the languages pupils know, gender, immigration background, school grades, travel experience, experience of living abroad, friends’ language repertoires, and parents/carers’ education. In addition, we are interested in investigating if being a user of the written variety of Norwegian used by most Norwegians (Bokmål) or a user of Nynorsk, which is only chosen by a minority (12%) (Vangsnes Citation2018) correlates differently with pupils’ multilingual identity.

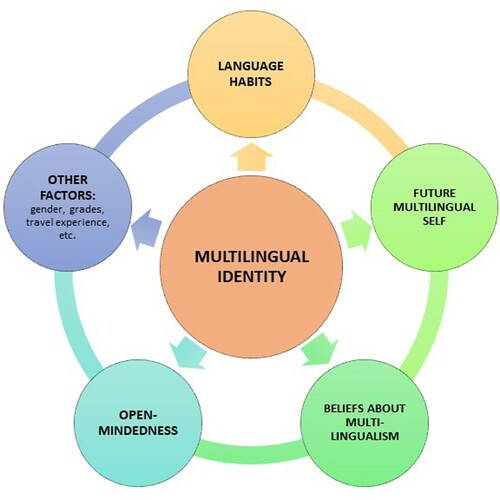

provides a visual representation of the centrality of the concept of multilingual identity in the Ungspråk questionnaire and how it is investigated in relation to other variables. It also shows how other variables might be interrelated.

Developing and validating the Ungspråk questionnaire: describing the process

Our starting point

The Ungspråk research project is made up of a team of multilingual researchers with a broad range of language learning and teaching experiences in different contexts across the world. For successful innovation as a team, it was deemed vital that enough time was spent for all members to develop a strong sense of ownership of the research project. To achieve this and to transform heterogeneity into common understanding and innovation, we adopted frequent meetings with open, inclusive and reflective discussions (Drach-Zahavy and Somech Citation2001; El Ayoubi Citation2001). Consequently, the Ungspråk questionnaire had a long maturational period and was developed over a period of eight months (August 2018 – April 2019).

Our international partners in the project belong to the MEITS group at the University of Cambridge. MEITS (Empowering Individuals, Transforming Societies) is an interdisciplinary research project funded under the AHRC Open World Research Initiative. Strand 4 of the project, which sought to answer the question ‘What is the relationship between multilingual identity and language learning?’, developed a questionnaire to be used for collecting data among lower secondary school pupils in England about their multilingual identity and several other variables such as language habits, motivation, and achievement. In order to compare pupils’ multilingual identity and related variables across contexts (England and Norway), the MEITS paper-and pencil survey was used as a starting point for developing the Ungspråk questionnaire (see also Forbes et al. Citation2021).

However, for theoretical and practical reasons, it soon became clear that the Ungspråk questionnaire needed to depart from the MEITS questionnaire in multiple ways. The most obvious practical reason had to do with the adaptation of the general content to the context of Norwegian lower secondary schools. The main theoretical reasons involved developing a questionnaire that suited our specific research interests and was appropriate to provide answers to our research questions. For example, whereas MEITS takes a special interest in pupils’ use of metaphors when describing their language learning, the Ungspråk questionnaire places a stronger emphasis on pupils’ beliefs about multilingualism, their future multilingual selves and open-mindedness. Nevertheless, several similarities remain, providing valuable possibilities for comparisons across contexts.

As mentioned earlier, creating a valid questionnaire is a cumulative process that requires various developmental steps and considerations. In our case, several theoretical discussions over an extended period resulted in an agreement on the main research objectives for the project and which theories to draw on, as presented in the first section of the paper. Based on our theoretical framework, we thereafter created a full draft of the questionnaire. Subsequently, we invited a number of experts from the field (MEITS collaborators, local experts in multilingualism and research design, and language teachers) to critically examine the appropriateness of the questionnaire for examining pupils’ multilingual identity and related variables. More specifically, the experts were asked to consider its conciseness, clarity and adequacy. The feedback from the experts cannot be underrated, as it in multiple ways challenged the research team to clarify their objectives and to improve the contents of the questionnaire. Visits from researchers of the MEITS team (August and November 2018) were especially relevant, as they could share their experiences and provide our team with useful insights and comments. Summing up, the final version of the questionnaire is the result of several rounds of theory-driven discussions both in the Ungspråk team as well as with experts from various fields and professions. In what follows, we discuss some of our considerations during the process. These are related to developing questionnaires for young people and to the design and use of an electronic version.

Considerations when designing a questionnaire for young people

When designing a questionnaire, one should never lose sight of the audience it is intended for and strive not only ‘for a psychometrically reliable and valid instrument but also for an intrinsically involving one’ (Dörnyei and Taguchi Citation2010, 77). Consequently, creating a questionnaire that looks relevant and is engaging to the participants is a crucial step in validation, since ‘questionnaires tend to fail because participants don't understand them, can't complete them, get bored or offended by them, or dislike how they look’ (Boynton Citation2004: 1372).

Several steps were taken to ensure that the Ungspråk questionnaire was engaging, clear and meaningful to the participants. First, once the first draft of the questionnaire was ready, four language teachers with many years of experience working with our target age group were asked to review its contents. They carefully read through the questionnaire, keeping the clarity of the instructions in mind and considering if all formulations were understandable and would feel relevant for lower secondary school pupils. Overall, the language teachers approved of the questionnaire’s structure and content for the target group.

In addition, one lower secondary school pupil was recruited to complete the questionnaire while being recorded. The think-aloud protocol took place in November 2018 and the volunteer was asked to explain how he understood the instructions and statements and to provide reasons for his responses when answering the questionnaire. The analysis of the think-aloud protocol proved helpful in spotting ambiguous formulations resulting in the rewording of one instruction, two questions and one statement.

Since the Ungspråk questionnaire is available in two languages (Norwegian and EnglishFootnote2), translation, an often-neglected aspect of questionnaire development (Dörnyei and Taguchi Citation2010: 48), was a crucial component in the questionnaire. English was the language used in the research group meetings and in the subsequent development of the questionnaire. After the review of the first final draft of the questionnaire in English, four collaborators were recruited to work individually on the translation of the Ungspråk questionnaire into Norwegian. All of them had previous teaching experience, two were currently doing a Ph.D. in a similar field at the time and one had expertise in developing questionnaires. Three of them were speakers of Norwegian as a first language and highly proficient in English. One was a native speaker of English and highly proficient in Norwegian. The four versions were compared with the translation by the research team and, in each case, the most frequently suggested version was chosen. The team of experts were also asked to look for ambiguities and to estimate if learners would understand and answer the questions appropriately.

One final comment should be made about the perceived appropriateness of the questionnaire to participants. Taking into consideration the context of administration (i.e. classrooms) and the usual association questionnaires have with testing in educational environments, it was essential that we made it clear to the students that the Ungspråk questionnaire was not a test. This was mentioned explicitly in the information letter read to the participants in class and implicitly in the opening instructions to the questionnaire. Thus, one of the threats to validity, evaluation apprehension, was minimized (Rosenberg et al. Citation1969).

The rationale for using an e-questionnaire

Besides favouring participants’ engagement with the questionnaire, given the appeal digital technologies usually have among teenagers, the decision to use a digital format also had several additional advantages. First, all pupils in Norway have laptops for use in the classroom, thus making the data collection process faster, although technical problems are always a potential risk. The digital format also facilitated the logistics of administration, since data were collected in the classrooms via group administration, which allows for large amounts of data to be collected in a single session with a guaranteed high-response rate (Dörnyei and Taguchi Citation2010: 68).

The Ungspråk questionnaire was developed on SurveyXact, the leading survey tool in Scandinavia. Technical support and occasional meetings with SurveyXact staff were important to improve the questionnaire in terms of clarity of instructions, readability, consistency of style and formatting.

Some features of the online version of the questionnaire include an image related to teenage life and a completion bar at the top of the pages, to make the visual layout more appealing and to encourage participants to continue to answer ().

Piloting and data collection: practical procedures

In November 2018 the research project, including the questionnaire and information letters in Norwegian and English, was submitted for ethical assessment to the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD). In early February 2019, the research team started contacting prospective schools for carrying out the piloting of the questionnaire. If the school accepted the invitation, a copy of the information letter with details about the project was forwarded to parents. Two schools of the same size and from similar socio-economic areas agreed to take part in the first and the second piloting of the questionnaire. School 1 had 118 participants and school 2 had 116 participants.

Data collection for all sessions, including piloting, took place at the participant schools during class hours. In every session, at least one researcher was present to guide and aid participants in the completion of the questionnaire. Researchers also took notes in loco and immediately after the sessions, to register factual information and practical problems arising during data collection and to have a systematic record of observations to triangulate with the data from the questionnaire.

In class, each student was handed a copy of the letter (in English or Norwegian, according to their language choice) and the class teacher was asked to read the version in Norwegian to the whole class. Even though parents had been sent the invitation letter well in advance, we wanted to make sure that all students were duly informed about the project. Particular emphasis was placed on voluntary participation in the research and if a student opted for not answering the questionnaire, they were assigned another activity by the class teacher. Refusal rate remained at 1.7%.

To ensure anonymity and to increase participants’ willingness to answer potentially sensitive questions (Schnell et al. Citation2010), we asked the pupils to generate their own identification code based on the first two letters of the month in which they were born and the four last digits of their mobile phone numbers, assuming that all lower secondary school students own a mobile phone. In this way, the code was known to the pupils and could be used in a second round of data collection in school year ten.

Experts generally agree that the time of completion for a questionnaire should not exceed thirty minutes (Dörnyei and Taguchi Citation2010: 12). Taking into consideration our respondents’ age group (13–14 years) and the length of one teaching unit (60 min), the questionnaire was designed to have an estimated response time of 20 min. However, depending on the number of languages listed by the participants and the length of their responses to some open-ended statements, the response time varied between 15 and 35 min.

The final version of the questionnaire

In the following discussion, our focus is on how the theoretical constructs related to multilingualism and multilingual identity were operationalised in the questionnaire. Where appropriate, the results of statistical tests, such as exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA), are provided. These statistical procedures were run to test how well the measured variables represent the suggested theoretical constructs, or in other words, ‘the extent to which an instrument measures what it is intended to measure’ (Tavakol and Dennick Citation2011: 53).

The final version of the questionnaire consists of four main sections. Having pupils’ self-identification as multilingual at the centre of inquiry in section 3, the other sections provide important insights into which variables correlate with pupils’ multilingual identity. It is important to emphasise that the words ‘multilingual’ and ‘multilingualism’ (respectively, ‘flerspråklig’ and ‘flerspråklighet’ in Norwegian) are not mentioned in any part of the questionnaire until respondents get to section 3, where they are asked to complete the prompt ‘to be multilingual means … ’. The reason for this is that previous references to the terms might have influenced the pupils’ own definitions and their following explanations to why they consider themselves multilingual or not. However, this consideration does not guarantee that the students’ awareness of their multilingual identity may not have been influenced by the first sections of the questionnaire. In what follows, we present the contents of each section and discuss how they connect to and are informed by relevant theory.

Section 1: multilingual habits

As Norwegian classrooms become increasingly linguistically and culturally diverse, there is a growing need to find out more about the linguistic repertoires, the contexts and the purposes of language use and the roles played by languages in pupils’ lives. Drawing on theories of learners’ dominant language constellations (Aronin Citation2019a), the first section of the questionnaire consists of statements related to pupils’ language use habits. Participants are first asked to tick the languages they have as school subjects. For each of these languages the digital questionnaire generates a total of eleven statements. The first statement asks participants how many years they have known the language in question. The remaining statements are answered by ticking ‘yes’ or ‘no.

The second statement in the series is ‘this is my first/native language’. Besides providing indirect information about the students’ family background, the statement allowed students to say which and how many language(s) they regard as their first ones. The next five statements refer to the contexts the language is used and include sentences like ‘I use this language to speak to (some of) my friends’ and ‘I (sometimes) use this language when I go on holiday’. The last four are attitudinal statements for each reported language: ‘I am proud that I know this language’, ‘I avoid using this language’, ‘I think I know this language well’, and ‘It is important for me to know this language’ (see Supplemental data). In this way, we not only map the patterns of use, but also examine how learners’ language practices relate to emotions, self-efficacy, and perceived importance.

Taking pupils’ own perceptions of what it means to know a language as a starting point, they are next encouraged to include all other languages they feel they know. Each of these self-reported languages generates the same eleven statements described in the previous paragraph. As pupils’ multilingual identity may be correlated with parents/caretakers’ and friends’ multilingualism, the last part of section 1 asks the participants to list languages their parents/caretakers and friends know. The mapping of pupils’, parents’ and friends’ languages also allows the research team to study whether knowing certain languages (i.e. European or Norway’s most common immigrant languages) is more closely correlated with a multilingual identity than others.

Section 2: beliefs about multilingualism, future multilingual self and open-mindedness

The second section of the Ungspråk questionnaire aims to examine to what extent students’ self-identification as multilingual correlates with their beliefs about multilingualism, future multilingual self and open-mindedness. It consists of 25 attitudinal statements that were designed and adapted based on the theoretical approaches and empirical studies presented in the first part of this article. After the two piloting sessions, statistical analysis, performed with EFA and CFA as interconnected procedures (Gerbing and Hamilton Citation1996), helped us group the statements into the three main constructs discussed below (see Supplemental data) and to verify a goodness of fit of the suggested model.

Each statement is followed by a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. We decided to use ‘not sure’ as the middle option rather than ‘neither agree nor disagree’ to avoid the common problem of how to interpret the midpoint (Nadler et al. Citation2015). Although analysing the midpoint is often challenging, we decided against a four-point, forced choice Likert scale since pupils may never have reflected on some of the statements before and, consequently, may genuinely be unsure of what to answer.

The construct Beliefs About Multilingualism (BAM) has eight statements. Three statements are related to cognitive advantages associated with multilingualism found in previous research, such as higher intelligence (statement 2), creativity (statement 3) and flexibility (statement 8) (Antoniou Citation2019; Bialystok Citation2011). Two of the statements are related to increased language awareness, stating that being multilingual facilitates further language learning (statement 1), and increases one’s cross-linguistic awareness (statement 5) (Jessner Citation2008; Kemp Citation2007). Two statements are concerned with economic (statement 4) and general academic (statement 6) benefits, whereas statement 7 derives from research suggesting multilinguals show signs of being more empathetic than others (Bel Habib Citation2011; Dewaele and Wei Citation2012).

The construct Future Multilingual Self (FMS) is composed of seven statements. Four of them were designed based on Henry & Thorsen’s questionnaire (Citation2018) and reflect one’s self-image as a multilingual person in the future (statements 9–13). The other two statements (14 and 15) are related to one’s attitudes towards the knowledge of multiple languages. It is worth mentioning that the statements allow differentiating students’ future self-images as users of multiple languages versus users of only Norwegian and English. We consider this distinction important due to the specifics of the Norwegian context, where Norwegian and English are compulsory school subjects, whereas learning additional languages is not.

The third construct, Open-mindedness (OPM), consists of ten statements, which were developed based on an overview of several questionnaires, including the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (Van der Zee et al. Citation2013) and the Intercultural Development Inventory (Hammer et al. Citation2003). The statements are designed to measure how open and unprejudiced respondents are when encountering people who may have different worldviews, opinions and lifestyles.

After the first pilot an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on the varimax rotation method was applied to clarify whether the statements represent the corresponding constructs. EFA was performed in SPSS version 25. The rotated factor matrix showed that the statements comprise three main factors, which correspond to the initial constructs FMS, BAM, and OPM. Cronbach’s alpha correlation coefficient was used to measure the internal consistency, i.e. the reliability, of each construct (Drost Citation2011). Cronbach's Alpha of the constructs was 0.65 for FMS, 0.73 for BAM, and 0.65 for OPM.

Before a second piloting of the questionnaire items that showed a poor correlation and, thus, did not load well on these three constructs, were reformulated or replaced. This was the case for 13 statements from the first pilot. The CFA performed with the data from the second pilot confirmed that the items now had stronger factor loadings compared with the first version of the questionnaire. Cronbach’s Alpha for the components after the second pilot was 0.75 for FMS, 0.72 for BAM and 0.75 for OPM. These values suggest that the three constructs are reliable measures of pupils’ beliefs about multilingualism, future multilingual self and open-mindedness. However, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability test showed a poor correlation of some statements to the other items in a construct. In these cases, we considered each statement separately and decided on whether it should be included into the final version of the questionnaire or not. Overall, we had four problematic statements: ‘The more languages you know, the easier it is to learn a new language’ (0.46) and ‘The person I would like to be in the future speaks English very well’ (0.38), related to the constructs BAM and FMS respectively; and ‘There are different ways of being Norwegian’ (0.38) and ‘It would be better if all people in Norway shared the same opinions’ (0.49), related to OPM. The values of these statements were lower than the selection criterion (<0.5). However, due to their moderate divergence, which is sometimes found in questionnaires containing subjective assessments (Prudon Citation2015), we kept these statements in the questionnaire as we were interested in studying the particular aspects of students’ beliefs about multilingualism, future multilingual self and open-mindedness that they help examine. Furthermore, the results of Cronbach alpha analysis showed that the exclusion of these statements would not improve the overall validity of the constructs. More details about this section and to what extent the constructs correlate with other variables can be found in forthcoming publications.

Section 3: Pupils’ definitions of multilingualism and their multilingual identity

Whereas the first two sections do not mention the term ‘multilingualism’ or ‘being multilingual’, Section 3 asks the pupils to define being multilingual by completing the sentence ‘Being multilingual means … ’. In this way, the pupils’ own definitions of multilingualism are taken as starting points and not the various scholarly definitions existing in the field. After having completed the sentence, the participants are asked the following question: ‘Are YOU multilingual?’ and given the alternatives yes/no/not sure. Thereafter, they are asked to explain their choice.

This section can be regarded as the heart of the questionnaire since it provides data for the main dependent variable and collects rich textual data to complement the quantitative findings. First results from analysing the data from this section can be found in Haukås (CitationForthcoming). In addition, the answers to this section will be used as input to develop one of the research components in the next phase of the Ungspråk project, namely interactive sessions with participants. In these sessions, students will be presented with their answers from Section 3 of the questionnaire and have the opportunity to discuss and reflect on them. Besides improving the overall quality and validity of the findings, the interactive sessions will address an important ethical issue in research in education: the fact that participant students are not usually invited to interact with and give feedback on the data they help generate (Pinter Citation2014). Another benefit of this approach is that all participants involved (students, teachers and researchers) might gain a more nuanced and elaborate understanding of what it means to be multilingual. A detailed discussion on the design and implementation of the interactive sessions and their ethical, epistemological and pedagogical implications can be found in Haukås et al. (Citation2021).

Section 4: biographic information

In addition to investigating variables directly related to language learning, our research questions also look into whether having a multilingual identity can be correlated to other factors such as gender, school grades and time spent abroad. Consequently, the final part of the questionnaire consists of factual questions about these topics. This also includes asking for information about pupil’s first-choice form of Norwegian (Bokmål or Nynorsk), in order to examine possible differences between these two groups, where Nynorsk users may be regarded as a minority group in the Norwegian multilingual context. In addition, the pupils are invited to add any comments on the questionnaire or on language learning in general before submitting the questionnaire.

Discussion

Creating a valid questionnaire cannot and should not be reduced to the statistical components concerned with construct validity or reliability. Instead, the validity process starts as soon as researchers decide on the need for investigating a given phenomenon. The two main objectives of this article were to present a new questionnaire, Ungspråk, aimed at exploring secondary school students’ multilingualism and multilingual identity, and to describe the several validation procedures adopted during the process of its development.

During the initial process, it is vital that the researchers involved reach a mutual understanding of which questions to be asked and which theoretical framework to base the contents of the questionnaire on given the multitude of theories of and approaches to multilingualism and multilingual identity in our field. This admittedly time-consuming process is perhaps particularly important when researchers from different countries, and with different linguistic repertoires, experiences and belief systems get together to create a new project, as was the case in the Ungspråk project. At the same time, this diversity is extremely valuable for critically examining own beliefs and practice shifts of perspectives, which we believe ultimately leads to higher quality research outcomes (El Ayoubi Citation2001). For example, our various conceptualisations of multilingualism needed to be clarified and also how ‘multilingual identity’ could be defined and meaningfully explored in a questionnaire study with young participants.

Just as important as reaching a mutual understanding within the research group is to actively seek feedback from experts outside of the group. When developing our questionnaire, we relied on the expertise of other researchers in the field, language teachers, professional questionnaire developers, a think aloud protocol with a pupil, translators, and ultimately the analysis of collected data from two pilots. All these steps helped us in creating a valid tool for examining pupils’ multilingual identity, multilingual habits and other related variables.

In this paper, we wanted to provide readers with details of the developmental process that can be useful when adapting the questionnaire to other contexts. However, when using a research tool, it is vital to always consider its validity in each particular context, as no language learning takes place in a vacuum (Hofstadler et al. Citation2020). Language learning in school, for example, is part of an education system and is dependent on a range of factors at national and institutional levels that may influence how and how often languages are taught, how languages are valued, who decides to study multiple languages and the expectations of the participants. Likewise, language learning and use outside of school are influenced by factors such as language status, the degree of multilingualism in a given society and who is referred to as being multilingual. As mentioned earlier, two main objectives of the Ungspråk study are to collect students’ own definitions of what it means to be multilingual and, based on students’ own definitions, ask them if they identify as multilingual. Given that the word ‘flerspråklig’ (multilingual) is frequently employed in public debates in Norway to refer exclusively to people with immigrant backgrounds (Haukås CitationForthcoming), we wanted to avoid any use of the term until those questions were asked in the third section of the questionnaire. Consequently, we needed to take the Norwegian context into consideration when structuring the questionnaire, something which may not be necessary in other contexts.

Conclusion

The results of the validation processes suggest that the questionnaire Ungspråk is an appropriate instrument for investigating young learners’ multilingual identity and related factors such as their language habits, beliefs about multilingualism, open-mindedness and future multilingual selves. Based on our observations during data collection in piloting schools, the questionnaire is easy to use and acceptable to learners. Furthermore, it fulfils stringent criteria of reliability and validity. However, the Ungspråk questionnaire can also be applied as an awareness-raising tool for teachers and students in the language classroom across contexts. By exploring and discussing the answers to the questionnaire, both teachers and students may broaden their perspectives on how multilingualism is perceived and practiced by young people and who may identify as being multilingual. They may also get new ideas on how multilingualism can be conceptualised and used as a valuable resource in the classroom.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The compound noun Ungspråk consists of the words ‘ung’ (young), and ‘språk’ (language(s)). In Norwegian, ‘språk’ is both the singular and plural form of the noun and thus may refer to one or several languages. The choice for a non-transparent word alludes to the linguistic diversity of the learners and the possibility of their self-identification as monolingual or multilingual. The questionnaire is available as Additional Material.

2 Considering that English is taught since year 1 of regular schools in Norway, we decided to include it as an option for answering the questionnaire for students who wanted to challenge themselves by answering in English. Furthermore, for some newly arrived students and depending on their language backgrounds, English could be easier for them to understand. Nevertheless, most students decided to answer in Norwegian.

References

- Antoniou, Mark. 2019. The advantages of bilingualism debate. Annual Review of Linguistics 2019, no. 5: 395–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011820.

- Aronin, Larissa. 2016. Multi-competence and Dominant Language Constellation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Multicompetence, ed. Vivian Cook, and Li Wei, 142–163. Cambirdge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aronin, Larissa. 2019a. Dominant Language Constellation as a method of research. In International Research on Multilingualism: Breaking with the Monolingual Perspective, ed. Eva Vetter, and Ulrike Jessner, 13–26. Cham: Springer.

- Aronin, Larissa. 2019b. What is multilingualism? In Twelve Lectures in Multilingualism, ed. David Singleton, and Larissa Aronin, 3–34. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Bel Habib, Ingela. 2011. Multilingual skills provide export benefits and better access to new emerging markets. Sens public, October, 17. http://sens-public.org/articles/869/ (accessed 28 August, 2020).

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2011. Reshaping the mind: the benefits of bilingualism. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale 65, no. 4: 229–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025406.

- Block, David. 2013. Issues in language and identity research in applied linguistics. ELIA. Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada [Applied English Linguistics Studies] 2013, no. 13: 11–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.12795/elia.2013.i13.01.

- Boynton, Petra M. 2004. Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire. Bmj 328, no. 7452: 1372–1375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1372.

- Busse, Vera. 2017. Plurilingualism in Europe: Exploring attitudes toward English and other European languages among adolescents in Bulgaria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain. The Modern Language Journal 101, no. 3: 566–582. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12415.

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2013. Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33: 3–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S026719051300007X.

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2017. Translanguaging in school contexts: International perspectives. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16, no. 4: 193–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1327816.

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1bf.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment . Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989.

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc, and Jan Pieter Van Oudenhoven. 2009. The effect of multilingualism/multiculturalism on personality: No gain without pain for Third Culture Kids? International Journal of Multilingualism 6, no. 4: 443–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710903039906.

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc, and Li Wei. 2012. Multilingualism, empathy and multicompetence. International Journal of Multilingualism 9, no. 4: 352–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2012.714380.

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, and Tatsuya Taguchi. 2010. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing. New York: Routledge.

- Drach-Zahavy, Anat, and Anit Somech. 2001. Understanding team innovation: The role of team processes and structures. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 5, no. 2: 111–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.5.2.111.

- Drost, Ellen A. 2011. Validity and reliability in Social Science research. Education Research and Perspectives 38, no. 1: 105–123. URL: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=491551710186460;res=IELHSS.

- Duff, Patricia A. 2015. Transnationalism, multilingualism, and identity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35, no. 2015: 57–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S026719051400018X.

- El Ayoubi, Mona. 2001. Chapter eleven: Exploring Intercultural Communication in research practice. Counterpoints 112: 167–183. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42976247.

- Fisher, Linda, Michael Evans, Karen Forbes, Angela Gayton, and Yongcan Liu. 2018. Participative multilingual identity construction in the languages classroom: A multi-theoretical conceptualisation. International Journal of Multilingualism. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1524896.

- Forbes, Karen, Michael Evans, Linda Fisher, Angela Gayton, Yongcan Liu, and Dieuwerke Rutgers. 2021. Developing a multilingual identity in the languages classroom: the influence of an identity-based pedagogical intervention. The Language Learning Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2021.1906733.

- Gerbing, David W., and Janet G. Hamilton. 1996. Viability of exploratory factor analysis as a precursor to confirmatory factor analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 3, no. 1: 62–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519609540030.

- Hammer, Mitchell R., Milton J. Bennett, and Richard Wiseman. 2003. Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 27, no. 4: 421–443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(03)00032-4.

- Haukås, Åsta. Forthcoming. Who are the multilinguals? pupils’ definitions, self-perceptions and the public debate. In Multilingualism and Identity: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Wendy Bennett, and Linda Fisher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haukås, Åsta, André Storto, and Irina Tiurikova. 2021. The Ungspråk project: Researching multilingualism and multilingual identity in lower secondary schools. Globe: A Journal of Language, Culture and Communication 12: 83–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.5278/ojs.globe.v12i.6500.

- Hofstadler, Nicole, Sonja Babic, Anita Lämmerer, Sarah Mercer, and Pia Oberdorfer. 2020. The ecology of CLIL teachers in Austria–an ecological perspective on CLIL teachers’ wellbeing. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2020.1739050.

- Henry, Alastair. 2017. L2 motivation and multilingual identities. Modern Language Journal 101, no. 3: 548–565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12412.

- Henry, Alastair, and Cecilia Thorsen. 2018. The ideal multilingual self: validity, influences on motivation, and role in a multilingual education. International Journal of Multilingualism 15, no. 4: 349–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1411916.

- Hu, Adelheeid. 2018. Plurilingual identities. In Foreign Language Education in Multilingual Classrooms, ed. Andreas Bonnet, and Peter Siemund, 151–172. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Jessner, Ulrike. 2008. Teaching third languages: findings, trends and challenges. Language Teaching 41, no. 1: 15–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444807004739.

- Kemp, Charlotte. 2007. Strategic processing in grammar learning: Do multilinguals use more strategies? International Journal of Multilingualism 4, no. 4: 241–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.2167/ijm099.0.

- Kroger, Jane. 2007. Identity formation: qualitative and quantitative methods of inquiry. In Capturing Identity: Quantitative and Qualitative Methods, ed. Meike Watzlawik, and Aristi Born, 179–196. Lanham: University Press of America.

- Kulbrandstad, Lars Anders. 2018. Språkhaldningar i det fleirspråklege Norge [Language attitudes in multilingual Norway]. In Å skrive nynorsk og bokmål. Nye tverrfaglege perspektiv [To Write Nynorsk and Bokmål. New Interdisciplinary Perspectives], ed. Eli Bjørhusdal, 177–193. Oslo: Samlaget.

- Leivada, Evelina, Marit Westergaard, Jon Andoni Duñabeitia, and Jason Rothman. 2020. On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition: (How) should we proceed? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/Q1366728920000358.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S. 2001. Varieties of validity: quality in qualitative research. In Higher Education Handbook of Theory and Research, ed. John C. Smart, 25–72. New York: Agathon Press Incorporated.

- Mellizo, Jennifer M. 2017. Exploring intercultural sensitivity in early adolescence: a mixed methods study. Intercultural Education 28, no. 6: 571–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2017.1392488.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2020. S.v. “valid,”. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/valid (accessed May 24, 2020).

- Monrad, Merete. 2013. On a scale of one to five, who are you? mixed methods in identity research. Acta Sociologica 56, no. 4: 347–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699313481368.

- Nadler, Joel T, Rebecca Weston, and Elora C. Voyles. 2015. Stuck in the middle: the use and interpretation of mid-points in items on questionnaires. The Journal of General Psychology 142, no. 2: 71–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2014.994590.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2017. Core Curriculum – Values and Principles for Primary and Secondary Education. Oslo: The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2018-19. Grunnskolens informasjonssystem [School Information System]. https://gsi.udir.no/app/#!/view/units/collectionset/1/collection/80/unit/1/ (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2019. Læreplan i fremmedspråk [Curriculum for Foreign Languages]. https://data.udir.no/kl06/v201906/laereplaner-lk20/FSP01-02.pdf. (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Norwegian National Centre for Foreign Languages in Education. 2020. “Elevane sitt val av framandspråk på ungdomsskulen 2019-2020 [Students’ Choice of Foreign Languages at the Lower Secondary School 2019-2020].” Notat 2/2020. https://www.hiof.no/fss/sprakvalg/fagvalgstatistikk/elevanes-val-av-framandsprak-i-ungdomsskulen-19-20.pdf (accessed August 28, 2020).

- Pavlenko, Aneta. 2006. Bilingual selves. In Bilingual Minds: Emotional Experience, Expression, and Representation, ed. Aneta Pavlenko, 1–34. Clevedon/Buffalo/Toronto: Multilingual Matters LTD.

- Pinter, Annamaria. 2014. Child participant roles in applied linguistics research. Applied Linguistics 35, no. 2: 168–183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt008.

- Prudon, Peter. 2015. Confirmatory factor analysis as a tool in research using questionnaires: a critique. Comprehensive Psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/03.CP.4.10.

- Rosenberg, Milton J., R. Rosenthal, and R. Rosnow. 1969. The conditions and consequences of evaluation apprehension. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195385540.003.0007.

- Ruokonen, Inkeri, and Seija Kairavuori. 2012. Intercultural sensitivity of the Finnish ninth graders. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 45, no. 2012: 32–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.540.

- Sandelowski, Margarete, and Julie Barroso. 2002. Reading qualitative studies. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 1, no. 1: 74–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100107.

- Schnell, Rainer, Tobias Bachteler, and Jörg Reiher. 2010. Improving the use of self-generated identification codes. Evaluation Review 34, no. 5: 391–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X10387576.

- Sickinghe, Anne-Valérie. 2016. Discourses of multilingualism in Norwegian upper secondary school. Doctoral thesis, University of Oslo.

- Statistics Norway. 2020. Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef (accessed August 28, 2020).

- Tavakol, Mohsen, and Reg Dennick. 2011. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2: 53–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- Ushioda, Ema. 2017. The impact of global English on motivation to learn other languages: toward an ideal multilingual self. The Modern Language Journal 101, no. 3: 469–482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12413.

- Van der Zee, Karen, Jan Pieter Van Oudenhoven, Joseph G. Ponterotto, and Alexander W. Fietzer. 2013. Multicultural Personality Questionnaire: development of a short form. Journal of Personality Assessment 95, no. 1: 118–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.718302.

- Vangsnes, Øystein. 2018. Den norske språkstoda i eit tospråksperspektiv. Variasjon i språkkompetanseprofilar [The Norwegian language situation from a bilingualism perspective. variation in profiles of language competence]. In Å skrive bokmål og nynorsk. Nye tverrfaglege perspektiv [To write Bokmål and Nynorsk. New Interdisciplinary Perspectives], ed. Eli Bjørhusdal, 77–96. Oslo: Samlaget.

- Zeevaert, Ludger. 2007. Receptive multilingualism and inter-scandinavian semicommunication. In Receptive Multilingualism, ed. J.D. ten Thije, and L. Zeevaert, 103–137. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.