ABSTRACT

In this paper, we use the lens of embodied language cognition and intersemiosis to argue for the importance of developing creative approaches to language work in classroom settings and we cite as an example some activities from a workshop that was developed for modern foreign languages (MFL) trainee teachers in London (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9hR-LQ0xOE). The workshop resulted from a collaboration between an applied linguist (Coffey) and an artist-educator (Patel), and combined their shared understanding of language use as an emotional, embodied enterprise etched into our autobiographical identities. We suggest that working with intersemiotic approaches to language has the potential to reinvigorate language pedagogy by challenging dominant metaphors both of ‘language’ and of ‘learning’. The paper intends both to make a practical contribution in its reporting of activities, which we hope will inspire teachers and teacher educators to develop intersemiotic approaches for their own settings, and also to contribute to the broader scholarship that calls for ‘reframing teacher cognition’ (e.g. Coffey [2015]. Reframing teachers’ language knowledge through metaphor analysis of language portraits. The Modern Language Journal 99, no. 3: 500–14), even ‘liberating language education’ (e.g. Lytra et al. [2022]. Liberating Language Education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters), to imagine new orientations for how we engage with languages in our lives and our classrooms.

The mind in creation is as a fading coal, which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness. (Shelley Citation1921 [1821]: 53)

Introduction

Some settings of foreign language education have recently seen a post-communicative diversification of methodologies that incorporate a variety of creative approaches. Within this diversification there has been growing interest in developing pedagogical practices informed by embodied cognition (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1999) that afford active awareness between language(s), emotion(s), and the body. While there is no single definition of ‘embodied cognition’, theoretical models aligning themselves with the term ‘all share an emphasis on the body functioning as a “constituent of the mind” (Leitan and Chaffey Citation2014: 3) rather than secondary to it’, and are committed to integrating a fuller ‘range of perceptual, cognitive, and motor capacities’ (Fugate et al. Citation2019: 275) than acknowledged in traditional models of cognition. With a more specifically linguistic focus, embodied language cognition refers to the actual somatic production and reception of language: utterances, sounds, and symbols as physical acts and psychological processes. From a sociocultural perspective, these individual acts are enmeshed in social and cultural matrices. Traditional cognition separates, or abstracts, the representation of language items (whether words, sentences, or sounds) from the ‘act’ of language, and the emotional, embodied aspects that are necessarily at stake in using or processing language in real time. So-called Cartesian dualism, that is, the separation of mind from body and also reason(rationality) from passion(emotion), continues to underpin dominant theoretical models of learning, even though the dichotomy has been widely discredited by neuroscientists (e.g. Damasio Citation1994), as well as by socio-constructivist educators who recognise that ‘embodied knowledge sits at the heart of teaching and teacher education’ (Craig et al. Citation2018: 329)

Intersemiosis and embodied cognition: languages in the material world

A major development in the expansion of the motivation paradigm has been an awareness of the multi-sensory nature of learning, a dimension that recognises the production of sound within the body. One of the ways awareness of embodied multilingualism has been encouraged is through the focus on speakers’ representations of their languages through such tools as linguistic body portraits which have been adapted for use in a range of settings (see Busch Citation2021; Coffey Citation2015; Kusters and De Meulder Citation2019; Melo-Pfeifer Citation2021; Molinié Citation2009; Peters and Coetzee-Van Rooy Citation2020; Prasad Citation2014; Tabaro et al. Citation2021). Other methods focus on the integrative role of ‘gesture’ and different forms of multimodality in second language acquisition (Stam and Urbanski Citation2023), or the potential of musicality and rhythm (Degrave Citation2019) as essentially somatic processes.

Intersemiosis, a Jakobsonian term borrowed here from Torop (Citation2000), and also Campbell and Vidal (Citation2019), captures the way meaning is made through sensory reconfiguring at the intersection of language, body and the material environment. Intersemiosis, in our use of the term, differs from multimodality in that it extends beyond technological affordances or diversity of inputs to point to an epistemological reconfiguring of sensory, material and linguistic associations. For example, combining a sound as a colour, a word as an image, a tactile sensation as an emotion.

Given the physical and role-bound limits of classroom learning, we are using embodied cognition in two senses: (1) embodied learning within the classroom space, and (2) the deliberate focus in pedagogical content on the socio-affective, embodied aspects of language (embodied language cognition). In the first sense, while we agree that ‘simply having students use technology or move their bodies does not constitute embodied learning’ (Fugate et al. Citation2019: 280) the workshop we describe below took as its starting point the physical environment of the classroom space and how the participant human beings would interact within it and with the material provided. For instance, the activities set up sensory linguistic affordances in response to tactile stimuli (the ‘seeing and touching’ activity), then moving about the space to exchange partners or to draw outlines of each other’s silhouette against the wall. In the second sense, the workshop did not focus on language function in the usual communicative sense (described by Coffey and Leung Citation2015, Citation2019) but on how different words feel. In other words, we focused on the aesthetic appreciation of sounds participants enjoy in different languages; the representation of sounds through colour and drawing, then through sculpture; and why some words were considered untranslatable. The aim here was to explore students’ somatic-aesthetic relationship to different languages in order to emphasise of the physicality of producing and hearing language.

Linguists, almost by definition, have tended to focus on ‘languages’ as discrete systems but ‘embodied cognition’ recognises that an individual’s linguistic repertoire is etched into individual (autobiographical) subjectivity as agentive engagement within broader structures of languages as social (rather than linguistic) systems. In other words, the subject-object distinction is blurred. There is a traditional division (in the Western philosophical tradition) between our capacity to conceptualise (seen as a mental activity – reason) and our ‘faculties of perception and bodily movement’ (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1999: 37). This dichotomy is held, by Lakoff and Johnson among others, to be false. Influenced by Merleau-Ponty, Lakoff and Johnson describe as phenomenological embodiment the way our ‘image schemas are … comprehended through the body’ (36). Speaking a foreign language calls on speakers to perform as subjects, not necessarily to adopt a different persona but to mimetically extend their habitual mode of verbal and physical communication and this calling and its response are always done within and to a cultural context. There is obviously nothing intrinsic about, for example, the range of colour perceptions that individuals associate with a language (‘English’ is not blue or green) but the perceptual association of language-and-colour or language-and-shape signals a chain of (personal, historical) perceptual associations which are embedded in broader sense-making schema.

Despite recent metrics (e.g. Zhang’s Citation2020 bibliometric analysis of the field of second language acquisition) showing that the bulk of research output and citations in the study of language education still lie within traditional cognitive and psycholinguistic approaches, there is a quiet persistent voice on the margins calling for more diverse and imaginative scholarship through interdisciplinary epistemologies.

Such ‘work on the margins’ into learner subjectivity and auto/biography has spawned a range of different methodologies, intended both for eliciting empirical data and/or for teacher development as tools for reflexivity as well as models of pedagogical activities. These diverse methodologies range from modes of ‘narrative knowledging’ (Barkhuizen Citation2011) such as journaling (Johnson and Golombek Citation2004) and language autobiographies (e.g. Coffey and Street Citation2008) to arts-based innovations (e.g. Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer Citation2019) that seek to build alternative conceptual models of what language education can be (Lytra et al. Citation2022). What these strands of scholarship have in common is a broader positioning of language learning as a situated identity project whereby the learner is not simply a learner responding to input but is a social actor operating within complex, diachronically constructed networks of affect. Language is seen not as an autonomous system but as a social and cultural practice that is always rooted in its context and interpreted according to the conditions of the communicative encounter.

The aims of such approaches include multisensory engagement with language that promotes a broader, and deeper, relationship with the object-language beyond functional (‘can-do’) skills. While, in the school system, formal curricula and high-stakes national assessments continue to structure language instrumentally as either a discrete set of analytical skills (e.g. facilitating vocabulary retention or grammatical accuracy) and/or communicative functional competence (e.g. I can buy a train ticket, I can ask directions), some teachers have embraced more complex and contextually inclusive language epistemologies through a range of creative, dynamic innovations. These engagements not only extend the functional language paradigm, but call into question deeply rooted ontological and epistemological assumptions about what language is and about the framing of the individual as an autonomous agent. In particular, we wish to challenge the computational model of cognition that is currently being prescribed in English education.

Such innovations resonate with teachers’ own lived experience as multilinguals and their awareness that linguistic repertoires combine somatic, emotional and sociocultural investments as well as prowess in grammatical analysis and communicative function.

Modern foreign languages in England: tackling the challenges of ‘motivation’ and ‘institutional power’

Psycholinguistic models, which prevail in motivation research and in pedagogical practices, are characterised, at least in their positivist form, by the a priori isolation of variables. These models therefore lend themselves to quantification and replication more easily than theoretically layered models that adopt qualitative, often interpretative, research methods. Aside from claims of scientific rigour, measurability of performance outcomes is also a mechanism of control that enables and feeds into the neoliberal political economy that has engulfed education in many societies, including England. As stated by Ball, a major consequence of ‘performativity is to reorient pedagogical and scholarly activities … away from aspects of social, emotional or moral development that have no immediate measurable performative value’ (Ball Citation2016: 1054).

The position of English as the global lingua franca raises a number of particular challenges for the learning of modern languages in anglophone settings, the most obvious being the perception of irrelevance and ‘value’ (Coffey Citation2018) for career and practical purposes. Taking the case of language learning in England specifically, learner motivation has been researched through different lenses, but mostly through standardised attitude measurement mechanisms such as questionnaires or semi-structured interviews. Broadly speaking, recurrent themes in motivation studies include the representation of particular languages compared to others (e.g. ‘French is the language of love and stuff’, Williams et al. Citation2002) and the instrumental perception that foreign language proficiency is not needed for travel or for employment prospects, given the dominance of English.

What seems certain, as pointed out by Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie (Citation2017: 465), is that conventional motivation research has yet to fully engage with the complexity of ‘conflicting patterns of underlying conscious and unconscious motives’ that shape learners’ motivation to learn. As the same authors point out, we need to extend our understanding of motivation from explicit, measurable variables toward an exploration of the ‘implicit, not fully-conscious factors (which) might play a stronger role in language attainment than formerly believed’ (Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie Citation2017). Even motivation research that aims to understand emotional investment has been constrained by methodological procedures that seek to measure explicit (i.e. stated, known, recognised) self-reporting of feelings and attitudes that are characteristically synchronous and ahistorical.

While the dominant research paradigm recognises motivation and attitude as intrapersonal, we believe that other areas invite further attention such as (1) the effects of the institutional power regimes that shape school structures and educational systems themselves, and (2) the more broadly held ideology of language as a single form of communication, discrete from wider cultural practices.

The first of these is important to acknowledge because ‘alternative’ pedagogies (i.e. those that seek to extend the confines of an instructed cognitive-behaviourist epistemology) are hampered at several turns by a political ideology that depends on ever more aggressive regulation of teacher education, curriculum content and quantifiable assessments. An example of this can be seen in the recently English-government-sponsored ‘research review’, currently being enacted into curricular policy; the review stimulated a collection of critical responses which appeared in a recent special issue of The Language Learning Journal (volume 50, no.2).

The relatively low motivation for languages cannot be disentangled from broader ideologically driven conditions which range from the increasing strictures of top-down prescription to deteriorating conditions for teachers, cuts in funding for meaningful professional development, and – in post-Brexit Britain – a broader climate of cultural isolationism. The centralised streamlining of professional development for teachers has been ‘increasingly directed towards narrower, economistic measures of teaching quality’ (Ellis et al. Citation2020: 606). Teacher training is now tightly controlled through selectively funding ‘“loyal” or trusted entrepreneurs and enterprising charities’ (Ellis et al. Citation2020: 615) to deliver professional development to teachers, rather than local authorities and universities.

The resultant snarl-up has led to unprecedented levels of teacher burnout, and epistemological rationales that are incoherent and not fit for purpose – if indeed the purpose is to encourage a rich and flourishing multilingualism in schools and in the population. Teachers, as well as students, need to feel valued and to exercise a certain level of freedom in how they teach, including how creative they can be within the constraints of narrow assessment regimes.

The second area for development within language teaching, and maybe within applied linguistics research more generally, is an opening up of how language is defined as a form of communication. Arguably, this could be especially important for ‘native speakers of English, for whom languages were often regarded an ‘extra’ benefit, giving access to new cultures or experiences, or a way of affirming an international identity, rather than a sine qua non of professional and personal life’ (King et al. Citation2011: 30). While the functional language content of communicative syllabuses is premised on language as a social act, communicative pedagogies treat language as a disembodied code. This computational model of cognition, based around individuation of external stimuli (the input processing metaphor), has dominated psychological and educational research in the modern era.

This model has been challenged in recent decades by alternative models, including what has been termed ‘embodied cognition’ (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1999), that refute mind–body duality (Coffey Citation2021). Embodied cognition understands the body, its sensations and its situatedness, to be not just external circumstances that are processed by the mind, but actually to constitute subjective experience in co-cognition with internal thought processes. In other words, ‘instead of emphasising formal operations on abstract symbols, the new approach foregrounds the fact that cognition is, rather, a situated activity, and suggests that thinking beings ought therefore be considered first and foremost as acting beings’ (Anderson Citation2003: 91).

Intersemiotic approaches seek to redress the view of language knowledge as a disembodied set of principles (rules to learn and apply) and stocks of words (the value of which is dubiously measured by their ‘frequency’). Extensive research now demonstrates that language learning flourishes in educational settings where development of learners’ identity as multilinguals is prioritised. In a critique of the narrow ‘knowledge-based’ modern languages curriculum currently being imposed in England, Evans and Fisher (Citation2022: 218), following their own large-scale research into developing school pupils’ multilingual identities, suggest that ‘rather than a “basic knowledge first” approach, a more effective strategy would be to combine knowledge input with motivational, affective and communicative development’. An integral aspect of multilingual identity development is recognising how language(s) are embedded into the lives of learners in ways that resonate for them. This calls for an approach which recognises the interpersonal and social dimensions of language, along with other forms of communication. Such an understanding of language has been proposed by general linguists for some time e.g. Harris’ (Citation1996) ‘integrationist linguistics’, but remains very much on the margins in language education. There have been some suggestions for applying integrationist approaches in language teaching (see Toolan Citation2009) but state-mandated curricula in England have moved in the opposite direction to an increasingly restrictive model based on assumptions that language is an autonomous code to be transmitted through behaviourist (rote learning) or narrowly construed cognitive scientific (information-processing) pedagogies. Intersemiotic approaches allow learners to make connections that are not included in conventionalised school pedagogies (in English schools at least), although they do invite comparisons with ancient traditions that recognise embodied cognition through rhetoric and mimesis.

The ‘Lost and Found in Translation’ workshop

Development process

The two-day workshop that we are calling ‘Lost and Found in Translation’ evolved out of a dialogue between the authors around Simon’s interest in the lived experiences of language acquisition as emotional repertoires in multilingual speakers. There were eighteen participants, all postgraduate students training to be secondary school teachers of modern foreign languages in London. Our intention is to share our activity ideas within a theoretically problematised space rather than to present an empirical study. Although the workshop was meticulously planned, we wanted it to be an organic dispositif to which individual participants bring their own language and cultural histories. We do not profile the individual participants or analyse their engagement, as this was not our aim. Rather, we are presenting a rationale for including different, what we are calling ‘intersemiotic’, approaches in language teacher education. As such, signed consent was given by participants for them to be filmed during the workshop and in one-to-one follow up interviews for the purposes of publicity but we did not seek consent for participation in research.

The development of the language workshop was a process of trying out ideas over several months through discussions between Daksha and Simon, as Daksha made drawings and sculptures in her studio. Daksha explains:

Our initial conversations resonated with my own diasporic experiences of travelling from Kenya to India before arriving in rural Wales at the age of eight. Moving between languages was just part of my everyday life, as it is for so many people across the globe. The multilingualism of my childhood was inextricably linked to the senses: to the different sounds, colours, smells, textures and landscapes connected to each language and its culture. Moving between languages, especially when you are not fluent and do not have an extensive vocabulary, often involves some creativity and flexibility in its use. This brings with it a certain tolerance of ambiguity, a quality which artists are very familiar with; artworks do not have fixed meanings but are open to interpretation. Fluidity and an openness of meanings are highly valued by artists.

The arts activities were designed to be accessible in the sense that we assumed participants had no specific training in or experience of drawing or sculpture. We used simple materials and methods so that the focus remained upon the ideas behind the drawings and sculptures. Daksha showed examples and demonstrated each new method, whilst at the same time explaining the ideas and concepts each art activity was exploring. This often involved talking about her own experiences and feelings, enabling her to model ensuing conversations between students. Students’ discussions and interpretations of each other’s artworks inevitably led to a variety of different interpretations, which mirrored the fluidity of language and the multi-cultural identities of the group. Throughout, the workshop activities were designed to be enjoyable, fun and very interactive. Here we outline some of the activities in more detail.

Activity 1: ‘What’s in a name?’

This first activity was an introductions game, which used students’ names to reflect cultural and social identities. Daksha explained how her own name was pronounced differently as she moved between countries, and how it can be spelt in many different ways in English because there is no direct translation from Gujarati to English.

Students were asked to ‘draw’ their own names (or nicknames) on a large sheet of paper by filling in the shape of each letter with colours, textures or symbols that represented something about their identity. Daksha first showed them her own name drawing and explained that the colours and symbols represented memories of the sea/sand of her childhood in Africa, the bright colours of textiles in India, the earthy greens and browns of rural Wales, the grey buildings of central London and the red bricks of Manchester. She spoke about the different ways in which her Indian name was pronounced by people from different countries and how this has changed her own relationship to her name. Students were given time to draw their name and then asked to describe their drawings to each other in pairs. This was followed by whole group discussion, where students noted that although they had been studying together for a few months, they learnt some new things about each other. Their images represented social activities such as sports, music, foods as well as individual interests. Many drawings were culturally specific ().

Activity 2: ‘Seeing and touching’

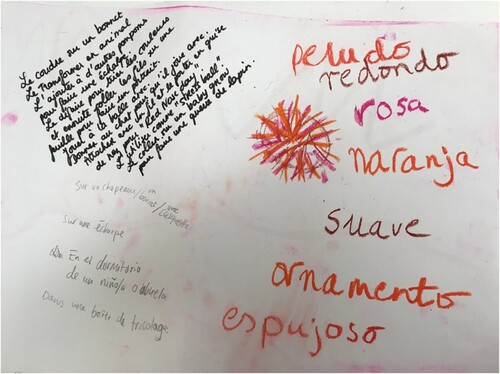

This activity () explored how the sense of touch can evoke sensations that may not translate directly into language. The activity requires students to describe something that they can’t see and may be unknown to them; to experience what it feels like to be on the edges of language. A variety of different objects were placed inside small bags: a pine-cone, a small animal bone, a dried orange peel, moss, a woollen pompom. Working in pairs, students took turns to place their hands inside the bag and were asked to describe the object (its texture, form, warm/cold, hardness/softness) to their partner without naming it but using adjectives or feeling words. Their partner was asked to guess what the object was. Students could choose which language they worked in and were given five minutes per object before revealing it and repeating with a new bag/object.

This was followed by a short story building game which used the same objects as starting points. This time each object was placed upon a large sheet of paper upon which students were asked to write using coloured oil pastels. By using art materials to write, Daksha wanted to make the connection between drawing and writing, which share a history (early pictorial languages), and tools such as pencil and paper. We emphasised that both activities – drawing and writing – are connected to thinking ().

There were three stages to this activity, and between each stage students were asked to move to another chair/object in the room. The stages were:

- Write a list of adjectives to describe your object on the sheet of paper in coloured felt pens or oil pastels without naming it (German, French or Spanish). Describe the colours, materials, shapes, textures, etc. E.g. shimmering pink, triangular at one end with long spike at other, spiky, cold hard metal, small and furry.

- Move to another object/chair and describe the places/environments where you might find the object using descriptive phrases. E.g. On top of a shelf in a cold, damp cellar

- Finally move to another object/chair and write a few sentences describing an imaginary interaction between you and the object. E.g. I was so pleased to find the red button behind the chair, and immediately sewed it back onto my coat.

Activity 3: ‘Body and sound’

This activity began with a whole group discussion about whether language can be experienced through the body. We traditionally think about speech as located in the larynx, lungs, brain and diaphragm. The students were asked if certain words can trigger sensations in other parts of the body? Which words? Can you give examples? How does tone of voice and emotion change how a word is experienced? Is there an embodied aspect to language making e.g. onomatopoeic words such as yawn, hiccup or gargle?

Following discussions, students were asked to make abstract marks in response to descriptions of speech such as (1) a spiky/prickly tone of voice; (2) a soft whisper (3) a guttural sound (4) a high nasal sound (5) angry shouting (6) stuttering (). Daksha showed examples of her abstract drawings alongside scripts from Eastern languages to make the connection between abstract signs/marks and language. She explained that if you look closely at a representational drawing it will be made up of lots of different types of lines and marks, constituting a visual system that is in itself a kind of alphabet.

Students were asked to experiment with how they used their bodies whilst drawing by varying pressure, standing up rather than sitting, using their whole arm and shoulder, instead of just the wrist. This was a loosening up exercise for the next stage which used extra-large body sized pieces of paper attached to the wall. In pairs, students created a whole-body outline by drawing around each other whilst standing against the paper. In this exercise, students were asked to make abstract marks inside and around their body outlines to indicate where they experienced certain words (). Simon had previously compiled a list of words that evoke emotions or feelings in different languages (see ), and students were asked to choose a few words from the list and say them out loud whilst making abstract marks. The scale of the drawings meant that whole body movements were involved. This combined with the voicing of words to create a more experiential exercise which was lively and animated.

Table 1. Lists of emotion or feeling words in French, Spanish and German.

Activity 4: ‘Found in translation’

This was a whole group discussion activity which explored words that do not have an equivalent in other languages. We began by giving some examples (below) and students were next asked to find their own by searching online or simply thinking. Some wonderful examples of words describing culturally specific social activities were shared by all.

German: sturmfrei (When parents are away, and you have the house to yourself.)

French: frileux-euse (adjective describing someone who feels the cold easily. Also exists in Spanish as friloso/a)

French: flâneur (person strolling around city in aimless way, cool aloof observer of urban society)

Spanish: el entrecejo (the space between both eyebrows)

Activity 5: ‘Guess the word’

This activity is based upon a traditional party game where one person in a group has the name of a famous person attached to their forehead and asks numerous questions of the group until they guess the identity of that person. In this version, students were asked to guess a word (in Spanish, German or French). They moved into small circles of chairs around the room for this activity. Simon had compiled some unusual words in all three languages to create a more intriguing game (see list below), and the person guessing the word was told beforehand if it was a noun, adjective or verb to facilitate their questions ().

Table 2. Guess the word game.

Activity 6: ‘Language sounds’

For this activity Daksha had previously asked five students who spoke different languages to choose some words that they felt were very ‘typical’ of the particular sounds of each language. Students were native speakers and enjoyed choosing their favourite sounding words. Daksha had recorded the students speaking the words in preparation for the activity.

We introduced the activity by asking the group if one can often recognise a language by its sound, even if you can’t speak the language. If you can recognise a genre of music without knowing the song, is there a sonic and aural aesthetic to languages? Daksha played her recordings and asked the group to listen to the sounds of each word without focusing on meanings. To illustrate, she said a few words in Gujarati out loud, a language unfamiliar to them. We discussed how meanings can stop you listening to a language sound; for instance you may have a mental picture of the object being described.

The recordings were played a few times and students listened in silence. We asked if a language sound can have a form or shape Some diagrams of speech mechanisms were shown to explore if we make internal forms with our tongues, larynx or diaphragm as we speak. This activity asked students to make an imaginative leap from sound to a 3D structure to represent a specific language sound. They were asked to transform something invisible into something tangible. Daksha chose paper sculpture as a method because of its flexibility and simplicity, which nevertheless allowed a very wide range of forms to be constructed quickly. She showed examples and demonstrated how to construct them using pins, tape and foam board. Students were very productive and created a few pieces each (). They were all displayed together at the end with a group discussion. It was an enjoyable end to our two days together!

Discussion

Two key elements that we wish to focus on within the broader frame of ‘intersemiosis’ are: translation as language play and intersemiotic approaches as a transgressive pedagogy. Each of these elements orients attention to the powerful aesthetic dimension of language that connects the individual to the material world through sensory engagement. This aesthetic dimension offers the potential to transcend those disciplinary boundaries that separate form and function as if language were a surface code with corresponding equivalents in other languages.

Translation as language play

The relationship between students’ first language(s) and the target language has always been fraught in language pedagogy. From the widely denigrated ‘grammar-translation’ approaches that became normalised in school pedagogies (viewed, erroneously, as a classical approach), through to the ‘strong’ version of the direct method, later reinterpreted as communicative language teaching, explicit use of first language(s) and, indeed, any language other than the target language, has ebbed and flowed according to fashion. In schools in England, the current version of the National Curriculum (dated from 2014) and the national exams that it prepares students for (i.e. broadly speaking, GCSE Languages at age 16 and ‘A’ [Advanced] level at age 18), translation has enjoyed a renaissance and is now an assessed skill. However, recognition of the instability of the relationship between form and function within and across languages is under-developed, so that translation tends to be reduced to code-cracking or producing the ‘right’ answer, rather than problematising the gaps and compromises that translation necessarily entails.

This conscious engagement with language, resonant with and extending the reach of what Cook (Citation2000) termed ‘language play’, is central to the premise of creativity in language learning and teaching. Appreciation of the ludic aspect need not remain the preserve of literary translation but points to the poetic dimension of mundane language. Where the English dictum lost in translation points to a deficit, a slipping into the void between, we wished to emphasise the fruitful creative potential of this gap as a creative space across languages and media. Students reflected with relish on their favourite sounding words across languages, including mother tongue (e.g. ‘awkward’ was cited as a favourite word by one of the teachers for its expressivity), and later learnt languages; they articulated feelings through words and sounds, through drawings and paper sculpting. As they considered the cultural context of ‘untranslatable’ words, we saw the energy and delight in their language play. This can be seen through the video summary of the workshop where students themselves describe why they recognise the importance of this type of work. This is as far from the core functional language of mainstream communicative curriculum content as it is far from the behaviourist-cognitivist approaches of mainstream pedagogy.

While translation is a seemingly obvious pedagogical strategy or communicative necessity, we set out in our workshop to exploit the gaps and the messiness that arise once we try to move from one language to another, from one worldview system to another, and one medium to another. Translation here is intersemiotic in the sense that as words are drawn as marks on paper and as sounds are sculpted into paper forms, the emphasis on language as more than a semantic cipher shifts the value of an utterance from transactional function to an act of performance infused with emotion. Intersemiotic translation ‘opens up a myriad of possibilities to carry form and sense from one culture into another beyond the limitations of words. At the same time, such processes impact on the source artefact enriching it with new layers of understanding’ (Campbell and Vidal Citation2019: xxvi).

‘I never expected that’: intersemiotic translation as a transgressive pedagogy

Historically, language teaching methodologies have developed within a tension between analytical models (focusing on structure, grammar and lexis) and utilitarian ‘communicative’ goals, focusing on function. However, both these methodological orientations can operate within an ontological model that denudes language of its human qualities as an embodied and affective social practice. Intersemiotic approaches such as those outlined in this article seek to re-humanise language by incorporating bodily and emotional connections to language beyond the dominant cognitive processing metaphors of input and output. At the same time, the focus on materiality chimes with the recent wave of post-human ontology, where human agency is not autonomous but recognised as dependent on an ecology of matrix conditions that include the material. What counts as legitimate forms of language reproduction depends on socially sanctioned power structures and this includes ways of reproducing representations of foreign language(s) in institutional settings.

‘Creativity’ has become a ubiquitous catchword in education. It doesn’t have a single meaning but is, rather, a floating signifier (Coffey and Leung Citation2015, Citation2019). We are concerned that the term ‘creativity’ has been co-opted by neoliberal performativity regimes, whether in marketing discourses or in state-prescribed pedagogies (as we currently have in England). Measures of performance, including student satisfaction, place responsibility entirely on the teacher while, paradoxically, centripetal, authoritarian interventions stifle the very pedagogical freedom that is prerequisite to fostering creativity and emotional investment. As exhorted by Freire (Citation1993 [1970]: 48), in whose ‘banking’ approach analogy we see mainstream school pedagogies reflected, teachers’ efforts to encourage critical awareness and to humanise learning, must be ‘imbued with a profound trust in people and their creative power’.

As stated, we did not analyse student feedback systematically. However, the video extracts (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9hR-LQ0xOE) clearly demonstrate the vitality and engagement of the participants during the workshop. They told us not only how valuable the learning was, but how unexpected: as one teacher comments in the video: ‘I never expected to do anything like this during my [training]’. We were struck by this remark. It suggests to us that trainee teachers enter training with a preconceived set of ideas that they will be taught a set of procedures, or imitable skills, rather than engage with discussions of learning as a deeply affective and material process that is etched onto our emotional autobiographies.

Creative pedagogies, including through workshops such as the one presented here that seeks to valorise the aesthetic and somatic dimensions of multilingualism, are especially needed today in educational settings where the diminution of arts and humanities studies, driven by an aggressive ideology of measure and accountability, has led to ‘a narrower curriculum’ (Neumann et al. Citation2020: 707) and the marginalisation of genuine (emancipatory) creativity. In this respect, we believe that the creative incorporation of intersemiotic approaches not only emphasises the value of the curriculum content being taught, but goes some way to compensating for the entrenched instrumentalisation of language education in English schools.

Conclusion

Approaches such as those described here, inscribed in what Canagarajah has called a ‘sociomaterial orientation’, allow the ‘language learning project’ (Coffey and Street Citation2008) to be recontextualised, as learners’ lives are narrated, not simply through text or other discursive forms, but through intersemiotic linkages that emphasise how bodies mediate between language and the material world, not acting on the world but forming part of it.

The different activities that constituted the two-day workshop were conceived with a view to encouraging future teachers to re-engage with their own passion for their languages. By drawing on their own their autobiographical repertoires of plurilingualism, teachers constructed an emotional semiotics through touch sensations, through the joy of speaking words that they like the sound of, through delighting in the cultural specificity and affective resonance of words that cannot quite translate, and through recontextualising language by drawing and sculpting sounds. We argue that creatively engaging with plurilingualism in these ways offers the potential to reinvigorate language learning, especially in anglophone contexts such as the UK, and may even constitute a transgressive pedagogy that challenges dominant metaphors of language and learning.

Language teachers recognise the value of more integrated perspectives but are not always sure how these can inform their classroom practices. Even where language pedagogies are increasingly prescribed, as in England’s schools, we are confident that teachers can deploy creative pedagogies which encourage connections across languages, across media, and across different sites of feeling. There is always a space – some wiggle room – where prescription can be transgressed. As well as proposing a profound shift in the positioning of learner and learning, creative language pedagogies, whether inspired by some of our ideas presented here or by others, clearly promote greater enjoyment of language learning, as demonstrated in our feedback.

We acknowledge the role of traditional language classroom work such as the goals of memorising vocabulary and understanding and applying grammar rules, but we advocate a complementary perspective which will not only support these traditional goals but will open up conceptions of ‘language’ and the purposes of language learning. National curricula tend to posit an outdated monolingual model (regardless of language) which does not correspond to the multilingual reality of today’s speakers, and which is a largely Western construct anyway (Dornyei and Al-Hoorie Citation2017). Much of what we propose is instinctively known by multilinguals and by anyone who reflects on the poetic and aesthetic dimension of language(s). While teachers willingly subscribe to a more holistic view of language learning, informed by their own autobiographical subjectivity, high-stakes assessment regimes continue to perpetuate a narrow conception of language and of learning that is denuded of emotional and sensorily experiential knowing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, M.H. 2003. Embodied cognition: a field guide. Artificial Intelligence 149, no. 1: 91–130.

- Ball, S. 2016. Neoliberal education? Confronting the slouching beast. Policy Futures in Education 14, no. 8: 1046–59.

- Barkhuizen, G. 2011. Narrative knowledging in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly 45, no. 3: 391–414.

- Busch, B. 2021. The body image: taking an evaluative stance towards semiotic resources. International Journal of Multilingualism 18, no. 2: 190–205.

- Campbell, M. and R. Vidal. 2019. Entangled journeys–an introduction. In Translating Across Sensory and Linguistic Borders. Intersemiotic Journeys Between Media, eds. Madeleine Campbell and Ricarda Vidal, xxv–xliv. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Coffey, S. 2015. Reframing teachers’ language knowledge through metaphor analysis of language portraits. The Modern Language Journal 99, no. 3: 500–14.

- Coffey, S. 2018. Choosing to study modern foreign languages: discourses of value as forms of cultural capital. Applied Linguistics 39, no. 4: 462–80.

- Coffey, S. 2021. Auto/biographical approaches for a post-cartesian model of plurilingualism. Italiano LinguaDue 12, no. 2: 307–16. https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/promoitals/index/.

- Coffey, S. and C. Leung. 2015. Creativity in language teaching: voices from the classroom. In Creativity and Language Teaching: Perspectives from Research and Practice, eds. Jack Richards and Rodney Jones, 114–29. London: Routledge.

- Coffey, S. and C. Leung. 2019. Understanding agency and constraints in the conception of creativity in the language classroom. Applied Linguistics Review 11, no. 4: 607–23.

- Coffey, S. and B. Street. 2008. Narrative and identity in the ‘language learning project’. The Modern Language Journal 92, no. 3: 452–64.

- Cook, G. 2000. Language Play, Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Craig, C.J., J. You, Y. Zou, G. Curtis, R. Verma, D. Donna Stokes and P. Evans. 2018. The embodied nature of narrative knowledge: a cross-study analysis of embodied knowledge in teaching, learning, and life. Teaching and Teacher Education 71: 329–40.

- Damasio, A. 1994. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam.

- Degrave, P. 2019. Music in the foreign language classroom: how and why? Journal of Language Teaching and Research 10, no. 3: 412–20. https://www.academypublication.com/issues2/jltr/vol10/03/02.pdf (Accessed 15 November 2022).

- Dörnyei, Z. and A.H. Al-Hoorie. 2017. The motivational foundation of learning languages other than global English: theoretical issues and research directions. The Modern Language Journal 101, no. 3: 455–68.

- Ellis, V., W. Mansell and S. Steadman. 2020. A new political economy of teacher development: England’s teaching and leadership innovation fund. Journal of Education Policy 36, no. 5: 605–23.

- Evans, M. and L. Fisher. 2022. The relevance of identity in languages education. The Language Learning Journal 50, no. 2: 218–22.

- Freire, P. 1993 [1970]. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Penguin.

- Fugate, J.M.B., S.L. Macrine and C. Cipriano. 2019. The role of embodied cognition for transforming learning. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 7, no. 4: 274–88.

- Harris, R. 1996. Signs, Language and Communication. London: Routledge.

- Johnson, K.E. and P.R. Golombek. 2004. Narrative inquiry as a mediational space: examining emotional and cognitive dissonance in second-language teachers’ development. Teachers and Teaching Theory and Practice 10, no. 3: 307–27.

- Kalaja, P. and S. Melo-Pfeifer. 2019. Visualising Multilingual Lives: More Than Words. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- King, L., N. Byrne, I. Djouadj, J. Lo Bianco and M. Stoicheva. 2011. Languages in Europe Towards 2020. Analysis and Proposals from the LETPP Consultation and Review. EU Project Document: Languages in Europe, Theory, Policy and Practice.

- Kusters, A. and M. De Meulder. 2019. Language portraits: investigating embodied multilingual and multimodal repertoires. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 20, no. 3. DOI: 10.17169/fqs-20.3.3239.

- Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought. New York: Basic Books.

- Leitan, N.D. and L. Chaffey. 2014. Embodied cognition and its applications: a brief review. Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture 10, no. 1: 3–10.

- Lytra, V., C. Ros i Solé, J. Anderson and V. Macleroy, eds. 2022. Liberating Language Education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. 2021. Exploiting foreign language student-teachers’ visual language biographies to challenge the monolingual mind-set in foreign language education. International Journal of Multilingualism 18, no. 4. DOI: 10.1080/14790718.2021.1945067.

- Molinié, M., ed. 2009. Le Dessin Réflexif: Elément pour une Herméneutique du Sujet Plurilingue. Cergy-Pontoise: Centre de Recherche Textes et Francophonies (Université de Cergy-Pontoise).

- Neumann, E., S. Gewirtz, M. Maguire and E. Towers. 2020. Neoconservative education policy and the case of the English baccalaureate. Journal of Curriculum Studies 5, no. 5: 702–19.

- Peters, A. and S. Coetzee-Van Rooy. 2020. Exploring the interplay of language and body in South African youth: a portrait-corpus study. Cognitive Linguistics 31, no. 4: 579–608.

- Prasad, G. 2014. Portraits of plurilingualism in a French international school in Toronto: exploring the role of visual methods to access students’ representations of their linguistically diverse identities. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 17: 51–77.

- Shelley, P. 1921 [1821]. A defence of poetry. In Peacock’s Four Ages of Poetry; Shelley’s Defence of Poetry; Browning’s Essay on Shelley, ed. H.F.B. Brett-Smith, 21–59. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Stam, S. and K. Urbanski. 2023. Gesture and Multimodality in Second Language Acquisition: A Research Guide. New York: Routledge.

- Tabaro Soares, C., J. Duarte and M. Günther-van der Meij. 2021. ‘Red is the colour of the heart’: making young children’s multilingualism visible through language portraits. Language and Education 35, no. 1: 22–41.

- Toolan, M., ed. 2009. Language Teaching: Integrational Linguistic Approaches. New York: Routledge.

- Torop, P. 2000. Intersemiosis and intersemiotic translation. European Journal for Semiotic Studies 12, no. 1: 71–100.

- Williams, M., R. Burden and U. Lanvers. 2002. ‘French is the language of love and stuff’: student perceptions of issues related to motivation in learning a foreign language. British Educational Research Journal 28, no. 4: 503–28.

- Zhang, X. 2020. A bibliometric analysis of second language acquisition between 1997 and 2018. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42, no. 1: 199–222.