ABSTRACT

This article presents professionals’ narratives about valuable encounters with young children in early childhood education (ECE) settings. The study aims to provide an in-depth perspective on how professionals talk about ethics in practice, and the values addressed in the narratives. Initially, professionals in Swedish ECE settings defined their understanding of a valuable encounter with a child and then used a digital app to self-register 10 such encounters during one day. After the self-registration, we interviewed the professionals and they told us about the encounters they had experienced. We identified three themes concerning who was the focus of the encounters: the professional, the child, or both reciprocally. By using a narrative approach and Nussbaum’s ethical theoretical perspective, we show how different rationales were interwoven in the stories and that situated emotions were enacted and reflected. Finally, we noticed that many valuable encounters took place in ‘in-between spaces’. They were not planned for or organised, but occurred spontaneously through professionals’ sensitive employment of an ethics in practice.

Introduction

In a time of increased demands for accountability in the welfare professions (Biesta Citation2016; Osgood Citation2010), this paper is about professionals’ definitions and narratives of ethically valuable encounters during their daily practice in Swedish early-childhood education (ECE). These relational pedagogical practices can thus be regarded as arenas where policies and values are expressed, negotiated and implemented. Different professionals’ approaches when encountering children, we argue, reflect different ways of performing professional ethics in practice. Looking at the situation from a distance, we can see that, over the last decade, Swedish ECE has been subject to many new policies, as in other countries around the world, concerning aspects such as the revision of national curricula to include more precise learning goals and increased demands for documentation and accountability (Löfgren Citation2015). Taggart (Citation2011, referring to Osgood, Citation2004) critically examines these global trends, urging us to consider the implications of these changes for early childhood professions and to pay attention to the practitioners’ own language of care. Consequently, recent research, as well as political and value-laden discussions, have focused on how the now more formal and educational side of ECE work can be combined with (Dahlberg Citation2009), or separated from (Hjalmarsson Citation2018) the deeply rooted caring aspects.

Standing as we do in the crossfire of education and/or care debates, we wanted to return to the very core of human interaction, the everyday encounters between professionals and children, and investigate how these are valued in professionals’ narratives. We address issues of how the professionals themselves stress the values linked to different rationales about teaching, learning and care when they talk about these encounters and how, in their narratives, they reflect upon their experiences.

The data are analysed from an ethically informed point of view, based on Nussbaum’s (Citation2001) theories concerning the situated emotional responses involved in professionals’ value-laden narratives. This is somewhat different from previous research describing ethical aspects of professionals’ work, which stresses the impact of values in official policies versus more personal beliefs; explicit versus implicit values (Colnerud Citation2017; Thornberg Citation2016). We argue that the narrative approach used here allows the professionals to reflect upon why a certain encounter is valuable to them.

The study aims to provide an in-depth examination of how professionals talk about ethics in practice, and the values addressed in their narratives about everyday encounters with children. Empirically, we investigate how, in their talk, professionals define and describe what they find valuable when encountering children in their educational settings. Theoretically, we discuss some of the ethical aspects of values and emotions emerging in educational practices. From an ECE practitioner’s perspective, the study has implications for how narrative reflection might shed new light on what makes an everyday situation, such as an encounter with a child, a valuable experience.

Early childhood education in Sweden

In this section, we will give a short presentation of the research focusing on the historical background and current (curriculum and policy) context of Swedish early-childhood education. Historically, ECE focused on social pedagogical issues but during the 1990 s the focus gradually shifted to a stronger interest in teaching and learning, and now these different rationales exist side by side (Lindgren and Söderlind Citation2019).

Not surprisingly, research that takes a long historical perspective stresses care as the main task for early-childhood institutions in Sweden. The need for organised childcare is described as a consequence of industrialisation, urbanisation and women’s emancipation. Furthermore, care and guiding children into adulthood were the guiding principles during the early formation of ECE, emphasising young children’s need for care (Lindgren and Söderlind Citation2019). During the 1960 s and ‘70 s, the political aspects of nurturing democratic citizens grew strong in ECE in Sweden, which also brought increased status to activities directed towards school-age children (Pihlgren Citation2017).

Descriptions of the more modern history (after 1990) of these institutions, on the other hand, stress their inclusion into the formal educational system, with the role of setting the foundations for further (cognitive) learning in schools, and the influences of new ideas concerning a more formal, predefined learning (Dahlberg Citation2009). In 1998, preschools in Sweden got their own national curriculum (National Agency of Education Citation1998), which was revised in 2011 and replaced with a new one in 2018 (National Agency of Education Citation2018). In 2016, leisure-time centres received their own chapter in the national curriculum for elementary school (National Agency of Education Citation2016).Footnote1 These reforms strengthened the emphasis on the learning goalsFootnote2 stated in the national curriculum. As a consequence, a number of curriculum and policy studies were conducted, as well as studies of didactics and subject learning during the early years. Some of these studies stress that care is constantly present in preschool activities (Riddersporre and Bruce Citation2016) and fundamental to the activities in leisure-time centres (Hjalmarsson Citation2018). In a previous study, we stressed that preschool teachers who talk about documentation refer to formulations about learning (not care) in the national curriculum in order to perform their professional identities (Löfgren Citation2015, Citation2016). Similar arguments and findings can be seen within the area of leisure-time centres, but here the emphasis is more on democracy and relational care (Hjalmarsson and Löfdahl Citation2014). Much recent research also focuses on didactic issues dealing with the teaching, learning and evaluation of different subjects (Areljung, Citation2018; Helenius Citation2018). We argue that these studies (including our own) have in common that they tend to approach the actual situation and describe activities in practice mainly as a matter of teaching, learning or caring. We also argue that there is a need to further stress issues of how values linked to different rationales are intertwined or combined in the daily work of professionals. Even though there is a qualitative difference between values linked to a more extrinsic or instrumental rationale that stresses predetermined learning goals, and values linked to a more intrinsic and emotional rationale that stresses a social pedagogical approach to care, professionals need to get these rationales to work together in their everyday encounters with children.

Value-laden aspects of early-childhood educational practice and research

Different kinds of value-laden aspects regarding the notion of care surround the ECE professions, in Sweden and elsewhere. For example, Osgood (Citation2004) described practitioners’ language of care as a counter-discourse to dominant ways of thinking about demands for quality in English preschools. In the same vein, Taggart (Citation2011) discusses caring as being linked to personal emotions and to ethical principles for professional preschool teachers.

Other value-laden aspects are actualised when the matter of how values take shape in the intersection between the public and private spheres is addressed. Ideas about what professional tasks and duties teachers in ECE are obliged to undertake could be connected both to the content and values of official policy and curricula and to more personal beliefs (Colnerud Citation2017). Thornberg (Citation2016) describes it similarly through the use of explicit values education: ‘preschools and schools’ official curricula of what and how to teach values and morals, including teachers’ explicit intentions and practices of values education’ (p. 247) and implicit values education: ‘a hidden curriculum and implicit values embedded in school and classroom practices’ (p. 247).

Finally, Emilson (Citation2007) argues that there are different educational values at stake in ECE practices; namely: care, discipline, democracy, and being individual oriented or collective oriented. These are values that could originate in either the official values or more personal ones.

The value-laden approaches (education and care) are sometimes discussed as different, competing and challenging demands. Studies have even shown that professionals might experience moral dilemmas when they find the official educational demands to be in conflict with their own personal values, even causing them to feel despair and mental stress (Santoro Citation2016). Furthermore, it has also been documented that many teachers find the emotional aspects of care the most rewarding parts of their profession (Taggart Citation2011).

Theoretical perspectives on ethics and values

In the section above, we have described some previous research on the value-laden challenges faced by professionals. Here, we present some ethical and theoretical aspects related to the issues in question. We agree with Taggart (Citation2011) that, in contemporary discourses about the purposes and tasks of ECE, it is not only policy or pedagogy that could be useful, but also ethical theory and reflections.

In the educational practices we are studying here, care ethics holds a central position, and has done so for a long time. This theory emphasises the importance of relationships, but also the specific situation and the kind of care that is given (Colnerud Citation2006; Noddings Citation2012). Noddings (Citation1984) showed that, in caring professions such as nursing and teaching, the notion of care was more important than rational rules of justice. Within the larger frame of care ethics, we are especially interested here in the fact that relations and valuable encounters do often have an emotional character, rather than merely a cognitive one. In other words, we choose to empirically observe and interpret the situated encounters identified and described by the professionals as relational in a theoretical ethical sense. Instead of general and more solid rules or principles being used as guidance in moral and ethical questions, contextual and situated aspects are considered. Afdal (Citation2014) suggests that ethical issues in educational practices should be framed as empirical ethics, with a starting point that what happens in practice constitutes what could be through reflection.

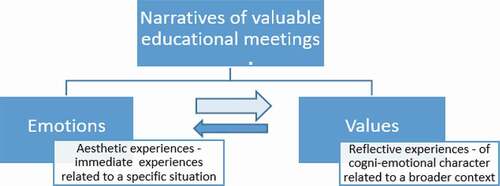

Within value-ethics, what is given value can in a broad sense be divided into that which has value in itself – intrinsic value – and that which has value because it serves another purpose – instrumental value. In this study, we focus upon professionals’ encounters with children from a value-laden ethical perspective, i.e. what kind of value is placed on the encounters between professionals and children? One philosopher who emphasises emotions as a prerequisite for values is Nussbaum. She argues that emotions are immediate and complex, but also situated and contextual, and hence rational. Furthermore, emotions are argued to be the basis for values and, through this logic, important for both ethics and morals (Nussbaum Citation2001). Similarly, Dewey (Citation1934) emphasises immediate emotional experience as an important part of human meaning-making, the aesthetic experience, something that is part of our daily lives. Through Dewey’s (Citation1916) work with experiential learning theories, we learn that experience and reflection interact along an intertwined continuum, and thus illuminate dualistic frames of mind regarding action and reflection, theory and practice. Elaborating upon and developing Dewey’s theories on learning, in a previous empirical study, Manni, Sporre, and Ottander (Citation2017) designed and used an analytical model for emotions and values as a process of experience and reflection.

The point here, in relation to this model, is that professionals’ values in educational practices might stem from spontaneous emotional experiences (the wide arrow) as well as being based on cognitive understandings of ethical guidelines, curricula, or traditional norms (the thin arrow). In other words, values could be understood and described as cogni-emotional; neither just emotional, nor only cognitive but intertwined. From this line of argument, we have developed and will use this model, and that concept, in our article.

To sum up: besides a relational ethics of care, and the emotional aspects of the same, we also pay attention to the fact that the practices of ECE are locations where different values compete, as seen in previous research. Professionals’ own values can thus be challenged by other values in the curriculum, or norms related to their profession, something that we found interesting to further investigate and highlight.

Method – research context, design and sampling

In Sweden, ECE is organised in pre-school (for children aged one to five years), pre-school class (for six-year-old children, the year before they start compulsory schooling) and leisure-time centres (for school-aged children between six and twelve years, before and after school and during holidays). Ten ECE professionals were located through our networks in teacher education and initially asked to participate via email. Seven professionals accepted the invitation, all trained teachers with more than five years’ experience of work in ECE, of whom five were working in pre-school and two in leisure-time centres. In the analysis, however, we do not compare the professionals’ statements with regard to their professional status or work setting.

Due to the initial description of the educational practices of ECE, as well as our own research interest, we chose to design our study in two steps. The choice was thus based on our understanding of the intensity of the daily ECE-practice and the time available. We then used a digital tool for the professionals’ self-registration as the first step, in combination with a more classical follow-up interview method for this qualitative study.

When the participants agreed to take part, they were instructed to download an app, free from the internet, onto their smartphones. The app we used here was Socrative.Footnote3 After they had installed it, the first question was open in nature, asking them to define: ‘What is a valuable encounter with children to you?’ Based on their own definitions, we then asked them to register on the app whenever and wherever they had a valuable encounter with a child or group of children.

Each participant made registrations over the course of one day. At the end of the day, we arranged a personal interview in which they told us in more detail about three of the encounters they had registered as valuable, and reflected upon them. The interviews lasted between 25 and 73 minutes and have similarities with stimulated recall and narrative methodology. They focus on the participants’ own stories of the encounters they had chosen. All digital answers, both open and closed, were documented in the app, while the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

We have used thematic narrative analysis (Kohler Riessman Citation2008). This means that we initially identified a number of short coherent stories consisting of a plot arc with a beginning, middle and ending (Linde Citation1993) in the transcribed interview data. The factor that these stories have in common, and the evaluative feature, is that the encounter was valuable to the professional in one way or another. During the analytical process, we alternated between the researchers, individually completing each step and then comparing each other’s results to ensure that reasonable and credible interpretations had been made. We listened to and read these stories a number of times, with a particular focus on what the professionals claimed was valuable about those particular encounters. We then grouped the stories into three themes that cover the range of stories in this set of data. This procedure assumes that telling a story is one way to reflect upon lived experiences and to perform one’s professional identity (Mishler Citation1999). In other words, the stories are understood as socially situated actions, through which the professionals make claims that the encounters they had were valuable in a professional sense. When telling their stories, they move from the immediate emotional experience to a more reflective and contextualised, rational-emotional understanding of the encounter (see ). Each theme displays its own variations, and in this article we present two stories from each theme that to some degree cover the variation within that theme. Finally, we conduct a narrow analysis of each story in order to scrutinise exactly how the claim that the specific encounter is valuable is narratively constructed. This analysis is guided by the following questions: What is valued? How is the claim valuable narratively constructed? What rationale does the claim refer to?

Figure 1. Emotions and values as part of teachers’ narratived of valuable educational meetings.

Typically, the professionals use different narrative conventions and rationales that guide us as listeners to understand the evaluative point that they want to make in the stories. For example, they use time as a narrative resource (Mishler Citation2006; Blomberg and Börjesson Citation2013), they employ another voice and quote what the children have said word for word (Bauman Citation1986), and they refer to explicit and implicit rationales about teaching, learning, and care.

Ethical considerations

Our main ethical concerns in this study dealt with how to interfere as little as possible in the daily practices we were investigating. We recognise the intensity of professionals’ work and wanted to respect them in that. Both written and oral information about the study were given before the participants voluntarily agreed to take part. All empirical data has been handled with care and confidentiality by the researchers. The participants were made anonymous, even between the two of us, since we have only used the first names or initials in the transcripts of the interviews (Vetenskapsrådet Citation2017).

Findings

First, we give an overview of how the professionals defined what a valuable encounter with a child or a group of children meant to them. Then two individual stories within each theme are presented and analysed in order to cover the variation in professionals’ narratives about ideal valuable encounters with children.

Professionals’ definitions of ideal valuable encounters – maintaining relationships

In order to gain a preliminary overview of the kind of encounters that professionals in ECE regarded as valuable, we asked them to write a short definition in the digital app. The participating professionals defined such encounters in different ways but one common characteristic of their definitions is that they stressed the importance of initiating and maintaining relationships, and that this involves emotions. Typically, several definitions described a reciprocal relationship between professional and child, others implied that the encounter had most value for the child, and finally some concrete examples of valuable encounters were given. The definitions are presented here. In the analysis, however, we do not link these definitions to the individual professionals’ stories about actual encounters with children. The definitions are regarded as an introduction to how the professionals talk about valuable encounters and, according to our understanding of empirical ethics, these statements are to be seen as reflected principles of a cogni-emotional character.

Definitions of valuable encounters based on reciprocal relationships:

We note, in line with Colnerud (Citation2006) and Noddings (Citation2012), that these definitions stress the importance of reciprocal relationships and the specific situation as central aspects when ascribing a certain value to an encounter. We conclude that the values stated here originate in both a personal and a professional point of view. This is how encounters are described in the educational literature, but also what might have been experienced in practice. In other words, we notice that these definitions are intertwined with both personal emotions and general values.

There were other definitions, however, implying that the encounter had most value for the child. These examples indicate that the professional is seen as an important actor who makes the encounter important for the child. The value then tends to be described as a gift given by the professional.

An analysis of these statements reveals the impact of professionals’ understandings of their task, and what is valued when they enter their role as a professional: being there for the child. We can also see how pre-set values within their profession affect what they themselves say is valuable.

Finally, some concrete examples of valuable encounters were given:

Typically, these concrete examples illustrate specific encounters with children in certain situations and are based on professionals’ own emotional experiences rather than what might be the expected norm. We note that some of them occur as incidents in a daily flow of activities and that the situations are described as calm or not disturbed by others. They appear to be isolated islands in an ocean of activity.

To sum up, the descriptions given by these professionals of ideal valuable encounters are based on both personal emotional experiences and ethical norms within the profession. For example, they are defined as either reciprocal between the professional and the child, or as ‘gifts’ from the professional that are implicitly or explicitly characterised as valuable for the child.

A thematic narrative analysis of professionals’ stories about valuable encounters

When analysing the interview transcripts and scanning them for stories about encounters that the professionals framed as valuable, we found three major themes, or sets of stories, concerning who was the focus of the story. In one set of stories, theme one, the professionals made themselves the protagonists in the sense that they were the ones who valued the encounter. In another set, theme two, they made a child the protagonist and the one who, according to them, valued the encounter. Finally, in theme three, there were stories stressing that the encounter was probably valued reciprocally by both the child and the professional. Relating to the theory of an ethics of care, these themes reveal aspects of the relational dimensions of how care is carried out in practice and some underlying reasons for this (cf. Noddings Citation2012). In total, we found nine coherent stories with a clear beginning, middle and ending (Linde Citation1993) in the data. These stories concern spontaneous situated examples of valuable encounters and involve cogni-emotional reflections about the recounted experiences. In the following, we provide examples of stories that illustrate the three themes.

Theme one is based on stories illustrating the narrator’s claim that the encounter was valued mainly by the professional. The first story presented here is about the feelings of joy felt by a professional at a leisure-time centre when a child took the initiative for a short and spontaneous encounter with her during the lunch break. This story is designed to inform us that the encounter is valuable because the professional felt that the child gave her attention and established a spontaneous contact with her because he wanted to share and reflect upon a certain experience.

The claim that this encounter is valuable rests on the idea that it is the boy who takes the initiative and that the encounter is spontaneous. The use of token speech (Bauman Citation1986), in which the child is quoted, reinforces the claim that the encounter is unique and genuine. The repeated use of the term ‘they’ makes the claim stronger and more general, because it indicates that the professional is used to being approached in this way. She positioned herself as someone who is to be trusted and the example stresses that she values the idea that ‘they can experience that you’re there’. In other words, she values the fact that the children see her and establish contact with her. The last phrase shows that she is the one in focus, she is the one who appreciates these encounters, not necessarily the children. This could be described as an implicit value (Thornberg Citation2016), based on the professional’s own beliefs (Colnerud Citation2017) and following an intrinsic rationale whereby the value of the encounter is based on personal emotions. The value described in this story, however, is a result of an encounter in which the professional considers herself to be a person worthy of being approached by a child in the context of a leisure-time centre, not just in any context. This frames the situated emotional receptiveness that makes the children feel welcome and invited to approach the adult as a professional virtue. In that sense, the appreciation expressed by the adult is closely related to a professional caring rational as well as a situated emotional agenda (see Taggart Citation2011).

The second set of stories illustrates the narrator’s claims that the encounter was valued mainly by the child. The first story is about a preschool boy who does some writing, perhaps for the first time in his life. This story is designed to illustrate that the professional values encounters in which a child achieves something and becomes pleased as a result of her support and encouragement.

The claim that this encounter is valuable rests on the assumption that the boy is pleased because he has learnt something and that he could see with his own eyes that he had succeeded. In this case, temporality is used as a way of emphasising the uniqueness of the encounter (cf. Blomberg and Börjesson Citation2013). The sketching of a past in which the boy was not interested in writing and ‘has barely held a pen’ is contrasted with the present state, where he is described as pleased and understanding that he ‘can achieve more than he thought’. The boy as a subject who learns is the focus; however, the professional is positioned as someone who knows how to encourage children’s learning and arranges creative and individualised learning situations. The value of this encounter could thus be linked to an instrumental rationale in which it is important to implement the national curriculum goals stating that children in preschool should practise writing skills. The value, however, is not merely linked to the actual success in learning to write, but also to the pleased feelings that are shared in an exclusive situation that occurs between the everyday group activities. This might be the most obvious example in which formalised policies and general values within the profession interrelate with the emotions involved in the actual encounter.

The next story is about a girl who was proud of herself for taking a blood test and a professional who confirmed that she was brave. The story serves as an illustration of how important the professional thinks it is for the children to know that she sees and confirms them.

In this story, the child is the protagonist and is claimed to be the one who is likely to value the encounter most. The professional’s claim that the encounter is valuable is thus based on the idea that the child values it, it is ‘very important for her […] that she saw that I saw’. This evaluative point is constructed through the use of quoting what the professional said to confirm the girl’s courage and taking another voice. The professional also dramatises the situation by positioning the girl as sensitive: ‘wounds and such are very dramatic for her’ and stating that it was ‘huge that she’d dared to take a blood test’. Thus, time becomes an important aspect in two ways. The threatening situation occurred before the girl’s arrival at preschool, in another location, but because the professional gave time for the girl to retell what had happened to her, she could frame it as a success story and feel proud and safe. The professional is thus positioned as skilled and attentive to children’s needs. In this case, there are influences from both an intrinsic, personal-emotional and an instrumental, general-normative rationale. Clearly, the professional is committed to being observant of the children’s needs; however, the importance of giving children a voice is also clearly stated in teachers’ professional ethical guidelines as well as in the national curriculum.

The third set of stories illustrates the narrator’s claims that the encounter is reciprocally valued by both the child and the professional. The first of these stories is about a professional who felt that she was invited by two children who were playing to talk about and reflect upon things for a few minutes. She explicitly describes the children as satisfied and implicitly expresses gratitude for the invitation.

The claim that this encounter is valuable is based on the fact that it is on the terms of the playing children. The professional is positioned as humble when she gently asks the children to give her access to their world. This humility is emphasised when she says she ‘got the opportunity to talk to them’ and ‘built on what they said’. In her final statement, that ‘you don’t get invited every time so you have to take the opportunity if they want to’, she expresses gratitude for being accepted as a reflective partner for a while. It is also clear that these kinds of in-between moments are exclusive privileges that sometimes add value to her professional life. All these statements build up the argument that an encounter becomes valuable if the children accept her involvement as a professional. The rationale that frames this story could be described as intrinsic and caring, built on the idea that the young children’s play is a sacred situation. The analysis of this example shows that the immediate emotional experience of just being part of children’s play makes the situational encounter mutually valuable, according to the professional.

The last story is about a professional and a boy who got to know each other better in a leisure-time centre one early morning when they were alone and found time to read a book together. The story stresses the importance of finding moments of calm in which to enjoy valuable encounters based on mutual respect, especially with children who have special needs.

The claim that this encounter was based on mutual respect is constructed in the two evaluative statements: ‘that became a good start to the day for him’ and: ‘It was a calm start for both him and for me, and I got to know him a little better’. Once again, time stands out as an important narrative resource (Mishler Citation2006). The explicit description of the early morning hours when they found time for a genuine encounter is contrasted with the implicit assumption that the rest of the ‘ordinary school day’ is somewhat chaotic from the boy’s point of view. The value in this case could be linked to an intrinsic rationale concerning the importance of protecting pupils with special needs from the sometimes-chaotic situation in classrooms. Furthermore, the value of seeing and being seen by another person is a general one. We interpret this situation as personal and emotional; it is an act of humanity, not only an act performed by a professional. This might even be a glimpse of the relational nature of being a professional, to have the sensitive notion of the needs of someone else and the desire to assist in that.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide an in-depth analysis of how professionals talk about ethics in practice, and the values they address in narratives about everyday encounters with children. We did not notice any mental or moral despair of the kind described by Santoro (Citation2016), but instead we found three qualitatively different sets of stories, or themes, in terms of who is the focus of the story, who is the person who is supposed to value the encounter. In some stories, it is the professional, in others it is a child who, according to the professional, valued the encounter, and additionally there were stories claiming that the encounter was valued by both the child and the professional. In line with other research that emphasises the situatedness of caring (Noddings Citation2012), and an empirical ethic (what happens in practice) (Afdal Citation2014), we argue that these differences should be understood as a matter of what actually happens between the professional and the child in the different situations. Acknowledging the relational aspect of teaching (Dewey Citation1916), these findings add nuances to our understanding of how the professionals not only ascribe intrinsic and extrinsic values to the encounters, but also include ideas of what the children are assumed to appreciate. For example, even though the boy who learned how to write was working with an extrinsic goal, the professional claimed that it was genuinely important for him to catch a glimpse of his own learning. Or, as in the story about the professional who was invited to join in the children’s play, the intrinsic value of humility was sanctioned by a claim that the children actually appreciated the adult’s intervention. Obviously, the introduction of new curricula and demands for documentation and accountability have influenced the conditions under which professionals work (Löfgren Citation2016).What is valued, however, is a delicate mixture of current educational norms, learning goals, personal preferences, and beliefs about what the ‘other’ (the child) thinks is valuable. Furthermore, personal standpoints and emotions, as well as more general ethical principles and codes, provide some guidelines for what professionals value, or should value, in their encounters with children (Colnerud Citation2017; Taggart Citation2011). In short, professionals are dealing with several intrinsic and extrinsic rationales about teaching, learning and care simultaneously when they work, and it is important to address the complexity of how they do this if we want to understand the values at stake in professionals’ talk about ethics in practice.

The analysis of the professionals’ stories also reveals that many of the encounters they valued took place in ‘in-between spaces’, and that these spaces are sought out and found by both the professionals and the children. Typically, these spaces appear, or are shaped, in situations where the child is moving from one location or activity to another and an encounter with a professional takes place more or less incidentally. One child is arriving from a tense meeting with medical care, another is on the way from lunch and a third happens to arrive earlier than the others at the leisure-time centre. Such spaces allow them to meet one on one in private to establish a relationship or share something meaningful. Calm and undisturbed situations appear to be fertile soil for valuable encounters. We also noticed that many encounters take place in situations where children are playing, eating or getting dressed; i.e., not during planned activities. A professional ethic of care is thus not something that one can necessarily plan, but rather something that emerges through an increased awareness of the possibilities of the ‘in-between’. By highlighting this finding, we wish to encourage professionals to stand strong in these times when activities are tending to become more regulated and planned in advance. An implication of this finding is that those responsible for planning activities in ECE should acknowledge that valuable encounters take time and demand attentiveness from the professionals, and therefore ensure that time and space for spontaneous meetings are provided.

Finally, and in line with Dewey (Citation1916, Citation1934), we argue that the findings of this study show that a few minutes of reflection on such a mundane thing as an encounter with a child in ECE allows professionals to develop their professional virtues. More specifically, we wish to focus on the role of emotions in the stories and how these emotions relate to what is considered valuable when reflecting upon them. In line with Taggart (Citation2011), we consider the emotions involved in professionals’ encounters with children to be central for the early years teaching profession, and an aspect that should not be dismissed or diminished. Following the theories of Nussbaum, emotions are rational because they are situated, and in that sense a professional’s immediate responses to a situation are professional rather than personal, as argued in previous research (Colnerud Citation2006). Based on our analysis, we further argue that there is no strict dividing line between aspects that have previously been described as either personal or professional when working as a professional in early years educational practice. Rather, several of the stories suggest that, in order to be professional, one must trust and rely upon one’s immediate (personal) emotional responses in these spontaneous situations (see ). For example, the story about the happy girl coming back from the medical examination, illustrate how the professional used her emotional sensitivity to identify a child in need of attention. The narrative approach in this study enables the professionals to reflect upon the emotions involved in their experiences of encounters with children, and allows us to describe how emotions are involved in the more reflective evaluation of their experiences of meeting children. The professionals use emotionally value-laden words like ‘appreciate’, ‘calm and nice’, ‘comforting’, ‘pleased’ and ‘satisfied’ when giving their stories an evaluative point that supports their claims that these encounters were valuable. Hence, they are moving away from the immediate and spontaneous and reflecting upon their experiences. The narrative activity thus involves a cogni-emotional reflection that serves as a way to make sense of how each encounter was valuable in relation to a broader context. This is illustrated by the two arrows in . From an ECE practitioner’s perspective, the study has implications for how narrative reflection might shed new light on what makes an everyday situation, such as an encounter with a child, into a valuable experience. Being professional, we argue, means to trust and reflect upon one’s emotions in everyday spontaneous individual encounters with children. This, we argue, increases the likelihood that encounters will become reciprocally valuable for both professionals and children. In line with Taggart (Citation2011), we think reflections upon the role of the emotions involved in professionals’ work and reconceptualisations of practice should be acknowledged as a sustainable element of professional work.

Concluding remarks

In this article, we have argued that several studies on ECE, including some of our own, have tended to address teaching, learning and caring as separate entities. Here, finally, we argue that the findings presented in this article illustrate that no particular rationale or agenda is privileged in the professionals’ talk about the situated encounters they claim to be valuable. We think this is important to remember when researchers express and address their research interests in future. Perhaps, we suggest, future research can acknowledge to a greater extent the situated and cogni-emotional character of ECE professionals’ work, and hence come closer to, and become even more relevant for, the professionals and children who actually meet in ECE contexts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating professionals in this study who shared their stories of valuable encounters in their practice with young children. Without you, this article would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. In 2018, the National Agency of Education changed the formal title ‘leisure-time centres’ in the curriculum to “School-age educare”. For this article, however, we use the term ‘leisure-time centre’. https://www.skolverket.se/andra-sprak-other-languages/english-engelska [retrieved 2020-01-17].

2. In Swedish ECE, in contrast to compulsory schooling, they do not measure learning outcomes for individual children and the national curriculum describes a holistic approach which states that “care, development and learning should be treated as a whole” (LpFö, Citation2018, 7). https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=4049 [retrieved 2020-01-17].

3. http://socrative.com [retrieved 2020-01-17].

References

- Afdal, G. 2014. “Pedagogisk hverdagsetikk.” In Empirisk etikk i pedagogiske praksiser- artikulasjon, forstyrrelse, ekspansjon, edited by G. Afdal, Å. Rothing, and E. Schjetne. 200-224. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Areljung, S. 2018. “Why Do Teachers Adopt or Resist a Pedagogical Idea for Teaching Science in Preschool?” International Journal of Early Years Education. doi:10.1080/09669760.2018.1481733.

- Bauman, R. 1986. Story, Performance and Event: Contextual Studies of Oral Stories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Biesta, G. J. J. 2016. Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy. London: Routledge.

- Blomberg, H., and M. Börjesson. 2013. “The Chronological I: The Use of Time as a Rhetorical Resource When Doing Identity in Bullying Narratives.” Narrative Inquiry 23 (2): 245–261. doi:10.1075/ni.23.2.02blo.

- Colnerud, G. 2006. “Nel Noddings och omsorgsetiken. Utbildning och demokrati.” Tidskrift för didaktik och utbildningspolitik 15 (1): 33–41.

- Colnerud, G. 2017. Läraryrkets etik och värdepedagogiska praktik. Första upplagan ed. Stockholm: Liber.

- Dahlberg, G. 2009. “Policies in Early Childhood Education and Care: Potentialities for Agency, Play and Learning.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies, edited by J. Qvortrup, W. A. Corsaro, and M. S. Honig. 228-237. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-0-230-27468-6_16.

- Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and Education, an Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. 1966 ed. New York: Free Press.

- Dewey, J. 1934. Art as Experience. New York: Penguin.

- Emilson, A. 2007. “Young Children’s Influence in Preschool.” International Journal of Early Childhood 39 (1): 11. doi:10.1007/BF03165946.

- Helenius, O. 2018. “Explicating Professional Modes of Action for Teaching Preschool Mathematics.” Research in Mathematics Education 20 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1080/14794802.2018.1473161.

- Hjalmarsson, M. 2018. “The Presence of Pedagogy and Care in Leisure-time Centres’ Local Documents: Leisure-time Teachers’ Documented Reflections.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 43 (4): 57–63. doi:10.23965/AJEC.43.4.07.

- Hjalmarsson, M., and A. Löfdahl. 2014. “Omsorg i svenska fritidshem: fritidspedagogers etiska förmåga och konsekvenser för BARN. BARN.” Forskning om barn og barndom i norden 32 (3): 91–105.

- Kohler Riessman, C. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. London: Sage.

- Linde, C. 1993. Life Stories: The Creation of Coherence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lindgren, A.-L., and I. Söderlind. 2019. Förskolans historia: Förskolepolitik, barn och barndom. Malmö: Glerup Utbildning AB.

- Löfgren, H. 2015. “Learning in Preschool: Teachers’ Talk about Their Work with Documentation in Swedish Preschools.” Journal of Early Childhood Research. doi:10.1177/1476718X15579745.

- Löfgren, H. 2016. “A Noisy Silence about Care: Swedish Preschool Teachers’ Talk about Documentation.” Early Years: An International Research Journal 36 (1): 4–16. doi:10.1080/09575146.2015.1062744.

- Manni, A., K. Sporre, and C. Ottander. 2017. “Emotions and Values: A Case Study of Meaning-making in ESE.” Environmental Education Research 23 (4): 451–464. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1175549.

- Mishler, E. G. 1999. Storylines: Craftsartists’ Narratives of Identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mishler, E. G. 2006. “Narrative and Identity: The Double Arrow of Time.” In Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics: Vol. 23. Discourse and Identity, edited by A. de Fina, D. Schiffrin, and M. Bamberg, 30–47. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- National Agency of Education (1998). Curriculum for the Preschool. (Lpfö98). Stockholm: Skolverket.

- National Agency of Education. 2016. Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Recreation Centre (LGR11) (Revised 2018). Stockholm: Skolverket.

- National Agency of Education (2018). Curriculum for the Preschool. (Lpfö18). Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Noddings, N. 1984. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Noddings, N. 2012. “The Caring Relation in Teaching.” Oxford Review of Education 38 (6): 771–781. doi:10.1080/03054985.2012.745047.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2001. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Osgood, J. 2004. “Time to Get down to Business? The Responses of Early Years Practitioners to Entrepreneurial Approaches to Professionalism.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 2 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1177/1476718X0421001.

- Osgood, J. 2010. “Reconstructing Professionalism in ECEC: The Case for the ‘Critically Reflective Emotional Professional’.” Early Years 30 (2): 119–133. doi:10.1080/09575146.2010.490905.

- Pihlgren, A. S. 2017. Fritidshemmets didaktik (Andra Upplagan. Ed.). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Riddersporre, B., and B. Bruce. 2016. Omsorg i en förskola på vetenskaplig grund. Stockholm: Natur & kultur.

- Santoro, D. 2016. “‘We’re Not Going to Do that because It’s Not Right’: Using Pedagogical Responsibility to Reframe the Doublespeak of Fidelity.” Educational Theory 66 (1–2): 263–277. doi:10.1111/edth.12167.

- Taggart, G. 2011. “Don’t We Care?: The Ethics and Emotional Labour of Early Years Professionalism.” Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development 31 (1): 85–95. doi:10.1080/09575146.2010.536948.

- Thornberg, R. 2016. “Values Education in Nordic Preschools: A Commentary.” International Journal of Early Childhood 48 (2): 241–257. doi:10.1007/s13158-016-0167-z.

- Vetenskapsrådet. 2017. God forskningssed. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrå det. VR1708 ISBN 978-91-7307-352-3.