ABSTRACT

Undertaking infant-toddler practicum during initial teacher education is critical to ensuring preservice teachers (PSTs) are well prepared for their future role as early childhood teachers. PSTs, however, can face challenges in infant-toddler practicum given the demands of this unique teaching and learning context. A knowledgeable, experienced educator as a guide is key to supporting PSTs’ learning during placement. This paper illuminates the practices of an infant-toddler educator who supported an international PST’s learning during her first nappy change on an infant-toddler practicum in an early childhood service in Australia. The paper addresses the scarce literature on PSTs’ experiences in infant-toddler settings, which can guide their relationships with colleagues. Drawing on the theory of practice architectures, we analyse a video vignette of the PST and educator during a nappy changing practice. We highlight the practices of both the educator and PST which helped the PST learn by being ‘stirred in’ to this common but unfamiliar practice for her and many other PSTs who may never have held a baby before. Implications call for cooperative and experienced educators who can support PSTs with pedagogical and practical elements of the practicum.

Introduction

Teaching infants and toddlers requires specialised knowledge and practices that reflect contemporary pedagogical understanding. Despite significant foundational learning and development occurring in the first years of life, infant-toddler pedagogy has often been considered little more than baby minding (Rockel Citation2009) by nice ladies who love children (Stonehouse Citation1989). PSTs preparing for their infant-toddler practicum may hold similar views, commenting that they do not know ‘what they would do all day’ because all babies do is ‘eat, sleep, and cry’ (Stratigos and Salamon Citation2019, 56). PSTs undertaking an infant-toddler practicum, therefore, require support to navigate the day-to-day realities of practice as they develop understandings about specialised pedagogy with very young children. Supportive hands-on practicum with infants and toddlers is crucial in preparing PSTs for their future role as early childhood education (ECE) educators.

In the infant-toddler practicum, PSTs learn and enact unique pedagogical practices alongside experienced educators who must make nuanced decisions regarding how and when to support PSTs’ learning (White et al. Citation2016). This paper examines international PST’s learning experiences during a nappy change practice on an infant-toddler practicum, highlighting the strategies and practices of an experienced educator. Supporting very young children through routines like feeding, sleeping, and toileting is a vital, intricate aspect of pedagogy that involves specific, and often complex practices (Cooper and Quiñones Citation2022), informed by philosophical foundations such as respect for the child and the importance of secure relationships. We focus on the PST’s learning about infant-toddler pedagogy through this vital but often unconsidered practice that is new and unfamiliar to the PST. Our intention is to bring visibility to the possibilities for PSTs’ learning about pedagogical complexities and nuances through everyday routines with infants and toddlers, which may seem mundane to some. The paper provides context by reviewing literature on supporting PSTs’ learning as being ‘stirred in’ to ECE practices. Next, we introduce the theory of practice architectures as an analytical framework and then discuss the methodology, including how we used the theory to help make the PST’s and educator’s practices visible through analysis of selected video data, followed by discussion of findings and conclusions.

Preservice teachers being ‘stirred in’ to ECE practice(s)

A successful practicum contributes to PSTs developing a positive self-belief in being a teacher and feeling prepared for teaching (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013). However, PSTs can face challenges given the demands of ECE as a new educational context with its own expectations, curriculum, pedagogies, rules, and regulations (Quiñones, Rivalland, and Monk Citation2019). As individual learners with unique cultural backgrounds, experiences and dispositions, PSTs often enter unfamiliar professional relationships in unfamiliar social sites with unfamiliar practice traditions. The way they navigate these landscapes and their subsequent experiences on practicum shape their becoming as practitioners of ECE practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2017).

PSTs require explicit support and opportunities to navigate and learn in such specific contexts. From a practice theory perspective, this kind of learning happens as a result of actually engaging in the practices because ‘people co-produce new practices together, as they encounter one another in action and interaction’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2017, 59). Intimate relationships and pedagogical experiences are central to daily experiences for the youngest children in educational settings (Cooper and Quiñones Citation2022; Recchia, Shin, and Snaider Citation2018). The practice of routines such as meal, sleep and nappy change times, are important moments in which social and emotional connections are fostered with infants and toddlers (Recchia, Shin, and Snaider Citation2018). PSTs require quality time, support, and knowledge to learn to engage in and co-produce these sophisticated practices with young children in caring, meaningful, and reciprocal ways. PSTs enter new ECE centres, with established routine practices, and encounter educators who help ‘stir them in’ to new practices, so they know how to go on and make sense of the unfamiliar, in-situ moments they find themselves in (Kemmis et al. Citation2017).

To best enable PSTs’ learning in infant-toddler settings, being ‘stirred in’ to practices (Kemmis et al. Citation2017, 45) happens by engaging in well planned, guided and modelled practices (Recchia, Shin, and Snaider Citation2018). Engaging in conversations about emotionally intense experiences, such as infants’ and toddlers’ crying, can enhance PSTs’ knowledge about ways to support them (Quiñones and Cooper Citation2022). Much teacher preparation focuses on the philosophical and curriculum aspects of infant pedagogy (Lee, Shin, and Recchia Citation2016) which contributes to being stirred in to specialised understandings, discourses and characteristic language of infant pedagogy. Hands-on experience is also important (Lee, Shin, and Recchia Citation2016), however, and contributes to being stirred in to specific activities and the application and extension of knowledge from teacher preparation to actual practice with infants and toddlers. The expectation that PSTs learn the nuances of routines such as nappy changing within a short time frame is a unique aspect of the infant-toddler practicum. Teacher education providers generally do not provide hands-on experience of such routine practices prior to the practicum, so for many students the placement is the first time they have engaged in such practices. In the authors’ collective experience this is not always considered by educators at the practicum site and can create tension for PSTs who do not wish to seem inexperienced.

PSTs need high-quality relationships with educators who act as mentors, are caring and supportive (Recchia and McDevitt Citation2019), and offer something more than mere supervision (Wong and Waniganayake Citation2014) to be stirred in and ‘learn how to go’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2017, 48) in ECE practice. For Ambrosetti (Citation2014), mentoring practices involve promoting reciprocal relationships with PSTs, while supervision practices involve one-way assessment of the PST’s skills and completion of tasks using institutional criteria. Being stirred in to ECE practices might be seen as bringing these practices together as PSTs learn specific skills and knowledge by completing specific tasks within the context of reciprocal professional relationships. Scholars agree that the relationship between the guiding educator and PST needs to be dynamic and reciprocal (Quiñones, Rivalland, and Monk Citation2019; Wong and Waniganayake Citation2014). Essentially then, stirring PSTs in to ECE practices includes relationships that are supportive, reciprocal, respectful, and have time to develop (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013) and which actively evaluate and promote the PST’s learning. A cooperative educator thus plays a crucial role in supporting PSTs’ professional learning through reciprocal relationships, open communication, clear instruction and guidance (Puroila, Kupila, and Pekkarinen Citation2021).

Tensions abound regarding educators’ capacity to support stirring PSTs in to ECE practices. Examples include increased responsibility and workload, not knowing how to give support, and concerns regarding assessing a PST’s practice (Ambrosetti Citation2014). Educators’ ability and willingness to give constructive feedback to PSTs, a general lack of knowledge in guiding PSTs (Quiñones, Rivalland, and Monk Citation2019), and variability in the quality of mentoring practices (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013) also come into play. Altogether, these concerns have led to calls for educators to receive professional learning and development to ensure effective guidance and support for PSTs on practicum (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013). These challenges make up the potentially constraining conditions that shape PST professional learning in ECE and reflect Kemmis et al.'s (Citation2017) assertion that coming to know ‘how to go on’ in a practice also means coming to know ‘how to go on’ in the social sites where practices occur.

Theoretical and analytical framework: the theory of practice architectures

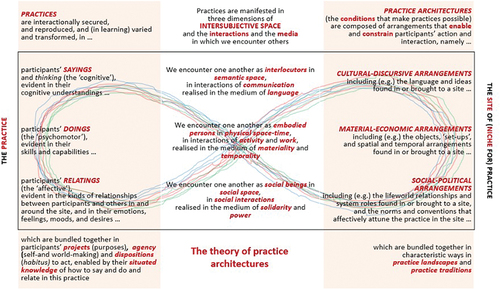

The infant-toddler practicum can be analysed through a practice theory lens whereby the actions and interactions (practices) of PSTs and guiding educators are inextricably linked within and to shared ECE sites of practice. According to the theory of practice architectures, individual practices (bundles of sayings, doings, and relatings) are enacted by individual practitioners with unique experience, understandings, and dispositions for being and learning in the world. Individual practices are inextricably linked with three types of ‘arrangements’: cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Understanding these arrangements, collectively called ‘practice architectures’ (see ), in relation to individual practitioners is critical to developing understandings about how and why particular practices occur and how they enable and constrain possibilities for learning.

Figure 1. The theory of practice architectures (Kemmis Citation2022).

The architectures of a practice site are prefigured conditions that already exist (Kemmis et al. Citation2017) and influence what practices are possible in that site. Here, we highlight some of the prefigured arrangements of Australian infant-toddler practicums at a broad level. Examining this prefigured landscape helps us to understand key conditions that are particular to infant-toddler settings, and place support and guidance as amongst the possibilities for enabling arrangements of positive PST experiences.

Cultural-discursive arrangements (a) appear in shared sites of practice through the dimension of semantic space, (b) constitute the preconditions that make shared professional language and discourses possible, and (c) enable and constrain characteristic sayings of the practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Cultural-discursive arrangements of educational practices in ECE include theories and philosophies that underpin curricula and the subsequent knowledge that is drawn on and referred to in practice as sayings, for example, a securely attached child. Cultural-discursive arrangements of infant-toddler pedagogy can, and should, include discourses of respectful and responsive interactions that recognise infants as capable citizens with rights (Salamon and Palaiologou Citation2022). Cultural-discursive arrangements of infant-toddler practicum include discourses around what it means to be a teacher, and in particular, an infant-toddler teacher. Societal notions around the value of the youngest children and those who educate and care for them may be encountered as the PST works to develop a professional identity and philosophy (Stratigos and Salamon Citation2019). Discourses of care are particularly salient in ECE and especially with infants and toddlers, which for many PSTs may be at odds with what they believe is the professional work of a teacher.

Material-economic arrangements (a) appear in shared sites of practice through the dimension of physical space and time, (b) constitute the preconditions that make shared activities possible, and (c) enable and constrain the characteristic doings of the practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Material-economic arrangements in ECE include regulations about how many children and adults can co-exist in predetermined spaces. These conditions prefigure and shape choices made at ECE sites about who is doing what and with whom, for example, how many educators are needed for staffing to maintain mandated adult-to-child ratios. More specifically, material-economic arrangements of infant-toddler pedagogy often include custom-made furniture (e.g. child stairs) to complete the unique activities associated with working with the youngest children. Material-economic arrangements of the infant-toddler practicum include the range of unfamiliar spaces and things to be negotiated that are specific to practice with infants and toddlers. For most PSTs this is their first (and only) practicum with this age group, and learning to negotiate the material dimension can be challenging. Nappy change moments are particularly helpful in highlighting this – the PST must learn to engage in new caring routines, relationships, be responsive, while navigating the change table stairs, bin, gloves, wipes, cream, nappy, and even the infant-toddler body itself which inexperienced PSTs may view as scary or fragile (Stratigos and Salamon Citation2019).

Social-political arrangements (a) appear in shared sites of practice through the medium of power and solidarity in the dimension of social space, (b) constitute the preconditions that make relationships between people and non-human objects possible, and (c) enable and constrain characteristic relatings of the practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Social-political arrangements of educational practices in ECE include the relationships and roles educators have with one another, with children, with families and with visitors in the setting, including PSTs. Social-political arrangements of practicum with infants and toddlers include requirements from the initial teacher education institution regarding the PST’s role during their practicum. These requirements are influenced by professional teaching standards which define the qualities PSTs must demonstrate, with support, to be acknowledged as a professional teacher. Power dynamics between PST and educators can also exist, especially as PSTs are often highly aware of and concerned about assessment of their practicum. The PST commences as an outsider who needs to quickly build relationships with children, families, and educators, as well as learn ‘how things are done here’.

It must be noted that cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements do not only enable and constrain corresponding sayings, doings and relatings. It is possible that, among other variations, cultural-discursive arrangements can influence doings, and material-economic arrangements can shape relatings. An Australasian study of infant-toddler practicum presents a useful example. White et al. (Citation2016) emphasised the ‘lack of explicit emphasis granted to birth-to-3 practicum in Australasia, especially for 2-year-olds’ (297). This could be related to cultural-discursive arrangements via discourses that undervalue ECE with this age group, and not only shape the subsequent sayings of infant-toddler practicum but the doings. For example, Australian early childhood initial teacher education programs are accredited by the Australian Children’s Education and Care Authority ([ACECQA] Citation2018 which mandates that early childhood PSTs undertake a minimum of 10 days of supervised practicum with children under 3 years old while requiring at least 20 or 30 days with children aged 3–5 years depending on the program being undertaken. It is unclear whether this unevenness is due to a belief that working with infants and toddlers is less complex than working with older children and therefore requires less preparation, or whether this reflects a sector in which educators with a teaching qualification are less likely to work with infants and toddlers than with older children (Stratigos and Salamon Citation2019). Here, the cultural-discursive and social-political arrangements of infant-toddler pedagogy within ECE also come into play and, in this case, shape particular doings. Regardless, it is no surprise that PSTs have expressed concerns about not feeling ready to work with infants and toddlers, including because of their limited experience with this age group (White et al. Citation2016). Altogether, as a result, Australian PSTs may experience minimal practicum with infants and toddlers. It is, thus, imperative that PSTs experience quality learning support during practicum to inform their developing pedagogical practice and identity.

This paper does not focus specifically on aspects of quality infant pedagogy that were evident either in the lead up to, or throughout the nappy change. Nor does it focus specifically on the respectful and responsive relationships between the child and educator or PST that underpin quality pedagogy more broadly. Instead, given the often-unexamined everyday practices and associated arrangements of infant-toddler practicum, this paper responds to the call to make complex infant-toddler PST learning practices in complex infant-toddler settings explicit. It does so by analysing a positive example of an international PST being stirred in to a nappy changing practice on her first infant-toddler practicum in an Australian ECE setting. Through this example, we contemplate experiences of navigating the vital relational practices between PSTs and educators acting as guides within this unique context of learning. While the literature highlights the need for PSTs to be well supported, it also highlights existing tensions and challenges for educators and PSTs. These tensions exist separate to the inherent challenges that quality infant-toddler ECE, and its complex practices, necessitate. We illuminate some of these in our analysis.

Methodology

The findings presented in this paper are part of a larger research project entitled ‘Investigating mentoring practices during infant and toddler professional experience’ (Quiñones and Cooper Citation2022). Ethical clearance was gained from the second author’s University Ethics Committee (10305) and the Department of Education and Training (2017_003461). The research aim was to better understand the pedagogical relationships between educators and international PSTs during infant-toddler practicum. International PSTs shared challenges of practicum including how to collaborate and communicate with educators in Australian ECE settings.

Participants

The larger study involved two ECE settings, four international PSTs, seven educators, and 35 infants and toddlers. The centres were selected because of their proximity to, and established partnerships with, the research university. Site 2, the focus of this paper, was a not-for-profit, multicultural community-based early childhood setting that included maternal health, ECE, playgroups, and a toy library. The educators had at least a one-year diploma qualification and at least three years’ experience. All PSTs undertook a two-year masters level early childhood teaching qualifying degree. During the three-week practicum, all PSTs were expected to undertake eight-hour days and engage in all pedagogical activities including routines, play, planning, and documenting. Ten babies aged from birth to 18 months were present in the infant room including Victor (18 months) with room leader (Peta), another educator, and PST (Ellen). All names are pseudonyms. Peta had 20 years’ experience working in ECE centres and had collaborated in a previous research project (Quiñones and Cooper Citation2022). Ellen had recently moved to Australia from China for study. For Ellen, who did not have any siblings or cousins, this was her first experience with very young children. The educator, the PST, and Victor’s parents all gave consent to participate.

Data generation

Video observations aim to document practices and participants’ relationships in practice (Fleer Citation2008). The PSTs were videoed by a research assistant for two hours during the first and final weeks of the three-week practicum, generating four hours in total for each PST. Victor was a focus child for Ellen’s practicum. Over the course of the placement she had built a relationship with him through play and engagement in routines such as mealtimes. In the third week, mindful of Ellen’s relationship with Victor, Peta suggested that Ellen have a go at changing Victor’s nappy and that this could be a good opportunity to video her developing practice with him. The subsequent 15-minute video focused on the interactions between Peta, Ellen and Victor. This video clip was selected for this paper because it was the longest of all the video data depicting a sustained interaction between mentor and PST and because it demonstrated Peta’s cooperative approach and guidance for Ellen. It also highlighted how learning about infant-toddler pedagogy can occur through supported everyday interactions with very young children and in particular the pedagogical skills involved in engaging in respectful, reciprocal, and responsive interactions during daily routines. Focusing on a nappy change episode is particularly intriguing given the potential for such caregiving moments to be devalued by PSTs prior to their practicum (Stratigos and Salamon Citation2019).

Data analysis

We (the four authors) met regularly to view, discuss, and analyse the data. First, the third author stirred the team in to using the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al. Citation2017) via a detailed presentation of the conceptual and practical underpinnings of the theory, as well as case studies exemplifying its use in infant ECE settings (Salamon Citation2017; Salamon and Harrison Citation2015; Salamon, Sumsion, and Harrison Citation2017). Next, we discussed and agreed on how to utilise the theory as an analytical frame to identify aspects of the mentor’s and PST’s practices. Our unique perspectives working with PSTs in different institutions served to enrich our understanding of the data. We then read the transcript of the video excerpt, viewed, and reviewed the video data individually and together, and used the theory to code bundles of Peta and Ellen’s sayings, doings and relatings (practices). We foreground Peta and Ellen’s practices, although we acknowledge Victor’s agency during the routine. Finally, we met again to identify elements of the practice bundles that may have enabled Ellen’s learning.

Case example

The following vignette occurs in the nappy change space in the infant (0–18 months) classroom. Three educators are in the room including an assistant, Peta, and Ellen (PST). Some children are sleeping while others are eating or playing. Ellen first approaches Victor for his nappy change.

Vignette: changing a nappy

Victor is playing when Ellen bends down to his level, sits in a low position and gently asks, ‘Are you ready to change your nappy?’ Victor continues playing. Ellen waits for Victor and looks back at Peta. Peta looks at Ellen then notices Victor continues playing. Peta walks close to Victor and points to Ellen and gently asks Victor, ‘Did you hear Ellen?’ Peta walks to the change room and Victor follows, crawling. Victor climbs Peta’s legs and stands up, both holding the door. With a positive tone, Peta says to Victor, ‘Good job walking’. Victor walks to the sink. Peta helps redirect him by saying, ‘Victor, you are going the wrong way’. Peta and Ellen together guide Victor to the change table. Peta points to the change table, while Ellen holds Victor’s hand and moves him towards the change table stairs. Peta instructs Ellen, ‘Pull the stairs from up there’. Ellen asks Peta, ‘Do you pull?’, and Peta answers, ‘Yes, I’ll show you’ and pulls the stairs from the change table. Ellen stands back to observe Peta (). Peta holds Victor’s hands and says with a cheerful tone, ‘This way Victor, stairs for you, Mr Victor, please. Ready? Let’s go up the stairs. Let’s go … one, two, three, four, five’. Victor happily climbs the stairs with Peta’s help, while Ellen observes. Without being asked, Victor lies on the change table. Peta reassures Victor, ‘Ellen is going to have a turn at changing your nappy. Peta is going to be next to you here, okay? She is going to have a turn to change your nappy’. Peta tells Ellen ‘Gloves on!’ Ellen puts on plastic gloves as Victor waits. Before they start Ellen looks concerned, and checks with Peta if it is okay for the researcher to film this intimate moment. Peta and the researcher reassure her the filming will be discrete.

Figure 2. The nappy change space (Peta holding Victor’s hands to climb the steps while Ellen observes).

Peta observes what Ellen is doing and says to Ellen, ‘Now we tear some paper towels’. Ellen shows Peta a small piece of paper towel and Peta says, ‘Yeah that much’ then provides some guidance: ‘Fold it a little bit. Place it under his bottom (Peta gently touches Victor’s leg and places the paper while lifting Victor’s legs with his involvement). Peta continues as Ellen acts on Peta’s guidance: Lift up his legs, at the same time pull his pants from underneath’. Ellen places the paper towel, then moves to the nappy and asks, ‘The paper towel goes under his…?’ Peta replies, ‘Under his bottom. It is all right; you can fix it up a bit [the paper towel]’. Then, mindful of Victor the whole time, Ellen places the paper towel under his pants. Peta helps her to lift Victor’s legs and says, ‘Under his pants … hold it up, and put it under’.

Ellen begins to take off the dirty nappy. Ellen says something and Peta responds: ‘Oh, you’ve never done that before?!’ Ellen smiles and says, ‘No’. Showing Ellen two nappy waistbands, Peta says, ‘Tumsy’s here, one on each side … Well done, both sides off … yup’. Ellen says, ‘Oh!’ and continues taking off the nappy. Peta says, ‘Open it up, open it up … right. Pop your arms… hold his legs up. [Looking at Victor] It’s okay, Victor, thank you, you’re doing a good job!’ Ellen lifts Victor’s legs and Peta moves to help her. Peta says, ‘Put it away, throw it in the bin’. Ellen: ‘Oh, there is a bin there?’ Peta nods and smiles, saying, ‘So, you want to get a wipe’. Ellen: ‘Get a wipe’. Peta: ‘Hold him up’. Ellen repeats, ‘Hold him up’. Victor is now being wiped and has no nappy. Peta guides Ellen with verbal instructions on how to clean Victor’s bottom: ‘Hang on, Victor, keep bending a little bit, darling… yup, there you go, darl… give him a wipe from the top down [gesturing with her hands]. Put it together now, grab a paper towel at the same time… put it all in the bin… peel those gloves off, peel our gloves off, straight into the bin, close. Grab the nappy, open it up, yup, more, back part’.

Ellen exclaims, ‘Aah’, as she discovers how the waistbands open. Peta points to the nappy and says, ‘Here you go – front’. Ellen says, ‘How could you tell which one is the front?’ Peta replies, ‘See this part? They will stick together in the front’. Ellen holds a nappy open. Peta says, ‘That’s the front of the nappy [points], so turn it around… take this part…’

Victor lifts his legs before Ellen places the nappy, which makes everybody smile because he shows he is attuned to what is happening. Peta says, ‘Pop his legs down a bit… bring it up through the middle… put up a bit to the top, yes, watch this… thank you, Victor. Now, tuck to one side, pull out a bit – not too big’. Ellen asks, ‘Did I do it very tight?’ Peta replies, ‘Not too tight – just right. Can you hold that side? Hold it down, tuck it [the nappy] under [Victor’s legs]’. Ellen: ‘Like this?’ Peta smiles and nods her head: ‘Here you go!’ Ellen finishes placing the nappy before asking, ‘And… what is next?’ Peta replies. ‘Pull the pants up’. Peta further guides her with ‘I’ll show you a little trick’ to help get his pants on. When done, Ellen looks happy and exclaims: ‘Oh… there you go, Victor, it’s your nappy changed. Thank you for your cooperation. So excited… new experience everyday [smiles]’. Peta: ‘We’ll do it again! Thank you, Victor, you [are] finished, darling. Can you pop down the stairs?’ She turns to Ellen with more guiding words: ‘Follow his lead’. Ellen and Peta then help Victor descend the stairs, and he washes his hands with Ellen’s support while Peta stands back and observes. When Victor is finished, he returns to the playroom. Then Ellen shows Peta how to wipe down the change table with a paper towel and sanitising spray.

Discussion

Respectful sayings and direct instruction

Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) describe how cultural-discursive arrangements constitute a shared professional language that shapes the expected sayings of a practice. In the nappy change vignette, there are essentially two cooperative practices that are co-occurring – Peta guiding Ellen, and Ellen learning by following instructions to change Victor’s nappy. As such, Peta appears to engage in two types of sayings - firstly those that are characterised by respectful language towards infant Victor and which are modelled for Ellen to support the development of her pedagogy in relation to very young children, and secondly those that constitute direct instruction for Ellen to explicate the practical ‘how’ of changing a nappy. All these sayings are part of Peta’s practice and supportive of Ellen’s learning to be an infant-toddler educator.

Consistent with respect as a quality of an effective pedagogical relationship (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013), respectful language towards Victor is modelled for Ellen throughout the vignette. For example, Peta reassures Victor at the start of the nappy change that although Ellen will be changing his nappy, she will be close by. Peta acknowledges and encourages Victor with sayings such as ‘Good job walking’ as she guides him to the nappy change table. Peta continues to model respectful acknowledgement of Victor throughout the nappy change using language, for example expressing ‘thank you Victor’ in response to him helping them to navigate the nappy change together. Peta’s respectful language is also extended to Ellen as Peta guides her practice with many gentle and good-humoured encouragements such as smiles, nods of the head, ‘yes’, and ‘well done’. At the end of the nappy change as Ellen seems to relax a little, she demonstrates the success of Peta’s modelling of respectful language when she gives a joyful acknowledgement of both Victor and her success – ‘There you go, Victor, it’s your nappy changed’ before thanking Victor for his cooperation. Both Peta’s and Ellen’s sayings demonstrate a strong acknowledgement of Victor and respectful exchange of ideas with him and between each other, likely informed by discourses of a competent image of the child evident in Peta’s saying of ‘Follow his lead’.

Peta’s direct instructional sayings to Ellen about how to ‘do’ a nappy change forms a significant component of the dialogue. Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) explain that the sayings of practice reflect a shared professional language and discourse. There are different ways to change a nappy, so Peta’s instructional and professional language represents the cultural-discursive arrangements found in this site, reflective of expectations regarding ‘how things are done here’ and what Peta knows is an effective nappy change practice with an infant. The importance of these instructional sayings becomes evident early in the vignette when Peta expresses surprise after realising Ellen has never changed a nappy before. Thus, Peta provides guidance about how to manage the relational aspects and also instructions on the physical dimensions of paper towels, nappy, and Victor’s body – all aspects of hands-on experience with an infant (Recchia, Seung Yeon Lee, and Shin Citation2015 that appear unfamiliar to Ellen. At times Peta’s verbal instructions take the form of physical demonstration, for example when she shows Ellen ‘a little trick’ to secure Victor’s pants. The effectiveness and holistic nature (Ambrosetti Citation2014) of Peta’s support of Ellen’s developing pedagogy and confidence as a PST is confirmed at the end of the vignette when Ellen celebrates her achievement saying, ‘so excited … new experience everyday’.

Modelling and allowing time for doing

Modelling is a common teaching strategy, used widely in ECE and can be seen as among the material-economic arrangements that shape what early childhood educators do with both children and colleagues. Collegial role modelling in mentoring relationships, for example, often takes the form of a guided process aimed at enhancing professional knowledge and skill development (Wong and Waniganayake Citation2014). The modelling in the vignette involves Peta’s actions as a collegial role model who demonstrates aspects of an effective nappy change for Ellen’s benefit. This modelling occurs in the context of their relationship, which informs the shaping of Ellen’s professional identity regarding ‘how to be’, ‘how to understand’ and ‘how to act’ as an educator (Wong and Waniganayake Citation2014, 174). The modelling also shapes the nappy change practice, which requires specific technical skills developed through the course of the interaction. In acknowledging the dynamic relationship between learning and practice, Peta’s modelling enables Ellen to be stirred in to the intimate practice of a nappy change, through their shared actions and interactions. As Ellen intently observes Peta’s doings, she is being oriented to the ways she herself will come to ‘know’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2017) about nappy change practices as one important aspect of infant-toddler pedagogy in a supportive context (Recchia, Seung Yeon Lee, and Shin Citation2015).

Importantly, beyond Peta’s instructional and supportive sayings and modelling, Peta affords time for Ellen to learn through doing the nappy change for herself. Time and schedules are key elements of infant-toddler pedagogy given the many daily routines very young children participate in and which afford rich opportunities for fostering social and emotional connections (Recchia, Shin, and Snaider Citation2018). These routine times necessitate and shape the doings of infant-toddler pedagogy, acting as material-economic arrangements that are made up of influences from the child, the families and the centre. A potential outcome of there being many things to do at many times of the day is a sense of rushing through practices, which seems at odds with the need to slow down to enable both child and PST learning. While Peta does model, at no point does she take over the nappy change to hurry things along – indeed the whole episode lasts for 15 minutes. Instead, she continues to acknowledge and reassure Victor while giving direct instruction and feedback to Ellen on pedagogical and practical next steps. Peta’s doings during the nappy practice thus involves allowing Ellen time and space to ‘do’ the nappy change herself while highlighting effective practices (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013). Importantly, Ellen’s doings seem to be enabled by knowing Peta was there to guide her learning by answering questions, giving feedback and instructions, and acknowledging her achievements. At the end of the vignette, Peta tells Ellen ‘We’ll do it again!’, indicating her understanding of the importance of offering more time via multiple opportunities for Ellen to continue practising and consolidating her practical skills as part of her developing pedagogy. Furthermore, the one-on-one interaction between them was enabled by the other educators looking after the rest of the children playing and sleeping, which ascribed value to this learning situation and time for the support of the PST’s learning.

Affective, reciprocal relatings

Victor is key to many of Peta and Ellen’s relatings which emerge from the social-political arrangements of the site via a philosophy of respect for children’s agency. They are also reflected in Peta’s thoughtful and respectful consideration of Victor’s agency in participating in his own nappy change. Agency is a particular discourse that shapes relationships in ECE and is present in early years curricula and codes of ethics (DEEWR Citation2009; DET Citation2016). Infant agency is particularly challenging given the inherent power imbalances between the youngest children and adults. The subsequent relationships that develop are among the social-political arrangements of infant-toddler pedagogy. By respectfully yet firmly modelling how to create space for Victor to act in agentic ways, Peta seems to be doing the same for Ellen.

At first, Ellen bends down to Victor deferring the power to him and then seeking help from Peta. Then, Peta seems to reclaim the power by directing Victor’s attention to Ellen’s invitation and guiding him to the nappy change space. In doing so she demonstrates support for Ellen in her role as PST while respectfully acknowledging Victor’s agency. Effective and affective relatings between Peta and Ellen that balance the power in a cooperative and collaborative relationship based on reciprocity (Ambrosetti Citation2014; Quiñones, Rivalland, and Monk Citation2019; Wong and Waniganayake Citation2014) are thus demonstrated. Although each party plays unique roles in the episode – Peta is the knowledgeable, experienced cooperative educator and Ellen is the relatively inexperienced PST – there is a sense that they are working through the practice together. Ellen is learning, therefore, by being stirred in to the particular actions and interactions of this new experience (Kemmis et al. Citation2017) within the contingent relationship they co-create. Ellen is open to the experience and patiently receives Peta’s modelling, guiding instructions and support. Although Peta gives direct instruction at times, they are offered in caring ways, resulting in a reciprocity in the sayings, doings, and relatings between Peta and Ellen throughout. Ellen seems to feel well-supported and confident to ask clarifying questions. This situation contrasts with those that involve educators who are unable or unwilling to provide feedback (Quiñones, Rivalland, and Monk Citation2019). The dispositions of individual practitioners shape their individual practices, and in this example, Peta is willing to support Ellen towards success. Peta’s affective relating involves a patient manner by providing the time and space for Ellen to undertake this practice. Victor’s part is also acknowledged when he lifts his legs to help Ellen place the new nappy. Ellen experiences success and is encouraged by Peta to do it again, fostering her self-belief in being an educator (Murphy and Butcher Citation2013).

Conclusion and implications

Our analysis illuminates the practices of a knowledgeable, experienced, and supportive educator and an international PST learning to navigate a nappy change together, and the conditions that enabled and constrained the PST’s learning about becoming an infant-toddler teacher. Key practices to support PST learning identified include respect, allowing time, taking on multiple roles, reciprocity and moving in and out of instructional supervision as needed. Many of these were highlighted in the vignette of Peta, Ellen and Victor. The practice of modelling was at the heart of ‘practising together’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2017, 47) – how to say, how to do, and how to relate - as they were happening in a respectful and supportive context. Peta was orienting Ellen to pedagogical strategies expected of educators and PSTs learning to practice with infants and toddlers. In this way, Ellen was supported during her practicum to come to know how to go on in the sayings, doings, and relatings which constitute some of the sophistications and complexities of infant-toddler pedagogy.

Their interaction was an example of the importance of slowing down to support PSTs’ learning about the physical and pedagogical nuances of routines with infants and toddlers. It also illuminates how a PST might be stirred in to a new practice by being immersed in the ‘vortex of an activity that already has some shape’ and is held in place by particular arrangements (Kemmis et al. Citation2017, 48). These arrangements enabled the educator time to support the PST, to draw on her knowledge and experience of effective and affective infant-toddler pedagogy, to approach the practicum as a relational learning experience, and to do so within an already existing space and established routine for nappy changes.

Overall, our focus on practice allowed us to understand how a PST’s knowledge, language, and skill development were enabled by particular cooperative practices. It also illuminated what happens when a PST is stirred in to the practice of an infant’s nappy change by learning the sayings, doings, and relatings of a specialised practice, as well as the enablers and constraints of these interactions. We conclude with a call for further research to examine the multi-layered, sedimented conditions and arrangements in place for infant-toddler practicum and how they might enable and constrain how both new and established educators navigate shared experiences within them.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the director, educators, PSTs, and infants and toddlers who participated in this study. We pay tribute to Peta who left us in January 2023. We remember her warmth, smile, and knowledge, and acknowledge her valued contribution to the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- ACECQA (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority). 2018. Guide to the National Quality Framework. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/media/23811.

- Ambrosetti, A. 2014. “Are You Ready to Be a Mentor? Preparing Teachers for Mentoring Pre-Service Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39 (6): 30–42. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.2.

- Cooper, M., and G. Quiñones. 2022. “Toddlers as the One-Caring: Co-Authoring Play Narratives and Identities of Care.” Early Child Development and Care 192 (6): 964–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1826465.

- DEEWR [Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations]. 2009. Belonging, Being & Becoming the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Barwon, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

- DET [Department of Education and Training]. 2016. Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework: For All Children from Birth to Eight Years. Melbourne: DET.

- Fleer, M. 2008. “Using Digital Video Observations and Computer Technologies in a Cultural – Historical Approach.” In Studying Children. A Cultural – Historical Approach, edited by M. Hedegaard and M. Fleer, 104–117. New York: Open University Press.

- Kemmis, S. 2022. Pedagogy, Education, and Praxis. https://stephenkemmis.com/pedagogy-education-and-praxis/.

- Kemmis, S., C. Edwards-Groves, A. Lloyd, P. Grootenboer, I. Hardy, and J. Wilkinson. 2017. “Learning as Being ‘Stirred in’ to Practices.” In Practice Theory Perspectives on Pedagogy and Education: Praxis, Diversity and Contestation, edited by P. Grootenboer, C. Edwards-Groves, and S. Choy, 45–65. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3130-4_3.

- Kemmis, S., J. Wilkinson, C. Edwards-Groves, I. Hardy, P. Grootenboer, and L. Bristol. 2014. Changing Practices, Changing Education, 25–41. Gateway East, Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-47-4_2.

- Lee, S. Y., M. Shin, and S. L. Recchia. 2016. “Primary Caregiving as a Framework for Preparing Early Childhood Preservice Students to Understand and Work with Infants.” Early Education and Development 27 (3): 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.1076675.

- Murphy, C., and J. Butcher. 2013. “‘They Took an Interest’: Student Teachers’ Perceptions of Mentoring Relationships in Field Based Early Childhood Teacher Education.” New Zealand Research in Early Childhood Education Journal 16:45–62.

- Puroila, A.-M., P. Kupila, and A. Pekkarinen. 2021. “Multiple Facets of Supervision: Cooperative Teachers’ Views of Supervision in Early Childhood Teacher Education Practicums.” Teaching and Teacher Education 105:103413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103413.

- Quiñones, G., and M. Cooper. 2022. “Infant–Toddler teachers’ Compassionate Pedagogies for Emotionally Intense Experiences.” Early Years 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2021.2008324.

- Quiñones, G., C. Rivalland, and H. Monk. 2019. “Mentoring Positioning: Perspectives of Early Childhood Mentor Teachers.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 48 (4): 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2019.1644610.

- Recchia, S. L., and S. E. McDevitt. 2019. Relationship-Based Infant Care as a Framework for Authentic Practice: How Eun Mi Rediscovered Her Teaching Soul. Occasional Paper Series 42. https://doi.org/10.58295/2375-3668.1301.

- Recchia, S., L. Seung Yeon Lee, and M. Shin. 2015. “Preparing Early Childhood Professionals for Relationship-Based Work with Infants.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 36 (2): 100–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2015.1030523.

- Recchia, S. L., M. Shin, and C. Snaider. 2018. “Where is the Love? Developing Loving Relationships as an Essential Component of Professional Infant Care.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (2): 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1461614.

- Rockel, J. 2009. “A Pedagogy of Care: Moving Beyond the Margins of Managing Work and Minding Babies.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 34 (3): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693910903400302.

- Salamon, A. 2017. “Infants’ Practices: Shaping (And Shaped By) the Arrangements of Early Childhood Education”. In Exploring Education and Professional Practice, In edited by K. Mahon, S. Francisco, and S. Kemmis, 83–99.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2219-7_5.

- Salamon, A., and L. Harrison. 2015. “Early Childhood Educators’ Conceptions of Infants’ Capabilities: The Nexus Between Beliefs and Practice.” Early Years 35 (3): 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1042961.

- Salamon, A., and I. Palaiologou. 2022. “Infants’ and Toddlers’ Rights in Early Childhood Settings.” In (Re)conceptualising Children’s Rights in Infant-Toddler Care and Education: Transnational Conversations, edited by F. Press and S. Cheeseman, 45–58. Gateway East, Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05218-7_5.

- Salamon, A., J. Sumsion, and L. Harrison. 2017. “Infants Draw on ‘Emotional Capital’ in Early Childhood Education Contexts: A New Paradigm.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 18 (4): 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949117742771.

- Stonehouse, A. 1989. “Nice Ladies Who Love Children: The Status of the Early Childhood Professional in Society.” Early Child Development and Care 52 (1–4): 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443890520105.

- Stratigos, T., and A. Salamon. 2019. “Interwoven Identities in Infant and Toddler Education and Care: ‘What Do You Think Babies Will Do with Clay? Make Pots?!” In Multiple Early Childhood Identities, edited by A. Salamon and A. Chng, 51–64. Oxon, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429444357-5.

- White, E. J., M. Peter, M. Sims, J. Rockel, and M. Kumeroa. 2016. “First-Year Practicum Experiences for Preservice Early Childhood Education Teachers Working with Birth-To-3-Year-Olds: An Australasian Experience.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 37 (4): 282–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2016.1245221.

- Wong, D., and M. Waniganayake. 2014. “Mentoring as a Leadership Development Strategy in Early Childhood Education.” In Researching Leadership in Early Childhood Education, edited by E. Hujala, M. Waniganayake, and J. Rodd, 163–180. Tampere: Tampere University Press.